Abstract

Depression is the most frequent psychiatric disorder in the world. Recent evidence has shown that stress‐induced GABAergic dysfunction in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) contributed to the pathophysiology of depression. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these pathological changes remain unclear. In this study, mice were constantly treated with the chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) till showing depression‐like behaviours expression. GABA synthesis, release and uptake in the NAc tissue were assessed by analysing the expression level of genes and proteins of Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 by qRT‐PCR and Western blotting. The miRNA/mRNA network regulating GABA was constructed based on the bioinformatics prediction software and further validated by dual‐luciferase reporter assay in vitro and qRT‐PCR in vivo, respectively. Our results showed that the expression level of GAT‐3, Gad‐1 and VGAT mRNA and protein significantly decreased in the NAc tissue from CUMS‐induced depression‐like mice than that of control mice. However, miRNA‐144‐3p, miRNA‐879‐5p, miR‐15b‐5p and miRNA‐582‐5p that directly down‐regulated the expression of Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 were increased. In the mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABA network, Gad‐1 and VGAT were directly regulated by binding seed sequence of miR‐144‐3p, and miR‐15b‐5p, miR‐879‐5p could be served negative post‐regulators by binding to the different sites of VGAT 3′‐UTR. Chronic stress causes the impaired GABA synthesis, release and uptake by up‐regulating miRNAs and down‐regulating mRNAs and proteins, which may reveal the molecular mechanisms for the decreased GABA concentrations in the NAc tissue of CUMS‐induced depression.

Keywords: depression, GABA, nucleus accumbens, stress

1. INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD), which is characterized by anhedonia or depressed mood, is a common and debilitating mood disorder in the world.1 In terms of its pathogenesis, different reports had suggested that the environmental stresses to the genetically vulnerable individuals were attributed to the depression onset or relapse.2 Moreover, the evidence from many clinical trials showed that the early life stress could influence the neural development and lead to the deficiency in brain reward and cognitive circuits, subsequently resulting in the increased risk in depression.3 However, the cellular and molecular changes induced by adverse stressor leading to defect in the cognitive and emotional circuits have not yet elucidated.

The hypothesis of GABA dysfunction has long been considered as the important pathological mechanism of depression.4, 5 The evidence from clinical trials indicated that GABAergic neurotransmission and GABA content were substantially decreased in depressed patients.6, 7, 8 Additionally, GABAergic interneuron is a leading cause of alteration in depressed patients and is beneficial to the increased of self‐focus and cogitation in depressive patients.9, 10 Our previous electrophysiological study showed that inhibitory synaptic transmission was down‐regulated in NAc GABAergic neurons in the depression model.11 The lower GABA content from presynaptic terminals in the NAc tissue may be conferred to the aetiology of chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)‐induced depression. Accumulating evidences indicate that GABA neurotransmission alterations are associated with the pathophysiology of major depression disorder. However, the molecular mechanisms about the reduced levels of GABA in major depression have yet to be fully elucidated.

This study was performed to explore the influences of chronic mild stress on the expression of different GABAergic neurons markers in the mice NAc following CUMS exposure. NAc is considered as a neural interface between motivation and action, which is characteristically disrupted in major depression disorders,12, 13, 14, 15 as well as for the depression‐related GABAergic deficits.16, 17, 18 The GABA release associated genes and proteins (Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3) in the NAc tissue were detected by qRT‐PCR and Western blotting (WB). The miRNA/mRNA networks regulating GABA were created based on the bioinformatics analysis and further validated using the method of dual‐luciferase reporter assay in vitro and qRT‐PCR in vivo, respectively. This study could reveal the pathogenic chain of the miRNA/mRNA network regulatory GABA concentrations in the NAc, which is associated with depression‐like behaviours induced by chronic mild stress.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chronic unpredicted mild stress paradigm

The CUMS paradigms experiment was conducted following the previously published protocol.19, 20 All mice were adapted to daily handling during the week after delivery prior to the experiment. Next, mice were randomly divided into control and CUMS group. The control group mice were kept uninterrupted during the treatment period. However, CUMS group mice were treated by a variety of mild stressors (Table S1). Animal ethics committee of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine approved the protocol used in this study (SDUTCM201805311223).

