Abstract

Background

Ischemic stroke is a deadly disease that poses a serious threat to human life. Superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3, ECSOD) is the main antioxidant enzyme that removes superoxide anions from cells. This study aimed to investigate the effect of SOD3 overexpression on cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats.

Methods

GV230‐EGFP‐ECSOD, the recombinant SOD3‐overexpressed vector, was constructed by genetic engineering technology, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were infected with lentiviral packaging. In animal experiment, cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury model rats were successfully established. ECSOD‐MSCs are the MSCs that successfully transfected with SOD3 overexpression vector. The animals were injected with ECSOD‐MSCs (ECSOD‐MSC group), normal MSCs (MSCs group), PBS (PBS group), and not do any processing (Model group) via the tail vein. Then MRI was used to detect the infarct volume of rats, modified Neurological Severity Scores (mNSS), and immunohistochemistry were used to evaluate the expression of neurological function and apoptosis‐related genes in rats.

Results

Western blot analysis revealed that the SOD3 was highly expressed in MSCs. Animal experiments showed that the transplantation of ECSOD‐MSCs significantly reduced the infarct volume of ischemic stroke rats (p < 0.05), significantly improved neurological function in rats (p < 0.05), and found proapoptotic gene, Bax, expression was significantly decreased (p < 0.05), the expression of anti‐apoptotic gene, Bcl‐2, was significantly increased (p < 0.05). The highly expressed SOD3 has no correction with brain infarct volume, and the highly expressed SOD3 has a positive correlation with cell apoptosis. It is speculated that overexpression of SOD3 affects the expression of Bax and Bcl‐2, and improves apoptosis to alleviate ischemic stroke.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that MSCs transfected with SOD3 can effectively alleviate cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats.

Keywords: ischemic stroke, mesenchymal stem cells, protection, SOD3

1. INTRODUCTION

Ischemic stroke is a type of cerebrovascular disease (CVD) that threatens people's lives and is the leading cause of death worldwide (Malik et al., 2015; Paramasivam, 2015). Ischemic stroke accounts for about 80% of CVD, and it occurs mainly because of the cerebral blood artery embolism caused by atherosclerosis of cerebral vascular or thrombosis or vascular injury, which can cause cerebral ischemia and necrosis (Wiklund, Patnaik, Sharma, Miclescu, & Sharma, 2017). The key to treating ischemic stroke is to reconnect the occlusive vessels and restore the blood flow to the ischemic region, to save the brain tissue that faces the infarction (Kuo et al., 2017). At present, the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke is still unclear, and treatment methods are constrained.

The discovery of neural stem cells makes it possible to treat the neurodegeneration, cranial vascular disease, and central nervous system injury (Hardingham, Patani, Baxter, Wyllie, & Chandran, 2010; Jiang, Chen, Chen, & Shen, 2012). It is effective to transplant embryonic stem cells and neural stem cells in treating neurological diseases (Kwon, Ahn, & Kang, 2018); however, due to the inherent defects such as immunological rejection, difficulty in materials and ethics, the application is limited. In recent years, studies have shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) had the characteristics of stem cells, like highly self‐renewal and multi‐directional differentiation in vitro culture (Wei et al., 2009); what's more, there is no specific surface antigen on MSCs and the implantation reaction is weak, so MSCs have been considered to be an ideal target cells in gene therapy (Liu et al., 2010). Yoo et al. (2008) exposed that MSCs can improve the symptoms of cerebral hemorrhage in animal neurologic function with ischemia, it is shown that the MSCs can effectively promote the repair of nerve injury caused by cerebrovascular disease.

