Abstract

Few studies have examined in detail how specific behaviors of friends put adolescents at risk of substance use. We investigated adolescents’ perceptions of the problematic behaviors of their close friends as predictors of their own subsequent tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use.

We examined how well the substance use of 248 young urban adolescents was predicted by perceptions of their three closest friends’ problematic behaviors: 1) using substances, 2) offering substances, and 3) engaging with friends in risky behavior (substance use, illegal behavior, violent behavior, or high-risk sexual behavior. Three longitudinal multivariate repeated measures models were tested to predict tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use over 24 months based on perceptions of problematic peer behaviors assessed at baseline. Perceived closeness was tested as a moderator of the effects of perceptions of problematic peer behavior.

Perceptions of peer substance use were significantly associated with tobacco use, and closeness moderated the influence of peer substance use and offers to use substances on tobacco use. Perceptions of problematic peer behaviors were not significantly associated with alcohol use and closeness was not significant as a moderator. Perceptions of peer substance use was significantly associated with cannabis use, and closeness moderated the influence of perceptions of peer risk behaviors, peer substance use, and offers to use substances on cannabis use.

Results implicate the importance of understanding problematic peer behavior within the context of close, adolescent friendships. Interventions that sensitively help adolescents modify their close friendships may be successful in reducing or preventing substance use.

Keywords: Young Adolescents, Substance Use, Close Friend Behavior, Peer Network Health

Alcohol and cannabis are the most widely used substances among U.S. adolescents while cigarette smoking, which typically is initiated during adolescence, is the leading cause of preventable disease and mortality (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2017). Approximately half (46%) of U.S. 12th graders and one in eleven (9%) 8th graders in 2016 reported having been drunk at least once in their life, 6% of 12th graders are daily cannabis smokers, and 11% of 12th graders are current cigarette smokers (Johnston et al., 2017). Prevalence rates of high school student tobacco and alcohol use vary by racial/ethic groups. On average, White adolescents use more alcohol and tobacco than Hispanic adolescents, and African American adolescents use the least (Johnston et al., 2017). Differences in prevalence rates of cannabis use among racial/ethnic groups have essentially disappeared, with Hispanic and African American high school students using cannabis at the same rate as Whites (Johnston et al., 2017). However, among those who develop cannabis use disorder, African Americans have the highest rates of transition from first use to cannabis disorder compared to other subgroups (Lopez-Quintero, Pérez de los Cobos, Hasin, et al., 2011).

Extensive research has shown that peer context predicts tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (Bauman & Ennett, 1996; Knecht, Burk, Weesie, & Steglich, 2011; Light, Greenan, Rusby, Nies, & Snijders, 2013; Valente, Unger, & Johnson, 2005). The peer group provides a critical social influence for adolescents in the initiation of substance use (Huang, Unger, Soto, Fujimoto, Pentz, Jordan-Marsh, & Valente, 2014; Sieving, Peery, & Williams, 2000). Even when controlling for genetic and shared environmental differences, peer network substance use predicts future individual substance use, with stronger effects occurring within high-intensity/best friendships (Cruz, Emery, & Turkheimer, 2012). Perceived closeness to friends, as a measure of friendship quality, has been associated with substance use. Research suggests that individuals within friendships experience closer relationships when they share substance use in common (Krohn & Thomberry, 1993). This indeed appears to be true for two common forms of substance use: binge drinking and cannabis use (Boman, Stogner, & Lee Miller, 2013) where closeness was associated with these behaviors. Deutsch and colleagues (2015) found that cannabis use initiation was dependent upon perceived friend substance use for adolescents who experienced more closeness among their friends. These peer network studies point to the importance of investigating how different aspects of friends’ behaviors may predict the use of different substances (i.e., tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis).

The field of prevention science has struggled with methods to understand the role of peers on adolescent behaviors. For example, adolescents who themselves report substance use are more likely to perceive higher prevalence of substance use among other adolescents, and those who do not use substances perceive less (Bauman & Ennett, 1996; Henry, Kobus, & Schoeny, 2011). This result is known as the false consensus effect (Ross, Greene, & House, 1977), believing that one’s peers engage in behaviors similar to their own. Thus, an adolescent’s perceptions of his or her friends’ substance use may greatly influence his own substance use, even if those friends’ do not use substances or use infrequently. In fact, recent research has demonstrated equivalent influence effects of perceived peer substance use and actual peer substance use (Deutsch, Chernyavskiy, Steinley, & Slutske, 2015). For this reason, the present study measures adolescents’ perceptions of their friends’ behaviors.

Given the comorbidity of antisocial behavior and substance use during adolescence, we control for baseline youth-reported antisocial behavior. Using a longitudinal cross-lagged model approach, McAdams et al. (2014) found that antisocial behavior predicted substance use during early adolescence. Moreover, friends’ antisocial behaviors predicted both substance use and antisocial behaviors (McAdams et al., 2014). The confluence hypothesis proposes a dynamic process between adolescent antisocial behavior and affiliation with peers who exhibit antisocial behavior (Light & Dishion, 2007); both selection and influence effects may occur. In an African-American sample of youth, adolescents who had friends with antisocial behaviors were more likely to onset to antisocial behaviors earlier and to persist with antisocial behaviors in later adolescence (Evans, Simons & Simons, 2014). Controlling for baseline antisocial behavior will also contribute to a better understanding of how friends’ behaviors and friendship closeness are associated with adolescent substance use.

