Abstract

A series of derivatives of the 4,5-disubstituted class of 2-deoxystreptamine aminoglycoside antibiotics neomycin, paromomycin, and ribostamycin was prepared and assayed for (i) their ability to inhibit protein synthesis by bacterial ribosomes and by engineered bacterial ribosomes carrying eukaryotic decoding A sites, (ii) antibacterial activity against wild type Gram negative and positive pathogens, and (iii) overcoming resistance due to the presence of aminoacyl transferases acting at the 2′-position. The presence of five suitably positioned residual basic amino groups was found to be necessary for activity to be retained upon removal or alkylation of the 2′-position amine. As alkylation of the 2′-amino group overcomes the action of resistance determinants acting at that position and in addition results in increased selectivity for the prokaryotic over eukaryotic ribosomes, it constitutes an attractive modification for introduction into next generation aminoglycosides. In the neomycin series, the installation of small (formamide) or basic (glycinamide) amido groups on the 2′-amino group is tolerated.

Keywords: aminoglycosides, multidrug-resistant infectious diseases, decoding A site, selectivity, synthesis

The increasing threat of multidrug-resistant infectious diseases demands continued development of new and improved anti-infective agents.1−6 In this regard, aminoglycosides (AGAs)7−11 are strong candidates for further development because of their widespread availability, innate potency, and the extensive knowledge base covering their mechanism of action10,12,13 and chemistry.7,14−16 Together with the deep understanding of the mechanism of resistance, this knowledge base has long informed the structure-based design of new generations of AGAs,17−24 as exemplified by the recent introduction of the semisynthetic AGA plazomicin 1 into clinical practice.25,26 In addition to many aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs),27−30 a second important and growing mechanism of AGA resistance is the modification of G1405 in the drug binding pocket in the decoding A site of the bacterial ribosome by the ribosomal methyl transferases (RMTs).31 The action of the G1405 RMTs greatly diminishes the activity of all members of the 4,6-disubstituted 2-deoxystreptamine (DOS) class of AGAs, that is, all AGAs in current clinical use including plazomicin,25,26,32 and is especially problematic when the responsible genes are encoded on the same plasmid as those for a metallocarbapenemase.31,33−35 Fortunately, DOS-type AGAs lacking a ring substitution at the 6-position do not make direct contact with G1405 and are not susceptible to the action of RMTs.36 Such AGAs include the 4,5-disubstituted DOS class such as paromomycin 2 and neomycin 3, and the unusual monosubstituted DOS AGA apramycin 4,37−41 currently a clinical candidate for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections.42

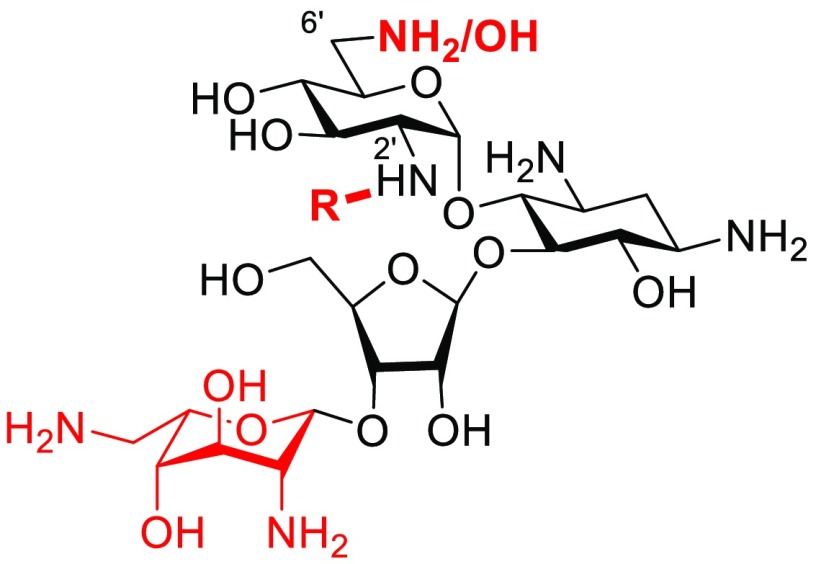

Accordingly, we have focused our efforts on the design and development of semisynthetic AGAs in the 4,5-DOS class with emphasis on modification at the 4′- and 6′-positions of paromomycin,43−46 as exemplified by propylamycin 5 (4′-deoxy-4′-propylparomomycin).47 In addition to thwarting the action of several AMEs, we discovered that the introduction of appropriate substituents to the 4′-position of paromomycin disproportionately reduces affinity for the drug binding site in the eukaryotic ribosomes, cytoplasmic and mitochondrial, thereby increasing target selectivity and reducing ototoxicity, an important side effect of AGA therapy,48−50 as borne out by in vivo studies with guinea pigs.44,47 Stimulated by early observations in the literature on the derivatization of the 2′-position of paromomycin and neomycin directed at circumventing the action of the AAC(2′) class of aminoglycoside acetyl transferase AMEs,51−53 we now turn our attention to and report here on the possibility of circumventing AME action in conjunction with improvements in target selectivity by modification at the 2′-position of paromomycin 2, neomycin 3, and ribostamycin 6 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Some natural and semisynthetic aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Results

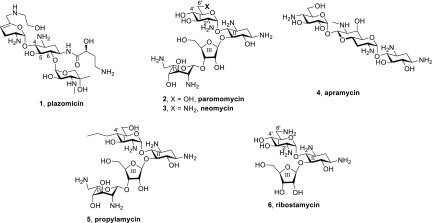

Chemical Synthesis

By adapting a literature procedure for the regioselective tetra-N-acetylation of paromomycin,51 treatment of a solution of paromomycin 2 and neomycin B 3 free bases in methanol containing 1N aqueous HCl with acetic anhydride gave 1,3,2′′′,6′′′-tetra-N-acetyl paromomycin 7 and 1,3,6′,2′′′,6′′′-penta-N-acetyl neomycin 8 as the major products in 41 and 39% isolated yields, respectively. Reductive amination of both 7 and 8 with benzaldehyde, followed by a second reductive amination with formaldehyde, and, in the case of the neomycin derivative by peracetylation, afforded the 2′-N-benzyl-2′-N-methyl paromomycin and neomycin derivatives 9 and 10 in 48 and 62% yield, respectively (Scheme 1). Reductive amination of 7 with acetaldehyde and propionaldehyde gave 11 and 12, whereas treatment of 8 with acetaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride gave 13, all in moderate to good yield. Hydrogenolysis of 9 and 10 over palladium hydroxide in methanol followed by heating to reflux with either aqueous sodium hydroxide or barium hydroxide and then Sephadex chromatography gave the 2′-N-methyl derivatives 14 and 15 of paromomycin and neomycin, respectively. Simple heating of 11–13 with aqueous sodium or barium hydroxide followed by Sephadex chromatography afforded the known51 2′-N-ethyl paromomycin derivative 16, the corresponding neomycin derivative 18, and the 2′-N-propyl paromomycin derivative 17. All compounds in this and subsequent schemes were isolated as their peracetate salts following lyophilization from aqueous acetic acid.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2′-N-Alkyl Derivatives of Paromomycin and Neomycin.

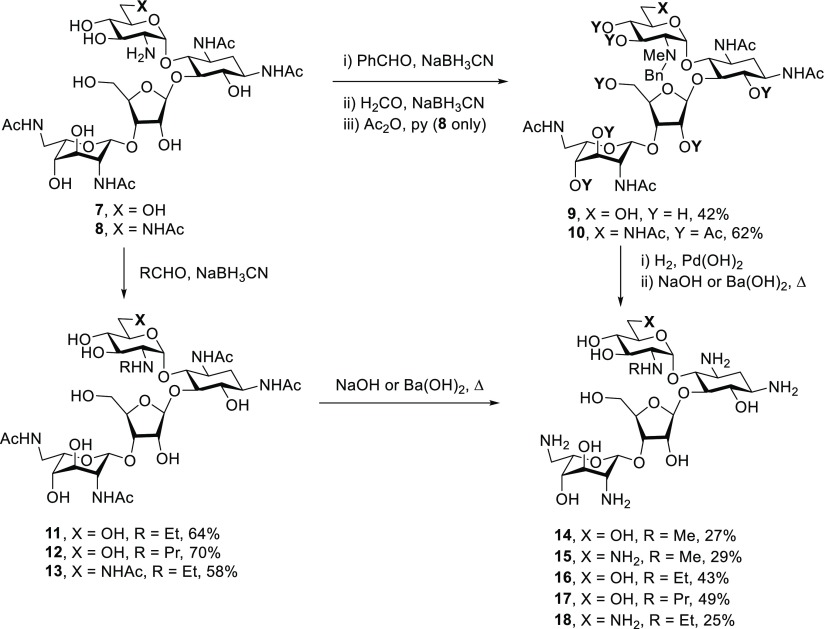

Following the Farmitalia protocol,52 installation of a benzyl carbamate on the amino group of 7 followed by peracetylation gave 19 in 57% yield. Hydrogenolysis of 19 followed by diazotization in aqueous acetic acid gave the known52 pseudotrisaccharide 20 in 52% yield. Glycosylation of acceptor 20 with donors 21 and 22, prepared as described in the literature,54,55 with activation by N-iodosuccinimide and trimethylsilyl triflate in a mixture of dichloromethane and dimethylformamide, so as to obtain the axial glycosides selectively,56 gave 23 and 24 in 46 and 29% yield, respectively. Hydrogenolysis, heating to reflux in aqueous sodium hydroxide, and Sephadex chromatography then gave the 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy paromomycin and neomycin derivatives 25 and 26, respectively (Scheme 2). Glycosylation with donor 21 leading directly to the glycoside 23 was considered preferable to the more elaborate sequence employed previously in the preparation of 25 from 20 by the Farmitalia group who nevertheless favored the use of DMF as solvent in their glycosylation reaction.52 The cleavage of ring I from 19 by the nitrosylation protocol confirms the regioselectivity of the initial partial acetylation of 2 giving 7 (Scheme 1) and of all subsequent derivatives of it.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 2′-Desamino-2′-hydroxy Paromomycin and Neomycin Derivatives.