Ischemic stroke damages the nervous system through the oxygen free radical chain reaction, which aggravates brain tissue damage. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is the main antioxidant enzyme that removes superoxide anions in cells. Liu et al. (2012) proved that leonurine could protect brain injury by promoting SOD activity. And extracellular SOD (SOD3 or ECSOD, HGNC Approved Gene Symbol: SOD3, 4p15.2; OMIM: 185490) is the most important SOD in extracellular humoral (O'Leary, Bellizzi, Domann, & Mezhir, 2013), such as lymphatic fluid, synovial fluid, and plasma. SOD3 is a weekly hydrophilic glycoprotein with a molecular weight of 135,000 approximately. Each subunit of SOD3 consists of a copper and a zinc atom, which are necessary for the enzyme to remain active (Belda et al., 2013). Recently gene therapy studies have indicated that SOD3 has a good effect on some diseases caused by superoxide free radical (Shuvaev et al., 2013), Hattan, Chilian, Park, and Rocic (2007) found that SOD3 intervention can alleviate the symptom damage in coronary atherosclerosis.

Although the effect of MSCs on ischemic stroke in rats has been studied, the effect of MSCs cells transfected with SOD3 on ischemic stroke has not been reported until now. Therefore, the purpose of this study was investigating the effect of SOD3 transfection with MSCs on ischemic stroke.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Experimental animal

The animal experiment program was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Haikou People's Hospital and Yiyang Central Hospital. Male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Tianqin Laboratory Animal Center (Changsha, China). All rats were caged in an approved animal facility with free access to food and water, and were kept in a temperature‐controlled environment in a 12 hr light/dark cycle. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the United States National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85‐23, revised 1996).

2.2. Animal study

The rat model of cerebral ischemia reperfusion was established (Liu et al., 2011) and 80 male SD rats (100–140 days, 240–280 g) were divided into 6 hr group (n = 40) and 12 hr group (n = 40) according to the time of ischemia, then treated with different drugs. ECSOD‐MSCs are the MSCs that successfully transfected with SOD3 overexpression vector. The animals were injected with 1 × 105/μl ECSOD‐MSCs (ECSOD‐MSC group, n = 10), 1 × 105/μl normal MSCs (MSCs group, n = 10), PBS (PBS group, n = 10) and not do any processing (Model group, n = 10) via the tail vein.

2.3. MSCs cell culture and SOD3 transfection

Rats (28 days, 100–150 g) underwent abdominal anesthesia and cervical dislocation. MSCs were isolated from the femur and tibia for culture. The phenotype of MSCs was detected by flow cytometry. Next, total RNA of rat MSCs was extracted, and the primer sequence was sod3(6885‐1)‐P1 TCCGCTCGAGATMSCGGTGGCCTTCTTGTTCTGC, sod3(6885‐1)‐P2 ATGGGGTACCGTAGTGGTCTTGCACTCGCTCTCC. SOD3 was obtained by double digestion, and GV230‐EGFP‐ECSOD, the recombinant SOD3‐overexpressed vector was constructed. The production and titration of lentiviruses are based on the manufacturer's protocol.

The effect of SOD3 transfection was determined by fluorescence microscopy (×100) and real‐time quantitative PCR (qPCR). The experimental groups were as follows: vector infection group (con) without unlinked gene, group without vector infection (blank) and sod3 transfection (sod3).

2.4. Western blot

The cell culture medium was added to the RIPA lysate and centrifuged at 4 ℃ to obtain total protein. An equal volume of 5× loading buffer was added, mixed with boiling water for 5 min, the ice box was rapidly cooled, the sample was loaded and electrophoresed. The protein was then transferred to the NC membrane and Ponceau staining (Sigma‐aldrich trading co. LTD, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the efficiency of protein transfer. Hybridization was performed with the original antibody overnight at 4°C. After TBS‐T washing, it was incubated with HRP‐labeled secondary antibody for 60 min and washed with TBS‐T. Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo, Shanghai, China) was incubated with the NC membrane for 3 min to produce a rinse solution for analysis.

2.5. Detection of the effect of SOD3 transfection on MSCs

Three groups of cells were digested by 0.25% trypsin, forming single‐cell suspension with a concentration of 1 × 105/ml, plated them on 96‐well plate, and continuously cultured at incubator for 6 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. 150 μl DMSO measured the optical density (OD,) values at 490 nm every day, then the cell growth curve was plotted.

Three groups (sod3, con, and blank) of cells were added to the 96‐well plate, then by using EdU DNA Proliferation in vitro Detection kit (C10310, Guangzhou RiboBio Co., LTD, Guangdong, China) cell proliferation was detected according to the manufacturer's instructions. The staining was observed under a fluorescence microscope, and the image was obtained for EdU analysis.

