Abstract

Background

To develop liposomes loaded with iodinated agents as nanosized CT/MRI bimodal contrast agents for monitoring liposome-mediated drug delivery.

Methods

Rhodamine-labeled iodixanol (VisipaqueTM)-loaded liposomes (IX-lipo) were prepared and tested for their properties as a diamagnetic CEST contrast agent in vitro. Mice bearing subcutaneous CT26 colon tumors were injected i.v. with 1 g/kg (535 mg iodine/kg) IX-lipo, and in vivo CT and CEST MR images were acquired on day 3. CT and CEST MR images were also acquired for tumor-bearing mice co-injected with IX-lipo and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α).

Results

In addition to CT contrast, IX-lipo exhibited a strong CEST contrast similar to its non-liposomal form, with a detectability of ~2 nM per liposome. Both CT imaging and CEST MRI showed that i.v. injection of IX-lipo resulted in a rim enhancement of CT26 tumors with a heterogeneous central distribution. In contrast, co-injection of TNF-α caused a significantly augmented CT/MRI contrast in the tumor center. The intratumoral biodistribution of IX-lipo correlated well to the rhodamine patterns observed with fluorescence microscopy.

Conclusions

We have developed a CT/MRI bimodal imaging approach for monitoring the delivery and biodistribution of liposomes by loading them with the clinically approved X-ray/CT contrast agent iodixanol. Our approach may be easily adapted for other-FDA approved iodinated agents and thus has great translational potential.

Keywords: Iodixanol, chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging (CEST MRI), computed tomography (CT), liposomes, vascular-targeting therapy, enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR effect)

Introduction

Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of chemotherapeutics to tumors offers great advantages over conventional systemic administration. The use of liposomes, micelles, nanocrystals, quantum dots, and iron oxide nanoparticles as drug carriers enables the preferential delivery of drugs to tumors owing to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (1-4), and allows the delivery of more than one agent for combination therapy and/or for combined therapy and diagnosis (theranostics). Pre-clinical studies have shown that nanoparticle systems can significantly improve the therapeutic index of drugs by reducing drug toxicity and enhancing drug efficacy in the solid tumors caused by their increased and defective vascularity and impaired lymphatic drainage. The successful development of nanomedicine has led to more than 20 nanoparticle therapeutics approved by FDA (5,6). However, the overall increase of cancer patient survival rates has remained modest (7,8). It is now well accepted that human solid tumors are significantly different from those present in small animal tumor models in several aspects, with a more heterogeneous vascular anatomy and function, preventing the use of the EPR effect as an effective therapeutic pathway (9,10). Non-invasive imaging modalities can be expected to play an important role to visualize these and other differences in drug delivery. The imaging information can then be used to determine the pharmacokinetic and biodistribution profiles of injected drug delivery systems and assess whether a sufficient amount of drugs is delivered to the specific target of interest to become therapeutically meaningful.

The majority of the clinical studies of image-guided drug delivery to date have been performed using nuclear imaging modalities, including planar gamma scintigraphy, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) (11). While nuclear imaging has been widely used to study the pharmacokinetics of liposomal drugs, PET (e.g., 18F, 68Ga, and 11C) and some SPECT (e.g., 99mTc and 123I) radioisotopes have short physical half-life, making nuclear imaging sometimes limited by short imaging time window. Moreover, nuclear imaging modalities can’t provide anatomical information directly and require an expensive infrastructure (radiochemists, cyclotron). In contrast, computed tomography (CT) can use of-the-shelf contrast agents with an infinite half-live, and provides anatomical information with high spatial (submillimeter) and temporal resolution. It can also be used for quantification of the macro-distribution of drug carriers when co-encapsulating iodinated agents (12-15). Contrast-enhanced CT imaging has allowed the longitudinal investigation of long-circulating nanoparticles. Iodinated agents such as iohexol (14,16,17), iopromide (18) and iodixanol (19-21) have been encapsulated in the lumen of liposomes to construct CT-trackable liposomes, which have been used in human studies (22). However, the high dose of ionizing radiation of CT limits its clinical applicability, especially in scenarios for which repeated scans are needed. MRI, on the other hand, has excellent soft tissue contrast and a relatively high spatial resolution that does not employ ionizing radiation. There are many ongoing efforts to develop MRI-based image-guided drug delivery approaches in animals. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been only one clinical study reported on the use of MRI-guided drug delivery in patients, in which superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles were used as an indirect surrogate marker for tumor deposition of nal-IRI (MM-398, Onivyde®), a liposomal formulation of the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan (23). Therefore, further studies on clinically applicable MRI methods for image-guided drug delivery are warranted.

There has been a great interest to develop multimodality imaging to combine the advantages and overcome the limitations of each single imaging modality, and to ultimately improve the precision of imaging by combining the (complementary) information generated by each modality. Dual-mode CT/ MR imaging has been of great interest and extensive efforts have been made on developing bimodal nanoparticles prepared by either co-encapsulation of CT and MRI contrast agents within the nanoparticle drug carriers (16,24) or using chemically fabricated metal-based nanoparticles (25,26). Despite the great potential demonstrated in animal studies, the clinical translation of new Gadolinium-based probes is often impeded by safety concerns. Therefore, nanoparticle probes that can be used for dual-mode CT/MR imaging with a minimal translational barrier are highly desirable. Inspired by several recent studies (27-31), in which iodinated X-ray/CT agents were used as diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI (32-35) contrast agents, we hypothesized that nanoparticles can be endowed with both CT and MRI contrast by encapsulating one of these iodinated agents. In the current study, we encapsulated liposomes with iodixanol (Visipaque, GE, Figure 1A) and tested its utility in assessing the tumor uptake of nanoparticles in a murine colon tumor model with and without injection of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) as a vascular disrupting agent. It is shown that, by loading a single clinically used X-ray/CT agent, the liposome system can be tracked by both CT and MRI, providing a highly translatable way to pursue image-guided drug delivery.

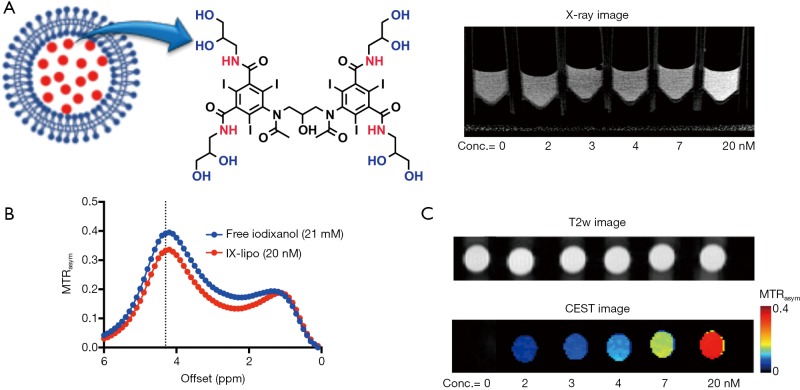

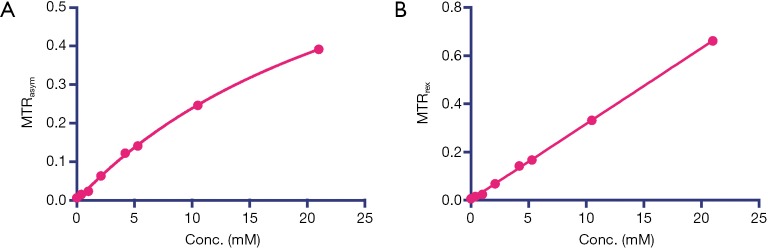

Figure 1.

