Abstract

Objective 1) To assess the feasibility of research methods to test a self-management intervention aimed at preventing acute to chronic pain transition in patients with major lower extremity trauma (iPACT-E-Trauma) and 2) to evaluate its potential effects at three and six months postinjury.

Design A pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) with two parallel groups.

Setting A supraregional level 1 trauma center.

Methods Fifty-six adult patients were randomized. Participants received the intervention or an educational pamphlet. Several parameters were evaluated to determine the feasibility of the research methods. The potential efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma was evaluated with measures of pain intensity and pain interference with activities.

Results More than 80% of eligible patients agreed to participate, and an attrition rate of ≤18% was found. Less than 40% of screened patients were eligible, and obtaining baseline data took 48 hours postadmission on average. Mean scores of mild pain intensity and pain interference with daily activities (<4/10) on average were obtained in both groups at three and six months postinjury. Between 20% and 30% of participants reported moderate to high mean scores (≥4/10) on these outcomes at the two follow-up time measures. The experimental group perceived greater considerable improvement in pain (60% in the experimental group vs 46% in the control group) at three months postinjury. Low mean scores of pain catastrophizing (Pain Catastrophizing Scale score < 30) and anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores ≤ 10) were obtained through the end of the study.

Conclusions Some challenges that need to be addressed in a future RCT include the small proportion of screened patients who were eligible and the selection of appropriate tools to measure the development of chronic pain. Studies will need to be conducted with patients presenting more serious injuries and psychological vulnerability or using a stepped screening approach.

Keywords: Acute Pain, Chronic Pain, Wound and Injuries, Lower Extremity, Self-Care, Health Promotion, Internet, Feasibility Studies, Pilot Projects

Introduction

Lower extremity trauma (ET) is one of the most painful types of injury [1,2]. An important proportion of patients who have suffered major lower ET (i.e., patients requiring hospitalization for surgical and multidisciplinary team acute care management) [3] develop chronic pain [4–7] with substantial participation restriction in self-care, work, and social activities for six months or more [5–13]. Some preventive interventions have been shown to decrease the likelihood of transitioning from acute to chronic pain [14–23]. These interventions target risk factors (e.g., high-intensity acute pain, pain catastrophizing, pain-related fear) and protective factors (e.g., pain self-efficacy) for chronic pain [2,5,8,24–30] by incorporating educational and cognitive-behavioral strategies [31,32] that ultimately promote self-management [33,34]. Hence, patient skills and confidence in managing symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes, and psychosocial consequences are enhanced [35]. However, most studies on preventive interventions for chronic pain have been conducted in the back pain population, and although patients with a major lower ET are known to be at high risk of chronic pain, no effective intervention has yet been proposed for them.

Therefore, a self-management intervention aimed at preventing acute to chronic pain transition and tailored to patients with major lower extremity trauma (iPACT-E-Trauma) was developed [36,37]. A hybrid web-based and in-person mode of delivery was selected, per recommendations from clinicians and patients during the iPACT-E-Trauma development phase [37] and evidence on the positive effects of web-based intervention in the context of pain and behavior changes [38–40]. A pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) was then conducted to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the iPACT-E-Trauma intervention and to test the research methods [36]. The study was deemed necessary to confirm the applicability of the intervention content and to gather evidence on the feasibility of the study parameters in a population in which interventions aimed at preventing chronic pain have not yet been studied [36]. The feasibility and acceptability assessments of the intervention [41] showed that it was possible to deliver most of the intervention content (71% to 100%). Moreover, ≥80% of participants attended intervention sessions, and <20% did not apply most of the self-management behaviors relevant to their condition. In addition, participants rated iPACT-E-Trauma key features as very acceptable. The present paper outlines findings on the feasibility of the research methods (i.e., the extent to which the research steps and activities can be carried out as planned and well-received by patients) [42] and the potential efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma to prevent the transition from acute to chronic pain after major lower ET at three and six months postinjury. These steps provided important information on the modifications that need to be made to research methods parameters in provision of a full-scale RCT to test the efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma.

Methods

Objectives

The objectives of this study were twofold: 1) to assess the feasibility of the research methods associated with the testing of iPACT-E-Trauma and 2) to evaluate its potential effects at three and six months postinjury. Pain intensity and pain interference with activities of daily living were the primary outcomes of the potential effects of the intervention. Secondary outcomes included protective factors for chronic pain (i.e., pain self-efficacy, pain acceptance) and risk factors for chronic pain (i.e., pain catastrophizing, pain-related fear, anxiety and depression symptoms), as well as health care service utilization and return to work at three and six months postinjury.

Design

This pilot experimental study used an RCT design with two parallel groups (i.e., experimental and control), based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement on pilot and feasibility trials (Supplementary Data) [43]. The study was registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Registry (ISRCTN: 91987302), and the research protocol was published [36].

Setting

This pilot RCT was conducted at a level 1 supraregional academic trauma center in Montreal, Canada. Patients in the experimental group received the first three iPACT-E-Trauma sessions during hospitalization, and sessions 4–7 were delivered after hospital discharge in a rehabilitation center, at home, or during surgical follow-up appointments at the outpatient orthopedic clinic. Patients in the control group received an educational pamphlet during their hospitalization in the trauma center. Research Ethics Board (REB) approvals (Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal project No. 2017–1333; McGill University project No. A02-M15–16B) were granted for this study.

Sample Characteristics

Eligible patients met the following inclusion criteria: 1) aged 18 years or older; 2) able to read and speak French; 3) had a major lower ET; and 4) were at risk of developing chronic pain, that is, reported moderate (4 to 6/10 on a numerical rating scale [NRS]) to severe (7 to 10/10 on an NRS) pain intensity [44] upon movement [45] 24 hours postinjury. Patients were excluded if they had 1) spinal cord injury; 2) other trauma associated with high-intensity pain (e.g., more than two fractured ribs [46], surgical abdominal trauma [47]); 3) principal site of pain was not lower ET; 4) amputation; 5) cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia, severe psychiatric disorder, Glasgow Coma Scale score <13/15 [48], administration of sedative agents, mechanical ventilation); and 6) more than seven days of hospitalization before being eligible to participate in the study.

Intervention

Control Group

Participants randomized to the control group received the standard pain management treatment, consisting of analgesic administration by nurses (i.e., opioids and co-analgesia such as acetaminophen and pregabalin), physiotherapy sessions, and an educational pamphlet. The pamphlet was introduced by an expert trauma nurse more than 24 hours after but within seven days of postadmission. The expert trauma nurse visited participants the day after delivery of the educational pamphlet to answer their questions.

Experimental Group

Participants in the experimental group received the iPACT-E-Trauma intervention [36,37] as well as the standard pain management treatment. The iPACT-E-Trauma components were 1) education on the biopsychosocial dimensions of pain and the prevention/regulation of maladaptive thoughts; emotions, and behaviors; 2) optimal use of pharmacological strategies for acute pain management; 3) optimal use of nonpharmacological strategies; 4) adoption of health promotion strategies; and 5) return to pre-injury activities. It included seven sessions (five regular and two boosters), each ranging from 15 to 30 minutes, and was provided by an expert trauma nurse with a Master’s degree. The intervention sessions were given over a period of three months and were initiated within seven days postinjury. Sessions 1 and 2 were scheduled within the first week postinjury, sessions 3 to 5 were offered on a weekly basis thereafter, and booster sessions 6 and 7 were given at six and 12 weeks postinjury. A hybrid delivery mode was selected, combining web-based learning modules (i.e., Traitement et Assistance Virtuelle Infirmière et Enseignement [TAVIE] platform–Soulage TAVIE Post-Trauma; English Translation: “Treatment Virtual Nurse Assistance and Teaching”) [49,50] and in-person contact with an expert trauma nurse. The first three sessions were web-based, and the last four sessions were delivered in person or by phone, at the rehabilitation center, at the outpatient orthopedic clinic, at home, or at the hospital in case of a lengthy hospital stay.

