Abstract

A multi-step Volterra integral equation-based algorithm was developed to measure the electric field auto-correlation function from multi-exposure speckle contrast data. This enabled us to derive an estimate of the full diffuse correlation spectroscopy data-type from a low-cost, camera-based system. This method is equally applicable for both single and multiple scattering field auto-correlation models. The feasibility of the system and method was verified using simulation studies, tissue mimicking phantoms and subsequently in in vivo experiments.

1. Introduction

Quantitative in vivo imaging of blood flow using laser speckles have been investigated by several researchers in the past. Some of the techniques for quantifying blood flow includes, laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) [1–3], laser doppler flowmetry (LDF) [4,5], diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS) [6–8] and its three dimensional tomographic extension called diffuse correlation tomography (DCT) [9–11]. While LSCI and LDF have been used to quantify blood flow in relatively superficial layers of tissue, the deep tissue blood flow is quantified using DCS and DCT.

The seminal work to employ laser speckles for imaging blood flow was reported in Ref [12], where the time integrated speckles recorded using camera was used to photograph blood flow in human retina. Although limited to the imaging depth of approximately 1 mm, LSCI provided inexpensive and faster way of real time blood flow imaging with relatively simpler optical instrumentation. Based on LSCI method, multi-exposure recording of the speckle data was utilized for a quantitative recovery of absolute flow which is termed as multi-exposure speckle contrast imaging (MESI) [13]. In MESI, the measured multi-exposure speckle contrast images were fitted against single scattering flow models to quantify the flow.

Meanwhile the possibility of extending the dynamic light scattering to account for multiple scattering was explored in [14,15], which resulted in the development of diffusing wave spectroscopy (DWS). In DWS, under the ergodicity assumption, the temporal auto-correlation of the intensity speckles were utilized to measure the dynamics of the media [16,17]. Subsequently, the development of the correlation diffusion model led to diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS) which is extensively used in measuring deep tissue () blood flow [8,18–20].

A single channel DCS system comprises of a sensitive and expensive photo counting device like photon multiplier tube (PMT) or avalanche photo diode (APD) along with a hardware or software auto-correlator [6,8]. In this regard, usually multi channel acquisition systems are desired, as employing many detectors at a given spatial location improves the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the system [21]. Also inorder to spatially resolve the blood flow, leading to a diffuse correlation tomography (DCT) system, many source detector (SD) pairs have been employed. For instance, in Ref. [9], 24 SD pairs were used to image over an area of , while Ref. [11] used 48 SD pairs to scan the area of in rat brain. One of the primary requirements of DCS/DCT system is many source detectors pairs which makes it a relatively expensive imaging modality. A solution to the above mentioned problem was proposed by Speckle Contrast Optical Spectroscopy (SCOS) by employing a camera, wherein each pixel of the camera acts a detector to simultaneously measure time integrated speckles for deep tissue flow imaging in Ref. [22,23], for both phantoms as well as invivo studies. SCOS employed a quantitative recovery of the flow by using the correlation diffusion model [6,8] and noise corrected speckle contrast measurements.

SCOS was further extended to achieve three dimensional tomographic imaging of blood flow as presented in Ref. [24] termed as speckle contrast optical tomography (SCOT). A high density version of SCOT was successfully applied to generate the tomographic images of the reduction in cerebral blood flow during local ischemic stroke in mice brain [25]. In Ref. [26], an electron multiplying charge coupled device (EMCCD) camera was employed to generate three dimensional flow images, in phantoms. Several successive publications have discussed the utility of employing array detectors like CCD or CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) camera to probe tissue blood flow by measuring the speckle contrast data [27–32]. A compact version of SCOS using single photon avalanche diode (SPAD) array sensor was introduced in [33], wherein the flow was quantified using a multi-exposure speckle contrast measurement.

In a theoretical perspective, all the aforesaid methods were based on a relation connecting speckle contrast to normalized field auto-correlation [34] which in turn is related to flow. The speckle contrast is a time average over exposure of the normalized field auto-correlation. Hence, a multi-exposure speckle contrast data was used to quantify flow using least square minimization, without attempting to recover the field auto-correlation function [13,23,33]. A direct intensity auto-correlation measurement of blood flow is not possible due to the relatively larger exposure time of the camera which results in the time averaged measurements. Utilizing CCD / CMOS camera to directly measure intensity auto-correlation function has been attempted for DWS studies in Ref [35]. However the dynamics of the media utilized in this study, is slower when compared to dynamics of blood flow. Recently interferometric DCS has been attempted in Ref. [36], to measure blood flow using a CMOS camera, which is based on the principle of multi-mode fiber based interferometry.

In this paper, using a new algorithm, we present an inexpensive system using low frame rate CCD or CMOS cameras which can be employed for the recovery of the DCS data-type for blood flow measurements. To the best of our knowledge, an inexpensive, low-frame rate camera has not been previously used to recover the full auto-correlation function, i.e. the DCS data-type. The algorithm is based on multi-step Volterra integral method (MVIM) [37] which uses multi-exposure speckle contrast measurement to recover the normalized field auto-correlation. Though the speckle contrast, at a given exposure, has averaged out the correlation decay, we retrieve the field auto-correlation function from multi-exposure speckle contrast data using MVIM. We demonstrate the system and method in imaging flow in tissue mimicking phantoms and also during human hand-cuff occlusion experiment. By recovering field auto-correlation function from multi-exposure speckle contrast data, we also prove that, speckle contrast infact contains information on the field auto-correlation. This fact is demonstrated by multi-exposure speckle contrast methods, as reported in previous publications [13,23,33], wherein the flow is quantified directly by least square fitting against speckle contrast.

2. Multi-step Volterra integral method (MVIM): theory and algorithm

The relation connecting speckle contrast () and normalized electric field auto-correlation function () is given by

| (1) |

Here, is the speckle contrast given at a source detector separation and at exposure time , is the correlation delay time and is the experimental constant accounting for the collection optics. In order to recover at each source detector separation and for all relevant ’, we pose the Eq. (1) in terms of volterra integral equation of first kind [38] as follows,

| (2) |

where the term is called the kernel defined as . With these definitions, the problem to recover field auto-correlation function using MVIM is stated as follows: Given for all T and for every source detector separation , find for all . The selection of range of ’ and ’ will be discussed later.

The standard method to solve volterra integral equations requires the kernel to be non-zero at [39]. Since the kernel in Eq. (2) violates this condition, we adopt the method given in Ref. [37] to solve the integral equation. In simpler terms, the method suggests to introduce a small shift in by , so that as they differ by . The Eq. (2) is valid for every source detector (SD) separation and hence we can drop the argument from the function henceforth.

The MVIM algorithm to recover field auto-correlation was implemented numerically by discretizing the integral in Eq. (2) using trapezoidal integral rule as given below,

| (3) |

Here, h is the step size, N is the number of discretization of the interval and n is the index of the discretization. In matrix form, the above equation can be represented as,

The above matrix equation is of the form , where is the kernel matrix, corresponds to , and is the measurement . For simulation studies, speckle noise was added by using the noise model given in [32,40] . The standard deviation of the above-said noise model is given by , where P is the number of pixels used for calculating speckle contrast.

The matrix A is a lower triangular matrix and hence the best way to solve the above matrix equation is to apply the method of successive substitution. But due to the practical difficulties of measuring a dense multi-exposure speckle contrast data and the presence of associated noise, we adopted Tikhonov regularized least square minimization to solve the above matrix equation. The cost function was minimized for x, where is the regularization parameter determined by L-curve method [41] and is the prior information on . Three parameters that play a key role in the above minimization problem are correlation delay time , exposure time (T) and the prior information (). The optimal selection of the above parameters for the better recovery of , is explained in the following sections.

