Abstract

This article covers the renaissance of classical psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin and LSD plus 3,4-methylene dioxymethamphetamine (MDMA—ecstasy) in psychiatric research. These drugs were used quite extensively before they became prohibited. This ban had little impact on recreational use, but effectively stopped research and clinical treatments, which up to that point had looked very promising in several areas of psychiatry. In the past decade a number of groups have been working to re-evaluate the utility of these substances in medicine. So far highly promising preliminary data have been produced with psilocybin in anxiety, depression, smoking, alcoholism, and with MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcoholism. These findings have led to the European Medicines Agency approving psilocybin for a phase 3 study in treatment-resistant depression and the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD with MDMA. Both trials should read out in 2020, and if the results are positive we are likely to see these medicines approved for clinical practice soon afterwards.

Keywords: psychedelic, psilocybin, MDMA, depression, addiction, OCD, clinical trial

Abstract

Mettre la traduction ES

Abstract

Mettre la traduction FR

Recent published and some current psilocybin studies. Y-BOCS, Yale Behaviour in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory overdose Depression Scale – Self Report; POMS, Profile of Mood States; STAI, Spielberg State Anxiety Inventory.

Table I. Recent published and some current psilocybin studies. Y-BOCS, Yale Behaviour in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale; QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory overdose Depression Scale – Self Report; POMS, Profile of Mood States; STAI, Spielberg State Anxiety Inventory.

Introduction

Psychedelics of plant extraction such as mescaline (peyote cactus) and psilocybin (magic mushrooms) have been used for millennia in cultures all across the globe, but Western science was not introduced to them until 1897, when Arthur Heffter isolated mescaline. The real breakthrough came with the discovery of LSD in 1943 by Albert Hofmann at Sandoz as a synthetic variant of ergot alkaloids.1 Following his famous descriptions of his first exposure he persuaded Sandoz to make LSD available to researchers across the world under the trade name Delysid, and Sandoz made it freely available to those interested in researching its properties. Hofmann also identified the active component of “magic” mushrooms as psilocybin.2 This was also made available by Sandoz as Indocybin. It should be noted that psilocybin is in effect a prodrug, and is converted into the active ingredient psilocin in the body.

Research with LSD, in particular, flourished and the US government, in the form of the National Institutes of Health, is reputed to have funded over 130 grants for its study (but none since the 1967 ban). Before the ban hundreds of papers were published on LSD (and to a lesser extent psilocybin). 3 Because LSD, psilocybin, and other hallucinogens mimicked some of the symptoms of acute psychosis, particularly ego-dissolution, thought disorder, and misperceptions, it suggested the possibility that an endogenous psychotogen might cause schizophrenia. 4 It also seemed to allow access to repressed memories and emotions and so “unblock” people failing in psychotherapy. LSD appeared very safe in relation to other psychotropic agents used at that time, especially the barbiturates which were very toxic in overdose, whereas the psychedelics rarely had lasting medical effects, even after overdose. Indeed a long-term follow-up analysis of the impact of the tens of thousands of LSD administrations given in the 1950s and 1960s reported no increased level of psychiatric problems. 3 For a more detailed overview of the history of psychedelics in psychiatry see refs 3 and 5. One more negative note is the fact that some saw LSD as a potential weapon in warfare rather than as a therapeutic advance. This was seen in both the West and in communist countries who developed their own drugs when Sandoz would not supply them.

One area of particular interest was in the treatment of alcoholism. This derived from the personal psychedelic experience of Bill Wilson which led to his becoming alcohol-free, and so also led to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous. 6 Wilson’s own experience made him convinced of the value of LSD to give alcoholics insight into how they might overcome their drinking addiction. He encouraged the use of LSD in the treatment of alcoholism, and six trials were conducted before the drug was banned. These data were recently subjected to a modern meta-analysis and LSD therapy was found to be at least as efficacious a treatment as anything we currently have today. 7 Of interest to psychotherapists, Wilson also believed that LSD could give unique and immediate insights into the unconscious mind. He wrote to Jung encouraging him to explore this potential but Jung, who was approaching death at the time, didn’t seem especially enthusiastic and apparently replied to the effect that dreams were good enough!

