This article is a systematic review of the literature on racial and/or ethnic disparities in NICU quality of care; we note important areas of intervention for improving infant outcomes.

Abstract

Video Abstract

CONTEXT:

Racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes of newborns requiring care in the NICU setting have been reported. The contribution of NICU care to disparities in outcomes is unclear.

OBJECTIVE:

To conduct a systematic review of the literature documenting racial/ethnic disparities in quality of care for infants in the NICU setting.

DATA SOURCES:

Medline/PubMed, Scopus, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health, and Web of Science were searched until March 6, 2018, by using search queries organized around the following key concepts: “neonatal intensive care units,” “racial or ethnic disparities,” and “quality of care.”

STUDY SELECTION:

English language articles up to March 6, 2018, that were focused on racial and/or ethnic differences in the quality of NICU care were selected.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Two authors independently assessed eligibility, extracted data, and cross-checked results, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Information extracted focused on racial and/or ethnic disparities in quality of care and potential mechanism(s) for disparities.

RESULTS:

Initial search yielded 566 records, 470 of which were unique citations. Title and abstract review resulted in 382 records. Appraisal of the full text of the remaining 88 records, along with the addition of 5 citations from expert consult or review of bibliographies, resulted in 41 articles being included.

LIMITATIONS:

Quantitative meta-analysis was not possible because of study heterogeneity.

CONCLUSIONS:

Overall, this systematic review revealed complex racial and/or ethnic disparities in structure, process, and outcome measures, most often disadvantaging infants of color, especially African American infants. There are some exceptions to this pattern and each area merits its own analysis and discussion.

The preterm birth rate is 49% higher for black or African American women than for all other women in the United States.1 Preterm birth is linked to increased mortality, making preterm birth or very low birth weight (VLBW) the leading cause of infant death among black infants.2 An additional component to racial and/or ethnic inequity in infant outcomes is differences in NICU quality of care stratified by race and/or ethnicity.3 Disparities in quality have been found in other areas of health care, including, for instance, cancer care,4 cardiovascular care,5 and pediatric care.6

The advantage of addressing disparities in care delivery is that they are amenable to improvement through quality improvement (QI) methodology, with the potential for spreading solutions at scale with long-term benefit. To facilitate approaches for measurement, benchmarking and improvement, we have conducted a systematic review of the literature to summarize racial and/or ethnic disparities in quality of NICU care delivery. Health care is delivered within a context of societal, institutional, and interpersonal racism that may contribute to disparate care and outcomes.

Methods

The authors conducted a systematic review of the literature in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.6 The search strategies and inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in advance and documented in a protocol.

We used Donabedian’s7 structure-process-outcome quality of care framework to review the literature on racial and/or ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Measuring quality of care is nuanced and this literature cannot always isolate measures or disparities strictly related to quality of neonatal care, biological diversity, maternal comorbidities, or a challenged socioeconomic environment. Research in this area is observational and open to interpretation. In determining which articles to include or exclude, we relied on expert assessments of measures of quality8 and the principle that quality measures should be malleable. We sorted articles by structure-process-outcome according to the dominant theme in the article and by grouping similar articles.

Data Sources

We searched Medline/PubMed, Scopus, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health, and Web of Science until March 6, 2018, using search queries organized around the following key concepts: “neonatal intensive care units,” “racial or ethnic disparities,” and “quality of care.” The full search strategy for the Medline/PubMed query, which also formed the basis for the other database queries, can be found in Supplemental Information. Additional articles were collected on the basis of recommendations from experts in the field and reviewing bibliographies of relevant articles.

Study Selection

According to the eligibility criteria outlined in our protocol, we screened all English language articles retrieved and available in full text through March 6, 2018, using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

-

Studies that reported data on the quality of NICU care inclusive of the following:

process-of-care measures (eg, use of appropriate interventions);

outcome measures insofar as they are used as quality metrics (eg, morbidity or mortality were used to indicate quality of care);

structural measures of care (eg, use of or access to health care services insofar as this is indicative of quality);

patient evaluations of care (eg, patient satisfaction); or

direct observations of care; and

report data stratified by patient race and/or ethnicity (either within or between NICUs, hospitals, or regions).

Exclusion criteria:

-

Studies that reported the following:

only maternal or post-NICU discharge measures of quality;

only outcomes that may not reflect quality of care (eg, morbidity or mortality rates not at the NICU level);

only data from a non-US setting,

data not stratified by race and/or ethnicity,

non–English language publication, or

or nonhuman studies.

Data Extraction

Articles were divided into structure-process-outcome according to their dominant theme, with 1 article summarized under both structure and process.9 For this review, we categorize analyses of minority serving hospitals under the structure domain. Articles were further categorized thematically. Two authors independently assessed eligibility, extracted data, and cross-checked results, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Information extracted focused on racial and/or ethnic disparities in quality of care and potential mechanism(s) for disparities. We did not perform additional bias assessment.

Results

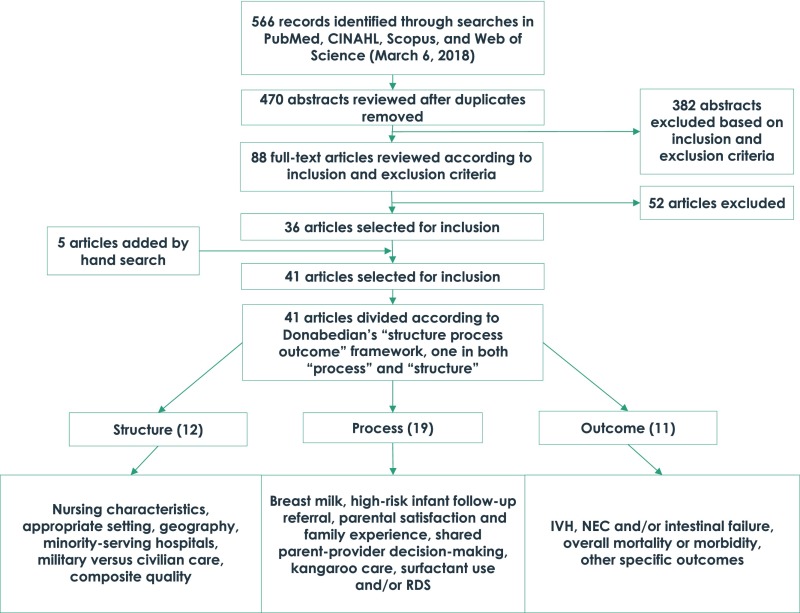

Figure 1 displays our search results. Of an initial pool of 566 potentially eligible records, 470 represented unique citations. After review of titles and abstracts, we excluded a further 382 records. After examination of the full texts of the remaining 88 records, we retained 36 records for the systematic review. Five records were added based on expert suggestion and review of bibliographies of relevant articles for a total of 41 selected for inclusion.

FIGURE 1.

