Abstract

Objective. To reach a consensus on a working definition for leadership and identify expectations for leadership among all pharmacy faculty members.

Methods. A modified Delphi process was employed to establish consensus among experienced department and division chairs regarding the definition and expectations of faculty leadership to guide faculty evaluation and development. From the AACP faculty roster, 280 department and division chairs were surveyed to identify participants with at least five years of experience in their roles and willingness to participate. Twenty-three chairs were identified from a variety of colleges and schools to comprise the expert panel and asked to participate in three rounds of questions over a two-month period. One Likert-type question and six open-ended questions were included in round 1. A thematic analysis of round 1 responses provided items for participants to rate their agreement with and provide comments on in rounds 2 and 3. Consensus for items was set prospectively at 80% of participants selecting agree or strongly agree for each item. Items could be modified by the panel in subsequent rounds of surveys if participants suggested edits to items.

Results. Consensus was achieved among 23 chairs regarding a definition, 10 guiding principles, four learning competencies, six skills, six expected leadership activities (ELAs), and 20 personal characteristics related to faculty leadership.

Conclusion. The results of this study provide guidance to pharmacy faculty members and administrators regarding leadership characteristics including knowledge, skills, and activities expected for faculty members to develop into effective leaders for the academy and the pharmacy profession.

Keywords: leadership, faculty, Delphi, expectations

INTRODUCTION

The focus on leadership as a part of the development of the affective domain of learning in pharmacy education has received much curricular focus and stimulated innovation in the past 10 years. During an address to the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), then-president Barbara Wells challenged the academy to develop and embrace leadership to address the challenges it faces.1 With so much attention placed on the leadership development of learners, the behaviors of those modeling leadership may be overlooked. In working with future generations of practitioners as well as patients and the public, all pharmacy faculty members are in a position to be among the most influential leaders in their communities, the profession, and higher education. Kezar and colleagues summarized the importance of faculty members as leaders on campus both in decision-making and innovation in teaching, research, and service.2 In considering leadership specific to academic pharmacy, Dr. Wells further stated that leadership is what propels faculty members to reach their potential.1 Faculty members are essential to academic organizations fulfilling their mission and, therefore, need to be adequately developed to lead. In the course of their professional development, the question of what leadership characteristics are expected of faculty members is vital to answer.

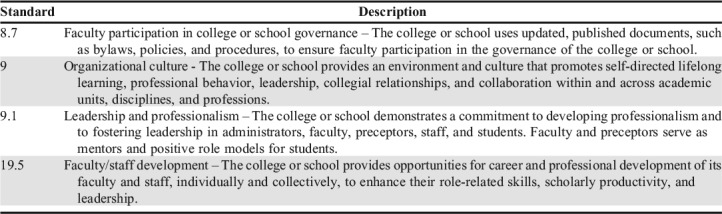

Many articles discuss the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for administrative leaders in academia. For example, Basham identified transformational leadership characteristics necessary for college and university presidents in higher education.3 As a dean in the health professions, Haden outlined a conceptual framework for leadership.4 Others have identified leadership attributes that deans of dentistry and nursing schools should have.5,6 Finally, Schwinghammer and colleagues identified leadership characteristics for department chairs in pharmacy schools.7 While faculty members may choose to exercise their leadership capabilities by taking administrative roles, leadership expectations should not be restricted to those with administrative or “positional” authority. Within academic pharmacy, leadership is addressed multiple times in the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education “Standards 2016” (Table 1).8 However, little research has been done to determine the specific skills, attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs associated with faculty leadership in pharmacy. In fact, faculty culture may often work against leadership development given its focus on “publish or perish” rather than strategy and influence.9 The evolving landscape in pharmacy and healthcare demands that faculty members be prepared to be effective leaders.

Table 1.

Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards Related to Faculty Leadership8

Leadership by non-administrative faculty members has been evaluated in other disciplines. For example, the top leadership skills needed by faculty members in business management have been identified as business skills (eg, management of personnel, material, and financial resources to accomplish business goals), cognitive skills (eg, communication and ability to learn and adapt), and interpersonal skills (eg, interacting with and influencing others).10 Preparation for faculty leadership has been discussed in nursing,11 and faculty development initiatives to promote leadership in medical education have also been developed.12 Faculty citizenship has been addressed in pharmacy, but likely represents only a part of faculty leadership.13,14

This study was conducted to identify a working definition of faculty leadership, and develop learning competencies, skills, expected leadership activities (ELAs), and personal characteristics related to leadership expected of all faculty members in academic pharmacy. The study was conducted by the Scholarship Committee of the AACP Leadership Development Special Interest Group with the intent of providing recommendations and a framework that can be used by AACP and individual institutions to guide leadership development efforts of all current and future faculty members.

METHODS

This study employed a three-round Delphi process to address the study objectives described above. In a Delphi process, each round uses a survey to progress a group of identified experts from individual opinions to consensus on a chosen topic.15 In the first round, researchers interpret participants’ individual answers to open-ended questions and craft thematic statements to use in subsequent rounds. Later rounds ask experts to rate their agreement with the developed statements and submit comments to improve and/or enhance agreement with the statements. Modifications are made to statements when comments are provided in early rounds and agreement is pursued in additional rounds until a predetermined level of agreement is reached or the process ends.16 Delphi processes have been used in the pharmacy education literature to address a variety of issues, including student perceptions of professional engagement and identification of leadership development competencies and guiding principles.16-18

This study was approved with exempt status by the Concordia University Wisconsin Institutional Review Board. Experts solicited for involvement were department or division chairs identified from AACP’s Roster of Faculty. A survey was e-mailed to 280 chairs confirming their current roles and requesting information related to their years of experience in the role and name of the department they chair. Chairs with at least five years of experience in that role were chosen as the experts because of their responsibilities and experiences related to faculty development and evaluation of leadership skills. A panel size of at least 20 experts was desired based on acceptable study sizes between 10 and 50 participants reported in the literature.19,20

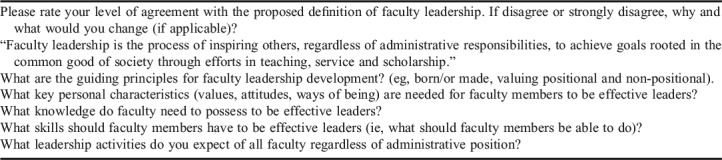

Our study consisted of three rounds of surveys administered online via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Surveys were open for two weeks for rounds 1 and 2 and three weeks for round 3. The entire process took place between September 27, 2016, and November 22, 2016. Experts received reminder emails one week prior to the deadline for each survey round if they had not yet completed the survey. The first round consisted of open-ended questions and one Likert-type question to solicit the opinions of each expert (Table 2). The researchers then conducted a thematic analysis of the responses, crafted leadership expectations for faculty members and personal characteristics of effective faculty leaders, and modified a draft definition of faculty leadership. The items from the process were linked to the expert responses and shared with experts prior to rounds 2 and 3 to ensure transparency in the study.

Table 2.

Questions Asked of the Expert Panel in Round 1 of a Modified Delphi Process to Define the Leadership Characteristics Expected of Pharmacy Faculty Members

In rounds 2, experts were asked to rate their level of agreement with each item. A Likert scale was used with the following format: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree. A comment box was provided to allow participants to include qualitative responses about each item. Experts were encouraged to comment if they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the items. This inclusive process resulted in additional comments for each item. When applicable, comments were used to propose amendments to the items for expert consideration in round 3. Consensus on an item was defined prospectively by the research team as being when 80% of the experts responded agree or strongly agree to the item. Because there are no definitive guidelines, Delphi studies have used varying levels of consensus ranging from 51% to 100%.21

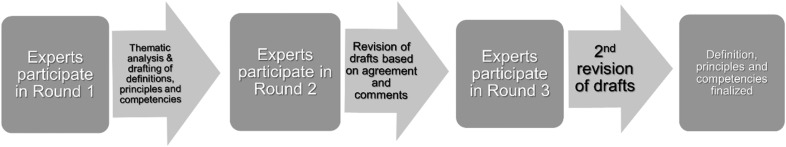

Items that did not reach the consensus level of 80% in round 2 were revised or removed based upon expert comments and reviewed by the research team. Items that reached consensus could be revised based upon expert comments if the researchers decided that the revision substantially improved the clarity of the item. In round 3, experts received a document outlining the results of round 2. Revised item revisited in the round 3 survey followed the same format as the round 2 survey. An overview of the modified Delphi process used is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Modified Delphi Process to Define the Leadership Characteristics Expected of Pharmacy Faculty Members