In 1967, LSD was classified under Schedule I of the 1967 United Nations convention on drugs, and most other psychedelics, particularly psilocybin and mescaline, were also included even though there was very little evidence of harm. Schedule 1 drugs are defined as having no accepted medical use AND significant potential for harm and dependence, so despite this schedule clearly being quite unscientific for these drugs they have remained there ever since. This scheduling effectively censored research on psychedelics for over 40 years and only in the past decade have attempts been made to reverse this (see ref 8).

Other recreational drugs with therapeutic potential: MDMA and ketamine

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA—the correct chemical name for the recreational street drug ecstasy)—was quite widely used as a tool for psychotherapeutic purposes, especially couple counseling, when it was known as empathy . 9 However, once its name was changed to ecstasy and it began to be used in the rave recreational scene it was banned and therapeutic use largely stopped. Since that time the charity MAPS (the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) led by Rick Doblin has campaigned to have it restored as a medicine.

Though MDMA isn’t a psychedelic in the true sense of the word, it does have profound effects that allow people to gain insight into their psychiatric problems, and has proved especially helpful in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Several studies run by the Mithoefers have demonstrated that a couple of sessions of exposure- therapy under MDMA (usually 125 mg + a 62.5-mg top-up after 2 hours) can have powerful therapeutic effects. 10 , 11 The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have now both given their approval for multicenter studies in the USA and Europe, and if these are positive then it seems likely that MDMA will also become an approved medicine sometime in the 2020s.

We are currently conducting BIMA—the Bristol University MDMA for Alcoholism trial. This is an open trial of MDMA (two sessions given as in the PTSD trials) for patients with alcoholism. The rationale for this is that many such patients are drinking alcohol excessively to deaden painful memories of trauma. If MDMA therapy could help them overcome these memories then they might be able to stop or reduce their drinking.

Ketamine is an old established dissociative anesthetic that has in recent years been used in lower doses as an analgesic. Like psychedelics and MDMA, it is also used recreationally to produce altered states of consciousness which are psychedelic-like. When John Krystal at Yale started to use ketamine as an experimental medicine model of psychosis, he noted that people often experienced an improvement in mood once they had recovered from the trip. This led him and a colleague, Carlos Zarate, to conduct a trial in patients with resistant depression with good outcomes. A single IV dose of ketamine could produce an improvement in mood lasting up to 4 days. 12 Since then there have been many related studies conducted with ketamine. Also its active enantiomer, s-ketamine (given intranasally) has been developed commercially and may well be licensed in the near future. All forms of ketamine have to be given twice weekly to maintain their antidepressant effects. These two different forms of ketamine are both thought to act as glutamate antagonists of the NMDA receptor system. This action thought to lead to a disruption of the abnormal brain circuits that underpin depression (see below). 13

The pharmacology of psychedelics

The key target for the psychedelic drugs is the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor where they are agonists, ie, they stimulate the receptor. Most psychedelic drugs also have actions at other serotonin receptors such as the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2B receptors where again they have agonist or partial agonist activity. However these probably do not contribute to the psychedelic effects; we know that 5-HT2A receptor agonism is what produces the psychedelic effects because Franz Vollenwieder’s group has shown convincingly that these are fully blocked by the selective 5-HT2A antagonist ketanserin. 14 , 15

The modern-day resurgence of psychedelics in psychiatry

The process of resuming clinical research with psychedelics came from two parallel directions. One was the development of neuroimaging and psychopharmacological studies conducted in healthy volunteers and the second from some small exploratory clinical studies.

