Abstract

Objective

The National Institutes of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)® includes an item bank for measuring misuse of prescription pain medication (PROMIS-Rx Misuse). The bank was developed and its validity evaluated in samples of community-dwelling adults and patients in addiction treatment programs. The goal of the current study was to investigate the validity of the item bank among patients with mixed-etiology chronic pain conditions.

Method

A consecutive sample of 288 patients who presented for initial medical evaluations at a tertiary pain clinic completed questionnaires using the open-source Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry. Participants were predominantly middle-aged (M [SD] = 51.6 [15.5] years), female (62.2%), and white/non-Hispanic (51.7%). Validity was evaluated by estimating the association between PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores and scores on other measures and testing the ability of scores to distinguish among risk factor subgroups expected to have different levels of prescription pain medicine misuse (known groups analyses).

Results

Overall, score associations with other measures were as expected and scores effectively distinguished among patients with and without relevant risk factors.

Conclusion

The study results supported the preliminary validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank scores for the assessment of prescription opioid misuse in patients visiting an outpatient pain clinic.

Keywords: PROMIS, Prescription Pain Medication, Misuse of Prescription Opioid, Item Response Theory, Assessment

Introduction

In the past decade, the use of chronic opioid therapy for noncancer pain has been increasingly debated in the field of pain medicine. This is partly due to the alarming rate of drug overdoses in the United States, which has tripled between 2000 and 2016 [1]. Today, more than 46 adults die daily from overdoses associated with prescription opioids [1]. Prescription opioids, such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, are involved in a significant proportion of opioid-related overdoses [1]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national data, 60% of prescription overdose deaths occur in patients with legitimate prescriptions from a single provider [2]. Therefore, physicians play a critical role in identifying patients who misuse prescription opioids and offering them appropriate health care services. Identifying patients misusing prescription opioids at an outpatient pain clinic, however, is challenging. Physicians’ judgments of aberrant opioid behavior have been found to be unreliable [3,4], highlighting the need for a valid and efficient screening instrument in these settings.

So far, several self-report instruments have been developed to assess current and future aberrant drug use behaviors in patients taking prescription opioids. Such measures are the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) [5], Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain–Revised (SOAPP-R) [6], Pain Medication Questionnaire (PMQ) [7], Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) [3], and Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire–Patient (PDUQ-p) [8]. Among these measures, the ORT, and SOAPP-R, were developed to assess the risks of developing prescription misuse behaviors [5,6]. The COMM, PMQ, and PDUQ-p were developed to identify patients with current prescription opioid misuse [3,7,8], and the items in these instruments are similar in that the items assess prescription misuse behaviors and risk factors associated with opioid misuse (e.g., emergency room [ER] visit in the past 30 days [3], existence of chronic pain in immediate family members [8]). Finally, a brief Opioid Compliance Checklist (OCC) with a binary response (yes/no) was developed to assess current and future prescription opioid misuse [9,10]. The OCC’s binary response items are acceptable for a brief screener but limit between-subject variability. Therefore, we still need a new self-report instrument to assess current prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain.

Addressing this need, Pilkonis et al. developed a measure of prescription pain medication abuse and misuse as part of National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS-Rx Misuse) [11]. Abuse refers to nonmedical use of opioids such as euphoria or altering state of consciousness, whereas misuse is a broad term and refers to opioid use contrary to the prescribed pattern of use [12]. Because the current study administered the PROMIS items to assess aberrant drug use behaviors, including abuse and misuse of prescription opioids, we called this measure the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank. The PROMIS has developed measures to assess multiple health domains in patients with a variety of chronic conditions, including pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function [13,14]. Calibration and initial psychometric evaluations of the 22-item PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank were done with community-dwelling adults and patients in an addiction treatment program [11]. The results supported the validity of item bank scores. PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were highly correlated with scores on the PMQ (r = 0.73) and marginally to moderately correlated with the use of other substances (i.e., r = 0.59 for nonmedical opioids, r = 0.45 for tobacco, r = 0.44 for alcohol, r = 0.33 for sedatives). The validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse was supported by the finding that scores were only weakly correlated with scores on measures of other health domains such as global health and pain (|rs| = 0.05∼0.18) [11]. Though these results are promising, additional study is needed to evaluate the validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores in other contexts and in other populations.