Construction of iodixanol-encapsulated liposomes (IX-lipo) for dual CT/CEST MRI detection. (A) Illustration of IX-liposome using iodixanol with its chemical structure shown on the right. (B) MTRasym plots of 20 nM IX-lipo and 21 mM iodixanol solution. (C) CEST contrast at 4.3 ppm for IX-lipo at concentrations ranging from 2 to 20 nM. The lowest level of detection using our experimental parameters is 2 nM of liposomes which is approximately equivalent to 2 mM iodixanol. CEST MRI, chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging.

Methods

Chemicals

1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-phosphoethanolamine poly(ethylene glycol)2000 (DSPE-PEG-2000) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Cholesterol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Clinical grade Iodixanol (Visipaque) was purchased from GE Healthcare (Iodixanol 652 mg/mL or 320 iodine mg/mL, solution for injection). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Liposome preparation and characterization

Liposomes (DPPC: cholesterol: DSPE-PEG-2000 =57:40:3 and 0.2% Rhodamine-B-PE) were formed by the lipid film hydration method as described previously (36-38). In brief, 25 mg/mL of lipid mixture dissolved in chloroform was air-dried for 90 min and vacuumized for 30 min. The lipid film was hydrated with 2 mL iodixanol solution (420 mM) overnight at room temperature. Then the hydrated solution was sequentially extruded with 400 nm and 200 nm polycarbonate membranes. Unencapsulated iodixanol was removed by dialysis against 50× volume of PBS for 24 hours using a dialysis cassette (cut off =10 kD, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The size and distribution (polydispersity index, PDI) were measured at room temperature by dynamic light scattering using a Nanosizer ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, Southborough, MA) (39). The concentration of liposomes was measured using the colorimetric Stewart assay (40). To determine the concentration of iodixanol encapsulated in liposomes, the IX-lipo preparation was ruptured by sonication in 10% v/v Triton X-100 solution at 42 °C for 15 min. After centrifugation (15,000 ×g) for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and measured for UV absorbance at 246 nm using a V-630 UV/vis spectrophotometer (JASCO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The concentration of iodixanol was calculated using a pre-determined standard curve.

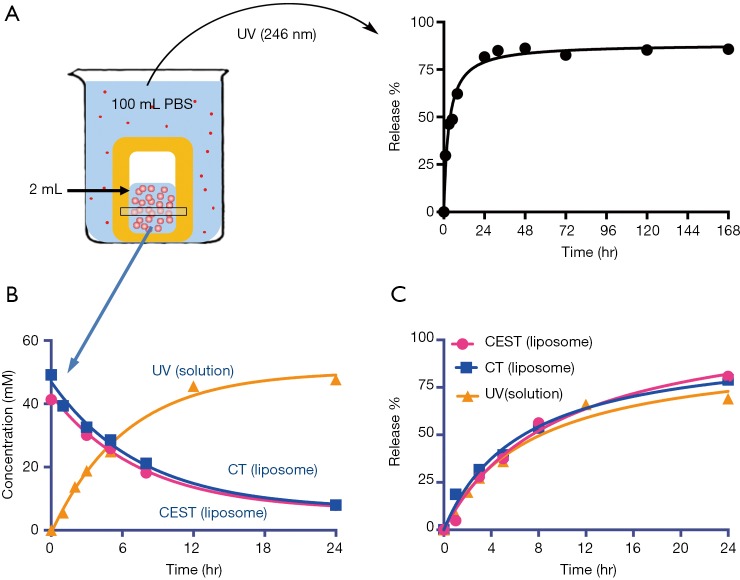

The release kinetics of the encapsulated iodixanol from liposomes were measured by a dialysis method as described previously (36). In brief, 2 mL of purified IX-lipo was transferred to a dialysis cassette (cutoff =10 kD) and immersed in 100 mL PBS at room temperature for up to 7 days. The dialysate was periodically measured for UV absorbance (246 nm). At 1, 3, 5, 8 and 24 hours, the liposome solution inside the dialysis cassette (pH=7.4) was also measured for CEST MRI signal and CT values.

In vitro X-ray and CEST MRI measurements

The CT contrast of all the samples were measured using a Faxitron MX-20 radiography system (Faxitron-Bioptics, Tucson, AZ) with an exposure time of 10 s at 30 kV. Images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The Hounsfield units (Hu), defined as 1,000× (µ − µwater)/(µwater − µair)], was calculated, where by µ is the X-ray attenuation.

In vitro CEST MRI images were acquired on a Bruker 11.7T vertical bore system (Bruker Biosciences, Billerica, MA) equipped with a 15 mm birdcage RF coil as described previously (41) using a modified rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence (TR =6.0 sec, effective TE =43.2 ms, RARE factor =32, slice thickness =2 mm, FOV =13×13 mm, matrix size =128×128, resolution =0.102×0.102 mm, and NA =2) with a continuous wave saturation pulse (tsat =4 s, B1 =3.6 µT) swept from −6 to 6 ppm (increment 0.2 ppm). B0 inhomogeneities were measured and corrected using Water Saturation Shift Referencing (WASSR) (41,42). As temperature can affect the proton exchange rate, hence affecting the CEST MRI signal, all in vitro CEST MRI were acquired at 37 °C.

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. CT26 (CRL-2638) murine colorectal adenocarcinoma cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in McCoy’s 5A Medium (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, HyClone, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Five million CT26 cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), and allowed to grow for ~7–12 days, until they reached a size >500 mm3. Mice were randomly separated into three cohorts with n=4 each. In the first and second groups, mice were intravenously (i.v. tail vein) injected with IX-lipo (535 mg iodine/kg, or 1 g/kg iodixanol) or empty liposomes (vehicle control). In vivo 3D CT imaging was performed before or at 24, 48 and 72 hours after liposome injection, and CEST MR images were acquired at 72 hours after injection of IX-lipo or empty liposomes. The time points were chosen as it was indicated by several previous studies that the peak intratumoral accumulation of liposomes occurred between 24 hours (43) and 72 hours (44). In the third group, each mouse was intravenously injected with 1 µg TNF-α (10 µg/mL in PBS containing 0.1% BSA) together with IX-lipo. CT and MRI images were acquired at 3 days after the injection.

In vivo CT imaging

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and CT images were acquired using an IVIS® Spectrum CT system (Perkin Elmer) with the following parameters: 50 kV, 1 mA, 50 msec exposure, and 720 projections. CT images were reconstructed and processed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The CT values were normalized at each time point using the equation (µ − µair)/(µbone − µair), allowing a direct quantitative comparison between different studies. Relative changes in the CT values after liposome infusion were defined as ∆CT(t) %= [CT(t) − CT(t=0)] /CT(t=0) ×100%.

