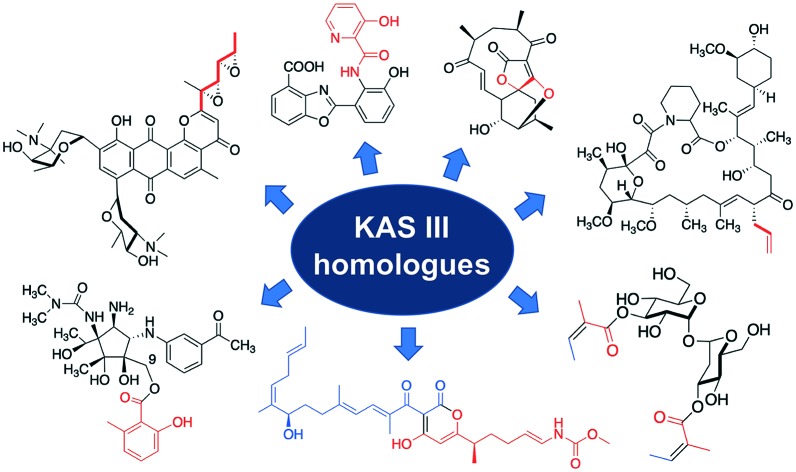

KAS III-like enzymes play a significant role in natural product biosynthesis through C–C, C–O, and/or C–N bond formation.

KAS III-like enzymes play a significant role in natural product biosynthesis through C–C, C–O, and/or C–N bond formation.

Abstract

The 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS) III proteins are one of the most abundant enzymes in nature, as they are involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acids and natural products. KAS III enzymes catalyse a carbon–carbon bond formation reaction that involves the α-carbon of a thioester and the carbonyl carbon of another thioester. In addition to the typical KAS III enzymes involved in fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis, there are proteins homologous to KAS III enzymes that catalyse reactions that are different from that of the traditional KAS III enzymes. Those include enzymes that are responsible for a head-to-head condensation reaction, the formation of acetoacetyl-CoA in mevalonate biosynthesis, tailoring processes via C–O bond formation or esterification, as well as amide formation. This review article highlights the diverse reactions catalysed by this class of enzymes and their role in natural product biosynthesis.

Introduction

Among the myriad of biosynthetic enzymes are a group of proteins known as the thiolase/ketosynthase superfamily.1,2 They catalyse the Claisen condensation reaction, a carbon–carbon bond formation reaction that involves the α-carbon of a thioester and the carbonyl carbon of another thioester. This reaction is utilized during the biosynthesis of both primary (fatty acids) and secondary metabolites (fatty acids, polyketides and isoprenoids).3 Members of the thiolase/ketosynthase superfamily are also involved in the degradation of fatty acids.4 Given the key role fatty acids play in an organism's life cycle, and that they are key components of cell walls, membranes, and lipoproteins, the importance of the thiolase/ketosynthase superfamily cannot be understated.5

Fatty acids are biosynthesized by fatty acid synthases (FAS), which are segregated into two types based on their protein architectures. Type I FAS (FAS I) enzymes consist of a multidomain, multifunctional protein encoded by a gene and commonly found in mammals, fungi and corynebacteria.3 Type II FAS (FAS II) enzymes form protein complexes derived from multiple monofunctional proteins, each of which is encoded by a separate gene;6 they are found in bacteria, plants, parasites and eukaryotic mitochondria.6,7 Some microbes, such as mycobacteria, have both FAS I and FAS II enzymes.3 While FAS I usually produces palmitate as the final product, FAS II can produce a variety of products including fatty acids of differing chain lengths, unsaturated fatty acids, iso- and anteiso-branched-chain fatty acids and hydroxy fatty acids.6

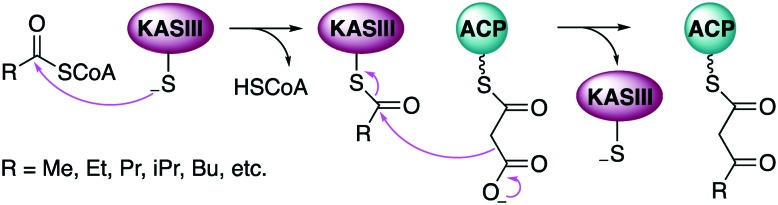

Both FAS I and FAS II require a post-translational modification to become active, which consists of the attachment of a 4′-phosphopantetheinyl (4′-PP) arm (derived from coenzyme A (CoA)) to a conserved serine residue of the acyl carrier protein (ACP). This 4′-PP arm provides a thiol to tether both substrates and the growing product through a thioester. In the FAS I system, the thio-Claisen reaction is initiated by transfer of the acetyl group from acetyl-CoA onto the 4′-PP arm of the initial ACP by the malonyl/acetyl transferase (MAT) domain.8 The acetyl-ACP is then condensed with malonyl-ACP by a ketosynthase (KS) domain to obtain acetoacetyl-ACP. This coupling is driven by the decarboxylation of malonyl-ACP to form the nucleophilic enolate anion. Following the thio-Claisen condensation reaction, the resulting β-keto-thioester is reduced by a ketoreductase (KR) domain, dehydrated by a dehydratase (DH) domain, and subsequently reduced by an enoylreductase (ER) domain to produce a fully saturated acyl-ACP. This cycle is repeated until the fatty acid reaches the desired chain length. Finally, the product is released via hydrolysis from the ACP by a thioesterase (TE) domain. Typically, in FAS II, the fatty acid biosynthetic cycle is initiated by the transfer of an acetyl group (called a primer) from acetyl-CoA to a conserved cysteine residue of a 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (KAS III) protein, and subsequently condensed with malonyl-ACP (Fig. 1). The resulting acetoacetyl-ACP undergoes elongation through the action of two enzymes, KAS I and KAS II, both of which catalyse a condensation between an acyl-ACP and malonyl-ACP. In Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Synechocystis, both KAS I and KAS II are similar in their condensation mechanism; however, their substrates can differ.6,9 In E. coli KAS I extends C4 fatty acids to produce the C16 acyl chain while KAS II elongates C16 fatty acids to the C18 acyl chain.10

Fig. 1. Catalytic function of KAS III enzymes in fatty acid biosynthesis.

In general, FAS enzymes produce three types of fatty acids: straight-chain fatty acid (SCFA), branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA), and complex fatty acids (CFA).11 The type of fatty acids produced by FAS enzymes depend on the starter units used and the proteins that are involved in the initiation step. In FAS II systems, KAS III enzymes play a significant role in product variation. Acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and butyryl-CoA are normally used as starter units for SCFA biosynthesis while isopropyl-CoA, isobutyryl-CoA and methylbutyryl-CoA are used for BCFA biosynthesis (Fig. 1).12,13 The ratio of SCFA, BCFA, and CFA biosynthesis in microbes appears to depend on the availability of substrates. For example, high concentration of 3-methylbutyryl-CoA in Streptomyces glaucescens increases the production of the BCFA isopentadecanoate,14 and S. glaucescens grown in media supplemented with leucine produced more 3-methylbutyryl-CoA. In addition, binding competition between substrates at the enzyme active sites can also affect fatty acid profiles.

Many KAS III proteins are able to accept more than one substrate, resulting in diverse fatty acid products. Staphylococcus aureus KAS III (SaFabH) is able to use a variety of short-chain acyl-CoAs, e.g., acetyl and propionyl-CoA, as starter units.15Cuphea wrightii KAS III (CwFabH) accepts acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA and butyryl-CoA as starter units.16 In addition, CwFabH is able to use acetyl and butyryl-ACP as starter units, albeit with low efficiency.16Streptococcus pneumoniae KAS III (SpFabH) preferentially accepts acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA as substrates.17S. glaucescens KAS III (SgFabH) uses various starter units such as isobutyryl, isovaleryl, and anteisovaleryl-CoA, in addition to acetyl and butyryl-CoA.14Mycobacterium tuberculosis KAS III (MtFabH) most readily accepts long-chain acyl-CoAs, particularly lauryl-CoA (C12), compared with short-chain acyl-CoAs.18 In addition to using acyl-CoAs, MtFabH can also recognise acyl-ACPs as substrates with reduced efficiency, similar to CwFabH.

While many bacteria, such as E. coli and S. aureus, only contain a single FabH, some bacteria encode two FabH proteins. For example, Bacillus subtilis encodes two homologous KAS III proteins, BsFabH1 and BsFabH2. Both of them perform the initial condensation reaction of fatty acid biosynthesis using acetyl-CoA as a primer, as well as branched-chain acyl-CoAs.19 The BsFabH2 enzyme has a slight preference for iso-substrates (e.g., isobutyryl- and isovaleryl-CoA), whereas BsFabH1 prefers anteiso-substrates (e.g., 2-methylbutyryl-CoA) as starter units. Vibrio cholerae also encodes two orthologues of FabH, namely VcFabH1 and VcFabH2, which are located on chromosome 1 and 2, respectively.20 In general, VcFabH1 more efficiently uses short chain acyl-CoAs (C2–C4) with a preference for propanoyl-CoA, while VcFabH2 more efficiently uses medium-length acyl-CoAs (C4–C12) with a preference for octanoyl-CoA.

KAS III enzymes are also known to be involved in the biosynthesis of natural products (aka secondary metabolites). Many of them are involved in the initiation of aromatic polyketide synthases (type II PKSs) that utilize non-acetate starter units. In addition, there are homologues of KAS III, known as KAS III-like enzymes, which are also involved in natural products biosynthesis but catalyse reactions that differ from traditional KAS III enzymes. This review focuses on KAS III and KAS III-like enzymes that are involved in natural products biosynthesis. It is intended to highlight the diverse reactions catalysed by this class of enzymes as opposed to exhaustively discussing all the work related to this superfamily of enzymes.

