Abstract

Purpose of review

This review provides an updated overview on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of biological therapies in IBD. We examine the data behind TDM for the anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents, vedolizumab and ustekinumab, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In addition, we discuss reactive vs. proactive TDM.

Recent findings

There is a positive correlation between biologic drug concentrations and favorable therapeutic outcomes in IBD, although the majority of data refer to anti-TNF therapy. Reactive TDM has rationalized the management of patients with IBD with loss of response to biological therapy. Moreover, reactive TDM of infliximab has been proven to be more cost-effective when compared to empiric dose optimization. Preliminary data suggest that proactive TDM of infliximab and adalimumab applied in patients with clinical response/remission is associated with better therapeutic outcomes compared to standard of care (empiric treatment and/or reactive TDM).

Summary

For all biologics in IBD, there is a positive correlation between drug concentrations and favorable therapeutic outcomes. Reactive TDM is the new standard of care for optimizing biologic therapies in IBD, while recent data suggest an important role of proactive TDM for optimizing anti-TNF therapy in IBD.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, immunogenicity, biologics, infliximab

INTRODUCTION

Biologic agents, such as infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab [anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy], vedolizumab (α₄β₇ integrin inhibitor) and ustekinumab (interleukin 12/23 inhibitor) have revolutionized the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [1]. Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are primary non-responders and have no clinical benefit following induction therapy. Moreover, up to half of the patients with an initial clinical benefit have a secondary loss of response (SLR) and need to intensify or even discontinue therapy. Both primary non-response (PNR) and SLR can be explained by pharmacokinetic (PK) problems, characterized by undetectable or subtherapeutic drug concentrations with or without the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADA), or a mechanistic failure [2–5].

Numerous studies suggest that higher serum drug concentrations are associated with a higher rate of favorable therapeutic outcomes including clinical, biochemical [normalization of C-reactive protein (CRP) or fecal calprotectin (FC)], endoscopic, histologic or composite remission [6–48]. Based on these studies, therapeutic drug concentration thresholds to target have been proposed, although clinically relevant cut-offs can vary depending on IBD phenotype, therapeutic outcome and the TDM assay used (Table 1). For example, to achieve more stringent outcomes, such as mucosal healing, higher drug concentrations are needed compared to clinical response/remission (Table 1). On the other hand, ADA and undetectable or low drug concentrations have been associated with treatment failure and drug discontinuation [49–57].

Table 1.

Biological drug concentration thresholds to target associated with favorable therapeutic outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease.

| Biological drug | Treatment time point | Suggested drug concentration threshold for clinical response/remission (μg/ml) | Suggested drug concentration threshold for mucosal healing (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab | Induction (week 2) | ≥20 | ≥25 |

| Induction (week 6) | ≥10 | N/A | |

| Post-induction (week 14) | ≥3 | ≥7 | |

| Maintenance | ≥3 | ≥7 | |

| Adalimumab | Post-induction (week 14) | ≥5 | ≥7 |

| Maintenance | ≥3 | ≥8 | |

| Certolizumab pegol | Post-induction (week 6) | ≥32 | N/A |

| Maintenance | ≥15 | N/A | |

| Golimumab | Post-induction (week 6) | ≥2.5 | N/A |

| Maintenance | ≥1 | N/A | |

| Vedolizumab | Induction (week 2) | ≥28 | N/A |

| Induction (week 6) | ≥24 | N/A | |

| Post-induction (week 14) | ≥15 | ≥17 | |

| Maintenance | ≥12 | ≥14 | |

| Ustekinumab | Post-induction (week 8) | ≥3.5 | N/A |

| Maintenance | ≥1 | ≥4.5 |

N/A: not applicable, due to paucity of data.

Reactive therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of biologics applied in patients with a disease flare or an infusion reaction has rationalized the management of SLR [58–63]. Moreover, reactive TDM and has been proven to be more cost-effective when compared to empiric infliximab dose optimization [64–67]. Additionally, recently published data demonstrate that proactive TDM performed with the goal of attaining adequate drug concentration thresholds can effectively optimize anti-TNF therapy leading to better therapeutic outcomes when compared to standard of care (empiric dose escalation and/or reactive TDM) [68**–71]. Although many IBD specialists are already utilizing this therapeutic strategy in clinical practice TDM, proactive TDM is not yet considered standard of care [72–77].

This review will describe the role of TDM in optimizing biologic therapies in IBD and will focus on recent data regarding both reactive and proactive TDM as well as exposure-outcome relationship studies.

