Abstract

Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are cellular extensions enabling cytosol-to-cytosol intercellular interaction between numerous cell types including macrophages. Previous studies of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) transplantation for the lysosomal storage disorder cystinosis have shown that HSPC-derived macrophages form TNTs to deliver cystinosin-bearing lysosomes to cystinotic cells, leading to tissue preservation. Here, we explored if macrophage polarization to either proinflammatory M1-like M(LPS/IFNγ) or anti-inflammatory M2-like M(IL-4/IL-10) affected TNT-like protrusion formation, intercellular transport and, ultimately, the efficacy of cystinosis prevention. We designed new automated image processing algorithms used to demonstrate that LPS/IFNγ polarization decreased bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) formation of protrusions, some of which displayed characteristics of TNTs, including cytoskeletal structure, 3D morphology and size. In contrast, co-culture of macrophages with cystinotic fibroblasts yielded more frequent and larger protrusions, as well as increased lysosomal and mitochondrial intercellular trafficking to the diseased fibroblasts. Unexpectedly, we observed normal protrusion formation and therapeutic efficacy following disruption of anti-inflammatory IL-4/IL-10 polarization in vivo by transplantation of HSPCs isolated from the Rac2−/− mouse model. Altogether, we developed unbiased image quantification systems that probe mechanistic aspects of TNT formation and function in vitro, while HSPC transplantation into cystinotic mice provides a complex in vivo disease model. While the differences between polarization cell culture and mouse models exemplify the oversimplicity of in vitro cytokine treatment, they simultaneously demonstrate the utility of our co-culture model which recapitulates the in vivo phenomenon of diseased cystinotic cells stimulating thicker TNT formation and intercellular trafficking from macrophages. Ultimately, we can use both approaches to expand the utility of TNT-like protrusions as a delivery system for regenerative medicine.

Subject terms: Cellular imaging, Membrane trafficking, Lysosomes, Gene therapy, Monocytes and macrophages

Introduction

Intercellular communication is essential to maintain and potentially restore homeostasis in multicellular organisms. Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are one interaction pathway consisting of long actin-rich membranous extensions capable of forming cytosolic connections between distant cells1–3. TNTs have been observed in vitro and in vivo facilitating transfer of molecular cargos ranging from electrical signals to organelles to pathogens4–6. Mechanistic investigations of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) transplantation therapy for the lysosomal storage disorder cystinosis revealed HSPC-derived macrophages deliver functional lysosomal protein cystinosin through TNTs to diseased tissue, resulting in lifelong prevention of disease progression in the mouse model7–9.

Cystinosin is ubiquitously expressed within the lysosomal membrane to export cystine into the cytosol10. However, loss-of-function mutations in the CTNS gene cause lysosomal cystine accumulation and crystallization leading to multi-organ failure11,12. Current therapies merely ameliorate symptoms and delay disease progression13. Our group has pioneered the use of HSPC transplantation as a promising new therapy for cystinosis with translation of this approach into an autologous gene-corrected HSPC transplantation clinical trial for human cystinosis patients underway14–16.

Due to cystinosin being a non-secreted transmembrane protein, the ubiquitous prevention of pathogenic cell damage using HSPCs was unexpected until the mechanism of trafficking was shown to involve TNT-mediated delivery of healthy lysosomes from HSPC-derived macrophages to diseased tissue7. While many studies have demonstrated how pathogens like HIV17 or malignancies like gliomas18 can hijack TNTs, the structures also present an intriguing potential delivery system of therapeutic proteins to treat genetic diseases19. Following HSPC transplantation, kidney macrophages formed TNTs that crossed the basement membrane and rescued proximal tubule cells by delivering cystinosin-bearing lysosomes7. The same mechanism has also been observed in the cornea and thyroid of transplanted cystinotic mice8,9, as well as in the X-linked tubulopathy Dent disease20. In addition, studies of HSPC transplantation as treatment for the mitochondrial neurodegenerative disorder Friedreich’s Ataxia reveal microglial correction of neurons, potentially through TNTs21. Taken together, these data indicate a prolific ability of phagocytic cells to widely disseminate therapeutic molecules via TNT trafficking.

The plasticity of macrophages allows them to fulfill numerous biological functions ranging from proinflammatory roles in both arms of the immune system to immunomodulatory activities vis-à-vis tissue repair, homeostasis and resolution of inflammation. Traditionally, these distinct phenotypic behaviors have been classified as either proinflammatory mediators of a type I immune response (M1 or classical activation) versus. immunomodulatory tissue-remodelers (M2 or alternative)22,23. However, this model risks oversimplification of a seamless phenotypic spectrum into a false dichotomy masking in vivo macrophage complexity, where these subtypes are dynamically changing in response to the cues received from the microenvironment, and thus never cleanly delineated24,25.

In the current study, we investigated macrophage-mediated TNT formation and intercellular trafficking. Using novel image analysis platforms, we report that in vitro proinflammatory macrophage stimulation suppressed both TNT-like protrusion formation as well as intercellular organelle trafficking. In contrast, macrophages co-cultured with diseased Ctns−/− fibroblasts exhibited increased lysosomal and mitochondrial intercellular trafficking along with more frequent formation of larger protrusions. These data suggest that diseased cells stimulate TNT formation towards a thicker phenotype, which has been shown to more effectively transport organelles such as macrophages and intracellular vesicles26. Unexpectedly, in vivo enrichment of proinflammatory macrophages showed similar disease rescue following Rac2−/− HSPC transplantation in Ctns−/− mice compared to wild-type (WT) mice. This discrepancy between mice and co-cultures highlights the well-known dangers of relying solely on in vitro polarization models where cytokine stimulation pushes macrophages to non-physiological polarization phenotypes. That said, increased macrophage-derived thicker TNT formation and trafficking activity seen in unstimulated cystinotic co-cultures effectively models in vivo observations of enhanced macrophage recruitment and intercellular lysosomal delivery after HSPC transplantation7. Using both cells and transplanted mice, we can therefore probe aspects of TNTs induced when stress on a separate cellular population is stimulating macrophage TNT formation in a paracrine fashion. Ultimately, a detailed understanding of these processes could ultimately better explain and enhance the effective delivery of non-secreted genetic products.

Results

Macrophage membrane protrusions are suppressed by proinflammatory stimulation but enhanced by co-culture with diseased cells

