Abstract

The co-stimulatory CD40-CD40L dyad plays a central role in fine-tuning immune reactions, including obesity-induced inflammation. Genetic ablation of CD40L reduced adipose tissue inflammation, while absence of CD40 resulted in aggravated metabolic dysfunction in mice. During obesity, CD40 expressing CD11c+ dendritic cells (DC) and macrophages accumulate in adipose tissue and liver. We investigated the role of CD40+CD11c+ cells in the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). DC-CD40-ko mice (CD40fl/flCD11ccre) mice were subjected to obesity or NASH. Obesity and insulin resistance were induced by feeding mice a 54% high fat diet (HFD). NASH was induced by feeding mice a diet containing 40% fat, 20% fructose and 2% cholesterol. CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed a HFD displayed increased weight gain, increased adipocyte size, and worsened insulin resistance. Moreover, CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice had higher plasma and hepatic cholesterol levels and developed profound liver steatosis. Overall, regulatory T cell numbers were decreased in these mice. In NASH, absence of CD40 on CD11c+ cells slightly decreased liver inflammation but did not affect liver lipid accumulation. Our experiments suggest that CD40 expressing CD11c+ cells can act as a double-edged sword: CD40 expressing CD11c+ cells contribute to liver inflammation during NASH but are protective against the metabolic syndrome via induction of regulatory T cells.

Subject terms: Obesity, Inflammatory diseases, Immunological disorders

Introduction

Obesity is a major risk factor for a variety of diseases including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)1. Obesity is defined as the abnormal accumulation of body fat to the extent that it presents a negative effect on health. These days, 13% of the adult population and 7% of the children worldwide are obese1. Obesity results in a state of systemic, low-grade inflammation caused by immune cell infiltration and activation in adipose tissue and liver2,3. Activation of macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer cells, T cells, B cells and adipocytes in the adipose tissue results in cytokine and adipokine release which can lead to obesity-associated metabolic dysregulation, characterized by insulin resistance and dyslipidemia4,5.

CD40 is a co-stimulatory molecule that upon binding to CD40L regulates inflammation by activating or suppressing immune cells6,7. Deficiency of CD40L in diet-induced obesity ameliorates inflammation of the adipose tissue and reduces insulin resistance and liver steatosis8,9. In contrast, genetic deficiency of CD40 in mice fed a high fat diet resulted in worsened insulin resistance and increased adipose tissue inflammation compared to wild-type mice10–13. An explanation for the different metabolic phenotypes in the CD40L and CD40 deficient mice can be sought in the cell type specific functions of this co-stimulatory molecule. CD40 is expressed by a variety of cell types that play a role in obesity and metabolic dysfunction including monocytes, macrophages, DCs, B cells, T cells, endothelial cells14 and adipocytes15.

The integrin CD11c is a DC surface marker, but is also present on B, T and NK cells and subsets of monocytes and macrophages16. Increased numbers of CD11c+ cells are found in the liver of mice under obese conditions17, and liver inflammation contributes to the progression from NAFLD (defined as the presence of ≥5% of hepatic steatosis) to NASH18. In humans, adipose tissue CD11c expression is discriminative for crown-like-structure macrophages and the presence of CD11c+ macrophages correlates with markers of insulin resistance19. CD40 expression was detected on CD11c+ adipose tissue cells in obese mice while lowly expressed in lean adipose tissue20.

We here investigate the contribution of CD40 on CD11c+ cells in the regulation of diet induced obesity and NASH using CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice. We found that CD40 expressing CD11c+ cells contribute to diet-induced-obesity (DIO) and NASH in opposing ways. In diet induced obesity CD40 expressing CD11c+ cells play a crucial role in protection against obesity-induced ectopic lipid storage and metabolic dysfunction, most likely via induction of regulatory T cells. During NASH, CD40 on CD11c+ cells contributes to liver inflammation.

Results

CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice have increased body weight gain and excess lipid deposition compared to WT mice after high fat diet feeding

