Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the present study was twofold. First, this study examined the relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning. Second, the study tested the role of emotional exhaustion as a mediator of the relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning. Job Demands-Resources model was used as the underlying theoretical foundation to establish these relationships.

Methods

Two-source time-lagged data were collected from 225 middle-level managers and their 222 immediate supervisors in 87 Pakistani firms spanning different industries. Structural equation modeling and bootstrapping were used to test the hypothesized relationships,.

Results

The study revealed that work alienation is negatively related to both explorative learning and exploitative learning. Moreover, the study also established emotional exhaustion as a mechanism underlying the relationships work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning by showing that work alienation enhances emotional exhaustion, which, in turn, negatively influences both explorative learning and exploitative learning.

Conclusion

By conceptualizing and providing empirical evidence of the negative relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning, both directly and via emotional exhaustion, the study signified some of the important but largely ignored dynamics of the employment relationship within the current regime of organizational structures. The findings suggest that the managers’ sensed estrangement from work and work context need to be addressed, as it can exhaust them emotionally and hinder their search and acquisition of new knowledge and competencies.

Keywords: work alienation, emotional exhaustion, explorative learning, exploitative learning, Job Demands-Resources model

Introduction

Extant literature stresses that organizations need to venture into exploitative and explorative learning simultaneously for gaining sustained competitive advantage.1–4 Exploitative learning refers to the search for and acquisition of knowledge, which often improves and extends an organization’s existing competencies, technologies, practices, and products.1,2,4,5 Explorative learning refers to the search for and acquisition of knowledge, which can change the nature of an organization’s existing competencies, technologies, products, processes, and practices.1,5 Despite being contradictory modes of operations and achieved through entirely different forms of organizing and organizational structures, explorative and exploitative learning are intertwined and complementary for facilitating long-term organizations’ success.3,6,7

Despite being insightful, organizational learning literature1,2,4 has largely ignored and did not inform managers about the destructive repercussions of work alienation – “the extent to which a person is estranged from work, the work context, and the self”8 – for exploitative learning and explorative learning. Consequently, the literature has glossed over the complexities and conflicts involved in the world of work (work context, work itself, and the dynamics of employees’ relationships with the work and work context) within the capitalist regime of economic and social structures of the contemporary organizations.9–11 Additionally, the literature on work alienation has foregrounded the context and working conditions that create a sense of work alienation among employees and its negative influences on several employees’ work-related attitudes, behaviors and performance outcomes, such as employees’ motivation, commitment to the organization, job satisfaction, well-being, work effort, and job performance.12–15 However, theory and empirical evidence about the relationship between work alienation and individual learning – exploitative learning and explorative learning – is scarce. Kanungo9 and Shantz, Alfes, and Truss10 rightly note that work alienation is one of the most under-researched aspects of the workplace. These are unfortunate omissions, considering the destructive effects of work alienation on several employees’ work-related attitudes, behaviors, and performance outcomes14,16 and the likelihood of its negative effect on individual learning.17

The present study, building mainly on Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model,18,19 aims to provide empirical evidence of the relationship between work alienation and individual learning – exploitative and explorative. Additionally, drawing mainly on the JD-R model,18,19 the present study proposes that emotional exhaustion, “the feeling of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by ones’ work”20 mediates the relationships of work alienation with both exploitative learning and explorative learning. By doing so, the work at hand extends three important literature areas – work alienation, emotional exhaustion, and organizational learning – in several ways. First, it attempts to rejuvenate the neglected concept of work alienation by conceptualizing and empirically showing its relationships with emotional exhaustion and explorative and exploitative learning. Second, it extends organizational learning literature by bringing to the fore the destructive influences of work alienation and emotional exhaustion on explorative and exploitative learning. Finally, the study pulls together and advances three important literature areas – work alienation, emotional exhaustion, and organizational learning – by theorizing and empirically verifying emotional exhaustion as a mechanism underlying the relationships of work alienation with exploitative learning and explorative learning. In doing so, the study highlights some of the intricate dynamics of the employment relationship within the current regime of organizational structures. The study emphasizes that overcoming the feelings of work alienation and emotional exhaustion among middle-level managers is particularly important, as they play a central role in organizational learning and growth.

Hypothesis Development

Work Alienation And Exploitative And Explorative Learning

The study draws on the JD-R model18,19 to explain the associations of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning. JD-R model suggests that job characteristics can be modeled in two broad categories – job demands and job resources. Job demands refer to those organizational, social, physical, and psychological aspects of the job that need constant psychological (emotional and cognitive) and physical efforts, and therefore, involve psychological, and physiological costs. The JD-R model further proposes two categories of job demands – challenge demands and hindrance demands.18 Job demands which employees perceive to be potentially contributing to their learning, personal development, and growth can positively affect employees’ behavioral and performance outcomes. On the contrary, job demands which employees perceive as hindrances result in destructive behavioral and performance outcomes. Job resources refer to those organizational, social, physical, and psychological aspects of the job that reduce job demands, facilitate employees’ growth and development, and contribute to the achievement of organizational goals.

