Abstract

Forest biomass is an essential indicator for monitoring the Earth’s ecosystems and climate. It is a critical input to greenhouse gas accounting, estimation of carbon losses and forest degradation, assessment of renewable energy potential, and for developing climate change mitigation policies such as REDD+, among others. Wall-to-wall mapping of aboveground biomass (AGB) is now possible with satellite remote sensing (RS). However, RS methods require extant, up-to-date, reliable, representative and comparable in situ data for calibration and validation. Here, we present the Forest Observation System (FOS) initiative, an international cooperation to establish and maintain a global in situ forest biomass database. AGB and canopy height estimates with their associated uncertainties are derived at a 0.25 ha scale from field measurements made in permanent research plots across the world’s forests. All plot estimates are geolocated and have a size that allows for direct comparison with many RS measurements. The FOS offers the potential to improve the accuracy of RS-based biomass products while developing new synergies between the RS and ground-based ecosystem research communities.

Subject terms: Biogeography, Forest ecology, Forest ecology

| Measurement(s) | above-ground biomass • organic material |

| Technology Type(s) | tree species census • measurement method |

| Factor Type(s) | geographic location • tree species |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | forest biome |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Earth (planet) |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.9850571

Background & Summary

Global estimates of forest height, aboveground biomass (AGB) and changes over space and time are needed as both essential climate variables1 and essential biodiversity variables2, and to support international policy initiatives such as REDD+ 3. Several space-borne missions to assess forest structure and functioning, including BIOMASS (ESA), ALOS PALSAR (JAXA), GEDI (NASA) and NISAR (NASA-ISRO), will be operational in the coming years. These missions require ground-based estimates for algorithm calibration and product validation. For instance, high-quality, standardized measurements of forest biomass and height are critical for improving the accuracy of products derived from space-borne instruments. Furthermore, ensuring that different missions have access to the same set of high-quality standardized measurements for calibration and validation should vastly help improve comparability and confidence in future remote sensing (RS) products.

Remote Sensing users typically have different product requirements compared to those of the ecological and forestry communities. Namely, RS users often (1) need access to AGB estimates at the pixel level, while ecologists and foresters produce area-based estimates derived from individual trees measurements. RS users typically (2) need products at a consistent spatial resolution, while a variety of plot sizes and shapes have been adopted by ecologists and foresters. Finally, RS users (3) require AGB to be computed via globally and regionally consistent routines, while various approaches have been developed to derive AGB estimates from tree measurements. These communities also operate differently from a funding perspective. Most notably, recurrent investments are needed to maintain permanent forest plots – including censuses that temporally match RS data collection – and to ensure field and botanical staff are paid and trained, without whom the data would not be collected. In contrast, RS users typically access data provided by space-borne missions that have already been funded. Despite these differences, there is a clear need to share existing data sets for the benefit of both communities.

The Forest Observation System – FOS (http://forest-observation-system.net/) – is an international, collaborative initiative that aims to establish a global in situ forest AGB database to support Earth Observation (EO) and to encourage investment in relevant field-based measurements and research4. The FOS enables access to high-quality field data by partnering with some of the most well-established teams and networks responsible for managing permanent forest plots globally. In doing so, FOS is benefiting both the RS and ecological/forestry communities while facilitating positive interactions between them.

To this end, the FOS project has established a data sharing policy and framework that seeks to overcome existing barriers between data providers and users. For example, data made available on the FOS website are plot-aggregated (i.e., stand AGB, canopy height, etc.), while the underlying original tree-by-tree data are managed by participating ecological networks. To ensure that estimates added to the FOS are robust and consistent, a freely downloadable BIOMASS R-package5 has been upgraded, which makes the procedure for computing plot AGB estimates from tropical forest inventories transparent, standardized and reproducible. There are developments underway to make the package usable for any forest type, including boreal and temperate ecosystems. This work has been complemented by the definition of a set of technical requirements and standards aimed at ensuring data comparability4.

The FOS currently hosts aggregate data from plots contributed by several existing networks, including: the network of the Center for Tropical Forest Science – Forest Global Earth Observatory (CTFS-ForestGEO)6, the RAINFOR7, AfriTRON8 and T-FORCES9 (curated on the ForestPlots.net platform)10, the IIASA network11,12, the Tropical Managed Forests Observatory (TmFO)13 and AusCover14. These international collaborations have already (i) invested in establishing permanent sampling plots; (ii) proposed robust protocols for accurate tree mapping and measurement, which are largely standardized across networks; (iii) monitored existing plots repeatedly; and (iv) established databases with particular emphasis on data quality control10,15. As the FOS is an open initiative, additional networks (e.g., GFBI16) and teams that comply with the aforementioned criteria are welcome to join in the future.