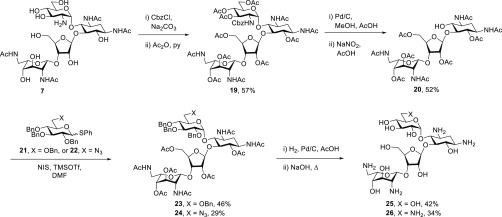

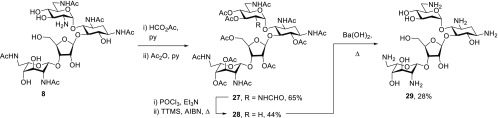

Formylation of 8 with formic acetic anhydride followed by acetylation gave the 2′-N-formyl neomycin derivative 27. This was converted by reaction with phosphorus oxychloride and triethylamine to the corresponding isocyanate, which without characterization was subject to the Barton deamination reaction57−59 using tris(trimethylsilyl)silane60 in place of the original tributyltin hydride, to afford the 2′-desamino derivative 28 in 44% yield for the two steps. Hydrolysis with hot barium hydroxide then afforded 29 in the standard manner (Scheme 3). No attempt was made to prepare the corresponding 2′-desamino paromomycin derivative in view of the modest antibacterial activity of the 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy paromomycin derivative 25.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 2′-Desamino Neomycin.

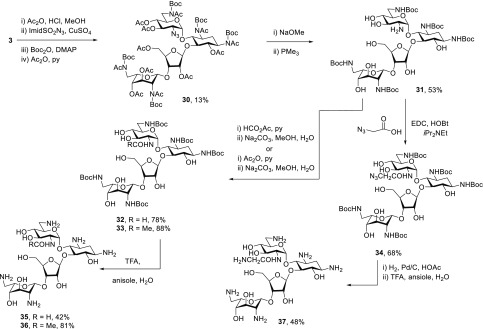

Turning to the preparation of 2′-N-acyl derivatives, neomycin B 3 was treated with acetic anhydride in the presence of HCl to give crude 8, which was subjected to reaction with imidazole sulfonyl azide61−64 and potassium carbonate in the presence of copper sulfate to give the corresponding 2′-azido derivative. Without isolation, and adopting the Grieco protocol for acetamide cleavage,65 this compound was heated to reflux in tetrahydrofuran with Boc2O and DMAP, followed by acetylation with acetic anhydride in pyridine to give 30 in 13% overall yield for the four steps from 3 (Scheme 4). Treatment with sodium methoxide in methanol followed by Staudinger reduction of the azide with trimethylphosphine66 then afforded a 2′-amine 31 suitable for installation of various amides. Treatment of 31 with formic acetic anhydride or acetic anhydride in pyridine followed by aqueous methanolic sodium carbonate then gave amides 32 and 33 in 78 and 88% yield, respectively. Coupling of 31 with azidoacetic acid67 by means of EDC and HOBt gave the azido acetamide 34 in 68% yield. Finally, stirring of 32 and 33 with wet trifluoroacetic acid in the presence of anisole, followed by sephadex chromatography and lyophilization from acetic acid gave the 2′-N-formamide 35, and an authentic sample of the acetamide 36 in 42, and 81% yields, respectively. In the case of the glycinamide 37, isolated in 48% yield, the removal of the carbamate groups was preceded by reduction of the azide (Scheme 4). It is of interest, although not inconsistent with the literature,68−70 that the formamide 35 exists in D2O solution as an unassigned 7:3 mixture of rotamers.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Neomycin 2′-Amides.

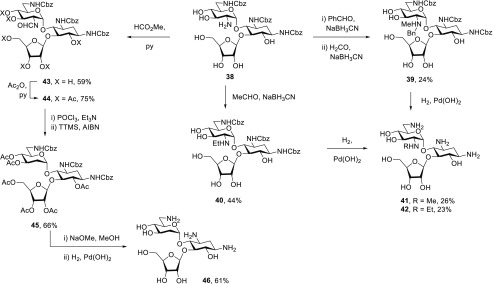

In the ribostamycin series, the parent 6 was regioselectively protected as the 1,3,6′-tris(benzyloxycarbamate) 38 by treatment with N-(benzyloxycarbonyloxy)-5-norborene-endo-2,3-dicarboximide (NBD)71 in the presence of sodium carbonate in 36% yield. Sequential reductive amination with benzaldehyde and then with formaldehyde gave the 2′-N-benzyl-2′-N-methyl derivative 39 in 24% yield, while parallel treatment with acetaldehyde and sodium cyanoborohydride gave the 2′-N-ethyl derivative 40 in 44% yield. Hydrogenolysis of 39 and 40 over palladium hydroxide then afforded 2′-N-methyl and 2′-N-ethyl ribostamycin, 41 and 42, in 26 and 23% yield, respectively (Scheme 5). Reaction of 38 with formic acetic anhydride and pyridine provided the 2′-formamide 43 in 59%, which was converted to the peracetate 44 in 75% yield in the standard manner. Dehydration of 44 with phosphorusoxy chloride and triethylamine afforded the corresponding 2′-isonitrile, which was subjected to tris(trimethylsilyl)silane and AIBN in hot toluene to give the 2′-desamino derivative 45 in 66% yield for the two steps. Deprotection with sodium methoxide in methanol followed by hydrogenloysis then afforded 2′-desamino ribostamycin 46 in 61% yield.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of Ribostamycin Derivatives 41, 42, and 46.

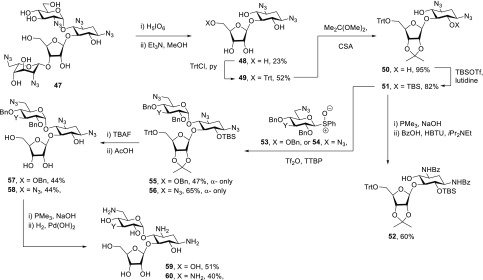

To prepare 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy ribostamycin derivatives, we again took an approach based on glycosylation of a 2-deoxystreptamine derivative. Thus, adapting Hanessian’s protocol for the degradation of rings I and IV,72 the perazido paromomycin derivative 47(73) was treated with periodic acid followed by triethylamine to afford the 5-O-ribosyl-2-deoxystreptamine derivative 48 in 23% yield (Scheme 6). Installation of a trityl group on the primary alcohol to give 49 in 52% was followed by conversion of the cis-diol to the corresponding acetonide 50 in 95% yield with 2,2-dimethoxypropane under catalysis by camphor-10-sufonic acid. Treatment of 50 with tert-butyldimethylsilyl triflate in the presence of 2,6-lutidine gave a single monosilyl ether 51 in 82% yield. Notwithstanding the literature precedent for the regioselective monofunctionalization of 50-like diols at the 6-position,7451 was converted to the crystalline derivative 52 in 60% yield by Staudinger reduction of the azides followed by amide formation, whose structures were confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Supporting Information, Figure S1, CCDC 1908319). The glycosyl acceptor 51 was converted to the α-glycoside 55 in 47% yield by means of reaction with sulfoxide 53 (Supporting Information) on activation with triflic anhydride. Similarly, glycosylation of 51 with sulfoxide 54 (Supporting Information) gave the α-glycoside 56 in 65% yield. Treatment of 55 and 56 with tetrabutylammonium fluoride and then acetic acid affording the triols 57 and 58, both in 44% yield, was followed by Staudinger reaction and hydrogenolysis to give 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy ribostamycin 59 and the ribostamycin regioisomer 60 in 51 and 40% yields, respectively (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Synthesis of Ribostamycin Derivatives 59 and 60.

