Abstract

Objective. To determine the prevalence of social isolation and associated factors in graduate and professional health science students.

Methods. Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered via an online survey from graduate and professional students in the colleges of dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and public health at a Midwestern university. Questions assessed students’ demographics, weekly activity hours, support systems, and financial concerns, and included the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale. Logistic regression was performed using the binary outcome of feeling socially isolated (yes/no) and examined program-related respondent comments using thematic analysis.

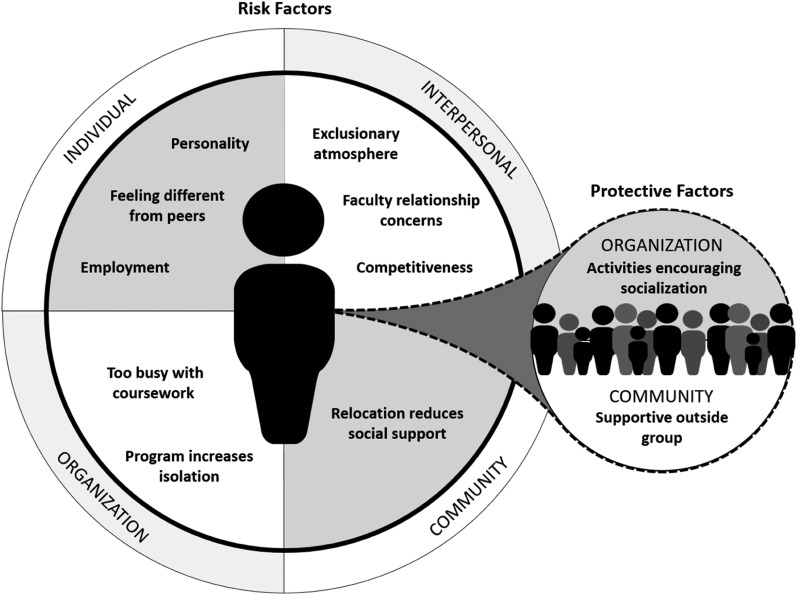

Results. There were 427 survey respondents with 398 completing the full survey. Students answering the social isolation question (n=386) were included in the regression analysis. Nearly one-fifth (19.4%) of respondents indicated social isolation, with the highest percentage among nursing respondents (40.7%). Lacking a strong support, being a non-native English speaker, having caregiving responsibilities, and experiencing “lonely” items described in the UCLA Loneliness Scale were positively associated with social isolation. The ability to discuss feelings with friends in their professional program and experiencing “non-lonely” items were negatively associated with social isolation. Ninety-six comments revealed nine risk factor themes in four categories: individual (feeling different from peers, personality, employment), interpersonal (competition/exclusionary atmosphere, faculty relationship), organization (too busy with coursework, isolating program) and community (relocation reduces social support). Student-involvement in organizations (activities encouraging socialization) and community (support from outside the group) were protective factors.

Conclusion. Understanding associated factors and designing strategies to reduce student social isolation may enhance the quality and well-being of future health professionals and scientists.

Keywords: social isolation, loneliness, well-being, graduate students, professional students

INTRODUCTION

Scientists, doctors, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists are listed among the top 20 professions at highest risk for suicide.1 This alarming statistic has led to an increase in studies of well-being in health care professionals and scientists. Burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment) has been reported in 49.6% and 40% of medical and dental students, respectively, and suicidal ideation rates have been reported to be 11.2% and 6%, respectively.2,3 One factor found to promote personal well-being and reduce burnout is social support, which reduced the need for medication, prevented pathological states including depression and alcoholism, and helped the body recover faster.4-7 In a study of medical residents, loneliness was associated with burnout in a dose-dependent (ie, as burnout increases, loneliness increases and vice-versa) fashion.8 Despite the knowledge that loneliness and burnout coexist, the specific factors that contribute to health professionals’ feelings of isolation or “loneliness” are unknown.