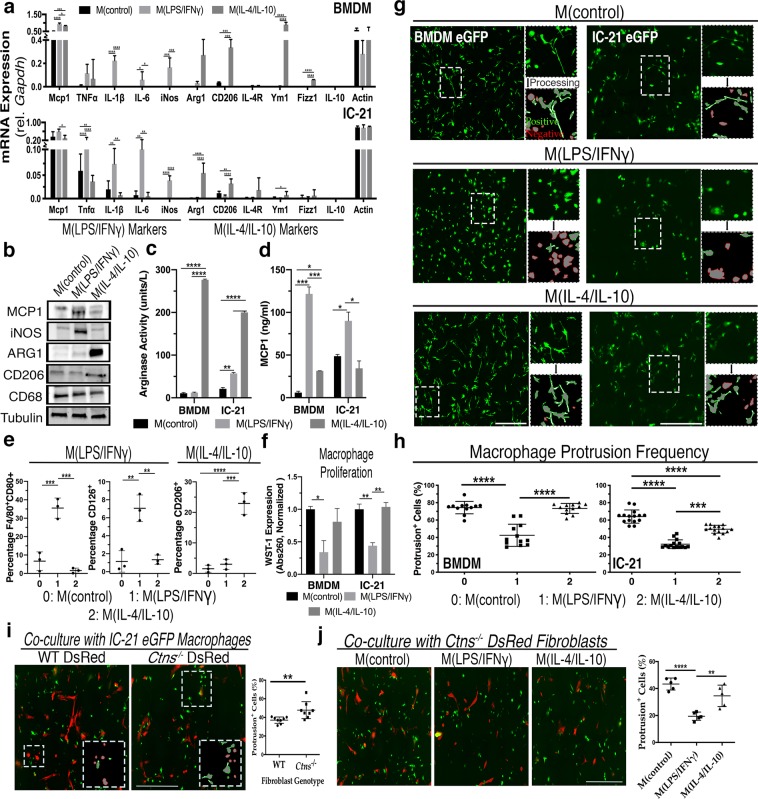

Previous work has uncovered that proinflammatory bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) display a more rounded ameboid morphology compared to unstimulated or anti-inflammatory cells27. To investigate tunneling nanotube (TNT) formation in this context, we treated primary murine BMDMs and the immortalized IC-21 peritoneal macrophage cell line with either LPS/IFNγ, directing differentiation towards proinflammatory M1-like cells, M(LPS/IFNγ), or with IL-4/IL-10 for differentiation towards immunomodulatory M2-like macrophages, M(IL-4/IL-10). Using a variety of assays to characterize expression of well-established macrophage polarization markers, we rigorously validated our in vitro polarization experimental system. First, we analyzed differentially expressed mRNAs and proteins, observing increased expression of numerous proinflammatory markers such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos), interleukin-6 (Il-6) and interleukin-1β (Il-1β) following LPS/IFNγ treatment, as well as upregulation of anti-inflammatory markers such as Cd206, Ym1 and Fizz1 after IL-4/IL-10 stimulation (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Fig. S1)28,29. Furthermore, M(IL-4/IL-10) displayed greater enzymatic activity of arginase-1 (ARG1), an important biosynthetic regulator of tissue repair, while M(LPS/IFNγ) increased extracellular secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) (Fig. 1c,d), a potent proinflammatory chemokine that regulates migration and infiltration of macrophages30. Finally, polarized BMDMs were analyzed by flow cytometry where we observed expected changes in expression of proinflammatory markers CD80 and CD126 or anti-inflammatory CD206 (Fig. 1e)31. To assess macrophage viability following polarization, we also measured cell proliferation using WST-1, which decreased following LPS/IFNγ but not IL-4/IL-10 stimulation in both BMDMs (P = 0.0015) and IC-21 macrophages (P < 0.0001) compared to non-treated controls (Fig. 1f). In contrast, apoptosis measured by Annexin V and Propidium Iodide-stained cells did not vary between treatment groups (data not shown). Taken together, in vitro treatment yields the anticipated changes in marker expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, confirming that our system replicates the expected polarization findings.

Figure 1.

LPS/IFNγ polarization suppresses protrusion formation in BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages. (a) Bar graph representing mRNA expression of M(LPS/IFNγ) and M(IL4/IL10) markers relative to housekeeping control Gapdh in BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages after 48-hour pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization compared to non-treated cells (n = 5). (b) Representative immunoblots depicting polarization-associated signature protein expression in pro- and anti-inflammatory IC-21 macrophages and untreated controls. MCP1 and iNOS are M(LPS/IFNγ) markers, while ARG1 and CD206 are M(IL-4/IL-10) markers. CD68 is a pan-macrophage marker, and tubulin serves as the loading control (n = 2–4). (c) Graph depicts normalized colorimetric measurements of the M(IL-4/IL-10) marker ARG1 enzymatic activity from cell lysate following independent polarization treatments (n = 3). (d) Bar graph depicting normalized MCP1 cytokine secretion into media following polarization as measured by ELISA (n = 3). (e) Bar graphs representing flow cytometry analysis showing frequency of expression of M(LPS/IFNγ) markers CD80 and CD126 or M(IL-4/IL-10) marker CD206 following BMDM polarization (n = 3). (f) Bar graphs presenting normalized colorimetric absorbance values measuring cell proliferation using WST-1 cell proliferation reagent in BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages acquired three days post polarization treatment (n = 3). (g) Representative wide-field fluorescent images of control vs. M(LPS/IFNγ)- or M(IL4/IL10)-polarized BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages. Larger micrographs are stitched images of 5 × 5 individual tile. Zoomed inserts demonstrate automated image processing selecting for protrusion-positive (green) or negative (red) cells. See Supplementary Fig. S1 for method description and examples. (h) Percentile quantification of protrusion-positive cells in polarized BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages. Each data point in the box-and-whisker histogram is one stitched region with five regions analyzed per experiment (n = 3). (i) Representative fluorescent images of eGFP+ IC-21 co-cultures grown for three days with either WT (left) or Ctns−/− (right) DsRed+ fibroblasts. Boxed insert shows automated protrusion detection analysis with percentage of eGFP+ protrusion-positive cells shown in histogram (n = 3). (j) Representative fluorescent images of polarized eGFP+ IC-21 macrophage and Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblast co-cultures. Histogram illustrates percentage of control or M(LPS/IFNγ) and M(IL4/IL10) macrophages with protrusions (n = 3). All scale bars: 500 µM. All bar graphs shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values were determined by either one-way ANOVA or student’s t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Upon imaging of treated cells, we also observed the expected shift of M(LPS/IFNγ) morphology to a more rounded phenotype in both BMDMs and IC-21 (Fig. 1g). We developed an image analysis workflow using ImagePro Premier to automatically detect and quantify fluorescent membrane protrusions using customizable morphological filtration based on characteristics such as length, width and circularity (Supplementary Fig. S2). By analyzing larger stitched images acquired using the wide-field Keyence fluorescence microscope, our high-throughput method enables automated, rapid and unbiased analysis of fluorescent cellular protrusions from dozens to hundreds of cells at once. Using this algorithm, we observed a significant reduction of approximately 50% in the protrusion frequency of BMDMs and IC-21 macrophages following LPS/IFNγ stimulation compared to non-treated macrophages (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1h). In contrast, M(IL-4/IL-10) BMDM protrusion frequency was statistically indistinguishable from control, while IC-21 displayed a modest decrease.

We sought to extend on our protrusion frequency findings by stimulating BMDMs with each cytokine or stimulant individually. We observe that either LPS or IFNγ by themselves are equally effective as when combined to reduce protrusion formation compared to untreated or M(IL-4/IL-10) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, just as M(IL-4/IL-10) BMDMs, we again detected no difference in protrusion frequency for either M(IL-4) or M(IL-10) BMDM relative to untreated controls. Recent evidence suggests that tuberculosis infection triggers an increase in M(IL-10) macrophage TNT formation, but direct stimulation of BMDMs with IL-10 does not seem to recapitulate this phenotype32.

We previously reported that co-culture of IC-21 macrophages with murine cystinotic fibroblasts appeared to increase the formation of TNTs7. We replicated these experiments using our new automated imaging system and observed an increase in membrane protrusion formation in IC-21 macrophages co-cultured with diseased murine Ctns−/− fibroblasts compared to wildtype fibroblasts (P = 0.007) (Fig. 1i). Proinflammatory stimulation of these co-cultures yielded a reduction in macrophage-derived protrusion formation with no obvious morphological changes in fibroblasts (Fig. 1j), confirming our previous data (Fig. 1h). Taken together, these data indicate proinflammatory M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophages generate fewer membrane protrusions than the immunomodulatory M(IL-4/IL-10) cells, and that diseased cystinotic cells enhanced protrusion formation in macrophages upon co-culture.

