Abstract

Disseminated sporotrichosis may present with inflammatory arthritis and cutaneous ulcerations that mimic noninfectious skin conditions such as pyoderma gangreonsum (PG). Sporotrichosis must therefore be ruled out before administering immunosuppressive agents for PG. Furthermore, dimorphic fungi such as sporotrichosis may grow as yeast in bacterial cultures, even before fungal cultures become positive. We present a case of disseminated cutaneous and osteoarticular sporotrichosis mimicking PG and describe the differential diagnosis and the diagnostic and treatment approach to this condition.

Keywords: ulcer, deep fungal infection, septic arthritis, Sporothrix, disseminated fungal infection, United States of America

CASE REPORT

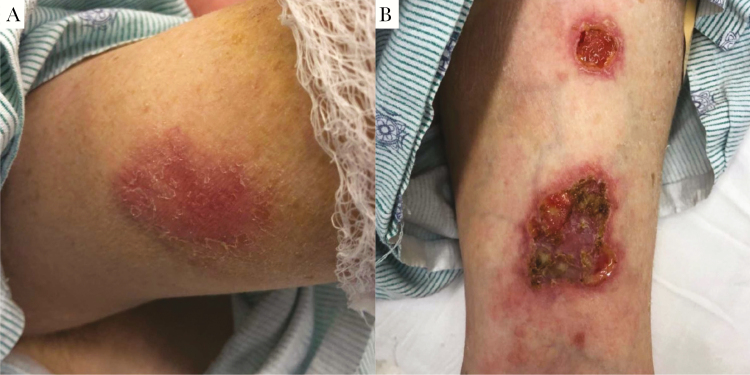

A 35-year-old woman with alcohol use disorder and type II diabetes presented with months of progressive, erythematous nodules and ulcerations. The initial lesion was an ulcerated nodule that appeared after falling on her right forearm. Similar lesions subsequently developed on her legs, contralateral arm, and abdomen (Figure 1). Concurrently, she developed asymmetric, large- and small-joint migratory arthritis and an unintentional 40-pound weight loss. She lived alone, previously worked as a landscaper, owned several indoor and outdoor cats, and denied recent sick contacts or travel outside California.

Figure 1. .

Skin lesions. A, Indurated, erythematous subcutaneous nodule with overlying scale on the right upper arm, representative of the early stages of evolution of these skin lesions. B, Left wrist exam, showing ulcerations with violaceous to erythematous undermined borders and a fibrinous base.

Skin biopsy demonstrated nodular vasculitis with negative organism stains, interpreted as erythema induratum. Blood cultures, coccidioidomycoses serologies, HIV serologies, and QuantiFERON TB-gold were negative. Given numerous ulcers and negative organism stains, a presumptive diagnosis of pyoderma gangreonsum (PG) was made, and prednisone and doxycycline were initiated.

Despite immunosuppressive therapy, her lesions progressed, particularly the right forearm ulceration. Magnetic resonance imaging of this extremity revealed deep soft tissue inflammation, including olecranon bursitis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and trochlear avascular necrosis. For these findings, she underwent surgical debridement of a presumed soft tissue infection (Figure 2A) and was subsequently transferred to our hospital for further debridement.

Figure 2. .

A, Right upper extremity lesion after second debridement surgery. Significant full-thickness ulcer with erythematous, undermined borders covers most of forearm. Yellow material is a combination of fibrinous debris and gel wound dressing. B, Biopsy sample demonstrating PAS-D staining of yeast surrounding subcutaneous arterioles.

Physical examination of the patient revealed numerous cribriform ulcerations with violaceous undermined borders (Figure 1) and right knee arthritis. No palpable lymphadenopathy was detected, and the remainder of her exam was normal. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed bilateral areas of hypolucency in each kidney, possibly compatible with pyelonephritis, though the patient lacked costovertebral angle tenderness and urine studies were negative. A chest CT detected no abnormalities. Brain imaging was not obtained; her neurologic exam was unremarkable. Right knee arthrocentesis showed 3000 white blood cells/mm3 with a monocyte predominance and negative organism stains. Repeat skin biopsies demonstrated Periodic acid-Schiff-diastase (PAS-D)-positive yeast surrounding subcutaneous arterioles (Figure 2B). Three days later, synovial fluid bacterial cultures also yielded yeast.

