Abstract

This study compared the topological organization of brain function in never-treated and treated long-term schizophrenia patients. In a cross-sectional study, 21 never-treated schizophrenia patients with illness duration over 5 years, 26 illness duration-matched antipsychotic-treated patients and 24 demographically-matched healthy controls underwent a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The topological properties of brain functional networks were compared across groups, and then we tested for differential age-related effects in regions with significant group differences. Both never-treated and antipsychotic-treated schizophrenia patient groups showed altered nodal centralities in left pre-/postcentral gyri relative to controls. Never-treated patients demonstrated reduced global efficacy, decreased nodal centralities in right amygdala/hippocampus and bilateral putamen/caudate relative to antipsychotic-treated patients and controls. No significant relationships of age and altered functional metrics were seen in either patient group, and no alterations were greater in the treated group. These findings provide insight into brain function deficits over the longer-term course of schizophrenia independent from potential effects of antipsychotic medication. The presence of greater alterations in never-treated than treated patients suggests that long-term antipsychotic treatment may partially protect or enhance brain global and nodal topological function over the course of schizophrenia, notably involving the amygdala, hippocampus, and striatum that have long been associated with the disorder.

Subject terms: Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Identifying the trajectory of brain changes associated with schizophrenia and the impact of long-term antipsychotic treatment on brain anatomy and function are crucial challenges for schizophrenia research. Kraepelin’s description of schizophrenia as a deteriorating disease [1] has received support from longitudinal structural neuroimaging studies that have shown gray matter decreases in frontal cortex, thalamus, and total brain volume after illness onset [2–4]. However, the timing and specific nature of these effects over the longer-term course of illness, and the degree to which they are secondary to antipsychotic treatment or reduced by such treatment remain unclear [5, 6].

Most psychoradiology (https://radiopaedia.org/articles/psychoradiology) [7] studies of illness course effects have focused on brain structure rather than function [8–12]. Cross-sectional functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have reported distinct functional changes in different stages of schizophrenia, involving the frontal lobe (particularly the inferior frontal gyrus) during the early years of illness, and more pronounced disruptions in frontothalamic and thalamo-sensorimotor networks in the later course of illness [13]; however, few studies have investigated longitudinal functional changes directly.

Short-term longitudinal studies conducted to identify treatment effects on brain function have identified robust impact of antipsychotic medications on brain function, including complex patterns of functional connectivity change with increased function in the dorsal attention network and reduced function in dorsolateral frontal cortex which can persist for a year after first treatment [14–16]. While such studies of first-episode patients have been informative, their relatively short duration of follow-up and challenges of patient attrition leaves questions about longer-term illness-related changes in brain function unanswered. In addition, using conventional follow-up strategies, it is difficult to separate influences of illness course and treatment because nearly all patients are treated with antipsychotic medication with dosage related to illness severity.

In this context, and with the inability to conduct long-term placebo-controlled studies to examine course of illness effects without influences of antipsychotic medications for ethical reasons, cross-sectional studies comparing duration-matched never-treated and treated long-term schizophrenia patients may provide novel insights into progression and treatment effects over the longer-term course of illness. Importantly, such studies can clarify long-term effects of illness on functional brain networks without influence of antipsychotic medications, and their comparison with treated patients can be informative about effects of long-term treatment on brain function. Although a cross-sectional study has limitations, such a study can provide information on important issues related to course of illness and effects of long-term antipsychotic medication treatment which is not otherwise available.

In previous studies of never-treated long-term schizophrenia patients which overlapped with the present sample, widespread structural changes were demonstrated in the later course of schizophrenia in never-treated patients, including cortical thickness deficits in prefrontal, temporal and parietal cortex, and white matter tract alterations predominantly in pathways of frontal cortex [11, 12]. We also reported an accelerated age-related decline in prefrontal and temporal cortical thickness [12], and greater age-related reduction of fractional anisotropy in rostral corpus callosum in never-treated patients relative to controls and treated patients [11].

Graph theoretical analysis can provide a powerful framework for characterizing topological properties of brain networks. This connectomic approach considers the whole brain as an interconnected network [17, 18]. The disruption of fundamental organizational properties, including small worldness and nodal centrality have been observed in schizophrenia patients [19]. However, there has not yet been a study of functional brain systems using this approach in never-treated chronically ill schizophrenia patients.

Here, we employed resting-state fMRI in never-treated chronic schizophrenia patients (n = 21), duration of illness matched antipsychotic-treated patients (n = 26) and healthy individuals (n = 24) using a graph theory approach for evaluating the functional brain connectome. We compared graph theory metrics between groups to identify alterations in patients with long-term illness who have not received long-term antipsychotic treatment relative to treated patients and healthy controls, and we further tested for differential age-related effects across groups. We hypothesized that more severe topological global and nodal deficits would be revealed by the graph theoretical analysis in the never-treated long-term schizophrenia patients compared to treated patients, and the age-related decline in function network changes would be accelerated in never-treated patients relative to treated patients and healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty-one never-treated schizophrenia patients and 26 illness duration (ranging from 5 to 37 years) and age-of-onset matched chronic schizophrenia patients who had received long-term antipsychotic treatment and 24 matched healthy controls were recruited (Table 1). The diagnosis of schizophrenia was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Illness onset was determined using the Nottingham Onset Schedule [20] using information provided by patients, family members, and medical records. Symptoms of psychosis at the time of scans were evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which were more severe in the never-treated than treated schizophrenia patients (Table 1 and Table S1). This study was approved by the university research ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to study participation.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of never-medicated long-term schizophrenia patients, antipsychotic-treated long-term schizophrenia patients, and healthy controls