Little research has examined specific close peer behaviors of young urban adolescents such as perceptions of specific high-risk behaviors of close friends, feelings of closeness, and subsequent substance use. Therefore, we examined adolescents’ perceptions of problematic behaviors of close friends and the accompanying level of closeness to test the association and interactive effects on subsequent tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use. We hypothesized that reporting substance use by close friends, receiving offers from close friends to use substances, and being involved with friends who partake in other high-risk behaviors would be associated with increased adolescent substance use, while controlling for age, race, gender, family history of substance use, and self-reported antisocial behavior. We further hypothesized that closeness would moderate the association between perceptions of problematic behaviors of peers and substance use, such that increased levels of closeness would be associated with increased tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use.

Methods

Participants

This study examined data from the Social-Spatial Adolescent Study, a two-year longitudinal investigation of the interacting effects of peer networks, urban environment, and substance use. Participants were recruited between November 2012 and February 2014. The majority of participants (72%) were recruited from an urban adolescent medicine primary care clinic at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, in Richmond Virginia; the remainder were recruited from a city health district satellite clinic, located within a subsidized housing development. Over 400 adolescents’ patients and parents were either approached at the outpatient hospital clinic or referred from the satellite clinic; of these, 57% enrolled in the study (N=248). Enrollment and data collection procedures were the same across sites. Chi-square tests revealed no significant differences in age, sex, or race of participants between the recruitment sites. The sample recruited is representative of the patients typically serviced at each of these clinics (see results).

Eligible adolescents were age 13 or 14 at enrollment and a registered patient of either clinic site. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents and adolescent participants prior to conducting any research activities. The first author’s university and the Richmond City Health Department’s institutional review boards approved the research protocol, and the study received a federal Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health. At enrollment, participants completed an initial survey in a private room separate from parents and any clinic staff. Participants received monetary incentives for their time and effort in completing follow-up surveys ($20 at 12-month and $60 at 24-month). Most participants completed the follow-up surveys at 12 months (82%) and 24 months (84%). Subsequent independent t-tests revealed no significant differences between completers and non-completers on key variables at baseline (e.g., cannabis involvement, peer network health, p >0.05).

Measures

Demographics.

Participants reported age, gender and race on the baseline survey. Gender was coded as 0 = female, 1 = male. Because the sample consisted of 88% African American, race was coded as 0 = not black, 1= black.

Close Friend Problematic Behaviors.

Data on perceptions of problematic behaviors by close friends were gathered using the Adolescent Social Network Assessment (ASNA; Mason, Cheung, & Walker, 2004). Three types of friends’ problematic behaviors were used in this study: 1) using substances, 2) offering substances, and 3), engaging with peer in risky behavior (substance use, illegal behavior, violent behavior, or high-risk sexual behavior [sex with no condom, sex with person with HIV/AIDS or unknown HIV status]). The ASNA captures information on each participant’s close friends, which constitute their personal or egocentric peer network. ASNA has favorable internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .84) and correlates significantly in the expected direction with self-reported measures of substance use (any alcohol, cannabis or other substance, (r = −.64), alcohol use (r = −.66) and cannabis use (r = −.54; Mason, Mennis, & Schmidt, 2011). Because the current study focused on the influence of close peer networks, the number of nominated close friends was set to three, as this aligns with the national average of nominated adolescent close friends (2.54; Ali, Amialchuk, & Dwyer, 2011). These selected friends were the peers that participants spent the most time with. Adolescents were asked to think of up to three friends and to provide their perceptions of each of their peer's substance use, level of influence on their behavior, and types of activities typical of the relationship. For this study, three items from the ASNA were used: 1) Does this friend use any substances such as alcohol, beer, marijuana or other drugs (other drugs were defined as cocaine, crack, heroin, LSD, molly, X, ecstasy, drugs given by doctors [pain pills, Oxycotin, or Adderall], or over the counter drugs like cough syrup); 2) Has this friend ever offered, suggested, or asked you to use substances?; and 3) Were you involved with this friend when you or he/she were using substances, doing something illegal, attacking others or being attacked, or having unprotected sex (sex with no condom, sex with person with HIV/AIDS or unknown HIV status)? All items were coded as 0= no, 1= yes.

Friendship Quality.

Friendship quality was measured using the closeness item from the ASNA. Adolescents reported their perceived level of closeness for each of the three friends nominated using the item, “How close do you feel to Friend #1?,” which was coded as 1 = not close, 2 = somewhat close, and 3 = very close. The item was repeated for each friend and a total score was used, ranging from 3 to 9, with higher scores indicating more perceived closeness.

Substance Use.

The Adolescent Alcohol and Drug Involvement Scale (AADIS, Moberg & Hahn, 1991) was used to measure substance use. The AADIS has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) and is highly correlated with self-reported measures of substance use (r = 0.72), clinical assessments (r = 0.75), and subjects’ perceptions of the severity of their own drug use problem (r = 0.79). For this study, the substance use frequency item was used for three substances tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis: Have often do you typically use ____?, which was coded as 0 = never used, 1= tried but quit, 2 = several times a year, 3 = several times a month, 4 = weekends only, 5 = several times a week, 6 = daily, and 7 = several times a day.