Replicable search results. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Structure

We identified 12 articles that examined the role of structure or health systems in racial and/or ethnic disparities in quality of NICU care (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Systematic Review Structure

| Variable, Author, and Reference | Demographics of Study (If Available) | Outcome(s) of Interest | Summary of Main Findings | Relative Risk or Measures of Effect (If Applicable) | Suggested Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing characteristics | |||||

| Lake et al10 | 8252 infants with VLBW | Relationship between nursing characteristics and hospital-level disparities in VLBW outcomes | Higher infection rates, higher rates of discharge without breast milk, more nurse understaffing, and poorer practice environments in hospitals with a high proportion of black patients (“high-black”) compared with hospitals with a low proportion (“low-black”); 70% of black infants with VLBW are born at high-black hospitals, so these disparities strongly affect them. Black infants are particularly disadvantaged even in high-black hospitals when it comes to breastfeeding. Black infants and white infants no different within hospitals overall. | aOR of nosocomial infection in high-black versus low: 1.64. aOR for discharge without BM high versus low: 1.61. Differences not significant when controlling for nursing characteristics. Practice Environment (scale of 1–4): high-black 2.95, low-black 3.16, P = .004. Understaffing (measured in fraction of a nurse per infant needed to meet guidelines): high-black 0.22, low-black 0.14, P = .004. | Nursing characteristic differences likely due to financial constraints and poor management. Nursing characteristics likely drive infection and discharge without breast milk. |

| Lake et al11 | Random sample survey of licensed nurses in 4 large US states: 1037 staff nurses in 134 NICUs. | Average patient load, individual nurses’ patient load, professional nursing characteristics, nurse work environment, and nursing care missed on the last shift. | More care activities are missed in hospitals serving a higher proportion of black infants (>31%) than in hospitals that serve a smaller proportion of black infants (<11%). This indicates that quality of care may be lower in high-black hospitals. | Nurses in high-black NICUs missed nearly 50% more care activities than those in low-black NICUs (average 1.51 vs 1.05 activities missed per shift, P = .03). | Disparities in missed care were likely due to higher patient-to-nurse ratios in high-black hospitals. High-black hospitals were more likely to have larger proportion of Medicaid patients, which can lead to financial strain and therefore fewer staffing resources. |

| Appropriate setting | |||||

| Bronstein et al12 | Infants with VLBW; 1118 white and 1478 infants of color. | Delivery in hospitals with NICUs. | Mothers of color with early prenatal care were the group most likely to deliver their infants with VLBW in hospitals with NICUs. White women with Medicaid were more likely to be transferred before birth than white women with private insurance. | OR: 1.353 (1.119–1.636) for mothers of color versus white mothers. OR: 1.733 (1.316–2.283) for mothers of color with Medicaid and early prenatal care versus white mothers with no Medicaid and early prenatal care. | Women with early prenatal care are likely able to contact their care providers sooner if they go into labor prematurely or are part of care systems with established referral relationships for emergency situations. Some hospitals may selectively retain privately insured women for high-risk deliveries, refer less Medicaid-insured women to subspecialty regional centers. |

| Gould et al13 | Data from 1 state (analyzed by region) from 1989 to 1993 of 24 094 live-born infants with VLBW. | Factors associated with likelihood of VLBW birth at a Level 1 hospital (hospital without a NICU or 24-h on-call neonatologist) | 10.5% (24 094) infants with VLBW were delivered in Level 1 hospitals. Significant regional variation: from 3.1% to 24.3%. The odds were decreased for African Americans and Southeast Asians and increased in Hispanic women as compared with white non-Hispanic women. For all women, less than adequate prenatal care, living in a 50%–75% urban zip code, and living >25 miles from the nearest NICU significantly increased the odds of VLBW delivery at a Level 1 hospital. | Odds of inappropriate delivery site ranged from 0.37 to 2.75 across California’s 9 geographic perinatal regions. OR for African Americans: 0.65. OR for Southeast Asians: 0.54. OR for white 1.00. OR for Hispanic 1.16. | Common to all 3 racial ethnic groups: risks of Level 1 VLBW delivery associated with (1) less than adequate prenatal care, (2) living in a zip code that is only 50%–75% urban, and (3) living at a distance to a hospital with a NICU. However, regional differences in the odds for inappropriate VLBW birth remained after adjusting for contributing socio-demographics and geographical risk factors. Hispanic teenage pregnancies were at particular risk of inappropriate birth setting. |

| Gortmaker et al14 | Data from 4 states for 1978 and 1979 used to estimate survival curves for first 24 h of life. | Survival by hospital setting (high-technology centers versus urban or rural centers). | Among 750–1000 g infants: cumulative probability of survival at Level III center was ∼0.63 among white infants and ∼0.70 among black infants. Among 1000–1500 g: ∼0.90 among white infants and ∼95 among black infants (Level III). | Black infants had better access to specialized services. In Washington and Tennessee, >50% of black infants with VLBW were born in specialized centers. For all birth weight categories, survival during the first 96 h was greater among black than white infants at the same level of hospital care. Birth in a Level III center conferred the highest survival rates. | Birth in a Level III center greatly improves infant outcomes. Differential access to specialized Level III centers between black infants and white infants may explain the higher observed survival rates in black infants. |

| Geography | |||||

| Hebert et al15 | VLBW deliveries in New York City from 1996 to 2001 to non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white mothers. | The role of geographic distribution of hospitals in the racial disparity in the use of top-tier hospitals (those in the lowest tertile of hospitals ranked by ratio of observed to expected deaths). | Black mothers less likely to deliver in top-tier hospitals (white = 44%, black = 28%; P < .001). Top-tier hospitals less likely to be in black mothers’ neighborhoods (white = 40%, black = 33%; P < .001). Distance, however, did not contribute to the disparity in use of top-tier hospitals: mothers of both races often bypassed their neighborhood hospital (black = 62% bypassed, white = 71%; P < .001). | OR of relative risk black or white of probability that a mother of a neonate with VLBW used a top-tier hospital: 0.6. | The influence of geography on the use of top-tier hospitals for mothers of neonates with VLBW is complex. Other personal and hospital characteristics, not just distance or geography, also influenced hospital use in New York City. Researchers provide insights to those who would report risk adjusted hospital mortality rankings to foster top-tier selection. However, improving quality at poorly performing facilities could make greater impact than encouraging choice of better-performing hospitals. |

| Featherstone et al16 | The linked birth and death records of singleton infants with VLBW born between 2010 and 2012 (n = 2030). | Impact of travel time from maternal residence to delivery hospital on neonatal mortality rate. | No significant association between travel time to delivery hospital and neonatal mortality after adjusting for confounders. 1-wk increase in GA and non-Hispanic black mothers (versus non-Hispanic white mothers) were associated with lower odds of neonatal death, whereas non- NICU admission at birth was associated with increased odds of death. | 1-wk increase in GA associated with lower odds of mortality: (OR: 0.61); non-Hispanic black mothers (OR: 0.68) associated with lower death; non-NICU admission at birth (OR: 5.9) increased odds of death. | A high proportion of neonatal deaths occurred within 24 h of birth. Underlying causes of death, particularly in the first 24 h, are not sensitive to access to care but are more closely aligned with other maternal, neonatal, or hospital-level factors. |

| Minority-serving hospitals | |||||

| Morales et al17 | 74 050 infants with VLBW treated by 332 VON hospitals between 1995 and 2000 | Whether there is an association between proportion of black infants with VLBW treated at a hospital and neonatal mortality for black and white infants with VLBW. “Minority-serving” defined as >35% of infants with VLBW treated were black; other categories were <15% and 15%–35%. | Minority-serving hospitals had significantly higher risk-adjusted neonatal mortality rates than <15%. Differences were not explained by either hospital or treatment variables. | Risk-adjusted neonatal mortality rates in >35% black hospitals compared with <15%: white OR: 1.30, black OR: 1.29, pooled OR: 1.28 | Minority-serving hospitals may be providing lower quality of care to infants with VLBW. Results were not explained by other hospital characteristics looked at in this study (location, teaching status, % admissions covered by Medicaid), but there could be other characteristics not looked at in this study that might have an effect. |

| Howell et al18 | 11781 infants 500–1499 g in New York City born between 1996 and 2001. | Risk-adjusted neonatal mortality rates for each New York City hospital and racial and ethnic distribution among those hospitals. | White infants with VLBW more likely to be born in lowest mortality tertile of hospitals (49%) compared with black infants with VLBW (29%). Estimated that if black women delivered in same hospitals as white women, black VLBW mortality rates would be reduced by 6.7 per 1000 VLBW births or disparity would be reduced by 34.5%. | — | — |

| Military vs civilian care | |||||

| Kugler et al19 | Black or white singleton live births in Pierce County delivered between 1982 and 1985. | The effect of system of care (military care) on differences in low birth weight and neonatal mortality between black infants and white infants. | (Note: not including findings on low birth weight findings because not quality of care.) Civilian black infants had approximately twice the neonatal death rates of civilian white infants. The neonatal mortality rates for military black infants, however, did not differ significantly from either group of white infants. Disparity did not apply to birth weight <2500 g. | Civilian black infants versus civilian white infants crude risk ratio: 2.33; civilian black infants versus military black infants crude risk ratio: 3.08; military black infants versus military white infants crude risk ratio: 1.04. | Military care appeared to be associated with a protective effect for neonatal mortality for black infants. This effect was not due to differences in birth weight distribution or to the quantity of prenatal care received. The effect was most prominent for normal weight black infants, especially for those from low income census tracts. |