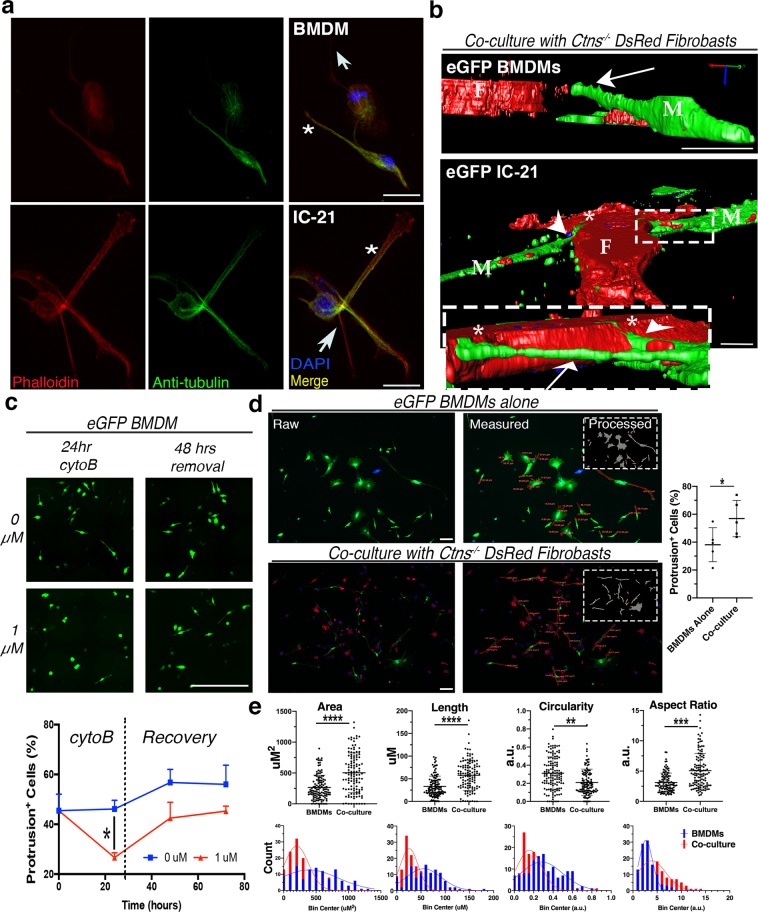

Macrophage-derived membrane protrusions resemble tunneling nanotubes

As no TNT-specific markers have been identified, we investigated the identity of macrophage-derived membrane protrusions based primarily on their morphology; TNTs are long, highly dynamic actin-rich tubes extending out from the plasma membrane without contacting the underlying substratum33,34. Cytoskeletal immunostaining of macrophage co-cultures revealed that all protrusions were actin-rich, while some also contained a tubulin core (Fig. 2a), a unique feature of thicker TNTs generated by macrophages mediating organelle transfer26. Protrusions were visualized in three dimensions via high-resolution imaging of Z-stacks and generation of 3D-reconstructions using ImagePro (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Both BMDMs and IC21 macrophages were found to have eGFP-positive protrusions extending above the substratum. Termini of the eGFP protrusions were observed directly adjacent to DsRed fibroblast cell bodies potentially indicating membrane fusion and facilitation of TNT stabilization through intercellular membrane connections. In addition, we treated BMDMs co-cultured with Ctns−/− fibroblasts with cytochalasin B (cytoB), an actin destabilizing agent reported to prevent TNT formation and to inhibit organelle trafficking35,36. Treatment with cytoB for 24 hours eliminated membrane protrusions from BMDMs with the extensions being restored several days following removal of cytoB (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Some macrophage protrusions resemble TNT structure, behavior, and morphology. (a) Confocal micrographs of BMDMs and IC-21 cells after immunostaining for cytoskeletal components - actin (red) and tubulin (green). Thinner (arrows) and thicker (stars) protrusions indicated in both cell types. Scale bars: 10 µM. (b) 3D Z-stack reconstructions of eGFP+ BMDM or IC-21 cells (labeled M) co-cultured with Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts (labeled F). Boxed insert highlights protrusions extending above dish surface (arrows) and resting along the substratum (arrowhead). See Supplementary Videos 1 and 2. Scale bars: 10 µM. (c) Representative stitched micrographs depicting eGFP+ BMDMs following treatment and removal of cytochalsin B (cytoB) compared to untreated controls. XY graph shows percentage of protrusion-positive cells in each condition over time (n = 3 regions per treatment). Scale bar: 500 µM. (d) Representative raw confocal micrographs and measured images for eGFP BMDMs alone and in co-culture with Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts. Raw images were first processed for automated protrusion detection (insert) and the box-and-whisker plot (right) displays percentile quantification of protrusion-positive cells for BMDMs alone and in co-culture. Protrusion detection software rarely captures complete shape, so results were used as a guide in order to blindly manually separate protrusions from cell bodies by cutting along the estimation of normal membrane curvature. ImagePro was then used to measure protrusions; area measurements shown on top image and length on bottom. Scale bar: 100 µM. (e) Box-and-whisker plot (top) and frequency histogram (bottom) depicting area, length, circularity and aspect ratio protrusion measurements for BMDMs alone vs. in co-culture. Circularity is calculated as the ratio of the object compared to a circle with diameter equal to object’s maximum Feret diameter, and represented on a scale from 0–1.0, with 1.0 being a perfect circle. Aspect ratio is the ratio of the major and minor axis of an eclipse equivalent to the object, with a higher value meaning a more elongated object. Outliers identified and excluded by ROUT test. Curves fit to histograms by Gaussean linear regression. P values determined by one-way ANOVA or student’s t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

In order to further characterize protrusions, we analyzed the shape and size of the automatically detected regions. We seeded and imaged equal numbers of eGFP BMDMs either alone or in co-culture with DsRed Ctns−/− fibroblasts. We first used our image analysis workflow to determine that co-cultures had a higher percentage of cells with protrusions than BMDMs alone (P = 0.046) (Fig. 2d). Using the automatically detected regions as guides, we blindly separated complete protrusions from the cell body, then used ImagePro to measure the resultant regions. From both conditions combined, we measured 242 individual protrusions and found that the mean protrusion area was 380.5 ± 145.4 µm2 and mean length was 45.00 ± 15.41 µm. As TNTs are extremely diverse, there is considerable variation on what “standard” dimensions between cell types37. That said, most authors report an average TNT length between 17.7 µm (Jurkat T cells) and 44 µm (ARPE-19 retinal pigment epithelial cells), while the longest protrusions can reach up to 120 µm, confirming our measurements are compatible with TNTs34,38. Unexpectedly, we also determined that protrusions generated from co-cultured macrophages were larger, longer and more elongated, meaning that they were less circular and had a larger ratio of the major to minor axis (Fig. 2e). These data not only confirm that a sizable fraction of protrusions appear to be of appropriate size to be considered TNTs but also highlights how the presence of diseased cystinotic cells affects protrusion morphology, as well as frequency. This is particularly interesting considering that previous work has shown that thicker macrophage TNTs preferentially transport organelles26.

Finally, we analyzed expression of several genes involved in TNT formation following macrophage polarization to assess any differential expression of TNT-associated genes (Supplementary Fig. S4). In M(LPS/IFNγ) BMDMs, we observe increased mRNA expression of the MHC class II protein leukocyte specific transcript 1 (Lst1). In contrast, M(LPS/IFNγ) BMDMs displayed decreased expression of the Rho-family GTPase cell division control protein 42 homolog (Cdc42). We did not detect any changes in other TNT-linked genes such as M-Sec, a component of the exocyst complex that directly promotes TNT formation nor did we detect any changes in protein expression (data not shown)39. Such changes in TNT marker expression after polarization are intriguing but thorough study of protein activity and localization would be required to uncover any mechanistic links between polarization and TNT formation. As such, in terms of protrusion characterization, a focus on structure, behavior and morphology is the more reliable method to indicate that a good fraction of the macrophage-derived protrusions automatically observed in our co-culture conditions represent bona fide TNTs.

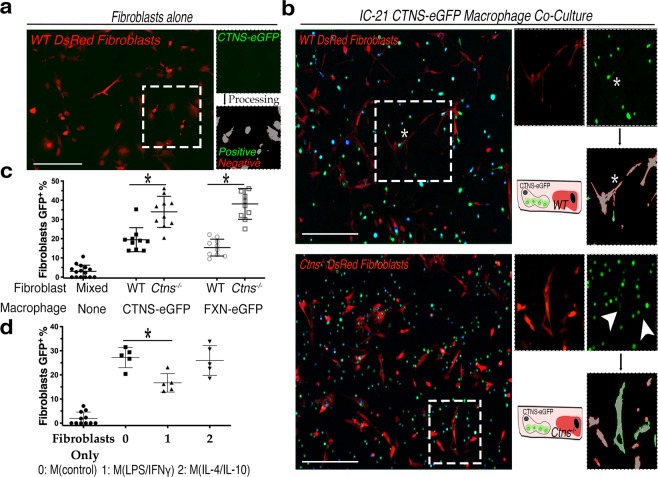

Co-culture of macrophages with cystinotic cells increased not only lysosomal but mitochondrial intercellular transfer as well

To investigate the potential impact of macrophage polarization on TNT-mediated intercellular organelle trafficking, Ctns−/− and WT DsRed+ fibroblasts were co-cultured with IC-21 macrophages stably transduced with the fusion proteins cystinosin-eGFP or frataxin-eGFP, a mitochondrial iron chelator defective in Friedreich’s ataxia40. In vitro live imaging previously revealed transfer of cystinosin-eGFP-bearing lysosomes or frataxin-eGFP-bearing mitochondria from macrophages to diseased murine Ctns−/− or Fxn−/− fibroblasts, respectively7,8. High-magnification 3D-reconstructions confirmed the presence of eGFP-positive organelles within the cytoplasm of DsRed+ fibroblasts, as demonstrated by 3D renderings and orthogonal projections (Supplementary Fig. S5a,b, Supplementary Videos 3 and 4). Lysosomal transfer was confirmed to occur through TNT-like structures (Supplementary Fig. S5c, Video 5).

We quantified the efficiency of lysosomal and mitochondrial transfer from the macrophages to the fibroblasts using another image analysis algorithm similar to the one we developed for TNT quantification, which measures the frequency of eGFP puncta (“donor”) within a region of interest (ROI) defined by DsRed+ “recipient” cell (Supplementary Fig. S6). Co-cultures of 75,000 cystinosin-eGFP or frataxin-eGFP-expressing IC-21 macrophages and 50,000 DsRed+ WT or Ctns−/− fibroblasts were grown for three days and then fixed; fibroblasts cultured alone were used as controls (Fig. 3a). Fluorescent imaging revealed significantly higher numbers of both cystinosin-eGFP lysosomes (P = 0.042) and frataxin-eGFP mitochondria (P = 0.019) in Ctns−/− fibroblasts compared to WT fibroblasts (Fig. 3b,c, Supplementary Fig. S6c). Further, we treated macrophages for co-culture experiments to determine if either macrophage subtype impacts the efficacy of intercellular trafficking. We observed a significantly decreased presence of cystinosin-eGFP-positive lysosomes within fibroblasts co-cultured with M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophages (P = 0.045) (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Intercellular trafficking of cystinosin-eGFP lysosomes and frataxin-eGFP mitochondria is increased to diseased Ctns−/− fibroblasts and diminished following proinflammatory polarization of co-cultured macrophages. (a) Representative stitched fluorescent micrograph of essential co-culture background control with only recipient DsRed+ fibroblasts. Boxed insert depicts automated image processing showing donor-positive (green) and donor-negative cells (red). See Supplementary Fig. S3 for automation methodology. (b) Representative fluorescent images of IC-21 cystinosin-eGFP co-cultures with either WT or Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts. Zoomed inserts highlight automated transfer quantification. Arrowheads indicate eGFP signal within DsRed+ fibroblasts. Stars indicate excluded signal due to cellular overlap. (c) Percentile quantitation of cystinosin- or frataxin-eGFP+ fibroblasts via automated image analysis. Each data point represents percent of donor-positive recipient cells in one stitched image (n = 3). All co-culture conditions have significantly more donor eGFP signal than background control with only fibroblasts (P < 0.05). (d) Frequency of cystinosin-eGFP trafficking in macrophage and fibroblast co-cultures following polarization with comparison to fibroblasts alone control. Histogram showing percentage of fibroblasts automatically determined positive for eGFP signal (n = 5). All scale bars are 500 µM. All graphs shown as mean ± SD. P values determined by one-way ANOVA or student’s t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