The goal of the current study was to evaluate the validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank scores in a sample of patients with chronic noncancer pain presenting for new patient evaluation at a pain management center.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at the Stanford University School of Medicine approved all aspects of the current study.

Procedures

We collected data as part of routine clinical care procedures at the Stanford Pain Management Center. All measures and demographic questions were administered via the Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR), an open-source registry for assessing patients’ general- and pain-related health status. Most of the measures administered in the CHOIR remain constant over time. New measures are occasionally added or deleted to meet research and clinical goals. The data for the current study were collected from 288 consecutively enrolled patients who presented for initial medical evaluations at an outpatient pain clinic between December 2014 and March 2015. The study data set was limited to responses of patients aged 18 years or older who endorsed taking opioid pain medication for any chronic pain conditions.

Measures

PROMIS Measures

In addition to the 22 items of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank, data included responses to PROMIS measures of pain interference, depression, anxiety, anger, physical function, pain interference, sleep-related impairment, and sleep interference. Substantial evidence for the validity of scores on PROMIS measures has accumulated [13,14]. Details about measure development and validation can be found at http://www.healthmeasures.net. All PROMIS measures were administered using computerized adaptive testing (CAT) except the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank. To analyze the PROMIS-Rx Misuse items, the current study used previously published item parameters from the graded response model [11]. Using data from our respondents, we calculated theta scores from expected a posteriori (EAP) estimates using the catR package [15] and transformed theta scores into T scores (M [SD] = 50 [10]).

Other Pain Measures

The 13 items of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [16,17] and Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF) [18,19] were analyzed, as some have found that ratings for pain catastrophizing and pain intensity are positively associated with opioid misuse or its risk [20,21]. The PCS items are rated on a five-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time); total scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more catastrophic thinking related to pain [16]. The PCS has been found to have high interitem consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.87). The recommended respective threshold scores for moderate and clinical levels of catastrophizing are 20 and 30, scores associated with the 50th and 75th percentiles of patients with chronic pain [17]. The four BPI-SF items measure patients’ current pain, as well as worst, average, and least pain, for the past week [18,19].

Substance Use, Risk, and Side Effects

The Opioid Risk Tool was developed to evaluate the risk of aberrant prescription use behaviors for patients seen at a private pain clinic [5]. The ORT was added later to the CHOIR to assess the risk of future opioid misuse, so only a portion of the study sample completed the ORT (53%, N = 145). ORT items assess personal and family history of substance abuse and other known risk factors such as childhood trauma and psychiatric conditions. The measure has been shown to identify individuals at high risk for aberrant prescription use behaviors (sensitivity = 0.99, specificity = 0.88) [5]. Recommended threshold scores on the ORT for low, moderate, and high risk of opioid addiction are 0–3, 4–7, and ≥8, respectively [5]. It should be noted that more recent findings have suggested that the ORT risk groups do not predict future opioid misuse [22].

CHOIR administration also included questions to evaluate opioid-related side effects such as constipation, loss of sexual interest, exquisite sensitivity to pain, slow thinking, nausea, drowsiness, weight gain, and weight loss. Current alcohol and smoking status, history of street drug use in the past 10 years, and lifetime history of drug treatment were also assessed (yes/no). Those who endorsed current smoking or drinking were asked to report the number of cigarettes per day and drinks per week, as well as whether they drink alcohol for pain relief.

Analyses

Scale Information

The current study used previously published item parameters from the graded response model for the 22 items in the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measure [11]. The effective range of measurement for the item bank is about –1 to +3 SD of theta scores [11], which corresponds to T scores of 40 to 80.

Reliability

The PROMIS-Rx Misuse item banks had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.87). No poorly functioning items were identified, as Cronbach α coefficients would have remained unchanged (0.85–0.87) if each item were deleted.

