Abstract

We describe a novel mechanism by which network oscillations can arise from reciprocal inhibitory connections between two entirely passive neurons. The model was inspired by the activation of the gastric mill rhythm in the crab stomatogastric ganglion by the modulatory commissural ganglion neuron 1 (MCN1), but it is studied here in general terms. One model neuron has a linear current–voltage (I–V) curve with a low (L) resting potential, and the second model neuron has a linear current–voltage curve with a high (H) resting potential. The inhibitory connections between them are graded. There is an extrinsic modulatory excitatory input to the L neuron, and the L neuron presynaptically inhibits the modulatory neuron. Activation of the extrinsic modulatory neuron elicits stable network oscillations in which the L and H neurons are active in alternation. The oscillations arise because the graded reciprocal synapses create the equivalent of a negative-slope conductance region in theI–V curves for the cells. Geometrical methods are used to analyze the properties of and the mechanism underlying these network oscillations.

Keywords: neural oscillators; central pattern generators; crustaceans; coupled oscillators; phase plane analysis, mathematical model

The mechanisms by which reciprocal inhibition among neurons give rise to network oscillations have been studied extensively both experimentally and theoretically (Marder and Calabrese, 1996; Stein et al., 1997). This network module has long been thought to be critical in the generation of rhythmic motor patterns (Brown, 1914; Perkel and Mulloney, 1974; Miller and Selverston, 1982a,b; Satterlie, 1985; Friesen, 1994; Calabrese, 1995). In some cases, the reciprocally inhibitory connections are thought to occur between neurons that are nearly identical, as in bilateral circuits that subserve left–right alternation (Arbas and Calabrese, 1987). In other cases, reciprocally inhibitory connections occur between functional antagonists such as flexors and extensors (Brown, 1914;Pearson and Ramirez, 1990) or other kinds of nonidentical neurons (Miller and Selverston, 1982b).

There has been a significant amount of theoretical work on half-center oscillators in which the neurons are essentially identical and the connections symmetric (Perkel and Mulloney, 1974; Wang and Rinzel, 1992, 1993; Skinner et al., 1994; Van Vreeswijk et al., 1994; Nadim et al., 1995; Olsen et al., 1995; Sharp et al., 1996; Rowat and Selverston, 1997). In the cases studied, the component neurons had some intrinsic excitability, either because they were themselves oscillatory or had properties such as post-inhibitory rebound that were important in the production of the oscillation. In this paper we demonstrate that two reciprocally inhibitory, entirely passive and nonidentical neurons can produce stable network oscillations, provided that the synaptic connections between them are graded, and that they receive an asymmetric extrinsic drive. This work is an outcome of our interest in providing a heuristic simplification and mathematical understanding of a recent detailed compartmental model (Nadim et al., 1998) of the activation of the gastric mill rhythm of the crab Cancer borealis by the modulatory commissural neuron 1 (MCN1).

At the center of the MCN1-activated gastric mill rhythm (Coleman et al., 1995) are two neurons: the lateral gastric (LG) neuron and interneuron 1 (Int1). These two neurons reciprocally inhibit each other. In the absence of MCN1 stimulation, the LG neuron is not active but maintains a relatively hyperpolarized membrane potential, whereas Int1 is spontaneously active. MCN1 provides a slow, modulatory, excitatory drive to the LG neuron, which helps to depolarize it to threshold. When LG fires, it inhibits Int1, which then stops firing. The LG neuron also presynaptically inhibits the terminals of MCN1, so that when LG is active, the excitatory modulatory drive is removed until LG falls below its threshold, thus releasing both Int1 and the presynaptic terminals of MCN1 and completing the cycle. In this scenario, MCN1 plays the role of “balancing the asymmetry” of the half-center composed of the reciprocally coupled LG and Int1 neurons.

To understand better the operation of this circuit, Nadim et al. (1998)constructed a detailed compartmental model. This model suggested that the asymmetric half-center oscillation between LG and Int1 is controlled by the properties of both the slow modulatory excitation from MCN1 to LG and the fast rhythmic inhibition from anterior burster (AB) to Int1 (Marder et al., 1998; Nadim et al., 1998). The model used in Nadim et al. (1998) is 60-dimensional, with each neuron having several compartments. It provided significant new insights into the role of a fast oscillator in controlling the period of a slower network oscillator (Nadim et al., 1998) and gave rise to a series of experiments that essentially confirmed the major findings of the detailed model (Marder et al., 1999; M. Bartos, Y. Manor, F. Nadim, E. Marder, M. Nusbaum, unpublished observations). In this paper we show that the key features of the detailed model are captured in a three-dimensional model that allows mathematical analysis of the mechanisms that give rise to the slow oscillations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

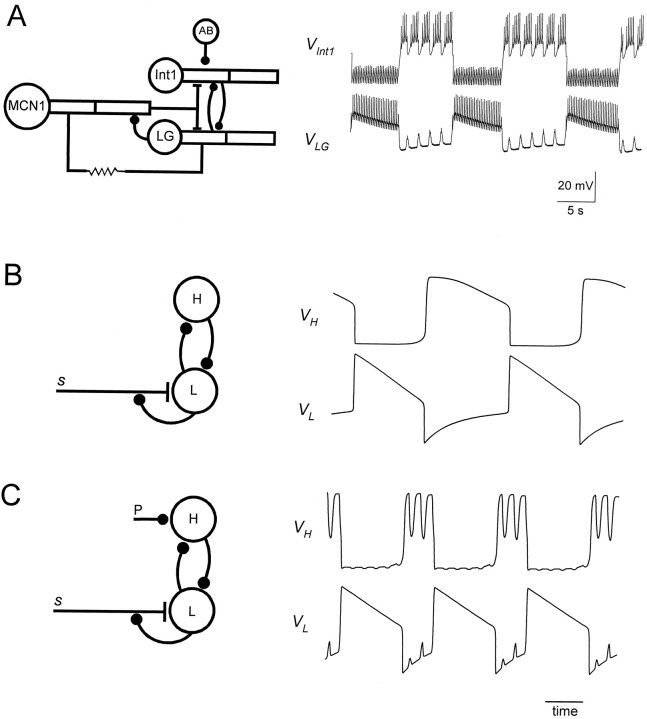

In this paper we describe a reduced version of the LG/Int1/MCN1 network that retains the essential features of the compartmental model of Nadim et al. (1998). These features include the reciprocally inhibitory connections of LG and Int1, the MCN1 excitation of LG, the LG presynaptic inhibition of MCN1, and the AB inhibition of Int1. Figure 1A shows a detailed schematic circuit of the compartmental model, together with voltage traces of LG and Int1 during a gastric mill rhythm.

Fig. 1.

Simplifying a compartmental model of the MCN1-elicited gastric mill rhythm. A, Schematic representation showing the compartmental model (left) and voltage traces of the model Int1 and the LG neuron when the model MCN1 is stimulated at 15 Hz. [Adapted from Nadim et al. (1998).])B, The circuit in A is simplified to a pair of passive neurons L and H connected via graded reciprocal inhibition. L has a low resting potential and H has a high resting potential. L receives a slow modulatory excitations that is presynaptically gated by L. Also shown are the voltage traces of L and H. C, Same circuit as inB, but with an additional periodic inhibition P (representing the AB neuron in A) to H.

To simplify the circuit, we model LG and Int1 as two passive neurons, one neuron with a low (L) resting membrane potential (−60 mV) and the other with high (H) resting membrane potential (+10 mV). The modulatory neuron provides a slow excitation (s) to L. This slow excitation is controlled by the membrane potential of L via presynaptic inhibition. This circuit and the resulting oscillation are shown in Figure 1B. The mechanism that we describe depends only on graded, not spike-mediated, synaptic transmission. Therefore we consider only the slow envelopes of the LG and Int1 oscillations shown in Figure 1A, not the fast spiking activity of these cells. The electrical coupling between MCN1 and LG that helps sustain the LG burst (Coleman et al., 1995) is ignored. In the reduced model presented in this paper, the LG burst duration is accounted for by the interaction between L and s. We also assume that the fast excitatory input from MCN1 to Int1 is not significant.

Our model is a three-dimensional dynamical system. The three variables are VL, the membrane potential of L,VH, the membrane potential of H, ands, the strength of the excitatory input to L. The effect of AB is added to the circuit as a periodic input (P), and the consequences are discussed. Figure 1C shows a schematic drawing of the circuit and the voltage traces when P is added.

Equations describing the reciprocally inhibitory pair. We first consider the subcircuit formed by L and H, leaving out the M excitation and the periodic input from P. The membrane potentials of L and H are given by first-order differential equations, each with a unique equilibrium point. For simplicity, the membrane capacitances of the two cells are set to 1. The equations of the coupled L/H circuit have the form:

| Equation 1 |

| Equation 2 |

The parameters of the reciprocally inhibitory synapses areEH→L and EL→H (the reversal potentials); H→L and L→H (the maximal conductances); andmH→L and mL→H (the gating functions). Because these synapses are relatively fast, we define mH→L and mL→Has instantaneous functions of the membrane potential:

| Equation 3 |

| Equation 4 |

These functions are plotted in Figure 2B,C. The functions fH(VH) and fL(VL) represent the intrinsic properties of H and L, respectively. We assume that the intrinsic dynamics of H and L are purely passive:

| Equation 5 |

where gleak,L,gleak,H,Eleak,L, andEleak,H are the conductances and reversal potentials of the leak currents in L and H, respectively. In the biological MCN1-elicited gastric mill circuit, without the slow excitation, L rests at a low potential whereas H fires tonically with a high baseline potential (Coleman et al., 1995). We model this asymmetry by setting Eleak,L to a low value, e.g., −60 mV, and Eleak,H at a high value, e.g., +10 mV.

