Abstract

From early in life, children help, comfort, and share with others. Recent research has deepened scientific understanding of the development of prosociality – efforts to promote the welfare of others. This article discusses two key insights about the emergence and early development of prosocial behavior, focusing on the development of helping. First, children’s motivations and capabilities for helping change in quality as well as quantity over the opening years of life. Specifically, helping begins in participatory activities without prosocial intent in the first year of life, becoming increasingly autonomous and motivated by prosocial intent over the second year. Second, helping emerges through bidirectional social interactions, starting at birth, in which caregivers and others support the development of helping in a variety of ways and young children play active roles, often influencing caregiver behavior. The question now is not whether, but how social interactions contribute to the development of prosocial behavior. Recent methodological and theoretical advances provide exciting avenues for future research on the social and emotional origins of human prosociality.

Keywords: PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR, HELPING, INFANCY, DEVELOPMENT, SOCIALIZATION

After months of eliciting help from caregivers, infants begin to return the favor. By the first birthday, infants share toys and food with parents and can help in simple tasks such as handing back an object that has dropped out of an adult’s reach (Dahl, 2015; Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). During the subsequent months, infants become increasingly helpful in the lab and at home (Dahl, 2015; Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010; Waugh & Brownell, 2017), more likely to comfort others in distress (Svetlova et al., 2010; Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, Wagner, & Chapman, 1992), and more frequently and willingly share toys or food with a needy other (Brownell, Iesue, Nichols, & Svetlova, 2013) . These developments ground the emergence of prosocial actions – actions motivated by a concern with the welfare of others. What explains this remarkable transformation, from helpless neonates to helpful toddlers, forging the foundations of human prosociality?

One explanation is that helping, sharing, and comforting behaviors develop through everyday social interactions from birth: Without active participation in social activities, along with encouragement, demonstration, and other guidance from caregivers, infant helping would not emerge (Brownell & The Early Social Development Research Lab, 2016; Dahl, 2018b). An alternative view is that social experiences are not essential to the emergence of human prosociality, but operate on top of an inherent altruistic motive to promote the welfare of others. According to this second view infants begin to help irrespective of what parents do. Once children have begun to help, parents may influence when and how often they do so, but they do not contribute to the basic skills and motives underlying prosociality (Warneken, 2016).

Research in the past decade has yielded new insights about how parent-child interactions influence the origins of prosociality, challenging theories that grant limited roles to parents – or to children. This article centers on two important insights about how prosocial behavior emerges over the first two years of life, and the social contributions to its precursors and early development. We focus on infant helping to illustrate, as it is currently the most studied. First, prosocial behaviors are qualitatively transformed during the early years: Older children do not merely help more often, but do so from different motives, as well as in more complex ways and in more challenging situations. Children’s motives for helping transition from social motives to participate in interactions, in the first year of life, to prosocial motives to promote others’ welfare, emergent over the second year. The second insight is that infants’ helping acts emerge amid rich, affectively positive social experiences involving participation in games, chores, and other cooperative activities with caregivers and others, as shown by naturalistic research. Furthermore, experimental evidence demonstrates that social experiences causally influence infant helping from its developmental onset. Critically, these everyday interactions are bidirectional: Infants are not passively socialized by adults, but instead play active roles, eagerly participating in social exchanges and eliciting support and guidance from caregivers geared to infants’ level of competence.

Understanding how prosociality emerges and develops is relevant well beyond the theoretical debates of developmental psychology. By middle childhood, humans help, comfort, and share with others in ways that set us apart from other animals (Tomasello, 2014). Moreover, children and adults reason about prosocial actions, sometimes deeming prosocial acts obligatory (e.g. saving someone’s life) and other times deeming them wrong (e.g. helping someone steal) (see Dahl & Paulus, in press). If humans did not develop these orientations toward prosocial actions, our societies would be unrecognizable (Tomasello, 2014). Knowledge about how social interactions influence the development of prosocial behavior has implications for parenting practices – does parental encouragement matter, or is it detrimental? – and interventions aimed at increasing children’s prosociality.