| Composite quality | |||||

| Profit et al9 | 18 616 infants with VLBW in 134 California NICUs between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014. | Baby-MONITOR score (a composite of 9 process and outcome measures of quality). For each NICU, a risk-adjusted composite and individual component quality score for each race and ethnicity. | Composite quality scores ranged by 5.26 standard units (range: −2.30 to 2.96). Non-Hispanic white infants higher on measures of process compared with non-Hispanic black infants and Hispanic infants. Compared with white infants, non-Hispanic black infants scored higher on measures of outcome; Hispanic infants scored lower on 7 of the 9 Baby-MONITOR subcomponents. | Difference between highest and lowest performing NICUs was large (5.2 standard units). | Some of the disparity created by inferior performance among modifiable measures of process rather than outcome, suggesting a critical role for QI efforts. |

| Howell et al20 | 7177 infants, GA 24–31 wk (very preterm) | Mortality or severe neonatal morbidity | Morbidity and mortality higher among black and Hispanic than white VPTBs. Risk-adjusted morbidity and mortality rate was twice as high for VPTBs in hospitals in the highest morbidity and mortality tertile than those born in the lowest tertile hospitals. Black and Hispanic VPTBs were more likely to occur in the highest morbidity and mortality hospitals than white. Most of the disparity can be attributed to differences in infant health risks, but birth hospital also plays a significant role. | Percentage of disparity explained by birth hospital: black-white = 40% (95% CI, 30%–50%); Hispanic-white 30% (95% CI, 10%–49%). | Distance to the hospital, insurance, hospital structural characteristics, patterns of racial segregation, community factors, physician referral, risk perception, patient choice, access, and the management of medical emergencies during pregnancy may all contribute to black and Hispanic women giving birth at hospitals with higher mortality and morbidity rates. |

“African American” and “black” are often used interchangeably in the literature reviewed. In this table, we use the same language as the articles cited. aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BM, breast milk; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; VON, Vermont Oxford Network; VPTB, very preterm birth; —, not applicable.

Nursing Characteristics

The authors of 2 articles10,11 addressed disparities in NICU nursing characteristics and how they related to outcomes, both finding that high black-serving hospitals delivered lower quality of care. Lake et al10 found that infants with VLBW born in high black concentration hospitals had worse outcomes as well as more nurse understaffing and poorer practice environments. In addition, Lake et al11 surveyed NICU nurses in 4 US states to understand how nurse staffing and work environment affects outcomes. They found that the patient-to-nurse ratio was significantly higher in high black-serving hospitals and NICUs in high black-serving NICUs missed nearly 50% more nursing care than those in low black-serving NICUs.

Appropriate Setting

The authors of 2 studies looked at disparities in birth in appropriate settings,12,13 and the authors of 1 study looked at the benefits of being born in an appropriate setting,14 often finding that mothers of color benefit in both scenarios. In a study of Alabama VLBW births between 1988 and 1990, Bronstein et al12 found that mothers of color with early prenatal care were more likely than white mothers to give birth to infants with VLBW in hospitals with NICUs. Similarly, in a California study, Gould et al13 found that black women are less likely to give birth to infants with VLBW in inappropriate settings than white and Hispanic women.

Gortmaker et al14 asked whether the benefit of NICU technology was equally beneficial to black and white infants with VLBW. They found significant differences in survival by type of hospital, with infants with VLBW born in hospitals with NICUs more likely to survive. However, the researchers found greater survival rates for black infants compared with white infants at the same level of hospital care. The authors suggest that this indicates that black infants with VLBW have better survival than white infants in general, not that there is a differential in quality.

Geography

In 2 articles,15,16 researchers investigated the relationship between geography and racial disparities in quality of care; in both articles, it was found that proximity did not make a difference in terms of accessing a high-quality hospital15 or lowering neonatal mortality rate.16 Hebert et al15 found that black women were less likely to deliver in top-tier hospitals and that top-tier hospitals were less likely to be in black women’s neighborhoods. Distance, however, did not contribute to the racial disparity in use of top-tier hospitals, in that black and white women often bypassed their neighborhood hospital. Using a different approach, Featherstone et al16 found no significant association between travel time to delivery hospital and neonatal mortality. However, they found that black infants experienced lower odds of neonatal death overall.

Minority-Serving Hospitals

Researchers for 2 articles17,18 looked at the relationship between the proportion of black or white infants with VLBW in a hospital and its neonatal mortality rate, finding that hospitals with more black infants were of lower quality. Morales et al17 found that “minority-serving” hospitals (defined as hospitals where >35% of infants with VLBW that were treated were black) had significantly higher risk-adjusted neonatal mortality rates than hospitals with <15% black infants, and that these differences were not explained by hospital or treatment variables. Similarly, Howell et al18 examined which hospitals black and white infants were most likely to be born in. They found that white infants were more likely to be born in hospitals in the lowest tertile of mortality rates (49%) compared with black infants with VLBW (29%) in New York City hospitals. They estimated that if black women gave birth in the same hospitals as white women, black VLBW mortality rates would be significantly reduced.

Military Versus Civilian Care

In looking at the influence of health care systems (military hospital versus civilian hospital) on neonatal mortality, Kugler et al19 found that military care appeared to be associated with a protective effect for neonatal mortality for black infants in Pierce County, Washington. They found that in civilian care, black infants had approximately twice the neonatal death rates of white infants, but that difference disappeared in military care, suggesting a protective effect of military care for black infants.

Composite Quality

We identified 2 articles9,20 in which the authors investigated multiple quality measures, sometimes combining them into an explicit composite measure. Both suggest that infants of color are vulnerable to low-quality NICU care. Profit et al9 used Baby-MONITOR (a composite measure of NICU quality) to study disparities within and between NICUs wherein a higher score indicates better quality of care. They found significant variation both between and within NICUs. Although non-Hispanic white infants scored higher on measures of process, non-Hispanic black infants scored higher on outcome measures. Overall, the authors found that, “…as [NICU] quality scores rise, whites tend to perform better than African Americans. However, African Americans in high-performing NICUs often fare better than African Americans in low-performing NICUs.” Howell et al20 examined differences in neonatal morbidity and mortality rates in very preterm infants by site of delivery in New York City hospitals. The authors created a composite measure of mortality and morbidity and found it to be higher among black and Hispanic than white very preterm infants. The risk-adjusted morbidity and mortality rates were twice as high for these infants in hospitals in the highest morbidity and mortality tertile than those born in lowest tertile hospitals. Black and Hispanic very preterm births were more likely to occur in the highest morbidity and mortality hospitals. The authors20 found that although differences in infant risk factors accounted for a large portion of the disparity overall, birth hospital still accounted for 30% to 40% of the explained disparity in outcomes for black or Hispanic infants compared with white infants.

