Abstract

This work reports the preparation, characterization, and O2/N2 separation properties of composite membranes based on the polymer of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1) and the zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8). Especially, the composite membranes were prepared by growing ZIF-8 nanoparticles on one side of the PIM-1 membrane in methanol. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and thermo-gravimetric analysis indicated that there is no strong chemical interaction between ZIF-8 nanoparticles and PIM-1 chains. Scanning electron microscopy images showed that ZIF-8 nanoparticles adhere well to the PIM-1 membrane surface. The pure-gas permeation results confirmed that growth of ZIF-8 on the PIM-1 membrane can enhance the performance of O2/N2 separation. Particularly, the O2/N2 separation performance of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane exceeds the Robeson upper bound line.

Introduction

In the past decades, membrane-based air separation to produce oxygen has been of special interest for chemists because of the versatile applications in furnace air enrichment, fuel cells, medical respiration, and so on.1−3 The polymer of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1) is one of the most potential materials for air separation as it shows unusually high O2 permeability and moderate O2/N2 selectivity. Nevertheless, PIM-1 membrane separation performance is still limited by the trade-off relationship between permeability and selectivity.4,5 Mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) afford the opportunity to break the performance limitation by adding the filler to PIM-1.6,7 With different metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) introduced into PIM-1, the corresponding MMMs have shown excellent gas separation performance.8−10 Particularly, the MMM based on PIM-1 and zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8), the O2 and N2 permeability were increased by 190 and 94%, respectively; meanwhile, the O2/N2 selectivity was increased by 50%.11 However, the poor compatibility between polymer substrates and MOF particles usually leads to nonuniform distribution of particles, especially for MMMs with high filler loading, and it may cause agglomeration and poor mechanical properties.12−14 Such a defective polymer–filler interface induces nonselective voids, which will affect gas separation performance.

Recently, a new strategy to improve the polymer–filler interface by growing MOF particles on membranes has been reported.15−17 Growing ZIF-8 particles on the surface of membranes has exhibited potential application in gas separation. Téllez et al. crystallized a thick continuous ZIF-8 membrane on highly porous flexible polysulfone, and the ZIF-8/polysulfone composite membrane showed a high H2 separation performance.18 Wang et al. deposited an ultrathin ZIF-8 membrane on bromomethylated poly(2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide) (BPPO) after being modified with ethylene diamine, and the resulting ZIF-8/ED-modified BPPO composite membrane exhibited a significantly high H2 permeability.19 Jansen and Budd et al. reported that growing ZIF-8 particles on the PIM-1 membrane in water could enhance O2/N2 selectivity. However, the O2/N2 separation performance could not exceed the Robeson upper bound line because of the low O2 permeability.20

In this work, we aimed to improve the performance of the composite membrane in O2/N2 separation. Because the methanol-treated PIM-1 membrane often results in a significant increase in permeability,21 we proposed using methanol as the solvent for the preparation of the PIM-1/ZIF-8 composite membrane will improve the O2/N2 separation performance. By growing ZIF-8 nanoparticles on one side of the PIM-1 membrane, a series of PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes were fabricated in methanol. Their structures, morphologies, and interactions of the composite membranes were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). O2 and N2 permeation properties of the resultant composite membranes were measured using a constant-volume/variable pressure method.

Results and Discussion

FT-IR, TGA, and BET

FT-IR spectra of ZIF-8, PIM-1 membrane, and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes are shown in Figure 1. The FT-IR spectrum of the PIM-1 membrane was identical to that reported in the literature.22 The absorption bands at 2860, 2930, and 2960 cm–1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of −CH3 groups. The absorption band at 2240 cm–1 is assigned to the stretching vibrations of −CN groups. The absorption band at 1600 cm–1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of −C=C– bonds. Compared with the ZIF-8 and PIM-1 membrane, no new peak is found in PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes, indicating that there is no strong chemical interaction between ZIF-8 particles and PIM-1 chains.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of ZIF-8, PIM-1 membrane, and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes.