The data presented here have been partly published before17–21, but never in such a unified and comprehensive manner. Results based on some of the plots presented here have impacted a wide range of scientific fields, including tropical forest ecology22–26, drought sensitivity of forests19,27–29, tree allometry30–33, carbon cycles21,34–36, remote sensing18,37–39, climate change8,40–43, biodiversity44–47, diversity-carbon relationships48,49 and historical forest use50,51, among others.

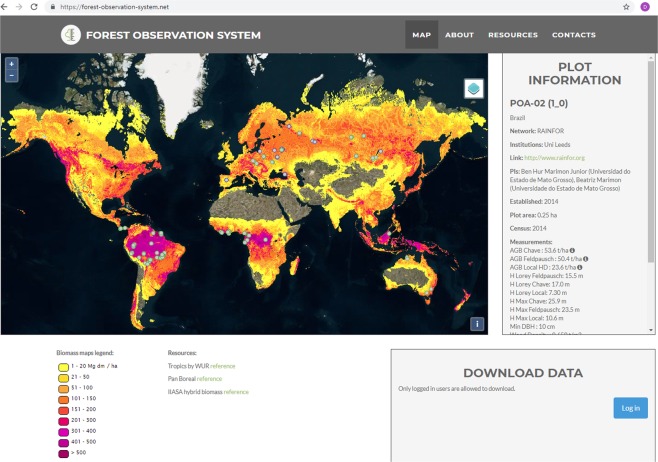

The online database (http://forest-observation-system.net/) provides open access to the canopy height and biomass estimates as well as information about the plot PIs who have granted access to the data (see Fig. 1 below).

Fig. 1.

The Forest-Observation-System.net web portal.

Methods

Within the sample plots, every stem above a defined threshold in diameter at breast height (DBH, usually 1, 5, 7 or 10 cm) was taxonomically identified and the DBH measured, avoiding any buttresses or deformities. In most plots, tree height was measured for a subset of trees that are representative of different diameter classes and tree species in order to develop site-specific height-diameter regression equations. Based on an analysis using the tropical forest plot data, as few as 40 tree height observations are sufficient for characterizing this relationship if stratified by diameter22.

All the data presented here were collected from permanent forest sample plots with known locations; accurate coordinates (with an error of less than 30 meters) have been either delivered to the FOS or will be recorded during the next census. Plot sizes are typically 1 ha in area (i.e., the median), but they can vary from 0.25 ha to 50 ha. Large plots are subdivided into 0.25 ha, i.e., 50 × 50 m sub-plots. The FOS consortium made the decision to consider only relatively large and permanent plots in order to reduce errors in georeferencing and to decrease the variability in the measured parameters. Recent research has quantified the effect of spatial resolution on the uncertainties in the AGB estimates, with sampling error dropping from 46.3% for 0.1 ha plots, to 26% and 16.5% for 0.25 ha and 1 ha plots, respectively52. Scaling up from the plot to the landscape level using lidar-derived metrics, studies have shown decreases in the RMSE for the AGB-lidar models, from 70–90 to 36–51 Mg AGB per ha, when increasing the plot size from 0.25 ha to 1 ha17,53. Clearly there are always size-effort tradeoffs, e.g., smaller plots would permit greater replication, but by focusing on larger plots that are also permanent, FOS has chosen to focus its efforts on a smaller but high-quality set of plots. Our approach, therefore, excludes the possibility of using databases of smaller plots such as those found in national forest inventories.