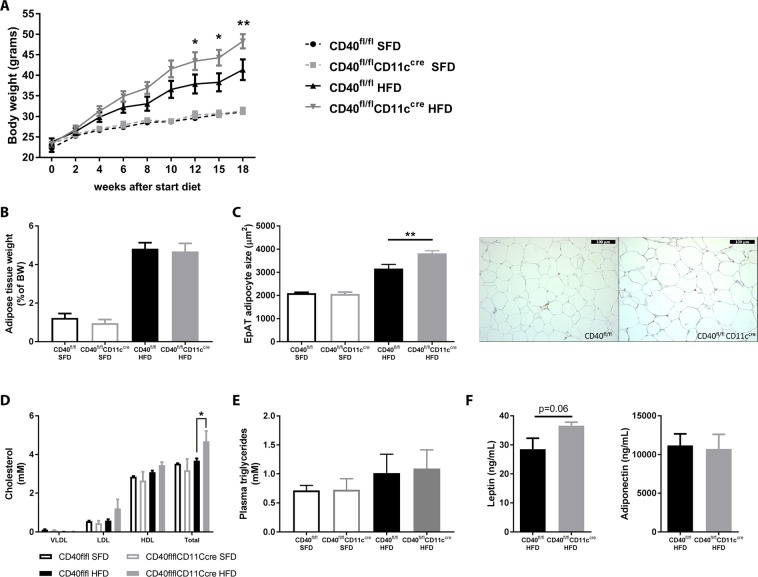

During the course of DIO, CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice gained more weight than their wild type littermates (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.0012 at week 18, Fig. 1A). This difference was specific for HFD fed mice and was not observed in the mice fed SFD (Fig. 1A). EpAT weight did not differ between CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice (Fig. 1B). However, adipocyte size of HFD CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice was increased by 20.9% compared to WT mice (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0082, Fig. 1C) indicating excess lipid deposition. In line with these results, total cholesterol levels in plasma were significantly higher in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to WT mice on HFD (two-way ANOVA, p = 0.0476, Fig. 1D). Plasma VLDL, HDL and LDL levels did not differ significantly, but the increase in HDL and LDL levels explain the increase in total cholesterol in the HFD CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (Fig. 1D). Plasma triglyceride levels did not differ (Fig. 1E). Leptin concentrations in the plasma slightly increased in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre group compared to the WT group on the HFD (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0601, Fig. 1F). Adiponectin levels did not differ between the groups (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice on HFD are more obese than WT mice. (A) Body weight gain during 18 weeks of standard (SFD) or high fat diet (HFD) feeding. (B) epidydimal adipose tissue (EpAT) tissue weight after 18 weeks of diet. (C) EpAT adipocyte size after 18 weeks of diet and representative HE pictures of EpAT of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice and WT mice fed an HFD (scale bar is 100 µm). (D) Total plasma cholesterol and lipid fractions. (E) Plasma triglycerides. (F) Plasma leptin and adiponectin levels. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 for comparison between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed the same diet. n = 7/group for SFD, and n = 8/group for HFD.

CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice display slightly aggravated insulin resistance

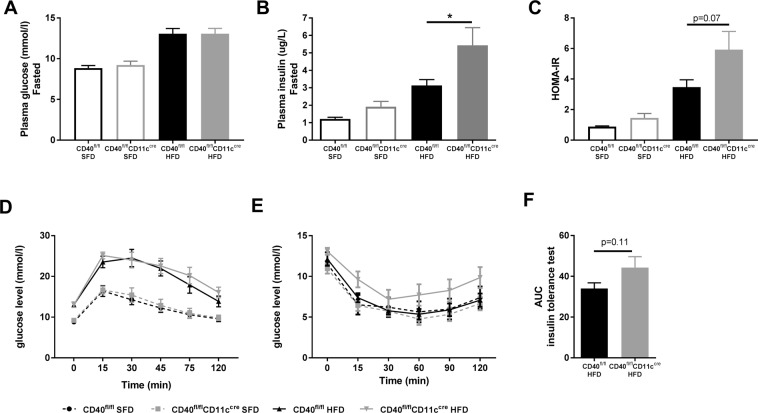

Saturation of adipocytes can lead to excess lipid storage in other metabolic organs such as liver and muscle21, which can result in insulin resistance and abnormal production of insulin4,22. Indeed, HFD feeding increased fasted levels of glucose compared to levels of SFD mice, but no differences between the CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice were observed (Fig. 2A). However, fasted plasma insulin levels of HFD CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice had increased 1.7-fold compared to WT mice (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0476, Fig. 2B), indicating compensation of dysfunctional insulin signaling and worsened insulin resistance in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice. The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) shows a tendency towards an increased score in the HFD CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice, implying that CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice display aggravated insulin resistance when fed HFD (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0764, Fig. 2C). Glucose sensitivity was impaired after HFD feeding, but there were no differences between CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice when fed a similar diet (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the increase in fasting insulin levels, a trend towards worsened insulin resistance as measured via an ITT was observed in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed HFD compared to WT mice (area under the curve of 34.0 (mean) ± 7.9 (SD) in HFD WT mice vs 44.3 ± 15.2 in HFD CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice, unpaired t-test, p = 0.1113, Fig. 2E,F). These data suggest that the excess (ectopic) lipid accumulation in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice results in slightly worsened insulin resistance in this model.

Figure 2.

CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice display slightly aggravated insulin resistance. (A) Plasma glucose levels after 6 hours of fasting. (B) Plasma insulin levels after 6 hours of fasting. (C) HOMA-IR. (D) Plasma glucose levels measured during the glucose tolerance test (GTT). (E) Plasma glucose levels measured during the insulin tolerance test (ITT). (F) Area under the curve (AUC) insulin tolerance test. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparison between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed the same diet. n = 7/group for SFD, and n = 8/group for HFD.

Adipose tissue inflammation is not affected in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice

FACS analysis of the adipose tissue revealed that leukocyte infiltration of the AT in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice did not significantly differ from WT mice when fed a similar diet (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Histological stainings of the EpAT with CD68 for macrophages and CD3 for T cells confirm these findings (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Further analysis of myeloid and lymphoid subsets also showed no significant differences (Supplemental Fig. 1C,D). This was confirmed by the mRNA transcription profile of inflammatory mediators in EpAT (Supplemental Fig. 2A,B), revealing that absence of CD40 on CD11c+ cells does not affect AT inflammation.

