Abstract

Brain renin angiotensin system within the paraventricular nucleus plays a critical role in balancing excitatory and inhibitory inputs to modulate sympathetic output and blood pressure regulation. We previously identified ACE2 and ADAM17 as a compensatory enzyme and a sheddase, respectively, involved in brain renin angiotensin system regulation. Here, we investigated the opposing contribution of ACE2 and ADAM17 to hypothalamic pre-sympathetic activity and ultimately neurogenic hypertension. New mouse models were generated where ACE2 and ADAM17 were selectively knocked down from all neurons (AC-N) or Sim1 neurons (SAT), respectively. Neuronal ACE2 deletion revealed a reduction of inhibitory inputs to AC-N pre-sympathetic neurons relevant to blood pressure regulation. Primary neuron cultures confirmed ACE2 expression on GABAergic neurons synapsing onto excitatory neurons within the hypothalamus but not on glutamatergic neurons. ADAM17 expression was shown to co-localize with Angiotensin-II type 1 receptors on Sim1 neurons and the pressor relevance of this neuronal population was demonstrated by photo-activation. Selective knockdown of ADAM17 was associated with a reduction of FosB gene expression, increased vagal tone and prevented the acute pressor response to centrally-administered Angiotensin-II. Chronically, SAT mice exhibited a blunted blood pressure elevation and preserved ACE2 activity during development of salt-sensitive hypertension. Bicuculline injection in those models confirmed the supporting role of ACE2 on GABAergic tone to the paraventricular nucleus. Together, our study demonstrates the contrasting impact of ACE2 and ADAM17 on neuronal excitability of pre-sympathetic neurons within the paraventricular nucleus and the consequences of this mutual regulation in the context of neurogenic hypertension.

Keywords: ACE2, ADAM17, renin-angiotensin system, optogenetics, autonomic nervous system, hypertension

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, if not controlled can become life threatening as it leads to stroke, kidney diseases and heart failure.1 Among the various drugs used to treat hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, blockers of the renin angiotensin system (RAS), inhibit the detrimental effects of Ang-II and its type 1 receptor, (AT1R). Beyond their expression in peripheral organs, AT1R are also located in the brain where Ang-II signaling increases the activity of excitatory neurons, notably within the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, leading to increased sympathetic output.2 Increased Ang-II activity in the brainstem also decreases baroreflex sensitivity and vagal tone, impairing blood pressure (BP) regulation and leading to neurogenic hypertension. Up-regulation of the brain RAS is a hallmark of neurogenic hypertension.

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cleaves the octapeptide Ang-II to Ang-(1–7), a vasodilator peptide. This cleavage results in nitric oxide release, reduced sympathetic output while restoring baroreflex sensitivity.3 ACE2 overexpression can reduce neurogenic hypertension by lowering Ang-II levels in the brain and reducing sympathetic outflow.4 However, brain ACE2 compensatory activity is reduced in hypertension due to neuronal up-regulation of ADAM17.5 ADAM17 is a member of the disintegrin and metalloprotease family, cleaving membrane proteins and releasing them in the surrounding milieu through a process called shedding.6 ADAM17-induced ACE2 shedding, downstream of AT1R activation, reduces the enzyme’s compensatory activity in experimental models and patients, leading to increased Ang-II levels locally potentially exacerbating neurogenic hypertension.5

ACE2 is expressed on neurons within various brain nuclei,7 including the PVN that contains magnocellular neurons involved in vasopressin and oxytocin secretion and parvocellular neurons involved in pre-sympathetic activity. Heightened firing activity of pre-sympathetic PVN neurons contributes to hypertension.8 However, there has been no study to assess the impact of ACE2 and ADAM17 on neuronal activity and specifically pre-sympathetic activity in the PVN. To selectively target pre-autonomic PVN neurons, we relied on Sim1 (Single-minded 1) expression. Sim1 is a transcription factor involved in the neurodevelopment of the PVN.9 Sim1-expressing neurons are pre-autonomic, possibly expressing AT1R in the PVN.10, 11 Therefore, targeting this neuronal population is a convenient approach to modulate gene expression selectively in BP-related PVN neurons.

In the current study, we investigated the interaction of ADAM17 and ACE2 on PVN pre-sympathetic neurons and hypothesized that ADAM17 would impair ACE2 regulation of neuronal activity on these cells, leading to an increase in sympathetic outflow and eventually BP. To test this hypothesis, we generated new mouse models with selective deletion of ACE2 in neurons or ADAM17 in Sim1-expressing neurons and observed that ACE2 supports an inhibitory input to the PVN while ADAM17 appears crucial in mediating Ang-II-related changes in neuronal excitability.

Materials and Methods

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files]

A detailed Methods section is available in the Online Supplement Methods.

Experiments were performed in adult (14–16 weeks old, 25–30 g) male global ACE2 knockout (KO) (AC-G), neuronal ACE2 knockdown mice (AC-N), Sim1-targeted ADAM17 knockdown mice (SAT) and their control littermates (CL), including mice expressing td-tomato fluorescence on Sim1 neurons (S-T). All mice are on a C57Bl6/J background.

Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility under a 12-hour dark/light cycle, fed standard mouse chow (Envigo, iOS Teklab Extruded Rodent Diet 2019S, Huntingdon, UK) and water ad libitum. Care included a pre-operative injection of Buprenorphine-SR (0.5–1 mg/Kg sc.) for pain relief and Penicillin G Procaine (600–1000 UI/10 g i.m; Blue Springs, MO, USA) as antibiotic. All procedures conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (#3418) and Tulane University (#387) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons between means, Kruskal-Wallis test, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons between means, using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Synaptic activity of kidney-related PVN neurons in control and ACE2 KO mice.

To assess the role of ACE2 in the regulation of neuronal activity of pre-sympathetic neurons in the PVN, we generated a novel mouse model lacking ACE2 selectively on neurons (AC-N). AC-N mice were created by mating mice carrying a floxed ACE2 gene with a mouse that express cre-recombinase on neurons (Fig. 1A). AC-N mice have significantly lower ACE2 activity in the cortex compared to controls (CL: 65.80 ±13.63, n=4; AC-N: 20.15 ±2.74 FU/min/ug protein, n=4, p<0.05, Student’s t-test), confirming the successful knock down.