2.1. Optimal selection of minimization parameters

2.1.1. Correlation delay time

Let the range of at which we seek the normalized field auto-correlation function , be . By looking at the limits of integration of Eq. (1), it is clear that should be restricted to , which is the maximum exposure time. Hence, the maximum allowed correlation delay time . The value of has to be selected depending on the characteristic correlation delay time () of the sample under measurement. To capture correlation decay, should be selected such that .

The correlation delay time step was determined by comparing the accuracy of the numerical solution of Eq. (1) against the analytical solution. The numerical speckle contrast was obtained by applying a trapezoidal integration to Eq. (1). The expression for analytical speckle contrast to Eq. (1) for single scattering case is given by , where ; Here the field auto-correlation model used was [34]. We select such that the percentage error between and was less than a pre-determined value.

2.1.2. Exposure time T

The range of the exposure time needed to generate multi-exposure speckle contrast data are often limited by the dynamic range of the camera. We adopted the speckle contrast sensitivity analysis, wherein the sensitivity is defined as as given in [40,42] , to find an optimal exposure time. In Ref. [42], it was proved that the speckle contrast has maximum sensitivity when T equals , the characteristic decay time of the sample. Although the above scenario was shown to hold for single scattering case as in LSCI, we have found that it is equally applicable for diffusing regime as well (see section 4.1). Hence was to be chosen as , while was chosen to cover the whole correlation decay. We found that of approximately 100 time (where ) serves the purpose.

2.1.3. Prior information

While minimizing the cost function to recover the field auto-correlation, the selection of prior, i.e., , plays a crucial role. When , the value of normalized field auto-correlation function will tend to unity, i.e. and hence we chose for appropriately small values. Note that the prior is a function of and hence by implies it has a value of unity for all ’. This assumption, can lead to certain errors between the actual and reconstructed and hence we also adopt an iterative scheme to update the prior at each iteration.

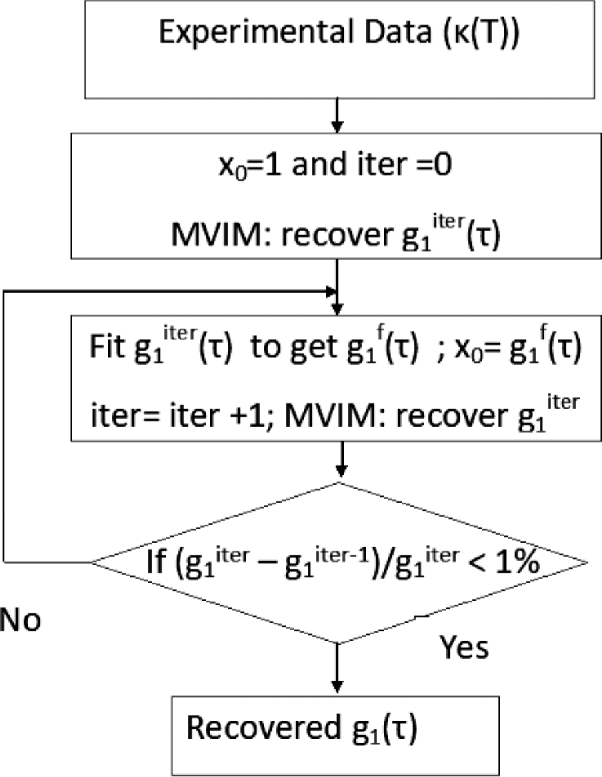

2.2. Iterative algorithm for MVIM

As explained above, we adopt an iterative algorithm to update the prior at each iteration by fitting the recovered against the appropriate model. The flow chart of the iterative scheme is shown in Fig. 1. The algorithm starts by recovering using MVIM with a prior of for all relevant . The recovered was fitted for or for the cases of multiple scattering or single scattering respectively. The Correlation Diffusion Equation (CDE) was used as the model for multiple scattering [6] while single scattering utilizes simple model like [34]. The corresponding to fitted or was used as the prior to next iteration. This process was continued till the percentage error between two consecutive recovered lies below a tolerance level. Note that the prior information from second iteration will not be unity for all values, instead it will move closer to actual to be recovered. In case the model is unknown (as in the case of two layer or multi layer models), we may choose to fit for an empirical model: such as , where a,b,c,d are the coefficients of fit.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of Iterative MVIM scheme: Here at each iteration the prior is updated by fitting the recovered against the appropriate model.

3. Experimental method

3.1. Proposed system

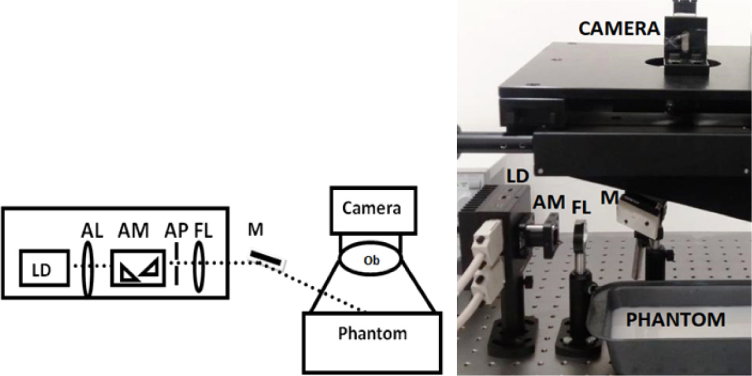

The experimental setup to validate the proposed method to measure field auto-correlation function using an inexpensive low frame rate camera is given in Fig. 2. A current and temperature controlled laser diode (785 nm, 90 mW, Thorlabs), with beam shaping optics (aspheric lens, anamorphic prism, aperture and focusing lens) was used to form a pointed source of diameter less than 1 mm diameter. The beam was focused to the sample (tissue or phantoms) and the scattered intensity was measured using a CCD camera (Basler acA-640-120-um) in the reflection geometry. An objective lens of focal length of and f-number of 8 was used to match the speckle size to pixel size of the camera. Additionally, a LSCI system was developed for single scattering case wherein uniform illumination was produced by using diffusers.

Fig. 2.

Experimental Setup of the proposed system using low frame rate camera. LD - Laser Diode; AL- Aspheric Lens; AM- Anamorphic Prism; AP - Aperture; FL- Focusing Lens; M - Mirror; Ob - Objective lens.

The scattered intensity from the phantom or tissue at different exposure times () were recorded by the camera. The speckle contrast was calculated temporally over 500 frames and was corrected for dark and shot noise as given in [23,24]. To calculate speckle contrast at a given Source Detector SD separation () with high SNR (Signal to Noise Ratio), we defined detectors in form of annuals (or rings) with radius from the source with inner and outer diameters being and respectively [23]. The speckle contrast that falls within these detectors for a given was averaged and was used as speckle contrast for a given SD separation and this was repeated for every exposure time T.