Prosocial Behavior is Transformed over the Early Years

Despite behavioral similarities between infant and adult helping, there are profound psychological differences (Dahl & Paulus, in press; Hammond & Brownell, 2018; Hay & Cook, 2007). Here, we focus on age differences in motivations for helping over the first three years. We draw a distinction between prosocial motives, which are motives to promote the welfare of others, and other social motives, such as motives to engage in social interactions. We and other scholars have proposed that infants’ earliest acts of helping, emerging in the first year, stem from a motivation to engage with others rather than a prosocial motive to promote others’ welfare (Brownell & The Early Social Development Research Lab, 2016; Dahl, 2015; Dahl & Paulus, in press; Hammond & Brownell, 2018; Malti & Dys, 2018; Waugh, Brownell, & Pollock, 2015). For example, for an 11-month-old, the motivation for helping a caregiver put toys away likely resembles the motivation for putting shapes into a shape-sorter: Both activities provide opportunities to engage in a positive, reciprocal interaction with an adult. From this perspective, infants’ first acts of helping are not yet prosocial but instead developmental precursors of prosocial behaviors.

The first major developmental transformation in helping is from participatory acts without prosocial intent, evident by the first birthday, to acts motivated by prosocial intent, evident by the second birthday. Around the first birthday, infants help only during social interactions with others that in most ways resemble playful interactions, such as give-and-take games with objects (Carpendale, Kettner, & Audet, 2015). Later in the second year, as infants begin to help more autonomously, they still help at their own leisure, at little cost or inconvenience, and often without evidencing prosocial intent (Rheingold, 1982). Correspondingly, their helping is not very reliable. For example, 18-month-olds help on about half of laboratory trials, often opting to play or observe instead of helping an adult (Waugh & Brownell, 2017). By comparison, 30-month-olds are less likely to engage in unhelpful behaviors and far more likely to help.

Older toddlers not only engage in prosocial acts more readily, they also do so more autonomously, with less overt prompting, support, and encouragement from adults (Brownell, Iesue, et al., 2013; Brownell, Svetlova, & Nichols, 2009; Nichols, Svetlova, & Brownell, 2015; Svetlova et al., 2010). By age two, children sometimes help even before recipients have realized that they need help (Warneken, 2013) and appear concerned that others receive help regardless of who provides the help (Hepach, Vaish, & Tomasello, 2012). Indeed, from one to four years, parents increasingly attribute concerns with others’ welfare as motives for their children’s helping (Hammond & Brownell, 2018). This motive for prosocial behavior becomes more prominent as children develop more advanced social and emotional understanding (Brownell, Nichols, & Svetlova, 2013; Nichols, Svetlova, & Brownell, 2009).

A second major developmental transformation occurs in the third year of life, as children acquire another new motive for helping: moral judgments about whether one should help, based on considerations such as others’ welfare or known norms (Dahl & Paulus, in press). In simple situations, for instance helping someone who is hurt at little cost to oneself, most preschoolers judge that people should help (Dahl, 2018a). However, like adults, children are less likely to judge helping as okay if the recipient of the helpful act is trying to steal something (for discussion, see Dahl & Paulus, in press). Such moral considerations about right and wrong do not motivate prosocial behavior in infants and toddlers.

Helping Develops Through Social Interactions

Human infants are “ultrasocial” (Brownell & The Early Social Development Research Lab, 2016; Tomasello, 2014), which creates unique mechanisms of developmental change (Brownell, 2011). Importantly, it means that from birth infants are especially open to learning through social exchange, and that they themselves are actively engaged both socially and emotionally during routine interactions and caregiving. Although interactions involving peers or siblings also matter for the development of helping, perhaps especially for coming to understand others’ needs (Zerwas, Balaraman, & Brownell, 2004), we focus on interactions with adult caregivers, which are central early on (Brownell, 2011). In the first months of life, caregivers respond to infants’ initiatives by feeding, comforting, dressing, transporting, and playing with them (Brownell, 2011; Richards & Bernal, 1972).2 At the same time, infants attune to caregiving behaviors in ways that many parents consider helpful (Hammond, Al-Jbouri, Edwards, & Feltham, 2017). For instance, by three months of age they adjust their posture to anticipate being picked up (Reddy, Markova, & Wallot, 2013). In the second half of the first year, infants begin to participate as adults dress or bathe them, clean off surfaces, put toys away, and retrieve objects (Carpendale et al., 2015; Dahl, 2015; Hammond et al., 2017), and they begin to share toys and food with caregivers (see Hay & Cook, 2007).