RESULTS

Of the 280 identified chairs from the AACP roster, 24 (8.6%) were interested in participating in this study and had at least five years of experience in their role. Twenty-three experts participated in round 1 and 24 experts participated in round 2 and round 3. The average time the participants had spent chairing a department was 9.6 years, with a range of 5 to 26 years. Ten participants represented pharmacy practice, eight represented a pharmaceutical science department, and six represented a combined pharmacy administration/pharmacy practice department. Thirteen participants represented public institutions and 10 represented private institutions.

The Delphi process resulted in consensus, with 82.6% expert agreement with the following definition of faculty leadership: “Faculty leadership is the process of collaborating with, inspiring and enabling others, regardless of one's administrative responsibilities, to achieve goals rooted in a shared mission and vision through ethical efforts in teaching, service and scholarship.”

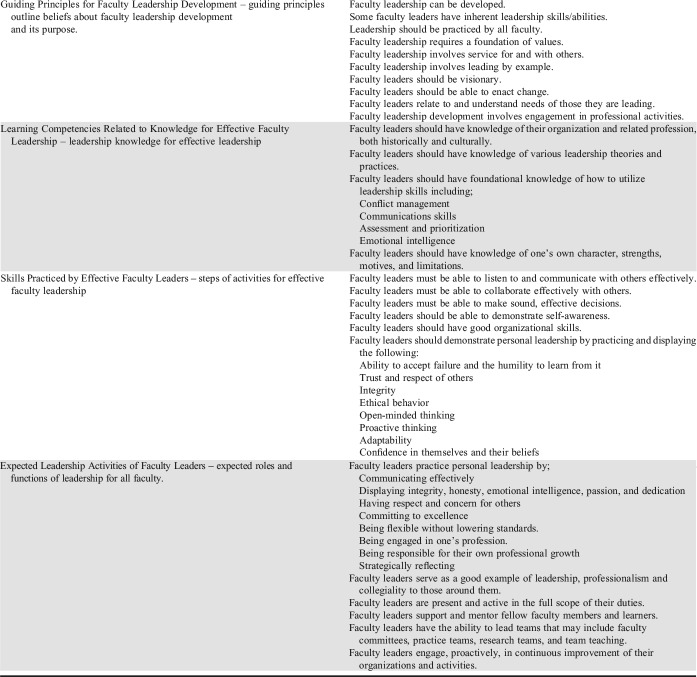

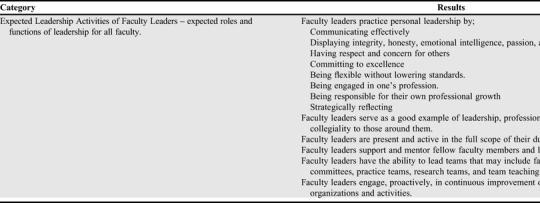

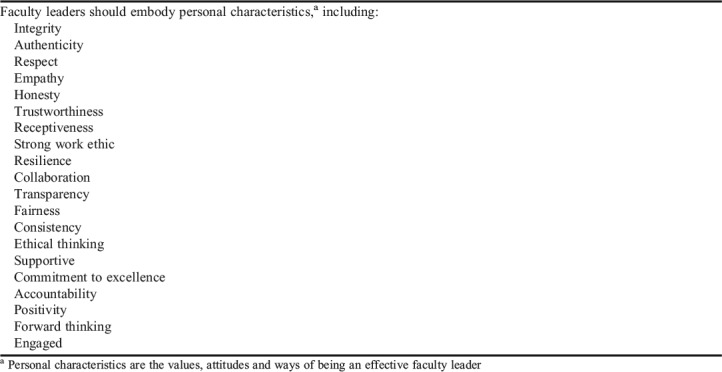

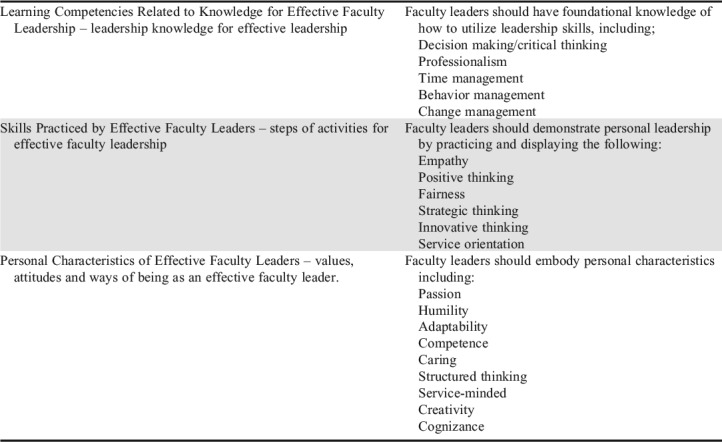

Ten guiding principles for faculty leadership, four learning competencies, six skills, and six ELAs achieved expert consensus (Table 3). Twenty personal characteristics of effective faculty leaders were also identified (Table 4). Several expectations proposed by experts in round 1 failed to achieve the predetermined level for consensus in rounds 2 and 3 (Table 5).

Table 3.

Consensus Leadership Expectations for All Pharmacy Faculty Members That Were Identified by an Expert Panel Through a Modified Delphi Process

Table 4.

Personal Characteristics of Effective Pharmacy Faculty Leaders as Identified by Consensus of an Expert Panel Who Participated in a Modified Delphi Study

Table 5.

Faculty Leadership Expectations Failing to Achieve Expert Panel Consensus in a Modified Delphi Study

DISCUSSION

As noted by Kezar, leadership remains critical to innovation in teaching and advancing knowledge on campuses.2 While the literature most often describes leadership from the perspective of administrators, leadership should be expected of all pharmacy faculty members, regardless of rank or administrative title. Daily interactions are vital to the operations of pharmacy education and impact our learners, patients, professional colleagues, and society. There are many examples of these daily interactions. Student organizations require well-prepared and committed faculty advisors and mentors to ensure their success in achieving the group’s goals and communicating