Family History and Attitudes Towards Substance Use.

Family substance use history and family attitudes toward substance use were assessed using the 7-item scale from the Communities that Care survey (Arthur, Hawkins, Pollard, Catalano, & Baglioni, 2002). Prior research has documented favorable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78). One item assesses substance disorder within the family; three items ask about sibling use of alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco; and three items ask about the adolescent’s perceptions of the parents’ attitudes about the adolescent’s use of marijuana, alcohol, and tobacco. This was coded as 0 = no risk, 1= positive family risk.

Antisocial Behavior.

Adolescent antisocial behavior was assessed via self-report on 10 questions from the Oregon Healthy Teens (OHT) survey (Smolkowski, Biglan, Dent, & Seeley, 2006). Adolescents reported on the number of times they engaged in antisocial behaviors, such as selling drugs, stealing, using a weapon, and vandalism on a 7-point scale (ranging from 0-40 times). The antisocial score (a total across behavior items) has a high level of variance (Smolkowski et al., 2006) and was associated with substance use, risky sexual behavior, and depression during adolescence (Boles, Biglan & Smolkowski, 2006).

Analytic Plan

The analysis began with descriptive statistics on all variables, producing means and standard deviations. Next, a Pearson correlation test examined the association of all variables to confirm all the hypothesized associated directions within our predictive models. We handled missing data using multiple imputation procedures (i.e., expectation maximization algorithm) in SPSS V. 24. Missingness for self-reported data ranged from 0 to 15%. A Little’s MCAR test (Missing Completely At Random) was subsequently conducted (χ2=3.140, DF=6, p>.05), indicating no systematic missingness. To test the hypothesis that adolescents who reported close friends’ substance use, received offers to use substances, and were involved in high-risk behaviors would be associated with tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use, three longitudinal multivariate repeated measures models were tested to predict substance use over 24 months based on perceived peer behaviors assessed at baseline. Closeness (friendship quality) was tested as a moderator of perceived peer behavior. First, tobacco use measured at baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months served as the dependent variable and three problematic peer behaviors served as the independent variables with closeness tested as a moderator. We then repeated this model for alcohol and cannabis as dependent variables. All models controlled age, race, gender, family substance use, and antisocial behavior. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.

Results

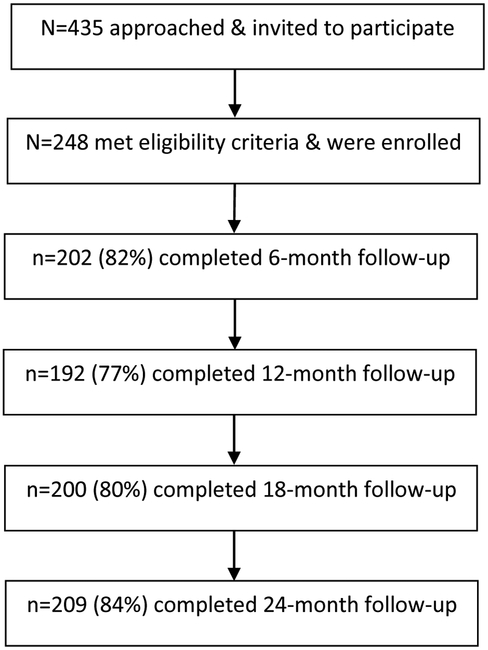

Figure 1 summarizes study participant enrollment and participation with sample sizes per study time-point. Table 1 provides descriptive and correlation statistics for all variables. All correlations, regardless of significance, were in the expected direction. Our sample was 57% female and 88% African American, with an average initial age of 13. The clinic population from where the sample was drawn was 66% female and 76% African American. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for each substance use outcome variable by assessment time-point. As can be seen, on average, substance use increases as expected with age, showing cannabis as the most used substance at 24-months, followed by tobacco, and then alcohol.

Figure 1.

Enrollment and participation across all waves

Table 1.

Correlations, Means (SD), and Percentages for Study Variables at Baseline

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | X̄ (sd), % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 13.4 (0.49) | |||||||||||

| 2. Black | −.067 | 88% | ||||||||||

| 3. Female | .046 | −.040 | 57% | |||||||||

| 4. Family History of Substance Use | .016 | .046 | −.015 | 0.4 (0.49) | ||||||||

| 5. Antisocial Behavior | .018 | −.015 | .118 | .058 | 2.7 (7.21) | |||||||

| 6. Peer Risk Behavior | .054 | .022 | .011 | .091 | .135* | 0.0 (0.27) | ||||||

| 7. Peer Substance User | .171** | .011 | .040 | .164** | .123 | .289** | 0.2 (0.40) | |||||

| 8. Offers to Use Substances | .113 | .021 | .069 | .056 | .128* | .375** | .487** | 0.1 (0.35) | ||||

| 9. Closeness | −.089 | −.083 | −.137* | −.021 | .036 | .035 | .021 | .082 | 7.2 (1.61) | |||