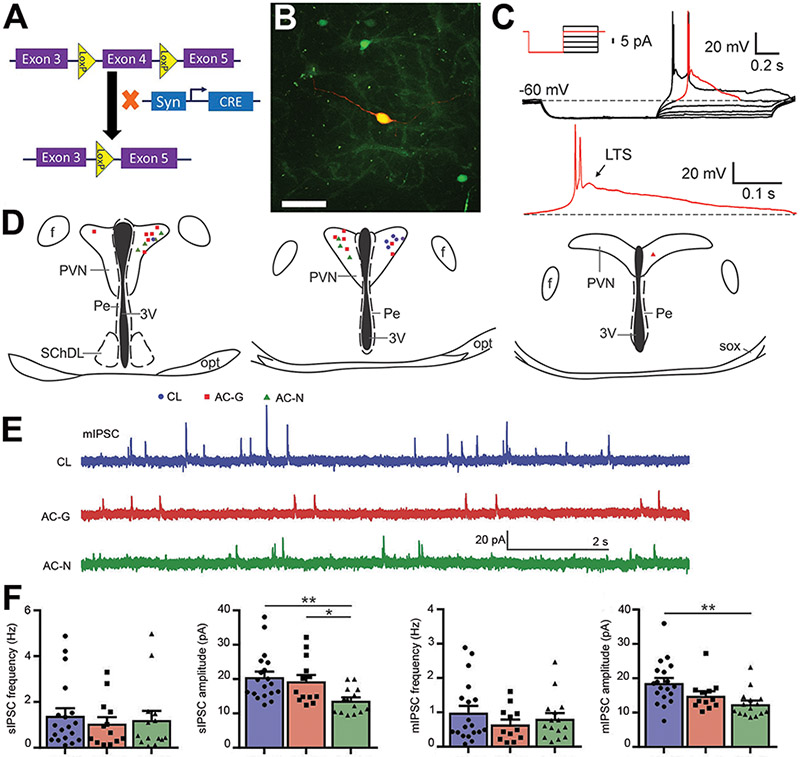

Figure 1. Synaptic activity of kidney-related PVN neurons in control and ACE2 knockout mice.

(A) Design of the neuronal ACE2 knockout mouse (AC-N) using CreLoxP system. ACE2 floxed mice, with LoxP sites flanking exon 4, were crossed with mice expressing cre recombinase driven by the synapsin1 promoter (specific to neurons). As a result, exon 4 of ACE2 was deleted from neurons in the progeny. (B) PVN pre-sympathetic neurons (green) following kidney PRV-eGFP injection. Post-recording staining with biocytin-avidin-Texas Red, in a GFP tagged kidney related neuron. Scale bar= 25 μm. (C) Example of a current-clamp recording from a kidney-related PVN neuron in CL mouse. Depolarizing current steps were applied following hyperpolarization to approximately −80 mV (insert illustrates the step protocol). Low-threshold spike (LTS) was observed in response to depolarizing steps. The red segment of the trace shown in the top panel is presented in the lower panel. Arrow points to LTS. (D) Recorded kidney-related neurons located in the PVN of CL (circle), AC-G (square) and AC-N (triangle) mice (E) Representative recordings of mIPSC at a holding potential of −10mV from a kidney-related PVN neuron in control (CL, top), AC-G (middle) and AC-N (bottom) mice. (F) Combined data showing the comparisons of frequency and amplitude for miniature and spontaneous IPSC (ANOVA *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=13-19/group).

To identify PVN pre-sympathetic neurons projecting to peripheral organs involved in BP regulation, a retrograde trans-neuronal pseudorabies virus (PRV-152) was injected into the kidney, innervated solely by a sympathetic nerve, and labeling was identified in the hypothalamus.12 Within the PVN, PRV-152-transfected neurons were identified by the virus eGFP tag (Fig. 1B) and used for patch-clamp recordings. Biocytin in eGFP neurons confirmed that the recorded neurons were kidney-related (Fig. 1B). Current-clamp recording of kidney-related eGFP-labeled neurons revealed the presence of low threshold spikes (LTS) 13 in response to depolarizing current pulses following hyperpolarization of the membrane (Fig. 1C), further indicating that the recorded neurons are pre-sympathetic parvocellular neurons.

The impact of ACE2 on synaptic activity of pre-sympathetic neurons was assessed in mice lacking ACE2, either globally (AC-G) or specifically from neurons (AC-N) and CL. There was no significant change in baseline MAP among groups (CL: 101.2 ±1.3, n=14; AC-G: 100.6 ±2.5, n=9; AC-N: 106.5 ±3.1 mmHg, n=8). Pre-sympathetic neurons were recorded throughout the PVN (Fig. 1D). Spontaneous (sEPSC) and miniature (mEPSC) excitatory postsynaptic currents of kidney-related PVN neurons were not significantly affected by the lack of ACE2 (Fig. S1, A-E).

As for the inhibitory neurotransmission of kidney-related pre-sympathetic PVN neurons (Fig. 1E), the average sIPSC frequency did not show a significant difference between groups (CL: 1.4 ±0.3 Hz, n=19; AC-G: 1.1 ±0.3 Hz, n=13; AC-N: 1.2 ±0.4 Hz, n=14; Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn, p=0.7824, Fig. 1F). In contrast, in AC-N mice the amplitude of sIPSC was significantly smaller compared with AC-G and CL mice (CL: 20.6 ±1.6 pA, n=19; AC-G: 19.4 ±1.8 pA, n=13; AC-N: 13.7 ±1.0 pA, n=14; ANOVA, F=5.567, p=0.0071 Fig. 1F). The frequency of mIPSC was unchanged among the groups (CL: 1.0 ± 0.2 Hz, n=19; AC-G: 0.6 ±0.1 Hz, n=12; AC-N: 0.8 ±0.2 Hz, n=15; Kruskal-Wallis, Dunn, p=0.557, Fig. 1F). However, the amplitude of mIPSC was significantly lower in AC-N mice compared to CL (CL: 18.6 ±1.5 pA, n=19; AC-G: 14.9 ±1.3 pA, n=12; AC-N: 12.5 ±1.0 pA, n=15; ANOVA, F=6.048, p=0.0048, Fig. 1F).

Together, these data indicate that the lack of ACE2 does not alter the excitatory neurotransmission to kidney-related PVN pre-sympathetic neurons. However, the decreased amplitude of IPSC suggests either a reduced expression of postsynaptic GABAA receptors or changes in the function of postsynaptic GABA receptors.

