Abstract

1H-detected solid-state NMR experiments feasible at fast magic-angle spinning (MAS) frequencies allow accessing 1H chemical shifts of proteins in solids, which enables their interpretation in terms of secondary structure. Here we present 1H and 13C-detected NMR spectra of the RNA polymerase subunit Rpo7 in complex with unlabeled Rpo4 and use the 13C, 15N, and 1H chemical-shift values deduced from them to study the secondary structure of the protein in comparison to a known crystal structure. We applied the automated resonance assignment approach FLYA including 1H-detected solid-state NMR spectra and show its success in comparison to manual spectral assignment. Our results show that reasonably reliable secondary-structure information can be obtained from 1H secondary chemical shifts (SCS) alone by using the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS rather than by TALOS. The confidence, especially at the boundaries of the observed secondary structure elements, is found to increase when evaluating 13C chemical shifts, here either by using TALOS or in terms of 13C SCS.

Keywords: Rpo4/7, solid-state NMR, carbon and proton assignments, secondary chemical shifts, ssFLYA

Introduction

Solid-state NMR and, in particular, proton-detected spectroscopy under fast MAS allows to characterize larger and larger proteins and protein complexes (Linser et al., 2011; Andreas et al., 2015; Struppe et al., 2017; Schubeis et al., 2018; Bougault et al., 2019). Here, we demonstrate the resonance assignment and secondary-structure determination of the subunit Rpo7 of the archaeal DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RNAP) in the context of the protein complex Rpo4/Rpo7 (33.5 kDa). RNAPs from bacteria, archaea, and eukarya are well-characterized in terms of their subunit composition, as well as their structure, and much is known about the regulation mechanisms and complex interplay of transcription factors throughout the transcription cycle of initiation, elongation, and transcription termination (Werner and Grohmann, 2011; Sainsbury et al., 2015; Hantsche and Cramer, 2016). Especially the archaeal RNAP has served as a model system for dissecting the functions of the individual subunits of the human RNAP II (Werner, 2007, 2008).

Two of these subunits, Rpb4/Rpb7, that form a stalk-like protrusion in RNAP II, or rather their archaeal homologs Rpo4/Rpo7 (or Rpo4/7), are known to bind the nascent single-stranded RNA, contribute to transcription initiation as well as termination efficiency and increase processivity during elongation (Meka, 2005; Újvári and Luse, 2006; Grohmann and Werner, 2010, 2011). Yet, how these functions are achieved in molecular detail remains elusive, and conformational changes of Rpo4/7 in response to RNA binding have not been detected when probed by labeling techniques, such as fluorescence and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (Grohmann et al., 2010). NMR spectroscopy could provide further information at the atomic level.

As a first step, we present the 1H, 13C, and 15N protein resonance assignment employing solid-state MAS experiments of a sedimented Rpo4/7 complex from the archeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. For this, we labeled the Rpo7 subunit uniformly with 13C/15N, while Rpo4 was employed at natural isotopic abundance. This enabled us to selectively study the Rpo7 subunit within the complex. We assigned, on the basis of the acquired spectra and using different assignment strategies, ~80% of the Cα, Cβ, and backbone nitrogen atoms. It has been demonstrated that NMR chemical-shift values encode for the secondary structure (Wishart et al., 1992; Wishart and Sykes, 1994; Wang, 2002; Shen et al., 2009). We compared the secondary structure predictions based on the different chemical shifts, and compared them also to the known crystal structure. We found that for proton resonances, the most reliable information can be derived from 1H secondary chemical shifts (SCS) using the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS. Nevertheless, 13C chemical shifts are found to be more reliable in terms of secondary-structure information, both directly from SCS and from TALOS.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification, Sample Preparation

