Abstract

Objective

To investigate the prevalence of Burnout syndrome (BS) with its emotional exhausting (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA) dimensions among Turkish urologists.

Material and methods

A total of 2,259 certified Turkish urologists were invited by e-mail to participate in this cross-sectional survey-based study. An online survey was conducted to evaluate three dimensions of BS ie: -EE, DP and PA-and their association with socio-demographic variables of Turkish urologists using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).

Results

Of the 2259 urologists contacted, 362 (with a mean age of 44±9.9 years) completed the survey. The mean EE, DP and PA scores were 16.8±8.7, 6.6±4.6 and 8.2±5.6, respectively. Cronbach’s α reliability co-efficiencies were 0.920 for EE, 0.819 for DP and 0.803 for PA. Antidepressant drug usage was quite prevalent among participants (21.9%), and the most common comorbidity was hypertension (13%). The academic title, age, smoking status, monthly income and relationships between colleagues and employers were associated with BS (p<0.05).

Conclusion

The prevalence of BS among Turkish urologists is quite prevalent in terms of EE and DP subscales and may negatively affect the psychosocial status and well-being of the urologists. In this study, a high prevalence of BS has been reported among Turkish urologists. In conclusion the BS could become an important occupational and health problem, if it is not properly managed.

Keywords: Burnout, depersonalization, emotional exhausting, personal accomplishment, urology

Introduction

Burnout Syndrome (BS) is defined as the impairment in an individual’s professional and/or social relationships due to emotional overloading, with chronic fatigue and feelings of disappointment and failure.[1] Psychosomatic reflections accompanied by emotional devastation and physical symptoms, such as headaches, dizziness, dyspnea and sleep disturbances may occur when BS is not adequately addressed.[2] Maslach and Jackson described the three dimensions of BS. The first dimension, emotional exhaustion (EE), occurs when one begins to get tired of work and lose the mental energy needed for the accomplishment of the work.[3] As the burnout worsens, the individual begins to view patients as objects rather than humans. This second stage is called depersonalisation (DP) and it is actually a natural defensive mechanism for coping with stress.[4] Ineffective coping, and defense mechanisms frequently result in a decrease in personal accomplishment (PA) and success.[5]

Health care professionals who work for longer hours assume a high level of responsibility in terms of their positions, so they are prone to the development of BS. Such working conditions lead to physical and mental exhaustion which, in turn, result in psychosomatic and sleep disorders, adverse attitudes towards people and, in the health care field, to reduced quality of care and decreased patient safety.[6,7] Dewa et al.[8] reported that the national cost of BS for all physicians was over $200 million in Canada due to early retirement and reduced clinical hours.

According to Turkey’s Health Education and Human Resource Report published in 2014, the overall 2,259 urologists are working in public and private practice in our country.[9] Considering the population of Turkey in 2014, the number of urologists per 100,000 people is 3, which is almost the half of that reported in Europe (5.9/100,000). This daily workload, heterogeneous distribution of urologists around the country,[10] and the dizzying technological improvements in the field, together with increased medicolegal responsibilities, might increase the incidence of BS.

The presence of BS in different specialties has long been investigated, with overall rate of 30–40% among all physicians.[11,12] However, data regarding the prevalence of BS among urologists are lacking in the literature. In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of BS among Turkish urologists and, to identify the individual predisposing factors for the development of this condition.

Material and methods

From March to September 2017, 362 participants were enrolled in this study. More than 2,000 actively working certified urologists and urology residents were invited by e-mail to participate in this cross-sectional survey-based study. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Ondokuz Mayıs University (KAEK 2016/7413), and all participants were informed about object of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A power analysis was performed to determine the number of participants needed. The survey was based on the responses derived from the sociodemographic questionnaire and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (Appendix 1).

Appendix 1.

Maslach Burnout Inventory-validated Turkish form

| Maslach Tükenmişlik Ölçeği | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aşağıda kişilerin ruh durumlarını ifade ederken kullandıkları bazı cümleler verilmiştir. Lütfen her bir cümleyi okuyarak hangi sıklıkta hissettiğinizi size uyan seçeneğe işaret koyarak belirtiniz. | Hiçbir zaman | Yılda birkaç defa | Ayda birkaç defa | Haftada birkaç defa | Hergün | |