3.2. Tissue mimicking phantoms

To create tissue mimicking phantoms of varying dynamic properties, two phantoms based on Intralipid (Fresenius Kabi India, Intralipid ) were made. The phantoms, one with distilled water as base (hereafter denoted as “Intralipid phantom”) and another with glycerol as base (hereafter denoted as “Glycerol phantom”) were prepared as per the recipe given in [23,43,44]. The absorption coefficient () and the reduced scattering coefficient () of both the phantoms were estimated by fitting against the analytical solution of diffusion equation [45]. The and of intralipid phantom () was estimated to be and respectively and while that of glycerol phantom () was and respectively. The value of was determined by calculating at small exposure time T, such that . In addition, flow phantoms were made, where the flow was controlled using a syringe pump (NewEra pump systems Inc.). The liquid phantoms were made to flow on a semi circular shaped tube, embedded on silicon elastomer cavity (Slygard 184 mixed with ), with a diameter such that, the light does not interact with the boundaries of the supporting cavity and hence the semi-infinite geometry for light propagation can be adopted.

3.3. In vivo experiment

To show the feasibility of working of the proposed method to measure field auto-correlation function for in vivo tissues, we have performed a human forearm cuffing experiment, wherein the blood flow in human arm was occluded by using a standard sphygmomanometer. This work was undertaken with approval of the Institute Ethical Committee of the Indian Institute of Technology - Bombay, Approval Number: IITB-IEC/2018/017. The optical properties such as and were calculated from the scattered intensity data by fitting it against the solution of diffusion equation [46]. The multi-exposure speckle contrast data was acquired at pre-occlusion, occlusion and post-occlusion phases (measured after 120 s from releasing the cuff of sphygmomanometer). This multi-exposure speckle contrast data was used for recovering normalized field auto-correlation function () using MVIM. The blood flow index (BFI), which is [8], was quantified from the recovered field auto-correlation, where the quantification can be carried out using CDE model (Green’s function solution used in this work) [8] or using other approximations such as the modified Beer Lambert law for DCS [47,48] or high order linear algorithms based on Monte Carlo using Taylor polynomial expansion [49,50].

4. Results

We have validated the MVIM algorithm, to measure field auto-correlation function using the camera based system, by both numerical simulations as well as experimental measurements. We have shown the numerical results for both single scattering and multiple scattering cases. Subsequently, we have also experimentally validated our method by tissue mimicking phantoms and human in vivo experiments.

4.1. Validation of MVIM using numerical simulations

In this section, we present the numerical simulations to validate MVIM for both single and multiple scattering regimes. The single scattering model for field auto-correlation utilizes as in LSCI [13,34], whereas, the CDE was used to generate field auto-correlation for multiple scattering as adopted in DCS [6]. Trapezoidal integration rule was adopted to evaluate the integral in Eq. (1) to compute the speckle contrast for the assumed auto-correlation models. As mentioned in Section 2, speckle noise model given in [32,40] was used to add noise to the simulated speckle contrast data.

The simulated multi-exposure speckle contrast data generated as mentioned above was fed to the MVIM algorithm presented in Section 2. We have chosen an optimal exposure time by computing the sensitivity of speckle contrast to exposure time. The sensitivity shows a maximum, when the exposure time equals the characteristic decay time, i.e., [42]. Hence the multi-exposure speckle contrast data will be sensitive to the characteristic decay time of the sample, if the exposure time is selected in the vicinity of . Here we have selected T such that, and utilize the speckle contrast data to recover using MVIM.

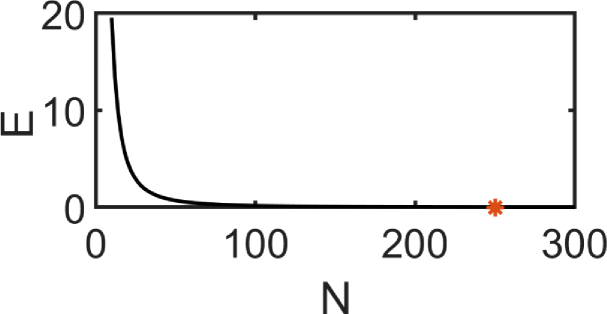

The range of correlation delay time , at which we seek the field auto-correlation function , was selected to be . The correlation delay time step was determined by comparing the accuracy of the numerical solution of Eq. (1) against the analytical solution as mentioned in section 2. A plot of percentage error (E) between the and for a single scattering case against the number of ’ (in the range of to with ) is shown in Fig. 3. We have used , where the percentage error is almost negligible, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Plot between Number of , N, and percentage error () indicating that at around 250 intervals the percentage error is almost negligible (less than 0.002%)

The dependence of recovered on the prior information was explained in the section 2, where the rationale for adopting an iterative scheme was mentioned. We present simulation results of the MVIM algorithm under following special cases: (a) With and without prior i.e., and respectively, (b) with an optimal exposure range i.e., and (c) iterative scheme as explained in section 2 (see Fig. 1). In addition, we also present the recovery of for a two layer model (i.e. particle diffusion coefficient assumes two different values in two different layers) wherein we computed the corresponding speckle contrast data using a Finite Element Method (FEM) based forward solver for CDE [51]. Here exhibits two different decay characteristics corresponding to each layers which was also recovered successfully using MVIM.

4.1.1. Single scattering

In the single scattering case, we have used the normalized field correlation model of the form [13,34]. We have used two different values, which are and to generate and from the analytical models [34]. Note that we have added speckle noise only to the speckle data generated for to differentiate the cases with and without noise. For the samples, with characteristic time and , the exposure ranges, i.e. to , used were to and to respectively. The number of exposures used was 50, spaced equally in the above exposure range in logarithmic scale for both the samples.

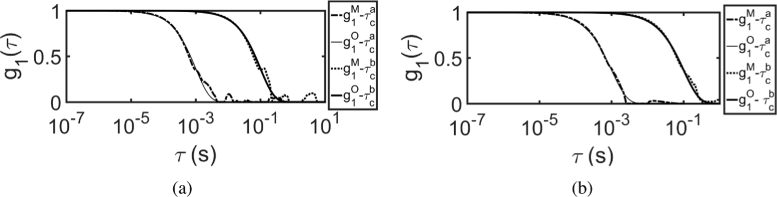

Figure 4(a) shows the recovered from for two different values, where the prior information is chosen to be . Here the exposure time was not chosen optimally with respect to . Instead, a wide range of T, such that was used to generate the simulated multi-exposure speckle contrast data. The recovered shows a transient from 0 to unity for lower values (, which was ) due to fact that is chosen to be zero. Figure 4(b) shows similar plots for the case, where . The initial transient of as seen in Fig. 4(a) is absent here because of the fact that prior is now at , which causes the minimization problem to search for an optimal solution in the vicinity of .

Fig. 4.

Recovered from using MVIM compared against original , where (a) without prior information i.e., was used and (b) prior information i.e., was used. and indicates the original and recovered respectively.

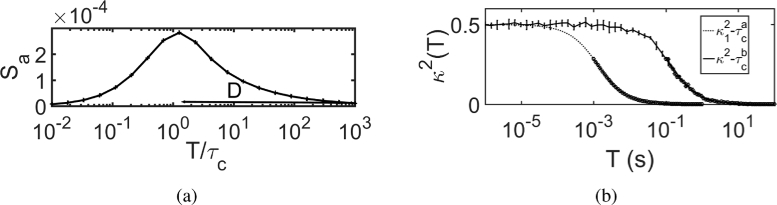

Measuring speckle contrast for a wide range of exposure time is practically not feasible and hence we adopt the sensitivity analysis as described before to find an optimal exposure time. The sensitivity curves which plots against is shown in Fig. 5(a). Here the range D shows the optimal set of exposure times T, where T . The speckle contrast data is plotted against the exposure time in Fig. 5(b), wherein the range of optimal exposure time (i.e., range D in Fig. 5(a)) used to recover has been highlighted. By employing MVIM, we recover from the above mentioned optimal exposure time T, such that T and the recovered is shown in Fig. 6(a). It shows several ripples specifically for larger values, which is due to the fact that number of ’ at which the is sought, is larger than the number of exposure values used. Note that, in this case, the prior information was used in recovery of . The noise added to multi-exposure data and the prior information () also contributes to the above mentioned ripples.