In vivo MR imaging

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and positioned in an 11.7 T horizontal bore Bruker Biospec scanner. CEST images were acquired using the same imaging pulse sequence described above, with the addition of a fat-suppression pulse (3.4 ms hermite pulse, offset =−3.5 ppm) between the saturation pulse and RARE acquisition. The acquisition parameters were: TR =5.0 sec; effective TE =6 ms; RARE factor =20; tsat =3 sec; B1 =2.4 µT; slice thickness =1 mm; acquisition matrix size =64×64; FOV =25×25 mm; and NA =2. All data were processed using custom-written Matlab scripts. CEST contrast was quantified by calculating the asymmetry in the magnetization transfer ratio (MTRasym) using MTRasym = (S-Δω – S+Δω)/S0. S0 is the signal of water without saturation, and SΔω is the water signal upon the saturation pulse irradiated at the offset of Δω with respect to the water resonance. For ROI analysis, ROI masks were drawn manually based on the co-registered T2-weighted images.

Fluorescence microscopy

All histology and fluorescence microscopy evaluation were performed after the last MRI scan at 72 hours post-injection unless otherwise noted. Immediately after MRI, mice were sacrificed and tumors were excised and processed for histology as described previously (37). Tumor sections of 10 µm were stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclei and examined under an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) for the distribution of Rhodamine-B-labeled liposomes.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SD and analyzed by an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test assuming equal variance. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

Physicochemical and CEST properties of iodixanol-encapsulated liposomes

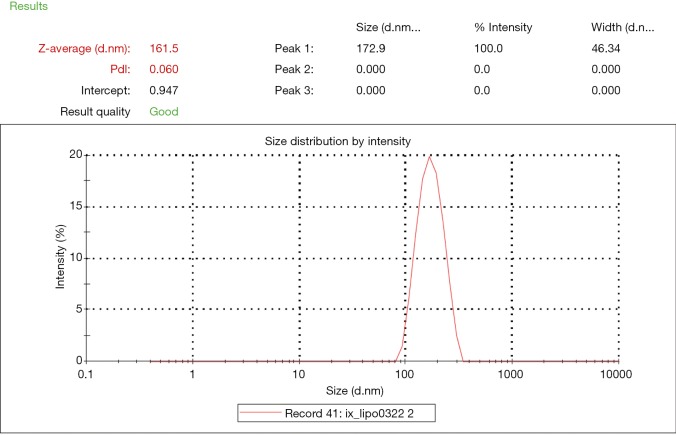

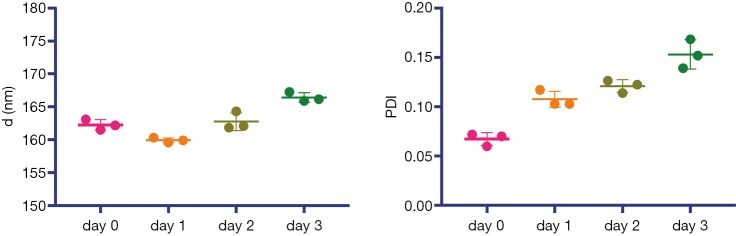

The iodixanol-encapsulated liposomes (IX-lipo, Figure 1A) had an average hydrodynamic diameter of 162.3±0.8 nm (PDI =0.067±0.006) as measured by DLS (Figure S1). The size and PDI of liposomes were found to be stable in the presence of serum protein (i.e., 50% fetal bovine serum) at 37 °C (Figure S2). After the removal of unencapsulated iodixanol from the solution by dialysis for 24 hours, the total concentration of iodixanol encapsulated in liposomes was 43 mM as measured by UV (246 nm), with an encapsulation efficiency of ~10%.

Figure S1.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurement of the size and distribution of the prepared liposomes.

Figure S2.

Liposome size (diameter d) and PDI at different time points after the incubation in 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C.

Figure 1B shows the CEST (MTRasym) signal of a 20 nM solution of IX-lipo (pH=7.4), in which the concentration of iodixanol was determined as 16.4 mM by UV absorbance measurements. Compared to the non-liposomal form of iodixanol (21 mM), the pattern and magnitude of CEST signal intensity were quite similar, with both exhibiting strong CEST peaks at 4.3 ppm (amide protons, marked in red in Figure 1A) and 1.0 ppm (hydroxyl protons, marked in blue in Figure 1A). Under a saturation condition of B1 =3.6 µT and tsat =4 seconds, 20 nM IX-lipo generated an MTRasym of 0.33±0.04 at 4.3 ppm, indicating that the CEST MRI detectability of IX-lipo is on the order of 1–2 nM.

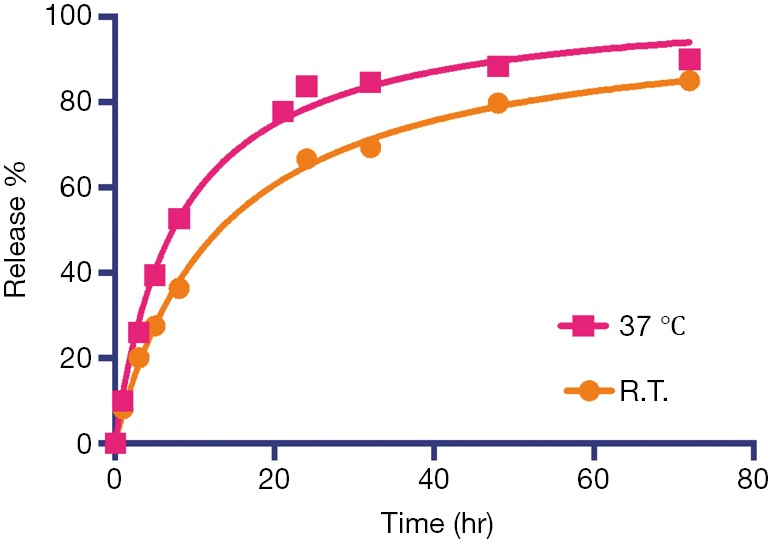

Using the experimental settings shown in Figure 2A, we used UV absorbance at 246 nm to monitor the iodixanol release from liposomes for up to 7 days. The release kinetics exhibited a two-phase pattern, with a fast release of more than 50% of the entrapped iodixanol within the first 12 hours, and then a slow release over the rest of the period studied, with 14.3% of originally loaded iodixanol remaining in the liposomes after 7 days. A slightly faster release rate but similar release profile was observed when the liposomes were incubated at 37 °C compared to room temperature (Figure S3). We then used MRI and X-ray to measure the release kinetics over the first 24 hours, which showed similar results as the UV measurement. The concentrations (Figure 2B) and the release rate (Figure 2C) of the iodixanol measured by UV agreed well with the retained iodixanol measured by X-ray and CEST MRI using our predetermined calibration curves (Figure S4), confirming the ability to use both CT and MRI to monitor drug delivery and release of IX-lipo. Our results also show that a relatively stable concentration of iodixanol remained inside liposomes between 1 and 7 days. Thus, the experimental system allows quantification of liposomes over a prolonged time window.

Figure 2.

In vitro release of iodixanol from IX-lipo. (A) Left: illustration of the release experiment in which the IX-lipo containing dialysis bag is immersed in PBS. The dialysate is measured at 246 nm (UV) intermittently to monitor iodixanol release. Right: representative release profile. (B) Concentration of iodixanol retained in liposomes measured by CT and CEST MRI as compared to the concentration released as measured by the UV absorbance in the solution and back-calculated to the concentration inside liposomes using a volume ratio of 100:2. (C) Time dependence of iodixanol release obtained from all three methods. CEST MRI, chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure S3.

