Abstract

All membrane proteins have dynamic and intimate relationships with the lipids of the bilayer that may determine their activity. Mechanosensitive channels sense tension through their interaction with the lipids of the membrane. We have proposed a mechanism for the bacterial channel of small conductance, MscS, that envisages variable occupancy of pockets in the channel by lipid chains. Here, we analyse protein-lipid interactions for MscS by quenching of tryptophan fluorescence with brominated lipids. By this strategy we define the limits of the bilayer for TM1, which is the most lipid exposed helix of this protein. In addition, we show that residues deep in the pockets, created by the oligomeric assembly, interact with lipid chains. On the cytoplasmic side, lipids penetrate as far as the pore-lining helices and lipid molecules can align along TM3b perpendicular to lipids in the bilayer. Cardiolipin, free fatty acids, and branched lipids can access the pockets where the latter have a distinct effect on function. Cholesterol is excluded from the pockets. We demonstrate that introduction of hydrophilic residues into TM3b severely impairs channel function and that even ‘conservative’ hydrophobic substitutions can modulate the stability of the open pore. The data provide important insights into the interactions between phospholipids and MscS and are discussed in the light of recent developments in the study of Piezo1 and TrpV4.

Keywords: lipid-protein interaction, fluorescence quenching, brominated lipids, tension sensing, electrophysiology

Introduction

Lipid interactions with membrane proteins are complex and have often proved challenging to measure[1–5]. Despite this, much has been achieved to generate an understanding of the dynamics of proteins-lipid interactions[3, 6–13]. All membrane proteins and protein complexes are surrounded by a boundary lipid layer that is in dynamic exchange with bulk lipid[2]. The number of phospholipid (PL) molecules surrounding a protein complex is dictated both by its effective circumference and by the packing of the lipids, which provides a barrier to ions[2, 14]. The lipid chains exist in a ‘fluid’ state in the interior of the bilayer. In a time-averaged manner the lipid chains will pack closely against the protein surface, following the contours and thereby filling any interstices that exist[9]. In some classes of membrane proteins, e.g. some secondary transporters, lipid-protein interactions are a major determinant of conformation[3, 13]. It is recognized that lipids are central to the mechanism of gating of mechanosensitive channels (the ‘Force-from-lipids’ concept[15–17]).

Modulations of tension in the lipid bilayer, in response to changes in transmembrane turgor, are believed to gate mechanosensitive channels leading to ion (and solute) movement across the membrane[18–20]. In bacteria, such channels are central to maintaining cellular integrity during severe osmotic transitions that generate extremely high transmembrane turgor pressure[21–23]. High turgor pressure leads to tears in the peptidoglycan layer through which cytoplasm is extruded during cell bursting. The potential damage is countered by the release of solutes through the channel pore. It is implicit in this model that high turgor generates transitions in the bilayer tension[22–26]. An additional factor is that a number of lipid-like molecules can activate mechanosensitive channels in the absence of changes in cell turgor. These molecules include local anaesthetics, lyso-phospholipids and polyunsaturated lipids[27–30]. We have only a limited understanding of the molecular mechanism by which tension is sensed and the signal transduced[31, 32].

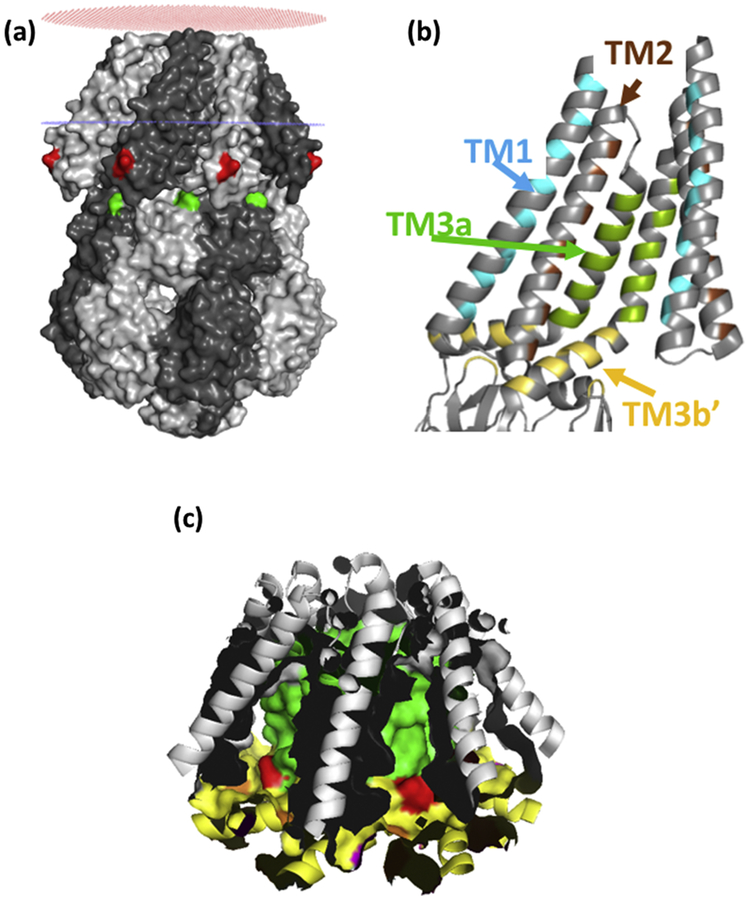

The structures of the bacterial mechanosensitive channels provide both the context for models of tension-sensing via lipid interactions but also clues to the possible mechanism[31–33]. Multiple crystal structures exist for the MscS channel[32, 34, 35]. The core structure is a heptamer of identical subunits (Figure 1a; Figure S1a) that oligomerize to form the transmembrane pore and a large cytoplasmic domain. Each subunit contributes three helices to the membrane domain: TM1 and TM2 form antiparallel transmembrane helices that have the potential to interact with the lipids of the bilayer whereas TM3 is in two parts – seven identical TM3a helices combine to create the transmembrane pore, whereas TM3b lies parallel to the membrane surface and integrates with the upper β sub-domain of the cytoplasmic domain (Figure 1b). The E. coli MscS protein has been solved in two principal states: a closed state in which the pore is sealed by two rings of leucine residues (L105 and L109), brought into proximity by the tight packing of the TM3a helices[34], and an open state in which the TM3a helices have straightened relative to the pore axis and moved apart to break the seal[35]. Concurrent with these changes in organisation the TM1–2 helix pair rotate around the axis of the pore and the TM1–2 helices are packed more closely against the pore helices[35]. Although, the static nature of crystal structures has caused them to be treated with caution [19], they frame the argument for the interaction with lipids, which must change during the transition from closed to open[35].

Figure 1.

(a) OPM model of surface-rendered closed structure MscS. I57 (red), and I150 (green) are marked. Red and blue rings indicate the position of the lipid/headgroup region of the periplasmic and cytoplasmic leaflets of the bilayer, respectively. (b) Hydrophobic pocket in MscS; seven identical hydrophobic pockets are created by residues on TM1 (cyan)) TM2 (brown), TM3a (green) and TM3b/beta domain (Yellow). The pocket is a volume that is contiguous with the membrane bilayer and is not a binding site for lipids. It is proposed that the lipid chains of the phospholipids that surround the periphery of MscS reversibly and dynamically penetrate the pockets. Only two subunits are shown for clarity. (c) The surface of the pockets are shown with the same colour scheme as in (b). L111 is marked in red. All images are based on the closed structure (pdb: 2OAU).

