Abstract

The present study examined fluctuation over time in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among 34 combat veterans (28 with diagnosed PTSD, 6 with subclinical symptoms) assessed every 2 weeks for up to 2 years (range of assessments = 13–52). Temporal relationships were examined among four PTSD symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal) with particular attention to the influence of hyperarousal. Multilevel cross-lagged random coefficients autoregression for intensive time series data analyses were used to model symptom fluctuation decades after combat experiences. As anticipated, hyperarousal predicted subsequent fluctuations in the 3 other PTSD symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing) at subsequent 2-week intervals (rs = .45, .36, and .40, respectively). Additionally, emotional numbing influenced later reexperiencing and avoidance, and reexperiencing influenced later hyperarousal (rs = .44, .40, and .34, respectively). These findings underscore the important influence of hyperarousal. Furthermore, results indicate a bidirectional relationship between hyperarousal and reexperiencing as well as a possible chaining of symptoms (hyperarousal → emotional numbing → reexperiencing → hyperarousal) and establish potential internal, intrapersonal mechanisms for the maintenance of persistent PTSD symptoms. Results suggested that clinical interventions targeting hyperarousal and emotional numbing symptoms may hold promise for PTSD of long duration.

The frequency, intensity, and duration of posttraumatic symptoms following exposure to extremely stressful life events can vary widely. Some people experience no or few symptoms, others face immediate notable symptoms that decrease over time, and others suffer severe and persistent symptoms (Bonanno, Westphal, & Mancini, 2011; King, King, Salgado, & Shalev, 2003; Koss & Figueredo, 2004). Roughly one in seven individuals exposed to a traumatic event develops symptoms that persist for at least 1 month and meet the diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Gates et al., 2012; White et al., 2014). Approximately one third of these individuals experience symptoms that remain elevated or worsen over years (Freedman, Brandes, Peri, & Shalev, 1999; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Shalev et al., 1998). The goal of the present study was to better understand the dynamic interplay among PTSD symptoms in a group of Vietnam veterans with symptoms of combat-related PTSD. Increased understanding of PTSD symptom course and especially how symptoms influence one another to maintain the disorder is important for prevention and treatment of PTSD.

Chronic PTSD was defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) as lasting 3 months or more. Although a definition for chronic PTSD was not included in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), the manual noted that PTSD symptoms have been documented to persist well beyond 3 months, even for 50 years or more following trauma exposure (APA, 2013). The recently released findings of the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study (Marmar et al., 2015) reinforce the notion that a subset of combat veterans from that war continue to suffer from prolonged symptom severity approximately four to five decades after their warzone experiences. Rates of long-lasting chronic PTSD may be higher among combat veterans who experienced multiple traumatic stressors in a warzone characterized by generalized danger during many months of duty than among individuals exposed to a single traumatic event (Hoge et al., 2004; King, King, Foy, Keane, & Fairbank, 1999; Schnurr, Lunney, Sengupta, & Waelde, 2003). Chronic PTSD is associated with substantial costs to both individuals and society at large, as those with PTSD are more likely to suffer from marital and family difficulties (Monson, Taft, & Fredman, 2009; Taft, Schumm, Panuzio, & Proctor, 2008), unemployment and lower incomes (Sanderson & Andrews, 2006; Savoca & Rosenheck, 2000), and physical health problems (Abt Associates, 2014; O’Toole, Catts, Outram, Pierse, & Cockburn, 2009; Schnurr & Green, 2004).

The symptom clusters of PTSD have been defined in different ways since PTSD was first codified in the DSM-III (APA, 1980). The three PTSD symptom clusters first identified in the diagnostic criteria were reexperiencing, numbing, and a cluster that included symptoms of hyperarousal, avoidance, and reactivity. The DSM-III-R and DSM-IV (APA, 1987, 1994) identified three clusters: reexperiencing, avoidance (including emotional numbing), and hyperarousal. Much research has emphasized these three clusters. Empirical findings, however, on the underlying structure of measures of PTSD have yielded evidence for four (King et al., 1998; Simms, Watson, & Doebbeling, 2002)—and possibly five (Elhai, Palmieri, Biehn, Frueh, & Magruder, 2010)—factors or symptom clusters, each of which distinguishes the avoidance set of symptoms from the emotional numbing set of symptoms. The publication of the DSM-5 has formalized the split into a revised avoidance cluster and another cluster referencing negative alterations in cognition and mood, which includes emotional numbing.