Comparison of the iodixanol release at 37 °C and room temperature (R.T., ~20 °C).

Figure S4.

Calibration curves for the CEST signal of iodixanol in solution using (A) MTRasym and (B) MTRrex. For the MTRasym, as it is only linear when the concentration is low (i.e., <10 mM), we used a non-linear Michaelis-Menten curve fitting. The MTRrex was calculated from the reciprocal format of Z-spectrum by MTRrex (∆ω) = S0 / Ssat (+∆ω) – S0 /Ssat (–∆ω). A good linearity was found between the MTRrex signal at 4.3 ppm and iodixanol concentrations (Y=0.0316X, R2=0.9994).

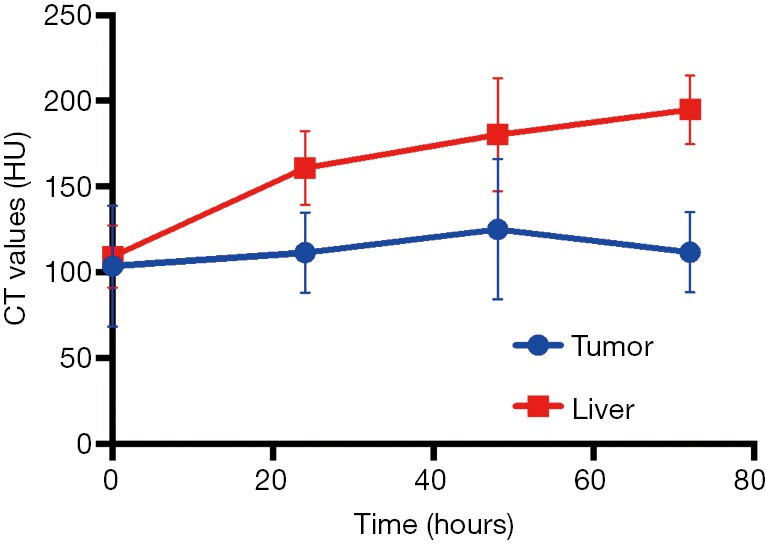

In vivo CEST MRI/CT detection of the intratumoral distribution of intravenously injected IX-lipo

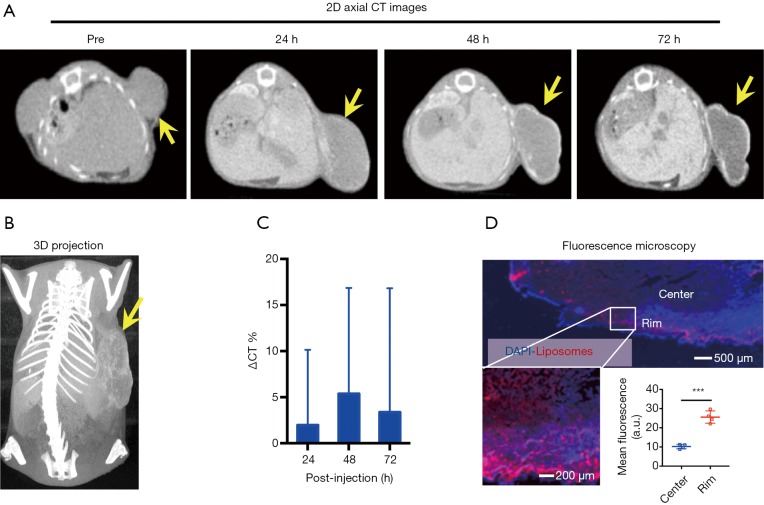

We first used micro-CT to monitor the tumor uptake and distribution of IX-lipo longitudinally for up to 72 hours post injection. As shown in Figure 3A,B, the injected IX-lipo preferentially accumulated in the liver and resulted in a strong CT contrast for up to 72 hours (Figure S5). In the tumor, the overall relative changes ∆CT(t) integrated over the whole tumor were 2%, 5.4%, 3.4% at 24, 48 and 72 hours, respectively (Figure 3C). The mean CT contrast in the tumor at different time points was determined to be not significantly different from that of pre-injection (P=0.7402, 0.4701, and 0.6807, respectively; n=4, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). Notably, very large standard deviations can be seen in Figure 3C, consistent with the CT images shown in Figure 3A,B, indicative of a low uptake and highly heterogenous distribution of IX-lipo, leading to a very low signal difference calculated over the whole tumor. Tumor regions showed a rim enhancement pattern that became more conspicuous at the later time points, at which some regions in the tumor rim showed >10% change in CT contrast at 48- and 72-hour post-injection. Finally, the CT results were consistent with the histological findings, In particular, Figure 3D shows that IX-lipo predominantly accumulate in the periphery regions of the tumor at 72 hours after injection, consistent with the distribution of microvessels in the CT26 tumors, which is highly heterogeneous and the majority of vessels was located in the periphery of the tumor (Figure S6). The contrast-enhancement is not likely due to the free iodixanol released from the liposomes, as the clearance of free iodixanol has been reported to be very fast (45), which was confirmed in our animal model by injecting non-liposomal form of iodixanol (Figure S7).

Figure 3.

CT imaging of the uptake and distribution of IX-lipo in CT26 tumors. (A) 2D axial CT images of a representative mouse at different time points; (B) 3D CT images of a mouse at 72 hours post-injection; (C) Relative changes in mean CT values of the entire tumor post-injection; (D) Fluorescence microscopy images confirming the distribution of IX-lipo in the tumor, with rhodamine-labeled IX-lipo shown in red and cell nuclei in blue (DAPI). In panels A and B, tumors are indicated by yellow arrows.

Figure S5.

Mean Hounsfield units (HU) of the tumor and liver in mice receiving IX-lipo (n=4) as the function of post-injection time.

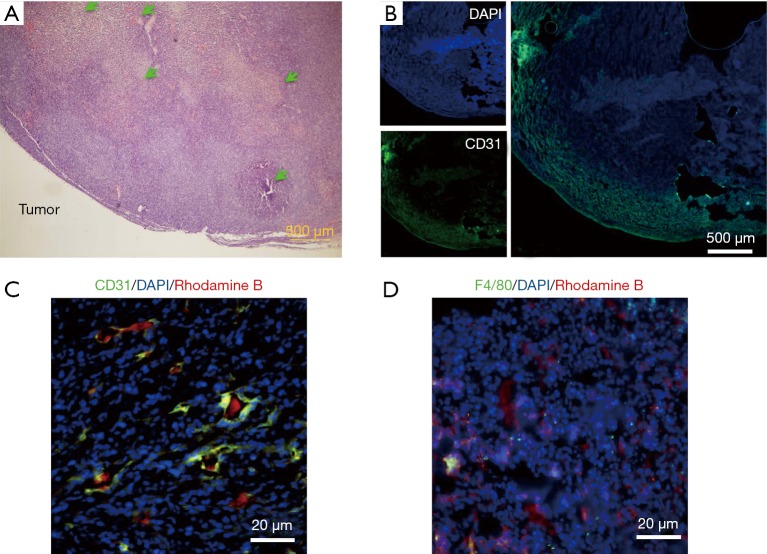

Figure S6.

