Abstract

Background:

Tobacco spending may exacerbate financial hardship in low-income populations by using funds that could go toward essentials. This study examined post-quit spending plans among low-income smokers and whether financial hardship was positively associated with motivation to quit in the sample.

Methods:

We analyzed data from the baseline survey of a randomized controlled trial testing novel a smoking cessation intervention for low-income smokers in New York City (N = 410). Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between financial distress, food insecurity, smoking-induced deprivation (SID) and motivation to quit (measured on a 0-10 scale). We performed summative content analyses of open-ended survey questions to identify the most common plans among participants with and without SID for how to use their tobacco money after quitting.

Results:

Participants had an average level of motivation to quit of 7.7 (SD = 2.5). Motivation to quit was not significantly related to having high financial distress or food insecurity (P > .05), but participants reporting SID had significantly lower levels of motivation to quit than those without SID (M = 7.4 versus 7.9, P = .04). Overall, participants expressed an interest in three main types of spending for after they quit: Purchases, Activities, and Savings/Investing, which could be further conceptualized as spending on Oneself or Family, and on Needs or Rewards. The top three spending plans among participants with and without SID were travel, clothing and savings. There were three needs-based spending plans unique to a small number of participants with SID: housing, health care and education.

Conclusions:

Financial distress and food insecurity did not enhance overall motivation to quit, while smokers with SID were less motivated to quit. Most low-income smokers, including those with SID, did not plan to use their tobacco money on household essentials after quitting.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking cessation, food insecurity, financial hardship

Introduction

Cigarette smoking remains the largest cause of preventable mortality in the U.S., and members of low-income households are twice as likely to smoke as high-income households—leading to direct health harms and disproportionate rates of tobacco-related illness (e.g., cancer, heart disease) and mortality in low-income populations.1 Smoking may further indirectly harm health and exacerbate financial hardship in low-income smokers through a financial mechanism, whereby tobacco spending crowds-out spending on health-promoting essentials. Tobacco expenditures have been associated with reduced spending on housing, food and clothing,2 and food insecurity (lack of consistent access to food due to financial constraints) is more common and more severe among households with adults who smoke.3

Given the immediate potential financial consequences of tobacco spending for low-income smokers, smokers experiencing financial hardship may be especially motived to quit or may be especially sensitive to the financial losses of smoking and gains of cessation. However, the relationship between financial hardship and motivation to quit remains mixed in the literature. Some studies have seen no significant associations between financial distress and motivation to quit or other indicators of motivation such as quit attempts.4,5 On the other hand, some research has reported higher motivation in people with higher financial distress through both direct measures of motivation and indirect measures such as use of quitlines and quit attempts.6-9 For example, Wilson et al found that in New Zealand, national quitline usage was higher among people with financial stress.10 Caleyachetty et al however, saw the opposite relationship, noting fewer quit attempts from smokers with financial difficulty.11

The inconsistent literature on the relationship between financial hardship and motivation to quit may be explained by the complex nature of the relationship. While financial insecurity can increase one’s desire to quit for financial reasons, financial stress is a commonly cited barrier to quitting and a contributor to smoking maintenance.8,9,12-14 Smokers often use cigarettes as a coping mechanism for stress, and as Siahpush et al. points out, the relationship between smoking and financial stress is likely bidirectional.12 Another potential explanation for the inconsistent relationship between financial hardship and motivation to quit is that some smokers may not perceive the financial consequences of tobacco use or attribute their financial distress to tobacco spending. Public health campaigns and quit messaging within health care often focus on the health consequences of tobacco use. Therefore, even when experiencing financial distress, some smokers may not attribute financial hardship to their tobacco use or view cessation as a potential solution to their distress—thus breaking a potential link between financial hardship and motivation to quit. Lastly, the relationship between financial hardship and motivation to quit may be heterogeneous even within low-income populations depending on the nature or severity of one’s hardship. For example, people experiencing moderate food insecurity or difficulties paying small bills may benefit from the discretionary income released through the cessation of tobacco spending, but tobacco cessation would offer limited help for people experiencing large sources of financial distress such as threats of eviction or large medical expenses. Indeed, estimates suggest that only 10-30% of low-income smokers report experiencing a phenomenon called smoking-induced deprivation (SID), defined as the inability to afford household or personal essentials because of money spent on tobacco. Therefore, motivation to quit may be increased only among people experiencing tobacco-related financial hardship, such as SID.