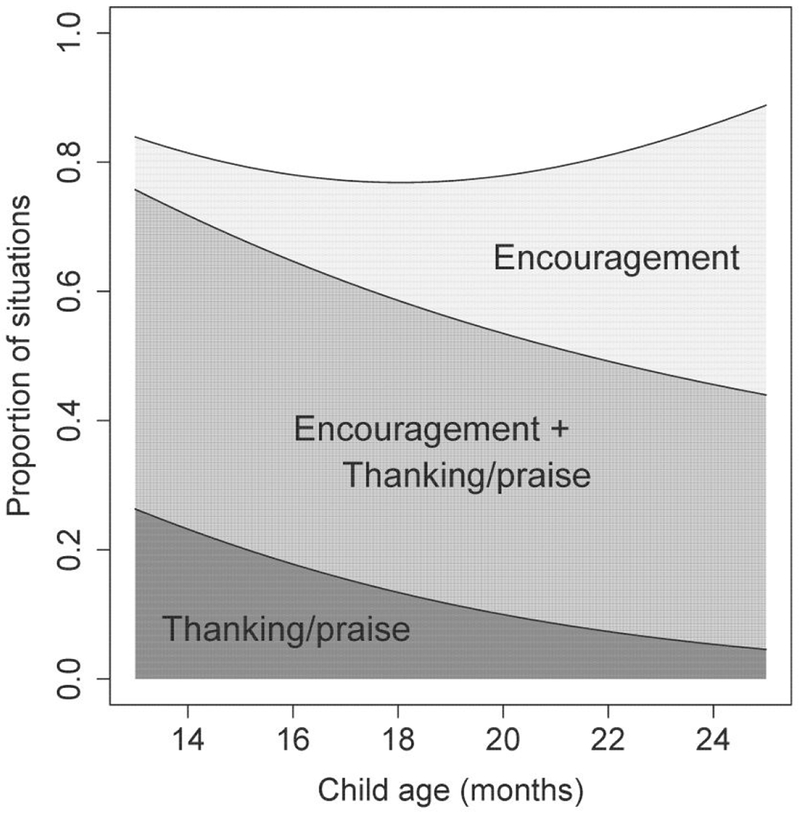

Positive affect and encouragement co-occur with infants’ participation in early helping routines, supporting and maintaining helpful activities. From the beginning, infants’ participation in everyday caregiving activities, and later their efforts to help others, are scaffolded by others, that is, complemented, encouraged, guided, and praised (Figure 1, Dahl, 2015; Pettygrove, Hammond, Karahuta, Waugh, & Brownell, 2013; Waugh et al., 2015). According to parental reports, infants who helped because it was fun were more likely to try to join in helping activities than infants who helped to get a reward. As a result of their social experiences, by the first birthday, most infants eagerly help and share with others well before they possess prosocial motives.

Figure 1.

Encouragement and thanking/praise of infant helping in everyday life (data from Dahl, 2015). The figure shows the proportions of infant helping situations in which caregivers either encouraged or thanked/praised infant helping as a function of infant age.

Positive adult support has been shown to causally influence infants’ helping. In one experiment, infants were randomly assigned to receive either repeated encouragement and praise for helping or no encouragement and praise (Dahl et al., 2017). Infants then saw an adult accidentally drop a pen or other needed object on the floor and unsuccessfully reach for it. Among 13- and 14-month-olds, previous encouragement and praise made infants twice as likely to hand back the dropped object to the experimenter. Other research has provided further evidence about how caregivers contribute to the early development of infant helping (Pettygrove et al., 2013; Waugh et al., 2015), identifying mechanisms such as parent emotion talk (Brownell, Svetlova, Anderson, Nichols, & Drummond, 2013), synchrony and shared positive affect (Cirelli, Wan, & Trainor, 2014), and imitation (Schuhmacher, Köster, & Kärtner, 2018).