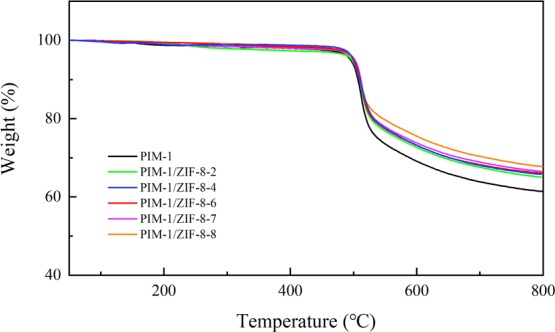

Thermal properties of the PIM-1 membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes were evaluated by TGA. As shown in Figure 2, the PIM-1 membrane exhibited high thermal stability and a single-step decomposition at about 480 °C. Thermal analysis of PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes indicated that ZIF-8 particles have no effect on their thermal stability, thus, PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes demonstrated excellent thermal stability as the PIM-1 membrane. The TGA curves also showed that the amount of ZIF-8 grew on the PIM-1 membrane could be increased by the repeating growth cycle. Meanwhile, there was no obvious weight loss over the temperature range of 50–200 °C for all the membranes, indicating that no residual solvent was trapped in their pores, which will affect the permeation properties of the membranes.

Figure 2.

TGA of PIM-1 and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes.

As shown in the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (Supporting Information, Figure S3), both the PIM-1 membrane and the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane exhibited type I isotherm, indicating most of the pores in these membranes are micropores.23 Compared with the surface area of the PIM-1 membrane (616 m2/g), the PIM/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane has a larger surface area (811 m2/g), which is distinctly higher than the surface area of most porous polymer networks.24 To further investigate the microporous structure of the PIM/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, pore size distributions were calculated by using the density function theory method. In the PIM/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, high pore volume proportion was observed for pores smaller than 2.5 nm, indicating that the membrane comprises significant amount of micropores. However, we found that there are obvious signals in the range of 2.5–10 nm, suggesting the existence of some mesopores. Figure 3 showed that the average pore diameter of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane is about 2.1 nm, which demonstrates the decreased porosity size of the composite membrane with respect to the PIM-1 membrane (2.8 nm).

Figure 3.

Pore size distributions determined from BET, (a) PIM-1 membrane, (b) PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane.