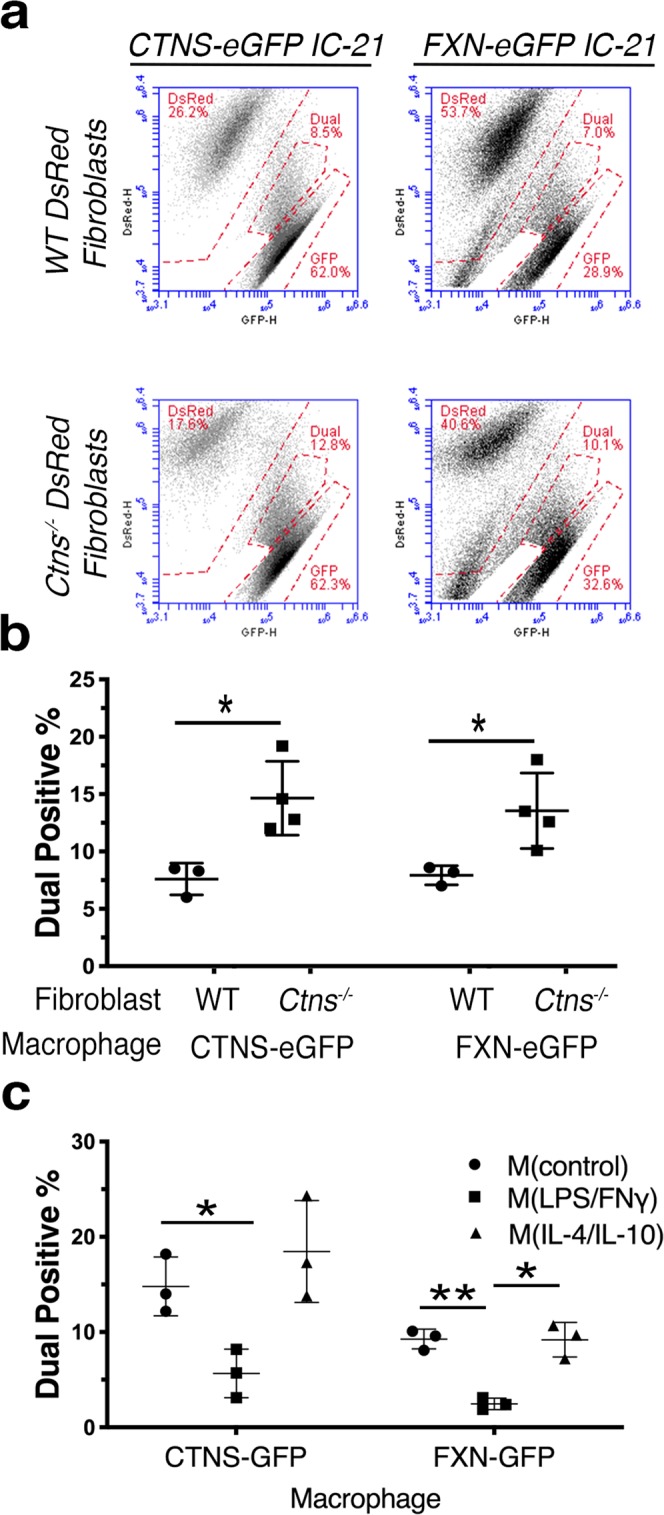

To corroborate our findings using another robust assay, we performed flow cytometry on co-cultures to analyze dual eGFP- and DsRed-positive cells; both cell types cultured alone were used as gating controls (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S7a). Consistent with our fluorescent imaging results, a significant increase of approximately 70–90% of the dual-positive population was observed in co-cultures of Ctns−/− fibroblasts with both cystinosin-eGFP (P = 0.0168) or frataxin-eGFP (P = 0.0371) macrophages as compared to WT fibroblast co-cultures (Fig. 4b). Another control of eGFP+ and DsRed+ cells mixed immediately prior to sorting did not yield dual-positive cells, indicating that prolonged co-culture is necessary to facilitate cellular interaction resulting in the generation of an eGFP+DsRed+ population (Supplementary Fig. S7b). Furthermore, proinflammatory macrophage polarization also dramatically decreased the transfer of cystinosin-eGFP and frataxin-eGFP (Fig. 4c). Altogether, these data show that diseased cells enhance transfer of lysosomes and mitochondria from macrophages to the fibroblasts, while proinflammatory polarization inhibits this process.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry confirms that intercellular trafficking is increased to diseased Ctns−/− fibroblasts and suppressed by proinflammatory polarization. (a) Representative FACS plots of DsRed (y-axis) and eGFP (x-axis) for 50,000 cells following co-culture of either cystinosin- or frataxin-eGFP and WT or Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts. Signal between eGFP and DsRed gates classified as a “dual-positive” eGFP+DsRed+ population. See Supplementary Fig. S4 for sorting and gating strategy. (b) Percentage quantification of eGFP+DsRed+ dual-positive cells in cystinosin- or frataxin-eGFP macrophage co-cultures with WT or Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts. Replicates consisted of co-cultures with fibroblasts derived from multiple mice (n = 4). (c) Quantification of dual-positive cell frequency after polarization treatment of co-cultures with cystinosin- or frataxin-eGFP and Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts (n = 3). All graphs shown as mean ± SD. P values determined by one-way ANOVA or student’s t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

HSPC-derived macrophages within the kidney of transplanted Ctns−/− mice appear to preferentially express M(LPS/IFNγ) markers

As in vitro polarization indicates that proinflammatory M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophages have impaired TNT formation and organelle transfer, we assessed the in vivo macrophage phenotype following HSPC transplantation in Ctns−/− mice. We transplanted WT eGFP HSPCs into Ctns−/− recipient mice via tail vein injection as previously described14 and analyzed macrophage polarization markers by performing immunostaining on kidney sections (Supplementary Fig. S8). We observed robust colocalization between the eGFP+ HSPC progeny and the pan-macrophage marker CD68 (Supplementary Fig S8a). Unexpectedly, more abundant co-localization was detected between the stem cell progeny and markers for M(LPS/IFNγ) such as CD16/32 or MHCII, than with anti-inflammatory markers ARG1, CD206 or CD163 (Supplementary Fig. S8b). Antibodies were tested on other tissues such as tumors to ascertain positive immunoreactivity (Supplementary Fig. S8c). These data suggest that in vivo proinflammatory macrophages are responsible for tissue preservation after WT HSPC transplantation in cystinosis.

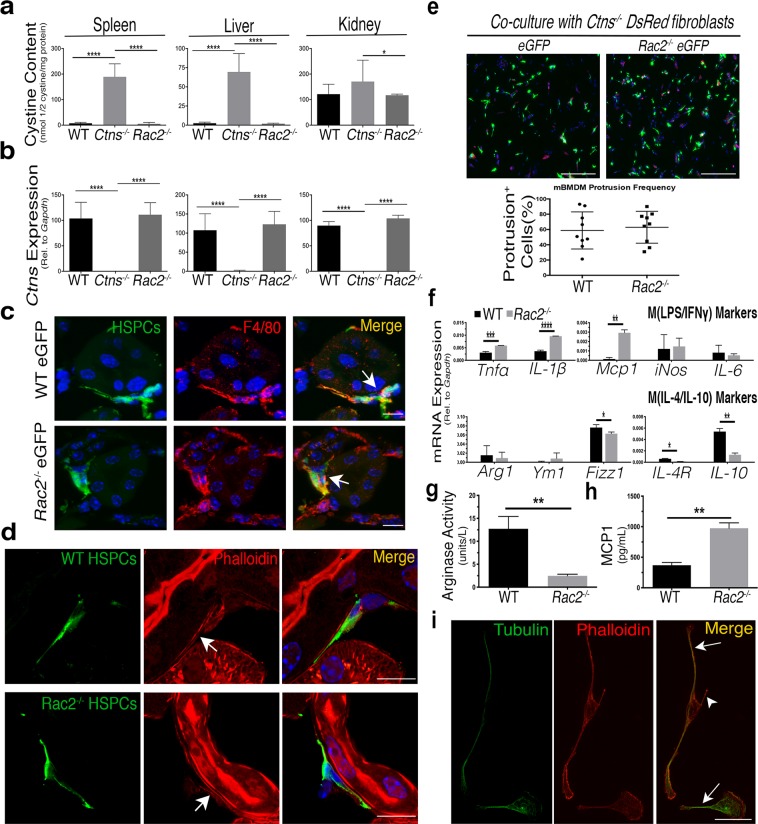

Disruption of anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization with Rac2−/− HSPCs has no effect on HSPC transplantation efficacy or TNT formation