Plasmids pET21_Rpo7 and gGEX_2k_Rpo4 were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells separately for Rpo4 and Rpo7. Rpo4 was overexpressed with an N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tag in rich medium (Terrific Broth, 2006) and purified via affinity chromatography using glutathione agarose (GSTrap, GE Healthcare, Glattbrugg, Switzerland) using P100 buffer (20 mM tris/acetate pH 7.9, 100 mM K acetate, 10 mM Mg acetate, 0.1 mM ZnSO4, 5 mM DTT, 10% (w/v) glycerol) and 10 mM reduced glutathione for elution, similar to previous protocols (Werner and Weinzierl, 2002; Klose et al., 2012). The GST-tag was cleaved by overnight incubation with thrombin at 37°C. To deactivate and remove the GST-tag, a 20-min heat shock of the cleaved elution fractions at 65°C was applied with subsequent centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 20 min, 4°C), leaving purified Rpo4 in the supernatant. For isotope labeling with 15N and 13C, Rpo7 mutant S65C was expressed in M9-minimal medium (Studier, 2005) consisting of 6.8 g Na2HPO4, 3 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 1 ml of each 1 M MgSO4, 10 mM ZnCl2, 1 mM FeCl3, and 100 mM CaCl2 per 1 L medium, supplemented with 10 ml MEM vitamin solution (100×). One gram 15NH4Cl and 2.5 g 13C-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, USA) were the only nitrogen and carbon sources. Rpo7* (the asterisk denotes isotope labeling) purification from inclusion bodies was carried out as described previously (Werner and Weinzierl, 2002; Klose et al., 2012).

The complex formation of Rpo4 and Rpo7* (with 20% excess) was carried out by unfolding and stepwise refolding dialysis in P100 buffer using urea (6, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0.5, and 0 M urea concentrations, 1 h per step, room temperature). Subsequently, a 20 min heat shock at 65°C and a subsequent centrifugation step (8,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C) was applied to remove excess or misfolded Rpo7* after the dialysis. Purity and stability of the complex was confirmed by SDS and native page (Figure S1). All chemicals were of p.a. grade and purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Buchs, Switzerland), unless stated otherwise.

Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy

Rpo4/7* supplemented with DSS and sodium azide was sedimented into NMR rotors (0.7 and 3.2 mm, Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany) by ultracentrifugation (35,000 rpm, 4°C, 16 h) using home-made filling tools (Böckmann et al., 2009) resulting in 0.6 and 24 mg protein in the rotors with 0.7 and 3.2 mm diameter, respectively. Solid-state NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III 850 MHz NMR spectrometer using either a 3.2 mm Bruker “E-free” probe or a 0.7 mm Bruker triple-resonance probe. The MAS spinning frequencies were set to 17.0 kHz for the 3.2 mm rotor and 110 kHz for the 0.7 mm rotor, with sample temperatures of 16°C (lowest possible temperature in this set-up) and 5°C for the 0.7 and 3.2 mm rotors, respectively. The 2D and 3D spectra were processed with TopSpin (version 3.5, Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany) and analyzed in CcpNmr Analysis 2.4.2 (Stevens et al., 2011). More details of the conducted experiments are presented in Table S1. Polarization transfers between H-C and H-N used adiabatic cross polarization (Hediger et al., 1995), as did N-C polarization transfers (Baldus et al., 1996), while C-C transfers used either DARR (Takegoshi et al., 2003) or DREAM (Verel et al., 2001).

The 13C-detected spectra used for the assignment were all recorded on a single sample (3.2 mm rotor). Reproducibility was checked by 2D measurements on samples from two different preparations in 0.7 mm rotors, which yielded identical spectra in all cases.

The obtained assignment was deposited in the BioMagResBank under accession number 27959.

TALOS+ Predictions and FLYA Calculations

TALOS+ predictions were performed using version 3.8 (Shen et al., 2009). The secondary structure assignments based on the DSSP algorithm (Kabsch and Sander, 1983) were used as given in the corresponding PDB entry 1GO3 (Todone et al., 2001) and the 3D atomic coordinates were extracted from the same PDB entry. Solid-state FLYA calculations (Schmidt and Güntert, 2012; Schmidt et al., 2013) were performed with CYANA version 3.97 (Güntert and Buchner, 2015). Peak lists of 13C and 1H-detected spectra were used, using the peak lists from the resonance assignment (manual peak lists) or using automatically generated peak lists. Automated peak picking has been performed in CcpNmr using the implemented picking routine. The lowest contour level was set to 2.0–3.0 time noise RMSD for this process. The tolerance value for chemical-shift matching was set to 0.55 ppm for 13C, 15N, and 0.3 ppm for 1H.