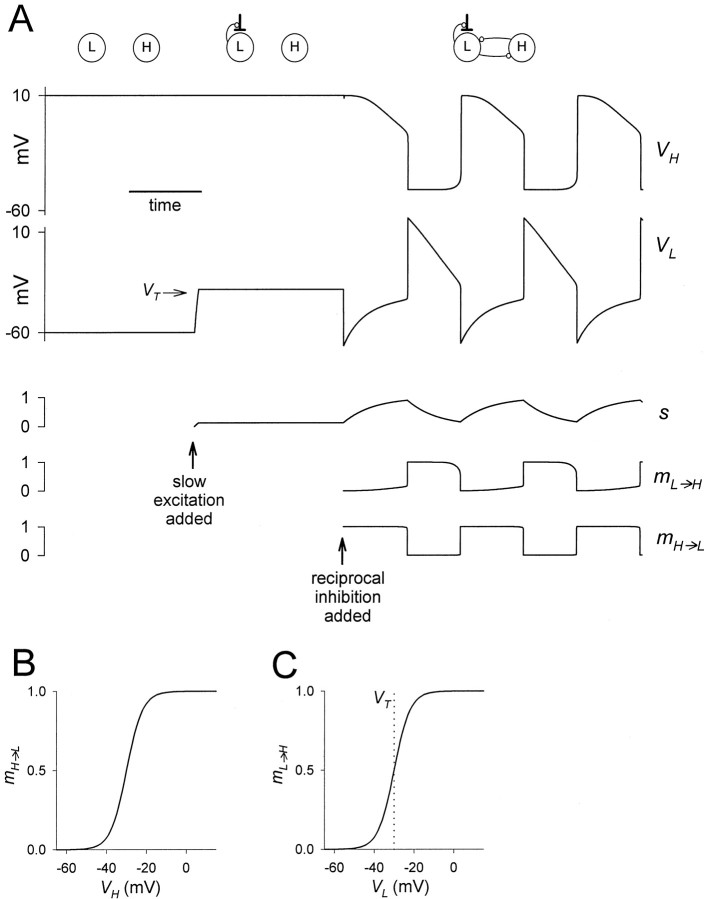

Fig. 2.

Slow modulatory excitation can balance an asymmetric half-center to produce oscillations. A, Thetop two traces are the voltages of the two cellsH and L. Also shown are the slow modulatory excitation s to L, the activation of the L to H inhibition mL→H, and the activation of the H to L inhibition mH→L. Thesetraces start on the left with the two cells isolated, and s is held at 0. At the time indicated by the first arrow, s is activated. At the time indicated by the second arrow, the reciprocal inhibitory synapses are activated. Shown in theVL trace is the threshold voltageVT for presynaptic inhibition ofs by L. B, The synaptic transfer function for the H to L inhibition. C, The synaptic transfer function for the L to H inhibition. The vertical dotted line shows the threshold voltage VTfor presynaptic inhibition of s by L.

Setting the right-hand side of Equation 1 to 0 and solving forVL, we obtain the following formula for the L nullcline:

| Equation 6 |

L is a sigmoidal function ofVH: when VH is low,mH→L(VH) is close to 0 and L saturates toEleak,L. When VH is large, mH→L(VH) is close to 1 and L saturates at an average between Eleak,L andEH→L, weighted by the respective leak and synaptic conductances. The slope between these two saturated portions of the nullcline is proportional to the degree of gradation of the H to L synapse. Setting the right-hand side of Equation 2 to 0 and solving for VH, we obtain the following formula for the H nullcline:

| Equation 7 |

NH is a sigmoidal function ofVL.

Adding the slow modulatory excitation. We now introduce the slow chemical excitation (s) of L. In our model, this excitation is completely controlled by the voltage of L: whenVL is above some thresholdVT, the excitation decays, and whenVL is below VT, the excitation grows. The slow excitation s is therefore governed by the following equation:

| Equation 8 |

where τr, τf > 0. WhenVL < VT,s builds up toward 1 with time constant τr. When VL > VT,s decays toward 0 with time constant τf. The excitation produces an additional term in Equation 1, so that now the network is described by Equations 2, 8, and:

| Equation 9 |

where s is the maximal conductance and Es is the reversal potential of the excitatory input. Setting the right-hand side of Equation 9 to 0 and solving for VL, we obtain a new formula for the L nullcline:

| Equation 10 |

Adding the fast input from P. When P is added to the circuit, the network is described by Equations 8, 9 and:

| Equation 11 |

where the conductance of the P to H synapsegP→H is a non-negative periodic function oft, and EP→H is the reversal potential of the P to H synapse. At the peak of the P input ( P→H), the H nullcline is given by the formula:

| Equation 12 |

We will sometimes use NH,NL, or ÑH to denote the graphs of the respective formulae in theVL–VH space.

The physiological interpretation of nullclines in theVL–VH phase plane.In the absence of periodic input P, and for a fixed value ofs, the VL–VHphase plane is used to describe the relationship between the membrane potentials of H and L at any time. The L and H nullclines are the sets of points in the phase plane where dVL/dt and dVH/dt, respectively, are zero. Another view, more intuitive to some physiologists, is that the H nullcline at any value of VL is whereVH would settle if L were voltage-clamped at that value of VL. When H is at a membrane potential higher than the H nullcline, VH decays toward NH. VH rises toward NH when H is at a membrane potential lower than the H nullcline. NH thus divides theVL–VH phase plane into two parts: above NH, where dVH/dt < 0, and belowNH, where dVH/dt > 0. Similarly, the L nullcline at any value of VH is whereVL would settle if H were voltage-clamped at that VH value. NL divides the VL–VH phase plane into two parts: to the left of NL, where dVL/dt > 0, and to the right of NL, where dVH/dt < 0.

The intersections of the two nullclines are equilibrium points at which both dVL/dt and dVH/dt are zero. An equilibrium point may be stable—after any local perturbation, the membrane potential of the perturbed cell will return toward the same equilibrium point; or the equilibrium point may be unstable—in this case, a small perturbation results in a large change in the membrane potential. In the phase plane, the stability of these equilibrium points can be determined by direction of the vectors (dVH/dt, dVL/dt) in the vicinity of that point. In some figures we show this vector field using small arrows.

By solving the differential equations for VH andVL we obtainVH(t) andVL(t). The trajectory in the VH–VL phase plane is obtained by plotting the (VH,VL) values for all times t. For fixed s, the nullclines NH andNL are fixed curves in theVH–VL plane. In the full system (given by Equations 2, 8, and 9), s changes slowly, producing a family of curves NL that change slowly (NH is independent of s). Thus, the intersections of these curves also change slowly in time, creating “quasi-static” equilibrium points.

Construction of the current–voltage curves of the reciprocally inhibitory pair. One can get additional information from the current–voltage (I–V) relationships of the neurons H and L. We first describe the derivation of theI–V curve for L. For simplicity, we consider the case without the fast periodic input. The total currentIL flowing into L is given by −dVL/dt. From Equation 9, this quantity depends on two fast variables, namely the membrane potentials of both cells, VL andVH. We view the slow variable s as a parameter. To construct the I–V curve of L, we must reduce the two-variable expression in Equation 9 to a single-variable function of VL. Because the reciprocal synaptic currents between H and L are relatively fast, we can assume, for each value ofVL and s, thatVH adjusts quickly to its steady state. At steady state, NH (the H nullcline) gives an expression for VH in terms ofVL (see Equation 7). In Equation 9, we can substitute NH for VH and obtain a term that depends on VL only:

The negative of the right-hand side of this expression givesIL as a function of VLand is used to plot the family of I–V curves of L, dependent on s. Using similar arguments, we can derive an expression for the family of I–V curves of H. In this case, we use Equation 10 instead of Equation 9.

All numerical simulations were performed with the software XPPAUT by B. Ermentrout (available at ftp://ftp.math.pitt.edu/pub/bardware).

Model parameters. The simulations for Figures1B, 2, 5, 7, and 8 were performed using the following parameter values: H→L = 5 mS/cm2, L→H = 2 mS/cm2, EH→L = −80 mV,EL→H = −80 mV, vH→L= −30 mV, vL→H = −30 mV,kH→L = 4 mV, kL→H = 4 mV, Eleak,L = −60 mV,Eleak,H = 10 mV, gleak,L= 1 mS/cm2, gleak,H = 0.75 mS/cm2, VT = −30 mV, s = 3 mS/cm2,Es = −30 mV, τr = τf = 4 sec. The simulations for Figures 1C and11 used the additional parameters P→H = 0.9 mS/cm2 and EP→H = −60 mV, and gP→H(t) is a half-sine function of t with period = 1 sec and duty-cycle = 0.5.

