Abstract

Climate change affects all seasons, but warming is more pronounced in winter than summer at mid- and high latitudes. Winter warming can have profound ecological effects, which are rarely compared to the effects of summer warming, and causal explanations are not well established. We compared mild aboveground infrared warming in winter to warming in summer in a semi-natural, cool-temperate grassland in Germany for four years. Aboveground plant biomass increased following winter warming (+18%) and was unaffected by summer warming. Winter warming affected the composition of the plant community more than summer warming, favoring productive species. Winter warming increased soil respiration more than summer warming. Prolonged growing seasons and changes in plant-community composition accounted for the increased aboveground biomass production. Winter warming stimulated ecological processes, despite causing frost damage to plant roots and microorganisms during an extremely cold period when warming reduced the thermal insulation provided by snow. Future warming beyond such intermittent frosts may therefore further increase the accelerating effects of winter warming on ecological processes.

Subject terms: Climate-change ecology, Climate-change ecology

Introduction

Winter warming is projected to outpace summer warming by 2 °C in central Europe by 2071–2100, with even larger differences farther north (RCP 8.51,2). A solid understanding of the relevant winter processes and their ecological importance is still lacking, because manipulation experiments simulating climate change commonly apply uniform warming only during the growing season3,4. Predicting the ecological effects of seasonally non-uniform warming is consequently highly uncertain5.

Summer warming can increase aboveground plant biomass production, but this effect is often limited by water, light, and nutrient availability3. Plants in areas characterized by seasonal frost are directly limited by temperature in winter6, and winter warming consequently increases the spring7 or annual8 aboveground plant biomass production in temperate grasslands, particularly if warming leads to the absence of soil frost9. Seasonal warming should further induce changes in community composition due to species-specific physiological adaptations to seasonal variation in climatic conditions10. Key ecosystem processes such as plant biomass production and decomposition are affected by plant-community composition11,12. Furthermore, the sensitivity of soil respiration to temperature is higher in winter and spring than summer and autumn13,14. Finally, the ecological sensitivity toward winter warming is probably linked to the trade-off between the length of the growing season and frost damage. Warming in late winter advances spring plant phenology15 and thereby lengthens the growing season and enhances aboveground biomass production. This earlier start of the growing season due to warming, however, can also lead to pre-mature de-hardening, with an increased risk of subsequent frost damage16. Snow cover plays a crucial role in ecosystem processes in colder climates17, but winter warming is decreasing snow cover and depth in cool and cold temperate ecosystems18,19. Snow, however, is an excellent insulator, and reduced snow cover and depth can lead to “colder soils in a warmer world”20 because of the reduced insulation of the soil during atmospheric frost. The effect of this insulation complicates predictions of soil biotic responses to winter warming. Soil warming generally increases soil biotic activity21, N mineralization and availability22, and soil respiration3 in temperate ecosystems. Reduced snow cover can thus decrease soil biotic activity despite warming23–25. Reduced snow cover and increased soil freezing may consequently offset any stimulating effect of warming, leading to no net effects on important ecosystem processes such as litter decomposition26,27. Winter warming can lengthen the growing season by later senescence in autumn and earlier green-up in spring but can also increase frost damage of plants and soil biota28.

Taken together, winter warming can lengthen the growing season1,15 but can also result in increased frost damage of plants and soil biota due to reduced frost hardening16 and due to reduced insulation by snow20,28. Thus, detailed observations of plant performance and soil biotic activity during winter warming are needed for a better mechanistic understanding of the season-specific effects of warming17. Here, we present results from a warming experiment over four consecutive years in which summer warming (April to September), winter warming (October to March), and ambient reference conditions were compared in a semi-natural temperate grassland. These permanent grasslands are used for hay production with 2–5 cuts per year or as pasture since medieval times and harbor substantial amounts of native species on 13% of the landscape in Europe29. We hypothesized that winter warming would increase annual aboveground biomass production and soil respiration stronger than summer warming and furthermore has a greater impact on plant species composition. In order to explain the observed net effects of winter warming (annual aboveground biomass production, plant community composition, soil respiration), plant performance (greenness, root growth, leaf C:N ratio) and soil biotic processes (microbial biomass, potential extracellular enzyme activity, N-availability, soil respiration) were quantified during winter.