2.6. Imaging for determination of infarct size in rats

Four groups (ECSOD‐MSCs, MSCs, PBS, and Model) of rats were scanned by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (GE signa HDX 3.0T MRI) at 1 day and 28 day after surgery to evaluate the changes in the area and volume of cerebral infarction.

2.7. Evaluation of neurological function

Evaluating modified Neurological Severity Scores (mNSS) scores in different time points: 1 day before the surgery, and after ischemia reperfusion at days 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, respectively, the scores mainly include exercise, feeling, balance, and reflection. One point is defined as failure to complete an experiment or test no response, and the higher the neurological deficit, the higher the score. The details were showed in Table S1.

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissue sections were placed in 5 μm thick paraffin for immunohistochemical staining, heating 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH = 6.0), in which tissue sections were soaked to repair antigen, and sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 to extinguish. And then, the endogenous enzyme was incubated, 50–100 μl of anti‐rat/rabbit HRP‐labeled polymer was added to incubate IgG‐HRP, and background stained sections were washed with PBS. Dyeing was performed using DAB operating fluid; sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, then dehydrated with alcohol and fixed with neutral glue, and finally observed under a microscope.

2.9. Statistical analyses

The experimental data were collated using Excel 2016 and analyzed using SPSS 21.0. Differences between groups were compared by one‐way analysis of variance, and differences between 6 hr and 12 hr were assessed by t test. The software of Quantity One analyzed the peak gray value of the western blot. Images were collected for immunohistochemical data analysis according to software Image‐pro‐plus (IPP). The results were described as mean ± standard deviation, p < 0.05 indicates that the difference was statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Successful acquisition of MSCs cells

The morphological changes of MSCs during the culture process were shown in Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis results were showed in Figure S2. The positive expression rates were as follows: CD29 (β1 integrin) positive rate was 95.7%, CD90 (MSCs surface glycophosphatidyl inositol) positive rate was 99.4%, and negative expression was CD34. (The negative rate of hematopoietic stem cell and endothelial progenitor cells was 98.0%, and the negative rate of CD45 (pan‐white cell marker) was 99.6%).

3.2. Overexpression of the SOD3 in MSCs

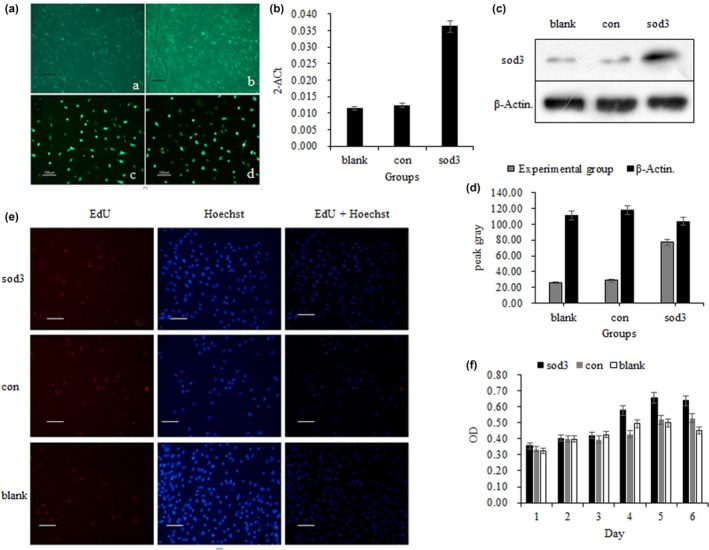

Fluorescence microscopy successfully detected green fluorescent cells (Figure 1a), and the SOD3 transfection efficiency was (75 ± 2.8)%. qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA expression level of the sod3 group was significantly increased (p < 0.05). The relative expression of the SOD3 in the sod3 group was approximately three times that of the blank group and the control group (Figure 1b). In addition, Western blot results showed that the SOD3 expression in the sod3 group was significantly higher than that in the blank group and the control group (p < 0.05, Figure 1c and d).

Figure 1.