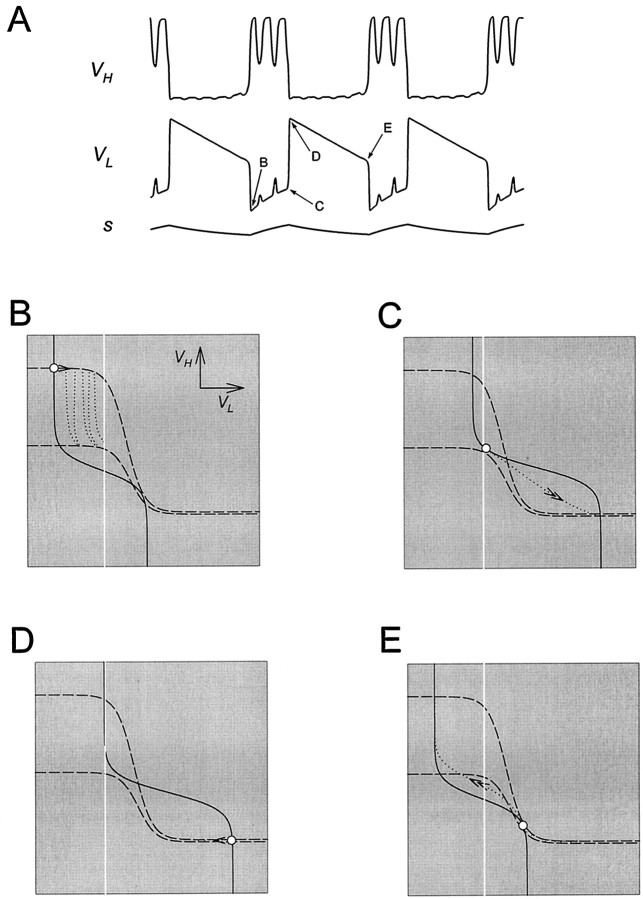

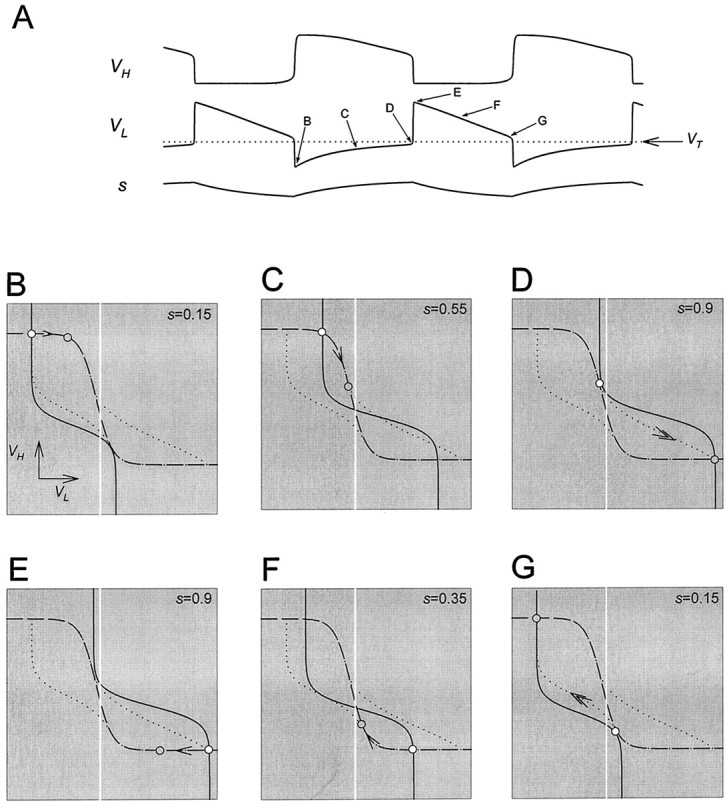

Fig. 5.

Analysis of one cycle of the oscillation using phase planes. A, Top, middle, andbottom traces show the voltage traces of H and L and the modulatory excitation s. The dotted linesuperimposed on the voltage trace of L is the thresholdVT for presynaptic inhibition of the excitatory input. B–G show theVL–VH phase plane at the six representative times marked in A. The corresponding values of s are marked in each panel. The intersection of the L nullcline (solid line) and H nullcline (dashed line) is the quasi-steady state (○) for the indicated value of s. In each panel, thearrow pointing toward the quasi-steady state of the next representative time (

) indicates the movement of the phase point along the trajectory (dotted line; same in B–G).Vertical white line indicates the thresholdVT.

) indicates the movement of the phase point along the trajectory (dotted line; same in B–G).Vertical white line indicates the thresholdVT.

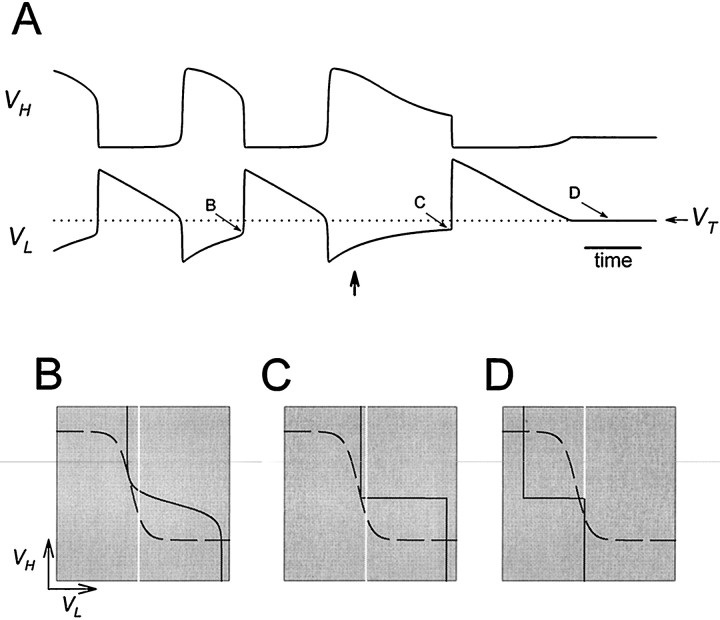

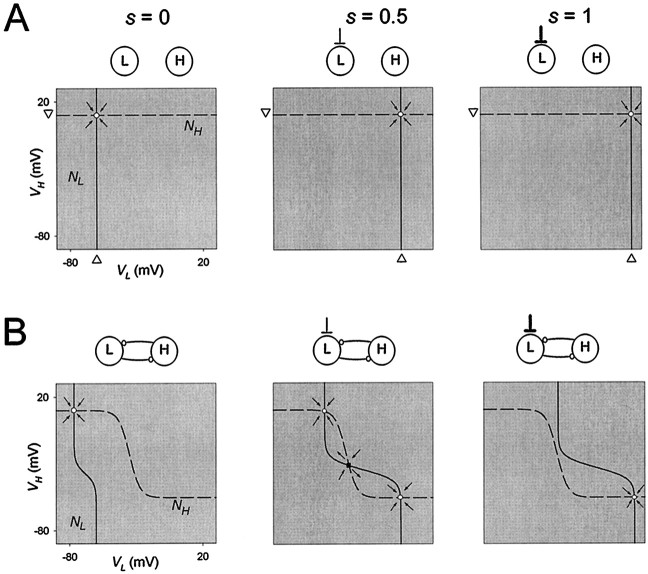

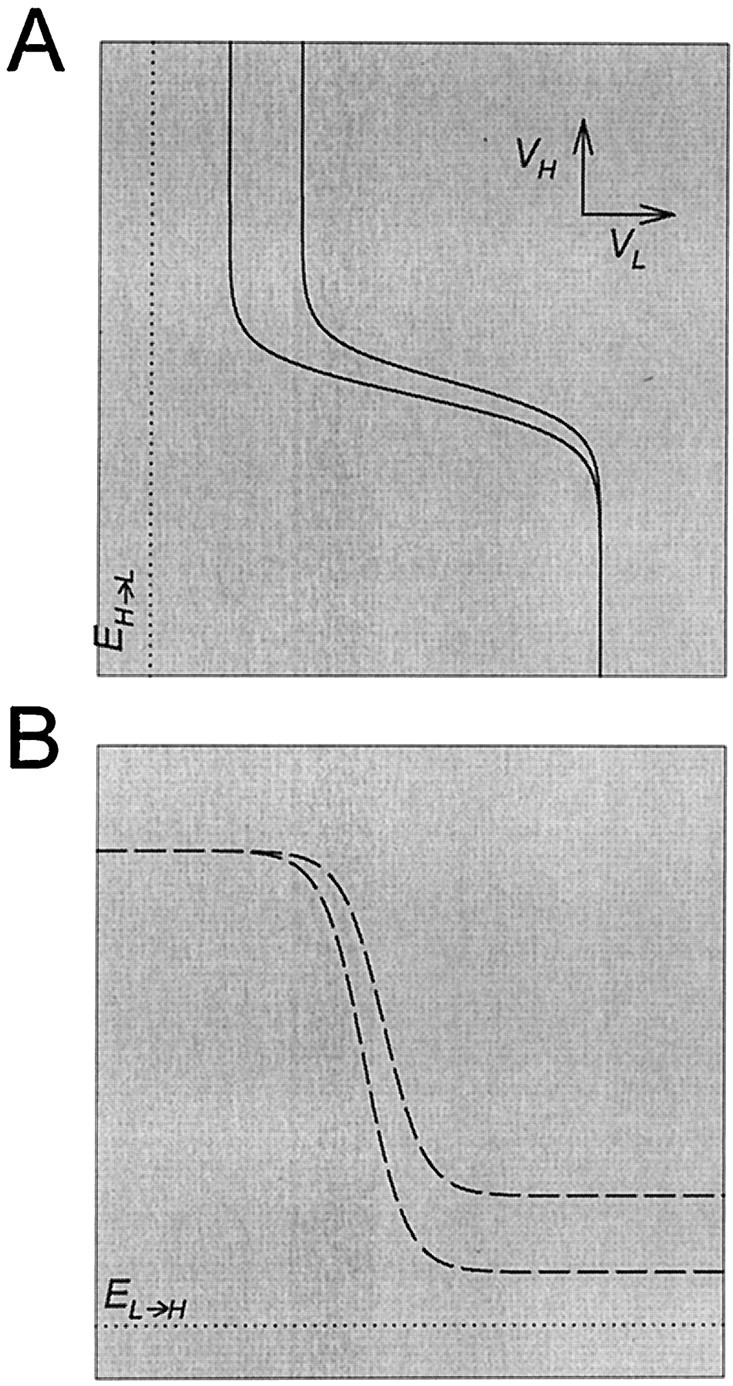

Fig. 7.

Oscillations are disrupted when the activation curve of one of the reciprocal inhibitory synapses is too steep.A, Voltage traces show the alternation of activity in L and H. At the time indicated by the vertical arrow, the H to L synapse is made all-or-none by changing its activation curve to a step function. The dotted line denotes the thresholdVT for presynaptic inhibition.B–D show the phase planes at the three times marked inA. Solid and dashed curvesare the L and H nullclines. The vertical white lineindicates the threshold VT.

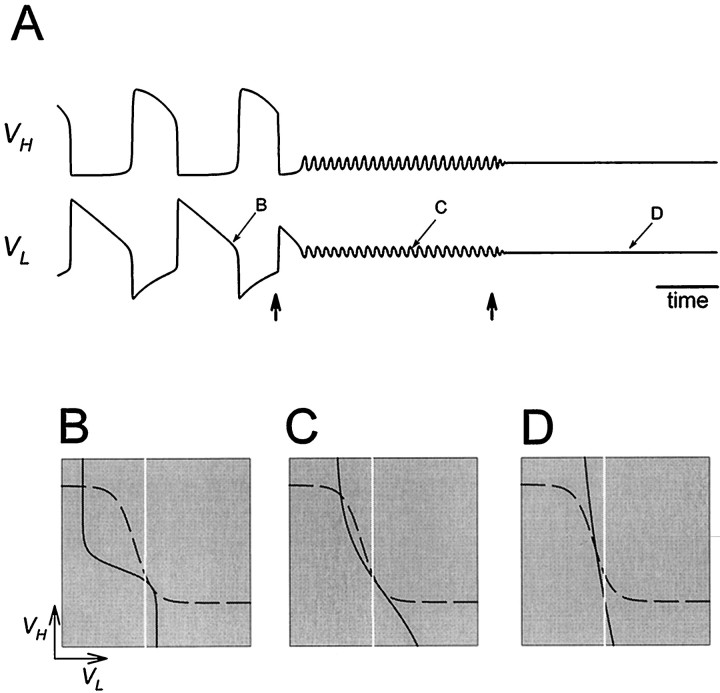

Fig. 8.