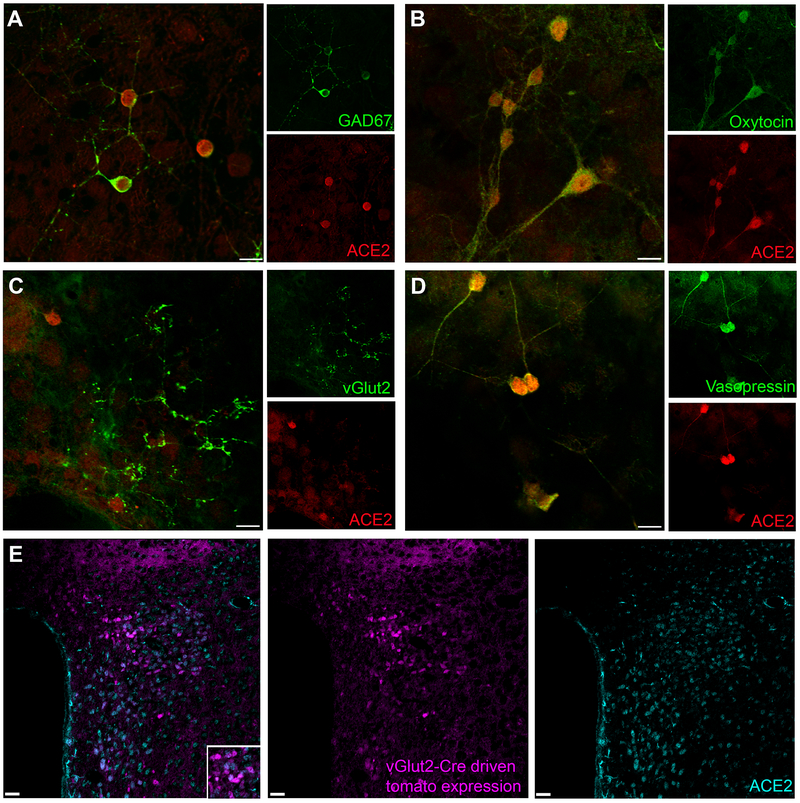

Prevalence of ACE2 on hypothalamic neuronal sub-populations

Sympathetic outflow from the PVN is basally restrained by a GABAergic inhibitory tone.14 To determine whether ACE2 is expressed on inhibitory neurons, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on hypothalamic primary neuronal cultures. ACE2 expression was detected on GABAergic neurons expressing Gad67 (Fig. 2A). ACE2 also co-localized with oxytocin (Fig. 2B) and vasopressin (Fig. 2D). Importantly, ACE2 did not appear to co-localize with glutamatergic (vGluT2) neurons (Fig. 2C). Excitatory glutamatergic neurons, labeled with an antibody targeting the vesicular glutamate transporter, presented a characteristic punctate pattern that appears on axon terminals.15 Although glutamatergic neurons do not express ACE2, they seem to synapse with ACE2-expressing neurons (Fig. 2C). To verify the lack of co-localization between ACE2 and glutamatergic neurons in the PVN, we used a reporter mouse expressing td-Tomato fluorescence under the control of the vGluT2 promoter.16 While IHC in the PVN of these mice revealed abundant ACE2-positive neurons and glutamatergic neurons, these populations showed very few overlap (Fig. 2E), leading us to conclude that ACE2 is not generally expressed on glutamatergic excitatory neurons in the PVN.

Figure 2. Prevalence of ACE2 within hypothalamic neuronal subpopulations.

(A-D) Immunohistochemistry of primary neuron cultures obtained from the hypothalamus of C57Bl6/J neonates. (A) Gad67-labeled (green) GABAergic neurons and ACE2-labeled (red) neurons overlap completely. (B) Oxytocinergic neurons (green) and ACE2-labeled neurons (red) overlap completely. (C) vGluT2-labeled glutamatergic neurons (green) and ACE2-labeled neurons (red) do not overlap but the excitatory neurons seem to synapse onto ACE2-expressing neurons. (D) Vasopressinergic neurons (green) co-localize with ACE2-expressing (red). (E) vGlut2-reporter mice express red fluorescence on excitatory neurons in the PVN. ACE2 expression (cyan) does not overlap with the glutamatergic neurons (purple) Scale Bar= 10 μm (primary neurons) and 25 μm (tissue)

ADAM17 is abundantly expressed on PVN neurons.

ADAM17-driven ACE2 shedding is a mechanism that lowers ACE2 activity and impedes the compensatory RAS. To further characterize the relationship between ACE2 and ADAM17, we assessed its expression in the PVN. To study PVN pre-autonomic neurons, we generated a transgenic mouse (S-T) where td-Tomato fluorescence is expressed on Sim-1 neurons (Fig. 3A), with the characteristic “butterfly pattern” of neurons flanking the third ventricle (Fig. 3B inset). Immuno-labeling the PVN of S-T mice with ADAM17, revealed an extremely high co-localization with td-Tomato-expressing Sim1 neurons (Fig. 3B). Further verification of the expression of ADAM17 on excitatory (i.e. glutamatergic) neurons in the PVN, was performed by in situ hybridization. ADAM17 and vGluT2 mRNA strongly co-localized in the PVN (Fig. 3C), confirming the expression of the sheddase on excitatory neurons. Finally, while GABA-expressing neurons are generally thought to be projecting to the PVN but not reside in that region, Gad67 mRNA was shown to co-localize with ADAM17 mRNA in some PVN neurons (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. ADAM17 expression within the Sim1-neurons.

(A) Design of the Sim1-tomato reporter mice (S-T) using CreLoxP system. (B) Inset: Sim1-promoter-driven cre-recombinase expression leads to tdTomato expression in all Sim1-neurons (red) around the third ventricle, scale bar= 30 μm. ADAM17 immunofluorescence (green) co-localizes (yellow) with Sim1 neurons (red), scale bar= 50 μm. Fluorescent in situ hybridization on PVN tissue from control mice, probing for: (C) vGluT2 mRNA (red) in tissue sections with ADAM17 mRNA (green), scale bar= 10 μm and (D) Gad67 mRNA (green) in tissue sections with ADAM17 mRNA (blue) reveals that ADAM17 is co-expressed on both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Scale bar= 10 μm (E) Sim1-positive tomato neurons co-localize (yellow) with kidney projecting pre-sympathetic neurons labeled with PRV-eGFP (green), scale bar= 30 μm. (F) Digital droplet PCR data from sorted Sim-1 tomato neurons showing AT1 receptor and ADAM17 co-expression. ADAM17 expression is higher than AT1A receptor expression in these cells (PC: positive control [kidney], NC: negative control [water], Student’s unpaired t test, ***p<0.001, n=3).