| Characteristics | Never-medicated schizophrenia patients (N = 21) | Antipsychotic-treated schizophrenia patients (N = 26) | Healthy controls (N = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p value | |

| Age (years) | 45.57 ± 12.04 | 47.50 ± 6.81 | 47.42 ± 13.23 | 0.80 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 16.77 ± 11.08 | 17.62 ± 9.90 | 0.78 | |

| Age at onset (years) | 28.80 ± 8.89 | 29.88 ± 9.38 | 0.69 | |

| PANSS total scores | 92.80 ± 21.13 | 51.23 ± 11.67 | <0.001 | |

| Milligrams per day of chlorpromazine equivalents | 421.49 ± 299.67 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.73 | ||||||

| Female | 12 | 57 | 12 | 46 | 13 | 54 | |

| Male | 9 | 43 | 14 | 54 | 11 | 46 |

PANSS positive and negative syndrome scale, SD standard deviation

Never-treated patients were identified by a regional Mental Health Screening Program designed to identify and then provide psychiatric care to individuals with serious but untreated mental illness. These patients, most in their 40’s or older, were typically located within 35 km of downtown Chengdu, a large city in western China. Fifteen lived in rural areas, mostly in small villages on the outskirts of Chengdu; the others were living in urban or suburban areas. Based on available retrospective information, symptom onset was gradual and insidious for 14 patients, while the other seven developed acute psychosis associated with significant life trauma. Twelve had no prior employment and nine were able to care for themselves in most activities of daily living. Family members worked mainly as manual laborers and farmers. Most patients and their family members had 9 years of education, including 6 years in primary school and 3 years in junior high school, as was common in China when they were in school.

The never-treated patients had not received prior psychiatric treatment for various reasons, primarily because of parental concern about family stigma (prominent in 11 cases); a lack of family understanding of the severity of the mental illness (noteworthy in five cases); poor socioeconomic conditions that limited travel and funds for medical care (two cases); and conflicts with physicians when the patient was first brought to medical attention near the time of illness onset (three cases). Each patient had been cared for and sheltered in their parents’ home without medical care through the course of their illness.

The treated patient group was recruited from the same community. Based on patient report and medical records, they received antipsychotic treatment relatively consistently beginning early in their course of illness. Because of the long history of treatment by different providers, details of antipsychotic drug treatment for each treated patient are not available, but we estimated typical daily medication dosages over the most recent 10 years (or since onset if a briefer time) using all available data (Table 1).

Healthy controls were recruited from the local area by poster advertisement and screened using the nonpatient version of the SCID to rule out lifetime psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders. They had no known history of psychiatric illness in first-degree relatives. The following exclusion criteria applied to all participants: (1) the existence of a neurological disorder or other psychiatric disorders; (2) alcohol or substance abuse disorder (DSM-IV); (3) pregnancy; (4) chronic physical illness such as brain injury, hepatitis, or epilepsy, as assessed by clinical evaluations and medical records.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

Subjects were scanned using a 3-T MRI system (EXCITE; General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Magnetic resonance images sensitized to changes in blood oxygenation level dependent signal levels (repetition time = 2000 ms; echo time = 30 ms; flip angle = 90°) were obtained with a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence with a slice thickness of 5 mm (no slice gap), 64 × 64 matrix size, and a field of view of 240 × 240 mm2, resulting in a voxel size of 3.75 × 3.75 × 5 mm3. Each brain volume comprised 30 axial slices and each functional run contained 200 image volumes. During functional scanning, subjects were instructed to relax with eyes closed, without falling asleep and without directed, systematic thought. Additional T1 and T2-weighted scans were collected and examined by a neuroradiologist to rule out gross brain abnormalities for all participants.

Functional image preprocessing was carried out using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Images were slice-time-corrected, aligned to the middle volume, and realigned to the middle image. After that, functional images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute template, and each voxel was resampled to 3 × 3 × 3 mm3. Then the resulting data were temporally bandpass filtered (0.01–0.08 Hz) to reduce the effects of low-frequency drift and high-frequency physiological noise. Finally, we utilized the Friston 24-parameter model [21] to regress out head motion effects from the realigned data. White matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals were removed to restrict analysis to gray matter voxels.

The head translation movement of all participants was <1.5 mm, and rotation was <1.5°. No significant group differences were found in head translation or rotation. Mean framewise displacement was used as a nuisance covariate in all analyses, which was derived with Jenkinson’s relative root mean square algorithm and considered voxel-wise differences in motion in its derivation [22].

Network construction and analysis

Graph theoretical analyses were carried out on functional connectivity networks of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls using GRETNA [23]. First, the atlas of Craddock (CC-200) [24] was used to parcel the brain into 200 cortical and subcortical functional regions of interest (ROI) (Figure S1), and each ROI was considered a network node. This atlas was generated based on spatially constrained clustering and is widely used in the analysis of brain function [25, 26]. Next, the mean time series was obtained in each ROI, and the correlation coefficients of the mean time series between each pair of ROIs were considered as initial edges of the network, whose association is assumed to reflect inter-regional functional connectivity strength. This process resulted in a 200 × 200 temporal correlation matrix for each subject. Networks were then pruned by dropping any edge (correlation) that did not meet nominal statistical significance (p < 0.05, uncorrected).