| 1. Kendimi işimden duygusal olarak uzaklaşmış görüyorum | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2. İş gününün sonunda kendimi bitkin hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 3. Sabah kalkıp yeni bir işgünü ile karşılaşmak zorunda kaldığımda, kendimi yorgun hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 4. Hastalarımın pek çok şey hakkında neler hissettiğini anlayabilirim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 5. Bazı hastalarıma onlar sanki kişilikten yoksun bir objeymiş gibi davrandığımı hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 6. Bütün gün insanlarla çalışmak benim için gerçekten bir gerginliktir. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 7. Hastalarımın sorunlarını etkili bir biçimde halledebilirim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 8. İşimin beni tükettiğini düşünüyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 9. İşimle diğer insanların yaşamlarını olumlu yönde etkilediğimi hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 10. Bu mesleğe başladığımdan beri insanlara karşı katılaştığımı hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 11. Bu iş ben duygusal olarak katılaştırdığı için sıkıntı duyuyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 12. Kendimi çok enerjik hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 13. İşimin beni hayal kırıklığına uğrattığını düşünüyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 14. İşimde gücümün üstünde çalıştığımı düşünüyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 15. Bazı hastalarımın başına gelenler gerçekten umurumda değil. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 16. Doğrudan insanlarla çalışmak bende çok fazla strese neden oluyor. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 17. Hastalarım rahat bir atmosferi rahatça sağlayabilirim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 18. Hastalarımla yakın ilişki içinde çalıştıktan sonra kendimi ferahlamış hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 19. Bu meslekte pek çok değerli işler başardım. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 20. Kendimi çok çaresiz hissediyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 21. İşimde duygusal sorunları bir hayli soğukkanlılıkla hallederim. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 22. Hastaların bazı problemleri için beni suçladıklarını düşünüyorum. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics were assessed using 24 questions. The MBI, which was also validated in Turkish, consisted of 22 Likert-type questions used to assess EE (Questions 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 13, 14, 16 and 20), DP (Questions 5, 10, 11, 15 and 22), and PA (Questions 4, 7, 9, 12, 17, 18, 19 and 21).[13] EE scores were graded as follows: low, 0–11 pts; moderate, 12–17 pts and high, >17 pts. DP scores were graded as follows: low, 0–5 pts; moderate, 6–9 pts and high, ≥ 10 pts; and PA scores as: low, 0–21 pts, moderate, 22–25 pts and high ≥26 pts. No consensus exists on classification in the MBI scale, and the interpretation was undertaken giving equal weight to all three dimensions or by giving greater weight to at least one dimension.[14]

The reliability of the Maslach burnout scale was evaluated using the Cronbach’s α value. Accordingly, if 0.00 ≤α<0.40, the scale is not reliable; if 0.40 ≤α<0.60, the scale has a lower reliability; if 0.60 ≤α<0.80, then the scale is rather reliable, and if 0.80 ≤α<1.0, reliable.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA) 18.0 for windows. Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (min-max) and frequency (%). Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze normally distributed quantitative data. Analysis of data with non-normal distribution was performed using Mann-Whitney U test and the comparison of frequencies was done using Pearson’s chi-square test. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used for reliability of the MBI test results. A p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 369 participants responded to the survey, and seven were excluded due to missing information. Majority of the participants were aged 41 to 60 years (47.9%) with a mean age of 44±9.9 (range: 23 to 75 years). Most (65.1%) of the respondents were certified urologists while only 6.9% were urology residents.

Antidepressant use was common among the participants (21.8%). The most common comorbidities were hypertension (13%), peptic ulcus (9.4%), lower back pain (9.1%) and sleep disorders (6.9%). Ninety-nine (27.3%) of them were active smokers. Table 1 summarizes the demographics and professional status of the responders.

Table 1.

The demographic features of participants

| Variable | n, (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) (years) | 44±9.9 |