Activity and Selectivity at the Target Level

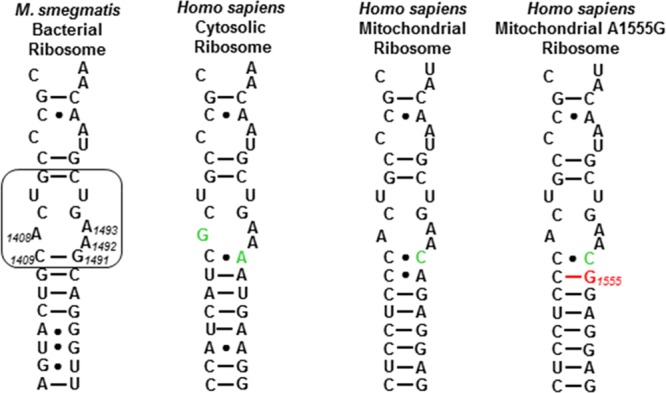

All compounds were studied for their ability to inhibit protein synthesis in a series of cell-free translation assays as described previously.43 These assays employed wild-type bacterial Mycobacterium smegmatis ribosomes and humanized hybrid M. smegmatis ribosomes carrying complete eukaryotic decoding A sites, that is, the crystallographically characterized drug binding pocket (Figure 3),36,75 from human mitochondrial ribosomes (Mit 13), A1555G mutant mitochondrial ribosomes (A1555), and human cytoplasmic ribosomes (Cyt 14) (Figure 2 and Table 1).76 This model system, developed in our laboratories, was previously employed to identify the mitoribosome as target in aminoglycoside ototoxicity,77 to study the mechanisms of mutant rRNA-associated deafness,78 and to rationalize aminoglycoside activity against protozoa.79 In the series of experiments reported in Table 1, inhibition of the mitochondrial ribosome, together with slow clearance from the inner ear, is thought to be the root cause of AGA-induced ototoxicity; the hypersusceptibility to AGA-induced ototoxicity found in a subset of the population arises from the presence of the A1555G mutation in the mitochondrial decoding A site.77,78,80,81 Inhibition of the human cytoplasmic ribosome on the other hand is expected to result in more systemic toxicity.

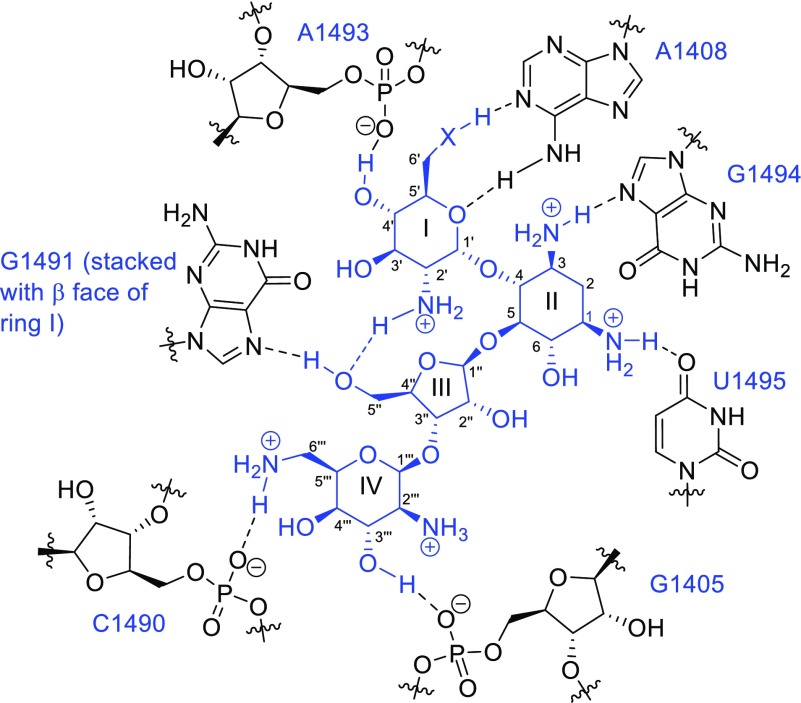

Figure 3.

Schematic of the crystallographically determined interactions of neomycin 3 (X = NH2+) and paromomycin 2 (X = O) with the AGA binding pocket. Ribostamycin 6 (X = NH2+) binds identically but lacks ring IV.

Figure 2.

Decoding A sites of prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosomes. The bacterial AGA binding pocket is boxed. The bacterial numbering scheme is illustrated for the AGA binding pocket. Changes from the bacterial ribosome binding pocket are colored green. The A1555G mutant conferring hypersusceptibility to AGA ototoxicity is colored red.

Table 1. Antiribosomal Activities (IC50,μM) and Selectivitiesa.

| substituent |

IC50, μM |

selectivity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | 6′ | 2′ | basic amino groups | bacterial | Mit13 | A1555G | Cyt14 | Mit13 | A1555G | Cyt14 |

| Neomycin Series | ||||||||||

| 3 | NH2 | NH2 | 6 | 0.04 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 36 | 108 | 10 | 900 |

| 15 | NH2 | NHMe | 6 | 0.01 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 37 | 470 | 110 | 3700 |

| 18 | NH2 | NHEt | 6 | 0.02 | 11 | 1.6 | 43 | 550 | 80 | 2150 |

| 26 | NH2 | OH | 5 | 0.03 | 36 | 2.9 | 108 | 1200 | 97 | 3600 |

| 29 | NH2 | H | 5 | 0.03 | 22 | 0.9 | 85 | 773 | 30 | 2833 |

| 35 | NH2 | NHCHO | 5 | 0.12 | 54 | 13 | 127 | 450 | 108 | 1058 |

| 36 | NH2 | NHAc | 5 | 5.3 | 93 | 28 | 147 | 18 | 5.3 | 28 |

| 37 | NH2 | NHglycyl | 5 | 0.16 | 11 | 1.2 | 25 | 69 | 8 | 156 |

| Paromomycin Series | ||||||||||

| 2 | OH | NH2 | 5 | 0.04 | 142 | 12 | 31 | 3550 | 300 | 775 |

| 14 | OH | NHMe | 4 | 0.05 | 150 | 54 | 60 | 3000 | 1080 | 1200 |

| 16 | OH | NHEt | 5 | 0.05 | 220 | 84 | 43 | 4400 | 1680 | 860 |

| 17 | OH | NHPr | 5 | 0.07 | 223 | 58 | 32 | 3186 | 829 | 457 |

| 25 | OH | OH | 4 | 2.2 | 662 | 313 | 446 | 301 | 142 | 203 |

| Ribostamycin Series | ||||||||||

| 6 | NH2 | NH2 | 4 | 0.10 | ||||||

| 41 | NH2 | NHMe | 4 | 1.13 | ||||||

| 42 | NH2 | NHEt | 1.93 | |||||||

| 59 | NH2 | OH | 3 | 2.66 | ||||||

| 46 | NH2 | H | 3 | 9.93 | ||||||

| 60b | NH2 | OH | 4 | >20 | ||||||

Selectivities are obtained by dividing the eukaryotic by the bacterial values.

Compound 60 is additionally modified at the 3′-position by replacement of the hydroxyl group by an amino group.

As shown in Table 1, 2′-N-methylation and ethylation have little to no effect on the ability of paromomycin or neomycin to inhibit translation by the bacterial ribosome. Even 2′-N-propylation has a minimal effect as demonstrated with the paromomycin derivative 17. The effects of these 2′-N-alkylations on translation by the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic hybrid ribosomes are minimal for paromomycin but result in significant increases in selectivity for neomycin. In addition, these modifications have a marked effect on A1555G mutant mitochondrial ribosomes resulting in increases in selectivity of between 3- and 10-fold. The minimal loss of inhibitory activity of 2′-N-ethyl paromomycin for the bacterial ribosome is consistent with the limited reduction in antibacterial activity observed previously for this modification.51 In contrast to the minimal influence of 2′-N-alkylation in the paromomycin and neomycin series, the comparable 2′-N-alkylated ribostamycin derivatives 41 and 42 were found to be 10-fold less active than the parent against the bacterial ribosome. In view of the low antibacterioribosomal activity of 41 and 42 and all subsequent ribostamycin derivatives, the activity of ribostamycin compounds against the eukaryotic ribosomes was not investigated.

Substitution of a hydroxyl group for an amino group at the 2′-position has minimal influence on antiribosomal activity in the neomycin series (analogue 26), consistent with the antibacterial activity reported for this compound previously.52 Notably, a significant increase in selectivity for all eukaryotic decoding sites (mitochondrial, A1555G, and cytosolic) is achieved by the 2′-hydroxyl modification. However, the identical substitution is detrimental for both paromomycin and ribostamycin as evidenced by the corresponding paromomycin and ribostamycin analogues 25 and 59. The high activity of 26 suggested that further such modifications would be tolerated in the neomycin series, as was borne out by the 2′-desamino neomycin derivative 29, which again displays increased across the board selectivity compared to the parent. The substantially reduced activity of 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy paromomycin 25 and of 2′-desaminoribostamycin 46 discouraged us from making any further modifications to the 2′-position of paromomycin and ribostamycin that result in loss of the basic amine. In an attempt to remove the 2′-amino group without a change in the number of basic amines present, ribostamycin was converted to the regioisomer 60 in which the 2′-amino group has been substituted by an hydroxyl group, while the inverse modification was affected at the 3′-position. Unfortunately, this modification was associated with a substantial loss of activity.