Histological results. (A) H&E staining of a representative CT26 tumor, which contains large necrotic areas as pointed by the light-green arrows. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy (4×) of CD31 staining of the tumor to show the distribution of microvessels; (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy at high magnification (40×) showing the distribution of liposomes (red) with respect to blood vessels (CD31, green). (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy at high magnification (40×) showing the distribution of liposomes (red) with respect to macrophages (F4/80, green).

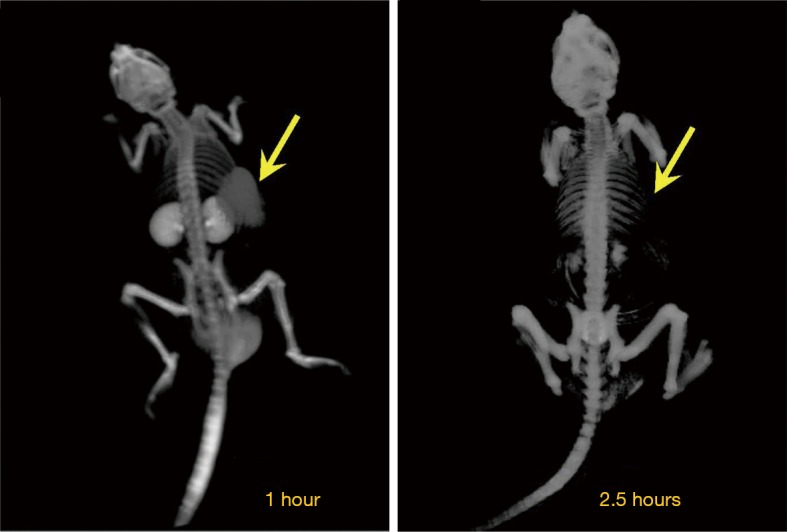

Figure S7.

CT images of a representative tumor-bearing mouse at 1 and 2.5 hours after i.v. injection of 500 mg iodine/kg iodixanol. The tumor is indicated by the yellow arrows.

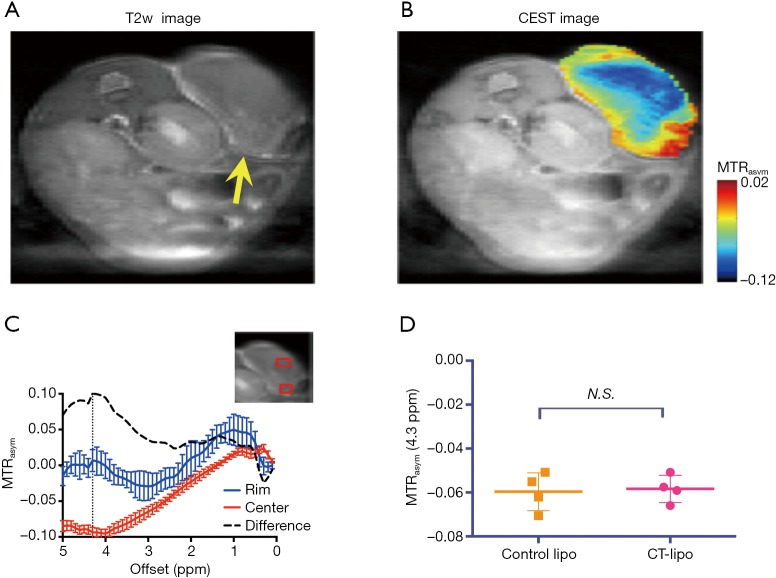

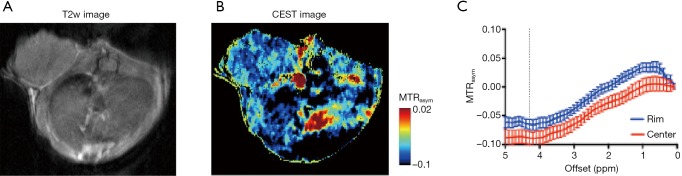

At the final time point (i.e., 72 hours post injection), we also assessed the CEST MRI signal in the tumor in an axial slice that was chosen to cover the largest tumor area (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, our results confirmed the CT data in showing a strikingly strong CEST signal (at 4.3 ppm) in the tumor periphery while the signal is much weaker in the center, which is strikingly different from that pre-injection (Figure S8). It is worth mentioning that the difference between MTRasym plots from the tumor rim and core resembled closely the MTRasym plot of IX-lipo in vitro (Figure 4C vs. Figure 1B), suggestive of the good specificity of the CEST MRI signal at 4.3 ppm for assessing intratumoral distribution of the iodixanol-based IX-lipo in vivo. Compared to mice injected with blank liposomes, which showed no contrast enhancement either in the center nor in the rim of the tumors, as shown in Figure 4D, the increase of whole-tumor CEST signal injected with IX-lipo was not significant (−0.060±0.004 and −0.058±0.001 for blank liposomes and IX-lipo respectively, P=0.816, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test, n=4), indicative of, consistent with the CT results, a weak tumor uptake of IX-lipo in CT26 tumors.

Figure 4.

CEST MRI of the uptake and distribution of IX-lipo in CT26 tumors at 72 hours after injection. (A) T2-weighted image of the same tumor (arrow) as shown in Figure 3A. (B) Overlaid image showing the CEST map in the tumor at 72 hours after injection; (C) mean MTRasym plots of two regions as indicated by red boxes in inset, representative of tumor rim and center respectively. (D) Scatter plots of the mean CEST signal at 4.3 ppm of the entire tumors in the mice injected with IX-lipo or empty liposomes, respectively. CEST MRI, chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure S8.

CEST MRI of CT26 tumors before injection. (A) T2-weighted image, (B) CEST map, and (C) Mean MTRasym plots for tumor rim and center respectively. CEST MRI, chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging.

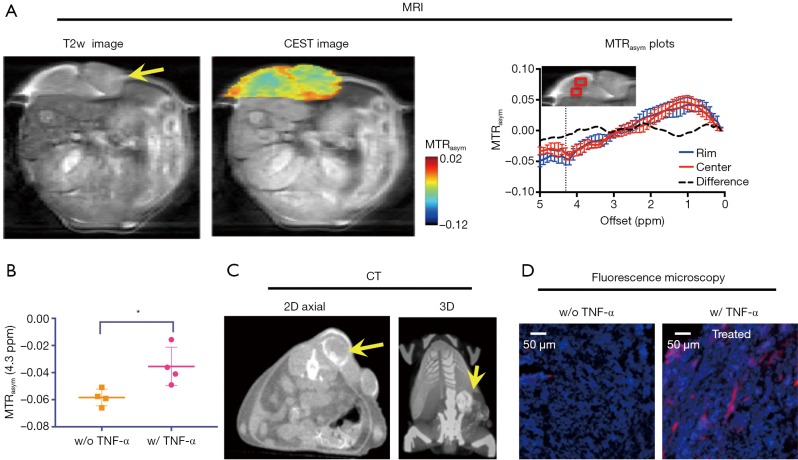

In vivo CEST MRI/CT imaging of the effect of TNF-α on the tumor uptake of IX-lipo

In Figure 5A, CEST MRI results of a representative mouse are presented, showing a distinctive pattern of tumor uptake and distribution of IX-lipo in TNF-α treated mice at 72 hours after injection. Compared with the tumor without TNF-α treatment, the periphery area showed the highest CEST contrast, but there was also a pronounced augmented CEST signal throughout the tumor. As a result, there was a significant increase of whole-tumor uptake of IX-lipo, with a mean CEST signal increase of nearly 40% (−0.058±0.001 vs. −0.036±0.014 for non-TNF-α and TNF-α treated groups respectively, P=0.0258, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, n=4, Figure 5B). In good agreement with the MRI findings, CT imaging (Figure 5C) also indicated a strong uptake in the center of the tumors for TNF-α treatment. The CEST MRI and CT results were further verified by fluorescence microscopic analysis of tumor sections (Figure 5D), which revealed enhanced penetration of red-fluorescence IX-lipo (by the conjugated rhodamine-B) into the center of TNF-α-treated tumors.