Variables and Measurement Tools

A Research Methods Feasibility Form [42,51] was used to assess 1) adequacy of sampling pool and recruitment time; 2) ease with which participants were screened; 3) feasibility of applying randomization procedures as planned; 4) attrition rate in experimental and control groups; and 5) ease of data collection procedures. Furthermore, as described in the published protocol [36], we used validated questionnaires in French to measure outcome variables. Primary outcomes (pain intensity and interference) were measured with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) [52–54]. Pain intensity upon movement on average in the last seven days and mean score of pain interference with daily activities during the same period served as primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes were measured with the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) [55,56], the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire–Eight items (CPAQ-8) (W. Scot et al., unpublished data) [57], the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [58,59], the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) [60,61], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [62–64]. Parameters of the research methods and outcome variables were measured at different time points (Table 1): at T0 (baseline) as well as T7 (end of intervention to three months postinjury), and T8 (six months postinjury). Moreover, data on the feasibility of the research methods were collected after the delivery of each intervention session (T1 to T7). The outcome questionnaires at T7 and T8 could be completed in hard copy and sent by mail or filled out electronically through secure online software, according to participant preference.

Table 1.

Schedule of enrollment and assessment

| Study Time Points | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment |

Allocation |

Postallocation* |

Closeout |

|||||||

| Participants Timeline | -t1 | 0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | t6 | t7 | t8 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | ||||

| ≥ 24 h to 7 d Postadmission | 3 mo Postinjury | 6 mo Postinjury | ||||||||

| Enrollment | ||||||||||

| Eligibility screen/informed consent | √ | |||||||||

| Allocation of participants | √ | |||||||||

| Assessments | ||||||||||

| Sociodemographic questionnaire | √ | |||||||||

| 1. Primary objectives | ||||||||||

| 1.1. Research methods feasibility | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| 1.2. Potential effects on primary outcomes (BPI questionnaire) | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| 2. Secondary objectives | ||||||||||

| Potential effects on secondary outcomes (PSEQ, CPAQ-8, PCS, TSK, HADS, PGIC questionnaires, Medical Attention Seeking and Professional Services Utilization Form, Return to Work Questionnaire) | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Complementary variables | ||||||||||

| Health status (SF-12v2) | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Injuries and treatments (injury profile form) | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Analgesics consumption (analgesics consumption form) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Neuropathic pain (DN4 questionnaire) | √ | |||||||||

| PTDS (PCL-5 questionnaire) | √ | √ | ||||||||

BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; CPAQ-8 = Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire–eight items; DN4 = Douleur Neuropathique 4; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PCL-5 = Post-Traumatic Syndrome Disorder Checklist–Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5; PGIC = Patient Global Impression of Change; PSEQ = Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire; PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; SF-12v2 = Short-Form–12 items, version 2; TSK = Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia.

*S1 to S7: Intervention sessions 1 to 7.

Complementary measures, including types of injury, severity of injury (i.e., Injury Severity Score [ISS] [65] and Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] [66] score), treatments received (i.e., Medical Attention Seeking and Professional Services Utilization Logbook), Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC; i.e., improvement in pain, functioning, quality of life and global condition) [67,68], general health status (Short-Form 12 items, version 2 [SF-12v2]) [69,70], analgesic consumption, neuropathic pain component (Douleur Neuropathique 4 [DN4]) [71], and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)] [72,73], were also evaluated to facilitate data interpretation. The PCL-5 was translated into French using a forward–backward method of translation but was not validated in this language at the time we initiated the study. High reliability scores for the 20 items of the PCL-5 (Cronbach alpha ≥ 0.95) were obtained in this study.

Sample Size

Sample size was determined using the 80% one-sided confidence interval of estimated main trial effect size, as recommended for pilot studies [74]. However, there was not enough information available on effect size for chronic pain prevention studies at the time of study design. Hence, the effect size documented in chronic pain trials (SMD = 0.25–0.35) [75,76] for pain intensity and pain interference with daily activities (primary outcomes) was used to calculate sample size and was estimated at 23 participants per group. Considering a 20% potential attrition rate [51], a total of 56 participants were recruited and randomized into each group (experimental and control). This sample size was considered sufficient to document feasibility.

Allocation

Randomization

The randomization sequence was generated by a coordinating center, ensuring that researchers were blinded. A computerized random-number generator produced the sequence. Randomization was undertaken in permuted blocks of four to decrease allocation predictability. Participants were randomized after obtaining baseline data.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind the expert trauma nurse who administered the intervention, considering that she delivered the iPACT-E-Trauma sessions. Precautions were taken to prevent contamination of the control group participants and of the nursing staff. In this regard, the intervention and the educational pamphlet were given to participants in private hospital rooms, in an office, or in hospital rooms in which no other patients with major ET were present at the time of intervention sessions. Moreover, no information was provided on the intervention content to the nursing staff. The research assistant (RA) who entered data was blinded to group assignment.

Data Analysis

Feasibility of the Research Methods

Descriptive data were gathered to document key methodological parameters [42,51,77], including 1) the number of eligible patients and number of participants included; 2) the mean time required to screen participants, recruit them, and obtain consent and baseline data; 3) the percentage of patients who agreed to be randomized to either the experimental or control group; 4) the dropout rate for each intervention session and outcome measure time points; 5) rates of questionnaires completed in full; 6) mean time between expected dates for questionnaire completion and actual completion; and 7) number of reminder calls for questionnaire completion. Descriptive data on the difficulties experienced during screening procedures and in obtaining consent and baseline data from patients were collected and the content analyzed. Frequency tables were constructed for each category.

Potential Efficacy of the iPACT-E-Trauma Intervention

All outcome data were analyzed via an intent-to-treat approach. Data entry was double-verified by a research assistant to ensure accuracy. Data cleaning involved analyses of the frequency distributions to verify adequate data coding and presence of outliers. These analyses revealed no outlier on any of the variables. The baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the experimental and control groups were compared using parametric and nonparametric tests, depending on the types of variables and their distribution (i.e., t test, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square test, Fisher exact test). To detect within and between differences in continuous primary and secondary outcomes, as well as complementary outcomes over time (T0, T7, T8), linear mixed models for repeated measures were performed. Moreover, the rates of participants with high-intensity pain and pain interference with activities (≥4/10 on a 0–10 NRS) [44] at T7 and T8 and with scores suggesting a high risk for developing chronic pain at T0 were calculated. Categorical outcomes such as the PGIC, return to work, the presence of PTSD symptoms at T7 and T8, and analgesic consumption at six weeks postinjury were compared between the two groups using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Results

Feasibility of the Research Methods

Regarding the adequacy of the sampling pool and recruitment time, 37% of screened patients were included in the study (56 patients from a total of 150). Among those eligible to participate, 85% provided consent. Recruitment took slightly longer than the initial estimation (i.e., nine months instead of seven).