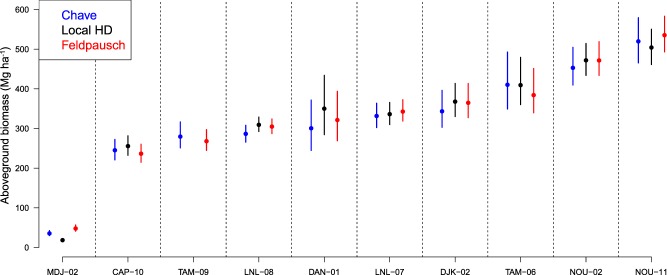

AGB and associated uncertainties were obtained using a standardized procedure implemented in the BIOMASS R-package5. For the sake of standardization, we systematically considered only trees having a diameter ≥10 cm (or a 5 cm threshold in the case where these trees contribute substantially (>5%) to the total AGB, e.g., in savannas). Taxonomy was first checked using the Taxonomic Name Resolution Service, which in turn served to assign a wood density value to each tree using the Global Wood Density Database (GWDD) as a reference54,55. Species- or genus-level averages were assigned when possible and, if not, the plot-level mean wood density was assigned to each tree species with no known wood density. Tree height was estimated in three different ways. First, when available, subsets of tree height measurements were used to build plot-specific height-diameter relationships, assuming a three-parameter Weibull model5 or a two-parameter Michaelis-Menten model, whichever provided the lowest prediction error. Secondly, the regional height-diameter models proposed by Feldpausch et al.31 were used to infer tree height. Finally, height was implicitly taken into consideration in the AGB calculation through the use of the bioclimatic predictor E proposed by Chave et al.30. Equation 7 of Chave et al.30 was used in this case while the generalized allometric model equation 4 was used otherwise (where heights were derived from local or Feldpausch height-diameter relationships). Among the three approaches, the use of a local HD model is the most accurate. However, local height measurements are not systematically available for all plots. The Chave et al. (2014) and Feldpausch et al. (2012) approaches are both an alternative to the use of a local HD model but independent validation (e.g., Fig. 2) has shown that their relative performance varies among locations. Thus, the most conservative approach is to provide the three estimates so that the uncertainty associated with the HD relationship can be assessed.

Fig. 2.

An example of the AGB estimation with the BIOMASS R-package. MDJ-02, CAP-10 and other indexes on the horizontal axis are Plot IDs. The vertical axis is AGB in Mg ha−1 and the error bar represents the credibility interval at 95% of the stand AGB value following error propagation.

Errors associated with each of these steps (i.e., DBH measurement, wood density, tree height) were propagated through a Monte Carlo scheme to provide mean AGB estimates with associated credibility intervals (Fig. 2).

Boreal and temperate plots (representing 11% of the total number of sub-plots) were processed manually using similar steps. Species-specific allometric equations56 allowed the stem volume to be estimated based on the height and DBH measurements. Biomass conversion and expansion factors57 were used to estimate AGB from the stem volume taking the tree age, site index and stocking into account. The next version of the BIOMASS R-package will be capable of processing boreal and temperate data in addition to tropical.

Data Records

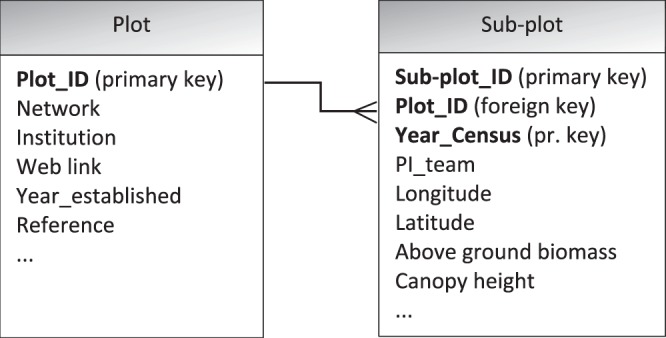

The data in FOS58 are organized in a hierarchical structure (Fig. 3). The Plot description includes a link to the institution and network. The central part of the database is the Sub-plot table, where geolocation, the date of the census, the people who manage the specific plots, the AGB and the canopy height are stored.

Fig. 3.

The database structure of the plot information.

The FOS does not store individual tree-level information, only plot-level aggregates. Users interested in tree-level information can contact the contributing networks or the plot PIs using the links provided in the Plot table.

The details of the fields found in the two linked tables of Fig. 3 are provided below.

Plot description

Plot_ID – unique plot ID

Country_Name – Name of the country

Network – the name of the network (e.g., RAINFOR)

Institution – the institution that carried out the measurements

Link – web link to the data provider

Year_established – the year when the plot was established

Reference – a reference to the publications

Other_measurements – list of parameters measured on the plot

Biomass_processing_protocol – file name of the biomass processing protocol (available at Data Package 1), which contains the R code, the variables assigned and the intermediate results.

Sub-plot description

Sub-plot_ID – unique sub-plot ID

Plot_ID – link to the Plot description table

Year_census – year of the census

PI_team – List of Principal Investigator(s)

Lat_cnt – Latitude of the center of the plot

Long_cnt – Longitude of the center of the plot

Altitude (m a.s.l.)