Work alienation entails a sense of incomprehensibility among workers about their work role, the means to accomplish the role, the future course of action, and the contribution of the work to a larger purpose.15,21,22 The workers become disillusioned about their work and the significance of their work roles.15,23 The incomprehensibility of one’s work role and its significance and ambiguity about the availability, access and the use of resources to accomplish the work role are the key facets as well as the manifestations of work alienation.21–23 According to the JD-R model, ambiguities concerning the work role and its significance, and uncertainty about the availability of resource are hindrance demands that impede employees’ personal growth, learning, and goal attainment.18,19 Employees’ uncertainty to predict their work-related outcomes, their inability to link the work-related outcomes to a larger purpose negatively influence creativity and intrinsic motivation to acquire new knowledge.24–26

Indeed, the clarity of work purpose is an imperative aspect of employees’ learning and development, as it enrolls employees with the work and organization along with their intellectual and emotional energies, which fuel employees to refine current organizational practices, as well as experiment.25,27 However, those employees who feel a lack of clarity of work purpose demonstrate less commitment to work and organization and are less likely to take initiatives for experimentation.28,29 Likewise, employees’ ambiguity about the availability of resources hinder them from choosing appropriate resources and strategies to solve work-related problems, take risks, engage in experimentation.24,25, In this backdrop, we cogently argue that work alienation shapes various hinderance demands, which manifests in the form of resource ambiguity, a lack of task significance, and inability to anticipate work-related outcomes, and thus can negatively influence their search for and acquisition of new knowledge and competencies.

Moreover, employees’ inability to comprehend and relate the contribution of their work to a larger purpose and a sense of disconnection from other workers (peers) and the work context15,16,21,23 can impede their willingness and capabilities to search for new knowledge. Several scholars30–32 suggest that knowledge is located and acquired through the employees’ consistent entanglement with the work context that facilitates the close interconnectedness of being, thinking, action, and knowing. Schatzki30 suggests that learning takes place in context-bounded and materially-mediated social practice. The social practice carries spaces for interactions with social and material resources that create a shared practical understanding and unlock opportunities for new knowledge creation.30–32 According to Nicolini,31 practice is the “site of knowing”, suggesting that learning is sustained in and transpires through practice and manifests in the form of refinement (exploitative learning) and a change in the nature of existing practices and products (explorative learning).1,2 Following this line of reasoning, we propose that it is likely that employees’ disconnection from the work and the work context can hamper explorative and exploitative learning. The analysis of the literature in this subsection informs the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: work alienation is negatively related to exploitative learning

Hypothesis 2: work alienation is negatively related to explorative learning

Emotional Exhaustion As A Mediator Of The Relationship Between Work Alienation And Learning

Emotional exhaustion is an important aspect of job burnout, a three-dimensional syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion (workers’ feelings of physical overexertion and emotional distress resulting from their continuous interactions with the beneficiaries of their services), depersonalization(the development of cynical attitudes and responses among workers towards the beneficiaries of their services), and diminished personal accomplishment (a sensed lack of achievement at work and the presence of a negative self-concept).20,33,34 Although all three dimensions of burnout are potentially important, a plethora of studies have focused on emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout to investigate its relationship with several employees’ work-related behaviors and outcomes. A number of studies have revealed positive associations of emotional exhaustion with a myriad of destructive work-related behavioral and performance outcomes, such as reduced work motivation, poor work effort, and job performance, withdrawal behavior, and a low of job satisfaction.34–42 Marx43 suggested that alienated workers lack the ability to acquire “physical and mental powers, but instead becomes physically exhausted and mentally debased”. Based on this argument, Conway, Monks, Fu, Alfes, Bailey11 and Shantz, Alfes, Truss10 included the emotional exhaustion component of burnout in their work alienation studies and found that work alienation exacerbates the feelings of emotional exhaustion. Following these scholars, we focused on the emotional exhaustion component of burnout and studied its interrelations with work alienation and learning.

Work alienation manifests in the form of various hinderance demands, such as the incomprehensibility of one’s work role and its significance, and ambiguity about the availability of resources that according to the JD-R model lead to emotional exhaustion.18,19 According to Marx,43 alienated workers become mentally debased and physically exhausted. Past research, albeit scarce, has empirically shown that work alienation is positively related to emotional exhaustion.10,11 Therefore, it is likely that work alienation is positively associated with emotional exhaustion.

