Abstract

Rationale:

Exposure to respirable crystalline silica causes silicosis, a preventable, progressive occupational lung disease. A more rigorous occupational health standard for silica could help protect silica-exposed workers.

Objectives:

To describe trends over 29 years of silicosis surveillance in Michigan.

Methods:

Michigan law requires the reporting of silicosis. We confirmed the diagnosis of silicosis in reported cases using medical questionnaires, review of medical records, and chest radiographs. The Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) conducted enforcement inspections at the workplaces of the silicosis cases, including air monitoring for silica and evaluation of workplace medical surveillance programs.

Results:

The Michigan surveillance program identified 1,048 silicosis cases from 1988 to 2016, which decreased from 620 during 1988–1997, to 292 during 1998–2007, to 136 during 2008–2016. The cumulative incidence rate of silicosis decreased from 3.7 to 1.4 to 0.7 cases per 100,000 men 40 years of age and older in Michigan over the same three periods. African Americans had a higher cumulative incidence rate of silicosis, with 6.0 cases per 100,000 African American men 40 years of age and older in Michigan compared with 1.2 cases per 100,000 white men 40 years of age and older in Michigan. The cases identified had severe disease; 59% had progressive massive fibrosis or category 2 or 3 small opacities per B-reading classification of the chest radiograph. Seventeen percent reported ever having active tuberculosis. On spirometry, 76% of ever smokers and 72% of never smokers demonstrated either a restrictive or an obstructive pattern. Most (65%) had not applied for workers’ compensation benefits; the percentage who applied for benefits decreased from 42% to 28–16% over the three periods. Thirty-four of 55 (62%) workplace inspections found exposures above the new OSHA 50 μg/m3 respirable crystalline silica permissible exposure limit, and only 11% of inspected companies screened their workers for silicosis.

Conclusions:

Adults with confirmed cases of silicosis have advanced disease and morbidity. Most are not using workers’ compensation to pay for their care. The new OSHA silica standard, which lowers the permissible exposure limit for silica and requires medical monitoring to identify workers with silicosis, will help reduce the burden of silica exposure. It is critical for pulmonologists to be vigilant to recognize and manage this preventable occupational lung disease.

Keywords: silicosis, silica, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tuberculosis, surveillance

Silicosis is an irreversible occupational lung disease caused by inhalation of crystalline silica particles. The disease takes three forms: acute, accelerated, and chronic (1–4). Traditional industries and activities in which silica exposures occur include foundries, sandblasting, mining, tunneling, ceramic products manufacturing, and construction. Emerging industries with silica exposure include manufacturing and installation of engineered stone countertops, oil and gas hydraulic fracturing, and highway repair (5–8). Silicosis and silica exposure are risk factors for tuberculosis (TB) (9), chronic renal disease, connective tissue disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1–4, 10–12). Silica was classified as a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1997, and this classification was reaffirmed by IARC in 2012 (13, 14).

The State of Michigan has received funding from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) since 1988 for the development and continuation of a silicosis surveillance and workplace intervention program. NIOSH has funded up to seven states over this time, but only Michigan has tracked cases of silicosis for the entire 29 years. Furthermore, Michigan has been the only state where the surveillance program is part of a regulatory program to conduct enforcement inspections at the workplaces of the silicosis index cases.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) sets workplace limits of exposure, termed permissible exposure limits (PEL), which is an 8-hour time-weighted average exposure not to be exceeded during the workday. NIOSH, the research arm of OSHA, recommends exposure limits, termed recommended exposure limits (REL), which OSHA considers for adoption as regulations. In 2018, OSHA implemented a new silica standard that lowers the PEL from 100 μg/m3 to the NIOSH REL of 50 μg/m3 for respirable silica and requires medical monitoring of silica-exposed workers. With the new standard, we expect increased recognition of individuals with silicosis and other silica-related conditions. This report updates the results of the Michigan silicosis surveillance system last published in 1997 (15).

Methods

Case Identification

Case identification relied on hospital discharge records, healthcare provider reports, death certificates, and workers’ compensation claims. An additional source for identifying cases included referrals of coworkers by the index case. The authority to identify and collect information on these cases is based on the Michigan Public Health Code (Article 368, Part 56, P.A. 1978, as amended), which requires hospitals, clinics, healthcare providers, and employers to report known or suspected cases of occupational diseases to the state within 10 days. All cases, regardless of the reporting source, required confirmation of the diagnosis.