Therapeutic drug monitoring for every drug?

Numerous exposure-therapeutic outcomes studies highlight the importance of TDM for optimizing biological therapy in IBD. These studies emphasize that higher concentrations are needed during the induction phase, and higher concentrations are associated with better outcomes.

Infliximab

Several studies have shown that higher infliximab concentrations during both induction and maintenance therapy are associated with favorable therapeutic outcomes in both CD and UC (Table 1) [6–23]. The optimal drug therapeutic threshold to target during induction has not been clearly defined, although higher concentrations than during maintenance treatment are typically required. A post-hoc analysis of the TAILORIX (Drug-concentration versus Symptom-driven Dose Adaptation of Infliximab in patients with active Crohn’s disease) randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that higher infliximab concentrations at week 2 (≥23.1 μg/mL) and 6 (≥10 μg/mL) are associated with early endoscopic remission at week 12 [9]. A single-center retrospective study of patients with UC identified infliximab concentration thresholds of 28.3 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml at week 2 and 6 to be associated with short-term mucosal healing [11]. On the other hand, a recent retrospective observational case-control study found that infliximab concentrations <6.8 μg/mL and antibodies to infliximab (ATI) >4.3 μg/mL-eq before the second infusion are associated with PNR, especially among patients with CD [54].

Regarding maintenance therapy, current data suggest that infliximab trough concentrations >3 μg/ml are associated with clinical response/remission, although for more rigorous therapeutic outcomes (endoscopic, histologic, and fistula healing), higher drug concentration are needed (Table 1). For example, a recent single-center retrospective study of patients with CD showed that infliximab concentrations >9.7 and >9.8 μg/mL were associated with endoscopic and histologic remission, respectively [10]. Another study in UC identified infliximab trough concentrations >7.5 to be associated with endoscopic healing and concentrations >10.5 μg/mL to be associated with histologic healing [12]. Moreover, a multi-center inception pediatric cohort study identified a post-induction (week 14) drug concentration threshold of 12.7 ug/mL to best predict healing of fistulizing perianal CD at week 24 [18]. Another single-center cross-sectional study found that infliximab concentrations ≥10.1 μg/mL were associated with fistula healing in patients with perianal CD [16].

Adalimumab

Several studies have shown that higher adalimumab concentrations during both post-induction (week 4) and maintenance therapy are associated with improved therapeutic outcomes in both CD and UC (Table 1) [21–30]. These studies suggest an optimal therapeutic trough concentration threshold to target during maintenance therapy of >5 μg/ml for clinical response/remission, but for more rigorous therapeutic outcomes, higher drug concentrations are needed. For example, one recent retrospective multi-center study identified adalimumab concentration cut-offs of 11.8, 12, and 12.2 μg/mL in CD and 10.5, 16.2, and 16.2 μg/mL in UC to stratify those with or without biochemical, endoscopic, or histologic remission, respectively. [24]. On the other hand, patients with low drug concentrations at week 4 (<8.3 μg/mL) were found to be at significantly higher risk of having ADA by week 12 (46.7% vs. 13%, p=0.009). These patients also had a significantly higher need of dose escalation (p<0.001) and less frequently experienced sustained clinical benefit due to PNR or SLR (p=0.02) [55*]. Furthermore, a recent prospective study or 98 CD patients treated with adalimumab showed that ADA are strongly associated with PNR [odds ratio (OR) = 5.4, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–17.8, p = 0.005]. In this study, 32% of patients developed ADA as early as week 2 and 55% of patients developed ADA as early as week 14 [53*]. These studies highlight the potential importance of early (proactive) TDM of adalimumab to guide dose optimization for preventing immunogenicity and attaining better long-term outcomes in IBD.

Certolizumab pegol

Although there are only limited data, current evidence from exposure-response relationship studies show that higher certolizumab pegol concentrations are associated with better therapeutic outcomes in CD (Table 1) [31, 32].

Golimumab

Although there are only limited data, current evidence from exposure-response relationship studies demonstrate that higher golimumab concentrations are associated with better therapeutic outcomes in UC (Table 1) [33, 34].