2.2. Behavioural assessments

The behavioural test was performed to evaluate whether the mice following exposure to different stressors presented depression‐like behaviour (anhedonia and behavioural despair). The paradigm of the sucrose preference test (SPT) and novelty suppressed feeding test (NSF) was used to assess the anhedonia behaviour.21, 22 The behavioural despair was assessed by the forced swimming test (FST) and tail suspension test (TST).19, 23 All the behavioural experiments were conducted in the sound‐proof behavioural facility with the light cycle.

2.3. Quantitative RT‐PCR

After behavioural tests, mice were euthanized and whole NAc tissue was immediately collected as previously described. qRT‐PCR was performed to determine GABAergic neuron‐associated genes and its corresponding miRNAs expression in NAc from CUMS‐induced depression‐like behaviour and control group mice. The primers used for Gad1, VGAT and GAT3, and β‐actin are listed in Table S2. The specific qRT‐PCR procedures referenced our previous study.19 The comparative cycle threshold (CT) was used to calculate the relative expression of mRNA and miRNA. All samples were prepared in triplicate.

2.4. Western blot analyses

Western blot analyses were performed using standard methods.24 The primary antibodies were used as follows: VGAT (A3129, ABclonal Technology), Gad‐1 (ab26116, Abcam), GAT‐3 (AB1574, Minipore) and β‐actin (AC004, ABclonal Technology). The protein signals were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. The optical densities of each band relative to measured values of β‐actin bands were determined using Image‐J software.

2.5. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

The potential target genes of miRNAs were predicted with the use of a bioinformatics database (TargetScan, RNA22, and miRDB). The wild and site‐directed mutation of the detected miRNA‐targeting site in mRNAs 3′‐UTR vector (primer sequences in Table S3) was constructed by following previous protocol.19 For the reporter assay, cells were seeded into 24‐well plates one day before transfection. The generated luciferase reporter plasmids, along with the miRNAs mimics or miR‐negative control (miR‐NC), were transfected into cells with the use of Lipofectamine 2000 and then subjected to the dual‐luciferase reporter assay (Promega) for the measurement of the luciferase activity after 48 hours of transfection. Each experiment was performed in the triplicates. The relative rate of firefly luciferase activity to Renilla luciferase activity was calculated.

2.6. Statistical analyses

All data were expressed as means ± the SEM. The differences between groups were analysed using two‐tail Student's t test and ANOVA P values < .05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The behavioural responses to CUMS

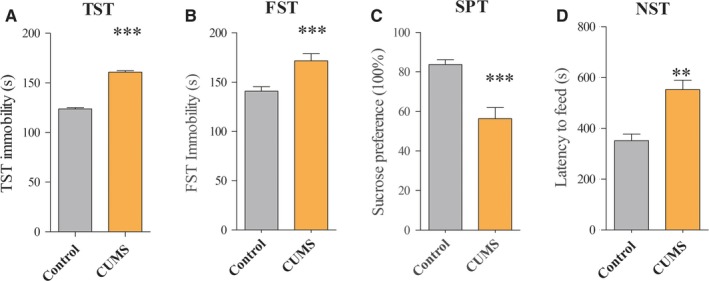

The depressive behaviours of CUMS‐treated mice were assessed by TST, FST, SPT and NST. Compared to control group, mice exposed to CUMS displayed significant increase in immobility time by TST (123.77 ± 1.39 vs 160.68 ± 1.66, P < .001; Figure 1A) and FST (140.77 ± 1.34 vs 171.51 ± 2.1, P < .001; Figure 1B). Furthermore, mice exposed to CUMS exhibited significantly lower sucrose preference (83.74 ± 0.68 vs 56.39 ± 1.6, P < .001; Figure 1C) and increased the feed latency time (351.3 ± 7.5 vs 555.2 ± 10.76, P < .01; Figure 1D) compared to control. Our data indicate that chronic mild stress can induce depression‐like behaviours.

Figure 1.

Chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)‐induced depression‐like mice. Following exposure to different stressors for five weeks, the behaviour tests showed the significant decreases significantly increased immobility time in TST (A) and FST (B), as well as exhibited reduced sucrose preference (C) and increased the feed latency in the NST (D) between controls and CUMS‐induced depression‐like mice. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 10‐14 per group, **P < .01, *** P < .001

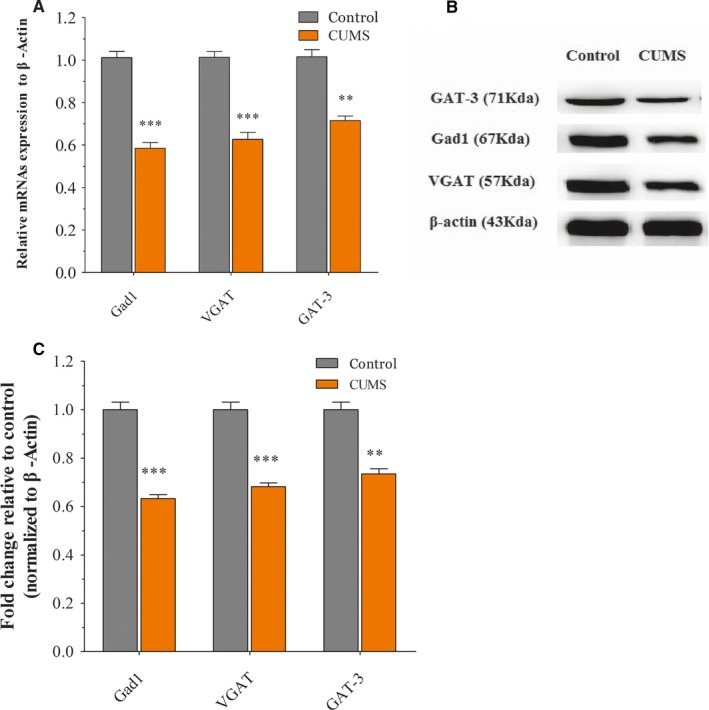

3.2. GABA synthesis, release and uptake associated genes expression

In CUMS‐induced depression‐like group, the Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 mRNA expression in the NAc tissue were significantly decreased than that of control mice (both P < .01; Figure 2A). Furthermore, the level of Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 protein has been illustrated in Figure 2B and 2C. The expression level of Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 proteins was also significantly decreased compared to control mice. There was a significant statistical difference among Gad‐1, VGAT and GAT‐3 proteins expression in the NAc tissue between two groups (both P < .01).

Figure 2.

Chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) exposures decrease GABAergic neuron‐associated gene/protein expression level in the NAc tissue. Mice were exposed to CUMS for consecutive five weeks and received behavioural tests. Then, the levels of GABAergic neuron‐associated genes in NAc were determined by qRT‐PCR. A, The relative levels of Gad1, VGAT and GTA3 genes expression in NAc relative to control. B, Representative Western blot images of Gad1, VGAT and GTA3 were shown. C, Statistical analysis of each band relative to measured values of β‐actin bands. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. n = 8‐10 per group, **P < .01, ***P < .001

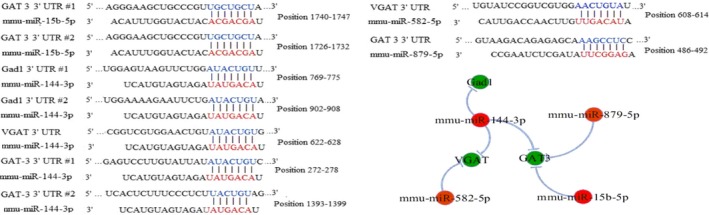

3.3. The mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic neurons network

Three miRNA targeted‐gene databases (miRDB, RNA22 and TargetScan) were used to predict the VGAT, GAT‐3 and Gad‐1 mRNAs. The 3′‐UTRs of Gad1 (two areas), VGAT (one area) and GAT‐3 (two areas) were targeted by miR‐144‐3p. The 3′‐UTRs of GAT‐3 (two areas) were targeted by miR‐15b‐5p. The 3′‐UTRs of GAT‐3 (one area) were targeted miR‐879‐5p. The 3′UTRs of VGAT (one area) were targeted by miR‐582‐5p (Figure 3). Through bioinformatics analysis, we successfully constructed an epigenetic regulatory network for GABA neuron function.

Figure 3.