Fig. 5.

(a) Sensitivity curves plotted as a function of , indicating that speckle contrast () has a maximum sensitivity, when ; The range “D” indicates the region of data (), where . (b) Speckle contrast data plotted against exposure time, where highlighted region shows speckle contrast for T which belongs to region D. Here and corresponds to values of and respectively.

Fig. 6.

Recovery of by using MVIM from , with optimal exposure time T, , when (a) is used as prior (b) Iterative method is used to update the prior information.

In order to minimize the ripples, we decided to adopt an iterative algorithm for MVIM as discussed in Section 2.2, where the prior was updated by fitting against single scattering model (see Fig. 1). The results of the iterative scheme are shown in Fig. 6(b), where amount of ripples is reduced. The residual between the original and the recovered is shown in Fig. 7(a) and 7(b) for the above-said two values by using iterative scheme. The recovered is fitted for using the single scattering model for field auto-correlation and the residual norm between original and recovered , is tabulated in Table 1. The results in the Table 1 suggest that employing MVIM using appropriate prior and optimal exposure along with an iterative scheme, ensures a better recovery of field auto-correlation function from multi-exposure speckle contrast data.

Fig. 7.

Residual between original and recovered using MVIM by iterative scheme (plot in Fig. 6(b)), is shown for (a) , i.e., noiseless data (b) , i.e., noisy data case

Table 1. Table comparing original and recovered values and residual norm , where the first two rows shows the recovered without and with prior and the third row shows the recovered , with speckle contrast data in optimal exposure range. The fourth row shows recovered and residual norm for the iterative scheme.

| MVIM based recovered fitted to (in seconds) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without noise | With noise | |||

|

| ||||

| Prior | ||||

| Prior | ||||

| With optimal exposure | ||||

| Iterative scheme | ||||

4.1.2. Multiple scattering

The analytical solution of CDE was used for simulating the normalized field auto-correlation function for multiple scattering case [6,46]. The and used were and respectively and SD separation of 1 cm was used. Two different particle diffusion coefficients , i.e. and were used and the speckle noise was added to the latter (speckle contrast data corresponding to ) using the noise model mentioned in Section 2. The exposure range i.e., to used were to and to 100 s for and samples respectively with 50 exposures equally spaced in logarithmic scale.

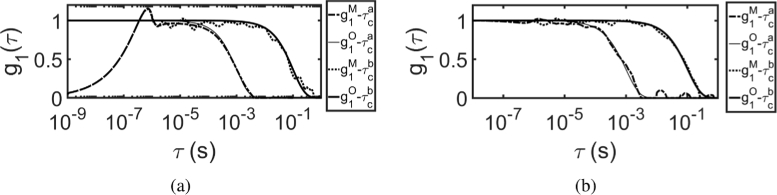

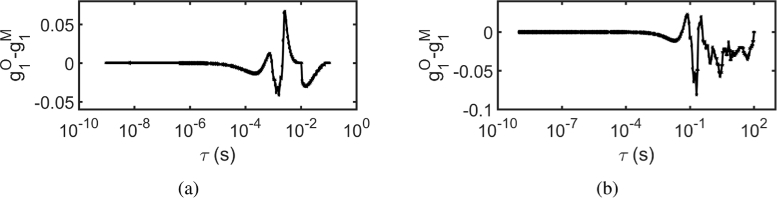

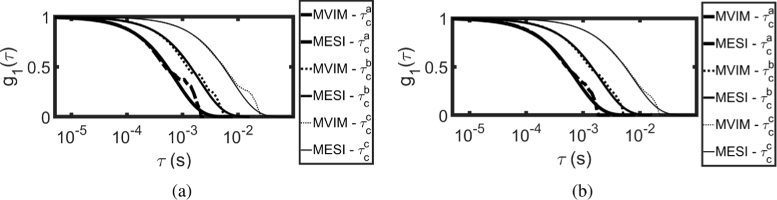

Figure 8 shows the results of MVIM method, where has been recovered from multi-exposure speckle contrast data. Figure 8(a) shows the recovered normalized field auto-correlation using MVIM, when no prior information, i.e., , was used for two different values and it can be seen that there is transient curve from 0 to 1 at . Different exposure ranges were used for different samples to demonstrate the initial transient curve during recovery, when no prior information, i.e., was used. Here, from Fig. 8(a), we see that can only be recovered for , such that , when no prior information i.e. is used. Similarly, Fig. 8(b) shows the plot for the case where the prior information was used. As seen in Fig. 8(b), the initial transient curve is absent due to use of prior information . Here, a wide range of exposure time T, i.e., were used.

Fig. 8.

Recovered at r = 1 cm using MVIM, from for (a) without prior information i.e., (b) with prior information i.e., ; (c) Sensitivity curve is plotted as a function of [42], where was chosen as time , when . From this curve it can be seen that maximum sensitivity is achieved, when ; Recovered from by (d) using optimal exposure range i.e., (e) iterative scheme; (f) Residual between original and recovered using iterative scheme. Here the superscript M in the legend indicates that it is MVIM recovered and O indicates that it is original

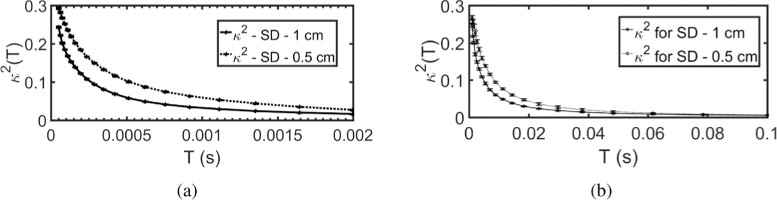

We adopt the sensitivity analysis as described in single scattering case, where is plotted against as shown in Fig. 8(c). Although the relation between and has been derived in [48], we choose to follow a simpler method of choosing such that . The values were and for the samples and respectively. The optimal exposure time T is chosen such that and is recovered as shown in Fig. 8(d). To utilize the prior information in an adaptive manner for better reconstruction, the iterative scheme as described in Section 2 (Fig. 1) was used. The results of iterative scheme based recovery of is shown in Fig. 8(e). The residual between the original and recovered for the noisy speckle contrast data (iterative scheme) is shown in Fig. 8(f). The recovered was fitted for by using CDE model and is tabulated in Table 2, along with the residual norm between the original and recovered .

