Abstract

Adolescence is a sensitive period for the development of disordered eating and weight-related behaviors, and sexual minorities may be particularly at risk due to heightened minority stress and challenges related to sexual identity development. This review synthesized findings from 32 articles that examined sexual orientation disparities (each with a heterosexual referent group) in four disordered eating behaviors (binging, purging, restrictive dieting, diet pill use) and four weight-related behaviors (eating behaviors, physical activity, body image, and Body Mass Index [BMI]). Potential variations by outcome, sex, race/ethnicity, and developmental stage were systematically reviewed. Evidence supporting sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors was more consistent among males than females. Among females, sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors appeared to be more pronounced during adolescence than in young adulthood. Sexual minority females generally reported more positive body image than heterosexual females but experienced disparities in BMI. Sexual orientation differences in eating behaviors and physical activity were especially understudied. Incorporating objectification and minority stress theory, a developmental model was devised where body image was conceptualized as a key mechanism leading to disordered eating behaviors. To advance understanding of sexual orientation disparities and tailor intervention efforts, research in this field should utilize longitudinal study designs to examine developmental variations and incorporate multi-dimensional measurements of sexual orientation and body image.

Keywords: LGBTQ, health disparities, obesity, body satisfaction, adolescence

Introduction

Adolescence is a sensitive period for the development of disordered eating and weight-related behaviors due to increased concerns about one’s body image (Suisman et al., 2014), greater negative peer influence (Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer, 2010), and heightened vulnerability to media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes (Dakanalis et al., 2015). Longitudinal research suggests that adolescents who engage in dieting and disordered eating behaviors are at elevated risk for the same behaviors 10 years later (Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Story, & Standish, 2012). Unhealthy weight control behaviors such as fasting, skipping meals, and taking diet pills are associated with poorer dietary intake among adolescent females (Larson, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2009). Both dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors longitudinally predict increased BMI across adolescence (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2012). These studies highlight the importance of understanding disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors during the adolescent period.

Sexual minority adolescents may be particularly at risk for disordered eating and weight-related behaviors due to heightened minority stress and challenges related to sexual identity development (Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, 2016; Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013; Watson, Velez, Brownfield, & Flores, 2016). Sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors, body image and Body Mass Index (BMI) are well-documented among adults (Bowen, Balsam, & Ender, 2008; Feldman & Meyer, 2007; Kimmel & Mahalik, 2005; Peplau et al., 2009). The parallel literature among adolescents and young adults is smaller and more mixed. Sexual minority adolescents may be particularly at risk because they have to navigate through challenges related to sexual identity development (Meyer, 2003). Thus, it is important to better understand sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors during the adolescent period.

Several literature reviews exist on sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors, body image or BMI (Bankoff & Pantalone, 2014; Blashill, 2011; Eliason et al., 2015). These reviews, however, exclusively focused on studies among adults and included a restricted range of either disordered eating or weight-related behaviors. Calzo et al. (2017) conducted the only review that included adolescents and young adults. While these authors noted sex differences, they did not focus on developmental differences; moreover, body image, physical activity and eating behaviors were not included as outcomes. Developmentally, sexual minority individuals, on average, first report feeling same-sex attractions around 8–9 years old and first disclose their sexual identity around 18–19 years old (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). Accordingly, adolescence is a critical stage for sexual identity development, and the added stress of navigating one’s sexual orientation and identity during this period may increase the risk for adolescent-limited disordered eating and weight-related behaviors (Corliss, Cochran, Mays, Greenland, & Seeman, 2009; Friedman, Marshal, Stall, Cheong, & Wright, 2008).

In the general adolescent population, disordered eating behaviors are associated with patterns of physical activity and eating behaviors (Middleman, Vazquez, & Durant, 1998; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007). Although sexual minority adolescents may be especially concerned about their body image, it is unclear whether sexual orientation differences extend to different weight-related behaviors, particularly physical activity and eating behaviors. Therefore, it is important to conduct a systematic review that includes a broad range of eating and weight-related outcomes. Moreover, to best guide future research, it is critical to synthesize existing knowledge into a conceptual developmental model for understanding disparities in disordered eating behaviors among sexual minority youth. Specifically, psychological constructs drawn from objectification and minority stress theories may shaping the body image of sexual minority youth, which may then elevate risks for disordered eating behaviors.

Current Study

The goal of the current review is to document sexual orientation disparities in a broad range of disordered eating and weight-related behaviors (binging, purging, restrictive dieting, diet pill use, eating behaviors, physical activity, body image, and BMI), with a focus on understanding differences by outcome, sex, race/ethnicity, and developmental stage (adolescence vs. young adulthood). Variations in the measurement of sexual orientation and the extent to which moderation and mediation analyses were conducted are also documented. Informed by the findings from the systematic review, a conceptual developmental model is proposed as a framework to guide future research that could empirically test each of the hypothesized pathways. Guided by the review and the proposed developmental model, key methodological issues in the current literature and future directions are discussed.

Methods

PubMed, PsychINFO and Web of Science were searched using three sets of key words combined with the AND operator. The first set included sexual orientation key words (gay, lesbian, bisexual, sexual minority, sexual orientation); the second set included key words related to disordered eating and weight-related behaviors (eating, weight, obese, overweight, body, diet, physical activity); the third set specified the age range of interest (adolescent, young adult, college, youth). The commas in the sets represent the OR operator. Literature searches were completed in July 2017. To capture the full range of old and new studies, the search was not restricted by publication date. This yielded a total of 391 articles.

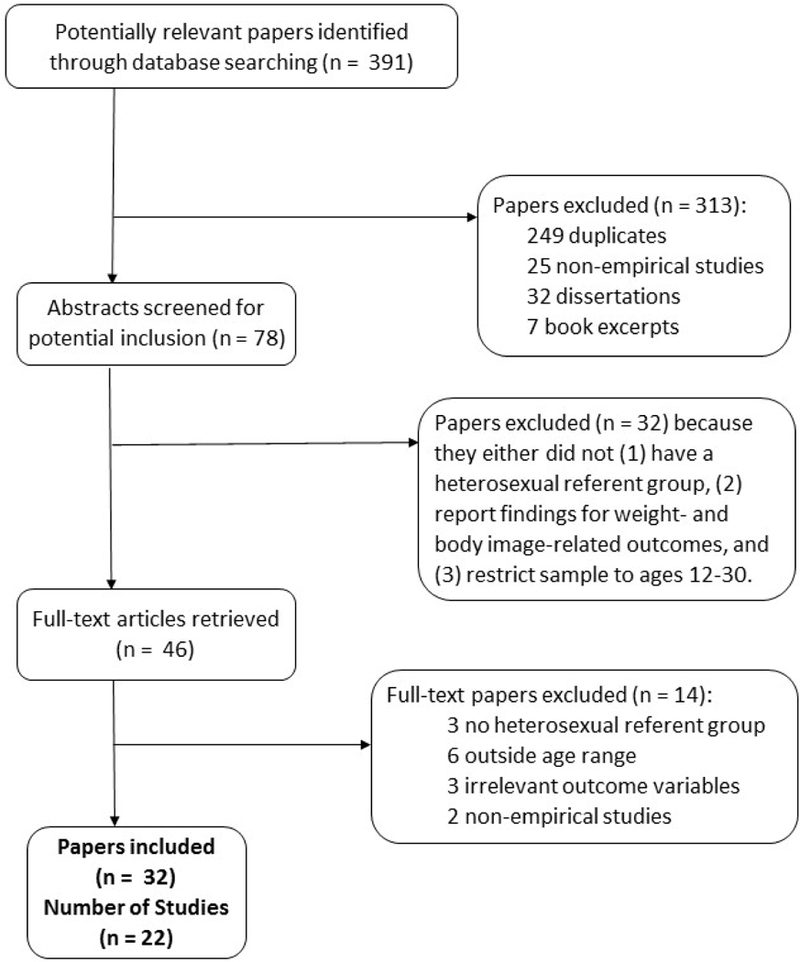

Figure 1 summarizes the article selection process. Duplicates were first removed and the results were restricted to include only empirical studies published in journals, yielding 78 articles. Next, articles were excluded if they (1) did not have a heterosexual referent group, (2) did not examine any disordered eating or weight-related behaviors, and (3) analyzed age groups outside of age range of interest (i.e., the mean age of the sample is over 30 years old). Of the 78 articles whose abstracts were screened, 32 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Accordingly, 46 full-text articles were retrieved. Of these 46 articles, 14 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria specified above. For the final set of 32 articles, the lead author with year, source of data and description of sample, sexual orientation measure(s), outcome variables examined, and main findings were recorded in table form. In text, summaries of findings by outcome variables, with notes on sex and developmental differences, were reported.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion process. The 32 papers summarized in this review came from 22 unique study samples.