Validity

To evaluate the concurrent validity of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores, we examined its association with scores on the PCS, BPI-SF, and ORT. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for these estimates. The domains measured by the PCS and BPI-SF are related to but distinct from prescription opioid misuse. The ORT measures a construct that is much more proximal to that measured by the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measure. We therefore expected correlations between the PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores to be higher with ORT scores than with the related but more distal PCS and BPI-SF measures.

The validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores was also evaluated by conducting known groups analysis. We identified subgroups expected to score higher or lower in prescription opioid abuse and then tested the hypothesis that PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores concur with these expectations. Known groups comparisons were conducted based on the following groups: 1) low, medium, and high opioid risk based on ORT score thresholds [5]; 2) low, medium, and severe depression based on PROMIS-Depression T score thresholds (≤59, 60–65, and ≥66, respectively) [23]; 3) low, medium, and severe anxiety based on PROMIS-Anxiety T score thresholds ≤55, 56–68, and ≥69, respectively) [24]; 4) low, moderate, and clinical pain catastrophizing based on PCS cutoff scores of 0–19, 20–29, and ≥30 [17], respectively; 5) endorsement (yes/no) of opioid-related side effects, alcohol use, cigarette smoking, street drug use, and drug treatment history [25]; and 6) sex (male/female) [26–28]. Independent-samples t tests (for two groups) or analyses of variance (ANOVAs; three or more groups) were conducted to evaluate the omnibus hypothesis of statistically significant differences among groups (alpha = 0.05). Because the direction of effects was known, one-tailed tests were used. In cases of unequal variance, as indicated by a significant Leven’s test result, t test results with adjusted degrees of freedom were presented. Significant findings for ANOVAs were followed up with post hoc comparisons using Dunnett’s T3 post hoc test.

Results

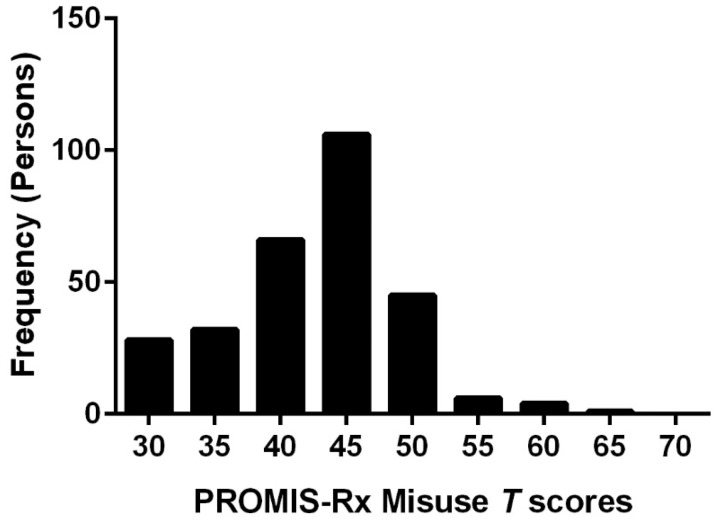

Figure 1 provides T score distribution of the sample. Our sample mean was 42.7 T with an SD of 6.2. The majority of scores (70%) were within the effective range of measurement such as 40 T to 80 T. Table 1 summarizes sample demographics. The sample was predominantly female (62.2%) and middle-aged (M [SD] = 51.6 [15.5] years, range = 20–92 years). Most participants reported their race/ethnicity as white/non-Hispanic (51.7%), followed by Hispanic/Latino (11.5%). Over half of the sample was married (53.1%) and had at least a high school diploma (54.9%).

Figure 1.

Histogram of sample T score distribution.

Table 1.