Results

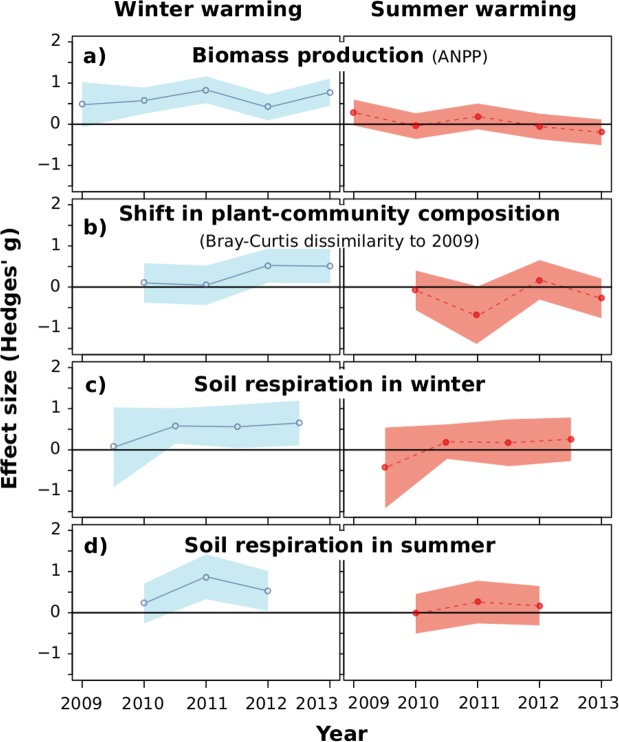

Aboveground infrared warming in winter led to 0.6 and 1.7 °C warming of air and soil, respectively, from October to March. Warming in summer increased air and soil temperature by 1.7 and 0.6 °C, respectively, from April to September (Supplementary Information Fig. 1) over four consecutive years. Winter warming had larger effects than summer warming on the ecological parameters measured. Aboveground net primary production (ANPP, i.e. the biomass produced over one year) was on average 18% higher and differed significantly from control in all four study years, with increasing effect sizes over time, in the winter-warming treatment compared to reference conditions (Fig. 1a). Summer warming did not significantly affect ANPP in any year. Annual soil respiration throughout the study period increased by 9.3% due to winter warming and by 5.9% due to summer warming. Winter warming increased soil respiration in both winter and summer, with effects being significant from the second warming campaign in both seasons (Fig. 1c,d), but summer warming increased soil respiration only in summer, again with significant effects from the second summer warming campaign onwards. Finally, winter warming affected plant-community composition more than summer warming over time with significant differences to control in the third and fourth study year while summer warming did not significantly affect plant-community composition (Fig. 1b). As indicated by an Indicator Species Analyses, this shift in community composition was in favor of tall and productive species in the winter warming treatment while no such clear trend was found in the summer warming treatment (Supplementary Information Table 1).

Figure 1.

Winter warming is ecologically more relevant than summer warming. (a) Aboveground net primary production (ANPP, sum of two destructive harvests of 0.2 m² y−1), (b) changes in plant-community composition per plot compared to its initial composition in 2009 expressed as Bray-Curtis distance (based on estimates of species-specific cover (1 m²) in June), and (c,d) soil respiration (mean of monthly measurements separated by winter (c) and summer (d) for the entire study period). The effect sizes as compared to reference conditions are displayed as Hedges’ g (n = 10) per sampling date and treatment and its 95% confidence intervals. A treatment is considered significant if the confidence band does not include zero (gray horizontal line). Note that the year 2009 displays pre-treatment conditions.