Case Definition

The definition for a confirmed case of silicosis required the following: 1) a history of exposure to airborne silica dust and 2) either or both of a chest radiograph or other imaging technique interpreted as consistent with silicosis or pathology results characteristic of silicosis.

Case Confirmation

A standardized telephone-administered medical questionnaire to interview the subject or next of kin was used to collect the following information: demographics (sex, race, ethnicity, age); cigarette use (smoked five or more packs of cigarettes or 12 ounces of tobacco in a lifetime); lifetime work history to verify employment in a silica-using industry, including sandblasting; whether applied for workers’ compensation; and TB history. Medical records or death certificates that indicated employment in a known silica-using industry were also used, when available, to confirm occupational exposure to silica.

Medical records from hospitals or doctors, including pathology reports from lung biopsies, chest radiograph reports, high-resolution computed tomography reports, chest radiograph images, and pulmonary function tests, were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis of silicosis. Chest radiographs were classified according to the International Labor Office (ILO) criteria for pneumoconioses by a single NIOSH-certified B reader (16). A B reader is a physician certified by NIOSH to classify a chest radiograph for pneumoconiosis. The ILO classification system is used internationally to standardize reporting of the radiographic changes seen with different pneumoconioses. Per the ILO criteria, progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) was defined as having at least one large opacity whose longest dimension exceeded 10 mm.

We requested spirometry results from hospitals, pulmonary laboratories, physician offices, and clinics after the silicosis case medical questionnaire was completed. Obstruction was defined as having an FEV1 percent predicted less than 80% and FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.70; restriction was defined as having an FVC percent predicted less than 80% and FEV1/FVC ratio greater than or equal to 0.70. We used the predicted values of the reporting entity; we did not attempt to standardize results from the different sources with a single set of predicted values. It should be noted that we only had spirometry results, so we only reported that there was obstruction or a restrictive pattern, because we did not have values for total lung capacity or diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

A National Death Index query periodically checked the vital status of confirmed cases. We obtained death certificates for the deceased cases and abstracted cause of death, contributing cause of death, and usual occupation and industry. If a subject died outside of Michigan, we used the coded National Death Index cause of death.

Michigan OSHA conducted enforcement inspections at the workplaces of the confirmed silicosis cases. Reports from the inspections included results of air monitoring for respirable crystalline silica and assessment of medical monitoring programs.

We divided the 29 years of surveillance data into three periods to allow sufficient numbers within each period to examine trends over time: 1988–1997 (10 yr), 1998–2007 (10 yr), and 2008–2016 (9 yr). Frequencies and cross-tabulations were calculated using Microsoft Access software. We obtained the 1990, 2000, and 2010 Michigan census data for men 40 years of age and older for the denominators for the cumulative incidence rates by time period (1988–1997, 1998–2007, and 2008–2016) and race (white, African American). We used the midpoint census 2000 data for the denominator for the cumulative incidence rate for all years combined. The cumulative incidence rate ratio of silicosis by race was calculated using OpenEpi (www.openepi.com). The Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program (Biomedical and Health Institutional Review Board) approved this investigation with waiver of informed consent.