Turning to the installation of amides at the 2′-position, and restricting ourselves to the neomycin series, formylation giving the neomycin derivative 35 resulted in little loss of activity against the bacterial ribosome coupled with a substantial increase in selectivity for the mitochondrial and mutant mitochondrial ribosomes. This is in contrast to 2′-N-acetylation, the modification introduced by the AAC(2′) family of AMEs, which led to a greater than 100-fold loss in activity in derivative 36. The negative influence of the 2′-N-acetyl modification on activity can be largely overcome by its coupling with the reinstallation of a basic amine as in the 2′-N-glycyl neomycin derivative 37, which shows only a 4-fold loss of activity against the bacterial ribosome compared to the parent. However, this modification comes with a substantial loss in selectivity with regard to the cytoplasmic ribosome. These observations on the influence of amide formation at the 2′-position are consistent with the prior literature describing other 2′-amides. Thus, it has been reported that the 2′-N-glycinamide derivatives of simple aminoalkyl 2,6-diamino-α-d-glucopyranosides, and of fortimicin B, retain antibacterial activity as does 2′-formamido sisomicin.82−84

Antibacterial Activity in the Absence and Presence of Aminoglycoside Modifying Enzymes

The antibacterial activities displayed by the various paromomycin, neomycin, and ribostamycin derivatives against clinical strains of the Gram-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the Gram-negative Escherichia coli (Table 2) were consistent with their ability to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis in the translation assays (Table 1). The more potent compounds were also screened for activity against a single wild-type clinical strain each of the ESKAPE pathogens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, and Acinetobacter baumannii, with MICs determined to be ≤4 μg/mL (Table 2).

Table 2. Antibacterial Activities (MIC, μg/mL)a.

| substituent |

MRSA |

E. coli |

K. pneu | E. cloa | A. baum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | 6′ | 2′ | AG038 | AG001 | AG003 | AG215 | AG290 | AG225 |

| Neomycin Series | ||||||||

| 3 | NH2 | NH2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.25–0.5 | 1 | 1–2 |

| 15 | NH2 | NHMe | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5–1 | 1 |

| 18 | NH2 | NHEt | 0.5 | 1–2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5–1 | 1 |

| 26 | NH2 | OH | 2 | 2–4 | 2–4 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 29 | NH2 | H | 1 | 2 | 1–2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 35 | NH2 | NHCHO | 2–4 | 4–8 | 4–8 | 1–2 | 2 | 2 |

| 36 | NH2 | NHAc | >128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| 37 | NH2 | NHglycyl | 4 | 16 | 32 | |||

| Paromomycin Series | ||||||||

| 2 | OH | NH2 | 4 | 2–4 | 4–8 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 16 | OH | NHEt | 8 | 16 | 16 | |||

| 14 | OH | NHMe | 8 | 8 | 16 | |||

| 17 | OH | NHPr | 8–16 | 16 | 16 | |||

| 25 | OH | OH | 64–128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| Ribostamycin Series | ||||||||

| 6 | NH2 | NH2 | 4 | 4–8 | 4–8 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 41 | NH2 | NHMe | 64–128 | 64–128 | 64 | |||

| 42 | NH2 | NHEt | >128 | 128 | 128 | |||

| 59 | NH2 | OH | >128 | >128 | >128 | |||

| 46 | NH2 | H | ≥256 | |||||

| 60b | NH2 | OH | >128 | >128 | >128 | |||

All values were determined in duplicate using 2-fold dilution series.

Compound 60 is additionally modified at the 3′-position by replacement of the hydroxyl group by an amino group.

As the 2′-amino group is the target for acetylation by the AAC(2′) class of AMEs, the more active compounds were screened for activity against two clinical strains of E. coli carrying different isoforms of AAC(2′) (Table 3). The presence of either of these AAC(2′) isoforms greatly abrogates the activity of both paromomycin and neomycin, consistent with the minimal activity of authentic 2′-N-acetyl neomycin 36. In contrast, 2′-N-methylation, ethylation, and propylation, compounds 14–18, maintains activity in the presence of AAC(2′). Similarly, the 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy and 2′-desamino modifications in the neomycin series, compounds 26 and 29, resist the AAC(2′) class of AMEs in E. coli, as does the 2′-N-formyl modification displayed in compound 35. Plazomicin, obtained by an improved synthesis,32 and amikacin, one carrying a 2′-amino group and the other a 2′-hydroxy group, served as controls for the AAC(2′) AMEs in E. coli.

Table 3. Antibacterial Activities Against E. coli Strains with Acquired AAC(2′) Resistance and Mycobacteria with Intrinsic AAC(2′) Resistance (MIC, μg/mL)a.

| substituent |

E. coli AG001 | E. coli AG106 | E. coli pH434 | M. abscessus ATCC 19977 (AAC2′) | ratio M. abscessus wt/E. coli wt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | 6′ | 2′ | wt | AAC(2′)-1a | AAC(2′)-1b | wt | |

| Neomycin Series | |||||||

| 3 | NH2 | NH2 | 1 | 16 | >64 | 16 | 16 |

| 15 | NH2 | NHMe | 2 | 2.0 | 2–4 | 0.25 | 0.125 |

| 18 | NH2 | NHEt | 1–2 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.125–0.25 |

| 26 | NH2 | OH | 2–4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.5–1.0 |

| 29 | NH2 | H | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 35 | NH2 | NHCHO | 4–8 | 8 | 8–16 | ||

| 37 | NH2 | NHglycyl | 16 | 16–32 | |||

| Paromomycin Series | |||||||

| 2 | OH | NH2 | 2–4 | >64 | >64 | 8 | 2–4 |

| 14 | OH | NHMe | 8 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 2 |

| 16 | OH | NHEt | 16 | 8 | 32 | 2 | |

| 17 | OH | NHPr | 16 | 8 | 32 | 2 | |

| Ribostamycin Series | |||||||

| 6 | NH2 | NH2 | 4–8 | 128 | >128 | ||

| plazomicin | 0.5–1 | 8–16 | 8 | ||||

| amikacin (2′OH) | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

All values were determined in duplicate using 2-fold dilution series.

Mycobacterium abscessus is a growing threat in hospitalized patients with chronic pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis.85 The innate AGA susceptibility of M. abscessus is determined by the presence of a functional AAC(2′) AME,86 prompting us to test the more active compounds against the M. abscessus reference strain ATCC 19977. To illustrate the effect of the mycobacterial AAC2′ on compound activity, we also calculated the ratio of M. abscessus wt (AAC2′ present) versus E. coli wt (no AAC2′ present). Inherently, the mycobacterial AAC2′ shows little activity toward paromomycin but significantly reduces the antimycobacterial activity of neomycin. In line with expectation, the 2′-N-alkyl derivatives of paromomycin 14, 16, and 17 did not show any difference compared to the parent; however, the same modifications in the neomycin series, as in compounds 15 and 18, were highly efficacious resulting in a 64-fold reduction in MIC values (Table 3). The 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy and 2′-desamino derivatives 26 and 29 of neomycin also showed much greater activity against M. abscessus than the parent.

Finally, selected compounds were screened for activity in the presence of AAC(3), AAC(6′), ANT(4′,4′′), and APH(3′). As expected, none of the modifications investigated was effective at suppressing the activity of these AMEs.

Discussion

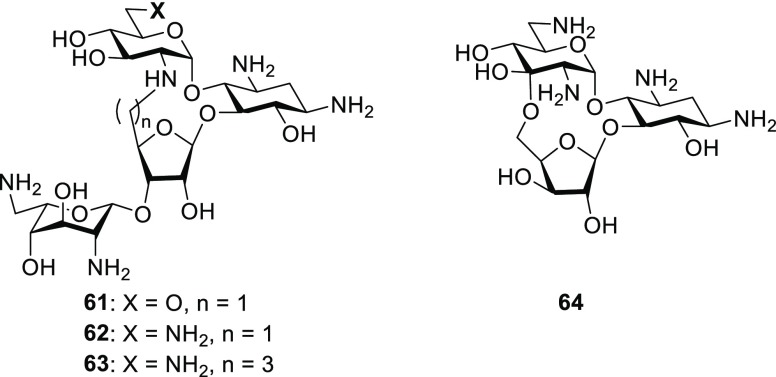

Classically, the activity of AGAs is considered to be correlated

to the number of basic amino groups87 and

so, following protonation at physiological pH, to the degree of electrostatic

attraction with the negatively charged drug binding pocket.88,89 The electrostatic component of the binding energy is supplemented

by a number of direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonding contacts

and other directional intermolecular noncovalent interactions between

the drug and the binding pocket (Figure 3).27,75,87,90−92 The partitioning of the contribution of an individual protonated

amine to the binding energy between electrostatic and directed components

necessarily varies with the location of the amine in the AGA. Thus,

while the amines of rings I and II of the 4,5-AGAs are involved in

multiple H-bonding interactions with the drug-binding pocket, those

of ring IV do so to a lesser extent (Figure 3). Indeed, it has been suggested that ring