with the parent national organization. Faculty members with patient care practices must take leadership roles on healthcare teams to ensure that patients achieve optimal outcomes from their medication therapy. Research faculty members are increasingly required to display leadership on teams with multidisciplinary faculty members in order to compete successfully for extramural funding and participate in meaningful collaborative translational research endeavors. Faculty members who serve as coordinators in team-taught courses must be responsible for overall course management and integration and not simply teach the content in their own area of clinical or scientific expertise. Faculty members are appointed to chair important school committees that directly impact the mission of the college or school, such as the curriculum committee or an accreditation self-study committee. Both practice and science faculty members are needed to serve academic, professional, and scientific organizations on appointed committees and as elected volunteer leaders at local, state, and national levels.

Despite the multitude of areas where faculty members are required to demonstrate leadership prowess, little research has been conducted to identify what specifically is needed to develop leadership for all faculty members. Our study, which is novel within health professions education, achieved consensus from 23 experienced pharmacy department or division chairs across the United States about what constitutes effective leadership for all faculty members.

The results of this study are intended to help frame the construct of leadership programs by providing a hierarchy for development efforts. The guiding principles proposed here for faculty leadership are the broadest statements conceptually and represent the goals and priorities that leadership programs should consider when developing their mission statements. The proposed competencies are the defined behaviors that should be the outcome measurements established through a program’s guiding principles. The proposed skills are the abilities that the competencies reinforce. The proposed ELAs are akin to the entrustable professional activities (EPAs) that outline core skills necessary to enter pharmacy practice.22 Finally, the proposed characteristics are the desired leadership attributes and qualities of all faculty members. All these items articulate the importance, relevance, and practicality of faculty leadership and provide a framework for leadership development opportunities. The broad nature of these categories permit innovation in the areas of faculty hiring, development, evaluation, retention, and promotion.

