Key Points

Question

Are long-term consequences associated with recurrent febrile seizures?

Findings

In this cohort study of 2 103 232 children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years born in Denmark, recurrent febrile seizures were assessed. The cumulative risk of recurrent febrile seizures in 75 593 children with a first febrile seizure was 22.7%. The risk of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders increased with the number of hospital admissions with febrile seizures.

Meaning

Recurrent febrile seizures appear to be associated with a risk of developing epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, but excessive mortality was observed only in those who later developed epilepsy.

Abstract

Importance

Febrile seizures occur in 2% to 5% of children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years. Many affected children experience recurrent febrile seizures. However, little is known about the association between recurrent febrile seizures and subsequent prognosis.

Objective

To estimate the risk of recurrent febrile seizures and whether there is an association over long-term follow-up between recurrent febrile seizures and epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death in a large, nationwide, population-based cohort in Denmark.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study evaluated data from all singleton children born in Denmark between January 1, 1977, and December 31, 2011, who were identified through the Danish Civil Registration System. Children born in Denmark who were alive and residing in Denmark at age 3 months were included (N = 2 103 232). The study was conducted from September 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019.

Exposures

Hospital contacts with children who developed febrile seizures between age 3 months and 5 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Children diagnosed with epilepsy were identified in the Danish National Patient Register and children diagnosed with psychiatric disorders were identified in the Psychiatric Central Research Register. Competing risk regression and Cox proportional hazards regression were used to estimate the cumulative and relative risk of febrile seizures, recurrent febrile seizures, epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death.

Results

Of the 2 103 232 children (1 024 049 [48.7%] girls) in the study population, a total of 75 593 children (3.6%) were diagnosed with a first febrile seizure between 1977 and 2016. Febrile seizures were more common in boys (3.9%; 95% CI, 3.9%-4.0%) than in girls (3.3%; 95% CI, 3.2%-3.3%), corresponding to a 21% relative risk difference (hazard ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.19-1.22). However, the risks of recurrent febrile seizures, epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death were similar in boys and girls. The risk of (recurrent) febrile seizures increased with the number of febrile seizures: 3.6% at birth, 22.7% (95% CI, 22.4%-23.0%) after the first febrile seizure, 35.6% (95% CI, (34.9%-36.3%) after the second febrile seizure, and 43.5% (95% CI, (42.3%-44.7%) after the third febrile seizure. The risk of epilepsy increased progressively with the number of hospital admissions with febrile seizures. The 30-year cumulative risk of epilepsy was 2.2% (95% CI, (2.1%-2.2%) at birth compared with 15.8% (95% CI, 14.6%-16.9%) after the third febrile seizure, while the corresponding estimates for risk of psychiatric disorders were 17.2% (95% CI, 17.2%-17.3%) at birth and 29.1% (95% CI, 27.2%-31.0%) after the third febrile seizure. Mortality was increased among children with recurrent febrile seizures (1.0%; 95% CI, 0.9%-1.0% at birth vs 1.9%; 95% CI, 1.4%-2.7% after the third febrile seizure), although this risk was associated primarily with children who later developed epilepsy.

Conclusions and Relevance

A history of recurrent febrile seizures appears to be associated with a risk of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, but increased mortality was found only in individuals who later developed epilepsy.

This cohort study examines the long-term neurologic and psychiatric outcomes in individuals who experienced febrile seizures as children.

Introduction

Febrile seizures are a common disorder affecting 2% to 5%1,2,3 of children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years.4 The condition is generally considered benign; however, children with febrile seizures are likely to experience recurrent febrile seizures5 and are at increased risk of epilepsy and some psychiatric disorders.6,7,8,9,10

Risk factors for recurrent febrile seizures include young age at onset of the first febrile seizure, family history of febrile seizures, relatively low-grade fever at the time of seizure onset, and short duration of fever before the seizure.11,12 However, it is unclear how recurrence of febrile seizures affects the child’s neurologic and psychiatric development and mortality. Children who are prone to experience recurrent febrile seizures may, however, be more likely to experience febrile seizures of longer duration and severity that may be associated with greater risks of neuronal damage,13 resulting in neurologic and psychiatric sequelae. Studies examining the prognostic value of recurrent febrile seizures have often been limited by relatively small sample sizes and short follow-up, which precludes assessment of rare and longer-term outcomes.14,15,16 The aim of the present study was therefore to estimate the risk of recurrent febrile seizures and whether there is an association over long-term follow-up between recurrent febrile seizures and epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death in a large, nationwide, population-based cohort in Denmark.

