Abstract

Neuronal nicotinic receptors (nAChR) are known to control transmitter release in the CNS. Thus, this study was aimed at exploring the diversity and localization of nAChRs present in CA1 interneurons in rat hippocampal slices. The use of a U-tube as the agonist delivery system was critical for the reliable detection of nicotinic responses induced by brief exposure of the neurons to ACh or to the α7 nAChR-selective agonist choline. The present study demonstrated that CA1 interneurons, in addition to expressing functional α7 nAChRs, also express functional α4β2-like nAChRs and that activation of both receptors facilitates an action potential-dependent release of GABA. Depending on the experimental condition, one of the following nicotinic responses was recorded from the interneurons by means of the patch-clamp technique: a nicotinic whole-cell current, depolarization accompanied by action potentials, or GABA-mediated postsynaptic currents (PSCs). Responses mediated by α7 nAChRs were short-lasting, whereas those mediated by α4β2 nAChRs were long-lasting. Thus, phasic or tonic inhibition of CA1 interneurons may be achieved by selective activation of α7 or α4β2 nAChRs, respectively. It can also be suggested that synaptic levels of choline generated by hydrolysis of ACh in vivo may be sufficient to control the activity of the α7 nAChRs. The finding that methyllycaconitine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (antagonists of α7 and α4β2 nAChRs, respectively) increased the frequency and amplitude of GABAergic PSCs suggests that there is an intrinsic cholinergic activity that sustains a basal level of nAChR activity in these interneurons.

Keywords: hippocampus, GABA, choline, methyllycaconitine, α-bungarotoxin, dihydro-β-erythroidine

In many areas of the brain, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) regulate the mechanisms of neurotransmitter release (Léna et al., 1993; McMahon et al., 1994; McGehee et al., 1995; Alkondon et al., 1996; Gray et al., 1996;Guo et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998). In general terms, modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic nAChRs (i.e., nAChRs present in synaptic terminals) is insensitive to blockade by the Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX), whereas modulation of transmitter release by nAChRs located in preterminal sites or in somatodendritic areas of presynaptic neurons depends on propagation of action potentials and is, therefore, sensitive to TTX (for review, see Wonnacott, 1997). Identifying the nAChR subtypes modulating the release of a neurotransmitter has been an important, albeit strenuous, task for the understanding of their function.

The study, showing that cultured hippocampal neurons respond to nicotinic agonists with at least one of three types of whole-cell currents, namely type IA, type II, and type III currents (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 1993), introduced a set of criteria that allows for the characterization of the nAChR subtypes subserving a given response. Briefly stated, α7-containing nAChRs mediate fast-desensitizing responses sensitive to blockade by α-bungarotoxin (α-BGT) or methyllycaconitine (MLA), whereas α4β2 and α3β4 nAChRs subserve slowly desensitizing responses sensitive to blockade by dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) and mecamylamine, respectively (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 1991, 1993; Alkondon et al., 1992, 1994;Zorumski et al., 1992; Castro and Albuquerque, 1993, 1995). The original classification of the nicotinic responses recorded from cultured hippocampal neurons has been recently expanded (Zoli et al., 1998).

Although nAChR subtype-selective antagonists have been helpful in assigning a receptor subtype to a nicotinic response, the discovery that choline modulates the function and expression of α7 nAChRs introduced a key pharmacological tool to distinguish these from other nAChR subtypes (Papke et al., 1996; Albuquerque et al., 1997; Alkondon et al., 1997b). In cultured hippocampal neurons, choline fully activates α7 nAChR-mediated type IA currents with an apparent EC50 of 1.6 mm, does not evoke α4β2 nAChR-mediated type II currents, and induces α3β4 nAChR-mediated type III currents with 20% of the apparent efficacy of acetylcholine (ACh). Also, when continuously applied to these neurons, choline, like other nicotinic agonists, desensitizes the α7 nAChRs with an apparent IC50 of 37 μm (Alkondon et al., 1997b). Therefore, choline as a nicotinic agonist has the unique capability of providing substantial clues regarding the nAChR subtype subserving a nicotinic response.

Initial studies showed that activation of nAChRs in CA1 interneurons results in different responses, including facilitation of GABA release (Alkondon et al., 1997a). Thus, the objective of the present work was to identify the subtypes of functional nAChRs that subserve the nicotinic responses in CA1 interneurons and to determine the location of these receptors. Using the patch-clamp technique and a number of nAChR subtype-selective pharmacological tools, particularly choline, we demonstrate that functional α7 and α4β2 nAChRs are present in CA1 interneurons and that activation of these nAChRs facilitates the action potential-dependent release of GABA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hippocampal slices. Slices of 250–300 μm thickness were obtained from the hippocampus of 15- to 30-d-old Sprague Dawley rats according to the procedure described earlier (Alkondon et al., 1997a). Animal care and handling were done strictly in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Animal Care Committee of University of Maryland at Baltimore. Slices were stored at room temperature in artificial CSF (ACSF), which was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and had the following composition (in mm): NaCl, 125; NaHCO3, 25; KCl, 2.5; NaH2PO4, 1.25; CaCl2, 2, MgCl2, 1; and glucose, 25. Neurons in the CA1 field of the slices were visualized by means of infrared-assisted videomicroscopy (Alkondon et al., 1997a). In some experiments, 0.4% Lucifer yellow was included in the pipette solution, and the fluorescence image of the dye-filled neurons was captured by a color chilled 3CCD camera (Alkondon et al., 1997a), allowing morphological confirmation of the interneurons. In the present study, we evaluated the effects of nAChR activation in CA1 interneurons located in the stratum radiatum, stratum lacunosum moleculare, and in between the two strata.

Electrophysiological recordings. Whole-cell currents were recorded from the soma of CA1 interneurons according to the standard patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981), using an LM-EPC7 patch-clamp system (List Electronic, Darmstadt, Germany). The signals were filtered at 2 kHz and either recorded on a video tape recorder for later analysis or directly sampled by a microcomputer using the pClamp6 program (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The neurons were superfused with ACSF at 2 ml/min. Atropine (1 μm) was added to the ACSF to block the muscarinic receptors. Nicotinic whole-cell currents were recorded from neurons continuously perfused with TTX (0.5 μm)-containing ACSF. Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary (1.2 mm outer diameter), and when filled with the internal solution, had resistances between 2 and 6 MΩ. The series resistance ranged from 7.7 to 20 MΩ. At −68 mV, the leak current was generally between 50 and 150 pA, and when it exceeded 200 pA, the data were not included in the analysis. For most of the voltage-clamp recordings, the internal solution consisted of (in mm): EGTA 10; HEPES, 10; Cs-methane sulfonate 130; CsCl 10; MgCl2, 2; and lidocaine N-ethyl bromide (QX-314), 5, pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH; 340 mOsm. A few voltage-clamp recordings were obtained with an internal solution that had the following composition (in mm): EGTA, 10; HEPES, 10; CsCl, 80; and CsF, 80, pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH; 340 mOsm. Current-clamp recordings were obtained with an internal solution that consisted of (in mm): EGTA, 10; HEPES, 10; K-gluconate, 130; and KCl, 20, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. The membrane potentials were corrected for the liquid junction potentials. All recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22°C).

Data analysis. The peak amplitude, delay in onset, 10–90% rise time, and decay time constant of nicotinic whole-cell currents were determined using the pClamp6 program. The steady-state current was measured as the difference between the baseline and the current remaining at the end of a 6 sec pulse. The delay in onset of the nicotinic currents was defined as the time between the stimulus artifact (time at which the valve was closed for agonist ejection) and time at which 10% of the peak amplitude was reached. GABAergic PSCs were analyzed using the continuous data recording (CDR) program (Dempster, 1989) and the pClamp6 program. The delay in the onset for agonist-evoked PSCs was defined as time between stimulus artifact and the time to reach the peak of the first PSC in a series of PSCs evoked by the agonist. We omitted from this analysis experiments in which the agonist-evoked PSC could not be discriminated from a spontaneous PSC. The peak amplitude, rise time, and decay time constants of the PSCs were analyzed using the CDR program. Results are presented as mean ± SE and were compared for their statistical significance by either paired or unpaired Student’s t test.