Results

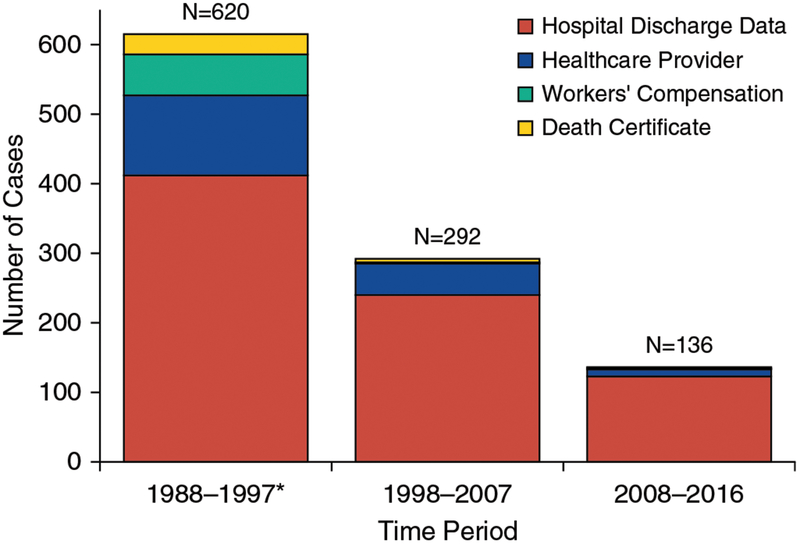

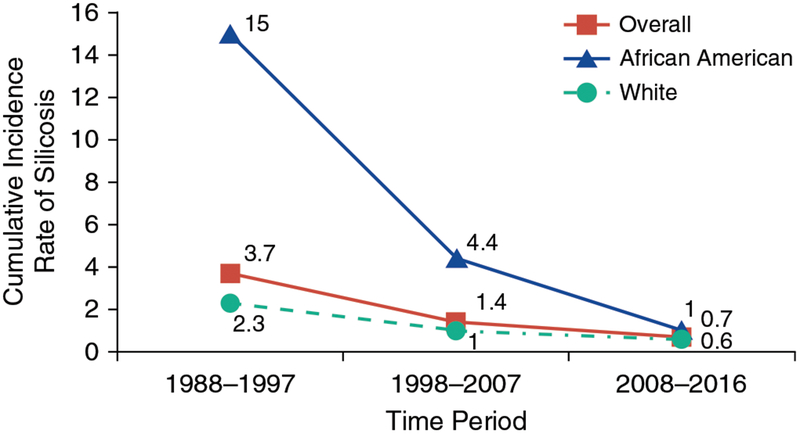

From 1988 to 2016, 1,048 silicosis cases were confirmed in the State of Michigan: 620 silicosis cases from 1988 to 1997, 292 cases from 1998 to 2007, and 136 cases from 2008 to 2016. Case reporting was from hospitals (74%), physicians (16%), workers’ compensation (6%), death certificates (3%), and index case referrals (<1%) (Figure 1, Table E1 in the online supplement). The cumulative incidence rate of silicosis decreased over the 29 years, from 3.7 per 100,000 men 40 years of age and older in Michigan during 1988–1997, to 1.4 during 1998–2007, to 0.7 cases in the most recent reporting period, 2008–2016 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Ascertainment source for confirmed silicosis cases, Michigan, 1988–2016. *Five additional cases were reported through an index case referral during 1988–1997.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence rate of silicosis per 100,000 men aged 40 years and older, overall and by race, Michigan, 1988–2016.

Most of the cases were men (97%), and this did not change over time (Table 1). Overall, 624 (60%) were white, 384 (37%) were African American, and 31 (3%) were classified as other. The percentage of silicosis cases classified as white increased (54–81%), and the percentage of African Americans decreased (43–17%), over the three periods. The overall cumulative incidence rate of silicosis for African American men 40 years of age and older was 6.0 per 100,000 versus 1.2 among white men. Cumulative incidence rates for both races decreased across the three periods (Table 1, Figure 2). The cumulative incidence rate of silicosis for African American men 40 years of age and older decreased from 15.0 cases per 100,000 for 1988–1997, to 4.4 for 1998–2007, to 1.0 in 2008–2016. For white men 40 years of age and older, the cumulative incidence rate of silicosis decreased from 2.3 cases per 100,000 for 1988–1997, to 1.0 for 1998–2007, to 0.6 in 2008–2016. The overall cumulative incidence rate ratio of silicosis among African American men compared with white men was statistically significant at 4.84 (confidence interval, 4.38, 5.36) (P < 0.05). Overall, 8% of all the cases reported Hispanic ethnicity, and this did not change appreciably over time.

Table 1.

Select characteristics of confirmed silicosis cases, Michigan, 1988–2016

| Characteristics | Time Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–1997 | 1998–2007 | 2008–2016 | All Years | |

| Total number of cases | 620 | 292 | 136 | 1,048 |

| Median (range) age of first silica exposure, yr | 25 (12–67) | 23 (11–55) | 24 (10–61) | 24 (10–67) |

| Male sex | 604 (97) | 286 (98) | 131 (96) | 1021 (97) |

| Race (missing) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| White | 333 (54) | 183 (63) | 108 (81) | 624 (60) |

| African American | 263 (43) | 98 (34) | 23 (17) | 384 (37) |

| Other* | 21 (3) | 8(3) | 2(2) | 31 (3) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 21 (10) | 16(7) | 6 (5) | 43 (8) |

| Ever smoked cigarettes | 440 (72) | 214 (75) | 90 (67) | 744 (72) |

| Applied for WC | 220 (42) | 68 (28) | 15 (16) | 303 (35) |

| If applied, awarded WC benefits | 177 (80) | 36 (57) | 8(57) | 221 (74) |

| Cumulative incidence rate† of silicosis per 100,000 men aged ≥40 yr | ||||

| All men | 3.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| White men | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| African American men | 15.0 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 6.0 |

Definition of abbreviation: WC = workers’ compensation.

