Abstract

Clinical depression commonly emerges in adolescence, which is also a time of developing cognitive ability and related large-scale functional brain networks implicated in depression. In depressed adults, abnormalities in the dynamic functioning of frontoinsular networks, in particular, have been observed and linked to negative rumination. Thus, network dynamics may provide new insight into teen pathophysiology. Here, adolescents (n = 45, ages 13–19) with varying severity of depressive symptoms completed a resting-state functional MRI scan. Functional networks were evaluated using co-activation pattern analysis to identify whole-brain states of spatial co-activation that recurred across participants and time. Measures included: dwell time (proportion of scan spent in that network state), persistence (volume-to-volume maintenance of a network state), and transitions (frequency of moving from state A to state B). Analyses tested associations between depression or trait rumination and dynamics of network states involving frontoinsular and default network systems. Results indicated that adolescents showing increased dwell time in, and persistence of, a frontoinsular-default network state involving insula, dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortex, and posterior regions of default network, reported more severe symptoms of depression. Further, adolescents who transitioned more frequently between the frontoinsular-default state and a prototypical default network state reported higher depression. Increased dominance and transition frequency of frontoinsular-default network states were also associated with higher rumination, and rumination mediated the associations between network dynamics and depression. Findings support a model in which abnormal frontoinsular dynamics confer vulnerability to maladaptive introspection, which in turn contributes to symptoms of adolescent depression.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Depression, Cognitive neuroscience

Introduction

Major depression and related mood syndromes are some of the most prevalent and debilitating illnesses worldwide [1]. These serious disorders tend to emerge during adolescence [2], and early symptoms of depression are related to poorer emotion regulation and a more chronic and severe course of depression over the lifespan [3, 4]. The developmental timing of depression highlights the importance of investigating mood pathology during adolescence, when aberrations in key neurocognitive domains that characterize depression may first emerge [5, 6].

Depression across the lifespan is characterized by abnormalities in the coordinated functioning of large-scale brain networks involved in attention and attention regulation [7]. These include the default network (DN), comprising midline cortical regions, temporal-parietal regions, and areas of hippocampus that together are involved in introspection and autobiographical thinking [8]; the frontoparietal network (FN), including lateral prefrontal and posterior parietal regions that are recruited together in the service of goal-directed attention [9]; and the salience (or ventral attention) network (SN), including insula and mid-cingulate regions involved in salience-directed attention [10]). Coordination across regions of these prototypical networks is believed to reflect regulatory functions, e.g., allocating resources towards or away from other large-scale networks on the basis of salience of internal or external events, supporting regulation of attention towards introspection or towards the external world [11, 12]. In depression, meta-analytic research has revealed increased positive functional connectivity within the DN, weaker negative functional connectivity between the DN and the FN, and bidirectional abnormalities in functional connectivity between midline regions of the DN and insular regions of the SN [7]. Subsequent empirical work has yielded converging evidence for such network abnormalities in depression, and linked them to particular cognitive vulnerabilities. Specifically, adult depression was characterized by increased and more variable resting-state functional connectivity between regions of medial prefrontal cortex and insula, and these frontoinsular abnormalities were associated with the tendency towards negative, repetitive introspection (i.e., rumination) [13] and attention biases towards negative, self-referential information [14]. This evidence has motivated a neurocognitive model of depression in which abnormalities in frontoinsular circuits linking insula with lateral and medial prefrontal systems in the FN and DN, are proposed to contribute to deficits regulating internally-oriented attention, which are cardinal to depression [15, 16].

In refining neurocognitive models of depression, an area of increasing interest is centered on dynamic properties of functional brain networks. Standard methods for estimating resting-state network functioning focus on “static” networks, e.g., networks defined by estimates of the overall correlation in activity among brain regions over extended periods of time [17]. While this approach has merit, it cannot capture dynamic patterns of functional coordination as networks form and dissolve, changes in the spatial organization of transient networks, or patterns of transition between networks over time [18]. Such dynamic properties may be critical for understanding regulatory relationships among regions of different static networks, or other qualities of brain functioning or organization [19, 20]. In recent years, advances in analytic methods have indicated that dynamic properties of resting-state network functioning are reliable [21], disrupted in psychiatric illnesses including mood disorders [13, 22], and associated with individual differences in cognitive functioning and rumination [13, 14]. Of note, the dynamic functioning of transient frontoinsular networks may be especially relevant to disorders characterized by poor attention regulation because according to network-switching models, the process by which regulatory regions allocate resources towards or away from other brain systems is inherently dynamic [16]. Therefore, considering dynamic qualities of frontoinsular networks may be particular informative for the pathophysiology of depression and maladaptive introspection.

Although early exploration of resting-state network dynamics has yielded insights into depression and its cognitive correlates, there is an important developmental gap in this research: to our knowledge, resting-state network dynamics have not been examined in adolescent depression, despite evidence that adolescence is a critical period of brain network development. In the teen years, large-scale functional connections become more robust [6], and cross-network coordination becomes more dynamic at rest [23, 24] and more responsive to task demands [25]. Such network changes coincide with significant gains in self-regulation and learning to pursue goals and manage emotions [5]. According to neurocognitive-developmental models of depression, the convergent timing of these events is no coincidence: abnormal brain network maturation corresponds with impaired development of cognitive abilities (e.g., attention regulation) and rumination that contribute to depression [26]. Therefore, understanding depressive abnormalities in teen network dynamics may be an important research target.