Moreover, according to the JD-R model, emotional exhaustion negatively influences employees’ learning and development.18 Past research shows that emotional exhaustion impairs executive (higher-order) cognitive processes, such as abstract thinking, cognitive flexibility, planning, attention, task switching, working memory, and problem-solving.44,45 Emotional exhaustion reduces mental agility and results in cognitive failures and impaired memory.45,46 According to Oosterholt, Van der Linden, Maes, Verbraak, Kompier,45 even a small impairment in the higher-order functions can devastate individuals’ ability to structure and perform their routine tasks, comprehend the problematic situations, and respond adequately to the social contexts. Thus, logically, exhaustion depletes individuals’ resources and capabilities necessary for improving existing practices and perform experimentation. In essence, seen through the lens of the JD-R model, work alienation can negatively influence exploitative and explorative learning via emotional exhaustion. Thus, the following hypotheses are developed.

Hypothesis 3: emotional exhaustion mediates the negative relationship between work alienation and exploitative learning.

Hypothesis 4: emotional exhaustion mediates the negative relationship between work alienation and explorative learning.

Method

Data Collection And Analysis

Two-source survey data were collected in two rounds (separated by a two-month lag time) from 225 middle-level managers and their 222 immediate supervisors in 87 Pakistani firms operating in various manufacturing and service sectors. The purpose of collecting data in two rounds was to reduce common-method bias.47 Likewise, data collection from multiple sources reduces common-method bias.47 The decision to collect data from middle-level managers was inspired by the important roles they play in strategy implementation, organizational learning, and innovation, mainly because of their proximity to both top management and employees.48,49 However, it is argued that if the middle-level managers sense work alienation, and feel emotionally exhausted, their learning endeavors can be hampered that can have devastating effects on organizational learning and growth. Therefore, examining the interrelations between work alienation, emotional exhaustion, explorative learning, and exploitative learning based on the data collected from middle-level managers can offer important practical implications. Thus, the middle-level managers were chosen as the respondents in this study.

Middle-level managers are understood as those managers who are required to report to managers at more senior levels and also have managers who report them. Consistent with this operational definition, 342 middle-level managers were identified and initially contacted at an alumni dinner hosted by a large public sector university. They are provided with an information sheet that contained information about the purpose of our research, the practical importance of the study, and a promise of confidentiality. Of the 342 initially contacted alumni, 332 gave written informed consent to participate in the two rounds of data collection, and they also provided the contact details of their immediate supervisors. The survey questionnaire and postage paid return envelopes were mailed to all the 332 participants who showed written informed consent to participate. In the first round of data collection, 313 responses (94.28% response rate) were received. Of the 313 participants, who responded in the first round, 300 responded in the second round (95.85% response rate). In the first round, data about the independent variable (work alienation), gender, education, age, tenure with the organization, and work experience were collected. Ad hoc measures were used to collect data about the respondents’ age, gender, work experience, and tenure with the organization. The data about the mediator – emotional exhaustion – were collected in the second round.

Data about the outcome variables – explorative learning and exploitative learning – were collected by using supervisors’ rating. A survey package, which included the information sheet, the promise of confidentiality, a paid postage return envelope, and the survey questionnaire was mailed to the immediate supervisors (supervisors henceforth) of the 300 respondents, who responded in both the rounds of data collection. After repeated reminders to the supervisors, 234 responses (78% response rate) were received from the supervisors. That is, supervisors’ ratings for 66 middle-level managers’ learning were not received. The responses were screened for missing data and carelessness. Nine responses were eliminated from data analyses, as they failed to adjust to reverse-coded statements or had missing data. In total, complete data from 225 dyads were received and used for testing the hypotheses. Moreover, 225 middle-managers’ learning was rated by 222 supervisors. Except for three cases (for which one supervisor rated two middle-level managers’ learning), in all other instances, one supervisor rated one middle-managers’ learning.

Participants came from 87 firms spanning different industry sectors, such as cement, electronics, insurance, health, textile, leather, automobile assembler, chemical, engineering, fertilizer, glass and ceramics, oil and gas exploration, and oil and gas marketing. The surveyed middle-level managers were from diverse functional areas. For example, in the textile manufacturing firms, the head of merchandising department (reporting to the head of fabric division) and the head of the stitching department (reporting to the head of garment division) are examples of the respondents from the textile sector. From the cement manufacturing firms, examples of the respondents are the head of exports (reporting to director marketing) and the head of purchase (reporting to director technical and operations). The hierarchical breakdown of the middle managers who participated in the survey showed that 28 percent, 38 percent, and 34 percent were one level, two levels, and three levels below the top managers of their firms, respectively.