Results

Of the articles included in this review, 78.1% (n = 25) were published in the last 10 years, and 59.4% (n = 19) were published in the last five years. This highlights the recent growth in the literature surrounding sexual orientation disparities, following a report by the Institutes of Medicine (2011) calling for increased understanding of health behaviors among sexual minorities. Key components of the articles reviewed are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, which are organized by the developmental stages of adolescence or adolescence to young adulthood and young adulthood, respectively. As sex differences were noted in many studies, results for males were presented first and results for females were presented afterwards.

Table 1.

Studies (n = 15) that analyzed outcomes during the adolescent period (12–19 years old) or adulthood (12–25 years old).

| Authors (year) |

Source of Data and Sample | Sexual Orientation Measure |

Outcomes | Main Findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered Eating Behaviors | Weight-Related Behaviors | ||||||||||

| Binge | Purge | Diet | Diet Pills |

EB | PA | Body Image |

BMI | ||||

| Ackard, et al. (2008) | Source: Minnesota Student Survey Sample: 10,095 sexually active males (mean age of 16.7 ± 1.5, range 13–19); 82.9% White, 6.7% Black, 4.3% Asian, 6.1% Other/Multiracial | Sexual behaviors | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Males with same-sex and both-sex partners scored higher on several measures of disordered eating than heterosexual males. Rates of disordered eating behaviors were highest among males who reported having 3 or more sex partners of both genders. | |||||

| Austin, et al. (2004) | Source: Growing Up Today Study Sample: 10,583 females and males (age range 13–17); 93.3% White, 1.5% Asian, 1.5% Hispanic, 0.9% Aferican American, 0.8% Native American, 2.2% Other | Single item on sexual attraction/identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Among females, lesbians/bisexuals report being happier with the way their bodies look and being less concerned with trying to look like women in the media compared to heterosexuals. Mostly heterosexual females were more likely to report diet pill use and binging compared to heterosexual females. Among males, SM report wanting to look like men in the media and are more likely to report binging. | |||

| Austin, et al. (2009)c | Source: Growing Up Today Study Sample: 13,785 females and males (age range 12–23); 93.3% White, 1.5% Asian, 1.5% Hispanic, 0.9% African-American, 0.8% American-Indian, and 2.2% Other | Single item on sexual attraction/identity | ✔ | ✔ | Among females, lesbians and bisexuals were more likely to report binge eating compared to heterosexuals or mostly heterosexuals. Among males, SM were more likely to report both purging and binge eating than heterosexuals. | ||||||

| Austin, et al. (2013) | Source: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (2005, 2007) Sample: 24,591 females and males (mean age of 15.9 ± 1.3, range 13–18); about 35.8% White, 24.9% Black, 18.1% Hispanic, 12.5% Asian, 8.8% Other (averaged across sex) | Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Ethnicity did not moderate the association between sexual identity and the three outcomes examined. For both females and males, SM had higher odds of purging and diet pill use. Bisexual females and males also had greater odds of obesity compared to heterosexual peers. | |||||

| Calzo, et al. (2013)c | Source: Growing Up Today Study (1999–2005) Sample: 5,868 males (age range 12–25); 93% White |

Single item on sexual attraction/identity | ✔ | Male SM reported increased desires for toned/defined muscles, bigger muscles and weight concerns compared to heterosexual males. | |||||||

| Calzo, et al. (2014)b,c | Source: Growing Up Today Study (1999–2005) Sample: 12,779 females and males (range 12–22) |

Single item on sexual attraction/ identity |

✔ | SM adolescents report lower moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and team sports involvement than their heterosexual peers. *Athletic self-esteem accounted for the differences across sex, while gender nonconformity accounted for differences in males. |

|||||||

| Calzo, et al. (2015)c | Source: Growing Up Today Study (2001–2005) Sample: 5,388 males (age range 15–20); 94% White |

Single item on sexual attraction/identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM males had higher odds for being lean-concerned but no higher odds of being muscle-concerned compared to heterosexual males, where indicators of being lean-concerned included elevated concern with weight and shape, binge eating, dieting, and purging. | ||

| French, et al. (1996) | Source: subsample of Minnesota population-based sample Sample: 788 males and females (age range 12–18); for the total sample: 86.4% White, 7.8% Black, 3.1% Asian, 1.6% Native American, 1.1% Hispanic | Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Among females, SM reported a more positive body image than heterosexual peers and were less likely to report feeling overweight, but were no more likely to report disorder eating behaviors. Among males, SM were more likely to report a poorer body image and higher rates of ever binge eating, fear of out of control eating and laxative use than heterosexual peers. | ||

| Hadland, et al. (2014) | Source: Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey Sample: 12,984 females and males (age range 14–18); about 74.2% White, 11.8% Hispanic, 8.7% Black, 2.5% Asian, 2.9% Other/Mixed (averaged across sex) | Sexual identity and behaviors | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Among females, SM endorsed higher odds of fasting, diet pills use and purging than heterosexual peers, and were more likely to perceive self as healthy weight while being overweight or obese. Among males, SM endorsed higher odds of fasting, use of diet pills and purging than heterosexual peers, and were more likely to feel overweight while being healthy/underweight. | |||

| Katz-Wise, et al. (2014)c | Source: Growing Up Today Study (1996–2007) Sample: 13,952 females and males (age range 12–25); 93.3% White, 6.7% Other |

Single item on sexual attraction/identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Among females, SM reported greater rates of binge eating and fast food consumption than heterosexual peers. Bisexual females reported higher BMI at age 17 and greater increases in BMI than heterosexual peers over time. Among males, SM reported higher rates of binge eating and lower caloric intake than heterosexual peers. Gay males reported smaller increases in BMI over time and had a lower BMI than heterosexual peers at age 25. | |||||

| Mereish and Poteat (2015) | Source: Dane County Youth Assessment Sample: 13,933 females and males (age range 12–18); 73.5% White, 7.3% Multiracial, 5.3% Black, 5.1% Hispanic, 4.2% Asian, 0.6% Native American, 0.6% Middle-Eastern, 2.2% Other | Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | Compared to heterosexual peers, SM females were less likely to be involved in sports only, whereas SM males were less likely to be involved in sports and were also less likely to report physical activity. Disparity in BMI was only found among females, such that SM females were more likely than heterosexual females to report being overweight or obese. | ||||||

| Rosario, et al. (2014) | Source: Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2005, 2007) Sample: 65,871 females and males (age range 12–18); 53.2% White, 18.8% Hispanic, 19.2% Black, 8.8% Asian |