Classification of KAS III enzymes

The 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS III), also known as 3-oxoacyl-ACP synthase III and β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III, is typically involved in the initial steps of fatty acid biosynthesis. Based on their catalytic function, KAS III enzymes (EC 2.3.1.41) have been classified as members of the acyltransferase group within the transferase family.2,21 This EC classification is solely based on their catalytic reaction without considering the enzymes' structures or substrates, however in recent years there has been an effort to classify enzymes based on the similarity of amino acid sequences and three dimensional (tertiary) structures.22 Based on their condensation mechanism and active site residues, KAS III enzymes are classified as members of the thiolase superfamily,1 which is divided into non-decarboxylative and decarboxylative enzymes. The non-decarboxylative enzymes include the thiolases I and II, the archaea thiolases, and the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) synthases. KAS III proteins are part of the decarboxylative family together with the KS domains of PKSs, the KAS I and II, the plant β-ketoacyl-CoA synthases, and the chalcone synthases. Based on their primary and tertiary sequences, as well as catalytic mechanisms, ketosynthases have also been divided into five families. KAS III proteins have been classified as members of the KS1 family.2 The KS2 family includes plant long-chain fatty acid elongases/condensing enzymes and β-ketoacyl-CoA synthases. The KS3 family consists of the KAS I and II proteins, as well as the KS domains of FASs and PKSs. The KS4 family includes the chalcone synthases and the stilbene synthases (type III PKSs). The KS5 family consists mostly of eukaryotic (mostly animal) fatty acid elongases.2 The proteins and classifications of ketoacyl synthases (KSs) are continually updated as part of the thioester-active enzyme (ThYme) database.21

Crystal structures and catalytic mechanism of KAS III

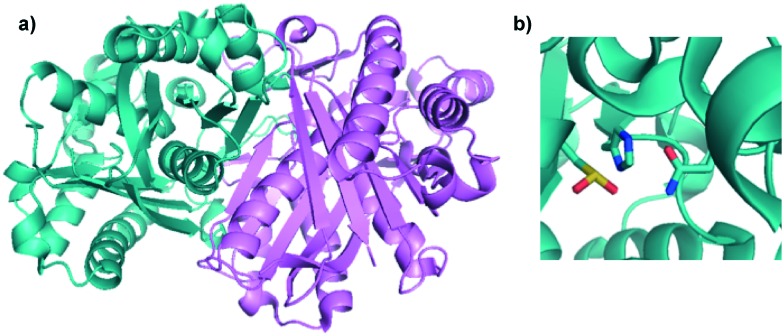

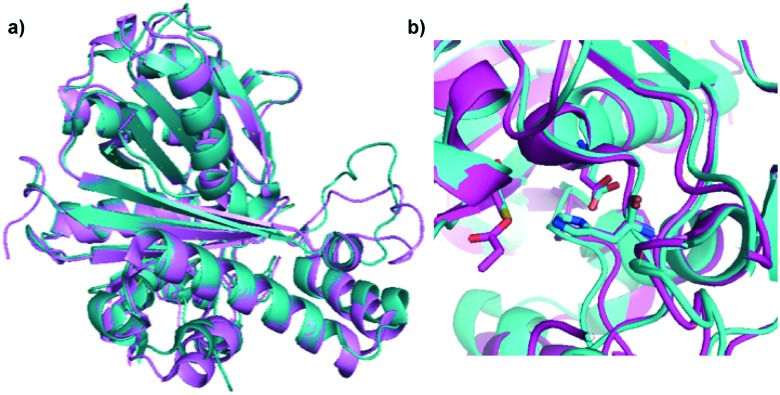

The crystal structures of multiple KAS III enzymes have been solved in recent years.15,23–25 Structurally, the KAS III enzymes contain an α-β-α-β-α layered configuration (Fig. 2). The α layer consists of two α-helices and the β layer consists of five-stranded mixed β-sheets, which is similar to other enzymes in the thiolase superfamily including KAS I and KAS II. Phylogenetic analysis of the thiolase superfamily revealed a divergent evolution that is consistent with the change in their active site architecture and type of reaction/condensation mechanisms.1,4

Fig. 2. Crystal structure of EcFabH. a) Ribbon diagram of FabH from E. coli (PDB ; 3IL9) showing the homodimeric structure of FabH observed in the crystal. The different monomers are coloured teal and violet respectively. b) Zoomed in view of active site of EcFabH showing the Cys112 (as a cysteine dioxide resulting from oxidation)-His244-Asn274 catalytic triad. The carbon atoms are coloured cyan, oxygen atoms are coloured red, nitrogen atoms are coloured blue, and sulphur atoms are coloured yellow. The figure was created in PyMol.

KAS III is a condensation enzyme that is responsible for forming a carbon–carbon bond between acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP in the first step of fatty acid biosynthesis.26 This enzyme adopts a ping-pong mechanism or a double displacement reaction.27 In the case of EcFabH, acetyl-CoA is transferred to a conserved cysteine residue (C112) in a trans-thioesterification to generate an acyl-KAS III intermediate. Malonyl-ACP is then recruited and undergoes decarboxylation to generate the enolate anion, which performs a nucleophilic attack at the acyl-KAS III carbonyl carbon to generate the acetoacetyl-ACP product. X-ray crystal structures of E. coli KAS III protein (EcFabH) revealed the catalytic triad consisted of C112, H244, and N274 (EcFabH numbering) (Fig. 2).23,28 Amino acid substitution of these residues individually revealed that the Cys is required for the transacylation half-reaction while His and Asn were necessary for the decarboxylation of malonyl-ACP.23,28 Also of importance is the “oxyanion hole”, which stabilizes the tetrahedral intermediate generated upon nucleophilic attack of the acyl-KAS III carbonyl carbon. In the case of EcFabH, the oxyanion hole consists of the backbone amide groups of C112, and G306. In the crystal structure of EcFabH, the phenyl ring of F87′ (derived from the second monomer of the homodimer) interacts with the methyl group of acetyl-CoA, providing van der Waals steric interactions that favour the small acyl-CoA substrates acetyl-CoA and propionyl-CoA over longer acyl chains.6,23,28

Interestingly, while the amino acid residues composing the binding pocket of EcFabH are similar to those of SaFabH, the binding pocket of EcFabH is smaller than the binding pocket of SaFabH.15 The larger binding pocket is a reason that SaFabH binds acetyl-CoA with greater affinity (Km 6.18 ± 0.96 μM) compared to EcFabH (Km 40 μM).17,29 The larger pocket is also a major reason that SaFabH can bind a variety of CoA substrates including butyryl-CoA (Km 2.32 ± 0.12 μM), malonyl-CoA (Km 1.76 ± 0.04 μM), and isobutyryl-CoA (Km 0.32 ± 0.04 μM).14,17 It seems that the relaxed substrate specificity of KAS III contributes to the variety of fatty acids produced and may have primed them for evolution to use the diverse substrates found in natural product biosynthetic pathways.

KAS III (FabH) as a target of antibacterial agents

KAS III plays a pivotal role in the initial step of fatty acid biosynthesis by the type II dissociated FAS. It is ubiquitous in bacteria and shows low homology to other condensing enzymes in microorganisms and humans. Therefore, KAS III has become an attractive target for the development of new antibiotics or antibacterial agents. Interestingly, so far only a handful of natural products are shown to have selective activity against KAS III. Among them are platensimycin, platencin, thiolactomycin and thiotetromycin.30–33 However, these natural products not only inhibit KAS III (FabH), but also FabF/B. Nevertheless, using KAS III as a screening tool, a number of compounds which have antibacterial activity have been identified. In vitro enzymatic inhibitory studies with KAS III from E. coli and Staph. aureus have led to a number of 1,2-dithiol-3-ones (which resembles thiolactomycin), that have potent inhibitory activity against KAS III.17,34 Some of these compounds have been proposed to form a covalent adduct with the enzyme via a Michael-type addition elimination reaction mechanism.35 A number of synthetically prepared cyclic sulfones also show good activity against E. coli KAS III, but not Mycobacterium tuberculosis KAS III or Plasmodium falciparum KAS III.36 Alkyl-CoA disulfides (C1 to C10) have been shown to irreversibly inhibit E. coli KAS III and M. tuberculosis KAS III.37 Further crystallographic and kinetic studies with MeSSCoA revealed rapid inhibition of one monomer of E. coli KAS III via formation of a methyl disulfide conjugate with the active site residue cysteine.37

In addition, biochemical screening of a 2500 select compound library has resulted in 27 hits with IC50 < 10 μM against Enterococcus faecalis KAS III.38 Using crystal structure information of the KAS III active site and structure-based drug design approach, one of the four structurally diverse compound series identified was subjected to optimization and QSAR studies, resulting in a number of benzoylaminobenzoic acid derivatives that have excellent KAS III inhibitory activity with IC50 values in the low nM concentration.38,39 Further, using pharmacophore maps from receptor-oriented pharmacophore-based in silico screening and X-ray crystal structures of KAS III enzymes, a number of candidates for KAS III inhibitors were identified.40–42 Some of the compounds showed strong affinity for E. coli KAS III or Staph. aureus KAS III.

While KAS III plays a role for growth in bacteria, not all bacteria are fully dependent on KAS III for their survival. For example, deletion of KAS III gene in Lactobacillus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403 only reduces normal fatty acid biosynthesis by 5–10%. It is proposed that in the absence of KAS III, the initiation step is taken over by KAS II enzymes in this microorganism.43

KAS III and KAS III-like enzymes in natural products biosynthesis

In addition to their role in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, KAS III enzymes are involved in the biosynthesis of many natural products. Particularly, they play a role in starter-unit selection and catalysis of the first chain elongation step in non-acetate-primed PKSs, similar to the role of KS-CLF in the acetate-primed PKSs. Most, if not all, KAS III enzymes that are involved in the initiation of aromatic polyketide synthases show orthogonal acyl carrier protein (ACP) specificity.44 These dedicated priming ACPs are different from those of minimal PKSs in that they contain a tyrosine residue that is important for modulating interactions between KAS III and priming ACPs.44 While ACPs derived from minimal PKSs may be interchangeable and active in other systems without significant kinetic penalties, ACPs derived from initiation PKS modules are usually poor substrates of KS-CLF heterodimers.44

In addition to KAS III proteins that select starter units and catalyse the first chain elongation step in PKSs, there are KAS III-like proteins that have different roles and/or functions in natural product biosynthesis. Some of them are responsible for a head-to-head condensation reaction, others are involved in mevalonate biosynthesis or involved in natural product tailoring processes via C–O bond formation or esterification, as well as amide formation.