In terms of gender, of the 225 middle managers, 192 (85.33%) were males, and 33 (14.66%) were females. All the middle managers had master’s degrees. The middle managers’ age and work experience were 40 years and 8.68 years, respectively. In terms of education, 83 (36.88%) respondents (the middle-level managers) had undergraduate degrees, and 142 (63.11%) had master’s degrees. The 222 supervisors (the respondents who rated middle-managers’ learning) included 209 (94.14%) males and 13 (5.86%) females. The supervisors had an average age of 54.44 years. They had an average experience of 7.50 years in the current position. Data were analyzed using structural equational modeling (SEM) and bootstrapping method (SPPS 25.0 and AMOS 25.0).

Measures And Variables

Unless otherwise stated, all the constructs were measured using a five-point Likert scale anchored on 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Work alienation scale was measured using an eight-item scale (α = 0.85) from Nair and Vohra.23 “Over the years, I have become disillusioned about my works” was a sample item. Emotional exhaustion was measured using a five-item emotional exhaustion scale (α = 0.86) from the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey50 “I feel emotionally drained from my work” was a sample item. Explorative learning (α = 0.92) and exploitative learning (α = 0.90) were measured by adapting five-item scales from Chung, Yang, Huang1 “I collect novel information and ideas that go beyond my experience” was a sample item of the explorative learning scale. “I search for the usual and generally proven methods and solutions to work-related problems” was a sample item of the exploitative learning scale.

Control Variables

Age, gender, education, and work experience can affect individual learning.51–55 According to Deci, Ryan, and Williams,55 personal factors such as age and gender are important predictors of learning behaviors. However, as the sample reflects a male-dominant trend at the managerial positions (85.3%) male respondents from the middle-level managers), the confounding effect of gender is restricted. Therefore, gender was not used as the control variable. In terms of education, middle-level managers were university graduates. Furthermore, for the data used in this study, age and work experience showed a high correlation (r = 0.83, p < 0.001). As work experience seems to have more conceptual relevance to learning, we controlled for work experience. In sum, education and work experience were used as control variables. However, the correlations of education with the outcome variables – exploitative learning (r = −0.06, ns) and explorative learning (r = 0.01, ns) – were non-significant (Table 1). Likewise, the correlations of work experience with the outcome variables – exploitative learning (r = −0.10, ns) and explorative learning (r = 0.01, ns) – were non-significant (Table 1). Therefore, both education and work experience were not included in the structural models.56

Table 1.

Means And Correlations

| Construct | Means | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work alienation | 3.59 | |||||||

| 2. Exhaustion | 3.51 | 0.36** | ||||||

| 3. Explorative learning | 2.30 | −0.38** | −0.35** | |||||

| 4. Exploitative learning | 2.52 | −0.23** | −0.27** | 0.07 | ||||

| 5. Age | 40.01 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | |||

| 6. Gender | 1.15 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.01 | ||

| 7. Education | 1.63 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.01 | |

| 8. Experience | 8.68 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.83** | −0.04 | −0.06 |

Notes: n = 225. ** P <0.01 level (2-tailed). Gender: 1 = male, 2 = female. Education: 1 = undergraduate degree, 2 = master’s degree.

Results

As the respondents belonged to 87 firms, the data were examined for non-independence. ICC (1) values for explorative learning and exploitative learning were 0.03 (ns) and 0.01 (ns), respectively. Thus, non-independence was not an issue in the data.57 Means and correlations are presented in Table 1.

Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the measurement model. The measurement model consisted of work alienation (WA), emotional exhaustion (EE), explorative learning (EXR), exploitative learning (ETT), and twenty-three observed variables. Two items (WA8 and EE4) that showed sub-optimal loadings were dropped. The measurement model (after dropping the problematic items) showed a good fit with the data. The fit indices were χ2(183) = 314.41, χ2/df = 1.71, GFI = 0.88, IFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.06.

Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), maximum shared variance (MSV), and average shared variance (ASV) are presented in Table 2. The measurement scales showed satisfactory levels of internal consistency (α > 0.70) and convergent validity (CR > 0.70; AVE > 0.50). The discriminant validity was also satisfactory for all the scales, as ASV < MSV, ASV and MSV < AVE. Moreover, the square root values of AVE for each variable were greater than their correlations with the other variables of this study (see Table 2, columns 2 to 6).

Table 2.

Reliability, Convergent Validity And Discriminant Validity

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | α | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WA | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.19 | 0.15 | |||

| 2. EE | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.16 | ||

| 3. EXR | −0.44 | −0.43 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.19 | 0.13 | |

| 4. ETT | −0.29 | −0.33 | 0.11 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

Note: n = 225.

Abbreviations: WA, work alienation; EE, emotional exhaustion; EXR, explorative learning; ETT, exploitative learning; MSV, maximum variance shared; ASV, average variance shared; AVE, average variance extracted, Bolded values on the diagonals of columns 2 to 5 are the square root values of AVE; CR, composite reliability; α, Cronbach alpha.