Sexual identity, behaviors and attraction | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM females were more likely to report purging and being overweight than heterosexual females. SM males were more likely than heterosexual males to get little physical activity, engage in purging, but less likely to have a diet low in fruits and vegetables. | ||||

| Shearer, et al. (2015)c | Source: Behavioral Health Screen Sample: 2,513 females and males (mean age of 17.24 ± 1.5, range 14–24); 59.7% White, 16.6% Hispanic, 9.1% Other, 8.1% Biracial, 4.7% Black, 1.8% Asian | Sexual attraction and behavior | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Females who reported attraction to both sexes or were unsure about their sexual orientation were more likely to report higher disordered eating symptoms compared to those endorsing attraction to one sex. Males attracted to other males reported higher rates of disordered eating symptoms compared to males only attracted to the opposite sex. | |||||

| Watson, et al. (2017)b | Source: Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey (1999–2013) Sample: 26,002 females and males (age range 12–18) | Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Although the overall prevalence of disordered eating behaviors has decreased from 1999–2003, sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors persisted for SM males and has increased for SM females over time. | |||||

| Yoon and So (2013) | Source: Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2012) Sample: 11,829 females and males (age range 12–18); 100% Korean | Sexual behavior | ✔ | ✔ | SM females reported higher rates of moderate and vigorous physical activities, and muscular strength exercises than heterosexual females. SM males reported lower rates of muscular strength exercises and walking than heterosexual males. | ||||||

| TOTAL: | 7 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 8 | |||

EB = eating behaviors; PA = physical activity; SM = Sexual Minorities

Indicates factors associated with outcomes presented in paper

Indicates studies without description of race/ethnicity composition

Indicates studies that covered both adolescence and young adulthood (12–25 years old)

Table 2.

Studies (n = 17) that analyzed outcomes during the period of young adulthood (19–30 years old).

| Authors (year) |

Source of Data and Sample | Sexual Orientation Measure |

Outcomes | Main Findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered Eating Behaviors | Weight-Related Behaviors | ||||||||||

| Binge | Purge | Diet | Diet Pills |

EB | PA | Body Image |

BMI | ||||

| Carper, et al. (2010) | Source: recruited from a large, public university Sample: 78 males (mean age of 19.31 ± 0.89); 71.8% White, 17.9% Hispanic, 7.7% Black, 2.6% Asian |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | *Gay males had higher susceptibility to media influences on body image than heterosexual males, which partially accounted for disparities in drive for thinness and appearance-related anxiety. | |||||||

| Conner, et al. (2004)b | Source: convenience sample Sample: 121 females and males (mean age of gender and sexual orientation subgroups ranged from 21.4 to 23.9) |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Several gender-by-sexual orientation interactions were found. Eating weight control motive and restrained eating were lower among heterosexual males relative to either females in general or homosexual males. Body dissatisfaction was higher among heterosexual females and homosexual males. BMI was higher among heterosexual males relative to the other three groups. | ||||

| Dakanalis, et al. (2012) | Source: recruited via advertisements Sample: 255 Italian males (age range 19–25); 100% Italian |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | *Relative to heterosexual males, SM males reported greater exposure to sexually objectifying media and body shame. Sexually objectifying media may contribute to increased disordered eating behaviors, and especially for SM males. | |||

| Diemer, et al. (2015) | Source: ACHA-NCHA II (2008–2011) Sample: 289,024 males and females (median age of 20); White 69.58%, 10.13% Asian, 7.13% Multiracial, 5.96% Hispanic, 4.5% Black, 2.27% Other, 0.43% Native American |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | Transgender individuals were more likely than cisgender heterosexual females to report past-year eating disorder diagnosis, past-month diet pill use and purging. Cisgender sexual minority/unsure males and cisgender unsure females were more likely to have been diagnosed with past-year eating disorder. | ||||||

| Fussner and Smith (2015) | Source: recruited from a university Sample: 201 males (mean age of 20.46); 75.6% White, 8.1% Black, 7.6% Asian, 5.6% Multiracial, 2.0% Other, 1.0% Native American |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | Gay males endorsed greater discrepancies in current shape and shape they perceived their partner to consider attractive than heterosexual males. *Among both gay and heterosexual males, this discrepancy was positively associated with eating disorder symptoms and body shape or weight concerns. |

||||||

| Gettelman and Thompson | Source: recruited from a large southern university Sample: 64 females and 64 males (mean age of sexual orientation subgroups ranged from 25.1 to 27.3); 91.4% White, 3.1% Black, 3.1% Asian, 2.4% Hispanic |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Generally, SM females reported lower actual concerns with appearance, weight and dieting than heterosexual females. SM males reported greater actual concerns with appearance, weight and dieting than heterosexual males. | |||

| Laska, et al. (2015) | Source: College Student Health Survey (2007–2011) Sample: 33,907 females and males (age range 18–25); 83.3% White, 6.3% Asian, 3.9% Black, 2.2% Hispanic, 4.3% Mixed/Other |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM females were more likely to be obese, consume restaurant food several times per week, and engage in binge eating than heterosexual females. SM males were more likely to report any unhealthy weight control, express body dissatisfaction, and engage in binge eating than heterosexual males. Gay males exhibited less physical activity and were less likely to consume soda than heterosexual males. | ||

| Li, et al. (2010)b | Source: psychology students at University of Texas at Austin Samples: Study 1 – 458 students (mean age of 18.4 ± 0.9 for females, 19.0 ± 1.9 for males); Study 2 – 383 students (mean age of 20.8 ± 3.6 for females, 21.5 ± 3.9 for males) |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | *Laboratory-based experimental evidence suggested that intrasexual competition cues led to worse body image and restrictive eating attitudes among heterosexual females and gay males. | |||||

| Lipson and Sonneville (2017) | Source: Healthy Bodies Study (2013–2015) Sample: 9,713 females and males (age range 18–30); 78.97% White, 11.42% Asian, 10.95% Latino/a, 6.28% African American, 8.78% Other |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM females were less likely to have compensatory behaviors than heterosexual females. SM males were more likely to have elevated disordered eating risk than heterosexual males. No sexual orientation differences in objective binge eating were found. | |||

| Matthews-Ewald, et al. (2014)b | Source: ACHA-NCHA (2008–2009) Sample: 110,412 (mean age of 22.1 ± 5.7) |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM females reported higher odds of dieting to lose weight than heterosexual females. SM males reported higher odds of dieting to lose weight, diet pill use, purging, and past year eating disorder diagnosis than heterosexual males. | |||||

| McElroy and Jordan (2014) | Source: ACHA-NCHA Sample: 18,440 females (mean age of ~21); for heterosexual and LBQ groups: 60–64% White, 10–12% Asian/Pacific Islander, 10–12% Hispanic, 8–9% Black, 7–11% Biracial/Multiracial, 1–2% Other, 8–9% missing |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | SM females were more likely to be self-described as “very overweight” and were more likely to be obese than heterosexual females. SM females also had similar rates of fruit and vegetable consumption but were less likely to meet physical activity guidelines relative to heterosexual females. | ||||

| Siever (1994) | Source: sample from University of Washington and Seattle Central Community College Sample: 237 females and males; 76.6% White, 18.0% Asian, 2.4% Native American, 2.0% Latino, 1.2% African-American |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Heterosexual females and homosexual males had elevated concern with their own physical attractiveness, were more dissatisfied with their bodies, and were more vulnerable to eating disorders. Lesbians also reported higher mean BMI than heterosexual females. Sexual objectification by sexual or romantic partners may explain observed disparities in drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating behaviors among sexual minorities. | |||||

| Smith, et al. (2011) | Source: recruited from large southeastern university Sample: 204 males (mean age of 20.49 ± 3.27); 78% Caucasian, 17% Hispanic, 8% Asian, 7% Black, 4% Multiracial, 1% Native American, 2% Missing, |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Gay males reported higher levels of disordered eating behaviors and had greater body fat dissatisfaction than heterosexual males. *Body fat dissatisfaction predicted disordered eating behaviors in gay males. |

|||||

| Striegel-Moore, et al. (1990)b | Source: recruited from different social organizations and psychology subject pool Sample: 30 self-identified lesbians (mean age of 20.10 ± 0.90) and 52 heterosexual females (mean ages ranged from 19.60 to 20.00) |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Lesbian and heterosexual female college students did not differ on multiple measures of body esteem and disordered eating behaviors. | |||||

| Strong, et al. (2000)b | Source: recruited from psychology classes at Louisiana State University Sample: 412 females and males (age range 18–30) |