While this study identified numerous leadership characteristics needed of all faculty members, certain proposed leadership expectations failed to achieve expert consensus (Table 5). The study was not designed to determine why these expectations were not selected. Some of these characteristics (eg, competence, caring) and skills (eg, empathy, fairness), are often included in leadership discussions, so why did they not reach consensus in this study? One may infer that respondents did not believe those characteristics were important enough to merit inclusion. One alternate explanation is that respondents felt that those attributes were encompassed in other qualities, and it was not necessary to duplicate characteristics. An alternate explanation is that respondents did not identify the attribute with leadership specifically.

The outcomes of this study are important because many newly hired faculty members lack formal leadership training. For other long-time faculty members, assuming leadership roles in a school or college may be perceived as unrewarding or as a distraction from pursuing their personal goals in teaching, patient care, or research. Pharmacy faculty members must understand the importance of their leadership contributions, and that they feel prepared to take on such roles. Some of these individuals may aspire to future formal leadership positions such as department chair, assistant/associate dean, dean, or other administrative roles in higher education. Thus, leadership development for these faculty members is important for their career trajectory and for succession planning in schools and colleges to ensure seamless leadership transitions. Faculty members could also self-assess their characteristics to identify areas of focus for leadership development. Faculty members should demonstrate exemplary leadership characteristics for students, patients, and colleagues, which is important internal modeling and external representation of our profession. Faculty interactions with students are especially important because we expect graduates to become the change agents required for continued advancement of the pharmacy profession. Department chairs could use the results of this study to facilitate formal and informal professional development opportunities. Using a data-driven, analytical process, the results create a holistic model for designing leadership development programs.

The results of this study also corroborate and support what has been reported by other health education disciplines. Within nursing education, Young and colleagues reported that nurse faculty leaders often found themselves thrust into leadership positions for which they were unprepared, or did not identify themselves as leaders until they were recruited into leadership positions by others.11 The authors concluded that although such experiences are part of becoming a leader, formal preparation that supports and encourages leadership development in nursing faculty members is needed.

In medical education, Steinert and colleagues performed a systematic review of the effects of faculty development interventions designed to improve leadership abilities on the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of faculty members in medicine and on the institutions in which they work.12 The authors concluded that, despite generally weak study designs, the literature supported that faculty development programs resulted in positive outcomes. Program features that contributed to positive outcomes included use of multiple instructional methods within single interventions, experiential learning and reflective practice, individual and group projects, peer support, development of communities of practice, mentorship, and institutional support.

With regard to pharmacy education, the 2002-2003 joint meeting of the AACP Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees identified competencies for effective leadership for faculty members, associate and assistant deans, department chairs, and deans of colleges and schools of pharmacy. These competencies included consensus building, ability to articulate a vision, networking skills, credibility and integrity, communication skills including listening, and ability to make a decision.23 The groups agreed that a wide variety of leadership development programs should be offered to meet the needs of pharmacy faculty members across the academy. The 2002-2003 Research and Graduate Affairs Committee recommended that AACP establish a Center for Academic Leadership and Management in Pharmacy to design and implement structured, ongoing, and comprehensive leadership and management development for AACP members. The group recommended that the proposed center not design programs and services focused only on “positional” leadership because all faculty members are called upon at some point to engage in the process of leadership.24

Although the Center for Academic Leadership and Management as originally proposed was not implemented, the recommendation led to creation of the AACP Academic Leadership Fellows Program (ALFP) in 2005.25 The program has a long and successful history, but it involves a competitive application process, with only one individual allowed to be nominated from each college or school, and only 30 fellows selected to participate each year.