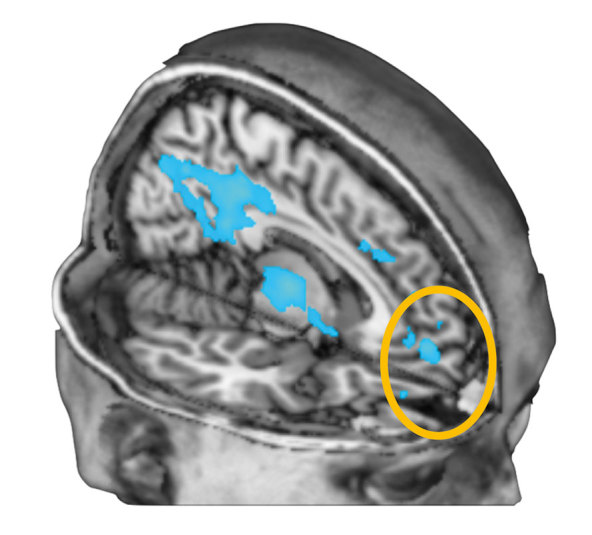

Since the 1990s several groups have begun to apply modern research methods to psychedelics with Strassman et al in the United States using DMT, and Vollenweider et al in Switzerland using psilocybin. 15 My own group started in the 2000s with psilocybin and conducted the first systematic fMRI studies with this drug. 16 The results were unexpected and surprising because we found that the main effect of psilocybin was to decrease brain blood flow and blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) activity predominantly in the default mode network (DMN) but including the subgenual cingulate cortex (Figure 1) .

Since several neuroimaging studies have found overactivity in this brain region in depression 17 , 18 and many different treatments of depression have been found to suppress activity here, 19 , 20 this finding seemed of interest for depression. Also it was relatively common for our volunteers to report improved mood and well-being after their psilocybin administration (even when the drug was given in a scanner). For these reasons we wondered if the same decreased activity in the subgenual cingulate cortex might occur after psilocybin in depressed patients and this might then elevate mood. It was this translational medicine insight, supported by earlier clinical data, that led to our MRC-funded trial in resistant depression described below.

As well as imaging studies there was also a hugely influential psychopharmacological experiment conducted by Roland Griffiths and his team at John Hopkins university in Baltimore. 21 They gave healthy non-psychiatrically ill volunteers a single 25-mg oral dose of psilocybin in a psychotherapeutic setting and followed them up for many years. A control group treated in the same way received a dose of the stimulant methylphenidate. In contrast to the methylphenidate group who had little in the way of long-term benefits, most of the psilocybin participants found the experience rewarding and insightful and many said it was one of the most significant experiences of their lives, ie, being in the top five of their life-time positive experiences. Moreover this positive outcome lasted for very many years. This was the first systematic controlled study of the use of a psychedelic to give insights and produce well-being in normal volunteers, and served as the basis on which subsequent patient studies were conducted. For example in our studies we use the same 25-mg oral dose and setting as the Griffiths work.

The first modern clinical trial of a psychedelic was by Francisco Moreno and colleagues, at the University of Arizona in 2006. 22 Nine subjects with treatment-resistant OCD were given up to three different doses of psilocybin in an open-label design. Significant reductions in OCD symptoms were observed but no clear dose effect was seen. Importantly there were no serious adverse events. The trial was reputedly stopped because of the extreme costs involved in working with a controlled drug! This is a common problem, as discussed later.

The Griffiths team at Johns Hopkins have subsequently conducted several clinical trials. The first was an open study in people trying to quit tobacco smoking. 23 Fifteen otherwise psychiatrically healthy smokers in a structured 15-week smoking cessation treatment programme were given 25 mg psilocybin three times (weeks 5, 7, and 13). Biological markers of smoking, eg, urinary cotinine level as well as smoking craving and urges, were assessed up to 6 months. Remarkably 12 of the 15 subjects became and remained smoking-free at 6 months—an extremely significant outcome. The Hopkins team have also conducted one of the two most recent studies on psilocybin for end-of-life depression and anxiety, which are discussed as a group below.

The other addiction study with psilocybin was conducted by Michael Bogenschutz and colleagues at the University of New Mexico. They gave two psilocybin sessions to 10 alcohol-dependent patients in addition to standard therapy. 24 The primary outcome was the percentage of heavy drinking days, and very significant reductions in this metric were found with no concerning adverse effects of the psilocybin.