Slope (degree)

Plot_area (ha)

Plot_shape (e.g., rectangle, circle, plus dimensions)

Forest_status – forest description, including age, successional stage, disturbances, etc.

Min_DBH – Minimum diameter of trees at breast height included in the census (cm)

- H_max – height of the tallest tree (m)

- Hmax local – tallest tree measured or estimated from local H = f(DBH) curve (m)

- Hmax Chave – maximum height estimated from the curve by Chave (m)

- Hmax Feldpausch – maximum height estimated from the curve by Feldpausch (m)

- AGB – Above ground biomass (Mg ha−1)

- AGB_local – aboveground biomass (Mg ha−1) estimated using local equations or equation 4 in Chave30 with wood density, DBH and H derived from local height-diameter relationships.

- Cred_2.5 – lower bound of 95% credibility interval (Mg ha−1)

- Cred_97.5– upper bound of 95% credibility interval (Mg ha−1)

- AGB_Chave – aboveground biomass (in Mg ha−1) estimated using equation 7 in Chave30 with wood density, DBH and H implicitly taken into consideration through the use of the bioclimatic predictor E

- Cred_2.5 – lower bound of 95% credibility interval (Mg ha−1)

- Cred_97.5 – upper bound of 95% credibility interval (Mg ha−1)

Wood_density - mean wood density of the trees (g cm−3)

GSV – growing stock volume (m3 ha−1)

BA – basal area (m2 ha−1)

Ndens – number of trees per hectare

Note that we have merged the Plot and Sub-plot tables in the data package associated with this paper58 for the user’s convenience.

Technical Validation

The key predictive variables of AGB are tree dimensions (primarily diameter and height) and taxonomic identity, which is responsible for explaining most tree-to-tree variations through interspecific wood density variations59. The procedures for ensuring the quality of the data collected are as follows:

On-site measurement accuracy. To ensure diameter accuracy and consistency among and within censuses, field teams follow standard forest inventory protocols for the correct choice of the Point of measurement (POM). For example, the RAINFOR protocol for tropical forests60 records each POM by painting the location on each tree to ensure that subsequent measurements can be performed at the same point. For tree height, the consistency of the height measurement is ensured by having a designated, trained operator who works at multiple sites using the same instrument. At some sites, double measurements of height (from different positions) have been carried out, and mean values have been used as the height of the individual trees. For species identification, the reliability in highly diverse tropical plots is important; hence, the tree and plot AGB is estimated by taking the species-level variability in wood density into account61. This is supported by collecting botanical vouchers from every taxon (or potential taxon) in the field. In many cases, these vouchers have been deposited in recognized regional herbaria, identified by botanical experts, and where possible, made available electronically (e.g., via ForestPlots.net). However, voucher collection is not currently a standard protocol for every plot in the FOS.

Multiple censusing. By working primarily with re-censused permanent plots rather than single census plots, we have ensured that the uncertainties are reduced because almost every tree has been measured at least twice by the time of the focal census, thus providing the opportunity to correct any errors that may have been made previously, through the identification of spurious values. Repeat censuses also provide more opportunities to improve species identification by increasing the chance of encountering fertile material (see the next step).

Post fieldwork data processing, e.g., by identifying trees to species level. Species identification can be extremely challenging in tropical forests due to their diversity and the fact that most trees lack flowers or fruits when inventoried. Botanical identity is a key control on the AGB through its effect on wood density. To explore the reliability of identification in some of the most diverse RAINFOR sites in western Amazonia, PIs have separated the tree species assemblages into several larger taxonomic groups. As reported by Baker et al.62, taxonomic specialists for each group have then assessed the accuracy of the species identifications of the herbarium collections using 18 different botanists across 60 plots during the past 30 years. Overall, even in taxonomically difficult groups where species are often very rare, 75% of tree species were correctly identified.

Common protocols for potential error detection. These protocols have been developed by contributing networks, e.g., by flagging trees for attention that have declined by more than 5 mm in diameter. This allows trees to be detected that have shrunk between two censuses, and whether that individual is dead/rotten. Potential issues are flagged in order to be checked against existing field notes, and during the following census. Thus, as mentioned previously, repeat censuses provide more opportunities to improve data quality as compared to single-census plots.

Within-network collaboration. Data quality is further enhanced through the exchange of ideas between experts at different sites and between nations, through the use of common data analysis protocols (i.e., allometric equations, R packages, etc.), and by promoting shared publications.