Extant literature on the functional relationships among PTSD symptom clusters over time suggests that hyperarousal symptoms may play a particularly important role in both the development and maintenance of PTSD. Schell, Marshall, and colleagues (Schell, Marshall, & Jaycox, 2004; Marshall, Schell, Glynn, & Shetty, 2006) were among the first to use a prospective design to study the temporal dynamics among PTSD symptom clusters following a traumatic experience. In their studies of young adult community violence survivors assessed shortly after the trauma and again at 3 and 12 months, these researchers examined the influence of the PTSD clusters upon each other across the two intervals using cross-lagged panel analysis. Although the symptom clusters were defined differently in the two studies (one with avoidance and emotional numbing symptoms combined and the other with those clusters separated), both found that hyperarousal predicted, and was not predicted by, the other symptom clusters. Thus, in the year following a trauma, the hyperarousal symptom cluster appears to be prominent in influencing later symptoms. In the words of Schell et al. (2004), hyperarousal “... plays a crucial role in shaping the natural course of posttraumatic distress following trauma exposure” (p. 196).

In a longitudinal study spanning two decades, Solomon, Horesh, and Ein-Dor (2009) also used a prospective design and applied cross-lagged panel analysis to the three DSM-IV PTSD symptom clusters. Israeli veterans of the 1982 Lebanon War were assessed at 1-, 2-, and 20-years postwar. Similar to the findings of Schell et al. (2004) and Marshall et al. (2006), this study found that hyperarousal symptoms at the initial assessment predicted reexperiencing and avoidance/emotional numbing symptoms at both subsequent time points. Given the influence of the hyperarousal cluster of symptoms on other symptoms over a 19-year span, Solomon et al. (2009) referred to hyperarousal as the “engine” (p. 842) that drives other symptoms.

In addition to self-reported hyperarousal symptoms, evidence suggests that some physiological indicators of arousal immediately following trauma may distinguish people who go on to develop PTSD from those who do not. For example, Coronas et al. (2011) assessed motor vehicle accident survivors during ambulance rescue and in the emergency room and found that heart rate at the scene of the injury predicted PTSD status 4 months later. Additionally, Suendermann, Ehlers, Boellinghaus, Garner, and Glucksman (2010) examined heart rate and skin conductance of motor vehicle accident survivors within 1 month of the accident as they viewed standardized trauma-related, threatening, and neutral pictures. Heart-rate responses to trauma-related pictures predicted PTSD symptom severity 6 months after the trauma, even after accounting for early PTSD symptoms.

Hyperarousal is not the only PTSD symptom cluster that has been found to substantially influence later symptoms. In a study with a design that allowed examination of PTSD symptoms both prior to and following the stress of military deployment, emotional numbing emerged as the strongest predictor of subsequent PTSD symptoms (MacDonald, Proctor, Heeren, & Vasterling, 2013). Using a prospective cross-lagged design and path analysis, these researchers found that predeployment emotional numbing was related to all postdeployment PTSD symptom clusters (including subsequent emotional numbing), whereas predeployment hyperarousal was related to three of four postdeployment symptom clusters (all but avoidance). In a community sample, emotional numbing symptoms distinguished persistent PTSD symptoms from less severe posttrauma disturbance (Breslau, Reboussin, Anthony, & Storr, 2005). Among veterans of the 1991 Gulf War, emotional numbing and hyperarousal, but not reexperiencing or avoidance symptoms, increased postdeployment and were associated with other symptoms of psychological distress (Thompson et al., 2004). These studies provide more limited support for the preeminence of hyperarousal symptoms, and highlight the potential contribution of emotional numbing symptoms in subsequent PTSD symptoms.