Crucially, no developmental transition can be attributed solely to the actions of parents; parents do not “put” prosocial motives or skills in passively receptive children. Instead, children also influence their parents (Kuczynski, Parkin, & Pitman, 2014). For example, children’s actions elicit positive or corrective feedback from parents, which in turn guides children’s behavior (Dahl, 2015; Dahl et al., 2017). Recent research has deepened our knowledge of how children elicit and influence caregiver behaviors related to prosocial behavior. Naturalistic research in the first year shows that helping commonly begins when infants are watching what adults are doing, whereupon adults encourage and assist them in joining the activity (Dahl, 2018a). Parents do not insist that infants participate in helping activities (Waugh et al., 2015), but rather support their participation when infants demonstrate interest. Over the second year, infants increasingly initiate helpful acts themselves, for example trying to help parents with household chores; in turn, parents encourage and support such active efforts even though they are often unhelpful (Hammond & Brownell, 2018).

How adults support early prosocial behavior depends on children’s developmental level. For example, parents adapt their communication about helping to changes in infants’ social abilities; as infants’ social understanding and communication skills improve, parents point more and use more verbal messages to convey their intentions and expectations about helpful behavior (Liszkowski, 2018; Waugh et al., 2015). Praise and thanking for helping become less common during the second year (Dahl, 2015), possibly because caregivers begin to expect infants to help or because infants’ eager “helping” actually makes chores take longer (Hammond & Brownell, 2018; Rheingold, 1982). More subtle or abstract forms of parental guidance, such as references to needs, may become more influential as children become more skilled helpers during the subsequent years (Hammond & Carpendale, 2015; Waugh, et al., 2015), building on the precursors and early forms of prosociality developed in infancy.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The past decade has yielded key insights into how prosocial behaviors emerge and develop early in life. First, the psychological underpinnings of prosocial behavior change over the early years. While helpful acts emerge in the latter half of the first year, these early acts are not motivated by concern for others’ welfare. Rather, they occur during supported, affectively positive social interaction and caregiving activities, serving social motives. Concern for others’ welfare develops over the second and third years of life and begins to motivate helping, comforting, and sharing, transforming such acts into truly prosocial behavior intended to benefit others (Dahl & Paulus, in press). Later, evaluative judgments about whether it is right or wrong to help provide additional motives for prosocial behavior.

Second, it has become clear that infants’ interactions with parents contribute to the earliest developments in helping. Starting long before infants begin trying to help, parents guide and encourage their involvement in everyday activities in ways that support and promote the emergence of helping behavior. Moreover, interactions surrounding helping are bidirectional: Infants influence caregiver behaviors, for instance by showing interest in or understanding of caregiver activities and social signals. Caregivers respond to such infant behaviors by encouraging infant involvement, and their guidance of helping activities changes as infants become more skilled and knowledgeable. From this perspective, human infants’ unique social environments, coupled with infants’ own unique sociality, can account for the appearance of prosocial behavior early in life. Contrary to some accounts, we propose that infants are not inherently prosocial, but gradually develop prosocial motives through various types of bidirectional interactions in the first two years of life.

Current and past research provides exciting avenues for future research on the development of prosocial behavior. Recognizing that development involves continuous coaction across genetic, neural, behavioral, and environmental levels, and that “genetic and nongenetic factors cannot be meaningfully partitioned when accounting for developmental outcomes.” (Lickliter & Honeycutt, 2010, p. 37), many researchers now agree that social interactions are central to the emergence and development of prosocial behaviors. This recognition compels the field to move past the question of whether social interactions contribute to prosocial development to ask how social interactions contribute, starting at birth and continuing across the lifespan (Brownell & The Early Social Development Research Lab, 2016; Dahl, 2018b). That is, we must better understand the many varied and subtle forms of infant social experiences that support the emergence of prosocial behavior, together with how infants contribute to those experiences and learn from them. New technology has made this more feasible, for example, by providing video recording tools for naturalistic investigations of everyday interactions, and physiological and neurological techniques for studying the processes underlying the precursors and early forms of prosocial behavior (see e.g. Dahl, 2018b). By combining methodological and theoretical advances, in both homes and laboratories, researchers will generate new insights into how social interactions forge the development of human prosociality.