Table 2. Table comparing original and recovered and residual norms , for multiple scattering case, where the first two rows shows the recovered without and with prior and the third row shows the recovered , with speckle contrast data in optimal exposure range. The fourth row shows recovered for the iterative scheme.

| MVIM based recovered fitted to (in ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without noise | With noise | |||

|

| ||||

| Prior | ||||

| Prior | ||||

| With optimal exposure | ||||

| Iterative scheme | ||||

4.1.3. Two layer model

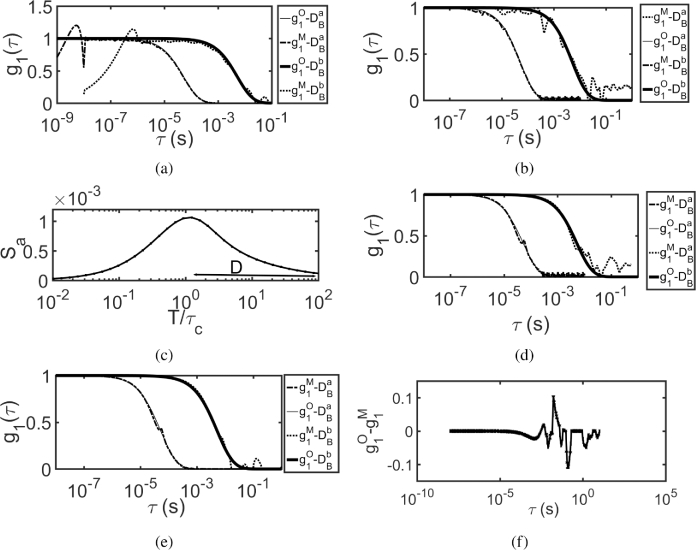

In order to validate our method in two layer tissue models, we have simulated the auto-correlation function, using FEM based forward solver [51] for CDE. The sample has two different values for two layers (first layer up to 1 cm thickness with and the other layer of ) and the SD separation was 2 cm with and . The multi-exposure speckle contrast () was computed numerically using Eq. (1) and statistical noise was added [42]. The exposure range used was to with 50 exposures spaced in logarithmic scale with a decorrelation time () of . Figure 9 shows the results of MVIM based recovery of for a two layer model. Figure 9(a) shows the original and recovered using MVIM, when prior information, was used. Figure 9(b) and (c) shows the similar plots, wherein was recovered from the noise added speckle contrast, by using prior information and iterative scheme respectively. Figure 9(d) shows the sensitivity curve, as discussed in single scattering case, with two maxima’s indicating that there are two different flows (or values).

Fig. 9.

By employing MVIM, we have recovered at r = 2 cm for a two layer model for (a) without prior i.e., (from without noise) (b) with prior information i.e., (from with noise) (c) by iterative scheme (from with noise) (d) Sensitivity curves indicating that there are two peaks, as there are two different flows.

4.2. Experimental results: validation of MVIM algorithm

4.2.1. Single scattering

The experimental system shown in Fig. 2 (as explained in section 3) was modified to generate LSCI data (). The speckle contrast was calculated from 500 images with 20 exposures in equally spaced in logarithmic scale with different exposure ranges for different flows due to limited dynamic range of the camera. For flow , the exposure range was to . Similarly for and , the exposure ranges used were, to and to respectively. From the multi-exposure speckle contrast data (), by using MVIM, was recovered and was fitted for using the analytical model of .

Figure 10(a) shows the recovered using MVIM with prior information, , and compares it with , computed for fitted by MESI [13]. Figure 10(b) shows similar plot, wherein iterative scheme was employed. As the flow increases, the shifts towards left indicating the increase in flow. Table 3 compares the values of MESI and MVIM based methods and it can be seen that they are in reasonable agreement with one another.

Fig. 10.

Recovery of by using MVIM from and compared with MESI fitted , when (a) used as prior (b) iterative scheme used to update the prior.

Table 3. Comparison of MVIM Fitted and MESI Fitted , indicating that they are in reasonable agreement with one another.

| MVIM fitted | MESI Fitted | |

|---|---|---|

4.2.2. Multiple scattering

A laser source was focused on to the sample to form a point source as shown in Fig. 2 and the multi-exposure speckle contrast data was measured. As mentioned in Section 3, the speckle contrast was measured for a SD separation of 0.5 and 1 cm for both intralipid and glycerol phantoms at different exposures. For the calculation of speckle contrast, we have used 500 frames with 20 exposure times ranging from to for intralipid phantom and to for glycerol phantom. The multi-exposure speckle contrast data as a function of exposure time at two different SD separations are shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Speckle Contrast plotted as a function of Exposure time T, with mean and Standard deviation (repeated 5 times) for (a) intralipid Phantom and (b) glycerol Phantom

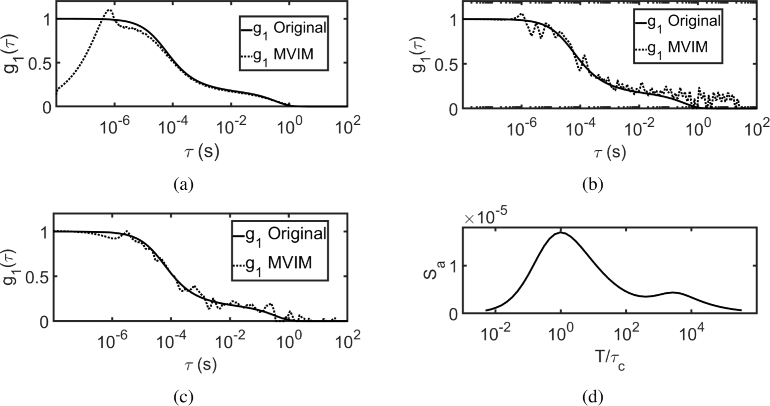

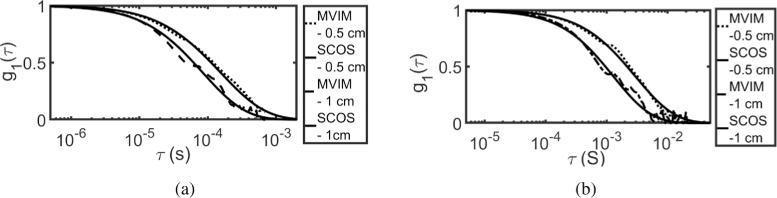

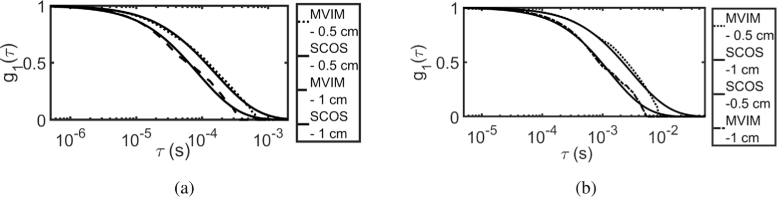

Using MVIM, the normalized field auto-correlation function was recovered for both intralipid and glycerol phantoms for the above mentioned SD separations and the results are shown in Fig. 12 and Fig. 13. It is compared with computed for fitted by SCOS [23]. Figure 12 shows the recovered by MVIM using prior information , where (a) shows the results of intralipid phantom and (b) shows the results of glycerol phantom. Similar plot is shown in Fig. 13 by using iterative scheme, wherein solution of CDE [6,46] was used as model for updating the prior information.

Fig. 12.

Recovered using MVIM, using prior () and compared against fitted using SCOS with SD - 0.5 and 1 cm for (a) intralipid phantom (b) glycerol phantom.

Fig. 13.

Recovered using MVIM, using iterative scheme and compared against fitted using SCOS with SD - 0.5 and 1 cm for (a) intralipid phantom (b) glycerol phantom.

The recovered was fitted for against CDE model [6,46]. For Intralipid phantom, with prior information (), the fitted values are and respectively for SD of 0.5 and 1 cm. Similarly by using iterative scheme, the fitted values are and . The above values are in reasonable agreement with SCOS [23] fitted of . Similarly for glycerol phantom, the recovered , using prior information (), the fitted values are and respectively and by using iterative scheme, the fitted values are and respectively for SD of 0.5 and 1 cm. These values also are in agreement with SCOS fitted value of .