Kinsey scale | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Heterosexual females reported the highest rates of eating disorder symptoms and concerns with body size/shape, followed by gay males and lesbian females. Heterosexual males had the lowest rates of eating disorder symptoms and concerns with body size/shape. | ||||

| Struble, et al. (2011)b | Source: ACHA-NCHA (2006) Sample: 31,500 females (age range 18–25) |

Sexual identity | ✔ | Female SM college students were more likely to be overweight and obese than female heterosexual college students. Lesbians were less likely to be underweight than heterosexual females. | |||||||

| VanKim, et al. (2016)b | Source: College Student Health Survey (2009–2013) Sample: 28,703 females and males (age range 18–25) |

Sexual identity | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | For both females and males, SM were significantly more likely than heterosexual peers to fall under the “unhealthy weight control” profile, which is indicative of low physical activity, poor diet, high body dissatisfaction and poor quality of life. | ||||

| TOTAL: | 6 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 9 | |||

EB = eating behaviors; PA = physical activity; SM = Sexual Minorities. ACHA-NCHA = American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment.

indicates factors associated with outcomes presented in paper.

indicates studies without description of race/ethnicity composition.

Disordered Eating Behaviors

Restrictive dieting (n = 19).

Seventeen studies found that sexual minority males reported higher rates of restrictive dieting and fasting during adolescence and young adulthood compared to heterosexual males (Ackard, Fedio, Neumark-Sztainer, & Britt, 2008; S. B. Austin et al., 2004; Calzo et al., 2015; Conner, Johnson, & Grogan, 2004; Dakanalis et al., 2012; Fussner & Smith, 2015; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Hadland, Austin, Goodenow, & Calzo, 2014; Laska et al., 2015; Li, Smith, Griskevicius, Cason, & Bryan, 2010; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Matthews-Ewald, Zullig, & Ward, 2014; Shearer et al., 2015; Siever, 1994; Smith, Hawkeswood, Bodell, & Joiner, 2011; Strong, Williamson, Netemeyer, & Geer, 2000; Watson, Adjei, Saewyc, Homma, & Goodenow, 2017). French and colleagues (1996) found sexual minorities and heterosexuals did not differ in the likelihood of restrictive dieting, and the other study utilized a female-only sample (Striegel-Moore, Tucker, & Hsu, 1990).

Restrictive dieting behaviors among females are less consistently reported. Four studies revealed no difference between sexual minorities and heterosexuals (Austin et al., 2004; French et al., 1996; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Strong et al., 2000). Two studies focusing on the adolescent period indicated sexual minority females were more likely to report fasting relative to heterosexual females (Hadland et al., 2014; R. J. Watson et al., 2017). Two studies focusing on the young adult period suggested sexual minority females were less likely than heterosexual females to report restrictive dieting (Conner et al., 2004; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993), but two other studies found the opposite (Hadland et al., 2014; Matthews-Ewald et al., 2014). Thus, sexual orientation disparities in restrictive dieting among females may be more apparent during adolescence than young adulthood.

Purging (n = 17).

All seventeen studies that measured purging found that sexual minority males were especially at risk for purging relative to heterosexual males across adolescence and young adulthood (Austin, Nelson, Birkett, Calzo, & Everett, 2013; Austin et al., 2004; Calzo et al., 2015; Carper, Negy, & Tantleff-Dunn, 2010; Dakanalis et al., 2012; Diemer, Grant, Munn-Chernoff, Patterson, & Duncan, 2015; French et al., 1996; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Hadland et al., 2014; Li et al., 2010; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Matthews-Ewald et al., 2014; Rosario et al., 2014; Shearer et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2011; Strong et al., 2000; Watson et al., 2017).

Among females, results were conflicting. Six studies demonstrated no significant differences between sexual minority and heterosexual females for purging, regardless of developmental stage (Austin et al., 2004; French et al., 1996; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Matthews-Ewald et al., 2014; Strong et al., 2000). Four studies suggested sexual minority females had increased likelihood of purging in adolescence (Austin et al., 2013; Hadland et al., 2014; Rosario et al., 2014; R. J. Watson et al., 2017), but in another study, sexual minority females had decreased likelihood of purging in young adulthood (Diemer et al., 2015). These data suggested sexual minority females experienced disparities in purging during adolescence, with less consistent findings during young adulthood.

Binging (n = 13).

Among males, the twelve studies that included a binging item demonstrated sexual minority males endorsed increased likelihood of binging during adolescence and young adulthood compared to heterosexual males (Ackard et al., 2008; Austin et al., 2004; Austin et al., 2009; Calzo et al., 2015; Conner et al., 2004; Dakanalis et al., 2012; French et al., 1996; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Katz-Wise et al., 2014; Laska et al., 2015; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Shearer et al., 2015). The remaining study utilized a female-only sample (Striegel-Moore et al., 1990).

Findings among females were mixed. Three studies suggested comparable rates of binging for sexual minorities and heterosexuals (Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Striegel-Moore et al., 1990). Studies that covered the adolescent period suggested sexual minorities were more likely to binge relative to heterosexuals (Austin et al., 2004; Katz-Wise et al., 2014; Shearer et al., 2015). During young adulthood, Laska and colleagues (2015) found sexual minorities were more likely to binge, but another study by Conner and colleagues (2004) found the opposite. Similar to restrictive dieting and purging, sexual minority males appeared to be especially at risk for binging across development. Sexual minority females experienced disparities during adolescence, with conflicting results during young adulthood.

Diet pill use (n = 11).

Across development, all eleven studies showed sexual minority males endorsed higher rates of diet pill use compared to heterosexual males (Ackard et al., 2008; Austin et al., 2013; Austin et al., 2004; Calzo et al., 2015; Diemer et al., 2015; French et al., 1996; Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Hadland et al., 2014; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Matthews-Ewald et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2017).

Comparatively, the picture of diet pill use among females is rather obscure, as most studies used male-only samples. Three studies found no difference between sexual minority and heterosexual females for past-month diet pill use (Gettelman & Thompson, 1993; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017; Matthews-Ewald et al., 2014). Three studies focusing only on adolescence found that sexual minorities reported increased likelihood of past-month diet pill use relative to heterosexual peers (Austin et al., 2013; Austin et al., 2004; Hadland et al., 2014). Diemer and colleagues (2015) found that sexual minority females reported decreased likelihood of past-month diet pill use compared to heterosexual females during young adulthood. In sum, sexual minority males were at risk for increased rates of diet pill use, whereas sexual minority females were only at risk during adolescence.

Weight-Related Behaviors

Eating behaviors (n = 5).

Only five studies examined sexual orientation differences in eating behaviors. Rosario and colleagues (2014) found that both male and female sexual minority adolescents were less likely to have a diet low in fruits-and-vegetables compared to heterosexual adolescents. McElroy and Jordan (2014) reported no difference between sexual minorities and heterosexuals in meeting guidelines for daily fruit and vegetable intakes. In contrast, two studies that only covered the adolescent period showed that sexual minorities engaged in greater fast-food consumption (Katz-Wise et al., 2014) and were more likely to exhibit unhealthy eating behaviors (VanKim et al., 2016). During young adulthood, Laska and colleagues (2015) reported that sexual minorities were less likely to consume soda compared to heterosexuals, suggesting healthier eating behaviors. Taken together, sexual orientation differences in eating behaviors may vary based on the specific eating behavior and developmental stage.

