Abstract

Background

Fluid overload prior to continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is an important prognostic factor. Thus, precise evaluation of fluid status is necessary to treat such patients. In this study, we investigated whether fluid assessment using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) can predict outcomes in critically ill patients requiring CRRT.

Methods

A prospective observational study was performed in patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit and who required CRRT. BIA was conducted before CRRT; then, the ratio of extracellular water to total body water (ECW/TBW) was derived to estimate volume status.

Results

A total of 31 patients treated with CRRT were included. There were 18 men (58.1%), and the median age was 67 years (interquartile range, 51 to 78 years). Fourteen patients (45.2%) died within 28 days after CRRT initiation. Patients were divided into 16 with ECW/TBW ≥0.41 and 15 with ECW/TBW <0.41. Survival rate within 28 days was different between the two groups (P = 0.044). Cox regression analysis revealed a relationship between ECW/TBW ≥0.41 and 28-day mortality, but it was not statistically significant (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 0.9 to 9.8; P = 0.061). Lastly, the area under the curve of ECW/TBW for 28-day mortality was analyzed. The area under the curve of ECW/TBW was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.54 to 0.92), and this was significant (P = 0.037).

Conclusions

Fluid status can be assessed using BIA in critically ill patients requiring CRRT, and BIA can predict mortality. Further large trials are needed to confirm the usefulness of BIA in critically ill patients.

Keywords: critical illness, electric impedance, mortality, renal replacement therapy.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU); it is estimated to occur in 30%–50% of admissions [1]. Compared to individuals with stable kidney function, AKI patients have poor outcomes, particularly those receiving renal replacement therapy [1,2]. Among modalities of renal replacement therapy, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) is preferred in the ICU setting because it is best suited for hemodynamically unstable patients with multiple organ failure. Previous studies have investigated the impact of CRRT timing on outcomes, but no significant results were reported [3,4]. In contrast, volume status in AKI patients appears to have significant effects on outcome [5-7]. Fluid accumulation can result in multiple organ failure and death; thus, aggressive volume control using diuretics or renal replacement therapy is suggested in critically ill patients with AKI.

Precise assessment of volume status is necessary to maintain euvolemic status. Approaches such as monitoring changes in body weight or central venous pressure are frequently used, but have poor sensitivity [8,9]. Therefore, researchers have attempted to find an ideal method to determine volume status. Laboratory tests including assessment of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro-BNP levels, which reflect cardiac reactions to volume load, have been used to assess hydration status [10]. However, various studies have challenged the utility of BNP for assessment of volume status and predicting outcomes [11-13]. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is a promising noninvasive and convenient method for assessing volume status [14,15]. Previous studies have suggested that, in hemodialysis patients, volume status management using BIA could be achieved, and blood pressure might be improved [14,15]. Nevertheless, few studies have investigated the usefulness of BIA in critically ill patients, and more data are needed to demonstrate the associations between parameters obtained from BIA and outcomes for clinical application.

In this prospective observational study, we identified AKI patients who required CRRT and evaluated the degree of volume overload as the ratio of extracellular water to total body water (ECW/TBW) obtained from a segmental, multifrequency BIA device, which seems to be more accurate than whole-body BIA [16]. We then investigated the utility of ECW/TBW for predicting outcomes in CRRT patients in comparison with other variables.

Materials and Methods

1) Patients

Patients who needed CRRT for AKI were screened between February and November in 2014 in a 750-bed tertiary referral center in Seoul, Korea. AKI was defined as an abrupt loss of kidney function requiring CRRT that developed within 7 days. The study included adult patients (aged ≥18 years) who were admitted for medical illness. We excluded patients who had received kidney transplantation or who had been treated with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for end-stage renal disease. A total of 73 patients were eligible. Of those, 31 patients were included in the study; 42 patients who did not wish to participate in this study or for whom BIA was not performed were excluded.

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the institutional review board (No. C2012195[890]) of Chung-Ang University Hospital where the study was performed. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible patients or next of kin before enrollment. Because this study was observational, the treatment protocol, including CRRT and medication, was not changed regardless of enrollment.