Loss of CD11c+CD40 causes the development of liver steatosis during diet-induced obesity

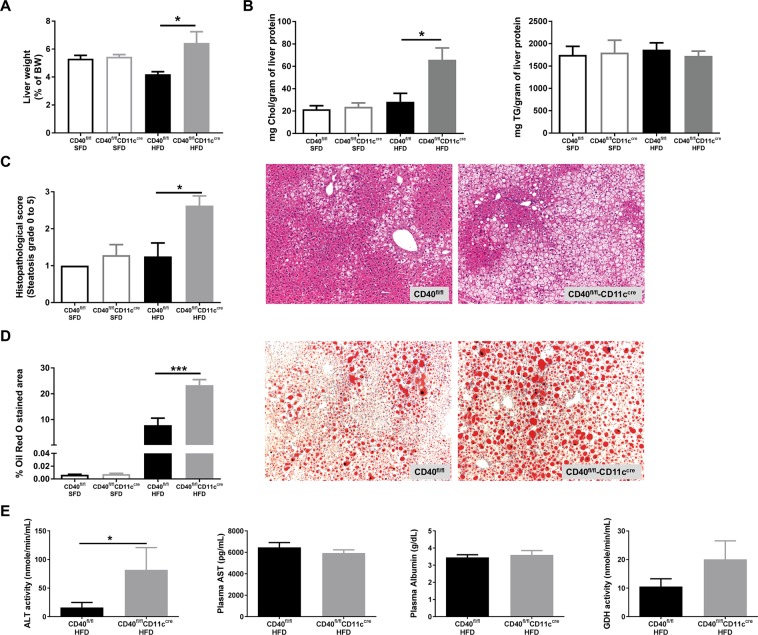

As decreased storage capacity of the adipose tissue leads to ectopic lipid deposition, we next assessed the severity of obesity-induced hepatic steatosis. In CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice, the percentage liver weight compared to body weight was significantly increased (6.4 ± 2.3% of BW) compared to WT mice (4.2 ± 0.5% of BW) (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0162, Fig. 3A). Liver total cholesterol levels were highly increased in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to WT mice on the HFD (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0118, Fig. 3B) while triglyceride content was not affected (Fig. 3B). As expected from the high liver cholesterol levels, the grade of steatosis was significantly higher in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice on a HFD compared to WT mice (median steatosis score of grade 3 in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to grade 1 in WT mice, Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.0177, Fig. 3C). The increased steatosis was confirmed by ORO staining showing significantly increased lipid accumulation in the liver (Fig. 3D). Quantification of the ORO staining indicated that 7.8 ± 7.7% of the liver of WT mice is steatotic vs 23.3 ± 6.1% of the liver of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (mean ± SD), unpaired t-test, p = 0.0005, Fig. 3D). Excess free cholesterol in the liver can accumulate in the hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells where it can induce cellular toxicity or proinflammatory and profibrotic effects23. In order to examine whether these mice suffered from liver damage due to excessive storage of fat in the liver, we measured the presence of liver enzymes and damage related proteins in the plasma that could indicate hepatocellular injury24. Significantly increased levels of plasma ALT were found in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.0207, Fig. 3E), while AST and albumin levels did not differ from levels found in WT mice on HFD (Fig. 3E). Liver diseases that result from hepatocyte necrosis, and not from inflammation, result in elevated serum GDH levels25. GDH activity in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice was higher compared to the WT mice, although not significant (unpaired t-test, p = 0.1967, Fig. 3E). Sirius Red staining of the liver shows that there is no fibrosis present after 18 weeks of HFD (data not shown), but the increased levels of ALT and GDH in the plasma of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice indicate that the liver steatosis had caused damage to the hepatocytes of these mice.

Figure 3.

Increased liver steatosis characterizes CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice after 18 weeks of HFD. (A) Liver weight (grams). (B) Total cholesterol/gram protein and TG/gram protein of liver. (C) Histopathological scoring of liver steatosis and representative H&E staining of liver. (D) Quantification of liver Oil-red-O (ORO) staining and representative pictures. (E) Plasma liver enzymes: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, albumin levels and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) activity. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for comparison between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed the same diet. n = 7/group for SFD, and n = 8/group for HFD.

Regulatory T cells numbers are decreased in the liver of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice with DIO