Physical activity (n = 7).

Physical activity disparities among sexual minorities have been understudied in the current literature. Among males, data from three large-scale U.S. samples demonstrated that sexual minorities engaged in less physical activity compared to heterosexuals (Calzo et al., 2014; McElroy & Jordan, 2014; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Rosario et al., 2014). Similar findings from a study from Yoon and So (2013) demonstrated that, among Korean adolescents, sexual minorities reported lower rates muscle-strengthening exercises and walking compared to heterosexuals. During young adulthood, VanKim and colleagues (2016) utilized latent class analyses and demonstrated that sexual minorities were more likely to exhibit the “unhealthy weight control” behavior profile, which was characterized by little physical activity. Similarly, Laska and colleagues (2015) observed disparities in strenuous, moderate-to-vigorous, and strengthening physical activity for sexual minorities.

Among females, five studies found no differences in physical activity between sexual minorities and heterosexuals (Calzo et al., 2014; McElroy & Jordan, 2014; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Rosario et al., 2014). The study by Yoon and So (2013) was again the only exception, finding that sexual minorities reported less overall physical activity compared to heterosexuals. While data for sexual minority females remain unclear, physical activity disparities for sexual minority males exist during both adolescence and young adulthood.

Body image (n = 18).

In this review, “body image” was used as a catchall term comprising items like body dissatisfaction and weight perception. Among males, two-thirds (n = 12) of studies indicated sexual minorities reported worse overall body image compared to heterosexuals (Austin et al., 2004; Carper et al., 2010; Conner et al., 2004; Dakanalis et al., 2012; French et al., 1996; Fussner & Smith, 2015; Laska et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010; Siever, 1994; Smith et al., 2011; Strong et al., 2000; VanKim et al., 2016). During adolescence, weight perception relative to BMI emerged as an important construct. Hadland and colleagues (2014) found that sexual minority males were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight while being healthy/underweight. During young adulthood, two studies found that sexual minorities reported greater drives for leanness and concerns with shape compared to heterosexuals (Calzo, Corliss, Blood, Field, & Austin, 2013; Calzo et al., 2015).

Among females, findings consistently demonstrated that sexual minorities endorsed more positive body image relative to heterosexual females across development (Austin et al., 2004; Carper et al., 2010; Conner et al., 2004; Dakanalis et al., 2012; French et al., 1996; Fussner & Smith, 2015; Laska et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010; Siever, 1994; Smith et al., 2011; Strong et al., 2000; VanKim et al., 2016). The study by Striegel-Moore and colleagues (1990) was the only exception; however, since these data were rather antiquated, their findings may not reflect patterns in the present day. In another study, Hadland and colleagues (2014) found that, compared to heterosexuals, sexual minorities were more likely to perceive themselves as healthy/underweight while being overweight. Taken together, sexual minority males appeared to be particularly at risk for poor body image, but sexual minority females may have better self-perceived body image.

BMI (n = 17).

Among males, the majority of studies (n = 15) reported no differences between sexual minorities and heterosexuals in BMI (Austin et al., 2013; Calzo et al., 2013; Calzo et al., 2014; Conner et al., 2004; Dakanalis et al., 2012; French et al., 1996; Hadland et al., 2014; Katz-Wise et al., 2014; Laska et al., 2015; Mereish & Poteat, 2015; Rosario et al., 2014; Siever, 1994; Strong et al., 2000; VanKim et al., 2016; Yoon & So, 2013).

Studies among females consistently showed increased disparities in BMI among sexual minority youth. Three studies that covered the adolescent period reported higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals (Austin et al., 2009; Calzo et al., 2014; Rosario et al., 2014). Similarly, emerging data suggested increased disparities in BMI among females during young adulthood. One study found sexual minorities had elevated BMI compared to heterosexuals (McElroy & Jordan, 2014), and two other studies demonstrated higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among sexual minority females (Laska et al., 2015; Struble, Lindley, Montgomery, Hardin, & Burcin, 2010). Overall, sexual minority females experience increased disparities in BMI during both adolescence and young adulthood.

Mediators of sexual orientation disparities.

Only six studies (as indicated by ‘a’ in Tables 1 and 2) examined factors that may account for the observed sexual orientation disparities. Of these, the majority (n = 5) assessed factors associated with disparities in body image and disordered eating behaviors. These studies assessed intrasexual competition (Li et al., 2010), media influences (Carper et al., 2010; Dakanalis et al., 2012), sexual partner influences (Fussner & Smith, 2015) and body fat dissatisfaction (Smith et al., 2011) as explanation for these disparities among young adults. In two laboratory-based experiments, Li and colleagues (2010) found that intrasexual competition cues led to worse body image and restrictive eating attitudes among heterosexual females and gay males. The constructs examined in the other four studies partially explained disparities in body image and disordered eating behaviors among sexual minority males. Only one study examined mediators of sexual orientation disparities in sports involvement and physical activity. Calzo and colleagues (2014) found athletic self-esteem explained sexual orientation disparities in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, whereas gender nonconformity explained these disparities among males only.

Moderators of sexual orientation disparities.

Sex was conceptualized as a moderator of sexual orientation disparities in 23 out of 32 studies. Only two of those 23 studies, however, tested sexual orientation by sex interactions (Calzo et al., 2014; Conner et al., 2004). Calzo et al. (2014) did not find significant interactions between sex and sexual orientation, but stratified their analyses by sex due to a marginally significant interaction between gender and age. They found that sexual minorities reported lower levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sports participation compared to heterosexuals across both sexes. Conner et al. (2004) detected several gender by sexual orientation interactions. They found that heterosexual males reported lower rates of restrictive dieting compared to females in general and homosexual males, and heterosexual males reported higher BMI relative to the other three groups. The remaining 21 studies stratified analyses by sex and did not test sexual orientation by sex interactions.

Twenty-three of the 32 studies included in this review included information on race/ethnicity composition (studies without information on race/ethnicity are indicated by ‘b’ in Tables 1, 2). Of these 23 studies, two studies (both utilizing the 2005 and 2007 Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System Surveys) examined differences by race/ethnicity. Austin et al. (2013) found that ethnicity did not moderate associations between sexual orientation and purging, diet pill use and BMI. Similarly, stratified analyses conducted by Rosario et al. (2014) indicated that sexual orientation differences mostly persisted across various age, gender, and race/ethnicity groups. The vast majority of studies likely did not test interactions between sexual orientation and race/ethnicity due to the use of predominantly White samples. Thus, understanding potential variations in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors among sexual minorities by race/ethnicity proves difficult. This lack of diversity may also explain why other demographic variables such as geographical location (e.g. urban versus rural) and socioeconomic status were not tested as moderators.

Discussion

Adolescence is a sensitive period for the development of disordered eating and weight-related behaviors. Although several reviews summarized the adult literature on sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating or weight-related behaviors (Bankoff and Pantalone 2014; Blashill 2011; Eliason et al. 2015), no developmentally-informed review of the corresponding adolescent and young adult literature is available. This review filled this critical gap by summarizing the current literature on sexual orientation disparities in eight specific disordered eating and weight-related behavior during adolescence and young adulthood. Our review highlighted important differences by outcome and developmental stage for sexual minority females. Notably, while sexual minority males consistently endorsed increased rates of disordered eating behaviors and weight-related concerns during both adolescence and young adulthood, sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors among females appeared to be more pronounced during adolescence. Moreover, across development, sexual minority females reported more positive body image than heterosexual females but experienced disparities in BMI. For both males and females, sexual orientation differences in eating behaviors and physical activity are especially understudied.