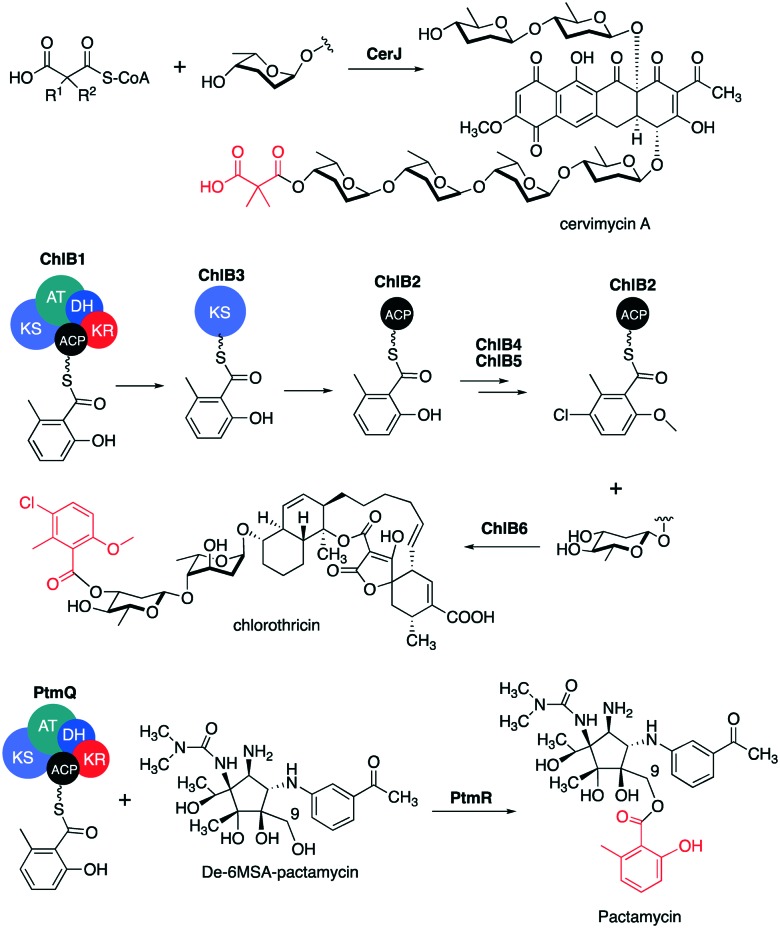

KAS III-like enzymes involved in aromatic polyketide biosynthesis

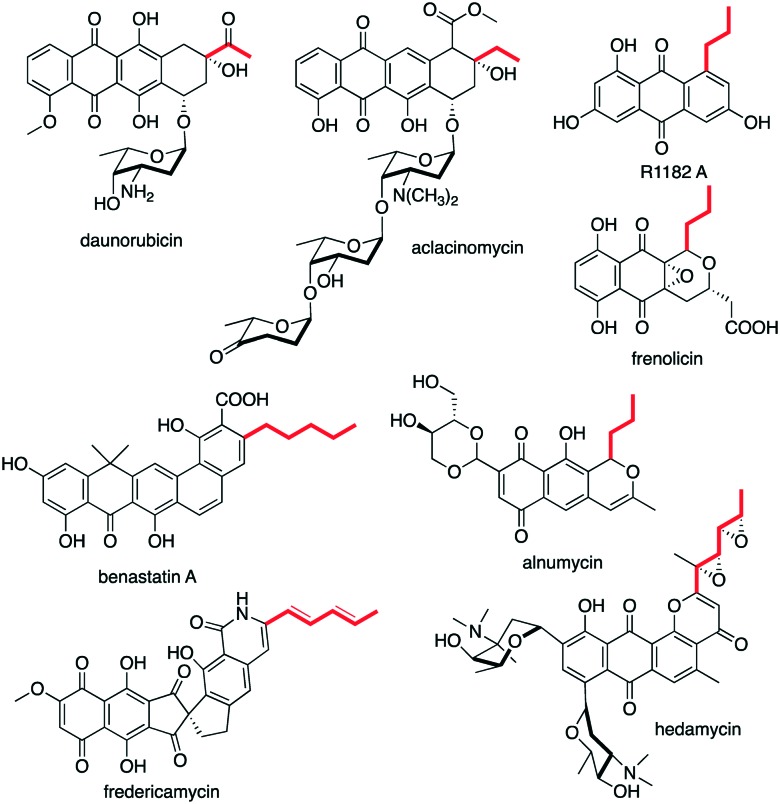

KAS III enzymes that catalyse Claisen condensation are normally involved in the initiation of aromatic polyketide synthases (type II PKSs) that utilize a non-acetate starter unit. Those include DpsC in daunorubicin biosynthesis, BenQ in benastatin biosynthesis, AlnI in alnumycin biosynthesis, ZhuH in R1128 biosynthesis, FrenI (also known as FrnI) in frenolicin biosynthesis, FdmS in fredericamycin A biosynthesis, and HedS in hedamycin biosynthesis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Chemical structures of type II PKS-derived natural products.

The amino acid sequence of DpsC is similar to those of FabH (KAS III), but it does not have the conserved Cys active site residue normally found in KAS III enzymes. Instead, it contains a Ser118 residue which forms a Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad. This non-typical catalytic triad has also been seen in AknE2 (60% identity to DpsC) from the aclacinomycin pathway in Streptomyces galilaeus.45 DpsC and AknE2 appear to possess both the customary KAS III activity (Claisen condensation) as well as an acyltransferase activity.46 They may catalyse a C–C bond formation between propionyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP to obtain β-ketovaleryl-ACP, which is then converted to aklanonic acid, a key intermediate of the daunorubicin and the aclacinomycin pathways. DpsC may also play a role in selecting and covalently binding propionyl-CoA, which is then transferred to DpsG. Heterologous expression of the dpsABCDEFGdauGI genes in Streptomyces lividans provides aklanonic acid, but, interestingly, in the absence of dpsC the mutant still produced aklanonic acid, albeit in a 40 : 60 mixture with desmethylaklanonic acid. Therefore, DpsC was proposed to play a role as a “fidelity factor” more than as an initiation factor in the daunorubicin pathway.47 Earlier study suggested that DpsC is highly substrate specific, as it did not show activity toward malonyl-CoA, 2-methylmalonyl-CoA, or acetyl-CoA.46 However, more recent structural and functional studies revealed that DpsC does not discriminate against short-chain acyl-CoAs (acetyl-, propionyl- and butyryl-) for self-acylation or acyl-transfer.25

The KAS III enzyme BenQ from the benastatin pathway has been found to be essential for providing and selecting the hexanoate starter unit.48 BenQ is similar to KAS III enzymes involved in other aromatic polyketide pathways such as DpsC, ZhuH, FrenI, and HedS. In contrast to DpsC, BenQ contains a catalytic triad, Cys-His-Asn, typical for FabH or KAS III enzymes. Similar to many other KAS III enzymes, BenQ plays a role as a gatekeeper, selecting hexanoate as a starter unit. In the presence of BenQ, no other starter unit is accepted. However, in the absence of the enzyme, the mutant lost its ability to produce any known benastatins. Instead, a number of new penta- and hexacyclic benastatin analogues are produced, presumably arising from linear and branched short-chain fatty acid starter units. The incorporation of these short-chain fatty acids may be mediated by a rather broad substrate specificity FabH from the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway, implying a cross-talk of the ben PKS with the FAS components.

BenQ show high similarity with the AlnI, a KAS III enzyme from the alnumycin pathway in Streptomyces sp. CM020, which contains a typical catalytic triad (Cys-His-Asn).49 Based on its chemical structure, alnumycin has been predicted to be synthesised from a butyryl-CoA starter unit. Although the alnI gene was found in the alnumycin biosynthetic gene cluster,49 it is located apart from the rest of the PKS genes in the cluster. On the other hand, the putative partnering ACP gene alnJ resides in the PKS cluster next to the starter unit acyltransferase gene alnK. While there is no biochemical data to show that AlnI prefers butyryl-CoA as a substrate, cross-complementation of the ΔbenQ mutant with a gene cassette consisting of alnIJK genes resulted in 10-fold enhanced production of the four butyrate-derived benastatin derivatives benastatins F-I.50

The KAS III enzyme ZhuH is involved in the biosynthesis of R1128, a group of anthraquinone natural products that have non-steroidal estrogen receptor antagonist activity.51 Biosynthetically, they are derived from type II PKS, primed by a variety of primer units, such as acetyl, propionyl, butyryl, and isobutyryl units. Analysis of ZhuH revealed a typical catalytic triad of Cys-His-Asn. ZhuH prefers propionyl-CoA and isobutyryl-CoA as starters units compared to butyryl-CoA and acetyl-CoA.52 This is consistent with the high production of the corresponding products, R1128B and R1128C, in the natural and heterologous hosts.51,53 X-ray crystal structures of ZhuH show that the acyl group binding pocket of ZhuH is slightly larger than that of EcFabH.54 This relaxed substrate specificity of ZhuH has been exploited for the production of unnatural polyketides by combining the R1128 initiation module with various minimal PKS such as act (actinorhodin) and tcm (tetracenomycin).55

FrenI from the frenolicin biosynthesis by Streptomyces roseofulvus strain AM-3867 shows amino acid homology to KAS III enzymes such as ZhuH from the R1128 pathway.44 FrenI contains the typical catalytic triad, Cys-His-Asn, and KAS III activity assays using 14C-labeled substrates revealed the preferred substrate of FrenI to be acetyl-CoA > propionyl-CoA > butyryl-CoA.44

Another homologue of ZhuH, known as FdmS (53% identity), is predicted to be involved in the formation of the hexadienyl priming unit in fredericamycin A biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus ATCC 49344.56 Structurally, this type II PKS-derived antitumor antibiotic consists of two similar peri-hydroxy tricyclic aromatic moieties connected with a unique chiral spiro carbon center. Feeding experiments using [1-14C]acetyl- and [1-14C]butyryl-CoA suggested that FdmS can recognise both butyryl-CoA and acetyl-CoA as substrates, albeit the enzyme had >10-fold higher specificity for butyryl-CoA than acetyl-CoA.57 Nonetheless, the fact that FdmS can use acetyl-CoA as a primer indicates that it can catalyse two rounds of Claisen condensation before passing the nascent polyketide chain onto the elongation module.

Another KAS III enzyme, HedS, has been proposed to utilize a hexadienyl starter unit in hedamycin biosynthesis by Streptomyces griseoruber.58 Structurally, hedamycin consists of a planar 4-H-anthra(1,2-b)pyran chromophore, two aminosugars, and a distal bisepoxide-containing side chain. This unusual distal side chain implies the use of a non-acetate priming unit in the polyketide biosynthesis. Similar to DpsC and AknE2, HedS lacks the highly conserved active side residue Cys, which is replaced with Ser. In contrast to fredericamycin A biosynthesis, the hexadienyl starter unit in the hedamycin pathway is produced by an iterative type I PKS system (HedT and HedU). This highlights unusual collaboration between type I and type II PKS systems mediated by the KAS III enzyme HedS. However, interestingly, a later study by Das and Khosla suggested that HedS and the acyltransferase HedF are not involved in chain initiation.59 The hexadienyl starter unit is synthesised by HedU (KS, AT, DH, KR, ACP, KS), possibly in collaboration with HedT (KSq, ATL, ACPL). The product is then directly transferred from the HedU ACP domain to the KS/CLF (HedC/HedD), setting the stage for a chain elongation reaction with a malonyl moiety attached to the HedE ACP domain. It is also suggested that the KS/CLF heterodimer recognizes the HedU ACP domain during chain transfer and the HedE ACP domain during chain elongation.