Relevance of Sim1-PVN neurons to BP regulation

Sim1 haplo-insufficiency leads to reduction of both magnocellular and parvocellular neurons of the PVN,17 suggesting that Sim1-driven td-Tomato expression covers a large (Fig. 3B) and heterogeneous population of neurons. To verify that this Sim1 population in the PVN includes pre-autonomic neurons, we used retrograde labeling from the kidney. After 96–110 h, kidney-related (eGFP-labelled)-neurons in the PVN (Fig. 3E) were shown to co-localize with Sim1 (td-Tomato) neurons (Fig. 3E), indicating their pre-autonomic nature. To further characterize the Sim1 neuronal population, td-Tomato-labeled cells were sorted from the hypothalamus and processed for gene expression by digital droplet PCR analysis. AT1aR and ADAM17 mRNA were both found to be present in Sim1-positive neurons (Fig. 3F), with ADAM17 mRNA copies being 3-fold higher than AT1aR mRNA (Fig. 3F).

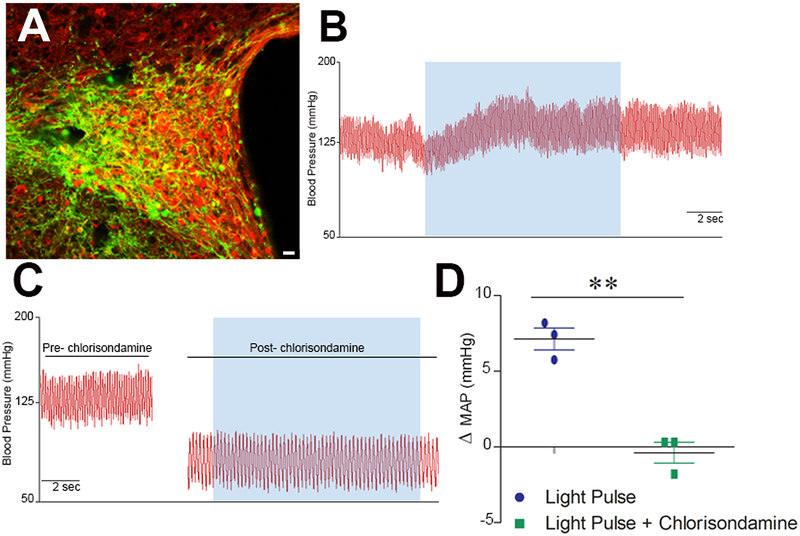

Finally, to determine the physiological relevance of these PVN Sim1 neurons for BP regulation, we selectively stimulated these cells using optogenetics. An AAV-EF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP was stereotaxically injected bilaterally in the PVN of Sim1-cre mice (Fig. 4A), allowing for activation of channelrhodopsin selectively in Sim1 neurons harboring cre-recombinase. Photo-activation led to a rapid increase in BP (Fig. 4B,D). To determine whether this BP response resulted from an activation of the autonomic nervous system or neuro-hormonal release, the photo-activation was repeated in presence of a ganglionic blocker. Chlorisondamine lead to a significant drop of BP and heart rate (ΔHR: −279.9 ±3.6, n=3) confirming blockade of the autonomic nervous system (Fig. 4C,D). Under these conditions photo-activation of Sim1 neurons failed to produce a significant BP rise suggesting that the Sim1 population in the PVN is majorly pre-sympathetic. As a result, using Sim1-driven cre-recombinase expression to manipulate gene expression becomes an important tool to tease out the function of ADAM17 on these neurons.

Figure 4. Cardiovascular effect of stimulating Sim1-PVN neurons.

(A) AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP expression in PVN Sim1-neurons following virus injection. Scale bar= 20 μm. (B) BP recording from a mouse previously injected with AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP. Unilateral photo-excitation (20 Hz) of PVN neurons (blue shade) led to a rapid BP elevation. (C) Photo-activation in presence of a ganglionic blocker, Chlorisondamine, inhibited the BP response. (D) Summary data comparing the effect of light activation in presence and absence of chlorisondamine (Student’s unpaired t test, **p<0.01, n=3).

Selective deletion of ADAM17 on Sim1-PVN neurons

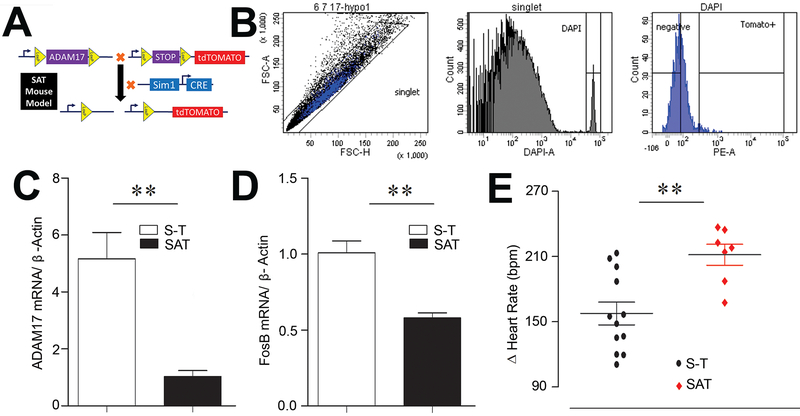

Considering that the Sim1-PVN population contains neurons capable of driving BP changes (Fig. 4B, D) and that ADAM17 is expressed on these neurons (Fig. 3B-D), our next goal was to understand the role of ADAM17 on neuronal excitability. Accordingly, we used the Cre-LoxP system to generate triple transgenic mice (SAT), expressing the td-Tomato reporter in ADAM17 knockdown Sim1 neurons (Fig. 5A). Using td-Tomato expression to sort Sim1-neurons (Fig. 5B), the successful knockdown of ADAM17 was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR in SAT mice compared to S-T controls (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, expression of FosB, a marker of chronic neuronal activation, was significantly reduced (P<0.01) in SAT mice (Fig. 5D). To determine if vagal tone could benefit from a knockdown of ADAM17 on pre-sympathetic Sim1 neurons, mice were treated with a muscarinic blocker. As a result, the tachycardic response to atropine was significantly increased (P<0.01) in SAT mice compared to S-T controls (Fig. 5E) indicating a greater cardiac parasympathetic tone. Together these data suggest that Sim1-driven ADAM17 knockdown reduces the neuronal activation of pre-sympathetic PVN neurons and improved the autonomic balance by favoring vagal regulation of the heart.

Figure 5. Selective deletion of ADAM17 from Sim1-PVN neurons.

(A) Design of the triple transgenic mouse (SAT) exhibiting a Sim1-Cre-driven ADAM17 deletion and tdTomato reporter expression. (B) Representative sorting strategy for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) in hypothalamic cells. The histogram (DAPI+ cells) was created based on the forward scatter heights (FSC-H) and side scatter heights (SSC-H) of the sorted cells (DAPI+ events). Respective gates for neurons (tdTomato+ cells) and non-neuron/non-astrocyte cells were created based on the PE heights (PE-A). qRT-PCR measurement of ADAM17 (C) and FosB (D) was performed in sorted hypothalamic cell populations from control and SAT mice (n=4/group). (E) Atropine i.p. led to an exaggerated tachycardia in SAT mice (Student’s unpaired t test, **p<0.01, n=7-12/group).