2) CRRT protocol

CRRT was initiated by decision of the nephrologist if patients who could not bear intermittent hemodialysis due to unstable vital signs, refractory pulmonary edema, intractable hyperkalemia or metabolic acidosis, uremic symptoms including pericarditis and encephalopathy, or oliguria with progressive azotemia. Continuous hemodiafiltration was carried out using a Prisma (Baxter, Lund, Sweden) or Prismaflex machine with a high flux hemofilter (ST100, Baxter) and dialysate and replacement fluids (Hemosol B0, Baxter). Anticoagulation was conducted with nafamostat mesilate (SK Chemicals, Seoul, Korea). The target dose of CRRT was 40 ml/kg/h.

3) Volume status analysis

Body composition was assessed using a segmental and multifrequency BIA device (Inbody S10; Biospace, Seoul, Korea) before CRRT initiation. Eight electrodes were placed on the surface of the thumb, fingers of the hand, and ball of the foot and heel with the patient in the supine position. We collected ECW and TBW data from BIA and then calculated ECW/TBW to estimate the volume status of subjects.

4) Data collection

All data were collected from electronic medical records. Baseline demographic and clinical data included age, sex, comorbidities, causes of admission, reasons for AKI, and CRRT indications. Body weight was measured by a bed scale before conducting BIA and CRRT. Laboratory findings at CRRT initiation included hematocrit, albumin, C-reactive protein, lactate, BNP, and total carbon dioxide (CO2). To calculate the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, related parameters were also collected [17]. All available intake and output data between ICU admission and CRRT initiation were collected. Intake was composed of oral and parenteral fluid administered, and output included urine, gastrointestinal losses, and drains. Using these data, cumulative and daily fluid balance was calculated from ICU admission to CRRT initiation. Oliguria was defined if urine output for 24 hours before CRRT was under 400 ml/d.

5) Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range) and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage) and were compared between groups using the chi-square test. To investigate whether volume status can influence outcomes, patients were divided into two groups using an ECW/TBW of 0.41 as the cutpoint, which was the approximate median value. Cumulative incidence of death from initiation of CRRT was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and was compared between groups using the log-rank test. Cox regression analyses were conducted to investigate the associations between variables and mortality. In addition, we evaluated the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for predicting mortality and determined the area under the curve (AUC). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

1) Baseline characteristics

A total of 31 ICU patients receiving CRRT were analyzed in this study. There were 18 men (58.1%), and the median age was 67 years (interquartile range, 51 to 78 years). Of the included patients, 14 (45.2%) died within 28 days after CRRT initiation. We compared characteristics between 17 survivors and 14 non-survivors to determine factors associated with mortality (Table 1). There were no differences in age, sex, comorbidities, causes of admission, etiologies of AKI, or CRRT indications between these two groups. Total SOFA score, daily fluid balance, and serum albumin level differed between survivors and non-survivors (P = 0.040, P = 0.048, and P = 0.007, respectively). In addition, ECW/TBW was lower in survivors than in non-survivors (0.40; interquartile range, 0.40 to 0.42 vs. 0.42; interquartile range, 0.41 to 0.44; P = 0.044).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of AKI patients who received CRRT

| Variable | Survivor (n = 17) | Non-survivor (n = 14) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 67 (42–78) | 69 (53–79) | 0.653 |

| Male | 10 (58.8) | 8 (57.1) | 0.925 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 7 (41.2) | 4 (28.6) | 0.707 |

| Diabetes | 6 (35.3) | 7 (50.0) | 0.409 |

| Liver disease | 3 (17.6) | 4 (28.6) | 0.671 |

| Heart failure | 3 (17.6) | 2 (14.3) | 1.000 |

| Reason for admission | 0.560 | ||

| Infection | 9 (52.9) | 9 (64.3) | |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (11.8) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (23.5) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Others | 2 (11.8) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Duration from ICU to CRRT (d) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (1–3) | 0.246 |

| Cause of AKIa | 0.603 | ||

| Septic | 9 (52.9) | 9 (64.3) | |

| Cardiorenal | 1 (5.9) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Ischemic | 4 (23.5) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Hepatorenal | 2 (11.8) | 0 | |

| Others | 1 (5.9) | 1 (7.1) | |

| CRRT indication | |||

| Pulmonary edema | 8 (47.1) | 8 (57.1) | 0.576 |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 (17.6) | 4 (28.6) | 0.671 |