The interaction between mRNAs and miRNAs. miRNAs targeted to mRNAs that encode Gad1, VGAT and GAT‐3 were predicted by using three miRNAs target prediction databases, in which the principle of miRNAs target prediction includes seed match, conservation, free energy and site accessibility. The interactive networks of miRNAs and mRNAs associated with GABA release and uptake are made by using Cytoscape software. Green symbols denote mRNAs that are actually down‐regulated in the NAc tissue. Red symbols denote miRNAs. Their negative regulation of mRNAs by miRNAs is represented by light blue line

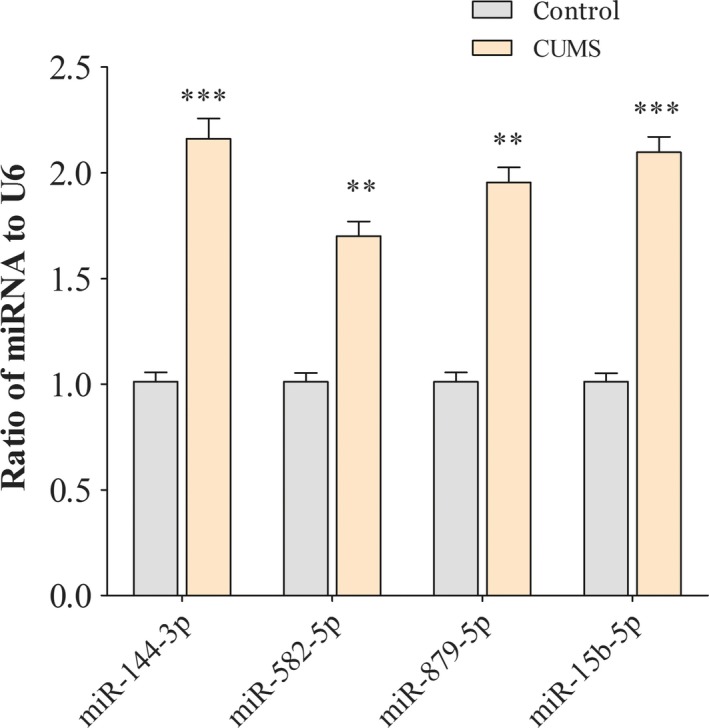

3.4. miRNA‐associated GABA were rise in NAc of CUMS depression mice

In order to verify the regulatory network, we quantified four miRNAs among the two groups. Our results showed that levels of miRNAs were significantly increased in the NAc tissue from the CUMS‐induced depression‐like mice than that of control mice (both P < .01, Figure 4). The regulatory relationships between the up‐regulated miRNAs and down‐regulated GAT‐3 Gad1 and VGAT mRNAs were presented in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

miRNAs of regulating genes associated GABA tone were increased in the NAc tissue of chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) depression‐like mice. qRT‐PCR was used to test the relative expression of miR‐144‐3p, miR‐15b‐5p, miR‐879‐5p and miR‐582‐5p from the controls and CUMS‐induced depression‐like behaviour mice. The relative values for control mice were normalized to be one. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 10‐14 per group, **P < .01, *** P < .001

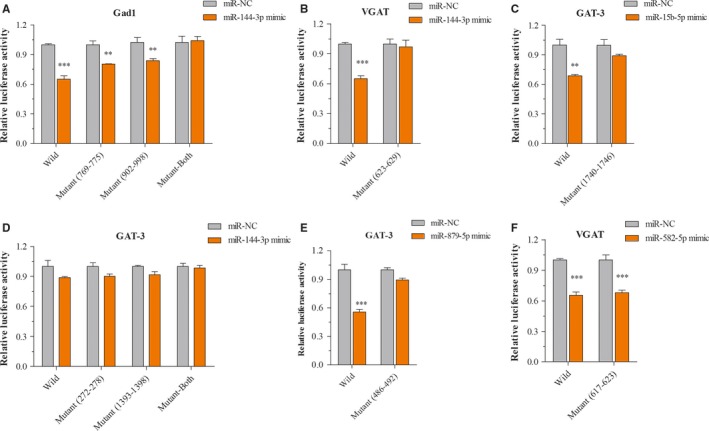

3.5. Verification of mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic neurons network in vitro

Compared to the negative control miRNAs, the miR‐144‐3p (Figure 5A) mimic significantly decreased the luciferase activity by bearing the wild or two separate binding regions mutant in 3′‐UTR of Gad1 (769‐775 and 902‐908). While this suppressive effect was abolished by both mutations in the binding site. Interestingly, miR‐144‐3p also directly regulated VGAT mRNA expression (Figure 5B). Unfortunately, there was no direct interaction between miR‐144‐3p and GAT‐3 (Figure 5D). miR‐15b‐5p and miR‐879‐5p worked as regulators by combing with 3′‐UTR of VGAT mRNA (Figure 5C and 5). The luciferase activity of the VGAT mRNA 3′‐UTR wild‐type was significantly diminished approximately 35% with the introduction of miR‐582‐5p (Figure 6F), while the mutant reporter was able to maintain this suppression effect rather than revising it.