The goal of the present study was to address this developmental gap, by testing the following hypotheses in adolescents with varying levels of depression severity (including individuals with current clinical depression). First, that resting-state dominance of network states involving frontoinsular and DN regions would be associated with higher severity of depression (hypothesis 1) and increased tendency towards rumination (hypothesis 2). Second, exploratory analyses were performed to examine the associations between network state transitions (to our knowledge, a new measure of functional network dynamics) and depression or trait rumination. These analyses tested the hypotheses that the frequency of moving between network states involving frontoinsular and DN regions would be associated with symptom severity (exploratory hypothesis 1), and trait rumination (exploratory hypothesis 2). Third, we predicted that results would support a model in which abnormal functional dynamics of frontoinsular and DN states contribute to depression via maladaptive cognitive style, i.e., that the associations between network dominance (hypothesis 3) or network state transitions (exploratory hypothesis 3) and depression would be mediated by rumination.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants included 45 right-handed adolescents recruited from the Boston area and McLean Hospital programs. Participants were recruited on the basis of either having no history of depression or other psychiatric diagnoses (n = 22) or having a primary diagnosis of major depression (n = 23) (Table 1, S1). This approach was designed to enhance variance in depression severity, supporting dimensional analyses (analyses that consider categorical diagnosis of depression—yielding results consistent with dimensional analyses—are reported in the Supplement). Participants were excluded if they reported a history of mania or hypomania, moderate to severe substance use disorders, eating disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, psychosis, neurological impairment or injury, cognitive or language impairments, or current (past 6 weeks) use of benzodiazepines or stimulant medications. Medication status is reported in Table 1, S1; overall medication use covaried with depression and it was not possible to investigate experimental effects in the absence of medications. Depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with age, self-identified gender, race and ethnicity, or parent education or income (ps > 0.10). However, to control for potential developmental or gender differences across the sample, all analyses controlled for age and gender.

Table 1.

Sample demographics, motion during neuroimaging, and clinical characteristics

| Sample (n = 45) | |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |

| Depressive symptoms (CESD score) | 19.9 (16.8) |

| Trait brooding rumination (RRSB score) | 11.8 (4.8) |

| Age (years) | 16.0 (1.6) |

| FMRI outlier volumes (as % of scan series) | 3.3 (4.5) |

| % | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 71.1% |

| Male | 24.5% |

| Non-binary | 4.4% |

| Medication use | |

| Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 13.3% |

| Selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 8.9% |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 40.0% |

| Tetracyclics | 2.2% |

| Anticonvulsants/Antipsychotics | 17.8% |

| Lithium | 6.7% |

| Anxiolytics (non-Benzodiazepine) | 8.9% |

| Race | |

| White | 77.8% |

| African American | 2.2% |

| Asian | 8.9% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.0% |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.0% |

| Biracial or other | 11.1% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 4.4% |

| Not Hispanic or other | 95.6% |

| % Current diagnosis | |

| Major depressive disorder (MDD) | 51.1% |

| Anxiety disorders secondary to MDD | 15.6% |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.0% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 15.6% |

| Panic disorder | 4.4% |

| Agoraphobia | 0.0% |

| Social phobia | 2.2% |

| Specific phobia | 0.0% |

| (Mild) substance use disorders | 0.0% |

CESD Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, MDD major depressive disorder, SD standard deviation

Procedures

The study included a testing session, which included clinical assessments and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (see Supplement). Research procedures were approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board and were conducted in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

Depressive symptom severity

Current (past week) severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the self-report Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD [27]).

Trait rumination

Trait rumination was evaluated using the self-report Ruminative Responses Scale, Brooding subscale (RRSB [28]). (See Supplement for analyses using other RRS subscales).

Functional imaging

A Siemens Tim Trio 3T scanner and 32-channel head coil were used to collect a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image (TR = 2100 ms, TE = 2.25 ms, GRAPPA acceleration factor of 2, flip angle = 12, 128 slices, field of view = 256 mm, voxel size 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.3 mm), and ten minutes of eyes-open resting functional images using a Human Connectome Project sequence (TR = 720 ms, TE = 30 ms, GRAPPA acceleration factor of 2, flip angle = 66, 66 slices, field of view = 212 mm, voxel size 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm, total volumes = 834) [29]. Resting state fMRI data were collected immediately after anatomical scanning, and prior to other functional scanning.

Analyses

Image preprocessing and corrections

See Supplement for information on image preprocessing, and calculation of motion, artifacts, and outlier volumes using SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/). Motion/outliers were not significantly associated with clinical variables (ps > 0.10, Supplement). Motion/outlier scores were used in subsequent analyses (1) to evaluate associations between specific brain states and motion (so that brain states reflecting motion could be identified and removed from analysis, below), and (2) as covariates in group-level analyses, to control for individual differences in motion across the sample [30, 31].