IV serves simply as a concentration of positive charge that makes

a strong electrostatic contribution to the binding energy.93 Finally, intramolecular conformation-restricting

noncovalent interactions within the body of the drug itself have also

been suggested to be an important component of the binding energy.94 Among the hydrogen bonding interactions between

rings I and III of the 4,5-AGAs, specifically those between the protonated

2′-amino group and O4′′ or O5′′

of the ribofuranosyl moiety (Figure 3)75,95 are featured prominently. On

the basis of these interactions, Hermann and co-workers prepared the

conformationally restricted paromomycin and neomycin analogues 61 and 62 and studied their binding to the bacterial

decoding A site.96,97 Contemporaneously, and with a

view to exploiting the differing conformations of AGAs bound to the

decoding A site and that of the ANT(4′,4′′) AMEs,

Asensio and co-workers prepared 62 and the higher homologue 63.98,99 Other workers have prepared complex

aminoglycosides by ribofuranosylation of the 5-OH in the 4,6-AGAs

to take advantage of this intramolecular interaction and other contacts.100,101 Unfortunately, each of 61–63 showed

reduced affinity for decoding A site models and reduced antibacterial

activity, the latter in common with an earlier conformationally restricted

analogue 64 of the ribostamycin isomer xylostacin.102

The pattern of antibacterioribosomal activity (Table 1) and antibacterial activity (Table 2) of the present series of compounds, together with the reduced activity of 61–63, provides the opportunity to examine the interplay between electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions in greater detail. The parity in the ability of neomycin and its analogues 26 and 29 lacking the 2′-amino group to inhibit the function of the bacterial ribosome (Table 1) and the growth of wild-type Gram-negative pathogens (Table 2) indicates that the presence of five appropriately located protonated amino groups provides sufficient electrostatic attraction with the negatively charged ribosome to overcome the absence of the 2′-amino group for this scaffold. For paramomycin and ribostamycin on the other hand, with only five and four such basic amino groups, respectively, the reduction in the electrostatic component conferred by removal of the 2′-amino group is critical, as borne out by the reduced activity of 2′-desamino-2′-hydroxy paromomycin 25 with its four protonated amino groups and by the ribostamycin analogues 46 and 59, both with only three protonated amino groups (Tables 1 and 2). Compensating for the loss of C(2′)NH2 in 59 by reintroducing an amino group at the 3′ position, resulting in compound 60, did not restore activity. This indicates that in the ribostamycin series, with only four basic amino groups, electrostatic attraction alone is not sufficient for activity but must be complemented by location of one of these groups at the 2′-position.

Alkylation of N2′ is tolerated when the molecule possesses five or more suitably placed basic amines as is clear from the activity of the neomycin and paromomycin analogs 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 (Tables 1 and 3). The loss of activity observed for the 2′-N-alkylated ribostamycin analogues 41 and 42 on the other hand indicates that even the correct placement of four basic amino groups is insufficient to compensate for the destabilizing effect of the alkyl groups. The retention of activity of 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 contrasts with the reduced activity of the cyclic (2′-N-alkylated) neomycin and paromomycin derivatives 61–63. Cyclization of the 2′-amine onto the 5′′-position was reported to result in a reduction in basicity of the 2′-amine in 61 and 62 by ∼1.5 pKa units. This reduction in pKa is most likely due to the inductively electron-withdrawing O4′′ ribosyl ring oxygen, which is β- to N2′ in 61 and 62,103 albeit the authors suggested steric inhibition of solvation of the protonated amino group as the cause.96,97,104 Whatever the underlying reason for the reduction in basicity, affinity for the ribosome was restored under more acidic conditions, illustrating the importance of protonation of N2′ in overcoming the negative effect of the cyclic modification. Simple alkylation, as in 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18, on the other hand is expected to increase the basicity of N2′ consistent with their high levels of activity.103 The homologue 63 of 62 lacks the basicity-reducing vicinal relationship between N2′ and O4′′ present in 61 and 62 but also shows a significant reduction in antibacterial activity and affinity for a decoding A site model.99 This suggests that the diminished activity of 61–63 is at least in part due to other factors such as the loss of a crystallographically observed (Figure 3)75 hydrogen bond from 5′′–OH in the parent to N7 of G1491 at the bottom of the binding site.96−99 Overall, in the absence of cyclic constraints, the presence of a basic amino group at the 2′-position of the 4,5-AGAs is not necessary provided five other appropriately located basic amino groups are present in the molecule. When a 4,5-series AGA contains only four basic amino groups, one of them must be at the 2′-position. Alkylation of the 2′-amino group is tolerated in the absence of cyclic constraints provided there are a minimum of five basic amino groups in the molecule.

With regard to the 2′-N-acyl derivatives of neomycin, the loss of activity observed with the acetamide 36 was anticipated in view of the well-known ability of the AAC(2′) AMEs to significantly reduce the activity of AGAs (Table 2). In view of the high levels of activity retained by neomycin derivatives 26 and 29, both of which lack a basic nitrogen at the 2′-position, the loss of activity due to 2′-acetamide formation cannot result from a reduction in electrostatic binding energy in neomycin. The loss of activity on acetamide formation can also not be due to the inclusion of a hydrophobic methyl group, as simple 2′-N-alkylation is well tolerated in both paromomycin and neomycin. By a process of elimination, the detrimental effect of the 2′-acetamido group in the neomycin series must arise either from a steric interaction or an unfavorable electrostatic interaction involving the amide carbonyl group. The steric component of this interaction is more important for the 2′-acetamide than for the 2′-N-alkyl derivatives because of the rigid nature of the amide function and its well-known orientation with respect to the pyranose ring in all 2-deoxy-2-acetamido glucopyranose derivatives.69 Further, it results mainly from the presence of the acetamide methyl group as the corresponding formamide 36 is considerably more active. In addition to its smaller size, the formamide 36 is also capable of avoiding any unfavorable electrostatic interaction by population of the cis- rather than the trans-rotamer.70 Finally, the unfavorable interaction in the acetamide is not so large as to prevent docking of the drug into the binding site, as it can be partially overcome by the introduction of a further basic amino group as in the glycinamide 37.

Conclusion

Extensive structure activity relationships (SAR) have been provided, resulting from modification of the 2′-position by deletion, replacement by a hydroxy group, alkylation, and in part acylation of the AGAs neomycin, paromomycin, and ribostamycin. This SAR leads to a series of conclusions on the influence of modification at this position on ribosomal affinity and antibacterial activity. Thus, the presence of a basic amino group at the 2′-position of the 4,5-AGAs is not essential for activity provided five other suitably placed basic amines are present in the molecule. In contrast, a basic amino group is required at the 2′-position when a 4,5-series AGA contains only four such basic amines. With five correctly placed basic amino groups present, alkylation of the 2′-amine is tolerated. Most notably, in paromomycin and in particular neomycin modification of the 2′-amino group also results in a gain in selectivity for the bacterial over the eukaryotic ribosomes, thereby providing an attractive means of both overcoming resistance due to the presence of AAC(2′)-type resistance determinants and increasing ribosomal target selectivity by a single modification.

Finally, the changes in selectivity between the prokaryotic and the different eukaryotic ribosomes occasioned by the various modifications introduced at the 2′-position (Table 1) presumably arise by indirect effects as the 2′-amine makes no direct contact with the drug binding pocket (Figure 3). These differential effects likely arise from interactions of the AGAs with the ribosomal base 1491, which is G in the bacterial ribosomes and A or C in the humanized ribosomes (Figure 2). Thus, modification of the 2′-substituent necessarily affects the CH−π interaction of the 4′–C–H bond with the base 1491 and, because of the H-bond network, the H-bond of the 5′′-hydroxyl group with the same base (Figure 3), both in a base-dependent manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (AI123352) for support and Dr. Philip Martin, WSU, for the X-ray structure. E.C.B. thanks the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF No. 407240_166998) and JPIAMR “RIBOTARGET” (SNF No. 40AR40_185777) for partial support of the work in Zurich.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00128.