Results and Discussion

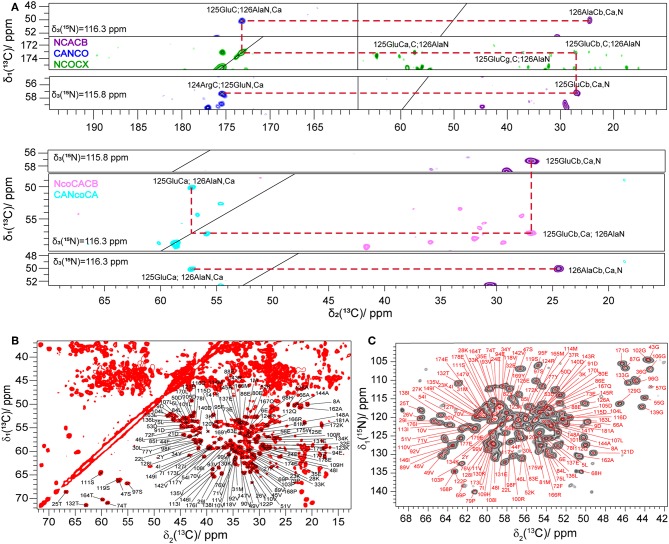

Assignment of 13C Detected Solid-State NMR Spectra

The 13C and 15N-MAS solid-state NMR spectra of Rpo4/7* show well-dispersed signals and roughly the expected number of peaks (Figure S2) in the region of serine (four out of six expected peaks), threonine (4/4), alanine (7/8), and glycine (12/16) as can be seen in the 2D dipolar correlation spectra in Figure 1, suggesting that the sample contains Rpo4/7* in a single, well-defined conformation. The 13C-linewidths are on the order of 115 Hz, which points to a homogeneous sample.

Figure 1.

(A) Example of a 13C, 15N sequential resonance walk. (B) 2D 13C, 13C DARR spectrum of Rpo4/7* measured at 20.0 T with a MAS frequency of 17 kHz and a DARR mixing time of 20 ms. (C) 2D NCA spectrum of Rpo4/7* measured at 20.0 T with a MAS frequency of 17 kHz. In (B,C), Cα, and Cβ peaks are labeled according to the manually created shift list using the CcpNmr software.

Seven 3D 13C-detected spectra (NCACB, NCACX, CANCO, NCOCX, NcoCACB, CANcoCA, and CCC) were measured to obtain the 13C and 15N assignment. The 13C and 15N assignment was mainly achieved by a combination of two strategies described earlier (Schuetz et al., 2010) and shown in Figure 1A. The first is based on a sequential walk using NCACB, CANCO, NCOCX, the second uses the relayed experiments NcoCACB and CANcoCA, in combination with NCACB. The side chains were mainly assigned by analyzing NCACX and CCC spectra [employing Dipolar Recoupling Enhanced by Amplitude Modulation (DREAM) (Verel et al., 2001; Westfeld et al., 2012) and Dipolar Assisted Rotational Resonance (DARR) (Takegoshi et al., 2003) transfer steps].

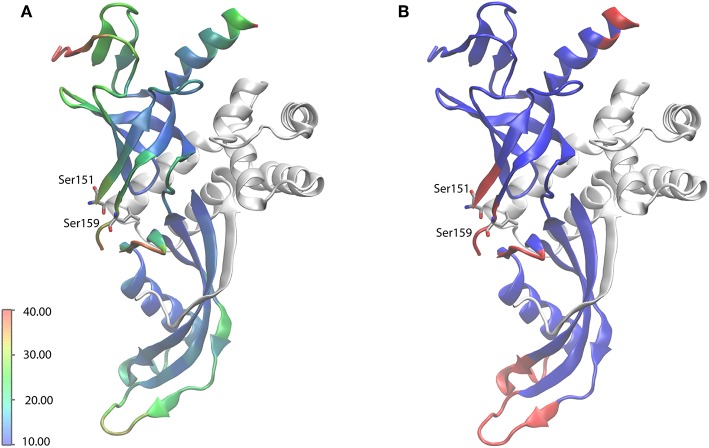

Manual analysis of all 3D spectra resulted in the assignment shown in the 2D 13C, 13C DARR (Figure 1B) and 2D 15N, 13C NCA (Figure 1C) spectra, where 99% of all visible peaks are assigned. The assignment graph is shown in Figure S3. Statistics of the manually performed peak assignment is shown in Table S2. The resonances of most of the unassigned residues could thus neither be detected in 3D nor in 2D spectra, most probably because they are located in flexible parts of the protein. Figure 2 illustrates the spatial correlation between unassigned residues and the crystallographic B-factor, which shows that the most flexible part, the RNA binding loop (Meka, 2005), which is not resolved in the crystal structure (Todone et al., 2001), is found to be close to the unassigned residues Ser151–Ser159. The invisible residues are, however, not flexible enough to be visible in an INEPT spectrum (data not shown).