Resting-state co-activation pattern (CAP) analysis

CAP analysis [32–35] is a data-driven analytic technique that uses the spatial distribution and magnitude of activation at each individual volume and location of whole-brain data as input to a clustering analysis to identify recurring states of relative-co-activation across the brain. CAP analyses were performed using Matlab (version R2016a, Mathworks, Natick, MA) (Fig. 1). First, for each participant and each volume, activation (signal relative to the within-participant global mean at that spatial location) was calculated at each of 130 regions of interest using a whole-brain parcellation of cortex and striatum [36, 37] plus subcortical limbic regions as defined by the AAL atlas [38]. This step yielded a data vector of co-activation estimates for each volume at each ROI and for each participant. Second, co-activation data were concatenated across volumes and participants. Third, k-means clustering was used to partition the data into k brain states that represent recurring patterns of co-activation that emerge over participants and over time. Based on guidelines established in [32], the following range of k values was tested: k = 5, 7, 9, and 11 (see Supplement). Fourth, for each k clustering solution, the resulting co-activation brain states were compared against motion estimates and tested for cohesion of the clustering solution. To compare brain states with motion estimates, we calculated the average framewise displacement associated with each brain state (Table S2): at k = 9 or k = 11, the clustering solution identified a high-motion brain state associated with framewise displacement >1 voxel (displacement estimates of 3.13 mm–3.58 mm). (Informed by [39]). Lower k values failed to identify high-motion brain states, therefore solutions k = 9 and k = 11 were deemed superior for isolating and removing motion contamination. Next, to test cluster cohesion, we calculated silhouette scores (a measure of how similar each volume of data is to the cluster in which it is grouped [40]) for clustering solutions k = 9 and k = 11. The k = 9 solution yielded an average silhouette score of 0.09 (SD = 0.03), and k = 11 yielded an average silhouette score of 0.08 (SD = 0.04), indicating somewhat better cluster cohesion for the k = 9 solution. (Ranges of silhouette scores were comparable to other research using CAP analysis [32, 35]). In sum, among all k solutions tested, the k = 9 clustering solution was superior both in terms of removing motion contamination and yielding more cohesive network states. Therefore, the k = 9 solution was selected, with eight of the brain states from this clustering solution being eligible for experimental analyses (i.e., excluding the high-motion brain-state). Of relevance to hypotheses were a frontoinsular-DN state involving co-activation of insula, dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, and angular gyrus (State 1), and a prototypical DN state of co-activation across midline, temporal, and superior parietal cortex (State 4) (Fig. 2). On average, participants spent 32.22% of scan time in one of these two brain states (see Tables S2–S4, Figs. S1–S5, for additional information on this and other k solutions).

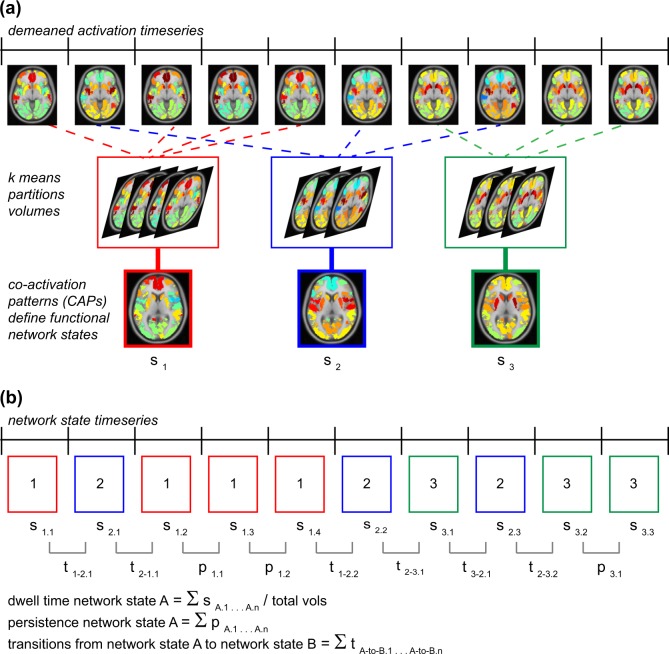

Fig. 1.

Analytic method for evaluating resting-state network dynamics. Displayed are analytic steps used in this study for evaluating resting-state network dynamics using co-activation pattern analysis (CAP [32–34]). a For each participant and each volume of data, activation (relative to the within-participant global mean at that spatial location) was calculated at each of 130 regions of interest using a whole-brain parcellation of cortex and striatum [36, 37] plus subcortical limbic regions as defined by the AAL atlas [38]. This step yielded a data vector of co-activation estimates for each volume at each ROI and for each participant (demeaned activation timeseries). Data vectors were concatenated across volumes and participants, and k-means clustering was used to partition the data into k functional network states that represent recurring patterns of co-activation over time and across participants. b Each volume of data was coded by its categorization in a network state, as defined by the k means analysis, yielding a timeseries for each participant with each volume coded by network state (network state timeseries). The network state timeseries was used to compute measures of network dynamics for each participant, including (1) overall dwell time in a network state: proportion of volumes that the participant spent in that brain state over the scan series (summed volumes in that brain state divided by total number of volumes in the series), (2) persistence of a network state: total (summed) volume-to-volume maintenance of that brain state, and (3) total (summed) frequency of state-to-state transitions from one volume to the next (e.g., frequency of moving from state A to state B)

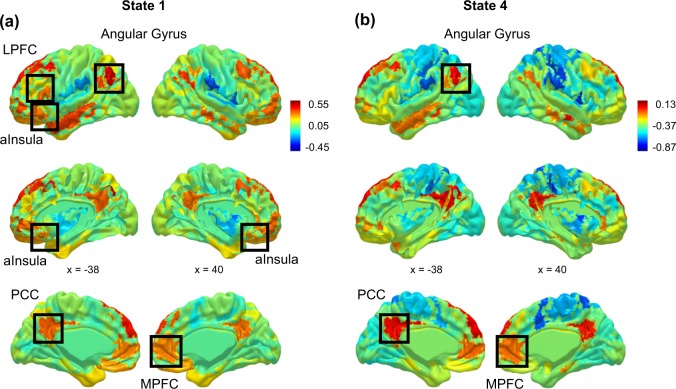

Fig. 2.