Author Present Address

△ V.A.S.: Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, and Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, United States

Author Present Address

⊥ D.C.: Departments of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, and Chemistry, and Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, United States.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): D.C., A.V., S.N.H., and E.C.B. are cofounders of and have an equity interest in Juvabis AG, a biotech startup operating in the field of aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Supplementary Material

References

- Chang H.-H.; Cohen T.; Grad Y. H.; Hanage W. P.; O’Brien T. F.; Lipsitch M. (2015) Origin and Proliferation of Multiple-Drug Resistance in Bacterial Pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 79, 101–116. 10.1128/MMBR.00039-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. F.; Mobashery S. (2016) Endless Resistance. Endless Antibiotics?. MedChemComm 7, 37–49. 10.1039/C5MD00394F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton J. N.; Gorman S. P.; Gilmore B. F. (2013) Clinical Relevance of ESKAPE Pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 11, 297–308. 10.1586/eri.13.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell K. M. G.; Hodgkinson J. T.; Sore H. F.; Welch M.; Salmond G. P. C.; Spring D. R. (2013) Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: Current Strategies for the Discovery of Novel Antibacterials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52, 10706–10733. 10.1002/anie.201209979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G. D. (2015) Solving the Antibiotic Crisis. ACS Infect. Dis. 1, 80–84. 10.1021/id500052s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P. M.; Seiple I. B.; Myers A. G. (2014) The Evolving Role of Chemical Synthesis in Antibacterial Drug Discovery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 8840–8863. 10.1002/anie.201310843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa S. (1974) Structures and Syntheses of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 30, 111–182. 10.1016/S0065-2318(08)60264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad J., Kotra L. P., and Mobashery S. (2001) in Glycochemsitry: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications (Wang P. G., and Bertozzi C. R., Eds.) pp 307–351, Dekker, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Vakulenko S. B.; Mobashery S. (2003) Versatility of Aminoglycosides and Prospects for Their Future. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16, 430–450. 10.1128/CMR.16.3.430-450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2007) Aminoglycoside Antibiotics: From Chemical Biology to Drug Discovery (Arya D. P., Ed.) Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J.; Chen C.; Buising K. (2013) Aminoglycosides: How Should We Use Them in the 21st Century?. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 26, 516–525. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicens Q.; Westhof E. (2003) RNA as a Drug Target: The Case of Aminoglycosides. ChemBioChem 4, 1018–1023. 10.1002/cbic.200300684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo J., and Westhof E. (2014) in Antibioitcs: Targets, Mechanisms and Resistance (Gualerzi C. O., Brandi L., Fabbretti A., and Pon C. L., Eds.) pp 453–470, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad J., Liu M.-Z., and Mobashery S. (2001) in Glycochemistry: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications (Wang P. G., and Bertozzi C. R., Eds.) pp 353–424, Dekker, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., and Chang C.-W. T. (2007) in Aminoglycoside Antibiotics (Arya D. P., Ed.) pp 141–180, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Berkov-Zrihen Y., and Fridman M. (2014) in Modern Synthetic Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry; From Monosaccharides to Complex Glycoconjugates (Werz D. B., and Vidal S., Eds.) pp 161–190, Wiley, Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Price K. E.; Godfrey J. C.; Kawaguchi H. (1974) Effect of Structural Modifications on the Biological Properties of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Containing 2-Deoxystreptamine. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 18, 191–307. 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B.; Cooper M. A. (2013) Aminoglycoside Antibiotics in the 21st Century. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 105–115. 10.1021/cb3005116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Ye X. S. (2010) Development of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Effective Against Resistant Bacterial Strains. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 10, 1898–1926. 10.2174/156802610793176684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong E. S., Kostrub C. F., Cass R. T., Moser H. E., Serio A. W., and Miller G. H. (2012) in Antibiotic Discovery and Development (Dougherty T. J., and Pucci M. J., Eds.) pp 229–269, Springer Science+Business Media, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrika N. T.; Garneau-Tsodikova S. (2016) A Review of Patents (2011–2015) Towards Combating Resistance to and Toxicity of Aminoglycosides. MedChemComm 7, 50–68. 10.1039/C5MD00453E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamban Chandrika N.; Garneau-Tsodikova S. (2018) Comprehensive Review of Chemical Strategies for the Preparation of New Aminoglycosides and their Biological Activities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 1189–1249. 10.1039/C7CS00407A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zárate S. G.; De la Cruz Claure M. L.; Benito-Arenas R.; Revuelta R.; Santana A. G.; Bastida A. (2018) Overcoming Aminoglycoside Enzymatic Resistance: Design of Novel Antibiotics and Inhibitors. Molecules 23, 284. 10.3390/molecules23020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y.; Igarashi M. (2018) Destination of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics in the ‘Post-Antibiotic Era’. J. Antibiot. 71, 4–14. 10.1038/ja.2017.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggen J. B.; Armstrong E. S.; Goldblum A. A.; Dozzo P.; Linsell M. S.; Gliedt M. J.; Hildebrandt D. J.; Feeney L. A.; Kubo A.; Matias R. D.; Lopez S.; Gomez M.; Wlasichuk K. B.; Diokno R.; Miller G. H.; Moser H. E. (2010) Synthesis and Spectrum of the Neoglycoside ACHN-490. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4636–4642. 10.1128/AAC.00572-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G.; Ejim L.; Stogios P. J.; Koteva K.; Bordeleau E.; Evdokimova E.; Sieron A. O.; Savchenko A.; Serio A. W.; Krause K. M.; Wright G. D. (2018) Plazomicin Retains Antibiotic Activity against Most Aminoglycoside Modifying Enzymes. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 980–987. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnet S.; Blanchard J. S. (2005) Molecular Insights into Aminoglycoside Action and Resistance. Chem. Rev. 105, 477–497. 10.1021/cr0301088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M. S.; Tolmasky M. E. (2010) Aminoglycoside Modifiying Enzymes. Drug Resist. Updates 13, 151–171. 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau-Tsodikova S.; Labby K. J. (2016) Mechanisms of Resistance to Aminoglycoside Antibiotics: Overview and Perspectives. MedChemComm 7, 11–27. 10.1039/C5MD00344J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacot-Davis V. R.; Bassenden A. V.; Berghuis A. M. (2016) Drug-target Networks in Aminoglycoside Resistance: Hierarchy of Priority in Structural Drug Design. MedChemComm 7, 103–113. 10.1039/C5MD00384A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doi Y.; Wachino J. I.; Arakawa Y. (2016) Aminoglycoside Resistance: The Emergence of Acquired 16S Ribosomal RNA Methyltransferases. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 30, 523–537. 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonousi A.; Sarpe V. A.; Brilkova M.; Schacht J.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C.; Crich D. (2018) Effects of the 1-N-(4-Amino-2S-hydroxybutyryl) and 6′-N-(2-Hydroxyethyl) Substituents on Ribosomal Selectivity, Cochleotoxicity and Antibacterial Activity in the Sisomicin Class of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 1114–1120. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore D. M.; Mushtaq S.; Warner M.; Zhang J.-C.; Maharjan S.; Doumith M.; Woodford N. (2011) Activity of Aminoglycosides, Including ACHN-490, Against Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae Isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 48–53. 10.1093/jac/dkq408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.; Sriskandan S.; Woodford N.; Hopkins K. L. (2018) High Prevalence of 16S rRNA Methyltransferases Among Carbapenenase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the UK and Ireland. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 52, 278–282. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekarska K.; Zacharczuk K.; Wołkowicz T.; Rzeczkowska M.; Bareja E.; Olak M.; Gierczyński R. (2016) Distribution of 16S rRNA Methylases Among Different Species of Aminoglycoside-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Poland. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 25, 539–544. 10.17219/acem/34150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicens Q.; Westhof E. (2003) Molecular Recognition of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics by Ribosomal RNA and Resistance Enzymes: An Analysis of X-Ray Crystal Structures. Biopolymers 70, 42–57. 10.1002/bip.10414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor S.; Lam L. K. T.; Jones N. D.; Chaney M. O. (1976) Apramycin, a Unique Aminocyclitol Antibiotic. J. Org. Chem. 41, 2087–2092. 10.1021/jo00874a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. P.; Kirby J. E. (2016) Evaluation of Apramycin Activity Against Carbapenem-Resistant and -Susceptible Strains of Enterobacteriaceae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 86, 439–441. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Liu L.; Zhang X.; Feng Y.; Zong Z. (2017) In Vitro Activity of Neomycin, Streptomycin, Paromomycin and Apramycin Against Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Strains. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2275. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang A. D.; Smith K. P.; Eliopoulos G. M.; Berg A. H.; McCoy C.; Kirby J. E. (2017) In vitro Apramycin Activity Against Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 88, 188–191. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M.; Widlake E.; Teo J.; Huseby D. L.; Tyrrell J. M.; Polikanov Y.; Ercan O.; Petersson A.; Cao S.; Aboklaish A. F.; Rominski A.; Crich D.; Böttger E. C.; Walsh T. R.; Hughes D. E.; Hobbie S. N. (2019) In-vitro Activity of Apramycin Against Multidrug-, Carbapenem-, and Aminoglycoside-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 944–952. 10.1093/jac/dky546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2018) Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance: ENABLE Selects First Clinical Candidate, Innovative Medicines Initiative. https://www.imi.europa.eu/projects-results/project-factsheets/enable (accessed Feb 12, 2019).

