Abstract

Background

Penehyclidine hydrochloride is a novel drug for acute respiratory distress syndrome. The aim of the study was to reveal the impact of smoking on the efficacy of the drug in rats with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Material/Methods

A 132 Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this study; 72 rats were used in the smoking models. Penehyclidine hydrochloride (3 mg/kg) was injected to induce acute respiratory distress syndrome. Rats were divided into the smoking group and the non-smoking group; these 2 groups were subdivided according to different treatments. The arterial blood gas analysis (PaO2/FiO2) and extent of pneumonedema (wet-to-dry weight ratio) was analyzed to evaluate disease severity. Expressions of mitogen-activated protein kinases (p-p38MAPK, p38MAPK, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, and JNK) in lung tissue were measured using western blot assay.

Results

Penehyclidine hydrochloride improved the pneumonedema (wet-to-dry weight ratio) and hyoxemia (PaO2/FiO2) of the disease in non-smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001 respectively), but not in smoking group (P=0.244, P=0.424 respectively). The drug inhibited the expressions of phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK in non-smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001 respectively), but not in smoking group (P=0.350, P=0.507 respectively). In the smoking group, blocking the phospho-p38MAPK or phospho-ERK signal pathway by their inhibitors showed a better therapeutic effect on the pneumonedema and hyoxemia compared with the use of penehyclidine hydrochloride (phospho-p38MAPK: P=0.004, P=0.010 respectively; phospho-ERK: P=0.022, P=0.004 respectively).

Conclusions

The study confirmed the protective effect of penehyclidine hydrochloride in acute respiratory distress syndrome, mainly in the non-smoking group, which might be explained by the fact that phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK signal pathways were difficult to inhibit by the drug in the smoking group.

MeSH Keywords: Lipopolysaccharides; Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult; Smoking

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a clinical condition occurring in severe illness or trauma patients. According to the “Berlin definition” in 2012, ARDS is characterized by an apparent lung injury in 1 week, continuous progression of respiratory symptoms, bilateral infiltration on lung imaging (consistent with edema) not explained by other lung diseases, respiratory failure not caused by cardiovascular factors, and decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratio [1,2]. Severity of the disease is classified as mild (PaO2/FiO2: 201 to 300 mmHg), moderate (PaO2/FiO2: 101 to 200 mmHg) and severe (PaO2/FiO2: ≤100 mmHg) [1,2]. ARDS is usually triggered by sepsis, mechanical ventilation, pneumonia, drowning, circulatory shock, aspiration, or trauma [3]. Alveolar epithelial cell injuries, capillary endothelial cell injuries, and diffuse interstitial and alveolar edemas are the main pathologic changes in ARDS [4].

ARDS is a very critical syndrome with a death rate varying from 25% to 50% in different centers globally [5,6]. An increasing number of studies have revealed that widespread inflammation and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine imbalance are responsible for the development and progression of the disease [7–9]. Therefore, anti-inflammatory drugs might be helpful to improve the prognosis of ARDS patients.

Penehyclidine hydrochloride (PHC) is one kind of selective anti-cholinergic drug, and exerts not only anti-nicotinic and anti-muscarinic effects, but also significant anti-inflammatory effect [10,11]. Previous in vivo studies demonstrated the protective action of PHC against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [12], cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury [13], and acute kidney injury [14]. An increasing number of studies also revealed that PHC pre-conditioning as well as post-conditioning improved pulmonary gas exchange, histological injury, and wet-to-dry weight (W/D) ratio in rat models of ARDS [15–17].

Many early studies have demonstrated the important role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the development of ARDS. Chen et al. suggested that p38MAPK activation was one important aspect of the signaling event that mediated the release of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1β and contributed to burn-induced ARDS [18]. Nash et al. reported that oral administration of an agent inhibitory for p38MAPK offered a protective effect in the lungs from both neutrophil influx and protein leak associated with ARDS [19]. Schuh et al. revealed that ERK signaling cascade was involved in the inflammatory response of ARDS, and pharmacologic inhibition of this signaling pathway provided a promising new therapeutic strategy for lung inflammatory diseases [20]. Further studies focusing on PHC reported that the protective effect of the drug against ARDS was implemented partly by inhibiting the activation of p38MAPK and ERK [15,16].

Previous studies have reported the association of p38MAPK and ERK with cigarette smoking in several inflammatory lung diseases. Kuo et al. suggested that smoking caused the activation of p38MAPK, ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), which led to Jun or p53 phosphorylation and FasL induction links Fas phosphorylation and triggered cellular apoptosis [21]. Li et al. reported that smoking induced chronic inflammation and upregulated the phosphorylated-ERK and Nrf2 expression, which regulated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [22]. Volpi et al,. revealed that α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and possibly reactive oxygen species contained in cigarette smoke stimulated the vascular endothelial growth factor expression and released from pulmonary cells through p38MAPK signaling in COPD [23]. So, cigarette smoking might activate the expressions of p38MAPK and ERK and affect the protective effect of PHC on ARDS.