Figure 5.

Experimental validation miRNAs targeting genes related to GABA tone. A‐D, The luciferase reporter assay verification association between miR‐144‐3p or miR‐15b‐5p mimic or NC and 3′‐UTR of Gad1, VGAT and GAT‐3 mRNAs. E, The luciferase reporter assay verification association between 3′‐UTR of GAT‐3 mRNA and miR‐879‐5p mimic or negative control. F, The luciferase reporter assay verification association between 3′‐UTR of VGAT mRNA and miR‐582‐5p mimic or negative control. **P < .01, ***P < .001

Figure 6.

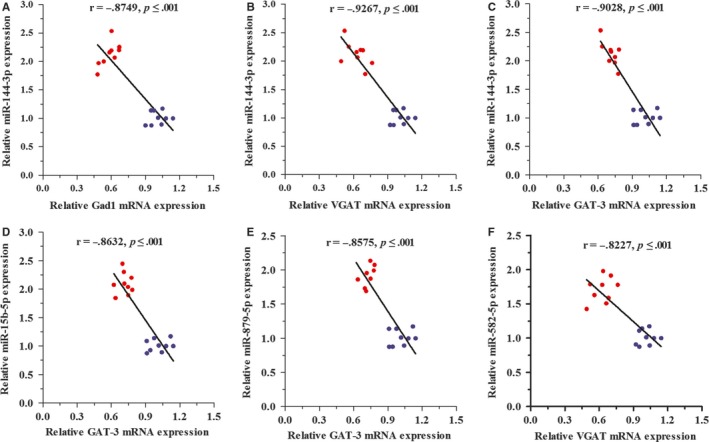

Correlation between miRNAs and their target mRNAs expression in the NAc tissue. The relationships between miRNAs and its corresponding target prediction were assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficients. A, shows the correlation between Gad1 mRNA and miR‐144‐3p expression (r = −.8749; P < .001). B, shows the correlation between VGAT mRNA and miR‐144‐3p (r = −.9267; P < .001). C, shows the correlation between GAT‐3 mRNA and miR‐144‐3p (r = −.9028; P < .001). D, shows the correlation between GAT‐3 mRNA and miR‐15b‐5p (r = −.8632; P < .001). E, shows the correlation between GAT‐3 mRNA and miR‐879‐5p (r = −.8575; P < .001). F, shows the correlation between VGAT mRNA and miR‐582‐5p (r = −.8227; P < .001). The data of qRT‐PCR of miRNAs and mRNAs were analysed in 10‐14 per group. Blue dots indicate congregation of the control group, and red dots indicate congregation of the depression group

3.6. Linear regression analysis of mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic neurons network

To confirm in silico prediction, we performed Pearson's correlation test of mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic neurons network. The linear regression analysis showed that miR‐144‐3p was negatively correlated with the expression of VGAT, Gad1 and GAT‐3 mRNAs in the NAc tissue (Figure 6A‐C). Additionally, there was also a negative correlation between miR‐15b‐5p, miR‐879‐5p and GAT‐3 mRNA expression between the two groups (Figure 6D‐E). While the expression of miR‐582‐5p significantly correlated with VGAT mRNA expression (Figure 6F).

4. DISCUSSION

Our previous studies have highlighted the distorted dynamics of neural transmission at the synaptic end of maladapted GABAergic system in the limbic system and been ascribed as the common denominator of major depression.11, 25 Especially, GABA releases and terminals were significantly decreased in the NAc tissue from the CUMS‐induced depression model (Figure S1). This impairment was caused by the aberrantly expressed level of VGAT, GAT‐3 and Gad‐1 mRNAs or proteins; therefore, it decreased GABA synthesis, release and uptake (Figure 2). In addition, miR‐15b‐5p, miR‐144‐3p and miR‐879‐5p, which were predicted to bind the 3′‐UTR of VGAT and Gad‐1 mRNAs (Figure 3), were significantly up‐regulated (Figure 4). The mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic tone network was assessed by dual‐luciferase assay in vitro (Figure 5) and qRT‐PCR in vivo (Figure 6), respectively.

Recently, several studies have shown that GABA tone substantially decreased in depressive patients or animal model.6, 26, 27, 28 GABAergic neurons dysfunction may be as the primary factor for the depression prognosis and pathogenesis.29, 30, 31 Thus, the understanding of molecular and epigenetic mechanisms underlying GABAergic neuron impairment in depression will be useful for the development of novel therapeutics.