- Perez-Fernandez D.; Shcherbakov D.; Matt T.; Leong N. C.; Kudyba I.; Duscha S.; Boukari H.; Patak R.; Dubbaka S. R.; Lang K.; Meyer M.; Akbergenov R.; Freihofer P.; Vaddi S.; Thommes P.; Ramakrishnan V.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C. (2014) 4′-O-Substitutions Determine Aminoglycoside Selectivity at the Drug Target Level. Nat. Commun. 5, 3112. 10.1038/ncomms4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duscha S.; Boukari H.; Shcherbakov D.; Salian S.; Silva S.; Kendall A.; Kato T.; Akbergenov R.; Perez-Fernandez D.; Bernet B.; Vaddi S.; Thommes P.; Schacht J.; Crich D.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C. (2014) Identification and Evaluation of Improved 4′-O-(Alkyl) 4,5-Disubstituted 2-Deoxystreptamines as Next Generation Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. mBio 5, e01827–14. 10.1128/mBio.01827-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T.; Chen W.; Juskeviciene R.; Teo Y.; Shcherbakov D.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C.; Crich D. (2015) Influence of 4′-O-Glycoside Constitution and Configuration on Ribosomal Selectivity of Paromomycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7706–7717. 10.1021/jacs.5b02248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sati G. C.; Shcherbakov D.; Hobbie S.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C.; Crich D. (2017) N6′, N6‴, and O4′-Modifications to Neomycin Affect Ribosomal Selectivity Without Compromising Antibacterial Activity. ACS Infect. Dis. 3, 368–376. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T.; Sati G. C.; Kondasinghe N.; Pirrone M. G.; Kato T.; Waduge P.; Kumar H. S.; Cortes Sanchon A.; Dobosz-Bartoszek M.; Shcherbakov D.; Juhas M.; Hobbie S. N.; Schrepfer T.; Chow C. S.; Polikanov Y. S.; Schacht J.; Vasella A.; Böttger E. C.; Crich D. (2019) Design, Multigram Synthesis, and in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Propylamycin: A Semisynthetic 4,5-Deoxystreptamine Class Aminoglycoside for the Treatment of Drug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Other Gram-Negative Pathogens. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 5051–5061. 10.1021/jacs.9b01693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttger E. C.; Schacht J. (2013) The Mitochondrion: A Perpetrator of Acquired Hearing Loss. Hear. Res. 303, 12–19. 10.1016/j.heares.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huth M. E.; Ricci A. J.; Cheng A. G. (2011) Mechanisms of Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity and Targets of Hair Cell Protection. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 937861. 10.1155/2011/937861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M.; Karasawa T.; Steyger P. S. (2017) Aminoglycoside-Induced Cochleotoxicity: A Review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11, 308. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassinelli G.; Franceschi G.; Di Colo G.; Arcamone F. (1978) Semisynthetic Aminoglycoside Antibiotics 1. New Reactions of Paromomycin and Synthesis of its 2′-N-Ethyl Derivative. J. Antibiot. 31, 378–381. 10.7164/antibiotics.31.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassinelli G.; Julita P.; Arcamone F. (1978) Semisynthetic Aminoglycoside Antibiotics II. Synthesis of Analogues of Paromomycin Modified in the Glucosamine Moiety. J. Antibiot. 31, 382–384. 10.7164/antibiotics.31.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roestamadji J.; Graspsas I.; Mobashery S. (1995) Loss of Individual Electrostatic Interactions between Aminoglycoside Antibiotics and Resistance Enzymes as an Effective Means to Overcoming Bacterial Drug Resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 11060–11069. 10.1021/ja00150a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier R. J.; Hay R. W.; Vethaviyasar N. (1973) A Potentially Versatile Synthesis of Glycosides. Carbohydr. Res. 27, 55–61. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)82424-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg W. A.; Priestley E. S.; Sears P. S.; Alper P. B.; Rosenbohm C.; Hendrix M.; Hung S.-C.; Wong C.-H. (1999) Design and Synthesis of New Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Containing Neamine as an Optimal Core Structure: Correlation of Antibiotic Activity with in Vitro Inhibition of Translation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 6527–6541. 10.1021/ja9910356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S.-R.; Lai Y. H.; Chen J.-H.; Liu C.-Y.; Mong K.-K. T. (2011) Dimethylformamide: An Unusual Glycosylation Modulator. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 50, 7315–7320. 10.1002/anie.201100076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa T.; Kobayashi S.; Ito Y.; Yasuda N. (1968) Radical Reaction of Isocyanide with Organotin Hydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 4182–4182. 10.1021/ja01017a061.5655885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R.; Bringmann G.; Lamotte G.; Motherwell W. B.; Hay Motherwell R. S.; Porter A. E. A. (1980) Reactions of Relevance to the Chemistry of the Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Part 14. A Useful Radical-Deamination Reaction. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1, 2657–2664. 10.1039/p19800002657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D. H. R.; Bringmann G.; Motherwell W. B. (1980) Reactions of Relevance to the Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Part 15. The Selective Modification of Neamine by Radical-Induced Deamination. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1, 2665–2669. 10.1039/p19800002665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestri M.; Chatgilialoglu C.; Clark K. B.; Griller D.; Giese B.; Kopping B. (1991) Tris(trimethylsily1)silane as a Radical-Based Reducing Agent in Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 56, 678–683. 10.1021/jo00002a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard-Borger E. D.; Stick R. V. (2007) An Efficient, Inexpensive, and Shelf-Stable Diazotransfer Reagent: Imidazole-1-sulfonyl Azide Hydrochloride. Org. Lett. 9, 3797–3800. 10.1021/ol701581g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H.; Liu R.; Li D.; Liu Y.; Yuan H.; Guo W.; Zhou L.; Cao X.; Tian H.; Shen J.; Wang P. G. (2013) A Safe and Facile Route to Imidazole-1-sulfonyl Azide as a Diazotransfer Reagent. Org. Lett. 15, 18–21. 10.1021/ol3028708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer N.; Goddard-Borger E. D.; Greiner R.; Klapotke T. M.; Skelton B. W.; Stierstorfer J. (2012) Senstivities of Some Imidazole-1-sulfonyl Azide Salts. J. Org. Chem. 77, 1760–1764. 10.1021/jo202264r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter G. T.; Jayson G. C.; Miller G. J.; Gardiner J. M. (2016) An Updated Synthesis of the Diazo-Transfer Reagent Imidazole-1-sulfonyl Azide Hydrogen Sulfate. J. Org. Chem. 81, 3443–3446. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn D. L.; Zelle R. E.; Grieco P. A. (1983) A Mild Two-Step Method for the Hydolysis/Methanolysis of Secondary Amides and Lactams. J. Org. Chem. 48, 2424–2426. 10.1021/jo00162a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak R.; Perez-Fernandez D.; Nandurdikar R.; Kalapala S. K.; Böttger E. C.; Vasella A. (2008) Synthesis and Evaluation of Paromomycin Derivatives Modified at C(4′). Helv. Chim. Acta 91, 1533–1552. 10.1002/hlca.200890167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J.; Li T.; Bartz U.; Gütschow M. (2016) Cathepsin B Inhibitors: Combining Dipeptide Nitriles with an Occluding Loop Recognition Element by Click Chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7, 211–216. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPlanche L. A.; Rogers M. T. (1964) cis and trans Configurations of the Peptide Bond in N-Monosubstituted Amides by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 86, 337–341. 10.1021/ja01057a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler P.; Bernet B.; Vasella A. (1996) A 1H-NMR Spectroscopic Investigation of the Conformation of the Acetamido Group in Some Derivatives of N-Acetyl-D-allosamine and D-Glucosamine. Helv. Chim. Acta 79, 269–287. 10.1002/hlca.19960790127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Zhang W.; Carmichael I.; Serianni A. S. (2010) Amide Cis-Trans Isomerization in Aqueous Solutions of Methyl N-Formyl-D-glucosaminides and Methyl N-Acetyl-D-glucosaminides: Chemical Equilibria and Exchange Kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4641–4652. 10.1021/ja9086787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito T.; Nakagawa S.; Narita Y.; Kawaguchi H. (1976) Chemical Modification of Sorbistin. N-Acyl Analogs of Sorbistin. J. Antibiot. 29, 1286–1296. 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanessian S.; Takamoto T.; Masse R. (1975) Oxidative Degradations Leading to Novel Biochemical Probes and Synthetic Intermediates. J. Antibiot. 28, 835–836. 10.7164/antibiotics.28.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak R.; Böttger E. C.; Vasella A. (2005) Design and Synthesis of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics to Selectively Target 16S Ribosomal RNA Position 1408. Helv. Chim. Acta 88, 2967–2984. 10.1002/hlca.200590240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami H.; Ikeda S.; Kitahara K.; Nakajima M. (1977) Total Synthesis of Ribostamycin. Agric. Biol. Chem. 41, 1689–1694. 