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of Rpo4/7 (PDB: 1GO3). Rpo4 is shown as white ribbons. (A) Rpo7 (ribbons), colored according to the crystallographic B factor (see scale bar, in Å2). (B) Rpo7 (ribbons), colored blue and red for backbone-assigned and unassigned residues, respectively. The RNA-binding loop, the region with the highest flexibility, for which no coordinates are available, is indicated by the flanking residues S151 and S159.

Assignment of 1H-detected Solid-State NMR Spectra

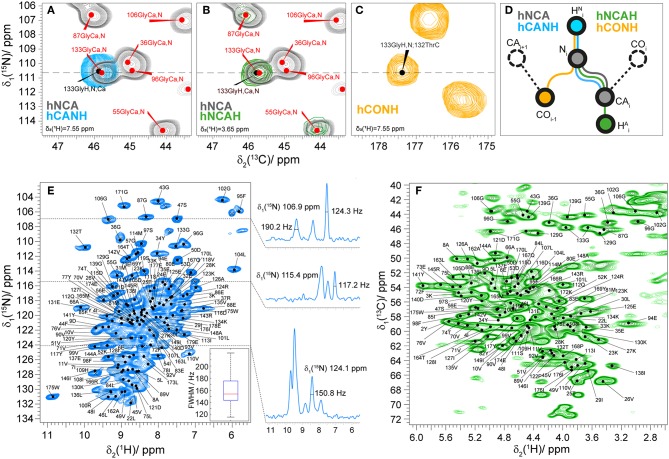

To assign the amide HN and aliphatic Hα protons of fully protonated Rpo7* in complex with Rpo4, we used proton-detected spectroscopy at 110 kHz MAS frequency. The assignment of the 2D hNH fingerprint spectrum is shown in Figure 3. The assignment was done using three 3D spectra, namely hCANH, hNCAH, and hCONH (Barbet-Massin et al., 2014; Penzel et al., 2015), and taking advantage of the 13C and 15N peak assignment described above. Details of the experiments are given in Table S1. The assignment of the NCA spectrum was transferred peak by peak to hCANH (Figures 3A,D) and hNCAH (Figures 3B,D) spectra. To confirm the assignment of amide protons, an additional hCONH spectrum was used to verify the CO chemical shift of the previous residue (Figures 3C,D). In total, 97% of the amide protons and 93% of the Hα protons for which Cα and N assignments exist could be assigned. In the assignment graph of Figure S2 those atoms are highlighted in blue and red, respectively.

Figure 3.

(A) 2D NCA spectrum (gray) and 2D plane of a 3D hCANH (cyan) spectrum at δ(1H) = 7.6 ppm showing an example of the assignment transfer for 133Gly; (B) 2D NCA (gray) spectrum and 2D plane of a 3D hNCAH (blue) spectra at δ(1H) = 3.7 ppm showing the example of the assignment transfer for 133Gly; (C) 2D plane of hCONH spectrum δ(1H) = 7.6 ppm; (D) schematic representation of the assignment transfer for HN and Hα atoms; (E) 2D hNH correlation spectrum of fully protonated Rpo4/7* at 110 kHz MAS. The spectrum includes labels for the 15N-1H peaks as predicted from the manually created shift list. On the right side of the figure 1D traces for 1H are presented at the corresponding 15N frequencies. The 1H linewidth characteristics of the full population of marked cross-peaks are summarized in the boxplot in the bottom right, indicating the maximum, 3rd quartile, mean, 1st quartile and minimum value of proton FWHM linewidth in Hz with a mean value of 160 ± 40 Hz. (F) 2D hCH correlation spectrum of fully protonated Rpo4/7* at 110 kHz MAS with peaks labeled as in (E).