The OPM (Orientations of Proteins in Membranes) database[36] predicts the lipid packing, for a simple planar bilayer, around membrane proteins for which a crystal structure is known. When applied to the closed structure (Figure 1a, pdb: 2OAU) a clear prediction is made that the cytoplasmic ends of the transmembrane helices (TM1 & TM2) are exposed to the aqueous phase. However, for MscS the lipid-exposed surface is rendered more complex by the presence of pockets created by the TM2, TM3a, TM3b and residues in the β subdomain that penetrate the interstices between TM3b helices from adjacent subunits (Figure 1b)[32]. We have recently proposed that displacement of lipids from the pockets, as a result of increased bilayer tension, favours the open conformation of the channel[32], which is predicted to have smaller pockets.

There are a number of structural features of MscS that lend themselves to this model. Firstly, the overall character of the amino acid residues of TM1–2 and TM3a is hydrophobic[34]. Secondly, the TM3b helix is amphipathic with the hydrophobic surface predicted to interact with lipids[34] (Figure S2). Thirdly, hydrophobic residues from the β domain penetrate between the interstices between the seven TM3b helices. The overall effect is of a hydrophobic protein disc (TM3b plus “β domain” side chains) that is perforated at its centre by the MscS pore. Thus, the overall character of the residues in this disc, and those exposed from TM3a and TM1–2, creates a hydrophobic pocket that is ideal for lipid occupancy (Figure 1c). We sought to test the hypothesis that lipids penetrate the pocket and that the hydrophobic character of TM3b is essential to gating of MscS. We have utilised a combination of quenching of introduced Trp residues by brominated lipids[4, 5, 37, 38] and site-directed mutagenesis of the TM3b hydrophobic surface. The data point to deep penetration of the structure of the MscS channel complex by membrane lipids and fatty acids. Further, we show that branched chain lipids cause unique modifications of MscS behaviour in liposomes. Finally, we have identified a critical requirement for hydrophobic residues in TM3b, and a specific role for Val122, in determining the tension-sensitivity and the stability of the open state of MscS.

Results

Protein-lipid interactions - experimental strategy.

Protein lipid interactions are frequently difficult to investigate. However, significant advances have been made by the use of either spin-labelled lipids or brominated lipids[4, 5, 8, 39, 40]. For the latter, the bulky bromine atoms cause the fatty acid chains to behave similarly to unsaturated lipids[38]. The quenching of Trp residues by the bromine aims can give information on accessibility of the residue to lipids and hence create structural insights from the reconstituted membrane protein. Bromine atoms that are distant to the lipid head group can ‘explore’ a larger volume of space in a time-dependent manner due to the intrinsic flexibility of the lipid chain. The region close to the head group has been suggested to have more limited flexibility compared with the terminal methyl group[41]. Bromine atoms quench Trp residues that are either native or have been introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. Quenching has been reported to involve very close proximity between the bromine atoms and the Trp side chain (~9 Å; [42]). Thus, we sought to investigate the protein-lipid interactions in MscS using commercially available and synthetic lipids in combination with site-directed mutagenesis to create mutant proteins at informative positions.

Membrane bilayer alignment to TM1

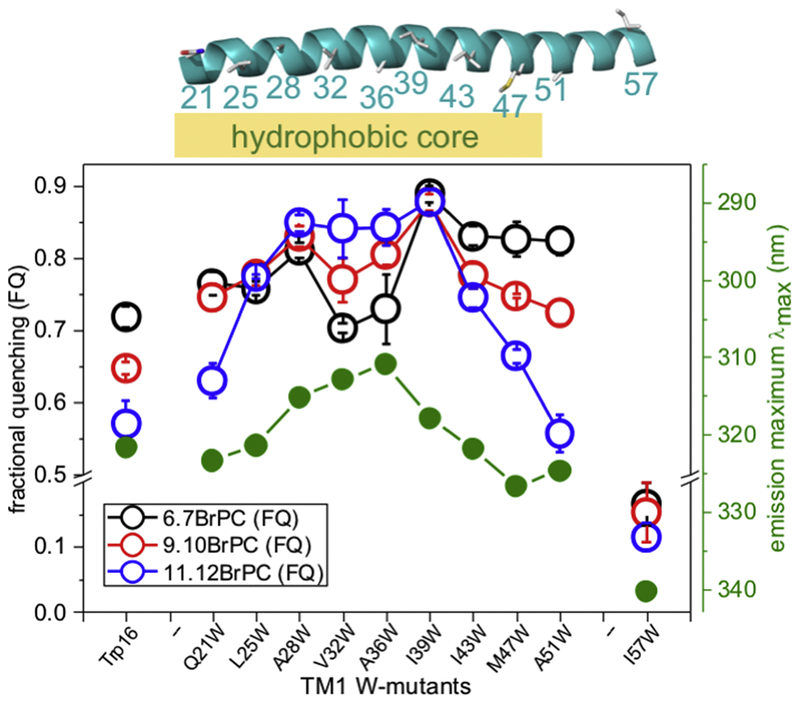

The OPM model[36] of MscS positioning in a planar bilayer (Figure 1a) suggests that the hydrophobic leaflet extends approximately from residue N20 to the basic amino acid R46 of TM1 (based on the most complete MscS crystal structure, 5aji.pdb). Previously, it was assumed that the whole paddle, extending to R59, is immersed into the membrane [34] but it is a clear prediction from the OPM model that this region may reside in or below the headgroup region. To investigate the lipid interactions with MscS TM1, potentially lipid-facing residues extending from A21 to I57 were mutated to Trp (SI text; Figure S3–4). All of the Trp mutants exhibited blue-shifted emission maxima with the exception of I57W (Table S1), consistent with locations in hydrophobic environments. Raw data for all the Trp mutants analysed are given in the SI (Table S1). Reconstitution of purified MscS Trp mutant channels was performed into brominated phosphatidyl choline (C-18 BrPC) vesicles, with DOPC as the control (Figure S5)[32]. To complement these data with more detailed insights, we utilised commercially available C-18 brominated lipids in which the bromine atoms are at different distances from the head group (6.7BrPC, 9.10BrPC and 11.12BrPC). Tryptophan at positions corresponding to residue 21 to residue 51 exhibited high levels of quenching (Figure 2; Table S1). All of the Trp residues exhibited quenching with 9.10BrPC but residues close to the N and C termini of TM1 exhibited greatest quenching with 6.7BrPC (Q21W, I43W, M47W and A51W). Conversely a stretch of residues from A28W to I39W exhibited higher quenching with 11.12BrPC than with 6.7BrPC (Figure 2), consistent with these residues lying close to the centre of the bilayer. Thus, the differentially-labelled lipids define the depth of the hydrophobic component of the bilayer centred on residues A28–I39.

Figure 2: Association of the membrane bilayer to TM1.

Fractional quenching for W-mutants on TM1 are shown for reconstitutions with lipids brominated at different positions along the fatty acid chains (key: black, 6.7BrPC; red, 9.10BrPC; blue, 11.12BrPC). Emission maxima for the individual mutants are shown in green. The centre of the membrane is approximately at residues A34-L35. The structure of TM1 from the MscS structure D67C (PDB: 5AJI) is shown on top indicating the hydrophobic core region of the membrane (orange). Data for Trp16 are shown on the left.

Residue I57W at the carboxy-terminal extremity of TM1 provided one of the most interesting results. The emission peak position of I57W is 340.3±0.2 nm (Table S1), which is typical for Trp residues with access to the water. Similar values were observed for Q203W and D213W on the surface of the cytosolic domain[32, 43]. The fractional quenching for this residue was very low (0.17±0.04) and did not vary significantly with the position of the Br atoms (Figure 2). These data suggest that I57W is exposed to a polar environment possibly contiguous with the water phase or the water-accessible glycerol moiety of the phospholipids[2, 44–46].