| Metabolic acidosis | 7 (41.2) | 8 (57.1) | 0.376 |

| Uremic symptom | 6 (35.3) | 5 (35.7) | 0.981 |

| SOFA score | |||

| Respiratory | 3 (2–3) | 3 (3–3) | 0.518 |

| Cardiovascular | 3 (0–4) | 3 (1–4) | 0.421 |

| Nervous | 2 (1–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.026 |

| Liver | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.493 |

| Coagulation | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.518 |

| Renal | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.186 |

| Total | 11 (8–13) | 14 (11–15) | 0.040 |

| Oliguria (<400 ml/d) | 9 (52.9) | 10 (71.4) | 0.461 |

| Daily fluid balance (L/d) | 1.3 (0.4–2.9) | 2.3 (1.8–3.7) | 0.048 |

| Cumulative fluid balance (L) | 2.2 (0.5–5.1) | 5.9 (4.3–7.5) | 0.008 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 31.1 (24.1–41.3) | 28.8 (26.4–33.6) | 0.769 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 2.9 (2.6–3.5) | 2.3 (2.1–2.8) | 0.007 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 129.0 (64.6–151.4) | 129.1 (67.0–216.0) | 0.681 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.8 (1.0–5.2) | 3.0 (2.1–8.4) | 0.053 |

| BNP (pg/ml) | 122.5 (75.5–830.7) | 570.4 (130.3–807.6) | 0.201 |

| Total CO2 (mmol/L) | 15.5 (12.1–20.5) | 13.9 (10.7–17.0) | 0.316 |

| ECW/TBW | 0.40 (0.40–0.42) | 0.42 (0.41–0.44) | 0.044 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

AKI: acute kidney injury; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; ICU: intensive care unit; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; CRP: C-reactive protein; BNP: brain natriuretic protein; CO2: carbon dioxide; ECW/TBW: the ratio of extracellular water to total body water.

AKI refers to an abrupt loss of kidney function requiring CRRT that develops within 7 days.

2) Relationship between BIA-assessed volume status and mortality

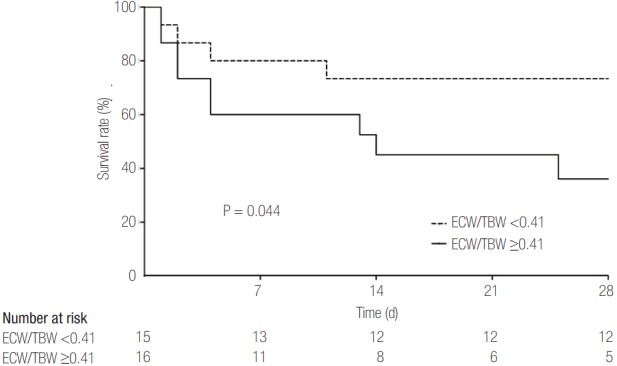

Survival rate was compared between the two groups. Figure 1 shows the results of survival analysis. As shown, less hydrated patients had a better survival rate than the more hydrated patients (P = 0.044). The 28-day survival rate was 73.3% in patients with ECW/TBW <0.41 and 36.0% in those with ECW/TBW ≥0.41.

Figure 1.

Survival rate according to volume status in critically ill patients who received continuous renal replacement therapy. Survival rate was compared between the two groups. As shown, patients with ECW/TBW ≥0.41 had a lower survival rate than those with ECW/ TBW <0.41 (P = 0.044). Survival rate after 28 days was 73.3% in less hydrated patients and 36.0% in more hydrated patients. ECW/ TBW: the ratio of extracellular water to total body water.

To determine the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality, several variables, including ECW/TBW, were analyzed by Cox regression analysis (Table 2). Age, sex, and oliguria were not associated with mortality (P = 0.577, P = 0.810, and P = 0.440, respectively). Total SOFA score and daily fluid balance were also not related to mortality, despite weak associations (HR, 1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0 to 1.6; P = 0.079 and HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.7; P = 0.072). Serum level of lactate and BNP at the time of CRRT initiation did not predict mortality (P = 0.060 and P = 0.331, respectively). Patients with ECW/TBW ≥0.41 had decreased survival rates, but the difference was not statistically significant (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 0.9 to 9.8; P = 0.061).

Table 2.

HRs for 28-day mortality in AKI patients who received CRRT

| Variable | HR (95% confidence interval) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.577 |

| Sex | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 0.810 |

| SOFA | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 0.079 |

| Daily fluid balance | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.072 |

| Lactate | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.060 |

| BNP (>500 pg/ml) | 1.7 (0.6–4.9) | 0.331 |

| ECW/TBW (≥0.41) | 3.0 (0.9–9.8) | 0.061 |

HR: hazard ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; BNP: brain natriuretic protein; ECW/TBW: the ratio of extracellular water to total body water.