Oscillations are disrupted when the activation curve of one of the reciprocal inhibitory synapses is too shallow.A, Voltage traces show the alternation of activity in L and H. At the time indicated by the first vertical arrow, the activation curve of the H to L synapse is made fivefold shallower. At the time indicated by the second vertical arrow, the activation curve of the H to L synapse is made less steep by a factor of two. B–D show the phase planes at the three times marked in A. Solid anddashed curves are the L and H nullclines. Thevertical white line indicates the thresholdVT.

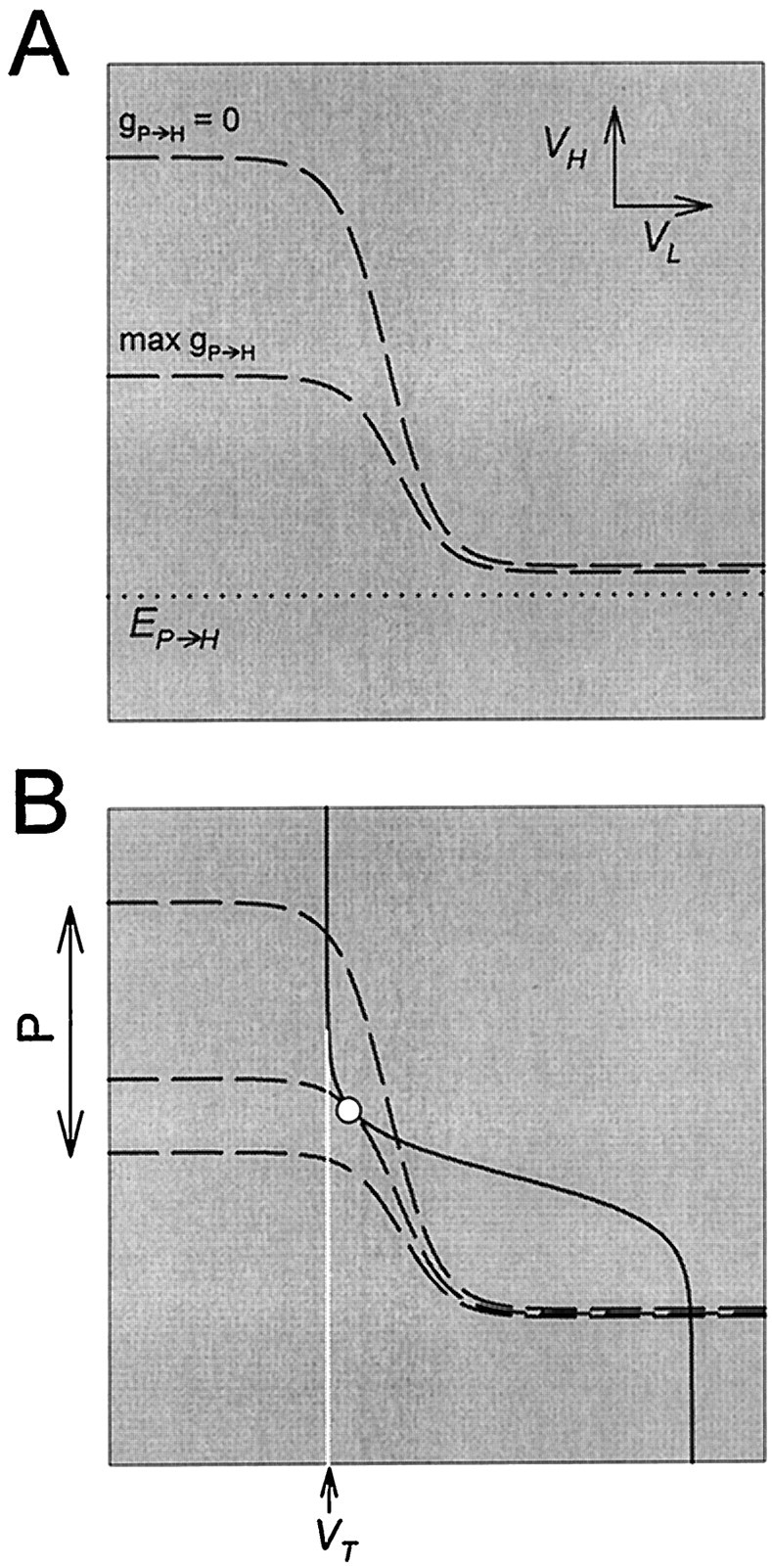

Fig. 11.

Analysis of one cycle of the oscillation in the presence of the periodic P input. A, Top, middle, and bottom traces show the voltage traces of H and L and the modulatory excitation s.B–E show theVL–VH phase plane at the four representative times marked in A. In each panel, the two dashed curves show the H nullcline when the periodic input P is at zero and at its maximum. Thesolid line is the L nullcline, and ○ denotes the position of the phase point at that time. In each panel, thearrow indicates the movement of the phase point along the trajectory (shown by the dotted line up to the next representative time). The vertical white line indicates the threshold VT for presynaptic inhibition of s by L.

RESULTS

Figure 2 illustrates oscillations that result from reciprocal inhibition between two passive neurons with different resting membrane potentials, provided that the L cell receives a slow excitation. Figure 2A shows the voltage traces of the two cells, L and H, together with s(the slow excitation of L), mL→H (the activation of the L to H inhibition), and mH→L(the activation of the H to L inhibition). Figure2B,C plots the synaptic transfer functions (Eq. 3, 4) of the L to H and H to L synapses, respectively. When the two cells are uncoupled (left section), they remain at their respective resting potentials: L at a low potential and H at a high potential. In the middle section, L receives an excitatory input. This input depolarizes L but does not produce oscillations. In the right section, the reciprocal synapses between L and H are introduced and the two cells oscillate in antiphase. At the onset of the H plateau,mH→L increases rapidly to 1, andmL→H decreases rapidly to 0. At the onset of the L plateau, the reverse happens. During the H plateau sgrows slowly, and during the L plateau s decays slowly. It is the rates of growth and decay of s that determine the durations of the plateaus, and therefore the period of the oscillations.

We first describe how graded reciprocal inhibition gives rise to a state equivalent to excitability. Two complementary methods are used. The first method uses the I–V curves in the pair of neurons, because these are more familiar to many electrophysiologists. Subsequently we use phase plane analysis, because this is a mathematically compact formalism to elucidate the mechanism of oscillation in this system.

Reciprocally inhibitory graded synapses produce excitability:I–V curves

In this section we use the I–V curves of the pair of neurons to show how inhibitory graded synapses between two passive cells can produce a state equivalent to excitability. The inhibitory graded synapses create a region of negative slope conductance in theI–V curves of the two cells. In physiological terms, the negative slope in the I–V curves is tantamount to membrane excitability. For either cell, this region of negative slope conductance can produce regenerative dynamics, provided that the membrane potential is brought into this region. We show that this shift in the membrane potential can be obtained by an excitatory input to one of the cells. We treat the excitatory input s as a parameter: the effects of the reciprocal synapses on theI–V curves at three representative values of sare discussed.

We start by describing the I–V curves of the two passive cells when uncoupled. In Figure3A the I–V curves of the L neuron and H are plotted for three different values of excitatory input into L (s = 0, 0.5, and 1) when there are no synaptic connections between L and H. The two I–Vcurves are plotted together. The zero points on the I–Vcurves are the resting potentials of the cells. Because both cells are passive, the I–V curves are linear. Without the excitatory input s, the resting potential of the L neuron (marked by ▵) is low, whereas the resting potential of H (marked by ▿) is high (Fig. 3A, left panel). With a larger excitatory inputs, the I–V curve of L becomes steeper, and the resting potential of L becomes larger (Fig. 3A, middle andright panels). Because there is no slow excitation to H, theI–V curve of H is not affected.

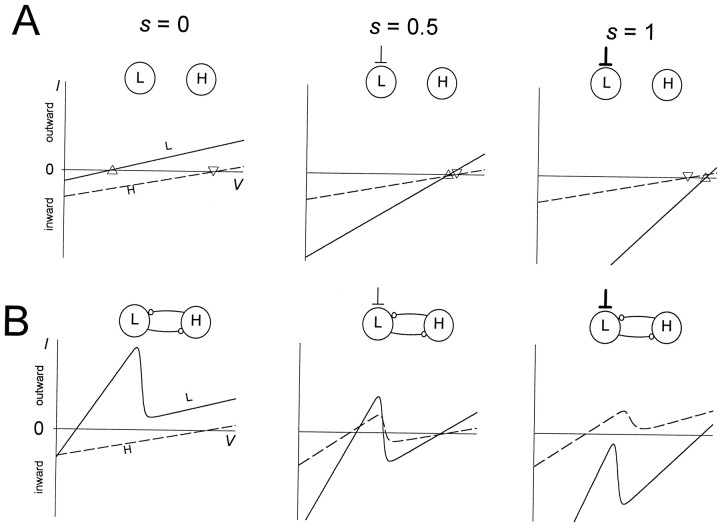

Fig. 3.

Reciprocal graded inhibition produces a region of negative slope conductance in the I–V curves. To obtain steady-state I–V curves, s was treated as a parameter. The I–V curves of L(solid line) and H (dashed line) are shown for three values of s (0, 0.5, and 1) in the absence (A) and presence (B) of the reciprocal inhibitory synapses. The resting potentials of L (marked by ▵) and H (marked by ▿) are shown in A.