We have previously identified the native, semi-conserved, Trp16 as critical for setting the gating threshold[47]. The structure of this region has not been resolved, although modelling has been undertaken[48]. MscS W240F/W251F[47] mutant channel has Trp16 as its single native Trp residue. When reconstituted with different brominated lipids, significant quenching was observed that was greatest for 6.7BrPC and least for 11.12BrPC (Figure 2). This establishes that this critical residue is buried in the lipid bilayer.

Do lipids occupy pockets in the MscS structure?

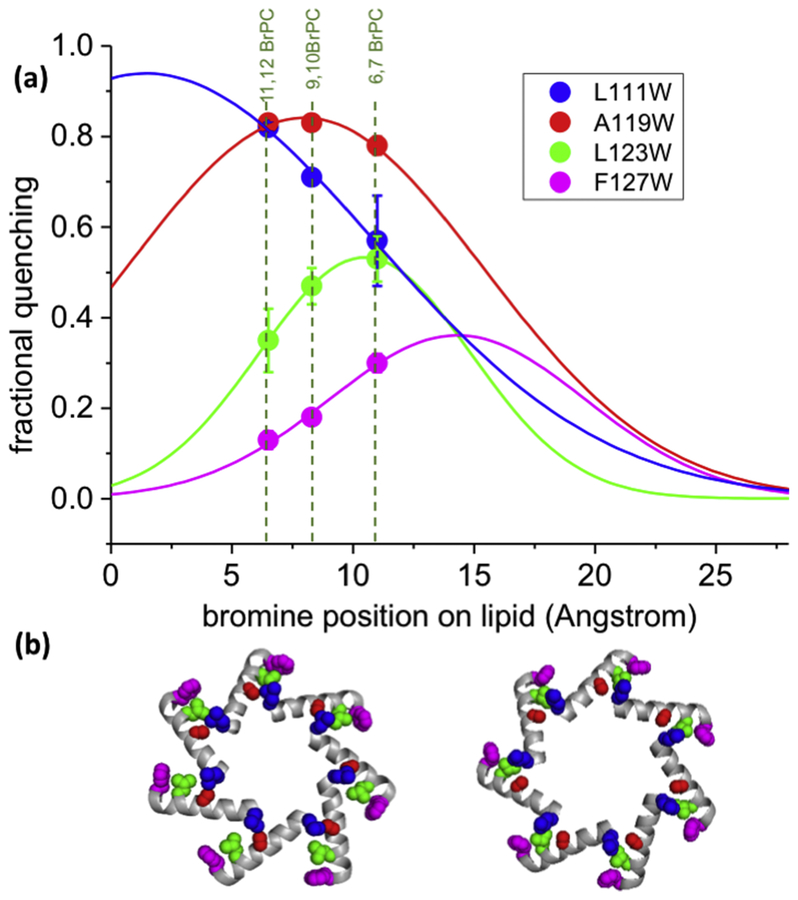

The molecular structure of MscS exhibits grooves and pockets that are created by the TM1–2 helix pair, TM3b and the channel pore created by seven TM3a helixes[34] (Figure 1b,c). Previous work suggested that lipids might occupy the pockets and align with the hydrophobic surface of TM3b[32]. To investigate this possibility in greater depth, native residues were exchanged for Trp at positions of interest throughout TM2, TM3a and TM3b where the amino acid side chains are predicted to project into the pockets (Figure 1c; Figure S1b))[32, 34, 35]. In addition, two mutations were created in the β domain (I150W and F151W)))[32, 34, 35]. BrPC quenched residues lining the proposed pocket, with the lowest quenching observed for residues close to the carboxy-terminus of TM3b (e.g. F127W; Figure 3; Table S1). It was notable that I150W, which lies proximal to F127, exhibited high quenching (Table S1).

Figure 3: Distance dependent quenching of tryptophan probes located on TM3b.

(a) Fractional quenching by 6.7BrPC, 9.10BrPC and 11.12BrPC for L111W (blue), A119W (red), L123W (green), and F127W (magenta) are shown as points. These data were fitted to Gaussian curves (lines). These data suggest that the phosphate groups of the lipids are located approximately beside F127 if they adopt a stretched conformation. (b) Relative positions of residues on TM3b using same colour code as in (a); Left, closed structure, 2oau; Right, open structure, 5aji.

Analysis of quenching with lipids with bromine at different positions revealed that Trp residues close to the periphery of MscS (F127W, F150W & I151W) were quenched more readily by 6.7BrPC than by 11.12BrPC. Conversely, residues lying deep within the proposed pockets (A103W, & L111W) were more readily quenched by 11.12BrPC (Table S1). Residues at intermediate positions (A119W and L123W) were less affected by the position of the bromine atom in the lipid but showed a high overall level of quenching (Figure 3; Table S1). The ratio of quenching by 11.12BrPC to quenching by 6.7BrPC indicates the positional dependence of Br/Trp interaction. This ratio is highest for L111W (1.43), lowest for F127W (0.43), with intermediate values for A119W (1.06) and L123W (0.66). A Gaussian distribution was fitted to the quenching data and exhibited broad profile (Figure 3). This Gaussian distribution reflects the relative molecular movement and flexibility of probe and quencher, which broadens the effect of the intrinsically short-distance quenching mechanism. These data are consistent with lipid chains from the phospholipids aligning with TM3b such that their terminal methyl group closest to the pore helix (TM3a) and the charged phosphate group located on the periphery of MscS (defined by F127, I150 and F151) (Figures 1 & Figure S1b) which is almost perpendicular to lipids within the membrane.

We have previously characterised G113W as a fully functional Trp mutant that lies within the vestibule on the cytoplasmic side and should have least access to lipids, thereby acting as a control for the other mutants. G113W exhibited very low quenching (0.07±0.04; Table S1) consistent with its position. Residues A94 and G101 form the TM3a inter-helix interface close to the pore entrance. Perturbation of that interface by substitution of residues with larger side chains inhibits channel function[49]. Trp mutations at these positions carry a degree of uncertainty of the position of the side chain. The λmax values (322.5±2.7 and 315.2±3.3 for A94W and G101W, respectively) are intermediate between those for fully exposed and buried Trp residues (Table S1). However, fractional quenching of A94W and G101W by brominated lipids (0.81±0.01 and 0.72±0.01, respectively; Table S1) is consistent with high access of the Trp side chain to lipids.

Free fatty acids are expected to have a significant presence in the E. coli membrane, arising from lipid turnover[50]. Moreover, fatty acids are convenient mimics for known activators of MscS, e.g. local anaesthetics[28, 29, 51]. Interaction of free C16 fatty acids (FA) with MscS was tested by synthesis of brominated fatty acids from their equivalent C16-unsaturated precursors (see SI). Bromination was obtained at positions 4–5, 9–10 and 15–16. Reconstitution in lipid mixtures containing brominated fatty acids led to quenching of Trp residues in the pocket with similar trends to those observed for BrPC (Figure S6). However, quenching of L111W was not significantly dependent on the position of the bromine atoms along the fatty acid chain. Control experiments show that this residue is more affected than A119W and L123W by the solvent, methanol, that was used to introduce the fatty acids. Methanol caused a red-shift and intensity increase for L111W (Figure S6). These data are consistent with fatty acids aligning in the pockets with their carboxylate groups oriented similar then the phospholipid head groups.

Defining the dimensions of the lipid pocket using competition experiments.