Cross-network collaboration. In the FOS, by applying a uniform R script for data aggregation and AGB estimation, potential biases from using different height-diameter, wood density and allometric relations are strongly reduced.

The distribution of FOS plots by continent is presented in Table 1. Africa, Europe and South America are represented by similar numbers of locations (i.e., 62–80 plots) and contribute more than 80% of the plots at the time of publication, but in terms of coverage, South America alone comprises 49% of the forest area covered.

Table 1.

Distribution of records by continents (as of December 2018).

| Continent/regions | Number of plots | Number of sub-plots | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 62 | 338 | 85 |

| Asia | 29 | 46 | 20 |

| Australia | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Central America | 21 | 278 | 69 |

| Europe | 80 | 146 | 42 |

| South America | 78 | 833 | 209 |

| Total | 274 | 1645 | 428 |

The IIASA network provides the highest number of plot locations to FOS (Table 2), while the TmFO network contributes the most in terms of areal coverage.

Table 2.

The distribution of records by participating networks (as of December 2018).

| Network | Number of plots | Number of sub-plots | Area, ha |

|---|---|---|---|

| AfriTRON | 46 | 178 | 45 |

| AusCover | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| CTFS-ForestGEO | 2 | 300 | 75 |

| IIASA | 126 | 258 | 78 |

| RAINFOR | 52 | 288 | 72 |

| T-Forces | 3 | 12 | 3 |

| TmFO | 17 | 500 | 125 |

| Unaffiliated to network | 24 | 105 | 27 |

| Total | 274 | 1645 | 428 |

The range of values of major forest parameters represented in the FOS database is shown in Table 3. The maximum AGB value (918 Mg ha−1) and canopy height (41.7 m) at a 0.25 ha sub-plot were recorded in Lopé, Gabon. Some savannah sub-plots (e.g., in Gabon) have a few or no trees >5 cm dbh, which leads to low or no biomass estimation. The tallest trees (60.1 m) was found in Costa Rica and the maximum basal area (85.6 m2 ha−1) was found in the Caucasus, Russia.

Table 3.

The range of major forest parameters in the FOS database (as of December 2018).

| Parameters | min | Max | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | −36.52 | 64.51 | 5.26 |

| Longitude | −83.58 | 148.92 | −52.92 |

| Plot area | 0.25 | 50 | 1.0 |

| Sub-plot area | 0.0625 | 2.89 | 0.25 |

| Year established | 1955 | 2017 | 2012 |

| Year of census | 1999 | 2018 | 2012 |

| Min DBH, cm | 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Height Lorey’s, m | 2.3 | 41.7 | 26.8 |

| Height max, m | 3.6 | 60.1 | 39.3 |

| AGB, t ha−1 | 0.3 | 933 | 258 |

| Basal area, m−2 ha−1 | 0.05 | 85.58 | 28.32 |

| Tree density, trees ha−1 | 4 | 1800 | 452 |

Table 4 contains information about the AGB for different biomes and globally. As expected, the average AGB increases from boreal to temperate and then from temperate to tropical forests.

Table 4.

The distribution of aboveground biomass data (t ha−1) by biome in the FOS database (as of December 2018).

| Biome | Min | Max | Average | StdDev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boreal | 1 | 324 | 99 | 68 |

| Temperate | 48 | 609 | 211 | 75 |

| Tropics | 0.3 | 933 | 311 | 132 |

| Global | 0.3 | 933 | 299 | 133 |

Usage Notes

This data set will be essential for validating and calibrating satellite observations and forest biometric models. The focus is to provide ground support for current and planned space-borne missions, such as NASA GEDI (https://gedi.umd.edu/), NASA-ISRO NISAR (https://nisar.jpl.nasa.gov/), JAXA ALOS PALSAR (http://global.jaxa.jp/projects/sat/alos/) and ESA BIOMASS (https://earth.esa.int/web/guest/missions/esa-future-missions/biomass), which are aimed at retrieving forest structure parameters such as forest height and biomass.

At this stage, we are making no claims regarding the statistical robustness of the FOS data set for global or regional biomass estimations. Instead our aim is to present uniformly processed data on forest biomass from available locations (see Table 1). One of the main goals of the FOS is to highlight gaps in the observations.

Using sub-plot data for validation of RS data might lead to spatial autocorrelation problems so possible solutions would be to use a plot average, use only values from the plot or test for the presence of spatial autocorrelation.