Therefore, we conducted an in vivo study to validate the protective effect of PHC against ARDS, to confirm the relationship between cigarette smoking and the activations of MAPKs, and to further explore the potential effect of cigarette smoking on efficacy of PHC in ARDS rats.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University. All procedures were conducted according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in 2011.

Animals

A total of 132 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 220 to 290 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Company. These rats were kept in a relatively stable environment with a constant temperature and an artificial 12-hour light-dark cycle. Before the study, they were fed a standard diet for a week.

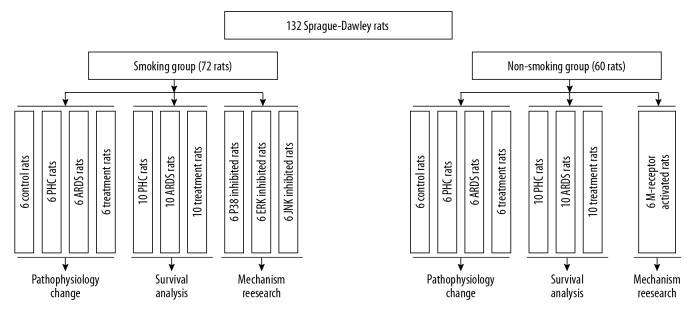

As shown in Figure 1, the rats were divided into a smoking group (n=72) and a non-smoking group (n=60). In order to establish a rat model of smoking, the rats in the smoking group were exposed to cigarette smoke 60 minutes each time, 2 times a day, 6 days per week for 24 weeks [24]. After smoking exposure, rats were treated with different schedules. In the smoking group, there were 7 subgroups. (1) IN the control subgroup (n=6), normal saline (0.9%) was administered intravenously. (2) In the PHC subgroup (n=16), only PHC (3 mg/kg) was administered intravenously. Among these 16 rats, 10 rats were only included in survival analysis. (3) In the ARDS subgroup (n=16), only penehyclidine hydrochloride (LPS) (3 mg/kg) was injected into the trachea to induce ARDS. The ARDS model was constructed as described in Lang et al. [25] and Wei et al. [26]. Briefly, rats were anesthetized by 2% pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) through intraperitoneal injection. Then they were instilled with a saline dissolved 5 mg/kg LPS (from Escherichia coli O111: B4; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) into the trachea. Of the 16 ARDS rats, 10 rats were included in survival analysis. (4) In the treatment subgroup (n=16): 3 mg/kg PHC was injected intravenously into the ARDS models. Similarly, 10 treatment rats were included in survival analysis. In order to explore the role of MAPKs in the relationship between smoking and the efficacy of PHC, another 3 subgroups were also set up. (5) In the p38 inhibited subgroup (n=6), both PHC (3 mg/kg) and SB203580 (10 mg/kg) were injected into the ARDS models. SB203580 was a pyridinyl imidazole inhibitor widely used to elucidate the roles of p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase [27]. (6) IN the ERK inhibited subgroup (n=6), both PHC (3 mg/kg) and PD98059 (0.3 mg/kg) were injected into the ARDS models. PD98059 was a selective, cell permeable inhibitor of the MEK/ERK pathway that acted by preventing the activation of MEK1 and MEK2 by upstream kinases [28]. (7) IN the JNK inhibited subgroup (n = 6), both PHC (3 mg/kg) and SP600125 (15 mg/kg) were administered intravenously into the ARDS models. SP600125 was a potent, cell-permeable, selective and reversible inhibitor of JNK [29].

Figure 1.

Flow chart in the study. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome.

In the non-smoking group, there were 5 subgroups: control subgroup (n=6), PHC subgroup (n=16), ARDS subgroup (n=16), and treatment subgroup (n=16). These 4 subgroups received the same research protocol as the corresponding subgroups in the smoking group. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (M-receptor) was involved in the activations of MAPKs [30,31]. In order to reveal the potential role of M-receptor in the association of smoking with the efficacy of PHC, the fifth subgroup in the non-smoking group was set up. It was M-receptor activated subgroup (n=6), and LPS (5 mg/kg), PHC (3 mg/kg) and pilocarpine (0.2 mg/kg) were administered in this subgroup. Pilocarpine was a muscarinic agonist that activated the activity of M-receptor [32].

The safety and efficacy of all the research drugs had been validated in the preliminary experiment. LPS-induced rat model simulated one kind of ARDS caused by Gram negative bacilli infection or septic shock. Because endotoxin was the most important risk factor for ARDS, this LPS-induced model had great practical significance [3]. The intravenous injection of LPS (5 mg/kg) had been widely used to induce ARDS in rats in several studies [33–35]. So, the conventional dose (5 mg/kg) of LPS had also been adopted in this study. In the previous studies, the rats were injected with PHC from low dose (0.3 mg/kg) to high dose (3 mg/kg), and the protective effect of the drug against ARDS had always be demonstrated [15–17]. Because the purpose of the study was to explore the dilution effect of smoking on the drug, we adopted a high dose (3 mg/kg) of PHC in this study.