Structural Model

Three steps were used to evaluate the structural model. First, direct relationships between work alienation and the outcome variables – explorative learning and exploitative learning – were tested in the structural model (1). The results showed that work alienation was significantly negatively related to both explorative learning (β = −0.44, p < 0.001) and exploitative learning (β = −0.29, p < 0.001). The fit indices – χ2 (117) = 216.64, χ2/df = 1.85, GFI = 0.90, IFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.06 – showed that the structural model (1) has a good fit with the data. Thus, both hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported.

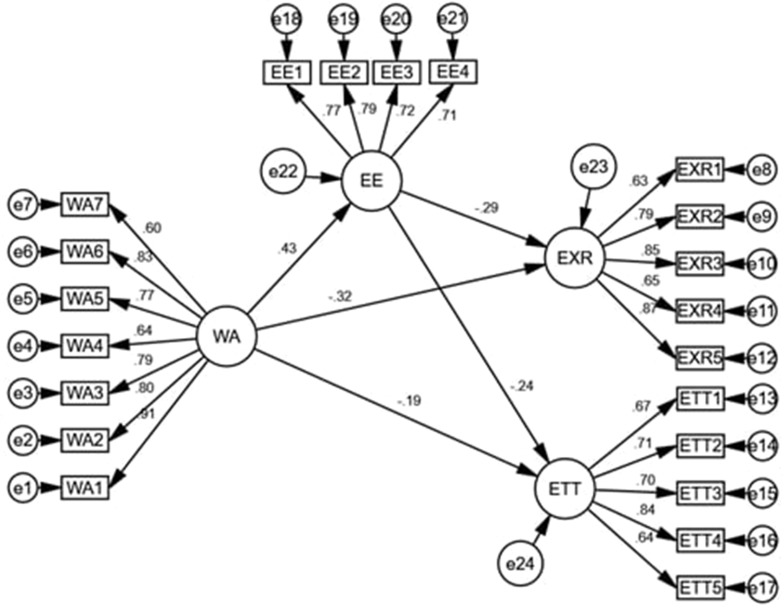

In the second step, the proposed mediator – emotional exhaustion – of the negative relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning was introduced in the structural model (2). The fit indices – χ2(184) = 316.04, χ2/df = 1.72, GFI = 0.88, IFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.06 – showed that the structural model (2) has a good fit with the data, suggesting that the role of emotional exhaustion as a mediator of the negative relationships between the independent and outcome variables is important. The structural model (2) is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural model (2) – mediation model: emotional exhaustion mediates the negative relationship between work alienation and learning.

Abbreviations: WA, work alienation; EE, emotional exhaustion; EXR, explorative learning; ETT, exploitative learning.

Finally, the significance of the role of emotional exhaustion as the mediator was examined by using the bootstrapping technique (by specifying a sample of 20,000 in AMOS 25.0). The bootstrapping results (Table 3) showed that the indirect effects of work alienation on both explorative learning and exploitative learning were significant. Thus, hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported. In other words, emotional exhaustion significantly mediated the negative relationships of work alienation with both exploitative learning and explorative learning.

Table 3.

Direct And Indirect Effects And 95% Confidence Intervals (model 2)

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Direct Effects | |||||

| EE | <— | WA | 0.435* | 0.274 | 0.577 |

| ETT | <— | WA | −0.186 | −0.353 | 0.013 |

| EXR | <— | WA | −0.319* | −0.502 | −0.127 |

| ETT | <— | EE | −0.241* | −0.437 | −0.040 |

| EXR | <— | EE | −0.286* | −0.485 | −0.091 |

| Standardized indirect effects | |||||

| ETT | <— EE | <—WA | −0.105* | −0.221 | −0.024 |

| EXR | <— EE | <—WA | −0.124* | −0.252 | −0.039 |

Notes: *Empirical 95% confidence interval does not overlap with zero.

Abbreviations: WA, work alienation; EE, emotional exhaustion; EXR, explorative learning; ETT, Exploitative learning.

Discussion And Conclusions

In the present study, first, the relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning were examined. Then the mediatory role of emotional exhaustion in these relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning was tested. The JD-R model was used as the underlying theoretical foundation to establish these relationships. Two-source time-lagged collected from 225 middle-level managers and their 222 immediate supervisors in 87 Pakistani firms spanning different industries. The data were analyzed using SEM and bootstrapping, The study revealed that work alienation was negatively related to explorative learning and exploitative learning. The study also showed that emotional exhaustion significantly mediated the negative relationships of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning. Theoretical and practical implications are outlined below.