Methods

Study Population

We used data from the Danish Civil Registration System17 to identify all singleton children (ie, excluding multiple births) born in Denmark between January 1, 1977, and December 31, 2011, who were alive and living in Denmark at age 3 months (N = 2 103 232 children). Each person living in Denmark is assigned a unique personal identification number, which was used to ensure accurate linkage of individual information between national registries. The study was conducted from September 1, 2017, to June 1, 2019. The project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Informed consent was not required according to Danish law governing registry-based research studies with no participant contact. Data are deidentified.

Information on Febrile Seizures

Information on febrile seizures was obtained from the Danish National Hospital Register,18 which contains information on all discharges from hospitals since 1977; information on outpatients has been included in the register since 1995. Diagnostic information is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 8th revision (ICD-8) from 1977 to 1993, and the 10th revision (ICD-10) from 1994 to 2016. According to the ICD classification system, a febrile seizure is defined as a seizure associated with high body temperature but without any serious underlying health issue.19 Thus, data from children were classified as febrile seizure cases if the children had been hospitalized or received outpatient care with a diagnosis of febrile seizures (ICD-8: 780.21; ICD-10: R56.0) between the ages of 3 months and 5 years and had no prior diagnosis of epilepsy (ICD-8: 345 excluding 345.29; ICD-10 G40.0), cerebral palsy (ICD-8: 343.99, 344.99; ICD-10: G80), intracranial tumors (ICD-8: 191, 225; ICD-10: C70-C71, D32-D33), severe head trauma (ICD-8: 851, 854; ICD-10: S06.1-S06.9), or intracranial infections (ICD-8: 320, 323; ICD-10: G00-G09) prior to the onset of the febrile seizure.4

We followed up all children until the end of 2016, ensuring at least 5 years of follow-up to allow all potential cases of febrile seizures to emerge. We defined the onset time of febrile seizures as the first day of the first contact with the hospital with a diagnosis of febrile seizures. Within the overall study population, we defined 3 subpopulations of children with 1 or more, 2 or more, and 3 or more febrile seizures, nested within each other (eFigure in the Supplement). We considered children to have recurrent febrile seizures when they had more than one hospital contact with febrile seizure that were separated by at least 7 days.

Information on Epilepsy, Psychiatric Disorders, and Death

Epilepsy was defined as any diagnosis of epilepsy as registered in the Danish National Patient Register. Psychiatric disorders were defined as any diagnosis in the ranges of ICD-8 290-315 and ICD-10 F00-F99, as registered in the Psychiatric Central Research Register,20 which contains information on all individuals with psychiatric disorders treated in secondary care since 1970 (outpatient and emergency department contact included since 1995). The Civil Registration System was used to identify children who died or had emigrated from Denmark.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the cumulative incidence rates of febrile seizures, epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death for the population (total, boys, girls) using competing risk regression,21 with a nonparametric approach based on the subdistribution hazards.22 In the analyses, children were followed up from age 3 months until the day of the diagnosis of interest, death, emigration, or end of follow-up on December 31, 2016, whichever came first, and we used age of the children as the underlying timescale. We used the same method to estimate the cumulative incidence rates of recurrent febrile seizures, epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and death for children following their first, second, and third febrile seizure. In the analyses, children were followed up from the date of their latest febrile seizure and time since last seizure was the underlying time scale. We further estimated the cumulative incidence of recurrent febrile seizures in children following their first, second, and third febrile seizure according to age at the time of their most recent seizure (age <2 years, ≥2 years). In a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the study population to those born after 1995 to assess outpatient contacts in the registers after this point.

We examined the association between the number of febrile seizures and risk of epilepsy at different ages of epilepsy onset by considering the interaction between the number of febrile seizures and follow-up time, in which we applied a Cox proportional hazards regression model. The number of febrile seizures and calendar time were treated as time-varying covariates, and the model was stratified by sex to allow for different baseline hazards in boys and girls. We also estimated the hazard ratios (HRs) of psychiatric disorders and death in 2 Cox proportional hazards regression models with and without adjustment for epilepsy, respectively. In these models, the number of febrile seizures, epilepsy, and calendar time were treated as time-varying covariates, and the models were stratified by sex.21 The proportionality assumption was assessed graphically using log-log plots and was satisfied for all main exposures.