Data are frequency and percentage or median and range. Totals vary owing to missing information. Race was missing for 9; ethnicity was missing for 475; smoking was missing for 17; and WC information was missing for 189.

Other race includes other, Native American, and Asian.

Denominator is the number of men aged 40 years and older, in Michigan, by race, from Michigan census counts for 1990 (1988–1997 time period), 2000 (1998–2007 time period and for all years combined), and 2010 (2008–2016 time period).

Overall, 72% of the silicosis cases ever smoked cigarettes; this did not change over time. The median age of first exposure to silica was 24 years; this did not change over time. The overall percentage of subjects with silicosis who applied for workers’ compensation was 35%, decreasing from 42% during 1988–1997 to 16% during 2008–2016. Of those who applied, 74% received workers’ compensation benefits, although this decreased from 80% during 1988–1997 to 57% in the latter two periods.

Of the 1,021 chest radiographs available for B reader ILO classification, 222 (22%) were classified as PMF and 383 (38%) as small opacity profusion category 2 or 3 (Table E2). All 29 cases that had a B reader classification of 0/1 or less for a chest radiograph had a positive lung biopsy report consistent with silicosis. There was minimal variation in the distribution of the profusion of opacities on the chest radiographs over time.

Only 151 of 1,048 (14%) cases had a pathology report for a lung tissue biopsy: 99 (66%) were consistent with a diagnosis of silicosis, 5 (3%) were inconsistent, and 47 (31%) were inconclusive. The inconsistent reports were because the biopsy was done to assess for a lung condition unrelated to silicosis; the inconclusive reports had insufficient tissue to confirm a diagnosis. We used radiographic results to confirm the 52 cases with inconsistent or inconclusive pathology.

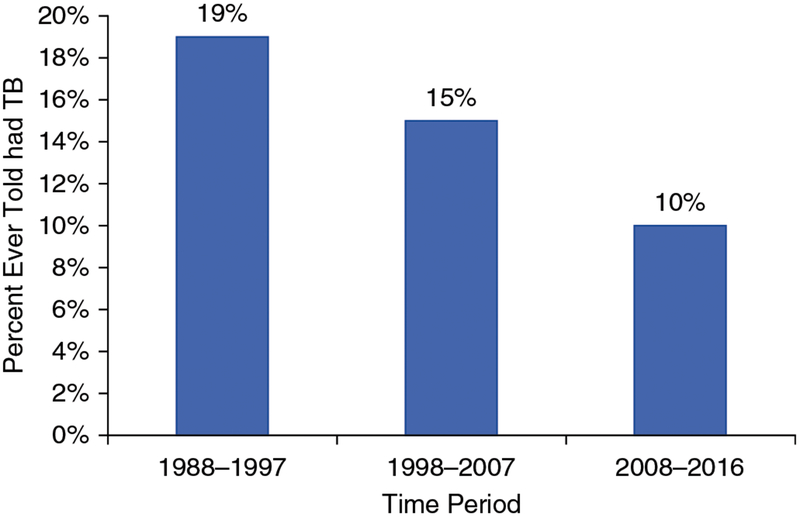

Of the 723 cases with information on whether a TB skin test was performed, 580 (80%) indicated that they had ever had a skin test for TB; 88 (16%) had a positive result (Table E3). The percentage with a positive TB skin test did not change over time. The medical questionnaire also asked whether cases ever had active TB, regardless of whether a skin test had ever been done; 148 (17%) of 888 reported that they had ever had active TB. The percentage of active TB decreased over the three periods from 19% during 1988–1997 to 10% during 2008–2016 (Figure 3, Table E3). Over the 29-year period, 14.1% of subjects reported having TB; the proportion with active TB decreased from 16.3% in the first decade of surveillance to 7.4% in the most recent period. In comparison, the annual percentage of subjects with active TB in the United States from 1988 to 2016 was 0.003–0.010% and in Michigan from 2013 to 2017 was 0.001% (17).

Figure 3.

Percentage of individuals ever told they had tuberculosis, Michigan, 1988–2016. TB = tuberculosis.