Gaining a better understanding of how financial hardship and motivation to quit relate to one another can aid in the development of cessation policies and programs for smokers living in poverty. Tucker-Seeley and Thorpe recently proposed a model of financial hardship that distinguishes between material, psychosocial, and behavioral components of financial hardship.11 The material component refers to one’s actual financial resources. The psychosocial component refers to how one feels about his or her resources. The behavioral component refers to what one does with his or her limited resources, such as purposeful economizing or reducing spending on essentials. The present study aimed to examine the relationships between different types of financial hardship (material, psychosocial, behavioral) and motivation to quit among a sample of low-income smokers living in New York City (a city with a high cost of living and the highest cigarette taxes in the U.S.). The study further aimed to explore post-quit spending goals among low-income smokers with and without tobacco-related behavioral financial hardship (SID). We hypothesized that all three types of financial hardship would be positively associated with motivation to quit and that smokers with SID would be more likely to plan to spend their tobacco money on household essentials after quitting.

Methods

Source of data and study design

The data for this analysis came from the baseline survey of a two-arm randomized controlled trial testing an intervention that integrated financial coaching into smoking cessation coaching for low-income smokers (versus a waitlisted control arm receiving usual smoking cessation care during the waiting period). The parent study was approved by the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Study population and recruitment

People were eligible for the parent study if they: (1) were aged ⩾18 years, (2) had smoked a cigarette in the past 30 days, “even a puff”, (3) had self-reported income <200% of the current federal poverty level, (4) New York City resident, (5) spoke English or Spanish, (6) were able to provide informed consent, and (7) did not have a representative who managed his/her funds. Individuals were excluded if they reported being pregnant or breastfeeding due to their inability to receive nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) during the parent study.

Participants were recruited from Bellevue Hospital Center and NYU Langone-Brooklyn in New York City. Study staff identified potential participants through an electronic medical record (EMR) query of patients screened to be recent smokers by a physician or nurse at each site. Staff called potential participants on the EMR list to describe the study, screen them for eligibility and schedule an in-person consent appointment. Participants were also recruited through weekly community-based newspaper ads, physician referrals and incentivized referrals from other study participants. All participants signed an IRB-approved consent form prior to completing any study procedures.

Interventions

Participants (N = 410) were randomized 1:1, stratified by site, to an Intervention Group or a Waitlist Control Group. The Intervention Group participants immediately began a 9-week, multisession intervention that integrated financial coaching and smoking cessation coaching. The integrated intervention was designed to reduce participants’ financial stress as a barrier to cessation and to help them transition from spending money on cigarettes to spending on health-promoting essentials. Intervention coaches screened for, and referred participants to, financial benefits programs, and helped participants develop a household budget that highlighted funds spent on tobacco and helped participants identify short-term and long-term financial goals that could be achieved through cessation of tobacco spending. The intervention also provided four weeks of NRT (patch, gum or lozenge). The Waitlist Control Group participants were eligible to receive the intervention after a waiting period of 6 months. During the 6-month waiting period, they could receive usual cessation care from their health care providers or try to quit on their own using over-the-counter cessation medications or community resources (e.g., state quitline).

Baseline data collection and measures

Participants completed an in-person baseline survey after enrollment and before randomization that assessed the following measures:

Sociodemographics: Participants reported their date of birth, race, ethnicity, marital status, annual household income, and highest level of education.

Tobacco use and tobacco spending: The survey assessed time to first cigarette after waking, which has been reported in the literature to be a predictive and valid single-item measure of nicotine dependence.15 The survey used questions from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study’s adult questionnaire to assess motivation to quit using a 0-10 scale and number of cigarettes smoked per day.16 Participants were also asked to report the amount they typically spend on a pack of cigarettes or per cigarette if they typically purchase loosie cigarettes. For each participant, a monthly pack variable was calculated by multiplying their cigarettes per day by 30 and dividing by 20 (the typical number of cigarettes per pack). This monthly pack variable was then multiplied by cigarette price to obtain an estimate of the participants’ monthly spending on cigarettes.

Financial hardship: The survey assessed three types of financial hardship: (1) psychosocial hardship which we operationalized as financial distress, (2) material hardship which we operationalized as food insecurity (i.e., lack of sufficient financial resources for food), and (3) behavioral hardship which we operationalized as SID. Four domains of financial distress were assessed using questions from the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-being Scale.17 These were: (1) level of personal stress in general, (2) frequency of living paycheck-to-paycheck, (3) frequency of worrying about making monthly living expenses, and (4) level of confidence in being able to afford a $1 000 emergency. Participants answered each question on a 0-10 scale, where 0 represented the lowest level of stress and 10 represented the highest level of stress. For this analysis, responses were then dichotomized as High (answer ⩾6) or Low (answer <6).