Potential participants were easily screened from a list of orthopedic trauma patients, updated daily by the medical team. Almost half (47%) of the screened patients were noneligible, primarily owing to their clinical condition (e.g., moderate to severe TBI, prolonged mechanical ventilation), which limited participation, or their type of injury (i.e., minor ET and concomitant trauma associated with high-intensity pain). Gathering consent and baseline data took 24 to 48 hours postadmission on average. Delays obtaining consent were mainly due to patient drowsiness secondary to opioid administration and anesthesia (21%). There was no difficulty with randomization, and all participants accepted their group assignment. Attrition rates for outcome measures at six months were under 20% (11% in the experimental group and 18% in the control group).

Regarding ease of data collection, the majority of the participants completed the baseline (88%), three-month (92%), and six-month (93%) questionnaires measuring the primary outcomes (i.e., BPI) and the secondary outcomes (i.e., PSEQ, CPAQ, PCS, TSK, HADS). Among the complementary variables (i.e., PGIC, SF-12v2, PCL-5), the SF-12v2 questionnaire was removed from the baseline package (after being completed by the first eight patients included in the study), but not at T7 and T8, to reduce the time needed to gather data early after the injury. A research assistant was present to assist participants completing baseline questionnaires in almost 80% of cases. There was no identifiable pattern in terms of incomplete questionnaires and nonanswered questions, whether they were completed in hard copy or electronically. The questionnaires at three and six months were completed a week later than expected and required one call reminder, on average, for each time point.

Health care service utilization was not measured as initially planned because most participants did not complete the Medical Attention Seeking and Professional Services Utilization Logbook. Furthermore, there were some difficulties in the measurement of analgesic consumption after hospital discharge. Indeed, although we aimed to calculate the number of milligrams of each analgesic taken over a six-week period, we were only able to document whether participants were still consuming analgesics based on data collected from participants discharged home or during a participant follow-up appointment with their orthopedic surgeon.

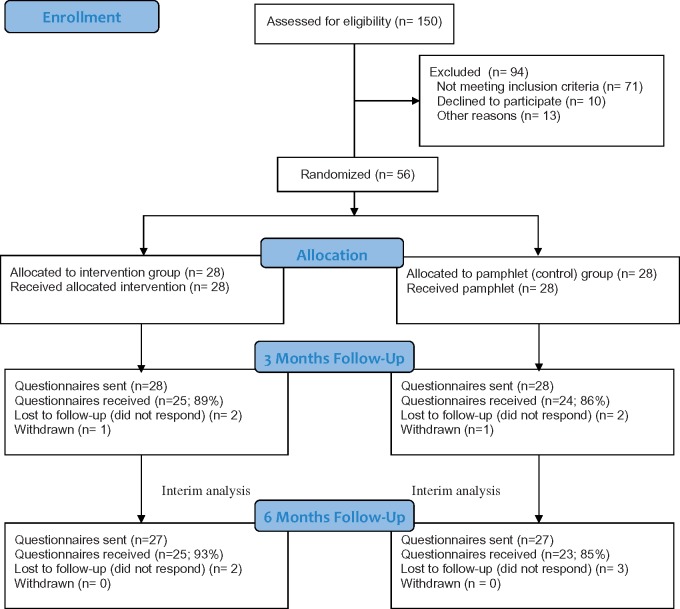

Participant Flow

Recruitment started September 2016 and ended June 2017. Among a total of 150 screened participants (Figure 1 ), 94 were excluded. Amongst the excluded patients, 71 did not meet the inclusion criteria. The most common cause for exclusion was cognitive impairment, secondary to a moderate to severe TBI or a mental health disorder (N = 27), followed by not speaking French (N = 12) and needing more than seven days of hospitalization before being eligible (N = 11). Also, 13 patients were found ineligible because of medical complications limiting their capacity to participate (N = 7), early discharge to the trauma referral center (N = 4), and death (N = 2). Moreover, 10 patients declined to participate because of the stress associated with the trauma event (N = 8) or low interest in self-management activities (N = 2). From the 56 participants included at baseline, outcome measures were gathered for 49 participants (25 for the experimental group and 24 for the control group) at three months and for 48 at six months (25 for the experimental group and 23 for the control group). Loss to follow-up was due to noncompletion of the three- and six-month questionnaires. Two participants discontinued the intervention after session 4 because of cellular phone service disconnection and a lack of motivation after hospital discharge. One participant from each group withdrew from the study within three months postinjury without providing an explanation.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Characteristics of the Sample

Most baseline characteristics were similar for the experimental and control groups. More than 50% of participants were Caucasian males (Table 2). Those in the experimental group were significantly older than those in the control group (mean = 47 vs 38 years old). Approximately half of the participants had at least a college diploma. The main occupation was laborer (22.0% in the experimental group and 32.0% in the control group), and more than 50% had an annual income <$50,000.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic data

| iPACT-E-Trauma Group (N = 28) | Pamphlet Group (N = 28) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 15 (54) | 19 (68) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47 (19)* | 38 (14) |

| Ethnical group, No. (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 23 (82) | 21 (74) |

| Haitian | 3 (11) | 3 (11) |

| Arabic | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Asian | – | 1 (4) |

| African | – | 2 (7) |

| Level of education, No. (%) | ||

| <college diploma | 13 (46) | 12 (43) |

| ≥ college diploma | 15 (54) | 16 (57) |

| Occupation, No. (%) | ||

| Laborer | 6 (22) | 9 (32) |

| Clerical work | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Administration | 4 (14) | 3 (11) |

| Professional | 4 (14) | 8 (29) |

| Student | 2 (7) | 4 (14) |

| None | 4 (14) | 2 (7) |

| Retired | 6 (22) | – |

| Annual income, No. (%) | ||

| <$50,000 | 20 (71) | 16 (57) |

| ≥$50,000 | 8 (29) | 12 (43) |

* P < .05.

Regarding the types of injury (Table 3), the primary trauma mechanism was a fall for the experimental group (46.0%) and a motor vehicle accident for the control group (32.0%). Fewer than 20% of participants were intoxicated, according to ethanol blood level, toxicology screening, and emergency physician health questionnaire upon arrival to the emergency room. Both groups had a median of two fractures of the lower extremities. More concomitant injuries were documented in the control group (50.0% in the experimental group and 64.0% in the control group), with a significant difference for mild TBI (14.0% vs 43.0%). The mean ISS [64] score was also significantly higher in the control group (9.4 vs 14.1), but orthopedic injury severity, as measured by the AIS [65], was similar between both groups (mean = 2.5 vs 2.6). Only a third of participants in each group had comorbidities that could have triggered the development of chronic pain, such as somatic or visceral pain before the injury, as well as anxiety and depression symptoms.

Table 3.