The current study assessed individuals whose symptoms of PTSD had persisted for years and examined the dynamic, within-person process by which hyperarousal and the other symptom clusters influenced one another to perpetuate symptom severity. Vietnam veterans who experienced traumatic events in the warzone decades earlier and suffered posttraumatic distress participated in this longitudinal study. The 17 DSM-IV-based symptoms were clustered to reflect the dimensions of reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal (King et al., 1998), a structure that has been affirmed across different PTSD measures and a variety of populations (e.g., DuHamel et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2010; Palmieri, Weathers, Difede, & King, 2007). These symptom clusters were assessed over 2-week intervals for up to 2 years, and these data were subjected to a within-person cross-lagged analysis corresponding to the multilevel time-series structure. Based on previous research findings (Marshall et al., 2006; Schell et al., 2004; Solomon et al., 2009), we specifically hypothesized that within-person fluctuation in the hyperarousal cluster would predict fluctuation in the levels of the other PTSD symptom clusters. This study provides information about whether the influence of hyperarousal on subsequent symptoms observed in developing PTSD also holds for chronic PTSD. Additionally, we explored possible temporal associations among the other symptom clusters that could provide insight into the underlying dynamic mechanisms that sustain PTSD symptomatology to reflect chronic course.

Method

Participants and Procedure

All procedures were approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited from the VA Boston Healthcare System via posted flyers. Individuals were excluded if they were actively psychotic, currently suicidal or homicidal, without telephone access, or had experienced substance or alcohol abuse or dependence within the previous 6 months. Participants were 34 male veterans who served in the Vietnam theater between 1965–1975. At the outset of the study, staff obtained written informed consent from all participants and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) was administered to all study participants by a master’s- or doctoral-level clinician. There were 28 participants (82.4%) who met DSM-IV criteria for current combat-related PTSD. The remaining six (17.6%) met criteria only for lifetime PTSD but had substantial current symptoms (CAPS severity score M = 43.33 [moderate]; range = 27 [mild] to 67 [severe]; Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). At the time of enrollment in the study, participants ranged in age from 49 to 69 years (M = 54.78, SD = 4.12). The racial/ethnic demographics of the sample were Caucasian, 73.6% (25); African American, 20.6% (7); Hispanic, 2.9% (1); and Native American/Native Alaskan, 2.9% (1). The majority of participants were married (20; 58.8%) and receiving Veterans Affairs (VA) disability compensation (26; 76.5%). About a third (11; 32.4%) were employed either fulltime or part time.

PTSD symptoms were assessed every 2 weeks for 2 years between April 2000 and June 2004. The majority of the 53 possible assessments (baseline plus biweekly over the 2 years) were administered over the telephone by one of two clinicians (a licensed clinical social worker and a master’s-level clinical psychology graduate student pursuing a doctorate). Telephone assessments were scheduled for a specific day and time every 14 days; follow-up telephone calls were made if the participant was not available when the clinician called. If the assessment was not completed during the week following the scheduled call, the assessment was considered missing. On three occasions for each participant (baseline, 12 months, and 24 months), the assessments were administered as part of an in-person structured interview. Most participants—23 (21 participants with diagnosed PTSD and 2 with subclinical symptoms) or 67.6%—were very cooperative with the telephone assessments and completed over two thirds of the assessments (range = 69.8%−98.1%). Eight participants (four with diagnosed PTSD and four with subclinical symptoms; 23.5%) had lengthy absences followed by periods of consistent participation, but still completed over half of the assessments (range = 50.9%−66.0%). Three participants (all with diagnosed PTSD; 8.8%) completed one fourth to just over one third of the assessments (range = 24.5%−35.8%).

Measure

The PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) is a self-report questionnaire comprising 17 items corresponding to the 17 DSM-IV symptoms for PTSD. Two versions of the PCL for DSM-IV are the PCL-M, used to assess symptoms related to a military trauma, and the civilian version (PCL-C), used generically to apply to any traumatic event. Respondents are instructed to specify the extent to which they have been bothered by each symptom during the past month on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = notat all to 5 = extremely. Weathers et al. (1993) reported a full-scale internal consistency reliability (coefficient a) for the PCL-M of .97 and test-retest reliability (2- to 3-day interval) of .96. Palmieri et al. (2007) computed coefficient a for the four PTSD symptom clusters of the PCL-C as .88 for reexperiencing, .77 for avoidance, .85 for emotional numbing, and .76 for hyperarousal. The PCL scales are widely used self-report measures of PTSD symptom severity and have shown convergent validity with other recognized PTSD measures, including Keane, Caddell, and Taylor’s (1988) Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (r = .82 to .93; Palmieri et al., 2007; Weathers et al., 1993) and Blake et al.’s (1995) Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (r = .78 to .93; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Keen, Kutter, Niles, & Krinsley, 2008; Palmieri et al., 2007). In the current study, participants were asked to report symptoms during the past 2 weeks. Coefficient a for the modified PCL-M collected at baseline in the current sample was .94.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the four symptom clusters of reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal and for total modified PCL-M score first were computed. Data then were analyzed using multilevel regression, with Level 1 being the repeated assessments within an individual and Level 2 being participants. The data for the current study displayed no discernable growth trend or change trajectory, and the focus was on chronic fluctuation consisting of increases and decreases from occasion to occasion.