One pilot study using psilocybin in major depressive disorder has also been published in the modern literature. 25 , 26 In this, our own open-label pilot study, we gave two doses of psilocybin (a 10-mg “test” dose and a 25-mg therapeutic dose) 1 week apart with psychological support before and after the experience to 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression who were moderately to severely depressed. In reality the participants were mostly multiply treatment-resistant (mean number of failed medications was 4.6 ± 2.6), and the illness was very long-standing (mean duration of illness 17.7 years ± 8.4 years). As serotonergic antidepressants and 5-HT2A receptor antagonist antipsychotics block the effects of psilocybin, patients were withdrawn from these before getting the psilocybin treatment. The primary outcome measure was the mean change in the participant-rated quick inventory of depressive symptoms (QIDS-SR) rating scale with follow-up was for 6 months, Highly significant improvements in depression ratings were seen at all time points with the maximal significance of effect seen at 5 weeks. The trial established feasibility and evidence of safety, but efficacy interpretations are limited by the open-label design.

All the above clinical studies suffer from the major problem of being open-label designs. This is acceptable for early stage research but a challenge for effectively proving the therapeutic efficacy of psychedelics. However, in the past couple of years a few controlled clinical trials have now been carried out. Four separate controlled studies have been published on the use of psychedelics in end-of-life anxiety and depression associated with life-threatening illness. Gasser et al 27 used LSD either a low (20 ug) or a high (200 ug) dose whereas the other three studies all used psilocybin.

Charles Grob and colleagues in California 28 gave 12 subjects (11 women) a moderate (0.2 mg/kg) dose of psilocybin and an active placebo (niacin 250 mg) in a double-blind design in which subjects acted as their own controls. All subjects had advanced cancer diagnoses and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV- defined acute stress or anxiety disorders as a result of their cancer diagnosis. The treatment was well tolerated and all 12 completed the 3-month follow up. Nonsignificant trends towards improvements in mood were observed, perhaps because of the small numbers and relatively low dose of psilocybin used.

Two larger, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trials investigating the efficacy of psilocybin in the treatment of anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer diagnoses have since been published simultaneously from two separate groups in the USA. Roland Griffiths and his John Hopkins team treated 51 patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms occasioned by life-threatening cancer diagnosis. 29 Placebo was a very low (ineffective) dose of psilocybin (1 mg or 3 mg/70 kg) compared with the much higher active treatment dose (22 mg or 30 mg/70 kg). Administration was counterbalanced with 5 weeks between sessions and 6-month follow up. The Hamilton Depression and Anxiety scales were the primary outcome measures, and showed superiority for the high dose versus the low dose at 5 weeks. The crossover high-dose group then experienced a significant improvement also. Significant associations between mystical-type experiences and enduring positive changes were also observed, as in previous research of this group. 21

In a similarly designed study Stephen Ross and colleagues at NYU gave 29 patients a single dose of 0.3 mg/kg psilocybin or 250 mg niacin as active placebo with crossover at 7 weeks. 30 The treatment was delivered safely, with no reports of serious adverse events. The group receiving psilocybin showed clinical benefits as measured by both clinician and participant rated scales that lasted for the 7 weeks prior to crossover and were also sustained approximately 8 months after dosing. The group that received niacin instead showed transient reductions that were not sustained at 7 weeks. After they crossed over to psilocybin, they also showed immediate and sustained reductions in anxiety and depression scores that were sustained at follow-up at 6 months.

As a result of these positive studies the EMA and the FDA have both given their approval for a multicenter multi-country trial of psilocybin run by the UK-based pharmaceutical company called COMPASSPathways. 31 This will involve randomization to one of three doses: 1, 10, and 25 mg given once only in patients who have failed two prior antidepressant treatments in their current episode. The study started at the beginning of 2019 and should report in 2020/21. If positive then both regulators have indicated a willingness to approve psilocybin as a medicine. In the USA the company USONA is also in the process of developing psilocybin as a medicine. Table I summarizes recent and current studies on psilocybin.