Participants’ injuries and treatments received

| iPACT-E-Trauma Group (N = 28) | Pamphlet Group (N = 28) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trauma mechanism, No. (%) | ||

| Motor vehicle crash | 8 (29) | 10 (32) |

| Pedestrian collision | 3 (11) | 4 (14) |

| Fall | 13 (46) | 8 (29) |

| Sport | 3 (11) | 6 (21) |

| Work | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Types of orthopedic injuries, No. (%) | ||

| Pelvis | 12 (43) | 11 (39) |

| Acetabulum | 9 (34) | 4 (14) |

| Femur | 8 (29) | 10 (36) |

| Knee joint | 2 (7) | 5 (18) |

| Tibia | 8 (29) | 9 (32) |

| Fibula | 7 (25) | 7 (25) |

| Ankle | 5 (18) | 5 (18) |

| Foot | 4 (14) | 2 (7) |

| Open fracture | 3 (11) | 4 (15) |

| Joint dislocation | 13 (46) | 9 (32) |

| Soft tissue involvement | 16 (57) | 15 (54) |

| Number of fractures, median (min–max) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–5) |

| Other injuries, No. (%) | ||

| Participants with at least 1 concomitant injury | 14 (50) | 18 (64) |

| Mild traumatic brain injury | 4 (14) | 12 (43)* |

| Upper extremities | 6 (22) | 10 (36) |

| Thorax | 2 (7) | 8 (29) |

| Abdomen | 3 (11) | 2 (7) |

| Spine | 5 (18) | 9 (32) |

| ISS, mean (SD) | 9.4 (6) | 14.1 (8)* |

| AIS, mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.6) |

| AIS–Orthopedic score, No. (%) | ||

| AIS 1 (minor extremity injury) | – | – |

| AIS 2 (moderate extremity injury) | 15 (54) | 11 (39) |

| AIS 3 (serious extremity injury) | 11 (40) | 16 (57) |

| AIS 4 (severe extremity injury, life-threatening) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Intoxication at the time of injury | 5 (18) | 3 (11) |

| Compensable injury | 15 (54) | 17 (61) |

| Comorbidities that may impact chronic pain (somatic or visceral pain before the injury, mobility issue requiring technical aid before the injury, mental health issues), No. (%) | 9 (32) | 7 (25) |

| Treatments,† No. (%) | ||

| Open reduction and internal fixation | 26 (93) | 26 (93) |

| Closed reduction and external fixation | 8 (29) | 7 (25) |

| Conservative treatment (no surgery) | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Immobilization with a cast or an orthosis | 11 (39) | 8 (29) |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 14 (50) | 16 (57) |

| Analgesics intake at 6 wk postinjury, No. (%) | 21 (78)‡ | 21 (78)§ |

| Opioids | 12 (44) | 14 (52) |

| Acetaminophen | 19 (70) | 21 (78) |

| Pregabalin | 4 (15) | 1 (4) |

| NSAID | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Weight-bearing limitation postinjury, No. (%) | ||

| No limitation | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| 6 wk postinjury | 14 (50) | 16 (57) |

| 3 mo postinjury | 10 (36) | 10 (36) |

| 6 mo postinjury | 3 (11) | 1 (4) |

| Neuropathic pain postinjury | 5 (19)‡ | 5 (17)¶ |

| Normal fracture and soft tissue healing, No. (%) | ||

| 1 mo postinjury | 20 (71) | 21 (78)‡ |

| 3 mo postinjury | 24 (86) | 21 (86)|| |

| 6 mo postinjury | 26 (100) | 17 (94)||| |

AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale; ISS = Injury Severity Score; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent.

* P < .05.

†Some participants received more than one treatment.

‡Percentage calculated from 27 participants.

§Percentage calculated from 21 participants.

¶Percentage calculated from 23 participants.

||Percentage calculated from 24 participants.

|||Percentage calculated from 18 participants evaluated by an orthopedic surgeon at six months postinjury.

More than 90% of participants in both groups needed a surgery, and prolonged (three to six months) weight-bearing limitation on the injured limb was prescribed in almost 40%. Three-quarters of participants were still taking analgesics at six weeks postinjury, and among those, about 50% were still taking opioids. More than half of the participants in the experimental group reported minimal use of opioids (i.e., two or fewer doses per day) during the intervention session six weeks postinjury. However, due to administrative difficulties, the information on opioid dosage was not accessible for the control group in rehabilitation centers. It was therefore not possible to quantify opioid use at six weeks postinjury in the control group.

Potential Efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma up to Six Months Postinjury

Primary Outcomes

As shown in Table 4, participants from the experimental and control groups had moderate average pain intensity (NRS ≥ 4–6/10) and severe pain interference with daily living activities (NRS ≥ 7/10) on average at T0, whereas mild scores (NRS < 4/10) [44] were recorded at T7 and T8. The percentage of participants in the experimental and control groups who reported moderate to severe pain intensity and pain interference with activities of daily living (NRS ≥ 4/10) on average at T7 and T8 varied between 20% and 30%. The worst pain experienced by participants was severe (NRS ≥ 7/10) in both groups at T0 and moderate at T7 and T8 (NRS ≥ 4–6/10). Also, the experimental group and control group participants stated that pain severely interfered with their mobility (NRS ≥ 7/10) at T0, and mildly interfered (NRS < 4/10) at T7 and T8.

Table 4.

Improvements in the experimental (iPACT-E-Trauma) and pamphlet groups up to six months postinjury

| Baseline (T0) |

End of the Intervention: 3 mo Postinjury (T1) |

6 mo Postinjury (T2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Outcomes† | iPACT-E-Trauma Group, Mean (SD) | Pamphlet Group, Mean (SD) | iPACT-E-Trauma Group, Mean (SD) | Pamphlet Group, Mean (SD) | iPACT-E-Trauma Group, Mean (SD) | Pamphlet Group, Mean (SD) |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Pain intensity on the average in the past 7 d (NRS: 0–10) | 6.30 (2.3) | 6.20 (2.4) | 2.32 (2.2) | 2.42 (2.1) | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.1 (2.4) |

| Pain interference with activities in the past 7 d (NRS: 0–10) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.5 (1.7) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.85 (2.4) | 2.2 (2.5) | 2.2 (2.5) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Total pain self-efficacy score (0–49) | 22.7 (11.0) | 16.6 (8.2)* | 43.6 (13.6) | 42.6 (15.5) | 48.0 (12.7) | 44.8 (16.0) |

| Total CPAQ score (0–48) | 18.0 (6.1) | 18.3 (7.3) | 28.1 (7.7) | 27.7 (6.7) | 29.3 (8.8) | 28.2 (8.6) |

| Total PCS score (0–52) | 24.7 (13.3) | 23.0 (13.1) | 10.2 (10.6) | 9.3 (9.4) | 16.4 (14.4) | 11.4 (11.6) |

| Total TSK score (17–68) | 45.0 (6.8) | 47.9 (8.6) | 38.3 (7.7) | 41.9 (7.4) | 36.5 (10.1) | 39.5 (10.5) |

| HADS-A subscale (0–21) | 8.3 (5.0) | 8.9 (4.1) | 6.4 (4.6) | 5.6 (3.5) | 6.1 (5.0) | 6.0 (3.7) |

| HADS-D subscale (0–21) | 7.6 (4.6) | 8.4 (4.8) | 4.0 (3.4) | 4.2 (3.5) | 3.3 (3.6) | 4.1 (4.1) |

| Global complementary outcomes | ||||||

| SF-12v2 Physical Component Summary (0–100) | – | – | 53.7 (24.9) | 46.7 (21.6) | 61.3 (25.9) | 57.1 (26.0) |