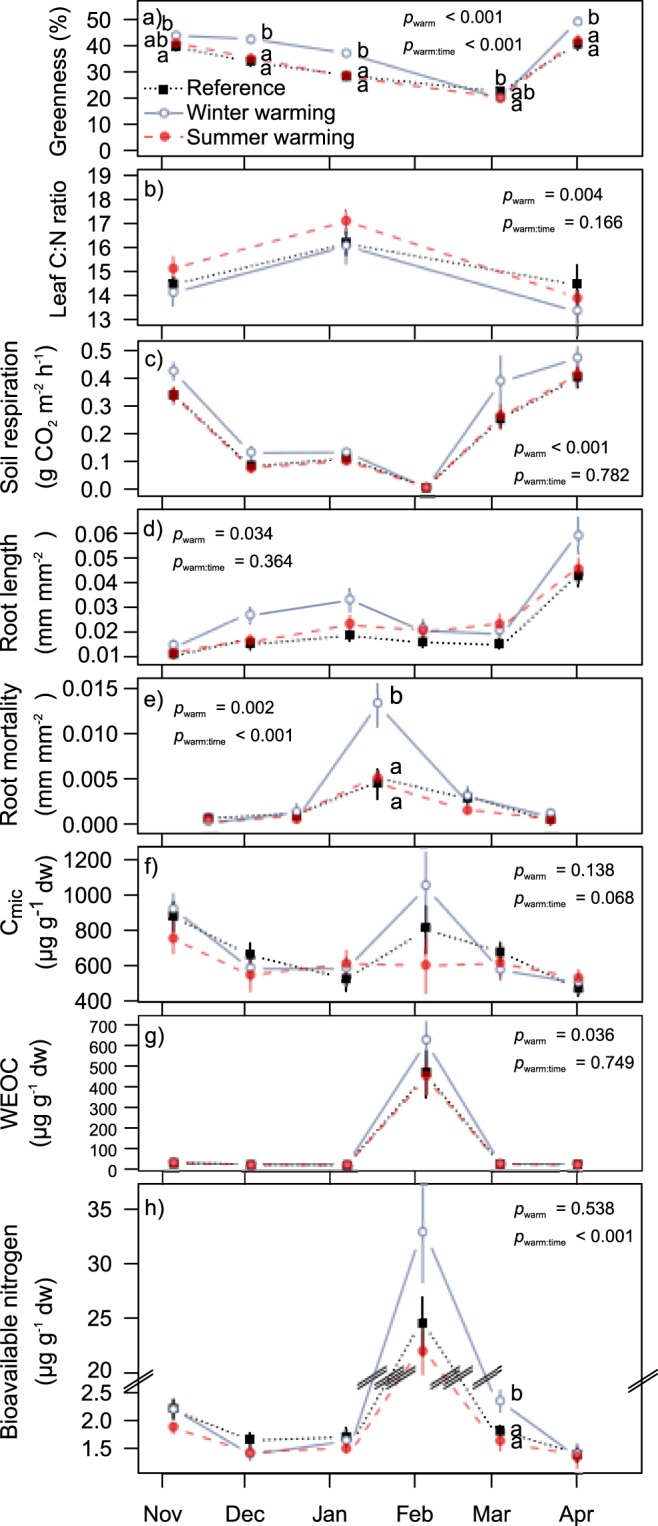

The increase in aboveground biomass production and soil respiration due to winter warming may have been due to the change in plant-community composition, but also to other winter ecological processes such as plant performance (greenness, root length and mortality, and leaf C:N ratio) and soil biotic processes (soil respiration, microbial biomass, N availability, and potential extracellular enzymatic activity) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Information Fig. 2). The intensive winter sampling campaign indicated that winter warming lengthened the growing season both in late autumn and in early spring, indicated by plant greenness, root length, and soil respiration (Fig. 2a–c). Lower leaf C:N ratios (Fig. 2d) further indicated active N uptake by plant roots late in autumn and early in spring, supporting the conclusion that winter warming stimulated aboveground plant biomass production during these periods.

Figure 2.

Responses to warming treatments in winter 2011/12 (active warming for winter warming but no warming for the summer-warming treatment during this period). Greenness at plot level was not measured in February due to snow cover. Leaf C:N was measured for leaves of the same three species (Alopecurus pratensis, Plantago lanceolata, and Rumex acetosa) in each plot. Root mortality is the sum of roots dying between two samplings. Cmic, microbial biomass; WEOC, water-extractable organic C. Means ± SEMs (n = 10) per sampling date and treatment (with the three species per plot as nested replicates for leaf C:N) are displayed. Lowercase letters indicate homogeneous groups per date based on Tukey post hoc tests (only tested if the interaction between warming and time was significant and displayed for dates that differed among the treatment levels in the post hoc test).

A natural cold period when winter warming had melted the snow cover, led to colder minimum temperatures during our intensive winter sampling than under the reference conditions (minimum air temperature at plant height, −14.0 versus −9.7 °C; minimum soil temperature, −4.0 versus −2.2 °C; Supplementary Information Fig. 3). This result supports the notion that winter warming can lead to colder soils if it reduces snow cover20. This frost was the most likely cause of the decrease in greenness (Fig. 2a), the increase in root mortality, and the peaks in microbial biomass (Cmic), water-extractable organic C (WEOC), and bioavailable N (Fig. 2e–h) in the winter-warming treatment, because no other abiotic parameter reached stressful levels during this time (radiation: PAR < 800 µmol m−2 s−1; soil moisture well above the wilting point of 8%).

Discussion

Winter warming was ecologically more important than summer warming in our seasonal warming experiment in a permanent temperate grassland over four consecutive years. Species differ in their potential to profit from a prolonged growing season10. Accordingly, winter warming in our study was accompanied by changes in plant-community composition toward more productive species (Supplementary Information Table 1). More productive (taller) species may benefit more from a longer growing season and thereby become more dominant by outcompeting smaller, light demanding species by shading. Changes in plant-community composition induce lasting changes in ecosystem functioning, relevant not only for aboveground biomass production, but also for decomposition and nutrient cycling12 or N leaching30 and potentially leading to hysteresis and regime shifts in plant-community composition and ecosystem functions31. Changes in plant-community composition are therefore more relevant than short-term physiological effects, which may simply be due to phenotypic plasticity32, are generally reversible and may be transient. The increase in more productive species may further lead to a decrease in short but light-demanding species in the long term. In addition to management effects or eutrophication, winter warming may therefore play a role, which has been overlooked, in the biodiversity decline33 of protected (European Habitats Directives) lowland permanent grasslands.