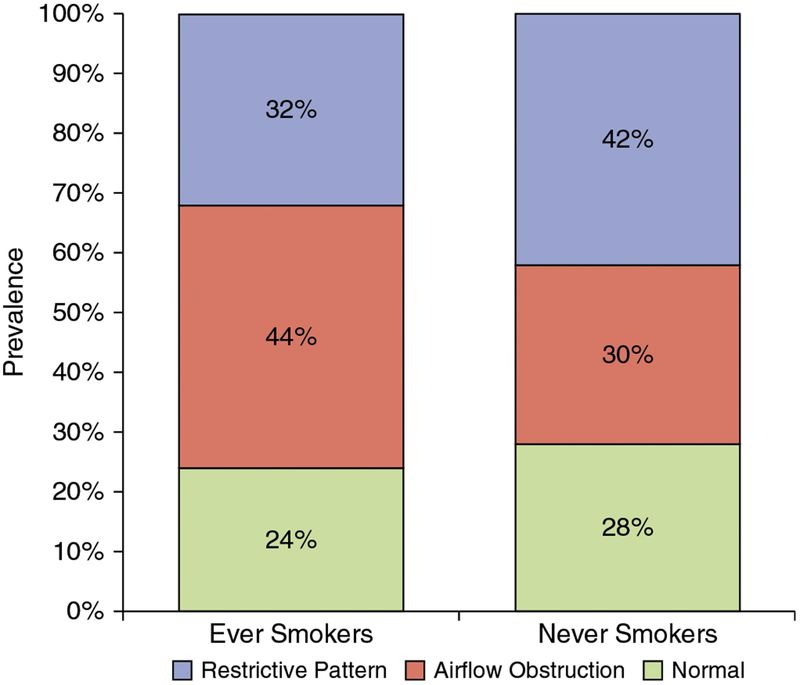

We obtained spirometry results for 607 (58%) of the 1,048 cases. An obstructive pattern was more common in ever smokers, with 44% versus 30% among never smokers, and a restrictive pattern was more common in never smokers, with 42% versus 32% among ever smokers (Figure 4, Table E4). Only 24% of ever smokers and 28% of never smokers had normal spirometry. Subjects in all profusion categories had abnormal spirometry; there were higher percentages of both obstructive and restrictive changes within ILO category 3 or PMF than in subjects with lower-level radiographic profusion of opacities. There was a downward trend in obstruction in never smokers in the most recent decade, presumably secondary to some degree of reduction in silica exposure (Table E4).

Figure 4.

Restriction, obstruction, and normal spirometry results by cigarette smoking status of confirmed silicosis cases, Michigan, 1988–2016.

We obtained death certificates for 701 (99%) of the 711 confirmed cases who died. The death certificate recorded silicosis for only 59 (8%) subjects across all levels of disease severity. For subjects with advanced silicosis, characterized as PMF or category 3 profusion, the death certificate noted silicosis in 11% (for PMF) and 10% (for category 3 profusion), respectively. However, 45% of the underlying causes of death were respiratory, including COPD (98 cases, 14%), lung cancer (80 cases, 11%), unspecified interstitial fibrosis or respiratory failure (70 cases, 10%), pneumonia (42 cases, 6%), asbestosis or nonspecified pneumoconiosis (19 cases, 3%), TB (4 cases, 1%), and sarcoidosis (3 cases, <1%).