Morphologies of PIM-1/ZIF-8-X Composite Membranes

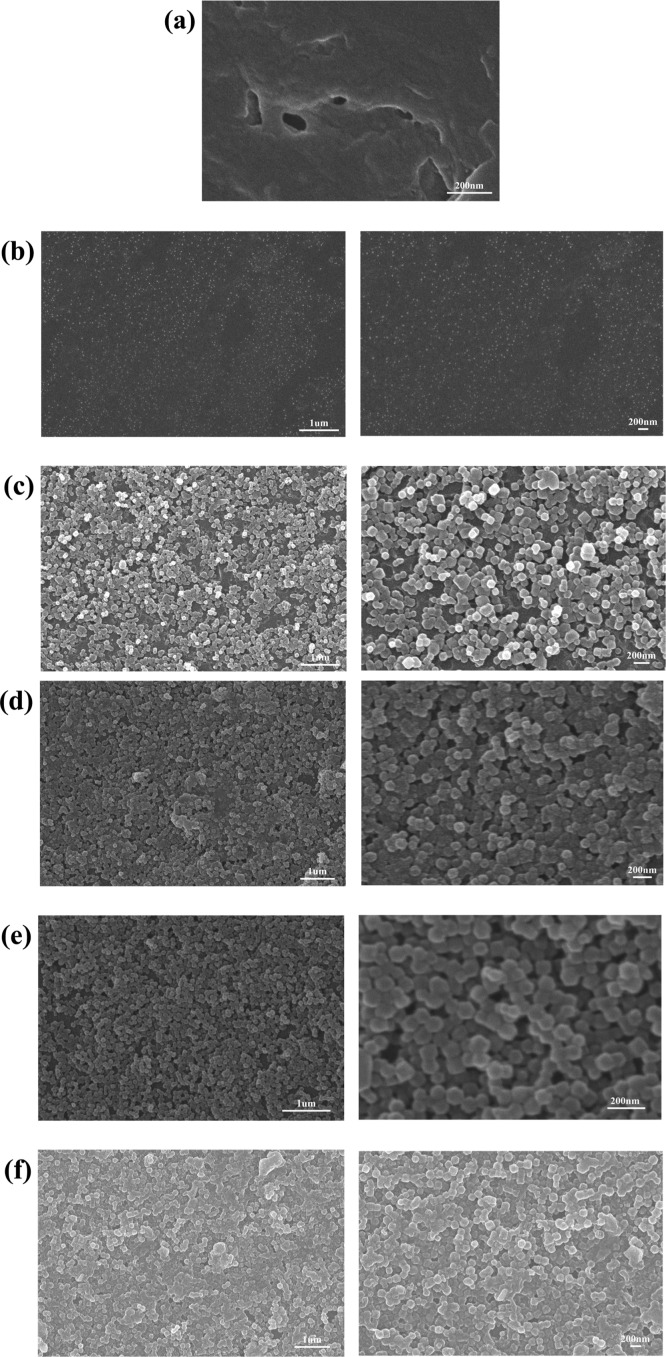

The SEM images of the PIM-1 membrane and PIM/ZIF-8-X composite membranes are displayed in Figure 4. The SEM images showed ZIF-8 nanoparticles adhere well to the PIM-1 membrane, which can be attributed to the attraction between the PIM-1 membrane and the ZIF-8 particles. Ramsahye et al. reported that there is a preferential interaction between −CN groups (in PIM-1) and the −NH– groups (in ZIF-8).25 Small particles were observed on the PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 composite membrane, corresponding to the nucleation stage of ZIF-8 crystallization. By repeating the growth cycle, a ZIF-8 nano-particle layer was eventually formed on the PIM-1 membrane. The particle size distributions of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane estimated from the SEM images are shown in Supporting Information Figure S4.

Figure 4.

SEM images of (a) PIM-1 membrane, (b) PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 composite membrane, (c) PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 composite membrane, (d) PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 composite membrane, (e) PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, (f) PIM-1/ZIF-8-8 composite membrane.

The cross section of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane revealed that the ZIF-8 nano-particle layer is composed of intergrown crystals, which adhere to the surface of the PIM-1 membrane. The nanoparticle layer has a thickness of about 200 nm (Figure 5). No evident interface between the ZIF-8 nanoparticle layer and the PIM-1 membrane was observed, confirming that ZIF-8 adheres well on the PIM-1 membrane. Because only one side of the PIM-1 membrane was exposed to the ZIF-8 precursor solution, ZIF-8 nano-particles were selectively grown on one side of the PIM-1 membrane, resulting in a pizza-like composite membrane.

Figure 5.

Cross-section images of (a) PIM-1 membrane, (b,c) PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane (arrows point the ZIF-8 layer), (d) SEM image of the back side of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane.

Gas Permeation Properties

The performance of the PIM-1 membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes in terms of pure-gas permeabilities of O2 and N2 are summarized in Table 1. Ultrahigh free-volume glassy polymer has weak size-sieving ability, and the selectivity is usually dominated by solubility selectivity.26 The PIM-1 membrane displays a high oxygen solubility coefficient, a medium solubility selectivity, and a very low diffusivity selectivity. The PIM-1 membrane prepared in this work has an O2 permeability of 1808 Barrer and a N2 permeability of 702 Barrer, which are similar to the value reported by Guiver.27

Table 1. Averaged Permeabilities and Selectivities at 35 °C, for the PIM-1 Membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X Composite Membranes.

| permeability (Barrer) |

ideal selectivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| membranes | O2 | N2 | αO/N |

| PIM-1 | 1808 | 702 | 2.5 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 | 1667 | 618 | 2.7 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 | 1256 | 428 | 2.9 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 | 1140 | 349 | 3.3 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 | 1287 | 351 | 3.7 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-8 | 1272 | 457 | 2.8 |

As shown in Table 2, the PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 composite membrane exhibited slight decrease in the solubility coefficient for both O2 and N2, probably attributing to the addition of a small number of nucleation state ZIF-8 particles. Because the PIM-1 membrane has a microporous structure, ZIF-8 nanoparticles may be grown into some of the pores, resulting in a decrease of free volume in PIM-1. However, the addition of the nucleation state of ZIF-8 particles reduced the pore size of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 composite membrane, which induced an increase in O2/N2 diffusivity selectivity, making the PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 composite membrane to be slightly increased in O2/N2 selectivity.