Processes

We identified 19 articles in which disparities in NICU care processes were addressed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Systematic Review Process

| Variable, Author, and Reference | Demographics of Study (If Available) | Outcome(s) of Interest | Summary of Main Findings | Relative Risk or Measures of Effect (If Applicable) | Suggested Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast milk | |||||

| Lee et al21 | 90% of infants admitted into Californian NICUs with birth weight of 500–1500 g and born at or transferred to a CPQCC center within 2 d of birth from 2006 to 2008. | Any amount of BMF at time of discharge. Hospitals were divided into quartiles by hospital percentage of each race, and BMF rates by race were compared. | BMF found to be higher for all racial and ethnic groups in hospitals with more white mothers. Differences were less pronounced for Hispanic mothers than for black mothers. African Americans had the lowest rates of BMF when cared for in hospitals with more African Americans (43%) versus hospitals with fewer African Americans (59%, P = .003). On the other hand, white mothers had the lowest BMF rates (49%) in hospitals with the fewest white mothers. | With risk adjustment, white mothers were more likely to engage in BMF when there were more white mothers at that hospital (odds ratio 1.15 for 10% increase in white mothers, 95% confidence interval 1.04–1.28). Black mothers were less likely to engage in BMF when more black mothers were at the hospital (odds ratio 0.80 for each 10% increase in black mothers, 95% confidence interval 0.67–0.97). | Hospitals serving more patients of color were less likely to have premature infants fed breast milk for all races. Targeting such hospitals for QI may help to improve BMF rates overall and reduce disparities. |

| Profit et al9 | 18 616 infants with VLBW in 134 California NICUs between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2014. | Baby-MONITOR score (a composite of 9 process and outcome measures of quality). For each NICU, a risk-adjusted composite and individual component quality score for each race and ethnicity. | Composite quality scores ranged by 5.26 standard units (range −2.30 to 2.96). Non-Hispanic white infants higher on measures of process compared with non-Hispanic black infants and Hispanic infants. Compared with white infants, non-Hispanic black infants scored higher on measures of outcome; Hispanic infants scored lower on 7 of the 9 Baby-MONITOR subcomponents. | Difference between highest and lowest performing NICUs was large (5.2 standard units). | Some of the disparity created by inferior performance was among modifiable measures of process rather than outcome, suggesting a critical role for QI efforts. |

| Riley et al38 | 410 VLBW infants born between February 2008 and 2012 and admitted to the Level III NICU at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. | HM feeding at discharge as mitigated by neighborhood structural factors. | In bivariate analysis HM feeding at discharge was negatively correlated with neighborhood structural factors including neighborhood concentrated disadvantage (OR: 0.72; CI: 0.60–0.86), neighborhood violent crime rate (OR: 0.93; CI: 0.89–0.98), and negatively correlated with patient factors including black race and/or ethnicity (OR: 0.41; CI: 0.24–0.70). In multivariate analysis, only maternal race and/or ethnicity (OR: 1.04; CI: 1.00–1.09), WIC eligibility, and length of NICU hospitalization predicted HM feeding at discharge for the entire cohort. The interaction between access to a car and race and/or ethnicity significantly differed between black and white or Asian mothers, although the predicted probability of HM feeding at discharge was not significantly affected by access to a car for any racial and/or ethnic subgroup. | In multivariate analysis, maternal race and/or ethnicity (OR: 1.04; CI: 1.00-1.09) predicted HM feeding at discharge for entire cohort. | Socioeconomic status affected breastfeeding rates in all racial/ethnic groups, but disproportionately affected black mothers to a greater degree than white or Hispanic mothers. |

| Cricco-Lizza22 | 130 black non-Hispanic mothers enrolled in the New York Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for WIC were general informants. From this group, 11 key informants had close follow-up during pregnancy and the first postpartum year. | Audiotaped interviews and field notes were analyzed for mothers’ descriptions of infant-feeding education and support from nurses and physicians. | Found limited breastfeeding education and support during pregnancy, childbirth stay in NICU, postpartum, and recovery in the community. They also expressed trust or distrust concerns and varying degrees of anxiety about how they were treated by nurses and physicians. | N/A | Lack of trusting relationships (neglecting the affective elements of health care). |

| Fleurant et al23 | 362 racially diverse mothers of infants with VLBW. | HM feeding at discharge. | For all 362 mothers, WIC negatively predicted HM feeding at discharge and maternal goal near time of discharge positively predicted HM feeding at discharge. Perceived breastfeeding support from infant’s maternal grandmother negatively predicted HM feeding at discharge. | For all mothers: WIC eligibility (OR: 0.34; 0.15–0.75; P = .008), breastfeeding support from mothers’ mother (OR: 0.45; 0.26–0.79; P = .005), goal of any HM near discharge (OR: 8.38; 3.42–20.53; P ≤ .001). Stratified by race and/or ethnicity: “For black mothers, support from the mother’s mother (OR 0.27 [95% CI 0.11–0.68], P = .006). | Goal of HM at discharge predicting HM feeding consistent with other research. Surprised by finding that higher maternal grandmother support predicts lower BM. Suggestion that this relates to maybe the perception of support (rather than actual support) and that mothers coparenting with their own mothers are more likely to experience parenting stress. |

| Brownell et al24 | Mothers of infants eligible to receive donor milk (≤32 weeks’ gestation or ≤1800 g) born between August 2010 and 2015. | Odds of nonconsent. | Of the 486 mother-infant dyads from the first 5 y of the donor milk program, nonwhite race (aOR: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.04–2.76) and increasing GA (aOR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03–1.21) independently predicted nonconsent. Each year the program existed, there was a 48% reduction in odds of nonconsent (aOR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.43–0.62). The most common reason given for nonconsent was ‘‘it’s someone else’s milk.’’ | Nonwhite race (aOR: 1.69; 95% CI: 1.04–2.76); increasing GA (aOR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03–1.21) independently predicted nonconsent. | Program duration was associated with reduced nonconsent rates and may reflect increased exposure to information and acceptance of donor milk use among NICU staff and parents. Despite overall improvements in consent rates, race-specific disparities in rates of nonconsent for donor milk persisted after 5 y of this donor milk program. |

| Boundy et al25 | Data from CDC’s 2015 Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care survey, linked to the 2011–2015 US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. | The use of mother’s own milk and donor milk in hospitals with NICUs by the percentage of non-Hispanic black residents in the hospital postal code area, categorized as being above or below the national average (12.3%). | In postal codes with >12.3% black residents, 48.9% of hospitals reported using mothers’ own milk in ≥75% of infants in the NICU, and 38.0% reported not using donor milk, compared with 63.8% and 29.6% of hospitals, respectively, in postal codes with ≤12.3% black residents. | N/A | Differences found may be related to variations in health care personnel support, hospital policies and practices, mothers’ knowledge and access to information, and community-level support for breastfeeding. Donor milk use might also be affected by hospital proximity to milk banks, state regulations, and hospital policies related to the provision of donor milk and insurance reimbursement. |

| Vohr et al26 | Infants weighing ≤1250 g cared for in an open-bay NICU (January 2007–August 2009) (n = 394) versus those in a SFR NICU (January 2010–December 2011) (n = 297). | Human milk provision at 1, 4 wk and discharge, and 4 wk volume (mL/kg/d). Also, 18–24 mo Bayley III. | Infants cared for in the SFR NICU had higher Bayley III cognitive and language scores, higher rates of human milk provision at 1 and 4 wk, and higher human milk volume at 4 wk. The SFR NICU was associated with a 2.55-point increase in Bayley cognitive scores and 3.70-point increase in language scores. Every 10 mL/kg per d increase of human milk at 4 wk was associated with increases in Bayley cognitive, language, and motor scores (0.29, 0.34, and 0.24, respectively). Medicaid was associated with decreased cognitive and language scores, and low maternal education and nonwhite race with decreased language scores. | Nonwhite race with decreased language scores (−5.8). | Authors do not comment on race or ethnicity but note that low maternal education, poverty, and insurance status likely mean less ability to spend time in the NICU and provide breast milk, thus leading to lower Bayley III cognitive scores. |

| High-risk infant follow-up referrals | |||||

| Barfield et al27 | 1233 infants with VLBW (<1200 g) in Massachusetts born January 1998–June 2003 | Rates of referral and time to referral by race and/or ethnicity. | Black infants had lowest referral rates, especially at 0–12 mo. 12% black infants not referred at all, compared with 6.8% overall. | aHR of referral of black non-Hispanic infants compared with white non-Hispanic infants was 0.85. | Possible that minority families are less confident in their ability to access specialty health care services, such as EI. Also mentions barriers to access, physician mistrust, concerns and/or misunderstandings regarding treatment, and disparities in insurance status (which was included and adjusted for when calculated aHR, but mentioned in discussion). |