Functional brain network states identified using co-activation pattern analysis (CAP). Two brain network states of co-activation identified via CAP analysis, involving areas of frontoinsular cortex and the prototypical default network, were relevant to hypotheses. a State 1 was characterized by relatively higher activation in frontoinsular areas of anterior insula, and lateral and medial prefrontal cortex; and posterior regions of the default network, including posterior cingulate and angular gyrus. b State 4 was characterized by relatively higher activation in regions of the prototypical default network including midline and temporal cortex, and angular gyrus. For other brain network states identified in CAP analysis, see Fig. S1. Note: anterior insula (aInsula), medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Network states are normalized to show patterns of activation or deactivation relative to the within-state average; the numeric anchors for the activation scale for each network state show the correspondence between the within-state average and the global average of activation across all brain regions and all volumes of the scan series

First-level analyses: resting-state network dynamics

For first-level analysis, measures of resting-state network dominance and transitions were calculated for each participant. Measures of network state dominance included (1) overall dwell time in a network state (total proportion of volumes that the participant spent in that brain state over the scan series) and (2) persistence of a network state (total volume-to-volume maintenance of that brain state). The measure of network transitions was (3) total frequency of state-to-state transitions from one volume to the next (e.g., frequency of moving from state A to state B). Measures of network dynamics were calculated using Matlab and R.

Group-level analyses

Group-level analyses were performed using partial correlations and bootstrapped mediation analysis in SPSS, and included age, gender, and motion/outlier scores as covariates. All variables were centered using z-transformation or contrast-coding.

Analyses tested the hypotheses that dominance of transient network states involving frontoinsular and DN regions would be associated with depression and trait rumination, and that the association between network state dominance and depression severity would be mediated by rumination. (See Supplement for analyses conducted with other network states, about which we had no a priori hypotheses). These analyses were accomplished by correlating measures of dwell time or persistence in relevant network states (State 1 and State 4) first with depressive symptom severity (CESD), and second with rumination (RRSB). Third, the indirect effects of network dominance on depression severity through trait rumination were tested with a bootstrapped mediation analysis (10,000 samples) [41].

Exploratory analyses focused on network state transitions. In these analyses, depressive symptom severity (CESD) or rumination (RRSB) were each correlated with the frequency of a given state-to-state transition. Participants who occupied a given network state for <5% of the timeseries were ineligible for these analyses, as estimates of network-to-network transitions would be suppressed in these cases due to low representation of that network state in the timeseries (this procedure resulted in no more than one participant removed from a given analysis). Finally, exploratory mediation analyses tested the indirect effects of network state-to-state transition frequency on depression severity through rumination.

Results

Network dominance

Dominance of a network state involving co-active frontoinsular and DN regions is related to depression severity

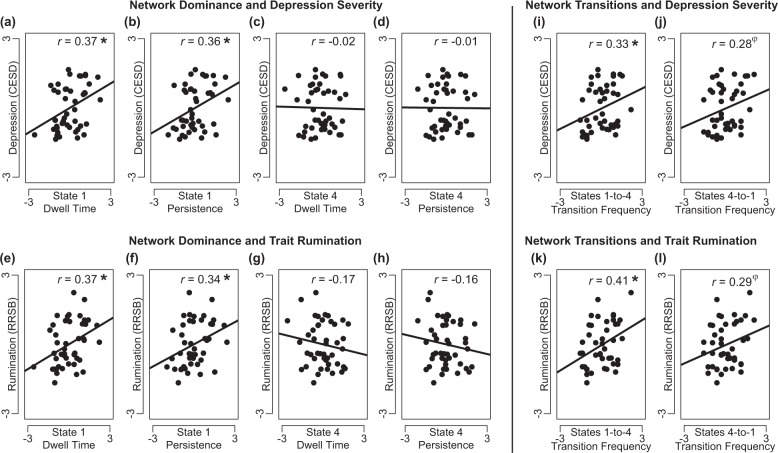

Both increased overall dwell time, r(40) = 0.37, p = 0.01, and longer persistence, r(40) = 0.36, p = 0.01, of network State 1 were associated with higher depressive symptom severity (Fig. 3). However, dwell time and persistence of State 4 were not associated with symptom severity, r(40) = −0.02, p = 0.89, and r(40) = −0.01, p = 0.96. These effects indicate that resting-state dominance of a transient network involving co-active frontoinsular and DN regions (State 1) was significantly related to depression in adolescents, but dominance of a prototypical DN state (State 4) was not.

Fig. 3.