Figure 3B shows the I–V curves of L and H when the reciprocally inhibitory synaptic connections between these two cells are included. We first describe the case in which there is no excitatory input to L (Fig. 3B, left panel). At rest, H is at a voltage greater than its threshold for transmitter release. When L is at low membrane potentials, H will release transmitter, so the L I–V curve has a steeper slope, reflecting this additional conductance. When L is at a higher membrane potential, where it inhibits H, the H to L synapse is turned off, so the L conductance is identical to its value in Figure 3A (left panel). The transition between the two regions of theI–V curves creates the negative slope conductance. Both reciprocally inhibitory synapses are therefore responsible for producing the cubic shape, or negative slope conductance region, in theI–V curve of L. In contrast with the I–V curve of L, the I–V curve of H is not affected by the reciprocal synapses and remains linear. This linearity comes from the fact that in the absence of excitatory input, L is never at a membrane potential where it can inhibit H. This will be clarified in the discussion of Figure 4B (left panel) below.

Fig. 4.

Graded inhibition produces sigmoidal nullclines in the VL–VH phase plane. To plot the L nullcline (NL) and the H nullcline (NH) in theVL–VH phase plane, s was treated as a parameter.NL (solid line) andNH (dashed line) are shown for three values of s (0, 0.5, and 1) in the absence (A) and presence (B) of the reciprocal inhibitory synapses. The resting potentials of L (marked by ▵) and H (marked by ▿) are shown in A. The intersections of NL andNH are steady states, and thearrows indicate the vector fields in the vicinity of these steady states. The direction of the vector field indicates whether the steady state is stable (○) or unstable (▪).

With a larger s, the excitatory (inward) current into L shifts the I–V curve of L downward (Fig. 3B,middle and right traces). WhenVH is low, this excitatory drive may allow L to depolarize enough to activate the L to H synapse. The activation of the L to H synapse generates an inhibitory (outward) synaptic current from L to H that causes the I–V curve of H to shift upward. The L to H synapse affects only a portion of the I–V curve of H, namely the portion where VH is small enough to allow the L to H synapse to be active. Therefore, when sis large enough, the I–V curve of H assumes a cubic shape.

Excitability in terms of nullclines

In Figure 4A, we show theVL–VH phase planes corresponding to the panels of Figure 3A. The nullclinesNL and NH are obtained from Equations 7 and 10 by setting the right-hand side to 0 when the maximal conductances of the reciprocal synapses are also set to 0. Because H receives no synaptic input from L, NHis independent of VL and is a horizontal line at the H resting potential. Similarly, NL is independent of VH and is a vertical line. This vertical line is the average of the resting potential of L and the reversal potential (Es) of the excitatory input s, weighted by their respective conductances. Whens = 0, the vertical line is at the L resting potential (Fig. 4A, left panel). With larger values ofs, the vertical line shifts to the right towardEs (Fig. 4A, middle andright panels). At the intersection ofNL and NH, bothVL and VH are at steady state. The steady-state points (○) shown in Figure4A are stable, as schematically indicated by the directions of the vector fields (arrows) around the fixed points (see figure legend for explanation).

In Figure 4B, we plot the H and L nullclines (from Equations 7 and 10) in theVL–VH phase plane, for the cases corresponding to the I–V curves plotted in Figure3B. We first describe the shape of NH(same in all three panels of Fig. 4B). At any value of VL, NH depends on the H resting potential, the reversal potential of the L to H synapse, and their corresponding conductances. WhenVL is small, the L to H synapse is off, andNH lies at H resting potential. AsVL increases, the L to H synapse activates, andNH gets closer to the reversal potential of the L to H synapse. The sigmoidal shape of NHreflects the shape of the gating function of the L to H synapse. Similarly NL assumes a sigmoidal shape lying between the resting potential of L and the reversal potential of the H to L synapse. NL depends on s, and changes are shown in Figure 4B.

Now consider the case where there is no excitatory input into L (Fig.4B, left panel). Because the resting potential of L is close to the reversal potential of the H to L synapse,NL spans a small range ofVL. As a consequence, at steady stateVL is restricted to values for whichNH lies near its maximum, the resting potential of H. Hence, for the whole range of VH, the synapse from L to H is off. This explains the linearity of theI–V curve of H in Figure 3B (left panel).

From Equation 10, NL depends on the conductances and reversal potentials of L and the inputs to L. When sbecomes larger, the relative “weight” of the reversal potential of the excitatory input increases. Because this reversal potential is more positive than both the L resting potential and the reversal potential of the H to L synapse, NL moves to the right. Moreover, when VH is low (and therefore the inhibitory input from the H to L synapse is small), s has a larger relative contribution, and NL is stretched more to the right.

The intersections of NL andNH represent steady states for a fixed value ofs. When s = 0 (no excitation to L), the two nullclines intersect at a high VH and a lowVL (Fig. 4B, left panel). When s is at its maximal possible value of 1 (maximal excitation to L), the two nullclines intersect at a lowVH and a high VL (Fig.4B, right panel). The intermediate cases = 0.5 is shown in Figure 4B(middle panel). In this case, the two nullclines intersect at three points. In such a case, the middle intersection (▪) is an unstable steady state (saddle point). All other intersections (○) are stable. The stability of the steady states can be seen from the local vector field, as shown schematically in Figure4B (arrows in the panels).

Dynamics of the L/H/s oscillation when L and H are passive

The oscillation in the L/H/s system comes about becauses, gated by the voltage of L, varies slowly. The analysis of the oscillation can be performed using either the I–Vcurves or the nullclines in theVH–VL phase plane. Although reasoning with the I–V curves is more intuitive to some physiologists, constructing the I–V curves requires an extra step in which one voltage is computed in terms of the other and the current value of s (see Materials and Methods). An advantage of nullclines is that they are directly computable from Equations 2 and 9. Thus, with nullclines, it is easier to be explicit about the effect of changing parameters such as degree of gradation of synapses and ionic conductances. Moreover, the I–V curves describe the behavior of the cells in steady state based on the assumption that VH adjusts instantaneously asVL changes and vice versa. This assumption is only an approximation to the full dynamics of VHand VL captured in the phase-plane analysis. For these reasons, we shall use the phase-plane analysis to describe the oscillations in the full system.

We start by describing one cycle of the model oscillation in the case where L and H have passive intrinsic properties. Figure5A showsVH, VL, ands in the time domain. The presynaptic inhibition ofs by L is all-or-none. The white line denotes the thresholdVT for presynaptic inhibition of s by L. The slow excitatory input s grows whenVL is below VT and decays otherwise (Equation 8). Figure 5B–G illustrates the phase plane at six representative times during the oscillation. These times are marked in Figure 5A. In each of the panels (B–G), we show the L nullcline (solid curve) and the H nullcline (dashed curve). We also show the complete trajectory of the oscillation (dotted curve; same in all panels) in theVL–VH phase plane. In each of the panels (B–G) the white circle marks the point on the trajectory at the correspondingly labeled time inA. We refer to this point in B–G as thephase point. The gray circle marks the phase point at the next indicated time. A single arrow indicates the motion of the phase point along the trajectory from the white to the gray circle. Double arrows in D and G indicate fast transitions between L plateau and H plateau. The vertical white line denotes the threshold VT.

In Figure 5B,C, the phase point follows the quasi-steady state, with VH decreasing from a high value andVL increasing from a low value. The slow movement of the phase point corresponds to the H plateau. In panelsB–D, VL is belowVT and s increases, causing the L nullcline to shift to the right. In D, the L nullcline separates from the H nullcline at the phase point. At this time the quasi-steady state is lost through a saddle-node bifurcation. Immediately after this time, the phase point jumps to the only remaining quasi-steady state (D, bottom right). This is the beginning of the L plateau and the termination of the H plateau. This fast transition occurs because, away from the quasi-steady states, dVL/dt and dVH/dt are large in magnitude. During this transition VL jumps aboveVT, and L turns the modulatory excitation off. At this time s starts to decay, causing the L nullcline to shift to the left (E–G). The slow movement through the quasi-steady state shown in E corresponds to the movement along the L plateau. In G, the L nullcline separates from the H nullcline, and the bottom right quasi-steady state is lost through a saddle-node bifurcation. The phase point jumps to the top left quasi-steady state. This is the beginning of the H plateau and the termination of the L plateau. During this transitionVL falls below VT and turns the modulatory excitation on. The L nullcline configuration returns to that of B, and the cycle repeats.

A necessary condition for sustained oscillations

For the oscillation mechanism described above to work, the slow modulatory excitation s must grow during the H plateau and decay during the L plateau. During the H plateau,VL must be belowVT, otherwise s will stop growing. Similarly, during the L plateau, VLmust be above VT, otherwise swill stop decaying. Therefore, the threshold VTfor presynaptic inhibition of s by L must lie between the two values of VL, just before the onset and just before the termination of the L plateau. This condition can be formulated as a geometrical condition on the nullclines in theVL–VH phase plane.