In the current study, we investigated the GABAergic marker expression in the NAc to reveal molecular mechanisms underlying reduced GABA release. GABA is synthesized by Gad1/2. While Gad1 is mainly responsible for the GABA synthesis in the brain.32 The VGAT biological function was mainly involved in GABA uptake into synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic vesicular membranes.33 Furthermore, GABA transporter proteins can either be expressed on neurons or glial cells, which can mediate uptake of GABA from the synaptic cleft.34 The consistent results from our study suggested that GABA‐associated mRNAs and proteins expression were decreased in CUMS‐induced depression mice. The decreased level of Gad1 and VGAT expression has already been reported in either depressed patients or depression animal model,35, 36, 37 which are in line with our observations. Interestingly, the decrease GAT3‐expression subsequently decreased GABA uptake might be served as an impaired glial cell indication for depression.38 Our finding proved that the production, release and re‐uptake contribute to GABA dysfunction in depression.

miRNAs are a negative regulator of translation by binding to mRNAs 3′‐UTR.39 Emerging evidence suggested that miRNAs might play the key role in regulating the process of neurotrophin, serotonergic signalling and synaptic plasticity process.40, 41, 42, 43 Our results showed that chronic stress could up‐regulate the levels of miR‐15b‐5p, miR‐144‐3p and miR‐879‐5p expression (Figures 3, 4) as well as down‐regulate the expression of Gad1, VGAT and GAT‐3 genes and proteins, which impaired GABA tone. We validated mRNA/miRNA regulatory GABAergic neurons network by dual‐luciferase assay and qRT‐PCR in vitro or vivo, respectively (Figures 5, 6). At present, the role of miR‐144‐3p in the depressive disorders remains unclear. However, there are a few biological mechanisms that can endorse our finding. miR‐144‐3p has enriched expression and in the brain, as well as in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells and tissues.44 Many studies have suggested that miR‐144‐3p was involved in the response to stress, ageing diseases and mood stabilizer treatment.19, 45, 46 In addition, miR‐144‐3p can regulate ataxin 1 (ATXN1) mRNA expression in human cells, and a search of the Genetic Association Database shows that ATXN1 is associated with mental disorders.47 miR‐144‐3p‐targeted genes includes Wnt/β‐catenin, Nrf2 and MAKP signalling pathways,48, 49, 50 which have been verified in the physiology of depression.

Our study suggested the potential efficient connection between GABAergic pathway and miR‐144‐3p and miR‐15a/b, which share the same seed region (nucleotides 2‐8) of AGCAGCA, and as such are known as the miR‐15 family. This miRNA family also can target the 3’ UTR of BDNF, cholinergic receptor, muscarinic 1 and methyl‐CpG binding protein 1.51, 52 All of these targetings have been confirmed in the process of depression pathophysiological mechanism.53 These data provided evidence that the miR‐15 family played an important role in the pathogenesis of depression by mediating GABA release and uptake.

In summary, chronic stress leads to the impaired GABAergic deficit by increased miRNAs and corresponding decreased mRNAs and proteins, which reveals sub‐cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying GABAergic dysfunction in the nucleus accumbens of CUMS‐induced depression.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no competing interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

K Ma, HX Zhang, HJ Zhang and XC Han contributed to experiments and data analyses. Baloch Z and SJ Wang contributed to the project design and paper writing.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This project was granted by Scientific Innovation Team of Shandong University of TCM, National Natural Science Foundation of China (81903948), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2019BH027), Shandong Province University Scientific Research Project (J18KZ014) and Shandong Medical Health Technology Development Plan Project (2018WS203).

Ma K, Zhang H, Wang S, et al. The molecular mechanism underlying GABAergic dysfunction in nucleus accumbens of depression‐like behaviours in mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:7021–7028. 10.1111/jcmm.14596

Shijun Wang and Zulqarnain Baloch are contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Shijun Wang, Email: pathology@163.com.