Theoretical Contributions

The findings have several theoretical implications. First, the present study used the JD-R model18,19 as the underlying theoretical foundation to establish the links between work alienation, emotional exhaustion, explorative learning, and exploitative learning. The choice of the JD-R model is in line with our contention to rejuvenate the concept of work alienation. To our knowledge, this is the first study that explains work alienation and its outcomes through the JD-R model. The theoretical arguments put forward a compelling case of understanding the implications of the intricacy involved in the employment relationship in contemporary organizations. The JD-R model offered a novel vantage point to explicate work alienation as a critical aspect of the work in the present-day organizations that can trigger emotional exhaustion, which, in turn, impedes explorative learning and exploitative learning.

Second, the work at hand extended organizational learning theory. A prolific body of literature devoted to organizational learning has highlighted the importance of explorative and exploitative learning for innovation and gaining competitive advantage.1,2,4,5 Past research has also indicated that employees’ uncertainty to predict their work-related outcomes and their inability to relate their work role with the organizational objectives can negatively affect employees’ creativity and motivation to acquire new knowledge.24–26 Likewise, previous studies have suggested that employees’ lack of clarity about their work role and purpose, and ambiguity about the availability of resources hamper their ability to choose appropriate resources and strategies to solve work-related problems and take risks.24,25,28,29 However, the literature has not considered and elucidated the destructive repercussions of work alienation for exploitative and explorative learning. The present work theorized and empirically showed that work alienation negatively influences both exploitative learning and explorative learning. The findings accentuated the concept of learning as a social practice, i.e., learning stems from engaging with the practice as the site of knowing.30,31 As new knowledge is sustained in and acquired from engaging with the practice,30,31 separation from the work and work context can impede their ability and resources to search for and acquire new knowledge, both explorative and exploitative. Thus, the findings have imperative implications for organizational learning literature that portrays explorative learning and exploitative learning as the mutually complementary building blocks of organizational learning and growth.1,3,5,7

Third, by bringing to the fore work alienation as a crucial aspect of the workplace that can hinder the achievement of organizational learning and growth objectives, this study contributed to the literature on work alienation.11,13,15,16,23 The scarce literature on work alienation has highlighted the destructive influences of work alienation on employees’ work-related behaviors and performance outcomes, including job satisfaction, job involvement, wellbeing, and work effort.10,11,14,15 Despite valuable contributions, these studies do not theorize and provide empirical evidence of the relationship of work alienation with explorative learning and exploitative learning. The work at hand advanced the literature on work alienation13,16,23,30,32 by suggesting that the workers’ incomprehensibility of the organizational affairs, such as their roles, access to resources, and the contribution of their work to a larger purpose can be a destructive influence on their ability to acquire new knowledge.

Fourth, the study contributes to the literature on emotional exhaustion.37,38,40,42 This study revealed that the workers’ ambiguity about their work roles and the access to resources and their inability to link their work-related outcomes to a larger purpose trigger emotional exhaustion, which, in turn, negatively influences managers’ ability to acquire new knowledge. The findings are consistent with the literature21,25 that suggests that role ambiguity and the lack of clarity of the work purpose are positively associated with emotional exhaustion. Likewise, the findings concord with previous studies28,29 that suggest that emotionally exhausted employees are less likely to engage in experimentation. However, the present work advanced this stream of literature by proposing and empirically showing emotional exhaustion as an important mechanism through which work alienation can negatively influence exploitative and exploring learning. By doing so, this study also responds to the recent calls for connecting work alienation to, and keeping it alive, in contemporary theory related to employees’ experiences of the world of work.10,11 Finally, we contributed to the literature through the choice of the sample, which included middle managers, who play a central role in enhancing organizational learning – exploitative and explorative learning.48,49 The findings highlighted the negative repercussions of the middle-level managers’ incomprehensibility of their work role for their emotional exhaustion9,10 and learning endeavors.28

Practical Implications

The findings carry several important practical implications. First, a renewed focus on the job redesign initiatives and improving work conditions is suggested to address the issues related to the managers’ work roles and the significance of these roles for encouraging them to take the risk and engage in experimentation. Second, the findings entail that top managers should interact and provide middle-level managers with feedback regarding the difference their work makes to the others, including employees, organization, and society at large.

Finally, given the centrality of the middle-level managers’ role in strategy execution and achieving organizational learning and growth objectives,48 the middle-level managers’ feelings of work alienation and emotional exhaustion can have far-reaching destructive influences on organizational learning and growth objectives. Therefore, it is suggested top managers focus on reducing emotional exhaustion among the middle-level managers by providing them with the required resources and communicating their work role and the importance of their contribution to the larger purpose. In turn, middle-level managers are likely to experiment, take risks, and make significant contributions to organizational learning and growth.