| 10. Tobacco | −.037 | .064 | .094 | .112 | .287** | .250** | .302** | .326** | .055 | 0.27 (0.83) | ||

| 11. Alcohol | .099 | .036 | −.061 | .215** | .170** | .268** | .341** | .284** | .061 | .454** | 0.17 (0.49) | |

| 12. Cannabis | .027 | .045 | .077 | .067 | .210** | .350** | .383** | .383** | .038 | .731** | .243** | 0.23 (0.84) |

p <0.01

p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Means, (Standard Deviations) for Outcome Variables by Assessment Time-point

| Substance | Baseline | 6-month | 12-month | 18-month | 24-month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | .27 (.83) | .38 (1.0) | .59 (1.3) | .56 (1.2) | .66 (1.4) |

| Alcohol | .18 (.49) | .30 (.70) | .35 (.68) | .38 (.79) | .38 (.75) |

| Cannabis | .23 (.84) | .50 (1.3) | .50 (1.1) | .53 (1.1) | .73 (1.4) |

See Measures section for AADIS interpretation

Table 3 provides the results of the multivariate repeated measures analyses with tobacco use as the outcome variable. Having at least one substance user in an adolescent’s close friend network was significantly associated with tobacco use (p = 0.007; eta2 = 0.07) as was the direct effect of increased levels of closeness (p = 0.004; eta2 = 0.06), producing a medium effect size. Closeness significantly moderated effects of peer substance use (p = 0.039; eta2 = 0.04) and offers to use substances (p = 0.025; eta2 = 0.04) on tobacco use, producing small effect sizes. Thus, feeling close to friends who use and offer substances at baseline predicted tobacco use across the two-year study period.

Table 3:

Results of Multivariate Repeated Measures Model Predicting Tobacco Use by Peer Behavior

| Variables | Pillai’s Trace | F | P | Eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.021 | 1.075 | 0.370 | 0.02 |

| Time × Age | 0.018 | 0.933 | 0.446 | 0.02 |

| Time × Race | 0.008 | 0.396 | 0.811 | 0.01 |

| Time × Gender | 0.013 | 0.655 | 0.624 | 0.01 |

| Time × Family History of Substance Use | 0.043 | 2.240 | 0.066 | 0.04 |

| Time × Antisocial Behavior | 0.032 | 1.662 | 0.160 | 0.03 |

| Time × Peer Risk Behavior | 0.028 | 1.447 | 0.220 | 0.03 |

| Time × Peer Substance User | 0.067 | 3.599 | 0.007 | 0.07 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances | 0.030 | 1.551 | 0.189 | 0.03 |

| Time × Closeness | 0.242 | 1.869 | 0.004 | 0.06 |

| Time × Risk Behavior × Closeness | 0.110 | 1.433 | 0.119 | 0.03 |

| Time × Peer Substance User × Closeness | 0.155 | 1.636 | 0.039 | 0.04 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances × Closeness | 0.138 | 1.815 | 0.025 | 0.04 |

Note: Eta-Squared effect sizes are interpreted as .03=small, .06=medium, .14=large (Cohen, 1988).

Table 4 provides results for the analyses with alcohol use as the outcome variable. Being male (p = 0.005; eta2 = 0.07) and having increased antisocial behavior (p = 0.020; eta2 = 0.06) was associated with alcohol use, producing medium effect sizes. Problematic peer behaviors or closeness were not significant in this model.

Table 4:

Results of Multivariate Repeated Measures Model Predicting Alcohol Use by Peer Behavior

| Variables | Pillai’s Trace | F | P | Eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.010 | 0.504 | 0.732 | 0.01 |

| Time × Age | 0.010 | 0.496 | 0.739 | 0.01 |

| Time × Race | 0.029 | 1.481 | 0.209 | 0.03 |

| Time × Gender | 0.071 | 3.834 | 0.005 | 0.07 |

| Time × Family History of Substance Use | 0.013 | 0.684 | 0.604 | 0.01 |

| Time × Antisocial Behavior | 0.057 | 3.003 | 0.020 | 0.06 |

| Time × Peer Risk Behavior | 0.011 | 0.546 | 0.702 | 0.01 |

| Time × Peer Substance User | 0.039 | 2.040 | 0.090 | 0.04 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances | 0.031 | 1.615 | 0.172 | 0.03 |

| Time × Closeness | 0.143 | 1.074 | 0.363 | 0.04 |

| Time × Risk Behavior × Closeness | 0.058 | 0.752 | 0.741 | 0.02 |

| Time × Peer Substance User × Closeness | 0.114 | 1.191 | 0.254 | 0.03 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances × Closeness | 0.041 | 0.521 | 0.937 | 0.01 |

Note: Eta-Squared effect sizes are interpreted as .03=small, .06=medium, .14=large (Cohen, 1988).