3) Using ECW/TBW to predict mortality

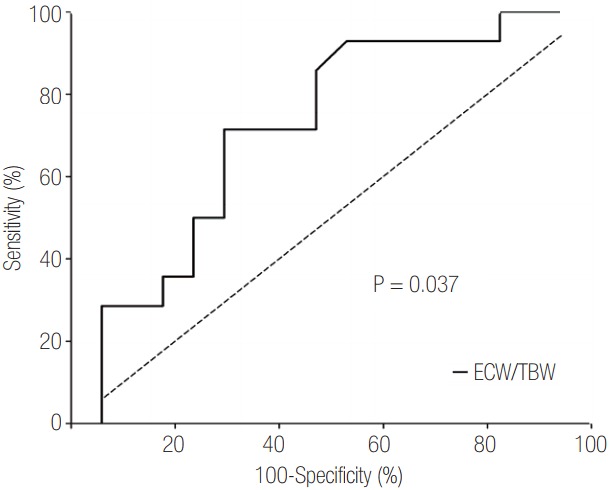

We evaluated the ROC curve to identify variables that predicted mortality. Among various factors, total SOFA score, daily fluid balance, and serum level of lactate predicted mortality. The AUC of these was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.92; P = 0.039), 0.75 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.93; P = 0.025), and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.57 to 0.93; P = 0.024), respectively. In addition, the ROC of ECW/TBW at the time of CRRT initiation was estimated (Figure 2). The AUC of ECW/TBW was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.54 to 0.92) for mortality (P = 0.037). An optimal cutoff was 0.413, which showed a sensitivity and specificity of 71.4% and 70.6%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics curve of volume status estimated by bioelectrical impedance analysis. ECW/TBW appeared to have the potential to predict mortality (P = 0.037). The area under the curve of ECW/TBW for 28-day mortality was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.54 to 0.92) in this study. ECW/ TBW: the ratio of extracellular water to total body water.

Discussion

In this prospective observational study, we investigated the utility of using BIA to assess volume status as the ratio of ECW/TBW in critically ill patients receiving CRRT. Non-survivors had a relatively higher ECW/TBW than survivors. In addition, we evaluated the ability of ECW/TBW to predict mortality, and patients who had a higher ECW/TBW had increased risk of 28-day death, and the HR for death was considerable (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 0.9 to 9.8), albeit without statistical significance. Last, we explored the ROC curve and found that the AUC of ECW/TBW was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.54 to 0.92) for predicting 28-day mortality in patients receiving CRRT.

Fluid accumulation has been identified as an independent risk factor for death in patients with AKI [5,6,18,19]. Furthermore, a previous study showed that an excessively positive fluid balance prior to CRRT can result in organ failure and death in critically ill patients who receive CRRT [7]. Volume status needs to be monitored before deciding on fluid therapy. However, isotope dilution, the gold-standard method to determine volume status, is difficult to perform in clinical practice [20]. In addition, traditional clinical approaches such as monitoring body weight or central venous pressure are known to have poor sensitivity [8,9]. This study comprised 22 patients whose central venous pressure was measured, but we found that these values did not predict mortality in the ROC curve (AUC, 0.72; P = 0.082). Fluid balance between the input and output is widely used in practice. Although this study again confirmed that fluid balance was associated with mortality, an assessment of fluid balance using input and output data could be incorrect, especially in ICU patients [21,22]. Thus, various other methods have been explored. Level of BNP has been used to assess volume status [10], but previous reports found that BNP level did not predict outcomes [11-13], similar to our findings. BIA is a promising method to assess fluid status because it allows analysis of body composition and has the advantages of safety, convenience, noninvasiveness, and low cost [14,15,23-25]. Nevertheless, its role in critically ill patients has not been widely explored [26,27]. In this study, we investigated the utility of BIA to assess volume status in AKI patients who receive CRRT.