Several AACP initiatives are starting to reach out to more to all faculty members. The AACP Interim Meetings, INfluence 2017 and INspire 2018, have focused on leadership development. While previous interim meetings have often been targeted toward administrators, the intended audience for the recent meetings has included all faculty members.26,27 Regional Leading Forward workshops have been offered in conjunction and separate from AACP/National Association of Boards of Pharmacy District Meetings.28 The AACP’s Leadership Development SIG offers support for all leaders through programming, including a book blog available to all faculty members.29 The Leadership and Management Certificate Program of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy and the Foundation Pharmacy Leadership Academy conducted by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists provide programming options for faculty members to consider.30,31

Despite these study findings and existing programs, faculty leadership development can only be successful if it is integrated as a central and deliberate part of the culture of the school or college of pharmacy.32 It must also remain at the forefront of initiatives and strategic planning. Strategic Priority 7 of the 2016-2019 AACP Strategic Plan states, “AACP is considered a priority organization for affiliation and leadership development by volunteers and staff,” and Goal 7.2.2 is “Enhance new leadership orientation activities.”32 For these reasons, the authors recommend that the findings from this work be made an integral part of AACP’s efforts in developing its members to be vibrant leaders at their institutions.

We offer the following recommendations for supporting the leadership development of pharmacy educators. The AACP should support deans and department chairs in creating an institutional culture that fosters faculty leadership development. The AACP should support ACPE accreditation standards that directly address the development of faculty leaders and encourage guideline development in these areas where appropriate. The AACP and colleges and schools of pharmacy should consider faculty leadership development in the strategic planning processes and include specific goals and outcomes related to faculty leadership. The AACP and colleges and schools of pharmacy should support inclusion of faculty leadership development in institutional and individual faculty assessment criteria. Colleges and schools should support faculty leadership development within their institution and in collaboration with other colleges and schools of pharmacy and other health professions colleges and schools. The AACP should support faculty members seeking leadership development opportunities. The faculty development efforts of the AACP and colleges and schools of pharmacy should focus on specific competencies related to effective faculty leadership, which may include knowledge of the organization, leadership theories and practices, self-assessment, and skills in conflict management, communication, assessment/prioritization, and emotional intelligence. The AACP should support research and scholarship related to faculty leadership development. Colleges and schools of pharmacy should provide opportunities for service that promotes faculty leadership development and support faculty engagement in professional activities. Colleges and schools of pharmacy should recognize faculty leaders who exhibit leadership characteristics and demonstrate adherence to learning competencies related to effective leadership.

Consistent with any Delphi study, a limitation of this work is that the study method resulted in data based solely on the expert opinions of the department and division chairs who chose to participate in the study. Thus, differing opinions of people with legitimate expertise are missing from this work. In addition, the sample size was small and represents less than 10% of the department and division chairs in US schools and colleges of pharmacy. Because of a lack of demographic information publicly available about pharmacy chairs, it was not possible to ascertain how many people who were experts as defined in this study were not interested in participating. However, the number of participants in this study is consistent with other Delphi studies completed in pharmacy and with ranges reported in the literature.18 In addition, although statements were vetted through all members, the research team’s own experiences may have impacted their analysis of the results.

CONCLUSION

This study provides guidance to pharmacy faculty members and administrators regarding leadership principles and the necessary knowledge, skills, and activities required for faculty members to develop into effective leaders for the academy and the pharmacy profession. Their leadership is vital for achieving personal potential in teaching, patient care, and research; for advancing the mission of colleges and schools; and for serving as role models for future pharmacists. It is not sufficient to rely on a small, select group of “gifted” leaders to confront the many challenges facing the academy and the pharmacy profession.1 Leadership must be developed in all faculty members, who in turn must nurture leadership in students. The statements developed are the product of extensive debate and begin to articulate a consensus on the importance, relevance, and practicality of faculty leadership. The broad approach of these statements offers many opportunities for innovation in the areas of faculty development, hiring, evaluation, and promotion. Additional research may include response and comment from audiences outside of pharmacy. In addition, examination of methods for implementing the statements will be needed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wells B. Leadership: our hope for transformation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(4):436–439. http://archive.ajpe.org/legacy/pdfs/aj660417.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kezar A, Lester J, Carducci R, Gallant TB, McGavin MC. Where are the faculty leaders? Strategies and advice for reversing current trends. https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/where-are-faculty-leaders-strategies-and-advice-reversing-current . Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 3.Basham LM. Transformational leadership characteristics necessary for today’s leaders in higher education. J Inter Educ Res. 2012;8(4):343–348. doi: 10.19030/jier.v8i4.7280. https://www.cluteinstitute.com/ojs/index.php/JIER/article/view/7280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haden NK. Becoming a successful dean in the health professions. https://aalgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Becoming-a-sucessful-dean-in-the-health-professions.pdf . Accessed August 29, 2019.