KAS III-like enzymes that catalyse Claisen condensation in non-type II polyketide biosynthesis

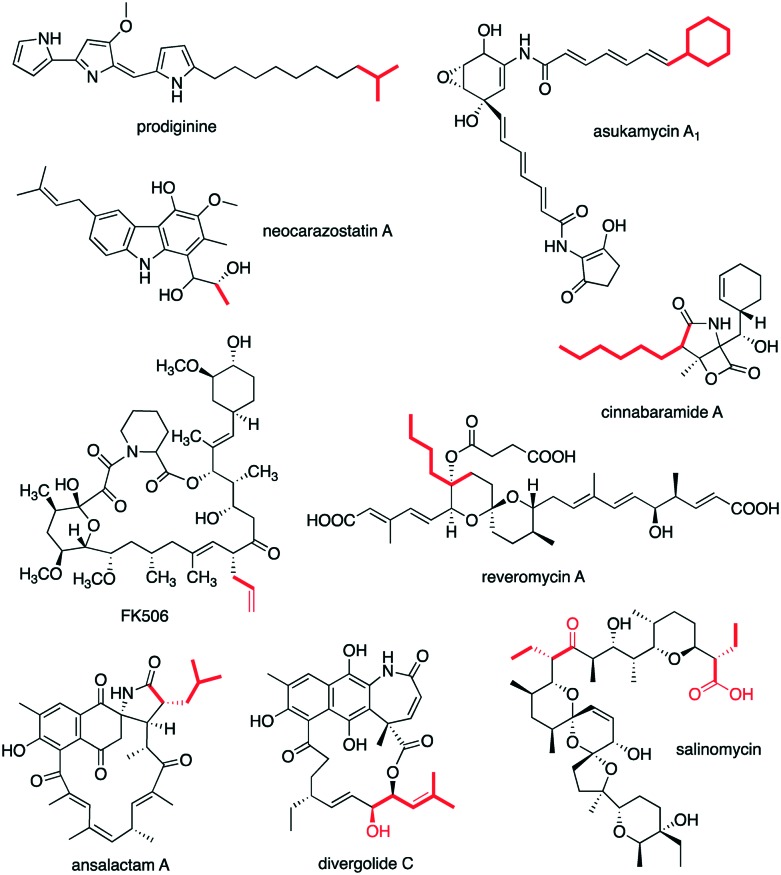

In addition to playing a role in starter-unit selection and catalysis of the first chain elongation step in non-acetate-primed type II polyketide synthases, KAS III enzymes are also involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acid- and type I PKS-derived natural products. For example, a KAS III enzyme, RedP, is involved in prodiginine biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor (Fig. 4). Similar to many other KAS III enzymes, RedP appears to act as a gatekeeper, selecting acetyl-CoA as a starter unit. A redP-deletion mutant of S. coelicolor M511 also produces the natural prodiginines, but at reduced levels, and two new analogues, methylundecylprodiginine and methyldodecylprodiginine.60 Complementing the mutant with a S. glaucescens fabH not only restored the prodiginine levels but also yielded new prodiginines, suggesting that RedP may be replaced with other KAS III enzymes with different substrate specificity to produce novel prodiginines.60

Fig. 4. Chemical structures of non-type II PKS-derived natural products.

A RedP homologue, NzsF, has been found in neocarazostatin biosynthesis by Streptomyces sp. MA37 (Fig. 4).61 NzsF, which contains the typical catalytic triad Cys-His-Asn, has 42% identity with EcFabH.62 Inactivation of nzsF resulted in a mutant strain that does not produce neocarazostatin A. NzsF was proposed to catalyse the thio-Claisen condensation between acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP to obtain acetoacetyl-ACP, the precursor of the 3-hydroxybutyl starting unit in neocarazostatin A biosynthesis. Similar to other KAS III enzymes, NzsF appears to function only with its dedicated ACP partner, NzsE. Inactivation of nzsE also resulted in a mutant that does not produce neocarazostatin A. Although Streptomyces sp. MA37 has two additional ACP genes (fabC1 and fabC2) within its fatty acid biosynthetic gene cluster, they cannot compensate the function of NzsE, in vitro and in vivo.62 In contrast to many other KAS III-like enzymes involved in aromatic polyketide biosynthesis that are primed with non-acetate starter unit, NzsF only uses acetyl-CoA as substrate. While it can also recognize propionyl-CoA and isobutyryl-CoA as substrate, no condensation reaction was observed when mixed with malonyl-NzsE.

Two KAS III encoding genes (asuC3 and asuC4), whose gene products are similar to ZhuH, have been found in the biosynthetic gene cluster of asukamycin in Streptomyces nodosus subsp. asukaensis (Fig. 4).63 Both of these proteins contain the typical KAS III catalytic triad Cys-His-Asn, suggesting their involvement in chain initiation in asukamycin biosynthesis. AsuC3 and AsuC4 are highly similar, therefore, they may form a functional heterodimer. AsuC3/C4 hetereodimer may catalyse the initiation reaction, which is condensation between cyclohexanecarboxylyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP to obtain 3-cyclohexyl-3-oxopropanoyl-ACP. Deletion of asuC3 and asuC4 resulted in no asukamycin A1 production and low-level production of asukamycin congeners A2–A7, suggesting a primer selection function for AsuC3/C4.

In addition to selecting and/or forming non-acetate starter units, KAS III enzymes may also be involved in the formation of polyketide extender units. For example in salinomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces albus DSM41398, a KAS III enzyme (SalQ) is involved in the formation of the butyrate extender unit.64 SalQ is also known as Orf12 in Streptomyces albus XM211.65 However, inactivation of salQ in the producing train only reduced salinomycin production by 36% when compared to wild-type.66

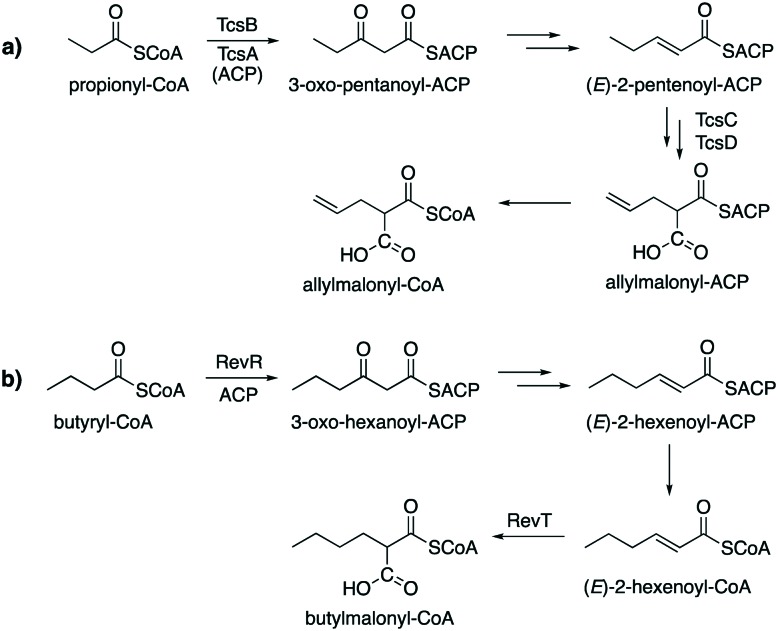

A KAS III enzyme, TcsB, has been found to be involved in allylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis in a number of Streptomyces strains (Fig. 5).67,68 The CoA ester is then used for the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressive agent FK506 (tacrolimus or fujimycin). FK506 is biosynthesized by a combined PKS-NPRS system with allylmalonyl-CoA as an extender unit, forming an allyl side chain on C-21.67 In this pathway, allylmalonyl-CoA is biosynthesized by a set of enzymes, TcsA, TcsB, TcsC, and TcsD, where TcsB plays a role as a propionyl-specific priming KS. TcsB is unique in that it contains two KS domains: the N-terminal domain, which contains all the predicted active site residues and, catalyze the decarboxylative Claisen condensation reaction. The C-terminal domain, which is similar to CLF proteins, is proposed to control the number of Claisen condensations during chain elongation. The product, 2-pentenoyl-ACP, is then converted to propylmalonyl-ACP by the 2-pentenoyl-ACP carboxylase TcsC. Subsequently, the acyl-ACP dehydrogenase TcsD catalyses the formation of the terminal olefin.

Fig. 5. KAS III proteins are involved in the biosynthesis of alkylmalonyl-CoA. a) Formation of allylmalonyl-CoA in FK506 producing strains. b) Formation of butylmalonyl-CoA in reveromycin producing Streptomyces.

In reveromycin biosynthesis, the KAS III enzyme RevR, a homologue of BenQ (55% identity), has been implicated in the selection of butyryl-CoA as a priming substrate to generate 3-oxo-hexanoyl-ACP.69 The product is then converted to (E)-2-hexenoyl-ACP by β-keto processing enzymes (KR, DH) followed by transthioacylation to form (E)-2-hexenoyl-CoA. Subsequently, RevT, a crotonyl-CoA carboxylase homologue, converts (E)-2-hexenoyl-CoA to butylmalonyl-CoA. In contrast to TcsC, RevT does not accept (E)-2-hexenoyl-ACP as a substrate, suggesting that transacylation from (E)-2-hexenoyl-ACP to (E)-2-hexenoyl-CoA occurs prior to the carboxylation.69 Inactivation of revR resulted in a mutant that produces low amounts of reveromycin A, leading to the notion that RevR is involved in the selective production of butylmalonyl-CoA, the precursor of reveromycin A. Genes homologous to revR has also been found in other biosynthetic gene clusters, such as those for cinnabaramide, ansalactam, divergolide, and weishanmycin.69–74

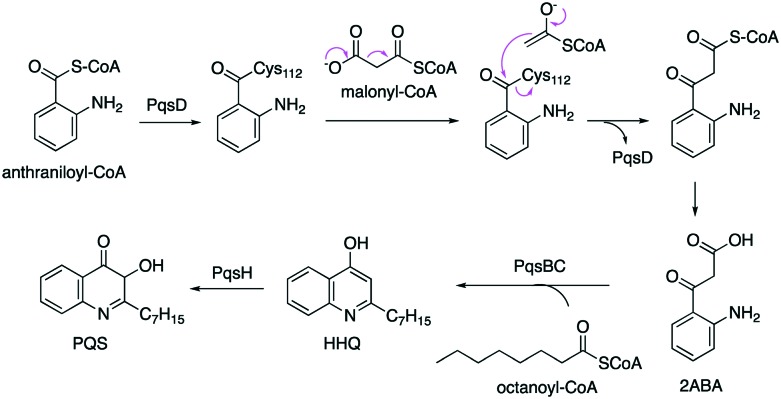

KAS III enzymes are also involved in alkylquinolone biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 6). Pseudomonas alkylquinolones, e.g., 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone (HHQ) and 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (PQS, Pseudomonas quinolone signal), have been known for their participation in quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and production of virulent factors. Biosynthetically, HHQ and PQS are derived from anthranilic acid and fatty acid precursors. Two different KAS III enzymes, PqsBC and PqsD, are involved in their biosynthesis. PqsD is a homodimer FabH-like protein containing a typical Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad. The monomer is composed of two nearly identical α-β-α-β-α domains.75 It catalyses the condensation of anthraniloyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA or malonyl-ACP to give a highly unstable intermediate 2-aminobenzoylacetyl-CoA (2ABA-CoA). The product is then hydrolysed by PqsE, a 2ABA-CoA thioesterase, to give 2-aminobenzoylacetate (2ABA). PqsBC is a heterodimer consisting of PqsB and PqsC that uniquely form a pseudo-2-fold symmetry.76 In addition, PqsC only contains the catalytic dyad lacking an Asn, consisting of Cys129 and His269. On the other hand, PqsB does not contain any conserved catalytic residues, but it may contribute to the formation of the heterodimer. PqsBC catalyses the condensation of octanoyl-CoA and 2-ABA to form HHQ. Hydroxylation of HHQ by a flavin monooxygenase, PqsH, gives PQS.