DIAGNOSIS: DISSEMINATED SPOROTRICHOSIS

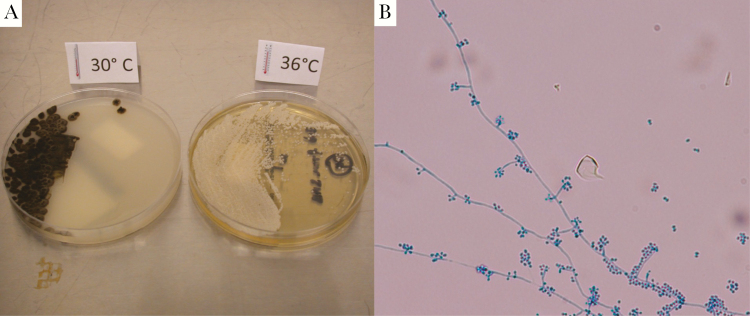

Empiric liposomal amphotericin (4 mg/kg daily) was initiated. The next day, fungal cultures taken from the right forearm during surgical debridement, grown at 30°C on potato flake agar, yielded mold (Figure 3A), morphologically identified as Sporothrix schenckii (Figure 3B), confirming a diagnosis of sporotrichosis.

Figure 3. .

Culture findings. A, Sporothrix schenkii is a dimorphic fungus that grows as a mold at 30°C and as a yeast at 37°C. Culture specimens from surgical debridement are shown. B, Speciation of the mold was confirmed by microscopic examination, demonstrating hyphae and flower-like conidia.

Corticosteroids were then tapered, and she completed 28 days of liposomal amphotericin, followed by oral itraconazole (induction at 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg twice daily), leading to resolution of most skin lesions. Joint involvement was managed conservatively without debridement or washout due to the high number of joints involved and evidence that medical management often suffices [1]. Recovery continued until 6 months later, when she was readmitted for worsening right arm and abdominal skin lesions, prompting concern for possible itraconazole resistance or failure (given intraconazole level was therapeutic). She was re-induced with amphotericin (4 mg/kg daily) for 3 weeks and then changed to oral posaconazole (300 mg once daily) based on initial sensitivity data (posaconazole minimum inhibitory concentration, 0.5). She remains on posaconazole 12 months after initial presentation, with no evidence of recurrence.

Sporothrix is a thermodimorphic fungus found in soil, animal excreta, and vegetation, mainly in subtropical and tropical regions [2]. It is spread primarily in its saprophytic, or hyphal, form through heavy soil exposure, especially via traumatic injuries sustained during outdoor work [2]. In South America, animals have been increasingly appreciated as vectors for S. brasiliensis, 1 species of the Sporothrix complex. In particular, domestic outdoor cats inoculate Sporothirx spp. via scratching [3] and many case reports highlight infection after handling wild armadillos [4].

Sporotrichosis classically presents in a lymphocutaneous pattern with distal to proximal spread from the inoculation site [2]. Typically, disseminated disease occurs in hosts with severe immunocompromise including those with HIV or hematologic malignancies. However, even immunocompetent hosts, especially those with heavy alcohol intake or poorly controlled diabetes, can develop both lymphocutaneous and disseminated disease (Table 1) [5]. Dissemination occurs in ~1% of cases [6], presenting with cutaneous features that include numerous nodules that often ulcerate [7]. Osteoarticular involvement is a common feature of disseminated disease, usually manifesting as large-joint monoarthritis [1]. Diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms mimic other conditions including PG, Sweet's syndrome, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and other mycotic or parasitic infections, including cutaneous leishmaniasis [8]. Indeed, Sporothrix is a common infectious mimicker of PG and can lead to a delay in correct diagnosis, as several case reports have highlighted (Table 2) [9].

Table 1. .