To determine if proinflammatory macrophages are responsible for tissue preservation in cystinosis following HSPC transplantation, we genetically perturbed macrophage polarization to assess if deficiencies prevented rescue of the cystinosis phenotype following HSPC transplantation. The Rac2−/− mouse model, disrupting the hematopoietic-specific Rho family GTPase Rac2, was chosen due to its functions in actin cytoskeletal reorganization and macrophage polarization41,42. Since RAC2 was shown to drive M(IL-4/IL-10) macrophage differentiation, the proinflammatory M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophage population was enriched in knockout Rac2−/− mice43–45. A very similar family member, RAC1, also has a role in the biogenesis of macrophage protrusions including invadopodia, lamellipodia and TNTs42,46.

To test if Rac2 elimination has any effect on HSPC transplantation efficacy, HSPCs isolated from Rac2−/− eGFP-transgenic mice were transplanted into 2-month-old Ctns−/− recipient mice. Ctns−/− mice transplanted with WT eGFP+ or Ctns−/− eGFP+ HSPCs proven effective or ineffective at prevention of cystinosis, respectively, were used as controls14. HSPCs engraftment was measured by quantifying eGFP+ peripheral blood cells, which did not significantly differ between the three transplanted groups (average for WT −71.5%, Ctns−/− −75.6% and Rac2−/− −65.9%). Mice were sacrificed six months post-transplantation, and samples were collected for biochemical and phenotypic characterization. Assessment of tissue cystine content in WT HSPC recipients resulted in a dramatic reduction in cystine load in the liver, spleen, and kidneys relative to Ctns−/− HSPC-transplanted animals, as expected (Fig. 5a). Surprisingly, transplanted Rac2−/− HSPCs resulted in a decrease of cystine content to the same magnitude as WT HSPC controls. In addition, rescue of Ctns expression in tissues was similar in WT and Rac2−/− HSPC-transplanted Ctns−/− mice (Fig. 5b). Taken together, these data indicate that Rac2−/− HSPC transplantation is fully capable of restoring functional cystinosin to diseased tissue.

Figure 5.

Enrichment of proinflammatory macrophages in vivo by transplantation of Rac2−/− HSPCs has no effect on efficacy in Ctns−/− mice or on BMDM TNT formation in vitro. (a) Histograms representing cystine content in spleens, livers and female kidneys as measured by mass spectrometry in Ctns−/− mice transplanted with WT HSPCs (n = 5), Ctns−/− HSPCs (n = 4), and Rac2−/− HSPCs (n = 4). Only female kidneys are shown, as previous observations indicate that kidneys need to be analyzed by sex16, and only 2 males were in the smallest recipient group. (b) mRNA quantitation of murine Ctns expression of transplanted Ctns−/− mice in spleen, liver and kidney. Histograms represent changes in Ctns expression relative to housekeeping control Gapdh. (c) Representative confocal micrograph of kidney sections of Ctns−/− mice transplanted with either WT or Rac2−/− HSPCs (green), probed with the macrophage marker F4/80 (red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate colocalization between eGFP HSPC progeny and F4/80 expression. (d) Confocal micrograph depicting kidney sections of a Ctns−/− mouse transplanted with WT (top) or Rac2−/− (bottom) eGFP HSPCs reveals thin eGFP TNT-like protrusions extending away from the cell body. Frozen sections were stained with anti-GFP to enhance visibility of HSPC progeny, and then probed with rhodamine phallodin to highlight actin within TNT-like structures (arrows). Scale bars: 10 µM. (e) BMDMs isolated from WT or Rac2−/− bone marrow were co-cultured with Ctns−/− DsRed+ fibroblasts and assesed for frequency of protrusions using automated analysis software (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Histogram displays quantification of percentage of BMDMs positive for protrusions (n = 3). Scale bar: 500 µM. (f) Bar graph displays mRNA expression of each individual pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization gene relative to housekeeping control Gapdh in WT or Rac2−/− BMDMs (n = 3). (g) Bar graph shows measurement of proinflammatory MCP1 cytokine secretion in conditioned media derived from WT or Rac2−/− BMDMs assessed using ELISA (n = 3). (h) Bar graph represents colorimetric measurements of M(IL-4/IL-10) marker ARG1 enzymatic activity in WT or Rac2−/− BMDMs normalized by comparison to blank with a standard curve (n = 3). (i) Confocal micrograph of Rac2−/− BMDM cytoskeletal immunostaining of tubulin (green) and actin (red) reveals some Rac2−/− BMDM protrusions only have actin (arrowhead) with others also containing tubulin (arrows). All scale bars are 10 µM except otherwise noted. All graphs shown as mean ± SD. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA or students t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

We then analyzed kidney sections by immunofluorescence for immune cell infiltration and observed co-localization between Rac2−/− eGFP HSPC progeny and macrophage markers such as F4/80 or CD68 (Fig. 5c), indicating that typical macrophage differentiation remained unaltered. We also detected eGFP TNT-like protrusions within kidneys of both Rac2−/− and WT HSPC recipients that stained positive for actin, another hallmark of TNTs (Fig. 5d). These data confirm that knockout HSPC-derived cells retain the ability to form TNT-like protrusions in vivo.

Finally, we investigated the protrusive behavior and polarization phenotype of BMDMs isolated from Rac2−/− eGFP mice in vitro. We quantified co-cultures of freshly isolated WT eGFP+ and Rac2−/− eGFP+ BMDMs with Ctns−/− fibroblasts using our protrusion detection imaging algorithm (Supplementary Fig. S1) and observed no significant differences in protrusion frequency between WT- and Rac2−/−- BMDMs (P = 0.0472; Fig. 5e). We then analyzed polarization markers and confirmed that in contrast with WT BMDMs, Rac2−/− BMDMs skew towards M(LPS/IFNγ) without any extrinsic stimulation (Fig. 5f–h). However, we note that the magnitude of change in mRNA expression of genes was overall either less dramatic (Tnfα, Il-10 or Fizz1) than the M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophages treatment in vitro (Fig. 1a) or were not significantly different between genotypes (iNos, Arg1 or Il-6) (Fig. 5f). Even so, a robust increase in MCP1 secretion and significantly decreased ARG1 enzymatic activity compared to WT BMDMs further confirmed the proinflammatory phenotype of the Rac2−/− macrophages (Fig. 5g,h). However, Rac2−/− eGFP BMDMs still formed tubes resembling TNTs consisting of actin and tubulin cytoskeletons (Fig. 5i) found lying above the substratum surface (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that while the polarization phenotype of Rac2−/− eGFP+ BMDMs is skewed towards a M(LPS/IFNγ) phenotype, both formation of TNT-like protrusions and Rac2−/− HSPCs transplantation efficacy remain unaffected.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the phenotype of the HSPC-derived macrophages responsible for intercellular trafficking through TNTs. Several decades of research into macrophage subpopulations has elucidated differences in cytokine production, glucose metabolism, secondary messengers, stimulatory conditions, cellular morphology and numerous other factors which collectively lead to differences in macrophage biological activity, potentially including TNT-mediated trafficking27,28. Using established assays in conjunction with novel imaging workflows, we observed a reduction in TNT formation and organelle transfer following LPS/IFNγ polarization, suggesting optimal TNT trafficking is impaired with increased proinflammatory stimulation. Unlike other imaging analysis platforms, our protrusion detection methodology requires no antibody staining or fixation and can function at relatively low magnification (40x), enabling large numbers of cells to be quickly and automatically analyzed without bias47,48. Development of these tools not only increased our understanding of the morphological dynamics of macrophage polarization but also highlighted the potential for further study of cellular protrusion dynamics. This ImagePro Premier workflow could potentially allow quantitative analysis of other fluorescently-labeled cellular extensions such as filopodia, neuronal axons, or invadopodia in cancer.