| Hintz et al28 | CPQCC infants <1500 g, 2010–2011 | High-risk infant follow-up referral rates. | Lower odds of referral for infants with maternal race Hispanic or African American versus white. | aOR compared with white: African American: 0.58, Hispanic: 0.65. | Previous research has pointed to issues of noncompliance and lacking support systems; in unadjusted analyses, hospitals serving highest proportion of African American infants have lower referral rates overall. |

| Parental satisfaction and family experience | |||||

| Martin et al29 | Self-reports from non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white participants who had an infant born at a GA ≤35 wk or birth wt <2000 g, presenting within 2 mo after NICU discharge to any 1 of 30 Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia primary care centers between January 1, 2010, and January 1, 2013. | Parental reported trust, communication style, expectations of the health care system, and satisfaction with their physician and the NICU course. Collected parental data included sex, age, employment, education, home ownership, ethnicity, race, marital status, household resident information, and income. | Although more commenting parents were white (62%) than black (38%), black parent comments were more negative (58% negative vs 42% positive) compared with white parent comments (33% negative vs 67% positive). The nurse-parent relationship and distinct positive and negative nursing behaviors are important factors affecting parental satisfaction with NICU care. Black parents were most dissatisfied with nursing support, wanting compassionate and respectful communication and nurses that were attentive to their children. White parents were most dissatisfied with inconsistent nursing care and lack of informative exchanges, wanting education about their child’s short- and long-term needs. Both groups described a chaotic NICU environment with high nursing turnover. | N/A | Black patients are less likely to report satisfaction with health care, possibly stemming from differences in provider communication styles, clinician’s attitudes, medical mistrust, and perceived racism. Provider uncertainty, biases, and stereotyping may also contribute to unequal treatment. |

| Sigurdson et al30 | Attendees at the 2016 Vermont Oxford Network Quality Congress composed of providers (nurses, physicians, and other clinical specialists) and NICU family advocates. | Open-ended survey of accounts of disparate care. | Study gathered 324 accounts of disparate care, majority described perceived worse care of families, not strictly infants. Accounts described worse care based on intersecting factors of, eg, language, culture or ethnicity, race, etc. Respondents described families receiving neglectful care, judgmental care, and systemic barriers to care. | N/A | Adverse consequences of disparate care for infants mediated through adverse interactions with families more so than through differences in care to infant. Social inequalities shape the content and tone of health care encounters such that families receive worse care based on intersecting factors. |

| Shared parent-provider decision-making | |||||

| Van McCrary et al31 | Two cases in a New York City tertiary care unit. | Nonmedical barriers that impede decision-making in the NICU. | Many NICUs are not equipped to deal with complicated cultural and linguistic barriers that prevent them from communicating effectively with their patients. | N/A | For both families of color in these case studies, a reinforcing cycle of disapproval had formed. Each family made, or had previously made, decisions that the NICU staff did not agree with, so the staff implicitly resented the family. In both cases, care decisions were influenced by social and cultural factors that were misunderstood by NICU medical staff. |

| Tucker Edmonds et al32 | Periviable infants (23.0–24.6 wk) in California, Missouri, and Pennsylvania, 1995–2005. | Resuscitation of periviable infants. | Black race a predictor for neonatal intubation, even when controlling for clustering at the delivery hospital level. | aOR for intubation of black infants compared with white: 1.25. | Likely due to differences in patient preferences (eg, religious beliefs, cultural preferences); hospital-level practices or resources could also be a contributing factor. |

| Kangaroo care | |||||

| Hendricks-Muñoz et al33 | 42 nurses and 143 mothers at 2 New York City hospitals. | Maternal and provider perspectives on KMC and MCP. | Mothers of color perceived that they received less education and access to KMC; nurses of color were more supportive of MCP and KMC. | 61% of mothers of color strongly identified that access to KMC had been limited to them compared with 39% of white mothers; 77% of white mothers compared with only 50% of mothers of color strongly perceived that nurses were supportive in helping them provide KMC for their infant; OR of nurses of color encouraging parent presence compared with white: 2.8. | Cultural and linguistic differences leading to communication difficulties. |

| Surfactant and RDS | |||||

| Hamvas et al34 | Infants with VLBW born 1987–1989 and 1991–1992 in Saint Louis area; 1563 infants in total, 315 deaths. | Effects of surfactant approval on neonatal mortality among black and white infants. | Neonatal mortality decreased more for white than black infants after surfactant was approved; after approval, white VLBW mortality dropped 41% and VLBW mortality for black infants did not change. | Relative risk of death among black newborns with VLBW compared with white, 1987–1989: 0.7. Increased to 1.3 in 1991–1992. | Larger portion of neonatal mortality in white neonates was attributed to RDS, so introduction of surfactant had a larger effect; RDS more prevalent among white infants because fetal pulmonary surfactant matures more slowly in white infants. |

| Ranganathan et al35 | 44 712 African American infants and 73 942 non-Hispanic white infants. | Effects of surfactant approval on neonatal mortality among black and non-Hispanic white infants with VLBW. | Introduction of surfactant therapy in 1990 improved the outcomes for white infants with VLBW more than black. No difference between African American and non-Hispanic white in rate of decline for all categories of mortality between 1985 and 1988; Difference between African American and non-Hispanic white in rate of decline for all except nonrespiratory neonatal between 1988 and 1991. | 1988–1991: Odds of neonatal death from RDS declined 34% in non-Hispanic white infants and only 16% in African American infants (P < .01); odds of death from all respiratory causes declined 41% in non-Hispanic white infants and 22% in African American infants (P < .01). | Differential efficacy of surfactant on non-Hispanic white and African American infants with VLBW. Lungs of African American fetuses mature more rapidly and begin to produce pulmonary surfactant earlier; therefore, exogenous surfactant may have fewer additional benefits; African American infants with VLBW may also respond less favorably than non-Hispanic white infants of same severity. |

| Frisbie et al36 | All US infants born 1989–1990 (5 407 166) and 1995–1998 (10 809 746). | Black-white disparity in infant mortality due to RDS and other causes. | Disparity in RDS mortality between black and white infants increased after introduction of surfactant. Absolute declines in mortality greater for white infants than black infants among LBW infants after the introduction of surfactant. Black infants had a relative survival advantage in presurfactant era; this became a survival disadvantage postsurfactant. | Infant mortality due to RDS in black infants (versus white infants): 1989–1990, OR = 0.832. 1995–1998, OR = 1.114. | Social inequality and differential access to intervention between black and white infants. |

| Howell et al37 | All US infants born 1989–1990 (5 407 166) and 1995–1998 (10 809 746). | Black-white disparity in infant mortality due to RDS and other causes. | Disparity in RDS mortality between black and white infants increased after introduction of surfactant. Absolute declines in mortality greater for whites than blacks among LBW infants after the introduction of surfactant. Black infants had a relative survival advantage in presurfactant era; this became a survival disadvantage postsurfactant. | Infant mortality due to RDS in black infants (versus white infants): 1989–1990, OR = 0.832. 1995–1998, OR = 1.114. | Social inequality and differential access to intervention between black and white infants. |

“African American” and “black” are often used interchangeably in the literature reviewed. In this table, we use the same language as the articles cited. aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BM, breast milk; BMF, breast milk feeding; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence interval; CPQCC, California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative; EI, early intervention; HM, human milk; KMC, kangaroo mother care; LBW, low birth weight; MCP, maternal care partnerships; N/A, not available; OR, odds ratio; SFR, single family room.

Breast Milk

Researchers for 8 articles9,21–26,38 addressed racial disparities in NICU breast milk feeding (BMF), factors important for successful BMF, use of donor human milk (DHM) in NICUs, or the effect of single family rooms on breastfeeding. Many pointed to disparities that disadvantage black infants.