Demographics (N = 288)

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 51.6 | 15.5 | |

| Gender, No., % female | 179 | 62.2 | |

| Years in chronic pain | 6.0 | 9.1 | |

| Doctor’s office visits for the past 6 mo | 7.7 | 7.3 | |

| No. | % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | White/non-Hispanic | 149 | 51.7 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 | 11.5 | |

| Asian | 17 | 5.9 | |

| Black/African American | 6 | 2.1 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Others (multiracial, etc.) | 66 | 22.9 | |

| Refused/unknown | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Educations | Less than high school | 19 | 6.6 |

| High school diploma | 32 | 11.1 | |

| Some college | 78 | 27.1 | |

| Associate’s degree | 42 | 14.6 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 58 | 20.1 | |

| Master’s degree | 38 | 13.2 | |

| Professional school degree | 11 | 3.8 | |

| Doctoral degree | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 153 | 53.1 |

| Never married | 58 | 20.1 | |

| Divorced | 38 | 13.2 | |

| Living together | 19 | 6.6 | |

| Widowed | 10 | 3.5 | |

| Separated | 8 | 2.8 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Opioid-related side effects | Constipation | 130 | 45.1 |

| Drowsiness | 80 | 27.8 | |

| Slowed thinking | 76 | 26.4 | |

| Weight gain | 48 | 16.7 | |

| Loss of sexual interest | 44 | 15.3 | |

| Nausea | 42 | 14.6 | |

| Weight loss | 26 | 9.0 | |

| Exquisite sensitivity to pain | 19 | 6.6 | |

| Other | 20 | 6.9 | |

| Smoking status | Current smoker | 39 | 13.5 |

| Current heavy smoker (>1 pack/d) | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Alcohol | Current drinker | 88 | 30.6 |

| Current binge drinker | 5 | 1.7 | |

| Street drug | Used for the past 10 y | 32 | 11.1 |

| Drug treatment | 22 | 7.6 | |

Patients reported having had chronic pain conditions for an average of six years (SD = 9.1, range = 6 months–52 years). About a third reported no opioid-related side effects (31.3%, n = 90), whereas the majority reported at least one side effect (68.7%, n = 198). The most frequently endorsed side effects were constipation (45.1%), drowsiness (27.8%), and mental slowness (26.4%). Participants reported having had multiple doctor visits (M = 7.7, range = 0–42) during the past six months, and about 50% reported having at least one ER visit (median = 1, range 0–10) during this time period. Among patients who endorsed being a current smoker, about 23.1% (n = 9) reported smoking about a pack of cigarettes per day. Among current drinkers, a small percentage endorsed binge drinking (5.7%, n = 5) or drinking for pain relief (22.7%, n = 20). History of street drug use was endorsed by about 11.1% of patients (n = 32). Three patients (1.0%) used all three substances, and 17 (5.9%) used two in any combination of smoking, alcohol, and street drug. Single substance use was more common with alcohol (26.0%, n = 75), followed by cigarette smoking (9.0%, n = 26), and street drugs (5.5%, n = 16). About 7.6% reported a history of drug treatments.