As brain networks of different people differ in the number of their significant edges [27], we used a wide range of cost thresholds that were applied to the correlation matrices in which each graph had the same number of edges. For each subject, cost was defined as the total number of edges (significant correlations) divided by the maximum possible number of edges in a graph [28]. Its minimum was set so that the average degree (the degree of a node is the number of edges linked to the node) of overall nodes of each thresholded network was 2 × log(N) [29]. The selected cost range was further adjusted to assure the largest component size of individual networks was larger than 88, and its maximum was set so that the small worldness of the thresholded networks was larger than 1.1 [29]. Based on the criteria above, the network analysis was repeatedly performed over a wide range of costs (0.14 ≤ cost ≤ 0.28), with steps of 0.01.

Network metrics

We calculated both global and regional measurements for brain functional networks at each cost threshold. The global network measurements included overall small worldness (σ), clustering coefficient (Cnet), characteristic shortest path length (Lnet), normalized clustering coefficient (γ), and normalized characteristic shortest path length (λ), as well as the global network efficiency (Eglobal). Regional measures for each node included nodal degree (Si), nodal efficiency (Ei), and nodal clustering coefficient (Ci) (for the interpretations of these network measures, see Supplemental Materials and Methods). The area under the curve (AUC) for each network metric across cost thresholds was calculated to provide an overall value for the topological characterization of brain networks for each individual independent of any single cost threshold selection. Computed in this way, the AUC metric has established sensitivity for detecting topological alterations in brain disorders [30].

Statistical analysis

To test for group differences in graph properties, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare AUC values among the three groups, with Bonferroni correction for the multiple comparisons of nodal measures among the three groups (number of brain metrics examined, n = 200), followed by pairwise post-hoc Fisher’s least significance difference (LSD) tests to determine which of the three groups differed significantly. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05. We also examined topological measures and performed the groups comparison using the atlas of Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL-90) [31] as a validation step (see Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Correlational analyses examined relationships of brain metrics that showed significant group differences with demographic and clinical variables including age and daily antipsychotic dose in chlorpromazine equivalents. An exploratory analysis of associations between age and regional measurements for all 200 nodes was also conducted (see Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Results

Altered topological properties of brain functional networks in never-treated and treated long-term schizophrenia patients

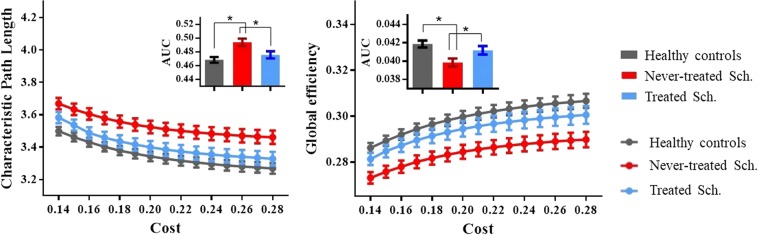

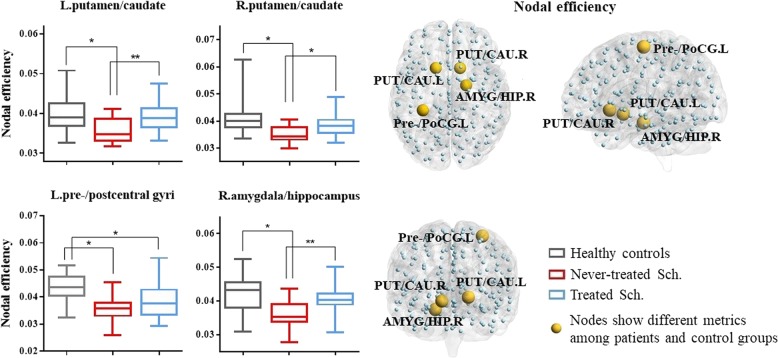

Both schizophrenia groups and healthy controls showed a small-world architecture (i.e., σå 1) at all connection densities. However, specific network organization characteristics for the three groups differed significantly, including global efficiency (Eglobal) and weight characteristic of the shortest path length (Lnet) (p < 0.05, uncorrected) (Fig. 1, Table 2). No significant group differences were found in the overall clustering coefficient (Cnet), normalized weight characteristic of the shortest path length (λ), and normalized clustering coefficient (γ). Nodal metrics for the three participant groups differed significantly including nodal efficiency in right amygdala extending to hippocampus, bilateral putamen extending to caudate, and left pre-/postcentral gyrus (p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected) (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Altered topologies of the Craddock (CC-200) brain functional networks. The characteristic path length (Lnet) and global efficiency (Eglobal) (left to right, respectively) of the functional networks of long-term ill never-treated schizophrenia patients, chronically treated schizophrenia patients, and healthy controls at each cost threshold (0.14–0.28, step = 0.01) are shown. The gray, blue, and red lines represent the healthy controls, treated schizophrenia patients, and never-treated schizophrenia patients respectively. The bars and error bars denote the mean value and standard error of mean (1000 iterations). The inset bar plots indicate the AUC for each topological measure. Bar and error bars = mean and standard error of mean. AUC area under the curve, Sch. schizophrenia patients. *Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05

Table 2.