Competition experiments utilising the quenching assay with brominated lipids are a useful tool to investigate the dimensions of the proposed lipid pocket. Cardiolipin (CL) is present at a low percentage in E. coli membranes[52]. Uniquely it has 4 fatty acid chains per head group, and the head group is diminished due to the absence of choline or a related base. Cholesterol is not synthesized by bacteria but can be absorbed from the mammalian host and incorporated into membranes[53]. In this study cholesterol is a rigid volumetric probe as it associates only poorly with the brominated lipids with bromine atoms in both chains[38]. Thus, MscS Trp mutants A119W and L111W were reconstituted into mixtures of either cardiolipin (CL) or cholesterol (Chol) where these lipids replaced part of the BrPC (ratio BrPC:CL or Chol, 67:33). Intrusion into the pockets by either CL or Chol would replace brominated lipid chains and hence reduce the quenching. A clear de-quenching of about 25% was observed for mutants A119W and L111W when CL partially replaced BrPC in the reconstitution lipids (Figure S7) indicating that CL lipid chains can penetrate the pockets. In contrast, the presence of cholesterol did not lead to measurable de-quenching (Figure S7) suggesting that cholesterol is excluded.

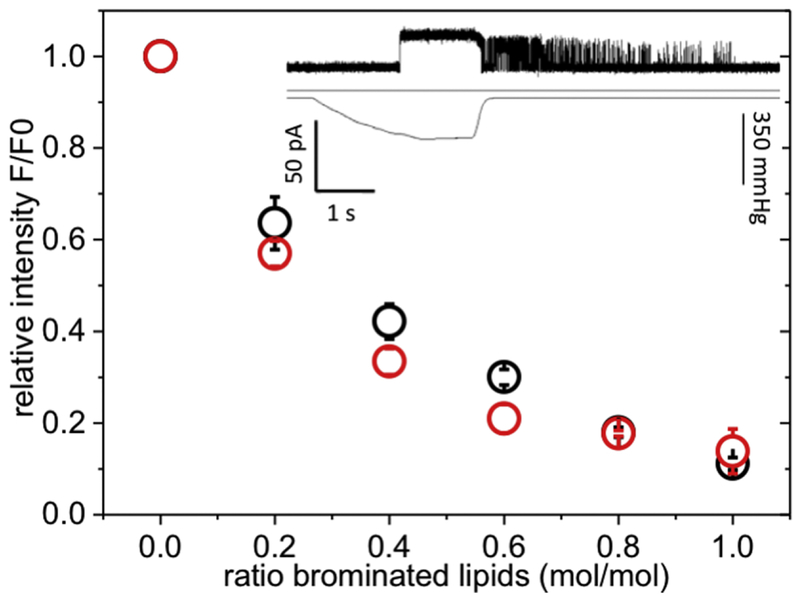

Branched lipids have previously been used to analyse the mechanism of the TRAAK channel[54]. It was demonstrated that branched chain phospholipids could not readily penetrate the ‘pocket’ in TRAAK and consequently the channel remained conductive when reconstituted in the presence of these lipids[54]. We thus sought to determine whether branched chain phospholipids would penetrate the pockets of MscS. Mutant A94W was chosen for analysis on the basis that it is one of the Trp residues most remote from the end of TM3b (see above Fig. 3). MscS A94W was reconstituted into different ratios of the branched phospholipid, 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (4Me-16:0-PC), and BrPC and the fluorescence intensities were measured (Figure 4) using mixtures of DOPC and BrPC as controls. Mixtures of BrPC with branched lipids quench to a similar degree as BrPC/DOPC mixtures as control (Figure 4; compare red and black dots), indicating that these lipids readily access the pocket. However, when WT MscS was reconstituted into the branched lipid (4Me-16:0-PC) as the sole lipid in liposomes the channels retained a “flickery” state with fast openings and closings after pressure was released (n = 12; Figure 4 insert; Figure S8), rather than the expected closure. This behaviour is reminiscent of that observed with polyunsaturated phospholipids[30]. Our data suggest that branched lipids can access the pockets and have there a profound effect on gating.

Figure 4: Access of branched lipids to the pockets of MscS.

Relative fluorescence intensity of MscS ΔW A94W in mixtures of 4Me-16:0-PC with BrPC (red) or DOPC with BrPC (black) showing the competition of the branched lipid with the normal un-branched lipid within the pore. The fluorescence intensities were normalised to the sample reconstituted in 100% non-brominated lipid. The insert shows a representative electrophysiological trace (top) of MscS reconstituted into branched lipids with the corresponding pressure trace (bottom). A more detailed description and control is given in the SI (Figure S8).

Do short chain phospholipids modulate MscS structure?

Previously, mass spectrometry revealed the presence of short-chain phospholipids in the purified MscS protein-detergent complex[32]. In particular, PG C30:1, PE C14:0/C14:0 and PE C16:1/C14:0 were identified. These lipids are at low abundance in E. coli membranes[55]. Other studies have implied conformational changes in the large mechanosensitive channel, MscL, induced by reconstitution in short-chain phospholipids[56]. The ability of short-chain phospholipids to bind preferentially to MscS was, therefore, investigated. Purified MscS A119W and L111W channels were reconstituted in mixtures of BrPC (diBr C18) and either C14:1or C18:1 and the fluorescence properties determined. Preferential binding of the C14:1/C14:1 lipid would be evident as reduced quenching by the brominated lipid. However, no significant difference in quenching was observed between C14:1 and C18:1 phospholipids with a relative quenching constant of KC14/C18 = 0.9±0.1 for A119W (Figure S9a,b). A notable effect of C14:1 lipids, however, was a change in the quantum yield for A119W. Normalising the fluorescence intensity for A119W to protein concentration, revealed an ~20% lowering of this parameter for protein reconstituted in PC C14:1/C14:1 compared with PC C18:1/C18:1 (Figure S9c). No change in quantum yield was observed in experiments with L111W (Figure S9d). These data are consistent with conformational changes, possibly as a result of membrane thinning in PC C14:1/C14:1 bilayers.

The role of Arg46 and Arg59 in gating MscS

TM1 and TM2 are notable for transmembrane helices by the presence of basic residues Arg46, Arg59 and Arg74[34, 57, 58]. Positioning of the bilayer lipids on TM1 and in the pockets may be fine regulated by charges on the sensor paddles. Indeed these residues are critical in defining the lipid exposed region of MscS using the OPM modelling[36]. Thus, we sought to investigate mutants in which the charges were neutralised. Previous work established that R46N mutants exhibited essentially wild type behaviour[57]. Insertion of a hydrophobic residue (Leu) at this position (R46L) caused the channel to be more difficult to gate (PL/PS = 1.13±0.04) without significantly affecting either the conductance or the stability of the open state (Figure S10a). Conversely, substitution of R59 by leucine caused a strong GOF phenotype that manifested as a PL/PS ratio = 2.05±0.10 in patch clamp analysis (Figure S10a) and growth inhibition during expression (Figure S10c). Thus, replacement of Arg residues 46 and 59 by Leu significantly affects the tension sensing of the resultant channels.