Fig. 6. Biosynthetic pathway to alkylquinolones in Pseudomonas spp.

KAS III proteins that are responsible for a head-to-head condensation

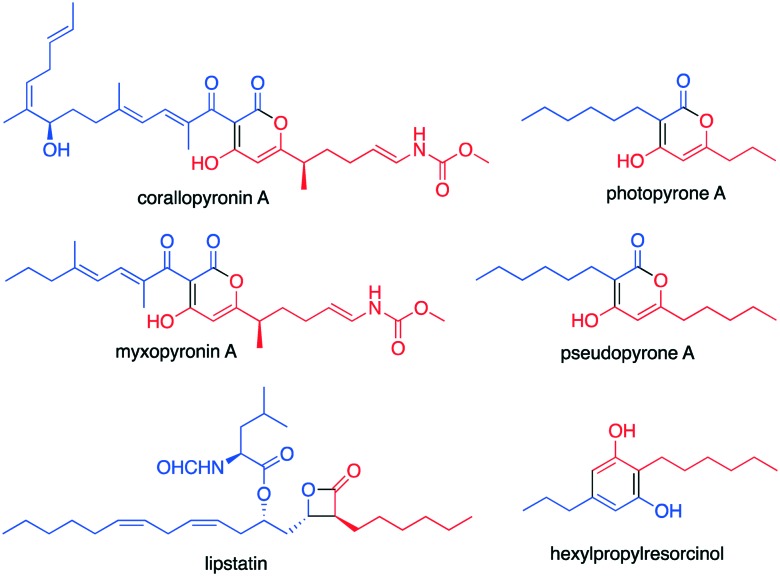

Some KAS III proteins are able to catalyse condensation of two acyl moieties in a head-to-head fashion. While they are rare, ketosynthases that catalyse a head-to-head condensation have been observed in plant type III PKSs.77 In bacteria, such reaction has been observed in the biosynthesis of the antibiotic corallopyronin by the myxobacterium Corallococcus coralloides,78,79 the myxopyronins by Myxococcus fulvus strain Mxf50,80 the photopyrones by the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens,81 the 2,5-dialkylresorcinols in Pseudomonas aurantiaca,82 and lipstatin in Streptomyces toxytricini (Fig. 7).83

Fig. 7. Chemical structures of natural products formed through a head-to-head condensation mechanism catalysed by KAS III-like enzymes.

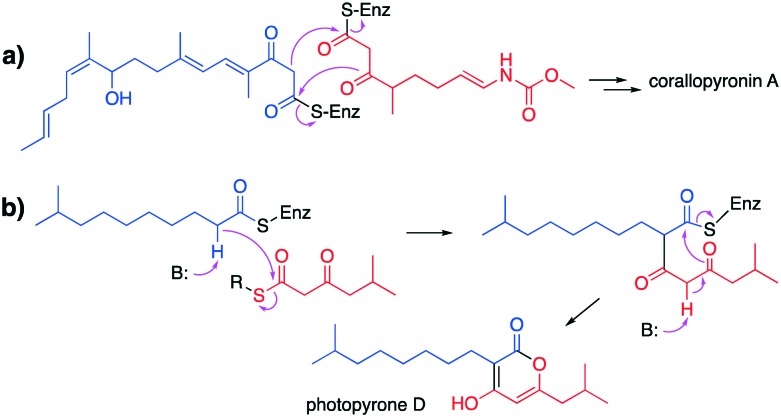

Biosynthetically, corallopyronin A is formed from a PKS-derived and a PKS/NRPS derived subunits, which are interconnected in an unusual head-to-head fashion through Claisen condensation and lactonization catalysed by the KAS III-like enzyme CorB (Fig. 8a).78 CorB contains the Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad common to KAS III enzymes.79 Similar to corallopyronin, myxopyronins are synthesized from a PKS-derived and a PKS/NRPS derived subunit. A gene (mxnB), whose product is homologous to CorB, has been found in the myxopyronin biosynthetic gene cluster.80 MxnB also contains an Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad, and MxnB has been proposed to play a role in α-pyrone ring formation in myxopyronins. MxnB displays a five-layered core structure, α-β-α-β-α, as revealed from its crystal structure.84 While in silico analysis shows sequence similarity between MxnB and FabH (KAS III) enzymes; however, functionally, this enzyme is more closely related to chalcone synthases. In fact, phylogenetic analysis of MxnB shows that it is located between FabH-like and CHS-type enzymes.

Fig. 8. Proposed head-to-head condensation mechanisms catalysed by KAS III-like enzymes. a) Formation of the α-pyrone moiety in corallopyronin A biosynthesis. b) Formation of the α-pyrone moiety in photopyrone D biosynthesis.

Similar to corallopyronin and myxopyronin, the photopyrones also contain an α-pyrone moiety in their structures. The α-pyrone moiety has been proposed to be formed by the KAS III-like protein, photopyrones synthase (PpyS), through a head-to-head condensation of two fatty acid thioesters. PpyS contains a Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad common to FabH enzymes. In contrast to CorB and MxnB from the corallopyronin and myxopyronin pathways, PpyS has a glutamic acid residue (E105′) that reaches inside the binding pocket of the adjacent monomer. This catalytically important residue is predicted to act as a base that deprotonates the α-carbon of the substrate 9-methyldecanoyl thioester (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, the residue is replaced with V94 in both CorB and MxnB. Since the α-carbons of the substrates for CorB and MxnB are flanked by two carbonyl groups (as opposed to one in 9-methyldecanoyl thioester), CorB and MxnB may not need a dedicated base to deprotonate their substrates, suggesting a distinct catalytic mechanism. In fact, phylogenetic analysis of PpyS and other known ketosynthases revealed that PpyS is distantly related to CorB and MxnB. Through amino acid sequence similarity, another PpyS homologue, named PyrS (pseudopyronine synthase), was discovered in the pseudopyronine pathway in Pseudomonas sp. GM30. Introduction of the pyrS gene into Pseudomonas putida KT 2440 resulted in the production of pseudopyronine analogues in this strain. In addition, high level of pseudopyronines A–C was detected when pyrS was homologously expressed in Pseudomonas sp. GM30.

In Pseudomonas aurantiaca (Pseudomonas chlororaphis subsp. aurantiaca), 2,5-dialkylresorcinols are formed from two fatty acid-derived precursors via a head-to-head-condensation. A set of three proteins, DarA, DarB, and DarC, have been found to be responsible for this reaction. DarB, a KAS III-like protein, plays a role in the selection of the fatty acid precursors, but it does not directly catalyse the head-to-head condensation.82 DarB contains a typical KAS III catalytic triad (Cys-His-Asn) and selects medium-chain-length fatty acid derived precursors, such as octanoic acid. Together with DarC (an ACP) it catalyses a single chain extension to give β-ketodecanoyl-ACP. Head-to-head condensation between β-ketodecanoyl-ACP and β-ketohexanoyl-ACP or -CoA followed by decarboxylation and aromatisation would give hexylpropylresorcinol (Fig. 7). All these transformations appear to be catalysed by DarA.82 Heterologous expression of darABC from Chitinophaga pinensis DSM 2588 in E. coli led to the production of a number of dialkylresorcinols.85 This class of compounds appears to be produced by many bacteria from taxonomically distinct lineages.86 More than 100 genomes of different bacteria have been reported to contain the darABC clusters. Phylogenetic analysis showed that DarB homologues form a novel clade of ketosynthases, distinct from FabH and DpcS-like KAS III proteins.85

Recently, a heterodimer enzyme consisting of LstA and LstB have been found to catalyse a rare head-to-head condensation of two monomers of [2E]-octanyl-CoA or [2E]-octenyl-CoA and [3S,5Z,8Z]-3-hydroxytetradeca-5,8-dienoic acid (C14), to produce the β-lactone moiety in lipstatin.83 LstA and LstB are both KAS III homologues, sharing 23% sequence identity between them. Interestingly, while LstA contains a typical Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad, LstB lacks these conserved active site residues. However, it appears that a non-covalent interaction between LstA and LstB is critical for these proteins to be soluble in solution. Expression of lstA or lstB individually in E. coli cannot produce a soluble recombinant protein, whereas co-expression of the genes in E. coli resulted in soluble proteins. Interestingly, substitution of Asn to Ala of the LstA catalytic triad and co-expression of this variant with LstB produced an insoluble heterodimer protein.

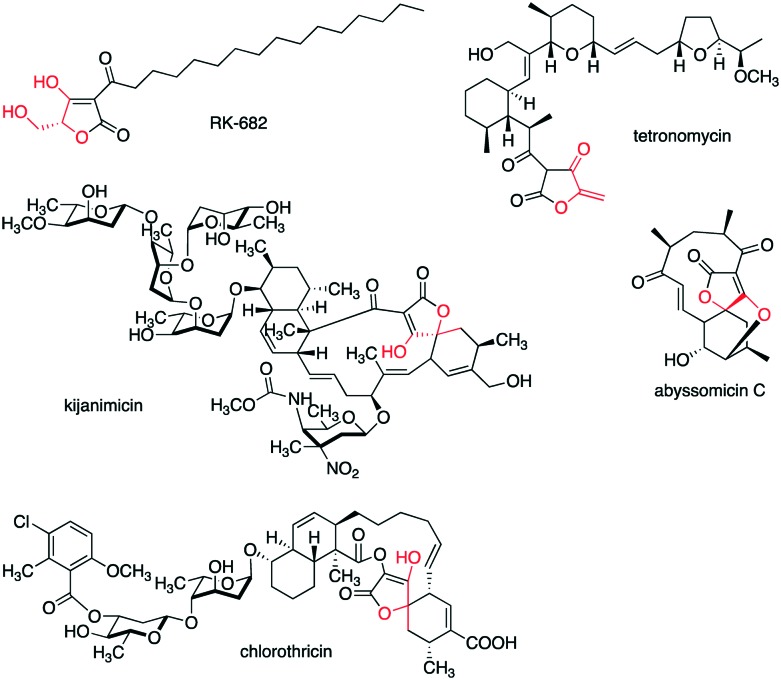

KAS III-like enzymes that are responsible for tetronate formation

Combined Claisen condensation and lactonization reactions by KAS III-like enzymes have also been found involved in the formation of tetronate units in microbial natural products (Fig. 9). Among them is RkD, a FabH homologue involved in the biosynthesis of 3-hexadecanoyl-5-hydroxymethyl-tetronic acid (RK-682) in Streptomyces sp. 88–682.87 RkD is proposed to catalyse C-C bond formation followed by either an enzymatic or a spontaneous C–O bond formation (Fig. 10). While RkD contains the active site Cys residue, it lacks the conserved His residue implicated in decarboxylation by FabH. This seems to be consistent with RkD homologues in other tetronate biosynthetic pathways, including that of abyssomicin, tetromycin, kijanimicin, and chlorothricin.