Network state dominance and transitions in association with depression and trait brooding rumination. First, considering network state dominance in relation to depressive symptoms, correlation analyses revealed that a higher dwell time (overall proportion of the resting-state scan spent in a network state) and b longer persistence (volume-to-volume maintenance of a network state) of a network state involving regions of frontoinsular cortex and default network (State 1) were associated with higher severity of depression (scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression [CESD] Scale). In contrast, neither c dwell time nor d persistence in a network state more restricted to the prototypical default network (State 4) was significantly related to severity of depression. Second, considering network state dominance in relation to trait rumination, e higher dwell time and f longer persistence of State 1 were associated with increased trait brooding rumination (scores on the Ruminative Responses Scale - Brooding Subscale [RRSB]). However, neither g dwell time nor h persistence of State 4 was significantly related to trait rumination. Third, considering dynamic transitions among these networks in relation to depression and rumination, i increased frequency of State 1-to-State 4 transitions was associated with higher severity of depression, but j the relationship between frequency of State 4-to-State 1 transitions and severity of depression did not reach statistical significance; and k increased frequency of State 1-to-State 4 transitions was associated with higher levels of trait rumination, but l the relationship between frequency of State 4-to-State 1 transitions and trait rumination did not reach statistical significance. Note: All correlation analyses controlled for age, gender, and motion/outlier covariates; displayed on x-axes are z-transformed measures of network dynamics, displayed on y-axes are z-transformed and residualized CESD or RRSB scores. Reported are partial correlation coefficients, φp < 0.10, *p < 0.05

Associations between depression and dwell or persistence of other networks (about which we had no a priori hypotheses) are reported in Table S3. In brief, decreased dwell time and shorter persistence of State 7 (involving primarily sensorimotor regions) and State 6 (involving activation in striatal regions) were both associated with higher severity of depression. (See Supplement for details).

Dominance of a network state involving co-active frontoinsular and DN regions is related to trait rumination

Complementing results above, both increased dwell time in, r(40) = 0.37, p = 0.01, and longer persistence of, r(40) = 0.34, p = 0.02, network State 1 were associated with higher tendency towards brooding rumination (Fig. 3). However, neither dwell time nor persistence of State 4 were significantly associated with rumination, r(40) = −0.17, p = 0.28 and r(40) = −0.16, p = 0.31. Thus together, dominance of a transient network spanning frontoinsular and DN regions (State 1) was related to both depressive symptoms and to trait brooding rumination.

Network transitions

Frequency of network transitions involving frontoinsular and DN regions is related to depression severity

Higher frequency of State 1-to-State 4 transitions was correlated with higher severity of depression, r(39) = 0.33, p = 0.04 (Fig. 3). The association between frequency of State 4-to-State 1 transitions and depression did not reach significance, r(39) = 0.28, p = 0.07. A Meng test [42] clarified, however, that correlations between depression and each type of state-to-state transition were not significantly different, z = −0.71, p = 0.47 (See also Table S4).

Frequency of network transitions involving frontoinsular and DN regions is related to trait rumination

Higher frequency of State 1-to-State 4 transitions was correlated with increased tendency towards rumination, r(39) = 0.41, p < 0.01. The association between higher frequency of State 4-to-State 1 transitions and rumination was not significant, r(39) = 0.29, p = 0.07 (Fig. 3). A Meng test revealed that correlations between rumination and each type of state-to-state transition were not significantly different, z = −1.60, p = 0.11.

Of note, neither depressive symptoms nor trait rumination were significantly related to overall frequency of network transitions, ps > 0.10, and controlling for overall transitions in the above analyses did not alter the pattern or significance of effects. Together, these results indicate that the tendency to move frequently between a frontoinsular-DN state and a prototypical DN state is associated with both depressive symptoms and the trait tendency towards rumination; critically, these relationships cannot be explained by generally higher network switching.

Mediated effects of network dynamics

Indirect effect of frontoinsular-default network dominance on depression through rumination