Figure 5.

CEST MRI and CT bimodal detection of the uptake and distribution of IX-lipo in TNF-α-treated CT26 tumors at 72 hours after injection. (A) From left to right: T2-weighted image, overlaid image showing the CEST map of the tumor (pointed by the arrow) at 72 hours after injection in a representative mouse that was treated with 1 µg TNF-α, and the mean MTRasym plots of two regions as indicated by the red boxes in the insert. (B) Comparison of the mean tumor CEST signal between TNF-α-treated and non-treated tumors (P=0.0258, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, n=4). (C) Corresponding CT images of the same mouse, with the tumor indicated by arrows; (D) Fluorescence microscopic images showing the distribution of IX-lipo in the center of the tumor, with rhodamine-labeled IX-lipo shown in red and cell nuclei in blue (DAPI).

Discussion

We investigated the capability of iodinated liposomes for CT/MRI bimodal imaging, providing a new platform imaging technology for monitoring liposome-mediated drug delivery. This would be useful, for instance, for an assessment of tumor drug uptake as related to the tumor vasculature makeup [EPR effect (44)]. We used a strategy where both the CT and MR imaging contrast is produced by a single clinical X-ray/CT agent, i.e., iodixanol. The CEST and CT contrast of iodixanol was found to be well-preserved after encapsulation, achieving a liposome detectability in the nM concentration range. Using IX-lipo, we were able to visualize tumor uptake and intratumoral distribution in a mouse tumor model with both CT and MRI. Moreover, we showed that this technique can be used to assess the augmented tumor uptake of nanoparticles when using TNF-α as a vascular disrupting agent.

This new technology combines the advantages of CT and MRI while using only a single agent. CT imaging allows the whole-body assessment of the delivery and distribution of liposomes with a superior spatial-temporal resolution, while CEST MRI provides specific detection of iodixanol by its signature amide peak at 4.3 ppm. While CT can also be used to quantify the tumor uptake of the injected liposomes (12,43), its quantification relies on the changes in CT attenuation and therefore lacks specificity unless a dual-energy spectral CT scan is used (46). CEST MRI, on the other hand, can assess the changes at a particular frequency offset, thus providing a higher specificity. In addition, CEST MRI can provide a comprehensive assessment of the intratumoral distribution of the injected nanoparticles by combining with other MRI anatomical and functional contrast mechanism such as T2w and diffusion weighted MRI. Finally, CEST MRI allow repeated uses as there is no risk for ionizing radiation. Another advantage of using CEST MRI with iodinated CT agents is the ability to assess tumor pH (31,47) as was recently demonstrated (27,35,48). More importantly, several studies have been reported that use iodinated X-ray contrast agents at 3T, including both a small animal scanner (35) and human scanners (30,49), indicating good potential for clinical translation (50).

Our study relies on the inherent CEST MRI signal of the amide protons of clinical X-ray/CT agents, which have been investigated recently for different applications, including characterization of tumor perfusion (27,51) and pH mapping of tumors (31,47,48) and kidneys (28,52). However, a high dose of CT contrast agent has to be injected to achieve a sufficient contrast. For example, in the studies by Longo et al. (27) and Anemone et al. (51), a dose of 4 g iodine/kg was used to generate a 60% contrast enhancement. Using nanoparticle agents can significantly reduce the required dose and increase safety by concentrating the agent in the tumor through the EPR effect. In our study, we were able to achieve sufficient CEST MRI contrast with a dose of 535 mg iodine/kg (or 1 g/kg iodixanol). Similar doses have been used for CT imaging of liposomes in the tumor (12,20) and macrophages in the atheroma (13). Our dose is slightly higher than the dose used by Pagel et al. [i.e., ~300 mg iodine/kg (48)], however, with a much stronger contrast in the tumor. Clinically, patients are usually injected i.v. with ~2 g/kg iodixanol. Hence, our dose is within the safe range.

Liposomal X-ray/CT contrast agents have been exploited for liver and spleen CT imaging (53) in the early 1980s, and later for CT blood-pool imaging (54). While the majority of the studies were performed in preclinical animal models, several clinical studies have been reported (22,55). Compared to the agents in the free form, encapsulation in liposomes is advantageous because of the improved biodistribution, prolonged blood circulation time, and reduced nephrotoxicity. As a natural extension of these previous studies, our study explored the use of liposomal iodinated agents for CT/MRI dual modal imaging of the delivery and distribution of nanoparticle drug carriers. However, different from the ‘classic’ formulations that were used in these studies, the liposomes used in the present study were stealth liposomes, grafted with PEG on the surface (pegylation) to achieve a substantial reduction in the rapid clearance rate of liposomes by preventing the opsonization of liposomes by serum proteins (56,57). As a result, stealth liposomes have a much longer long circulation time in animals and humans with improved therapeutic outcomes (58).

We chose iodixanol (Visipaque) in our study because its liposomal form was investigated successfully previously in clinical trials for liver and spleen CT imaging (22). While the formulation and size of the liposomes used in that study were different, its findings are supportive for future clinical translation of our technique. Moreover, the study by Longo et al. (27) showed that the CEST MRI signal of iodixanol (per molecule) is stronger than other three FDA-approved agents, i.e., iomeprol (Iomeron), iohexol (Omnipaque), and ioversol (Optiray). Finally, iodixanol is the only iso-osmolar contrast agent (with respect to blood, osmolality =290 mOsm/kg). As a result, the release rate of iodixanol from liposomes in the bloodstream is expected to be slower than other agents. Indeed, our in vitro results showed that ~15% of the originally loaded iodixanol (~8.5 mM) is retained in the liposomes after 7 days, and the in vivo results showed that the IX-lipo remained detectable in the tumor with both CT and CEST MRI at 72 hours after injection, which is consistent with previous CT studies (12,20).

While the most straightforward application of our technique is to use CT and MRI to monitor liposome-mediated drug delivery in a way similar to other diamagnetic CEST MRI contrast agents (37-39), our technology may also be useful for a broad range of biomedical applications. In this study, we demonstrated its utility for assessing the tumor response to TNF-α. Among the strategies to improve drug delivery, anti-vascular therapy has been shown effective to augment the EPR effect and increase the tumor delivery of nanoparticles (5). For example, co-injection of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α, which recently entered a phase I clinical trial (NCT01490047), can greatly augment the tumor-selective accumulation of liposomes, in some cases increasing the tumor-to-blood ratio of radiolabeled liposomes by more than 20-fold (44). Such combination therapies can benefit greatly from an imaging method that can detect the time window in which the drug delivery can be boosted to the greatest extent. Considering the pitfalls associated with the general heterogeneity of tumors, leading to different drug accumulation rates, the availability of a non-invasive CT/MRI tool that can be used repetitively to monitor the response would greatly facilitate the preclinical development and clinical implantation of vasculature-targeted therapy.