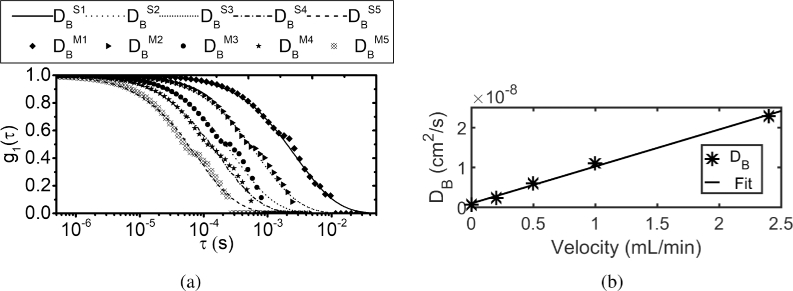

Subsequently, using flow phantoms controlled by syringe pump, different flows were made and speckle contrast at different exposures were measured at an SD separation of 0.75 cm. By using MVIM, normalized field auto-correlation () function was recovered and is plotted in Fig. 14(a) for different flows. Here iterative MVIM algorithm was employed to recover . The was fitted for values against solution of CDE and plotted against the flow velocity is shown in Fig. 14(b) where it can be seen that the value increases linearly with velocity of the syringe pump. The fitted for MVIM is compared against the fitted for SCOS and is tabulated in Table 4.

Fig. 14.

(a) Recovered using the proposed method and based on SCOS fit for different flows is plotted. The shift of the curve from the right to left indicates the increase in flow. (b) MVIM fitted values plotted against the velocity of the syringe pump. It can be seen that as the velocity of the flow increases, the value also increases linearly.

Table 4. Comparison between MVIM fitted and SCOS fitted for different flow rates. The superscripts ’M’ and ’S’ refers to the MVIM and SCOS based fit for values respectively, which corresponds to the curves shown in Fig. 14(a).

| MVIM Fitted | SCOS fitted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

4.2.3. in vivo experiment

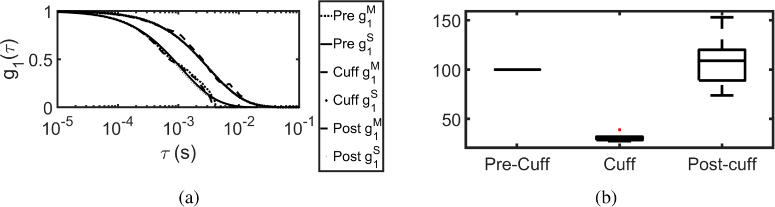

We validate the proposed system and method in vivo, by performing a human hand blood cuff experiment, for 5 healthy volunteers. The experimental protocol involves 90 s measurement of multi-exposure speckle contrast for each pre-cuff, cuff and post cuff phases. The multi-exposure data was acquired at 15 exposures in the range of 0.5 ms to 20 ms spaced in logarithmic scale, with 200 frames in each exposure to calculate the speckle contrast. The results of MVIM recovered is plotted, along with results of obtained by fitted for SCOS at a SD separation of 1 cm, in Fig. 15(a). The relative blood flow rBF [33] is plotted for each phase in Fig. 15(b) . It can be seen that on an average for 5 volunteers, there is almost decrease in blood flow between pre-cuff and cuff phases and the flow is recovered back during post cuff phase, which is comparable with results reported in Ref. [23,33].

Fig. 15.

(a) The , measured by the proposed MVIM algorithm using the camera based system, is compared with SCOS fitted for human hand blood cuff experiment during pre-cuff, cuff and post cuff phases. The shift in curve towards right indicating the decrease in blood flow. (b) Relative blood flow (rBF) for the five volunteers for pre-cuff, cuff and post cuff phases. It can be seen that there is almost decrease in blood flow between pre-cuff and cuff phases. Here the superscript M and S in the legend indicates that it is MVIM recovered and SCOS fitted respectively.

In nut-shell, we have validated the proposed MVIM algorithm to measure field auto-correlation function using a camera based system, for tissue mimicking phantoms and for in vivo experiments.

5. Discussion and conclusion

An algorithm and formalism for the recovery of the DCS data-type from speckle contrast measurements using a system based on an inexpensive CCD/CMOS camera to measure blood flow is presented. A direct auto-correlation on the measured intensity speckles requires a camera with high frame rate (typically few MHz) along with a good sensitivity (Quantum Efficiency (QE) > and dynamic range > ), high SNR (readout noise < ) and a wide range of exposure control (typically to few seconds). Although high frame rate cameras are commercially available (with typically around FPS), there is always a trade-off between frame rate and SNR. However, in Ref. [52], the intensity correlation was measured for laser speckle contrast imaging using camera of high frame rate (20000 Hz). The measured field auto correlation was used to understand the appropriate model for the blood flow. This is one of the potential applications where a direct recovery of the autocorrelation function is required instead of a least square fitted blood flow index (BFI). In the above method, the authors have employed a high frame rate of 20000 fps due to the fact that the de-correlation time () is in the order of milliseconds. By recovering DCS data-type using MVIM method and an inexpensive low frame rate camera, we circumvent the need of a high frame rate camera. The MVIM method utilizes the fact that speckle contrast is a definite integral of normalized field auto-correlation function over correlation delay time integrated upto exposure time of the camera. We identified this integral equation as Volterra integral equation of first kind and hence we adopted a multi-step method to solve it. The proposed multi-step volterra integral method (MVIM) was successfully integrated with the camera based laser imaging system to recover the field auto-correlation from the multi-exposure speckle contrast data. The camera employed was a CCD camera with a low frame rate (<120 frames), but with reasonably good sensitivity (QE of , dynamic range ) and exposure control (4μs to 10 s).

This method is equally applicable for measuring superficial tissue blood flow (LSCI) as well as deep blood flow (DCS), as the relation connecting speckle contrast and field auto-correlation is common for both the cases. Although the single exposure speckle contrast integrates the field auto-correlation over correlation delay time (upto the exposure time of camera), the multi-exposure speckle contrast retains the details of auto-correlation decay of the sample. This fact is utilized by MVIM for recovery of field auto-correlation function . Methods such as MESI [13] for single scattering case and SCOS [22,23,33] for multiple scattering case utilize multi-exposure speckle contrast data. These methods have quantified blood flow either through or by a direct least square fit on the multi-exposure speckle contrast data without attempting to recover the field auto-correlation. Infact, by using the proposed MVIM based system, we have proved that a direct recovery of for every values is possible instead of quantifying flow by a least square fit on multi-exposure speckle contrast data.

The volttera integral equation connecting and was discretized numerically and posed as matrix equation. Although the volterra integral equation of first kind is not an ill-posed problem [53], due to the presence of noise in the measured speckle contrast and practical difficulties of measuring for dense and wide range of exposure times, Tikhonov regularization based non-linear least square minimization was used for solving the above equation. The optimal measurement and minimization parameters such as optimal exposure time and sampling interval of correlation delay time has been presented along with an iterative scheme for better recovery of field auto-correlation function. The simulation and experimental results, that includes recovery of in flow phantoms and in vivo experiments, validates the presented MVIM based system to measure field auto-correlation function.

The results presented in this paper shows that our method is infact comparable to existing speckle contrast methods. There are two aspects of the presented work that we would like to mention, which are “inexpensive” nature of the measurement system compared to conventional DCS and preliminary study on the “information content” of the multi exposure speckle contrast data. The former is evident from the fact that by using the speckle contrast as the measurand, we do not need a fast and sensitive detector array, and, yet, still recover the full DCS data-type. For addressing the second aspect of the proposed method namely ’information content’ of speckle contrast data, we have proved via MVIM that a multi exposure data has enough information to retrieve the DCS data-type for a relevant range of delay times (at each source detector SD separation).