Agonist and antagonist application. Antagonists were applied via bath superfusion. A modified U-tube was used to deliver the agonists to a large field of neurons (Alkondon et al., 1997a). The tip of the modified U-tube had a diameter between 100 and 160 μm, and the lower rim of the U-tube tip was placed close to the neuron under study almost touching the slice. The hydrodynamics of the U-tube tended to slow down the onset and the rising phase of the agonist-elicited currents. For example, a 50 msec pressure application of choline (10 mm) or ACh (1 mm) via a single pipette (tip diameter, <1 μm) to the soma of CA1 interneurons induced currents with a rising phase 10- to 20-fold faster than that of currents induced by U-tube application of the same agonists to the interneurons (see Fig. 1A and Table 1). Furthermore, the delay for the onset of currents elicited by pressure application of the agonists was ∼6- to 10-fold shorter than that for the onset of currents evoked by U-tube application of the agonists. With pressure application, a delay of 57 ± 6 msec (n = 6), and with U-tube, a delay of 487 ± 25 msec (n = 50) was observed. In U-tube experiments, no difference was observed between ACh and choline in the delay time to record nicotinic currents. The U-tube had numerous advantages over the pressure-ejection system. First, and of utmost importance, leakage of agonist from the U-tube is much more unlikely than from a single pipette. This is a crucial point for studying the activity of receptors such as the α7 nAChRs, which desensitize rapidly after exposure to the agonist. Even the smallest leakage can prevent detection of responses mediated by such receptors. Second, the amount of agonist delivered via the U-tube is sufficient to displace the physiological solution bathing the neurons under study, so that the agonist concentration surrounding the neurons should be constant during the agonist pulse. In such cases, measurements of the decay time constants of currents elicited by sufficiently long agonist pulses delivered via the U-tube can provide useful information about the kinetics of receptor inactivation and desensitization. Third, with the U-tube it is possible to test various concentrations of different agonists in a single neuron, and, therefore, it is feasible to analyze more reliably concentration–response relationships. Fourth, agonists delivered via the pressure-ejection system reach a restricted area of the surface of the cell soma, whereas those delivered via the U-tube reach the entire cell soma and dendrites. Finally, considering that a large area of the neurons can be rapidly exposed to the agonists delivered via the U-tube, it becomes possible to assess the effect of activation of nAChRs in various areas of presynaptic neurons that synapse onto the neuron from which recordings are obtained.

Fig. 1.

Choline and ACh produce distinct responses in CA1 interneurons. A, Nicotinic currents evoked by pressure application via a single pipette of choline or ACh (50 msec pulse, 10 pSi) to the soma of two interneurons. Horizontal bar on the top (or bottom) of the traces represents the duration of agonist pulse. Vertical barin the beginning of each trace represents the stimulus artifact arising from the activation of the drug delivery system. Membrane potential was held at −68 mV in all voltage-clamp recordings unless otherwise stated. B–E, Responses of four interneurons to U-tube application of choline and ACh for 6 sec.B, Agonist-induced responses show only marginal difference in kinetics. C, The ACh-evoked current decayed much slower than the choline-induced current. D, In a current-clamped interneuron, both agonists induced similar depolarization and bursts of action potentials. E, In another current-clamped neuron, ACh induced responses that were more intense and lasted longer than those evoked by choline. The resting membrane potential of the neurons in D andE fluctuated around −69 mV. Atropine (1 μm) was present in the ACSF in all the experiments. TTX (0.5 μm) was present in the ACSF (inA–C) while recording the nicotinic currents in all the experiments. In most of the experiments under voltage clamp, QX-314 (5 mm) was present in the pipette solution. CNQX (10 μm) and bicuculline (10 μm) were present in the ACSF during current-clamp recordings. Calibration scale shown in B is applicable to all traces inA–C, however, the vertical calibration for the ACh trace in A is 25 pA. The calibration scale in D is also applicable to the traces inE.

Table 1.

Characteristics of nicotinic currents evoked in interneurons by application of agonists

| Parameter | Choline (mean ± SE) | ACh (mean ± SE) | Number of neurons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure application | |||

| Peak amplitude (pA) | 95 ± 28 | 80 ± 11.1 | 6 |

| Rise time (msec) | 26 ± 2.5 | 43 ± 2.6 | 6 |

| U-tube application | |||

| Peak amplitude (pA) (type IA currents) | 124 ± 10.9 | 107 ± 9.3 | 46 |

| Peak amplitude (pA) (type IB currents) | 71 ± 11.2 | 113 ± 15.7 | 29 |

| Steady-state current (pA) (type IB currents) | 86 ± 11.4 | 29 | |

| Rise time (msec) (type IA currents) | 549 ± 30 | 596 ± 43 | 25 |

| Rise time (msec) (type IB currents) | 570 ± 34 | 679 ± 37 | 10 |

| Decay time constant (msec) (type IA currents) | 827 ± 61 | 1002 ± 78 | 25 |

| Decay time constant (msec) (type IB currents) | 1038 ± 235 | 4351 ± 756 | 9 |

Holding potential = −68 mV.

In most experiments, the neurons were successively exposed to one of two natural agonists: the α7 nAChR-selective agonist choline and the nonselective agonist ACh, which activates all known nAChRs. The results obtained from this protocol indicated, without further pharmacological tests, whether a given neuron expressed only an α7 nAChR or an α7 and a non-α7 nAChR.

Drugs and toxins used. ACh chloride, (−)bicuculline methiodide, choline chloride, tetrodotoxin, GABA, QX-314, and atropine sulfate were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). CNQX was obtained from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). α-BGT was purchased from Biotoxins Inc. (St. Cloud, FL). MLA citrate was a gift from Professor M. H. Benn (Department of Chemistry, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Dihydro-β-erythroidine.HBr was a gift from Merck, Sharp & Dohme (Rahway, NJ). Stock solutions of all drugs were made in distilled water.

RESULTS

Functional α7 and α4β2 nAChRs are present in CA1 interneurons

In the presence of TTX, application of ACh (1 mm) via a U-tube to voltage-clamped CA1 interneurons in the stratum radiatum, in the stratum lacunosum moleculare, and in the border of the two strata resulted in the activation of two types of whole-cell currents (Fig. 1). One was a fast-decaying, type IA-like current that could also be evoked by choline (10 mm), and the other was a slowly decaying current that could not be evoked by choline (Fig. 1). Choline evoked type IA-like currents in all 75 interneurons studied, whereas ACh evoked similar responses in only 46 of the 75 neurons. In the remaining 29 interneurons, currents evoked by ACh retained a steady-state component of ∼76% of the peak amplitude. These currents had a slightly larger peak amplitude and a fourfold slower decay time constant than those elicited by choline in the same neuron (Fig. 1C; Table 1). Although the slowly decaying current elicited by ACh appeared similar in waveform to type II current recorded from hippocampal neurons in culture (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 1993; Alkondon et al., 1994), it conformed to the definition of a type IB current in that it included a hidden fast-decaying component that was revealed when the α7 nAChR-selective agonist choline was also tested in the same interneuron (Fig.1C).

In current-clamped interneurons, choline and ACh caused sufficient depolarization to trigger action potentials (Fig.1D,E). In all current-clamped neurons (n = 25), choline induced a brief depolarization accompanied by a short-lasting burst of action potentials (Fig. 1D), whereas in ∼40% of these interneurons ACh evoked a prolonged depolarization accompanied by a long-lasting burst of action potentials (Fig.1E).