Brain topological metrics showing differences among never-treated long-term schizophrenia patients, antipsychotic-treated patients of similar illness duration, and healthy controls

| Post-hoc LSD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never-treated Sch. | Antipsychotic-treated Sch. | Controls | ANOVA | Controls versus never-treated Sch. | Controls versus antipsychotic-treated Sch. | Never-treated Sch. versus treated Sch. | |

| Measurements | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p (f) value | p (d) value | p (d) value | p (d) value |

| Global | |||||||

| Lnet | 0.494 ± 0.025 | 0.476 ± 0.027 | 0.468 ± 0.020 | 0.003* (0.397) | 0.001* (1.148) | 0.302 | 0.013* (0.692) |

| Eglobal | 0.040 ± 0.002 | 0.041 ± 0.002 | 0.042 ± 0.002 | 0.008* (0.364) | 0.002* (1.000) | 0.257 | 0.035* (0.500) |

| Nodal efficiency | |||||||

| R putamen/caudate | 0.035 ± 0.003 | 0.038 ± 0.004 | 0.041 ± 0.006 | <0.001# (0.473) | <0.001* (1.265) | 0.051 | 0.011* (0.849) |

| L putamen/caudate | 0.035 ± 0.003 | 0.039 ± 0.003 | 0.040 ± 0.005 | <0.001# (0.469) | <0.001* (1.213) | 0.185 | 0.003** (1.333) |

| R amygdala/hippocampus | 0.036 ± 0.004 | 0.041 ± 0.004 | 0.042 ± 0.006 | <0.001# (0.463) | <0.001* (1.177) | 0.319 | 0.001** (1.250) |

| L pre-/postcentral gyri | 0.036 ± 0.005 | 0.038 ± 0.006 | 0.043 ± 0.005 | <0.001# (0.476) | <0.001* (1.400) | 0.004* (0.905) | 0.127 |

Lnet characteristic shortest path length, Eglobal global network efficiency, Sch. schizophrenia patients, ANOVA analysis of variance, LSD least significance difference, SD standard deviation, d Cohen’s d, f Cohen’s f, L left, R right

*Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05

**Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05 after correcting for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score

#Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction (n = 90)

Fig. 2.

Nodes showing altered nodal efficiency among never-treated schizophrenia patients, chronically treated schizophrenia patients, and healthy controls. The left column illustrates differences in nodal efficiency among healthy controls, treated schizophrenia patients, and never-treated schizophrenia patients. The box represents the 25–75th percentiles, the median is indicated by a bar across the box, the whiskers on each box represent the minimum and maximum values. The right column showed the nodes with altered nodal efficiency among the never-treated schizophrenia patients, chronically treated schizophrenia patients, and healthy controls. PUT putamen, CAU caudate, AMYG amygdala, HIP hippocampus, Pre-/PoCG pre-/postcentral gyri, Sch. schizophrenia patients, L left hemisphere, R right hemisphere. *Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05. **Significant difference of topological metrics between groups at p < 0.05 after correcting for Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score

Pairwise comparisons revealed greater abnormalities in global network properties, including greater reductions in Eglobal and increased Lnet in never-treated versus treated patients. The never-treated patients also showed lower nodal efficiency of bilateral putamen/caudate and right amygdala/hippocampus than treated patients. Both patient groups showed lower nodal efficiency of left pre-/postcentral gyri; only never-treated patients showed decreased nodal efficiency of bilateral putamen/caudate and right amygdala/hippocampus (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

As patient groups differed in acute symptom severity as well as treatment history, we repeated analyses after correcting pairwise comparisons for PANSS total scores. This is a conservative supplementary analysis, as it would tend to reduce group differences in MRI measures because of the large group difference in PANSS scores. Even in this analysis, the never-treated group still showed reduced nodal efficiency of left putamen/caudate and right amygdala/hippocampus compared to the treated group, but patient group differences in all global metrics and nodal efficiency of right putamen/caudate were no longer significant (Table 2).

Relationships between network metrics and psychopathology ratings

Within the never-treated schizophrenia group, both decreased Eglobal and increased Lnet relative to controls were associated with greater PANSS total scores (r = −0.49, p < 0.05; r = 0.54, p < 0.05). No significant correlation was found between network metrics and PANSS total scores in the treated schizophrenia group.

In a secondary analysis, the never-treated and treated patients were pooled together to assess relationships between network metrics and clinical symptoms in the combined group of schizophrenia patients. We also explored the relationships between all network metrics and PANSS factor scores (see Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Relationships of age and antipsychotic medication dose with functional network metrics

For each group, we examined the relationship between age and network parameters in which differences were seen among the three participant groups. Unlike our previous studies of gray and white matter structure, no significant age-related associations were observed using linear or quadric modeling in any group, and no differences of the regression coefficients were identified among groups. We also explored the linear associations between age and regional measurements for all 200 nodes, with results presented in Table S2; no significant group differences in age-associated brain changes were seen. In the treated schizophrenia patients, no significant correlation was observed between daily antipsychotic dose and network metrics which differed among groups.