Though we have shown the MVIM method for recovering the normalized field auto-correlation function , we can also recover the normalized intensity auto-correlation, , by posing the integral equation as . Note that this equation is independent of and any uncertainties in measuring will not affect the recovery of .

We have experimentally validated the working of the proposed method using SD separations of to which are shorter when compared to the usually used SD separations in DCS for measurements on the adults (i.e., to ). This is due to the current limitations of the camera. However, MVIM method is applicable for multi exposure speckle contrast data at every SD separation. We may use a better camera with a higher sensitivity (in terms of quantum efficiency and full well capacity) to achieve a higher SD separations, still staying on the in-expensive side. We note that these SD separations are relevant in terms of animal imaging studies [10,11,25]. We have demonstrated the working of two layer models via simulations, however, experimental validation was not performed. This is primarily due to the low dynamic range of the camera used for the experiment. Since, two different correlation decay demands the data acquisition for a larger range of exposure time, the dynamic range acts as a constraining factor. We also note that the proposed non-iterative MVIM method does not require any field auto-correlation model (such as CDE or ) for recovering field auto-correlation function . We have adopted the above mentioned models in this paper for validating the results against MESI and SCOS.

In order to acquire the multi-exposure speckle contrast data, we need to frequently vary the exposure time. This can be achieved by either (a) keeping the camera exposure time constant but limiting the laser exposure using an external modulator [13] or (b) by changing the camera exposure time. Here, we have used the second approach which is not tedious since most modern cameras allow this to be controlled in an automated manner by software. One of the limitations of the system is, that the low frame rate of the camera constrains performing certain experiments, where in the flow parameters to be measured changes rapidly with time. For instance, we were not able to retrieve the reactive hyperaemia, during blood cuff experiment as we need to measure multi-exposure speckle contrast data within a short duration of time. The current implementation of calculating speckle contrast is slow as we calculate the speckle contrast over time. Alternatively, it can be calculated over space so that only one frame is needed per exposure time. With the current frame-rate, this would allow data acquisition at a much faster rate (approximately 2 seconds). One of the limitations of the MVIM method is that, even though we use iterative scheme, we could not completely eliminate the ripples present in the recovered field auto-correlation at the larger correlation delay time ( values). This can be improved by averaging more frames (as the SNR increases by square root of number of frames) and by using a high sensitive camera. The above-mentioned limitations of both system and the method have to be improved in order to adapt the system for clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

TD and HV gratefully acknowledge the fruitful discussions with Arjun Yodh.

Funding

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay10.13039/501100005808 (Seed-grant); Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology10.13039/501100001409 (Early career research award), Government of India; Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology10.13039/501100001407, Government of India (Ramalingaswamy Fellowship-2016); Fundación CELLEX10.13039/100008050 Barcelona; Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad10.13039/501100003329/FEDER (PHOTODEMENTIA, DPI2015-64358-C21-R); Instituto de Salud Carlos III10.13039/501100004587/FEDER (FISPI09/0557, MEDPHOTAGE, DTS16/00087); "Severo Ochoa" Programme for Center for Excellence in R & D (SEV-2015-0522); the Obra Social “la Caixa” Foundation10.13039/100010434 (LlumMedBcn); Centres de Recerca de Catalunya; Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca10.13039/501100003030 Generalitat (2017SGR-1380); LASERLAB-EUROPE IV (EU-H2020 654148); Fundació la Marató de TV310.13039/100008666 (201709.31).