Survival analysis

As mentioned, there were 60 smoking or non-smoking rats identified for survival analysis separately from 2 PHC subgroups, 2 ARDS subgroups and 2 treatment subgroups. These rats were observed for 96 hours. Poor outcome was defined as death due to any cause.

Specimen collection

All the rats were included in the following experiment except the 60 rats for the survival analysis.

Six hours after injection, arterial blood specimens were collected from carotid arteries under anesthesia. Then, the rats were sacrificed to dissect the lung tissue specimens. The tissue specimens from the left lung were lavaged for 5 times with 5 mL ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). More than 90% of these bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALFs) were recovered successfully. Then, BALFs were centrifuged and isolated to obtain their supernatants. The tissue and BALFs specimens were stored at −70°C for the following analysis.

Lung injury assessment

The left cranial lobes were processed routinely and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. A light microscope (100× magnification) was adopted for observing the histopathological changes in these specimens.

Arterial blood gas analysis was conducted at room temperature immediately after being sacrificed using a blood gas analyzer (ABL 520 Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Respiratory index (PaO2/FiO2) was reported.

BALF levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and albumin (ALB) were determined using several commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Pulmonary edema in the right cranial lobes was evaluated using W/D ratio. The specimens were excised, rinsed in PBS, blotted and weighed to determine the “wet” weight. Then, these lung lobes were dried at 80°C for 72 hours and weighed to determine the “dry” weight. W/D ratio was calculated using a following formula: W/D ratio=wet weight/dry weight×100%.

Neutrophil infiltration in the right caudal lobes was detected by myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity [31]. The specimens were homogenized with 0.5% hexadecyl-trimethylammonium bromide (HETAB) solution. The resulting homogenates were centrifuged and adopted for detection of MPO activities using a commercial MPO activity assay kit (Fluorometric). The procedures were conducted according to the instructions. The absorbance was measured at 460 nm using a spectrometer.

Expression of MAPKs

Expression levels of phospho-p38MAPK, phospho-ERK, and phospho-JNK in the left caudal lobes were measured using several commercial western blot kits (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The specimens were homogenated, and the resulting supernatants were used for the following detection. Equal amounts of protein (50 ug) were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were transferred to nylon membranes, which were blocked by 5% skimmed milk with Tris-buffered saline. Primary antibodies were adopted for probing the proteins overnight. The primary antibodies were listed as follows: mouse monoclonal anti-p38MAPK (1: 1000 dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-p38MAPK (1: 1000 dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-ERK1/2 (1 μg/mL dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (1 μg/mL dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-JNK (1 μg/mL dilution), mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-JNK (1: 2000 dilution) and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1: 5000 dilution). The membranes were incubated in goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G for 2 hours (0.1 μg/mL dilution). All the antibodies were purchased from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence kits (Amersham Life Science, Buckinghamshire, UK). TotalLab v2.01 software was used to quantify the intensities of the bands, and the relative intensity of each protein was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variable was showed as mean ± standard deviation. Difference of these variables among more than 2 groups was determined by one-way variance analysis (ANOVA) with Duncan’s post-hoc test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate the difference of the survival rates between the different subgroups. If P value <0.05, the difference was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis in the study was performed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

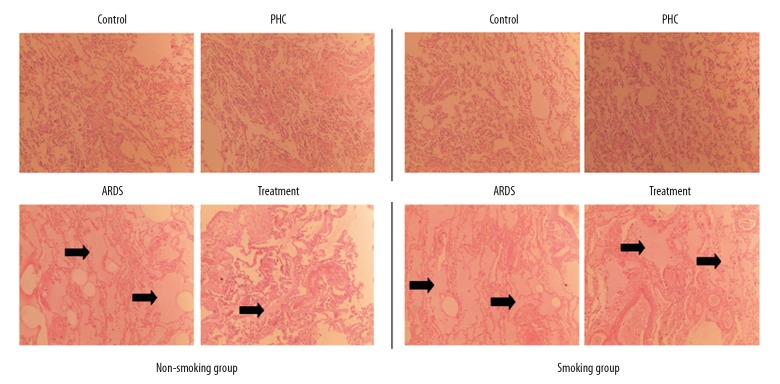

To assess the degree of lung injury, we observed that the pathological changes in lung tissues. As a result, there was significant difference of the pathological characteristics between the control group and the ARDS group. Lung tissues obtained from the control group showed normal without any sign of interstitial edema or inflammatory cells. However, lung tissues in the ARDS group showed interstitial inflammation, atelectasis, and edema (Figure 2). From the cellular morphology, we concluded that the ARDS model was successfully constructed.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the lung tissue specimens stained by hematoxylin-eosin in the rats (original magnification 100×). Pulmonary edema is indicated by the arrowheads. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Compared with the control rats, the PHC rats showed no pathological change in the smoking group as well as the non-smoking group, but the ARDS rats showed more significant pulmonary edema both in the smoking group and the non-smoking group. PHC in the treatment rats improved this pathological change in the non-smoking group, but not in the smoking group.