Vedolizumab

Several studies have shown that higher vedolizumab concentrations during both induction and maintenance therapy are associated with improved therapeutic outcomes in both CD and UC (Table 1) [35–45]. A post hoc analysis of the GEMINI 1 (Vedolizumab in Patients with Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis), GEMINI 2 (Vedolizumab in Patients with Moderate to Severe Crohn’s Disease) and GEMINI 3 (Vedolizumab in Patients with Moderate to Severe Crohn’s Disease) RCTs demonstrated that higher vedolizumab serum concentrations at week 6 were associated with higher clinical remission rates after induction therapy (at week 14) in patients with moderately to severely active IBD. Trough concentration increases from Quartile (Q)1 (≤17.1 μg/ml) to Q4 (>35.7–140 μg/ml) in UC and from Q1 (≤16.0 μg/ml) to Q4 (> 33.7–177 μg/ml) in CD resulted in an absolute increase in remission rate of approximately 31% and 14%, respectively [38]. A post hoc analysis of the GEMINI 1 RCT demonstrated that UC patients in the higher steady-state vedolizumab trough concentration quartiles had greater deep remission rates at week 52 compared to those in the lowest quartile (Q1<9.26 μg/mL to Q4 >41 μg/mL) or those who received placebo [44]. A propensity-score-based case-matching analysis using data from GEMINI 1 identified vedolizumab concentrations thresholds of 37.1 (week 6), 18.4 (week 14) and 12.7 μg/mL (steady state) to be associated with clinical remission at week 52 [45].

Ustekinumab

Although there are only limited data, current evidence from exposure-response relationship studies show that higher ustekinumab concentrations are associated with better therapeutic outcomes (Table 1) [46–48]. A recent prospective, open-label cohort study showed that ustekinumab concentrations ≥4.2μg/mL at week 8 were associated with a 50% decrease in FC. Week 16 ustekinumab concentrations ≥2.3μg/mL and week 24 concentrations ≥1.9μg/mL were associated with endoscopic response at week 24 [48].

Therapeutic drug monitoring for every patient?

TDM is efficacious for optimizing anti-TNF therapy in IBD. The data is stronger for reactive than proactive TDM, and data for other biologics is lacking. Two large retrospective single-center studies did show that the lack of any TDM was associated with infliximab discontinuation [60, 63] and frequent intestinal surgeries [63].

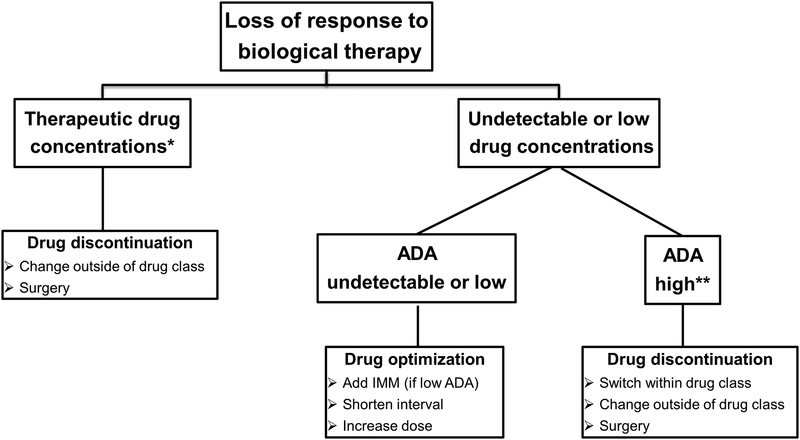

Reactive therapeutic drug monitoring

Reactive TDM can better explain and therefore manage SLR to anti-TNF therapy in IBD [58, 60–62]. It can identify patients who will respond to more drug (dose escalation) and those that would benefit from another strategy. Yanai et al. showed that at the time of SLR, infliximab concentrations >3.8 μg/mL and adalimumab concentrations >4.5 μg/mL identified patients who appeared to have a mechanistic failure and benefited more from a switch to a non-anti-TNF than dose escalation or switching to another anti-TNF [58]. Similarly, Roblin et al. demonstrated that at the time of SLR, adalimumab concentrations < 4.9 μg/mL without ADA strongly predicted response to dose intensification, whereas patients with antibodies did better when switched to another anti-TNF. Adalimumab concentrations >4.9 μg/mL were associated with failure of a second anti-TNF agent, identifying a group of patients mechanistically failing adalimumab who would require a non-anti-TNF agent [61]. In addition to better directing care, reactive TDM is also more cost-effective when compared to empiric infliximab dose optimization [58–67]. An observational cohort study showed that reactive TDM was associated with higher endoscopic remission and clinical response when compared to empiric infliximab optimization [59]. The same study showed that post-adjustment infliximab concentrations >4.5 μg/mL and ATI <3.3 U/mL were associated with endoscopic remission [59]. A suggested treatment algorithm for using reactive testing to infliximab is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Reactive TDM algorithm of IBD patients on biological therapy.