Disclosures

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Briers J. D., Webster S., “Laser speckle contrast analysis (lasca): a nonscanning, full-field technique for monitoring capillary blood flow,” J. Biomed. Opt. 1(2), 174–180 (1996). 10.1117/12.231359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn A. K., Bolay H., Moskowitz M. A., Boas D. A., “Dynamic imaging of cerebral blood flow using laser speckle,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21(3), 195–201 (2001). 10.1097/00004647-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boas D. A., Dunn A. K., “Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics,” J. Biomed. Opt. 15(1), 011109 (2010). 10.1117/1.3285504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riva C., Ross B., Benedek G. B., “Laser doppler measurements of blood flow in capillary tubes and retinal arteries,” Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 11, 936–944 (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajan V., Varghese B., van Leeuwen T. G., Steenbergen W., “Review of methodological developments in laser doppler flowmetry,” Lasers Med. Sci. 24(2), 269–283 (2009). 10.1007/s10103-007-0524-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boas D. A., Campbell L., Yodh A. G., “Scattering and imaging with diffusing temporal field correlations,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 75(9), 1855–1858 (1995). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boas D. A., Yodh A. G., “Spatially varying dynamical properties of turbid media probed with diffusing temporal light correlation,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 14(1), 192–215 (1997). 10.1364/JOSAA.14.000192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durduran T., Yodh A. G., “Diffuse correlation spectroscopy for non-invasive, micro-vascular cerebral blood flow measurement,” NeuroImage 85, 51–63 (2014). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou C., Yu G., Furuya D., Greenberg J. H., Yodh A. G., Durduran T., “Diffuse optical correlation tomography of cerebral blood flow during cortical spreading depression in rat brain,” Opt. Express 14(3), 1125–1144 (2006). 10.1364/OE.14.001125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han S., Proctor A. R., Vella J. B., Benoit D. S., Choe R., “Non-invasive diffuse correlation tomography reveals spatial and temporal blood flow differences in murine bone grafting approaches,” Biomed. Opt. Express 7(9), 3262–3279 (2016). 10.1364/BOE.7.003262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culver J. P., Durduran T., Furuya D., Cheung C., Greenberg J. H., Yodh A., “Diffuse optical tomography of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation, and metabolism in rat during focal ischemia,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23(8), 911–924 (2003). 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076703.71231.BB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fercher A., Briers J. D., “Flow visualization by means of single-exposure speckle photography,” Opt. Commun. 37(5), 326–330 (1981). 10.1016/0030-4018(81)90428-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parthasarathy A. B., Tom W. J., Gopal A., Zhang X., Dunn A. K., “Robust flow measurement with multi-exposure speckle imaging,” Opt. Express 16(3), 1975–1989 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.001975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pine D., Weitz D., Chaikin P., Herbolzheimer E., “Diffusing wave spectroscopy,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 60(12), 1134–1137 (1988). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maret G., Wolf P., “Multiple light scattering from disordered media. the effect of brownian motion of scatterers,” Z. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 65(4), 409–413 (1987). 10.1007/BF01303762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weitz D., Zhu J., Durian D., Gang H., Pine D., “Diffusing-wave spectroscopy: The technique and some applications,” Phys. Scr. T49B, 610–621 (1993). 10.1088/0031-8949/1993/T49B/040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pine D., Weitz D., Zhu J., Herbolzheimer E., “Diffusing-wave spectroscopy: dynamic light scattering in the multiple scattering limit,” J. Phys. 51(18), 2101–2127 (1990). 10.1051/jphys:0199000510180210100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boas D. A., “Diffuse photon probes of structural and dynamical properties of turbid media: theory and biomedical applications,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania; (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung C., Culver J. P., Takahashi K., Greenberg J. H., Yodh A., “In vivo cerebrovascular measurement combining diffuse near-infrared absorption and correlation spectroscopies,” Phys. Med. Biol. 46(8), 2053–2065 (2001). 10.1088/0031-9155/46/8/302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durduran T., Yu G., Burnett M. G., Detre J. A., Greenberg J. H., Wang J., Zhou C., Yodh A. G., “Diffuse optical measurement of blood flow, blood oxygenation, and metabolism in a human brain during sensorimotor cortex activation,” Opt. Lett. 29(15), 1766–1768 (2004). 10.1364/OL.29.001766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietsche G., Ninck M., Ortolf C., Li J., Jaillon F., Gisler T., “Fiber-based multispeckle detection for time-resolved diffusing-wave spectroscopy: characterization and application to blood flow detection in deep tissue,” Appl. Opt. 46(35), 8506–8514 (2007). 10.1364/AO.46.008506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bi R., Dong J., Lee K., “Deep tissue flowmetry based on diffuse speckle contrast analysis,” Opt. Lett. 38(9), 1401–1403 (2013). 10.1364/OL.38.001401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valdes C. P., Varma H. M., Kristoffersen A. K., Dragojevic T., Culver J. P., Durduran T., “Speckle contrast optical spectroscopy, a non-invasive, diffuse optical method for measuring microvascular blood flow in tissue,” Biomed. Opt. Express 5(8), 2769–2784 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.002769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma H. M., Valdes C. P., Kristoffersen A. K., Culver J. P., Durduran T., “Speckle contrast optical tomography: A new method for deep tissue three-dimensional tomography of blood flow,” Biomed. Opt. Express 5(4), 1275–1289 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.001275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dragojević T., Varma H. M., Hollmann J. L., Valdes C. P., Culver J. P., Justicia C., Durduran T., “High-density speckle contrast optical tomography (scot) for three dimensional tomographic imaging of the small animal brain,” NeuroImage 153, 283–292 (2017). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang C., Irwin D., Lin Y., Shang Y., He L., Kong W., Luo J., Yu G., “Speckle contrast diffuse correlation tomography of complex turbid medium flow,” Med. Phys. 42(7), 4000–4006 (2015). 10.1118/1.4922206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bi R., Dong J., Lee K., “Multi-channel deep tissue flowmetry based on temporal diffuse speckle contrast analysis,” Opt. Express 21(19), 22854–22861 (2013). 10.1364/OE.21.022854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dragojević T., Bronzi D., Varma H. M., Valdes C. P., Castellvi C., Villa F., Tosi A., Justicia C., Zappa F., Durduran T., “High-speed multi-exposure laser speckle contrast imaging with a single-photon counting camera,” Biomed. Opt. Express 6(8), 2865–2876 (2015). 10.1364/BOE.6.002865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang C., Seong M., Morgan J. P., Mazdeyasna S., Kim J. G., Hastings J. T., Yu G., “Low-cost compact diffuse speckle contrast flowmeter using small laser diode and bare charge-coupled-device,” J. Biomed. Opt. 21(8), 080501 (2016). 10.1117/1.JBO.21.8.080501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C., Irwin D., Zhao M., Shang Y., Agochukwu N., Wong L., Yu G., “Noncontact 3-D speckle contrast diffuse correlation tomography of tissue blood flow distribution,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36(10), 2068–2076 (2017). 10.1109/TMI.2017.2708661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J., Zhang H., Lu J., Ni X., Shen Z., “Quantitative model of diffuse speckle contrast analysis for flow measurement,” J. Biomed. Opt. 22(7), 076016 (2017). 10.1117/1.JBO.22.7.076016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J., Zhang H., Lu J., Ni X., Shen Z., “Simultaneously extracting multiple parameters via multi-distance and multi-exposure diffuse speckle contrast analysis,” Biomed. Opt. Express 8(10), 4537–4550 (2017). 10.1364/BOE.8.004537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dragojević T., Hollmann J. L., Tamborini D., Portaluppi D., Buttafava M., Culver J. P., Villa F., Durduran T., “Compact, multi-exposure speckle contrast optical spectroscopy (scos) device for measuring deep tissue blood flow,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(1), 322–334 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandyopadhyay R., Gittings A., Suh S., Dixon P., Durian D. J., “Speckle-visibility spectroscopy: A tool to study time-varying dynamics,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76(9), 093110 (2005). 10.1063/1.2037987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong A. P., Wiltzius P., “Dynamic light scattering with a ccd camera,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 64(9), 2547–2549 (1993). 10.1063/1.1143864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou W., Kholiqov O., Chong S. P., Srinivasan V. J., “Highly parallel, interferometric diffusing wave spectroscopy for monitoring cerebral blood flow dynamics,” Optica 5(5), 518–527 (2018). 10.1364/OPTICA.5.000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrade C., Franco N. B., McKee S., “Convergence of linear multistep methods for volterra first kind equations with k (t, t) 0,” Computing 27(3), 189–204 (1981). 10.1007/BF02237977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunner H., Volterra Integral Equations: An Introduction to Theory and Applications, vol. 30 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holyhead P., McKee S., Taylor P., “Multistep methods for solving linear volterra integral equations of the first kind,” SIAM J. on Numer. Analysis 12(5), 698–711 (1975). 10.1137/0712052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan S., Sensitivity, noise and quantitative model of laser speckle contrast imaging (Tufts University, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen P. C., OLeary D. P., “The use of the l-curve in the regularization of discrete ill-posed problems,” SIAM J. on Sci. Comput. 14(6), 1487–1503 (1993). 10.1137/0914086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan S., Devor A., Boas D. A., Dunn A. K., “Determination of optimal exposure time for imaging of blood flow changes with laser speckle contrast imaging,” Appl. Opt. 44(10), 1823–1830 (2005). 10.1364/AO.44.001823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choe R., “Diffuse optical tomography and spectroscopy of breast cancer and fetal brain,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania; (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michels R., Foschum F., Kienle A., “Optical properties of fat emulsions,” Opt. Express 16(8), 5907–5925 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.005907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L. V., Wu H.-i., Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging (John Wiley & Sons, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durduran T., Choe R., Baker W., Yodh A. G., “Diffuse optics for tissue monitoring and tomography,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 73(7), 076701 (2010). 10.1088/0034-4885/73/7/076701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker W. B., Parthasarathy A. B., Busch D. R., Mesquita R. C., Greenberg J. H., Yodh A., “Modified beer-lambert law for blood flow,” Biomed. Opt. Express 5(11), 4053–4075 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.004053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker W. B., “Optical cerebral blood flow monitoring of mice to men,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shang Y., Li T., Chen L., Lin Y., Toborek M., Yu G., “Extraction of diffuse correlation spectroscopy flow index by integration of n th-order linear model with monte carlo simulation,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 104(19), 193703 (2014). 10.1063/1.4876216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X., Gui Z., Qiao Z., Liu Y., Shang Y., “Nth-order linear algorithm for diffuse correlation tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 9(5), 2365–2382 (2018). 10.1364/BOE.9.002365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varma H. M., Nandakumaran A., Vasu R., “Study of turbid media with light: Recovery of mechanical and optical properties from boundary measurement of intensity autocorrelation of light,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 26(6), 1472–1483 (2009). 10.1364/JOSAA.26.001472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Postnov D. D., Erdener S. E., Tang J., Boas D. A., “Dynamic laser speckle imaging: beyond the contrast (conference presentation),” in Dynamics and Fluctuations in Biomedical Photonics XVI, vol. 10877 (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2019), p. 108770A. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wazwaz A.-M., “The regularization method for fredholm integral equations of the first kind,” Comput. & Math. with Appl. 61(10), 2981–2986 (2011). 10.1016/j.camwa.2011.03.083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]