Footnotes

Related caregiving behaviors are also seen among other primates, who sometimes hand food to their infants or demonstrate skills that are repeated by infants (e.g. Ueno & Matsuzawa, 2004). Still, human adults scaffold infant helping and other prosocial behaviors (e.g., sharing) far more extensively, and in qualitatively different ways (e.g. using language), than do any other primates.

Contributor Information

Audun Dahl, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Celia A. Brownell, University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Brownell CA (2011). Early developments in joint action. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 2(2), 193–211. 10.1007/s13164-011-0056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Iesue SS, Nichols SR, & Svetlova M (2013). Mine or yours? Development of sharing in toddlers in relation to ownership understanding. Child Development, 84(3), 906–920. 10.1111/cdev.12009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Nichols SR, & Svetlova M (2013). Converging developments in prosocial behavior and self-other understanding in the second year of life In Banajee M & Gelman S (Eds.), Navigating the social world: What infants, children, and other species can teach us (pp. 385–390). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Svetlova M, Anderson R, Nichols SR, & Drummond J (2013). Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parents’ talk about emotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy, 18(1), 91–119. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00125.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Svetlova M, & Nichols S (2009). To share or not to share: When do toddlers respond to another’s needs? Infancy, 14(1), 117–130. 10.1080/15250000802569868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, & The Early Social Development Research Lab. (2016). Prosocial behavior in infancy: The role of socialization. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 222–227. 10.1111/cdep.12189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale JIM, Kettner VA, & Audet KN (2015). On the nature of toddlers’ helping: Helping or interest in others’ activity? Social Development, 24(2), 357–366. 10.1111/sode.12094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli LK, Wan SJ, & Trainor LJ (2014). Fourteen-month-old infants use interpersonal synchrony as a cue to direct helpfulness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1658), 20130400–20130400. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (2015). The developing social context of infant helping in two U.S. samples. Child Development, 86(4), 1080–1093. 10.1111/cdev.12361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (2018a). A moral-developmental perspective on early prosociality Presented at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (2018b). How, not whether: contributions of others in the development of infant helping. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 72–76. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Paulus M (in press). From interest to obligation: The gradual development of human altruism. Child Development Perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Satlof-Bedrick ES, Hammond SI, Drummond JK, Waugh WE, & Brownell CA (2017). Explicit scaffolding increases simple helping in younger infants. Developmental Psychology, 53(3), 407–416. 10.1037/dev0000244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Lennon R, & Roth K (1983). Prosocial development: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 19(6), 846–855. 10.1037/0012-1649.19.6.846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, Al-Jbouri E, Edwards V, & Feltham LE (2017). Infant helping in the first year of life: Parents’ recollection of infants’ earliest prosocial behaviors. Infant Behavior and Development, 47, 54–57. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, & Brownell CA (in press). Happily unhelpful: Infants’ everyday helping and its connections to early prosocial development. Frontiers in Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, & Brownell CA (2018). Happily unhelpful: Infants’ everyday helping and its connections to early prosocial development. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, & Carpendale JIM (2015). Helping children help: The relation between maternal scaffolding and children’s early help: helping children help. Social Development, 24, 367–383. 10.1111/sode.12104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, & Cook KV (2007). The transformation of prosocial behavior from infancy to childhood In Brownell CA & Kopp CB (Eds.), Socioemotional Development in the Toddler Years (pp. 100–131). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hepach R, Vaish A, & Tomasello M (2012). Young children are intrinsically motivated to see others helped. Psychological Science, 23(9), 967–972. 10.1177/0956797612440571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Parkin CM, & Pitman R (2014). Socialization as dynamic process: A dialectical, transactional perspective In Grusec JE & Hastings PD (Eds.), Handbook of socialization (2nd ed., pp. 135–157). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter R, & Honeycutt H (2010). Rethinking epigenesis and evolution in light of developmental science In Blumberg MS, Freeman J, & Robinson SR (Eds.), Oxford handbook of developmental behavioral neuroscience (pp. 30–47). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liszkowski U (2018). Emergence of shared reference and shared minds in infancy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 23, 26–29. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malti T, & Dys SP (2018). From being nice to being kind: development of prosocial behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 45–49. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols SR, Svetlova M, & Brownell CA (2009). The role of social understanding and empathic disposition in young children’s responsiveness to distress in parents and peers. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13(4), 449–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols SR, Svetlova M, & Brownell CA (2015). Toddlers’ responses to infants’ negative emotions. Infancy, 20(1), 70–97. 10.1111/infa.12066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettygrove DM, Hammond SI, Karahuta EL, Waugh WE, & Brownell CA (2013). From cleaning up to helping out: Parental socialization and children’s early prosocial behavior. Infant Behavior and Development, 36(4), 843–846. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V, Markova G, & Wallot S (2013). Anticipatory adjustments to being picked up in infancy. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e65289 10.1371/journal.pone.0065289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold HL (1982). Little children’s participation in the work of adults, a nascent prosocial behavior. Child Development, 53(1), 114–125. 10.2307/1129643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MP, & Bernal JF (1972). An observational study of mother-infant interaction In Blurton Jones N (Ed.), Ethological studies of child behaviour. (pp. 175–198). Oxford, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmacher N, Köster M, & Kärtner J (2018). Modeling prosocial behavior increases helping in 16-month-olds. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols SR, & Brownell CA (2010). Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development, 81(6), 1814–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M (2014). The ultra-social animal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 187–194. 10.1002/ejsp.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno A, & Matsuzawa T (2004). Food transfer between chimpanzee mothers and their infants. Primates, 45(4), 231–239. 10.1007/s10329-004-0085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F (2013). Young children proactively remedy unnoticed accidents. Cognition, 126(1), 101–108. 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F (2016). Insights into the biological foundation of human altruistic sentiments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 51–56. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, & Tomasello M (2007). Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy, 11(3), 271–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh WE, & Brownell CA (2017). “Help yourself!” What can toddlers’ helping failures tell us about the development of prosocial behavior? Infancy, 22(5), 665–680. 10.1111/infa.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh WE, Brownell CA, & Pollock B (2015). Early socialization of prosocial behavior: Patterns in parents’ encouragement of toddlers’ helping in an everyday household task. Infant Behavior and Development, 39, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, Wagner E, & Chapman M (1992). Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zerwas S, Balaraman G, & Brownell CA (2004). Constructing an understanding of mind with peers. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 27, 130–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Recommended Readings

- Brownell CA (2011). Early developments in joint action. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 2(2), 193–211. 10.1007/s13164-011-0056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Reviews the development of joint action with adults and peers in the first two years of life, showing how it supports the emergence of autonomous cooperative and prosocial activity.

- Brownell CA, & The Early Social Development Research Lab. (2016). Prosocial behavior in infancy: The role of socialization. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 222–227. 10.1111/cdep.12189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Reviews evidence and arguments for socialization as a primary mechanism in the early development of prosocial behavior.

- Dahl A, & Paulus M (in press). From interest to obligation: The gradual development of human altruism. Child Development Perspectives. [Google Scholar]; Discusses several qualitative changes in the development of children’s altruistic motivation.

- Eisenberg N, & Spinrad TL & Knafo-Noam A, (2015). Prosocial development In Lamb ME & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 3, pp. 610–656). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive review of research on the development of prosociality from infancy to adulthood.

- Hepach R, & , Warneken F (2018). Editorial overview: Early development of prosocial behavior: Revealing the foundation of human prosociality. Current Opinion in Psychology. 20, iv–viii. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Introduction to a special issue on the early development of prosocial behavior. The special issue contains contributions that represent a broad range of theoretical and methodological approaches to early prosocial development.