Limitations And Future Directions

The study is not without limitations. First, although the study is based on time-lagged data collected from two different sources, common methods bias cannot be ruled out. Future studies can use longitudinal data to draw firm conclusions about these interrelations. Second, the study was based on a sample from Pakistan. Studying these relationships in other emerging and developed countries can be helpful in testing the generalizability. Third, explaining the concept of work alienation through the JD-R model allows situating the concept of work alienation in contemporary literature. Therefore, further explorations of this positioning can offer valuable insight into the concept of work alienation, its facets, antecedents, and outcomes.

Fourth, given the untapped of the nature of the relationships of work alienation and exploitative learning and explorative learning, future studies can reveal various mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions of these linkages. Finally, given the destructive effects of work alienation on employees’ numerous work-related behaviors and performance outcomes and the scarcity of research regarding such effects,11 further research focused on uncovering the nomological net of antecedents and outcomes of work alienation can have important implications for theory and practice.11,13,15 For example, alienated employees because of their estrangement from work, work context, and peers9–11 may not engage in knowledge sharing with their peers that may obstruct team performance and the co-creation of new knowledge. Likewise, there is a paucity of studies on how employees’ perception of work alienation can be curbed. This is a surprising omission, considering the negative influence of work alienation on employees learning that can have serious repercussions for organizations’ long-term success. Therefore, future studied should focus on identifying those work conditions and leadership behaviors that can curb employees’ feeling of work alienation. For instance, ethical leadership’s58,59 and spiritual leadership’s60 demonstration of altruistic behaviors and empowering features may mitigate employees’ feelings of estrangement from work and work context. Likewise, servant leadership’s61 central focus on employees’ wellbeing and development can be a potential construct to mitigate employees’ sense of work alienation.