All analyses were performed using Stata, version 15 statistical software (StataCorp LP). Findings were considered significant at α = .05; testing was 2-tailed and unpaired.

Results

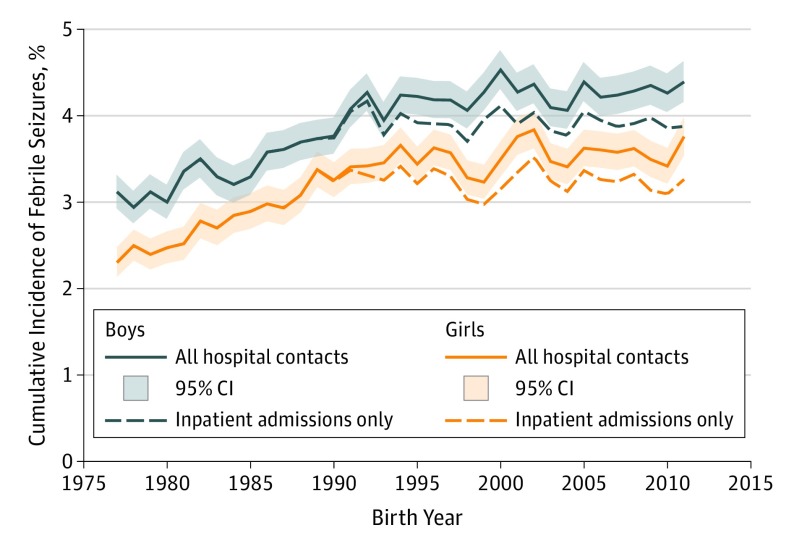

In the cohort of 2 103 232 children (1 024 049 [48.7%] girls), we identified 75 593 children (3.6%) with a diagnosis of febrile seizures between age 3 months and 5 years. Febrile seizures were more common in boys (cumulative incidence at age 5 years: 3.9%; 95% CI, 3.9%-4.0%) than in girls (cumulative incidence at age 5 years: 3.3%; 95% CI, 3.2%-3.3%), corresponding to a 21% relative risk difference (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.19-1.22). The age distribution of cases was almost identical between the sexes (Figure 1). The age-specific risk of febrile seizures peaked at age 16 months (median, 16.7 months; interquartile range, 12.5-24.0), and 68 737 children (90.9%) had their first febrile seizure before age 3 years. The cumulative incidence of febrile seizures increased during the study period, but when we restricted the cases to inpatient admissions, the cumulative incidence was stable from 1990 onward (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Age- and Sex-Specific Incidence of First Admission With Febrile Seizures .

Data shown for 2 103 232 children born in Denmark between 1977 and 2011.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Febrile Seizures by Birth Year .

Data shown for 2 103 232 children born in Denmark between 1977 and 2011.

Risk of Recurrent Febrile Seizures

The 75 593 children who experienced at least 1 febrile seizure had a high risk of recurrent febrile seizures; that is, the cumulative risk of recurrent febrile seizures was 22.7% (95% CI, 22.4%-23.0%) following the first febrile seizure and increased further following additional febrile seizures: 35.6% (95% CI, 34.9%-36.3%) after the second febrile seizure and 43.5% (95% CI, 42.3%-44.7%) after the third febrile seizure (Table 1). The recurrence risk was largely similar for boys and girls. The risk of recurrent febrile seizures was higher when prior febrile seizures occurred before age 2 years (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Thus, although the recurrence risk was 26.4% (95% CI, 26.0%-26.7%) in children who had their first febrile seizure before age 2 years, it was only 11.8% (95% CI, 11.3%-12.3%) in children with febrile seizure onset after the age of 2 years. In children with 3 admissions with febrile seizures before age 2 years, the recurrence risk was 61.3% (95% CI, 59.3%-63.1%).