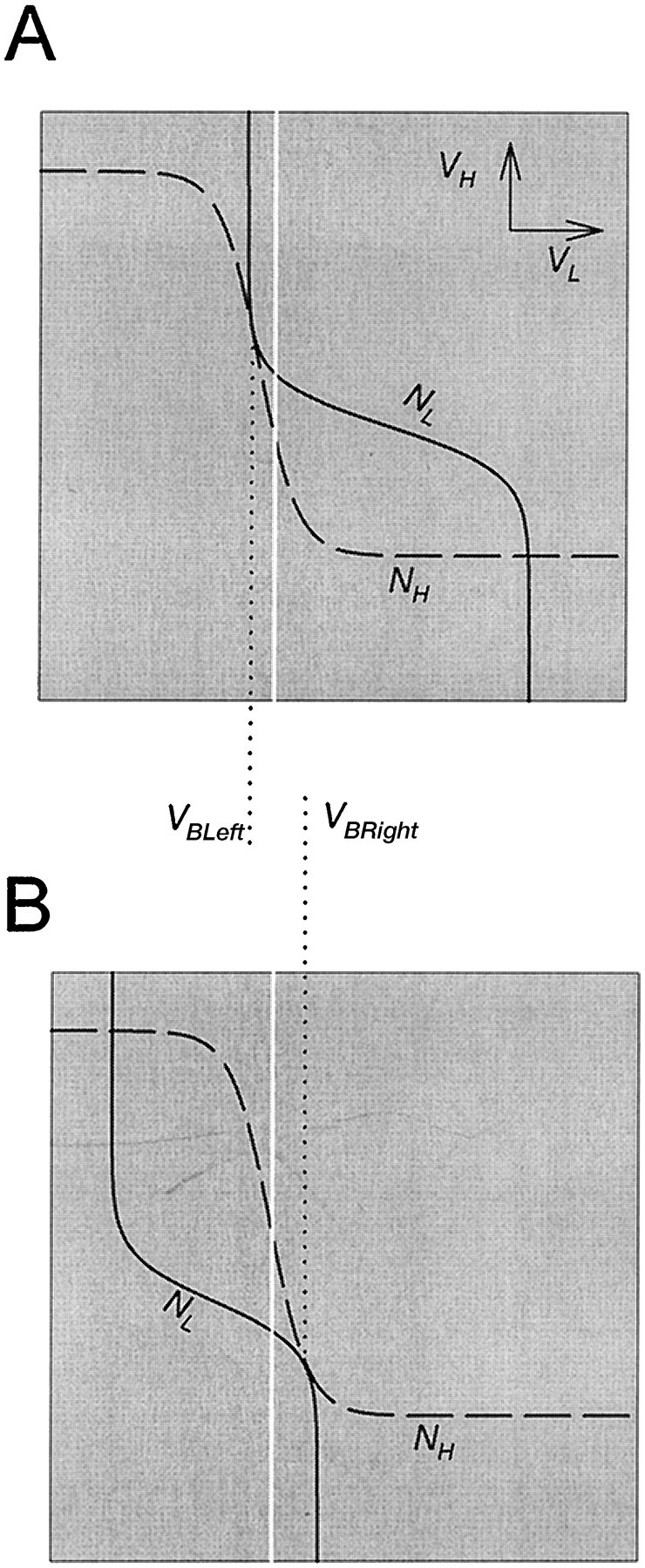

In the VL–VH phase plane there are two values of s (Fig. 5,D,G) for which the L nullcline is tangent to the H nullcline. These two values ofs define the two saddle-node bifurcation points. The two corresponding phase planes are shown again in Figure6. VBLeft andVBRight (marked by dotted drop lines) are the values of VL at the two bifurcation points. These two values are, respectively, the voltages of L just before the onset and just before the termination of the L plateau. The top left quasi-steady state (Fig. 5D) may be lost only whenVBLeft is below VT. Otherwise the voltage of L reaches VT, where s stops growing, and the L plateau does not occur. The bottom right quasi-steady state (Fig. 5G) may be lost only when VBRight is above VT. Otherwise the voltage of L reaches VT wheres stops decaying, and the L plateau does not terminate. Therefore, oscillations occur only if VT(indicated by the white line in Fig. 6) is strictly betweenVBLeft and VBRight. Note that this is the only restriction on VT. As long as this requirement is satisfied, the exact location ofVT with respect to other voltage-related factors (such as the synaptic transfer functions) does not affect the oscillations.

Fig. 6.

The L nullcline (solid line) and H nullcline (dashed line) are tangent at two distinct values of VL. A, The tangency on the top left branch of the H nullcline defines the saddle-node bifurcation point that corresponds to the onset of the L burst. B, The tangency on the bottom right branch of the H nullcline defines the saddle-node bifurcation point that corresponds to the termination of the L burst. A necessary condition for oscillations is that the thresholdVT (white line) for presynaptic inhibition lies strictly between theVL values (VBLeftand VBRight) at these two tangency points.

We now discuss how several parameters affect the generation of oscillations.

The effect of graded synaptic transmission

In this model, the reciprocally inhibitory synapses are graded. The graded nature of these synapses gives rise to the sigmoidal shape of the L and H nullclines (Fig. 4), and the cubic shape of theI–V curves (Fig. 3). As discussed below, the sigmoidal shapes of both nullclines are essential to the existence of oscillations. Below, we discuss the effect of the slope (kH→L from Equation 3) of the activation curve of the H to L graded synapse. There is a similar effect for the slope (kL→H from Equation 4) of the activation curve of the L to H synapse.

If the activation curve of the H to L synapse is too steep, oscillations will not occur. Figure7A shows how the voltage traces of H and L are affected when the H to L synapse is abruptly changed from graded to all-or-none. Shortly after the beginning of an H plateau, at the time indicated by the vertical arrow, the H to L synapse is made all-or-none by changing its activation curve to a step function. As a result, the plateau of H is prolonged, and as it terminates L starts its plateau. The L plateau, however, does not terminate; instead, VL settles atVT and the oscillation dies. Figure7B–D shows the phase planes at the times indicated inA. When the H to L synapse is not graded, the synapse is “off” below vH→L (Equation 3) and “on” above vH→L, giving rise to a step-like shape of the L nullcline (C, D). Because of the step-like shape of the L nullcline, the left and right bifurcation valuesVBLeft and VBRight (Fig.6) are identical. Therefore there is no oscillation becauseVT cannot be strictly betweenVBLeft and VBRight. The trajectory will approach the stable fixed point at the intersection ofVT and the two nullclines (Fig.7D).

If the activation curve of the H to L synapse is too shallow, oscillations will also die. Figure8A shows how the voltage traces of H and L are affected when the slope of the gating function of the H to L synapse is decreased. At the time indicated by the first arrow, the slope of the gating function is reduced fivefold (see Fig. 8 legend for values). The oscillations after this change become fast and small in amplitude. A further twofold reduction of the slope at the time indicated by the second arrow causes the oscillation to die completely. Figure 8B–D shows the phase planes at the times indicated in A. In B andC, the H and L nullclines are shown at the L plateau termination. In the case shown in B, the two bifurcation points are well separated and oscillations occur as described in Figure5. In C, because the slope of the L nullcline is closer to that of the H nullcline, the two bifurcation points are much closer to each other. Consequently, oscillations still occur, but with small amplitude. In D, the L nullcline is steeper than the H nullcline, and the two nullclines always intersect in only one point. As a result, no bifurcation points exist, and there is no oscillatory solution.

The effect of the strength of the reciprocally inhibitory synapses

The growth of the slow modulatory excitation s is directly opposed by the H to L synapse; therefore, the stronger this synapse, the longer the period. The decay of s interacts with the L to H synapse by determining how long L will inhibit H. Therefore, if the L to H synapse is stronger, s must decay longer before H can escape the inhibition. These effects can be analyzed by examining how changing the strength of the synapses affects the shape of the nullclines.

Increasing the strength of the H to L synapse pulls the left (top) branch of the L nullcline left toward EH→L(Fig. 9A). This increase changes the shape of the L nullcline, and its effect is similar to increasing the slope of the H to L activation curve discussed above. This change in the shape of the L nullcline results in a larger period because s has to grow to a larger value before the onset of the L plateau occurs. This will affect mainly the H plateau duration; to a smaller extent, the L plateau duration also increases. The increase in the L plateau duration is limited, because on the bottom right branch of the L nullcline s is initially large, but exponentially decaying (see Equation 8), hence the phase point traverses this piece of the L nullcline rapidly. If the H to L synapse is made too strong and cannot be compensated for by the growth ofs, the bifurcation that allows the onset of the L plateau will not occur, and the oscillation will be disrupted.

Fig. 9.

The effect of strength of the reciprocally inhibitory synapses on the nullclines. A, Increasing the strength of the H to L synapse pulls the top left branchof the L nullcline (solid line) toward the reversal potential (dotted line) of the H to L synapse.B, Increasing the strength of the L to H synapse pulls the bottom right branch of the H nullcline (dashed line) toward the reversal potential (dotted line) of the L to H synapse.

Similarly, increasing the strength of the L to H synapse pulls the bottom (right) branch of the H nullcline down towardEL→H (Fig. 9B) and has an effect similar to increasing the slope of the activation curve of the L to H synapse. This change in the shape of the H nullcline hinders the termination of the L plateau, because s has to decay to a smaller value before the onset of the H plateau. However, this effect is small, and increasing the maximal conductance of the L to H synapse never disrupts the oscillation. In the extreme case where this maximal conductance is very large compared with the leak conductance of H, the bottom right branch of the H nullcline reaches the reversal potential of the L to H synapse, but the L plateau still terminates because the decay of s still shifts the L nullcline to the left until it becomes tangent to the H nullcline (see Fig. 5).

The effect of the strength and time constant of the excitatory input s

Decreasing the maximal conductance gs of the excitatory input to L has an effect that is similar to increasing the maximal conductance of the H to L synapse. Ifgs is too small, the L nullcline does not move enough to the right for the bifurcation and the transition to L plateau to occur. In this case the oscillations are disrupted. Ifgs is decreased, but not to the extent that the bifurcation is prevented, the period of oscillation will increase, mainly by increasing the H plateau duration. Note that changing the time constants for the growth and decay of s will change the period of oscillation in a linear manner. This linear relation is a simple consequence of the fact that Equation 8 is linear on either side of VT.

The effect of fast periodic inhibition to H

Up to this point we have described the mechanism of oscillation in an asymmetric pair of reciprocally inhibiting neurons, balanced by a slow excitatory modulation. In the model of MCN1-activated gastric mill rhythm that inspired this work (Nadim et al., 1998), we found that this gastric mill rhythm is strongly influenced by a periodic inhibitory input to Int1, the neuron represented by H. We therefore ask how the mechanism of oscillation and geometry of the phase plane, as described above, is affected by the presence of a periodic input P to H.

The input of P to H is fast, inhibitory and periodic. When P is added to the circuit, the network is described by Equations 8, 9, and 11. Figure 10A shows the H nullclines NH, when the P input is at 0, and ÑH, when the P input is at its peak value. ÑH depends on the conductances and reversal potentials of H and all of its synaptic inputs (Equation 12). When VL is low, the L to H synapse is off and the effect of the P input onÑH is relatively large. Therefore, the P input lowers the left branch of the H nullcline more than the right branch. This in turn implies that during an L plateau, when the phase point is on the bottom right branch of the H nullcline, the input from P can be effectively ignored.