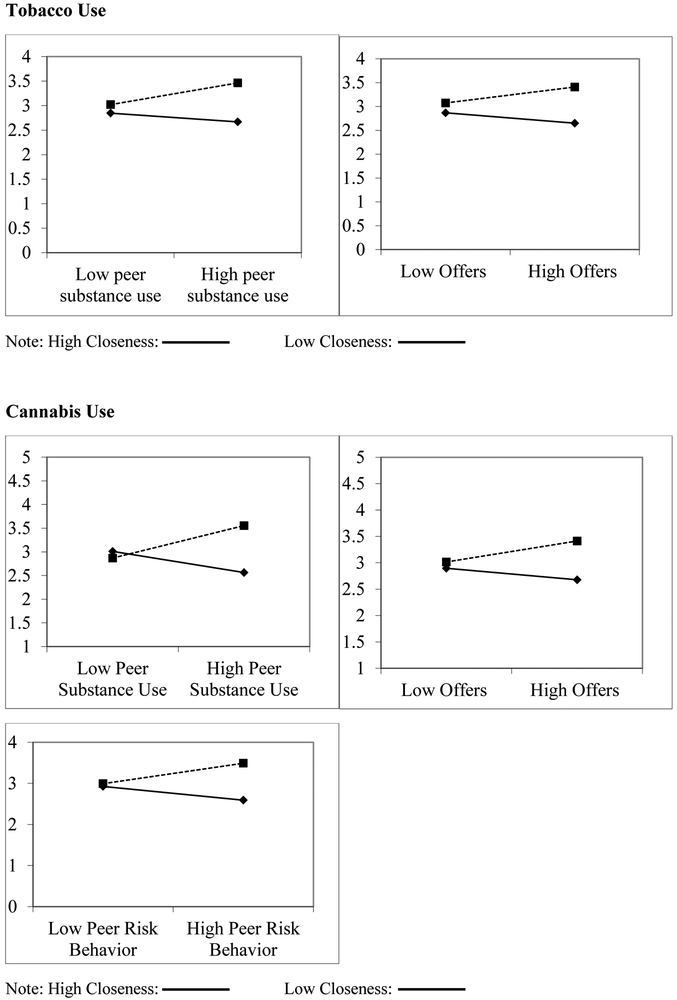

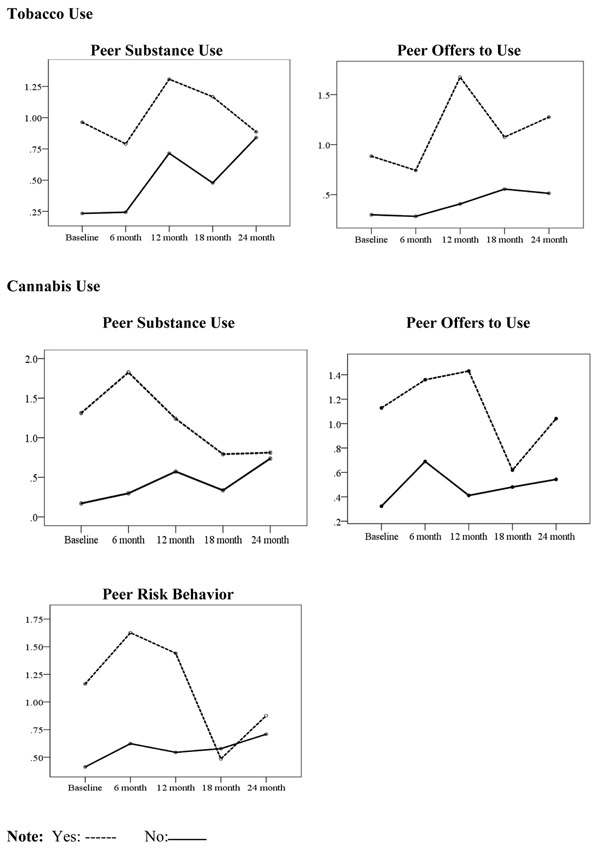

Table 5 provides the results for the analyses with cannabis use as the outcome variable. Having a family history of substance use (p = 0.015; eta2 = 0.06), having elevated levels of antisocial behavior (p = 0.002; eta2 = 0.08), and feeling close to one’s friends (p = 0.021; eta2 = 0.05) was associated with cannabis use. Effect sizes were moderate and small. Having a substance user in one’s network (p = 0.016; eta2 = 0.067) was associated with cannabis use, producing a medium effect. Closeness significantly moderated the effects of peer risk behaviors (p = 0.001; eta2 = 0.05), peer substance use (p = 0.001; eta2 = 0.07), and offers to use substances (p = 0.010; eta2 = 0.04) on cannabis use, producing small and medium effect sizes. Hence, feeling close to friends who engage in risky behaviors, use substances, and offer substances at baseline, significantly predicted cannabis use across the two-year study period. Figure 2 displays moderation graphs of the significant peer behavior by closeness for tobacco and cannabis use. Figure 3 provides graphs of the main effects of the significant moderated peer variables across study waves for tobacco and cannabis use.

Table 5.