*For relative values refer to Tables 1; **ATI >8 μg/mL-eq for ELISA and >10 U/ml for HMSA.

ADA: anti-drug antibody; IMM: immunomodulators; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ATI: anti-infliximab antibodies; HMSA: homogeneous mobility shift assay; TDM: therapeutic drug monitoring; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Proactive therapeutic drug monitoring

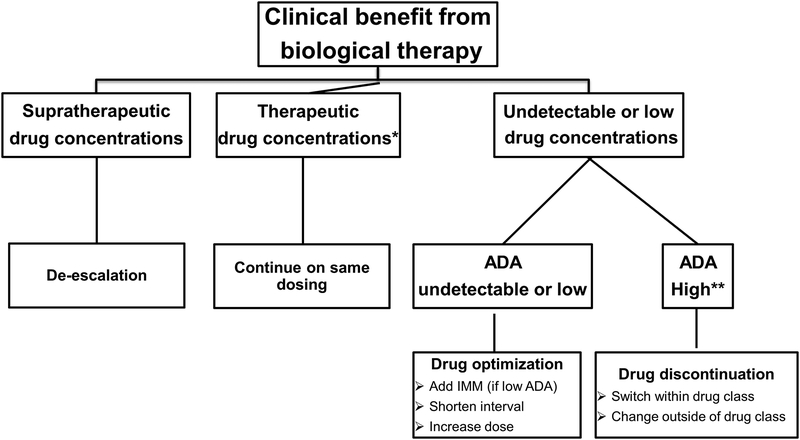

Proactive TDM is the measurement of trough concentrations and antibody levels with the goal of optimizing drug concentrations to achieve a threshold drug concentration. The aim of proactive TDM is to improve response rates and prevent secondary loss of response by targeting drug concentrations which are considered to be in the optimal therapeutic range. There is recent data that suggests that proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy is associated with better therapeutic outcomes when compared to empiric dose escalation or reactive TDM (currently the standard of care). The landmark TAXIT (Trough Level Adapted Infliximab Treatment) RCT, although it failed to meet its primary outcome due to some methodological issues, demonstrated that proactive TDM of infliximab was associated with a lower frequency of undetectable drug concentrations and a lower risk of relapse compared to clinically-based dosing. Additionally, in patients with CD and low infliximab concentrations, a one-time dose optimization improved clinical remission rates and CRP [68**]. More recently, proactive compared to reactive TDM of infliximab was associated with less treatment failure, need for IBD-related surgery or hospitalization, risk of ATI and serious infusion reactions [71]. Additionally, another study demonstrated that in patients who underwent reactive TDM, subsequent proactive TDM of infliximab was associated with greater drug persistence and fewer IBD-related hospitalizations than reactive TDM alone [69]. Recently, a multi-center retrospective study showed that at least one proactive TDM of adalimumab was independently associated with a reduced risk for treatment failure when compared to standard of care [hazard ratio (HR): 0.4; 95%CI: 0.2–0.9; p=0.022) [70*].

Another potential benefit of proactive TDM is that de-escalation could be cost savings, although data are still sparse [68, 78]. This strategy is also safe as an observational single-center study including IBD patients in clinical and biological remission with infliximab concentrations >7 mg/L who de-escalated therapy showed that concentration-based de-escalation was associated with a decreased risk of relapse (HR: 0.45, p=0.024) [79]. However, as there are only limited data on what is the therapeutic window of infliximab and current data in IBD do not demonstrate that higher anti-TNF therapy concentrations associated with increased toxicity, it may be reasonable to continue current dosing, especially in patients who had been very ill, despite high drug concentrations [80]. Nevertheless, physicians must follow the patients closely as a study in spondyloarthritis showed that the risk of an infection episode was significantly increased in the highest quartile of the mean of the last 3 trough infliximab concentrations (>20.3 μg/mL) (HR: 2.65, 95%CI: 1.14–6.14, p=0.023) [81]. In our practice, we typically dose de-escalate for infliximab concentrations that are consistently greater than 15 mg/L.

Furthermore, a recent retrospective cohort study of 83 IBD patients showed that drug durability did not differ between patients on infliximab monotherapy dosed based on proactive TDM and patients receiving combination therapy with an immunomodulator [82]. This concept of ‘optimized monotherapy’, or proactive TDM with a biologic alone, is further supported by a recent post-hoc analysis of the SONIC (Study of Biologic and Immunomodulator Naive Patients in Crohn Disease) RCT. This study stratified patients by infliximab concentration quartiles and demonstrated that patients had similar outcomes irrespective of concomitant azathioprine [83**]. A treatment algorithm for using proactive testing for infliximab is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Proactive TDM algorithm of IBD patients on biological therapy.