Following HSPC transplantation in vivo, tissue-integrated macrophages appeared to adopt a predominantly proinflammatory phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S8). In addition, HSPCs isolated from the Rac2−/− mouse model were enriched for a M(LPS/IFNγ) macrophage population but appeared to be as efficient in rescuing cystine build-up in the Ctns−/− mice as WT HSPCs. Our findings correlate with a recent study that demonstrated increased recruitment of proinflammatory immune cells in cystinosis, further highlighting the crucial role that inflammation plays in this disorder49. In addition, the dissonance between our in vitro and in vivo results reflects mounting evidence that the in vitro paradigm of macrophage activity can be a potentially misleading oversimplification25. Further studies applying similar methodology to more complex in vitro models such as 3D culturing or iPSC-derived organoids or spheroids may help to bridge the gap between findings from cell culture and mouse models. That said, in vitro polarization can easily push cells beyond physiological levels of polarization. For example, the mRNA expression of important inflammatory mediators, including the master cytokine regulator TNFα, increased in M(LPS/IFNγ) IC-21 macrophages by over an order of magnitude; however, the magnitude of increase between Rac2−/− and WT BMDMs was far more modest. In terms of TNT-like protrusion formation, the reduced disruption of polarization induced by lack of RAC2 might be mitigated by redundant pathways or signaling. Alternatively, these results could show that RAC2 itself has no role in TNT formation. In contrast, siRNA-mediated knockdown of RAC1 results in a reduction of TNTs50. Although the two proteins are quite similar (92%), Miskolci et al. report substantial differences in their subcellular localization – upon stimulation, RAC1 is primarily localized to the periphery, while RAC2 was distributed throughout the cell51,52. Altogether, these data reveal that induction and function of TNT-like protrusions can be achieved by macrophages across the physiological spectrum of polarization, but is impaired when exogenous stimulation pushes cells to an extreme physiological state.

Like all cellular protrusions, TNTs require extensive modification and reorganization of the cytoskeleton to distort the plasma membrane and generate the protrusive force necessary to reshape the cell, elongate, and dynamically maintain the protrusion once formed1. Evidence also strongly implicates macrophage polarization in differentially modulating cytoskeletal dynamics and reorganization53,54. These shared pathways suggest polarization-induced alterations in expression and/or activity of TNT-regulator proteins could be responsible for the reduction in TNT-like protrusion formation following proinflammatory stimulation. We observed a reduction in M(LPS/IFNγ) BMDM mRNA expression of the known TNT inducer Lst1 which acts as a scaffold to recruit many proteins including filamin and the small GTPase RalA to the plasma membrane in order to generate and maintain TNTs55 (Supplementary Fig. S4). We also observed that proinflammatory BMDMs have decreased mRNA expression of Cdc42, a Rho-family GTPase involved in macrophage polarization which binds N-WASP to control actin branching through Arp2/342,56. In macrophages along with Jurkat and HeLa cells, inhibition of Cdc42 reduces TNT formation and intercellular trafficking39,50,57. Interestingly, in neurons Cdc42 actually negatively regulates TNTs and trafficking while promoting filopodial formation51. While one can speculate that the reduction of M(LPS/IFNγ) protrusion formation could be due to the increase of Lst1 disrupting normal formation of membrane focal points and/or because of the decrease of Cdc42 actin branching activity, drawing such mechanistic conclusions requires far more evidence than mRNA marker expression. That said, even though a direct connection between these expression changes and TNTs remain unclear, our data does support the central role of actin regulating Rho-family GTPases in TNT formation and provides further evidence of their involvement in macrophage polarization.

A major functional consequence of proinflammatory macrophage polarization was also a clear reduction in intercellular trafficking following induction of this phenotype (Fig. 3). Macrophages specifically are known to frequently form TNTs that are “thicker” and contain a tubulin core in addition to actin, which are known to be responsible for organelle trafficking7,26. Correspondingly, we observed an increase in protrusion frequency, size, length and elongated shape when BMDMs were cultured with cystinotic cells compared to macrophages alone (Fig. 2d,e). This observation combined with the shared reduction of trafficking and TNT-like protrusion formation following in vitro LPS/IFNγ polarization strongly supports the idea that TNTs form a major artery of intercellular delivery of lysosomes and mitochondria. Interestingly, not only were more cystinosin-eGFP-bearing lysosomes delivered to the diseased cells, which lack the lysosomal transmembrane protein cystinosin, but an increase in transfer of frataxin-eGFP-bearing mitochondria was also observed to cystinotic cells. Two hypotheses could explain these findings: (i) TNTs facilitate widespread delivery of cellular organelles to diseased cells so the fact that there are more thick TNTs inevitably leads to more trafficking of all cargos. No known TNT “gating” mechanisms have been identified to disprove this hypothesis, although overall protrusion structure has been shown to affect the types of molecular cargos transferred26; (ii) Cystinosis also causes mitochondrial dysfunction characterized by dysregulation of the cyclic AMP cycle and impaired autophagy58,59. Therefore, it is also possible that whatever unknown media-soluble factor(s) causing increased TNT-like protrusion formation and thicker morphology also stimulates transfer of mitochondria as well as lysosomes. Whatever the cause may ultimately be, the finding that diseased cells increased macrophage-derived thick TNT formation and intercellular trafficking activity represents exciting new possibilities for the study of TNTs. A major thread of research from numerous groups has focused on how TNTs are involved in the transfer of harmful pathogenic molecules – ranging from HIV infection in T cells to cancer cell invasion to spreading misfolded tau protein aggregates17,34,60. Thus, our findings that diseased cystinotic cells cause macrophages to increase TNT-mediated trafficking highlights the idea of TNTs as delivery system for regenerative medicine as opposed to mediating the spread of deleterious agents.

In this study, we investigated the phenotype of macrophages responsible for the widespread dissemination of molecular cargo via TNTs both in vitro and in vivo. We developed novel imaging tools allowing for automatic and unbiased quantification of cellular protrusions as well as intercellular trafficking efficacy in order to investigate these behaviors in the context of polarized macrophages. Given the apparent widespread and versatile nature of macrophage TNT transport, it is likely that many molecular products beyond functional lysosomes or mitochondrial proteins are transferred via TNTs; cargos that may not be readily secreted and thus be more difficult to deliver widely. Thus, understanding the mechanisms and cellular type that are responsible for TNT-mediated delivery will enhance the efficacy of numerous potential ex vivo therapeutic approaches targeting a wide variety of loss-of-function organelle disorders.

Methods

Mice and ethics statement

C57BL/6 Rac2−/− mice were provided by Dr. Durden (Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego) and C57BL/6 Ctns−/− mice were provided by Dr. Antignac (Inserm U983, Paris, France). Enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP; C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/j) and DsRed (B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-DsRed*MST)1Nagy/J) transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Ctns−/− mice were cross-bred to both DsRed and GFP to produce Ctns−/− strains constitutively expressing either DsRed or GFP reporter genes as previously described14,16. All strains and mouse procedures were approved by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol ID S12288).

Macrophage and fibroblast isolation and culture

BMDMs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice according to standard protocols as described previously61. Briefly, mice were sacrificed using isoflurane, femurs and tibias were removed, and bone marrow was flushed using PBS with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in complete RPMI-1640 media (10% FBS, 2% penicillin/streptomycin) supplemented with 20% mCSF-containing L929-conditioned medium for seven days on tissue-culture (TC) treated plastic, with a media change at day 3. BMDMs were grown for no more than three passages and subcultured by scraping. For in vitro polarization experiments, BMDMs or IC-21 were cultured for at least 48 hours in complete media with either 100 ng/mL LPS and 50 ng/mL IFNγ or 10 ng/mL IL-4 and IL-10 (BioLegend) for M(LPS/IFNγ) and M(IL-4/IL-10) polarization, respectively. Primary fibroblasts were isolated from neonatal mouse skin biopsies by allowing them to grow out of small skin pieces (~0.5 cm2) attached to the culture dishes for several days prior to skin removal and subculture in complete DMEM media (10% FBS, 2% penicillin/streptomycin).

Co-culture growth and imaging

75,000 macrophages and 50,000 fibroblasts were cultured together in 6-well dishes under polarization conditions for two days. Cells were washed with warm PBS and fixed for 10 mins at 37 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Cells were washed in PBS again and imaged at 40X on the BZX-700 Fluorescent Microscope (Keyence). Five large image stitches (5 × 5) were generated per experimental condition, with acquisition settings held constant within experimental runs.

Imaging analysis: protrusion quantification

Stitched images were calibrated in ImagePro Premier (Media Cybernetics) for automated quantification of protrusion frequency. eGFP+ macrophages were size-selected by filtration of objects with an area 100 µm2 or larger and then masked to reduce noise artifacts (Supplementary Fig. S1a, Step I). Protrusions were isolated by repeatedly passing a morphological erosion filter (2 × 2 square, 7 passes) over the image which erased peripheral cellular signal, followed by applying a dilation that restored signal to the central cell body (Step II). Subtracting the processed image from the original mask resulted in selection of regions protruding from the main cell body, which can be filtered by a highly variable set of size parameters to yield either thin TNT-like structures or other thicker protrusions (Supplementary Fig. S1b) (filters for TNTs: 20 µm2 minimum area, 10 µm2 minimum longest axis, 0.6 maximum circularity, 1.9 box area minimum). Finally, the selected protrusion area was overlaid with the original image and cells were classified as either protrusion-positive or -negative based on signal intensity; overlap of protrusion and cell body yielded a positive result (Step III - IV). All segmentation, adjustment and filtration factors were trained and optimized blind to condition and applied automatically to batch images using ImagePro Premier macros.