The mean value and standard deviation of the 1H linewidths of the fully protonated hNH spectrum are 156 ± 40 Hz for all the peaks marked in Figure 3E. On the right side of the spectra 1D traces of 1H are shown at the corresponding 15N frequencies with linewidths of selected peaks.

The results of the manual assignment procedure were validated by automated resonance assignments as implemented in the solid-state FLYA algorithm (Schmidt and Güntert, 2012; Schmidt et al., 2013). In addition to the 13C and 15N chemical shifts, 1H solid-state chemical shifts were assigned as well in an automated process. Figure S4A illustrates the good agreement between the manual assignments and the assignments obtained by FLYA. For residues shown in green, the FLYA assignment agreed with the manual assignment (within a tolerance of 0.55 ppm for 13C, 15N, and 0.3 ppm for 1H). A few significant differences (red) were observed. In those cases, the manual assignment was carefully verified and found to be consistent. Agreement (including both dark and light green residues) between FLYA and the manually assigned backbone atoms was found for 95% of 15N, 92% of 13C', 95% of 13Cα, 87% of HN, and 89% of Hα atoms. The FLYA algorithm was also applied using automatically picked peak lists as input, and we found agreement to 82% of 15N, 84% of 13C', 82% of 13Cα, 75% of HN, and 76% of Hα atoms (Figure S4B). We conclude that the automatic assignment provides a good starting point for manual assignment or a good check of manual results.

Secondary Structure From 13C- and 1H-detected Spectra

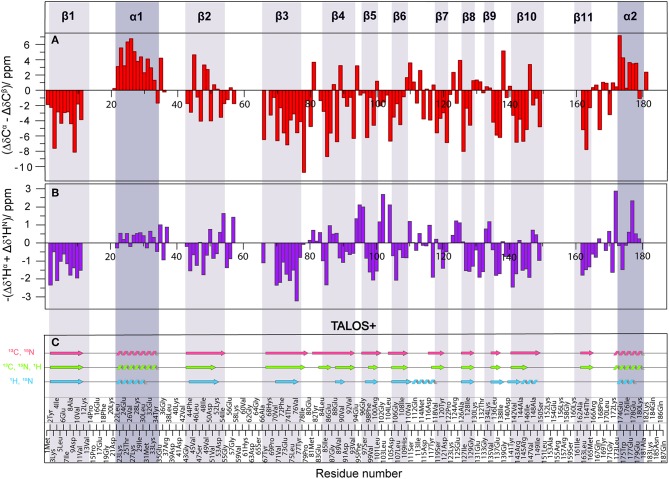

In order to compare the secondary structure determined by different approaches from solid-state NMR chemical shifts, either using SCS or by backbone dihedral angle statistics [TALOS+ (Shen et al., 2009)], we used the X-ray crystal structure of Rpo4/7 determined at 1.75 Å [PDB: 1GO3 (Todone et al., 2001)] as a common reference. The positions of the secondary structure elements were determined from the X-ray coordinates via the algorithm DSSP (Kabsch and Sander, 1983). The results are indicated at the top of Figure 4, Figures S5, S6 as well as by the gray bars.

Figure 4.

(A) Difference of Δδ(13Cα) and Δδ(13Cβ) secondary chemical shifts (SCS) (red). (B) Negative sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS (purple). SCS are obtained by subtracting the random-coil shifts from the observed chemical shifts. Positive SCS differences indicate α-helices, negative SCS difference β-sheets. (C) Secondary structure based on 13C and 15N (light red), 1H and 15N (light blue) and all (light green) chemical shifts using TALOS+ (Shen et al., 2009). Secondary structure elements observed by crystallography are shown as dark (α-helix) and light (β-sheet) gray shaded areas, according to PDB 1GO3 (Todone et al., 2001).