A reduction in snow cover and the loss of its insulating effect followed by subsequent frost can increase frost damage30,34,35. Frost tolerance differs among grass species36 and can therefore be expected to act as a selective driver that can contribute to changes in community composition. Cold acclimation in microbes is accompanied by net N mineralization37, but the parallel peak in WEOC indicates microbial death rather than dormancy37,38. In addition to the lysis of microbial cells and roots, soil-bound organic C and other nutrients become accessible by physical stress that fragments soil aggregates39. These easily accessible nutrients induce high rates of microbial growth and activities immediately after physical stress40 or with some delay41, in line with the peak in microbial biomass after the frost in our study.

The natural cold period during our intensive winter sampling campaign decreased the minimum soil and air temperatures and presumably induced frost damage in plants and microorganisms in the winter-warming treatment, but winter warming still increased ANPP during the growing season following the frost. For future projections, this result implies that the effects of winter warming will even further increase their effects on ANPP and soil respiration, because such cold periods may eventually become less frequent in an increasingly warming environment1,19.

We focused on separating the effects of summer and winter warming and accounting for the latter. Warming will likely occur throughout the year, even though its magnitude may differ among seasons1,5. Combined warming effects, particularly on opposing trends such as the changes in plant-community composition, are difficult to predict and require further research that includes seasonally non-uniform warming lasting long enough for studying community changes and acclimation effects in plants and microorganisms42,43. Our soil warming of 1.6 °C was at the lower end of commonly applied warming manipulations (1.5 to 6 °C3). The clear and strong ecological net effects (ANPP, plant-community composition, and soil respiration) in this study are therefore even more relevant and emphasize the ecological importance of highly probable winter warming. This is even more remarkable as other warming experiments report high inertia in grassland community composition with changes only after seven years of year-round warming44. We hypothesize that the comparably quick response to winter warming in terms of community composition in our experiment points towards a high vulnerability to warming of cool-temperate ecosystems which formerly showed regular protective snow cover over winter.

Our results emphasize the importance of the seasonality of warming. Mild winter warming was ecologically more relevant than mild summer warming for a cool temperate ecosystem. Our data suggest that this difference is due to the effects of winter warming lengthening the growing season and changing plant-community compositions toward more productive species. Frost damage may mitigate the effects of winter warming, because the reduction in snow cover led to frost damage during natural cold periods. Such soil frosts due to reduced snow cover, however, are expected to only be transient for cool temperate ecosystems. Future warming will therefore likely further increase the stimulation of ecosystem processes mainly by winter warming.

Methods

Study site

This study was conducted in the Ecological-Botanical Garden of the University of Bayreuth, Germany (49°55′19″N, 11°34′55″E; 365 m a.s.l.). The regional climate is temperate and moderately continental (mean annual air temperature of 8.2 °C and mean annual precipitation of 724 mm for 1971–2000; data from the German Weather Service). Mean winter air temperature (October-March) is 3.0 °C, and mean summer air temperature (April-September) is 14.4 °C. The site was covered by snow on an average of 36 d per winter (2009–2014). The soil is a Gleysol. A 30-cm Ap horizon (42% sand, 43% silt, 15% clay) overlays a clayey Bg horizon. The main rooting zone is within the upper 15 cm, and few roots penetrate the Bg horizon. The mean pH of the topsoil is 4.1 (1 M KCl). The experimental site is a semi-natural grassland that has not been plowed or fertilized for at least 25 years. The site was mown twice a year for hay production prior to the start of the experiment, leading to disturbance-tolerant, species-rich, perennial semi-natural grassland communities typical of large areas throughout Europe29 and dominated by tall grasses such as Alopecurus pratensis L. (meadow foxtail) and Arrhenatherum elatius (L.) P.Beauv. ex J.Presl & C.Presl (tall oat-grass). The most common herb species include Plantago lanceolata L. (ribwort plantain), Rumex acetosa L. (common sorrel), and Cerastium fontanum subsp. vulgare (Hartm.) Greuter & Burdet (mouse ear chickweed), and the most abundant legume is Trifolium pratense L. (red clover). One square meter contains an average of 14 species. All plants are C3 species.

Experimental design

The field experiment was initially carried out in a fully crossed two-factorial design manipulating (1) temperature (ambient, winter warming, summer warming) and (2) variability of intra-annual precipitation. We focused on seasonal warming to identify its relative net effects (compared to no warming) using detailed winter measurements of plant performance and soil biotic activity. We collected data from two precipitation treatments (low and high precipitation variability, with the latter including an early summer drought, i.e. 42 d without rainfall, combined with heavy rainfall, i.e. adding the missing amount due to the drought treatment within 2 d, both treatments totaling the same annual precipitation) and accounted for the potential effects of the precipitation treatment by adding it as a random effect in the statistical models (see below and Grant et al.4). Our results were thus generalized to different regimes of growing-season precipitation, which did not interact significantly with the seasonal warming treatment, based on pre-tests with summer precipitation as an additional fixed factor. The design consisted of 30 plots, each 1.5 × 1.5 m, with 10 replicates of each warming treatment (five true replicates of the two precipitation treatments). The warming-treatment plots were blocked within each precipitation treatment, with their position per block assigned randomly.