*For relative values refer to Tables 1; **ATI >8 μg/mL-eq for ELISA and >10 U/ml for HMSA.

ADA: anti-drug antibody; IMM: immunomodulators; ATI: anti-infliximab antibodies; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HMSA: homogeneous mobility shift assay; TDM: therapeutic drug monitoring; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Though most of the data for proactive TDM is during the maintenance phase, it is probably most important during the induction phase when the disease is active and drug clearance is greatest. As noted above, drug concentrations need to be higher during induction and adequate drug concentrations during induction are associated with better short and long-term outcomes. The recent TAILORIX trial attempted to look at symptom-driven dose adaptation of infliximab vs. symptoms plus biomarkers, and infliximab drug concentrations in CD. Unfortunately, due to the design, little can be said about the role of TDM aside from higher infliximab concentrations during induction therapy at week 2 and 6 are associated with early endoscopic remission at week 12. The primary endpoint, sustained clinical remission with no endoscopic ulceration, was not different between the groups. However, two of the groups were only able to dose escalate based on clinical symptoms and biomarker elevation or trough concentrations whereas the control group was able to dose-escalate based only on clinical symptoms. In fact, in control group, 60% (9/15) of dose escalations based on only on symptoms had normal biomarkers, whereas, 53% (23) of possible dose escalations based on symptoms in interventional arms were avoided as biomarkers were not elevated. Furthermore, only 25–30% of patients were dose escalated based on trough concentrations, less than 50% of the “optimized” groups even attained a sustained infliximab concentration >3μg/ml (less than control group, 60%). Another major drawback was that one had to wait 8 weeks until the next dose to make a change. In the end, trough concentrations were similar in all 3 groups which likely accounts for the similar efficacy outcomes [84].

Therapeutic drug monitoring can also be applied in patients who resume anti-TNF therapy after a prolonged drug holiday (> 6 months) due to relapse. A single-center retrospective study showed that checking infliximab concentrations and ATI after the first dose following a drug holiday was related with improved outcomes. In this setting the absence of ATI was associated with fewer infusion reactions and detectable infliximab trough concentrations were associated with greater long-term response [85].

Conclusion

Numerous studies have demonstrated that higher biologic drug concentrations are associated with higher rates of favorable therapeutic outcomes in IBD, whereas low drug concentrations and anti-drug antibodies lead to primary non-response and secondary loss of response. Reactive TDM has emerged as the new standard of care in IBD, while there is cumulative evidence for the benefits of proactive dose optimization of anti-TNF therapy. While proactive TDM requires more studies, many clinicians caring for IBD patients feel that those patients at highest risk for relapse and surgery should have a post induction TDM, especially with infliximab and adalimumab. Specifically, patients with more severe UC and those with perianal fistulizing CD probably benefit most from TDM during or right after induction in order to optimize maintenance dosing. Although there is recent data that suggests that proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy is associated with better therapeutic outcomes when compared to empiric dose escalation or reactive TDM, before individualized TDM algorithms can be fully applied in real-life clinical practice several barriers need to be addressed. These barriers include the optimal concentration therapeutic window to target, when (peak, intermediate, trough) and how (type of assay) to measure drug concentrations, and out-of-pocket cost of the assays. Future perspectives for maximizing the efficacy of TDM include the development of rapid assays and software decisions support tools incorporating predictive PK models to allow a faster and more accurate drug dose optimization.

KEY POINTS.

Association studies have shown that higher biologic concentrations have been associated with favorable objective therapeutic outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease.

Reactive TDM has rationalized the management of patients with loss of response to biologics and has been proven to be more cost-effective compared to empiric infliximab dose optimization.

Preliminary data suggest that proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy is associated with better therapeutic outcomes when compared to empiric treatment and/or reactive TDM (standard of care).

As there are limited data, more studies are needed to clarify the role of proactive TDM and TDM for biologics other than anti-TNFs in IBD.

Acknowledgements:

None

Conflicts of interest: KP: nothing to disclose; ASC: received a consultancy fee from Janssen, Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Samsung, Arena, Bacainn, EMD Serono, Arsanis, Grifols, Prometheus; and research support from Inform Diagnostics.

Financial support and sponsorship: K.P. is supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant 5T32DK007760–18.