The principle underlying BIA is the analysis of the vectors of resistance and reactance resulting from the passage of electric currents of low amplitude and low and high frequencies through an organism [28,29]. Several parameters including intracellular water, ECW, and TBW are derived from analysis of these resistance and reactance vectors. ECW/TBW is a simple-to-measure, straightforward parameter that allows determination of the degree of hydration because excess volume accumulates primarily as ECW [30]. The present study randomly used the approximate median value, ECW/TBW of 0.41, as the cutoff point to divide patients into two groups. Although the comparisons according to the ECW/TBW showed significant differences, this ratio is not an absolute cutoff for defining volume overload because it can be affected by various factors including age, sex, and comorbidities [20,30]. Given this problem, further studies are needed to establish an optimal cutoff value for diagnosing volume overload in ICU patients.

We investigated whether volume status assessed by BIA could predict mortality. We evaluated the time to 28-day mortality and found worse outcomes in more hydrated patients compared to less hydrated patients. That is, fluid balance before CRRT initiation might be better in patients with lower ECW/TBW than those with higher ECW/TBW, which could determine the results, although CRRT indications such as pulmonary edema did not differ. However, Cox regression analysis did not show a relationship between higher ECW/TBW and higher mortality due to small sample size, although it trended in the predicted direction. Additionally, we drew an ROC curve and obtained a significant AUC of ECW/TBW for predicting mortality. This result also shows that the ratio might be comparable to daily fluid balance, SOFA score, and serum lactate level which are known as predictors for mortality [6,7,18,31,32], although interactions could occur. Previous studies have investigated the usefulness of BIA in critically ill patients with or without AKI and have suggested that BIA can be a reliable method to determine fluid status and to predict outcomes [33-35]. However, these studies used whole-body BIA devices to estimate volume status. The present study investigated the usefulness of a segmental, multifrequency BIA device, which seems to be more accurate than whole-body BIA [16]. In addition to those studies, our study added the potentials of a segmental, multifrequency BIA for determining fluid status and predicting outcomes in CRRT patients. To confirm the utility of ECW/TBW, further large studies are required in ICU patients.

This study has several limitations. First, our small sample size limited our statistical power. Although we observed trends in the data in the direction expected, some results were not statistically significant. Furthermore, we could not perform multivariate analyses because of our small sample size. Some variables such as SOFA score and serum lactate could be confounders of mortality but could not be assessed here. Second, this study was observational; thus, we did not adjust fluid balance according to the BIA results. To determine if BIA-guided adjustment of volume status can improve outcomes in ICU patients, further controlled trials with large sample sizes are necessary.

In conclusion, this prospective observational study investigated the utility of BIA-measured volume status in critically ill patients who received CRRT due to AKI in order to predict mortality. Our results suggest that hydration status can be determined using BIA, and that overhydration at the time of CRRT might be a predictor of mortality. Because of the small sample size and observational characteristics of this study, future trials are needed to confirm the usefulness of BIA in ICU patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (No. NRF- 2012R1A1A1011816) funded by the Korean government, and a grant from Baxter, Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. This work was supported by a grant from Baxter, Korea. The funders had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of this study.