Researchers for 3 articles9,21,38 studied disparities in BMF at discharge. Lee et al21 found that California BMF rates were highest for white, lower for Hispanic, and lowest for black infants. After separating NICUs by quartile percentage of each race, Lee et al21 found that BMF rates were higher for all races and ethnicities in hospitals with more white mothers. When units were compared, black infants benefited the most by being cared for in NICUs with a higher proportion of white infants. Lee et al’s21 findings are consistent with those of Profit et al,9 who include BMF within a composite NICU quality measure, finding that white infants scored higher than other racial and/or ethnic groups on BMF at discharge across NICUs. Riley et al38 studied the effect of neighborhood structural factors on BMF at NICU discharge for VLBW infants, finding that these did not significantly impact BMF, but that maternal race and/or ethnicity predicted BMF at discharge such that black race was associated with reduced likelihood of BMF at discharge. They also found that unlike white mothers, there was a trend of decreased BMF at discharge for black mothers without access to a car.

Researchers for 2 articles explored factors important for BMF in the NICU, in particular for black mothers. Using qualitative research, Cricco-Lizza22 found that black non-Hispanic mothers reported receiving limited breastfeeding education and support during pregnancy, childbirth, NICU stays, postpartum, and recovery in the community. Fleurant et al23 looked at the association of social factors (eg, breastfeeding support, etc) with human milk feeding at discharge. They found that the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program enrollment negatively predicted (and maternal goal setting near time of discharge positively predicted) BMF at discharge for mothers of all races and ethnicities. Surprisingly, they found that perceived breastfeeding support from an infant’s maternal grandmother negatively predicted BMF at discharge for black mothers.

Researchers for 2 studies incorporated the use of DHM as a measure of quality, either seeking to identify reasons associated with nonconsent for DHM24 or in assessing whether demographic disparities exist in the use of mother’s own milk and DHM.25 Brownell et al24 found that nonwhite race was among the predictors of nonconsent for DHM, and Boundy et al25 found that NICUs in postal codes with low percentages of black residents had higher rates of mother’s own milk use and of donor milk use.

Vohr et al26 compared infants cared for in single family room NICUs to those cared for in open bay NICUs. They found that, overall, infants benefitted from single family rooms through higher rates and volume of breast milk use and higher cognitive and language scores, but nonwhite race was associated with a decreased effect of this benefit.

High-risk Infant Follow-up Referrals

Researchers for 2 articles focused on disparities in referrals for follow-up care in infants with VLBW cared for in NICUs,27,28 showing disadvantages for black infants. We included these investigations because referrals to follow-up care should be initiated in the NICU and reflect the highest quality of care. Barfield et al27 found that early intervention referrals were lower for infants of black mothers. Similarly, Hintz et al28 found that black and Hispanic infants were less likely to be referred for high-risk follow-up than white infants.

Parental Satisfaction and Family Experience

Researchers for 2 recent studies documented disparities in parental satisfaction or how families experience NICU care,29,30 suggesting that families of color may be vulnerable to worse care. Martin et al29 surveyed white and black families on their experiences and satisfaction with NICU care and found that black families were most dissatisfied with nursing support, lack of compassionate and respectful communication, and less attentive care of their infants, whereas white parents were most dissatisfied with inconsistent nursing care and lack of informative exchanges, wanting education about their infants’ short- and long-term needs.

Sigurdson et al30 reported on accounts of disparate care from providers and parent advocates via open-ended survey. Accounts described disparities related to overlapping factors (language, culture or ethnicity, race, immigration status or nationality, sexual orientation or family status, gender, or disability) with race and ethnicity being an important dimension. The authors identified 3 types of disparate care: neglectful care, judgmental care, or systemic barriers to care, all reflecting suboptimal family-centered care.

Joint Parent-Provider Decision-making

Researchers for 2 articles addressed racial and/or ethnic differences in decision-making.31,32 Van McCrary et al31 reported on 2 cases where care decisions were influenced by social and cultural factors that were misunderstood by NICU medical staff and families. They offered 2 examples of families who wished for aggressive treatment when the staff felt the care plan was not appropriate given the burdens of treatment combined with dire prognosis.

Tucker Edmonds et al32 studied racial and/or ethnic differences in use of intubation for periviable infants, finding black race and/or ethnicity to be significantly associated with increased neonatal intubation.

Kangaroo Care

Hendricks-Muñoz et al’s33 survey of neonatal nurses and NICU mothers revealed that mothers valued kangaroo care higher than nurses. In addition, more mothers of color reported being discouraged from kangaroo care than white mothers. Among nurse respondents, nurses of color and foreign-born nurses were more likely to encourage maternal care partnerships and kangaroo care.

Surfactant and Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Researchers for 2 studies examined racial and/or ethnic disparities in outcomes for infants with VLBW after the introduction of surfactant therapy. Hamvas et al34 found that after surfactant therapy for respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) became generally available, neonatal mortality improved more for white than black infants, but these differences were explained by the higher prevalence of RDS among white infants. Ranganathan et al35 reported similar results and hypothesized differential efficacy of surfactant on non-Hispanic white and African American infants owing to more rapid lung maturation and surfactant production among African American fetuses.

The authors of 1 article looked specifically at the disparity in mortality due to RDS between black and white infants. Frisbie et al36 discovered that disparity increased in the years after surfactant was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, indicating that this new therapy benefitted white infants with RDS more than black infants with RDS. According to this study, black infants had a relative RDS survival advantage in the presurfactant era and a survival disadvantage after the introduction of surfactant.

In 1 article, researchers explicitly investigated disparities in the administration of surfactant itself. In 2010, in 3 New York hospitals, Howell et al37 found that clinicians were falling short of recommendations for surfactant overall, but white infants were more likely to get surfactant treatment than their black or Hispanic and Latino counterparts. However, when Hamvas et al34 looked at the same question, they did not find racial and/or ethnic disparities in surfactant use.

Outcomes

We identified 11 articles that examined racial and/or ethnic disparities in outcomes potentially due to differences in quality of care delivery (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Systematic Review Outcome

| Variable, Author, and Reference | Demographics of Study (If Available) | Outcome(s) of Interest | Summary of Main Findings | RR or Measures of Effect (If Applicable) | Suggested Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVH | |||||

| Qureshi et al39 | 3249 neonates and infants with IVH-related mortalities. | IVH-related mortality. | Incidence rates of IVH were higher among African-American infants than white infants. African American infants had a twofold higher risk of IVH mortality compared with white infants. Significant increase in incidence over the study period for white but not African American infants. | RR of IVH mortality for African American infants compared with white: 2.0. | Higher prevalence of respiratory diseases, LBWs, and preterm deliveries for African American infants. Pathophysiological characteristics that may predispose African American infants to IVH may also exist. |

| NEC and/or intestinal failure | |||||

| Guner et al40 | 3328 infants with NEC. | Factors that predict NEC-related outcome disparities. | Overall mortality for infants with NEC was 12.5%. Male and Hispanic infants less likely to survive. Black and white infants have similar survival rates. | Odds ratio of mortality for Hispanic compared with others: 1.44 (after adjustment for BW). | None |

| Squires et al41 | 272 infants (<12 mo) receiving parenteral nutrition for 60+ d. | Survival with intestinal failure and likelihood of receiving an ITx. | Children of color more likely to die without ITx and less likely to receive ITx by 48 mo after criteria met. | CIP for death without ITx: white: 0.16, nonwhite: 0.40. CIP for ITx: white: 0.31, nonwhite: 0.07. | Lower rates of breast feeding and higher rates of bloodstream infections among black infants could contribute, but the data used here did not show significant differences in human milk exposure or sepsis. |

| Overall morbidity or mortality | |||||

| Jacob et al42 | 137 Native and 469 non-Native infants with LBW. | BW-specific differences in neonatal morbidities for Alaska Natives compared with non-Natives. | More NEC, more severe ROP, and more BPD among Native infants compared with non-Native. For infants 1500–2499 g that needed ventilatory assistance, there was more IVH overall, more severe IVH, and more acquired sepsis among Native infants. | All study infants, Native versus non-Native - NEC: 13% vs 4.9%, ROP: 12% vs 4.6%, BPD: 49% vs 34%. Infants 1500–2499 g with ventilatory assistance, Native vs non-Native - IVH: 19% vs 7.4%, severe IVH: 9.5% vs 0.9%, sepsis: 7.1% vs 1.7%. | Differences may be due to differences in access to Level III perinatal care and intrapartum care. |