Food insecurity was assessed using the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) six-item food security module.8 The sum of affirmative responses to the six questions were converted to the following scoring criteria: 0-1 affirmatives indicated high or marginal food security, a score of 2-4 indicated low food security and 5-6 indicated very low food security. For the purpose of this analysis, low and very low food security were collapsed into one variable “food insecure.”

SID was assessed with a single Yes/No question adapted from the literature18 asking: “In the last 30 days, has there been a time when the money you spent on cigarettes resulted in not having enough money for any of these items: housing, food, household utilities, health care, transportation, and necessary clothing?”

Post-quit spending plans

Using an open-ended question, participants were asked to name their top goals for how they would like to use their tobacco money after quitting. Participants were encouraged, but not required, to provide up to three goals.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS software, version 23. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and frequencies were conducted for sociodemographic and tobacco use variables to characterize the study sample and to determine the prevalence of high financial distress, food insecurity, and SID in the sample. Linear regression models were used to determine the associations between participants’ financial hardship measures and motivation to quit, controlling for sociodemographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, education). Significance was defined as a P-value <0.05.

We used a summative content analysis approach19 to analyze post-quit spending plan data. We first ran frequencies of participant responses to the open-ended question about post-quit spending goals to identify patterns and themes in responses. We then created and recoded the data into higher-level spending categories based on the answer patterns. For example, when participants said they wanted to spend their tobacco money on vacations, visiting family, cruises or other forms of traveling, these answers were recoded into a new broad “travel” category. Once the data were recoded into broad categories, we ranked the data based on frequency of participants endorsing each goal. To explore differences in goals between participants with and without SID, we stratified the ranking by presence (Yes/No) of SID.

Results

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the study sample. Participants were on average 53.3 years old (SD = 11.2) and were predominantly male, Black or African American, non-Hispanic, unmarried, and unemployed. Participants were smoking on average 12 cigarettes per day. Recent SID was reported by 47% of participants, 57% were food insecure and 64% had high stress about their personal finances. Participants reported an average annual income of $13 680 (SD = $10 069) per year and were spending approximately $182.4 (SD = $121.8) per month on cigarettes.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 410).

| Variable | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age | 53.3 (11.2) |

| Female gender | 144 (35%) |

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 187 (46%) |

| White | 81 (20%) |

| Other | 142 (35%) |

| Hispanic | 161 (39%) |

| Immigrant | 149 (36%) |

| Spanish language preferred | 64 (16%) |

| Highest level of education completed | |

| Less than high school | 106 (26%) |

| High school/GED | 137 (33%) |

| Associates Degree or some 4-year college | 119 (29%) |

| 4-year college graduate or higher | 44 (11%) |

| Other (e.g., trade school) | 4 (1%) |

| Employed | 103 (25%) |

| Married or living with partner | 74 (18%) |

| Annual income | $13 680 (10 069) |

| Tobacco use and quit attitudes | |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 11.7 (7.2) |

| Time to first cigarette | |

| <5 minutes | 146 (36%) |

| 6-30 minutes | 123 (30%) |

| 30-60 minutes | 50 (12%) |

| >60 minutes | 90 (22%) |

| Typical price paid for pack of cigarettes | $10.6 (3.7) |

| Monthly tobacco spending | $182.4 (121.8) |

| Motivation to quit | 7.7 (2.5) |

| Confidence in quitting | 7.1 (5.4) |

| Financial hardship | |

| Behavioral: smoking-induced deprivation | 194 (47%) |

| Material: food insecure | 234 (57%) |

| Psychosocial | |

| Low financial satisfaction | 315 (77%) |

| High level of worry about monthly expenses | 285 (70%) |

| Low confidence in paying for $1 000 emergency | 286 (70%) |

| Frequently having difficulty affording leisure activity | 287 (70%) |

| Frequently living paycheck-to-paycheck | 345 (84%) |

| High financial stress in general | 262 (64%) |

Table 2 shows the relationship between participants’ financial hardship measures and motivation to quit, controlling for sociodemographics. Motivation to quit was not significantly related to participants’ financial stress in general, frequency of living paycheck-to-paycheck, frequency of worry about monthly living expenses, or confidence in affording a financial emergency (P > .05). Participants reporting SID had significantly lower levels of motivation to quit than those without SID (M = 7.4 versus 7.9; β = −0.39, SE = 0.20, P = 0.04).