Conclusions

We have developed a CT and MRI dual-mode imaging approach for the detection of liposomes loaded with a single clinically approved X-ray/CT contrast agent, iodixanol. Both phantom and animal studies demonstrated the ability of iodixanol-loaded liposomes to generate both CT and MRI contrast, which allowed CT and MR imaging of tumor uptake and intratumoral distribution of liposomes. Additionally, we used this method to detect the enhanced tumor uptake of liposomes in mice co-injected with TNF-α, suggesting its potential usefulness as a noninvasive and imaging tool for longitudinal monitoring of an enhanced EPR effect as a result of the tumor response to anti-vascular therapies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was supported by NIH grants R21EB015609.

Ethical Statement: All animal experiments were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res 1986;46:6387-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: A review. J Control Release 2000;65:271-84. 10.1016/S0168-3659(99)00248-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv Enzyme Regul 2001;41:189-207. 10.1016/S0065-2571(00)00013-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeda H. Tumor-selective delivery of macromolecular drugs via the EPR effect: background and future prospects. Bioconjug Chem 2010;21:797-802. 10.1021/bc100070g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010;7:653-64. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2008;7:771-82. 10.1038/nrd2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, Hawkins M, O'Shaughnessy J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil–based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7794-803. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hare JI, Lammers T, Ashford MB, Puri S, Storm G, Barry ST. Challenges and strategies in anti-cancer nanomedicine development: An industry perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017;108:25-38. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trédan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1441-54. 10.1093/jnci/djm135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, Madhu B, Goldgraben MA, Caldwell ME, Allard D, Frese KK, Denicola G, Feig C, Combs C, Winter SP, Ireland-Zecchini H, Reichelt S, Howat WJ, Chang A, Dhara M, Wang L, Ruckert F, Grutzmann R, Pilarsky C, Izeradjene K, Hingorani SR, Huang P, Davies SE, Plunkett W, Egorin M, Hruban RH, Whitebread N, McGovern K, Adams J, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Griffiths J, Tuveson DA. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 2009;324:1457-61. 10.1126/science.1171362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamichhane N, Udayakumar TS, D'Souza WD, Simone CB, 2nd, Raghavan SR, Polf J, Mahmood J. Liposomes: Clinical Applications and Potential for Image-Guided Drug Delivery. Molecules 2018;23. doi: . 10.3390/molecules23020288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stapleton S, Milosevic M, Tannock IF, Allen C, Jaffray DA. The intra-tumoral relationship between microcirculation, interstitial fluid pressure and liposome accumulation. J Control Release 2015;211:163-70. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kee P, Bagalkot V, Johnson E, Danila D. Noninvasive detection of macrophages in atheroma using a radiocontrast-loaded phosphatidylserine-containing liposomal contrast agent for computed tomography. Mol Imaging Biol 2015;17:328-36. 10.1007/s11307-014-0798-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekdawi SN, Stewart JM, Dunne M, Stapleton S, Mitsakakis N, Dou YN, Jaffray DA, Allen C. Spatial and temporal mapping of heterogeneity in liposome uptake and microvascular distribution in an orthotopic tumor xenograft model. J Control Release 2015;207:101-11. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toy R, Hayden E, Camann A, Berman Z, Vicente P, Tran E, Meyers J, Pansky J, Peiris PM, Wu H, Exner A, Wilson D, Ghaghada KB, Karathanasis E. Multimodal in vivo imaging exposes the voyage of nanoparticles in tumor microcirculation. ACS Nano 2013;7:3118-29. 10.1021/nn3053439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng J, Jaffray D, Allen C. Quantitative CT imaging of the spatial and temporal distribution of liposomes in a rabbit tumor model. Mol Pharm 2009;6:571-80. 10.1021/mp800234r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao CY, Hoffman EA, Beck KC, Bellamkonda RV, Annapragada AV. Long-residence-time nano-scale liposomal iohexol for X-ray-based blood pool imaging. Acad Radiol 2003;10:475-83. 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider T, Sachse A, Rößling G, Brandl M. Generation of contrast-carrying liposomes of defined size with a new continuous high pressure extrusion method. Int J Pharm 1995;117:1-12. 10.1016/0378-5173(94)00245-Z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen PB, Larsen A, Konarboland R, Skotland T. Biotransformation of nonionic X-Ray contrast agents In vivo and In vitro. Drug Metab Dispos 1999;27:1205-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karathanasis E, Chan L, Karumbaiah L, McNeeley K, D'Orsi CJ, Annapragada AV, Sechopoulos I, Bellamkonda RV. Tumor vascular permeability to a nanoprobe correlates to tumor-specific expression levels of angiogenic markers. PLoS One 2009;4:e5843. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghaghada KB, Sato AF, Starosolski ZA, Berg J, Vail DM. Computed Tomography Imaging of Solid Tumors Using a Liposomal-Iodine Contrast Agent in Companion Dogs with Naturally Occurring Cancer. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152718. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leander P, Hoglund P, Borseth A, Kloster Y, Berg A. A new liposomal liver-specific contrast agent for CT: first human phase-I clinical trial assessing efficacy and safety. Eur Radiol 2001;11:698-704. 10.1007/s003300000712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramanathan RK, Korn RL, Raghunand N, Sachdev JC, Newbold RG, Jameson G, Fetterly GJ, Prey J, Klinz SG, Kim J, Cain J, Hendriks BS, Drummond DC, Bayever E, Fitzgerald JB. Correlation between Ferumoxytol Uptake in Tumor Lesions by MRI and Response to Nanoliposomal Irinotecan in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: A Pilot Study. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3638-48. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng J, Perkins G, Kirilova A, Allen C, Jaffray DA. Multimodal contrast agent for combined computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging applications. Invest Radiol 2006;41:339-48. 10.1097/01.rli.0000186568.50265.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou SW, Shau YH, Wu PC, Yang YS, Shieh DB, Chen CC. In vitro and in vivo studies of FePt nanoparticles for dual modal CT/MRI molecular imaging. J Am Chem Soc 2010;132:13270-8. 10.1021/ja1035013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yue L, Wang J, Dai Z, Hu Z, Chen X, Qi Y, Zheng X, Yu D. pH-Responsive, Self-Sacrificial Nanotheranostic Agent for Potential In Vivo and In Vitro Dual Modal MRI/CT Imaging, Real-Time, and In Situ Monitoring of Cancer Therapy. Bioconjug Chem 2017;28:400-9. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longo DL, Michelotti F, Consolino L, Bardini P, Digilio G, Xiao G, Sun PZ, Aime S. In Vitro and In Vivo Assessment of Nonionic Iodinated Radiographic Molecules as Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer Magnetic Resonance Imaging Tumor Perfusion Agents. Invest Radiol 2016;51:155-62. 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longo DL, Dastru W, Digilio G, Keupp J, Langereis S, Lanzardo S, Prestigio S, Steinbach O, Terreno E, Uggeri F, Aime S. Iopamidol as a responsive MRI-chemical exchange saturation transfer contrast agent for pH mapping of kidneys: In vivo studies in mice at 7 T. Magn Reson Med 2011;65:202-11. 