| Pont and Carter43 | 138 infants <750 g who died within first 24 h of life. | Characteristics of E-ELBW-NS. | More black and Hispanic E-ELBW-NS in 2000–2005 compared with 1995–1999; increase in black infants was not mirrored by total NICU admissions or NICU admissions <750 g. | Black E-ELBW-NS from first to second epoch: 14.0% to 38.8%; Hispanic: 1.8% to 4.9%; white: 84.2% to 54.3%. | May be due to confounding variables (such as maternal chorioamnionitis) that this sample size was too small to determine; there are known disparities in overall IMR. |

| Townsel et al44 | 4802 Level III NICU admits, GA <37 wk. | IHM, RDS, IVH, NEC, and ROP, compared by race and/or ethnicity. | No overall differences in IHM. For very preterm infants (<28 wk GA), black infants had lower IHM than white infants. Compared with white infants after risk-adjustment, black and multiracial infants had lower risk of RDS, Hispanic infants had higher risk, and multiracial infants had lower risk of ROP. | ROP, Hispanic versus white: aOR = 1.70. ROP, multiracial versus white: aOR = 0.45. RDS, black versus white: aOR = 0.57. RDS, multiracial versus white: aOR = 0.67. IHM, black versus white: unadjusted OR = 0.74. | Differences in retinal pigmentation may be protective against ROP for multiracial infants, especially if the infants in this sample have a higher concentration of African ancestry. |

| Other | |||||

| Collins et al45 | 3 684 569 NHW and 782 452 African American term infants. | IMR due to CHD. | IMR due to CHD was higher for African American than non-Hispanic white infants. Disparity was even greater in the postneonatal period. | RR of first year mortality, African American versus non-Hispanic white mothers = 1.36. Postneonatal period RR = 1.53, neonatal = 1.20 (not significantly different). | Individual level risk factors (eg, greater exposure to stressors and/or toxins or lack of access to quality health care due to living in an impoverished area in African American population) may explain PNMR disparity; however, adjusting for maternal demographic risk only minimally weakens the association. |

| Shin et al46 | 5165 infants with spina bifida. | Survival with spina bifida at 1, 5, and 20 y. | Significant improvement in 1-y survival between 1983 and 2002 for white and Hispanic infants but not black infants. Survival probability highest for white, then Hispanic, then black infants. Survival for black infants worse than white infants of normal birth wt, worse for Hispanic than white infants with LBW. | Change in 1-y survival, 1983–2002: white infants: 87.9%–95.9%; Hispanic infants: 88.3%–92.6%; black infants: 79.1%–87.5% (trend not statistically significant); normal BW mortality for black versus white, aHR at 1 y = 2.1, at 8 y = 1.9; LBW mortality for Hispanic versus white infants: 4.2, aHR at 1 mo = 6.0, at 1 y = 4.2, at 8 y = 3.7. | Possibly barriers in access to quality health care. |

| Oyetunji et al47 | 827 neonates | ECMO outcomes | Ethnic minorities were overrepresented in ECMO population, but race and/or ethnicity was not a major independent predictor of mortality on ECMO; rates of ECMO use among African American and Hispanic infants has increased faster than the increase in population, whereas ECMO among white infants has decreased. | RR not reported. | More ethnic minority infants have severe diagnoses that require ECMO; may be due to lower SES and resulting inadequate prenatal care. |

| Morris et al48 | 2446 ELBW infants | Rehospitalization before 18 mo corrected age (age from expected due date) and causes of rehospitalization. | Race was not a significant predictor for rehospitalization overall. White infants were more likely to be rehospitalized for growth and nutrition than black infants. | OR of rehospitalization for growth and nutrition for white versus black infants: 2.2. | Difference in parental expectations for growth; physician bias in referral for rehospitalization. |

| Collaco et al49 | 135 patients with chronic lung disease of prematurity. | Risk factors for use of major therapies (we did not include findings on respiratory morbidities because they were long-term outcomes). | No racial or ethnic disparity found in major treatment decisions (prescription of home oxygen, gastrostomy tubes, or initial length of stay). | N/A | Disease severity may outweigh any other factors; disparities may be subtle; confounding factors may reduce effects of racial and/or ethnic factors. |

“African American” and “black” are often used interchangeably in the literature reviewed. In this table, we use the same language as the articles cited. aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; BW, birth weight; CHD, congenital heart disease; CIP, cumulative incidence probability; E-ELBW-NS, early extremely low birth weight nonsurvivors; IHM, in-hospital mortality; IMR, infant mortality rate; ITx, intestinal transplant; LBW, low birth weight; N/A, not available; PNMR, perinatal mortality rate; RR, relative risk; SES, socioeconomic status.

Intraventricular Hemorrhage

One article39 examined intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)-related mortality, finding that black infants had a twofold greater risk of IVH-related mortality compared with white infants, positing a pathophysiological predisposition in black infants to IVH.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Intestinal Failure

Two articles were focused on conditions of the gastrointestinal tract: necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)40 and survival with intestinal failure.41 Both revealed disparity that disadvantaged infants of color. Guner et al40 noted that Hispanic infants with NEC were less likely to survive than non-Hispanic infants, but black and white infants with NEC had similar survival rates. Analyzing data on infants who received parenteral nutrition for >60 days, Squires et al41 found that infants of color were less likely to receive intestinal transplant by 48 months after the criteria for transplant was met and were more likely to die without transplants.

Overall Morbidity or Mortality

Three articles were focused on overall morbidity or mortality, revealing contradictory trends. In 2 articles,42,43 the researchers indicated a disadvantage for infants of color. Jacob et al42 found that Alaskan Native infants had higher rates of NEC, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and chronic lung disease compared with non-Native infants. Pont and Carter43 found a significant disparity in mortality among extremely low birth weight infants (<750 g) who died within the first 24 hours after birth. When comparing 2 different time periods, 1995–1999 and 2000–2005, Pont and Carter43 noted that black and Hispanic mortality increased, whereas the rate among white infants decreased. However, Townsel et al44 noted that among very preterm infants (<28 weeks’ gestational age [GA]), black infants had lower in-hospital mortality than white infants. Black and multiracial infants also had lower risk of RDS, and multiracial infants had a lower risk of ROP.

Other Specific Outcomes

Of the 5 articles in this category, 2 revealed a disparity that advantaged white infants over infants of other racial and ethnic groups, and 3 revealed race and/or ethnicity to not be predictive of poor outcomes. Collins et al45 found that infant mortality due to congenital heart disease was higher for African American than non-Hispanic white infants, and Shin et al46 noted significant improvement from 1983 to 2002 in 1-year survival rates for white and Hispanic patients with spina bifida but not for black infants. Oyetunji et al,47 however, found that race or ethnicity was not an independent predictor of mortality for infants on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Similarly, Morris et al48 noted that race was not a significant predictor of rehospitalization for extremely low birth weight. In addition, Collaco et al49 examined whether disparities in care existed for major NICU therapy decisions, finding that race and/or ethnicity did not affect the prescription of gastrostomy tubes, supplemental oxygen, or length of initial stay in the NICU.

Discussion

In this review, we provide a comprehensive summary of the literature in this area and suggest that disparities in NICU quality of care exist at all levels (structure, process, outcome) and generally disadvantage infants of color, with some areas of exception.14,19,34,35,44 Two primary themes driving these disparities emerged. First, infants of color, especially black and Hispanic infants, are more likely to receive care in quality-challenged hospitals. Second, disparities also exist within NICUs. Although some overlap exists, strategies to address disparities may differ.