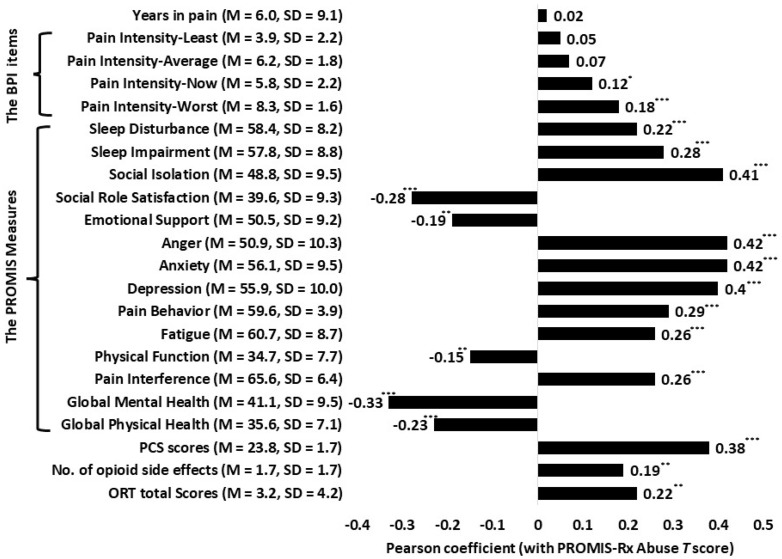

Concurrent Relationships

Figure 2 reports the Pearson correlation values for the bivariate relationships between PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores and scores on other measures (Figure 1). All associations were in the expected direction. They also were of expected magnitudes, with the exception of the correlation between PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores and scores on the ORT (r = 0.22). PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were negatively correlated with the PROMIS global physical (r = –0.23) and mental health T scores (r = –33), suggesting a negative impact of prescription opioid misuse and physical and emotional health. Magnitudes of other coefficients (|r|) ranged from 0.15 to 0.42, which are within the expected range. These associations suggest a relationship between opioid misuse and poorer health status. Lastly, higher ratings on the BPI worst pain and present pain items were associated with higher PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores, suggesting that worst pain ratings and pain ratings at present were positively associated with prescription opioid misuse. Ratings of average pain and least pain for the past week were unrelated to PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores.

Figure 2.

Pearson R correlations between Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–Rx Misuse T scores and scores on other measures. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Known Groups Validity of PROMIS-Rx Misuse T Scores

Table 2 summarizes means and standard deviations of PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores for known group results for Pain Catastrophizing, Anxiety, Depression, and Opioid Risk, all of which were classified into three subgroups. For each known group, an ANOVA was conducted to test the omnibus null hypothesis of no differences among groups. All significant mean differences were in the expected direction (i.e., higher levels of PROMIS-Rx Misuse with higher levels of pain catastrophizing, anxiety, depression, and opioid risk). For the three emotional distress measures (Pain Catastrophizing, Anxiety, and Depression), the null was rejected at P < 0.001. Results for Opioid Risk were also significant (P = 0.016).

Table 2.

PROMIS-Rx Misuse T score Comparison Between Known Groups

| Known Groups | No. | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Catastrophizing* | Low | 108 | 39.9a | 5.6 |

| Moderate | 80 | 43.2a | 6.2 | |

| High | 100 | 45.1b | 5.8 | |

| Anxiety* | Low | 181 | 41.2a | 5.7 |

| Moderate | 61 | 43.8b | 6.3 | |

| High | 46 | 46.9c | 6.1 | |

| Depression* | Low | 78 | 39.4a | 5.6 |

| Moderate | 106 | 42.8b | 5.9 | |

| High | 104 | 45.0c | 5.9 | |

| Opioid Risks* | Low | 94 | 41.5a | 6.0 |

| Moderate | 36 | 42.2a | 6.5 | |

| High | 15 | 46.5b | 6.1 | |

| Current Smokers* | “No” responders | 247 | 42.3 | 6.2 |

| “Yes” responders | 39 | 44.5 | 6.2 | |

| Current Alcohol Use | “No” responders | 199 | 42.7 | 6.3 |

| “Yes” responders | 88 | 42.7 | 6.3 | |

| Alcohol Use for Pain* | “No” responders | 67 | 42.1 | 6.2 |

| “Yes” responders | 20 | 45.1 | 5.6 | |

| History of Drug Treatment* | “No” responders | 265 | 42.3 | 6.2 |

| “Yes” responders | 22 | 46.6 | 5.7 | |

| History of Any Street Drug Use* | “No” responders | 255 | 42.3 | 6.1 |

| “Yes” responders | 32 | 45.6 | 6.4 | |

| Any Opioid Side Effect* | “No” responders | 90 | 41.5 | 6.3 |

| “Yes” responders | 198 | 43.2 | 6.2 | |

Means sharing the same superscript are not significantly different from each other.

PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Indicates a significant omnibus F test or an independent T test result. Respective low, moderate, and high groups were based on the total PCS scores of ≤10, 11–29, and ≥30 for pain catastrophizing, the PROMIS-Anxiety T scores of ≤55, 56–68, and ≥69 for anxiety, and the PROMIS-Depression T scores of ≤59, 60–65, and ≥66 for depression.