Results of Multivariate Repeated Measures Model Predicting Cannabis Use by Peer Behavior

| Variables | Pillai’s Trace | F | P | Eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 0.020 | 1.041 | 0.387 | 0.02 |

| Time × Age | 0.021 | 1.050 | 0.382 | 0.02 |

| Time × Race | 0.010 | 0.513 | 0.726 | 0.01 |

| Time × Gender | 0.033 | 1.732 | 0.144 | 0.03 |

| Time × Family History of Substance Use | 0.059 | 3.160 | 0.015 | 0.06 |

| Time × Antisocial Behavior | 0.079 | 4.307 | 0.002 | 0.08 |

| Time × Peer Risk Behavior | 0.041 | 2.147 | 0.076 | 0.04 |

| Time × Peer Substance User | 0.059 | 3.123 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances | 0.044 | 2.307 | 0.059 | 0.04 |

| Time × Closeness | 0.213 | 1.634 | 0.021 | 0.05 |

| Time × Risk Behavior × Closeness | 0.206 | 2.755 | 0.001 | 0.05 |

| Time × Peer Substance User × Closeness | 0.283 | 3.093 | 0.001 | 0.07 |

| Time × Offers to Use Substances × Closeness | 0.154 | 2.027 | 0.010 | 0.04 |

Note: Eta-Squared effect sizes are interpreted as .03=small, .06=medium, .14=large (Cohen, 1988).

Figure 2.

Moderation graphs of significant peer behavior by closeness on tobacco and cannabis use

Figure 3.

Main effects of significant moderated peer variables across study waves by tobacco and cannabis use

Discussion

The present study contributes to the peer relations literature by providing detailed analyses of how perceptions of adolescents’ close friends’ specific behaviors are related to subsequent adolescent substance use over a 24-month period. Understanding the longitudinal effects of specific behaviors of close friends such as high-risk behaviors, substance use, and offers to use substances provides insight into the social context of adolescent substance use. Having the ability to specify behaviors of friends that are particularly risk enhancing affords the opportunity for intervention researchers to test these findings by type of substance.

The variability of the problematic behaviors by type of substance may provide insight into the interactive nature of substance use by peer behaviors. Alcohol use appears to be not affected by problematic peer behavior, which could be interpreted as supporting other research that found selection effects to be stronger regarding alcohol use (Pearson et al., 2006). If an adolescent purposely selects friends who are alcohol users, then the associated peer behaviors will likely have little effect. However, rates of alcohol use in the current study were low and might explain the model outcomes. In contrast, cannabis use appears to be more sensitive to peer behavior influence, with all three behaviors significantly interacting with closeness, supporting previous research (Pearson et al., 2006).

The degree of closeness, which represents friendship quality and trust, may provide further understanding into the mechanisms of peer behaviors and substance use. Our results demonstrate that closeness significantly moderated the influence of two of the three problematic behaviors for tobacco use and all three behaviors for cannabis use. The cannabis finding supports recent research that similarly found an interaction between cannabis use and increased levels of closeness among adolescents (Deutsch et al., 2015). Across both tobacco and cannabis use the low levels of peer closeness slopes remained essentially flat. This could be interpreted as a protective quality, such that the adolescents who do not feel close to their peers who engage in deviant behavior are less likely to use tobacco or cannabis. This could also support the theory of peer influence for these substances, however this study was not designed to explicitly test for this.

Given that alcohol is the most widely used substance among adolescents, perhaps the peer effects are less relevant in that adolescents who are drinking alcohol may do so in more open group settings, such as parties, where alcohol is readily available. In contrast, cannabis is illegal in most states, and may require more social interaction and trust to enter a close group who are using regularly. In this case, the act of being offered substances may be more significant, in that it could represent a level of trust and bonding that is different than when consuming alcohol. Because alcohol use was associated with antisocial behavior and cannabis use was not, another possibility is that the adolescents who were using alcohol were already involved with a network of antisocial, alcohol using peers by the time of the baseline assessment, and therefore closeness of friends was no longer an influential factor. Friendship closeness may be an influential factor for cannabis use at this age, as a network of cannabis using peers had yet to be established.

Regarding the peer effects with tobacco use, it may be that because tobacco use is now perceived as more risky than cannabis use (Mason, Mennis, Linker, Bares, & Zaharakis, 2014), tobacco users are more sensitive to their peer behaviors given the potentially ostracizing impact of using tobacco. The cigarette smoking peer group may form a tight and trusting bond of smokers, which may play a role in identity development through group affiliation as a smoker. More detailed research into the best methods for assessing problematic behaviors, as well as friendship quality, is needed to better understand the mechanisms of peer behavior and subsequent substance use.

The finding that having friends who offer substances significantly increased the risk of tobacco and cannabis use is an important finding from this study. These results suggest that being offered substances at age 13 has a lasting effect on future tobacco and cannabis use at age 15. It is reasonable to assume that a direct invitation to use substances carries influence, particularly if an adolescent is seeking to become established or to fit in with an aspiring peer group. Further, these young adolescents are transitioning from middle school into high school and are typically adapting to these psychosocial changes and challenges (e.g., new setting, new peers, new academics) as well as formulating or solidifying their individual development (e.g., Newman, Lohman, Newman, Myers, & Smith, 2000). Figure 3 shows that as expected at baseline, adolescents with peers engaging in deviant behavior begin the study much more involved in substance use compared to adolescent without deviant peers. Among the peer behaviors, having peers that offer substances increases tobacco and cannabis use at 24 months, whereas the influence of the other peer behaviors appears to attenuate by 24 months.