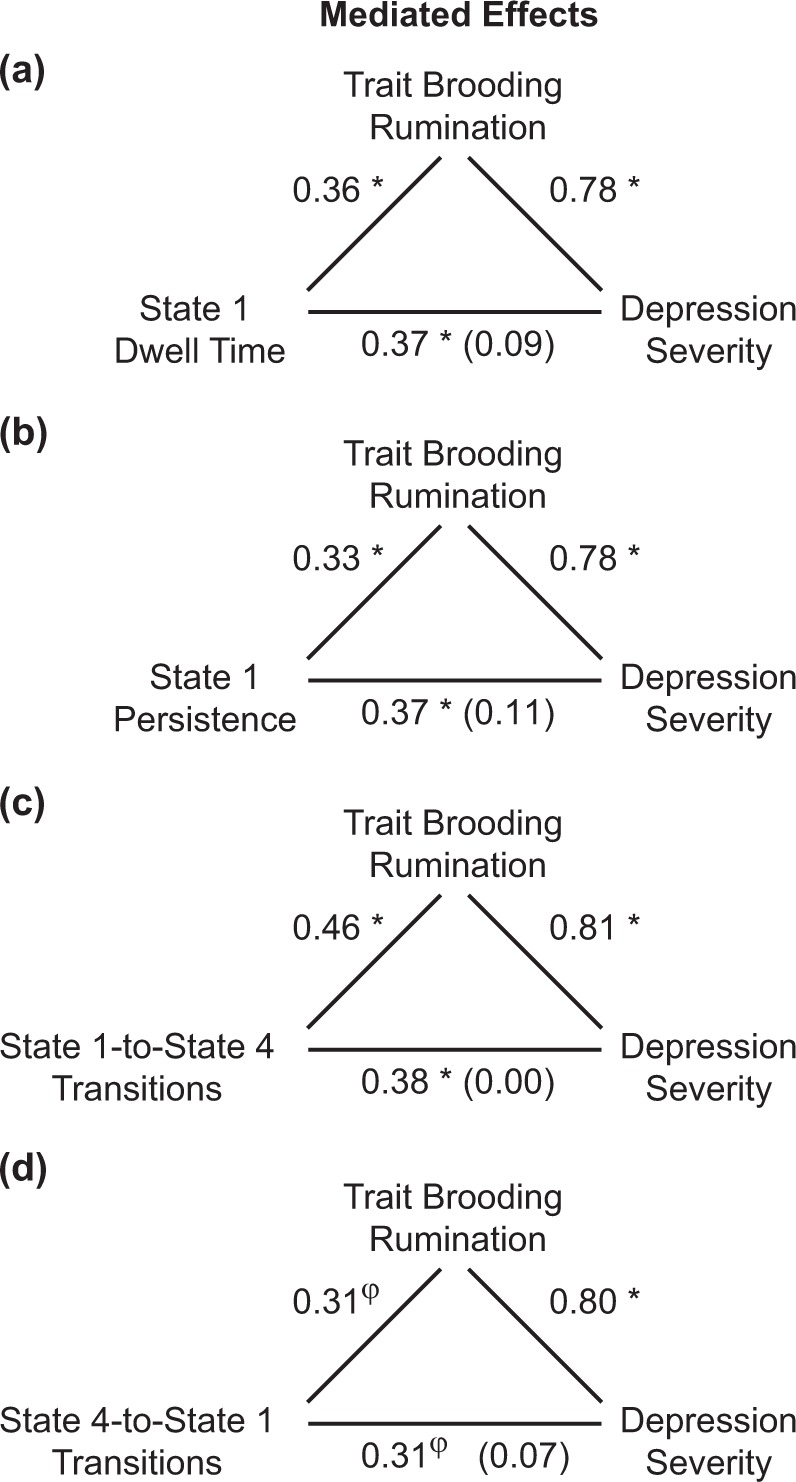

Following the direct effects of State 1 dominance on depression reported above, we used a bootstrapping approach to estimate the indirect effects of network dominance (dwell time or persistence of State 1: X variable) on depressive symptom severity (CESD: Y variable) through brooding rumination (RRSB: M variable). Mediation analyses revealed significant indirect effects of both State 1 dwell (indirect effect = 5.92, SE(boot) = 2.17, bias-corrected 95% CI: 1.96–10.61) and State 1 persistence (indirect effect = 0.0074, SE(boot) = 0.0032, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.0017–0.0143) via trait rumination on depressive symptoms (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mediation models. A bootstrapping approach was used to estimate the indirect effect of network dominance (dwell time or persistence of State 1) or state-to-state transitions (transitions from State 1 to State 4, or State 4 to State 1) on depressive symptom severity (scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression [CESD] Scale) through trait brooding rumination (scores on the Ruminative Responses Scale – Brooding [RRSB] Subscale). Mediation analyses revealed significant indirect effects of a State 1 dwell (indirect effect = 5.92, SE(boot) = 2.17, bias-corrected 95% CI: 1.96–10.61), b State 1 persistence (indirect effect = 0.0074, SE(boot) = 0.0032, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.0017–0.0143), and c State 1-to-State 4 transitions (indirect effect = 0.07, SE(boot) = 0.02, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.02–0.12), via trait brooding rumination on depressive symptoms. d The indirect effect of State 4-to-State 1 transitions via brooding on depressive symptoms did not reach statistical significance (indirect effect = 0.04, SE(boot) = 0.02, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.00–0.08). Displayed are standardized path coefficients for each path of the mediation models, φp < 0.10, *p < 0.05

Indirect effect of frontoinsular-DN transitions on depression through rumination

Following the direct effects of network transitions on depression reported above, exploratory mediation analyses were performed to evaluate the indirect effect of network state-to-state transitions (frequency of transitions, State 1-to-State 4, or State 4-to-State 1: X variable) on depressive symptom severity (CESD: Y variable) through brooding rumination (RRSB: M variable). There was a significant indirect effect of State 1-to-State 4 transitions (indirect effect = 0.07, SE(boot) = 0.02, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.02–0.12) via trait brooding rumination on depressive symptoms (Fig. 4). The indirect effect of State 4-to-State 1 transitions via brooding on depressive symptoms did not reach statistical significance (indirect effect = 0.04, SE(boot) = 0.02, bias-corrected 95% CI: 0.00–0.08).

Discussion

Adolescent depression is an important target of neurocognitive research: achieving a better understanding of brain network dysfunction, and maladaptive cognitive styles that may be reflected in or fueled by such dysfunction, can provide important insight into early-stage mood pathology [5]. Towards this goal, the present study shows that teens characterized by resting-state dominance of a network state involving frontoinsular regions and areas of DN reported a greater tendency towards maladaptive rumination and more severe depressive symptoms. In addition, the present study provides novel evidence that adolescent depression and rumination are each associated with higher frequency of transitions between a (dominant) frontoinsular-DN state and a prototypical DN state. Finally, this study reveals mediated effects supporting a neurocognitive model in which abnormal frontoinsular dynamics make teens more prone to rumination, which in turn contributes to depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with prior findings [13, 14, 43] and extend that research by focusing on adolescence.