10.1002/mrm.22608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aime S, Calabi L, Biondi L, De Miranda M, Ghelli S, Paleari L, Rebaudengo C, Terreno E. Iopamidol: Exploring the potential use of a well-established x-ray contrast agent for MRI. Magn Reson Med 2005;53:830-4. 10.1002/mrm.20441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones KM, Randtke EA, Yoshimaru ES, Howison CM, Chalasani P, Klein RR, Chambers SK, Kuo PH, Pagel MD. Clinical Translation of Tumor Acidosis Measurements with AcidoCEST MRI. Mol Imaging Biol 2017;19:617-25. 10.1007/s11307-016-1029-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon BF, Jones KM, Chen LQ, Liu P, Randtke EA, Howison CM, Pagel MD. A comparison of iopromide and iopamidol, two acidoCEST MRI contrast media that measure tumor extracellular pH. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2015;10:446-55. 10.1002/cmmi.1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goffeney N, Bulte JW, Duyn J, Bryant LH, Jr, van Zijl PC. Sensitive NMR detection of cationic-polymer-based gene delivery systems using saturation transfer via proton exchange. J Am Chem Soc 2001;123:8628-9. 10.1021/ja0158455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson 2000;143:79-87. 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G, Song X, Chan KW, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed 2013;26:810-28. 10.1002/nbm.2899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longo DL, Bartoli A, Consolino L, Bardini P, Arena F, Schwaiger M, Aime S. In Vivo Imaging of Tumor Metabolism and Acidosis by Combining PET and MRI-CEST pH Imaging. Cancer Res 2016;76:6463-70. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Jablonska A, Li Y, Cao S, Liu D, Chen H, Van Zijl PC, Bulte JW, Janowski M, Walczak P, Liu G. Label-free CEST MRI Detection of Citicoline-Liposome Drug Delivery in Ischemic Stroke. Theranostics 2016;6:1588-600. 10.7150/thno.15492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Chen H, Xu J, Yadav NN, Chan KW, Luo L, McMahon MT, Vogelstein B, van Zijl PC, Zhou S, Liu G. CEST theranostics: label-free MR imaging of anticancer drugs. Oncotarget 2016;7:6369-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan KW, Yu T, Qiao Y, Liu Q, Yang M, Patel H, Liu G, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC, Hanes J, Zhou S, McMahon MT. A diaCEST MRI approach for monitoring liposomal accumulation in tumors. J Control Release 2014;180:51-9. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu G, Moake M, Har-el YE, Long CM, Chan KW, Cardona A, Jamil M, Walczak P, Gilad AA, Sgouros G, van Zijl PC, Bulte JW, McMahon MT. In vivo multicolor molecular MR imaging using diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer liposomes. Magn Reson Med 2012;67:1106-13. 10.1002/mrm.23100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart JC. Colorimetric determination of phospholipids with ammonium ferrothiocyanate. Analytical Biochemistry 1980;104:10-4. 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90269-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu G, Gilad AA, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC, McMahon MT. High-throughput screening of chemical exchange saturation transfer MR contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2010;5:162-70. 10.1002/cmmi.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med 2009;61:1441-50. 10.1002/mrm.21873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stapleton S, Allen C, Pintilie M, Jaffray DA. Tumor perfusion imaging predicts the intra-tumoral accumulation of liposomes. J Control Release 2013;172:351-7. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.08.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiao Y, Huang X, Nimmagadda S, Bai R, Staedtke V, Foss CA, Cheong I, Holdhoff M, Kato Y, Pomper MG, Riggins GJ, Kinzler KW, Diaz LA, Jr, Vogelstein B, Zhou S. A robust approach to enhance tumor-selective accumulation of nanoparticles. Oncotarget 2011;2:59-68. 10.18632/oncotarget.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spencer CM, Goa KL. Iodixanol. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and diagnostic use as an x-ray contrast medium. Drugs 1996;52:899-927. 10.2165/00003495-199652060-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhavane R, Badea C, Ghaghada KB, Clark D, Vela D, Moturu A, Annapragada A, Johnson GA, Willerson JT, Annapragada A. Dual-Energy Computed Tomography Imaging of Atherosclerotic Plaques in a Mouse Model Using a Liposomal-Iodine Nanoparticle Contrast Agent. Circulation-Cardiovascular Imaging 2013;6:285-94. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longo DL, Sun PZ, Consolino L, Michelotti FC, Uggeri F, Aime S. A general MRI-CEST ratiometric approach for pH imaging: demonstration of in vivo pH mapping with iobitridol. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136:14333-6. 10.1021/ja5059313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen LQ, Howison CM, Jeffery JJ, Robey IF, Kuo PH, Pagel MD. Evaluations of extracellular pH within in vivo tumors using acidoCEST MRI. Magn Reson Med 2014;72:1408-17. 10.1002/mrm.25053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Müller-Lutz A, Khalil N, Schmitt B, Jellus V, Pentang G, Oeltzschner G, Antoch G, Lanzman RS, Wittsack HJ. Pilot study of Iopamidol-based quantitative pH imaging on a clinical 3T MR scanner. MAGMA 2014;27:477-85. 10.1007/s10334-014-0433-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones KM, Pollard AC, Pagel MD. Clinical applications of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;47:11-27. 10.1002/jmri.25838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anemone A, Consolino L, Longo DL. MRI-CEST assessment of tumour perfusion using X-ray iodinated agents: comparison with a conventional Gd-based agent. Eur Radiol 2017;27:2170-9. 10.1007/s00330-016-4552-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Longo DL, Busato A, Lanzardo S, Antico F, Aime S. Imaging the pH evolution of an acute kidney injury model by means of iopamidol, a MRI-CEST pH-responsive contrast agent. Magn Reson Med 2013;70:859-64. 10.1002/mrm.24513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Havron A, Seltzer SE, Davis MA, Shulkin P. Radiopaque liposomes: a promising new contrast material for computed tomography of the spleen. Radiology 1981;140:507-11. 10.1148/radiology.140.2.7255729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sachse A, Leike JU, Schneider T, Wagner SE, Rossling GL, Krause W, Brandl M. Biodistribution and computed tomography blood-pool imaging properties of polyethylene glycol-coated iopromide-carrying liposomes. Invest Radiol 1997;32:44-50. 10.1097/00004424-199701000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spinazzi A, Ceriati S, Pianezzola P, Lorusso V, Luzzani F, Fouillet X, Alvino S, Rummeny EJ. Safety and pharmacokinetics of a new liposomal liver-specific contrast agent for CT: results of clinical testing in nonpatient volunteers. Invest Radiol 2000;35:1-7. 10.1097/00004424-200001000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allen C, Dos Santos N, Gallagher R, Chiu GNC, Shu Y, Li WM, Johnstone SA, Janoff AS, Mayer LD, Webb MS, Bally MB. Controlling the physical behavior and biological performance of liposome formulations through use of surface grafted poly(ethylene glycol). Biosci Rep 2002;22:225-50. 10.1023/A:1020186505848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Allen TM, Hansen C. Pharmacokinetics of stealth versus conventional liposomes: effect of dose. Biochim Biophys Acta 1991;1068:133-41. 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90201-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013;65:36-48. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]