Effect of the SOD3 on MSCs. A indicates the cell morphology observed by microscope (a is transfection 3d and b is 5d) and fluorescence microscope (c, d transfection 48 hr). (b) shows the content of mRNA carrying SOD3 in MSCs cells analyzed by qPCR. (c) indicates the electrophoretic stripe results. (d) indicates the grayscale value of protein imprinting. (e) indicates the results of the EdU assay for detecting cell proliferation and viability. (f) represents the MSCs proliferation capacity. Blank indicates the proliferation of MSCs without transfected SOD3, con indicates the proliferation of MSCs with transfected empty vector, and sod3 indicates the proliferation of MSCs after transfected SOD3

3.3. Effect of SOD3 on proliferation of MSCs

MTT assay showed that SOD3 transfection had no significant effect on cell proliferation of MSCs (p > 0.05, Figure 1f), that is, cell viability of MSCs was not affected after transfection of SOD3. And the EdU analysis showed similar results (p > 0.05, Figure 1e). It was suggested that the highly expressed SOD3 has no correction with cell proliferation.

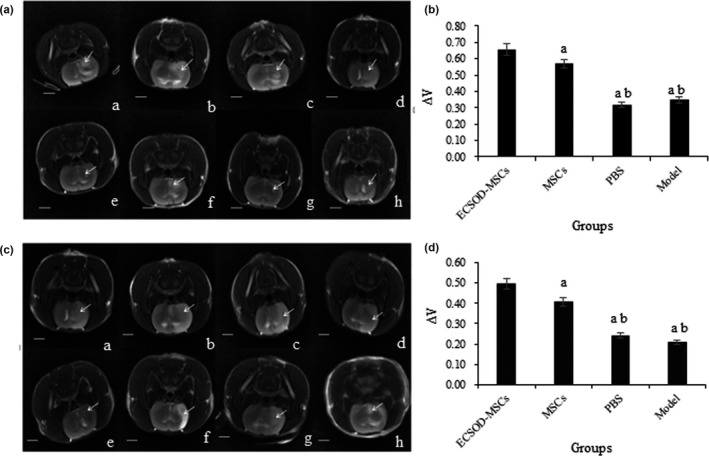

3.4. ECSOD‐MSCs decreased brain infarct volume

The results of MRI examination in the rat brain infarction area were shown in Figure 2a and c. The infarct volume of the other three groups was statistically significant compared with the ECSOD‐MSCs group (p < 0.05): and compared with the MSCs group, the infarct volume was significantly changed (p < 0.05) in the PBS and Model groups (Figure 2b and d). It was suggested that the highly expressed SOD3 has no correction with brain infarct volume.

Figure 2.

Shows the results of MRI examination after surgery in rats. (a, c) were MRI scan results of 6 hr and 12 hr groups respectively; a, b, c, d respectively indicated the infarct size of ECSOD‐MSCs group, MSCs group, Model group, and PBS group 1 day after operation; e, f, g, h respectively indicated the infarct size of the ECSOD‐MSCs group, the MSCs group, the Model group, and the PBS group at 28 days after operation. (b and d) were the results of the t tests in the 6 hr group and the 12 hr group, respectively. The arrow shows the infarction

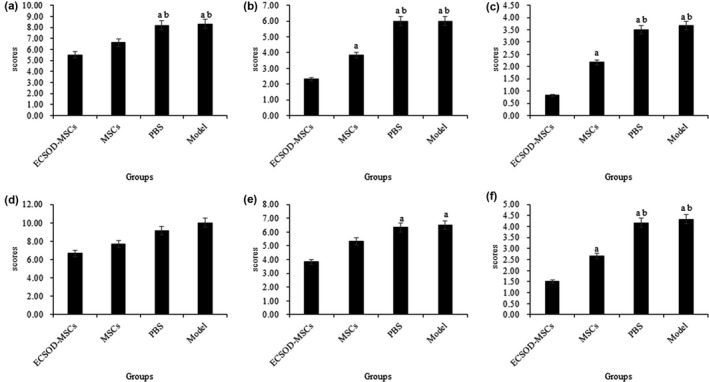

3.5. Administration of ECSOD‐MSCs improved neurological function

The mNSS scores at different time points after cerebral infarction in the 6 hr and 12 hr subgroups were presented in Figure 3 and Tables S2 and S3. The results showed that the mNSS scores at 14 day and 28 day after surgery at ECSOD‐MSCs groups were significant differences compared with three other groups (p < 0.05). The score of 7 day after surgery was not significantly different in the ischemic 12 hr group, but significantly different in the 6 hr group (p < 0.05). The mNSS scores were significantly different in PBS group and model group compared with the MSCs group (p < 0.05) at the time points of postoperative 7 day, 14 day, and 28 day.