This finding also extends the literature on offers to use substances, which has demonstrated the relationship between offers and subsequent cannabis use (Andreas & Pape, 2015; Pinchevsky, Arria, Caldeira, Garnier-Dykstra, Vincent, & O’Grady, 2012). Receiving offers to use a substance is an explicit opportunity to become involved with a specific group of friends in a specific deviant behavior, and thus could serve as an entry into a peer group. This transition may signify a critical transition into healthy or risky behavioral trajectory, as well as serving as red-flag when attempting to understand adolescent risk and protective factors. For example, depending on the context, those who work directly with adolescents regarding substance use may want to develop sensitive ways to assess friend behaviors, as well as to consider subtle ways to encourage the adolescent to consider spending less time in risky settings with those friends who are offering substances.

There is growing evidence that Peer Network Counseling (PNC) may be a useful tool for addressing adolescent substance use by leveraging peer relations. PNC is a brief intervention rooted in motivational interviewing that encourages youth to assess their substance use as well as the friends with whom they spend time, and to examine where they spend time with friends. Participants are then encouraged to consider making small adjustments to their peer network context to make changes in their substance use (Mason et al., 2015a). Research has shown that PNC is successful in reducing youth tobacco use (Mason, Mennis, Way, Lanza, Russell, & Zaharakis, 2015b; Mason et al., 2016) and cannabis use (Mason et al., 2015a; Mason, Sabo, & Zaharakis, 2017).

There are several study limitations to consider when interpreting these results. First, our sample was an urban, primarily young African American sample; therefore, our findings may not apply to other populations. Replications with more diverse ethnic and geographic populations are needed. In addition, our sample was drawn from adolescent health clinics in an academic medical center and a public housing clinic, and thus, may not generalize to non-primary care samples. Second, we limited our friend network measure to collect data on each participant’s three closest friends. While this is in line with data on the average number of nominated close friends among adolescents (Ali et al., 2011) and relevant to our hypotheses, findings may differ for a more expanded inclusion of friendships. Future studies could examine more extensive friend networks to determine if these findings vary with the size of an adolescent’s friend network. Third, the closeness measure was one item with a restrictive three-point scale. This may have limited the influence of this variable. Further, closeness is only one aspect of friendship quality, and researching the influence of other aspects such as friendship conflict, helpfulness, companionship, and trust/security (Cillessen, Jian, West, & Laszkowski, 2005; Simpkins, Parke, Flyr, & Wild, 2006) would likely contribute additional findings. Fourth, the item that assessed risk behaviors combined multiple behaviors into one question, hampering the ability to specify the role of each of these different activities. Given the limits of time in conducting peer relations research, collecting more data is often challenging. However, based on these results, breaking out these behaviors is warranted and would allow researchers to better understand more specifically the role of deviant behaviors in substance use. A low recruitment response rate might have contributed to our sample’s limited generalizability. Many families decided not to participate because of time constraints or lack of resources (e.g., limited transportation to return for enrollment appointment, lack of childcare for other children). Thus, our sample may be less representative of families experiencing higher demands or stresses on their time. Low prevalence rates among this sample may have limited the analytical outcomes. Even though our sample was primarily African American adolescents who typically use less tobacco and alcohol than their White and Hispanic counterparts, the prevalence rates are low compared with national data broken out by high school grade and race/ethnicity (Johnston et al., 2017). This may be a function unique to this sample or a measurement issue such as having a parent in the next room, or being at a medical clinic, while the adolescent reported on their substance use.

In all, this study provides insight into the role of specific friend behaviors associated with substance use. A challenge for this area of research is to understand that closeness is strengthened by common substance use (Boman et al., 2013). While substance using behavior is risk enhancing for many health outcomes, the simultaneous bonding among close substance using peers is likely to be perceived as positive and may reinforce ongoing affiliation and risk behaviors. Thus, attempting to directly separate adolescents from peers is likely to be met with resistance. Including more details regarding close friends’ behaviors and feelings of closeness in future research could advance the field of peer effects research and has the potential to inform personalized, targeted interventions that could be effective in addressing adolescent substance use.

Implications and Contribution: Prospective, longitudinal data examined the prediction of adolescent substance use from perceptions of problematic behaviors of close friends. Adolescents with close friends who were substance users, who made offers to use substances, and who engaged in risky behaviors were more likely to use tobacco and cannabis. Perceptions of young adolescents’ close friends’ behaviors influenced their substance use up to two years later.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institutes on Health, NIDA Grant Number DA031724-01A1

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors do not to have any conflicts of interest with the research presented in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Mason, Center for Behavioral Health Research, University of Tennessee

Nikola M. Zaharakis, Center for Behavioral Health Research, University of Tennessee

Julie C. Rusby, Oregon Research Institute

Erika Westling, Oregon Research Institute.

John M. Light, Oregon Research Institute

Jeremy Mennis, Geography and Urban Studies, Temple University.