Fig. 9. Chemical structures of tetronate-containing natural products.

Fig. 10. Proposed mode of formation of the tetronate moiety in RK-682.

In abyssomicin biosynthesis in Verrucosispora AB-18-032, the RkD homologue AbyA1 has been proposed to be involved in the formation of the tetronate moiety.88 Deletion of the gene, abyA1, resulted in a mutant that does not produce the abyssomicins. A similar gene was also found in the biosynthetic gene cluster of the polyether ionophoric antibiotic tetronomycin in Streptomyces sp. NRRL11266.89 Inactivation of tmn15, whose product is a homologue of RkD, yielded no tetronomycin production, indicating that Tmn15 is also involved in tetronate formation in tetromycin biosynthesis. Similarly, KijB, which is homologous to EcFabH, has been proposed to catalyse the tetronate formation in kijanimicin biosynthesis in Actinomadura kijaniata SCC1256.90 Specifically, it catalyses the condensation between a carbanion C-2 of kijanolide polyketide-S-ACP-11 and glycerol-CoA to the branched chain intermediate tethered to ACP. In the chlorothricin biosynthetic gene cluster, a KAS III encoding gene, chlM, was proposed to be involved in the formation of glyceryl-S-ACP, the building block for the C-3 unit involved in tetronate formation. However, disruption of chlM in Streptomyces antibioticus DSM 40725 did not affect the antibiotic production,91 suggesting the formation of glyceryl-S-ACP from a glycolytic pathway intermediate is more likely to be catalysed by ChlD1, a homologue of FkbH, which has been shown to catalyse the formation of glyceryl-S-ACP. In tetronomycin biosynthesis, a homologue of FkbH, Tmn16, has also been shown to catalyse this reaction.92

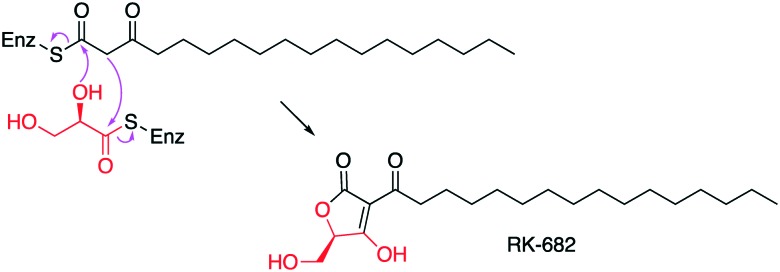

KAS III-like enzymes that are involved in the mevalonate pathway

The mevalonate pathway is an essential biosynthetic machinery in many organisms, as it produces isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), the building blocks of isoprenoids and steroids. Typically, this pathway uses two molecules of acetyl-CoA to produce acetoacetyl-CoA, which is then converted to IPP and DMAPP by a set of enzymes including the HMG-CoA synthases and the HMG-CoA reductases. Condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA to acetoacetyl-CoA is usually catalysed by the acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase. However, more recently, a KAS III homologue, NphT7, has been found to produce acetoacetyl-CoA in Streptomyces sp. strain CL190.93 Interestingly, instead of using two molecules of acetyl-CoA, NphT7 uses acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA to produce acetoacetyl-CoA (Fig. 11), indicating the involvement of a decarboxylation reaction. NphT7 appears to have a similar condensation mechanism to that of KAS III enzymes except that NphT7 does not use ACP-bound substrates. NphT7 contains a highly conserved catalytic triad Cys-His-Asn, where the Cys115 appears to be a key catalytic residue for the condensation reaction. Substitution of the Cys115 residue in NphT7 yielded no acetoacetyl-CoA production. On the other hand, more acetyl-CoA, from the decarboxylation of malonyl-CoA, was accumulated in the cells. In contrast to acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase, NphT7 does not have thiolysis activity. Therefore, it is suggested that NphT7 is commercially more beneficial than the thiolase, as it can elevate mevalonate levels; thus, it may be used to increase the production of economically valuable terpenoids such as carotenoids, the anticancer drug taxol, and the antimalarial agent artemisinin.93

Fig. 11. Formation of acetoacetyl-CoA and its analogues by KAS III-like enzymes.

Although it is not involved in the mevalonate pathway, a similar transformation has been observed from the KAS III-like enzyme ThgI in trehangelin biosynthesis in the endophytic actinomycete Polymorphospora rubra K07-0510.94 Similar to NphT7, ThgI catalyses the condensation of acetyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA to give 2-methylacetoacetyl-CoA (Fig. 11), which is then converted to angelyl-CoA via 3-hydroxy-2-methylbutyryl-CoA (HMB-CoA). Angelyl-CoA is then used to esterified trehalose to give the trehangelins. ThgI contains a common Cys-His-Asn catalytic triad and has 46% identity to the KAS III protein SsfN from Streptomyces sp. SF2575. The latter protein is involved in the biosynthesis of the antitumor compound tetracycline SF2575, whose structure also contains angelyl moiety.95 Expression of a gene cassette containing ssfENKJ genes from the SF2575 strain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in combination with exogenous supplies of carboxylic acid precursors produced angelyl-CoA.96

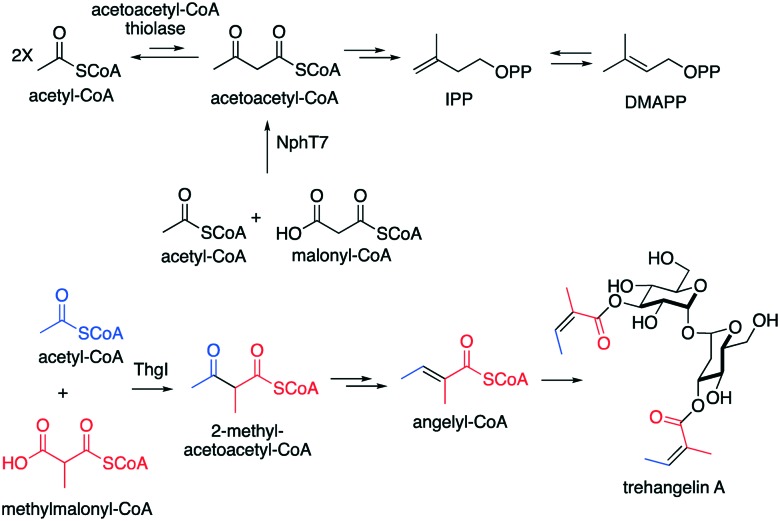

KAS III-like enzymes that catalyse ester formation

Although the typical KAS III enzymes catalyse decarboxylative C–C bond formation via a thioester-dependent Claisen condensation reactions, a number of KAS III-like enzymes have been found to catalyse C–O bond formation (Fig. 12). Those include CerJ from the cervimycin pathway in Streptomyces tendae strain HKI 0179,97 ChlB6 from the chlorothricin pathway in Streptomyces antibioticus DSM 40725,91 and PtmR from the pactamycin pathway in Streptomyces pactum.98,99

Fig. 12. Esterification reactions catalysed by KAS III-like enzymes.

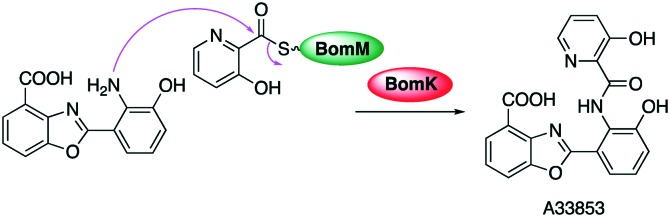

Cervimycin C consists of a tetracyclic polyketide, six trideoxyhexose sugars, and a dimethylmalonyl moiety attached to the 4′ position of the trideoxyhexose tetramer. The KAS III-like protein (CerJ) has been found to transfer a malonyl moiety from malonyl-CoA to a sugar residue of cervimycin. While KAS III usually has a conserved catalytic triad of Cys-His-Asn, or Ser-His-Asp as in the case of DpsC and its homologues, CerJ has Cys-His-Asp (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Crystal structures of DpsC and CerJ. a) Aligned ribbon diagrams of CerJ (cyan, PDB 3S3L) and DpsC (violet, PDB ; 5WGC) showing the high degree of tertiary structure similarity between these two enzymes. b) A zoomed in picture of the catalytic triad residues from panel a demonstrating the similarity in active site architecture between DpsC (carbon atoms are coloured violet) and CerJ (carbon atoms are coloured cyan). In both structures, oxygen atoms are coloured red, nitrogen atoms are coloured blue and sulphur atoms are coloured yellow. The catalytic triad of CerJ is Cys-his-asp while in DpsC it is Ser-his-asp. In DpsC, the active site Ser is trapped as the propionyl ester. The figure was created in PyMol.

In chlorothricin biosynthesis, there are two KAS III-like enzymes (ChlB3 and ChlB6) involved in the pathway.91 ChlB3 was found to transfer a 6-methylsalicylyl moiety from the iterative type I PKS ChlB1 to the acyl carrier protein ChlB2.100 The ChlB2-tethered acyl group is then chlorinated and O-methylated by the halogenase ChlB4 and the methyltransferase ChlB5 to give 5-chloro-6-methyl-O-methyl-salicylyl-ChlB2. The modified acyl group is then transferred to the 3-hydroxyl group of the d-olivose unit of desmethylsalicylyl-chlorothricin by ChlB6, to yield chlorothricin.