Case Reports of Disseminated Sporotrichosis in Immunocompetent Individuals

| Publication | Location | Age/Sex | Sites Involved | Risk Factor(s) | Treatment Regimen | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campos-Macias et al. (2006) [13] | Japan | 74/M | Skin (multiple sites) Lymph nodes Joints – arthritis, ankylosis, bursitis |

None identified | Itraconazole 400 mg/d × 4 mo, then stopped prematurely Itraconazole 400 mg/d restarted, but taken incorrectly (200 mg/d) |

Final outcome not provided |

| Yap (2011) [14] | Malaysia | 70/F | Skin (multiple sites) Systemic – fevers, night sweats, wt loss |

Gardening Pet cats |

Amphotericin 0.7 mg/kg/d for 2 wk, followed by itraconazole 400 mg/d for 8 mo | Resolution |

| Ribeiro et al. (2015) [15] | Brazil | 5/M | Skin (multiple sites) Joints – polyarthritis |

None identified | Amphotericin (dose unknown) for 2 wk, followed by itraconazole (dose unknown) for 45 d | Resolution |

| Hassan et al. (2016) [6] | USA | 56/M | Skin Joints – bilateral arthritis, bursitis Lungs – pleural effusions Eyes Systemic – fevers, wt loss |

Farmer Alcohol use Type 2 DM |

Liposomal amphotericin 3 mg/kg/d for 1 mo; discharged on itraconazole | Patient lost to follow-up |

| Hessler et al. (2017) [16] | California, USA | CNS – chronic meningitis Lungs Systemic – fevers No skin lesions or joint involvement |

Construction worker | Itraconazole for 12 mo | Resolution |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; DM, diabetes mellitus.

Table 2. .

Case Reports of Disseminated Sporotrichosis Mimicking Pyoderma Gangrenosum, in Addition to Those Reported in Case Series From Byrd et al. (2001) [17] and Weenig et al. (2002) [9]

| Publication | Location | Age/ Sex | Host Features and Risk Factor(s) | Sites Involved | Treatments Received for Suspected PG | Time to Correct Diagnosis | Treatment Regimen | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles et al. (2017) [18] | Michigan, USA | 57/F | Immunocompetent History of obesity, asthma |

Skin (multiple sites) Systemic – fevers, chills, fatigue |

Methylprednisolone, prednisone, clobetasol | 10 mo | Itraconazole 200 mg/d for 3 mo, then 200 mg twice daily due to poor response | Improved Final outcome not stated |

| Lima et al. (2017) [19] | Brazil | 39/F | Immunocompetent Scratched by known sporotrichosis- infected (and untreated) cat |

Skin (multiple sites) Lungs Systemic – sepsis |

Systemic corticosteroids, infliximab (which triggered dissemination) | >24 mo | Liposomal amphotericin 400 mg/d for 6 wk, followed by itraconazole 400 mg/d for 12 mo | Resolution |

| Takazawa et al. (2018) [20] | Japan | 47/M | History of ulcerative colitis on mesalamine | Skin (single site) | Topical steroid ointment | 4 mo | Potassium iodide 500 mg for 2 wk, followed by 1000 mg and local heat therapy for 3 wk | Resolution |

Abbreviations: PG, pyoderma gangreonsum; PMH,

The histopathologic features of granulomatous inflammation with cigar-shaped organisms and asteroid bodies are supportive but have low sensitivity. Culture remains the gold standard but can take up to 7 days to result. Sporothrix grows as mold at lower temperatures (25°C–30°C) and yeast at body temperature. Notably, several dimorphic fungi may grow as yeast forms in aerobic bacterial culture systems at 35°C–37°C, including Sporothrix, Blastomyces, and Histoplasma [10, 11]. Given culture result latency, specific molecular diagnostics to rapidly confirm Sporothrix infections have been studied [10]. In this case, however, broad-range fungal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of skin samples and synovial fluid PCR were negative.

The recommended treatment for disseminated sporotrichosis, regardless of specific manifestation, is liposomal amphotericin 3–5 mg/kg daily until clinical improvement is seen, followed by step-down to oral itraconazole (200 mg twice daily) until resolution [12]. Posaconazole has occasionally been used as salvage therapy [13]. Prognoses are generally good, but up to a year of treatment may be required. Surgical joint debridement is rarely necessary and is ineffective as a monotherapy [12].