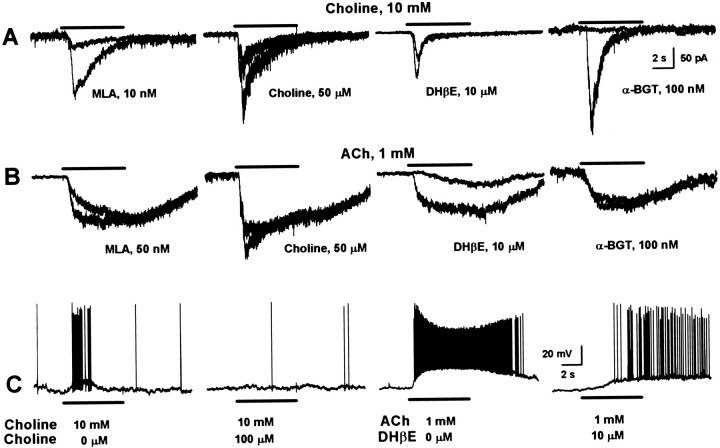

The use of nAChR subtype-selective antagonists led to the identification of the functional nAChR subtypes present in CA1 interneurons in slices. Superfusion of the hippocampal slices for 3–10 min with desensitizing concentrations of choline (25– 100 μm) or with the α7 nAChR-selective antagonist MLA (10–50 nm) or α-BGT (100 nm) inhibited both type IA-like whole-cell currents and the brief depolarization accompanied by short-lasting bursts of action potentials evoked by either ACh or choline (Fig.2A,C; Table 2). The blocking effect of bath-applied choline was fully reversed within 5–10 min, and that of MLA was reversed partly within 10–15 min of perfusion of the slices with ACSF. In contrast, the effect of α-BGT persisted for >1 hr, the maximum period up to which the reversal was monitored. Neither choline nor ACh elicited type IA-like currents in CA1 interneurons in slices (n = 6) that had been preincubated for 1–3 hr with α-BGT (100 nm). These results support the concept that α7 nAChRs underlie the short-lasting responses evoked by ACh or choline in CA1 interneurons.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological agents identify different nicotinic responses. A, Fast-decaying nicotinic currents elicited by choline in four interneurons under control condition (the largest response in each) and after 5–10 min exposure to different inhibitory agents (the smallest response in each). B, Slowly decaying nicotinic currents elicited by ACh in four interneurons under control condition (the largest response in each) and after 5–10 min exposure to different inhibitory agents (the smallest response in each). C, Choline-induced responses in a current-clamped interneuron before (first trace) and after 5 min continuous exposure to choline (100 μm) (second trace). ACh-induced responses in another current-clamped interneuron before (first trace) and after 5 min continuous exposure to DHβE (fourth trace).

Table 2.

Inhibition of nicotinic currents by different pharmacological agents

| Agent | Peak current amplitude % Inhibition (mean ± SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type IA (peak) | n | Type IB (steady-state) | n | |

| MLA (10 nm) | 74.2 ± 2.3 | 6 | ||

| MLA (50 nm) | 100 | 6 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 4 |

| Choline (25 μm) | 34.2 ± 3.2 | 4 | ||

| Choline (50 μm) | 58.0 ± 4.8 | 5 | ||

| Choline (100 μm) | 97.8 ± 1.1 | 6 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | 5 |

| α-BGT (100 nm) | 100 | 6 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | 4 |

| DHβE (10 μm) | 39.2 ± 3.9 | 4 | 87.2 ± 4.6 | 5 |

Steady-state current was measured as the difference between the baseline and the current at the end of a 6 sec agonist pulse. The amplitudes of the currents recorded in the presence of each antagonist were significantly (p < 0.05 according to the paired Student’s t test) different from those measured in the absence of the antagonists.

MLA (50 nm), choline (100 μm), and α-BGT (100 nm) were only effective in inhibiting partly the initial peak of ACh-evoked type IB-like responses and had no effect on the steady-state component of these currents (Fig.2B; Table 2). In contrast, 3–5 min superfusion of the neurons with DHβE (10 μm) reduced by ∼85% the amplitude of ACh-induced type IB currents and the amplitude of the depolarization as well as the frequency of action potentials triggered by application of ACh to current-clamped interneurons (Fig.2B,C). These results suggested that the long-lasting responses induced by ACh are mediated by a putative nAChR containing α4β2 subunits (hereafter referred to as α4β2 nAChR, although the exact subunit composition remains to be determined). At the concentration tested, DHβE did not recognize exclusively α4β2 nAChRs, given that it reduced by ∼40% the amplitude of type IA-like currents evoked by either choline (Fig.2A; Table 2) or ACh. However, the antagonistic effect of DHβE on type IA currents reversed in <10 min wash, whereas it took 15–20 min to get full recovery of type IB currents after washing of the neurons with ACSF.

Both ACh and choline induced a concentration-dependent increase in the peak amplitude of type IA currents (Fig.3A,B,F). The lowest effective concentrations of ACh and choline were 30 and 200 μm, respectively. Fitting of the results by the Hill equation indicated an EC50 and a Hill coefficient of 225 μm and 2.1, respectively, for ACh and 2.27 mmand 1.45, respectively, for choline. According to the fit, the maximum achievable response for the two agonists was nearly the same, indicating that the efficacy of choline as an agonist is nearly the same as that of ACh.

Fig. 3.

Nicotinic currents rectify inwardly and show differences in sensitivity to activation by agonists. A, Fast-decaying currents (type IA) evoked by different concentrations of ACh in an interneuron. B, Type IA currents induced by different concentrations of choline in another neuron.C, In the same interneuron as in B, a 20 sec pulse of choline (0.5 mm) also elicited a current. The decay phase of this current was fit by a single exponential function (fit represented by solid line through the data) with a decay time constant of 4.2 sec. D, Graph shows the plot of the peak amplitude versus membrane potential for choline- and ACh-evoked type IA currents; the data were obtained from two neurons each. Inset shows the current traces evoked by choline in a single experiment. At positive membrane potentials, no outward nicotinic currents were evoked, although the spontaneous GABAergic PSCs were present. In all experiments, the pipette solution contained methane sulfonate as the main anion and MgCl2.E, Slowly decaying currents (type IB) evoked by various concentrations of ACh in another interneuron. F, Concentration–response relationship for ACh and choline in inducing different responses. The amplitude of the currents evoked by the highest agonist concentration tested was taken as 100% and used to normalize the amplitude of the currents evoked by the other concentrations. Data points are the average from two neurons for choline and ACh in type IA and from one neuron in type IB. Solid lines passing through data points represent the fit of the data to a Hill equation. For type IB, two EC50s and two Hill coefficients were assumed. G, Graph shows the plot of the peak amplitude versus membrane potential of ACh-evoked type IB currents from a single interneuron. Inset shows the current traces at different membrane potentials.

Assuming that micromolar concentrations of choline may be generated by the hydrolysis of endogenously released ACh and that choline remains longer than ACh near synapses, we examined whether α7 nAChRs could be activated by several-second exposure to low concentrations of choline. As illustrated in Figure 3C, a 20 sec pulse of choline (500 μm) induced a current that decayed with a time constant of 4.2 sec, which is roughly five times slower than that of currents induced by 1 mm ACh. Thus, concentrations of choline between 200 and 500 μm will be able to maintain the activation of α7 nAChRs for at least 10–20 sec before receptor desensitization.

Slowly decaying currents similar to type IB currents could be evoked by an ACh concentration as low as 10 μm (Fig.3E). The concentration–response curve provided two EC50s for ACh: 25.7 and 325 μm (Fig.3F), indicating that type IB currents in the interneurons arise from the simultaneous activation of a high-affinity (possibly the α4β2) and a low-affinity (possibly the α7) nAChR.

The amplitude of both type IA and IB currents increased linearly with increasing hyperpolarization of the membrane between −8 and −98 mV. When Mg2+ was present in the internal solution, the currents rectified inwardly such that no outward currents could be detected at membrane potentials between 0 and +50 mV (Fig.3D,G). The current–voltage relationship of choline-evoked currents could not be distinguished from that of ACh-evoked currents (Fig. 3D). Replacing the permeant anion chloride with the less permeant anion methane sulfonate in the internal solution caused a negative shift in the reversal potential of GABA-evoked currents (see Results), but did not affect that of the nicotinic currents. In addition, the estimated reversal potential of the nicotinic currents was ∼0 mV. Thus, both nAChR subtypes present on the interneurons are permeable to cations.

With the discovery that functional α7 and α4β2 nAChRs are present in CA1 interneurons and that activation of these receptors causes sufficient depolarization to trigger action potentials, we analyzed in detail the ability of nicotinic agonists to control the action potential-dependent release of GABA from these neurons.