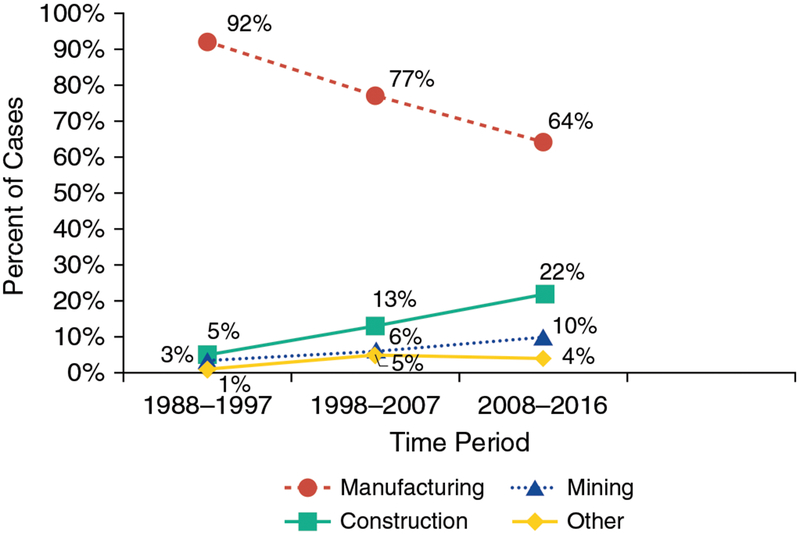

The primary industries for silica exposure were manufacturing, with 874 (84%) cases; construction, with 98 (9%) cases; and mining, with 47 (5%) cases (Figure 5, Table E5). Silica exposure from employment in manufacturing decreased over time, from 92% to 77–64%, whereas silica exposure from employment in mining (3–6% to 10%) and construction (5–13% to 22%) increased. Within manufacturing, foundries represented 706 (81%) cases. Silica-exposed workers in foundries performed tasks such as chipping and grinding, maintenance, molding and casting, and general labor. Within construction, silica-exposed workers performed tasks such as bricklaying, sandblasting, doing general labor, demolition, or excavation work. Silica-exposed workers in mining performed tasks such as mining or drilling or worked as a quarry worker, sand loader, sand drier, or heavy equipment operator. Table E5 shows the percentage of subjects who did sandblasting within each industry type, by period. Overall, 37% had ever performed sandblasting; this percentage remained relatively unchanged over the three periods. Of note, the highest percentage of sandblasting was in the “other” industry category, with 67% ever performing sandblasting.

Figure 5.

Industry reported as source of silica exposure for confirmed silicosis cases, Michigan, 1988–2016.

The average duration of potential exposure to silica was 27 years (range, 1–60 yr); however, 101 (10%) of the cases were exposed to silica for 10 years or less. The distribution of the duration of exposure to silica has not changed over time, with cases still occurring after less than 10 years of exposure (Table E6).

The confirmed silicosis cases were exposed to silica in 452 facilities; Michigan OSHA inspected 78 of those facilities over the 29 years. Michigan OSHA conducted air sampling for respirable silica during 55 of the 78 inspections (Table E7). Thirty-four (62%) facilities were above the NIOSH REL of 50 μg/m3 for silica. Twenty-one (38%) were above the enforceable Michigan OSHA PEL of 100 μg/m3 for silica. Because facilities where silica exposure occurred were no longer in operation or had been inspected previously, the number of inspections decreased in recent years, but the percentage above the OSHA or NIOSH exposure limits was similar over time. Two companies inspected during 1988–1997 were not above the PEL or REL for silica, but both did not provide adequate respirators for sandblasting, and both were in violation of the Michigan OSHA abrasive blasting standard. Michigan OSHA was able to evaluate the medical surveillance program at 70 of the 78 inspections. Only 8 of the 70 (11%) facilities provided medical screening specifically for silicosis for its workers that included a periodic chest radiograph classified by a B reader.

Discussion

Over the last 29 years, the Michigan surveillance system confirmed 1,048 silicosis cases, primarily through hospital discharge data (Figure 1, Table E1). The reports of silicosis submitted to the state as required by law in Michigan have decreased by 81% from 1988–1997 to 2008–2016. We attribute the decrease in reporting to several factors: industry trends, underrecognition of the disease, and underreporting. The traditional employer of the Michigan silicosis cases was foundries. However, the number of foundries and foundry employees has significantly decreased in Michigan, from 81 foundries employing 10,051 individuals in 1997 to 58 foundries employing 3,658 individuals in 2016 (Bureau of Labor Statistics data extract of Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages). Although it is encouraging to see the decrease in silicosis cases from foundries, it is important to be watchful of other emerging industries that have a large number of workers potentially exposed to silica. Emerging industries include engineered stone countertop manufacture and installation, highway repair, and oil and gas hydraulic fracturing. Because many workers in these emerging construction and mining-related activities have less than 20 years of silica exposure, their risk for developing silicosis will increase over time, and we expect that these emerging industries with silica exposure will contribute to an increased number of silicosis cases identified in the future (Table E5).

Underrecognition and consequent underreporting of silicosis have also contributed to the decrease in silicosis case reporting over time. For workers still alive, silicosis is not a common lung disease, so physicians and radiologists may not recognize the disease when a worker seeks care, especially at an early stage. Furthermore, occupational histories are often incomplete in the medical history, thereby missing the identification and documentation of silica exposure for the patient. Finally, before 2018, silica-using employers were not obligated to have a medical monitoring program, thus precluding occupational medicine physicians at these industries from having access to chest radiographs of the silica-exposed workers. Underrecognition and subsequent underreporting of silicosis can also be found in mortality statistics.