Table 2. Diffusivity (10–7 cm2/s) and Solubility [10–1 cm3 (STP)/cm3 cmHg] Coefficients, Diffusivity Selectivity (αD) and Solubility Selectivity (αS) for the PIM-1 Membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X Composite Membranes.

| diffusivity |

αD | solubility |

αS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| membranes | O2 | N2 | O2/N2 | O2 | N2 | O2/N2 |

| PIM-1 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 2.0 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 2.5 |

| PIM-1/ZIF-8-8 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 3.2 |

Compared with gas permeation properties of the PIM-1 membrane, PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 and PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 composite membranes showed increase in O2/N2 selectivity. However, PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 and PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 composite membranes exhibited decrease in O2/N2 diffusivity selectivity. These could be explained by the further addition of ZIF-8 particles, which blocked up more cavities of the PIM-1 membrane, leading to reduced selective voids, and decreased sorption sites for O2 and N2. Robeson et al. reported that the solubility selectivity of A/B gas pair decreases with increasing of free volume when the A gas is larger in size than the B gas.28 It means that sorption sites are less available to larger gas molecules as the free volume decreases. Therefore, the solubility selectivity for O2/N2 increased as free volume decreased.

As shown in Table 2, N2 solubility coefficients of PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 and PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 composite membranes were decreased; however, there was no significant decrease in O2 solubility coefficients compared with that of the PIM-1 membrane. The kinetic diameters of O2 and N2 are 3.46 and 3.64 Å, respectively, which makes it very difficult to separate O2 or N2 from air by simple micropore-based sieving effects. Freeman reported that improving the solubility selectivity could perform beyond the Robeson upper-bound line.29 Therefore, the increases in O2/N2 selectivity of PIM-1/ZIF-8-4 and PIM-1/ZIF-8-6 composite membranes may be mainly attributed to the increases of solubility selectivity.

Regarding the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, both diffusivity selectivity and solubility selectivity of O2/N2 were increased, resulting in an increase in the selectivity. The increases of diffusivity selectivity for O2/N2 may be attributed to the reduction in the average pore size, finally leading to a higher O2/N2 selectivity. The PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane has an O2/N2 selectivity of 3.7 with an O2 permeability of 1287 Barrer.

For all PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes, the diffusivity coefficients of O2 and N2 are almost similar to that of the PIM-1 membrane. The slight decreases in permeability of all PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes are mainly due to the reduction of free volume. Additional growth cycle could not always enhance selectivity of the composite membrane. Compared with the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, the PIM-1/ZIF-8-8 composite membrane exhibited an obvious decrease in O2/N2 selectivity. The decrease of selectivity may be attributed to further growth of ZIF-8, which makes the composite membrane more size-selective.

Because the main objective of this work was to prepare high permeation membranes with enhanced selectivity, Figure 6 demonstrated the comparison between PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes and recently reported composite membranes. The O2 permeabilities of PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes are much higher than those of in the relevant literature.19 Moreover, the O2/N2 separation performance of ZIF-8/PIM-1-7 successfully exceeded the Robeson upper bound line.5

Figure 6.

Trade-off between O2 permeability and O2/N2 selectivity for the PIM-1 membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-X composite membranes relative to the Robeson upper-bound.

Conclusions

In this work, pizza-like composite membranes (PIM-1/ZIF-8-X) were prepared by growing ZIF-8 nano-particles on one side of the PIM-1 membrane. The resulting composite membranes have excellent thermal stability, large surface area, and microporous structures. Meanwhile, the ZIF-8 nanoparticles show good adhesion with the PIM-1 membrane. The composite membranes not only eliminate the polymer–filler interface voids but also exhibit high permeability for O2. The gas permeation properties of the composite membranes indicate that a proper ZIF-8 growth time could improve the O2/N2 separation performance. The PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane has an O2/N2 selectivity of 3.7, with an O2 permeability of 1287 Barrer. The separation performance of the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane successfully exceeds the Robeson upper bound line, indicating that the PIM-1/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane has excellent separation performance.