This data package contains geographical coordinates rounded to 2 digits after decimal point (up to 1 km at equator). The most up-to-date extended data set with accurate geolocation is available in the FOS portal: https://forest-observation-system.net/

The FOS initiative depends on the contributions of high-quality forest plot data from participating networks. The fair use of the data presented here requires respecting the efforts and rights of the partners and supporting the long-term future of these observational efforts. The data set will be licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which means that it will be fully open even for commercial use but requires acknowledgment of the PIs and plot owners. We would also appreciate that all users of the FOS data either share their own data via the FOS, and/or commit to collaboratively funding new censuses and the expansion of existing plot networks.

Acknowledgements

This study has been partly supported by the IFBN (4000114425/15/NL/FF/gp) and CCI Biomass (4000123662/18/I-NB) projects funded by ESA; the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science and Research (BMWF-4.409/30-II/4/2009); the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW2007-11); the Research Project AGL2009-08562, Ministry of Science’s Research and Development, Spain; the Project LIFE+ “ForBioSensing PL Comprehensive monitoring of stand dynamics in Białowieża Forest supported with remote sensing techniques” cofounded by Life+ UE program (contract number LIFE13 ENV/PL/000048) and The National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management in Poland (contract number 485/2014/WN10/OP-NM-LF/D); the Brazilian National Council of Science and Technology (PVE project #401279/2014-6 and PELD (LTER) project #441244/2016-5); USAID (1993–2006); Brazilian National Council of Science and Technology-CNPq (Processes 481097/2008-2, 201138/2012-3); Foundation for Research Support of the State of Sao Paulo-FAPESP (Processes 2013/16262-4, 2013/50718-5). European Research Council Advanced Grant T-FORCES (291585); the Russian State Assignment of the CEPF RAS no. АААА-А18-118052400130-7. The Russian Science Foundation supported data processing of the plot data from Russia (project no. 19-77-30015). We would like to thank Shell Gabon and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute for funding the collection of the RABI data (contribution No 172 of the Gabon Biodiversity Program). We would also like to thank Alexander Parada Gutierrez, Javier Eduardo Silva-Espejo, Jon Lloyd, and Olaf Banki for sharing their plot data. JC is funded by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (CEBA, ref. ANR-10-LABX-25-01; TULIP: ANR-10-LABX-0041).

Author Contributions

The co-authors have contributed with their own data and are indicated as principal investigators in the plot table58. Stuart Davies, Simon Lewis, Oliver Phillips, Plinio Sist and Dmitry Schepaschenko are coordinating contributing networks and have managed the process of providing specific plot data to the FOS. Maxime Réjou-Méchain, Jérôme Chave and Bruno Hérault have developed the R BIOMASS package. Maxime Réjou-Méchain and Nicolas Labrière have processed the initial tree-level data to the plot-level, as presented in the paper. Christoph Perger and Christopher Dresel developed the database structure and the web interface for the FOS. Dmitry Schepaschenko, Jérôme Chave, Oliver Phillips, Simon Lewis, Maxime Réjou-Méchain have written the paper. Edits and suggestions for improvements were provided by Nicolas Labrière, Bruno Herault, Florian Hofhansl, Klaus Scipal, Steffen Fritz, Linda See, Sylvie Gourlet-Fleury, Géraldine Derroire, Ted R. Feldpausch, Ruben Valbuena, Krzysztof Stereńczak, Plinio Sist and Wolfgang Wanek. All remaining authors have contributed data to the FOS.

Code Availability

The BIOMASS R-package is an open source library available from the CRAN R repository. The development version is publicly available and can be found on the GitHub platform at: https://github.com/AMAP-dev/BIOMASS. Furthermore, the BIOMASS R-package is accompanied by an open access paper describing the functionality in more detail5.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bojinski S, et al. The Concept of Essential Climate Variables in Support of Climate Research, Applications, and Policy. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014;95:1431–1443. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00047.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira HM, et al. Essential Biodiversity Variables. Science. 2013;339:277–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1229931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schepaschenko, D. et al. Global biomass information: from data generation to application. In Handbook of Clean Energy Systems1, 11–33 (Wiley, 2015).