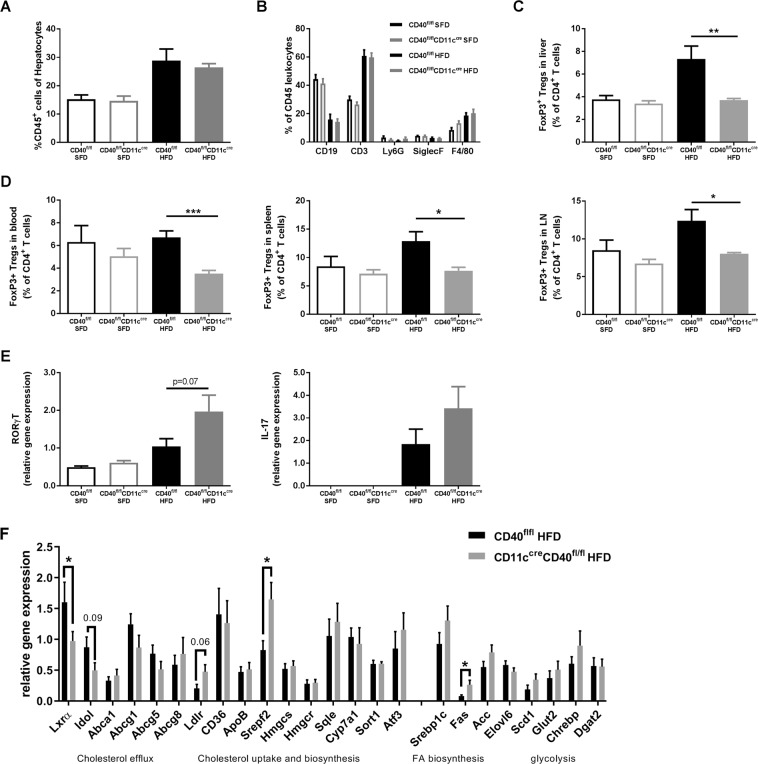

Liver inflammation was investigated by histopathological quantification of the CD45 staining and showed no differences in number of leukocytes present between the groups that received a similar diet (Fig. 4A). Liver leukocyte subsets were further analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B,C). The percentage of CD3+ T cells in the liver was increased in both the HFD groups compared to SFD mice (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) was significantly lower in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice on a HFD compared to WT mice on the same diet (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0067, Fig. 4C). This decrease in Tregs was also observed in blood, spleen and LN of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (Fig. 4D). This difference in Treg population was only observed after HFD feeding and was not found in the SFD mice (Fig. 4D). Livers of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice on a HFD showed a slightly increased expression of RORγt (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0725, Fig. 4E) and IL17 compared to WT mice mRNA (Fig. 4E), indicating increased presence of Th17 cells in the liver of HFD fed CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice.

Figure 4.

Reduced numbers of regulatory T cells (Tregs) were found in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice after 18 weeks of HFD. (A) Histological quantification of CD45 staining of liver. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of leukocyte subsets in the liver. (C) % of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs in liver. (D) Systemic % of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs measured in blood, spleen, and lymph nodes (LN). (E) liver mRNA expression of RORγT and IL-17. (F) mRNA expression of cholesterol metabolism genes in the liver of HFD fed CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for comparison between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed the same diet. n = 7/group for SFD, and n = 8/group for HFD.

Liver cholesterol metabolism gene expression analysis

Absence of CD40 on CD11c+ cells caused increased cholesterol levels in liver and blood in obesity. Gene expression analysis of liver mRNA show decreased expression of genes involved in cholesterol secretion (LXRα (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0123) and Idol (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0923, Fig. 4F)), and increased expression in genes related to cholesterol uptake and biosynthesis (LDLr (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0600), and SREBP2 (unpaired t-test, p = 0.0195), Fig. 4F) in HFD fed CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to WT mice suggesting and imbalance in liver cholesterol metabolism in these mice.

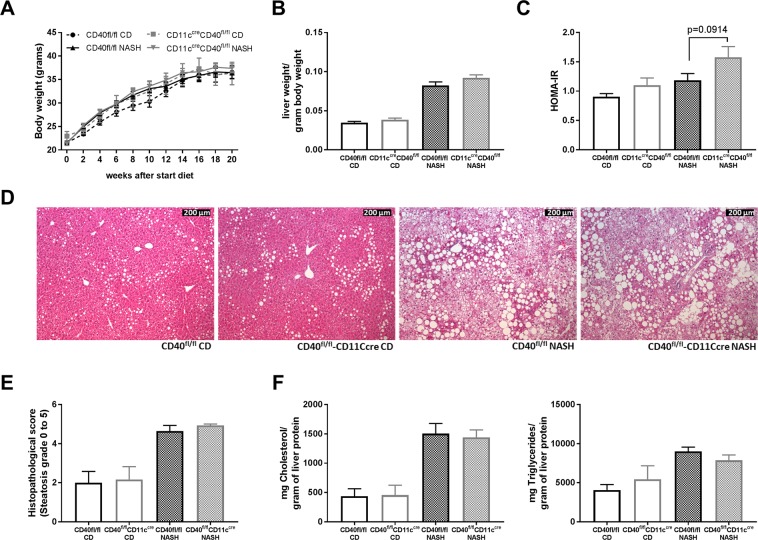

The degree of hepatosteatosis is not different in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to WT mice on a NASH inducing diet

As the degree of hepatic inflammation in DIO is rather low, we decided to further investigate the (anti)inflammatory potential of CD11c+CD40+ cells in a more inflammatory model of hepatosteatosis, and we induced NASH in both genotypes. The NASH inducing diet did not affect body weight compared to the control diet and there were no differences between CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice and WT mice that were fed a similar diet (Fig. 5A). Increased liver weights were observed after feeding the NASH diet, but there was no difference between CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice and WT mice (Fig. 5B). HOMA-IR was slightly increased in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed a NASH diet (score 1.18 ± 0.42 in WT vs 1.58 ± 0.71 in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice, unpaired t-test, p = 0.0914, Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the degree of steatosis was similar in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice and WT mice on the NASH diet (Fig. 5D,E, representative HE pictures). Liver Cholesterol and TG levels were similar in the different groups on the same diet (Fig. 5F). Fasted plasma glucose measured after 20 weeks of diet was not different between the groups (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Fasted plasma insulin levels were slightly higher in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice on the NASH diet compared to WT mice (0.23 ug/mL vs 0.31 ug/mL, unpaired t-test, p = 0.0667, Supplemental Fig. 3B). Glucose and insulin sensitivity were measured after 12 weeks of diet and were not affected in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice and WT mice on the NASH diet as shown by no differences between the groups during the GTT and ITT (Supplemental Fig. 3C,D). Plasma cholesterol and TG did not significantly differ between the groups on the same diet (Supplemental Fig. 3E,F).

Figure 5.