It is also important to record that other studies with different psychedelics have been conducted. I have already mentioned the LSD trial by Gasser in Switzerland, and this has led to this drug being made available for compassionate use in named patients by a few psychiatrists in that country.

A number of countries in South and Latin America allow the use of ayahuasca drink for religious and therapeutic purposes. This drink contains a mixture of plant products, one of which contains the psychedelic dimethyl tryptamine (DMT) and the other a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, harmaline. The harmaline blocks the activity of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in gut and liver, and so allows enough of the DMT in the drink to enter the brain and so have its psychedelic effects. Human neuroscience studies of ayahuasca have shown it to have similar effects to psilocybin and LSD, and several clinical trials have taken place in depressed patients. For example Osorio gave ayahuasca to 6 medication- and ayahuasca-naive participants and found significant reductions in depression, as shown by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Mongomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale up to 2 weeks after treatment. 32 Sanches et al conducted another open-label study in 17 patients and again, highly significant reductions in depressive symptoms were observed up to the 3-week end point. 33 A double-blind study has since been conducted, also with positive outcomes. 34

Current challenges and future prospects

Inspection of Table I reveals that the resurrection of psilocybin research is still in its infancy. There have been very few double-blinded studies, and total patient numbers are very low, less than 200 in all. This means we must be very cautious in making claims about the value of psychedelic therapy in psychiatry. Much more needs to be done, and the key question is how best to do this.

In the following sections I highlight what I think are the key issues that the field needs to take into consideration if this exciting yet still only promising new research area is to be properly assessed.

The first point to be made clear is that treatment with psychedelics and MDMA is a complex procedure that requires a great deal of therapists’ time and involvement. It had been suggested that this is a new era of psychiatric treatment—drug-assisted psychotherapy (or even psychotherapy-assisted drug treatment). Patients have to be properly prepared for the powerful impact of the psychedelic session, and this involves at least one dedicated session with a trained therapist (often called a guide) before the drug session. In this prep session the patient is educated about the rationale, purpose, and procedure of the treatment session.

The drug session itself is given in a room with soft ambient lighting and a comforting soundtrack (which may contribute to the therapeutic value as well). 35 There are generally two therapists present in the room (ideally one male and one female) who are there to provide reassurance, medical cover, and care. They only talk with the patient if the patient wants them to, which they generally do not. It is important to note that there is no expectation of conversation during the “trip” and no direction by either therapist of the patient’s speech or thought. It is the next day in the “integration” session that the content of the trip is discussed and interpreted and psychotherapeutic benefits derived (see ref 36 for detailed descriptions of the experiences that patients in our depression study described).

Some critics of the procedure have argued that such intensive therapist input may constitute the therapeutic process, rather than the drug itself. Others have questioned whether the drug alone without therapy might work just as well. These are fair scientific points, but the reality of the power of a trip is such that we believe to allow one without medical and therapist cover would be unethical. The argument that it is all a powerful psychotherapeutic placebo is not sustainable because of the Griffiths and Ross double-blind studies where placebo + intense psychotherapy did not work as well as psychotherapy plus the active drug.

The question of safety is important. Although the banning of psychedelics and MDMA was made on the basis of largely fictitious claims of harm, there is no doubt that the psychedelics in particular are powerful mind-altering drugs, that can leave deep negative as well as positive memories. 37 A more recent analysis of comparative experiences from, and adverse effects of, psilocybin has been produced. 38

There is also the risk of precipitating or worsening psychosis. For the latter reason we exclude anyone with a history of psychosis in themselves or in first-degree family members. So far we have also excluded patients with bipolar depression in case mania might be precipitated. With these precautions we have found adverse effects to be rare, and no-one has asked to stop the treatment. However, unlike with recreational users we found that very few of the depressed patients enjoyed the experience. 36 They found confronting their depressive thoughts and memories quite challenging, but afterwards almost all felt the experience had been worthwhile. However, we were prepared for anyone needing to be rescued from a severe bad trip by having a parenteral form of a benzodiazepine ready as escape medication. This, we have found, worked in an earlier study with LSD where one subject wanted relief. An extra safety measure held in readiness is the 5-HT2A receptor-blocking antipsychotic drug, olanzapine.