Nicotinic receptor activation facilitates the action potential-dependent release of GABA from CA1 interneurons

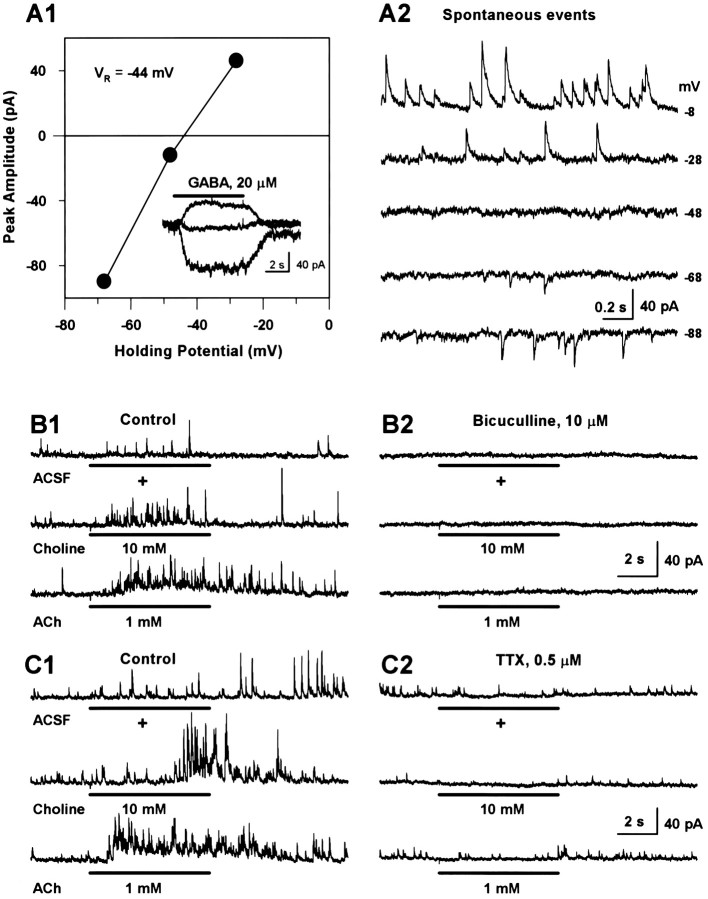

Interneurons in the CA1 field of the hippocampus are GABAergic in nature and establish synaptic connections with other interneurons in this region. Therefore, it is conceivable that activation of nAChRs in the interneurons can modulate the activity of other interneurons by affecting GABA release. To determine the effects of nicotinic agonists on GABA release, a methane sulfonate-based pipette solution was used. Under this experimental condition, currents mediated by activation of GABAA receptors had a null potential of −44 mV (Fig.4A1). Thus, recordings obtained from neurons held at +2 or −8 mV would have very little, if any, contribution of currents mediated by activation of nicotinic or glutamate receptors.

Fig. 4.

Nicotinic agonists trigger GABAergic PSCs in interneurons in an action potential-dependent manner.A1, Plot of the membrane potential versus peak amplitude of GABA-evoked currents. Data points are from the traces shown inA2, inset. Spontaneous PSCs recorded from another interneuron at different membrane potentials. Note that both spontaneous PSCs and GABA-evoked whole-cell currents reversed at approximately −44 mV. B, Recording of PSCs spontaneously occurring or evoked by nicotinic agonists in an interneuron at +2 mV. Traces on the left column(B1) were obtained under control condition, and those on the right (B2) were obtained 3–9 min after exposure of the neuron to bicuculline. C, Panel of traces showing spontaneous and agonist-evoked (6 sec pulse) PSCs under control (C1) and 3–7 min after exposure to TTX (C2). Data were obtained from a single interneuron at +2 mV. All experiments with PSCs were performed using a pipette solution that contained Cs-methanesulfonate as the main anion and QX-314 (5 mm).

During a 6 sec U-tube application of choline (10 mm) or ACh (1 mm) to the CA1 interneurons voltage clamped at −8 or +2 mV, the number of PSCs was much higher than that recorded before the exposure of the neurons to the agonists (Fig.4B1,C1). Superfusion of hippocampal slices with bicuculline (10 μm) inhibited spontaneously occurring and agonist-induced PSCs (Fig. 4B2), confirming that these events were mediated via GABAAreceptors. Superfusion of the slices with TTX (0.5 μm) also decreased the frequency of spontaneously occurring PSCs from 1.595 ± 0.337 Hz to 0.944 ± 0.387 Hz, and in the presence of TTX, choline and ACh were unable to increase the frequency of PSCs (Fig. 4C2; Table 3). Thus, the nAChRs subserving these nicotinic responses were present in preterminal sites and/or in the soma of interneurons synapsing onto the neurons from which recordings were obtained, and activation of those receptors by the agonists facilitated the action potential-dependent release of GABA.

Table 3.

Analysis of the frequency of GABAergic PSCs under different conditions

| Experimental condition | Number of PSCs per sec (mean ± SE) |

|---|---|

| Absence of TTX | |

| Control | 1.451 ± 0.263 |

| Choline (1 mm) | 2.524 ± 0.1523-a |

| Control | 1.451 ± 0.263 |

| Choline (10 mm) | 2.636 ± 0.1653-a |

| Control | 1.388 ± 0.393 |

| ACh (0.1 mm) | 2.152 ± 0.3603-a |

| Control | 1.388 ± 0.393 |

| ACh (1 mm) | 3.138 ± 0.3423-a |

| Presence of TTX3-b | |

| Control | 1.331 ± 0.345 |

| Choline (10 mm) | 1.196 ± 0.409 |

| Control | 1.331 ± 0.345 |

| ACh (1 mm) | 1.432 ± 0.436 |

p < 0.01, compared to respective control by paired t test; n = 5 in all groups.

Slices were continuously perfused with TTX (0.5 μm)-containing ACSF.

Agonists were applied via the U-tube to the CA1 interneurons for 6–12 sec.

nAChR activation in CA1 interneurons induces short- or long-lasting bursts of PSCs

GABAergic PSCs set the inhibitory tone in the CNS, and, consequently, mediate major functions such as adjusting the firing threshold of a neuron or altering Ca2+ dynamics in the neurons (Miles et al., 1996). Therefore, it would be of interest to know the duration of the period in which GABAergic PSCs can be induced by nAChR activation, because the cholinergic afferents are known to innervate the interneurons (Frotscher and Léránth, 1985).

Application of choline and ACh to the CA1 interneurons resulted, respectively, in short- and long-lasting bursts of PSCs (Fig.5A,B). Whereas the effect of choline declined during a 12 sec agonist pulse, that of ACh outlasted the agonist pulse (Fig.5A,B). The effects of both agonists on GABA release were concentration-dependent (Fig.5A,B). With increasing concentrations of choline there was a shortening of the delay for detecting the PSCs, and with increasing concentrations of ACh there was also an increase in the frequency of PSCs (Table 3). In the experiments shown in Figure 5, A and B, the delay in the onset of PSCs evoked by 1 and 10 mm choline was 1884 and 965 msec, respectively, and the delay in onset of PSCs evoked by 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mm ACh was 880, 505, and 264 msec, respectively. The average delay in the onset of agonist-evoked PSCs calculated from nine experiments was 1422 ± 393 msec for 10 mmcholine and 690 ± 76 msec for 1 mm ACh. The shorter delay for the onset of the ACh response suggested that the nAChRs activated by ACh are located in close proximity to the interneuron under study, whereas the nAChRs activated by choline, in many instances, are located distally to the recorded neuron. It is likely that applied choline activated nAChRs present in the soma and dendrites of nearby interneurons, whereas applied ACh activated predominantly nAChRs present in preterminal regions of presynaptic interneurons.