In post hoc analyses (Dunnett’s T3), PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores were found to discriminate well in pairwise comparisons at the subgroup level. Among pain catastrophizing subgroups, significantly different PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were found between the groups with the high and low pain catastrophizing scores (d = 5.2, P < 0.001) and between the groups with the high and moderate pain catastrophizing scores (d = 3.4, P < 0.001), though not between the low and moderate pain catastrophizing groups (P = 0.069). All pairwise anxiety and depression subgroup comparisons were statistically significant (range of P values = <0.001–0.015). Mean score differences between subgroups ranged from 2.3 to 5.7. Statistically significant differences were also found between high and low levels of opioid risk (d = 5.0, P = 0.012) and between high and medium risk groups (d = 4.3, P = 0.047), though not between low and medium risk groups (P = 0.46).

The bottom half of Table 2 reports known groups results for measures classified into two groups. Independent t tests were conducted to compare PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores between groups. All significant mean differences were in the expected direction (higher PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores for those reporting current smoking, alcohol use for pain, history of drug treatment, history of street drugs, and opioid side effects). Significant differences were found in comparing T scores of respondents who did and did not endorse being a current smoker (d = 2.1, P = 0.027), using alcohol for pain (d = 2.9, P = 0.026), having a history of drug treatment (d = 4.2, P = 0.001), and having a history of street drug use (d = 3.3, P = 0.002). There were no significant differences between those who endorsed and did not endorse using alcohol (P = 0.500).

A significant group effect was found between those who reported experiencing opioid side effects and those who did not (d = 1.7, P = 0.014). In follow-up analyses, we compared PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores between groups based on endorsement of specific side effects. Significantly higher PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were observed for participants endorsing weight loss (d = 3.3, P < 0.001), exquisite sensitivity to pain (d = 3.0, P = 0.003), reduced sexual interest (d = 2.9, P < 0.001), mental slowness (d = 1.9, P = 0.007), and drowsiness (d = 1.8, P = 0.016). No statistical differences in PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores were found between groups endorsing and not endorsing constipation (P = 0.052), nausea (P = 0.059), or weight gain (P = 0.233).

Finally, an independent t test compared PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores between male and female patients. Males had significantly higher PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores compared with females (d = 2.6, P < 0.001).

Discussion

The current study examined the validity of scores derived from the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank in patients with chronic noncancer pain presenting for new patient evaluation at a tertiary pain management center.

Expected relationships between PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores and scores on other measures were mostly upheld. The associations between negative mood and prescription opioid misuse have been documented and found elevated risk among patients with greater depression [28,29], anxiety [29], anger [3,30], and pain catastrophizing [20]. PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were significantly different among patients endorsing low, medium, and high levels of negative mood such as depression, anxiety, and pain catastrophizing, supporting the validity of the PROMIS measure and confirming associations between prescription misuse and negative mood. Positive correlations were obtained between PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores and scores on measures assessing health problems known to be less directly related to substance use, but as expected, these were lower than correlations with scores on measures of negative mood.

An unexpected result was the relatively low correlations between PROMIS-Rx Misuse and ORT scores (r = 0.22). The ORT was initially developed and validated for use in predicting future aberrant opioid use among patients visiting at a pain clinic [5]. The known risk factors may be less sensitive in picking up current misuse of prescription opioids. The ORT may target somewhat different aspects of opioid-related problems compared with the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measure. The latter evaluates current misuse of prescription opioid medication, whereas the former evaluates known risk factors including family history, trauma, and psychiatric diagnoses. However, PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores did discriminate among levels of ORT, including differences among some pairwise comparisons of ORT levels (i.e., significantly higher ORT score groups). Notably, we analyzed the ORT despite recent concerns about its validity [22]. Hence these findings should be interpreted with caution, and validated instruments like the COMM or PMQ should be considered in future studies.

Finally, we found that PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores were significantly higher in men than women, consistent with research that observed similar gender differences. A national survey found that men endorse nonmedical use of opioids more than women, and behaviorally, men are more likely to obtain opioids from a friend, relative, or stranger than women [27].