Temperature was manipulated either during the winter (October-March) or summer (April-September) starting in October 2009. The temperature was increased using overhead infrared heating lamps equipped with reflector domes (IOT/90 250 W, Elstein-Werk M. Steinmetz GmbH & Co. KG, Northeim, Germany) at a height of 0.8 m, theoretically delivering 60 W per plot. The lamps were raised to 1 m when tall grasses reached a height of 0.8 m later in the growing season and were lowered again to 80 cm after the harvest. Ambient plots were equipped with dummy heaters. The spatial homogeneity of the warming was consistently high within the area (1 m²) used to sample all response parameters (ΔTair(+5cm) = 0.2 °C and ΔTsoil(−2cm) = 0.3 °C between five sensors installed at 0, 25, and 50 cm from the center of the plot during winter 2009/2010, and ΔTair(+5cm) = 0.1 °C and ΔTsoil(−2cm) = 0.3 °C between three sensors installed at 0, 37.5, and 75 cm from the center of the plot during summer 2011). Snow depth per plot was measured manually by a yard stick at all days with snow on the ground. Air temperature at plant height within the plot (+5 cm) was measured by thermistors (B57863-106 S302-F40, EPCOS AG, München, Germany) with 10 radiation shields. Soil temperature at −2 cm was measured by the same sensors used for measuring air temperature but without shields (n = 10). Soil moisture was measured by 30 FD-sensors ECH2O (Decagon Devices, Pullman, USA) at −2 to −7 cm. All data were collected from the center of each plot directly below the lamp to avoid possible edge effects created by temperature gradients with increasing distance from the lamp.

Response parameters

Annual net effects of the three warming treatments on aboveground biomass production, plant-community composition, and soil respiration were analyzed throughout the study period (one pre-treatment year and four years of warming). Intensive winter sampling, focusing on plant and soil biotic activity during one winter, was conducted to obtain a better mechanistic understanding of the effects of winter warming.

Annual net effects

Aboveground biomass was destructively harvested twice a year (June and September). Destructive harvests are part of the disturbance regimes of these semi-natural systems, and the frequency, timing, and intensity of our harvests resembled local agricultural routines for an extensively used grassland. For each harvest, a steel frame (0.1 m²) was placed twice in the central part of each plot, so that two samples of plant material per plot could be collected. All plant material was cut 3 cm above the soil surface within the steel frame. One sample was sorted into functional groups (forbs, graminoids, and legumes), and the other sample was sorted into species. All plant material was dried to a constant weight at 60 °C and then weighed (Ohaus NavigatorTM, Ohaus Corporation, Parsippany, USA; accuracy ±0.01 g). Total annual aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) was calculated as the total biomass of all plant samples within each plot for each year based on the sampled area of 0.2 m². The entire plot was then mown to +3 cm.

Species-specific cover was estimated visually on a continuous scale immediately before each summer harvest and included all species within the central 1 m² of each plot. The same two observers working together estimated all covers. We used these data to determine the changes in community composition, quantified as the compositional changes in each plot, comparing its pattern of species abundance to its initial pattern (before the start of the experimental warming) at each time step using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity45. Non-random occurrence of particular species among the warming treatments was tested by an analysis of indicator species46. The statistical significance of preferential occurrence was evaluated using a randomization procedure with 1000 permutations46. No species preferentially occurred in 2009, the pre-treatment year. The results for these response parameters were qualitatively similar whether species-specific biomass data or cover data were used. We report the cover data, because this data set includes more species due to the larger spatial scale (1 versus 0.1 m²).

Soil respiration was measured in each plot with a respiration chamber connected to a non-dispersive infrared gas analyzer (SPC-1 & EGM-4, PP-systems, Amesbury, USA). The respiration chamber was placed on PVC collars to close the system. The collars (10 cm in diameter, 5 cm in height) were installed 4 cm into the soil one month before the start of measurements. The collars were elongated by open adaptor tubes to conduct measurements above the snow if snow was forecasted. All aboveground plant material was clipped from the collar the day before each measurement. Measurements were conducted monthly but with weekly or biweekly measurements during some campaigns. CO2 fluxes were measured for 4 min to reach a stable flux, and the average of the final four flux values was used for the analyses.

Intensive winter sampling

A set of response parameters of plant and soil biotic activity was quantified during winter 2011/2012 to identify the processes leading to changes in the net effects described above in response to winter warming. Samples were collected each month during the period of winter warming (October-March, with a final sampling in early April).