Fig. 5.

the PSC frequency that outlasted the duration of the agonist pulse, particularly at the highest concentrations of ACh (third and fourth traces).C, Traces shown in A were expanded for better visualization of the PSCs. Under control (first two traces), individual PSCs are well (Figure legend continues)separated. With choline (10 mm), the PSCs summated such that individual events could not be identified (third trace). In the presence of ACh (10 μm), individual PSCs could still be identified. However, in the presence of 100 μm and 1 mm ACh, the PSCs summated such that the frequency could not be analyzed.D, An example of an experiment in which charge analysis of the PSCs was performed. Traces shown in B were used for this analysis. Charge movement per 2 sec segment was calculated in the traces before, during, and after the end of pulse and plotted against time. The 10th sec in the time scale corresponds to activation of the agonist-delivery system. Membrane potential, +2 mV.Choline and ACh differ in their ability to trigger GABAergic PSCs. A, A 6 sec pulse of choline induced a burst of PSCs that did not outlast the agonist pulse (top trace). Note that the evoked PSCs were preceded by a small inward current that was induced by choline. In the same neuron, application of ACh induced a concentration-dependent increase in the PSC frequency (second, third, andfourth traces). The PSCs outlasted the ACh pulse. Membrane potential, −8 mV. B, In another neuron, a 12 sec pulse of choline (1 mm) also induced a burst of PSCs. The delay for the onset of the response was shortened by increasing the concentration of choline to 10 mm. In the same neuron, ACh induced a concentration-dependent increase in

Agonist-mediated PSCs were analyzed according to one of two methods. When the PSCs did not summate and could be detected as isolated events, parameters such as frequency (Table 3), amplitude, rise time, and decay time constant of the PSCs were analyzed. In many instances, however, particularly at ACh concentrations ≥ 0.1 mm, the PSCs summated and could not be detected as individual events (Fig.5A, traces; Fig. 5C, expanded traces). In such cases, quantification of the effects of the nicotinic agonists was made possible by the charge analysis (Fig.5D).

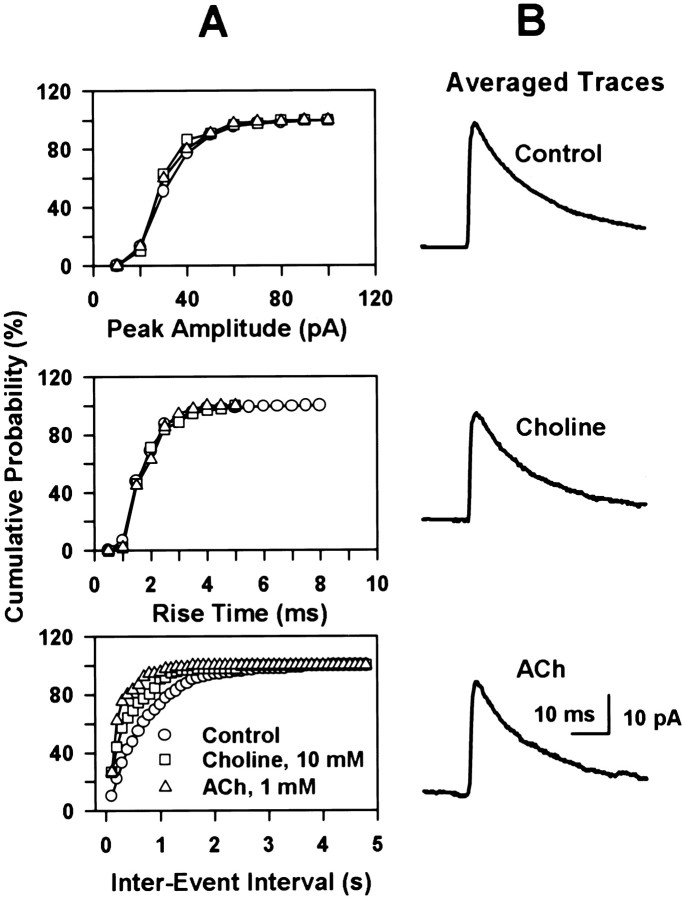

Analysis of individual PSCs indicated that both choline (10 mm) and ACh (1 mm) did not change the distribution of the peak amplitudes or rise times of these events; the mode amplitude was 24.8 pA, and the mode rise time was 1.24 msec, regardless of whether the PSCs were recorded in the absence or in the presence of ACh (1 mm) or choline (10 mm). It should be noticed that although in most cells (n = 10) the agonists did not alter the amplitude distribution of the PSCs, in three neurons large-amplitude events were detected in higher frequency when the interneurons were exposed to the nicotinic agonists than under control condition. In contrast, the frequency of PSCs was always higher, as revealed by shortening of the interevent interval, when the interneurons were exposed to choline or ACh than under control condition. Fitting the interevent intervals to a single-exponential function indicated that under control condition this function decayed with a time constant of 786 msec, a value that is longer than the time constant obtained from the single-exponential fittings of the intervals between choline- or ACh-induced PSCs (i.e., 420 and 266 msec, respectively). Cumulative probability distributions of peak amplitude, rise time, and interevent intervals for PSCs recorded under control condition and during exposure of the interneurons to ACh or choline clearly show the specific effect of the nicotinic agonists on the PSC frequency (Fig. 6A). Although ACh caused no change in the decay time constant of the averaged PSCs, choline slightly accelerated the decay phase of the PSCs (Fig. 6B). The decay time constant of the averaged PSCs in control, choline, and ACh were 16.51, 14.47, and 16.02 msec, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Nicotinic agonists increase the frequency of PSCs. Analysis of the peak amplitude, 10–90% rise time, and interevent intervals of PSCs that occurred either spontaneously (270 sec data) or in response to choline (40 sec data, two pulses applied) and ACh (20 sec data, one pulse applied) in a CA1 interneuron. Data were from the same experiment as illustrated in Figure 5B.A, Cumulative distribution of peak amplitude, rise time, and interevent intervals of events recorded under different experimental conditions. This representation clearly shows that nicotinic agonists increased the frequency but not other parameters of the PSCs. B, Several PSCs were averaged: 304 spontaneous events, 81 events recorded in the presence of choline, and 57 events recorded in the presence of ACh. These averaged traces show very little differences in their decay phase.

Short-lasting PSC bursts are induced by activation of α7 nAChRs, whereas long-lasting PSC bursts are induced by activation of α4β2 nAChRs in CA1 interneurons

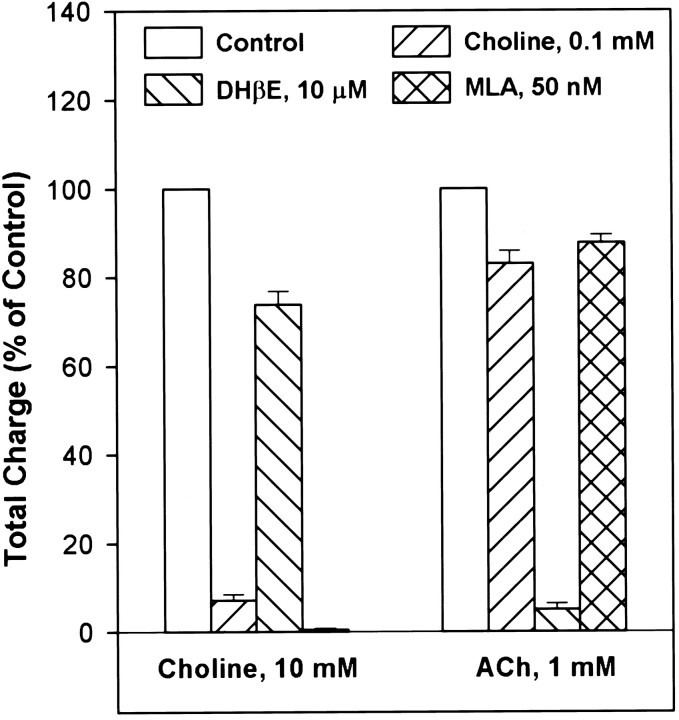

Superfusion of the hippocampal slices for 3 min with choline (100 μm) prevented brief pulses of choline (10 mm) from inducing PSCs. This blocking effect of choline was completely reversed after washing. In contrast, even longer (6 min) exposure of the interneurons to choline (100 μm) had negligible effect on ACh-induced (1 mm) long-lasting bursts of PSCs. Superfusion of the slices with DHβE (10 μm) for 6 min caused a slight decrease in the choline-induced PSCs, whereas after 3 min exposure of the interneurons to DHβE, the ability of ACh to induce PSCs was blocked by ∼85%. After a 10–13 min washing of the interneurons with DHβE-free ACSF, the ability of choline to evoke PSCs was completely restored, whereas that of ACh was only partly recovered. Finally, 3 min superfusion of the slices with MLA (50 nm) completely inhibited choline-induced (10 mm) PSCs but produced negligible inhibition of ACh-evoked PSCs. Partial reversal from MLA-induced blockade occurred after 15 min wash. The blocking effect of different agents on the agonist-induced PSCs were analyzed by calculating the charge movements in the presence and in the absence of the blockers (Fig.7). It was also observed in five different slices pretreated with α-BGT (100 nm) for 1–3 hr that choline failed to induce any PSCs, whereas ACh evoked a typical long-lasting burst of PSCs. Thus, the present results provide evidence that α7 nAChRs underlie the choline-induced short-lasting burst of PSCs, and α4β2 nAChRs underlie the ACh-induced long-lasting burst of PSCs in the interneurons.