Figure 3.

The mNSS scores at different time points after cerebral infarction in the 6 hr and 12 hr subgroups. The mNSS scores at 7 days (a), 14 days (b) and 28 days (c) in the 6 hr subgroups; The mNSS scores at 7 days (e), 14 days (f) and 28 days (g) in the 12 hr subgroups; a indicates that the group compared with the ECSOD‐MSCs group p < 0.05; b indicates that groups compared with MSCs p < 0.05

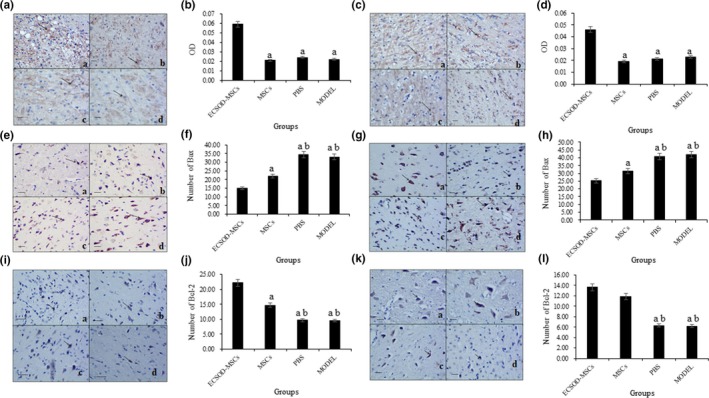

3.6. ECSOD‐MSCs reduced the apoptosis

Immunohistochemistry results showed that the expression of SOD3 in ECSOD‐MSCs group was significantly higher than that in the other three groups (p < 0.05), but there was no statistical difference among the MSCs group, the Model group, and PBS group (Figure 4a–d).

Figure 4.

The results of immunohistochemical detection. (a) indicates that the group compared with the ECSOD‐MSCs group p < 0.05; (b) indicates that groups compared with MSCs p < 0.05. (a and b) represents the expression of SOD3 in cytoplasm in 6 hr group. (c and d) are the expression of SOD3 in cytoplasm in 12 hr group. (e and f) indicate the number of Bax‐positive cells in the 6 hr group. (g and h) are the number of Bax‐positive cells in the 12 hr group. (I and j) are the number of Bcl‐2–positive cells in the 6 hr group. (k and l) show the number of Bcl‐2–positive cells in the 12 hr group

The Bax‐positive cells in PBS and Model groups were significantly higher than that in ECSOD‐MSCs group and MSCs group (p < 0.05), What's more, the Bax positive cells in ECSOD‐MSCs group was significantly lower compared to the other three groups (p < 0.05, Figure 4e–h).

Furthermore, compared with the other three groups, the number of Bcl‐2–positive cells in the ECSOD‐MSCs group was significantly higher in 6 hr group (p < 0.05), and compared with PBS group and Model group, the Bcl‐2 cells in MSCs group were significantly increased (p < 0.05, Figure 4i,j). In 12 hr group, the Bcl‐2–positive cells in group ECSOD‐MSCs and MSCs were significantly higher than that in PBS group and Model group (p < 0.05, Figure 4k,l). It was suggested that the highly expressed SOD3 has a certain correlation with cell apoptosis.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study showed that SOD3 was transfected into MSCs, which upregulated the expression of SOD3 in cerebral ischemic tissue, leading to a reduction in infarct volume and ultimately improved neurological recovery in a rat stroke model.