Brian R. Flay, School of Social and Behavioral Health Sciences, Oregon State University

References

- Ali MM, Amialchuk A, & Dwyer DS (2011). The social contagion effect of marijuana use among adolescents. PloS one, 6(1), el6183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreas JB, & Pape H (2015). Who receives cannabis use offers: a general population study of adolescents. Drug and alcohol dependence, 156, 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, & Baglioni AJJ (2002). Measuring Risk And Protective Factors For Use, Delinquency, And Other Adolescent Problem Behaviors: The Communities That Care Youth Survey. Evaluation Review, 26, 575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, & Ennett ST (1996). On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: Commonly neglected considerations. Addiction, 91(2), 185–198. 10.1080/09652149640608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles S, Biglan A, & Smolkowski K (2006). Relationships among negative and positive behaviours in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 33–52. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman IV JH, Stogner J, & Lee Miller B (2013). Binge drinking, marijuana use, and friendships: the relationship between similar and dissimilar usage and friendship quality. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 45(3), 218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Jiang XL, West TV, and Laszkowski DK (2005). Predictors of dyadic friendship quality in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JE, Emery RE, & Turkheimer E (2012). Peer network drinking predicts increased alcohol use from adolescence to early adulthood after controlling for genetic and shared environmental selection. Developmental psychology, 48(5), 1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch AR, Chernyavskiy P, Steinley D, & Slutske WS (2015). Measuring peer socialization for adolescent substance use: A comparison of perceived and actual friends’ substance use effects. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 76(2), 267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Simons L, & Simons R, (2014). Factors that influence trajectories of delinquency throughout adolescence. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 45, 156–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, & Augustyn MB (2017). Intergenerational continuity in cannabis use: the role of parent's early onset and lifetime disorder on child's early onset. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, Fujimoto K, Pentz MA, Jordan-Marsh M, & Valente TW (2014). Peer influences: the impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(5), 508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AB, Burk WJ, Weesie J, & Steglich C (2011). Friendship and alcohol use in early adolescence: A multilevel social network approach. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(2), 475–487. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD & Thomberry TP 1993. Network theory: A model for understanding drug abuse for African-American and Hispanic youth In: De La Rosa MR & Adrados JR (Eds.) Drug Abuse Among Minority Youth: Methodological Issues and Recent Research Advances, pp. 102–128. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Light JM, & Dishion TJ (2007). Early adolescent antisocial behavior and peer rejection: A dynamic test of a developmental process. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 118, 77–90. doi: 10.1002/ed.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light JM, Greenan CC, Rusby JC, Nies KM, & Snijders TA (2013). Onset to first alcohol use in early adolescence: A network diffusion model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(3), 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Pérez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, et al. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;115(1–2): 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Mennis J, & Schmidt CD (2011). A social operational model of urban adolescents’ tobacco and substance use: A mediational analysis. Journal of adolescence, 34(5), 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Sabo R, & Zaharakis NM (2017). Peer network counseling as brief treatment for urban adolescent heavy cannabis users. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75(1), 152–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Cheung I, & Walker L (2004). Substance use, social networks, and the geography of urban adolescents. Substance use & misuse, 39(10-12), 1751–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Light J, Campbell L, Keyser-Marcus L, Crewe S, Way T, Saunders H, King L, Zaharakis NM, & McHenry C (2015a). Peer network counseling with urban adolescents: A randomized controlled trial with moderate substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 58, 16–24. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Mennis J, Linker J, Bares C, & Zaharakis N (2014). Peer attitudes effects on adolescent substance use: The moderating role of race and gender. Prevention Science, 15, 56–64. 10.1007/s11121-012-0353-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Mennis J, Way T, Lanza S, Russell M, & Zaharakis N (2015b). Time-varying effects of a text-based smoking cessation intervention for urban adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 99–105. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams TA, Salekin RT, Marti CN, Lester WS, & Barker ED, (2014). Co-occurrence of antisocial behavior and substance use: Testing for sex differences in the impact of older male friends, low parental knowledge and friends’ delinquency. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DP, & Hahn L (1991). The adolescent drug involvement scale. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 2(1), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Newman BM, Lohman BJ, Newman PR, Myers MC, & Smith VL (2000). Experiences of urban youth navigating the transition to ninth grade. Youth & Society, 57(4), 387–416. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M, Steglich C, & Snijders T (2006). Homophily and assimilation among sport-active adolescent substance users. Connections, 27(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchevsky GM, Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Garnier-Dykstra LM, Vincent KB, & O’Grady KE (2012). Marijuana exposure opportunity and initiation during college: parent and peer influences. Prevention Science, 13, 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Greene D, & House P (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of experimental social psychology, 73(3), 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Perry CL, & Williams CL (2000). Do friendships change behaviors, or do behaviors change friendships? Examining paths of influence in young adolescents' alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(1), 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins SD, Parke RD, Flyr ML, & Wild ΜN (2006). Similarities in children’s and early adolescents’ perceptions of friendship qualities across development, gender, and friendship qualitites. Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 491–508. DOI: 10.1177/0272431606291941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smolkowski K, Biglan A, Dent C, & Seeley J (2006). The multilevel structure of four adolescent problems. Prevention Science, 7, 239–256. doi: 10.1007/slll21-006-0034-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Unger JB, & Johnson CA (2005). Do popular students smoke? The association between popularity and smoking among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(4), 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]