Table 1. Cumulative Risk of Febrile Seizures, Epilepsy, Psychiatric Disorders, and Death in Children Born in Denmark Between 1977 and 2011.

| Exposurea | Total No. | Febrile Seizures | Epilepsy | Psychiatric Disorders | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | 5-y Cumulative Risk, % (95% CI)b | No. (%) | 30-y Cumulative Risk, % (95% CI)b | No. (%) | 30-y Cumulative Risk, % (95% CI)b | No. (%) | 30-y Cumulative Risk, % (95% CI) | |||

| All Children | ||||||||||

| All | 2 103 232 | 75 593 (3.6) | 3.6 (3.6-3.6) | 34 935 (1.7) | 2.2 (2.1-2.2) | 231 435 (11.0) | 17.2 (17.2-17.3) | 14 161 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | |

| After first febrile seizure | 75 593 | 17 153 (22.7) | 22.7 (22.4-23.0) | 3873 (5.1) | 6.4 (6.2-6.6) | 9542 (12.6) | 21.4 (21.0-21.9) | 476 (0.6) | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) | |

| After second febrile seizure | 17 153 | 6097 (35.5) | 35.6 (34.9-36.3) | 1507 (8.8) | 10.8 (10.2-11.3) | 2384 (13.9) | 25.0 (24.0-26.1) | 123 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.2-1.8) | |

| After third febrile seizure | 6097 | 2647 (43.4) | 43.5 (42.3-44.7) | 777 (12.7) | 15.8 (14.6-16.9) | 960 (15.7) | 29.1 (27.2-31.0) | 52 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.4-2.7) | |

| Girls | ||||||||||

| All | 1 024 049 | 33 343 (3.3) | 3.3 (3.2-3.3) | 16 787 (1.6) | 2.2 (2.1-2.2) | 117 121 (11.4) | 18.8 (18.7-18.9) | 5039 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.6-0.7) | |

| After first febrile seizure | 33 343 | 7308 (21.9) | 22.0 (21.5-22.4) | 1730 (5.2) | 6.5 (6.2-6.9) | 4273 (12.8) | 23.5 (22.8-24.2) | 152 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | |

| After second febrile seizure | 7308 | 2520 (34.5) | 34.6 (33.5-35.7) | 667 (9.1) | 11.2 (10.3-12.1) | 1006 13.8) | 27.2 (25.5-29.0) | 36 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | |

| After third febrile seizure | 2520 | 1104 (43.8) | 43.9 (42.0-45.8) | 336 (13.3) | 16.2 (14.5-18.0) | 376 (14.9) | 30.5 (27.4-33.6) | 15 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.8-2.7) | |

| Boys | ||||||||||

| All | 1 079 183 | 42 250 (3.9) | 3.9 (3.9-4.0) | 18 148 (1.7) | 2.2 (2.1-2.2) | 114 314 (10.6) | 15.8 (15.7-15.9) | 9122 (0.8) | 1.3 (1.2-1.3) | |

| After first febrile seizure | 42 250 | 9845 (23.3) | 23.4 (23.0-23.8) | 2143 (5.1) | 6.2 (6.0-6.5) | 5269 (12.5) | 19.9 (19.3-20.4) | 324 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.2-.16) | |

| After second febrile seizure | 9845 | 3577 (36.3) | 36.4 (35.5-37.4) | 840 (8.5) | 10.5 (9.7-11.2) | 1378 (14.0) | 23.4 (22.1-24.7) | 87 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | |

| After third febrile seizure | 3577 | 1542 (43.1) | 43.2 (41.6-44.8) | 441 (12.3) | 15.4 (14.0-17.0) | 584 (16.3) | 28.1 (25.7-30.5) | 37 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.5-3.3) | |

These groups are not mutually exclusive but represent nested groups of children.

Cumulative incidences were estimated using competing risks regression, with deaths treated as competing events.

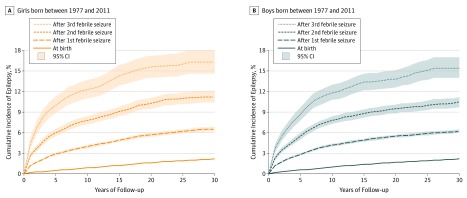

Risk of Long-term Outcomes

The risk of epilepsy also increased with the number of hospital admissions with febrile seizures. Hence, the 30-year cumulative incidence was 2.2% (95% CI, 2.1%-2.2%) at birth, 6.4% (95% CI, 6.2%-6.6%) after the first febrile seizure, 10.8% (95% CI, 10.2%-11.3%) after the second febrile seizure, and 15.8% (95% CI, 14.6%-16.9%) after the third febrile seizure (Table 1). The risk of being diagnosed with epilepsy after a febrile seizure was largely similar in boys and girls. For example, after the third febrile seizure, the risk of epilepsy was 16.3% (95% CI, 14.6%-18.0%) in girls and 15.4% (95% CI, 14.0%-17.0%) in boys (Figure 3). When we considered the risk of epilepsy at different ages, we found that the risk of epilepsy was especially elevated at young ages, but persisted even after several decades (eg, individuals aged 25-29 years with ≥3 seizures, HR, 4.57; 2.45-8.51) (Table 2). For all ages (except ≥30 years), the risk of being diagnosed with epilepsy increased with the number of febrile seizures.