Mutations in TM3b modulate gating and open state stability

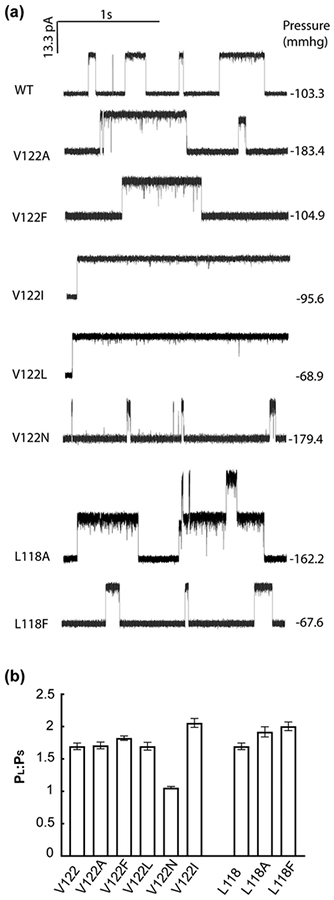

TM3b is a relatively well-conserved amphipathic helix (Figure S2) in which the hydrophobic residues are orientated into the proposed pocket and the hydrophilic residues orientated to the β domain. Our Trp mutations on TM3b led to significant changes in channel activity in physiological assays (Figure S3–4), suggesting that either the bulk or the polarity of the side chain impaired channel function. Work by others has also established the sensitivity of this helix to mutagenesis with amino acid replacements causing altered gating and stability of MscS[59–61]. To extend this analysis we selected three positions in native MscS to mutate to alternative residues to complement the Trp mutations in this study (Figure S11). Residues L118, V122 and M126 are on the same face of the helix as the Trp residues and we changed either charge or the volume of the residue. Polar insertions at position 118, 122 and 126 caused impaired channel activity in downshock assays (Figure S11a). In electrophysiological assays, no channels were observed for L118Q and M126R despite good expression of both proteins (Figure S11b). The V122N channel opened at pressures similar to those that gated MscL (Table S2; Figure 5) and channel openings were of short duration (Figure 5). Hydrophobic substitutions at positions 118 and 122 also created channels with substantially modified behaviour (Figure 5 & S12). Both L118A and L118F exhibited increased pressure sensitivity but exhibited essentially normal conductance and openings[61]. Similarly, V122F and V122A mutants exhibited only modest changes in channel properties (Figure 5 & Table S2). In contrast, V122L and V122I, exhibited wild type and increased pressure sensitivity, respectively (Table S2), but exhibited a sustained open state that did not close upon sustained stimuli as rapidly as the wild type (Figure S12). Thus, subtle changes in side chain structure at V122 modulate channel behaviour.

Figure 5. Electrophysiological characterization of mutants at highly conserved positions in TM3b.

(a) Representative traces of single-substituted mutants of V122 and L118 in E. coli MscS. A scale bar is presented at top left of the traces. Note that absolute pressure values at which channels open differ between patches due to variation in patch geometry. Therefore, an internal reference, MscL channel opening, is used as a reference and the ratio expressed as PL:PS, which is ~1.5 for wild type MscS channels. (b) summary of PL:PS values for the TM3b mutants.

Discussion

Lipid-protein interactions are often difficult to investigate. Elegant analyses by Marsh have shown that, for the majority of membrane proteins, lipid head group packing against the surface of the protein defines the number of lipids immediately surrounding the protein complex[11, 40, 62]. Recent work has shown that hydrogen networks between lipid headgroups and polar residues determine the protein conformation[3, 13]. However, both MscS and MscL are inhibited by insertion of polar residues at the periphery of the protein close to the lipid headgroups[63, 64]. Indeed, MscS has a distinctly asymmetric distribution of charged and polar residues in TM1 and TM2, the helix pair that have the potential to interact directly with lipids (Figure S1c; see below). Our analysis suggests that the surface of MscS between residues 21 and 47 is buried in the lipid bilayer, as predicted by the OPM model for a simple planar bilayer. Brominated lipids quench Trp residues positioned from 21 to 47 of TM1, consistent with a hydrophobic depth of 30 Å[46], with the centre around residue 32–36 (Figure 2). I57W, which lies close to the TM1–2 turn, appears to be predominantly in an aqueous environment. However, lipid chains can interact with I150 and the surface of TM3b, which lie below I57W and distant to the planar bilayer contact zone. These data would support a model for the lipid-protein interactions in which a distortion or bulge of the phospholipids occurs, which was predicted for MscS[65] and reported for the mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel[12, 66] (see below).

Lipid chains have great fluidity and will tend to fill crevices in the lipid-exposed surfaces of a membrane protein. The molecular dimensions of the TM1–2 paddles of MscS, and their mobility, create variable crevices into which lipid chains can insert (Figure 1). Viewing molecular models of MscS one can see a clear pocket in the structure that exposes L111 to the environment (Figure 1b). This pocket is lined with the hydrophobic residues of TM3b and terminates with F127, F151 and I150 (Figure 1b & Figure S1b). The data presented here are consistent with deep penetration of the pockets by lipid chains (Figures 3). The position-dependent quenching data (Figure 3a & Table S1) are consistent with the negatively charged phosphate group of the phospholipid at the last turn of TM3b close to F127. Similarly, the quenching of a I150W, F127W and F151W indicate lipid chains freely access the volume immediately above TM3b in the pockets of MscS (Figure 1c). This is clearly inconsistent with a simple planar bilayer as envisaged by the OPM model. The two possibilities are compatible with some distortion of the bilayer, as recently seen with Piezo[12, 66]. One of the fascinating features of MscS is that the distribution of charged or polar residues in the TM1 and TM2 helices that can potentially interact with the lipid bilayer are asymmetrically distributed – there are few on the periplasmic ends of the helices and many on the cytoplasmic ends (Figure S1c). Further, insertion of polar residues at the periplasmic ends of TM1 decreases the sensitivity to membrane tension (i.e. making the channels less active)[63], which would be compatible with the cytoplasmic and periplasmic ends of TM1 having very different lipid packing. A simple explanation for the cluster of polar residues at the cytoplasmic ends of TM1 and TM2 would be that they organize the headgroups of the ‘non-simple bilayer’ lipids to ensure the pockets are occupied by lipid chains.

The presence of basic residues in TM1 and TM2 was highlighted as an unusual feature of this membrane protein and it was proposed that this might lead to voltage sensing[34]. Significant doubt has been cast on this role for the Arg residues in TM1[57]. However, our data does point to a critical role for these residues in gating since neutralisation of the charges (R46L and R59L) has profound, but opposite, effects on channel gating (Figure S10). It seems plausible that these mutations perturb the headgroup interaction with MscS and may affect lipid packing or orientation in the pockets. It is notable either Asp or Glu can replace Arg, suggesting that the capacity to interact with headgroups of lipids is important. The change from a hydrophilic to hydrophobic residue at R46 and R59 could have a more profound impact in such a scenario.

Conservation of the hydrophobic TM3b surface is clearly important, but our study also suggests further complexity. Not only do single polar residues cause profound loss of activity (Table S2 and Figures 5) but relatively conservative changes that preserve the hydrophobicity affect the rate of loss of channel activity during sustained stimulus (Figure 5, Table S2 & Figure S12) (See also[59–61, 67]). Val122 may have a critical role in gating. Introduction of other hydrophobic residues by mutation causes major changes in tension sensing and open stability (Figure 5). These effects of mutations at Val122 are reminiscent of substitutions at Leu 596 in TrpV4[68]. In the TrpV4 study, mutations that decreased the hydrophobicity caused loss of function and this effect was speculated to arise from the modified lipid interactions. Intriguingly, TrpV4 L596I was a gain-of-function mutant. The only structural change in the mutants was the organisation of the methyl groups on the respective amino acid side chains, with the consequence that the substituted amino acid side chain is buried more deeply in the bilayer[68, 69]. In MscS the profound change in character from Val122 to Leu or Ile may similarly relate to the organisation of the side chain (indeed even replacement of Leu with Ala causes a change in rate at which channels closed upon continued stimulus (tension-insensitive inactivated state[70]; Table S2 & Figure S11).