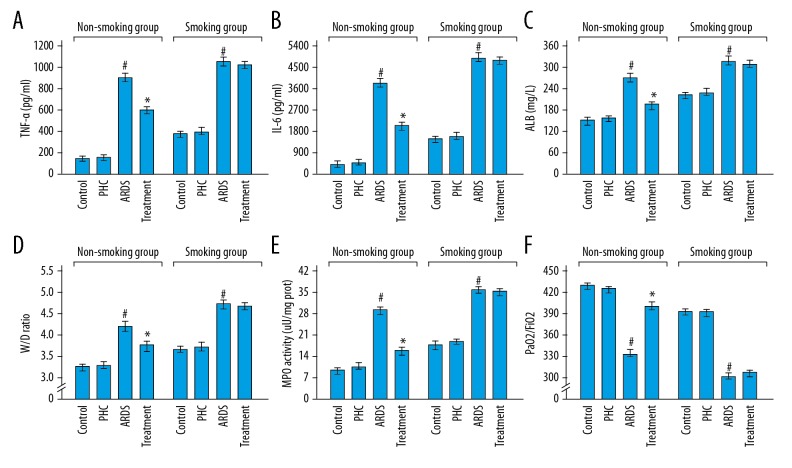

Figure 3A–3C show that there was no significant change in the BALF levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and ALB between the control rats and the PHC rats both in the smoking group (P=0.835, P=0.605, and P=0.361 respectively) and the non-smoking group (P=0.924, P=0.591, and P=0.274 respectively). The elevated levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and ALB in BALFs were found in the ARDS rats compared with the PHC rats in the smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively) as well as the non-smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively). More importantly, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and ALB in BALFs dropped in the treatment rats compared with the ARDS rats in the non-smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively), but not in the smoking group (P=0.529, P=0.363, and P=0.594 respectively).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the pathological and physiological indicators in the arterial blood and lung tissue specimens. (A–C) BALF levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and ALB between the control rats and the PHC rats both in the smoking group and the non-smoking group. (D, E) The W/D ratios and MPO activities of control rats, PHC rats, and ARDS rats in the smoking group and the non-smoking group. (F) The PaO2/FiO2 ratios of control rats, PHC rats, and ARDS rats in the smoking group and the non-smoking group. The detailed results were shown in Table 1. # Compared with the PHC rats, P<0.05; * compared with the ARDS rats, P<0.05. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6 – interleukin-6; ALB – albumin; W/D – wet-to-dry weight; MPO – myeloperoxidase.

Figure 3D–3E shows the W/D ratios and MPO activities were similar for the control rats compared with the PHC rats both in the smoking group (P=0.751 and P=0.602 respectively) and the non-smoking group (P=0.403 and P=0.574 respectively). Compared with the PHC rats, the W/D ratios and MPO activities of the ARDS rats significantly increased both in the smoking group (P<0.001 and P<0.001 respectively) and the non-smoking group (P<0.001 and P<0.001 respectively). In the non-smoking group, the W/D ratios and MPO activities dropped in the treatment rats compared with the ARDS rats (P<0.001 and P<0.001 respectively). But, in the smoking group, the W/D ratios and MPO activities were equivalent between the ARDS rats and the treatment rats (P=0.244 and P=0.572 respectively).

Figure 3F shows that the PaO2/FiO2 ratios were equivalent between the control rats and the PHC rats in the smoking group (P=0.533) as well as the non-smoking group (P=0.166). Compared with the control rats, the ARDS rats showed the decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratios both in the smoking group (P<0.001) and the non-smoking group (P<0.001). In the non-smoking group, the treatment rats showed the increased PaO2/FiO2 ratios compared with the ARDS rats (P<0.001). However, in the smoking group, the treatment rats had the similar PaO2/FiO2 ratios compared with the ARDS rats (P=0.424). The detailed results of Figure 3 were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the pathological and physiological indicators in the arterial blood and lung tissue specimens.