Previous studies have shown that MSCs play an important role in stroke disorders. Abiko et al. (2018) suggested that cMSCs had potential as a candidate cell‐based therapy for stroke. Wu et al. (2018) indicated that intracerebral transplantation of Wharton's jelly‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells (WJ‐MSCs) reduced neurodegeneration and inflammation in the stroke brain. We found that MSCs transplantation can significantly reduce the infarct volume and restore neurological damage in cerebral ischemia rats, especially the MSCs transfected with SOD3. Lin et al. (2013) showed that MSCs transplantation improves functional recovery and reduces the inflammatory responses in rats with cerebral ischemia. This research supports our results.

Moreover, we found that MSCs transfected with the SOD3 had a more pronounced effect on the relief of nerve damage. SOD is the main antioxidant in the body, it can inhibit the damage of active oxygen to the organism, and repair the damage caused by free radicals in time (Zhang, Zhou, & Zhang, 2018). Shuvaev et al. (2013) found that endotoxin‐induced cerebral vascular leukocyte adhesion was reduced by injecting Ab/SOD into mice, demonstrating that SOD could protect the brain from ischemia‐reperfusion injury. Förster and Reiser (2016) proved that SOD3 can protect brain from peroxide damage in rats. It indicates that SOD3 has protective effect on the damage caused by ischemia‐reperfusion injury. In our study, with the ischemic rat model of SOD3‐MSCs transplantation, the volume of cerebral infarction was significantly reduced, and the neurological function was significantly restored, indicating that the SOD3 has therapeutic effects on ischemic stroke. Sun et al. (2016) believe that upregulation of SOD3 can alleviate the damage caused by cerebral ischemia. Liu et al. (2012) improved the neurological damage in ischemic stroke rats by enhancing the activity of the SOD3. Additionally, Jun, Fattman, Kim, Jones and Dory (2011) demonstrated that SOD3 plays an anti‐inflammatory role and inhibits the asbestos‐induced injury in 129/J strain of mice. These are consistent with our results, demonstrating that the SOD3 is effective in ameliorating the damage caused by ischemic stroke.

The results of immunohistochemistry showed that the number of Bax‐positive cells was significantly decreased and the number of Bcl‐2 cells was significantly increased in rats transfected with ECSOD‐MSCs and MSCs. The Bax gene was considered to be a proapoptotic gene, while Bc1‐2 had the opposite biological function (Gawaly, 2016). It was suggested that ECSOD‐MSCs and MSCs had a mitigating effect on cerebral ischemic injury by altering the expression of Bax and Bcl‐2 genes. Miao et al. (2016) confirmed that Bcl‐2 expression was upregulated and Bax expression was weakened in the protective study of the nervous system in rats with ischemic stroke. Liu et al. (2017) protect neurons from ischemic stroke by regulating the expression ratio of Bcl‐2/Bax. A study showed that the expression of SOD3 in bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells reduced ROS level and cell apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro in ischemia/reperfusion injury (Pan et al., 2014). Similar to this result, anti‐apoptosis gene Bcl‐2 MSCs were also promoted by SOD3 overexpression in the present study. Therefore, we hypothesized that the SOD3 can decrease the expression of Bax protein, and increase the expression of Bcl‐2, thereby slowing the apoptosis of neurons, contributing to cell survival and protecting the nervous system.

Our results indicated that MSCs transfected with SOD3 can survived in the infarct area and continuously express the SOD3, this will not only reduce the damage to the reperfusion injury, but also promote the recovery of damaged brain tissue, which can improve the curative effect of reperfusion after ischemia.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this experiment, we preliminarily speculated on the role of SOD3 transfection of MSCs in the treatment of ischemic stroke. However, the specific mechanism of action needs to be further studied.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

SS and XH conducted experimental operations, data analysis, and draft manuscripts. HL participated in the research design, assisted in experimental operations, and performed statistical analysis. JP conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped in drafting the manuscript. YX designed, coordinated, and supervised the study and critically reviewed and discussed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the participants for their contribution to this study, thanks to the funding supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81360190) and pay tribute to the animals who sacrificed for the experiment.