While sexual minority males endorsed disparities in disordered eating behaviors across development, sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating behaviors among females appeared to be largely restricted to adolescence and generally did not extend into young adulthood. Past studies suggested that sexual minority adolescents endure multiple victimization experiences and social isolation that could result in serious physical health problems, such as hypertension and stroke (Andersen, Zou, & Blosnich, 2015; Russell, Ryan, Toomey, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2011). Across development, factors may emerge during young adulthood to protect against physical health disparities experienced by sexual minorities. The solidification of sexual identity and the emergence of a tight-knit, supportive sexual minority community that was inaccessible during adolescence may partially explain developmental variations (Floyd & Stein, 2002). Disordered eating and aspects of weight-related problems are more frequently studied in the literature, whereas sexual orientation differences in positive aspects of physical health are less frequently examined. Based on the limited research to date, eating behaviors of sexual minorities may vary based on the particular eating behavior examined and developmental stage. The range of eating behaviors in the current literature are restricted to fruit and vegetable intake (Rosario et al., 2014), diet soda consumption (Laska et al., 2015) and fast-food consumption (Katz-Wise et al., 2014). The findings in this review underscore the need to examine a broader range of eating behaviors to understand the full profile of food consumption, as well as sexual minorities’ motivations behind choosing particular types of food.

Available data suggest that sexual minority males are especially at risk for receiving little physical activity compared to heterosexual males during adolescence and young adulthood. Potential variability within sexual minority populations, however, has largely been unexamined in this literature. Past research noted that health disparities could vary by sexual orientation subgroup identity (Davids & Green, 2011), and so collapsing all non-heterosexual individuals into a single category may not fully capture these nuanced differences. In particular, motivations for physical activity may vary by sexual orientation subgroup. For instance, Calzo et al. (2013) found that gay/bisexual males reported greater concerns with leanness, whereas males who identify as mostly heterosexual reported greater drives for muscularity compared to heterosexuals. Thus, more research is needed to understand not only sexual orientation differences in physical activity, but also subgroup differences and the underlying motivations.

Mediators of sexual orientation disparities.

Although most studies did not examine mediators, several important variables emerged in the available studies and should be further tested in future research. Intrasexual competition may partially explain poor body image in sexual minority males (Li et al., 2010). In addition, sexual minority males reported greater exposure to sexually objectifying media and may be more susceptible to media influences than their heterosexual peers (Carper et al., 2010; Dakanalis et al., 2012). Only one study examined factors associated with physical activity disparities, illustrating the need to study mechanisms underpinning sexual orientation disparities in weight-related behaviors. Objectification as a pathway to disordered eating behaviors has been integrated into the conceptual developmental model presented below and should be empirically tested in future studies.

Moderators of sexual orientation disparities.

Only two studies included in this review tested sexual orientation by sex interactions (Calzo et al., 2014; Conner et al., 2004). Only one study tested race/ethnicity as a moderator of sexual orientation disparities (Austin et al., 2013), while another study conducted stratified analyses by race/ethnicity (Rosario et al. 2014). The decision to conduct stratified analyses by sex or race/ethnicity or treat race/ethnicity as a covariate was often justified based on practical considerations related to statistical power and the low proportion of racial/ethnic minorities in study samples. Such practices, however, highlight an important literature gap concerning possible intersections between sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. In theory, multiple minority identities could increase exposure to minority stressors, which in turn elevate risk for adverse health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). Future studies utilizing diverse samples should attempt to understand possible complex interactions between sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation on mental and physical health outcomes (Consolacion, Russell, & Sue, 2013; Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt, 2009; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010).

Beyond sex and race/ethnicity, no other moderators were tested in the studies reviewed. A recent commentary noted that sexual minority adolescents living in rural areas may have inequitable access to healthcare relative to their non-rural counterparts (Hubach, 2017), highlighting the importance of considering geographical location as a possible moderator. Additionally, family connectedness, social support and self-esteem may moderate sexual orientation health disparities during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood (Darwich, Hymel, & Waterhouse, 2012; Pakula, Carpiano, Ratner, & Shoveller, 2016), and should be examined as potential moderators in future studies.

Toward a conceptual developmental model.

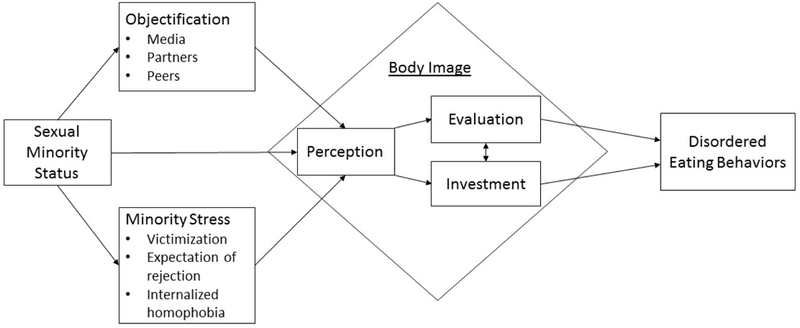

The proposed developmental model synthesizes empirically supported and theoretical pathways underlying sexual orientation disparities in aspects of disordered eating and weight-related behaviors (Figure 2). A meta-analytic review from Goldbach and colleagues (2014) identified the following as risk-factors for negative health outcomes among sexual minorities: victimization, negative disclosure events, minority stress, and a lack of supportive environments, which were supported by other empirical studies (Marshal, Friedman, Stall, & Thompson, 2009; Needham & Austin, 2010; Pakula et al., 2016). The minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) posits that stressors unique to sexual minority status – victimization experiences, internalized homophobia, and expectations of rejection – lie at the heart of observed health disparities among sexual minorities. Taking a developmental perspective, sexual minorities may generally be at increased risk for negative health outcomes associated with their minority identity, but the added stress of navigating the development of their minority identity during adolescence may further increase risk for time-specific negative health outcomes.

Figure 2.

Proposed pathway for sexual orientation disparities in body image and disordered eating behaviors. Perception refers to how one sees one’s body (e.g. self-perceived overweight) and the discrepancy between one’s actual and perceived body shape/weight status (e.g. misperceiving as overweight while being normal weight); evaluation refers to the attitudes held toward one’s body (e.g. body dissatisfaction); investment refers to the efforts toward achieving one’s ideal body (e.g. drive for thinness).

Objectification theory posits that individuals become acculturated to internalizing outside perceptions of their bodies as the primary lens through which to see and judge themselves (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). This may offer some insight into the role body image in the emergence and persistence of disordered eating and weight-related disparities among sexual minorities. Empirical studies suggested that objectification theory can be used to explain observed disparities in body dissatisfaction and restrained eating among sexual minority males (Martins, Tiggemann, & Kirkbride, 2007). Among females, the solidification of sexual identity and increased sense of belonging to a sexual minority community may protect sexual minority females from poor body image and disordered eating symptoms (Hill & Fischer, 2008).

Taken together, sexual minority adolescents may be driven to engage in certain eating and weight-related behaviors due to their concerns with their own body image. Past research indicated that body image is comprised of both perceptions and attitudes (Grogan, 2006), and attitudes are further divided into evaluation, affect, and investment (Muth & Cash, 1997). Among the general adolescent and young adult populations, studies demonstrated that self-perceiving as overweight, a form of negative body image perception, is associated with restrictive dieting (Strauss, 1999) and disordered eating symptomology (Keel, Baxter, Heatherton, & Joiner, 2007). Similarly, body dissatisfaction, a negative body image evaluation, is consistently linked to disordered eating behaviors (Neumark-Sztainer, Paxton, Hannan, Haines, & Story, 2006). Several studies indicated drives for leanness among males and thinness among females, two types of body image investments, further increase body dissatisfaction (Jones, 2004; Presnell, Bearman, & Slice, 2004; Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2004), which in turn may increase odds of engaging in disordered eating behaviors. Consolidating these facts within a conceptual framework, negative body perception is proposed as a key mechanism leading to negative body evaluations and various body image investments, which then lead to various disordered eating behaviors.