- 4.Chave Jérôme, Davies Stuart J., Phillips Oliver L., Lewis Simon L., Sist Plinio, Schepaschenko Dmitry, Armston John, Baker Tim R., Coomes David, Disney Mathias, Duncanson Laura, Hérault Bruno, Labrière Nicolas, Meyer Victoria, Réjou-Méchain Maxime, Scipal Klaus, Saatchi Sassan. Ground Data are Essential for Biomass Remote Sensing Missions. Surveys in Geophysics. 2019;40(4):863–880. doi: 10.1007/s10712-019-09528-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Réjou-Méchain Maxime, Tanguy Ariane, Piponiot Camille, Chave Jérôme, Hérault Bruno. biomass : an r package for estimating above-ground biomass and its uncertainty in tropical forests. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2017;8(9):1163–1167. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson‐Teixeira KJ, et al. CTFS-ForestGEO: a worldwide network monitoring forests in an era of global change. Glob. Change Biol. 2015;21:528–549. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhi Y, et al. An international network to monitor the structure, composition and dynamics of Amazonian forests (RAINFOR) J. Veg. Sci. 2002;13:439–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2002.tb02068.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis SL, et al. Increasing carbon storage in intact African tropical forests. Nature. 2009;457:1003–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature07771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qie L, et al. Long-term carbon sink in Borneo’s forests halted by drought and vulnerable to edge effects. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1966. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01997-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez‐Gonzalez G, Lewis SL, Burkitt M, Phillips OL. ForestPlots.net: a web application and research tool to manage and analyse tropical forest plot data. J. Veg. Sci. 2011;22:610–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01312.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schepaschenko D, et al. A dataset of forest biomass structure for Eurasia. Sci. Data. 2017;4:201770. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pietsch, S. A. Modelling ecosystem pools and fluxes. Implementation and application of biogeochemical ecosystem models. (BOKU, 2014).

- 13.Sist P, et al. The Tropical managed Forests Observatory: a research network addressing the future of tropical logged forests. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2015;18:171–174. doi: 10.1111/avsc.12125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TERN Auscover. Biomass Plot Library - National collation of tree and shrub inventory data, allometric model predictions of above and below-ground biomass, Australia. Made available by the AusCover facility of the Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN) (2016).