Table 2.

Relationships between participant financial hardship measures and motivation to quit (N = 410).

| Variable | β (SE) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral: past 30-day smoking-induced deprivation | –0.39 (0.20) | 0.04 |

| Material: past-year food insecurity | –0.16 (0.28) | 0.56 |

| Psychosocial | ||

| High financial stress in general | 0.20 (0.28) | 0.48 |

| Frequently living paycheck-to-paycheck | 0.08 (0.36) | 0.81 |

| Low confidence to afford $1 000 emergency | 0.30 (0.29) | 0.31 |

| Frequently worry about monthly living expenses | 0.25 (0.30) | 0.41 |

Notes: Analysis control for participant income, gender, race, ethnicity, and education. Motivation to quit was measured on a 0-10 scale.

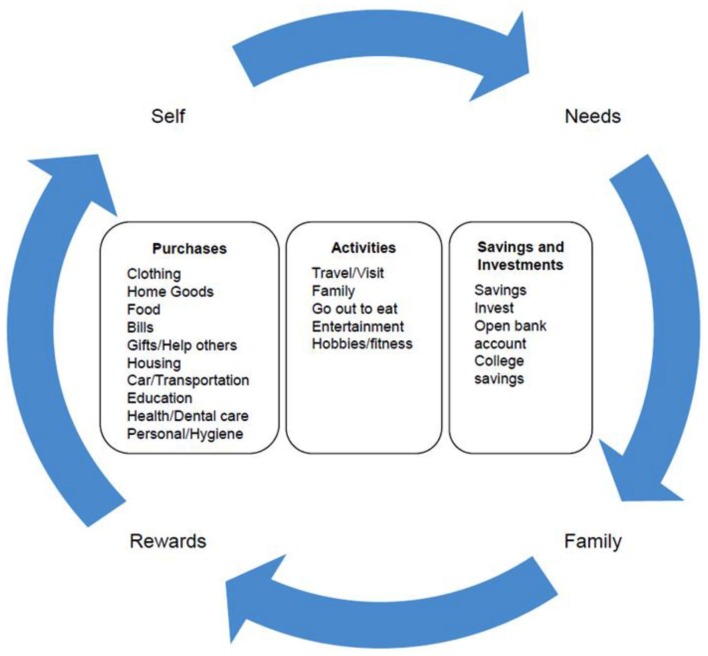

Figure 1 shows the themes in post-quit spending plans reported by participants at baseline. Participants expressed an interest in three main types of spending. The first type was Purchases. Purchases included items such as clothing, home goods (e.g., furniture, television), transportation costs, paying bills, buying gifts for loved ones or helping loved ones pay for their expenses, education-related purchases, visiting the doctor or getting dental work, and buying personal hygiene products. The second spending type was Activities, such as traveling, socializing, going out to eat, engaging in entertainment (e.g., movies, concerts), and engaging in hobbies or exercise-related activities. The final main spending type was Investments and Savings. Participants spoke of wanting to invest the money, either through the stock market or by investing in their personal business. Participants also spoke about wanting to save their tobacco money, open a bank account, or save for their children’s or grandchildren’s college expenses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of post-quit spending goals reported by participants.

Our summative content analysis of the post-quit spending question also revealed that participants’ spending goals could be further conceptualized based on the spending recipient (Family and/or Oneself) and whether the spending was addressing a Need or was serving as a luxury or Reward. For example, within the Family–Self dichotomy, many of the activities that participants planned after quitting were associated with wanting to visit or spend more time with family, and some participants intended to purchase items for their grandchildren or children. On the other hand, many participants intended to spend the money on items for themselves. Within the Need–Reward dichotomy, some participants reported wanting to spend their tobacco money on household or personal essentials, such as food, health care or dental work, while other spending plans were not essential, such as general shopping, redecorating the house, traveling or going to the movies.

Table 3 displays the ranking of the top 10 most frequently reported post-quit goals among participants with and without SID. Overall, participants in both groups reported similar goals. The three most common goals in both groups were travel, clothing and savings. However, the relative ranking of the goals differed somewhat between groups. Purchasing clothing was the top goal for participants with SID, while travel was the top goal for participants without SID. Paying bills, purchasing food, engaging in entertainment and purchasing home goods ranked somewhat higher among participants with SID, while going to restaurants and buying gifts ranked slightly higher among people without SID. There were three needs-based goals unique to participants with SID. Eleven percent of participants with SID planned to spend their tobacco savings on housing (e.g., paying rent), and 4% of participants with SID planned to spend their tobacco money on health care or education.