The proposed conceptual developmental model is built upon our review of the empirical literature. Accordingly, this model does not account for developmental pathways that are less frequently examined in past empirically studies. First, the proposed model does not account for observed disparities in physical activity among sexual minority males and disparities in BMI among sexual minority females. Plummer (2006) argued homophobia bars sexual minority males from achieving equitable sports participation, but empirical studies relating minority stressors to physical activity disparities are lacking. Similar to disordered eating behaviors, BMI among sexual minority females may partially stem from maladaptive coping strategies to deal with minority stressors (Eliason & Fogel, 2015). Prior research has linked minority stressors to binge eating through internalizing symptoms (Katz-Wise et al., 2015) and social anxiety (Mason & Lewis, 2016), which may also offer partial explanations for increased weight among sexual minority females.

Second, this model does not account for greater healthful eating behaviors among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals. As sexual minorities report greater drives for leanness compared to heterosexuals (Smith et al., 2011), observed healthful eating behaviors may be a function of both negative body image investments and negative body image evaluations. Accordingly, future studies should assess how drive for leanness and body dissatisfaction impact fruit, vegetable and meat intakes, overall kcal per day intakes, and use of weight-gain supplements. Among sexual minority females, future studies should seek to elucidate the relationships between minority stressors and fast food consumption, meals at home, and fruit, vegetable and meat intakes.

Methodological Issues and Future Directions.

Study Design.

Virtually every study, except one, included this review utilized cross-sectional data and analyses. Six studies utilized data from GUTS, but only one study performed longitudinal data analyses. Because the GUTS cohort was first collected in the mid-1990s, more recent longitudinal studies are urgently needed, especially in light of recent changes in social attitudes surrounding sexual minorities (Eliason et al., 2015). With this dearth of longitudinal data, the conceptual developmental model presented is based on available cross-sectional studies focusing on different developmental stages. As highlighted by our review, the magnitude of sexual orientation disparities may vary across development, further necessitating longitudinal studies to track possible changes in disparities from adolescence through young adulthood.

Definitions and Measurements.

Sexual orientation.

As indicated in Table 1, studies varied greatly on their measure(s) of sexual orientation. Measures ranged from inquiring about sexual attractions, behaviors, and identity to utilizing various versions of the Kinsey scale. While different sexual orientation measures all have their own merit, inconsistencies in measurement make comparisons across studies difficult. Prior research has noted that the way sexual orientation is measured may impact results (Saewyc, 2011). Future studies should take heed in devising more consistent measures of sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation during adolescence proves especially difficult to measure in the context of emerging sexual identity. Research has shown that adolescents report sexual attraction as the more developmentally appropriate measure of sexual orientation and find questions about sexual attraction easiest to answer (Friedman et al., 2004; Saewyc, 2011); however, assessing multiple dimensions of sexual orientation becomes critical as sexual minorities age. Furthermore, additional studies are needed to assess multiple dimensions and subgroups of sexual orientation to identify which subgroups face unique health disparities (Diemer et al., 2015).

Body image.

This review highlighted wide variations in the conceptualization and measurement of body image perceptions and attitude. Most studies, however, restrict their focus to only one aspect of body image. Future research should seek to incorporate multidimensional measures of body image when assessing health disparities experienced by sexual minority youth. Minority stressors may contribute to poor body image, but few studies have linked body image to later developmental outcomes. Accordingly, future studies should test minority stressors as contributors to sexual orientation health disparities through poorer body image.

Limitations of the Current Study

Three limitations should be noted. First, guided by the primary interest in documenting sexual orientation disparities, only studies with a heterosexual referent group were included in this review. Studies that focused only on sexual minority youth are typically limited by a small sample size. Given more targeted recruitment, however, more nuanced findings on sexual orientation subgroup differences and additional moderators/mediators may be available in these studies but are not accounted for this review. Second, as eight different outcomes were examined, it was beyond the scope of the current review to quantify the magnitude of all these associations. As more studies on various outcomes emerge in this area of research, a follow-up meta-analysis on specific outcome domains may be warranted. Finally, given the severe lack of longitudinal studies in this area, the proposed developmental model was conceived by relying on existing cross-sectional studies focusing on various developmental stages. Future research is needed to empirically scrutinize each of the proposed pathways to refine the understanding of how sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors emerge across development.