Fig. 7.

Pharmacological agents identify the nAChR subtypes that trigger PSCs. Agonist-evoked PSCs under different conditions were quantitated using charge analysis. The values obtained before perfusion of the neurons with the antagonists were taken as 100%. The data are mean ± SE calculated from three experiments. The values in the antagonist group were significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.02 according to the Student’st test). Note that the bar representing choline-induced PSCs in the presence of MLA is not visible because of a complete blocking effect.

Long-lasting bursts of PSCs elicited by activation of α4β2 nAChRs could be recorded from all 25 interneurons studied in the absence of TTX (i.e., a 100% incidence). In contrast, whereas α7 nAChR-mediated type IA-like currents were recorded from all interneurons studied in the presence of TTX, α4β2 nAChR-mediated nicotinic currents were observed in ∼65, 32, and 36% of the interneurons sampled in the stratum lacunosum moleculare (n = 17), in the stratum radiatum (n = 50), and in the border of the two strata (n = 33), respectively. The mismatch between the number of neurons responding to ACh with α4β2 nAChR-mediated currents and with α4β2 nAChR-induced facilitation of GABA release can be explained on the basis that the first response arises from activation of receptors present on the soma and proximal dendrites of the interneurons from which recordings were obtained, whereas the second response was triggered by activation of nAChRs present in other interneurons and on preterminal sites as well.

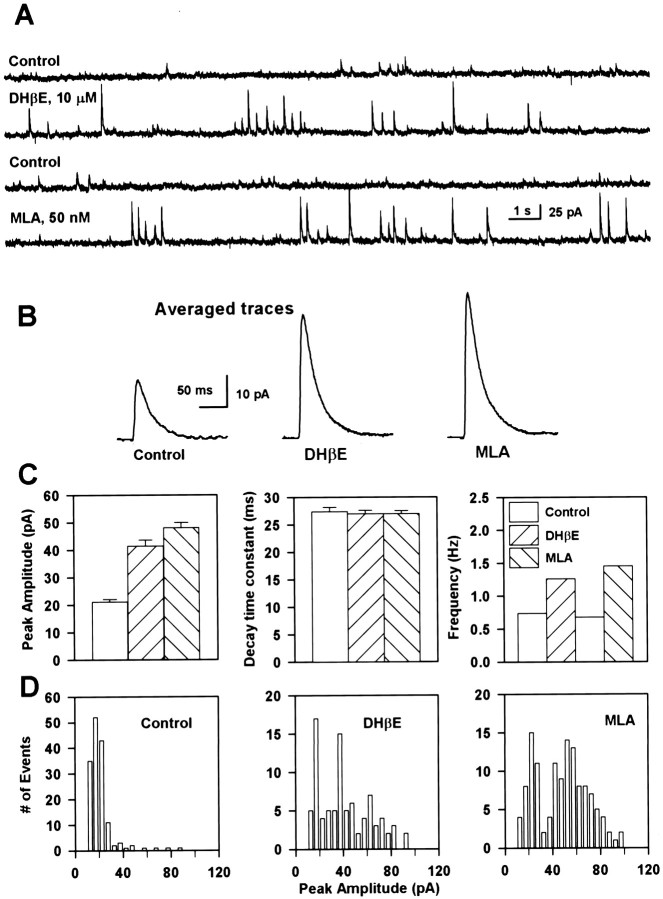

Basal α7 and α4β2 nAChR activity controls the excitability of CA1 interneurons in hippocampal slices

Superfusion of the slices with either DHβE (10 μm) or MLA (50 nm) caused an increase in the peak amplitude as well as in the frequency of PSCs recorded from CA1 interneurons (Fig.8A,B). In the example shown in Figure 8A, these effects were observed within 20–30 sec after start of the superfusion and lasted for ∼3 min, after which time the amplitude and the frequency of the PSCs returned to their control values. In a few interneurons (n = 3), the effects of MLA and DHβE on the PSC frequency and amplitude lasted for <1 min. Neither MLA nor DHβE altered the decay time constant of the PSCs, indicating a presynaptic action of these agents. In the presence of TTX, MLA and DHβE failed to increase the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous PSCs (n = 2). These results suggested that the nAChRs present in the interneurons are constantly subjected to the action of the endogenous transmitter or transmitters and that this activity maintains a basal inhibitory tone in the neurocircuitry in the CA1 field of the hippocampus.

Fig. 8.

Nicotinic antagonists increase the frequency of large-amplitude PSCs. A, PSCs recorded at −8 mV from an interneuron before and 1 min after exposure to each of the antagonists. During exposure to these agents, large-amplitude events appeared frequently, and this effect reversed after wash. B, The averaged PSC traces obtained from several individual PSCs in each group indicated marked changes in the PSC amplitude. C, The arithmetic mean and SE of the peak amplitudes (left graph) and decay time constants (middle graph) of PSCs are shown for each group. The number of PSCs (both small- and large-amplitude events) per second before and during exposure of the neurons to the antagonists was calculated and is depicted in theright graph. D, Distribution of the peak amplitude of PSCs recorded for 450 sec in the absence of antagonists, for 150 sec in the presence of DHβE, and for 150 sec in the presence of MLA. Note that large-amplitude events are more prevalent in the presence than in the absence of the antagonists.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates for the first time that CA1 interneurons in hippocampal slices exhibit two kinetically and pharmacologically distinct nicotinic currents in response to exogenously applied agonists, a finding that is consistent with the existence of two functional subtypes of nAChRs in these neurons. One nAChR subtype contains the α7 subunit and mediates fast excitation of the interneurons, as shown in previous studies (Alkondon et al., 1997a;Jones and Yakel, 1997; Frazier et al., 1998a), and the other contains most likely α4β2 subunits and mediates slow excitation in the interneurons. Also of major impact was the finding that activation of α7 or α4β2 nAChRs facilitates the action potential-dependent release of GABA from CA1 interneurons, indicating these nACh R subtypes can be assigned to presynaptic neurons.

The time course of the agonist-induced PSCs suggested that α7 nAChRs are best suited for mediating phasic inhibition in the interneurons, whereas the α4β2 nAChRs are likely to mediate tonic inhibition in these neurons. The finding that nicotinic antagonists enhanced the amplitude and frequency of GABAergic PSCs also indicates that ACh released from cholinergic fibers maintains a basal level of nAChR activity that sustains the inhibition of the GABAergic system in the CA1 field of the hippocampus.