| Group | Control | PHC | ARDS | Treatment | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs. PHC | PHC vs. ARDS | ARDS vs. treatment | |||||

| Non-smoking group | |||||||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 180.3±9.4 | 180.8±8.2 | 912.2±71.0 | 619.2±26.2 | 0.924 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 453.3±30.8 | 465.2±42.2 | 3883.3±147.2 | 2050.0±118.3 | 0.591 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ALB (mg/L) | 161.3±7.8 | 168.0±11.8 | 276.0±10.3 | 208.8±4.3 | 0.274 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| W/D ratio | 3.3±0.1 | 3.4±0.1 | 4.3±0.2 | 3.8±0.1 | 0.403 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MPO activity (μU/mg prot) | 9.7±2.8 | 10.2±2.2 | 30.3±2.8 | 17.5±2.0 | 0.574 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PaO2/FioO2 | 435.2±10.0 | 427.5±7.6 | 331.7±14.7 | 400.8±14.3 | 0.166 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Smoking group | |||||||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 408.3 | 410.2 | 1048.3±37.5 | 1035.5±30.2 | 0.835 | <0.001 | 0.529 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 1553.3±100.3 | 1583.3±94.2 | 4752.5±104.2 | 4705.0±73.4 | 0.605 | <0.001 | 0.363 |

| ALB (mg/L) | 216.3±5.3 | 220.3±8.8 | 328.5±12.1 | 324.2±15.0 | 0.361 | <0.001 | 0.594 |

n=6 in each group. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome; TNF-α – tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6 – interleukin-6; ALB – albumin; W/D – wet-to-dry weight; MPO – myeloperoxidase.

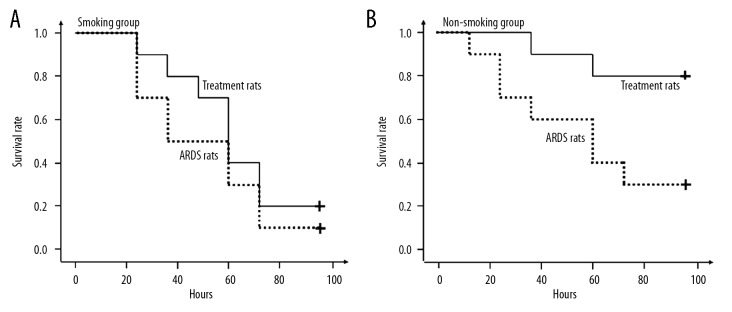

In the 96-hour period, none of the rats died in the PHC subgroups. So, only the rats in the ARDS subgroups and the treatment subgroups were included in the survival analysis. Figure 4A shows that the survival rate was equivalent between the treatment rats and the ARDS rats in the smoking group (P=0.383). Figure 4B shows that the treatment rats showed significantly higher survival rate compared with the ARDS rats in the non-smoking group (P=0.024).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses in the rats. (A) The survival rate was equivalent between the treatment rats and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) rats in the smoking group (P=0.383). (B) The treatment rats showed significantly higher survival rate compared with the ARDS rats in the non-smoking group (P=0.024).

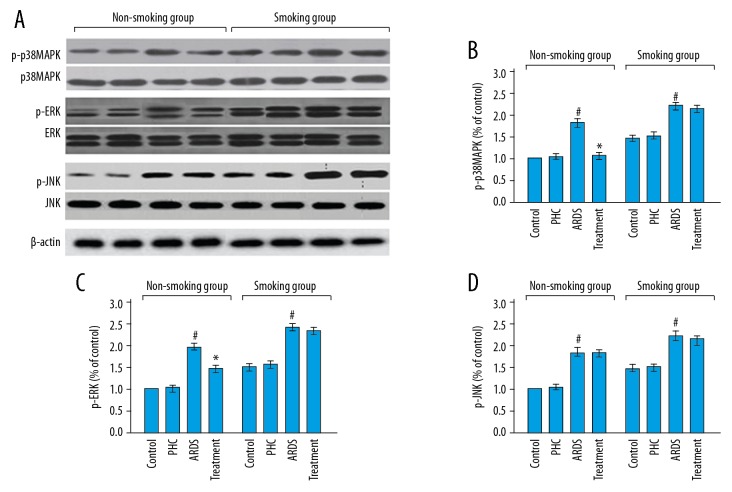

Figure 5 shows that there was no change in the expression levels of the phospho-p38MAPK, phospho-ERK, and phospho-JNK proteins between the control rats and the PHC rats both in the smoking group (P=0.932, P=0.648, and P=0.700 respectively) and the non-smoking group (P=0.082, P=0.145, and P=0.341 respectively). The expressions of these 3 proteins in the ARDS rats were significantly increased compared with the control rats in the non-smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively) as well as the smoking group (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively). In the non-smoking group, the expressions of the phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK proteins (P<0.001 and P<0.001 respectively), but not phospho-JNK protein (P=0.581), were remarkably lower in the treatment rats than in the ARDS rats. In the smoking group, there was no significant change in the expressions of phospho-p38MAPK, phospho-ERK, and phospho-JNK proteins between the ARDS rats and the treatment rats (P=0.350, P=0.507, and P=0.679 respectively). The detailed results of Figure 5 were shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

(A–D) Expression levels of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the lung tissue specimens. # Compared with the control rats, P<0.05; * compared with the ARDS rats, P<0.05. The detailed results were shown in Table 2. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Table 2.