Discussion

Psychoradiology, a field first proposed by Lui and Gong et al, allows the translational imaging investigations of the psychiatric disorders [7, 32–34]. By investigating a rare sample of long-term ill but never-treated schizophrenia patients and comparing them with duration-matched treated patients and healthy controls, we demonstrated similar functional alterations relative to controls across the two patient groups as well as greater global and nodal functional abnormalities in the never-treated patients. Using a small-world functional connectome model, we observed a shift toward regularization in global functional networks, and impaired nodal characteristics of putamen/caudate, amygdala/hippocampus, and pre-/postcentral gyri in schizophrenia groups. Direct comparison of the two schizophrenia groups showed greater nodal alterations in amygdala/hippocampus and putamen/caudate in the never-treated group, as well as global network changes, suggesting reductions in both functional segregation and integration. In contrast to our previous reports of increased age-related reductions in gray [12] and white matter [11] in this patient cohort, no differential age-related effects were seen across groups in brain function metrics.

These results provide novel insights about alterations of brain function in the later course of schizophrenia without the confounding influence of antipsychotic treatment. The less prominent reductions of function in treated patients suggest that long-term antipsychotic treatment may have a facilitative or neuroprotective effect on brain function over the longer-term course of illness, via direct and indirect mechanisms, most notably in subcortical structures long implicated in the illness [35, 36].

Analyses of nodal characteristics revealed regional changes in both never-treated and treated schizophrenia patients including decreased nodal centrality in right amygdala/hippocampus, bilateral putamen/caudate, and left pre-/postcentral gyri. These observations reinforce the view that deficits in amygdala and hippocampus are among the most robust abnormalities associated with schizophrenia [37] and may contribute to persistent problems in emotional and social functioning [38, 39]. The striatum is involved in regulating motor function, and recently, its importance in cognitive and mood functions have been emphasized [40–42]. Increased intrinsic activity of putamen was identified in a previous untreated first-episode schizophrenia study [43]. In the current study, using the nodal centrality metric, we found decreased connectivity with other brain regions at the whole-brain level. Our present findings are consistent with a recent paper which revealed reduced degree centrality and dysconnectivity of putamen in first-episode schizophrenia [44]. The pre- and postcentral gyri, which support sensorimotor functions, are impaired in schizophrenia [45–47]. Thus, our findings suggest that the abnormality of these regions may persist through midlife, with greater level of functional deficits seen in never-treated patients.

The less impaired functional topology of amygdala and putamen in our treated group is consistent with findings of previous short-term treatment studies [48, 49]. Structural MRI studies found increased gray matter volume in putamen after acute antipsychotic treatment [2, 50] and schizophrenia patients receiving atypical antipsychotics have shown normalized amygdala activation in task-based fMRI studies [48]. The amygdala and striatum receive rich dopaminergic projections. Decreased topological properties of the putamen have been linked to altered dopaminergic transmission, which in turn has been related to auditory hallucinations [51]. Antipsychotic drugs are well known to block D2 receptors in striatum and amygdala [52], and they can have neuroplastic effects on the brain, including increased synapse number and connections of striatum [53]. Numerous neurochemical studies have also provided robust evidence of the close link between dopamine receptor availability in striatum and the antipsychotic treatment efficacy [54, 55].

Our findings of greater deficits in never-treated than treated patients in subcortical nodes of the brain network suggests that long-term treatment may partially ameliorate these functional deficits in schizophrenia patients, and that without treatment these alterations may persist through the longer-term course of illness. The greater level of functional alterations in the treated patients might be related to direct pharmacological mechanisms, or various indirect pathways related to improved social interaction, diet, healthcare, etc.

By comparing medicated with never-treated schizophrenia patients with long-term illness, it was remarkable that nodal differences in brain function were mainly in subcortical nuclei and hippocampus. Patients who had not received long-term treatment showed more pronounced subcortical alterations but no differences with treated patients in nodal functional properties of sensorimotor cortex. While the effect of antipsychotic medication on precentral and postcentral gyri has been identified with both structural and functional studies [56, 57], the two schizophrenia groups did not differ in this regard with both groups showing deficits comparing to controls. This may be due to reduced antipsychotic treatment effects on sensorimotor cortex later in the course of illness, or to this being a variably enduring effect of antipsychotic treatment. This latter hypothesis is supported by a functional study which showed different effect patterns even within 8 weeks [58]. The absence of patient group differences in this region and other sensorimotor system areas where functional connectivity changes after acute treatment have been reported [59], suggests that the patient group differences we observed were not fully due to acute treatment effects, but persistent effects of illness. This is consistent with evidence of sensorimotor alterations in individuals at familial risk for schizophrenia, and their persistence over time in schizophrenia with only modest effect of longer-term antipsychotic treatment [60, 61].

Several structural and functional graph theory studies have reported inconsistent global topological findings after acute antipsychotic treatment in first-episode schizophrenia, including no changes, decrease in clustering, and increase in global efficiency [48, 62–64]. One functional study found global efficiency was decreased relative to controls before treatment but increased after 6 weeks of acute treatment [64]. This is consistent with the differences in findings in treated and untreated patients in the present study. Consistent with our results, several previous found evidence of no clustering changes in functional topology in medicated schizophrenia patients [65, 66].

To our knowledge, all previous graph theory studies of treatment effects have included schizophrenia patients with mean illness duration shorter than 11 years (more shorter than 2 years), and all had prior antipsychotic treatment history, which may explain differences in our findings comparing treated and untreated patients with those prior acute treatment studies. Treatment duration in most of these studies was less than 12 weeks, and this global topological metric may not be affected in the same way by acute and long-term antipsychotic treatment.