Imaging analysis: transfer quantification

Stitched images were imported as above and split into “donor” and “recipient” (DsRed) channels. Donors included genetically-encoded, fluorescently-labeled organelles like cystinosin-eGFP lysosomes and frataxin-eGFP mitochondrial protein, as well as transient stains (for example, Wheat Germ Agglutin (WGA) labels of the plasma membrane). Recipient cell outline was selected (minimum area 100 µm2) and applied as a region of interest (ROI) to the donor channel. Any signal within this ROI was adjusted and selected, taking caution to use controls lacking any donor signal to establish fluorescent background (Supplementary Fig. S3b, top). Filtered donor signal was combined with original recipient outline and signal overlap was used again to classify recipients as donor-positive or -negative. Exclusion of any signal at the boundary of recipient cells, as well as size filtration of donor molecules (maximum area 25 µm2), helped reduce false-positive imaging artifacts.

Flow cytometry

Co-cultures were seeded as described previously, but onto non-tissue culture-treated plastics to enable trypsinization of macrophages. Co-cultures were washed in ice-cold PBS, trypsinized at room temperature (RT) and rapidly rinsed in cold media before centrifugation at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in cold PBS and vortexed, then run through the BD Accuri C6 cytometer (BD Biosciences). Debris was filtered by SSC/FSC gating with 50,000 cellular events collected. Macrophages and fibroblasts without any fluorescent tags were used to establish an exclusion region from final co-culture sort, while eGFP+, DsRed+ and dual-positive gates were drawn with each cell type seeded alone. For macrophage polarization markers, BMDMs were polarized as described, then scraped and resuspended in ice cold FACS buffer (1% FBS, 0.1% sodium azide in PBS). Cells were treated with Fc block (BD Biosciences) for 10 mins before incubation for 1 hr on ice in the dark with appropriate antibodies. Cells were washed three times in FACS buffer before immediately reading on the cytometer. Antibodies are as follows: F4/80 PE (Biolegend 565410), CD80 FITC (Biolegend 104706), CD126/IL6Rα APC (115811), CD206 PE (Biolegend 141795).

Quantitative PCR

To measure gene expression in BMDMs/IC-21 and explanted tissues, total RNA was extracted with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s recommendations. A total of 1 μg isolated RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green on a CFX96 thermocycler (Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: 95 °C (30 s), 40 cycles of 95 °C (5 s) and 60 °C (30 s), then 65 °C (5 s) and finally 95 °C (5 s). Reaction mixture consisted of 3 μL cDNA (5 ng/ul), 0.6 μL forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 1.8 μL H20 and 5 μL SYBR green. Samples were normalized to Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) and analyzed according to the delta/delta Ct method. All primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunoblotting

Total protein was harvested and resuspended in 1% SDS from cultures of 1 × 106 BMDMs and IC-21 using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) per manufacturers protocol and quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 10–20 μg of protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked in 5% Protein Blocking Reagent (Azure) for 1 hr at RT and then probed overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Antibodies included M(LPS/IFNγ) markers iNOS (abcam ab3523; 1:1,000) and MCP1(CST 2029S; 1:500), M(IL-4/IL-10) markers ARG1 (Santa Cruz sc-20150; 1:200), CD206 (abcam ab64693; 1:500), macrophage marker CD68 (abcam ab53444; 1:500) and loading control Gapdh (abcam ab8245; 1:1,000). The following day, blots were washed three times in Protein Wash Buffer (Azure) and probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody of the appropriate species at 1:2,500 for one hour at room temperature. Blots were then washed three times in Protein Wash Buffer and once with TBS, developed with Radiance Plus ECL Reagent (Azure), and imaged on the c600 Imager (Azure).

ELISA and arginase activity assays

Conditioned media for ELISA experiments were generated by culture of 200,000 IC-21 or BMDM in polarization media for two days and then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 mins to remove cell debris. MCP1 SimpleStep ELISA (abcam ab208979) was performed on 1:2,000 diluted media in duplicate per manufactures recommendation. Arginase enzymatic activity was quantitated using 1 × 106 polarized macrophages using a colorimetric assay according to manufactures protocol (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

Metabolically active cells were measured using the Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (Roche) by seeding 5,000 IC-21 or BMDMs in 100 μL per well in triplicate in two identical 96 well plates. After treatment, 10 μL of WST-1 was added to all cell and blank wells of one plate, while the other was changed back into normal macrophage media. Absorbance was measured at 260 nm, following one hour of incubation and a corresponding standard curve was generated with blank-subtracted values normalized to untreated controls. The other plate was processed identically several days later.

Cytochalasin B

Cytochalasin B (Sigma) was diluted from stock to form 1,000X solution in DMSO and seeded with 100,000 macrophages. Treated and control cells were imaged as above at 24 hours post-seeding, followed by a drug washout with fresh media. At 24- and 48-hour post-removal, cells were again imaged at the same locations.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips for high-resolution imaging. After growth, cells were rinsed in PBS and fixed in warm 4% PFA for 15 min at 37 °C. Cells were blocked in blocking buffer (1% BSA, 5% goat serum, 0.3% triton X-100) for 1 hour at RT, and probed with primary anti-tubulin antibody (abcam ab6160; 1:500) diluted in antibody buffer (1% BSA, 0.3% triton X-100) overnight at 4 °C. Following three washes of PBS, cells were incubated in secondary antibody and phalloidin (1:200) for 1 hour at RT. Cells were again rinsed, mounted on glass overnight in Prolong Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen), and imaged the following day.

HSPC isolation, transplantation, and cystine measurements

HSPCs were isolated and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice as previously described16. In brief, bone marrow cells were flushed from the tibia and femurs of 6 to 8-week old WT, Ctns−/− and Rac2−/− eGFP mice. HSPCs were isolated by immunomagnetic separation using magnetic beads conjugated to anti-ScaI antibody (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated HSPCs were directly transplanted via tail vein injection of 100 μL containing 1 × 106 HSPCs into Ctns−/− mice subjected to a lethal 7 Gy irradiation the previous day. Engraftment was assessed by percentage of eGFP+ cells in peripheral blood at 2- and 4-month post-transplantation. At six months post-transplantation, recipient mice were sacrificed and kidney, liver, and spleen samples were isolated and analyzed by qPCR and mass spectrometry for murine Ctns expression and overall cystine load as previously described15.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in Prism (GraphPad). Student’s t-test was performed for comparisons of two groups, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for comparisons of three or more conditions. Outliers were identified and excluded from larger protrusion measurement dataset by the ROUT method62. All graphs display mean ± standard deviation.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Donald Durden and Dr. Shweta Joshi for providing Rac2−/− KO mice and for their help in this study. The authors thank Peter Hevezi, Janell Smith, Riley Stack and other lab members for their contributions. This work was supported by the Cystinosis Research Foundation, the National Institute of Health (NIH) RO1-DK090058 and R01-NS108965, the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM, CLIN-09230) and the Friedreich’s ataxia Research Alliance (FARA). UCSD Neuroscience Microscopy Shared Facility was funded by the Grant P30-NS047101.

Author Contributions

S.G., S.N. and S.C. conceived experiments and analyzed results. S.G., S.N., M.K. and J.S. conducted the experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data sets and ImagePro macros will be shared upon request.

Competing Interests

Stephanie Cherqui is a cofounder, shareholder and a member of both the Scientific Board and Board of Directors of GenStem Therapeutics Inc. Stephanie Cherqui serves as a consultant for AVROBIO and receives compensation for these services. Stephanie Cherqui also serves as a member of the Scientific Review Board and Board of Trustees of the Cystinosis Research Foundation. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50971-x.