Experimental Section

Materials

All the reagents were purchased commercially. 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrahydroxy-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-1,1′-spirobisindance (TTSBI) and 1,4-dicyanotetrafluo-robenzene (DCTB) need further purification before use. TTSBI was recrystallized in methanol with the white powder collected by filtration and dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 48 h. DCTB was purified by vacuum sublimation at 145 °C. Both TTSBI and DCTB were kept in a desiccator for storage. All the solvents were dried with standard procedures and stored under nitrogen.

Synthesis of PIM-1

PIM-1 was synthesized by following the reported method.30 In a dry three-necked flask equipped with a Dean–Stark trap, TTSBI (10.2 g, 30.0 mmol) and DCTB (6.0 g, 30.0 mmol) were dissolved in DMAc (100.0 mL), and then, anhydrous K2CO3 (8.3 g, 60 mmol) was added. Air was removed from the flask four times by application of gentle vacuum and replacement with N2. The flask was moved to an oil bath preheated at 155 °C. Toluene (40 mL) was added when the solution became viscous after 2 min of stirring. The reaction was continued for 60 min and then the product was poured into methanol. The collected crude polymer was dissolved in chloroform and re-precipitated from methanol. The obtained polymer was refluxed for 6 h in deionized water and then dried under vacuum at 100 °C for 2 days, and the PIM-1 powder (13.2 g, yield = 85%) was kept in a desiccator for further analysis. As shown in Supporting Information Figure S1, 1H NMR of PIM-1 powder was identical to that reported in the literature.27 Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis results of PIM-1 powder are shown in Supporting Information Figure S2 and Table S1, Mw = 21.9 kg/mol, Mn = 90.4 kg/mol, Mw/Mn = 2.4 compared with polystyrene standards.

Fabrication of the PIM-1 Membrane

The PIM-1 membrane was prepared by casting 2 wt % PIM-1/chloroform solution onto a flat-bottomed glass Petri dish. The solvent was then allowed to evaporate slowly in order to form the membrane. The membrane was left for 2 days to complete solvent evaporation. Thereafter, the membrane was transferred to a vacuum oven and dried at 70 °C for 48 h to remove any residual solvent.

Fabrication of PIM-1/ZIF-8 Composite Membranes

The PIM-1 membrane was cut into a circular piece (approximately 2.8 cm in diameter, 70 μm thickness). It was fixed on the bottom, in a vial containing a mixture of two solutions, 2-methylimidazole (1.65 g, 20.1 mmol) in methanol (30 mL) and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.75 g, 2.37 mmol) in methanol (30 mL). The ZIF-8 growth solution was stirred (500 rpm) at ambient temperature. After 12 h, the membrane was removed from the vial and washed three times with methanol. To increase the amount of ZIF-8 crystallized on the PIM-1 membrane, the above growing process was repeated with freshly mixed solution of 2-methylimidazole and Zn(NO3)2·6H2O. The desired membrane (PIM-1/ZIF-8-X, X means growth cycle) was dried under vacuum at 70 °C for 24 h.

Characterization Techniques

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV400 spectrometer, and chemical shifts were reported in ppm relative to a tetramethylsilane standard. The chemical bonds were investigated using a FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet Magna-IR 750) at a scanning range from 4000 to 400 cm–1. The thermal degradation of the PIM-1 membrane and PIM-1/ZIF-8-X composite membranes were monitored by using a TA instrument with a 2050 thermo-gravimetric analyzer. The analyses were carried out with a rate of 10 °C/min at temperatures ranging from 50 to 800 °C, N2 was used as the purge gas and its flow rate was controlled at 50 mL/min. The BET surface area of membranes was measured with a Micro ASAP 2460 and the samples were degassed by heating at 120 °C. The surface morphologies of membrane samples were observed by a field emission SEM (Gemini SEM-500, Germany). Cross sections of membrane samples were fractured in liquid nitrogen and coated with platinum via sputtering before analysis.