| General health (0–100) | – | – | 62.0 (19.8) | 59.8 (21.0) | 66.3 (23.4) | 62.5 (22.1) |

| Physical functioning (0–100) | – | – | 43.5 (35.5) | 35.9 (34.4) | 52.2 (36.9) | 51.0 (40.7) |

| Bodily pain (0–100) | – | – | 65.2 (32.6) | 58.0 (28.2) | 69.6 (28.2) | 64.6 (32.1) |

| Role physical (0–100) | – | – | 44.2 (35.0) | 36.6 (24.3) | 57.1 (32.4) | 50.2 (30.6) |

| Mental Health Component Summary (0–100) | – | – | 67.7 (23.5) | 67.2 (18.0) | 69.1 (23.7) | 69.2 (22.5) |

| Role emotional (0–100) | – | – | 68.7 (27.4) | 70.6 (31.6) | 71.4 (30.6) | 64.1 (36.1) |

| Vitality (0–100) | – | – | 62.5 (22.8) | 64.8 (19.9) | 58.7 (20.8) | 65.6 (21.9) |

| Mental health (0–100) | – | – | 69.6 (21.4) | 74.1 (15.5) | 72.5 (23.2) | 69.0 (24.0) |

| Social functioning (0–100) | – | – | 70.7 (35.1) | 59.1 (35.8) | 73.9 (31.5) | 78.1 (24.8) |

BPI = Brief Pain Inventory; CPAQ-8 = Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire–eight items; DN4 = Douleur Neuropathique 4; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PCL-5 = Post-Traumatic Syndrome Disorder Checklist–Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5; PGIC = Patient Global Impression of Change; PSEQ = Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire; PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; SF-12v2 = Short-Form–12 items, version 2; TSK = Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia.

* P < .05.

†Data are presented as mean ± SD values.

Secondary Outcomes

Regarding protective factors for chronic pain, pain self-efficacy was low at baseline, especially for the control group (PSEQ score < 17) [55]. Mean scores (PSEQ > 40) indicated high PSE at T7 and T8. Findings also showed that participants from the experimental and control groups had low pain acceptance (CPAQ-8 score < 20) [57] at baseline, but mean scores improved at T7 and T8. Regarding risk factors, high pain-related fear (TSK score ≥ 37) [78] was identified at baseline, and mean scores were still high at six months postinjury. Low mean pain catastrophizing (PCS score < 30) [79], anxiety (HADS-A score ≤ 10), and depression (HADS-D score ≤ 10) [62] scores were obtained at T0, T7, and T8. Approximately 40% of participants in both groups presented high pain catastrophizing scores at baseline (PCS score ≥ 30), whereas 20% to 30% had high anxiety and depression scores (HADS > 10).

Less than half of the participants (32.0% in the experimental group and 40.0% in the control group) returned to work at six months postinjury. About a third of participants who returned to work had the same responsibilities as before the injury (37.5% in the experimental group and 33.3% in the control group).

Complementary Global Outcomes

A higher rate of participants from the experimental group perceived considerable improvement in pain (60.0% in the experimental group vs 46.0% in the control group), quality of life (40.0% vs 21.0%), and global condition (44.0% vs 25.0%) at T7 (Table 5). This positive trend was not maintained at T8.

Table 5.

Participants’ global impression of change up to six months postinjury

| 3 mo Postinjury (T7) |

6 mo Postinjury (T8) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | iPACT-E-Trauma Group, No. (%) | Pamphlet Group, No. (%) | iPACT-E-Trauma Group, No. (%) | Pamphlet Group, No. (%) |

| Pain | ||||

| Considerably improved | 15 (60) | 11 (46) | 13 (59) | 16 (70) |

| Moderately improved | 8 (32) | 11 (46) | 7 (32) | 5 (22) |

| Minimally improved | 2 (8) | — | 2 (9) | 2 (9) |

| Functioning | ||||

| Considerably improved | 12 (48) | 11 (46) | 15 (63) | 15 (63) |

| Moderately improved | 10 (40) | 10 (42) | 5 (21) | 4 (17) |

| Minimally improved | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 4 (17) | 2 (8) |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Considerably improved | 10 (40) | 5 (21) | 8 (33) | 8 (33) |

| Moderately improved | 5 (20) | 10 (42) | 9 (38) | 9 (38) |

| Minimally improved | 7 (28) | 4 (17) | 3 (13) | 2 (8) |

| Global condition | ||||

| Considerably improved | 11 (44) | 6 (25) | 8 (33) | 9 (38) |

| Moderately improved | 7 (28) | 10 (42) | 12 (50) | 9 (38) |

| Minimally improved | 6 (24) | 5 (21) | 2 (8) | 4 (17) |

Participants from both groups showed below-average mean scores (SF-12v2 ≤ 50) [80] on physical functioning and physical role subscales as well as on the Physical Component Summary Scale at T7 (Table 4). Experimental group participants reported better physical status overall than the control group at T7 and T8 (mean scores of 53.7 vs 46.7 and 61.3 vs 57.1).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the feasibility of the research methods associated with the testing of iPACT-E-Trauma intervention and its potential efficacy for the prevention of chronic pain. Several aspects of the research methods were found to be feasible, including the ease of screening potential participants, the high rates of participation and agreement to be randomized either to the experimental or control group, the low dropout and attrition rates at the end of the study in both groups, and the ease of data collection for most outcomes. We also identified some challenges, such as the high rate of screened patients not eligible to participate, the time needed to recruit and to obtain consent and baseline data, and the difficulties experienced when collecting data on health care service utilization and analgesic consumption.

Regarding the potential efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma, findings showed mild average pain intensity and pain interference with activities of daily living (i.e., primary outcomes; NRS < 4/10) [44] for both groups at three months and six months postinjury. Most of risk factors for chronic pain did not reach clinically relevant levels from baseline to the end of the study in the experimental and control groups. Low protection against chronic pain (i.e., pain self-efficacy and pain acceptance) was observed in both groups at baseline, but this improved over time. Moreover, the proportion of participants who did not return to work at six months postinjury was large and was comparable in both groups.

These study findings point to the adjustments needed to progress from pilot study to clinical trial. In this regard, the sampling pool of potential participants should be drawn from several trauma centers to reach the required patient sample in a shorter time interval. Furthermore, recruitment should occur during the summer and fall, the seasons associated with the highest volume of trauma admissions [81–83]. Moreover, considering that approximately 60% of patients with extremity trauma regularly suffer from various other types of injuries [83], the scope of the intervention should be reconsidered in order to expand eligibility criteria.