Potential changes in the length of the growing season were quantified by measuring the greenness of the plots. Greenness is directly correlated with photosynthetic potential47, so we used it as a surrogate for potential aboveground plant activity. Plot greenness was quantified monthly using digital photographs taken under standardized light conditions. A portable light-tight box (56 × 55 × 75 cm) with a camera (Nikon D2x, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and artificial lighting (two flashes) was used. The calculation of greenness was based on Marchand et al.47, using a transformation from RGB pictures to the HSL color space. The threshold for the ‘greenness’ of the hue band was determined using manually calibrated/optimized reference lookup tables for all bands implemented as lookup images. The percentage of greenness was calculated and processed with the same lookup tables and same parameters for all pictures and all time steps using ImageMagick 6.7.6–5 (ImageMagick Studio LLC, Landenberg, USA). Consequently, our ‘greenness’ is a relative measure comparable among all pictures in our study, expressed as the relative number of green pixels, i.e. the photosynthetic potential, of the plant community. The relative differences among the treatments were especially important, because they indicated alterations from natural seasonal patterns of greenness.Greenness could not be measured in February because snow covered the plots.

Leaf C and N concentrations were measured repeatedly to determine if the plants were taking up N over winter, which could have been mineralized by increased soil biotic activity (see below for quantification) or lysed by soil biota due to frost damage. Changes in leaf C:N can (1) indicate plant activity, (2) account for the fate of available N in the soil, and (3) help to account for the higher aboveground plant biomass production during the growing season. Soil CN ratio was 11.8 ± 0.2 SE in summer 2011. Leaf C and N were determined monthly for mixed samples of three leaves from each of the three most frequent species (40, 4, and 3% mean covers per plot in summer 2012 for Alopecurus pratensis, Plantago lanceolata, and Rumex acetosa, respectively). The leaves were oven-dried at 70 °C for 72 h, pulverized, re-dried at 70 °C for 48 h, and stored in desiccators until analyzed (<15 d). Thereafter, 0.7–1.5 mg of the dried and pulverized samples were weighed with a Mettler Toledo MX5 microbalance, and the concentrations of the elements were determined by combustion coupled to gas chromatography using an Elemental Analyzer CHNS Eurovector 3011 Thermo Electron Gas Chromatograph, model NA 2100 (CE Instruments/Thermo Electron, Milan, Italy).

Fine roots are essential for taking up water and nutrients. Differences in winter root growth or mortality can provide information on frost damage or increased belowground plant activity, which can affect the production of annual aboveground biomass48. Root length at each sampling date and root mortality between the sampling dates were determined monthly using a minirhizotron technique. A clear plastic tube (5 cm diameter) was installed at 45° to a depth of 45 cm in each plot in 2008. The aboveground sections of the tubes were covered with adhesive aluminum foil, and the tubes were capped to prevent the entry of water, dust, light, and heat. The roots were scanned with a root scanner adapted from an ordinary computer scanner (Optic slim 2400+) mounted on a metal pole that was rotated by an electric motor. The scans (18 × 21.6 cm) were at an angle of about 300°. Root lengths for the entire scan were quantified for each tube using Rootfly (Rootfly Development Team, Version 2.0.2, GNU General Public License). Root mortality was calculated as the length of roots dying between the sampling dates.

Soil microbiotas are essential for decomposing organic matter and for soil respiration. Cmic was measured by chloroform-fumigation extraction49 using 5 g of fresh soil (three technical replicates per plot collected using a stainless-steel corer to −10 cm) within 2 d after sampling. Samples in glass vials were placed in a desiccator containing 25 mL of ethanol-free chloroform (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and then extracted with 20 mL of 0.01 M CaCl2 (1:4 extraction ratio) in a rotary shaker for 30 min. The soil suspension was then filtered with a 595 1/2 paper filter (Whatman International LTD, VWR International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Non-fumigated samples served as controls to assess the amount of WEOC. WEOC and microbial biomass were measured using a total organic-C analyzer DIMATOC 2000 (DIMATEC Analysentechnik GmbH, Essen, Germany) by catalytic high-temperature oxidation. Cmic was calculated using the method described by Joergensen and Mueller50: Cmic = EC/KEC, where EC is the difference between the C extracted from the fumigated and nonfumigated samples, and KEC = 0.41. Non-fumigated extracts were also used to measure water-extractable N, which was considered as the bioavailable fraction (tNb).

Statistical analyses

The ecological relevance of seasonal warming throughout the study period was determined by calculating Hedges’ d effect sizes for winter and summer warming and comparing them to the reference. A treatment was considered to have a significantly positive effect if the 95% confidence intervals of the mean effect size did not include values <0 and was considered to have a significantly negative effect if the intervals did not include values >051. The analyses used the R ‘effsize’ package, version 0.7.1. These results were supported by linear mixed-effects models (see below), which qualitatively produced the same insights.