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our clinical lab assistant, Gail Cunningham, ASCP, for assistance in confirming the diagnosis and in providing microscopy and culture pictures. We would also like to thank Dr. Tim McCalmont in dermatopathology for his assistance with analyzing the histopathology in this case. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Lindy Fox for her role in caring for this patient.

Financial support. This article has no funding sources. Dr. Weber (co-first author) is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Medical Scientist Training Program (Grant #T32GM007618). Dr. Coates (corresponding and last author) is funded by the National Cancer Institute and the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number D43TW009343, as well as the University of California Global Health Institute (UCGHI).

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UCGHI.

Potential conflicts of interest. Authors L.S., R.W., S.P., E.B., M.P., J.B., A.H., and S.C. have no conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Bayer A, Scott V, Guze L. Fungal arthritis. III. Sporotrichal arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1979; 9:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barros M, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach A. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24:633–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macedo-Sales P, Souto R, Destefani C, et al. . Domestic feline contribution in the transmission of Sporothrix in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil: a comparison between infected and non-infected populations. BMC Vet Res 2018; 14:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alves S, Boettcher C, Oliveira D, et al. . Sporothrix schenckii associated with armadillo hunting in Southern Brazil: epidemiological and antifungal susceptibility profiles. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2010; 43:523–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sanchez A, Paredes-Solis V, et al. . Cutaneous disseminated sporotrichosis: clinical experience of 24 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32:e77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hassan K, Turker T, Zangeneh T. Disseminated sporotrichosis in an immunocompetent patient. Case Reports Plast Surg Hand Surg 2016; 3:44–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He Y, Ma C, Fung M, Fitzmaurice S. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis presenting as a necrotic facial mass: case and review. Dermatol Online J 2017; 23:13030/qt5zd47238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grofino-Costa R, Boia M, Magalhaes G, et al. . Arthritis as a hypersensitivity reaction in a case of sporotrichosis transmitted by a sick cat: clinical and serological follow up of 13 months. Mycoses 2010; 53:81–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weenig R, Davis M, Dahl P, Su W. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:1412–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murray P, Masur H. Current approaches to the diagnosis of bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:3277–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salimnia H, Brown P, Lephart P, Fairfax MR. Hyphal and yeast forms of Histoplasma capsulatum growing within 5 days in an automated bacterial blood culture system . J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:2833–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kauffman C, Bustamante B, Chapman S, Pappas P; Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:1255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bunce PE, Yang L, Chun S, Zhang SX, Trinkaus MA, Matukas LM. Disseminated sporotrichosis in a patient with hairy cell leukemia treated with amphotericin B and posaconazole. Med Mycol 2012; 50:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campos-Macías P, Arenas R, Vega-Memije M, Kawasaki M. Sporothrix schenckii type 3D (mtDNA-RFLP): report of an osteoarticular case. J Dermatol 2006; 33:295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yap FB. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis in an immunocompetent individual. Int J Infect Dis 2011; 15:e727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ribeiro B, Ribeiro R, Penna C, Frota A. Bone involvement by Sporothrix schenckii in an immunocompetent child. Pediatr Radiol 2015; 45:1427–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hessler C, Kauffman CA, Chow FC. The upside of bias: a case of chronic meningitis due to Sporothrix schenckii in an immunocompetent host. Neurohospitalist 2017; 7:30–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Byrd D, El-Azhary R, Gibson L, Roberts G. Sporotrichosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and review of 19 cases of sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15:581–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Charles K, Lowe L, Shuman E, Cha KB. Painful linear ulcers: a case of cutaneous sporotrichosis mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. JAAD Case Rep 2017; 3:519–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lima R, Jeunon-Sousa M, Jeunon T, et al. . Sporotrichosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31:e539–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takazawa M, Harada K, Kakurai M, et al. . Case of pyoderma gangrenosum-like sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix globosa in a patient with ulcerative colitis. J Dermatol 2018; 45:e226–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]