Figure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Epilepsy.

Data shown for children born in Denmark between 1977 and 2011 and in children following their first, second, and third febrile seizure.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Analyses Showing Epilepsy Onset Depending on the Number of Febrile Seizuresa.

| Febrile Sezures, No. | Risk of Being Diagnosed With Epilepsy by Age, HR (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 y | 5-9 y | 10-14 y | 15-19 y | 20-24 y | 25-29 y | ≥30 y | ||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| 1 | 7.11 (6.63-7.61) | 3.09 (2.85-3.36) | 2.29 (2.05-2.55) | 2.02 (1.78-2.30) | 1.84 (1.53-2.21) | 1.62 (1.25-2.11) | 1.59 (1.13-2.24) | |

| 2 | 15.00 (13.37-16.78) | 5.75 (5.01-6.60) | 3.68 (3.02-4.49) | 2.83 (2.19-3.65) | 2.70 (1.88-3.86) | 1.00 (0.45-2.22) | 2.54 (1.32-4.90) | |

| ≥3 | 42.06 (37.93-46.64) | 13.43 (11.81-15.26) | 5.18 (4.07-6.61) | 5.45 (4.15-7.17) | 2.90 (1.68-5.00) | 4.57 (2.45-8.51) | 1.54 (0.38-6.16) | |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusted for sex and calendar period.

Febrile seizures in childhood were also associated with a higher risk of psychiatric disorders in later life (Table 1). In the overall population, the 30-year risk of admission with a psychiatric disorder was 17.2% (95% CI, 17.2%-17.3%). In comparison, in children with at least 1 febrile seizure, the corresponding risk after the first febrile seizure was 21.4% (95% CI, 21.0%-21.9%), increasing to 25.0% (95% CI, 24.0%-26.1%) in the subgroup of children with at least 2 or more admissions with febrile seizures and to 29.1% (95% CI, 27.2%-31.0%) in the subgroup of children with 3 or more admissions for febrile seizures. The relative risk of psychiatric disorders was elevated even after adjusting for epilepsy. For example, the risk of psychiatric disorders was greater in children with 3 or more admissions with febrile seizures compared with children with none (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.35-1.53) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Mortality also increased with the number of hospital admissions associated with febrile seizures. At birth, the 30-year cumulative risk of dying was 1.0% (95% CI, 0.9%-1.0%). After the first febrile seizure, the 30-year risk of dying was 1.2% (95% CI, 1.0%-1.3%); this risk increased further after the second (1.4%; 95% CI, 1.2%-1.8%) and third (1.9%; 95% CI, 1.4%-2.7%) febrile seizures. However, this excess risk appeared to be explained by concomitant epilepsy, as the relative risk estimates were attenuated when we adjusted for epilepsy. For example, for children with 3 or more febrile seizures, the HR decreased from 2.21 (95% CI, 1.69-2.91) to 0.91 (95% CI, 0.69-1.20) when adjusted for epilepsy) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

When we restricted the study population to children born after 1995 (ie, when outpatient contacts were included), we found that the risk of recurrent febrile seizures was slightly higher in these children (3.9; 95% CI, 3.9-4.0) compared with the overall cohort of children born between January 1, 1977, and December 31, 2011 (3.6; 95% CI, 3.6-3.6) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Furthermore, the cumulative risk of epilepsy and death following recurrent febrile seizures was somewhat lower than in the overall cohort, while the cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders was higher (20-year cumulative incidence, 14.7; 95% CI, 14.6-14.8 vs 9.4; 95% CI, 9.4-9.5) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study of more than 2 million children, we found that a history of febrile seizures appeared to be associated with an increased risk of epilepsy, especially among children with recurrent febrile seizures in early childhood. Psychiatric disorders and mortality at 30 years of follow-up also increased with the number of hospital admissions with febrile seizures, but the association with mortality disappeared when we adjusted for children who developed epilepsy after having been diagnosed with febrile seizures.