For the detailed winter-sampling campaign, we constructed linear mixed-effect models in combination with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to test for effects of the warming manipulations on each response variable. The blocked design was taken into account by a random factor describing the spatial configuration of the experiment (row/column) in the model52. The repeated measurements over time were also taken into account by adding the plot ID as a random effect. Fixed effects included the warming treatment and its interaction with time. Residual versus fitted plots and qq-plots based on the model were checked for homogenous variance and normal distributions of the residuals to validate the linear mixed-effect models52. The response parameters for which the parametric assumptions were not met were transformed as: rank (leaf C:N), log(1 + soil respiration), rank(root length), log(1 + tNb). For leaf C:N, species identity was added as an additional random effect if the initial models failed to identify significant interactions between warming treatment and species identity. The significance level for all tests was set to 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.3.253. The ‘lmerTest’ package, version 2.0–33, and the ‘emmeans’ package, version 1.1, were used for the linear mixed-effect models and multiple post-hoc comparisons, respectively. The analysis of indicator species used the ‘labdsv’ package, version 1.8-0.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the help of the technicians (Elke König, Stefan König, and Gudrun Hufnagel), interns, and students that participated in the experiment. In particular, we thank Reinhold Stahlmann for developing the protocol for the greenness analyses and conducting the cover estimates, together with JK and Kerstin Grobe for preparing and analyzing the soil samples. This study was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of the Environment and Public Health (ZKL01Abt7 18456). JS and JP were supported by the European Research Council Synergy grant SyG-2013-610028 IMBALANCE-P. MASAK was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the BonaRes project SUSALPS (Project Number: 031B0027C). We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge from the DFG (German Research Foundation, 393148499) and the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Greifswald.

Author Contributions

A.J., C.B. and J.K. initiated the project, designed the experiment, and managed the project; J.K., K.G., V.H., M.A.S.A.K., A.V.M. and J.Sch. collected the data; V.H., A.V.M., J.S. and J.Sch. performed the laboratory analyses; J.K. analyzed the data; J.K., K.G., V.H., A.V.M., J.P., K.P., J.S. and M.S. wrote the methods section; and J.K. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-51221-w.

References

- 1.IPCC (ed.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2013).

- 2.EEA. Projected changes in annual, summer and winter temperature. European Environmental Agency (2014).

- 3.Rustad LE, et al. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia. 2001;126:543–562. doi: 10.1007/s004420000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreyling J, Beier C. Complexity in climate change manipulation experiments. Bioscience. 2013;63:763–767. doi: 10.1093/bioscience/63.9.763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia J, et al. Terrestrial carbon cycle affected by non-uniform climate warming. Nature Geosci. 2014;7:173–180. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larcher, W. Physiological Plant Ecology. 4th ed. (Springer, Berlin, 2003).

- 7.Birgander J, Rousk J, Olsson PA. Warmer winters increase the rhizosphere carbon flow to mycorrhizal fungi more than to other microorganisms in a temperate grassland. Glob Change Biol. 2017;23:5372–5382. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant, K., Kreyling, J., Beierkuhnlein, C. & Jentsch, A. Importance of seasonality for the response of a mesic temperate grassland to increased precipitation variability and warming. Ecosystems103, 10.1007/s10021-017-0122-3 (2017).