ADAM17 is a critical mediator of RAS activation in PVN pre-sympathetic neurons

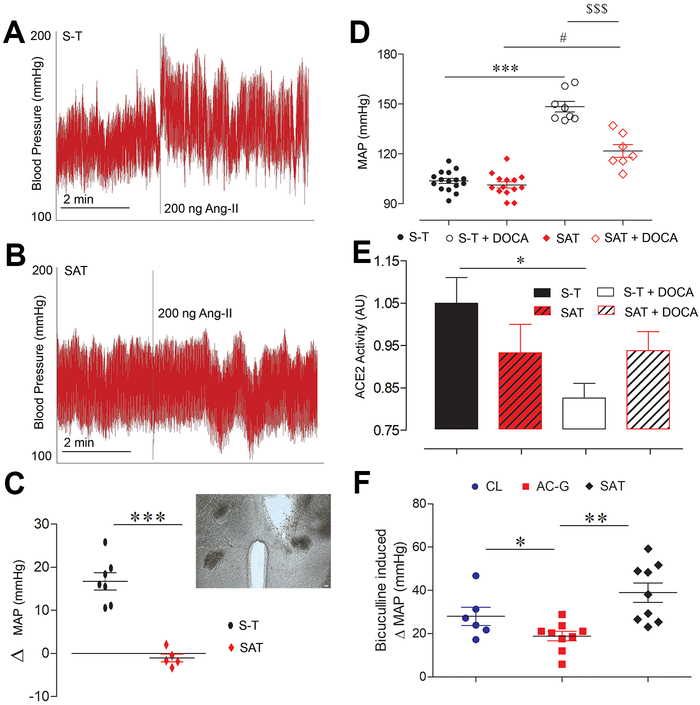

Ang-II stimulates neurotransmission in the PVN via AT1R, leading to increases in arterial BP and renal sympathetic nerve activity.18, 19 Stereotaxic injection of Ang-II into the PVN (Fig. 6C, inset) of freely moving S-T mice led to a typical ~15 mmHg increase in mean BP (Fig. 6A,C).18 Interestingly, the same dose of Ang-II failed to elevate BP in mice with an ADAM17-knockdown in Sim1 PVN neurons (Fig. 6B,C).

Figure 6. ADAM17 mediates RAS-induced BP rise.

Representative BP traces in S-T (A) and SAT mice (B) following unilateral PVN injection of Ang-II (200 ng/ 400 nl). (C) Summary data of Ang-II injection in the PVN of control (S-T, circle) and SAT mice (diamond), (inset, scale bar= 30 μm) location of the cannula placement for Ang-II injections in the PVN. (D) Summary data for mean arterial pressure (MAP) at baseline in S-T (closed circle) and SAT (closed diamond) mice and following 18 days of DOCA-salt treatment, showing a strong BP increase in S-T (open circle) and a blunted effect in SAT mice (open diamond) (1-way Kruskal-Wallis test, #p<0.05 vs. SAT, ***p<0.001 vs. S-T, $ $ $p<0.001 vs. S-T+DOCA, n=4-7/group). (E) DOCA-salt treatment reduced ACE2 activity in the control. It was preserved in SAT mice on DOCA-salt (1-way Kruskal-Wallis test, *p<0.05, n=8-12/group). (F) GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline, in the PVN induced change in MAP of CL (circle), AC-G (square) and SAT (Diamond) mice (1-way ANOVA, Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, **p<0.01, n=6-9/group)

To determine the impact of ADAM17 deletion from Sim1 PVN neurons in hypertension, mice underwent a DOCA-salt protocol known to induce RAS activation within the brain and associated with enhanced sympathetic activity.20 Baseline BP was not different between S-T and SAT mice, suggesting that ADAM17 does not contribute to BP regulation in normal conditions. Deletion of ADAM17 selectively from Sim1 neurons was associated with a significant reduction of salt-sensitive hypertension (p<0.001) in SAT mice compared to S-T controls (Fig. 6D). While ACE2 activity is usually reduced in DOCA-salt treated mice,4, 5 the compensatory activity was preserved in mice lacking ADAM17 selectively from Sim1 neurons (Fig. 6E). Together, our data show that ADAM17 expression in PVN pre-sympathetic neurons significantly contributes to the AT1R-mediated pressor response in salt-sensitive hypertension while limiting ACE2 compensatory activity.

Functional significance of GABAA signaling on blood pressure

The impact of reduced ACE2 or ADAM17 levels on GABAergic signaling was verified in the whole animal by measuring the BP response to a unilateral PVN injection of a GABAA receptor antagonist. The bicuculline-evoked pressor effect is well documented14 and PVN injection resulted in an expected 28 ±4 mmHg increase in BP for CL mice. This pressor response was significantly reduced in AC-G mice (19 ±2 mmHg; p<0.05, Fig. 6F) although the mIPSC amplitude only trended to a decrease in this group (Fig. 1F). Selective deletion of ADAM17 on Sim1 neurons resulted in an opposite trend (39 ±4 mmHg; p=0.06, Fig. 6F). Importantly, SAT and AC-G mice exhibited opposite and significantly different pressor responses (p<0.01) confirming the reverse impact of ACE2 and ADAM17 on GABAergic inhibitory input to the PVN.

Discussion

ACE2 is expressed on neurons, including within the brain nuclei involved in cardiovascular regulation.7 Overexpressing ACE2 in the brain leads to a blunted development of DOCA-salt hypertension21, 22 while global ACE2 KO mice have a lower vagal tone and a heightened sympathetic hold on the heart.23 In this study, we uncovered a new mechanism that facilitates ACE2-mediated compensatory activity within the PVN. In addition, we show that PVN expression of ADAM17 limits the compensatory role of ACE2 by promoting enhanced neuronal activity, mediating local Ang-II pressor effects and reducing ACE2 enzyme activity in a chronic hypertensive state.

The PVN is a central nucleus that regulates neuro-hormonal output and sympathetic tone to the periphery.24 In this study, patch-clamping PVN neurons revealed that neuronal ACE2 supports the inhibitory input to the PVN. Retrograde tracing from the kidney allowed us to identify PVN pre-sympathetic neurons relevant to BP regulation. The pre-sympathetic and non-neurosecretory nature of these PVN neurons was confirmed by a characteristic low threshold spike.13 From these neurons, we observed that lack of ACE2 leads to a greater decrease in the amplitude of spontaneous and miniature IPSC, allowing us to speculate that ACE2 amplifies post-synaptic transmission of inhibitory currents.