Our findings partially parallel to those from our previous diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and structural MRI studies of an overlapping group of never-treated long-term ill patients. In our DTI study, we found greater abnormalities in never-treated than treated patients in uncinate fasciculus fibers connecting amygdala and frontal cortex, and in the thalamic radiation to the putamen. In our structural study, we reported gray matter deficits in bilateral putamen [11, 12]. Thus, structural and functional changes in amygdala, striatum, and perhaps sensorimotor cortex may represent fundamental aspects of schizophrenia that endure over the illness course, persistent but partially ameliorated by long-term antipsychotic treatment.

While our previous studies suggested accelerated age-related changes in gray and white matter, age-related effects were not observed in the current study of the functional connectome. This may be due to our relatively small sample size, as aging effects on brain functional topology in midlife adults are not typically particularly consistent or robust [67, 68]. Another possibility is that accelerated age-related changes may be more robust in brain anatomy than brain function, perhaps because brain function may be more directly linked to short-term variations in neurophysiology while anatomic measures may reflect more stable long-term trends.

Several limitations in our study should be considered. Most important, while the data are novel and advance the understanding of neurobiology of schizophrenia without potential impact of pharmacotherapy in the later stage of illness, our study design is cross-sectional. Therefore, inferences about individual subject change over time and in relation to antipsychotic therapy need to be considered to be tentative. Further, our patient groups differed not only in treatment history but also in current symptom severity and current treatment. We note however that statistical control of acute symptoms did not eliminate our key findings regarding of nodal/regional connectivity. In terms of acute pharmacological treatment effects, differences between our schizophrenia groups diverge considerably from studies of acute antipsychotic treatment effects by not involving the large number of cortical nodes impacted by acute treatment [15]. Thus, the potential impact of symptom severity and acute drug effects on our findings need to be considered in interpreting our findings. Second, the brain functional differences between two groups and their relationship with treatment history are constrained by the lack of random assignment to long-term treatment versus no treatment conditions. Such a study is not feasible for ethical reasons, so that our cross-sectional approach may be the only viable strategy to study the long-term course of treated versus never-treated schizophrenia to evaluate illness course without treatment confounds and to gather information about long-term treatment effects on brain function. Nonetheless, this issue needs to be considered in data interpretation. Third, recruiting never-treated long-term schizophrenia patients is challenging, and as a consequence the sample size of our study is not large. Studies with larger samples may be required for further verification and subgroup identification. Fourth, like most resting-state fMRI studies, we cannot eliminate all effects of physiologic noise because we used a relatively low sampling rate (TR = 2 s) for multislice acquisition. Last, animal model studies are required to establish the neurobiological mechanisms of long-term antipsychotic effects on brain function to establish the mechanisms for functional brain differences in never-treated and treated patients.

Notwithstanding these limitations, by studying a rare sample of never-treated long-term ill schizophrenia patients, our findings provide novel insights into global and regional functional topological changes over longer-term course of schizophrenia without confounding effects of antipsychotic medication. Furthermore, the current findings of reduced nodal connectivity of amygdala and striatal areas in never-treated patients but not cortical differences relative to treated patients suggest that the benefits of long-term antipsychotic treatment may be of particular benefit to these brain region’s function over the course of illness.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by the National Key Research & Development Program of China (Grant no. 2016YFC1201700) and 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence (Project nos ZYYC08001, ZYJC18020) and its Clinical Research Incubation Project (Grant no. 2018HXFH035), West China Hospital, Sichuan University for WD, TL, and SL. QYG and SL currently receive National Natural Science Foundation (Grant nos 81220108013, 81761128023, 81227002, and 81030027; Grant nos 81671664, 81621003). SL currently receives funding from Chang Jiang Scholars (Award no. Q2015154) of China and National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals (National Program for Special Support of Eminent Professionals; Organization Department of the Communist Party of China Central Committee, Award no. W02070140). QYG was also supported by Program for Chang Jiang Scholars and the Innovative Research Team in Universities (PCSIRT, Grant no. IRT16R52) of China. FL currently receives funding from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2018SCUH0011); Science and Technology Project of the Health Planning Committee of Sichuan Province (18ZD035) and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2019YJ0098). The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and volunteers for participating in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-019-0428-2).

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia. New York, NY; Chicago: Chicago Medical Book Co. 1919.