Gas Permeation Measurements

The pure-gas permeabilities of O2 and N2 were measured by using a constant-volume/variable-pressure method at 35 °C. The membranes were degassed under vacuum at 80 °C overnight to remove dissolved gases and moisture. The results reported here are the average of three measurements. After degassing the whole apparatus, the membrane was mounted in a permeation cell. Then, permeate gas was introduced on the upstream side (with ZIF-8 nano-particles), and the permeate pressure on the downstream side (without ZIF-8 nano-particles) was monitored by using a MKS-Baratron pressure transducer.

Pure-gas permeability is determined by

where P is the permeability (Barrer) (1 Barrer = 10–10 cm3(STP) cm/cm2 s cmHg), A is the effective membrane area (cm2), V is the downstream volume (cm3), R is the universal gas constant (6236.56 cm3 cmHg/mol K), T is the absolute temperature (K), L is the membrane thickness (cm), p is the upstream pressure (cmHg), and dp/dt is the permeation rate (cmHg/s).

The ideal selectivity for the O2/N2 gas pair is determined by

The diffusion coefficient D (cm2/s) is obtained by

where L is the membrane thickness (cm) and θ is the time lag of the permeability measurement (s).

The solubility coefficient S [cm3(STP)/(cm3 cmHg)] is calculated by

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the research funding provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91745116), Tianjin Research Program of Application Foundation and Advanced Technology (17JCZDJC36900), and the Science and Technology Plans of Tianjin (16PTSYJC00090).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02363.