Expression levels of mitogen-activated protein kinases in lung tissue specimens.

| Group | Control | PHC | ARDS | Treatment | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control vs. PHC | PHC vs. ARDS | ARDS vs. treatment | |||||

| Non-smoking group | |||||||

| p-p38MAPK | 1 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.8±0.1 | 1.2±0.1 | 0.082 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| p-ERK | 1 | 1.0±0.1 | 2.0±0.1 | 1.5±0.1 | 0.145 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| p-JNK | 1 | 1.0±0.1 | 1.8±0.1 | 1.8±0.1 | 0.341 | <0.001 | 0.581 |

| Smoking group | |||||||

| p-p38MAPK | 1.5±0.1 | 1.5±0.1 | 2.3±0.1 | 2.2±0.1 | 0.932 | <0.001 | 0.35 |

| p-ERK | 1.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 | 2.6±0.1 | 2.6±0.1 | 0.648 | <0.001 | 0.507 |

| p-JNK | 1.6±0.1 | 1.6±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.3±0.1 | 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.679 |

n=6 in each group. PHC – penehyclidine hydrochloride; ARDS – acute respiratory distress syndrome.

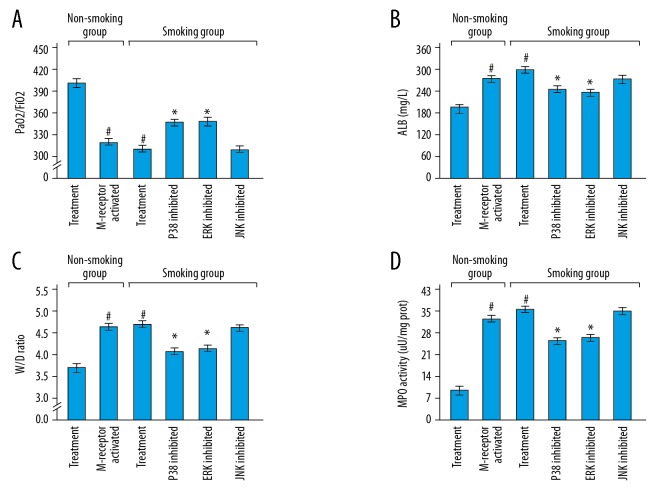

Figure 6 shows that compared with the treatment rats in the non-smoking group, the M-receptor activated rats in the non-smoking group and the treatment rats in the smoking group showed the decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratios and increased levels of ALB, W/D ratios and MPO activities (M-receptor activated rats in the non-smoking group: P<0.001, P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively; treatment rats in the smoking group: P<0.001, P<0.001, P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively). Compared with the treatment rats in the smoking group, the p38 inhibited rats and the ERK inhibited rats in the smoking group showed the increased PaO2/FiO2 ratios and decreased levels of ALB, W/D ratios, and MPO activities (p38 inhibited rats: P=0.010, P<0.001, P=0.004, and P<0.001 respectively; ERK inhibited rats: P=0.004, P<0.001, P=0.022, and P<0.001 respectively). However, there was no significant difference in the levels of PaO2/FiO2 ratios, ALB, W/D ratios, and MPO activities between the treatment rats in the smoking group and the JNK inhibited rats in the smoking group (P=0.808, P=0.923, P=0.373, and P=0.533 respectively). The detailed results of Figure 6 were shown in Table 3.

Figure 6.

(A–D) Potential roles of M-receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathways in the rats. ALB – albumin; W/D – wet-to-dry weight; MPO – myeloperoxidase. # Compared with the treatment rats in the non-smoking group, P<0.05; * compared with the treatment rats in the smoking group, P<0.05. The detailed results were shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Potential roles of M-receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathways in the rats.

| PaO2/FiO2 | ALB (mg/L) | W/D ratio | MPO activity (μU/mg prot) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment rats in non-smoking group | 400.8±14.3 | 208.8±4.3 | 3.8±0.1 | 17.5±2.0 |

| M-receptor inhibited rats in non-smoking group | 325.8±13.6 | 280.7±15.1 | 4.5±0.1 | 33.2±2.5 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatment rats in non-smoking group | 400.8±14.3 | 208.8±4.3 | 3.8±0.1 | 17.5±2.0 |

| Treatment rats in smoking group | 317.7±10.6 | 324.2±15.0 | 4.6±0.3 | 36.1±2.4 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treatment rats in smoking group | 317.7±10.6 | 324.2±15.0 | 4.6±0.3 | 36.1±2.4 |