Table 3.

A ranking by frequency of post-quit spending goals reported at baseline by participants with and without recent SID.

| Rank | Participants with SID, N = 194 |

Participants without SID, N = 216 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending category | n | % | Spending category | n | % | |

| 1 | Clothing | 93 | 47% | Travel | 90 | 41% |

| 2 | Travel | 85 | 43% | Clothing | 81 | 37% |

| 3 | Savings | 48 | 24% | Savings | 62 | 29% |

| 4 | Entertainment, food, home goodsa | 33 | 17% | Restaurants | 35 | 16% |

| 5 | Bills | 24 | 12% | Home goods | 31 | 14% |

| 6 | Restaurants | 23 | 12% | Food | 25 | 12% |

| 7 | Housing | 21 | 11% | Entertainment | 24 | 11% |

| 8 | Car | 17 | 9% | Gifts/help others | 23 | 11% |

| 9 | Gifts/help others | 11 | 6% | Bills | 16 | 7% |

| 10 | Education, health careb | 8 | 4% | Car | 15 | 7% |

Notes: SID (smoking-induced deprivation) was measured with the question “In the last 30 days, has there been a time when the money you spent on cigarettes resulted in not having enough money for any of these items: housing, food, household utilities, health care, transportation, personal hygiene items, or necessary clothing?”

Entertainment, food and home goods tied for fourth place among participants with SID (each were reported by 33 participants).

Education and health care tied for 10th place among people with SID (each were reported by eight participants).

Discussion

This study found high levels of material, psychosocial and behavioral financial hardship in a sample of low-income smokers enrolled in a smoking cessation study. Most participants were food insecure, almost half reported recent SID, and most were experiencing a high level of distress in the four financial stress domains surveyed (financial distress in general, living paycheck-to-paycheck, worrying about monthly living expenses, and confidence in affording a financial emergency). Results also estimated that participants were spending on average $182 per month on tobacco (16% of their annual income), which is a relatively large source of discretionary income that could be used to alleviate the household needs identified through the financial hardship measures. However, contrary to our hypotheses, there were no significant relationships found between participants’ level of motivation to quit and most measures of financial hardship. These results are consistent with prior studies finding no significant relationships between financial stress and motivations to quit in low-income populations.4,5 The only measure that was significantly associated with motivation to quit was the tobacco-related behavioral financial hardship measure (SID). However, unexpectedly, smokers with recent SID had lower motivation to quit than those without recent SID. This is the first study to our knowledge to show lower motivation to quit among people experiencing SID.

This is also the first study to our knowledge to examine post-quit spending plans among low-income smokers getting ready to engage in a smoking cessation attempt, and the results of this examination provides insights into the findings above. Results showed that prior to starting the study intervention, participants had a variety of plans for how to use their tobacco money after quitting, with goals ranging from spending on themselves to spending on others, across three main spending categories (purchase, activities, and savings/investing) representing a mix of needs and luxuries or rewards. Results further found that most participants did not plan to spend their tobacco money on needs after quitting, even participants who reported recently going without needs because of money spent on cigarettes (SID). While there were three unique needs-based spending plans found among participants with SID, the proportion of participants with those plans was <10%. These results suggest that most participants did not view—or plan to use—tobacco cessation as a means to address their financial needs or hardship. Additional work is needed to understand this finding, but it may explain why severity of financial hardship was not related to motivation to quit in our quantitative analyses.

Prior work has shown that people who smoke are motivated to quit for many nonfinancial reasons (social, health, occupational), and low-income populations often use smoking as a means to cope with stress.10 Additionally, psychosocial and behavioral financial hardship have been shown to be associated with barriers to quitting not measured in this study, including depression.20,21 It is possible that people with high levels of psychosocial, material or behavioral hardship in this study were experiencing barriers to quitting that overwhelmed any finance-related motivations to quit or they were using of cigarettes to cope with psychosocial stressors. This may explain both the lack of relationships between most of the study’s financial hardship measures and motivation to quit, as well as explain participants’ plans to spend their tobacco money on mood-enhancing items or activities after quitting in order to replace tobacco as a stress reducer.21