As an indicator for the secondary structure, the SCS of Cα, Cβ, CO, as well the SCS difference of Cα and Cβ were calculated and are visualized in Figures S5, S6. For solid-state NMR, the most commonly used indicator is ΔδCα-ΔδCβ which has the advantage of being independent from reference errors (Spera and Bax, 1991). Three or more negative values in a row indicate a β-sheet, four or more positive values an α-helix. For reference, the positions of the secondary structure elements were determined from the X-ray coordinates. The results are indicated in Figure 4A, Figures S5A, S6A, and Table S3. Overall, the correspondence is good, with some significant deviations in the β-strands, in particular β2. Upon visual inspection of the structure of β2 and β3 in the crystal structure (Figure S7), it becomes clear that this is related to the fact that β2 is rather distorted and irregular, while β3 is more regular. The difference between these two β-sheets is also clearly seen in the Ramachandran plots (Figure S8). The differences in the NMR SCS are therefore based on actual structural properties.

To obtain secondary-structure information from proton-detected fingerprint spectra, SCS of both 1Hα and 1HN were used (Figure 4B, Figures S5B, S6A, Table S3). It is well-known (Wang, 2002), that 15N SCS is a poor indicator for secondary structure (Figures S5, S6, orange). Instead, the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS appears to be a suitable measure for secondary structure identification (Figure 4, Figures S5, S6, purple), even though summing up doesn't compensate for referencing errors. While not as precise as the 13C chemical shifts, the sum of the two proton SCS still provides useful information about secondary structure.

Our results are similar to solution NMR in that SCS data of 1Hα for α-helices were found more reliable than that of 1HN (Wang, 2002). We found the 13Cα-13Cβ SCS data to be a more suitable indicator than SCS sum 1Hα + 1HN data. Similarly, 1Hα SCS were shown (Wang, 2002) to be on average more sensitive in distinguishing β-sheets from random coil conformations than 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts. In our case 13Cα-13Cβ SCS data were the most reliable. However, for big proteins where transfer efficiencies are not always good, 13Cβ data may be unavailable (Penzel et al., 2015; Stöppler et al., 2018). We identified that, besides of 13Cα SCS, the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS is a suitable alternative parameter to derive secondary structure.

Additionally, secondary-structure elements were predicted using the software TALOS+ (Shen et al., 2009) and are shown in Figure 4C. Three different combinations of chemical shifts derived from manual assignment were used: 13C and 15N, 1H and 15N, and all three available shifts. The combination of 13C and 15N data extracted using TALOS+ (light red) yielded the most promising results, as the predicted secondary structure fits well with the crystal structure, including strand β2 and β10 that were only incompletely recognized by the SCS data. Surprisingly, TALOS+ results did not improve upon inclusion of 1H chemical shifts (light green); instead a disruption for strand β4 appeared and strands β2, β5, and β10 became shorter (see also Figure S9 for a comparison in terms of backbone dihedrals). In order to check the reliability of TALOS+ secondary structure results for cases where 13C data are absent, we evaluated the combination of 1H and 15N chemical-shift values (light blue). The calculation resulted in two additional misplaced α-helices, which was not the case for other chemical-shift combinations that included 13C data. Therefore, while TALOS+ predictions that included 13C chemical shifts were successful, calculations including only 1H and 15N chemical shifts were here found to be less reliable than SCS analysis when the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS is used.

Conclusions

Using MAS solid-state NMR, we sequentially assigned 78% of the 13C, 15N resonances of the RNA polymerase subunit Rpo7 in complex with unlabeled Rpo4, and successfully transferred these to 1H detected NMR spectra assigning ~70% of the 1HN and 1Hα resonances. Further assessing the secondary structure in comparison to the known crystal structure, our results confirm that 13C SCS are a bona fide predictor of secondary structure elements. While using only 1Hα or 1HN SCS alone showed an increased uncertainty in the boundaries of observed secondary structure elements compared to the crystal structure, in cases where 13Cβ chemical shifts are not available, secondary structure elements can be identified using either 13Cα or the sum of 1Hα and 1HN SCS.

The proton assignment forms the basis for protein-nucleic acid interaction studies to identify the RNA-binding sites of Rpo4/7 through 1H chemical-shift perturbations. Proton chemical-shift values are in particular sensitive to non-covalent interactions involved in molecular recognition and thus serve as sensitive reporters. Also, the investigation of the molecular dynamics becomes accessible, in the presence and absence of nucleotides, through 15N R1ρ and R2' relaxation-rate constants that, once protons are assigned, are measured most efficiently in a series of hNH fingerprint spectra or, with higher resolution, in hCANH spectra.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/Supplementary Files.