Intrinsic functional dominance of the DN has been previously observed in adults [7]. The present findings suggest, however, that the nature of DN-related dominance in adolescent depression is complex: here, more severely depressed teens showed increased dominance of a “mixed” network characterized by co-activation across regions of anterior insula (typically grouped within the SN), prefrontal cortex (including dorsolateral areas of the FN, and medial regions of the DN), and other posterior regions of the DN (i.e., posterior cingulate, angular gyrus), but did not exhibit differences in dominance of a network state that was restricted to the prototypical DN. Conceptually, these results are consistent with the idea that heightened depression is related to biases for frontoinsular regions to engage with areas of the DN—e.g., insula or dorsolateral systems acting to allocate resources towards midline and temporal regions of cortex, or receive salience-related signals from regions of the DN [44]. Coordination across frontoinsular and DN systems may play a role in directing attention towards or away from internal thoughts [12], making these regions especially relevant to biases towards—or the capacity to disengage from—rumination. The dominance of frontoinsular-DN co-activation may reflect impaired ability to disengage from rumination, or amplified salience of ruminative thoughts (and this may apply not only to brooding, but also other forms of self-focused thinking during negative mood; see Supplement). In contrast, normative activity of a prototypical DN state suggests that networks recruited more generally for introspection (e.g., including other forms of mind wandering that are benign or less intrusive) may be less involved in rumination. Future research aimed at understanding various forms of introspection as they relate to different transient functional networks involving classic DN systems, along with other regulatory systems in insula or prefrontal cortex, may help to distinguish these possibilities.

In addition to highlighting frontoinsular and DN dominance, the present study provides evidence that dynamic transitions between network states may be an important dimension of abnormal brain functioning in adolescent depression. More severely depressed teens not only persisted longer in a frontoinsular-DN state, they also tended to transition more frequently between an frontoinsular-DN state and a prototypical DN state. These patterns of increased transition frequency may signify a functional tendency for regions of prefrontal cortex or insula to be deployed to regulate ongoing activity in the DN, for frontoinsular functioning to be influenced by midline or temporal cortical activation, or instability in the regulatory relationships among these regions (consistent with [13]). One interpretation that links transition frequency to cognitive processes is that for people prone to rumination, transient increases in intrusive, emotionally salient thoughts and/or efforts to direct attention away from emotional thoughts tends to contaminate introspection (reflected in shifts between frontoinsular-DN and DN states). The idea that ruminative thoughts are experienced as intrusive and inescapable is consistent with prior clinical research [45].

There are several limitations of the present study. First, the relative contribution of state versus trait-like properties to estimates of network functioning are unknown [46]. During resting-state, frontoinsular-DN dominance or transitions may reflect brain functions that correspond with in vivo ruminative thinking, or intrinsic functioning of these networks that confers vulnerability to rumination. This issue challenges the interpretation of any resting-state study, but may be addressed with procedures such as thought-sampling or repeated within-person measurement to evaluate the stability of resting-state (including dynamic) properties. Second, although these results converge with previous research using other dynamic methods [13, 43], future research that integrates multiple methodological approaches will help to illustrate the attributes (or weaknesses) of various methods while also providing a clearer sense of what are meaningful dimensions of network dynamics. In parallel, future research may focus on other transient networks, e.g., involving sensorimotor or striatal regions that were implicated in this study but fell beyond the scope of a priori hypotheses (see Supplement). Third, adolescents with current major depression were the primary users of psychoactive medications in this study, and we could not disentangle general medication use from depression severity. Research that evaluates brain network functioning in unmedicated teens may provide additional information. Fourth, the sample included adolescents with an anxiety disorder secondary to major depression (n = 7). Excluding these subjects did not alter the pattern of effects (see Supplement), but future research should investigate the moderating effect of anxiety on associations between depression, introspection (including worry) and network functioning. Fifth, the study sample size was not large enough to examine developmental effects, and although analyses covaried age, pubertal stage was not evaluated. Prior research has shown that resting network dynamics change over adolescent development [25], and the onset of puberty is related to increased rumination and heightened risk of depression—especially for girls [47, 48]. Future research that targets pubertal stage and gender may provide new insight into the etiology and timing of network abnormalities. Together, the present findings constitute a preliminary exploration of network dynamics; future research in larger, independent samples is needed to evaluate the reliability of these effects.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that teens characterized by dominant activation in frontoinsular-default networks, and frequent transitions between networks involving frontoinsular and DN systems, are more prone to rumination and report more severe symptoms of depression. Mediation results support a neurocognitive model in which abnormal frontoinsular network dynamics make teens more prone to rumination, which in turn exacerbates depressive symptoms. Future research in larger samples that evaluates network dynamics over the course of adolescent development may provide insight into neurocognitive dimensions that reflect or contribute to mood health.

Supplementary information

Funding and disclosure

Supported by the Phyllis and Jerome Lyle Rappaport Fellowship (R.H.K.), NIMH grants F32MH106262, 1R56MH117131-01 (R.H.K.) and 5R37MH095809 (D.A.P). R.P.A. was partially supported by K23MH097786. The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article. Over the past three years, D.A.P received consulting fees from Akili Interactive Labs, BlackThorn Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Posit Science and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA and honoraria from Alkermes for activities unrelated to the current study. A subset of analyses reported here were presented (by R.H.K.) at the 2017 annual meetings of the Society of Biological Psychiatry and the Society for Research on Psychopathology.