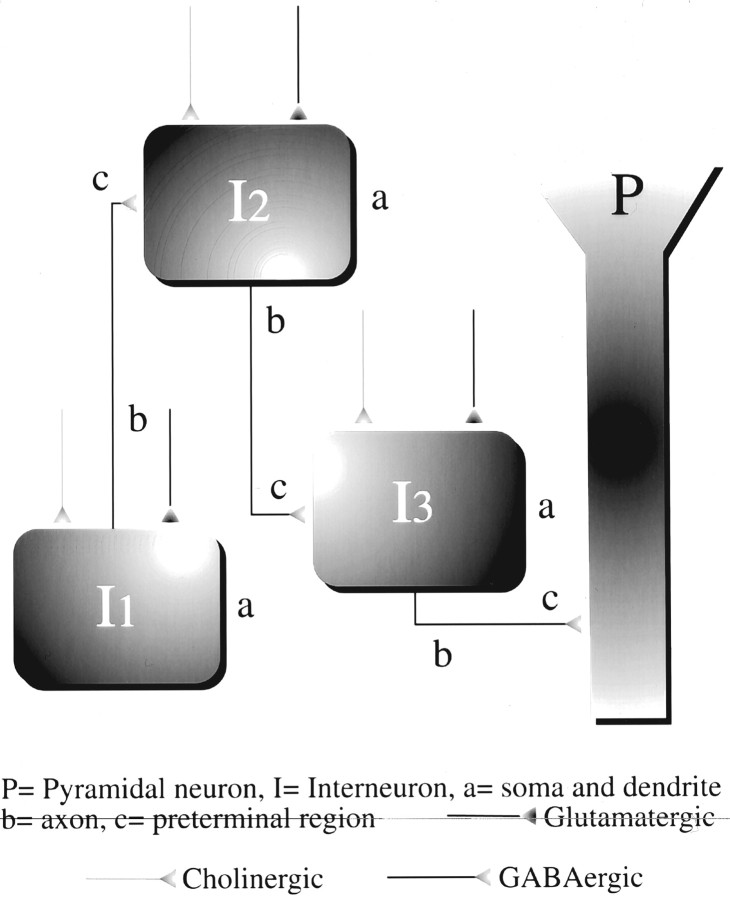

The ability of TTX to attenuate choline- and ACh-induced facilitation of GABA release suggested that the nAChRs subserving such effects are present in somatodendritic regions (Fig.9, site a) and in preterminal sites (Fig. 9, site c) of axons (Fig. 9, site b) of interneurons that synapse onto the interneuron under study. The longer delay to induce PSCs with choline than with ACh supports the contention that choline-evoked PSCs originated from activation of α7 nAChRs located in somatodendritic regions of interneurons that synapse onto the neuron under study and that ACh-evoked PSCs could have arisen from activation of α4β2 nAChRs located in preterminal sites (Lu et al., 1998) of presynaptic interneurons. Further analyses are underway to delineate the location of the nAChRs that are critical for mediating GABA release after activation by the agonists and to determine whether nAChRs could also be present in the presynaptic terminal of GABAergic interneurons and control the action potential-independent release of GABA.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of an interneuron circuitry in the CA1 region that can be affected by nicotinic cholinergic activity. This scheme is based on the anatomical evidence that is reported in the literature and on the functional evidence that is presented in this study. For simplicity, we have shown three interneurons (I1–I3) and one pyramidal neuron (P) connected in series. The present results and those of our previous study (Alkondon et al., 1997a) suggest that nAChRs are located in preterminal sites (c) of axons (b) and in somatodendritic regions of CA1 interneurons. Endogenous nicotinic cholinergic activity can induce either inhibition or disinhibition depending on the interneuron that is activated in the circuitry. A properly timed cholinergic signal to one interneuron (e.g.,I1) can effectively nullify the ability of a glutamatergic signal to drive a second interneuron (e.g.,I2), resulting in the disinhibition of a synaptically connected neuron (e.g., I3). The ability of nicotinic antagonists to increase the frequency of GABAergic PSCs in the interneurons supports such a scheme.

Diversity of nAChRs in the CA1 interneurons

The present results indicate that at least one of two nAChR subtypes (i.e., an α7 and/or an α4β2) are present in CA1 interneurons in hippocampal slices taken from rats at early stages of development (15- to 20-d-old) and from mature (21- to 30-d-old) rats. The properties of the nAChR subtypes in CA1 interneurons are remarkably similar to those of the receptor subtypes present in cultured neurons (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 1993; Alkondon et al., 1994). For example, type IA currents in both preparations exhibited fast kinetics of inactivation during a short agonist pulse, showed very similar sensitivity to activation by agonists, and had similar sensitivity to desensitizing concentrations of choline. Also, type IB currents in both preparations showed a higher sensitivity to ACh than type IA currents. These similarities suggested that fetal hippocampal neurons in culture retain an intrinsic ability to express functional nAChRs even in the absence of the major septal cholinergic afferents that innervate the hippocampus. However, striking differences in the sensitivity of the receptor subtypes to the reversible competitive antagonists MLA and DHβE were seen; 50–100 times larger concentrations of these agents were necessary to block the nicotinic currents recorded from neurons in slices than to block the same responses in the neurons in culture. Although the access barrier in slices can interfere with the determination of antagonist sensitivity of the responses, it could not account for the magnitude of difference noted in the slice neurons. These findings suggest that there may be age-related changes in the affinity of the receptors for competitive antagonists. Alternatively, this discrepancy could be attributed to changes in the receptor composition that may occur as a consequence of the cholinergic innervation of the hippocampal neurons.

Depending on the nAChR subtype activated there can be a short- or a long-lasting excitation of CA1 interneurons

The kinetics of inactivation of both α7 and α4β2 nAChRs have a direct correlation with the ability of these receptors to control the activity of the CA1 interneurons. Activation of α7 nAChRs by short pulses of the nicotinic agonists choline and ACh resulted in phasic, whereas activation of α4β2 nAChRs by ACh resulted in tonic excitation of these interneurons. The recent demonstration of an α7 nAChR-mediated fast synaptic transmission in the CA1 interneurons (Alkondon et al., 1998; Frazier et al., 1998b) is consistent with the concept that synaptically released ACh could trigger a phasic pattern of action potentials in these neurons. At this point, it is unclear whether α4β2 nAChRs can also mediate synaptic transmission in CA1 interneurons. However, the higher sensitivity of α4β2 nAChRs to ACh is compatible with those being activated in a nonsynaptic manner by diffusing agonist. The low incidence (∼7%) of cholinergic axon varicosities opposing synaptic specializations in CA1 neurons (Umbriaco et al., 1995) and the low incidence (10–20%) of detecting a fast nicotinic synaptic transmission in CA1 interneurons (Alkondon et al., 1998; Frazier et al., 1998b) support the notion of volume transmission mediated by diffusing ACh acting through α4β2 nAChRs (Léna and Changeux, 1997; Wonnacott, 1997).

Nicotinic receptor activation can result in inhibition or disinhibition of neurons in the CA1 field of the hippocampus

Nicotinic receptor activation in interneurons that synapse directly onto pyramidal neurons is likely to inhibit the activity of the latter (Fig. 9). However, activation of nAChRs in interneurons that innervate other interneurons would cause disinhibition of the pyramidal neurons (Fig. 9). In fact, the connectivity between interneurons and other interneurons or pyramidal neurons has been well described (Acsády et al., 1996; Gulyás et al., 1996; Hájos and Mody, 1997). Disinhibition of CA3 pyramidal neuron activity by stimulation of septal GABAergic afferents has been demonstrated, and the importance of such disinhibitory mechanisms to the functions of the hippocampus has been stressed (Hawkins et al., 1993; Tóth et al., 1997). The present results indicating that GABAergic PSCs can be induced in the interneurons by nAChR activation and that GABAergic PSCs could be enhanced in amplitude and frequency by nicotinic antagonists support the existence of a disinhibitory circuit in the CA1 region that could be controlled by nicotinic cholinergic activation. Thus, the results provided in this study give direct experimental support to previous studies in which a GABAergic mechanism was suspected to explain the relationship between α7 nAChR gene locus and attentional deficits in schizophrenia (Freedman et al., 1997) and that between cholinergic deafferentation and kindling epileptogenesis (Kokaia et al., 1996).

Endogenous choline may control the α7 nAChR activity

Similar to the findings obtained from cultured hippocampal neurons (Alkondon et al., 1997b), the present results reveal that choline interacts selectively with α7 nAChRs, being unable to either activate or desensitize α4β2 nAChRs. This provides a mechanism by which selective activation and inactivation of α7 nAChRs can be achieved. Such selectivity cannot be attained with the primary neurotransmitter ACh, which activates all known subtypes of nAChRs.