Zulqarnain Baloch, Email: znbalooch@yahoo.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

REFERENCES

- 1. Malinow R. Depression: ketamine steps out of the darkness. Nature. 2016;533:477‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Romeo B, Choucha W, Fossati P, Rotge JY. Meta‐analysis of central and peripheral gamma‐aminobutyric acid levels in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience. 2017;42:160228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saleh A, Potter GG, McQuoid DR, et al. Effects of early life stress on depression, cognitive performance and brain morphology. Psychol Med. 2017;47:171‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emrich HM, Zerssen D, Kissling W, Möller H‐J, Windorfer A. Effect of sodium valproate on mania. The GABA‐hypothesis of affective disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1980;229:1‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luscher B, Shen Q, Sahir N. The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:383‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, Meyers N, Shen J, Drevets WC. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma‐aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:193‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bianchi L, Della Corte L, Tipton KF. Simultaneous determination of basal and evoked output levels of aspartate, glutamate, taurine and 4‐aminobutyric acid during microdialysis and from superfused brain slices. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1999;723:47‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, et al. Subtype‐specific alterations of gamma‐aminobutyric acid and glutamate in patients with major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:705‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Northoff G, Sibille E. Why are cortical GABA neurons relevant to internal focus in depression? A cross‐level model linking cellular, biochemical and neural network findings. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:966‐977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghosal S, Hare B, Duman RS. Prefrontal cortex GABAergic deficits and circuit dysfunction in the pathophysiology and treatment of chronic stress and depression. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2017;14:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu Z, Wang G, Ma K, Cui S, Wang JH. GABAergic neurons in nucleus accumbens are correlated to resilience and vulnerability to chronic stress for major depression. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35933‐35945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Francis TC, Lobo MK. Emerging Role for nucleus accumbens medium spiny neuron subtypes in depression. Biol Psychiat. 2017;81:645‐653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McEwen BS, Bowles NP, Gray JD, et al. Mechanisms of stress in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1353‐1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Francis TC, Chandra R, Friend DM, et al. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neuron subtypes mediate depression‐related outcomes to social defeat stress. Biol Psychiat. 2015;77:212‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heshmati M, Aleyasin H, Menard C, et al. Cell‐type‐specific role for nucleus accumbens neuroligin‐2 in depression and stress susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:1111‐1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shirayama Y, Chaki S. Neurochemistry of the nucleus accumbens and its relevance to depression and antidepressant action in rodents. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:277‐291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. You IJ, Jung YH, Kim MJ, et al. Alterations in the emotional and memory behavioral phenotypes of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1‐deficient mice are mediated by changes in expression of 5‐HT(1)A, GABA(A), and NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1034‐1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression: an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:63‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma K, Guo L, Xu A, Cui S, Wang JH. Molecular Mechanism for Stress‐Induced Depression Assessed by Sequencing miRNA and mRNA in Medial Prefrontal Cortex. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu A, Cui S, Wang JH. Incoordination among subcellular compartments is associated with depression‐like behavior induced by chronic mild stress. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;19(5):pyv122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tang J, Xue W, Xia B, et al. Involvement of normalized NMDA receptor and mTOR‐related signaling in rapid antidepressant effects of Yueju and ketamine on chronically stressed mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chi X, Wang S, Baloch Z, et al. Research progress on classical traditional Chinese medicine formula lily bulb and rehmannia decoction in the treatment of depression. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seo JS, Wei J, Qin L, Kim Y, Yan Z, Greengard P. Cellular and molecular basis for stress‐induced depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:1440‐1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Z, Wang S, Li L, Huang Z, Ma K. Anti‐inflammatory effect of IL‐37‐producing T‐cell population in DSS‐induced chronic inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun X, Song Z, Si Y, Wang JH. microRNA and mRNA profiles in ventral tegmental area relevant to stress‐induced depression and resilience. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;86:150‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Croarkin PE, Levinson AJ, Daskalakis ZJ. Evidence for GABAergic inhibitory deficits in major depressive disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:818‐825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Plante DT, Jensen JE, Schoerning L, Winkelman JW. Reduced gamma‐aminobutyric acid in occipital and anterior cingulate cortices in primary insomnia: a link to major depressive disorder? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1548‐1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Torrey EF, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Bartko JJ, Meador‐Woodruff JH, Knable MB. Neurochemical markers for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression in postmortem brains. Biol Psychiat. 