Limitations

This study is limited by its analysis of participants enrolled in a smoking cessation study that offered assistance with financial stress. Participants had high levels of motivation to quit overall and their smoking-related motivations may not generalize to a broader low-income population. The study was also located in New York City, a city with high tobacco prices and high cost of living in general. Therefore, results may not generalize to other settings. Another limitation is that the measure of monthly tobacco spending was based on self-reported typical spending on cigarette packs or loosies, which we then extrapolated to a monthly spending variable. To our knowledge, there are no psychometrically tested measures of retrospective tobacco spending. The data analyzed for this manuscript were collected at baseline, so it would not have been feasible to ask participants to prospectively track actual spending for a month prior to entering the study. Therefore, the tobacco spending estimate may be subject to recall bias and should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

This study conducted a unique examination into the motivations and goals of low-income smokers experiencing three forms of financial hardship. The overall pattern results suggest that while low-income smokers experience high levels of financial hardship in multiple domains of their lives and have a source of discretionary income (tobacco spending) to help, severity of financial hardship was not associated with quitting motivation and most smokers did not plan to use their tobacco money to alleviate hardship after quitting. Cessation programs working with low-income smokers may not benefit from stressing the financial benefits of quitting or such programs may need to put targeted efforts into increasing smoker insight into the opportunity costs of their tobacco use. Future research should also determine the best methods for addressing the psychosocial barriers to cessation in this vulnerable population.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Robin Hood Foundation.

Declaration of conflicting interest:The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions: ER and SS were the Principal Investigators on the project. ESR conceived of the current sub-analysis, led the data analysis, and led the writing of the manuscript. MR, KK and BDE were Co-Investigators on the project. JP, EV and CW assisted the study in data collection, literature review, and co-writing of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Erin Rogers  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3207-7956

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3207-7956

References

- 1. Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafo M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Busch SH, Jofre-Bonet M, Falba TA, Sindelar JL. Burning a hole in the budget: tobacco spending and its crowd-out of other goods. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2004;3(4):263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cutler-Triggs C, Fryer GE, Miyoshi TJ, Weitzman M. Increased rates and severity of child and adult food insecurity in households with adult smokers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(11):1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martire KA, Clare P, Courtney RJ, et al. Smoking and finances: baseline characteristics of low income daily smokers in the FISCALS cohort. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tucker-Seeley RD, Selk S, Adams I, Allen JD, Sorensen G. Tobacco use among low-income housing residents: does hardship motivate quit attempts? Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(11):1699–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilson N, Weerasekera D, Borland R, Edwards R, Bullen C, Li J. Use of a national quitline and variation in use by smoker characteristics: ITC Project New Zealand. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl):S78–S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalkhoran S, Berkowitz SA, Rigotti NA, Baggett TP. Financial strain, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among U.S. adult smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(1):80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caleyachetty A, Lewis S, McNeill A, Leonardi-Bee J. Struggling to make ends meet: exploring pathways to understand why smokers in financial difficulties are less likely to quit successfully. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(suppl 1):41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kotz D, West R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: it’s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob Control. 2009;18(1):43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villanti AC, Bover Manderski MT, Gundersen DA, Steinberg MB, Delnevo CD. Reasons to quit and barriers to quitting smoking in US young adults. Fam Pract. 2016;33(2):133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tucker-Seeley RD, Thorpe RJ., Jr Material–psychosocial–behavioral aspects of financial hardship: a conceptual model for cancer prevention. Gerontologist. 2019;59(suppl_1):S88–S93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siahpush M, Yong HH, Borland R, Reid JL, Hammond D. Smokers with financial stress are more likely to want to quit but less likely to try or succeed: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1382–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Siahpush M, Tibbits M, Soliman GA, et al. Neighbourhood exposure to point-of-sale price promotions for cigarettes is associated with financial stress among smokers: results from a population-based study. Tob Control. 2017;26(6):703–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheffer CE, Brackman SL, Cottoms N, Olsen M. Understanding the barriers to use of free, proactive telephone counseling for tobacco dependence. Qual Health Res. 2011;21(8):1075–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(suppl 4):S555–S570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. United States Department of Health Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Food Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files. In: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, O’Neill B, Kim J, Drentea P. In charge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J. Financial Couns. Plan. 2006;17(1):34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siahpush M, Borland R, Yong HH. Sociodemographic and psychosocial correlates of smoking-induced deprivation and its effect on quitting: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Tob Control. 2007;16(2):e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rogers ES. Financial distress and smoking-induced deprivation in smokers with depression. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robles Z, Anjum S, Garey L, et al. Financial strain and cognitive-based smoking processes: the explanatory role of depressive symptoms among adult daily smokers. Addict Behav. 2017;70:18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]