The number of outcome questionnaires should be reduced in a future study to facilitate baseline data collection early after injury and potentially decrease the attrition rate associated with measurement burden [84]. The precision and accuracy of the measurement tools for finding differences between the experimental and control groups should also be considered. The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) for chronic pain prevention trials [45] recommended measuring the following outcomes in the perioperative and postsurgical recovery phases: presence vs absence of clinically meaningful pain, pain intensity at rest and upon movement, pain quality such as the presence or absence of neuropathic pain, and secondary end points, including physical and emotional functioning. The efficacy of the 0–10 NRS to measure pain treatments, like the one used in this study, has been criticized for its inability to determine whether an intervention makes a real difference in the everyday life of an individual [85]. Recently, the US Health and Human Services (HHS)–Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee [86] proposed a National Pain Strategy, aiming to guide efforts in the prevention of the progression from acute to chronic pain. To accomplish this goal, the HHS called for the use of pain assessment tools that take into account the intermittent quality of chronic pain and that differentiate high-impact chronic pain (i.e., pain associated with significant restriction in self-care and social life) from less disabling forms of pain. To this end, they developed a pain screener that allows identification of the presence of pain on at least half the days over a six-month period and quantification of chronic pain severity in terms of its impact [86]. The predictive validity of this tool has been established in a study showing that relative to persons with low-impact chronic pain, those with high-impact chronic pain were more frequent users of health care resources, reported lower quality of life, and reported greater pain-related interference with activities [87]. Despite that the reliability and the validity of the tool still need to be established, its use to evaluate the efficacy of chronic pain–preventive interventions appears promising. This tool could be combined with a global outcome measure, such as the SF-12v2, in a future RCT. These outcomes could be measured up to a minimum of 12 months postinjury in order to evaluate the participants’ pain experience until they have more fully returned to their pre-injury level of activity including work [45].

To further optimize study methods, the processes to measure health care service utilization and analgesic consumption including opioids should be simplified. Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [88] and the HHS [87] used data from the National Health Interview Survey and electronic health care record to develop metrics to assess progress in reducing chronic pain impact. To facilitate comparison of findings with population-based data, those metrics could be used when testing the effects of iPACT-E-Trauma on treatment and service utilization. For example, general questions to determine if patients have seen or talked to various health professionals about their pain over the last 12 months are included in the National Health Interview Survey [88]. However, such questions should be modified in the context of iPACT-E-Trauma testing to exclude the hospitalization period. Moreover, opioid consumption could be evaluated by determining if participants took opioids during 70 or more days in at least one 90-day period in a year, which corresponds to a chronic consumption as defined by the HHS [87].

Descriptive data on study outcomes could also help shape the design of a future clinical trial. Indeed, findings have indicated that, despite experiencing high-intensity pain and pain interference with activities of daily living at baseline, participants might have been at low risk of developing chronic pain, given the low scores for these outcome measures observed at three months and six months postinjury. However, 54% of participants in the experimental group and 39% in the control group had injuries of moderate severity, according to their AIS score [67], whereas the development of chronic pain has been mainly found in patients with more serious lower extremity injuries (AIS ≥ 3) [5,29]. For the present study, AIS scores were calculated retrospectively by trauma registry archivists and were therefore not available at the time of study inclusion. A procedure to estimate the AIS early after the injury should be established for the definitive RCT.

Likewise, low scores were obtained for three recognized risk factors in the transition from acute to chronic pain: pain catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression [89,90]. Recent studies on the prevention of chronic pain after major surgery [22] and in the acute orthopedic trauma context [13] showed greater improvement in participants with poorer mental health conditions. Therefore, psychological measures (i.e., pain catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression) should be used to target trauma patients who are at higher risk to develop chronic pain. Moreover, considering that the high-intensity pain risk factor could be affected by its proximity with the injury timing, stepped screening could be used during the subacute pain phase, that is, continuing the study only in those patients still presenting high pain intensity at 10 days to six weeks postinjury. In this regard, high-intensity subacute pain was found to be associated with chronic pain at 12 months after hospital discharge in a surgical orthopedic population [91]. The 2016 National Health Interview Survey showed that 20.4% of US adults had chronic pain and 8.0% had high-impact chronic pain [88]. Hence, targeting patients presenting higher risk for chronic pain and still reporting significant pain after a few weeks postinjury may lead to recruitment of more participants with debilitating chronic pain in future studies. Recruiting such participants could contribute to the implementation of more cost-effective approaches for the prevention of chronic pain by offering treatments to individuals who need them the most [92].

Contamination bias [93], placebo, and spontaneous recovery effects could also have contributed to comparable results in both groups throughout follow-up. For example, the nursing staff might have observed that participants in the experimental group were asked more frequently about the implementation of pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain management strategies (e.g., use of co-analgesia and application of ice on injury), which could have led nurses to offer these strategies on a more regular basis to participants in the control group as well. In light of this, conducting a parallel group cluster RCT, in which groups of patients in various hospitals would be randomized instead of patients themselves [94], would be an appropriate alternative. This type of study design has been used in many recent educational and self-management studies on pain, where the behavior of health care providers was at risk of an intervention bias or when it was difficult to blind the control group to the treatment [95–100].

Answering questions from the control group participants with regard to the information pamphlet content could have created some sort of placebo effect [101–103]. Placebo interventions have been shown to influence the effect of treatment on pain scores by a standardized mean difference (SMD) of –0.17 (95% confidence interval [CI] = –0.32 to –0.02) to –0.25 (95% CI = –0.35 to –0.16) [104]. The same applies for spontaneous recovery, which can reach an SMD of –0.53 (95% CI = –1.03 to –0.02) in the acute pain context, as opposed to an SMD of –0.10 (95% CI = –0.27 to 0.06) in chronic pain studies [105]. In this respect, even though a preventive intervention would intuitively appear more effective than an intervention aimed at treating chronic pain, the calculation of the sample size needed for a full-scale RCT should take into account placebo and spontaneous recovery effects. Hence, assuming a standardized effect size of 0.20, 80% power, and 5% significance level, a sample size of about 785 participants would be required [74]. A three-arm RCT (i.e., active treatment, placebo, and no treatment) could also be considered in a future larger study, acknowledging the effect of iPACT-E-Trauma intervention while taking into account spontaneous recovery.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This pilot RCT is the first to have assessed the feasibility of the research methods and potential efficacy of a self-management intervention for the prevention of chronic pain applied early after a traumatic injury. A high incidence of chronic pain has been repeatedly reported over the last 10 years in patients with major lower ET. Chronic pain negatively impacts all dimensions of ET patients’ lives while being associated with a high socioeconomic burden. Nonetheless, there have been no proposed effective interventions to prevent the problem, while evidence in other populations is still scarce. This study was a milestone in resolving this issue as it provided key information on the methodological approaches that should be adjusted or incorporated in the design of a full-scale RCT to test the efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma. Study findings also underscore some important considerations for the evaluation of interventions aimed at preventing development of high-impact chronic pain.

In terms of limitations, although differences between experimental and control groups were evaluated in the present study, no inference can be made on the efficacy of iPACT-E-Trauma. Statistical tests were only performed to gather information on participant scores associated with various pain outcomes and their evolution over time [43]. Furthermore, despite the fact that several recommendations were made to increase the feasibility of the research methods, some methodological features could be more complex to implement in a definitive RCT. They include screening patients at risk of chronic pain according to psychological outcome measures, selecting patients with severe injuries, recruiting the appropriate sample size to reach adequate statistical power in the context of a condition with a high rate of spontaneous recovery, and the implementation of a parallel group cluster RCT.

Conclusions

This study showed that many methodological parameters to evaluate the effects of iPACT-E-Trauma were feasible, such as the high percentage of patients who agreed to participate and the low attrition rate at the end of the study. Other parameters need to be addressed before conducting a full-scale RCT, including the small percentage of screened patients who were eligible to participate and the time needed for the recruitment and for obtaining baseline data. Findings on outcome measures from baseline to six months postinjury also indicated the need to select more precise tools to measure the transition toward chronic pain, to recruit patients with more severe injury and higher psychological vulnerability, and to implement methodological strategies to control for the contamination bias, placebo, and spontaneous recovery effects. Making these adjustments will increase the likelihood of demonstrating the potential benefits of chronic pain–preventive interventions such as the iPACT-E-Trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Laurence Lemay Belisle, Annick Gagné, and Karine Tardif (Research Assistants) for their support in data collection and compilation.