| P38 inhibited rats in smoking group | 347.8±20.5 | 250.8±14.4 | 4.0±0.3 | 26.4±2.6 |

| P value | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Treatment rats in smoking group | 317.7±10.6 | 324.2±15.0 | 4.6±0.3 | 36.1±2.4 |

| ERK inhibited rats in smoking group | 350.0±17.9 | 247.2±12.9 | 4.1±0.3 | 27.7±2.8 |

| P value | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.022 | <0.001 |

| Treatment rats in smoking group | 317.7±10.6 | 324.2±15.0 | 4.6±0.3 | 36.1±2.4 |

| JNK inhibited rats in smoking group | 319.1±9.5 | 326.0±12.6 | 4.5±0.2 | 35.2±2.8 |

| P value | 0.808 | 0.923 | 0.373 | 0.533 |

ALB – albumin; W/D – wet-to-dry weight; MPO – myeloperoxidase.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first published article focusing on the effect of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of PHC in ARDS rats. Based on the results of the study, we discovered that the ARDS rats which were induced by LPS showed a series of pathophysiological changes, such as respiratory acidosis, hypoxemia, pulmonary edema, neutrophil infiltration and cytokine releasing. The ARDS rats which had a history of smoking showed more severe conditions compared with the ARDS rats without a history of smoking. We also found that PHC treatment might be able to improve these abnormalities, which was consistent with several previous studies [15–17]. However, the protective effect of PHC against ARDS exerted mainly in the non-smoking rats. In the ARDS rats with a history of smoking, such protective effect of the drug disappeared.

Previous studies suggested that the development of ARDS was associated with the activation of p38MAPK and ERK signal pathways, and the protective effect of PHC was implemented partly by inhibiting these signal pathways [15,16]. In this study, there were some more findings. First, the expressions of phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK proteins were significantly elevated in the ARDS rats, especially in the ARDS rats with a history of smoking. Second, PHC treatment improved the conditions of ARDS in the rats in the non-smoking group, but not in the smoking group. Third, PHC treatment reduced the expressions of these 2 proteins in the non-smoking group, but not in the smoking group. Fourth, in the smoking group, blocking the phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK signal pathways also improved the conditions of ARDS. Taken together, PHC exerted its efficacy against ARDS following by the inhibition of the phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK signal pathways only in the non-smoking group. In the rats in the smoking group, these 2 signal pathways were difficult to be inhibited by the drug. The inhibitors of these signal pathways were able to simulate the efficacy of the drug in the rats in the smoking group. Therefore, cigarette smoking might attenuate the protective efficacy of PHC against ARDS partly by activating the p38MAPK and ERK signal pathways.

G protein coupled pathway was a classical signal pathway in human cells. M-receptors received external signals, transmitted these signals into the cells through the G protein coupled pathway and regulated several kinds of physiological activities including the activation of MAPKs [30,31]. The study found that the activation of M-receptors partly offset the efficacy of PHC, indicating that M-receptors were involved in the protective effect of PHC on ARDS. PHC, a selective anti-cholinergic drug, might exert its inhibitory effect on p38MAPK and ERK signal pathways through the downregulation of M receptor and G protein signaling pathway. Furthermore, cigarette smoking was able to reverse the expression of G protein and upregulate G protein signaling pathway [32,33]. This could partly explain the disappearance of PHC efficacy in the rats in the smoking group.

In addition, this study found that LPS caused more severe hypoxia, pulmonary edema, and inflammation in the rats in the smoking group than in the non-smoking group. More severe conditions led to worse efficacy of the drug. This might be another explanation for the reverse effect of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of PHC.

It is well known that cigarette smoking is still very common in the world. The results from this study indicate that a patient who smoked in the recent past before the development of ARDS not only might show a more serious condition, but also might have an increased risk of PHC resistance. Considering that many studies have been exploring the therapeutic effect of PHC on ARDS, our findings might limit the possible clinical application of the drug in the future.