Recurrence of febrile seizures is common in children who have had their first febrile seizure.5 We found that the risk of recurrence was 22.7% following the first febrile seizure and even higher following additional febrile seizures. These recurrence risks are somewhat lower than what has previously been reported,12 although the estimates vary among the populations studied.23 Our estimates of the recurrence risks are likely conservative because not all children will be admitted to a hospital after the first episode. In line with previous studies,5 we found that age at onset of febrile seizures was associated with recurrence risk.

Although most children with febrile seizures reach adulthood without sequelae following the seizures, febrile seizures have consistently been associated with an increased risk of epilepsy.7 We observed an association between recurrent febrile seizures and the risk of epilepsy, and the risk was particularly high for children who had more than 2 febrile seizures. Our findings are consistent with the results from a UK-based study in which the risk of epilepsy increased by a factor of 2.48 (95% CI, 1.68-3.65) with the number of febrile seizures up to a limit of 4.24 In a recent cohort study from Taiwan,15 the 9-year cumulative incidence of epilepsy was 3.3% in children with 1 febrile seizure and 9.2% in children with 2 or more febrile seizures vs 0.5% in the comparison cohort without febrile seizures. These estimates are in line with the 9-year estimates from our study (Figure 2). We observed that the risk of epilepsy continued to increase, even after the first 9 years following febrile seizures, although the relative increase became less pronounced over time. One previous study showed that the risk of epilepsy following febrile seizures was particularly high in children with preexisting neurodevelopmental comorbidities.15 Another study suggested that complex febrile seizures are more strongly associated with the risk of subsequent epilepsy.25 These findings suggest that the risk of epilepsy following febrile seizures may be associated mainly with a subset of children with febrile seizures who may be genetically predisposed26 or who experience more severe febrile seizures (eg, with multiple recurrences or complex febrile seizures).

We also found an elevated risk of psychiatric disorders among children with febrile seizures, particularly among the group of children with multiple febrile seizures. Psychiatric comorbidities are common among persons with epilepsy, but the risk was elevated even among children with febrile seizures who did not develop epilepsy. Previous studies have shown that children with febrile seizures are at higher risk of developing a wide range of psychiatric disorders.6,8,10,27 In particular, the dose-response association with the number of febrile seizures has been demonstrated across several different disorders, including mood disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia and related disorders.10 In the present study, we found that, although the 30-year risk of developing psychiatric disorders was 17.2% in the general population, the corresponding risk was 25.0% among children with at least 2 febrile seizures and 29.1% among those with 3 febrile seizures. These estimates, however, only include persons with psychiatric disorders needing treatment in secondary care. They are therefore most likely conservative estimates of the overall burden of psychiatric disorders following febrile seizures. It is unclear whether this increased occurrence is directly related to the recurrent seizures or whether the increase reflects some common underlying risk factors (eg, genetic susceptibility).

In this study, 30-year mortality was not increased in the overall group of children with febrile seizures. There was a slightly elevated mortality risk only in the subgroup of children experiencing recurrent febrile seizures, but this excess risk was restricted to children who also developed epilepsy. Even in this group, the overall mortality was low, which is consistent with previous findings.28,29 Studies of long-term mortality in children with febrile seizures have found a small excess mortality during the first 2 years after complex febrile seizures.29 We were unable to identify children with complex febrile seizures from the Danish National Patient Register, but children with recurrent febrile seizures and those with complex febrile seizures may form part of the same subcohort of children with febrile seizures.

An increased risk of febrile seizures in boys has been reported previously,30,31,32 but to our knowledge little effort has been devoted to investigating causes or consequences of this increased risk in males. In the present study, we found that boys vs girls were at higher risk of febrile seizures at all ages, but this sex difference did not seem to be associated with the prognosis of febrile seizures in terms of recurrence risk, as well as the risk of subsequent psychiatric and neurologic morbidity or mortality. It is not clear why boys are more likely to experience febrile seizures compared with girls. Boys may have a higher underlying susceptibility to seizures33 or be more prone to respiratory tract infections34 compared with girls. Respiratory tract infections are some of the most common causes of fever in childhood, and if boys experience fevers more frequently than girls do, this may explain the findings. Boys may also have more frequent or more severe febrile seizures compared with girls leading to hospital admission. However, we had no clinical information from registers about the febrile seizures (eg, duration, focal vs bilateral or generalized onset, and number of seizures during the illness episode), which would have allowed us to establish whether the febrile seizures were simple or complex.35

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has some strengths. It is based on national registers, which ensures essentially complete coverage and follow-up of all children born in Denmark throughout the study period. This approach allowed us to estimate cumulative incidence rates, which describe the absolute risk of a specified outcome rather than the relative risk and are therefore useful from a clinical perspective. We used data from a period of 30 years of follow-up, allowing us to assess the long-term risk of neurologic and psychiatric morbidity associated with febrile seizures.