| <40 | 156 (43.1) |

| 41–60 | 183 (50.6) |

| >60 | 23 (6.3) |

|

| |

| Academic title | |

| Urology resident | 25 (7.2) |

| Urologist | 224 (64.9) |

| Associated professor | 47 (13.5) |

| Professor | 50 (14.4) |

|

| |

| Institution | |

| Statel hospital | 72 (19.9) |

| Training and research hospital | 107 (29.6) |

| University hospital | 76 (21.0) |

| Private hospital | 96 (26.5) |

| Unknown | 11 (3.0) |

|

| |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 17 (4.7) |

| Married | 326 (90.1) |

| Divorced | 16 (4.4) |

| Other 3 | (0.8) |

|

| |

| Number of children | |

| 0 | 38 (10.5) |

| 1 | 105 (29.1) |

| 2 | 177 (49.0) |

| 3 | 31 (8.6) |

| >4 | 11 (3.0) |

|

| |

| How the faculty of medicine was preferred? | |

| Willingly | 320 (88.4) |

| Family request | 42 (11.6) |

|

| |

| How the urology residency was preferred? | |

| Willingly | 336 (92.8) |

| Family request | 26 (7.2) |

|

| |

| Monthly income | |

| <10.000 TL | 207 (57.2) |

| 10.000–20.000 TL | 128(35.4) |

| >20.000 TL | 27 (7.4) |

|

| |

| Satisfaction with montly income | |

| Yes | 40 (11.0) |

| No | 235 (65.0) |

| Partly | 87 (24.0) |

|

| |

| Antidepressant use | |

| Yes | 79 (21.8) |

| No | 283 (78.2) |

|

| |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 47 (13) |

| Peptic Ulcus | 34 (9.4) |

| Lumbalgia | 33 (9.1) |

| Sleep disturbance | 25 (6.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (5.9) |

| Major depression | 7 (1.9) |

| Malignancy | 5 (1.4) |

| Tuberculosis | 1 (0.3) |

|

| |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 99 (27.3) |

| No | 263 (72.7) |

TL: Turkish Lira. 1 USD=3.75 TL, 1 Euro=4.65 TL

The mean EE, DP and PA scores were 16.8±8.7, 6.6±4.6 and 8.2±5.6, respectively (Table 2). Table 3 categorizes the participants according to the three dimensions of BS. The reliability of the MBI was also evaluated (Table 4). The Cronbach’s α value was found to be reliable for all three subdivisions of the inventory.

Table 2.

The mean subdimensions levels of the Maslach Burnout inventory

| Subdimensions of Maslach | |

|---|---|

| Burnout inventory | Scores (mean±SD) |

| Emotional exhausting | 16.8±8.7 |

| Depersonalization | 6.6±4.6 |

| Personal accomplishment | 8.2±5.6 |

Table 3.

Stratification of the participants according to burnout subgroups

| Burnout level | Emotional exhausting, n | Depersonalization (%) | Personal accomplishment, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 102 (29.7) | 169 (48.5) | 330 (97.6) |

| Moderate | 80 (23.2) | 83 (23.9) | 6 (1.8) |

| High | 162 (47.1) | 96 (27.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Total | 344* (100) | 348* (100) | 338* (100) |

Number of the participants who responded individual emotional exhausting, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment

Table 4.

Cronbach’s α reliability coefficiency

| Subdivisions of Maslach Burnout Inventory | Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient |

|---|---|

| Emotional exhausting | 0.920 |

| Depersonalization | 0.819 |

| Personal accomplishment | 0.803 |

| 0.00≤α<0.40: Not reliable; 0.40≤α<0.60: Lower reliable; 0.60≤α<0.80: Rather reliable; 0.80≤α<1.0: Reliable | |

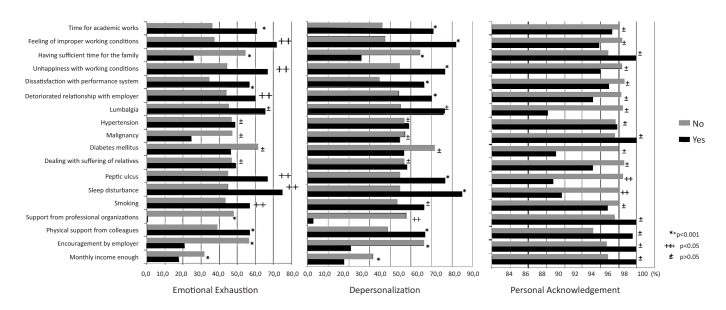

The factors affecting the burnout level are provided in Figure 1. There was a statistically significant association between the academic title and burnout level. The EE score was found to be high in 60% of the urology residents, 52.1% of the urologists, 36.2% of the associated professors and 26.7% of the professors (p=0.001). DP scores were also higher in urology residents when compared to residents of other academic fields (p=0.001). Interestingly, academicians working in more than one institution had greater mean EE (26.5±3.7) but lower DP scores (5.0±2.7). PA scores, on the other hand, were not correlated with the academic title (p=0.06).

Figure 1.

Demographic variables and relationship between three dimensions of burnouts

Majority of the participants were married (90.2%), and 49% of them had two children. Within the married group, low, moderate and high EE, and DP levels were detected in 30.2 vs 56%, 23.3 vs 23.2% and 23.3% vs 26.1% of the participants, respectively. Low, moderate and high EE, and DP levels were detected in 56 vs 23.2%; 26.1 vs 25%, and 18.8, vs 56.3% of unmarried participants, respectively (p=0.45).