Sun S, Gao N, Hu X, Luo H, Peng J, Xia Y. SOD3 overexpression alleviates cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7:e831 10.1002/mgg3.831

Shuaiqi Sun and Ning Gao are co‐first authors.

Funding information

This study received funding in the form of a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81360190). The funding source had not involved in the conduct of the research or preparation of the article.

REFERENCES

- Abiko, M. , Mitsuhara, T. , Okazaki, T. , Imura, T. , Nakagawa, K. , Otsuka, T. , … Kurisu, K. (2018). Rat cranial bone‐derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation promotes functional recovery in ischemic stroke model rats. Stem Cells and Development, 27(15), 1053–1061. 10.1089/scd.2018.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belda, R. , Blasco, S. , Verdejo, B. , Jiménez, H. R. , Doménech‐Carbó, A. , Soriano, C. , … García‐España, E. (2013). Homo‐ and heterobinuclear Cu(2)(+) and Zn(2)(+) complexes of abiotic cyclic hexaazapyridinocyclophanes as SOD mimics. Dalton Transactions, 42(31), 11194–11204. 10.1039/c3dt51012c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster, D. , & Reiser, G. (2016). Nucleotides protect rat brain astrocytes against hydrogen peroxide toxicity and induce antioxidant defense via P2Y receptors. Neurochemistry International, 94, 57–66. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawaly, A. (2016). BAX gene as a novel expressed tumor associated antigen in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Paper presented at the International Conference on Blood Malignancies and Treatment April.

- Hardingham, G. E. , Patani, R. , Baxter, P. , Wyllie, D. J. , & Chandran, S. (2010). Human embryonic stem cell‐derived neurons as a tool for studying neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Molecular Neurobiology, 42(1), 97–102. 10.1007/s12035-010-8136-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattan, N. , Chilian, W. M. , Park, F. , & Rocic, P. (2007). Restoration of coronary collateral growth in the Zucker obese rat. Basic Research in Cardiology, 102(3), 217 10.1007/s00395-007-0646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J. , Chen, X. , Chen, X. , & Shen, J. (2012). Neural stem cells A new target for drug discovery from Chinese medicine to promote neurogenesis in stroke treatment. Paper presented at the 2nd international neural regeneration symposium.