Funding sources: The first author (MB) has received fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MFE-140934), Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQ-S; 30244), and Réseau de Recherche en Sciences Infirmières du Québec (no reference number was provided) to conduct this research project. The authors received a grant from the Quebec Pain Research Network of FRQ-S (no reference number was provided) for the development of Soulage TAVIE Post-Trauma and preliminary testing in web sessions.

Disclosure and conflicts of interest: None to declare in relation to article content.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Pain Medicine online.

References

- 1. Jenewein J, Moergeli H, Wittman L et al. Development of chronic pain following severe accidental injury. Results of a 3-year follow-up study. J Psychosom Res 2009;662:119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williamson OD, Epi GD, Gabbe BJ. Predictors of moderate or severe pain 6 months after orthopaedic injury: A prospective cohort study. J Orthop Trauma 2009;232:139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agence de la Santé et Des Services Sociaux de Montréal. Cadre de Référence: Services Posthospitaliers en Réadaptation Fonctionnelle Intensive en Interne et Soins Subaigus Pour la Région de Montréal. Montreal, Canada: Agence de la Santé et Des Services Sociaux de Montréal; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aitken LM, Chaboyer W, Kendall E, Burmeister E. Health status after traumatic injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;726:1702–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castillo RC, MacKenzie EJ, Wegener ST, Bosse MJ. Prevalence of chronic pain seven years following limb threatening lower extremity trauma. Pain 2006;1243:321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clay FJ, Newstead SV, Watson WL et al. Bio-psychosocial determinants of persistent pain 6 months after non-life-threatening acute orthopaedic trauma. J Pain 2010;115:420–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmes A, Williamson O, Hogg M et al. Predictors of pain 12 months after serious injury. Pain Med 2010;1111:1599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Archer KR, Castillo RC, Wegener ST, Abraham CM, Obremskey WT. Pain and satisfaction in hospitalized trauma patients: The importance of self-efficacy and psychological distress. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;724:1068–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ebel BE, Mack C, Diehr P, Rivara FP. Lost working days, productivity, and restraint use among occupants of motor vehicles that crashed in the United States. Inj Prev 2004;105:314–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kendrick D, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C et al. Getting back to work after injury: The UK Burden of Injury multicentre longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF et al. Early predictors of long-term work disability after major limb trauma. J Trauma 2006;613:688–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Donnell ML, Varker T, Holmes AC et al. Disability after injury: The cumulative burden of physical and mental health. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;742:e137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vranceanu AM, Hageman M, Strooker J et al. A preliminary RCT of a mind body skills based intervention addressing mood and coping strategies in patients with acute orthopaedic trauma. Injury 2015;464:552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gatchel RJ, Stowell AW, Wildenstein L, Riggs R, Ellis E 3rd. Efficacy of an early intervention for patients with acute temporomandibular disorder-related pain: A one-year outcome study. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;1373:339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hasenbring M, Ulrich HW, Hartmann M, Soyka D. The efficacy of a risk factor-based cognitive behavioral intervention and electromyographic biofeedback in patients with acute sciatic pain. An attempt to prevent chronicity. Spine 1999;2423:2525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hay EM, Mullis R, Lewis M et al. Comparison of physical treatments versus a brief pain-management programme for back pain in primary care: A randomised clinical trial in physiotherapy practice. Lancet 2005;3659476:2024–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linton SJ, Andersson T. Can chronic disability be prevented? A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavior intervention and two forms of information for patients with spinal pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;2521:2825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linton SJ, Ryberg M. A cognitive-behavioral group intervention as prevention for persistent neck and back pain in a non-patient population: A randomized controlled trial. Pain 2001;901:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Linton SJ, Boersma K, Jansson M, Svärd L, Botvalde M. The effects of cognitive-behavioral and physical therapy preventive interventions on pain-related sick leave: A randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2005;212:109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slater MA, Weickgenant AL, Greenberg MA et al. Preventing progression to chronicity in first onset, subacute low back pain: An exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;904:545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Von Korff M, Moore JE, Lorig K et al. A randomized trial of a lay person-led self-management group intervention for back pain patients in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;2323:2608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abid Azam M, Weinrib AZ, Montbriand J et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to manage pain and opioid use after major surgery: Preliminary outcomes from the Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service. Can J Pain 2017;11:37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore JE, Von Korff M, Cherkin D, Saunders K, Lorig K. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for enhancing back pain self care in a primary care setting. Pain 2000;882:145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenbloom BN, Khan S, McCartney C, Katz J. Systematic review of persistent pain and psychological outcomes following traumatic musculoskeletal injury. J Pain Res 2013;6:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenbloom BN, Katz J, Chin KY et al. Predicting pain outcomes after traumatic musculoskeletal injury. Pain 2016;1578:1733–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clay FJ, Watson WL, Newstead SV, McClure RJ. A systematic review of early prognostic factors for persisting pain following acute orthopedic trauma. Pain Res Manag 2012;171:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holtslag HR, van Beeck EF, Lindeman E, Leenen LP. Determinants of long-term functional consequences after major trauma. J Trauma 2007;624:919–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hours M, Bernard M, Charnay P et al. Functional outcome after road-crash injury: Description of the ESPARR victims cohort and 6-month follow-up results. Accid Anal Prev 2010;422:412–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rivara FP, Mackenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ et al. Prevalence of pain in patients 1 year after major trauma. Arch Surg 2008;1433:282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vles WJ, Steyerberg EW, Essink-Bot ML et al. Prevalence and determinants of disabilities and return to work after major trauma. J Trauma 2005;581:126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;692:153–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jensen MP, Turk DC. Contributions of psychology to the understanding and treatment of people with chronic pain: Why it matters to ALL psychologists. Am Psychol 2014;692:105–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flor H, Turk DC. Chronic Pain: An Integrated Biobehavioral Perspective. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turk DC, Flor H. The cognitive-behavioral approach to pain management. In: McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, eds. Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. London: England: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2006:339–348. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of Self-Care and Associated Concepts. J Nurs Scholar 2011;433:255–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bérubé M, Gélinas C, Martorella G et al. A hybrid web-based and in-person self-management Intervention to Prevent Acute to Chronic Pain Transition After Major Lower Extremity Trauma (iPACT-E-Trauma): Protocol for a pilot single-blind randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;66:e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bérubé M, Gélinas C, Martorella G et al. Development and acceptability assessment of a self-management intervention to prevent acute to chronic pain transition after major lower extremity trauma. Pain Manag Nurs 2018;196:671–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L et al. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2:CD010152.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martorella G, Côté J, Racine M, Choinière M. Web-based nursing intervention for self- management of pain after cardiac surgery: Pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lustria ML, Noar SM, Cortese J et al. Meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J Health Commun 2013;189:1039–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bérubé M, Gélinas C, Feeley N et al. A hybrid web-based and in-person self-management intervention aimed at preventing acute to chronic pain transition after Major Lower Extremity trauma: Feasibility and acceptability of iPACT-E-Trauma. JMIR Res Protoc 2018;2:e10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sidani S, Braden CJ. Design, Evaluation, and Translation of Nursing Interventions. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gerbershagen HJ, Rothaug J, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Determination of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain on the numeric rating scale: A cut-off point analysis applying four different methods. B J Anaesth 2011;1074:619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gewandter JS, Dworkin RH, Turk DC et al. Research design considerations for chronic pain prevention clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2015;1567:1184–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Unsworth A, Curtis K, Asha SE. Treatments for blunt chest trauma and their impact on patient outcomes and health service delivery. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015;231:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ et al. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: A prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2013;1184:934–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974;27872:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Côté J, Ramirez-Garcia P, Rouleau G et al. A nursing virtual intervention: Real-time support for managing antiretroviral therapy. Comput Inform Nurs 2011;291:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martorella G, Côté J, Choinière M. SOULAGE-TAVIE: Development and validation of a virtual nursing intervention to promote self-management of postoperative pain after cardiac surgery. Comput Inform Nurs 2013;314:189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Polit D, Hungler B. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cleeland C. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide. Houston, TX: The University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain 1995;612:277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Poundja J, Fikretoglu D, Guay S, Brunet A. Validation of the French version of the Brief Pain Inventory in Canadian veterans suffering from traumatic stress. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;336:720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;112:153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aguerre C, Bridou M, Le Gall A et al. Analyse préliminaire des qualités psychométriques de la version Française du Questionnaire d’Auto-Efficacité envers la Douleur. Douleurs 2012;13(S1):A94. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fish RA, McGuire B, Hogan M, Morrison TG, Stewart I. Validation of the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ) in an Internet sample and development and preliminary validation of the CPAQ-8. Pain 2010;1493:435–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assess 1995;74:524–32. [Google Scholar]

- 59. French DJ, Noël M, Vigneau F et al. PCS-CF: A French-language, French-Canadian adaptation of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Can J Behav Sci 2005;373:181–92. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kori S, Miller R, Todd D. Kinesiophobia: A new view of chronic pain behaviour. Pain Manag 1990;3:35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 61. French DJ, Roach PJ, Mayes S. Peur du mouvement chez des accidentes du travail: L'Echelle de Kinesiophobie de Tampa (EKT). Can J Behav Sci 2002;341:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;676:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Savard J, Laberge B, Gauthier JG, Ivers H, Bergeron MG. Evaluating anxiety and depression in HIV-infected patients. J Pers Assess 1998;713:349–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Roberge P, Doré I, Menear M et al. A psychometric evaluation of the French Canadian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a large primary care population. J Affect Disord 2013;147(1–3):171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baker S, Oneill B, Haddon W et al. The injury severity score: A method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974;143:187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Palmer C. Major trauma and the Injury Severity Score - where should we set the bar? Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automat Med 2007;51:13–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (DHEW Publication No. ADM 76–338). Washington, DC: U.G.P. Office, Editor; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther 2009;173:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;343:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dauphinee SW, Gauthier L, Gandek B, Magnan L, Pierre U. Readying a US measure of health status, the SF-36, for use in Canada. Clin Invest Med 1997;204:224–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain 2005;114(1–2):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 2015;286:489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 2016;2811:1379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cocks K, Torgerson DJ. Sample size calculations for pilot randomized trials: A confidence interval approach. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;662:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Eccleston C, Hearn L, Williams AC. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;10:CD011259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: Issues and research recommendations. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2006;124:365–83. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain 1995;623:363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sullivan MJ. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: User manual. 2009. Available at:http://sullivan-painresearch.mcgill.ca/pdf/pcs/PCSManual_English.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2015.

- 80. Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Otte im Kampe E, Kovats S, Hajat S. Impact of high ambient temperature on unintentional injuries in high-income countries: A narrative systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2016;62:e010399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kieffer WK, Michalik DV, Gallagher K et al. Temporal variation in major trauma admissions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016;982:128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Quebec Trauma Registry. Statistics for the Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal. Quebec, Canada: Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Avenell A et al. Randomised controlled feasibility trial of an evidence-informed behavioural intervention for obese adults with additional risk factors. PLoS One 2011;68:e23040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Birnie KA, McGrath PJ, Chambers CT. When does pain matter? Acknowledging the subjectivity of clinical significance. Pain 2012;15312:2311–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. US Health and Human Services, Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee. National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population Health-Level Strategy for Pain. Washington, DC: US Health and Human Services; 2016. Available at:https://iprcc.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHSNational_Pain_Strategy_508C.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2017.

- 87. Von Korff M, Scher AI, Helmick C et al. United States national pain strategy for population research: Concepts, definitions, and pilot data. J Pain 2016;1710:1068–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Center for Disease Control Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Daoust R, Paquet J, Moore L et al. Early factors associated with the development of chronic pain in trauma patients. Pain Res Manag 2018; 7203218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Linton SJ, Buer N, Samuelsson L, Harms-Ringdahl K. Pain-related fear, catastrophizing and pain in the recovery from a fracture. Scand J Pain 2010;11:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Veal FC, Bereznicki LRE, Thompson AJ, Peterson GM, Orlikowski C. Subacute pain as a predictor of long-term pain following orthopedic surgery. Medicine 2015;9436:e1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell CM, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain 2019;20(2):146–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Krishna R, Maithreyi R, Surapaneni KM. Research bias: A review for medical students. JCDR 2010;4:2320–4. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Puffer S, Torgerson DJ, Watson J. Cluster randomized controlled trials. J Eval Clin Pract 2005;115:479–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. George SZ, Childs JD, Teyhen DS et al. Brief psychosocial education, not core stabilization, reduced incidence of low back pain: Results from the Prevention of Low Back Pain in the Military (POLM) cluster randomized trial. BMC Med 2011;9:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Jahn P, Kuss O, Schmidt H et al. Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: A cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Pain 2014;1554:746–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Carmona-Teres V, Lumillo-Gutiérrez I, Jodar-Fernandez L et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a health coaching intervention to improve the lifestyle of patients with knee osteoarthritis: Cluster randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Werner EL, Storheim K, Løchting I, Wisløff T, Grotle M. Cognitive patient education for low back pain in primary care: A cluster randomized controlled trial and cost- effectiveness analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;416:455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kristoffersen ES, Straand J, Vetvik KG et al. Brief intervention for medication-overuse headache in primary care. The BIMOH study: A double-blind pragmatic cluster randomised parallel controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;865:505–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Serlin RC et al. The effectiveness of the Pain Resource Nurse Program to improve pain management in the hospital setting: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;75:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lindquist R, Wyman JF, Talley KM, Findorff MJ, Gross CR. Design of control-group conditions in clinical trials of behavioral interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;393:214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Miller FG, Colloca L, Kaptchuk TJ. The placebo effect: Illness and interpersonal healing. Perspect Biol Med 2009;524:518–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Mattocks KM, Horwitz RI. Placebos, active control groups, and the unpredictability paradox. Biol Psychiatry 2000;478:693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hrobjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;1:Cd003974 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Krogsboll LT, Hrobjartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Spontaneous improvement in randomised clinical trials: Meta-analysis of three-armed trials comparing no treatment, placebo and active intersention. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.