Social isolation is defined as the “inadequate quality and quantity of social relations with others at the different levels where human interaction takes place (individual, group, community and the larger social environment).”9 Though quantity of interactions is easily measurable, measures of the quality of social relations are less quantifiable and often referred to as subjective social isolation, perceived isolation, or more “colloquially” as loneliness.10-12

Social isolation is associated with a range of physical and mental sequelae, even in the young. Cigna conducted research of more than 20,000 adults greater than 18 years of age and found that the majority of Americans considered themselves lonely.13 In particular, however, Generation Z (age 18-22) and Millennials (age 23-27) cited they were lonelier and in worse health compared to older age groups.13 Cacioppo and colleagues noted that socially isolated students rate everyday occurrences as more “intensely stressful,” respond to coping passively, have more dysphoria, feel less connected to those around them, have poorer sleep efficiency, fear public speaking, have greater vascular resistance, and experience slower wound healing.7,14 Of additional concern, there is evidence that subjective social isolation may impair executive function, defined as “the ability to control attention, cognition, emotion and/or behavior to better meet social standards or personal goals, that is, to self-regulate.”7,10

Social connectedness and its relationship to health have been studied to a limited degree in medical student populations. Brazeau and colleagues found that medical students matriculate with better indicators of mental health (eg, less burnout, symptoms of depression, and quality of life measures) than age-matched college graduates, yet express high rates of distress and mental deterioration while in medical school.15 They attributed this decline, at least in part, to the learning environment and training process.15 Vora and Kinney found that changing a medical school curriculum to include more distance learning decreased student connectivity, sense of community, and academic satisfaction.16

Perhaps the most relevant research to date was completed by Royal. He collected various indicators of social connectedness from all medical students about their peers to identify who was isolated, and noted that colleagues identified black female medical students as comparatively less connected to their medical cohort peers.17 Royal addressed factors of objective social isolation using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 1=do not know to 7=know very well, as opposed to a student’s own subjective identification of isolation or loneliness.17

Although learning environment and demographics in related health professions contribute to outcomes, what is still unknown is whether specific factors exist that place students at risk or protect them from social isolation. This study evaluated both quantitative and qualitative risk factors and protective factors impacting isolation among both professional and graduate students of health profession disciplines.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional mixed-methods online survey study at a public university in the Midwestern United States. The survey instrument was distributed to both professional students (PharmD, MD, and DDS) in the colleges of pharmacy, medicine and dentistry, as well as masters and PhD level students in the aforementioned colleges, as well as the colleges of nursing and public health. Prior to this study, the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy’s Office of Assessment, Curriculum, and Compliance administered an annual, voluntary, end-of-year quality improvement survey to all professional pharmacy students which assessed feelings on self-isolation, the desire for connection to others, their impression of whether opportunities were offered for social connection, and whether life circumstances prevented social engagement. Though information collected previously was useful, findings from related health professions and graduate students are desired to provide further insight into common concerns.

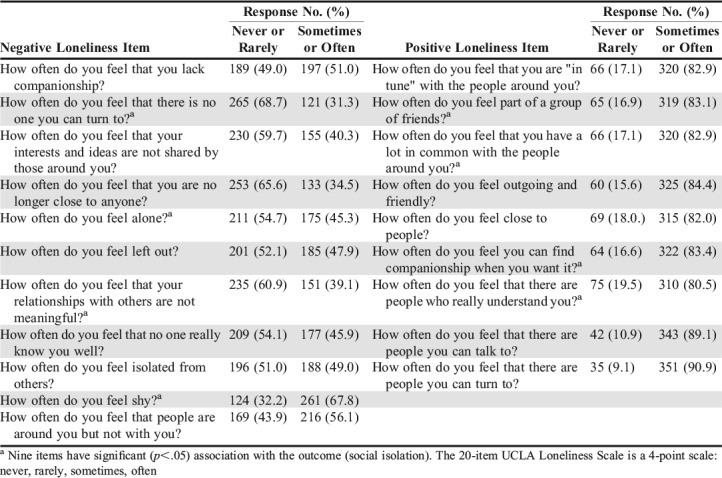

We designed the survey after completing a comprehensive literature review to identify previous studies on social isolation and/or loneliness in any collegiate population or in health care professionals. We examined past collegiate survey instruments to determine the usefulness of previous questions regarding social isolation, as well as demographic questions that were worded in accordance with university standards. We considered various published scales measuring social isolation and/or loneliness and definitions of social isolation to determine which would be best suited for the study. The resultant survey instrument included multiple-choice questions addressing demographics, relationships/supports, living situation, the ease in which one made friends or discussed feelings, and whether financial concerns were a factor related to socialization (Table 1). An open field was included to allow respondents to record time spent weekly in various activities (eg, commuting, sleeping, working, and social media use; Table 2). A previously validated tool for assessing personality traits such as neuroticism and introversion-extroversion, measures of self-esteem and depression, measures of burnout, and measures of social support in college students and nurses was added (Table 3).18 That tool, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, Version 3, consists of 20 questions used to measure subjective social isolation using a four-point rating scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often).18