The monthly income of the participants is presented in Table 1. Only 11.1% of the participants were satisfied with their salaries whereas 64.9% of them were not (p=0.001). Within the group of participants that were satisfied with their incomes, the EE and DP scores were low in majority of the participants (61.5% and 78.9%, respectively: p=0.001). The association of individual EE and DP dimensions with smoking status was also evaluated (Table 1). The higher EE and DP scores were found to be associated with smoking status (p=0.03).

Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, malignant diseases and dealing with the suffering of relatives were not associated with any dimension of BS (p>0.05). The indicated percentages of participants receiving support from professional organisations had low (66.7%) and moderate (33.3%) EE scores, while all of them (100%) had low DP scores; whereas greater percentages of participants not receiving such support had higher EE (low, 29%; moderate, 23.1% and high, 47.9%) (p<0.001) and higherDP scores (47.7% low, 24.3% moderate and 28% high) (p<0.05).

Encouragement of the urologists by a chief or employer led to a decrease in EE (48.9%) and DP (56.6%), and increase in PA scores (99.5%) in respective percentages of responders (p=0.001). Having a sleep disturbance (6.9%) and using antidepressant drugs (21.9%) for more than 6 months were associated with higher EE and DP scores and lower PA scores in indicated percentages of participants (p=0.001). Similar findings were also obtained for the peptic ulcus (Figure 1).

The EE and DP scores were lower for participants who spent sufficient time with their families (p=0.001). Physical professional support from colleagues was associated with decreased EE score (55.5% vs 40%, p=0.003) and higher PA scores (p=0.002) (Figure 1). Participants who were unhappy with their jobs had a higher EE (58.7% vs 42.9%) and DP scores (43.6% vs 21.7%) (p=0.001). In the presence of improper working conditions, both EE (71.9%) (p=0.01) and DP (46.9%) scores were found to be higher (p=0.001), respectively. Finally, according to the current performance system, dissatisfaction based on the reimbursement system was found to be higher in EE (34.5% vs 56.6%) and DP dimensions (19.3% vs 33.8%) compared to satisfied participants (p=0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, firstly the present study has investigated the prevalence of BS among Turkish urologists. The prevalence rates for EE, DP, and PA were 47.1%, 27.6, and 91.4%, respectively. The highest proportion of EE was expected to be due to emotional or physical overload, in addition to the lack of availability of continuous scientific education. The prevalence of BS was between 55–87% among the physicians in the literature due to daily heavy workload and the necessity of continuous scientific education to obtain advanced knowledge in the field.[15]

Of the participated urologists, 43.2% were under 40 years of age, and the highest EE score was shown in this group (51.8%). Majority of the participants (50.6%) were aged between 41 and 60 years, and this age group showed high EE (45.4%). Only 6.2% of the participants were above 61 years old with high EE scores (25%) demonstrating that urologists older than age 61 had a low level of burnout. Our findings are similar with the results of previously published data. In a systematic review of 47 papers published by Amofao et al.[16], younger age, long working hours and low job satisfaction were associated with a higher degree of burnout. Although Malik et al.[17] reported that age had no significant effect on burnout, they only included 133 surgical residents with a younger population. Increasing experience has been shown to be associated with increased job satisfaction and a low burnout level, but if a physician was not satisfied with his job, neither age nor experience had a significant impact on job satisfaction.[18] In the context of age, we predicted that younger urologists were more prone to experience severe burnout. Higher academic titles were associated with lower burnout levels (Table 5). Academicians had low EE and DP compared to urology specialists and urology residents. The increased workload, bureaucratic formalities and greater working hours faced by urology residents and urology specialists might result in a rise in burnout scores. Indeed, academicians working in private institutions in addition to their primary institution had greater EE and DP scores (p=0.02).

Table 5.