Effect of NASH and CD diet feeding in CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice. (A) Body weight. (B) Liver weight per gram body weight. (C) HOMA-IR. (D) Representative pictures H&E staining liver (scale bar is 200 um). (E) Mean histopathological steatosis degree. (F) Cholesterol and Triglyceride content liver. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. n = 6/group for control diet (CD), and n = 15/group for NASH diet.

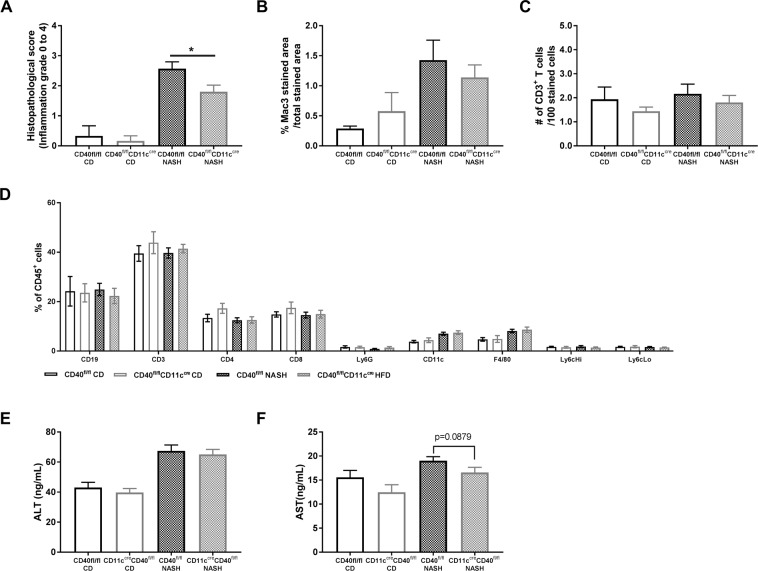

CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice have reduced liver inflammation during NASH compared to WT mice

Although no differences could be observed in hepatosteastosis after the NASH diet, the degree of hepatic inflammation had decreased in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice compared to WT mice (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.0301, Fig. 6A). Quantification of liver Mac-3 staining and CD3 staining shows that the number of macrophages and T cells in the liver of CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice are not significant different between the groups, but are both slightly decreased compared to WT mice on a NASH diet, accounting for the total decrease in inflammation (Fig. 6B,C). FACS data of the liver shows no difference in leukocyte composition (Fig. 6D). ALT levels had increased after feeding the NASH inducing diet but did not differ between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (Fig. 6E), whereas AST levels were lower in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice (19.02 ng/mL vs 16.57 ng/mL, unpaired t-test, p = 0.0879, Fig. 6F). Furthermore, systemic inflammation was not different between the groups on the same diet (blood, spleen and lymph node leukocyte subsets, Supplemental Fig. 4A–C).

Figure 6.

Liver inflammation is lower in CD40fl/flCD11ccre compared to WT mice on a NASH inducing diet. (A) Mean histopathological inflammation grade. (B) quantification of Mac3 staining in the liver (C) quantification of CD3 staining in the liver. (D) Liver leukocyte subsets analyzed by FACS. (E) plasma ALT levels. (F) plasma AST levels. Data is represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 for comparison between WT and CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed a similar diet. n = 6/group for CD, and n = 15/group for NASH diet.

Discussion

In line with the worsened metabolic phenotype observed in CD40−/− mice on a high fat diet10–13, we here show that HFD fed CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice become more obese than WT mice, develop hyperinsulinemia and have an increased lipid uptake in adipose tissue and liver, resulting in severe hepatic steatosis. In contrast to the phenotype observed in total body CD40-deficient mice, CD40-deficiency in CD11c+ cells did not result in a profound increase in pro-inflammatory mediators in lymphoid organs, adipose tissue or liver. However, upon high fat diet feeding CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice did show a reduction in the number of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in blood, adipose tissue, liver and lymphoid organs.

Tregs function as a control mechanism that can affect the behavior of other T cell populations and suppress overactive immune responses26. CD40-deficient mice are known to have a reduced amount of Tregs in peripheral blood, spleen and the thymus27,28. Especially B cell CD40 is involved in survival of Tregs in the thymus29, whereas deficiency of CD11c-CD40 resulted in only a minor decrease in natural Tregs in the thymus30. In our experiment, we could not observe decreases in Treg levels in blood, lymphoid organs and tissues in CD40fl/flCD11ccre upon SFD, but we did see a HFD induced reduction of Tregs in lymphoid organs, and especially in the liver. This suggests that CD40+CD11c+ cells are particularly involved in the reactive generation of Tregs during chronic inflammatory conditions31, and can be generated through homeostatic proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells32.

Although we did not observe signs of enhanced inflammation, the decrease in Tregs was surprisingly accompanied by an increase in systemic and hepatic cholesterol levels in CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice fed a HFD. Consistent with our findings, depleting FoxP3+ Tregs in a mouse model for atherosclerosis resulted in increased plasma cholesterol levels but did not induce inflammation in the liver or the atherosclerotic plaques33. In this study Treg depletion reduced protein expression of the VLDL binding protein sortilin-1 in the liver increasing lipoprotein catabolism activity in the plasma, which results in accumulation of VLDL and CM lipoproteins in the circulation33. In our experiment we observed upregulated expression of the LDLr, SREBP2 and FAS gene suggesting that the liver takes up more cholesterol from the blood and has increased cholesterol biosynthesis34, while reduced gene expression of LXRα (and Idol) and its target genes indicate decreased excretion of cholesterol from hepatocytes35. Together this could result in the accumulation of cholesterol in the liver. Another contributor to the increased hepatosteatosis in our DIO model could be the increased leptin levels in the CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice. The adipose tissue hormone leptin negatively affects Treg proliferation36,37. Increased leptin levels contribute to the progression from NAFLD to NASH via activation of macrophage and Kupffer cells and increased oxidative stress38.