Additional experimental results including data on PIM-1 characterization (1H NMR and GPC analysis), N2 isothermal adsorption–desorption of the PIM-1 and PIM/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane, and particle size distribution of the PIM/ZIF-8-7 composite membrane (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baker R. W.; Low B. T. Gas separation membrane materials: A perspective. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6999–7013. 10.1021/ma501488s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murali R. S.; Sankarshana T.; Sridhar S. Air separation by polymer-based membrane technology. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2013, 42, 130–186. 10.1080/15422119.2012.686000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Wang Z.; Zhao D. Mixed matrix membranes for natural gas upgrading: Current status and opportunities. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 4139–4169. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b04796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budd P.; McKeown N.; Ghanem B.; Msayib K.; Fritsch D.; Starannikova L.; Belov N.; Sanfirova O.; Yampolskii Y.; Shantarovich V. Gas permeation parameters and other physicochemical properties of a polymer of intrinsic microporosity: Polybenzodioxane PIM-1. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 325, 851–860. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson L. M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T.-S.; Jiang L. Y.; Li Y.; Kulprathipanja S. Mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) comprising organic polymers with dispersed inorganic fillers for gas separation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 483–507. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane B.; Coronas J.; Gascon I.; Benavides M. E.; Karvan O.; Caro J.; Kapteijn F.; Gascon J. Metal-organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: a solution for highly efficient CO2 capture. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2421–2454. 10.1039/c4cs00437j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Liu W.; Wu H.; Zong X.; Yang L.; Wu Y.; Ren Y.; Shi C.; Wang S.; Jiang Z. Nanoporous ZIF-67 embedded polymers of intrinsic microporosity membranes with enhanced gas separation performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 309–318. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.11.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tien-Binh N.; Vinh-Thang H.; Chen X. Y.; Rodrigue D.; Kaliaguine S. Crosslinked MOF-polymer to enhance gas separation of mixed matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 520, 941–950. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.08.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khdhayyer M.; Bushell A. F.; Budd P. M.; Attfield M. P.; Jiang D.; Burrows A. D.; Esposito E.; Bernardo P.; Monteleone M.; Fuoco A.; Clarizia G.; Bazzarelli F.; Gordano A.; Jansen J. C. Mixed matrix membranes based on MIL-101 metal–organic frameworks in polymer of intrinsic microporosity PIM-1. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 212, 545–554. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushell A. F.; Attfield M. P.; Mason C. R.; Budd P. M.; Yampolskii Y.; Starannikova L.; Rebrov A.; Bazzarelli F.; Bernardo P.; Carolus Jansen J.; Lanč M.; Friess K.; Shantarovich V.; Gustov V.; Isaeva V. Gas permeation parameters of mixed matrix membranes based on the polymer of intrinsic microporosity PIM-1 and the zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-8. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 427, 48–62. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.09.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tien-Binh N.; Rodrigue D.; Kaliaguine S. In-situ cross interface linking of PIM-1 polymer and UiO-66-NH2 for outstanding gas separation and physical aging control. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 429–438. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.11.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju D.; Bhagat D. G.; Banerjee R.; Kharul U. K. In situ growth of metal-organic frameworks on a porous ultrafiltration membrane for gas separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 8828–8835. 10.1039/c3ta10438a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. T.; Koros W. J. Non-ideal effects in organic-inorganic materials for gas separation membranes. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 739, 87–98. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.05.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhah O.; Chernikova V.; Belmabkhout Y.; Eddaoudi M. Metal-organic framework membranes: From fabrication to gas separation. Crystals 2018, 8, 412. 10.3390/cryst8110412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid S.; Nijmeijer K.; Nehache S.; Vankelecom I.; Deratani A.; Quemener D. MOF-mixed matrix membranes: Precise dispersion of MOF particles with better compatibility via a particle fusion approach for enhanced gas separation properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 492, 21–31. 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marti A. M.; Venna S. R.; Roth E. A.; Culp J. T.; Hopkinson D. P. Simple fabrication method for mixed matrix membranes with in situ MOF growth for gas separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 24784–24790. 10.1021/acsami.8b06592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacho-Bailo F.; Seoane B.; Téllez C.; Coronas J. ZIF-8 continuous membrane on porous polysulfone for hydrogen separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 464, 119–126. 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.03.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsaei E.; Low Z.-X.; Lin X.; Mayahi A.; Liu H.; Zhang X.; Zhe Liu J.; Wang H. Rapid synthesis of ultrathin, defect-free ZIF-8 membranes via chemical vapour modification of a polymeric support. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11474–11477. 10.1039/c5cc03537f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuoco A.; Khdhayyer M.; Attfield M.; Esposito E.; Jansen J.; Budd P. Synthesis and transport properties of novel MOF/PIM-1/MOF sandwich membranes for gas separation. Membranes 2017, 7, 7. 10.3390/membranes7010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskii Y.; Alentiev A.; Bondarenko G.; Kostina Y.; Heuchel M. Intermolecular interactions: New way to govern transport properties of membrane materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 12031–12037. 10.1021/ie100097a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du N.; Song J.; Robertson G. P.; Pinnau I.; Guiver M. D. Linear high molecular weight ladder polymer via fast polycondensation of 5,5′,6,6′-Tetrahydroxy-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylspirobisindane with 1,4-dicyanotetrafluorobenzene. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 783–788. 10.1002/marc.200800038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J. W.; Kim D.-G.; Sohn E.-H.; Yoo Y.; Kim Y. S.; Kim B. G.; Lee J.-C. Highly carboxylate-functionalized polymers of intrinsic microporosity for CO2-selective polymer membranes. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8019–8027. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown N. B. Polymers of intrinsic microporosity. ISRN Mater. Sci. 2012, 2012, 1–16. 10.5402/2012/513986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semino R.; Ramsahye N. A.; Ghoufi A.; Maurin G. Microscopic model of the metal-organic framework/polymer interface: A first step toward understanding the compatibility in mixed matrix membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 809–819. 10.1021/acsami.5b10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskii Y. P.; Pinnau I.; Freeman B. D.. Materials Science of Membranes for Gas and Vapor Separation; Wiley, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Du N.; Robertson G. P.; Song J.; Pinnau I.; Guiver M. D. High-performance carboxylated polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) with tunable gas transport properties. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 6038–6043. 10.1021/ma9009017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson L. M.; Smith Z. P.; Freeman B. D.; Paul D. R. Contributions of diffusion and solubility selectivity to the upper bound analysis for glassy gas separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 453, 71–83. 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.10.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B. D. Basis of permeability/selectivity tradeoff relations in polymeric gas separation membranes. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 375–380. 10.1021/ma9814548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satilmis B.; Budd P. M. Base-catalysed hydrolysis of PIM-1: Amide versus carboxylate formation. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 52189–52198. 10.1039/c4ra09907a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.