One common clinical challenge is the fact that so many patients are already on antidepressant and other drugs that block the effects of psychedelics. 5-HT2A receptor-blocking antipsychotic drugs such as quetiapine and olanzapine completely block the access of the psilocybin to the 5-HT2A receptor, so it is unable to work. 39 Also, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) desensitize these receptors and so reduce the psychedelic’s effects. 40 We found that stopping these is often necessary, but of course is associated with the risk of worsening the underlying depression and also inducing withdrawal or discontinuation reactions, so this needs to be done slowly and carefully.

The legal status of this treatment is also a challenge, as all psychedelics and MDMA are listed in the UN Conventions as Schedule 1 drugs. 41 Despite the growing evidence of efficacy and safety they are still subject to intense legal controls. This means that getting supplies is extremely difficult and time-consuming, and very expensive. I calculated that the cost of each administration of psilocybin in our first psilocybin depression study cost about £1500 and took 2 years to procure. Until these regulations are reformed, this research will thus continue to be very limited and the therapeutic utility of these remarkable drugs will take an unnecessarily long time to be properly evaluated. 42

Finally, how do these drugs work? The current thinking with psychedelics and depression is that they disrupt the dysregulated brain circuits that underpin depression. In the introduction I already mentioned the switching down of activity in the subgenual cingulate cortex by psilocybin, in common with other treatments for depression. Another interesting and related idea is that of psilocybin switching off the default mode network (DMN). For example, Berman and colleagues 43 have demonstrated that in depressed people a much greater amount of brain is active in the DMN condition than in healthy controls. This overengagement of the DMN appears to be a cause—or maybe a manifestation—of the intense self-deprecatory rumination that depressed patients experience. 43 Psychedelics significantly disrupt ongoing DMN activity. 44 So, for the duration of the trip the depressive processes are also disrupted. This in itself may give the patients a view of a depression-free world to which they can aspire after the drug treatment session. But there may be more to it than that, because the increased synaptic flexibility produced by 5-HT2A receptor stimulation in preclinical models 45 may allow the brain to reset itself into a different, depression-free, state. Another possibility shown by fMRI connectivity analysis is that psilocybin may alter the pattern of dominant connections between frontal cortex and subcortical regions such as the amygdala. 46

There is now good conceptual evidence that the antidepressant effects of psychedelics are mediated in quite a different way to those of serotonin-acting antidepressant drugs such as the SSRIs. 47 The latter seem to provide a buffer against stress by enhancing serotonin function at the 5-HT1A receptor, so making the person more resilient. In contrast we believe that the psychedelics acting via stimulation of the 5-HT2A receptor work to reset the brain processes, eg, overconnected DMN that underpins the depressive thinking and so allows the patient to work through their issues and so overcome their depression. It appears that activations of these serotonin receptors can have profound and long-lasting effects on brain function that might explain why a single dose can lead to antidepressant efficacy for weeks or months. 47 However, for most of our patients the depressed ideation began to re-emerge by 6 months. So in our ongoing study of psilocybin versus escitalopram we are giving a second psilocybin dose 3 weeks after the first to explore if more enduring activity might be produced.

MDMA works quite differently; it is a serotonin-releasing agent 48 and fMRI studies have revealed its main activity as being in the limbic system where it suppresses activity especially of amygdala and hippocampus. 49 We believe that it is this damping down of the emotional memory circuits that helps patients with PTSD relive their traumas and at the same time overcome and eventually extinguish the intense emotions that go with the memories of them. 50

We cannot finish a review of the psychological effects of psychedelics without mentioning microdosing. 51 - 53 This has become a topic of general discussion, especially in people working in the creative industries, many of whom claim to use low, ie, subpsychedelic doses, of psilocybin or LSD to aid their mental processes. Some claim that this helps with their mood and may keep depression at bay. These doses are taken regularly, usually a couple of times a week. However, since these drugs are illegal there is no way of knowing for sure what they are and what exact doses are being used. Also there are no controlled trials so the effects could all be suggestion or placebo. Still, it is pharmacologically plausible that some low-level activation of the 5-HT2A receptor from a microdose might alter brain function in a positive creative way, and research into this possibility is urgently required.