Interestingly, mice deficient in the co-stimulatory molecule CD80/86 (B7.1/B7.7) showed increased liver steatosis when fed a HFD, a similar phenotype as observed in our CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice39. CD80/CD86 is required for proper Treg development and the phenotype observed in these mice was also attributed to the reduction of Treg numbers in B7.1/B7.7 double knock out mice39. Together with our results these findings underline the important role for Tregs in obesity associated liver disease and indicate that manipulation of co-stimulatory molecule signaling to increase Treg numbers is therapeutically interesting for the prevention of hepatosteatosis and eventually NASH.

Tregs have been described to play an important role in hepatic steatosis related diseases, particularly in NAFLD and NASH. NAFLD and NASH are important health problems related to obesity and NAFLD affects 25% of the global adult population, of which 59% of the patients exhibits NASH18. NAFLD is defined by the presence of ≥5% of hepatic steatosis, and when hepatocyte damage develops, disease progresses into NASH, characterized by hepatic fibrosis18. Hepatic steatosis and NASH are associated with reduction of hepatic Treg numbers in both human and mouse40,41. Depletion of Tregs is caused by increased oxidative stress in fatty livers inducing Treg apoptosis and impairs suppression of inflammatory responses40. Activation of inflammatory signaling through the TNF‐α pathway contributes to the progression from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis40. Interestingly, pharmacological upregulation of Treg numbers, using 3, 3′-diindolylmethane (DIM), can reduce hepatic inflammation42.

However, when NASH was induced in our CD40fl/flCD11ccre mouse model, we could not observe a reduction in Tregs in liver or lymphoid organs. Moreover, absence of CD11c+CD40+ cells did not affect the degree of hepatosteatosis, which was massive (~40%) in the NASH model. These data indicate that the reduced Treg numbers observed in the DIO study were probably caused by the adipose tissue driven ectopic lipid accumulation, rather than the intrinsic effects of the liver fat during NASH. Interestingly, absence of CD11c+CD40+ cells did reduce hepatic inflammation during NASH, indicating that CD11c+CD40+ cells have a strong (lipid driven) immune-modulatory function.

In conclusion, we here show that CD40+CD11c+ cells play a crucial role in protection against obesity-induced liver steatosis via activation of regulatory T cells, thereby inducing a tolerogenic immune response that prevents hepatosteatosis.

Material and Methods

Mice

To study DC and CD11c+ macrophage-CD40 depletion in DIO and NASH CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice were generated by crossbreeding CD11c-cre transgenic mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1-1Reiz/J, purchased from Jackson Laboratory) with CD40flfl mice (CD40fl/flCD11ccre mice). CD40flfl mice were generated by custom-design at Ozgene Pty Ltd (Bentley, Australia)43. CD40flfl mice carry loxP-sites before CD40 exon2 and after CD40 exon3. Cre-mediated recombination by the CD11c-cre mice removes the loxed CD40 exons, resulting in a non-functional CD40 peptide on CD11c+ cells. The CD11c-cre recombinase is highly present on dendritic cells (~80–100%) and to a smaller extent on mature macrophages (~40–75%), monocytes (~20–40%), and on lymphocytes (B and T-cells < 20%)44. CD40flflCD11cWT (WT) littermates were used as the control group. All mice were bred and maintained at the animal facility of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam (AMC).

Study design

CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice (male, age 6–8 weeks) were fed a high fat diet (HFD; SNIFF-D12492 Energy 22% from carbohydrates, 24% from protein, and 54% from fat), or a standard fat diet (SFD; SNIFF-D12450B Energy 65% from carbohydrates, 26% from protein, and 9% from fat) for 18 weeks to study obesity and insulin resistance. Another group of CD40fl/flCD11ccre and WT mice (male, age 6–8 weeks) were fed a NASH inducing diet (NASH, D17010103 Research diets, Energy 40% from fat (mostly partially hydrogenated corn oil), 20% from fructose, and 2% from cholesterol)) or control diet (CD, D17072805, Research diets, Energy 10% from fat, 70% from carbohydrates (no fructose), and 20% from protein) for 20 weeks to study nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Mice had ad libitum access to food and water and were maintained under a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Body weight was monitored weekly. At the end of the dietary exposure period mice were euthanized, and blood samples were collected after intracardiac puncture using EDTA coated syringes. Liver, epidydimal adipose tissue (EpAT), muscle, spleen, and lymph nodes were removed after sacrifice and used for subsequent analyses. All the experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam (AMC). All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Glucose and insulin tolerance test

After 13 weeks of dietary exposure a glucose (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) were performed. For the GTT, mice were fasted for 6 hours and injected i.p. with glucose (1 mg/g body weight, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). For the ITT 4 hour fasted mice were injected i.p. with insulin (1,1mU/g body weight, Sigma-Aldrich). Blood glucose levels were measured from whole blood using a glucometer (Bayercontour, Basel, Switzerland) at times indicated in the figures.