References

- 1.Hoste EA, Schurgers M. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury: how big is the problem? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4 Suppl):S146–51. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168c590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Moreira S, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu KD, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, Ikizler TA, Soroko SH, Mehta RL, et al. Timing of initiation of dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:915–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, Martin-Lefevre L, Pons B, Boulet E, et al. Initiation strategies for renalreplacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard J, Soroko SB, Chertow GM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Paganini EP, et al. Fluid accumulation, survival and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2009;76:422–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RENAL Replacement Therapy Study Investigators. Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, et al. An observational study fluid balance and patient outcomes in the randomized evaluation of normal vs. augmented level of replacement therapy trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1753–60. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246b9c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han MJ, Park KH, Shin JH, Kim SH. Influence of daily fluid balance prior to continuous renal replacement therapy on outcomes in critically ill patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1337–44. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dou Y, Zhu F, Kotanko P. Assessment of extracellular fluid volume and fluid status in hemodialysis patients: current status and technical advances. Semin Dial. 2012;25:377–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2012.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marik PE, Cavallazzi R. Does the central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? An updated meta-analysis and a plea for some common sense. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1774–81. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a25fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arjamaa O. Physiology of natriuretic peptides: the volume overload hypothesis revisited. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:4–7. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levitt JE, Vinayak AG, Gehlbach BK, Pohlman A, Van Cleve W, Hall JB, et al. Diagnostic utility of Btype natriuretic peptide in critically ill patients with pulmonary edema: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R3. doi: 10.1186/cc6764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeder MT, Rickenbacher P, Rickli H, Abbühl H, Gutmann M, Erne P, et al. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide-guided management in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: findings from the trial of intensified versus standard medical therapy in elderly patients with congestive heart failure (TIME-CHF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1148–56. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papanikolaou J, Makris D, Mpaka M, Palli E, Zygoulis P, Zakynthinos E. New insights into the mechanisms involved in B-type natriuretic peptide elevation and its prognostic value in septic patients. Crit Care. 2014;18:R94. doi: 10.1186/cc13864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamney PW, Krämer M, Rode C, Kleinekofort W, Wizemann V. A new technique for establishing dry weight in hemodialysis patients via whole body bioimpedance. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2250–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wabel P, Chamney P, Moissl U, Jirka T. Importance of whole-body bioimpedance spectroscopy for the management of fluid balance. Blood Purif. 2009;27:75–80. doi: 10.1159/000167013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gómez J, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1430–53. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study: working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Payen D, de Pont AC, Sakr Y, Spies C, Reinhart K, Vincent JL, et al. A positive fluid balance is associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute renal failure. Crit Care. 2008;12:R74. doi: 10.1186/cc6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glassford NJ, Bellomo R. The complexities of intravenous fluid research: questions of scale, volume, and accumulation. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2016;31:276–99. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan C, McIntyre C, Smith D, Spanel P, Davies SJ. Combining near-subject absolute and relative measures of longitudinal hydration in hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1791–8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02510409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos AN, Westendorp RG, Frölich M, Meinders AE. Weight changes in critically ill patients evaluated by fluid balances and impedance measurements. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:871–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199306000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perren A, Markmann M, Merlani G, Marone C, Merlani P. Fluid balance in critically ill patients. Should we really rely on it? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:802–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piccoli A. Identification of operational clues to dry weight prescription in hemodialysis using bioimpedance vector analysis. The Italian Hemodialysis-Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (HD-BIA) study group. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1036–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nescolarde L, Piccoli A, Román A, Núñez A, Morales R, Tamayo J, et al. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in haemodialysis patients: relation between oedema and mortality. Physiol Meas. 2004;25:1271–80. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/5/016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin JH, Kim CR, Hong M, Kim SH, Yu SH. Influences of dry weight adjustment based on bioimpedance analysis on ambulatory blood pressure in hemodialysis patients. J Korean Soc Hypertens. 2012;18:166–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roos AN, Westendorp RG, Brand R, Souverijn JH, Frölich M, Meinders AE. Predictive value of tetrapolar body impedance measurements for hydration status in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:125–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01726535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley K, Keegan M, Campbell I, Murby B, Hancox D, Pollard B. Use of single-frequency bioimpedance at 50 kHz to estimate total body water in patients with multiple organ failure and fluid overload. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1472–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukaski HC, Johnson PE, Bolonchuk WW, Lykken GI. Assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance measurements of the human body. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;41:810–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthie JR. Bioimpedance measurements of human body composition: critical analysis and outlook. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5:239–61. doi: 10.1586/17434440.5.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopot F, Nejedlý B, Novotná H, Macková M, Sulková S. Age-related extracellular to total body water volume ratio (Ecv/TBW): can it be used for “dry weight” determination in dialysis patients? Application of multifrequency bioimpedance measurement. Int J Artif Organs. 2002;25:762–9. doi: 10.1177/039139880202500803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1754–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Woodward R, Mulder PG, Bakker J. Association between blood lactate levels, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment subscores, and 28-day mortality during early and late intensive care unit stay: a retrospective observational study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2369–74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a0f919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones SL, Tanaka A, Eastwood GM, Young H, Peck L, Bellomo R, et al. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in critically ill patients: a prospective, clinician- blinded investigation. Crit Care. 2015;19:290. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1009-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Wu B, Gong D, Liu Z. Fluid overload at start of continuous renal replacement therapy is associated with poorer clinical condition and outcome: a prospective observational study on the combined use of bioimpedance vector analysis and serum Nterminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide measurement. Crit Care. 2015;19:135. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0871-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samoni S, Vigo V, Reséndiz LI, Villa G, De Rosa S, Nalesso F, et al. Impact of hyperhydration on the mortality risk in critically ill patients admitted in intensive care units: comparison between bioelectrical impedance vector analysis and cumulative fluid balance recording. Crit Care. 2016;20:95. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]