Funding: K.P. is supported by Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant 5T32DK007760–18. The content of this project is solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as: *of special interest, **of outstanding interest.

- 1.Katsanos KH, Papamichael K, Feuerstein JD, et al. Biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: Beyond anti-TNF therapies. Clin Immunol. 2018. March 12 pii: S1521–6616(17)30901–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.03.004. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding NS, Hart A, De Cruz P. Systematic review: predicting and optimising response to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease - algorithm for practical management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:30–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:182–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papamichael K, Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring during induction of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Defining a therapeutic drug window. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1510–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U, Chowers Y. Optimizing anti-TNF treatments in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1296–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornillie F, Hanauer SB, Diamond RH, et al. Postinduction serum infliximab trough level and decrease of C-reactive protein level are associated with durable sustained response to infliximab: a retrospective analysis of the ACCENT I trial. Gut 2014;63:1721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. Factors associated with short- and long-term outcomes of therapy for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreesen E, D’Haens G, Baert F, et al. Infliximab exposure predicts superior endoscopic outcomes in patients with active Crohn’s disease: pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic analysis of TAILORIX. J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12(suppl 1): S063–S064. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papamichael K, Rakowsky S, Rivera C, et al. Association between serum infliximab trough concentrations during maintenance therapy and biochemical, endoscopic, and histologic remission in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:2266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papamichael K, Van Stappen T, Vande Casteele N, et al. Infliximab concentration thresholds during induction therapy are associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:543–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papamichael K, Rakowsky S, Rivera C, et al. Infliximab trough concentrations during maintenance therapy are associated with endoscopic and histologic healing in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:478–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreesen E, Faelens R, Van Assche G, et al. Optimising infliximab induction dosing for patients with ulcerative colitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019. January 11. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13859. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vande Casteele N, Jeyarajah J, et al. Infliximab exposure-response relationship and thresholds associated with endoscopic healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018. October 26 pii: S1542–3565(18)31200-X. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.036. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidov Y, Ungar B, Bar-Yoseph H, et al. Association of induction infliximab levels with clinical response in perianal Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:549–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ, et al. Higher infliximab trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:933–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Hoeve K, Dreesen E, Hoffman I, et al. higher infliximab trough levels are associated with better outcome in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:1316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Matary W, Walters TD, Huynh HQ, et al. Higher postinduction infliximab serum trough levels are associated with healing of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease in Children. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:150–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang B, Choi SY, Choi YO, et al. Infliximab trough levels are associated with mucosal healing during maintenance treatment with infliximab in paediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018. November 19. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy155. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roblin X, Boschetti G, Duru G, Williet N, et al. Distinct thresholds of infliximab trough level are associated with different therapeutic outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:2048–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaparro M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Echarri A, et al. Correlation between anti-tnf serum levels and endoscopic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2018. November 13. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5362-3. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing anti-TNF-α therapy: Serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward MG, Warner B, Unsworth N, et al. Infliximab and adalimumab drug levels in Crohn’s disease: contrasting associations with disease activity and influencing factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:150–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juncadella A, Papamichael K, Vaughn BP, et al. Maintenance adalimumab concentrations are associated with biochemical, endoscopic, and histologic remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018. July 13. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5202-5. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zittan E, Kabakchiev B, Milgrom R, et al. Higher adalimumab drug levels are associated with mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:510–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakase H, Motoya S, Matsumoto T, et al. Significance of measurement of serum trough level and anti-drug antibody of adalimumab as personalised pharmacokinetics in patients with Crohn’s disease: a subanalysis of the DIAMOND trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:873–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe K, Matsumoto T, Hisamatsu T, et al. Clinical and pharmacokinetic factors associated with adalimumab-induced mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:542–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarur AJ, Jain A, Hauenstein SI, et al. Higher adalimumab levels are associated with histologic and endoscopic remission in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plevris N, Lyons M, Jenkinson PW, et al. Higher adalimumab drug levels during maintenance therapy for crohn’s disease are associated with biologic remission. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018;18:1271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papamichael K, Baert F, Tops S, et al. Post-Induction Adalimumab concentration is associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:53–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Allez M, et al. Association between plasma concentrations of certolizumab pegol and endoscopic outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vande Casteele N, Feagan BG, Vermeire S, et al. Exposure-response relationship of certolizumab pegol induction and maintenance therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, Marano CW, et al. Pharmacokinetics and exposure-response relationship of golimumab in patients with moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis: results from phase 2/3 PURSUIT induction and maintenance studies. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Detrez I, Dreesen E, Van Stappen T, et al. Variability in golimumab exposure: a ‘real-life’ observational study in active ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:575–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liefferinckx C, Minsart C, Cremer A, et al. Early vedolizumab trough levels at induction in inflammatory bowel disease patients with treatment failure during maintenance. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. January 21. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001356. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yacoub W, Williet N, Pouillon L, et al. Early vedolizumab trough levels predict mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre prospective observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:906–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Bawardy B, Ramos GP, Willrich MAV, et al. Vedolizumab drug level correlation with clinical remission, biomarker normalization, and mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018. August 24. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy272. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosario M, French JL, Dirks NL, et al. Exposure-efficacy relationships for vedolizumab induction therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ungar B, Kopylov U, Yavzori M, et al. Association of vedolizumab level, anti-drug antibodies, and α4β7 occupancy with response in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dreesen E, Verstockt B, Bian S, et al. Evidence to support monitoring of vedolizumab trough concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1937–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pouillon L, Rousseau H, Busby-Venner et al. vedolizumab trough levels and histological healing during maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2019. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz029 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buer LCT, Moum BA, Cvancarova M, et al. Real world data on effectiveness, safety and therapeutic drug monitoring of vedolizumab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A single center cohort. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019. January 16:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1548646. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williet N, Boschetti G, Fovet M, et al. Association between low trough levels of vedolizumab during induction therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases and need for additional doses within 6 months. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1750–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Panaccione R, et al. Deep remission with vedolizumab in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: a GEMINI 1 post hoc analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018. October 4. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy149. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osterman MT, Rosario M, Lasch K, et al. Vedolizumab exposure levels and clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis: determining the potential for dose optimization. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:408–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, Gasink C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and exposure response relationships of ustekinumab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1660–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Battat R, Kopylov U, Bessissow T, et al. Association between ustekinumab trough concentrations and clinical, biomarker, and endoscopic outcomes in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1427–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verstockt B, Dreesen E, Noman M, et al. Ustekinumab exposure-outcome analysis in Crohn’s disease only in part explains limited endoscopic remission rates. J Crohns Colitis. 2019. January 30. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz008. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baert F, Kondragunta V, Lockton S, et al. Antibodies to adalimumab are associated with future inflammation in Crohn’s patients receiving maintenance adalimumab therapy: a post hoc analysis of the Karmiris trial. Gut 2016;65:1126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brandse JF, Mathot RA, van der Kleij D, et al. Pharmacokinetic features and presence of anti-drug antibodies associate with response to infliximab induction therapy in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papamichael K, Vajravelu RK, Osterman MT, et al. Long-term outcome of infliximab optimization for overcoming immunogenicity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53*.Ungar B, Engel T, Yablecovitch D, et al. Prospective observational evaluation of time-dependency of adalimumab immunogenicity and drug concentrations: The POETIC Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:890–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a prospective observational study showing that antibodies to adalimumab can arise early causing primary non-response.