Author contributions

RHK developed the study concept and RHK and DAP contributed to the study design; RHK and RMH contributed to analytic design. Testing and data collection were performed by RHK, MK, FG, and RC; and JV, EE, BA, and RPA provided support in recruitment and evaluation of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Data analysis was conducted by RHK and interpretation of analyses was performed by RHK, MK, and DAP. Funding provided by RHK and DAP. RHK drafted the paper, and all other authors provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-019-0399-3).

References

- 1.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:372–80. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma YJ, et al. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J, et al. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: Moodiness or mood disorder? Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:133–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Levita L, Libby V, Pattwell SS, Ruberry EJ, et al. The storm and stress of adolescence: insights from human imaging and mouse genetics. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52:225–35. doi: 10.1002/dev.20447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power JD, Fair DA, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. The development of human functional brain networks. Neuron. 2010;67:735–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Jama Psychiatry. 2015;72:603–11. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews-Hanna JR, Smallwood J, Spreng RN, editors. The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1316:29–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Zanto TP, Gazzaley A. Fronto-parietal network: flexible hub of cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:602–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008;58:306–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon ML, De la Vega A, Mills C, Andrews-Hanna J, Spreng RN, Cole MW, et al. Heterogeneity within the frontoparietal control network and its relationship to the default and dorsal attention networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E1598–607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715766115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser RH, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Dillon DG, Goer F, Beltzer M, Minkel J, et al. Dynamic resting-state functional connectivity in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1822–30. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser Roselinde H., Snyder Hannah R., Goer Franziska, Clegg Rachel, Ironside Manon, Pizzagalli Diego A. Attention Bias in Rumination and Depression: Cognitive Mechanisms and Brain Networks. Clinical Psychological Science. 2018;6(6):765–782. doi: 10.1177/2167702618797935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser RH. Neurocognitive markers of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:e29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:483–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–41. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchison RM, Womelsdorf T, Allen EA, Bandettini PA, Calhoun VD, Corbetta M, et al. Dynamic functional connectivity: promise, issues, and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2013;80:360–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bray S, Arnold A, Levy RM, Iaria G. Spatial and temporal functional connectivity changes between resting and attentive states. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:549–65. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang C, Liu ZM, Chen MC, Liu X, Duyn JH. EEG correlates of time-varying BOLD functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2013;72:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calhoun VD, Miller R, Pearlson G, Adali T. The Chronnectome: time-varying connectivity networks as the next frontier in fMRI data discovery. Neuron. 2014;84:262–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rashid B, Arbabshirani MR, Damaraju E, Cetin MS, Miller R, Pearlson GD, et al. Classification of schizophrenia and bipolar patients using static and dynamic resting-state fMRI brain connectivity. Neuroimage. 2016;134:645–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faghiri A, Stephen JM, Wang YP, Wilson TW, Calhoun VD. Changing brain connectivity dynamics: from early childhood to adulthood. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:1108–17. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marusak HA, Calhoun VD, Brown S, Crespo LM, Sala-Hamrick K, Gotlib IH, et al. Dynamic functional connectivity of neurocognitive networks in children. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38:97–108. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchison RM, Morton JB. Tracking the brain’s functional coupling dynamics over development. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6849–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4638-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser RH, Pizzagalli DA. Dysfunctional connectivity in the depressed adolescent brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:594–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The use of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in adolescents and young-adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:149–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27:247–59. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith SM, Vidaurre D, Beckmann CF, Glasser MF, Jenkinson M, Miller KL, et al. Functional connectomics from resting-state fMRI. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:666–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Power JD, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Recent progress and outstanding issues in motion correction in resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2015;105:536–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan CG, Cheung B, Kelly C, Colcombe S, Craddock RC, Di Martino A, et al. A comprehensive assessment of regional variation in the impact of head micromovements on functional connectomics. Neuroimage. 2013;76:183–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JE, Chang C, Greicius MD, Glover GH. Introducing co-activation pattern metrics to quantify spontaneous brain network dynamics. Neuroimage. 2015;111:476–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.X L, C. C, D. JH. Decomposition of spontaneous brain activity into distinct fMRI co-activation patterns. Front Syst Neurosci. 2013;7:11. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Duyn JH. Time-varying functional network information extracted from brief instances of spontaneous brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4392–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216856110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Zhang NY, Chang CT, Duyn JH. Co-activation patterns in resting-state fMRI signals. Neuroimage. 2018;180:485–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi EY, Yeo BTT, Buckner RL. The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:2242–63. doi: 10.1152/jn.00270.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–65. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rummel C, Verma RK, Schopf V, Abela E, Hauf M, Berruecos JFZ, et al. Time course based artifact identification for independent components of resting-state fMRI. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:8. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rousseeuw PJ. Silhouettes - a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster-analysis. J Comput Appl Math. 1987;20:53–65. doi: 10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–31. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng XL, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:172–5. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH, et al. Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:655–67. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papageorgiou Costas, Wells Adrian. Metacognitive beliefs about rumination in recurrent major depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;8(2):160–164. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(01)80021-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geerligs L, Wells A. State and trait components of functional connectivity: individual differences vary with mental state. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13949–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1324-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nolen-Hoeksema S. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:424–43. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins ER. A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:589–609. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.