The current study is the first study to examine the validity of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank to be use in patients taking prescription opioids for chronic pain visiting a tertiary pain management clinic. Specifically, we examined concurrent validity and known group validity. Validity is an ongoing process to examine whether the use of a specific measure is valid for a certain purpose [31]. The typical types are content and criterion-related validity. Content validity refers to the degree to which the content is congruent with a testing purpose, and criterion-related validity refers to the degree to which the measure predicts criteria such as outcomes [31]. In the original study from Pilkonis’s group, the content validity of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse was established by formulating valid items with inputs from patients, experts, cognitive interviewing, and literature review [11]. The original study examined fit indices to ensure that the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measures a single construct and provided preliminary evidence for convergent validity as the PROMIS-Rx Misuse severity index (theta) was highly correlated with risk for opioid medication misuse (r = 0.73) and moderately correlated with nonmedical use of opioids (r = 0.59) [11]. The current study provided preliminary evidence for concurrent validity, as the PROMIS-Rx Misuse T scores were positively associated with opioid risks, opioid side effects, and distress in physical, psychological, and social health domains. As the current study provided favorable preliminary results, we plan to continue validating the PROMIS-Rx item bank and optimizing its clinical utility.

Different from previous validation studies that were conducted in the context of research, the current study administered the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank to patients on opioid therapy who presented for initial medical evaluations. Our CHOIR data registry enables physicians to monitor patients’ multiple health problems in real time and to provide individualized medical treatment by integrating each patient’s self-report into their medical decision-making. Our patients agreed to complete the PROMIS measures for their medical visits and research. Based on our results, patients who came in for their first medical appointment might provide useful information that can be used to assess their prescription opioid misuse behaviors. Therefore, the current study established the preliminary ecological validity of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank to be used in patients visiting a pain clinic at their initial medical appointment.

Our study has several limitations. First, data are self-reported and subject to recall bias. Second, data are cross-sectional, precluding causal inferences. This may be particularly relevant for the emotional distress measures, which can be both a risk factor for opioid abuse and a result of opioid abuse. Additionally, questions about opioid abuse risk factors and substance use are sensitive and subject to social desirability bias, which could result in underreporting. Additionally, the current study did not include objective measures such as urine drug test, prescription drug monitoring, or a clinical interview by a clinical psychologist. It would be informative to include such measures in future evaluations of the validity of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank. We also did not include any other self-report measures developed to screen for current aberrant prescription pain medication use, though such measures have recently been developed [3,8,9,32–34]. As noted earlier, the ORT was designed to evaluate future risk rather than current abuse of prescription medications, in addition to recent evidence questioning its validity in predicting future misuse [22]. Future evaluations should include alternative self-report scales that, like the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measure, target current aberrant use. We also recommend future research with the goal of establishing clinical cutoffs for PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores. The existence of such thresholds would greatly increase the clinical utility of the PROMIS-Rx Misuse measure. In addition, and perhaps in tandem with such a study, in future work, it would be useful to evaluate the ability of PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores to discriminate between patients exhibiting opioid misuse behaviors and opioid use disorder. Findings from such a study would have important clinical implications.

Monitoring for aberrant opioid use based on self-report has limitations, but it also has distinct advantages over more labor-intensive methods such as interviews and urine drug testing. Our results showed the effectiveness of PROMIS-Rx Misuse scores in discriminating levels of opioid misuse among pain clinic outpatients. Thus, the PROMIS-Rx Misuse item bank is appropriate for use beyond the population for which it was originally developed, namely, community adults and patients in addiction treatment. In conclusion, the PROMIS-Rx Misuse is promising, and additional research is warranted to further investigate its reliability, validity, and clinical utility.