The PVN receives inhibitory and excitatory neuronal inputs from surrounding circumventricular organs.25 Balancing these opposing inputs within the PVN is crucial to prevent sympathetic overdrive. The quest to find the source of the inhibitory inputs to the PVN has revealed a role for circumventricular organs. Grob et al. reported that acute water and sodium depletion, diminishes the GABAergic system in the lamina terminalis by reporting a reduction in Gad65 expressing neurons.26 Recent reports using single cell RNA sequencing to create a molecularly annotated and spatially resolved map of the mouse hypothalamic preoptic region located a large number of inhibitory projections from the median preoptic area (MnPO) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) to the PVN.27

In the mouse basolateral amygdala, overexpression of ACE2 significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous IPSC (indicative of presynaptic release of GABA) from pyramidal neurons.28 This effect was eliminated by central administration of a MasR antagonist, suggesting that ACE2 plays a critical role in GABA neurotransmission by catalyzing the formation of Ang-(1–7).28 Through activation of a nitric oxide (NO)-mediated pathway, Ang-(1–7) can significantly increase extracellular GABA release,29 supporting its sympatho-inhibitory role. Our study extends these findings by showing for the first time that ACE2 plays a crucial role in maintaining the amplitude of IPSC to the PVN and the overall GABAergic input to the PVN. To demonstrate directly whether the reduction of IPSC amplitude (Fig. 1F) was of functional significance, we injected a GABA antagonist into the PVN of control and ACE2 KO mice and reported a blunted pressor response in KO mice (Fig. 6F) supporting the role of ACE2 in inhibitory tone to the PVN. We also revealed that ACE2 is prevalent on GABAergic neurons and while there is no co-localization of ACE2 with glutamatergic neurons in the PVN, we report that glutamatergic excitatory neurons synapse with ACE2-expressing neurons. The PVN mainly contains glutamatergic neurons, however, it is the inhibitory inputs that limit PVN-excitability and therefore overall sympathetic output.30 Here we show that ACE2 imposes a strong role in maintaining the inhibitory input to the PVN. These observations are in line with our recent data31 showing ADAM17 expression on glutamatergic neurons and previous report describing TNFα-mediated reduction of inhibitory synaptic strength and down-regulation of GABAA receptors.32

Within the neurosecretory population, ACE2 co-localizes with vasopressinergic and oxytocinergic neurons. Reportedly, stimulating oxytocinergic neurons projecting from the PVN to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus can rescue chronic intermittent hypoxia/ hypercapnia-related hypertension indicating their beneficial role for BP control.33

While our data suggest that ACE2 is expressed on vasopressinergic neurons (Fig. 2D), PVN neurons expressing vasopressin are mostly glutamatergic,30 which would contrast with our observation that ACE2 hardly co-localize with vGluT2 in the PVN. Another explanation could be that these cells are not PVN neurons. Because, this identification was performed in cultured primary neurons the precise origin is uncertain and could be from another hypothalamic region (e.g. SON).

It is possible that ACE2 expression on vasopressinergic neurons modulates plasma vasopressin concentrations. Interestingly, water deprivation and salt loading in a rat model did not change ACE2 mRNA levels in the PVN, even though vasopressin mRNA expression was significantly higher.34 Accordingly, ACE2 expression in vasopressinergic and oxytocinergic neurons reveals a potential new layer of neuro-hormonal regulation of homeostasis that needs further exploration.

Together, our data suggests that ACE2 is predominantly expressed on inhibitory neurons and contributes to maintaining an inhibitory tone to the PVN. During RAS overactivity, there is an enhanced AT1R activation in the brain that leads to translocation of mature ADAM17 onto the cell membrane.5 ACE2 is a target of ADAM17-mediated shedding, which significantly downregulates ACE2 activity and contributes to autonomic dysregulation and neurogenic hypertension.4, 5 Accordingly, we next evaluated the role of ADAM17 in PVN neuronal excitability.

To assess the impact of ADAM17 on PVN excitability, we took advantage of the Sim1 transcription factor that enables PVN neuro-development and therefore highly expressed in this nucleus.17 Although previous studies used Sim1-driven cre-recombinase to delete/overexpress genes of interest in the PVN,35-38 our study makes two important findings. First, Sim1-expressing neurons in the PVN contain kidney-related (i.e. neurons projecting to a sympathetic ganglion innervating the kidney) pre-sympathetic neurons, thus thought to be relevant to BP regulation. Although co-labeling was restricted to a subpopulation of Sim1 neurons, other groups have shown projections to the spinal cord39 and sympathetic innervation of the bone.40 Therefore, it is likely that Sim1 PVN neurons are connected to sympathetic branches innervating various end organs, some of which may have a critical role in BP regulation. The second observation is that photo-stimulation of PVN Sim1 neurons leads to a rapid increase in BP, confirming a role in BP control. However, the magnocellular population also contains neurons that can potentially release vasopressin in the systemic circulation and increase BP via V1A receptors on vessels, suggesting that the BP increase observed following photo-stimulation might not necessarily implies a sympathetic involvement. This option can be ruled out firstly because the time scale, in which the light-driven BP response occurs, is in the milliseconds range and can hardly justify a hormonal effect. In addition, ganglionic blockade completely abolished the light-induced BP increase supporting a sympathetic contribution. While Sim1 PVN neurons are known to project to the nucleus of the tractus solitarius, cardio-vagal nuclei in the brainstem and spinal cord sympathetic preganglionic neurons,10, 11, 17 this is the first evidence of a direct role for a subpopulation of Sim1 PVN neurons in BP regulation.

Not surprisingly, ADAM17 expression was robust in Sim1 neurons and overlapped both magnocellular and parvocellular populations. Cell-sorting followed by digital droplet PCR confirmed co-localization with AT1A receptors with a 3:1 ratio for ADAM17:AT1A receptor mRNA copies. AT1A receptors have previously been suggested to be expressed on Sim1 neurons where they would support the BP rise associated with obesity.10 Deletion of ADAM17 from Sim1 neurons was associated with a reduction of neuronal activity marker and an enhanced vagal tone, suggesting that the sheddase might contribute to pre-sympathetic excitability, in line with our recent findings in glutamatergic neurons.31 We recently observed ADAM17 mRNA expression on GABAergic neurons in the MNPO, BNST and PVN. Deleting ADAM17 from excitatory neurons increased Gad67 expression within the hypothalamus of DOCA-salt hypertensive mice, suggesting an increased GABAergic inhibitory input. Considering ACE2 pre-dominant expression on inhibitory neurons and its sensitivity to ADAM17, we speculate that ACE2 expression on GABAergic neurons contributes to the inhibitory input to pre-sympathetic PVN neurons while ADAM17 appears to promote their excitability, partly by activation of AT1 receptors.