Conclusion

This review summarized the current literature on sexual orientation disparities in both disordered eating and weight-related behaviors during adolescence and young adulthood through a developmental lens. Extending earlier work in this area (Calzo et al., 2017), this review articulated a conceptual developmental model of risk pathways from sexual minority status to disordered eating behaviors and highlighted the possible role of body image as a key mechanism. This review also summarized the relatively small but growing literature on sexual orientation disparities in eating behaviors and physical activity. Overall, our review indicated that sexual minority males experience disparities in multiple aspects of physical health, including all types of disordered eating behaviors, lower rates of physical activity, and concerns with body shape relative to heterosexual males. This may partially explain why sexual minority males report greater unmet medical needs relative to heterosexual males and highlight the need to improve health care access to and physician care for sexual minority males (Luk, Gilman, Haynie, & Simons-Morton, 2017). In contrast, sexual orientation disparities among females vary across development, which underscores the need to tailor prevention efforts based on developmental stage. To best advance understanding of sexual orientation disparities in disordered eating and weight-related behaviors, more longitudinal research, improved measurements of sexual orientation and body image, and consideration of sexual orientation subgroup differences and mechanistic differences are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This project was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Amgen Scholar Program at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ackard DM, Fedio G, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Britt HR (2008). Factors associated with disordered eating among sexually active adolescent males: Gender and number of sexual partners. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(2), 232–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318164230c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JP, Zou C, & Blosnich J (2015). Multiple early victimization experiences as a pathway to explain physical health disparities among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. Social Science & Medicine, 133, 111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, & Everett B (2013). Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), e16–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Ziyadeh N, Kahn JA, Camargo CA Jr., Colditz GA, & Field AE (2004). Sexual orientation, weight concerns, and eating-disordered behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 43(9), 1115–1123. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000131139.93862.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Ziyadeh NJ, Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Haines J, . . . Field AE (2009). Sexual Orientation Disparities in Purging and Binge Eating From Early to Late Adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff SM, & Pantalone DW (2014). Patterns of Disordered Eating Behavior in Women by Sexual Orientation: A Review of the Literature. Eat Disord, 22(3), 261–274. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.890458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ (2011). Gender roles, eating pathology, and body dissatisfaction in men: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 8(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Balsam KF, & Ender SR (2008). A review of obesity issues in sexual minority women. Obesity, 16(2), 221–228. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Blashill AJ, Brown TA, & Argenal RL (2017). Eating Disorders and Disordered Weight and Shape Control Behaviors in Sexual Minority Populations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(8). doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0801-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Corliss HL, Blood EA, Field AE, & Austin SB (2013). Development of muscularity and weight concerns in heterosexual and sexual minority males. Health Psychol, 32(1), 42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0028964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Masyn KE, Corliss HL, Scherer EA, Field AE, & Austin SB (2015). Patterns of body image concerns and disordered weight- and shape-related behaviors in heterosexual and sexual minority adolescent males. Dev Psychol, 51(9), 1216–1225. doi: 10.1037/dev0000027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Blood EA, Kroshus E, & Austin SB (2014). Physical Activity Disparities in Heterosexual and Sexual Minority Youth Ages 12–22 Years Old: Roles of Childhood Gender Nonconformity and Athletic Self-Esteem. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 17–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carper TL, Negy C, & Tantleff-Dunn S (2010). Relations among media influence, body image, eating concerns, and sexual orientation in men: A preliminary investigation. Body Image, 7(4), 301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Johnson C, & Grogan S (2004). Gender, sexuality, body image and eating behaviours. Journal of Health Psychology, 9(4), 505–515. doi: 10.1177/1359105304044034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolacion T, Russell S, & Sue S (2013). Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Romantic Attractions: Multiple Minority Status Adolescents and Mental Health. In (Vol. 10, pp. 200–214): Cultur Divers Ethnic Minority Psychol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, & Seeman TE (2009). Age of Minority Sexual Orientation Development and Risk of Childhood Maltreatment and Suicide Attempts in Women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 511–521. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000207793100010. doi: 10.1037/a0017163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Carra G, Calogero R, Fida R, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, & Riva G (2015). The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(8), 997–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Di Mattei VE, Bagliacca EP, Prunas A, Sarno L, Riva G, & Zanetti MA (2012). Disordered eating behaviors among Italian men: objectifying media and sexual orientation differences. Eat Disord, 20(5), 356–367. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwich L, Hymel S, & Waterhouse T (2012). School Avoidance and Substance Use Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning Youths: The Impact of Peer Victimization and Adult Support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 381–392. doi: 10.1037/a0026684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davids CM, & Green MA (2011). A preliminary investigation of body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptomatology with bisexual individuals. Sex Roles, 65(7–8), 533–547. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9963-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA, Patterson DA, & Duncan AE (2015). Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students. J Adolesc Health, 57(2), 144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2010). Friends’ Dieting and Disordered Eating Behaviors Among Adolescents Five Years Later: Findings From Project EAT. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(1), 67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, & Fogel SC (2015). An Ecological Framework for Sexual Minority Women’s Health: Factors Associated With Greater Body Mass. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(7), 845–882. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.1003007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Ingraham N, Fogel SC, McElroy JA, Lorvick J, Mauery DR, & Haynes S (2015). A Systematic Review of the Literature on Weight in Sexual Minority Women. Womens Health Issues, 25(2), 162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman MB, & Meyer IH (2007). Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(3), 218–226. doi: 10.1002/eat.20360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, & Stein TS (2002). Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 167–191. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Roberts TA (1997). Objectification theory - Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Story M, Remafedi G, Resnick MD, & Blum RW (1996). Sexual orientation and prevalence of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: a population-based study of adolescents. Int J Eat Disord, 19(2), 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Cheong J, & Wright ER (2008). Gay-related Development, Early Abuse and Adult Health Outcomes Among Gay Males. Aids and Behavior, 12(6), 891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9319-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Silvestre AJ, Gold MA, Markovic N, Savin-Williams RC, Huggins J, & Sell RL (2004). Adolescents define sexual orientation and suggest ways to measure it. J Adolesc, 27(3), 303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.adolecence.2004.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussner LM, & Smith AR (2015). It’s Not Me, It’s You: Perceptions of Partner Body Image Preferences Associated With Eating Disorder Symptoms in Gay and Heterosexual Men. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(10), 1329–1344. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1060053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettelman TE, & Thompson JK (1993). Actual Differences and stereotypical perceptions in body-image and eating disturbance: A comparison of male and female heterosexual and homosexual samples. Sex Roles, 29(7–8), 545–562. doi: 10.1007/bf00289327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, & Dunlap S (2014). Minority Stress and Substance Use in Sexual Minority Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan S (2006). Body image and health: Contemporary perspectives. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(4), 523–530. doi: 10.1177/1359105306065013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Austin SB, Goodenow CS, & Calzo JP (2014). Weight misperception and unhealthy weight control behaviors among sexual minorities in the general adolescent population. J Adolesc Health, 54(3), 296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, & Pachankis JE (2016). Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth Research Evidence and Clinical Implications. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 63(6), 985–997. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MS, & Fischer AR (2008). Examining objectification theory - Lesbian and heterosexual women’s experiences with sexual- and self-objectification. Counseling Psychologist, 36(5), 745–776. doi: 10.1177/0011000007301669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubach RD Disclosure Matters: Enhancing Patient-Provider Communication is Necessary to Improve the Health of Sexual Minority Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(5), 537–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubach RD (2017). Disclosure Matters: Enhancing Patient-Provider Communication is Necessary to Improve the Health of Sexual Minority Adolescents. In (Vol. 61, pp. 537–538): Journal of Adolescent Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities (2011). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. In: National Academies Press (US) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DC (2004). Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 823–835. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Jackson B, Haines J, & Austin SB (2014). Child abuse as a predictor of gendered sexual orientation disparities in body mass index trajectories among U.S. youth from the Growing Up Today Study. J Adolesc Health, 54(6), 730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Scherer EA, Calzo JP, Sarda V, Jackson B, Haines J, & Austin SB (2015). Sexual minority stressors, internalizing symptoms, and unhealthy eating behaviors in sexual minority youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(6), 839–852. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9718-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Baxter MG, Heatherton TF, & Joiner TE (2007). A 20-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol, 116(2), 422–432. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.116.2.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, & Stirratt MJ (2009). Social and Psychological Well-Being in Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals: The Effects of Race, Gender, Age, and Sexual Identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel SB, & Mahalik JR (2005). Body image concerns of gay men: The roles of minority stress and conformity to masculine norms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1185–1190. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.73.6.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Story M (2009). Weight Control Behaviors and Dietary Intake among Adolescents and Young Adults: Longitudinal Findings from Project EAT. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(11), 1869–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska MN, VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Lust K, Eisenberg ME, & Rosser BR (2015). Disparities in Weight and Weight Behaviors by Sexual Orientation in College Students. Am J Public Health, 105(1), 111–121. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li NP, Smith AR, Griskevicius V, Cason MJ, & Bryan A (2010). Intrasexual competition and eating restriction in heterosexual and homosexual individuals. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, & Johnson KL (2013). Minority Stress and Physical Health Among Sexual Minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(5), 521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson SK, & Sonneville KR (2017). Eating disorder symptoms among undergraduate and graduate students at 12 U.S. colleges and universities. Eat Behav, 24, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Gilman SE, Haynie DL, & Simons-Morton BG (2017). Sexual Orientation Differences in Adolescent Health Care Access and Health-Promoting Physician Advice. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(5), 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, & Thompson AL (2009). Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction, 104(6), 974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins Y, Tiggemann M, & Kirkbride A (2007). Those speedos become them: The role of self-objectification in gay and heterosexual men’s body image. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(5), 634–647. doi: 10.1177/0146167206297403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, & Lewis RJ (2016). Minority stress, body shame, and binge eating among lesbian women: Social anxiety as a linking mechanism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 428–440. doi: 10.1177/0361684316635529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews-Ewald MR, Zullig KJ, & Ward RM (2014). Sexual orientation and disordered eating behaviors among self-identified male and female college students. Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 441–444. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy JA, & Jordan J (2014). Disparate Perceptions of Weight Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Female College Students. LGBT Health, 1(2), 122–130. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH, & Poteat VP (2015). Let’s Get Physical: Sexual Orientation Disparities in Physical Activity, Sports Involvement, and Obesity Among a Population-Based Sample of Adolescents. Am J Public Health, 105(9), 1842–1848. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleman AB, Vazquez I, & Durant RH (1998). Eating patterns, physical activity, and attempts to change weight among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 22(1), 37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00162-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, & Emerson EM (2010). Mental Health Disorders, Psychological Distress, and Suicidality in a Diverse Sample of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youths. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.178319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth JL, & Cash TF (1997). Body-image attitudes: What difference does gender make? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(16), 1438–1452. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01607.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, & Austin EL (2010). Sexual Orientation, Parental Support, and Health During the Transition to Young Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Paxton SJ, Hannan PJ, Haines J, & Story M (2006). Does body satisfaction matter? Five-year longitudinal associations between body satisfaction and health behaviors in adolescent females and males. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(2), 244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]