- 2.Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:128–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Magnotta V, Pierson R, Ziebell S, Ho BC. Progressive brain change in schizophrenia: a prospective longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:672–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietsche B, Kircher T, Falkenberg I. Structural brain changes in schizophrenia at different stages of the illness: a selective review of longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51:500–08. doi: 10.1177/0004867417699473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephan KE, Magnotta VA, White T, Arndt S, Flaum M, O’Leary DS, et al. Effects of olanzapine on cerebellar functional connectivity in schizophrenia measured by fMRI during a simple motor task. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1065–78. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honey GD, Bullmore ET, Soni W, Varatheesan M, Williams SC, Sharma T. Differences in frontal cortical activation by a working memory task after substitution of risperidone for typical antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13432–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lui Su, Zhou Xiaohong Joe, Sweeney John A., Gong Qiyong. Psychoradiology: The Frontier of Neuroimaging in Psychiatry. Radiology. 2016;281(2):357–372. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cropley VL, Klauser P, Lenroot RK, Bruggemann J, Sundram S, Bousman C, et al. Accelerated gray and white matter deterioration with age in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:286–95. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vita A, De Peri L, Deste G, Sacchetti E. Progressive loss of cortical gray matter in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal MRI studies. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e190. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Y, Chen Y, Lee R, Bezerianos A, Collinson SL, Sim K. Disruption of brain anatomical networks in schizophrenia: a longitudinal, diffusion tensor imaging based study. Schizophr Res. 2016;171:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao Y, Sun H, Shi S, Jiang D, Tao B, Zhao Y, et al. White matter abnormalities in never-treated patients with long-term schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:appiajp201817121402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Deng W, Yao L, Xiao Y, Li F, Liu J, et al. Brain structural abnormalities in a group of never-medicated patients with long-term schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:995–1003. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14091108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T, Wang Q, Zhang J, Rolls ET, Yang W, Palaniyappan L, et al. Brain-wide analysis of functional connectivity in first-episode and chronic stages of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:436–48. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx024.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Lui S, Yao L, Hu J, Lv P, Huang X, et al. Longitudinal changes in resting-state cerebral activity in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up functional MR imaging study. Radiology. 2016;279:867–75. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lui S, Li T, Deng W, Jiang L, Wu Q, Tang H, et al. Short-term effects of antipsychotic treatment on cerebral function in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia revealed by “resting state” functional magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:783–92. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadley JA, Nenert R, Kraguljac NV, Bolding MS, White DM, Skidmore FM, et al. Ventral tegmental area/midbrain functional connectivity and response to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1020–30. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y, Evans A. Graph theoretical modeling of brain connectivity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:341–50. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833aa567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswal BB, Mennes M, Zuo XN, Gohel S, Kelly C, Smith SM, et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4734–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narr KL, Leaver AM. Connectome and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:229–35. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh SP, Cooper JE, Fisher HL, Tarrant CJ, Lloyd T, Banjo J, et al. Determining the chronology and components of psychosis onset: the Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS) Schizophr Res. 2005;80:117–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:346–55. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan CG, Cheung B, Kelly C, Colcombe S, Craddock RC, Di Martino A, et al. A comprehensive assessment of regional variation in the impact of head micromovements on functional connectomics. Neuroimage. 2013;76:183–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Wang X, Xia M, Liao X, Evans A, He Y. GRETNA: a graph theoretical network analysis toolbox for imaging connectomics. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:386. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craddock RC, James GA, Holtzheimer PE, III, Hu XP, Mayberg HS. A whole brain fMRI atlas generated via spatially constrained spectral clustering. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:1914–28. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinsfeld AS, Franco AR, Craddock RC, Buchweitz A, Meneguzzi F. Identification of autism spectrum disorder using deep learning and the ABIDE dataset. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;17:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomons TV, Dunlop K, Kennedy SH, Flint A, Geraci J, Giacobbe P, et al. Resting-state cortico-thalamic-striatal connectivity predicts response to dorsomedial prefrontal rTMS in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:488–98. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett CM, Miller MB. How reliable are the results from functional magnetic resonance imaging? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1191:133–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbott CC, Jaramillo A, Wilcox CE, Hamilton DA. Antipsychotic drug effects in schizophrenia: a review of longitudinal FMRI investigations and neural interpretations. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:428–37. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320030014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–2. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achard S, Bullmore E. Efficiency and cost of economical brain functional networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hafeman DM, Chang KD, Garrett AS, Sanders EM, Phillips ML. Effects of medication on neuroimaging findings in bipolar disorder: an updated review. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:375–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Port John D. Diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder by Using MR Imaging and Radiomics: A Potential Tool for Clinicians. Radiology. 2018;287(2):631–632. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Huaiqiang, Chen Ying, Huang Qiang, Lui Su, Huang Xiaoqi, Shi Yan, Xu Xin, Sweeney John A., Gong Qiyong. Psychoradiologic Utility of MR Imaging for Diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Radiomics Analysis. Radiology. 2018;287(2):620–630. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Beek EJR, Kuhl C, Anzai Y, Desmond P, Ehman RL, Gong Q, et al. Value of MRI in medicine: More than just another test?. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:e14–e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Benes FM. Amygdalocortical circuitry in schizophrenia: from circuits to molecules. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:239–57. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RM, Ansari MS, Riccardi P, Li R, Jayathilake K, Dawant B, et al. Occupancy of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2/D3 receptors by olanzapine and haloperidol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2283–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeDoux JE. Emotional memory systems in the brain. Behav Res. 1993;58:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ono T, Nishijo H, Uwano T. Amygdala role in conditioned associative learning. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;46:401–22. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00008-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding D, Li P, Ma XY, Dun WH, Yang SF, Ma SH, et al. The relationship between putamen-SMA functional connectivity and sensorimotor abnormality in ESRD patients. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;12:1346–1354. doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchsbaum MS, Shihabuddin L, Brickman AM, Miozzo R, Prikryl R, Shaw R, et al. Caudate and putamen volumes in good and poor outcome patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:53–62. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill SK, Reilly JL, Ragozzino ME, Rubin LH, Bishop JR, Gur RC, et al. Regressing to prior response preference after set switching implicates striatal dysfunction across psychotic disorders: findings from the B-SNIP study. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:940–50. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren W, Lui S, Deng W, Li F, Li M, Huang X, et al. Anatomical and functional brain abnormalities in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1308–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang H, Shu C, Chen J, Zou J, Chen C, Wu S, et al. Altered corticostriatal pathway in first-episode paranoid schizophrenia: resting-state functional and causal connectivity analyses. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;272:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walther S, Stegmayer K, Federspiel A, Bohlhalter S, Wiest R, Viher PV. Aberrant hyperconnectivity in the motor system at rest is linked to motor abnormalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43:982–92. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang MX, Lee RR, Gaa KM, Song T, Harrington DL, Loh C, et al. Somatosensory system deficits in schizophrenia revealed by MEG during a median-nerve oddball task. Brain Topogr. 2010;23:82–104. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sweeney JA, Haas GL, Li S. Neuropsychological and eye movement abnormalities in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:283–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu M, Zong X, Zheng J, Mann JJ, Li Z, Pantazatos SP, et al. Risperidone-induced topological alterations of anatomical brain network in first-episode drug-naive schizophrenia patients: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychol Med. 2016;46:2549–60. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarpal DK, Robinson DG, Lencz T, Argyelan M, Ikuta T, Karlsgodt K, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and functional connectivity of the striatum in first-episode schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:5–13. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M, Chen Z, Deng W, He Z, Wang Q, Jiang L, et al. Volume increases in putamen associated with positive symptom reduction in previously drug-naive schizophrenia after 6 weeks antipsychotic treatment. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1475–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen C, Wang HL, Wu SH, Huang H, Zou JL, Chen J, et al. Abnormal degree centrality of bilateral putamen and left superior frontal gyrus in schizophrenia with auditory hallucinations: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Chin Med J. 2015;128:3178–84. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.170269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis KL, Kahn RS, Ko G, Davidson M. Dopamine in schizophrenia: a review and reconceptualization. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1474–86. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.11.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Konradi C, Heckers S. Antipsychotic drugs and neuroplasticity: insights into the treatment and neurobiology of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:729–42. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01267-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JH, Cumming P, Son YD, Kim HK, Joo YH, Kim JH. Altered connectivity between striatal and extrastriatal regions in patients with schizophrenia on maintenance antipsychotics: an [(18) F]fallypride PET and functional MRI study. Synapse. 2018;72:e22064. doi: 10.1002/syn.22064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Leon-Ortiz P, Azcarraga M, Stephano S, Favila R, Diaz-Galvis L, et al. Glutamate levels in the associative striatum before and after 4 weeks of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1057–66. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ansell BR, Dwyer DB, Wood SJ, Bora E, Brewer WJ, Proffitt TM, et al. Divergent effects of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics on cortical thickness in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:515–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braus DF, Ende G, Weber-Fahr W, Sartorius A, Krier A, Hubrich-Ungureanu P, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on motor activation measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1999;39:19–29. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bertolino A, Blasi G, Caforio G, Latorre V, De Candia M, Rubino V, et al. Functional lateralization of the sensorimotor cortex in patients with schizophrenia: effects of treatment with olanzapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keedy SK, Rosen C, Khine T, Rajarethinam R, Janicak PG, Sweeney JA. An fMRI study of visual attention and sensorimotor function before and after antipsychotic treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosenberg DR, Sweeney JA, Squires-Wheeler E, Keshavan MS, Cornblatt BA, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Eye-tracking dysfunction in offspring from the New York high-risk project: diagnostic specificity and the role of attention. Psychiatry Res. 1997;66:121–30. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)02975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sweeney JA, Luna B, Srinivasagam NM, Keshavan MS, Schooler NR, Haas GL, et al. Eye tracking abnormalities in schizophrenia: evidence for dysfunction in the frontal eye fields. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:698–708. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crossley NA, Marques TR, Taylor H, Chaddock C, Dell’Acqua F, Reinders AA, et al. Connectomic correlates of response to treatment in first-episode psychosis. Brain. 2017;140:487–96. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ganella EP, Seguin C, Pantelis C, Whittle S, Baune BT, Olver J, et al. Resting-state functional brain networks in first-episode psychosis: a 12-month follow-up study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52:864–75. doi: 10.1177/0004867418775833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hadley JA, Kraguljac NV, White DM, Ver Hoef L, Tabora J, Lahti AC. Change in brain network topology as a function of treatment response in schizophrenia: a longitudinal resting-state fMRI study using graph theory. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:16014. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erdeniz B, Serin E, Ibadi Y, Tas C. Decreased functional connectivity in schizophrenia: the relationship between social functioning, social cognition and graph theoretical network measures. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;270:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ottet MC, Schaer M, Debbane M, Cammoun L, Thiran JP, Eliez S. Graph theory reveals dysconnected hubs in 22q11DS and altered nodal efficiency in patients with hallucinations. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:402. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cao M, Wang JH, Dai ZJ, Cao XY, Jiang LL, Fan FM, et al. Topological organization of the human brain functional connectome across the lifespan. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;7:76–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang L, Su L, Shen H, Hu D. Decoding lifespan changes of the human brain using resting-state functional connectivity MRI. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.