Fig. 10.

The effect of fast periodic inhibition to H on the nullclines. A, The H nullcline (dashed line) is shown in the absence of the inhibition (P) and in the presence of maximal inhibition. This inhibition pulls the top left branch of the H nullcline toward the reversal potential (dotted line) of the P to H synapse. B, The periodic inhibition of H by P swings the H nullcline back and forth between the two limits shown inA. The L nullcline is not affected. At some intermediate value of the P input, the two nullclines become tangent, producing a saddle-node bifurcation point (○). The vertical white line indicates the threshold VT for presynaptic inhibition of s by L.

We start with an L/H/s network that is not oscillatory when no P input is present. Figure 10B (top H nullcline) shows such an example, where VT lies to the left of the left bifurcation point (○). This case corresponds to a stable steady state in the three-dimensional system, with H at a high membrane potential and L at a low membrane potential. When the P input is added, the H nullcline swings periodically between the two limits shown in Figure 10A. When the phase point is on the top left branch of the H nullcline, during one such periodic swing, the intersection between the two nullclines disappears through a saddle-node bifurcation (Fig. 10B, ○). Thus, the P input allows a transition to an L plateau, even before reaching its maximum (bottom H nullcline). This transition is sufficient to produce an oscillatory solution in the system.

Figure 11A showsVH, VL, ands in the time domain. In B–E, we show the phase planes at the times indicated in A. In each panel, the white circle denotes the position of the phase point along the trajectory. InB, the phase point is at the quasi-steady state (the intersection of the two nullclines). The periodic input from P moves the H nullcline down rapidly, back and forth between the two limits shown as dashed curves. The trajectory follows this nullcline as shown by the dotted curve. As s grows, the L nullcline moves to the right. In C, the top left quasi-steady state is lost during a P input (through a saddle-node bifurcation), and the phase point jumps to the bottom right quasi-steady state. At this time,s starts to decay, and the L nullcline moves to the left (D). In E the bottom right quasi-steady state is lost, and the phase point jumps back to the top left quasi-steady state, completing the cycle. Note that the P input does not contribute to the loss of the bottom right quasi-steady state. In fact, the P input hinders the termination of the L plateau, although to a very small extent.

We mentioned earlier that oscillations are disrupted if either of the reciprocal synapses is all-or-none. However, in the presence of the P input, oscillations are still possible when either one of the synapses is all-or-none and the other is graded. We will discuss the case in which the L to H synapse is all-or-none (and the H nullcline is step-like) and the H to L synapse is graded (and the L nullcline is sigmoidal). The discussion of the other case is similar. As discussed in Figure 6, when one of the two synapses is all-or-none, the two saddle-node bifurcations values VBLeft andVBRight are identical. Recall that the decay ofs will result in the termination of the L plateau only ifVT is to the left ofVBRight. In general, the transition to an L plateau onset occurs when the two nullclines separate, causing the top left intersection point to disappear. However, when the L to H synapse is all-or-none, the growth of s is not sufficient to separate the two nullclines, because VT is to the left of VBLeft (becauseVBLeft = VBRight; see the section entitled A necessary condition for oscillations). In the presence of the P input, the left branch of the H nullcline is periodically shifted downward (as shown in Fig. 10B). This provides an alternative way for separating the two nullclines, allowing an L plateau onset. Note that the growth of scorresponds to accumulating excitatory input in L, whereas the P input corresponds to removing inhibition from L. The L plateau onset in the presence of the P input is caused by this periodic removal of inhibition.

The P input can also be added to an L/H/s network that is already oscillatory, with minimal changes in the description of Figure11. Moreover, whether or not the L/H/s network is oscillatory, the input from P determines the timing of the transition from H plateau to L plateau. The control of the timing of this transition by P leads to the frequency control mechanism (F. Nadim, S. Epstein, Y. Manor, J. Ritt, E. Marder, and N. Kopell, unpublished observations).

DISCUSSION

Symmetric and asymmetric half-centers

Reciprocal inhibition is a common circuit element in the nervous system. Brown (1914) coined the term “half-center” oscillator to capture the notion that reciprocal inhibition between functional antagonists in motor systems could account for the repeating patterns of alternating activity between flexors and extensors. Brown (1914)understood that mechanisms for producing the transitions between activity in the two halves of the circuit were required. In Brown’s work, and whenever reciprocal inhibition is found between different classes of neurons, the two sides of the half-center are, by definition, not identical. In contrast, reciprocal inhibition also subserves left–right alternation in many motor systems. For example, in the leech heartbeat system, the kernel of the central pattern-generating network is formed by two, apparently identical neurons that form reciprocal inhibitory connections (Calabrese, 1995;Marder and Calabrese, 1996).

There have been a number of theoretical studies on the factors that control the behavior of half-center oscillators when the two neurons that form them are identical (Perkel and Mulloney, 1974; Wang and Rinzel, 1992; Skinner et al., 1993, 1994; Van Vreeswijk et al., 1994;Nadim et al., 1995; Olsen et al., 1995; White et al., 1998). However, almost no theoretical work has been done on the problem of how to produce stable alternating bursts of activity from reciprocally inhibitory neurons with different intrinsic membrane properties. This is particularly striking because many, if not most, cases of reciprocal inhibition occur between neurons that are not likely to have identical properties.

Several workers have noted the necessity of “balancing the excitability” of the two sides of the half-center to produce rhythmic alternating bursts. For example, Miller and Selverston (1982b) were able to produce stable half-center-like oscillations from the reciprocally inhibitory lateral pyloric and pyloric dilator neurons of the stomatogastric ganglion by injecting current into one of them.Sharp et al. (1996) used the dynamic clamp to construct stable half-center activity with gastric mill neurons of the stomatogastric ganglion and sometimes found it necessary to set the leakage current to balance the two neurons (A. Sharp, F. K. Skinner, and E. Marder, unpublished observations). In a similar situation, Gramoll et al. (1994) demonstrated that a leak current controls a switch from the peristaltic to the synchronous activation in the leech heartbeat system.

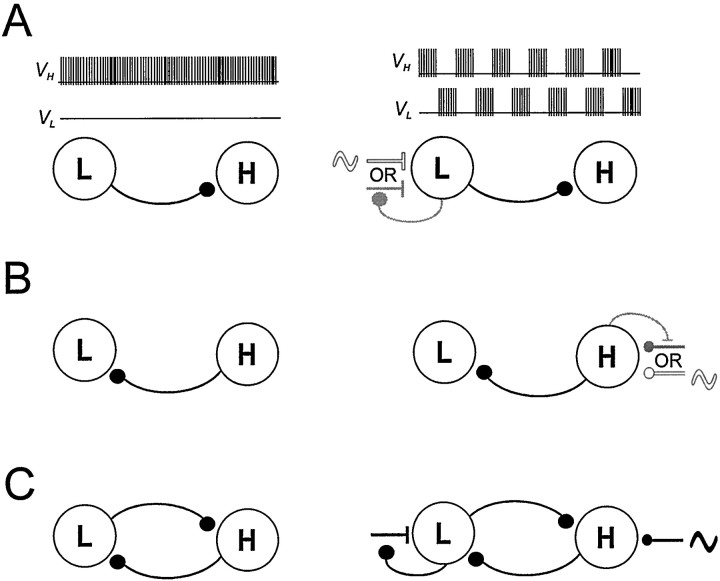

In this paper we describe mechanisms by which modulatory and synaptic inputs compensate for the asymmetries in the membrane properties of two neurons so that they can fire in alternating bursts in a half-center mechanism (Fig. 12). One take-home message of our work is that synaptic inputs can form or activate a functional network by bringing the two neuronal elements into the balance needed for stable alternation.

Fig. 12.

Schematic drawing showing circuit configurations that can be driven to produce half-center oscillations from asymmetric neurons. The basic circuit consists of two neurons that in the absence of extrinsic input (A–C, left column) are quiescent (L) and tonically active (H). A, Circuit with a single inhibitory synapse from L to H. An excitatory input to L that is either periodic (white ∼︀) or presynaptically gated by L (gray ∼︀) produces antiphase oscillations.B, Circuit with a single inhibitory synapse from H to L. An inhibitory input to H that is either periodic (white∼︀) or presynaptically gated by H (gray ∼︀) produces antiphase oscillations. C, Circuit with reciprocally inhibitory synapse between L and H. An excitatory input to L that is presynaptically gated by L and a periodic inhibitory input to H work synergistically to produce antiphase oscillations.

In Figure 12 we show several different circuit configurations that can produce half-center alternations from asymmetric neurons: one tonically firing neuron, H, and one quiescent neuron, L. In Figure12A we show a circuit in which there is an inhibitory synapse from L to H. In the absence of external input, this circuit will not oscillate. However, a periodic excitatory input to L will entrain the two cells to fire in alternation at that period. Provided that the inhibitory synapse between the two cells is fast relative to the period of the excitatory input, this circuit will faithfully follow rapid changes in the input period. Alternatively, if the excitatory input to L is not periodic but is presynaptically gated by L, the circuit can still produce antiphase oscillations. In this case, the period of oscillations will be determined by the time constants of growth and decay of the excitation.

In Figure 12B, the H neuron makes an inhibitory synapse onto the L neuron. This circuit will not oscillate in the absence of external drive, but it can produce oscillations if H receives external periodic or presynaptically gated inhibition.

In both cases described (shown in Figure 12A,B), there is no reciprocity between the L and H cells. Hence, the circuit is not very robust; in particular, an input (modulatory or other) to the postsynaptic cell (H in A or L in B) may disrupt the antiphase oscillations. A natural extension of these two elemental circuits is an asymmetric pair of reciprocally inhibitory neurons such as the one described in this paper (Fig. 12C). In this circuit external inhibition of H and external excitation of L synergistically combine to produce robust alternations that can be frequency-modulated over a large range.

Mathematical analysis

Although a detailed model of this network exists (Nadim et al., 1998), the small network we present shows with greater clarity the origin of the oscillation and some of its properties, notably what controls the frequency and how the oscillation depends on parameters such as synaptic conductances.