- 9.Schuerings J, et al. Absence of soil frost affects plant-soil interactions in temperate grasslands. Plant Soil. 2013;371:559–572. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1724-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams CM, Henry HAL, Sinclair BJ. Cold truths: how winter drives responses of terrestrial organisms to climate change. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 2015;90:214–235. doi: 10.1111/brv.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardinale BJ, et al. The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am J Bot. 2011;98:572–592. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelissen JHC, et al. Global negative vegetation feedback to climate warming responses of leaf litter decomposition rates in cold biomes. Ecol Lett. 2007;10:619–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikan CJ, Schimel JP, Doyle AP. Temperature controls of microbial respiration in arctic tundra soils above and below freezing. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contosta AR, Frey SD, Ollinger SV, Cooper AB. Soil respiration does not acclimatize to warmer temperatures when modeled over seasonal timescales. Biogeochemistry. 2013;112:555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10533-012-9748-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmesan C, Yohe G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature. 2003;421:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye DW. Effects of climate change on phenology, frost damage, and floral abundance of montane wildflowers. Ecology. 2008;89:353–362. doi: 10.1890/06-2128.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreyling J. Winter climate change: a critical factor for temperate vegetation performance. Ecology. 2010;91:1939–1948. doi: 10.1890/09-1160.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry HAL. Climate change and soil freezing dynamics: historical trends and projected changes. Clim Change. 2008;87:421–434. doi: 10.1007/s10584-007-9322-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreyling J, Henry HAL. Vanishing winters in Germany: soil frost dynamics and snow cover trends, and ecological implications. Clim Res. 2011;46:269–276. doi: 10.3354/cr00996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groffman PM, et al. Colder soils in a warmer world: A snow manipulation study in a northern hardwood forest ecosystem. Biogeochemistry. 2001;56:135–150. doi: 10.1023/A:1013039830323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson EA, Janssens IA. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature. 2006;440:165–173. doi: 10.1038/nature04514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai E, et al. A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. New Phytol. 2013;199:431–440. doi: 10.1111/nph.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skogland T, Lomeland S, Goksoyr J. Respiratory burst after freezing and thawing of soil - experiments with soil bacteria. Soil Biol Biochem. 1988;20:851–856. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(88)90092-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matzner E, Borken W. Do freeze-thaw events enhance C and N losses from soils of different ecosystems? A review. Eur J Soil Sci. 2008;59:274–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2007.00992.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duran J, et al. Winter climate change affects growing-season soil microbial biomass and activity in northern hardwood forests. Glob Change Biol. 2014;20:3568–3577. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokhorst S, Bjerke JW, Melillo J, Callaghan TV, Phoenix GK. Impacts of extreme winter warming events on litter decomposition in a sub-Arctic heathland. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2010;42:611–617. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter J, et al. Combined effects of multifactor climate change and land-use on decomposition in temperate grassland. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;60:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q, et al. Extension of the growing season increases vegetation exposure to frost. Nature Comm. 2018;9:426. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beierkuhnlein C, Thiel D, Jentsch A, Willner E, Kreyling J. Ecotypes of European grass species respond specifically to warming and extreme drought. J Ecol. 2011;99:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01809.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreyling J, et al. Nitrogen leaching is enhanced after a winter warm spell but mainly controlled by vegetation composition in temperate zone mesocosms. Plant Soil. 2015;396:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2587-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheffer M, Carpenter SR. Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: linking theory to observation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jentsch A, et al. Climate extremes initiate ecosystem-regulating functions while maintaining productivity. J Ecol. 2011;99:689–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01817.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan ER, Powell I, Ashton PA. Regional stability versus fine scale changes in community composition of mesotrophic grasslands over 25 years. New Journal of Botany. 2017;7:25–38. doi: 10.1080/20423489.2017.1344042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bokhorst SF, Bjerke JW, Tømmervik H, Callaghan TV, Phoenix GK. Winter warming events damage sub-Arctic vegetation: consistent evidence from an experimental manipulation and a natural event. J Ecol. 2009;97:1408–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01554.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malyshev AV, et al. Plant responses to climatic extremes: within-species variation equals among-species variation. Glob Change Biol. 2016;22:449–464. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudleifsson BE, Andrews CJ, Bjornsson H. Cold hardiness and ice tolerance of pasture grasses grown and tested in controlled environments. Can J Plant Sci (Canadian Journal of Plant Science) 1986;66:601–608. doi: 10.4141/cjps86-080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schimel J, Balser TC, Wallenstein M. Microbial stress-response physiology and its implications for ecosystem function. Ecology. 2007;88:1386–1394. doi: 10.1890/06-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grogan P, Michelsen A, Ambus P, Jonasson S. Freeze-thaw regime effects on carbon and nitrogen dynamics in sub-arctic heath tundra mesocosms. Soil Biol Biochem. 2004;36:641–654. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oztas T, Fayetorbay F. Effect of freezing and thawing processes on soil aggregate stability. Catena. 2003;52:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0341-8162(02)00177-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iovieno P, Bååth E. Effect of drying and rewetting on bacterial growth rates in soil. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2008;65:400–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Göransson H, Godbold DL, Jones DL, Rousk J. Bacterial growth and respiration responses upon rewetting dry forest soils. Impact of drought-legacy. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;57:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki M, et al. Effects of long-term experimental warming on plants and soil microbes in a cool temperate semi-natural grassland in Japan. Ecol Res. 2016;31:957–962. doi: 10.1007/s11284-016-1386-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero-Olivares AL, Allison SD, Treseder KK. Soil microbes and their response to experimental warming over time. A meta-analysis of field studies. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;107:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Z, et al. Evidence for long-term shift in plant community composition under decadal experimental warming. J Ecol. 2015;103:1131–1140. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreyling J, et al. Winter warming pulses affect the development of planted temperate grassland and dwarf-shrub heath communities. Plant Ecology and Diversity. 2011;4:13–21. doi: 10.1080/17550874.2011.558125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dufrene M, Legendre P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr. 1997;67:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marchand FL, et al. Climate warming postpones senescence in High Arctic tundra. Arct Antarct Alp Res. 2004;36:390–394. doi: 10.1657/1523-0430(2004)036[0390:CWPSIH]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tierney GL, et al. Soil freezing alters fine root dynamics in a northern hardwood forest. Biogeochemistry. 2001;56:175–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1013072519889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem. 1987;19:703–707. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(87)90052-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joergensen RG, Mueller T. The fumigation-extraction method to estimate soil microbial biomass. Calibration of the kEN value. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:33–37. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(95)00101-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. Introduction to meta-analysis (Wiley, Chichester, 2010).

- 52.Faraway, J. J. Extending the Linear Model with R - Generalized Linear, Mixed Effects and Nonparametric Regression Models (Chapman & Hall/CRC, Baco Raton, 2006).

- 53.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org, Vienna, Austria, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.