2005;57:252‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adermark L, Soderpalm B, Burkhardt JM. Brain region specific modulation of ethanol‐induced depression of GABAergic neurons in the brain reward system by the nicotine receptor antagonist mecamylamine. Alcohol. 2014;48:455‐461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tang ZQ, Liu YW, Shi W, et al. Activation of synaptic group II metabotropic glutamate receptors induces long‐term depression at GABAergic synapses in CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:15964‐15977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maciag D, Hughes J, O'Dwyer G, et al. Reduced density of calbindin immunoreactive GABAergic neurons in the occipital cortex in major depression: relevance to neuroimaging studies. Biol Psychiat. 2010;67:465‐470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zik M, Arazi T, Snedden WA, Fromm H. Two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase in Arabidopsis are regulated by calcium/calmodulin and differ in organ distribution. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:967‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chaudhry FA, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, et al. The vesicular GABA transporter, VGAT, localizes to synaptic vesicles in sets of glycinergic as well as GABAergic neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9733‐9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rowley NM, Madsen KK, Schousboe A, Steve WH. Glutamate and GABA synthesis, release, transport and metabolism as targets for seizure control. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:546‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karolewicz B, Maciag D, O'Dwyer G, Stockmeier CA, Feyissa AM, Rajkowska G. Reduced level of glutamic acid decarboxylase‐67 kDa in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:411‐420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sibille E, Morris HM, Kota RS, Lewis DA. GABA‐related transcripts in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:721‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Juge N, Omote H, Moriyama Y. Vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) transports beta‐alanine. J Neurochem. 2013;127:482‐486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rial D, Lemos C, Pinheiro H, et al. Depression as a glial‐based synaptic dysfunction. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2015;9:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cao H, Zhou X, Zeng Y. Microfluidic exponential rolling circle amplification for sensitive microrna detection directly from biological samples. Sens Actuator B Chem. 2019;279:447‐457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gupta S, Verma S, Mantri S, Berman NE, Sandhir R. Targeting MicroRNAs in prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Drug Dev Res. 2015;76:397‐418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tavakolizadeh J, Roshanaei K, Salmaninejad A, et al. MicroRNAs and exosomes in depression: potential diagnostic biomarkers. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:3783‐3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Niwald M, Migdalska‐Sek M, Brzezianska‐Lasota E, Miller E. Evaluation of selected micrornas expression in remission phase of multiple sclerosis and their potential link to cognition, depression, and disability. J Mol Neurosci. 2017;63:275‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mouillet‐Richard S, Baudry A, Launay JM, Kellermann O. MicroRNAs and depression. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:272‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pienimaeki‐Roemer A, Konovalova T, Musri MM, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of platelet senescence and platelet extracellular vesicles. Transfusion. 2017;57:144‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu BB, Luo L, Liu XL, Geng D, Liu Q, Yi LT. 7‐Chlorokynurenic acid (7‐CTKA) produces rapid antidepressant‐like effects: through regulating hippocampal microRNA expressions involved in TrkB‐ERK/Akt signaling pathways in mice exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:541‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giridharan VV, Thandavarayan RA, Fries GR, et al. Newer insights into the role of miRNA a tiny genetic tool in psychiatric disorders: focus on post‐traumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiat. 2016;6:e954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Persengiev S, Kondova I, Otting N, Koeppen AH, Bontrop RE. Genome‐wide analysis of miRNA expression reveals a potential role for miR‐144 in brain aging and spinocerebellar ataxia pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(2316):e17‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lan F, Yu H, Hu M, Xia T, Yue X. miR‐144‐3p exerts anti‐tumor effects in glioblastoma by targeting c‐Met. J Neurochem. 2015;135:274‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feng Y, Li N, Ma H, Bei B, Han Y, Chen G. Undescribed phenylethyl flavones isolated from Patrinia villosa show cytoprotective properties via the modulation of the mir‐144‐3p/Nrf2 pathway. Phytochemistry. 2018;153:28‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li J, Sun P, Yue Z, Zhang D, You K, Wang J. miR‐144‐3p induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells by targeting proline‐rich protein 11 expression via the mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 2017;36:619‐626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bai M, Zhu X, Zhang Y, et al. Abnormal hippocampal BDNF and miR‐16 expression is associated with depression‐like behaviors induced by stress during early life. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu C, Teng ZQ, McQuate AL, et al. An epigenetic feedback regulatory loop involving microRNA‐195 and MBD1 governs neural stem cell differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e 51436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Di Liberto V, Frinchi M, Verdi V, et al. Anxiolytic effects of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors agonist oxotremorine in chronically stressed rats and related changes in BDNF and FGF2 levels in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:559‐573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.