Plasma lipids, insulin, adipokine and liver enzyme measurements

Fasting plasma insulin levels were measured in samples from 6 hour fasted mice by using an insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) following manufacturers’ protocol. Plasma leptin and adiponectin levels of the DIO mice were measured using a mouse leptin ELISA Kit (ChrystalChem) and a mouse adiponectin ELISA Kit (AssayPro). Liver enzymes were measured in plasma samples using an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity kit (DIO mice, Sigma-Aldrich) or ELISA Kit (NASH mice, Biomatik), a mouse aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ELISA Kit (Biomatik), a BCG (Bromocresol Green) albumin assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich), a glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) activity assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich), and a bilirubin assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Cholesterol and triglyceride measurements

Total cholesterol and triglyceride (TG) concentrations in plasma and liver were measured by standard enzymatic methods (CHOD-PAP and GPO-PAP; Roche Diagnostics). Frozen liver tissues were homogenized in 1 ml of SET buffer (250 mM sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris), and the samples then underwent multiple freeze-thaw cycles for cell-destruction. Individual plasma lipoprotein levels were measured by fast-performance liquid chromatography as described before45.

Flow cytometry

White blood cells from blood, spleen, lymph nodes (LN), liver and stromal vascular fraction (SVF) from EpAT were analyzed by flow cytometry. EpAT was minced into small pieces and digested with liberase (0.25 mg/mL, Roche) for 45 minutes at 37 °C. The digested samples were passed through a 70-µm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences, Breda, the Netherlands). The SVF was obtained from the resulting pellet and resuspended in FACS buffer. Erythrocytes in blood and spleen were removed by incubation with hypotonic lysis buffer (8.4 g of NH4Cl and 0.84 g of NaHCO3 per liter of distilled water). To prevent non-specific binding of antibodies to the Fc receptor, all cell suspensions were incubated with CD16/32 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) in FACS buffer (0.5% BSA, 0.01% NaN3 in PBS) before the antibodies were incubated with the indicated tissues. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (FACSCanto II, BD Biosciences, Breda, The Netherlands) and analyzed with FlowJo software version 7.6.5. (Tree star). The antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Histology

EpAT and liver tissues were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Liver steatosis was graded on 4 μm thick haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained sections. Grades were scored in a range from 0–5 were 0 = no steatosis, 1 = minimal steatosis, 2 = mild steatosis, 3 = moderate steatosis, 4 = severe steatosis, and 5 = marked steatosis. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on liver and EpAT was performed for antibodies indicated in the graphs and listed in Supplemental Table 1. IHC staining was quantified using Image J. Adipocyte size from DIO mice was measured on EpAT H&E stained sections using image J (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Additionally, livers from DIO mice were frozen, embedded in OCT and frozen at −80 degrees Celsius. To measure liver lipid content, 5 μm thick cryosections of the liver were stained with Oil red O (Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands). Analyses were performed by an observer who was blinded for the experimental conditions.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA of EpAT and liver was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), while total RNA from muscle was extracted using the GeneJET RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, the Netherlands). qPCR was performed using a SYBR green PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Leusden, the Netherlands) on a ViiA7 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were performed with n = 8 mice (HFD), n = 7 mice (SFD), n = 15 mice (NASH), and n = 6 mice (CD), and results are presented as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by an unpaired t-test, a Mann-Whitney test when appropriate, or a two-way ANOVA when comparing multiple groups using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Johannes Levels for technical assistance. This work was financially supported by The Netherlands CardioVascular Research Initiative: the Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers, the Netherlands, Organization for Health Research and Development, and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences for the GENIUS-II project ‘Generating the best evidence-based pharmaceutical targets for atherosclerosis-II’ (CVON). This study was also supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) (VICI grant 016.130.676 to E.L.), the EU (H2020-PHC-2015-667673, REPROGRAM to E.L.), the European Research Council (ERC consolidator grant CD40-INN 681492 to E.L.), the German Science Foundation (DFG, CRC1123, project A5).

Author Contributions

The study presented here was carried out in collaboration among all authors. S.A. contributed to concept and design, experiments and procedures, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and statistical analysis. M.R., M.T., M.G. and L.B. performed experiments and acquisition of data, N.G. and E.L. contributed to concept and design, data interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and obtained funding.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information Files).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50976-6.

References

- 1.WHO. Obesity and overweight, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (2018).