Author Contributions

AT carried out protein syntheses and analyses, and generated NMR samples with support of DK. AT, with the help of TW and MS, conducted the NMR experiments and analyzed the data. PG extended FLYA capabilities and supported FLYA calculations carried out by TW. AT wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. TW, AB, and BM designed and supervised the study. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dina Grohmann (University of Regensburg, Germany) for providing plasmids and helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the French ANR (ANR-14-CE09-0024B), the LABEX ECOFECT (ANR-11-LABX-0048) within the Université de Lyon program Investissements d'Avenir (ANR-11-IDEX-0007), by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 200020_159707), and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement n° 741863, FASTER). TW acknowledges support from the ETH Career SEED-69 16-1 and the ETH Research Grant ETH-43 17-2.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2019.00100/full#supplementary-material

References

- Andreas L. B., Le Marchand T., Jaudzems K., Pintacuda G. (2015). High-resolution proton-detected NMR of proteins at very fast MAS. J. Magn. Reson. 253, 36–49. 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus M., Geurts D. G., Hediger S., Meier B. H. (1996). Efficient15N−13C polarization transfer by adiabatic-passage hartmann–hahn cross polarization. J. Magn. Reson. Series A 118, 140–144. 10.1006/jmra.1996.0022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet-Massin E., Pell A. J., Retel J. S., Andreas L. B., Jaudzems K., Franks W. T., et al. (2014). Rapid proton-detected NMR assignment for proteins with fast magic angle spinning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12489–12497. 10.1021/ja507382j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böckmann A., Gardiennet C., Verel R., Hunkeler A., Loquet A., Pintacuda G., et al. (2009). Characterization of different water pools in solid-state NMR protein samples. J. Biomol. NMR 45, 319–327. 10.1007/s10858-009-9374-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougault C., Ayala I., Vollmer W., Simorre J.-P., Schanda P. (2019). Studying intact bacterial peptidoglycan by proton-detected NMR spectroscopy at 100 kHz MAS frequency. J. Struct. Biol. 206, 66–72. 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann D., Klose D., Klare J. P., Kay C. W. M., Steinhoff H.-J., Werner F. (2010). RNA-binding to archaeal RNA polymerase subunits F/E: A DEER and FRET Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5954–5955. 10.1021/ja101663d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann D., Werner F. (2010). Hold On! RNA polymerase interactions with the nascent RNA modulate transcription elongation and termination. RNA Biol. 7, 310–315. 10.4161/rna.7.3.11912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann D., Werner F. (2011). Cycling through transcription with the RNA polymerase F/E (RPB4/7) complex: structure, function and evolution of archaeal RNA polymerase. Res. Microbiol. 162, 10–18. 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güntert P., Buchner L. (2015). Combined automated NOE assignment and structure calculation with CYANA. J. Biomol. NMR 62, 453–471. 10.1007/s10858-015-9924-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantsche M., Cramer P. (2016). The structural basis of transcription: 10 years after the nobel prize in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15972–15981. 10.1002/anie.201608066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger S., Meier B. H., Ernst R. R. (1995). Adiabatic passage Hartmann-Hahn cross polarization in NMR under magic angle sample spinning. Chem. Phys. Lett. 240, 449–456. 10.1016/0009-2614(95)00505-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983). Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637. 10.1002/bip.360221211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose D., Klare J. P., Grohmann D., Kay C. W. M., Werner F., Steinhoff H.-J. (2012). Simulation vs. reality: a comparison of in silico distance predictions with DEER and FRET measurements. PLoS ONE 7:e39492. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser R., Dasari M., Hiller M., Higman V., Fink U., Lopez del Amo J.-M., et al. (2011). Proton-detected solid-state NMR spectroscopy of fibrillar and membrane proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 4508–4512. 10.1002/anie.201008244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meka H. (2005). Crystal structure and RNA binding of the Rpb4/Rpb7 subunits of human RNA polymerase II. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6435–6444. 10.1093/nar/gki945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzel S., Smith A. A., Agarwal V., Hunkeler A., Org M.-L., Samoson A., et al. (2015). Protein resonance assignment at MAS frequencies approaching 100 kHz: a quantitative comparison of J-coupling and dipolar-coupling-based transfer methods. J. Biomol. NMR 63, 165–186. 10.1007/s10858-015-9975-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury S., Bernecky C., Cramer P. (2015). Structural basis of transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 129–143. 