Our analysis of MscS-lipid interactions provides insights and poses new questions. Previously, Trp16 in the native MscS has been shown to be important for tension-sensing[47]. This residue, we have shown here, is likely to be buried in the periplasmic leaflet of the bilayer (Figure 2). The periplasmic mouth of the MscS pore lies well below the surface of the planar bilayer, indeed close to the centre of the bilayer. Correspondingly, the hydrophobic pocket lies adjacent to and below the cytoplasmic leaflet of the bilayer. One is consistently drawn to the idea that there is deformation of the bilayer at the cytoplasmic surface, as in the case of Piezo1[12]. In the latter case the deformation amplifies the sensitivity of the channel to membrane tension. The effects of mutations in TM1 (R46L and R59L) and in TM3b on tension sensitivity and the stability of the open state would fit with a role for these structural elements in stabilising the deformation. It is exciting to note that the pattern of critical penetration of the channel structure by lipids is now becoming a common mechanistic element[68, 69] and may be the site of action of lipophilic drugs[71]. The analogies of the effects of V122 mutations to the dependence of the mechanism of TrpV4 on specific side chain structures is supportive of commonality in mechanistic features. Our data and those of Malcolm et al., [61] identified residues in TM3b where even subtle changes affect the critical properties of the channel. This is also seen from the influence of reconstitution of the channel into branched-chain lipids, which led to sustained gating events after pressure had been released (Figure 4). Thus, the dimensions of the relationship between lipids and MscS structure outstrip the simple planar bilayer evident in parts of TM1 and extend to the lipids that occupy the pockets.

Methods

Materials

Dodecylmaltoside (DDM) was obtained from Glycon (Germany). The phospholipids 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-di-(9Z-tetradecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC C14:1/C14:1), 1-oleoyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(6,7-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (6.7BrPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(9,10-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (9.10BrPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(11,12-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (11.12BrPC) and 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (4Me-16:0-PC) were purchased from Avanti (Alabaster). DOPC was brominated as described earlier[32, 72] resulting in 1,2-di-(9,10-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (BrPC). 4,5 (4.5BrFA), 9,10 (9.10BrFA), and 15,16 (15.16BrFA) dibromopalmitic acid were synthesised as described in the SI. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma.

Mutagenesis and functional assays

As template for all Trp substitution mutants in this study the tryptophan-free MscS W16Y/W240F/W251F in a pTrc99A expression vector was used which has been proven stable and functional[47]. Mutants were made with the Stratagene QuikChange protocol and were confirmed by sequencing (Source Bioscience, Nottingham). As functional assay for the mutant forms of MscS a hypo-osmotic downshock was performed as described earlier[49, 73]. For this MscS constructs were transformed into E. coli strain MJF612 (Frag1 ΔmscL::cm, ΔmscS, ΔmscK::kan, ΔybdG::apr)[74] and grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5g/L NaCl, 5 g/L yeast extract) containing additional 0.5 M NaCl at 37°C. At an OD650 = 0.2 until 0.3 expression was induced with 0.3 mM IPTG in parallel with noninduced samples. Samples were then 10 times diluted into LB medium (shock medium) as well as LB-medium + 0.5 M NaCl (control medium). After incubation for 10 min at 37°C, serial dilutions were made and spread on agar plates made form control or shock medium, respectively. Colonies were counted after incubation overnight at 37°C and percent survival were calculated relative to the control plates.

The Arg substitution mutants were created in a wild-type clone of mscS in the same pTrc99A expression vector used for the mutants described above[73]. These mutants were analysed functionally as previously described using strain MJF641 as the host and with a downshock from LB + 0.3 M NaCl to LB medium[49].

Purification of MscS

MscS, solubilised in 1% DDM, was purified as described previously[43, 47, 75] in a 2-step purification. The C-terminal His6-tag was bound by a nickel-nitrilotriacetic (Ni-NTA) agarose column in the first step. MscS was further purified and the heptameric complex was separated by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) with a buffer containing 0.03% DDM, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl.

Reconstitution for electrophysiology

Liposomes with a branched lipid (1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 4Me-16:0-PC) were made using a sucrose method [76]. Briefly, 2 mg of the lipid in chloroform was dried under N2. The lipid film was rehydrated with 1 ml of 0.4 M sucrose and incubated for 3 h at 45°C. Purified MscSWT was added to achieve a protein : lipid ratio (mol complex : mol lipid) of 1:500, and the solution shaken gently for 3 h at room temperature. Then about 200 mg biobeads (Anatrace) were added to the mixture and gently shaken overnight.

Electrophysiology

Giant spheroplasts from E. coli M429 strain (Frag1, ΔmscS, ΔmscK::kan) transformed with MscS constructs in pTrc 99A vector, whose express was induced with 1.3 mM IPTG, were generated and used in patch-clamp recordings as described previously[51, 77]. Excised, inside-out patches were examined at room temperature. Patch buffers used contained 200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with pH adjusted to 8.0. Data were acquired at a sampling rate of 20 kHz with a 5-kHz filter, using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier in conjunction with Axoscope software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). A piezoelectric pressure transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) was used to monitor the pressure introduced to patch membrane by suction throughout the experiments. Data analysis were performed using Clampfit 10.6 (Axon Instruments). Identical conditions were used to analyse purified channels reconstituted into lipids.

Reconstitution and fluorescence spectroscopy

Purified MscS was reconstituted by dilution of mixtures of MscS, lipids and detergent under the critical micellar concentration as described earlier[32]. Different variants of phosphatidylcholine, as listed in materials and specified in the result section, were used. Films of 2 μmol lipids were formed from chloroform solutions in thin-walled glass tubes using a nitrogen stream and then desiccation overnight at 4 °C. Lipids were suspended in 1.6 ml reconstitution buffer containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, and 15 mM sodium cholate by warming the tube for 20 s in warm water, vortexing for 5 min, and subjecting to ultrasonication for 10 min (Fisher Scientific, model FB15046). 0.64 nmol MscS (monomer) was then mixed with 50 μl of lipid solution (64 nmol) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Reconstitution from cholate by dilution gives a homogeneous mixture of lipid and protein in the form of large membrane vesicles [78], which was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure S5).

For assay 30 μl of this mixture was then added to 600 μl of measuring buffer (as reconstitution buffer but without sodium cholate) in a stirred quartz cell (4×4 mm light path; Hellma). After 5 min incubation at 20°C, fluorescence measurements were started in a FLS920 spectrometer (Edinburgh Instruments) with an excitation wavelength of 295 nm (slit width 3 nm) and an emission range from 300–420 nm (slit width 7 nm) and excitation and emission polarizers set to 90° and 0°, respectively. Spectra were corrected by similar samples containing only lipids but no MscS. Experiments with brominated and non-brominated lipids at different ratios were prepared as follows[72]: Solubilised solutions of the required lipids were made up as described above. Then 100 μl each of brominated and non-brominated lipids mixtures at different mol-ratios were prepared and incubated for 30 min at 50 °C with gentle shacking. After cooling to room temperature 50 μl of each lipid mixture was mixed with MscS and the experiment proceeded as described above.

Mixtures of cardiolipin or cholesterol with BrPC were made by mixing the chloroform solutions to result in a lipid films of 2 μmol and 33% (mol/mol total lipid), respectively. Solubilised mixtures of these lipids were then made as described for the pure lipids above. To study the effect of bromination at different positions along the fatty acid chains, 6.7BrPC, 9.10BrPC, and 11.12BrPC were used together with POPC as non-brominated reference. The brominated fatty acids 4,5 (4.5BrFA), 9,10 (9.10BrFA), and 15,16 (15.16BrFA) dibromopalmitic acid were synthesised as described in SI and added as stock solutions in methanol to MscS mutants L111W, A119W, and L123W reconstituted in DOPC. Fluorescence emission spectra before and after addition were recorded and compared. The final concentration of methanol was below 1%. As controls non-brominated palmitic acid or the solvent only were added.