Death certificate data represent one of the main statistics used nationally to monitor trends in silicosis (18). However, death certificate data are not a reliable measure of the true occurrence of silicosis. We found that, regardless of the severity of radiographic changes, only 8% of death certificates of confirmed cases had silicosis recorded on the death certificate. In contrast, 45% of the silicosis subjects’ death certificates listed etiologies such as pneumonia, COPD, lung cancer, unspecified interstitial fibrosis, or respiratory failure as the cause of death. Over the last 25 years, the ratio of individuals confirmed with new-onset silicosis in Michigan who were living was 7.17 times that found on death certificates. This ratio has increased from 6.44 in 2003 to 15.2 in more recent years. National statistics show the same trend, with a decrease of silicosis listed on the death certificate (276 in 1993 and 89 in 2011) but a stable and slightly increasing number of hospitalizations (2,028 in 1993 and 2,082 in 2011) (Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/). The national living-to-deceased ratio increased from 7.3 in 1993 to 23.4 in 2011. These increased ratios in Michigan and nationally demonstrate that silicosis is missed being recorded on death certificates, thereby artificially lowering the statistics on silicosis.

The new OSHA silica standard lowers the PEL by 50%, dropping the new enforceable OSHA PEL to that of the more protective NIOSH REL of 50 μg/m3. Although the number of inspections in Michigan has decreased over the 29 years of surveillance, the percentage of companies with elevated silica levels has not decreased. We found that 62% of the companies inspected in Michigan where respirable silica was measured were above the NIOSH REL. Accordingly, we expect that inspections of Michigan silica-using companies, including foundries, will identify air levels above the new enforceable OSHA PEL and that companies will be required to take action to lower their silica levels.

The new OSHA standard also requires medical monitoring of silica-exposed employees. We found that only 8 of 70 (11%) Michigan companies inspected provided medical surveillance for their silica-exposed workers with a chest radiograph interpreted by a NIOSH certified B reader. The majority of our cases had severe disease; 22% had evidence of PMF, and another 38% had an ILO small opacity profusion category of 2 or 3 (Table E2). We expect the new requirement for silica-using employers to provide medical monitoring and to refer individuals with minimum changes on a chest radiograph consistent with silicosis (⩾1/0 rounded opacities on the ILO classification system) to board-certified pulmonologists or occupational medicine physicians to increase recognition of the disease and decrease its severity by making an earlier diagnosis. In addition to severe disease identified through chest radiographs, high percentages of the subjects had abnormal spirometry and a much greater risk of TB than the general population.

Only 25% of the cases in our cohort had normal spirometry. Silicosis has been reported to cause both restrictive and obstructive patterns on spirometry (1, 2, 19). In this cohort, 30% of the never smokers demonstrated obstruction, and an even higher percentage (44%) of ever smokers had obstruction (Figure 4). The Michigan data show a downward trend in obstruction in never smokers in the most recent decade, presumably secondary to some degree of reduction in silica exposure (Table E4). Pulmonologists must be aware that obstruction may be the only pulmonary function abnormality, even though silicosis is typically classified as a restrictive lung disease.

Furthermore, clinicians who treat silica-exposed workers need to consider active TB in these patients who present with new radiographic abnormalities or infections failing to improve with usual antibiotic therapy. The incidence of TB in the confirmed Michigan silicosis cases was 7%. This is 1,000-fold greater than that in the general population (Figure 3, Table E3) in the last decade.

In addition, it is important that clinicians be aware of groups that have traditionally experienced greater exposure to silica. In the Michigan silicosis cohort, African Americans had an incidence of silicosis that was fivefold greater than in whites (Table 1). The increased risk of silicosis has also been reported among blacks in the South African gold mines and among Navaho workers in U.S. uranium mines (20, 21). The increased risk in Michigan has been attributed to past discriminatory hiring and promotion practices in Michigan’s foundries (22).

Finally, despite the clear connection of silicosis with work, the percentage of workers with confirmed silicosis applying for workers’ compensation, which was never high (42% in 1988–1997) has dropped to 16% in the most recent period (Table 1). Even among retirees, workers’ compensation is a useful benefit because there is no insurance deductible, including for medication. Proper management of patients with silicosis should include encouraging patients to apply for compensation to receive coverage for healthcare costs for silicosis and associated conditions such as COPD.