10.1038/nrm3952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E., Gath J., Habenstein B., Ravotti F., Székely K., Huber M., et al. (2013). Automated solid-state NMR resonance assignment of protein microcrystals and amyloids. J. Biomol. NMR 56, 243–254. 10.1007/s10858-013-9742-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E., Güntert P. (2012). A new algorithm for reliable and general NMR resonance assignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12817–12829. 10.1021/ja305091n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubeis T., Le Marchand T., Andreas L. B., Pintacuda G. (2018). 1H magic-angle spinning NMR evolves as a powerful new tool for membrane proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 287, 140–152. 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz A., Wasmer C., Habenstein B., Verel R., Greenwald J., Riek R., et al. (2010). Protocols for the sequential solid-state NMR spectroscopic assignment of a uniformly labeled 25 kDa protein: HET-s(1-227). Chem. Eur. J. Chem. Bio. 11, 1543–1551. 10.1002/cbic.201000124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Delaglio F., Cornilescu G., Bax A. (2009). TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 44, 213–223. 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spera S., Bax A. (1991). Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and C.alpha. and C.beta. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 5490–5492. 10.1021/ja00014a071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T. J., Fogh R. H., Boucher W., Higman V. A., Eisenmenger F., Bardiaux B., et al. (2011). A software framework for analysing solid-state MAS NMR data. J Biomol NMR 51, 437–447. 10.1007/s10858-011-9569-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöppler D., Macpherson A., Smith-Penzel S., Basse N., Lecomte F., Deboves H., et al. (2018). Insight into small molecule binding to the neonatal Fc receptor by X-ray crystallography and 100 kHz magic-angle-spinning NMR. PLoS Biol. 16:e2006192. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struppe J., Quinn C. M., Lu M., Wang M., Hou G., Lu X., et al. (2017). Expanding the horizons for structural analysis of fully protonated protein assemblies by NMR spectroscopy at MAS frequencies above 100 kHz. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 87, 117–125. 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W. (2005). Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegoshi K., Nakamura S., Terao T. (2003). 13C−1H dipolar-driven 13C−13C recoupling without 13C rf irradiation in nuclear magnetic resonance of rotating solids. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 2325–2341. 10.1063/1.1534105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terrific Broth (2006). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2006:pdb.rec8620. 10.1101/pdb.rec862026631124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todone F., Brick P., Werner F., Weinzierl R. O., Onesti S. (2001). Structure of an archaeal homolog of the eukaryotic RNA polymerase II RPB4/RPB7 complex. Mol. Cell 8, 1137–1143. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00379-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Újvári A., Luse D. S. (2006). RNA emerging from the active site of RNA polymerase II interacts with the Rpb7 subunit. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 49–54. 10.1038/nsmb1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verel R., Ernst M., Meier B. H. (2001). Adiabatic dipolar recoupling in solid-state NMR: the DREAM scheme. J. Magn. Reson. 150, 81–99. 10.1006/jmre.2001.2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. (2002). Probability-based protein secondary structure identification using combined NMR chemical-shift data. Protein Sci. 11, 852–861. 10.1110/ps.3180102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F. (2007). Structure and function of archaeal RNA polymerases. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1395–1404. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F. (2008). Structural evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases. Trends Microbiol. 16, 247–250. 10.1016/j.tim.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F., Grohmann D. (2011). Evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases in the three domains of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 85–98. 10.1038/nrmicro2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner F., Weinzierl R. O. J. (2002). A recombinant RNA polymerase II-like enzyme capable of promoter-specific transcription. Mol. Cell 10, 635–646. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00629-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfeld T., Verel R., Ernst M., Böckmann A., Meier B. H. (2012). Properties of the DREAM scheme and its optimization for application to proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 53, 103–112. 10.1007/s10858-012-9627-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. (1994). The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J Biomol NMR 4, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D., Richards F. M. (1992). The chemical shift index: a fast and simple method for the assignment of protein secondary structure through NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 31, 1647–1651. 10.1021/bi00121a010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/Supplementary Files.