Analysis of fluorescence experiments

Fractional quenching was determined as FrQ = (F0 – F)/F0, where F0 is the fluorescence intensity at 340 nm for the sample containing 100% non-brominated lipids, and F is the intensity for the sample containing 100% brominated lipids.

Data of fluorescence experiments in lipid mixtures were analysed following the procedures developed by Lee and co-workers[72]:

Relative fluorescence intensities, F, were plotted against the mole fraction of brominated lipids, xBr, and fitted with following equation using the software Origin 8.0:

In this equation Fmin is the fluorescence intensity in BrPC while n is the number of lattice sites for binding of lipids close enough to the fluorescence probe to cause quenching. These parameters were fitted. Using n determined from experiments in mixtures of DOPC and BrPC, the relative binding constant, KC14/C18, for the short chain lipid PC C14:1/C14:1 was fitted with following equation:

Electron microscopy

Purified MscS WT was reconstituted as described in the reconstitution for fluorescence spectroscopy section. The sample was then incubated for 1 min on carbon coated copper grids (400 mesh, Plano, Germany) which were beforehand freshly glow discharged. The excess was removed with a filter paper and the grid was then washed three times with water and three times with 2 % uranyl acetate. The last cycle of staining solution was left for 5 min on the grid and was then removed with filter paper. After drying the grids were imaged in a FEI Tecnai T12 Spirit transmission electron microscope equipped with an Eagle detector at 120 kV. A magnification of 52000, a defocus of 1 μm, and a total electron dose of 30 electrons/Å2 was used.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

MscS tension-sensing relies on dynamic molecular interactions with lipids

branched lipids or protein mutations that change these interactions modify gating

lipids can penetrate in pockets deep within MscS by changing orientation

tryptophan fluorescence quenching defined bilayer lipid interactions with MscS

MscS deforms the shape of the membrane in a manner similar to Piezo1

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Tony Lee (Southampton) and Jim Naismith (St Andrews and Oxford) for helpful discussions. IRB, SM, AR, TR, SB were supported by a Wellcome Programme Grant (WT092552MA); HG and CK were funded by the EU FP7 ITN programme NICHE. The MscS F151W mutant was created by N. J. Hayward during his PhD studies at the University of Aberdeen. We thank Vanessa Flegler for assistance in the electron microscopy experiment. IRB was a recipient of a Leverhulme Emeritus Research Fellowship and a CEMI research grant from Caltech; PB was supported by Grant I-1420 of the Welch Foundation and Grant GM121780 from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funding organizations.

Abbreviations:

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPC

1-oleoyl-2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- BrPC

1,2-di-(9,10-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- 6.7BrPC

(1-palmitoyl-2-(6,7-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- 9.10BrPC

1-palmitoyl-2-(9,10-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- 11.12BrPC

1-palmitoyl-2-(11,12-dibromo)stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- Chol

cholesterol

- PL

phospholipid

- CL

cardiolipin

- 4Me-16:0-PC

1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- 4.5BrFA

4,5 dibromopalmitic acid

- 9.10BrFA

9,10 dibromopalmitic acid

- 15.16BrFA

15,16 dibromopalmitic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests: the authors are not aware of any competing interests affecting this work.