The theme of worse care in minority-serving hospitals recurs throughout this review.* Although these findings could be secondary to other confounders such as socioeconomic differences in influencing disparate outcomes,39–43,45,46 we also found racial and/or ethnic disparities across processes9,21,22,24,27–31,33,37 that disadvantage infants of color. This indicates that disparities may be under the control of providers and amenable to improvement by using available QI tools. Minority-serving hospitals are often underresourced, may lack hospital or system-wide QI infrastructure, and uncommonly participate in collaborative QI efforts as offered, for example, through the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative50,51 or the Vermont Oxford Network.52 These organizations have a role to play in organizing and testing such efforts, potentially in partnership and funding from governmental agencies at the federal and state level. Lion and Raphael53 suggest that an ideal QI initiative would have an amplified effect on the populations experiencing worse quality and would engage community resources such as frontline providers and community members committed to improving the care of disadvantaged populations. We believe that efforts to specifically target improvement among the most challenged hospitals that serve affected communities hold promise for reducing disparity.54

Strategies for addressing within NICU disparities may require the development of new measures. Many key aspects of NICU care quality are currently not systematically measured but are nonetheless important. For example, family-centered care is not currently routinely measured and systematized across statewide or nationwide NICU data repositories. We are currently developing measures for family-centered care in the NICU that can be standardized across NICUs that are meaningful to consulted minority families and we hope to be sensitive to disparities.30 We hope these efforts will open up new paths for improvement in family experience and quality of care for all families, much in the same way as recent efforts in assessing and improving maternity care have done.55

The term “disparities” is used throughout this article; however, we suggest that this terminology risks naturalizing racial and/or ethnic differences rather than provoking action. That is, identifying racial disparities runs the risk of reinforcing the status quo56,57 and may lead to seeing differences as “natural” and not amenable to change. For instance, differences can be naturalized through racially biased preconceptions about cultural behaviors51 or biological causes and their impact on health disparities.51

This review should be viewed in light of its design. It may be that some relevant articles were omitted due to lack of full-text availability, unavailability of publication in the English language, or items not available through our search sources. However, articles retrieved in our study are a representative sample of literature in this field that would be readily accessible to most NICU health care practitioners. Additionally, research has been published in this area since the time of our search.58–62 Due to study heterogeneity, meta-analysis of data was not possible. Our definition of measurement of quality of care has relied on input from experts in our previous research.8 Although we use this framework explicitly for this review, it is important to understand that disparities in care and outcomes may overlap with biologic and socioeconomic factors that may be difficult to untangle.3 We do not address these important issues in our review. However, there is ample evidence that racial and ethnic minorities have disadvantages across the spectrum of factors identified as representing quality of NICU care. These disadvantages are multifactorial but find expression not just across populations but also in undue variation across hospitals. We are currently developing a dashboard to track NICU performance over time by racial and/or ethnic disparities to serve and inform accountable care organizations in improving population health and achieving health equity.

Gaps remain in the research. Although a history of institutional racism helps explain why racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be cared for in worse quality NICUs, what are the contemporary mechanisms that continue to stratify infants into different care settings? Although interpersonal racism can explain some within-NICU variation, particularly in process of care measures (eg, racially biased bedside practices, clinician attitudes), how do differences in processes translate into worse outcomes? We believe that this research requires both quantitative and qualitative approaches designed to generate hypotheses and test solutions and should involve affected communities as advisors or partners.53

Conclusions

In this review of racial and ethnic disparities in NICU quality of care, we suggest that disparities in neonatal outcomes are partly consequences of differential quality of care or access to high-quality care. That is, NICUs are not isolated from racism and disparities in infant outcomes “increasingly reflect the interaction between social forces and technical innovation.”63 Researchers are now looking at chronic stress caused by societal, institutional, or interpersonal racism as causal factors for preterm birth,64,65 and in this review, we suggest that these factors are also causal factors for racial and ethnic disparities in NICU quality of care. Targeted QI efforts hold promise for improving racial and ethnic equity in care delivery.

Glossary

- BMF

breast milk feeding

- DHM

donor human milk

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- GA

gestational age

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- NEC

necrotizing enterocolitis

- QI

quality improvement

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- VLBW

very low birth weight

- WIC

Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

Footnotes

Dr Sigurdson conceptualized and designed the study, ran the search strategy, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; Ms Mitchell conceptualized and designed the study, ran the search strategy, assisted in drafting the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; Dr Liu assisted in drafting the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript; Drs Morton, Gould, and Lee assisted in running the search strategy and revised the manuscript; Ms Capdarest-Arest designed the search strategy, assisted in drafting the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; Dr Profit conceptualized and designed the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Drs Sigurdson, Morton, and Profit and Ms Mitchell are supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD083368-01, principle investigator: Dr Profit). Dr Sigurdson is also supported by a postdoctoral support award from the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.March of Dimes 2018 Premature Birth Report Card. Available at: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/tools/reportcard.aspx. Accessed June 14, 2019

- 2.Riddell CA, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Trends in differences in us mortality rates between black and white infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):911–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorch SA. Health equity and quality of care assessment: a continuing challenge. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassett MJ, Schymura MJ, Chen K, Boscoe FP, Gesten FC, Schrag D. Variation in breast cancer care quality in New York and California based on race/ethnicity and Medicaid enrollment. Cancer. 2016;122(3):420–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong L, Fakeye OA, Graham G, Gaskin DJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in quality of care for cardiovascular disease in ambulatory settings: a review. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;75(3):263–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Profit J, Kowalkowski MA, Zupancic JA, et al. Baby-MONITOR: a composite indicator of NICU quality. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):74–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lake ET, Staiger D, Horbar J, Kenny MJ, Patrick T, Rogowski JA. Disparities in perinatal quality outcomes for very low birth weight infants in neonatal intensive care. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(2):374–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lake ET, Staiger D, Edwards EM, Smith JG, Rogowski JA. Nursing care disparities in neonatal intensive care units. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(suppl 1):3007–3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bronstein JM, Capilouto E, Carlo WA, Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL. Access to neonatal intensive care for low-birthweight infants: the role of maternal characteristics. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(3):357–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould JB, Sarnoff R, Liu H, Bell DR, Chavez G. Very low birth weight births at non-NICU hospitals: the role of sociodemographic, perinatal, and geographic factors. J Perinatol. 1999;19(3):197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gortmaker S, Sobol A, Clark C, Walker DK, Geronimus A. The survival of very low-birth weight infants by level of hospital of birth: a population study of perinatal systems in four states. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152(5):517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert PL, Chassin MR, Howell EA. The contribution of geography to black/white differences in the use of low neonatal mortality hospitals in New York City. Med Care. 2011;49(2):200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Featherstone P, Eberth JM, Nitcheva D, Liu J. Geographic accessibility to health services and neonatal mortality among very-low birthweight infants in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(11):2382–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales LS, Staiger D, Horbar JD, et al. Mortality among very low-birthweight infants in hospitals serving minority populations. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2206–2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/3/e407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kugler JP, Connell FA, Henley CE. Lack of difference in neonatal mortality between blacks and whites served by the same medical care system. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(3):281–287; discussion 287–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell EA, Janevic T, Hebert PL, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J. Differences in morbidity and mortality rates in black, white, and Hispanic very preterm infants among New York city hospitals. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(3):269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HC, Gould JB, Martin-Anderson S, Dudley RA. Breast-milk feeding of very low birth weight infants as a function of hospital demographics. J Perinatol. 2011;31:S82–S82 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cricco-Lizza R. Black non-Hispanic mothers’ perceptions about the promotion of infant-feeding methods by nurses and physicians. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(2):173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleurant E, Schoeny M, Hoban R, et al. Barriers to human milk feeding at discharge of very-low-birth-weight infants: maternal goal setting as a key social factor. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12:20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brownell EA, Smith KC, Cornell EL, et al. Five-year secular trends and predictors of nonconsent to receive donor milk in the neonatal intensive care unit. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(6):281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boundy EO, Perrine CG, Nelson JM, Hamner HC. Disparities in hospital-reported breast milk use in neonatal intensive care units - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(48):1313–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]