References

- 1.Ariazi J, et al. Tunneling Nanotubes and Gap Junctions-Their Role in Long-Range Intercellular Communication during Development, Health, and Disease Conditions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:333. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustom A, Saffrich R, Markovic I, Walther P, Gerdes HH. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science. 2004;303:1007–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1093133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Veruki ML, Bukoreshtliev NV, Hartveit E, Gerdes HH. Animal cells connected by nanotubes can be electrically coupled through interposed gap-junction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17194–17199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gousset K, Marzo L, Commere PH, Zurzolo C. Myo10 is a key regulator of TNT formation in neuronal cells. Journal of cell science. 2013;126:4424–4435. doi: 10.1242/jcs.129239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinnery HR, Pearlman E, McMenamin PG. Cutting edge: Membrane nanotubes in vivo: a feature of MHC class II+ cells in the mouse cornea. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:5779–5783. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurke S, et al. Tunneling nanotube (TNT)-like structures facilitate a constitutive, actomyosin-dependent exchange of endocytic organelles between normal rat kidney cells. Experimental cell research. 2008;314:3669–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naphade S, et al. Brief reports: Lysosomal cross-correction by hematopoietic stem cell-derived macrophages via tunneling nanotubes. Stem cells. 2015;33:301–309. doi: 10.1002/stem.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocca CJ, et al. Treatment of Inherited Eye Defects by Systemic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:7214–7223. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaide Chevronnay HP, et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cells Transplantation Can Normalize Thyroid Function in a Cystinosis Mouse Model. Endocrinology. 2016;157:1363–1371. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalatzis V, Cherqui S, Antignac C, Gasnier B. Cystinosin, the protein defective in cystinosis, is a H(+)-driven lysosomal cystine transporter. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:5940–5949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emma F, et al. Nephropathic cystinosis: an international consensus document. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(Suppl 4):iv87–94. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherqui S, et al. Intralysosomal cystine accumulation in mice lacking cystinosin, the protein defective in cystinosis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:7622–7632. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7622-7632.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medic G, van der Weijden M, Karabis A, Hemels M. A systematic literature review of cysteamine bitartrate in the treatment of nephropathic cystinosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:2065–2076. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1354288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syres K, et al. Successful treatment of the murine model of cystinosis using bone marrow cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:2542–2552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeagy BA, et al. Kidney preservation by bone marrow cell transplantation in hereditary nephropathy. Kidney international. 2011;79:1198–1206. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison F, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for the multisystemic lysosomal storage disorder cystinosis. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21:433–444. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eugenin EA, Gaskill PJ, Berman JW. Tunneling nanotubes (TNT) are induced by HIV-infection of macrophages: a potential mechanism for intercellular HIV trafficking. Cell Immunol. 2009;254:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osswald M, Solecki G, Wick W, Winkler F. A malignant cellular network in gliomas: potential clinical implications. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:479–485. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruzauskaite I, et al. Relevance of HCN2-expressing human mesenchymal stem cells for the generation of biological pacemakers. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:67. doi: 10.1186/s13287-016-0326-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabriel SS, et al. Bone marrow transplantation improves proximal tubule dysfunction in a mouse model of Dent disease. Kidney international. 2017;91:842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocca Celine J., Goodman Spencer M., Dulin Jennifer N., Haquang Joseph H., Gertsman Ilya, Blondelle Jordan, Smith Janell L. M., Heyser Charles J., Cherqui Stephanie. Transplantation of wild-type mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells ameliorates deficits in a mouse model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Science Translational Medicine. 2017;9(413):eaaj2347. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Journal of immunology. 2000;164:6166–6173. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ying, W., Cheruku, P. S., Bazer, F. W., Safe, S. H. & Zhou, B. Investigation of macrophage polarization using bone marrow derived macrophages. J Vis Exp, 10.3791/50323 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Murray PJ, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000prime reports. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onfelt B, et al. Structurally distinct membrane nanotubes between human macrophages support long-distance vesicular traffic or surfing of bacteria. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:8476–8483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McWhorter FY, Wang T, Nguyen P, Chung T, Liu WF. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17253–17258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308887110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang N, Liang H, Zen K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage m1-m2 polarization balance. Front Immunol. 2014;5:614. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatano Y, Shimizu T, Tomioka H. Unique macrophages different from M1/M2 macrophages inhibit T cell mitogenesis while upregulating Th17 polarization. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4146. doi: 10.1038/srep04146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van den Bossche J, et al. Pivotal Advance: Arginase-1-independent polyamine production stimulates the expression of IL-4-induced alternatively activated macrophage markers while inhibiting LPS-induced expression of inflammatory genes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2012;91:685–699. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0911453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raggi F, et al. Regulation of Human Macrophage M1-M2 Polarization Balance by Hypoxia and the Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells-1. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1097. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souriant S, et al. Tuberculosis Exacerbates HIV-1 Infection through IL-10/STAT3-Dependent Tunneling Nanotube Formation in Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2019;26:3586–3599 e3587. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sowinski S, Alakoskela JM, Jolly C, Davis DM. Optimized methods for imaging membrane nanotubes between T cells and trafficking of HIV-1. Methods. 2011;53:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abounit S, Zurzolo C. Wiring through tunneling nanotubes–from electrical signals to organelle transfer. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:1089–1098. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bukoreshtliev NV, et al. Selective block of tunneling nanotube (TNT) formation inhibits intercellular organelle transfer between PC12 cells. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1481–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Gerdes HH. Transfer of mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes rescues apoptotic PC12 cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1181–1191. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austefjord MW, Gerdes HH, Wang X. Tunneling nanotubes: Diversity in morphology and structure. Commun Integr Biol. 2014;7:e27934. doi: 10.4161/cib.27934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittig D, et al. Multi-level communication of human retinal pigment epithelial cells via tunneling nanotubes. PloS one. 2012;7:e33195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hase K, et al. M-Sec promotes membrane nanotube formation by interacting with Ral and the exocyst complex. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:1427–1432. doi: 10.1038/ncb1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busi MV, Gomez-Casati DF. Exploring frataxin function. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:56–63. doi: 10.1002/iub.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts AW, et al. Deficiency of the hematopoietic cell-specific Rho family GTPase Rac2 is characterized by abnormalities in neutrophil function and host defense. Immunity. 1999;10:183–196. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aflaki E, et al. Impaired Rho GTPase activation abrogates cell polarization and migration in macrophages with defective lipolysis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3933–3947. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0688-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joshi S, et al. Rac2 controls tumor growth, metastasis and M1-M2 macrophage differentiation in vivo. PloS one. 2014;9:e95893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joshi S, et al. Rac2 is required for alternative macrophage activation and bleomycin induced pulmonary fibrosis; a macrophage autonomous phenotype. PloS one. 2017;12:e0182851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Symons M. Rho family GTPases: the cytoskeleton and beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:178–181. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rostam HM, Reynolds PM, Alexander MR, Gadegaard N, Ghaemmaghami AM. Image based Machine Learning for identification of macrophage subsets. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3521. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03780-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alfonso-Garcia A, et al. Label-free identification of macrophage phenotype by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21:46005. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.21.4.046005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lobry Tatiana, Miller Roy, Nevo Nathalie, Rocca Celine J., Zhang Jinzhong, Catz Sergio D., Moore Fiona, Thomas Lucie, Pouly Daniel, Bailleux Anne, Guerrera Ida Chiara, Gubler Marie-Claire, Cheung Wai W., Mak Robert H., Montier Tristan, Antignac Corinne, Cherqui Stephanie. Interaction between galectin-3 and cystinosin uncovers a pathogenic role of inflammation in kidney involvement of cystinosis. Kidney International. 2019;96(2):350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanna SJ, et al. The Role of Rho-GTPases and actin polymerization during Macrophage Tunneling Nanotube Biogenesis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8547. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08950-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delage E, et al. Differential identity of Filopodia and Tunneling Nanotubes revealed by the opposite functions of actin regulatory complexes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39632. doi: 10.1038/srep39632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miskolci V, Wu B, Moshfegh Y, Cox D, Hodgson L. Optical Tools To Study the Isoform-Specific Roles of Small GTPases in Immune Cells. Journal of immunology. 2016;196:3479–3493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pergola C, et al. Modulation of actin dynamics as potential macrophage subtype-targeting anti-tumour strategy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41434. doi: 10.1038/srep41434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jonsson F, Gurniak CB, Fleischer B, Kirfel G, Witke W. Immunological responses and actin dynamics in macrophages are controlled by N-cofilin but are independent from ADF. PloS one. 2012;7:e36034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schiller C, et al. LST1 promotes the assembly of a molecular machinery responsible for tunneling nanotube formation. Journal of cell science. 2013;126:767–777. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Regulation of actin polymerization by Arp2/3 complex and WASp/Scar proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:32531–32534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arkwright PD, et al. Fas stimulation of T lymphocytes promotes rapid intercellular exchange of death signals via membrane nanotubes. Cell Res. 2010;20:72–88. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sansanwal P, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy promotes cellular injury in nephropathic cystinosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2010;21:272–283. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009040383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bellomo F, et al. Impact of atypical mitochondrial cyclic-AMP level in nephropathic cystinosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:3411–3422. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2800-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanna Samer J., McCoy-Simandle Kessler, Leung Edison, Genna Alessandro, Condeelis John, Cox Dianne. Tunneling nanotubes, a novel mode of tumor cell–macrophage communication in tumor cell invasion. Journal of Cell Science. 2019;132(3):jcs223321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.223321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, X., Goncalves, R. & Mosser, D. M. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc ImmunolChapter 14, Unit 14 11, 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Motulsky HJ, Brown RE. Detecting outliers when fitting data with nonlinear regression - a new method based on robust nonlinear regression and the false discovery rate. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data sets and ImagePro macros will be shared upon request.