- 5.Haden NK, Ditmyer MM, Rodriguez T, Mobley C, Beck L, Valachovic RW. A profile of dental school deans, 2014. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(10):1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkes L, Cross W, Jackon D, Daly J. A repertoire of leadership attributes: an international study of deans of nursing. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23:279–286. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwinghammer TL, Rodriguez TE, Weinstein G, et al. AACP strategy for addressing the professional development needs of department chairs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6):S7. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Standards; 2016. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree.https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf . Accessed October 2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barden DM, Curry J. Faculty members can lead, but will they? http://www.chronicle.com/article/Faculty-Members-Can-Lead-but/138343/ . Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 10.Kalargyrou V, Pescosolido AT, Kalargiros EA. Leadership skills in management education. Acad of Educ Leadership J. 2012;16(4):39–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young PA, Pearsall C, Stiles KA, Horton-Deutsch S. Becoming a nursing faculty leader. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(4):222–228. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-32.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinert Y, Naismith L, Mann K. Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Med Teacher. 2012;34(6):483–503. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.680937. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/0142159X.2012.680937 . Accessed October 2, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree B, Hammer D, Bynum LA, et al. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Faculties: Faculty Affairs Committee on Faculty Citizenship. pp. 2014–2015.http://www.aacp.org/governance/councilfaculties/Documents/AACPCOF2015FacultyCitizenshipFinalReport.pdf . Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 14.Ross LA, Janke KK, Boyle CJ, et al. Preparation of faculty members and students to be citizen leaders and pharmacy advocates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 220. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710220. 10.5688/ajpe7710220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole ZD, Donohoe HM, Stellefson ML. Internet-based Delphi research: case-based discussion. Environmental Management. 2013;51(3):511–523. doi: 10.1007/s00267-012-0005-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronson BD, Janke KK, Traynor AP. Investigating student pharmacist perceptions of professional engagement using a modified Delphi process. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(7):Article 125. doi: 10.5688/ajpe767125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janke KK, Traynor AP, Boyle CJ. Competencies for student leadership development in doctor of pharmacy curricula to assist curriculum committees and leadership instructors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 222. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traynor AP, Boyle CJ, Janke KK. Guiding principles for student leadership development in the doctor of pharmacy program to assist administrators and faculty members in implementing or refining curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 221. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A Guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Vol. 10. Glenview, IL: Scott: Foresman, and Co; 1975. p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Witkin BR, Altschuld JW. Planning and Conducting Needs Assessments: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(4):376–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines ST, Pittenger AL, Stolte SK, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for new pharmacy graduates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):S2. doi: 10.5688/ajpe811S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin AY, Altiere RJ, Harris WT, et al. Leadership: the nexus between challenge and opportunity: reports of the 2002-03 Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article S5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr RA, Beck DE, Doss J, et al. Building a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy: report of the 2008-09 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article S5. doi: 10.5688/aj7308s05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Academic Leadership Fellows Program. https://www.aacp.org/academic-leadership-fellows-program . Accessed February 5, 2018.

- 26.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. INfluence. 2017. https://www.aacp.org/event/influence-2017-aacp-interim-meeting-0 . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 27.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. INspire. 2018. https://www.aacp.org/event/inspire-2018-aacp-interim-meeting . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 28.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Regional and Other Meetings. https://www.aacp.org/events/regional-other-meetings . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 29.AACP Leadership Development SIG. https://leaddevsig.wordpress.com/about/ . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 30.ACCP Leadership and Management Certificate Program. https://www.accp.com/academy/leadershipAndManagement.aspx#pnlOverview_title . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 31.ASHP Foundation Pharmacy Leadership Academy. http://www.ashpfoundation.org/MainMenuCategories/CenterforPharmacyLeadership/PharmacyLeadershipAcademy . Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 32.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Strategic Plan of AACP. https://www.aacp.org/article/strategic-plan-aacp . Accessed February 5, 2018.