| Study author and ref | Study type and dose | Target illness | Primary outcome | Statistical significance | Placebo |

| Moreno 22 | OCD | OCD | Reduced Y-BOCS | Effects at all doses | Low dose |

| Johnson et al 23 | Open 2-3 fixed 25-mg doses | Tobacco dependence | Abstinence | 12/15 fully stopped | None |

| Bogenschutz et al 24 | Open 2-3 fixed 25-mg doses | Alcoholism | Reduced heavy drinking days | None | |

| Carhart-Harris et al 26 | Open single dose 25-mg | Resistant depression | QIDS-SR | Max at 5 weeks | None |

| Grob et al 28 | Double-blind crossover | Cancer + acute stress reactions | Beck and POMS | Niacin | |

| Griffiths et al 29 | 2016 double-blind fixed-dose 25-mg | End of life mood changes | HAM-D and HAM-A | Max at 5 weeks | Low-dose psilocybin |

| Ross et al 30 | 2016 double-blind fixed-dose 25-mg | End of life mood changes | Beck and STAI | 6 weeks | Niacin |

| Ongoing studies | |||||

| Carhart-Harris et al, unpublished | Reporting 2020 2 x 25-mg dose | Depression Psilocybin -v- escitalopram | fMRI brain measures and QIDS-SR | n/a | 1-mg dose |

| COMPASS Pathways 31 | Reporting 2020 single 1, 10, 25-mg dose | Resistant depression Multicenter European study | MADRS | n/a | 1-mg dose |

| BIMA Bristol University MDMA for Alcoholism, unpublished | MDMA 125-mg + 62.5 after 2 h | Alcoholism with significant trauma | Days of drinking | n/a | Open trial |