The mean subdimensions of burnout according to academic titles

| Academic title (n) | Emotional exhausting (mean±SD) | Depersonalisation (mean±SD) | Personal accomplishment (mean±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urology residents | 18.4±6.3 | 8.9±4.3 | 10.4±5.1 |

| Urologist | 18.1±8.9 | 7.1±4.8 | 8.8±5.7 |

| Assoc. Professor | 14.9±8.3 | 6.0±3.9 | 7.4±5.9 |

| Professor | 11.9±7.4 | 4.0±3.3 | 5.4±4.7 |

| Average | 16.8±8.7 | 6.6±4.6 | 8.2±5.6 |

In a study by Karamanova et al.[19], the mean EE and DP scores of health professionals from seven South and Southeastern European countries were reported as 31.9% and 33.2%, respectively. They reported higher percentages of EE and DP scores in Turkish health professionals (53.8% and 58.9%, respectively). According to Turkey’s Health Education and Human Source Report published in 2014, the number of physicians per capita is two-fold higher in European countries (5.9/100,000) relative to Turkey (3/100,000) which could be a cause of the high burnout rate.

Although burnout is reported in the literature as a risk factor for clinical depression, neoplasms and cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases,[20] our results showed no relationship between burnout and diabetes mellitus, malignancy, lumbalgia or hypertension (Figure 1). Our results showed a relationship between burnout and peptic ulcus. Although a PubMed search for ‘burnout’ and ‘peptic ulcus’ found no results, the association between high stress and the risk of peptic ulcus is well documented in the literature.[21]

The prevalence of depression may be affected by geographical, socio-economical and methodological factors. The highest rate in South America (20.6%), and the lowest rate in Africa has been reported (11.5%).[22] The rate of actual depression could not be provided in the present study, because our questionnaire did not include the following question: “Do you still use antidepressant treatment?” However, more frequent use of antidepressants among our participants is in accordance with the positive correlation between burnout and psychogenic status demonstrated in the literature.[23]

It is not surprising that all three dimensions of burnout were associated with sleep disturbances. In the current study, 6.9% of the participants had a sleep disturbance; which is compatible with the literature.[24] Although being single was associated with burnout in the literature,[25] we found no statistical significant correlation between these two parametres in our study. However, having children had a positive impact on EE and DP scores. Indeed, many studies have found a relationship between childlessness and high burnout levels.[19]

Our study showed that monthly income was associated with two dimensions of burnout (EE and DP), although Ebling et al.[26] stated that low monthly income caused only high DP scores. They explained that finding using the current status of their institution as an example. Similarly, smoking, in our study, was also associated with burnout (high EE and DP scores) though Kang et al.[27] found that it was not significantly associated with occupational stress. The inconsistency between these studies is probably due to their limited number of participants.

Although we found no association between diabetes mellitus and burnout, in a study, burnout was linked to a 1.84 fold increased risk of diabetes mellitus type 2 after adjusting affecting parameters to account for the low number of diabetic participants.[28] Participants who were well treated by their employers had lower burnout levels than others. Mental well-being was shown to effect favourably psychosocial working conditions and, thereby, it can be considered as an important tool in the prevention of BS.[29]

Maslach and Leiter[30] proposed that support from family and colleagues is one of the most important tools in the prevention of burnout. Both professional support from colleagues and supervisors and personal support from family and friends can effectively prevent the development of burnout. However, no clear recommendations or definitions are made regarding support from family members or colleagues. Our findings have also demonstrated that spending time with families or colleagues outside of the work environment is associated with reduced burnout in support of the recommendations of Maslach.

In this study, we have reported that urologists suffer from increased prevalence of burnout, which can be a significant health care problem if not properly managed. In fact, most of the factors leading to BS can be remedied. Effective management and treatment of these factors can play a critical role both in preventing emergence of legal problems and improving the quality of health care. In turn, this approach will also preclude potential economic losses across the country.

Our study has shown that BS among Turkish urologists is quite prevalent, at least regarding EE and DP dimensions. However, these dimensions are preventable. Occupational measures could help to promote psychosocial well-being, reduce the incidence of burnout among urologists and improve the quality of health care.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Ondokuz Mayıs University School of Medicine (KAEK 2016/7413).

You can reach the questionnaire of this article at https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2018.34202