However, our study has some limitations. While other authors have shown that ACE2-mediated formation of Ang-(1–7) contributed to GABA release in the basolateral amygdala,28 it remains to be determined whether the same mechanism promotes inhibitory input to PVN pre-sympathetic neurons. Another limitation is that our ADAM17 knockdown in SAT mice occurred beyond the boundaries of the PVN where lesser levels of Sim1 are expressed, notably in the amygdala but also in the kidney.35 While we recognize a possible contribution of the amygdala to the reduction of hypertension in DOCA-salt-treated mice, we did not observe a significant reduction of ADAM17 mRNA in the kidneys of SAT mice (data not shown).

While global ACE2 KO mice’ response to bicuculline was consistent with ACE2 support of an inhibitory tone to the PVN, selective neuronal ACE2 KO mice would have provided a more definite evidence, notably by eliminating the multifaceted outcome, global ACE2 deletion might have on synaptic function.

Another important point is that ADAM17 is also known as TNFα convertase, responsible for the formation of active TNFα. Accordingly, deletion of ADAM17 in SAT mice is likely to have reduced TNFα and other pro-inflammatory cytokine levels thus contributing to the reduction of DOCA-salt hypertension independently of ACE2.

Supplementary Material

Perspective: While it has been shown that ACE2 expression in the brain is cardio-protective and prevents the development of hypertension, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Previous studies revealed a role for the inhibition of oxidative stress, cyclooxygenase 2, microglial activation and increased formation of nitric oxide.22, 23, 41-43 Our study provides a new mechanism by which ACE2 opposes autonomic dysfunction, by sustaining inhibitory inputs to pre-sympathetic PVN neurons, while its sheddase, ADAM17, promotes excitatory neuronal activity. In addition, the availability of the first ACE2 floxed mouse is poised to increase research in the role of ACE2 in multiple tissues and organs.

Novelty and significance.

1. What is new?

ACE2 maintains inhibitory neurotransmission into the PVN and its expression is prevalent on inhibitory neurons.

We generated a new transgenic mouse, with the ACE2 gene flanked by LoxP sites so that it can be selectively deleted in a tissue specific manner. Here we deleted ACE2 specifically from neurons.

ADAM17 is an ACE2 sheddase that is upregulated following activation of AT1 receptors. Here we find that ADAM17 promotes neuronal activation of PVN and is a key factor that mediates brain Ang-II driven increase in BP.

2. What is relevant?

Balancing inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission from the PVN is essential to prevent a sympathetic overdrive. AT1 receptor stimulation in the PVN is known to increase sympathetic nerve activity, as well as upregulate ADAM17 expression.

ADAM17 upregulation in the brain leads to ACE2 shedding which compromises the compensatory axis of RAS, promoting neurogenic hypertension.

3. Summary

ACE2 is the enzyme that opposes the overactivated RAS by cleaving Ang-II to Ang-(1–7) and activating the compensatory axis of this system. ADAM17 is a sheddase that is activated by AT1 receptor stimulation when the classical RAS is overactivated in the brain. ACE2 is a substrate of ADAM17 and is cleaved when RAS is overactivated. This promotes autonomic dysregulation. In fact, lack of ADAM17 prevents the pressor response when Ang-II is injected in the PVN. In a chronic model of DOCA-salt hypertension, lack of ADAM17 preserves ACE2 activity and blunts development of neurogenic hypertension. Moreover, we find that ACE2 accentuates GABAergic inhibitory inputs to the pre-sympathetic neurons in the PVN which keeps the sympathetic output in check.