- 2.Huang W, et al. Depletion of liver Kupffer cells prevents the development of diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2010;59:347–357. doi: 10.2337/db09-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/jci19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang YE, et al. The Roles of Adipokines, Proinflammatory Cytokines, and Adipose Tissue Macrophages in Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance in Modest Obesity and Early Metabolic Dysfunction. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knights AJ, Funnell APW, Pearson RCM, Crossley M, Bell-Anderson KS. Adipokines and insulin action: A sensitive issue. Adipocyte. 2014;3:88–96. doi: 10.4161/adip.27552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grewal IS, Flavell RA. The role of CD40 ligand in costimulation and T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:85–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1996.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan P-Y, et al. Immune Stimulatory Receptor CD40 Is Required for T-Cell Suppression and T Regulatory Cell Activation Mediated by Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:99–108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poggi M, et al. CD40L deficiency ameliorates adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic manifestations of obesity in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2251–2260. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.111.231357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf D, et al. CD40L deficiency attenuates diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation by impairing immune cell accumulation and production of pathogenic IgG-antibodies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatzigeorgiou A, et al. Blocking CD40-TRAF6 signaling is a therapeutic target in obesity-associated insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA. 2014;111:2686–2691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400419111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo CA, et al. CD40 deficiency in mice exacerbates obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance. Am J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;304:E951–963. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00514.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf D, et al. Coinhibitory suppression of T cell activation by CD40 protects against obesity and adipose tissue inflammation in mice. Circulation. 2014;129:2414–2425. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.008055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi Z, Stunz LL, Bishop GA. CD40-mediated maintenance of immune homeostasis in the adipose tissue microenvironment. Diabetes. 2014;63:2751–2760. doi: 10.2337/db13-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schonbeck U, Libby P. The CD40/CD154 receptor/ligand dyad. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:4–43. doi: 10.1007/PL00000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poggi M, et al. The inflammatory receptor CD40 is expressed on human adipocytes: contribution to crosstalk between lymphocytes and adipocytes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1152–1163. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poltorak MP, Schraml BU. Fate mapping of dendritic cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:199. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanovic-Racic M, et al. Dendritic cells promote macrophage infiltration and comprise a substantial proportion of obesity-associated increases in CD11c+ cells in adipose tissue and liver. Diabetes. 2012;61:2330–2339. doi: 10.2337/db11-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Younossi ZM, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta‐analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wentworth JM, et al. Pro-inflammatory CD11c+CD206+ adipose tissue macrophages are associated with insulin resistance in human obesity. Diabetes. 2010;59:1648–1656. doi: 10.2337/db09-0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris DL, et al. CD40 promotes MHC class II expression on adipose tissue macrophages and regulates adipose tissue CD4+ T cells with obesity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016;99:1107–1119. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0115-009R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Ferranti S, Mozaffarian D. The perfect storm: obesity, adipocyte dysfunction, and metabolic consequences. Clin Chem. 2008;54:945–955. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.100156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parlee SD, Lentz SI, Mori H, MacDougald OA. Quantifying size and number of adipocytes in adipose tissue. Methods Enzymol. 2014;537:93–122. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-411619-1.00006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ioannou GN. The Role of Cholesterol in the Pathogenesis of NASH. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozer J, Ratner M, Shaw M, Bailey W, Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245:194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien PJ, Slaughter MR, Polley SR, Kramer K. Advantages of glutamate dehydrogenase as a blood biomarker of acute hepatic injury in rats. Lab Anim. 2002;36:313–321. doi: 10.1258/002367702320162414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feuerer M, et al. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat. Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guiducci C, Valzasina B, Dislich H, Colombo MP. CD40/CD40L interaction regulates CD4+CD25+ T reg homeostasis through dendritic cell-produced IL-2. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:557–567. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin S, Agarwal R, Murugaiyan G, Saha B. CD40 expression levels modulate regulatory T cells in Leishmania donovani infection. J. Immunol. 2010;185:551–559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamano T, et al. Thymic B Cells Are Licensed to Present Self Antigens for Central T Cell Tolerance Induction. Immunity. 2015;42:1048–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg G, et al. Unique properties of thymic antigen-presenting cells promote epigenetic imprinting of alloantigen-specific regulatory T cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35542–35557. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Povoleri GA, et al. Thymic versus induced regulatory T cells - who regulates the regulators? Front Immunol. 2013;4:169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lino AC, Kutchukhidze N, Lafaille JJ. CD25− T cells generate CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by peripheral expansion. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;173:7259–7268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klingenberg R, et al. Depletion of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells promotes hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J. Clin Invest. 2013;123:1323–1334. doi: 10.1172/jci63891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:431–438. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.108.179564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baranowski M. Biological role of liver X receptors. J. Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 7):31–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Rosa V, et al. A key role of leptin in the control of regulatory T cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;26:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matarese G, Procaccini C, De Rosa V, Horvath TL, La Cava A. Regulatory T cells in obesity: the leptin connection. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee S, et al. Leptin is key to peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative stress and Kupffer cell activation in experimental nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:778–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatzigeorgiou A, et al. Dual role of B7 costimulation in obesity‐related nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and metabolic dysregulation. Hepatology. 2014;60:1196–1210. doi: 10.1002/hep.27233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma X, et al. A high‐fat diet and regulatory T cells influence susceptibility to endotoxin‐induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2007;46:1519–1529. doi: 10.1002/hep.21823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rau M, et al. Progression from nonalcoholic fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is marked by a higher frequency of Th17 cells in the liver and an increased Th17/resting regulatory T cell ratio in peripheral blood and in the liver. The Journal of Immunology. 2016;196:97–105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, et al. 3, 3′-diindolylmethane alleviates steatosis and the progression of NASH partly through shifting the imbalance of Treg/Th17 cells to Treg dominance. International Immunopharmacology. 2014;23:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aarts SABM, et al. Macrophage CD40 plays a minor role in obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abram CL, Roberge GL, Hu Y, Lowell CA. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-Cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J Immunol Methods. 2014;408:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seijkens Tom, Hoeksema Marten A., Beckers Linda, Smeets Esther, Meiler Svenja, Levels Johannes, Tjwa Marc, de Winther Menno P. J., Lutgens Esther. Hypercholesterolemia-induced priming of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells aggravates atherosclerosis. The FASEB Journal. 2014;28(5):2202–2213. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information Files).