The study also has limitations. Information on the occurrence of febrile seizures was entirely register based. The febrile seizure diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Register have previously been reported to have a positive predictive value of 93% (95% CI, 89%-96%) and a completeness of registration of 72% (95% CI, 66%-76%).1 Thus, we may not have captured data for all children with febrile seizures, and our estimates of recurrence risk may therefore be somewhat conservative. Furthermore, registration of febrile seizures changed in 1995 when outpatient and emergency department contacts were included in the register. We found that the risk of epilepsy following recurrent febrile seizures appeared to be somewhat lower in children born after 1995, which may reflect the fact that the register in recent years has captured less severe cases of febrile seizures. The cumulative risk of psychiatric disorders was, however, higher, which is likely explained by the concurrent inclusion of outpatient contacts in the Psychiatric Central Research Register as well as increasing diagnostic trends.36 We found that the admission rate with febrile seizures increased over time, which contrasts with the development seen in other populations, such as the United States.37 However, when restricting data to diagnoses based on inpatient admissions only, the rate of admission did not change between 1990 and 2016.

Conclusions

A history of recurrent febrile seizures appears to carry a high risk of epilepsy and psychiatric morbidity but may increase mortality only in individuals who later develop epilepsy. Thus, parents and medical professionals should be aware of early signs and symptoms of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders in children with a history of febrile seizures, and especially in children with recurrent febrile seizures, to ensure early detection and treatment of these disorders.

eFigure. Flowchart of the Overall Study Population and the Three Subpopulations of Children With ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 Febrile Seizures

eTable 1. Cumulative Incidence of Recurrent Febrile Seizures in Children Following Their 1st, 2nd, And 3rd Febrile Seizure According to Age at Their Latest Seizure

eTable 2. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Psychiatric Disorders and Death, Depending on the Number of Febrile Seizures, With and Without Adjustment for Epilepsy, in Children Born in Denmark Between 1977 and 2011

eTable 3. Cumulative Risk of Febrile Seizures, Epilepsy, Psychiatric Disorders, and Death From Birth and in Children Following Their 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Febrile Seizure, in Children Born in Denmark Between 1977 and 2011 and Between 1995 and 2011