A ChlB6 homologue, PtmR, was found in the pactamycin pathway in Streptomyces pactum. However, although PtmR is highly similar to ChlB6, detailed characterization of the enzyme revealed that PtmR can directly transfer a 6-methylsalicylyl (6MSA) moiety from an iterative type I PKS (PtmQ) to the aminocyclopentitol unit of pactamycin.101 PtmR does not require a discrete ACP to be active and does not utilize CoA esters as acyl donors, but it can recognize a variety of S-acyl-N-acetylcysteamines as acyl donors. Interestingly, the promiscuity of PtmR is not only with the acyl donors, but also with the acceptors, as it can process multiple acceptors such as de-6MSA-pactamycin and its congeners.102

A number of other KAS III-like proteins have been proposed to catalyse ester formation. Those include AviN from the biosynthetic pathway to avilamycin in Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü57, EvrI from the biosynthetic pathway to evernimicin in Micromonospora carbonacea, CalO4 from the biosynthetic pathway to calicheamycin from Micromonospora echinospora, and CloN2 and CloN7 from the clorobiocin pathway in Streptomyces roseochromogenes DS12.976.103–107 AviN and EvrI were found to be similar to DpsC from Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 29050. EvrI was proposed to form EvrI-Cys-S-acetyl and initiates orsellinic acid synthesis by condensation with EvrJ-ACP-malonyl to form EvrI-ACP-acetoacetyl. In addition, the product of pokM2 from the biosynthetic gene cluster of polyketomycin in Streptomyces diastatochromogenes Tü6028 is similar to AviN from the avilamycin pathway.108 A KAS III protein has also been found in the tiacumicin (fidaxomicin) pathway in Dactylosporangium aurantiacum subsp. hamdenensis NRRL 18085.103 The protein, TiaF, is similar to ChlB3 (58% identity) and ChlB6 (34% identity), CalO4 (55% identity) and AviN (51% identity).103 TiaF has been proposed to catalyse transfer of the homo-orsellinic acid moiety to the 2-O-methyl-d-rhamnose residue.103 A gene encoding KAS III protein, esmD1, was also found in the esmeraldin biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces antibioticus Tü 2706.109 EsmD1, which is similar to EcFabH and ChlB6, has been proposed to catalyse the transfer of 6MSA to saphenic acid.109

KAS III-like enzymes that catalyse amide formation

A homologue of KAS III, BomK, has been found to catalyse an amide formation in the biosynthesis of A3385, an anti-leishmanial benzoxazole compound isolated from Streptomyces sp. NRRL 12068 (Fig. 14).110,111 Gene inactivation and biochemical analysis using N-terminal small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO)-tagged recombinant BomK revealed that BomK catalyses the coupling between 3-hydroxypicolinic and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid to obtains A33853.110

Fig. 14. Amide formation by a KAS III-like enzyme.

Conclusions

Although KAS III enzymes have been known to play a critical role in fatty acid biosynthesis, their involvement in secondary metabolism has yet to be fully appreciated. In polyketide and fatty acid-derived natural products biosynthesis, KAS III enzymes typically catalyse C–C bond formation through a decarboxylative Claisen condensation type reaction. These enzymes are particularly common in aromatic polyketide biosynthetic machineries that use non-acetate starter units, but they are also found in the biosynthetic pathways of other important polyketides such as FK506, asukamycin, reveromycin, and salinomycin. KAS III proteins are widely distributed in bacterial kingdom. In Pseudomonas spp., they play a key role in the biosynthesis of alkylquinolones, compounds that are involved in quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and production of virulent factors.

In addition to the typical KAS III enzymes, some variants of KAS III proteins display unusual catalytic functions. For example, Cor B from the corallopyronin pathway and MxnB from the myxopyronin pathway catalyse a non-decarboxylative condensation of two acyl-CoAs via a head-to-head fashion to form a lactone structure. Similarly, KAS III enzymes are involved in the formation of the tetronate moiety of important polyketide natural products, e.g., tetromycin, kijanimicin, RK-682, and abyssomicin. They catalyse the formation of a C–C bond and a C–O bond, although the latter may be formed either enzymatically or spontaneously formed, leading to the formation of a five-membered tetronate ring. KAS III-like enzymes have also been found to provide an alternative source of acetoacetyl-CoA of the mevalonate pathway, or to produce analogues of acetoacetyl-CoA as building blocks for natural products biosynthesis.

Another group of KAS III-like enzymes can catalyse esterification or amidation reactions as part of tailoring processes of natural products. Some of them use acyl-CoAs as substrates (e.g., CerJ from the cervimycin pathway), while others use acyl-ACPs as substrates (e.g., ChlB6 from the chlorothricin pathway). In pactamycin biosynthesis, the KAS III-like enzyme PtmR can directly transfer a 6-methylsalicylyl moiety from an iterative type I PKS to the aminocyclopentitol unit of pactamycin. In addition, there are many other KAS III-like proteins that have been implicated in the biosynthesis of bioactive natural products, however, their detailed biochemical studies have yet to be performed.

While many KAS III enzymes function as a fidelity factor or a gate keeper, some of them have relaxed substrate specificity. This relaxed substrate specificity has been exploited for the production of unnatural polyketides. Of particular interest is the KAS III-like protein PtmR from the pactamycin pathway that is able to recognize a wide array of S-acyl-N-acetylcysteamines as substrates to produce a suite of pactamycin derivatives with diverse alkyl and aromatic sidechains, highlighting the versatility of some KAS III-like enzymes as tools for chemoenzymatic structural modifications.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RN and YN thank American Indonesian Exchange Foundation (AMINEF)/Fulbright and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), respectively, for providing scholarships. This work was supported by grant AI129957 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Biographies

Risa Nofiani

Risa Nofiani received her B.Sc. in chemistry from the University of Riau and M.Sc. from Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia. She then obtained her Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Bristol, UK. Since 2000, she is a lecturer at the University of Tanjungpura, Indonesia. Her research is focused on microbial natural product discovery and biosynthesis using various approaches, such as bioinformatics, metabolomics and molecular biology.

Benjamin Philmus

Benjamin (BJ) Philmus is an assistant professor of medicinal chemistry at Oregon State University. He obtained his doctorate from the University of Hawaii at Manoa under the tutelage of Prof. Thomas Hemscheidt and then joined the group of Prof. Tadhg Begley at Texas A&M University as a postdoctoral research associate. BJ joined the faculty in the College of Pharmacy at OSU in 2013. His research interests are focused on natural products and include synthetic biology, heterologous expression of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters, and characterizing the interesting enzymology that Nature has developed.

Yosi Nindita

Yosi Nindita received her B.Sc. from Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia and her M.Sc. and Ph.D. from Hiroshima University, Japan, where she worked on genome evolution of Streptomyces. She held a postdoctoral fellowship at Hiroshima University and is a visiting scholar at Oregon State University under the support of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) foundation. She works with Prof. Taifo Mahmud on the discovery of natural product from Streptomyces.

Taifo Mahmud

Taifo Mahmud is a Professor in the College of Pharmacy and an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Chemistry at Oregon State University (OSU). Prior to coming to OSU, he was a Research Assistant Professor and Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Washington. He received his Ph.D. and M.Sc. from Osaka University. His research interests are broadly in drug discovery and development. His group employs a multidisciplinary approach that utilizes cutting-edge technologies in molecular genetics, enzymology, and chemistry to produce novel pharmaceuticals. He has over 25 years of experience working on natural products chemistry and biosynthesis.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9md00162j