- 54.Bar-Yoseph H, Levhar N, Selinger L, et al. Early drug and anti-infliximab antibody levels for prediction of primary nonresponse to infliximab therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.Verstockt B, Moors G, Bian S, et al. Influence of early adalimumab serum levels on immunogenicity and long-term outcome of anti-TNF naive Crohn’s disease patients: the usefulness of rapid testing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a single-center observational study suggesting support early monitoring of adalimumab serum levels to guide dose optimisation, which may prevent immunogenicity and influence long-term outcome. Moreover, a novel lateral flow assay for quantitative determination of adalimumab levels, facilitating physicians to optimise therapy immediately at the outpatient clinic was validated.

- 56.Dreesen E, Van Stappen T, Ballet V, et al. Anti-infliximab antibody concentrations can guide treatment intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose clinical response. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bodini G, Giannini EG, Savarino V, et al. Infliximab trough levels and persistent vs transient antibodies measured early after induction predict long-term clinical remission inpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2018;50:452–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, et al. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly OB, Donnell SO, Stempak JM, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring to guide infliximab dose adjustment is associated with better endoscopic outcomes than clinical decision making alone in active inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Billiet T, Cleynen I, Ballet V, et al. Prognostic factors for long-term infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease patients: a 20-year single centre experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:673–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roblin X, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, et al. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Restellini S, Chao CY, Lakatos PL, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring guides the management of Crohn’s patients with secondary loss of response to adalimumab. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:1531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamperidis N, Middleton P, Tyrrell T, et al. Impact of therapeutic drug level monitoring on outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease treated with Infliximab: real world data from a retrospective single centre cohort study Frontline Gastroenterol Published Online First: 01 February 2019. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, et al. Individualised therapy is more cost-effective than dose intensification in patients with Crohn’s disease who lose response to anti-TNF treatment: a randomised, controlled trial. Gut 2014;63:919–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steenholdt C, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, et al. Individualized therapy is a long-term cost-effective method compared to dose intensification in Crohn’s disease patients failing infliximab. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:2762–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Velayos FS, Kahn JG, Sandborn WJ, et al. A test-based strategy is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation for patients with Crohn’s disease who lose responsiveness to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:654–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guidi L, Pugliese D, Panici Tonucci T, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring is more cost-effective than a clinically-based approach in the management of loss of response to infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: an observational multi-centre study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018. May 31. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy076. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68**.Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first RCT investigating the role of proactive TDM of infliximab in IBD. This study showed that targeting patient’ infliximab trough concentrations to 3–7 μg/mL results in a more efficient use of the drug. Moreover, after dose optimization, continued concentration-based dosing was associated with fewer flares during the course of treatment compared to clinically based dosing.

- 69.Papamichael K, Vajravelu RK, Vaughn BP, Osterman MT, Cheifetz AS. Proactive infliximab monitoring following reactive testing is associated with better clinical outcomes than reactive testing alone in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:804–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70*.Papamichael K, Juncadella A, Wong D, et al. Proactive therapeutic drug monitoring of adalimumab is associated with better long-term outcomes compared to standard of care in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019. January 21. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz018. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This the first study to investigate the role of proactive TDM of adalimumab in IBD. This multicenter, retrospective cohort study reflecting real-life clinical practice provides the first evidence that proactive TDM of adalimumab may be associated with a lower risk of treatment failure compared to standard of care in patients with IBD.

- 71.Papamichael K, Chachu KA, Vajravelu RK, et al. Improved long-term outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving proactive compared with reactive monitoring of serum concentrations of infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1580–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;153:827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitrev N, Vande Casteele N, Seow CH, et al. Review article: consensus statements on therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:1037–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Papamichael K, Osterman MT, Siegel CA, et al. Using proactive therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: from an old concept to a future standard of care? Gastroenterology 2018;154:1201–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Papamichael K, Cheifetz AS. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in IBD: The New Standard-of-Care for Anti-TNF Therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:673–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grossberg LB, Papamichael K, Feuerstein JD, et al. A survey study of gastroenterologists’ attitudes and barriers toward therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tnf therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;24:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Samaan MA, Arkir Z, Ahmad T, et al. Wide variation in the use and understanding of therapeutic drug monitoring for anti-TNF agents in inflammatory bowel disease: an inexact science? Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:452–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Attar A, Duru G, Roblin X, et al. Cost savings using a test-based de-escalation strategy for patients with Crohn’s disease in remission on optimized infliximab: A discrete event model study. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lucidarme C, Petitcollin A, Brochard C, et al. Predictors of relapse following infliximab de-escalation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the value of a strategy based on therapeutic drug monitoring. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greener T, Kabakchiev B, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS. Higher infliximab levels are not associated with an increase in adverse events in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:1808–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bejan-Angoulvant T, Ternant D, Daoued F, et al. Brief Report: relationship between serum infliximab concentrations and risk of infections in patients treated for spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:108–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lega S, Phan BL, Rosenthal CJ, et al. Proactively optimized infliximab monotherapy is as effective as combination therapy in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83**.Colombel JF, Adedokun OJ, Gasink C, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine improves infliximab pharmacokinetic features and efficacy: a post hoc analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. September 26 pii: S1542–3565(18)31024–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.033. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a post hoc analysis of the SONIC RCT showing that among patients with CD and similar serum concentrations of infliximab, combination therapy with azathioprine was not significantly more effective than infliximab monotherapy. Consequently, combination therapy with azathioprine appears to improve efficacy by increasing pharmacokinetic features of infliximab.

- 84.D’Haens G, Vermeire S, Lambrecht G, et al. Increasing infliximab dose based on symptoms, biomarkers, and serum drug concentrations does not increase clinical, endoscopic, and corticosteroid-free remission in patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baert F, Drobne D, Gils A, et al. Early trough levels and antibodies to infliximab predict safety and success of reinitiation of infliximab therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1474–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]