The concentrations of choline in the CSF range from 4 to 12 μm (Klein et al., 1992). Thus, circulating choline is unlikely to cause either activation or inactivation of α7 nAChRs. It is unknown whether choline can be released from the cholinergic terminals and serve as the neurotransmitter at α7 nAChR-bearing synapses in the CNS. However, choline can be generated at high micromolar concentrations near cholinergic synapses by the hydrolysis of ACh by AChE, and its concentration may fluctuate depending on the frequency of activation of cholinergic fibers. Thus, the following effects can be predicted from the synaptically generated choline. First, it can activate the somatodendritic α7 nAChRs and alter Ca2+ dynamics in the interneurons. Second, choline can activate or inactivate α7 nAChRs and either facilitate or inhibit the release of GABA from α7 nAChR-bearing neurons. It should be noted that an earlier study, in which agonists were applied by pressure ejection to CA1 interneurons via a single pipette, failed to detect an agonist effect of low concentrations of choline (Frazier et al., 1998a). The use of the U-tube in the present study was of paramount importance for the detection of the agonist effect of choline at low concentrations, because it minimized agonist-leak-induced desensitization, thus allowing reliable detection of nicotinic responses induced by successive pulses of different agonists or of a given agonist at different concentrations. Thus, the possibility that choline generated at cholinergic synapses is able to activate extrasynaptic α7 nAChRs (Frazier et al., 1998a) cannot be ruled out. Finally, the ability of choline to desensitize α7 nAChRs can serve as a rate-limiting step in the α7 nAChR-mediated postsynaptic transmission.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that CA1 interneurons, in addition to expressing functional α7 nAChRs, also express α4β2-like nAChRs and that activation of each of these receptors facilitates the action potential-dependent release of GABA. The nAChRs present in the interneurons remain the target sites for the action of ACh and, possibly, choline as neurotransmitters and are intimately involved in the control of neuronal excitability in the CA1 field of the hippocampus.

Footnotes

This study was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants NS 25296 and ES 05730, and PRONEX (from Brazil). The superb technical assistance of Ms. Mabel Zelle, Ms. Barbara Marrow, and Mr. Benjamin Cumming is gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Dr. S. Wonnacott for her helpful comments on this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Edson X. Albuquerque, Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 655 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, MD 21201.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acsády L, Görcs TJ, Freund TF. Different populations of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive interneurons are specialized to control pyramidal cells or interneurons in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1996;73:317–334. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albuquerque EX, Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Castro NG, Schrattenholz A, Barbosa CTF, Bonfante-Cabarcas R, Aracava Y, Eisenberg HM, Maelicke A. Properties of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Pharmacological characterization and modulation of synaptic function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1117–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Initial characterization of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. J Recept Res. 1991;11:1001–1022. doi: 10.3109/10799899109064693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1455–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Wonnacott S, Albuquerque EX. Blockade of nicotinic currents in hippocampal neurons defines methyllycaconitine as a potent and specific receptor antagonist. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:802–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkondon M, Reinhardt S, Lobron C, Hermsen B, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. II. The rundown and inward rectification of agonist-elicited whole-cell currents and identification of receptor subunits by in situ hybridization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:494–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkondon M, Rocha ES, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat brain. V. α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors in olfactory bulb neurons and presynaptic modulation of glutamate release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:1460–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Barbosa CTF, Albuquerque EX. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation modulates γ-aminobutyric acid release from CA1 neurons of rat hippocampal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997a;283:1396–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Cortes WS, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Choline is a selective agonist of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat brain neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1997b;9:2734–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkondon M, Pereira EFR, Albuquerque EX. α-Bungarotoxin- and methyllycaconitine-sensitive nicotinic receptors mediate synaptic transmission in interneurons of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 1998;810:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro NG, Albuquerque EX. Brief-lifetime, fast-inactivating ion channels account for the α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic response in hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1993;164:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90876-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro NG, Albuquerque EX. α-Bungarotoxin-sensitive hippocampal nicotinic receptor channel has a high calcium permeability. Biophys J. 1995;68:516–524. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempster J. Computer analysis of electrophysiological signals. In: Frazer PJ, editor. Microcomputers in physiology: a practical approach. IRI; Oxford: 1989. pp. 51–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazier CJ, Rollins YD, Breese CR, Leonard S, Freedman R, Dunwiddie TV. Acetylcholine activates an α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic current in rat hippocampal interneurons, but not pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1998a;18:1187–1195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01187.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frazier CJ, Buhler AV, Weiner JL, Dunwiddie TV. Synaptic potentials mediated via α-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:8228–8235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08228.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman R, Coon H, Myles-Worsley M, Orr-Urtreger A, Olincy A, Davis A, Polymeropoulos M, Holik J, Hopkins J, Hoff M, Rosenthal J, Waldo MC, Reimherr F, Wender P, Yaw J, Young DA, Breese CR, Adams C, Patterson D, Adler LE, Kruglyak L, Leonard S, Byerler W. Linkage of neurophysiological deficit in schizophrenia to a chromosome 15 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:587–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frotscher M, Léránth C. Cholinergic innervation of the rat hippocampus as revealed by choline acetyltransferase immunocytochemistry: combined light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1985;239:237–246. doi: 10.1002/cne.902390210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature. 1996;383:713–716. doi: 10.1038/383713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulyás AI, Hájos N, Freund TF. Interneurons containing calretinin are specialized to control other interneurons in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3397–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J-Z, Tredway TL, Chiappinelli VA. Glutamate and GABA release are enhanced by different subtypes of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1963–1969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hájos N, Mody I. Synaptic communication among hippocampal interneurons: properties of spontaneous IPSCs in morphologically identified cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8427–8442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08427.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp technique for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA. Learning to modulate transmitter release: themes and variations in synaptic function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:625–665. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones S, Yakel JL. Functional nicotinic ACh receptors on interneurons in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;504:603–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.603bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein J, Koppen A, Loffelholz K, Schmitthenner J. Uptake and metabolism of choline by rat brain after acute choline administration. J Neurochem. 1992;58:870–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kokaia M, Ferencz I, Leanza G, Elmér E, Metsis M, Kokaia Z, Wiley RG, Lindval O. Immunolesioning of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons facilitates hippocampal kindling and perturbs neurotrophin messenger RNA regulation. Neuroscience. 1996;70:313–327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Léna C, Changeux JP. Role of Ca2+ ions in nicotinic facilitation of GABA release in mouse thalamus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:576–585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00576.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Léna C, Changeux JP, Mulle C. Evidence for “preterminal” nicotinic receptors on GABAergic axons in the rat interpeduncular nucleus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2680–2688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Rainnie DG, McCarley RW, Greene RW. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors facilitate monoaminergic transmission. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1904–1912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01904.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Y, Grady S, Marks KJ, Picciotto M, Changeux JP, Collins AC. Pharmacological characterization of nicotinic receptor-stimulated GABA release from mouse brain synaptosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:648–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGehee DS, Heath MJS, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotinic enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon LL, Yoon KW, Chiappinelli VA. Nicotinic receptor activation facilitates GABAergic neurotransmission in the avian lateral spiriform nucleus. Neuroscience. 1994;59:689–698. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miles R, Tóth K, Gulyás AI, Hájos N, Freund TF. Differences between somatic and dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:815–823. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papke RL, Bencheriff M, Lippiello P. An evaluation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation by quaternary nitrogen compounds indicates that choline is selective for the α7 subtype. Neurosci Lett. 1996;213:201–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tóth K, Freund TF, Miles R. Disinhibition of rat hippocampal pyramidal cells by GABAergic afferents from the septum. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;500:463–474. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umbriaco D, Garcia S, Beaulieu C, Descarries L. Relational features of acetylcholine, noradrenaline, serotonin and GABA axon terminals in the stratum radiatum of adult rat hippocampus (CA1). Hippocampus. 1995;5:605–620. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wonnacott S. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zoli M, Léna C, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP. Identification of four classes of brain nicotinic receptors using beta2 mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4461–4472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04461.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zorumski CF, Thio LL, Isenberg KE, Clifford DB. Nicotinic acetylcholine currents in cultured postnatal rat hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:931–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]