References

- [1].Cymer F, von Heijne G, White SH. Mechanisms of integral membrane protein insertion and folding. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:999–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lee AG. How lipids and proteins interact in a membrane: a molecular approach. Mol Biosyst. 2005;1:203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Martens C, Shekhar M, Borysik AJ, Lau AM, Reading E, Tajkhorshid E, et al. Direct protein-lipid interactions shape the conformational landscape of secondary transporters. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Powl AM, East JM, Lee AG. Lipid-protein interactions studied by introduction of a tryptophan residue: The mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14306–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Powl AM, Wright JN, East JM, Lee AG. Identification of the hydrophobic thickness of a membrane protein using fluorescence spectroscopy: studies with the mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5713–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Marsh D. Lipid-protein interactions and heterogeneous lipid distribution in membranes. Mol Membr Biol. 1995;12:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marsh D. Lipid interactions with transmembrane proteins. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2003;60:1575–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marsh D, Pali T. The protein-lipid interface: perspectives from magnetic resonance and crystal structures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:118–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pali T, Bashtovyy D, Marsh D. Stoichiometry of lipid interactions with transmembrane proteins--Deduced from the 3D structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1153–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marsh D. Energetics of hydrophobic matching in lipid-protein interactions. Biophys J. 2008;94:3996–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Marsh D, Pali T. Orientation and conformation of lipids in crystals of transmembrane proteins. Eur Biophys J. 2013;42:119–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haselwandter CA, MacKinnon R. Piezo’s membrane footprint and its contribution to mechanosensitivity. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Martens C, Stein RA, Masureel M, Roth A, Mishra S, Dawaliby R, et al. Lipids modulate the conformational dynamics of a secondary multidrug transporter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:744–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marsh D, Horvath LI. Structure, dynamics and composition of the lipid-protein interface. Perspectives from spin-labelling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376:267–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sukharev SI, Blount P, Martinac B, Blattner FR, Kung C. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368:265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sukharev SI, Sigurdson WJ, Kung C, Sachs F. Energetic and spatial parameters for gating of the bacterial large conductance mechanosensitive channel, MscL. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:525–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Teng J, Loukin S, Anishkin A, Kung C. The force-from-lipid (FFL) principle of mechanosensitivity, at large and in elements. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Booth IR, Blount P. The MscS and MscL families of mechanosensitive channels act as microbial emergency release valves. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:4802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cox CD, Bavi N, Martinac B. Bacterial Mechanosensors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018;80:71–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kung C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature. 2005;436:647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bialecka-Fornal M, Lee HJ, Phillips R. The rate of osmotic downshock determines the survival probability of bacterial mechanosensitive channel mutants. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Booth IR, Miller S, Rasmussen A, Rasmussen T, Edwards MD. Mechanosensitive channels: their mechanisms and roles in preserving bacterial ultrastructure during adaptation to environmental change In: El-Sharoud W, editor. Bacterial Physiology a Molecular Approach. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2008. p. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Reuter M, Hayward NJ, Black SS, Miller S, Dryden DT, Booth IR. Mechanosensitive channels and bacterial cell wall integrity: does life end with a bang or a whimper? J R Soc Interface. 2014;11:20130850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boer M, Anishkin A, Sukharev S. Adaptive MscS gating in the osmotic permeability response in E. coli: the question of time. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Booth IR. Bacterial mechanosensitive channels: progress towards an understanding of their roles in cell physiology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;18:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Booth IR, Rasmussen T, Edwards MD, Black S, Rasmussen A, Bartlett W, et al. Sensing bilayer tension: bacterial mechanosensitive channels and their gating mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Martinac B, Adler J, Kung C. Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature. 1990;348:261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nguyen T, Clare B, Guo W, Martinac B. The effects of parabens on the mechanosensitive channels of E. coli. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nomura T, Cranfield CG, Deplazes E, Owen DM, Macmillan A, Battle AR, et al. Differential effects of lipids and lyso-lipids on the mechanosensitivity of the mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8770–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ridone P, Grage SL, Patkunarajah A, Battle AR, Ulrich AS, Martinac B. “Force-from-lipids” gating of mechanosensitive channels modulated by PUFAs. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;79:158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Naismith JH, Booth IR. Bacterial Mechanosensitive Channels-MscS: Evolution’s Solution to Creating Sensitivity in Function. Annual review of biophysics. 2012;41:157–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pliotas C, Dahl AC, Rasmussen T, Mahendran KR, Smith TK, Marius P, et al. The role of lipids in mechanosensation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:991–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bavi N, Cox CD, Perozo E, Martinac B. Toward a structural blueprint for bilayer-mediated channel mechanosensitivity. Channels (Austin). 2017;11:91–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bass RB, Strop P, Barclay M, Rees DC. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli MscS, a voltage-modulated and mechanosensitive channel. Science. 2002;298:1582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wang W, Black SS, Edwards MD, Miller S, Morrison EL, Bartlett W, et al. The structure of an open form of an E. coli mechanosensitive channel at 3.45 A resolution. Science. 2008;321:1179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lomize MA, Pogozheva ID, Joo H, Mosberg HI, Lomize AL. OPM database and PPM web server: resources for positioning of proteins in membranes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].East JM, Lee AG. Lipid selectivity of the calcium and magnesium ion dependent adenosinetriphosphatase, studied with fluorescence quenching by a brominated phospholipid. Biochemistry. 1982;21:4144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Powl AM, Carney J, Marius P, East JM, Lee AG. Lipid interactions with bacterial channels: fluorescence studies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:905–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Marsh D. Application of electron spin resonance for investigating peptide-lipid interactions, and correlation with thermodynamics. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Marsh D. Electron spin resonance in membrane research: protein-lipid interactions. Methods. 2008;46:83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Petrache HI, Dodd SW, Brown MF. Area per lipid and acyl length distributions in fluid phosphatidylcholines determined by (2)H NMR spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2000;79:3172–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bolen EJ, Holloway PW. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by brominated phospholipid. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rasmussen T, Rasmussen A, Singh S, Galbiati H, Edwards MD, Miller S, et al. Properties of the Mechanosensitive Channel MscS Pore Revealed by Tryptophan Scanning Mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2015;54:4519–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Killian JA, von Heijne G. How proteins adapt to a membrane-water interface. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000;25:429–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].White SH, Wimley WC. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376:339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rasmussen A, Rasmussen T, Edwards MD, Schauer D, Schumann U, Miller S, et al. The Role of Tryptophan Residues in the Function and Stability of the Mechanosensitive Channel MscS from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Anishkin A, Akitake B, Sukharev S. Characterization of the resting MscS: modeling and analysis of the closed bacterial mechanosensitive channel of small conductance. Biophys J. 2008;94:1252–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Edwards MD, Li Y, Kim S, Miller S, Bartlett W, Black S, et al. Pivotal role of the glycine-rich TM3 helix in gating the MscS mechanosensitive channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhang YM, Rock CO. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:222–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Martinac B, Adler J, Kung C. Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature. 1990;348:261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Romantsov T, Guan Z, Wood JM. Cardiolipin and the osmotic stress responses of bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Toledo A, Huang Z, Coleman JL, London E, Benach JL. Lipid rafts can form in the inner and outer membranes of Borrelia burgdorferi and have different properties and associated proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2018;108:63–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Brohawn SG, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Physical mechanism for gating and mechanosensitivity of the human TRAAK K+ channel. Nature. 2014;516:126–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Oursel D, Loutelier-Bourhis C, Orange N, Chevalier S, Norris V, Lange CM. Lipid composition of membranes of Escherichia coli by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry using negative electrospray ionization. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:1721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Perozo E, Rees DC. Structure and mechanism in prokaryotic mechanosensitive channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:432–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Nomura T, Sokabe M, Yoshimura K. Voltage-Dependent Inactivation of MscS Occurs Independently of the Positively Charged Residues in the Transmembrane Domain. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:2401657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ulmschneider MB, Ulmschneider JP, Freites JA, von Heijne G, Tobias DJ, White SH. Transmembrane helices containing a charged arginine are thermodynamically stable. Eur Biophys J. 2017;46:627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Akitake B, Anishkin A, Liu N, Sukharev S. Straightening and sequential buckling of the pore-lining helices define the gating cycle of MscS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Koprowski P, Grajkowski W, Isacoff EY, Kubalski A. Genetic screen for potassium leaky small mechanosensitive channels (MscS) in Escherichia coli: recognition of cytoplasmic beta domain as a new gating element. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:877–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Malcolm HR, Blount P. Mutations in a Conserved Domain of E. coli MscS to the Most Conserved Superfamily Residue Leads to Kinetic Changes. PloS one. 2015;10:e0136756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Marsh D. Electron spin resonance in membrane research: protein-lipid interactions from challenging beginnings to state of the art. Eur Biophys J. 2010;39:513–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nomura T, Sokabe M, Yoshimura K. Lipid-protein interaction of the MscS mechanosensitive channel examined by scanning mutagenesis. Biophys J. 2006;91:2874–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Yoshimura K, Nomura T, Sokabe M. Loss-of-function mutations at the rim of the funnel of mechanosensitive channel MscL. Biophys J. 2004;86:2113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Phillips R, Ursell T, Wiggins P, Sens P. Emerging roles for lipids in shaping membrane-protein function. Nature. 2009;459:379–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Guo YR, MacKinnon R. Structure-based membrane dome mechanism for Piezo mechanosensitivity. Elife. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Belyy V, Anishkin A, Kamaraju K, Liu N, Sukharev S. The tension-transmitting ‘clutch’ in the mechanosensitive channel MscS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:451–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Teng J, Loukin SH, Anishkin A, Kung C. A competing hydrophobic tug on L596 to the membrane core unlatches S4–S5 linker elbow from TRP helix and allows TRPV4 channel to open. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:11847–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Teng J, Loukin SH, Anishkin A, Kung C. L596-W733 bond between the start of the S4–S5 linker and the TRP box stabilizes the closed state of TRPV4 channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3386–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Akitake B, Anishkin A, Sukharev S. The “dashpot” mechanism of stretch-dependent gating in MscS. J Gen Physiol. 2005;125:143–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Dong YY, Pike AC, Mackenzie A, McClenaghan C, Aryal P, Dong L, et al. K2P channel gating mechanisms revealed by structures of TREK-2 and a complex with Prozac. Science. 2015;347:1256–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Carney J, East JM, Mall S, Marius P, Powl AM, Wright JN, et al. Fluorescence quenching methods to study lipid-protein interactions. Current protocols in protein science / editorial board, John E Coligan [et al]. 2006;Chapter 19:Unit 19 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Miller S, Edwards MD, Ozdemir C, Booth IR. The closed structure of the MscS mechanosensitive channel - Cross-linking of single cysteine mutants. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32246–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Schumann U, Edwards MD, Rasmussen T, Bartlett W, van West P, Booth IR. YbdG in Escherichia coli is a threshold-setting mechanosensitive channel with MscM activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12664–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rasmussen T, Edwards MD, Black SS, Rasmussen A, Miller S, Booth IR. Tryptophan in the pore of the mechanosensitive channel MscS: assessment of pore conformations by fluorescence spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Battle AR, Petrov E, Pal P, Martinac B. Rapid and improved reconstitution of bacterial mechanosensitive ion channel proteins MscS and MscL into liposomes using a modified sucrose method. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Blount P, Sukharev SI, Moe PC, Martinac B, Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1999;294:458–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pilot JD, East JM, Lee AG. Effects of bilayer thickness on the activity of diacylglycerol kinase of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.