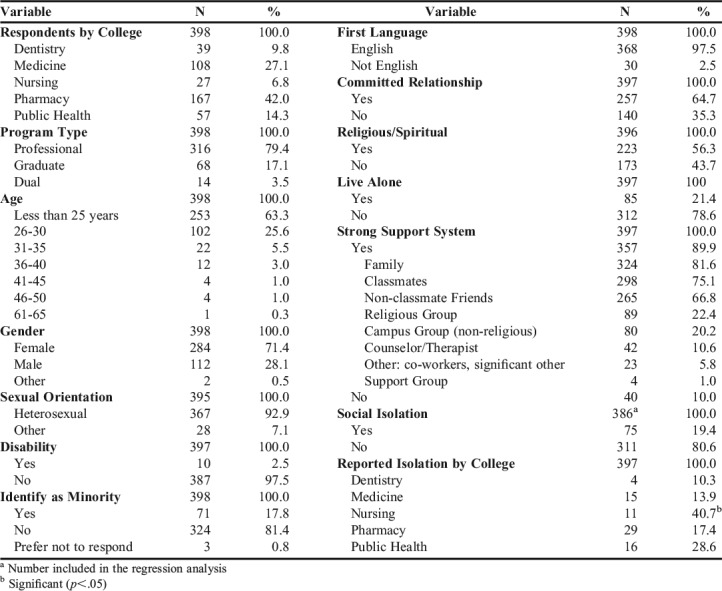

Table 1.

Demographics of Graduate/Professional Health Sciences Respondents to a Social Isolation Survey

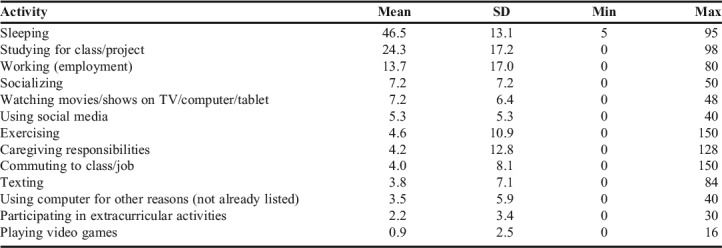

Table 2.

Weekly Activities and Time Spent on Each Activity as Reported by Graduate/Professional Health Sciences Students on a Survey to Identify Social Isolation

Table 3.

Negative and Positive Items of the UCLA Loneliness Scale Used in the Survey and Distribution of Responses

We asked respondents to provide a yes or no response to the following question: “Social isolation is defined as a lack of meaningful social networks. When referring to this definition, would you consider yourself socially isolated?”19 Lastly, respondents were asked to provide comments in an open field regarding social isolation related to their graduate or professional school experience. At the end of the survey instrument, students were given information regarding available counseling services on campus.

We emailed the survey link to the student affairs office, dean, or equivalent for each college, with a request to forward the email to all graduate (MS, MPH, PhD) and professional (DDS, MD, PharmD) students, which included an estimated 2439 students according to university enrollment statistics. Investigators requested redistribution of the survey on two occasions. The college of dentistry declined sending reminders to students because the timing of the survey conflicted with other student obligations. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. To limit duplicate responses, students could not re-access the survey from the same device. A small incentive to participate (entry in a raffle for a gift card) was offered. We maintained confidentiality by rerouting respondents to another website where basic contact information for the raffle was collected. We estimated that it would take students 5-10 minutes to complete the survey, depending on the depth of the comments they provided. The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board classified the study as exempt human subjects research.

Investigators conducted quantitative analyses using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC) and calculated means, ranges, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages of respondent characteristics. We used binary logistic regression to identify predictors of social isolation among respondents. A p value <.05 was considered significant. Based on previous models in literature, we identified 12 independent variables for inclusion in the regression analysis: demographic characteristics, time spent in various activities, relationship/support information, caregiving status, whether they had a strong support system (if they responded yes, they were asked the type of support system), whether finances limited their ability to socialize, and the UCLA Loneliness Scale items to assess positive and negative factors associated with feelings of isolation.20 The study was not powered to conduct a sub-analysis of students by college of study. Students indicating a PharmD/MPH dual degree were included in the analysis with their primary college (ie, the college of pharmacy). In the analysis, the 11 “negative” lonely items of the UCLA Loneliness Scale were compiled into one item and the nine “positive”/non-lonely items were compiled into another.18 Cronbach alpha was calculated to determine the reliability of negative and positive items of the UCLA Loneliness Scale.