To model fluctuation, we applied a method for intensively measured data that combines time series analysis with multilevel random coefficients regression (Rovine & Walls, 2006). This cross-lagged autoregressive approach allowed us to ask whether an individual’s status on an outcome of interest, score on a symptom cluster at occasion t, varied as a function of the individual’s status on the score of a different symptom cluster at a prior occasion (t – 1 [2-week interval]). Accordingly, the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects were allowed to vary randomly across individuals. In this case, the multilevel models estimated the within-person influence of prior scores on each of four PTSD symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, emotional numbing, and hyperarousal) on subsequent levels of the other symptom clusters. The lagged series were centered on participants (Level 2) to account for possible autocorrelation. The resulting parameter estimates reflect within-person relationships among variables and indicate the degree to which the prior observation predicts the later observation (Rovine & Walls, 2006).

The data fulfilled the multilevel design requirements suggested by Kreft and de Leeuw (1998), in which a minimum of 30 Level-2 units (participants) contain at least 30 Level-1 units (within-person assessments). The large number of assessments per participant also tends to increase power (Raudenbush & Liu, 2001). Using a conservative approach for estimating between-person variance components recommended for multilevel regression (Browne & Draper, 2000), we employed restricted maximum likelihood procedures via hierarchical linear modeling software (Version 6.0; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2004). This approach can accommodate unbalanced data sets in which the number of repeated observations is not uniform across individual cases. The present study data were treated as meeting the missing at random assumption as described by Little and Rubin (1987). Missing observations on modified PCL-M symptom clusters were deleted listwise at the intraindividual level. Effect sizes were computed as partial correlation coefficients and interpreted using Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for small (.10 to .30), medium (.30 to .50), and large (> .50) effects.

Results

Table 1 presents the overall within-person M, SD, and range for the four PTSD symptom clusters, total PTSD score as measured by the modified PCL-M across all assessments, and the same data for number of assessments. Consideration of the SDs in relation to the Ms of the repeatedly assessed variables suggests roughly symmetric and unimodal distributions with absence of skew, which satisfy the assumptions for maximum likelihood estimation. Table 2 contains the results of the 12 cross-lagged autoregressive analyses based on a 2-week interval between observations. As shown there, all significant cross-lagged coefficients are positive, indicating that increases (and decreases) in prior symptom expression yielded increases (and decreases) in subsequent symptom expression. As hypothesized and shown in the last three entries of Table 2, antecedent hyperarousal significantly predicted all of the other subsequent symptom clusters (reexperiencing, avoidance, and emotional numbing), and it was the only symptom cluster to do so. All three of these effects (rs = .45, .36, and .40, respectively) were of medium magnitude using Cohen’s (1988) standards. An exploratory analysis of the associations among the symptom clusters with a 4-week interval yielded a significant association between hyperarousal and subsequent avoidance symptoms (r = .46), thus attesting to the potency and persistence of hyperarousal over a more extended period and suggesting further research related to the confluence of timing and mechanisms for these two aspects of PTSD. Findings from these analyses may be obtained from the corresponding author.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Modified PCL-M Symptom Clusters, Total Score, and Number of Assessments Pooled Over Participant and Assessment

| Variable | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reexperiencing | 16.47 | 4.89 | 5 | 25 |

| Avoidance | 7.40 | 2.03 | 2 | 10 |

| Emotional numbing | 16.45 | 5.33 | 5 | 25 |

| Hyperarousal | 18.73 | 4.57 | 5 | 25 |

| Total | 59.05 | 15.44 | 19 | 85 |

| Number of assessments | 39.74 | 10.34 | 13 | 52 |

Note. The PCL-M testing schedule was modified to every 2 weeks instead of the standard 4 weeks. PCL-M = PTSD Checklist-Military version.