Ethics Statement

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University, Islamabad, Lahore Campus, Pakistan. All participants gave written informed consent.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chung HFL, Yang Z, Huang P-H. How does organizational learning matter in strategic business performance? The contingency role of guanxi networking. J Bus Res. 2015;68(6):1216–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crossan MM, Lane HW, White RE. An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Acad Manage Rev. 1999;24(3):522–537. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2202135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmqvist M. Experiential learning processes of exploitation and exploration within and between organizations: an empirical study of product development. Organ Sci. 2004;15(1):70–81. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1030.0056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usman M, Ahmad MI. Parallel mediation model of social capital, learning and the adoption of best crop management practices: evidence from Pakistani small farmers. China Agr Econ Rev. 2018;10(4):589–607. doi: 10.1108/CAER-01-2017-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.March JG. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci. 1991;2(1):71–87. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2.1.71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katila R, Ahuja G. Something old, something new: a longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad Manage J. 2002;45(6):1183–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benner MJ, Tushman ML. Exploitation, exploration, and process management: the productivity dilemma revisited. Acad Manage Rev. 2003;28(2):238–256. doi: 10.5465/amr.2003.9416096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschfeld RR, Feild HS. Work centrality and work alienation: distinct aspects of a general commitment to work. J Organ Behav. 2000;21(7):789–800. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanungo RN. Alienation and empowerment: some ethical imperatives in business. J Bus Ethics. 1992;11(5):413–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00870553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shantz A, Alfes K, Truss C. Alienation from work: marxist ideologies and twenty-first-century practice AU - Shantz, Amanda. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2014;25(18):2529–2550. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.667431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conway E, Monks K, Fu N, Alfes K, Bailey K. Reimagining alienation within a relational framework: evidence from the public sector in Ireland and the UK AU - Conway, Edel. Int J Hum Resour Man. 2018;1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banai M, Reisel WD. The influence of supportive leadership and job characteristics on work alienation: a six-country investigation. J World Bus. 2007;42(4):463–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2007.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedi A, Pucci L, Tartaglia S, Rollero C. Correlates of work-alienation and positive job attitudes in high- and low-status workers. Career Dev Int. 2016;21(7):713–725. doi: 10.1108/CDI-03-2016-0027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiaburu DS, Thundiyil T, Wang J. Alienation and its correlates: a meta-analysis. Eur Manage J. 2014;32(1):24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2013.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeman M. On the meaning of alienation. Am Sociol Rev. 1959;24(6):783–791. doi: 10.2307/2088565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shantz A, Alfes K, Bailey C, Soane E. Drivers and outcomes of work alienation: revivinga concept. J Manage Inquiry. 2015;24(4):382–393. doi: 10.1177/1056492615573325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeman M, Evans JW. Alienation and learning in a hospital setting. Am Sociol Rev. 1962;27(6):772–782. doi: 10.2307/2090405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The Job Demands‐Resources model: state of the art. J Manage Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(3):499. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nair N, Vohra N. An exploration of factors predicting work alienation of knowledge workers. Manage Decis. 2010;48(4):600–615. doi: 10.1108/00251741011041373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mottaz CJ. Some determinants of work alienation*. Sociol Quart. 1981;22(4):515–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1981.tb00678.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nair N, Vohra N. Developing a new measure of work alienation. JWR. 2009;14(3):293. doi: 10.2190/WR.14.3.c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podsakoff NP, LePine JA, LePine MA. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):438. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Zhang X, Martocchio J. Thinking outside of the box when the box is missing: role ambiguity and its linkage to creativity. Creat Res J. 2011;23(3):211–221. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2011.595661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oldham GR, Cummings A. Employee creativity: personal and contextual factors at work. Acad Manage J. 1996;39(3):607–634. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamel G, Prahalad C. Strategic intent. Harvard Bus Rev. 1989. Available from: http://hbr.org/1989/05/strategic-intent/ar/. Accessed October 25, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Work Redesign. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2004;77(1):11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schatzki TR. Peripheral vision: the sites of organizations. Organ Stud. 2005;26(3):465–484. doi: 10.1177/0170840605050876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicolini D. Practice as the site of knowing: insights from the field of telemedicine. Organ Sci. 2011;22(3):602–620. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gherardi S. Knowing as desiring. Mythic knowledge and the knowledge journey in communities of practitioners. J Work Learn. 2003;15(7/8):352–358. doi: 10.1108/13665620310504846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh W-Y, Cheng Y, Chen C-J. Social patterns of pay systems and their associations with psychosocial job characteristics and burnout among paid employees in Taiwan. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(8):1407–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA. Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cropanzano R, Rupp DE, Byrne ZS. The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(1):160. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relations. Teach Teach Educ. 2010;26(4):1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dishop CR, Green AE, Torres E, Aarons GA. Predicting turnover: the moderating effect of functional climates on emotional exhaustion and work attitudes. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55:733–741. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00407-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDowell WC, Matthews LM, Matthews RL, Aaron JR, Edmondson DR, Ward CB. The price of success: balancing the effects of entrepreneurial commitment, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction. Int Entrepreneurship Manage J. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11365-019-00581-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu Y, Huang X, Tang D, Yang D, Wu L. How guanxi HRM practice relates to emotional exhaustion and job performance: the moderating role of individual pay for performance. Int J Human Resou Manage. 2019. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1588347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park R. Responses to emotional exhaustion: do worker cooperatives matter? Pers Rev. 2018. doi: 10.1108/pr-08-2017-0253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dust SB, Resick CJ, Margolis JA, Mawritz MB, Greenbaum RL. Ethical leadership and employee success: examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. Leadersh Q. 2018;29:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marx K. Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844 In: Marx K, Engels F, editors. Collected Works. Vol. 3 London:Penguin, Ungar;1961:229–346. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cog Psychol. 2000;41(1):49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oosterholt BG, Van der Linden D, Maes JHR, Verbraak MJPM, Kompier MAJ. Burned out cognition — cognitive functioning of burnout patients before and after a period with psychological treatment. Scand J Work Env Hea. 2012;38(4):358–369. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(3):327. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun PYT, Anderson MH. The combined influence of top and middle management leadership styles on absorptive capacity. Manage Learn. 2012;43(1):25–51. doi: 10.1177/1350507611405116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jansen Van Rensburg M, Davis A, Venter P. Making strategy work: the role of the middle manager. J Manage Organ. 2014;20(2):165–186. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2014.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Vol. 21 Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, DeFrank RS. Self-interest and knowledge-sharing intentions: the impacts of transformational leadership climate and HR practices. Int J Hum Resour Manage. 2013;24(6):1151–1164. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.709186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu N-C, Liu M-S. Human resource practices and individual knowledge-sharing behavior–an empirical study for Taiwanese R&D professionals. Int J Hum Resour Manage. 2011;22(04):981–997. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.555138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang S, Hsu W-C, Chen H-C. Age and gender’s interactive effects on learning satisfaction among senior university students. Educ Geront. 2016;42(12):835–844. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2016.1231514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang D-F, Lin S-P. Motivation to learn among older adults in Taiwan. Educ Geront. 2011;37(7):574–592. doi: 10.1080/03601271003715962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deci EL, Ryan RM, Williams GC. Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learn Individ Differ. 1996;8(3):165–183. doi: 10.1016/S1041-6080(96)90013-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Becker KL. Individual and organisational unlearning: directions for future research. Int J Organ Behav. 2005;9(7):659–670. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bliese PD. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SWJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2000:349–381. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2005;97(2):117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Usman M, Hameed AA. The effect of ethical leadership on organizational learning: evidence from a petroleum company. Bus Econ Rev. 2017;9(4):1–22. doi: 10.22547/BER/9.4.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fry LW. Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. Leadersh Q. 2003;14(6):693–727. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenleaf RK. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. New York: Paulist Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]