Conclusions

Despite an overall decreasing incidence, silicosis with advanced disease and morbidity still occurs in Michigan. In addition, silica exposure is associated with other diseases, such as COPD, connective tissue disease, chronic renal disease, and lung cancer (19, 23–25). Cases of silicosis are underreported; healthcare providers must incorporate a detailed occupational history on patients with interstitial lung disease, regardless of their presenting diagnosis, to correct this problem. On the basis of inspections cited in this report, workers still have ongoing overexposure to silica. The newly implemented OSHA silica standard mandates that companies provide a safer work environment and medical monitoring and refer workers identified in these medical monitoring programs with possible silicosis to board-certified pulmonologists, who accordingly will need to familiarize themselves with the recognition, management, and public health implications of patients with silicosis and silica exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a cooperative agreement from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (U60-OH008466).

Footnotes

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Leung CC, Yu IT, Chen W. Silicosis. Lancet 2012;379:2008–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safety Occupational and Administration Health. Occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica—review of health effects literature and preliminary quantitative risk assessment. Docket OSHA-2010-0034. 2010. [accessed 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/silica/Combined_Background.pdf.

- 3.American Thoracic Society Committee of the Scientific Assembly on Environmental and Occupational Health. Adverse effects of crystalline silica exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Health effects of occupational exposure to respirable crystalline silica. 2002; DHHS (NIoSh) Publication Number 2002-129. Apr 2002. [accessed 2014 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-129/pdfs/2002-129.pdf.

- 5.Friedman GK, Harrison R, Bojes H, Worthington K, Filios M; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Notes from the field: silicosis in a countertop fabricator — Texas, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:129–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoy RF, Baird T, Hammerschlag G, Hart D, Johnson AR, King P, et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis: a rapidly emerging occupational lung disease. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quail MT. Overview of silica-related clusters in the United States: will fracking operations become the next cluster? J Environ Health 2017; 79:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valiante DJ, Schill DP, Rosenman KD, Socie E. Highway repair: a new silicosis threat. Am J Public Health 2004;94:876–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rees D, Murray J. Silica, silicosis and tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007;11:474–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steenland K. One agent, many diseases: exposure-response data and comparative risks of different outcomes following silica exposure. Am J Ind Med 2005;48:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brüske I, Thiering E, Heinrich J, Huster KM, Nowak D. Respirable quartz dust exposure and airway obstruction: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gómez-Puerta JA, Gedmintas L, Costenbader KH. The association between silica exposure and development of ANCA-associated vasculitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:1129–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Volume 68: Silica. Geneva: IARC Press; 1997. [accessed 2018 Oct 15]. pp. 41–242. Available from: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono68.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: arsenic, metals, fibres, and dusts. Volume 100 C: A review of human carcinogens. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2012. [accessed 2018 Oct 15]. pp. 355–405. Available from: https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono100C.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenman KD, Reilly MJ, Kalinowski DJ, Watt FC. Silicosis in the 1990s. Chest 1997;111:779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Labour Office (ILO). Guidelines for the use of the ILO international classification of radiographs of pneumoconioses. Occupational safety and health series no. 22 (Rev. 2000). Geneva: International Labour Office; 2002. [accessed 2018 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_108568.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Tuberculosis cases and rates [accessed 2018 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/2016MI_County_TUBERCUL0SIS_CASES_552484_7.pdf.

- 18.Rosenman KD, Reilly MJ, Henneberger PK. Estimating the total number of newly-recognized silicosis cases in the United States. Am J Ind Med 2003;44:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenman KD, Reilly MJ, Gardiner J. Results of spirometry among individuals in a silicosis registry. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:1173–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowie RL, Mabena SK. Silicosis, chronic airflow limitation, and chronic bronchitis in South African gold miners. Am Rev RespirDis 1991;143: 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brugge D, Goble R. The history of uranium mining and the Navajo people. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1410–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foote CL, Whatley WC, Wright G. Arbitraging a discriminatory labor market: black workers at the Ford Motor Company, 1918–1947. J Labor Econ 2003;21:493–532. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makol A, Reilly MJ, Rosenman KD. Prevalence of connective tissue disease in silicosis (1985–2006)—a report from the state of Michigan surveillance system for silicosis. Am J Ind Med 2011;54:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millerick-May ML, Schrauben S, Reilly MJ, Rosenman KD. Silicosis and chronic renal disease. Am J Ind Med 2015;58:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenman KD, Stanbury MJ, Reilly MJ. Mortality among persons with silicosis reported to disease surveillance systems in Michigan and New Jersey in the United States. Scand J Work Environ Health 1995; 21:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.