Qualitative data were extracted through content analysis of responses to the open-ended question: “Please list any additional comments regarding social isolation as it pertains to your graduate/professional experience.” We followed the six phases of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke, which include familiarizing with data (comments), generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report.21 Lengthy comments were assigned more than one code to represent different themes. After identifying themes and subthemes, investigators selected a compelling student quote that pertained most directly to social isolation to represent each sub-theme for the report.

The research team cross-checked comments and used an inductive, data-driven analytic methodology following a constructivist paradigm (to uncover meaning from data), for the qualitative phase. Themes were constructed from common trends emerging from student comments.22 Investigators checked peer responses and established interrater reliability. As our emergent themes were similar to those found in work performed by Zavaleta, we classified them according to the source into four levels: individual, interpersonal, organization (college/program) and community.9

RESULTS

Assuming full distribution of the survey instrument by each college to their students, 2439 students were eligible to participate in the study. Of those, 427 students responded (17.5%). Because not all respondents completed the entire survey, only 398 were included in the study (16.3% of all eligible students). Completion rate by college among potential participants was as follows: pharmacy (33.7%), public health (17.9%), medicine (11%), nursing (10.9%), and dentistry (9.8%). A higher number of female students than male students from the colleges of medicine and dentistry completed the survey and a higher than representative female completion rate was noted in both colleges (p=.024). Respondent characteristics are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Respondents answering the binary social isolation question (n=386) were included in the regression analysis. Nearly one-fifth (75, 19.4%) of respondents indicated they were experiencing social isolation. The Cronbach alpha of both positive (0.897) and negative items (0.905) demonstrated reliability (scores of 0.7 or higher are considered “acceptable” in most research).23 Though beyond the focus of the study, the Cronbach alpha of the total UCLA Loneliness scale score (20 items) was a reliable indicator (0.936).

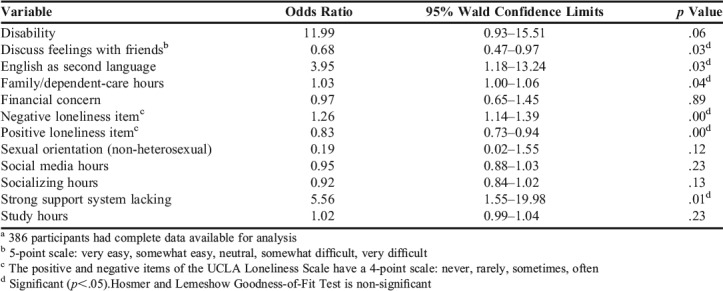

Among the 12 independent variables included in the logistic regression, six had a significant (p<.05) association with the binary outcome (Table 4). Four indicators increasing the likelihood of social isolation included lacking a strong support system, non-native English speaking, needing to care for family members or dependents, and the presence of the negative (“lonely”) items on the UCLA Loneliness Scale.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression of the Factors Influencing Social Isolation as Reported on a Survey of Graduate and Professional Health Sciences Studentsa

In contrast, respondents who scored higher in the positive (“non-lonely”) items of the UCLA Loneliness Scale, and respondents who indicated it was easy to discuss feelings with friends in their study program were less likely to indicate social isolation. Social isolation was not significantly associated with disability, sexual orientation, financial concerns, or time spent socializing with others in person, while using social media, or while studying. Although not predicted a priori, the Fisher exact test showed a significant difference (p=.002) in social isolation by college. The college of nursing had the highest percentage of socially isolated respondents (11 out of 75, 40.7%) (p<.05).

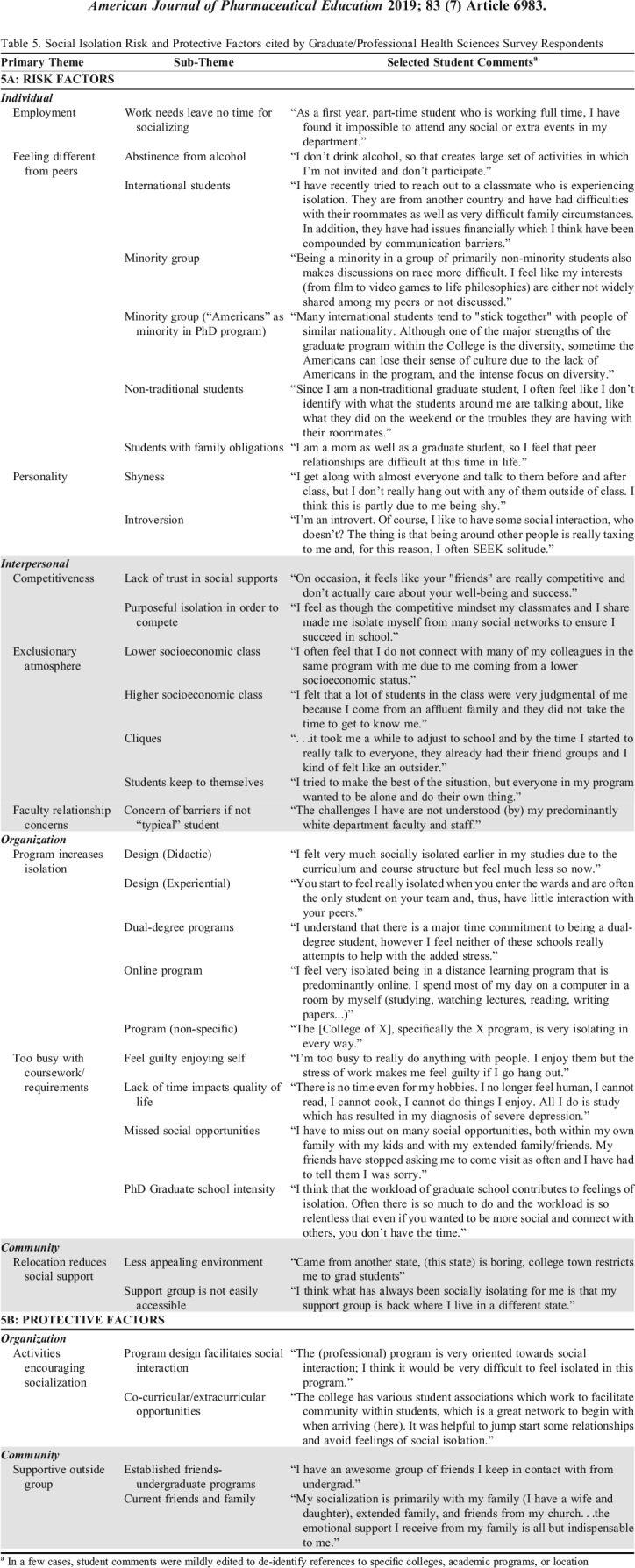

During the qualitative analysis, comments from 115 respondents were reviewed; 96 (83.5%) were considered pertinent to analysis (ie, discussed factors relative to social isolation). Nine risk factor themes and two protective factor themes emerged that could be classified within one of four main categories. Refer to Table 5 and Figure 1 for themes/subthemes and associated compelling quotes.

Table 5.

Social Isolation Risk and Protective Factors cited by Graduate/Professional Health Sciences Survey Respondents

Figure 1.

Qualitative Social Isolation Factors Reported by Graduate/Professional Health Science Students

DISCUSSION

This is the first study examining factors influencing subjective social isolation in graduate or professional health care students. Our findings indicate that social isolation exists in nearly one in five (19.4%) graduate or professional health care students. Social isolation is more likely to occur when there is lack of a strong support system, in non-native English speakers, in those needing to care for family members or dependents, and in those with “loneliness” items indicated on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. In contrast, students who felt they could discuss feelings with others and recorded positive “non-lonely” indicators on the scale were less likely to experience social isolation. A variety of other themes emerged in the qualitative analysis that both reinforced these factors and provided additional insight into reasons students may feel isolated or protected from isolation.

Social isolation was more extensively noted in college of nursing students as compared to other students. A greater percentage of graduate students in this program self-reported taking online coursework which may have played a role in this finding, though there is also a possibility for selection bias. Additional research regarding the effects of online training on social isolation may be helpful.

Similar to the findings by Royal and colleagues, our findings revealed that diversity-related factors appeared to impact isolation.17 A student being a non-native English speaker was significantly associated with social isolation, and qualitative comments were noted listing specific concerns among international and minority students. Interestingly, an American-born PhD student also noted feeling isolation and loss of identity within a cohort rich with diversity (ie, the America-born student was in the minority). Given the ongoing underrepresentation of minorities among most health care students, physicians, and faculty members, the tendency for social isolation among these groups is likely to continue.24,25 Often students from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds congregate together, however, programs should consider purposeful steps to enhance inclusion.26 Strategies such as diversity training, peer mentorship programs in which students with similar backgrounds are paired, or purposeful social programming that celebrates student diversity (eg, cultural “pot luck” picnic) may be useful.26Another possible strategy is purposeful design in classroom seating. Though some students may find comfort sitting with a group of classmates they resemble, this may isolate and prevent them from learning from larger peer groups.27 Purposeful design can be used to maximize diversity, or at least minimize the likelihood of active or passive exclusion.27

Quantitative analysis revealed that student caregivers were more likely to be socially isolated; likewise, thematic analysis noted difficulty developing connections with classmates while maintaining studies and fulfilling family obligations. In 2006, the National Survey of Student Engagement found that nontraditional students, 70% of whom were female and caring for family members, were not as likely to engage in activities such as community service, research projects with faculty members, and cocurricular activities.28 However, more female students completed the study, so there may have been an increased risk for self-selection by those with these responsibilities. Goncalves and Trunk conducted a small study of nontraditional undergraduate students in which all participants expressed difficulty interacting with others to some degree (eg, inability to mingle, feeling isolated and alone, and an overall lack of interaction with peers), but described interactions with professors more positively.29 Nontraditional students in Goncalves and Trunk’s study stated they would be interested in joining groups designed for students like them stating, “it would be nice to meet other people that are feeling the same stressors and feelings like my kids never see me; things that traditional students wouldn’t understand.”29 Efforts to make programs more inclusive of family and to offer “family-friendly” activities, particularly ones where faculty members are involved, may be a way to reduce isolation in this student subset, and make choices between school and family less burdensome. Given that some students indicated feeling different from peers and isolated because of a disinterest in drinking alcohol, holding social gatherings that are alcohol free and family-friendly may engage both of these student groups.

Numerous students in the professional pharmacy program focused on competition as a barrier to socialization. Specific comments centered on lack of trust in others because of the competitive nature within the academic program or the need to purposely isolate because of the internal drive to compete. A previous study of the relationship between loneliness (measured using the UCLA Loneliness Scale) and competitiveness identified differences in perception of loneliness based on type of competition and gender.30 Superiority competitive orientation (a need to feel superior to others to validate oneself) is rewarded as a masculine characteristic, allowing men to befriend other men, gain feelings of self-worth, and protect against loneliness.30 In contrast, women who exhibit superiority competitiveness may be alienated from other women, leading to more isolation and loneliness.30 More studies are needed to determine if delineations of competitiveness, with or without reference to gender, contribute to social isolation in these students.

Related to competitiveness, a specific concern of students was the need to compete to increase individual attractiveness to residency programs as programs may seek candidates based on examination scores or overall academic performance, which is typically determined by grade point average (GPA).31-33 A possible reason for pharmacy to stand out among other professional programs that seek residency placement is the use of a traditional GPA-based grading system by pharmacy education, whereas the colleges of medicine and dentistry do not employ such a model. Furthermore, in the college of pharmacy, GPA was the primary determinant of student scholarship awards at the time of the survey. More study is needed to determine whether movement to a non-GPA based grading system by some pharmacy programs affects overall placement in residency, competition, and social isolation.

Some students felt purposely excluded by others, affecting their ability to develop meaningful social relationships. For instance, despite working with an entirely adult population, the formation of cliques that exclude others still appears to be an issue. Royal describes the clique issue in a commentary and advocates for occasional assigned seating in allied health professional programs.27 Purposeful attempts to mix things up, eg, randomly assigned seating, may challenge students to meet and learn about peers with whom they may have never otherwise conversed. In the colleges studied, this was accomplished simply by having students choose a folded piece of paper with a random table assignment written on it. In the professor’s informal assessment of this method, she noted less distraction and greater student engagement during class.

The main theme impacting social isolation in the qualitative analysis was a lack of time because of programmatic workload or corresponding requirements. This theme supported quantitative findings indicating students spent an average of 24.3 (SD=17.2) hours studying, 4 (SD=8.1) hours commuting to and from class, and 2.2 (SD=3.4) hours participating in extracurricular activities (although we were not always able to determine whether extracurricular hours were program related). These activities (averaging over 30 hours weekly) were in addition to attending class, indicating a significant student time investment in meeting program requirements. In contrast, students spent an average of 7.2 (SD=7.2) hours socializing. This may highlight the need to include opportunities for social interaction as part of the planned curriculum and co-curriculum.

Some of the strongest concerns were expressed by some PhD students regarding their inability to socialize because of their workload, and feelings that there was no way to improve this situation. In a study of a similar population, Ali and Kohun cited graduate students whose confusion about the program and requirements led to feelings of being left behind and overwhelmed.34 The same students described concerns of insufficient or no communication among students and between students and faculty members.34 Establishing a comprehensive orientation process for new graduate and health professions students, conducting periodic check-ins with these students, and pairing them with peer mentors are a few strategies to decrease isolation in these students.

Program design and involvement in collegiate activities were cited as helpful in fostering interaction with students and decreasing their feelings of isolation. This was particularly noteworthy among dental respondents, which may be reflective of an on-campus but largely in-clinic experiential component of the program’s design. The student to full-time faculty ratio in dental school of 3:1 may also serve as an indirect measure of interaction levels, engagement, and academic support.35 Encouraging students to form new or join existing social support groups through the program or externally should be a priority in isolation prevention efforts. Opportunities to engage with professional fraternities in service projects and socially, as well as in other extracurricular activities were mentioned as valuable. Universities could consider inviting graduate students to professional student social events and vice versa, as well as planning interprofessional social events to create a more inclusive health care student campus.

Students lacking a strong support system were more likely to experience social isolation, as were those with negative “lonely” indicators on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. In contrast, those who felt it possible to discuss feelings with friends and those with positive “non-lonely” items on the scale were less likely to experience social isolation. These findings are consistent with Russell’s original work in which he validated the scale among college students.18 Of those indicating strong social support systems in the study, types of support included family, classmates, non-classmate friends, religious groups, and non-religious campus groups. Multiple students mentioned that the support of friends and family had been essential during their training.

Strategies for fostering social engagement are needed to enhance communication and ensure a sense of belonging of students as well as connection to faculty members. Physical spaces may be designed in a fashion that encourages socialization: a model that mirrors that of the former “doctor’s lounge.” These spaces are making a resurgence in clinical environments as a way to help coworkers engage with each other and reduce burnout.36 Casual activities and interaction with faculty members aim to improve communications and relationships between students and faculty members and may serve as a foundation upon which mentorship can flourish. The goal is to ensure students come out of classrooms, clinics, and laboratories to engage and develop meaningful relationships with one another, faculty members, and others within and beyond their campus community.

Student well-being is of paramount concern, not only for the sake of individual health, but to develop healthy practitioners who are able to care for others. Research has established a link between social support, burnout, work satisfaction, and productivity, with social connectivity resulting in greater psychological well-being, higher productivity, and better performance.6 If social isolation in health professional students can be prevented by monitoring for risk, implementing interventions to improve meaningful socialization, and teaching students strategies to optimize wellness, perhaps rates of student burnout can be lowered and wellness optimized.

This study had some limitations. Survey questions did not assess for participation in online courses, the presence of mental illness, or use of drugs or alcohol. We depended on each college to disseminate the email with link to the survey, so participation varied. Participant self-selection may have occurred due to an unintended incentive for pharmacy students to complete the survey because of familiarity with the investigators. Generalizability may be limited to Midwest health care schools and students in programs with a similar structure of delivery (particularly pharmacy, public health, and nursing programs), and may not be representative of medicine and dentistry programs. There is a need for more studies to clarify whether additional factors (such as online education) may influence isolation, to identify what types of preventive interventions are most impactful, and to determine the consequences of social isolation on outcomes such as mental health or professional productivity.

CONCLUSION

The study aims were addressed through quantitative and qualitative data (student comments) gathered using a comprehensive survey instrument. This study revealed nearly one-fifth of graduate and professional health care student- respondents indicated they experienced social isolation. Numerous factors are associated with increased risk; social isolation is more likely to occur in students with no strong support system, in those who are non-native English speakers and in those needing to care for family members or dependents. In contrast, ample support systems help students remain engaged with others. Creation of a purposeful plan for monitoring for social isolation and proactive engagement of students at risk through a variety of modalities, may be helpful in fostering inclusion and increasing the perceived value of student interactions with peers and faculty. The goal is ultimately to create engaged, healthy, and competent practitioners.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lisa DuBrava for formatting the survey instrument, manuscript and tables, and creation of Figure 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.McIntosh WL, Spies E, Stone DM, Lokey CN, Trudeau AT, Bartholow B. Suicide rates by occupational group-17 states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(25) doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6525a1. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm6525.pdf Accessed May 9, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deeb GR, Braun S, Carrico C, Kinser P, Laskin D, Golob Deeb J. Burnout, depression and suicidal ideation in dental and dental hygiene students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1111/eje.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout andsuicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs SR, Dodd DK. Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. J Coll Stud Dev. 2003;44(3):291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cobb S. Presidential address-1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976;38(5):300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sochos AB, Bowers A. Burnout, occupational stressors, and social support in psychiatric and medical trainees. Eur J Psychiat. 2012;26(3):196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3 Suppl):S39–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro J, Zhang B, Warm EJ. Residency as a social network: burnout, loneliness, and social network centrality. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;(Dec):617–623. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00038.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zavaleta D, Samuel KS, Mills C. Social isolation: A conceptual and measurement proposal. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative OPHI WORKING PAPER. 2014;67 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(10):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cigna, Ipsos. Cigna U.S. loneliness index. Survey of 20,000 Americans examining behaviors driving loneliness in the United States. 2018. https://www.multivu.com/players/English/8294451-cigna-us-loneliness-survey/docs/IndexReport_1524069371598-173525450.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018.

- 14.Cacioppo JT, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, et al. Lonely traits and concomitant physiological processes: the Macarthur social neuroscience studies. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;35(2-3):143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brazeau CM, Shanafelt T, Durning SJ, et al. Distress among matriculating medical students relative to the general population. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1520–1525. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vora RS, Kinney MN. Connectedness, sense of community, and academic satisfaction in a novel community campus medical education model. Acad Med. 2014;89(1):182–187. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal KD. Medical students rate black female peers as less socially connected. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell DW. UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meeuwesen L. A typology of social contacts. In: Hortulanus Roelof, et al., editors. Social Isolation in Modern Society. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uiowa/detail.action?docID=261321. Accessed May 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2011.

- 23.Institute for Digital Research and Education of University of California Los Angeles. What does Cronbach’s alpha mean? SPSS FAQ. https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/spss/faq/what-does-cronbachs-alpha-mean/#/ . Accessed May 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grumbach K, Mendoza R. Disparities in human resources: addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):413–422. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan LW, Suez Mittman I. The state of diversity in the health professions a century after flexner. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):246–253. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowman NA, Park JJ. Interracial contact on college campuses: comparing and contrasting predictors of cross-racial interaction and interracial friendship. J Higher Ed. 2014;85(5):660–690. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Royal KD. 10 reasons to assign seats in allied health program classrooms. J Allied Health. 2018;47(1):e37–e39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Postsecondary Research-Engaged Learning: Fostering Success for All Students. National Survey of Student Engagement Annual Report. 2006 http://nsse.indiana.edu/NSSE2006AnnualReport/docs/NSSE2006AnnualReport.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goncalves SA, Trunk D. Obstacles to success for the nontraditional student in higher education. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research. 2014;19(4):164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kayhan E. Two facets of competitiveness and their influence on psychological adjustment. Honors Projects. Paper 4; 2003; Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=psych_honproj Accessed May 9, 2018.

- 31.Phillips JA, McLaughlin MM, Rose C, Gallagher JC, Gettig JP, Rhodes NJ. Student characteristics associated with successful matching to a PGY1 residency program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(5):Article 84. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp C, Plank A, Dove J, et al. The predictive value of application variables on the global rating of applicants to a general surgery residency program. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(1):148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harfmann KL, Zirwas MJ. Can performance in medical school predict performance in residency? A compilation and review of correlative studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.034. e1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali A, Kohun F. Dealing with isolation feelings in is doctoral programs. Int J Doctoral Stud. 2006;1 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Top 100 universities with the best student-to-staff ratio. Retrieved from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/top-100-universities-best-student-staff-ratio. Accessed May 9, 2018.

- 36.The Johnson Foundation at Wingspread. Physician burnout in America: A roadmap for restoring joy and purpose to medicine. https://omahamedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/A-Roadmap-for-Restoring-Joy-and-Purpose-to-Medicine.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018.