Table 2.

Cross-Lagged Within-Person Associations of Prior Modified PCL-M Clusters With Later Clusters

| Predictor (t - 1) | Outcome (t) | Coefficient | SE | t | rp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reexperiencing | Avoidance | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.99 | .17 |

| Reexperiencing | Emotional numbing | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | .01 |

| Reexperiencing | Hyperarousal | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.06a | .34 |

| Avoidance | Reexperiencing | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1.03 | .18 |

| Avoidance | Emotional numbing | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.28 | .05 |

| Avoidance | Hyperarousal | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.66 | .28 |

| Emotional numbing | Reexperiencing | 0.14 | 0.05 | 2.78a | .44 |

| Emotional numbing | Avoidance | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.51a | .40 |

| Emotional numbing | Hyperarousal | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.11 | .19 |

| Hyperarousal | Reexperiencing | 0.14 | 0.05 | 2.86a | .45 |

| Hyperarousal | Avoidance | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.19a | .36 |

| Hyperarousal | Emotional numbing | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.48a | .40 |

Note. N = 34. Regression coefficients are expressed in an unstandardized metric. The PCL-M testing schedule was modified to every 2 weeks instead of the standard 4 weeks. (t - 1) and (t) = prior and later assessment occasion, respectively (2-week interval); rp = partial correlation coefficient as estimate of effect size; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist-Military version.

p < .05.

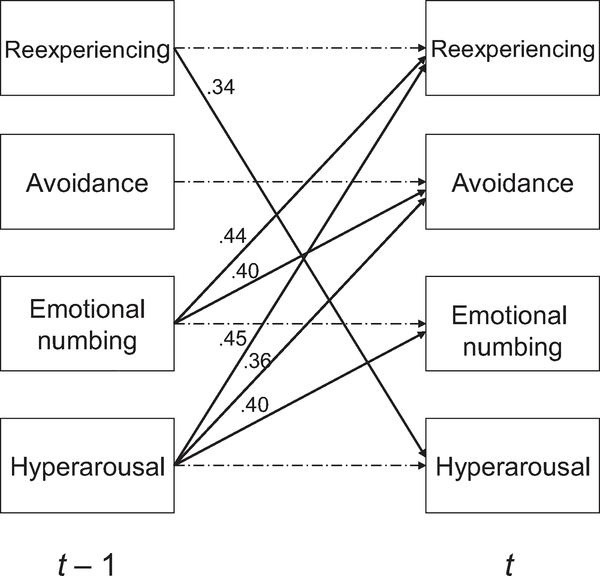

In addition, emotional numbing predicted later reexperiencing and avoidance, and reexperiencing predicted later hyperarousal, again with medium effect sizes (rs = .44, .40, and .34, respectively). Prior reexperiencing was the only symptom cluster to influence subsequent hyperarousal over time, thereby resulting in a reciprocal relationship between these two symptom clusters. Figure 1 summarizes the findings and graphically portrays the possible dynamic mechanisms by which PTSD clusters operate to provoke symptom chronicity.

Figure 1.

Results of analyses of within-person temporal relationships among PTSD symptom clusters across 2-week intervals (N = 34). Solid arrows indicate significant (p < .05) associations between antecedent (t – 1) and subsequent (t) symptom clusters. Dashed arrows represent control for autoregression. Partial correlation coefficients are provided as estimates of effect sizes.

Discussion

The present study represented the first prospective investigation of the dynamic within-person interplay among PTSD symptom clusters over time in chronic PTSD of which we are aware. We examined intrapersonal fluctuations in symptom clusters assessed at 2-week intervals over 2 years in a small sample of Vietnam veterans with chronic combat-related PTSD. Findings indicated that hyperarousal was the only PTSD symptom cluster to predict subsequent fluctuations in all three other clusters across 2-week intervals. The current study found that many years after trauma exposure, chronic PTSD is characterized by ongoing within-person fluctuations in hyperarousal symptoms that influence subsequent changes in reexperiencing, avoidance, and emotional numbing symptoms. The confluence of these findings with those from studies of populations that differ in terms of time since trauma, trauma type, and age (Marshall et al., 2006; Schell et al., 2004; Solomon et al., 2009) provides strong evidence for the preeminence of hyperarousal as a maintenance factor that influences subsequent symptom expression in PTSD.