- 15.Condit RS, et al. Tropical forest dynamics across a rainfall gradient and the impact of an El Niño dry season. J. Trop. Ecol. 2004;20:51–72. doi: 10.1017/S0266467403001081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang J, et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science. 2016;354:196. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labrière N, et al. In situ reference datasets from the TropiSAR and AfriSAR campaigns in support of upcoming spaceborne biomass missions. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018;11:3617–3627. doi: 10.1109/JSTARS.2018.2851606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor P, et al. Landscape-scale controls on aboveground forest carbon stocks on the Osa peninsula, Costa Rica. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0126748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofhansl F, et al. Sensitivity of tropical forest aboveground productivity to climate anomalies in SW Costa Rica. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2014;28:1437–1454. doi: 10.1002/2014GB004934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piponiot C, et al. Carbon recovery dynamics following disturbance by selective logging in Amazonian forests. eLife. 2016;5:e21394. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis Simon L, et al. Above-ground biomass and structure of 260 African tropical forests. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013;368:20120295. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan MJP, et al. Field methods for sampling tree height for tropical forest biomass estimation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018;9:1179–1189. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ter Steege H, et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora. Science. 2013;342:1243092. doi: 10.1126/science.1243092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker TR, et al. Fast demographic traits promote high diversification rates of Amazonian trees. Ecol. Lett. 2014;17:527–536. doi: 10.1111/ele.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MO, et al. Variation in stem mortality rates determines patterns of above-ground biomass in Amazonian forests: implications for dynamic global vegetation models. Glob. Change Biol. 2016;22:3996–4013. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre‐Gutiérrez J, et al. Drier tropical forests are susceptible to functional changes in response to a long-term drought. Ecol. Lett. 2019;22:855–865. doi: 10.1111/ele.13243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips OL, et al. Drought Sensitivity of the Amazon Rainforest. Science. 2009;323:1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1164033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esquivel‐Muelbert A, et al. Seasonal drought limits tree species across the Neotropics. Ecography. 2017;40:618–629. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldpausch TR, et al. Amazon forest response to repeated droughts. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2016;30:964–982. doi: 10.1002/2015GB005133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chave J, et al. Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Glob. Change Biol. 2014;20:3177–3190. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldpausch TR, et al. Tree height integrated into pantropical forest biomass estimates. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:3381–3403. doi: 10.5194/bg-9-3381-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastin J-F, et al. Pan-tropical prediction of forest structure from the largest trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018;27:1366–1383. doi: 10.1111/geb.12803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldpausch TR, et al. Height-diameter allometry of tropical forest trees. Biogeosciences. 2011;8:1081–1106. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-1081-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips OL. Changes in the Carbon Balance of Tropical Forests: Evidence from Long-Term Plots. Science. 1998;282:439–442. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slik JWF, et al. Large trees drive forest aboveground biomass variation in moist lowland forests across the tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013;22:1261–1271. doi: 10.1111/geb.12092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubau W, et al. The persistence of carbon in the African forest understory. Nat. Plants. 2019;5:133. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchard ETA, et al. Markedly divergent estimates of Amazon forest carbon density from ground plots and satellites. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014;23:935–946. doi: 10.1111/geb.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santoro M, et al. Forest growing stock volume of the northern hemisphere: Spatially explicit estimates for 2010 derived from Envisat ASAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015;168:316–334. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2015.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valbuena R, et al. Enhancing of accuracy assessment for forest above-ground biomass estimates obtained from remote sensing via hypothesis testing and overfitting evaluation. Ecol. Model. 2017;366:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas CD, et al. Extinction risk fromclimate change. Nature. 2004;427:145–148. doi: 10.1038/nature02121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esquivel‐Muelbert A, et al. Compositional response of Amazon forests to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2019;25:39–56. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brienen RJW, et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature. 2015;519:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan Y, et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science. 2011;333:988–993. doi: 10.1126/science.1201609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips OL, Hall P, Gentry AH, Sawyer SA, Vásquez R. Dynamics and species richness of tropical rain forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994;91:2805–2809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Souza FC, et al. Evolutionary heritage influences Amazon tree ecology. Proc R Soc B. 2016;283:20161587. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coronado ENH, et al. Phylogenetic diversity of Amazonian tree communities. Divers. Distrib. 2015;21:1295–1307. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ter Steege H, et al. Estimating the global conservation status of more than 15,000 Amazonian tree species. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1500936. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan MJP, et al. Diversity and carbon storage across the tropical forest biome. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:39102. doi: 10.1038/srep39102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fauset S, et al. Hyperdominance in Amazonian forest carbon cycling. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6857. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levis C, et al. Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition. Science. 2017;355:925–931. doi: 10.1126/science.aal0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willcock S, et al. Land cover change and carbon emissions over 100 years in an African biodiversity hotspot. Glob. Change Biol. 2016;22:2787–2800. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Réjou-Méchain M, et al. Local spatial structure of forest biomass and its consequences for remote sensing of carbon stocks. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:6827–6840. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-6827-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knapp N, Fischer R, Huth A. Linking lidar and forest modeling to assess biomass estimation across scales and disturbance states. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018;205:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2017.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chave J, et al. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol. Lett. 2009;12:351–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zanne AE, 2009. Global Wood Density Database. Dryad Digital Repository. [DOI]

- 56.Zagreev, V. V. et al. All-Union regulations for forest mensuration. (Kolos, 1992).

- 57.Schepaschenko D, et al. Improved estimates of biomass expansion factors for Russian forests. Forests. 2018;9:312. doi: 10.3390/f9060312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schepaschenko D, 2019. A global reference dataset for remote sensing of forest biomass. The Forest Observation System approach. IIASA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Baker TR, et al. Variation in wood density determines spatial patterns in Amazonian forest biomass. Glob. Change Biol. 2004;10:545–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00751.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marthews, T. R. et al. Measuring tropical forest carbon allocation and cycling: A RAINFOR-GEM field manual for intensive census plots (v 3.0). Manual. (Global Ecosystems Monitoring network, 2014).

- 61.Phillips OL, et al. Species matter: wood density influences tropical forest biomass at multiple scales. Surv. Geophys. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10712-019-09540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baker TR, et al. Maximising synergy among tropical plant systematists, ecologists, and evolutionary biologists. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017;32:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Zanne AE, 2009. Global Wood Density Database. Dryad Digital Repository. [DOI]

- Schepaschenko D, 2019. A global reference dataset for remote sensing of forest biomass. The Forest Observation System approach. IIASA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The BIOMASS R-package is an open source library available from the CRAN R repository. The development version is publicly available and can be found on the GitHub platform at: https://github.com/AMAP-dev/BIOMASS. Furthermore, the BIOMASS R-package is accompanied by an open access paper describing the functionality in more detail5.