Informed Consent: This study was carried out among urology specialists and therefore no consent was obtained from the participants in the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., A.Y.M.; Design – M.S.B., L.T., F.A., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K.; Supervision – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Resources – M.S.B., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Materials – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Data Collection and/or Processing – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., E.Y., F.A., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Literature Search – M.S.B., E.A., E.Y., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Writing Manuscript – M.S.B., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.; Critical Review – M.S.B., L.T., E.A., A.Y.M., E.Y., F.A., A.K., Ö.Ç., Ü.Ö.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Freudenberger HJ. The Staff BS in Alternative Institutions. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1975;12:73–82. doi: 10.1037/h0086411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturgess J, Poulsen A. The Prevalence of burnout in occupational therapists. Occup Ther Ment Health. 1983;3:47–60. doi: 10.1300/J004v03n04_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garden AM. Depersonalisation, a valid dimension of burnout? Human Relations. 1987;40:545–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory (Manual) 2nd Edition. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shannafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallett K, Price JH, Jurs SG, Slenker S, Mallet K. Relationships among burnout, death anxiety and social support in hospice and critical care nurses. Psychol Rep. 1991;68:1347–59. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.68.3c.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:254. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Ministry of Health of Turkey Health Statistics Yearbook. 2014. Available from: URL: https://sbu.saglik.gov.tr/Ekutuphane/kitaplar/EN%20YILLIK.pdf.

- 10.The Ministry of Health of Turkey Health Statistics Yearbook. 2014. Available from: URL: http://ekutuphane.sagem.gov.tr/kitaplar/saglik_istatistikleri_yilligi_2015.pdf.

- 11.Freudenberger HJ. Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues. 1974;30:159–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rick J, Briner RB. Psychosocial risk assessment: Problems and prospects. Occup Med. 2000;50:310–4. doi: 10.1093/occmed/50.5.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dikmetaş E, Top M, Ergin G. An examination of mobbing and burnout of residents. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011;22:137–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucanduva LT, Garcia AP, Prudente FV, Centofanti G, Souza CM, Monteiro TA, et al. A síndrome da estafa profissionalem médicos cancerologistas brasileiros. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2006;52:108–12. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302006000200021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tironi MOS, Teles JMM, Barros DS, Vieira DFVB, Silva Filho CMS, Júnior DFM, et al. Prevalence of BS in intensivist doctors in five Brazilian capitals. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2016;28:270–7. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20160053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amofao E, Hanbali N, Patel A, Singh P. What are the significant factors associated with burnout in doctors? Occupational Medicine. 2015;65:117–21. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik AA, Bhatti S, Shafiq A, Khan SR, Butt UI, Bilal SM, et al. Burnout among surgical residents in a lower-middle income country-Are we any different? Ann Med Surg. 2016;9:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabir MJ, Heidari A, Etemad K, Gashti AB, Jafari N, Honarvar MR, et al. Job Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Related Factors among Health Care Workers in Golestan Province, Iran. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2924–30. doi: 10.19082/2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karamanova AA, Todorova I, Montgomery A, Panagopoulou E, Costa P, Baban A, et al. D Burnout and health behaviors in health professionals from seven European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016;89:1059–75. doi: 10.1007/s00420-016-1143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adam S, Cserhati Z, Meszaros V. High Prevalence of Burnout and Depression May Increase The Incidence Of Comorbidities Among Hungarian Nurses. Ideggyogy Sz. 2015;68:301–9. doi: 10.18071/isz.68.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deding U, Ejlskov L, Grabas MP, Nielsen BJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Bøggild H. Perceived stress as a risk factor for peptic ulcuss: a register-based cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:140. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0554-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Is burnout a depressive disorder? A reexamination with special focus on atypical depression. Int J Stress Manage. 2014;22:307. doi: 10.1037/a0037906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Scientific Rep. 2018;8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S. Burnout and Doctors: Prevalence, Prevention, and Intervention. Healthcare (Basel) 2016;4 doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030037. pii: E37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galván ME, Vassallo JC, Rodríguez SP, Otero P, Montonati MM, Cardigni G, et al. Professional burnout in pediatric intensive care units in Argentina. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2012;110:466–73. doi: 10.5546/aap.2012.eng.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebling M, Carlotto MS. BS and associated factors among health professionals of a public hospital. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2012;34:93–100. doi: 10.1590/S2237-60892012000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang SH, Boo YJ, Lee JS, Ji WB, Yoo BE, You JY. Analysis of the occupational stress of Korean surgeons: a pilot study. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:261–6. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2013.84.5.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study of apparently healthy employed persons. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:863–9. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000242860.24009.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thinschmidt M, Deckert S, Then F, Hegewald J, Nieuvenhuijsen K, Riedel-Heller S, et al. Los 1: Der Einfluss arbeits bedingter psychosozialer Belastungs faktoren auf die Entstehungpsychischer Beeinträchtigungen und Erkrankungen. Dortmund: Fed Inst OccupSaf Health (BAuA); 2014. Systematischer Review zum Thema, Mentale Gesundheit/Kognitive Leistungsfähigkeitim Kontext der Arbeitswelt. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103–11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]