References

- 1.Vestergaard M, Obel C, Henriksen TB, et al. . The Danish National Hospital Register is a valuable study base for epidemiologic research in febrile seizures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):61-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forsgren L, Sidenvall R, Blomquist HK, Heijbel J. A prospective incidence study of febrile convulsions. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79(5):550-557. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser WA. The prevalence and incidence of convulsive disorders in children. Epilepsia. 1994;35(suppl 2):S1-S6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb05932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Febrile Seizures Consensus statement—febrile seizures: long-term management of children with fever-associated seizures. Pediatrics. 1980;66(6):1009-1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Darefsky AS, et al. . Predictors of recurrent febrile seizures: a prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(4):371-378. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410045006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB, Christensen J, Madsen KM, Olsen J, Mortensen PB. Febrile seizures and risk of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;73(2-3):343-349. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard M, Pedersen CB, Sidenius P, Olsen J, Christensen J. The long-term risk of epilepsy after febrile seizures in susceptible subgroups. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):911-918. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertelsen EN, Larsen JT, Petersen L, Christensen J, Dalsgaard S. Childhood epilepsy, febrile seizures, and subsequent risk of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154654. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(19):1029-1033. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197611042951901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreier JW, Pedersen CB, Cotsapas C, Christensen J. Childhood seizures and risk of psychiatric disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(2):99-108. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30351-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel N, Ram D, Swiderska N, Mewasingh LD, Newton RW, Offringa M. Febrile seizures. BMJ. 2015;351:h4240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Hauser WA, Leventhal JM. Predictors of recurrent febrile seizures: a metaanalytic review. J Pediatr. 1990;116(3):329-337. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82816-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CC, Chang YC. The long-term effects of febrile seizures on the hippocampal neuronal plasticity—clinical and experimental evidence. Brain Dev. 2009;31(5):383-387. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavlidou E, Panteliadis C. Prognostic factors for subsequent epilepsy in children with febrile seizures. Epilepsia. 2013;54(12):2101-2107. doi: 10.1111/epi.12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai JD, Mou CH, Chang HY, Li TC, Tsai HJ, Wei CC. Trend of subsequent epilepsy in children with recurrent febrile seizures: a retrospective matched cohort study. Seizure. 2018;61:164-169. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Elveback LR, Kurland LT. The risk of epilepsy following febrile convulsions. Neurology. 1979;29(3):297-303. doi: 10.1212/WNL.29.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):30-33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ICD10Data.com.2019. ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code R56.00. Simple febrile convulsions. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/R00-R99/R50-R69/R56-/R56.00. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 20.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coviello V, Boggess M. Cumulative incidence estimation in the presence of competing risks. Stata J. 2004;4(2):103-112. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0400400201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marubini E, Valsecchi M. Analysing Survival Data from Clinical Trials and Observational Studies. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byeon JH, Kim GH, Eun BL. Prevalence, incidence, and recurrence of febrile seizures in Korean children based on national registry data. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14(1):43-47. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonald BK, Johnson AL, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. Febrile convulsions in 220 children—neurological sequelae at 12 years follow-up. Eur Neurol. 1999;41(4):179-186. doi: 10.1159/000008048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verity CM, Greenwood R, Golding J. Long-term intellectual and behavioral outcomes of children with febrile convulsions. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(24):1723-1728. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seinfeld SA, Pellock JM, Kjeldsen MJ, Nakken KO, Corey LA. Epilepsy after febrile seizures: twins suggest genetic influence. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;55:14-16. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillberg C, Lundström S, Fernell E, Nilsson G, Neville B. Febrile Seizures and Epilepsy: Association With Autism and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;74(suppl C):80-86.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stampe NK, Glinge C, Jabbari R, et al. . Febrile seizures prior to sudden cardiac death: a Danish nationwide study. Europace. 2018;20(FI2):f192-f197. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, Ostergaard JR, Pedersen CB, Olsen J, Christensen J. Death in children with febrile seizures: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):457-463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61198-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vestergaard M, Basso O, Henriksen TB, Østergaard JR, Olsen J. Risk factors for febrile convulsions. Epidemiology. 2002;13(3):282-287. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lennox-Buchthal MA. Febrile convulsions: a reappraisal. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1973;32(suppl):1-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esmaili Gourabi H, Bidabadi E, Cheraghalipour F, Aarabi Y, Salamat F. Febrile seizure: demographic features and causative factors. Iran J Child Neurol. 2012;6(4):33-37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mejías-Aponte CA, Jiménez-Rivera CA, Segarra AC. Sex differences in models of temporal lobe epilepsy: role of testosterone. Brain Res. 2002;944(1-2):210-218. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)02691-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falagas ME, Mourtzoukou EG, Vardakas KZ. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infections. Respir Med. 2007;101(9):1845-1863. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg AT, Shinnar S. Complex febrile seizures. Epilepsia. 1996;37(2):126-133. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atladóttir HO, Parner ET, Schendel D, Dalsgaard S, Thomsen PH, Thorsen P. Time trends in reported diagnoses of childhood neuropsychiatric disorders: a Danish cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(2):193-198. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okubo Y, Handa A. National trend survey of hospitalized patients with febrile seizure in the United States. Seizure. 2017;50:160-165. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flowchart of the Overall Study Population and the Three Subpopulations of Children With ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 Febrile Seizures

eTable 1. Cumulative Incidence of Recurrent Febrile Seizures in Children Following Their 1st, 2nd, And 3rd Febrile Seizure According to Age at Their Latest Seizure

eTable 2. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Psychiatric Disorders and Death, Depending on the Number of Febrile Seizures, With and Without Adjustment for Epilepsy, in Children Born in Denmark Between 1977 and 2011

eTable 3. Cumulative Risk of Febrile Seizures, Epilepsy, Psychiatric Disorders, and Death From Birth and in Children Following Their 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Febrile Seizure, in Children Born in Denmark Between 1977 and 2011 and Between 1995 and 2011