References

- Jiang C., Kim S. Y., Suh D. Y. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;49:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Kelly E. E., Masluk R. P., Nelson C. L., Cantu D. C., Reilly P. J. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1659–1667. doi: 10.1002/pro.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago G., Diacovich L., Arabolaza A., Tsai S. C., Gramajo H. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011;35:475–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapalainen A. M., Merilainen G., Wierenga R. K. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beld J., Lee D. J., Burkart M. D. Mol. BioSyst. 2015;11:38–59. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00443d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S. W., Zheng J., Zhang Y. M., Rock C. O. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:791–831. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Brors B., Massow M., Weiss H. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. K., Witkowski A., Smith S. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2515–2523. doi: 10.1021/bi971886v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. C., Rock C. O., White S. W. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4136–4143. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.14.4136-4143.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. G., Kadziola A., von Wettstein-Knowles P., Siggaard-Andersen M., Lindquist Y., Larsen S. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diomande S. E., Nguyen-The C., Guinebretiere M. H., Broussolle V., Brillard J. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:813. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud T., Bode H. B., Silakowski B., Kroppenstedt R. M., Xu M., Nordhoff S., Hofle G., Muller R. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32768–32774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud T., Wenzel S. C., Wan E., Wen K. W., Bode H. B., Gaitatzis N., Muller R. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:322–330. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Lobo S., Reynolds K. A. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4481–4486. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4481-4486.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Choudhry A. E., Janson C. A., Grooms M., Daines R. A., Lonsdale J. T., Khandekar S. S. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2087–2094. doi: 10.1110/ps.051501605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbadi A., Brummel M., Schütt B. S., Slabaugh M. B., Schuch R., Spener F. Biochem. J. 2000;345:153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Reynolds K. A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1310–1318. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1310-1318.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Kremer L., Besra G. S., Rock C. O. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:28201–28207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H., Heath R. J., Rock C. O. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:365–370. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.365-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J., Zheng H., Tzou W. S., Cooper D. R., Chruszcz M., Chordia M. D., Kwon K., Grabowski M., Minor W. Rev. Geophys. 2018;285:2900–2921. doi: 10.1111/febs.14588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu D. C., Chen Y., Lemons M. L., Reilly P. J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D342–346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt J. A., Babbitt P. C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:209–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Janson C. A., Konstantinidis A. K., Nwagwu S., Silverman C., Smith W. W., Khandekar S., Lonsdale J., Abdel-Meguid S. S. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:36465–36471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daines R. A., Pendrak I., Sham K., Van Aller G. S., Konstantinidis A. K., Lonsdale J. T., Janson C. A., Qiu X., Brandt M., Khandekar S. S., Silverman C., Head M. S. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5–8. doi: 10.1021/jm025571b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. R., Shakya G., Patel A. B., Mohammed L. Y., Vasilakis K., Wattana-Amorn P., Valentic T. R., Milligan J. C., Crump M. P., Crosby J., Tsai S. C. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018;13:141–151. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K., Jackowski S., Rock C. O., Cronan, Jr. J. E. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. J., White S. W., Rock C. O. Prog. Lipid Res. 2001;40:467–497. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C., Heath R. J., White S. W., Rock C. O. Structure. 2000;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. J., Rock C. O. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:10996–11000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Kodali S., Lee S. H., Galgoci A., Painter R., Dorso K., Racine F., Motyl M., Hernandez L., Tinney E., Colletti S. L., Herath K., Cummings R., Salazar O., Gonzalez I., Basilio A., Vicente F., Genilloud O., Pelaez F., Jayasuriya H., Young K., Cully D. F., Singh S. B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:7612–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700746104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang R., Liang J., Yi Y., Liu Y., Wang J. Molecules. 2015;20:16127–16141. doi: 10.3390/molecules200916127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. C., Choi K. H., Heath R. J., Li Z., White S. W., Rock C. O. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6551–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K., Jayasuriya H., Ondeyka J. G., Herath K., Zhang C., Kodali S., Galgoci A., Painter R., Brown-Driver V., Yamamoto R., Silver L. L., Zheng Y., Ventura J. I., Sigmund J., Ha S., Basilio A., Vicente F., Tormo J. R., Pelaez F., Youngman P., Cully D., Barrett J. F., Schmatz D., Singh S. B., Wang J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:519–526. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.519-526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Reeve A. M., Desai U. R., Kellogg G. E., Reynolds K. A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3093–3102. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3093-3102.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom A. G., Kelly V., Marles-Wright J., Cockroft S. L., Campopiano D. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:6310–6313. doi: 10.1039/c7ob01396e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhamadsheh M. M., Waters N. C., Huddler D. P., Kreishman-Deitrick M., Florova G., Reynolds K. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:879–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhamadsheh M. M., Musayev F., Komissarov A. A., Sachdeva S., Wright H. T., Scarsdale N., Florova G., Reynolds K. A. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Perretta C., Lu J., Su Y., Margosiak S., Gajiwala K. S., Cortez J., Nikulin V., Yager K. M., Appelt K., Chu S. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1596–1609. doi: 10.1021/jm049141s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Soni L. K., Gupta M. K., Prabhakar Y. S., Kaskhedikar S. G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2008;43:1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Jeong K. W., Lee J. U., Kang D. I., Kim Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Jeong K. W., Shin S., Lee J. U., Kim Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5408–5413. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Jeong K. W., Shin S., Lee J. U., Kim Y. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;47:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. Y., Cronan J. E. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51494–51503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Lee T. S., Kobayashi S., Khosla C. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6588–6595. doi: 10.1021/bi0341962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raty K., Kantola J., Hautala A., Hakala J., Ylihonko K., Mantsala P. Gene. 2002;293:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W., Sheldon P. J., Hutchinson C. R. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9752–9757. doi: 10.1021/bi990751h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajgarhia V. B., Priestley N. D., Strohl W. R. Metab. Eng. 2001;3:49–63. doi: 10.1006/mben.2000.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Schenk A., Hertweck C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6022–6030. doi: 10.1021/ja069045b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oja T., Palmu K., Lehmussola H., Lepparanta O., Hannikainen K., Niemi J., Mantsala P., Metsa-Ketela M. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1046–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Metsa-Ketela M., Hertweck C. J. Biotechnol. 2009;140:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti T., Hu Z., Pohl N. L., Shah A. N., Khosla C. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33443–33448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows E. S., Khosla C. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14855–14861. doi: 10.1021/bi0113723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y., Abe Y., Ezaki M., Goto T., Okuhara M., Kohsaka M. J. Antibiot. 1993;46:1055–1062. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Tsai S., Meadows E. S., Miercke L. J., Keatinge-Clay A. T., O'Connell J., Khosla C., Stroud R. M. Structure. 2002;10:1559–1568. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Lee T. S., Khosla C. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E31. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt-Pienkowski E., Huang Y., Zhang J., Li B., Jiang H., Kwon H., Hutchinson C. R., Shen B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16442–16452. doi: 10.1021/ja054376u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Szu P. H., Fitzgerald J. T., Khosla C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8831–8833. doi: 10.1021/ja102517q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bililign T., Hyun C. G., Williams J. S., Czisny A. M., Thorson J. S. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:959–969. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Khosla C. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo S., Kim B. S., Reynolds K. A. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Elsayed S. S., Lv M., Tabudravu J., Rateb M. E., Gyampoh R., Kyeremeh K., Ebel R., Jaspars M., Deng Z., Yu Y., Deng H. Chem. Biol. 2015;22:1633–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L., Zhang R., Kyeremeh K., Deng Z., Deng H., Yu Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:3843–3848. doi: 10.1039/c7ob00617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Z., Petrickova K., Skanta F., Pospisil S., Yang Y., Chen C. Y., Tsai S. F., Floss H. G., Petricek M., Yu T. W. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:24915–24924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Hoffmann M., Bian X., Tu Q., Yan F., Xia L., Ding X., Stewart A. F., Muller R., Fu J., Zhang Y. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15081. doi: 10.1038/srep15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Wang H., Kang Q., Liu J., Bai L. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:994–1003. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06701-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovich M. E., Tyrakis P. A., Hong H., Sun Y., Samborskyy M., Kamiya K., Leadlay P. F. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:66–71. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo S., Kim D. H., Lee J. H., Park J. W., Basnet D. B., Ban Y. H., Yoo Y. J., Chen S. W., Park S. R., Choi E. A., Kim E., Jin Y. Y., Lee S. K., Park J. Y., Liu Y., Lee M. O., Lee K. S., Kim S. J., Kim D., Park B. C., Lee S. G., Kwon H. J., Suh J. W., Moore B. S., Lim S. K., Yoon Y. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:976–985. doi: 10.1021/ja108399b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo S., Lee S. K., Jin Y. Y., Suh J. W. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016;26:233–240. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1506.06032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa T., Takahashi S., Kawata A., Panthee S., Hayashi T., Shimizu T., Nogawa T., Osada H. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:26994–27011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid S., Huo L., Herrmann J., Stadler M., Kopcke B., Bitzer J., Muller R. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:922–931. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. C., Nam S. J., Gulder T. A., Kauffman C. A., Jensen P. R., Fenical W., Moore B. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1971–1977. doi: 10.1021/ja109226s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Baunach M., Ding L., Peng H., Franke J., Hertweck C. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:1274–1279. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.-R., Sun M.-W., He H.-G., Wang H.-X., Li Y.-Y., Lu C.-H., Shen Y.-M. Gene. 2014;544:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G., Xu Z., Guo Z., Hindra M. Ma, Yang D., Zhou H., Gansemans Y., Zhu X., Huang Y., Zhao L. X., Jiang Y., Cheng J., Van Nieuwerburgh F., Suh J. W., Duan Y., Shen B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E11131–E11140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716245115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bera A. K., Atanasova V., Robinson H., Eisenstein E., Coleman J. P., Pesci E. C., Parsons J. F. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8644–8655. doi: 10.1021/bi9009055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drees S. L., Li C., Prasetya F., Saleem M., Dreveny I., Williams P., Hennecke U., Emsley J., Fetzner S. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:6610–6624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.708453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin M. B., Noel J. P. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003;20:79–110. doi: 10.1039/b100917f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol O., Schaberle T. F., Schmitz A., Rachid S., Gurgui C., El Omari M., Lohr F., Kehraus S., Piel J., Muller R., Konig G. M. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1253–1265. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocher G., Vilstrup J., Heine D., Hallab A., Goralski E., Hertweck C., Stahl M., Schaberle T. F., Stehle T. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6525–6536. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02488a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucipto H., Wenzel S. C., Muller R. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:1581–1589. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresovic D., Schempp F., Cheikh-Ali Z., Bode H. B. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015;11:1412–1417. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.11.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Thompson B., Hammer P. E., Hill D. S., Stafford J., Torkewitz N., Gaffney T. D., Lam S. T., Molnar I., Ligon J. M. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:860–869. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.860-869.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Zhang F., Liu W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3993–4001. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucipto H., Sahner J. H., Prusov E., Wenzel S. C., Hartmann R. W., Koehnke J., Muller R. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:5076–5085. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01013f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S. W., Bozhuyuk K. A., Kresovic D., Grundmann F., Dill V., Brachmann A. O., Waterfield N. R., Bode H. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:4108–4112. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoner T. A., Kresovic D., Bode H. B. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:8323–8328. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Hahn F., Demydchuk Y., Chettle J., Tosin M., Osada H., Leadlay P. F. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:99–101. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi E. M., Krawczyk J. M., von Suchodoletz H., Schadt S., Muhlenweg A., Uguru G. C., Pelzer S., Fiedler H. P., Bibb M. J., Stach J. E., Sussmuth R. D. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1401–1410. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demydchuk Y., Sun Y., Hong H., Staunton J., Spencer J. B., Leadlay P. F. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1136–1145. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., White-Phillip J. A., Melancon, 3rd C. E., Kwon H. J., Yu W. L., Liu H. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14670–14683. doi: 10.1021/ja0744854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X. Y., Tian Z. H., Shao L., Qu X. D., Zhao Q. F., Tang J., Tang G. L., Liu W. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Hong H., Gillies F., Spencer J. B., Leadlay P. F. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:150–156. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura E., Tomita T., Sawa R., Nishiyama M., Kuzuyama T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:11265–11270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000532107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inahashi Y., Shiraishi T., Palm K., Takahashi Y., Omura S., Kuzuyama T., Nakashima T. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1442–1447. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens L. B., Kim W., Wang P., Zhou H., Watanabe K., Gomi S., Tang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17677–17689. doi: 10.1021/ja907852c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callari R., Fischer D., Heider H., Weber N. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018;17:72. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0925-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider T., Zocher G., Unger M., Scherlach K., Stehle T., Hertweck C. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;8:154–161. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Roongsawang N., Shirasaka N., Lu W., Flatt P. M., Kasanah N., Miranda C., Mahmud T. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2253–2265. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Roongsawang N., Mahmud T. Chem. Biol. 2011;18:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q. L., Jia X. Y., Tang M. C., Tian Z. H., Tang G. L., Liu W. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:813–819. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abugrain M. E., Brumsted C. J., Osborn A. R., Philmus B., Mahmud T. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:362–366. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b01043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abugrain M. E., Lu W., Li Y., Serrill J. D., Brumsted C. J., Osborn A. R., Alani A., Ishmael J. E., Kelly J. X., Mahmud T. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1585–1588. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Li S., Niu S., Ma L., Zhang G., Zhang H., Zhang G., Ju J., Zhang C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1092–1105. doi: 10.1021/ja109445q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Kahlich R., Kammerer B., Heide L., Li S. M. Microbiology. 2003;149:2183–2191. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitnauer G., Muhlenweg A., Trefzer A., Hoffmeister D., Sussmuth R. D., Jung G., Welzel K., Vente A., Girreser U., Bechthold A. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:569–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosted T. J., Wang T. X., Alexander D. C., Horan A. C. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;27:386–392. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlert J., Shepard E., Lomovskaya N., Zazopoulos E., Staffa A., Bachmann B. O., Huang K., Fonstein L., Czisny A., Whitwam R. E., Farnet C. M., Thorson J. S. Science. 2002;297:1173–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.1072105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum M., Peintner I., Linnenbrink A., Frerich A., Weber M., Paululat T., Bechthold A. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:1073–1083. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui Z., Ye M., Wang S., Fujikawa K., Akerele B., Aung M., Floss H. G., Zhang W., Yu T. W. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:1116–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv M., Zhao J., Deng Z., Yu Y. Chem. Biol. 2015;22:1313–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel K. H., Boeck L. D., Hoehn M. M., Jones N. D., Chaney M. O. J. Antibiot. 1984;37:441–445. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.