Perhaps even more revealing in these findings is the pattern of associations across all four symptom clusters (see Figure 1) as a viable explanation for chronic PTSD. Beyond the interesting and affirming results related to hyperarousal’s prominence is the observation that reexperiencing in turn predicts hyperarousal, thus establishing the potential for an internal, intrapersonal mechanism for the maintenance of PTSD over time. The hyperarousal-reexperiencing bidirectional relationship observed in the present study is distinct from prior research on emerging PTSD (MacDonald et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2006; Schell et al., 2004; Solomon et al., 2009) and resembles the strong association between these symptom dimensions observed among Vietnam veterans and noted as a possible “hallmark” of combat-related chronic PTSD (King et al., 1998, p. 94). Moreover, hyperarousal influences later emotional numbing, which goes on to influence later reexperiencing, reinforcing the possibility of a chaining of symptoms (hyperarousal → emotional numbing → reexperiencing → hyperarousal) that augments or supplements the more direct reciprocal association (hyperarousal → reexperiencing → hyperarousal). Of course, exacerbations (or diminutions) in hyperarousal also portend similar effects upon avoidance, but the data do not support any impact of avoidance on subsequent symptom clusters.

These results suggest that treatments that directly target hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD, thereby interrupting the chain of symptom maintenance, may be powerful in the treatment of chronic PTSD, and evidence is accruing to support this notion. For example, interventions targeting sleep disruption (e.g., Margolies, Rybarczyk, Vrana, Leszczyszyn, & Lynch, 2013; Raskind et al., 2013) have been efficacious in reducing PTSD symptoms. Likewise, simple arousal-reducing relaxation used as a placebo control showed surprising efficacy with large effect sizes in a recent randomized trial of individuals with PTSD (Markowitz et al., 2015). Mindfulness meditation has shown promise in ameliorating the symptoms of PTSD (Bormann, Thorp, Wetherell, Golshan, & Lang, 2013; Niles et al., 2012) in veterans with longstanding symptoms. Yoga for PTSD has been shown to target hyperarousal symptoms in particular (Staples, Hamilton, & Uddo, 2014) and has been efficacious in reducing overall symptoms (van der Kolk et al., 2014). Furthermore, exposure treatments that indirectly target hyperarousal through habituation and extinction of fear responses have proven efficacy in the treatment of PTSD (Cahill, Rothbaum, Resick, & Follette, 2009).

These findings further indicate that reductions in emotional numbing symptoms can also disrupt the chain of PTSD symptom maintenance. Exposure therapies (e.g., Foa et al., 2005; Schnurr et al., 2007) and trauma-processing treatments (e.g., Monson et al., 2006) that activate and encourage expression of emotion have extensive empirical support. It is important to note that restricted range of affect is the only symptom in the DSM-IV emotional numbing cluster that directly pertains to constricted affect. Other symptoms (e.g., reduced interest in activities, feelings of detachment) may be better classified as dysphoria. Thus, the current findings also suggest that treatments aimed at dysphoria or depression symptoms may halt the cycle of PTSD symptom maintenance. Indeed, cognitive restructuring, first utilized widely in cognitive therapy for depression (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), is a large component of cognitive processing therapy, which has substantial empirical support in the treatment of PTSD (Chard, Schuster, & Resick, 2012). Thus, in addition to hyperarousal, emotional numbing and dysphoria should continue to be a focus in PTSD treatment development.