- Jun, S. , Fattman, C. L. , Kim, B. J. , Jones, H. , & Dory, L. (2011). Allele-specific effects of ecSOD on asbestos-induced fibroproliferative lung disease in mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 50(10), 1288–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, P.‐C. , Yu, I.‐C. , Scofield, B. A. , Brown, D. A. , Curfman, E. T. , Paraiso, H. C. , … Yen, J.‐H. (2017). 3H–1,2‐Dithiole‐3‐thione as a novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of ischemic stroke through Nrf2 defense pathway. Brain Behavior & Immunity, 62, 180 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, D. , Ahn, H. J. , & Kang, K. S. (2018). Generation of human neural stem cells by direct phenotypic conversion. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, 66, 103–121. 10.1007/978-3-319-93485-3_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q. M. , Zhao, S. , Zhou, L. L. , Fang, X. S. , Fu, Y. , & Huang, Z. T. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation suppresses inflammatory responses in global cerebral ischemia: Contribution of TNF‐alpha‐induced protein 6. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 34(6), 784–792. 10.1038/aps.2012.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. , Zhang, X. , Du, Y. , Ji, H. , Li, S. , Li, L. , … Cao, X. (2012). Leonurine protects brain injury by increased activities of UCP4, SOD, CAT and Bcl‐2, decreased levels of MDA and Bax, and ameliorated ultrastructure of mitochondria in experimental stroke. Brain Research, 1474, 73–81. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. , Zhang, Y. , Fan, L. , Yuan, M. , Du, H. , Cheng, R. , … Lin, F. (2011). Effects of transplantation with bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells modified by survivin on experimental stroke in rats. Journal of Translational Medicine, 9, 105 10.1186/1479-5876-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.‐S. , Deng, R. , Li, S. , Li, X. U. , Li, K. , Kebaituli, G. , … Liu, R. (2017). Ellagic acid protects against neuron damage in ischemic stroke through regulating the ratio of Bcl‐2/Bax expression. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism, 42(8), 855–860. 10.1139/apnm-2016-0651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. P. , Ding, D. C. , Wang, H. J. , Su, C. Y. , Lin, S. Z. , Li, H. , & Shyu, W. C. (2010). Nonsenescent Hsp27‐upregulated MSCs implantation promotes neuroplasticity in stroke model. Cell Transplantation, 19(10), 1261–1279. 10.3727/096368910X507204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M. O. , Govan, L. , Petrie, J. R. , Ghouri, N. , Leese, G. , Fischbacher, C. , … Mccrimmon, R. (2015). Ethnicity and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD): 4.8 year follow‐up of patients with type 2 diabetes living in Scotland. Diabetologia, 58(4), 716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J. , Wang, L. , Zhang, X. , Zhu, C. , Cui, L. , Ji, H. , … Wang, X. (2016). Protective effect of aliskiren in experimental ischemic stroke: Up‐regulated p‐PI3K, p‐AKT, Bcl‐2 expression. Attenuated Bax Expression. Neurochemical Research, 41(9), 2300–2310. 10.1007/s11064-016-1944-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary, B. R. , Bellizzi, A. M. , Domann, F. E. , & Mezhir, J. J. (2013). Extracellular superoxide dismutase (EcSOD) expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of Surgical Research, 179(2), 241–241. 10.1016/j.jss.2012.10.449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q. , Qin, X. , Ma, S. , Wang, H. , Cheng, K. , Song, X. , … Li, X. (2014). Myocardial protective effect of extracellular superoxide dismutase gene modified bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells on infarcted mice hearts. Theranostics, 4(5), 475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramasivam, S. (2015). Current trends in the management of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology India, 63(5), 665 10.4103/0028-3886.166547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuvaev, V. V. , Han, J. , Tliba, S. , Arguiri, E. , Christofidou‐Solomidou, M. , Ramirez, S. H. , … Muzykantov, V. R. (2013). Anti‐inflammatory effect of targeted delivery of SOD to endothelium: Mechanism, synergism with NO donors and protective effects in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE, 8(10), e77002 10.1371/journal.pone.0077002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S. , Chen, X. , Gao, Y. , Liu, Z. , Zhai, Q. , Xiong, L. , … Wang, Q. (2016). Mn‐SOD upregulation by electroacupuncture attenuates ischemic oxidative damage via CB1R‐mediated STAT3 phosphorylation. Molecular Neurobiology, 53(1), 331–343. 10.1007/s12035-014-8971-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, A. , Chung, S. A. , Tao, H. , Brisby, H. , Lin, Z. , Shen, B. , … Diwan, A. D. (2009). Differentiation of rodent bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into intervertebral disc‐like cells following coculture with rat disc tissue. Tissue Engineering Part A, 15(9), 2581 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund, L. , Patnaik, R. , Sharma, A. , Miclescu, A. , & Sharma, H. S. (2017). Cerebral tissue oxidative ischemia‐reperfusion injury in connection with experimental cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Effect of mild hypothermia and methylene blue. Molecular Neurobiology, 55(1), 115–121. 10.1007/s12035-017-0723-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.‐J. , Yu, S.‐J. , Chiang, C.‐W. , Lee, Y.‐W. , Yen, B. L. , Tseng, P.‐C. , … Wang, Y. (2018). Neuroprotective action of human Wharton's Jelly‐derived mesenchymal stromal cell transplants in a rodent model of stroke. Cell Transplantation, 27(11), 1603–1612. 10.1177/0963689718802754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S. W. , Kim, S. S. , Lee, S. Y. , Lee, H. S. , Kim, H. S. , Lee, Y. D. , & Suh‐Kim, H. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells promote proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells and survival of newborn cells in a rat stroke model. Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 40(4), 387–397. 10.3858/emm.2008.40.4.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. R. , Zhou, W. X. , & Zhang, Y. X. (2018). Improvements in SOD mimic AEOL‐10150, a potent broad‐spectrum antioxidant. Military Medical Research, 5(1), 30 10.1186/s40779-018-0176-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials