Abstract

An implantable collamer lens® (ICL) V4c model (STAAR Surgical, Monrovia, CA, USA) was placed in the eye of a 31-year-old male patient with high myopia followed by the development of malignant glaucoma. After failing medical treatment for 5 days, a noncomplicated pars plana vitrectomy and anterior hyaloidectomy succeeded in breaking the aqueous misdirection. Sixteen months later, intraoperative miotics were purposefully withheld from the ICL surgery in the fellow eye and malignant glaucoma did not develop. Even though the patient's visual acuity postoperatively was 20/20, OU, a single small atrophic iris patch in the affected eye resulted in slightly more halos and glare in mesopic conditions as compared to the fellow eye. Earlier surgical intervention may have prevented iris ischemia and iridocorneal touch with its subsequent iris atrophy and resulted in an even more favorable visual outcome. Withholding intraoperative miotics during ICL surgery appeared to be beneficial in this case.

Keywords: Glaucoma, implantable collamer lens, malignant glaucoma

Introduction

Malignant glaucoma is a rare complication that has been reported in four cases following implantable collamer lens® (ICL) (STAAR Surgical, Monrovia, CA, USA) implantation.[1,2,3] Even though the exact physiopathology of malignant glaucoma is not clear, anterior rotation of the ciliary body followed by the accumulation of aqueous within the posterior segment is the most acceptable theory proposed by Shaffer.[4]

To better understand the mechanism and the most appropriate treatment for malignant glaucoma post-ICL surgery, we discuss this complication in a patient with bilateral ICL implantation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of malignant glaucoma following implantation of ICL with a good overall visual outcome enough for the patient to carry on with ICL surgery in the fellow eye.

Case Report

A 31-year-old male patient with bilateral high myopia presented for refractive surgery. His best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes (OD: −11.00, OS: −12.50 + 0.50 × 95). Both eyes were to receive an ICL. Left eye was to be operated on first.

A single peripheral Nd: YAG laser iridotomy was performed at 12 o'clock, 2 months preoperatively in both eyes.

On the day of surgery, a full preoperative pupillary dilation was achieved using tropicamide drops. Under general anesthesia, an ICL V4c model (−13.00 D, VICMO 12.6 mm) was inserted in the anterior chamber (AC) through a 3.0-mm corneal incision at 3 o'clock. After repositioning the ICL behind the iris, the viscoelastic was removed using irrigation. Miochol®-E (acetylcholine chloride intraocular solution) was injected in the AC at the end of the procedure, and all wounds were irrigated with balanced salt solution.

On the 1st postoperative day, the patient presented with eye pain and blurry vision; anterior displacement of lens–iris diaphragm was noted on slit-lamp examination with an AC depth approximating 1 corneal thickness centrally. Furthermore, a closed angle was noted on gonioscopy in addition to a high intraocular pressure (IOP). The iridotomy was patent and there were no signs of pupillary block. Ultrasound B ruled out suprachoroidal hemorrhage and vaulting of the ICL was excluded by an anterior-segment optical coherence tomography. Hence, the diagnosis of malignant glaucoma was made.

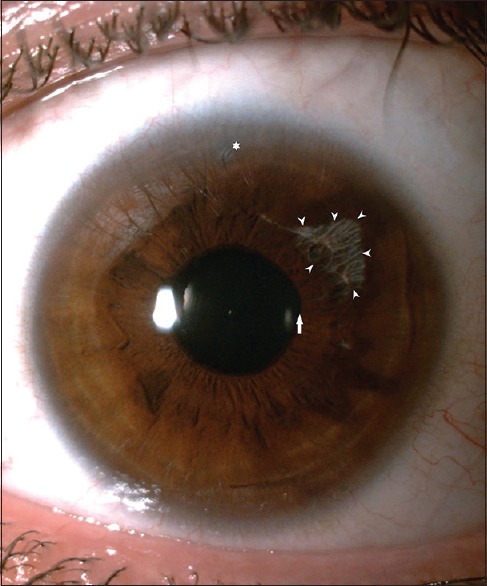

Medical treatment (combination of topical brimonidine/timolol, bimatoprost, brinzolamide, and atropine, in addition to oral acetazolamide) failed over the following 5 days to normalize the pressure and reform the AC. Subsequently, a noncomplicated posterior pole 20-gauge vitrectomy with disruption of the anterior hyaloid face was performed, leading to resolution of the aqueous misdirection and normalization of IOP. The patient achieved 20/20 uncorrected visual acuity with excellent placement of his ICL. However, a relatively small single area of iris atrophy secondary to iridocorneal touch along with a slightly dilated pupil developed [Figure 1], causing mild halos and glare under mesopic conditions.

Figure 1.

Slit-lamp photography of the left eye 18 months postvitrectomy showing a superotemporal iris atrophic patch (arrowheads) and a mildly dilated pupil with minor border irregularity (arrow). Peripheral iridotomy (asterisk)

Sixteen months later, an ICL V4c model (−12.00 D, VICMO 12.6 mm) was implanted in the right eye. The same operative technique was used except for purposefully withholding the intraoperative Miochol®-E. The postoperative period was uncomplicated, with an uncorrected visual acuity of 20/20.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a unilateral malignant glaucoma following bilateral ICL implantation. A thorough literature review revealed four cases of malignant glaucoma post-ICL surgery [Table 1].[1,2,3,5] None of these cases had a favorable overall visual outcome to undergo ICL implantation in the fellow eye.

Table 1.

Implantable Collamer Lens studies reporting the occurrence of malignant glaucoma along with treatment

| Article | Operative use of miotics | Eyes with aqueous misdirection | Preoperative refraction | Years | Surgical treatment | Sequela |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senthil et al.[5] | Yes | 1 | Not available | 2016 | Peripheral irido-zonulo-hyaloido-vitrectomy along with AC reformation | Pupillary sphincter atrophyDilated fixed pupilSegmental angle closure |

| Kodjikian et al.[1] | Yes | 1 | Myopia | 2002 | Radial sclerotomy + ICL removal | Localized iris atrophyPartial mydriasis |

| Almalki et al.,[2] | Yes | 1 | Myopia | 2016 | Not available | - |

| Rosen and Gore[3]* | Yes | 1 | Hyperopia | 1998 | Vitrectomy + lensectomy | - |

*Aqueous misdirection was preceded by a pupillary block. ICL: Implantable collamer lens, AC: Anterior chamber

Three theories might explain the occurrence of aqueous misdirection: ciliary body irritation and inflammation leading to anterior rotation of the ciliary process,[5] laser iridotomy,[6] or the use of miotics.[7] Fourman proposed that miotic therapy was the inducing factor of malignant glaucoma postlaser iridotomy since all the reported cases of aqueous misdirection postiridotomy received pilocarpine and it would be impossible to implicate the performance of a laser iridotomy as the primary cause.[8]

The surgical technique in all four reported cases of aqueous misdirection post-ICL implantation included intraoperative Miochol. In our case, the preoperative AC depth was similar in both eyes, laser iridotomy was performed preoperatively bilaterally, the ICL implants were inserted by the same experienced surgeon (J.K.) using the same technique, and both implants had similar dimensions. The only difference between both surgeries was the intraoperative use of Miochol in the affected eye, which, according to the aforementioned literature, could have contributed to the aqueous misdirection.

As such, withholding miotic agents from routine ICL surgery, especially when the surgeon is comfortable with the ICL placement behind the iris, could help prevent malignant glaucoma. Should the use of miotics be necessary, we recommend that they be used judiciously.

Medical management (mydriatic drops, antiglaucoma drugs, and mannitol) is the first line of treatment in malignant glaucoma. However, it has a low success rate of <50%.[9] If medical treatment is unsuccessful in phakic patients, pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with hyaloidotomy is the treatment of choice with a high success rate.[9]

In cases of malignant glaucoma, especially in ICL surgery patients, a timely resolution of the aqueous block is necessary to ensure a desirable overall postsurgical outcome. As such, establishing an early and correct diagnosis is crucial, having a preoperative patent iridotomy is helpful, and shortening the course of medical treatment in favor for an early PPV and hyaloidotomy is recommended.

Even though our patient's uncorrected visual acuity postoperatively was 20/20, OU, a single small atrophic iris patch in the affected eye resulted in slightly more halos and glare under mesopic conditions as compared with the fellow eye. Earlier surgical intervention may have prevented iridocorneal touch and ischemia and resulted in an even more favorable visual outcome.

Having an eye with malignant glaucoma increases the risk of its occurrence in the fellow eye.[10] It is possible that in this case, withholding intraoperative miotics helped prevent aqueous misdirection in the fellow eye.

Conclusion

We recommend withholding miotic agents from routine ICL surgery, especially when the fellow eye has malignant glaucoma. Early vitrectomy in cases of malignant glaucoma post-ICL implantation may result in a more favorable overall visual outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Clinical significance

it is not a necessary paragraph, it is an addition to the article and you can decide to keep it according to the journal's guidlines.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kodjikian L, Gain P, Donate D, Rouberol F, Burillon C. Malignant glaucoma induced by a phakic posterior chamber intraocular lens for myopia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:2217–21. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almalki S, Abubaker A, Alsabaani NA, Edward DP. Causes of elevated intraocular pressure following implantation of phakic intraocular lenses for myopia. Int Ophthalmol. 2016;36:259–65. doi: 10.1007/s10792-015-0112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen E, Gore C. Staar collamer posterior chamber phakic intraocular lens to correct myopia and hyperopia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24:596–606. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(98)80253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffer RN. The role of vitreous detachment in aphakic and malignant glaucoma. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1954;58:217–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senthil S, Choudhari NS, Vaddavalli PK, Murthy S, Reddy JC, Garudadri CS. Etiology and management of raised intraocular pressure following posterior chamber phakic intraocular lens implantation in myopic eyes. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodes BL. Malignant glaucoma after laser iridotomy. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1641–2. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)38526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieser JC, Schwartz B. Miotic-induced malignant glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972;87:706–12. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1972.01000020708018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fourman S. “Malignant” glaucoma post laser iridotomy. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1751–2. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)38531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dave P, Senthil S, Rao HL, Garudadri CS. Treatment outcomes in malignant glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders PP, Douglas GR, Feldman F, Stein RM. Bilateral malignant glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 1992;27:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]