Acknowledgements

The ACE2flox/flox ES cells used for this project were generated by the trans-NIH Knock-Out Mouse Project (KOMP) and obtained from the KOMP Repository (www.komp.org). The authors would like to thank Kathryn Earnest and Charlotte Pearson for excellent technical support, Dr. Tyler Basting for contributing to the optogenetics design, Dr. Kim Pedersen for contributing to the AC-N development, Dr. Jeffrey Erickson for sharing the vGluT2 antibody, Dr. Jeffrey Tasker for providing the Sim1-cre mice, Dr. Luis Marrero, Director of the Morphology and Imaging Core, and Dr. Randall Mynatt, Director of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Transgenic Core.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL093178 to E.L. and COBRE P30GM106392), the Department of Veterans Affairs (BX004294 to E.L.), the American Heart Association (15POST25000010 to J.X.) and the LSUHSC-NO Research Enhancement Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None, the authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ambrosius WT, Sink KM, Foy CG, Berlowitz DR, Cheung AK, Cushman WC, Fine LJ, Goff DC Jr., Johnson KC, Killeen AA, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Reboussin DM, Rocco MV, Snyder JK, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr., Whelton PK. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: The systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT). Clin Trials. 2014;11:532–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leenen FH. Actions of circulating angiotensin II and aldosterone in the brain contributing to hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:1024–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia H, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: Central regulator for cardiovascular function. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:170–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia H, Sriramula S, Chhabra K, Lazartigues E. Brain ACE2 shedding contributes to the development of neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2013;113:1087–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu J, Sriramula S, Xia H, Moreno-Walton L, Culicchia F, Domenig O, Poglitsch M, Lazartigues E. Clinical relevance and role of neuronal AT1 receptors in ADAM17-mediated ACE2 shedding in neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2017;121:43–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J, Mukerjee S, Silva-Alves C, Carvalho-Galvão A, Cruz J, Balarini C, Braga V, Lazartigues E, França-Silva MdS. A disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 in the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Front Physiol. 2016. October 18;7:469. eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doobay MF, Talman LS, Obr TD, Tian X, Davisson RL, Lazartigues E. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007. January;292(1):R373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li DP, Yang Q, Pan HM, Pan HL. Pre- and postsynaptic plasticity underlying augmented glutamatergic inputs to hypothalamic presympathetic neurons in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Physiol. 2008;586:1637–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michaud JL, Boucher F, Melnyk A, Gauthier F, Goshu E, Levy E, Mitchell GA, Himms-Hagen J, Fan CM. Sim1 haploinsufficiency causes hyperphagia, obesity and reduction of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1465–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Kloet AD, Pati D, Wang L, Hiller H, Sumners C, Frazier CJ, Seeley RJ, Herman JP, Woods SC, Krause EG. Angiotensin type 1a receptors in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus protect against diet-induced obesity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4825–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinol RA, Bateman R, Mendelowitz D. Optogenetic approaches to characterize the long-range synaptic pathways from the hypothalamus to brain stem autonomic nuclei. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;210:238–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano G, Card JP, Sved AF. Dual viral transneuronal tracing of central autonomic circuits involved in the innervation of the two kidneys in rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;471:462–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luther JA, Tasker JG. Voltage-gated currents distinguish parvocellular from magnocellular neurones in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Physiol. 2000;523 Pt 1:193–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen QH, Toney GM. Responses to GABA-A receptor blockade in the hypothalamic PVN are attenuated by local AT1 receptor antagonism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003. November;285(5):R1231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle S, Pyndiah S, De Gois S, Erickson JD. Excitation-transcription coupling via calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase/ERK1/2 signaling mediates the coordinate induction of VGLUT2 and Narp triggered by a prolonged increase in glutamatergic synaptic activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14366–14376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basting T, Xu J, Mukerjee S, Epling J, Fuchs R, Sriramula S, Lazartigues E. Paraventricular nucleus over activation is a critical driver in the development of neurogenic hypertension. J. Physiol. 2018;596:6235–6248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duplan SM, Boucher F, Alexandrov L, Michaud JL. Impact of Sim1 gene dosage on the development of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:2239–2249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazartigues E, Dunlay SM, Loihl AK, Sinnayah P, Lang JA, Espelund JJ, Sigmund CD, Davisson RL. Brain-selective overexpression of angiotensin (AT1) receptors causes enhanced cardiovascular sensitivity in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2002;90:617–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabor A, Leenen FH. Cardiovascular effects of angiotensin II and glutamate in the PVN of dahl salt-sensitive rats. Brain Res. 2012;1447:28–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basting T, Lazartigues E. Doca-salt hypertension: An update. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia H, Queiroz TM, Sriramula S, Feng Y, Johnson T, Mungrue IN, Lazartigues E. Brain ACE2 overexpression reduces DOCA-salt hypertension independently of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R370–R378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sriramula S, Xia H, Xu P, Lazartigues E. Brain-targeted angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression attenuates neurogenic hypertension by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-mediated inflammation. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2015;65:577–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia H, Suda S, Bindom S, Feng Y, Gurley SB, Seth D, Navar LG, Lazartigues E. ACE2-mediated reduction of oxidative stress in the central nervous system is associated with improvement of autonomic function. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dampney RA. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiological reviews. 1994;74:323–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou JJ, Ma HJ, Shao JY, Pan HL, Li DP. Impaired hypothalamic regulation of sympathetic outflow in primary hypertension. Neurosci Bull. 2019. February;35(1):124–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grob M, Trottier JF, Drolet G, Mouginot D. Characterization of the neurochemical content of neuronal populations of the lamina terminalis activated by acute hydromineral challenge. Neuroscience. 2003;122:247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moffitt JR, Bambah-Mukku D, Eichhorn SW, Vaughn E, Shekhar K, Perez JD, Rubinstein ND, Hao J, Regev A, Dulac C, Zhuang X. Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2018;362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, de Kloet AD, Pati D, Hiller H, Smith JA, Pioquinto DJ, Ludin JA, Oh SP, Katovich MJ, Frazier CJ, Raizada MK, Krause EG. Increasing brain angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity decreases anxiety-like behavior in male mice by activating central mas receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2016;105:114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stragier B, Hristova I, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. In vivo characterization of the angiotensin-(1–7)-induced dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid release in the striatum of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:658–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dampney RA, Michelini LC, Li DP, Pan HL. Regulation of sympathetic vasomotor activity by the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in normotensive and hypertensive states. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315:H1200–h1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu J, Molinas AJR, Mukerjee S, Morgan DA, Rahmouni K, Zsombok A, Lazartigues E. Activation of ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17) on glutamatergic neurons selectively promotes sympathoexcitation. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2019;73:1266–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pribiag H, Stellwagen D. TNF-alpha downregulates inhibitory neurotransmission through protein phosphatase 1-dependent trafficking of GABA(A) receptors. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15879–15893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jameson H, Bateman R, Byrne P, Dyavanapalli J, Wang X, Jain V, Mendelowitz D. Oxytocin neuron activation prevents hypertension that occurs with chronic intermittent hypoxia/hypercapnia in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016. June 1;310(11):H1549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dos-Santos RC, Monteiro L, Paes-Leme B, Lustrino D, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Mecawi AS, Reis LC. Central angiotensin-(1–7) increases osmotic thirst. Exp Physiol. 2017. November 1;102(11):1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solomon MB, Loftspring M, de Kloet AD, Ghosal S, Jankord R, Flak JN, Wulsin AC, Krause EG, Zhang R, Rice T, McKlveen J, Myers B, Tasker JG, Herman JP. Neuroendocrine function after hypothalamic depletion of glucocorticoid receptors in male and female mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:2843–2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cakir I, Diaz Martinez M, Lining Pan P, Welch EB, Patel S, Ghamari-Langroudi M. Leptin receptor signaling in Sim1-expressing neurons regulates body temperature and adaptive thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2019. April 1;160(4):863–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singha AK, Yamaguchi J, Gonzalez NS, Ahmed N, Toney GM, Fujikawa T. Glucose-lowering by leptin in the absence of insulin does not fully rely on the central melanocortin system in male mice. Endocrinology. 2019;160:651–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semple E, Shalabi F, Hill JW. Oxytocin neurons enable melanocortin regulation of male sexual function in mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2019. September;56(9):6310–6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blacklaws J, Deska-Gauthier D, Jones CT, Petracca YL, Liu M, Zhang H, Fawcett JP, Glover JC, Lanuza GM, Zhang Y. Sim1 is required for the migration and axonal projections of V3 interneurons in the developing mouse spinal cord. Dev Neurobiol. 2015. September;75(9):1003–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Wei W, Zinn AR, Wan Y. Sim1 inhibits bone formation by enhancing the sympathetic tone in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:1408–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haack KK, Zucker IH. Central mechanisms for exercise training-induced reduction in sympatho-excitation in chronic heart failure. Auton Neurosci. 2015;188:44–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Zhao Y, Chen S, Wang J, Xiao X, Ma X, Penchikala M, Xia H, Lazartigues E, Zhao B, Chen Y. Neuronal over-expression of ACE2 protects brain from ischemia-induced damage. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, Halabi CM, Becker LK, Santos RAS, Speth RC, Sigmund CD, Lazartigues E. Brain-selective overexpression of human angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;106:373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.