We exploit the fact that the three-dimensional system (Equations 2, 8, and 9) has two fast variables and one slow variable; the value of the slow variable (the excitation) determines the values of the voltages to which the two cells rapidly equilibrate. The separation of fast and slow time scales is a fundamental tool for analysis of large classes of equations. Our analysis uses methods described in Rinzel and Ermentrout (1998), in which slowly changing parameters can produce sharp changes in system behavior.

The analysis of oscillations in the network was performed in terms of a family of slowly moving nullclines in the phase space of the two voltages, with the amount of excitation to the low cell L as a parameter. The construction of the periodic solution can also be made using a family of I–V curves for each of the cells. As stated in Results, the formulas for the I–V curves are derived using the nullclines, so the explicit formulas are more complicated and therefore less transparent for understanding how changes of parameters change behavior. Other descriptions can also be used. For example, we (F. Nadim, S. Epstein, Y. Manor, J. Ritt, E. Marder, and N. Kopell, unpublished observations) have analyzed the effect of the fast forcing on this three-dimensional oscillator, and we reduced the oscillator to a two-dimensional model whose variables are the amount of excitation and the voltage of the low cell.

Graded transmission can produce network oscillations from passive neurons

A novel finding described in this paper is that two entirely passive neurons can generate oscillatory network activity when they are connected by graded reciprocal inhibitory synapses and receive a periodic input. The terms “escape” and “release” were introduced by Wang and Rinzel (1992) to describe how the transitions in a half-center formed from excitable cells occur. In a release, the transition is determined by the properties of the active neuron, and in an escape it is determined by the properties of the inactive neuron. In the simplest case, release transitions occur when the active neuron falls below a voltage threshold sustaining its burst, and an escape occurs when the inactive neuron crosses a voltage threshold for burst initiation. Both of these transitions occur because one of the neurons crosses a voltage threshold independent of the properties of the other neuron. However, in the case studied here, in which neither neuron has intrinsic excitability, the concepts of escape and release are not useful, because the transitions do not occur because either of the neurons crosses a voltage threshold. Rather, it is the reciprocal inhibition that constructs the network excitability, and therefore neither cell has an individual voltage threshold that can provide a transition independent of the network.

Here we have studied two kinds of periodic inputs: a fast synaptic inhibition and a slow modulatory excitation that is converted to a periodic input by its presynaptic inhibition by the network. The graded activation of synaptic transmission creates a negative conductance region in the I–V curve that allows the oscillation to occur. The range and shape of the negative conductance region in theI–V curve are determined by the steepness of both synaptic activation curves and the strength of both synapses.

In the absence of the fast periodic input, the period of the half-center oscillation depends linearly on the rates of growth and decay of the slow modulatory excitation. The strength and steepness of the reciprocal inhibitory synapses also affect the period, but in a nonlinear manner. As discussed in detail in Results, increasing the steepness of activation or the strength of the inhibitory synapses prolongs the period of the oscillation. The latter effect was also seen by Sharp et al. (1996). The same relationships persist in the presence of the fast periodic input, but the fast input gates the transition time of one phase of the half-center oscillation.

When there is a periodic input (Fig. 12C), the network will oscillate if one of the synapses is not graded, as was the case inNadim et al. (1998). Moreover, in the absence of a periodic input, both synapses can be spike-mediated, provided that the durations of the spike-mediated IPSPs are of the same order of magnitude as the mean interspike interval during the burst, and either the synapse shows depression or the presynaptic neuron has spike rate adaptation. Either of these spike-mediated mechanisms is the functional equivalent of the graded synapses studied here, when considered on a time scale that averages over spikes.

Much of this analysis will hold for the case in which the asymmetric neurons are not passive but have excitable membranes. We have shown that a necessary condition for oscillations is that the threshold for presynaptic inhibition of the modulatory input is within a finite voltage interval. In some cases, intrinsic neuronal excitability may make the network oscillations more robust by widening this voltage interval. This will occur if the intrinsic excitability enlarges the negative conductance region of the I–V curve produced by the graded synapses. In other cases, the intrinsic voltage-dependent membrane conductances of the neurons may attenuate the negative conductance region of the I–V curve and therefore decrease the stability of the network oscillations.

Activation of an asymmetric half-center is an example of circuit reconfiguration

The asymmetric half-centers studied here do not function in the absence of their modulatory or synaptic drive. Therefore, although the circuit may be anatomically present, it will not be functional until enabled by the appropriate modulatory inputs that act to balance the well poised but inactive networks. In the case of MCN1 activation of the gastric mill rhythm, a slow modulatory excitation is the mechanism by which the half-center is balanced (Coleman et al., 1995). However, one can imagine a host of modulatory mechanisms (Harris-Warrick et al., 1992; Marder and Calabrese, 1996) that could bring the two sides of a half-center network close enough into balance to allow the circuit to work. In summary, we provide here an analysis of several mechanisms relevant to the activation of rhythmic alternation in half-center oscillators formed by nonidentical elements. The challenge in biological terms is to understand the cellular mechanisms by which modulatory substances and synaptic inputs achieve the right balancing act.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS17813 (E.M.) and MH47150 (N.K.), the Sloan Foundation, and the W. M. Keck Foundation. We thank Dr. Michael Nusbaum for introducing us to MCN1.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Eve Marder, Volen Center, MS 013, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454.

Dr. Manor’s present address: Department of Life Sciences, Ben-Gurion University, POB 653, Beer-Sheva, Israel 84105.

Dr. Nadim’s present address: Department of Mathematics, New Jersey Institute of Technology and Department of Biological Sciences, Rutgers University, 101 Warren Street, Newark, NJ 07102.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbas EA, Calabrese RL. Ionic conductances underlying the activity of interneurons that control heartbeat in the medicinal leech. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3945–3952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-12-03945.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TG. On the nature of the fundamental activity of the nervous centres; together with an analysis of the conditioning of rhythmic activity in progression, and a theory of the evolution of function in the nervous system. J Physiol (Lond) 1914;48:18–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabrese RL. Oscillations in motor pattern-generating networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:816–823. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman MJ, Meyrand P, Nusbaum MP. A switch between two modes of synaptic transmission mediated by presynaptic inhibition. Nature. 1995;378:502–505. doi: 10.1038/378502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friesen WO. Reciprocal inhibition: a mechanism underlying oscillatory animal movements. Neurosci Biobehav. 1994;18:547–553. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gramoll S, Schmidt J, Calabrese RL. Switching in the activity of an interneuron that controls coordination of the hearts in the medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis). J Exp Biol. 1994;186:157–171. doi: 10.1242/jeb.186.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris-Warrick RM, Marder E, Selverston AI, Moulins M. Dynamic biological networks. The stomatogastric nervous system, p. 328. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marder E, Calabrese RL. Principles of rhythmic motor pattern generation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:687–717. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marder E, Manor Y, Nadim F, Bartos M, Nusbaum MP. Frequency control of a slow oscillatory network by a fast rhythmic input: pyloric to gastric mill interactions in the crab stomatogastric nervous system. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;860:226–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller JP, Selverston AI. Mechanisms underlying pattern generation in lobster stomatogastric ganglion as determined by selective inactivation of identified neurons. II. Oscillatory properties of pyloric neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1982a;48:1378–1391. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller JP, Selverston AI. Mechanisms underlying pattern generation in lobster stomatogastric ganglion as determined by selective inactivation of identified neurons. IV. Network properties of pyloric system. J Neurophysiol. 1982b;48:1416–1432. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadim F, Olsen ØH, De Schutter E, Calabrese RL. Modeling the leech heartbeat elemental oscillator. I. Interactions of intrinsic and synaptic currents. J Comput Neurosci. 1995;2:215–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00961435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadim F, Manor Y, Nusbaum MP, Marder E. Frequency regulation of a slow rhythm by a fast periodic input. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5053–5067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-05053.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen ØH, Nadim F, Calabrese RL. Modeling the leech heartbeat elemental oscillator. II. Exploring the parameter space. J Comput Neurosci. 1995;2:237–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00961436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson KG, Ramirez JM. Influence of input from the forewing stretch receptors on motoneurones in flying locusts. J Exp Biol. 1990;151:317–340. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkel DH, Mulloney BM. Motor pattern production in reciprocally inhibitory neurons exhibiting postinhibitory rebound. Science. 1974;185:181–183. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4146.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinzel J, Ermentrout B. Analysis of neural excitability and oscillations. In: Koch C, Segev I, editors. Methods in neuronal modeling: from ions to networks. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1998. pp. 251–291. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowat PF, Selverston AI. Oscillatory mechanisms in pairs of neurons connected with fast inhibitory synapses. J Comput Neurosci. 1997;4:103–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1008869411135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satterlie RA. Reciprocal inhibition and postinhibitory rebound produce reverberation in a locomotor pattern generator. Science. 1985;229:402–404. doi: 10.1126/science.229.4711.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharp AA, Skinner FK, Marder E. Mechanisms of oscillation in dynamic clamp constructed two-cell half-center circuits. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:867–883. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skinner FK, Kopell N, Marder E. Mechanisms for oscillation and frequency control in reciprocal inhibitory model neural networks. J Comput Neurosci. 1994;1:69–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00962719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skinner FK, Turrigiano GG, Marder E. Frequency and burst duration in oscillating neurons and two-cell networks. Biol Cybern. 1993;69:375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein PSG, Grillner S, Selverston AI, Stuart DG. Neurons, networks, and motor behavior. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Vreeswijk C, Abbott LF, Ermentrout GB. When inhibition not excitation synchronizes neural firing. J Comput Neurosci. 1994;1:313–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00961879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XJ, Rinzel J. Alternating and synchronous rhythms in reciprocally inhibitory model neurons. Neural Comp. 1992;4:84–97. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X-J, Rinzel J. Spindle rhythmicity in the reticularis thalami nucleus: synchronization among mutually inhibitory neurons. Neuroscience. 1993;53:899–904. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90474-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White JA, Chow CC, Ritt J, Soto-Treviño C, Kopell N. Synchronization and oscillatory dynamics in heterogeneous, mutually inhibited neurons. J Comput Neurosci. 1998;5:5–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1008841325921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]