This was a preliminary study without a firm conclusion, and more solid evidence is required to validate the effect of smoking on the efficacy of PHC. First, possible dose-effect relationship between cigarette smoking and the efficacy of PHC should be explored. The interval from stopping smoking to the development of ARDS might be an important marker for the efficacy of PHC, and should be fully studied. Second, except for M receptor – G protein – MAPKs signaling pathway, there should be other molecular mechanisms involved in the effect of smoking on PHC, which need to be discussed in more detail in the future. In addition, there were some methodological limitations in the study. The size of the sample was small, and only 6 rats in each subgroup were included in the pathophysiological and mechanism experiments. Grouping was not fully based on the principle of randomization. So, our results should be validated by more well-designed studies at the molecular level in the future.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the study confirmed the protective effect of PHC on ARDS mainly in rats in the non-smoking group, which might be explained by the fact that phospho-p38MAPK and phospho-ERK signal pathways were difficult to inhibit by PHC in rats in the smoking group. Considering that the inhibitors of these 2 signal pathways were able to simulate the efficacy of the drug in rats in the smoking group, we speculated that cigarette smoking activated the p38MAPK and ERK signal pathways, offset the effect of PHC on these 2 signal pathways and attenuated the efficacy of PHC on LPS-induced ARDS rats.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: An expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1573–82. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan E, Brodie D, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: Aadvances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018;319:698–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aeffner F, Bolon B, Davis IC. Mouse models of acute respiratory distress syndrome: A review of analytical approaches, pathologic features, and common measurements. Toxicol Pathol. 2015;43:1074–92. doi: 10.1177/0192623315598399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raymondos K, Dirks T, Quintel M, et al. Outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in university and non-university hospitals in Germany. Crit Care. 2017;21:122. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1687-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neto AS, Barbas CSV, Simonis FD, et al. Epidemiological characteristics, practice of ventilation, and clinical outcome in patients at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units from 16 countries (PRoVENT): An international, multicentre, prospective study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:882–93. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu MW, Su MX, Wang YH, et al. Effect of melilotus extract on lung injury by upregulating the expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in septic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu J, Wang Y, Zhang J, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of oxysophoridine on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:2672–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang YY, Qiu XG, Ren HL. Inhibition of acute lung injury by rubriflordilactone in LPS-induced rat model through suppression of inflammatory factor expression. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:15954–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han XY, Liu H, Liu CH, et al. Synthesis of the optical isomers of a new anticholinergic drug, penehyclidine hydrochloride (8018) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:1979–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao HT, Liao Z, Tong RS. Penehyclidine hydrochloride: A potential drug for treating COPD by attenuating Toll-like receptors. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:317–22. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S36555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin D, Ma J, Xue Y, Wang Z. Penehyclidine hydrochloride preconditioning provides cardioprotection in a rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shu Y, Yang Y, Zhang P. Neuroprotective effects of penehyclidine hydrochloride against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Brain Res Bull. 2016;121:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao HJ, Yu DM, Zhang TZ, et al. Protective effect of penehyclidine hydrochloride on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury in rat. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:9334–42. doi: 10.4238/2015.August.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen W, Gan J, Xu S, et al. Penehyclidine hydrochloride attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury involvement of NF-kappaB pathway. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhan J, Liu Y, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of penehyclidine hydrochloride on expressions of MAPK in mice with CLP-induced acute lung injury. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:1909–14. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu GM, Mou M, Mo LQ, et al. Penehyclidine hydrochloride postconditioning on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibition of inflammatory factors in a rodent model. J Surg Res. 2015;195:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen XL, Xia ZF, Ben DF, et al. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in lung injury after burn trauma. Shock. 2003;19:475–79. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055242.25446.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nash SP, Heuertz RM. Blockade of p38 map kinase inhibits complement-induced acute lung injury in a murine model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:1870–80. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuh K, Pahl A. Inhibition of the MAP kinase ERK protects from lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1827–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo WH, Chen JH, Lin HH, et al. Induction of apoptosis in the lung tissue from rats exposed to cigarette smoke involves p38/JNK MAPK pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;155:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Yan Y, Shi Q, et al. Recuperating lung decoction attenuates inflammation and oxidation in cigarette smoke-induced COPD in rats via activation of ERK and Nrf2 pathways. Cell Biochem Funct. 2017;35:278–86. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpi G, Facchinetti F, Moretto N, et al. Cigarette smoke and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes elicit VEGF release through the p38 MAPK pathway in human airway smooth muscle cells and lung fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:649–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Wang J, Cao J, et al. Immunoregulation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on the chronic cigarette smoking-induced lung inflammation in rats. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/932923. 932923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang S, Li L, Wang X, et al. CXCL10/IP-10 neutralization can ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome in rats. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei Y, Wang Y. Celastrol attenuates impairments associated with lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in rats. J Immunotoxicol. 2017;14(1):228–34. doi: 10.1080/1547691X.2017.1394933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, et al. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–33. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, et al. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13681–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caulfield MP, Birdsall NJ. International union of pharmacology. XVII. Classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:279–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthiesen S, Bahulayan A, Holz O, Racké K. MAPK pathway mediates muscarinic receptor-induced human lung fibroblast proliferation. Life Sci. 2007;80:2259–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor SE, al-Hashimi I. Pilocarpine, an old drug; A new formulation. Tex Dent J. 1996;113:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullane KM, Kraemer R, Smith B. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;14:157–67. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan ES, Qiu W, Baccarelli A, et al. Cigarette smoking behaviors and time since quitting are associated with differential DNA methylation across the human genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3073–82. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kõks G, Uudelepp ML, Limbach M, et al. Smoking-induced expression of the GPR15 gene indicates its potential role in chronic inflammatory pathologies. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2898–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]