It is important to consider this study’s methodological limitations. First, the current study utilized a small sample of 34 male Vietnam combat veterans, not all of whom had current PTSD, and these results need to be replicated with other veteran or military populations or with individuals with PTSD related to other types of trauma. In addition, although this study used a prospective design to assess symptoms over 2 years, participants were asked to report retrospectively on their PTSD symptoms during the previous 2-week interval. Potential reporting inaccuracies related to both retrospective recall and self-report are therefore duly noted. The 2-week intervals between assessments were chosen for practical rather than theoretical reasons, as the optimal time interval to examine temporal dynamics of PTSD symptom clusters over time is unknown. Future research utilizing new technologies of ecological momentary assessment could allow assessments as frequent as several times per day. The use of DSM-IV symptom reports rather than DSM-5 did not allow examination of the role of negative trauma-related cognitions and emotions, such as guilt and shame. Future investigations of DSM-5 symptoms over time could elucidate the role of these important symptoms in the maintenance of PTSD. Nevertheless, it should be noted that these data constitute a rare and valuable view of chronic PTSD over time.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs CSR&D grant (Susan Doron-LaMarca, Principal Investigator) and Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant (Barbara L. Niles, Principal Investigator), and by National Institute of Mental Health grants R03MH77907 (Susan Doron-LaMarca, Principal Investigator), and R01MH68626 (Daniel W. King, Principal Investigator), and by funding from the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Behavioral Science Division. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs or the United States Government. The authors gratefully acknowledge the advice on analytic method offered by Ted Walls and John Nesselroade. Finally, we wish to thank the military veterans who participated in this research for their generous contributions.

References

- Abt Associates. (2014). Initial findings: National Vietnam veteran study reveals long-term course of PTSD and link to chronic health conditions. Retrieved from http://abtassociates.com/newsreleases/2014/initial-findings-national-vietnam-veteran-study-re.aspx