Funding sources: Dr. Jennifer Hah (K23DA035302), Dr. Maisa Ziadni (T32DA035165), and Dr. Sean Mackey (K24DA029262, T32 DA035165) received funding from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse for this project. Dr. Sean Mackey also received support from the Redlich Pain Research Endowment for this project. Dr. Dokyoung You (R01AT008561) received funding from NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1. Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM.. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. NCHS Data Brief, No. 294. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC grand rounds: Prescription drug overdoses - a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;611:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain 2007;130(1–2):144–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Setnik B, Roland CL, Pixton GC, Sommerville KW.. Prescription opioid abuse and misuse: Gap between primary-care investigator assessment and actual extent of these behaviors among patients with chronic pain. Postgrad Med 2017;1291:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Webster LR, Webster RM.. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: Preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med 2005;66:432–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, Budman SH, Jamison RN.. Validation of the Revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain 2008;94:360–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmes CP, Gatchel RJ, Adams LL, et al. An opioid screening instrument: Long-term evaluation of the utility of the pain medication questionnaire. Pain Pract 2006;62:74–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Compton PA, Wu SM, Schieffer B, Pham Q, Naliboff BD.. Introduction of a self-report version of the prescription drug use questionnaire and relationship to medication agreement noncompliance. J Pain Symptom Manag 2008;364:383–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jamison RN, Martel MO, Edwards RR, et al. Validation of a brief opioid compliance checklist for patients with chronic pain. J Pain 2014;1511:1092–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jamison RN, Martel MO, Huang C-C, Jurcik D, Edwards RR.. Efficacy of the opioid compliance checklist to monitor chronic pain patients receiving opioid therapy in primary care. J Pain 2016;174:414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, et al. An item bank for abuse of prescription pain medication from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Pain Med 2017;188:1516–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: A systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 2015;1564:569–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: Further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res 2010;199:1311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cook KF, Jensen SE, Schalet BD, et al. PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;73:89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magis D, Barrada JR Computerized Adaptive Testing with R: Recent Updates of the Package catR. J of Stat Softw 2017;76(1):1–19. Retrieved from https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v076c01.

- 16. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J.. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;74:524–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan MJ. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: User Manual. Montreal, Quebec: McGill University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cleeland C. Measurement of pain by subjective report. Adv Pain Res Ther 1989;12:391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF.. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004;52:133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martel M, Wasan A, Jamison R, Edwards RR.. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132(1–2):335–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arteta J, Cobos B, Hu Y, Jordan K, Howard K.. Evaluation of how depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between pain catastrophizing and prescription opioid misuse in a chronic pain population. Pain Med 2016;172:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clark MR, Hurley RW, Adams MCB.. Re-assessing the validity of the Opioid Risk Tool in a tertiary academic pain management center population. Pain Med 2018;19(7):1382–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi S, Podrabsky T, McKinney N, Schalet B, Cook K, Cella D.. PROsetta Stone Analysis Report: A Rosetta Stone for Patient Reported Outcomes. Vol. 1.Chicago, IL: Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schalet BD, Cook KF, Choi SW, Cella D.. Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: Linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS Anxiety. J Anxiety Disord 2014;281:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ives TJ, Chelminski PR, Hammett-Stabler CA, et al. Predictors of opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: A prospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;61:46. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jamison RN, Butler SF, Budman SH, Edwards RR, Wasan AD.. Gender differences in risk factors for aberrant prescription opioid use. J Pain 2010;114:312–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Back SE, Payne RL, Simpson AN, Brady KT.. Gender and prescription opioids: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behav 2010;3511:1001–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grattan A, Sullivan MD, Saunders KW, Campbell CI, Von Korff MR.. Depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuse. Ann Fam Med 2012;104:304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Becker WC, Sullivan LE, Tetrault JM, Desai RA, Fiellin DA.. Non-medical use, abuse and dependence on prescription opioids among U.S. adults: Psychiatric, medical and substance use correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008;94(1–3):38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El-Hadidy MA, Helaly AM.. Medical and psychiatric effects of long-term dependence on high dose of tramadol. Subst Use Misuse 2015;505:582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zumbo BD, Chan EK.. Reflections on validation practices in the social, behavioral, and health sciences In: Zumbo BD, Chan EK, eds. Validity and Validation in Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2014:321–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, Jamison RN.. Cross validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain 2010;269:770–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: Diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain 2011;1522:397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS.. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: A review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Phys 2012;15(suppl 3): ES67–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]