Acknowledgments

DJN is a consultant for COMPASSPathways and has received research support from them, MAPS, and the Beckley foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hofmann A. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann A,, Heim R,, Brack A,, et al. Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 1959;42:1557–1572. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19590420518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grinspoon L,, Bakalar J. The psychedelic drug therapies. Curr Psychiatr Ther. 1981;20:275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwig AM. Altered states of consciousness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1966;15(3):225–234. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1966.01730150001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rucker JJH,, Iliff J,, Nutt DJ. Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology. 2018;S0028-3908(17):30638–X. doi: 10.1016/12345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson B. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs TS,, Johansen PO. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:994–1002. doi: 10.1177/0269881112439253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nutt DJ,, King LA,, Nichols DE. Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(8):577–585. doi: 10.1038/nrn3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sessa B,, Nutt D. Making a medicine out of MDMA. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206:4–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mithoefer MC,, Wagner TM,, Mithoefer AT,, Jerome L,, Doblin R. The safety and efficacy of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(4):439–452. doi: 10.1177/0269881110378371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mithoefer MC,, Mithoefer AT,, Feduccia L,, et al. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;55(6):486–497. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lener MS,, Kadriu B,, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381–401. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0702-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JW,, Szczepanik J,, Brutsché N,, Park LT,, Nugent AC,, Zarate CA Jr. Default mode connectivity in major depressive disorder measured up to 10 days after ketamine administration. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(8):582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preller KH,, Burt JB,, Ji JL,, et al. Changes in global and thalamic brain connectivity in LSD-induced altered states of consciousness are attributable to the 5-HT2A receptor. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.35082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vollenweider FX,, Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen MF,, Bäbler A,, Vogel H,, Hell D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. NeuroReport. 1998;9:3897–3902. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carhart-Harris RL,, Erritzoe D,, Williams T,, et al. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2138–2143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119598109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greicius MD,, Flores BH,, Menon V,, et al. Resting-State functional connectivity in major depression: abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drevets WC,, Savitz J,, Trimble M. The Subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(8):663–681. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900013754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolwig TG. Neuroimaging and electroconvulsive therapy: a review. J ECT. 2014;30(2):138–142. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlop BW,, Mayberg HS. Neuroimaging-based biomarkers for treatment selection in major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2014;16(4):479–490. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.4/bdunlop. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths R,, Richards W,, Johnson M,, McCann U,, Jesse R. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22:621–632. doi: 10.1177/0269881108094300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno FA,, Wiegand CB,, Taitano EK,, Delgado PL. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1735–1740. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson MW,, Garcia-Romeu A,, Cosimano MP,, Griffiths RR. Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:983–992. doi: 10.1177/0269881114548296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bogenschutz MP,, Forcehimes AA,, Pommy JA,, Wilcox CE,, Barbosa P,, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carhart-Harris R.L,, Bolstridge M,, Rucker J,, et al . Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(619):627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carhart-Harris RL,, Bolstridge M,, Day CMJ,, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasser P,, Kirchner K,, Passie T. LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:57–68. doi: 10.1177/0269881114555249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grob CS,, Danforth AL,, Chopra GS,, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:71 78. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffiths RR,, Johnson MW,, Carducci MA,, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1181–1197. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross S,, Bossis A,, Guss J,, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1165–1180. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.COMPASSPathways; clinical trials. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osório F de L,, Sanches RF,, Macedo LR,, et al. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a preliminary report. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2015;37:13–20. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanches RF,, de Lima Osório F,, dos Santos RG,, et al. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a SPECT study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:77–81. doi: 10.1097/JCP.00000000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palhano-Fontes F,, Barreto D,, Onias H,, Andrade KC. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(4):655–663. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaelen M,, Giribaldi B,, Raine J,, et al. The hidden therapist: Evidence for a central role of music in psychedelic therapy. Psychopharmacology. 2017;235(2):505–519. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4820-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watts R,, Day C,, Krazanowski J,, Nutt DJ,, Carhart-Harris R. Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(5):520–564. doi: 10.1177/0022167817709585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carbonaro TM,, Bradstreet MP,, Barrett FS. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: Acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1268–1278. doi: 10.1177/0269881116662634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tyls F,, Palenicek T,, Horacek J. Psilocybin–summary of knowledge and new perspectives. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(3):342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuroscience based nomenclature – the app. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonson K. Chronic administration of serotonergic antidepressants attenuates the subjective effects of LSD in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:425–436. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nutt DJ,, King LA,, Nichols DE. Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(8):577–585. doi: 10.1038/nrn3530.Epub.2013Jun12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carhart-Harris RL,, Goodwin GM. The therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs: past, present, and future. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;11:241. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berman MG,, Peltier S,, Nee DE,, Kross E,, Deldin PJ,, Jonides J. Depression, rumination and the default network. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2011;6(5):548–555. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carhart-Harris L,, Muthukumaraswamy S,, Roseman L,, et al. Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4853–4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518377113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ly C,, Greb AC,, Cameron LP,, et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3170–3182. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carhart-Harris RL,, Roseman L,, Bolstridge M,, et al. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13282-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carhart-Harris RL,, Nutt DJ. Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31:1091 1120. doi: 10.1177/0269881117725915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green AR,, Mechan AO,, Elliott JM,, O’Shea E,, Colado MI. The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”). Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(3):463–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carhart-Harris RL,, Murphy K,, Leech R,, et al. The effects of acutely administered MDMA on spontaneous brain function in healthy volunteers measured with arterial spin labelling and BOLD resting-state functional connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(8):554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carhart-Harris RL,, Wall MB,, Erritzoe D,, et al. The effect of acutely administered MDMA on subjective and BOLD fMRI responses to favourite and worst autobiographical memories. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;17:527–540. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harman WW,, McKim RH,, Mogar RE,, Fadiman J,, Stolaroff MJ. Psychedelic agents in creative problem-solving: a pilot study. Psychol Rep. 1966;19:211–227. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1966.19.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fadiman J. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldman A. 2017 [Google Scholar]