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, & Emery G (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, & Keane TM (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8, 75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, & Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Westphal M, & Mancini AD (2011). Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 511–535. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann JE, Thorp SR, Wetherell JL, Golshan S, & Lang AJ (2013). Meditation-based mantram intervention for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized trial. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, 259–267. doi: 10.1037/a0027522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Reboussin BA, Anthony JC, & Storr CL (2005). The structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: Latent class analysis in 2 community samples. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1343–1351. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne WJ, & Draper D (2000). Implementation and performance issues in the Bayesian and likelihood fitting of multilevel models. Computational Statistics, 15, 391–420. doi: 10.1007/s001800000041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, & Follette VM (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults In Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, & Cohen JA (Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD (2nd ed., pp. 139–222). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chard KM, Schuster JL, & Resick PA (2012). Empirically supported psychological treatments: Cognitive processing (pp. 439–448). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coronas R, Gallardo O, Moreno MJ, Suarez D, García-Parés G, & Menchon JM (2011). Heart rate measured in the acute aftermath of trauma can predict post-traumatic stress disorder: A prospective study in motor vehicle accident survivors. European Psychiatry, 26, 508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuHamel KN, Ostrof J, Ashman T, Winkel G, Mundy EA, Keane TM, Redd W (2004). Construct validity of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist in cancer survivors: Analyses based on two samples. Psychological Assessment, 16, 255–266. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Palmieri PA, Biehn TL, Frueh BC, & Magruder KM (2010). Posttraumatic stress disorder’s frequency and intensity ratings are associated with factor structure differences in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 22, 723–728. doi: 10.1037/a0020643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SA, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, & Yadin E (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SA, Brandes D, Peri T, & Shalev AY (1999). Predictors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: A prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 353–359. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, & Rosen RC (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: Epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychological Services, 9, 361–382. doi: 10.1037/a0027649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, & Koffman RL (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Caddell JM, & Taylor KL, (1988). Mississippi Scale for Combat-related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Three studies in reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 85–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen SM, Kutter CJ, Niles BL, & Krinsley KE (2008). Psychometric properties of PTSD Checklist in sample of male veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 45, 465–474. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.09.0138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, & Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DW,Leskin GA, King LA, & Weathers FW (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: Evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Assessment, 10, 90–96. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Keane TM, & Fairbank JA (1999). Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans: Risk-factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 164–170. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.1.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, King DW, Salgado DM, & Shalev AY (2003). Contemporary longitudinal methods for the study of trauma and stress. CNS Spectrums, 8, 686–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, & Figueredo AJ (2004). Change in cognitive mediators of rape’s impact on psychosocial health across 2 years of recovery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 1063–1072. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, & deLeeuw J (1998). Introducing multilevel modeling. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald HZ, Proctor SP, Heeren T, & Vasterling JJ (2013). Associations of postdeployment PTSD symptoms with predeployment symptoms in Iraq-deployed Army soldiers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, 470–476. doi: 10.1037/a0029010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolies SO, Rybarczyk B, Vrana SR, Leszczyszyn DJ, & Lynch J (2013). Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for insomnia and nightmares in Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 1026–1042. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, Petkova E, Neria Y, VanMeter PE, Zhao Y, Hembree E, ... Marshall RD (2015). Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 430–440. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmar CR, Schlenger W, Henn-Haase C, Qian M, Purchia E, Li M, ... Kulka RA (2015). Course of posttraumatic stress disorder 40 years after the Vietnam war: Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Schell TL, Glynn SM, & Shetty V (2006). The role of hyperarousal in the manifestation of posttraumatic psychological distress following injury. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 624–628. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Brown TA, Kaloupek DG, & Keane TM (2010). An evaluation of competing models for the structure of PTSD symptoms using external measures of comorbidity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 631–638. doi: 10.1002/jts.20559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, & Stevens SP (2006). Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 898–907. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Taft CT, & Fredman SJ (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles BL, Klunk-Gillis J, Ryngala DJ, Silberbogen AK, Paysnick A, & Wolf EJ (2012). Comparing mindfulness and psychoeducation treatments for combat-related PTSD using a telehealth approach. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 538–547. doi: 10.1037/a0026161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole BI, Catts SV, Outram S, Pierse KR, & Cockburn J (2009). The physical and mental health of Australian Vietnam veterans 3 decades after the war and its relation to military service, combat and post-traumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 318–330. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Weathers FW, Difede J, & King DW (2007). Confirmatory factor analysis of the PTSD Checklist and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale in disaster workers exposed to the World Trade Center Ground Zero. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 329–341. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, Hoff DJ, Hart K, Holmes H, ... Peskind ER (2013). A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1003–1010. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, & Congdon R, & Toit du(2004). HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Liu X (2001). Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods, 6,387–401. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.6.4.387-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovine MJ, & Walls TA (2006). Multilevel autoregressive modeling of interindividual differences in the stability of a process In Walls TA & Schafer JL (Eds.), Models for intensive longitudinal data (pp. 124–147). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson K, & Andrews G (2006). Common mental disorders in the workforce. Recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoca E, & Rosenheck R (2000). The civilian labor market experiences of Vietnam-era veterans: The influence of psychiatric disorders. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 3, 199–207. doi: 10.1002/mhp.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN, & Jaycox LH (2004). All symptoms are not created equal: The prominent role of hyperarousal in the natural course of posttraumatic psychological distress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 189–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, ... Bernardy, N. (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297, 820–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, & Green BL (2004). Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10723-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Sengupta A, & Waelde LC (2003). A descriptive analysis of PTSD chronicity in Vietnam veterans. Journal ofTraumatic Stress, 16, 545–553. doi: 10.1023/B:J0TS.0000004077.22408.cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, & Pitman RK (1998). Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 630–637. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms LJ, Watson D, & Doebbeling BN (2002). Confirmatory factor analyses of posttraumatic stress symptoms in deployed and nondeployed veterans of the Gulf War. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 637–647. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Horesh D, & Ein-Dor T (2009). The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters among war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 837–843. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples JK, Hamilton MF, & Uddo M (2014). A yoga program for the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. Military Medicine, 178, 854–860. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suendermann O, Ehlers A, Boellinghaus I, Gamer M, & Glucksman E (2010). Early heart rate responses to standardized trauma-related pictures predict posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 301–308. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d07db8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm JA, Panuzio J, & Proctor SP (2008). An examination of family adjustment among Operation Desert Storm veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 648–656. doi: 10.1037/a0012576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KE, Vasterling JJ, Benotsch EG, Brailey K, Constans J, Uddo M, & Sutker PB (2004). Early symptom predictors of chronic distress in Gulf War veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192, 146–152. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000110286.10445.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, & Davidson JRT (2001). Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: The first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety, 13, 132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993, October). The PTSD Checklist: Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- White J, Pearce J, Morrison S, Dunstan F, Bisson JI, & Fone DL (2014). Risk of post-traumatic stress disorder following traumatic events in a community sample. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24, 249–257. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk B, Stone L, West J, Rhodes A, Emerson D, Suvak M, & Spinazzola J (2014). Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75, 559–565. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]