10.1271/bbb1961.41.1689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A. P.; Clemons W. M.; Brodersen D. E.; Morgan-Warren R. J.; Wimberly B. T.; Ramakrishnan V. (2000) Functional Insights from the Structure of the 30S Ribosomal Subunit and its Interactions with Antibiotics. Nature 407, 340–348. 10.1038/35030019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie S. N.; Kalapala S. K.; Akshay S.; Bruell C.; Schmidt S.; Dabow S.; Vasella A.; Sander P.; Böttger E. C. (2007) Engineering the rRNA Decoding Site of Eukaryotic Cytosolic Ribosomes in Bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 6086–6093. 10.1093/nar/gkm658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie S. N.; Akshay S.; Kalapala S. K.; Bruell C.; Shcherbakov D.; Böttger E. C. (2008) Genetic Analysis of Interactions with Eukaryotic rRNA Identify the Mitoribosome as Target in Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 20888–20893. 10.1073/pnas.0811258106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie S. N.; Bruell C. M.; Akshay S.; Kalapala S. K.; Shcherbakov D.; Böttger E. C. (2008) Mitochondrial Deafness Alleles Confer Misreading of the Genetic Code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 3244–3249. 10.1073/pnas.0707265105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie S. N.; Kaiser M.; Schmidt S.; Shcherbakov D.; Janusic T.; Brun R.; Böttger E. C. (2011) Genetic Reconstruction of Protozoan rRNA Decoding Sites Provides a Rationale for Paromomycin Activity against Leishmania and Trypanosoma. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 5, e1161 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y.; Guan M.-X. (2009) Interaction of Aminoglycosides with Human Mitochondrial 12S rRNA Carrying the Deafness-Associated Mutation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 4612–4618. 10.1128/AAC.00965-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezant T. R.; Agapian J. V.; Bohlman M. C.; Bu X.; Öztas S.; Qiu W.-Q.; Arnos K. S.; Cortopassi G. A.; Jaber L.; Rotter J. I.; Shohat M.; Fischel-Ghodsian N. (1993) Mitochondrial Ribosomal RNA Mutation Associated with Both Antibiotic-Induced and Non-Syndromic Deafness. Nat. Genet. 4, 289–294. 10.1038/ng0793-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadanier J.; Martin J. R.; Johnson P.; Goldstein A. W.; Hallas R. (1980) 2′-N-Acylfortimicins and 2′-N-Alkylfortimicins via the Isofortimicin Rearrangement. Carbohydr. Res. 85, 61–71. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)84564-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satoi S.; Awata M.; Muto N.; Hayashi M.; Sagai H.; Otani M. (1983) A New Aminoglycoside Antibiotic G-367 S1, 2′-N-Formylsisomicin. Fermentation, Isolation and Characterization. J. Antibiot. 36, 1–5. 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C.-H.; Hendrix M.; Manning D. D.; Rosenbohm C.; Greenberg A. A. (1998) A Library Approach to the Discovery of Small Molecules That Recognize RNA: Use of a 1,3-Hydroxyamine Motif as Core. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 8319–8327. 10.1021/ja980826p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nessar R.; Cambau E.; Reyrat J. M.; Murray A.; Gicquel B. (2012) Mycobacterium abscessus: A New Antibiotic Nightmare. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 810–818. 10.1093/jac/dkr578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer F. P.; Bruderer V. L.; Castelberg C.; Ritter C.; Scherbakov D.; Bloemberg G. V.; Böttger E. C. (2015) Aminoglycoside-modifying Enzymes Determine the Innate Susceptibility to Aminoglycoside Antibiotics in Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1412–1419. 10.1093/jac/dku550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- François B.; Russell R. J. M.; Murray J. B.; Aboul-Ela F.; Masquid B.; Vicens Q.; Westhof E. (2005) Crystal Structures of Complexes Between Aminoglycosides and Decoding A Site Oligonucleotides: Role of the Number of Rings and Positive Charges in the Specific Binding Leading to Miscoding. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5677–5690. 10.1093/nar/gki862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M.; Pilch D. S. (2002) Thermodynamics of Aminoglycoside-rRNA Recognition: The Binding of Neomycin-Class Aminoglycosides to the A Site of 16S rRNA. Biochemistry 41, 7695–7706. 10.1021/bi020130f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M.; Barbieri C. M.; Kerrigan J. E.; Pilch D. S. (2003) Coupling of Drug Protonation to the Specific Binding of Aminoglycosides to the A Site of 16 S rRNA: Elucidation of the Number of Drug Amino Groups Involved and their Identities. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 1373–1387. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman M. R.; Pulk A.; Zhou Z.; Altman R. B.; Zinder J. C.; Green K. D.; Garneau-Tsodikova S.; Doudna Cate J. H.; Blanchard S. C. (2015) Chemically Related 4,5-Linked Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Drive Subunit Rotation in Opposite Directions. Nat. Commun. 6, 7896. 10.1038/ncomms8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacas T.; Corzana F.; Jiménez-Osés G.; González C.; Gómez A. M.; Bastida A.; Revuelta J.; Asensio J. L. (2010) Role of Aromatic Rings in the Molecular Recognition of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics: Implications for Drug Design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12074–12090. 10.1021/ja1046439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanessian S.; Saavedra O. M.; Vilchis-Reyes M. A.; Maianti J. P.; Kanazawa H.; Dozzo P.; Matias R. D.; Serio A.; Kondo J. (2014) Synthesis, Broad Spectrum Antibacterial Activity, and X-ray Co-crystal Structure of the Decoding Bacterial Ribosomal A-Site with 4′-Deoxy-4′-Fluoro Neomycin Analogs. Chem. Sci. 5, 4621–4632. 10.1039/C4SC01626B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T.; Westhof E. (1999) Docking of Cationic Antibiotics to Negatively Charged Pockets in RNA Folds. J. Med. Chem. 42, 1250–1261. 10.1021/jm981108g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzana F.; Cuesta I.; Freire F.; Revuelta J.; Torrado M.; Bastida A.; Jiménez-Barbero J.; Asensio J. L. (2007) The Pattern of Distribution of Amino Groups Modulates the Structure and Dynamics of Natural Aminoglycosides: Implications for RNA Recognition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2849–2865. 10.1021/ja066348x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourmy D.; Recht M. I.; Blanchard S. C.; Puglisi J. D. (1996) Structure of the A Site of Escherichia coli 16S Ribosomal RNA Complexed with an Aminoglycoside Antibiotic. Science 274, 1367–1371. 10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Zhao Q.; Blount K. F.; Han Q.; Tor Y.; Hermann T. (2005) Moelcular Recognition of RNA by Neomycin and a Restricted Neomycin Derivative. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 44, 5329–5334. 10.1002/anie.200500903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount K. F.; Zhao F.; Hermann T.; Tor Y. (2005) Conformational Constraint as a Means for Understanding RNA-Aminoglycoside Specificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 9818–9829. 10.1021/ja050918w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asensio J. L.; Hidalgo A.; Bastida A.; Torrado M.; Corzana F.; Chiara J. L.; Garcia-Junceda E.; Cañada J.; Jiménez-Barbero J. (2005) A Simple Structural-Based Approach to Prevent Aminoglycoside Inactivation by Bacterial Defense Proteins. Conformational Restriction Provides Effective Protection against Neomycin-B Nucleotidylation by ANT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8278–8279. 10.1021/ja051722z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastida A.; Hidalgo A.; Chiara J. L.; Torrado M.; Corzana F.; Pérez-Cañadillas J. M.; Groves P.; Garcia-Junceda E.; Gonzalez C.; Jimenez-Barbero J.; Asensio J. L. (2006) Exploring the Use of Conformationally Locked Aminoglycosides as a New Strategy to Overcome Bacterial Resistance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 100–116. 10.1021/ja0543144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revuelta J.; Vacas T.; Bastida A.; Asensio J. L. (2010) Structure-Based Design of Highly Crowded Ribostamycin/Kananmycin Hybrids as a New Family of Antibiotics. Chem. - Eur. J. 16, 2986–2991. 10.1002/chem.200903003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog I. M.; Louzoun Zada S.; Fridman M. (2016) Effects of 5-O-Ribosylation of Aminoglycosides on Antimicrobial Activity and Selective Perturbation of Bacterial Translation. J. Med. Chem. 59, 8008–8018. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asako T.; Yoshioka K.; Mabuchi H.; Hiraga K. (1978) Chemical Transformation of 3′-Chloro-3′-deoxyaminoglycosides into New Cyclic Pseudo-trisaccharides. Heterocycles 11, 197–2002. 10.3987/S(N)-1978-01-0197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler M.; Schweizer E.; Hoffmann-Roder A.; Benini F.; Martin R. E.; Jaeschke G.; Wagner B.; Fischer H.; Bendels S.; Zimmerli D.; Schneider J.; Diederich F.; Kansy M.; Muller K. (2007) Predicting and Tuning Physicochemical Properties in Lead Optimization: Amine Basicities. ChemMedChem 2, 1100–1115. 10.1002/cmdc.200700059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri C. M.; Kaul M.; Bozza-Hingos M.; Zhao F.; Tor Y.; Hermann T.; Pilch D. S. (2007) Defining the Molecular Forces That Determine the Impact of Neomycin on Bacterial Protein Synthesis: Importance of the 2-Amino Functionality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1760–1769. 10.1128/AAC.01267-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.