Abstract

Protozoan parasites can infect the human intestinal tract causing serious diseases. In the following article, we focused on the three most prominent intestinal protozoan pathogens, namely, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium parvum. Both C. parvum and G. lamblia colonize the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum and are the most common causative agents of persistent diarrhea (i.e., cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis). Entamoeba histolytica colonizes the colon and, unlike the two former pathogens, may invade the colon wall and disseminate to other organs, mainly the liver, thereby causing life-threatening amebiasis. Here, we present condensed information concerning the pathobiology of these three diseases.

Keywords: diagnosis, immunopathology, intestinal infections, pathogens, treatment

1. Introduction

Besides bacterial and viral pathogens, protozoan parasites can also infect the human intestinal tract and cause serious diseases [1]. In this article, we will focus on the three most relevant protozoal pathogens, namely, Cryptosporidium parvum (and closely related Coccidia), Giardia lamblia, and Entamoeba histolytica. We regard these organisms as obligate pathogens because they may cause symptoms in otherwise completely healthy individuals and disappear after clearance by the immune system and/or successful chemotherapy. Conversely, opportunistic pathogens are found in healthy individuals as a part of the normal microbiome and cause symptoms in challenged individuals only [2]. A (controversial) example is Blastocystis hominis, one of the most frequent eukaryotes isolated from feces [3] and pathogenic in immunocompromised and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients [4]. Microsporidia belong to the kingdom of fungi [5] and would be the topic of a more detailed review on systemic mycoses.

Giardia lamblia and C. parvum are the most common pathogenic intestinal protozoan parasites and causative agents of persistent diarrhea in humans [6]. In the United States and in Europe, the annual incidences for the two parasitoses are around 104 each. Entamoeba histolytica causes life-threatening amebiasis after invasion of the colon wall and advancement to the liver and other organs. In the EU and the US, most cases of amebiasis are associated with travelers coming from endemic areas. Worldwide, the annual incidence is estimated at around 100 million individuals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Protozoa causing intestinal infections. The protozoa presented in this review are in bold.

| Species |

Classification

(Super Groups) |

Incidence | Pathogenicity | Localization | ||

| World 1 | US 2 | EU 3 | ||||

| Balantidium coli | Cliliata (Diaphoretickes) |

Rare | colon | |||

| Blastocystis sp. | Stramenopile (Diaphoretickes) |

Very high | opportunistic (?) | colon | ||

| Cryptosporidium parvum |

Apicomplexa

(Diaphoretickes) |

nk | 8–9 | 7 | obligate | duodenum, jejunum, ileum |

| Dientamoeba fragilis | Trichomonadina (Excavata) |

Common | unclear, most likely same as G. lamblia | colon | ||

| Entamoeba histolytica |

Amoebozoa

(Amorphea) |

100 | rare | rare | obligate | colon, liver |

| Giardia lamblia |

Diplomonadida

(Excavata) |

250 | 15 | 18 | obligate | duodenum, jejunum, ileum |

| Microsporidia sp. | Fungi (Amorphea) |

Very high | opportunistic | colon | ||

1 WHO (World health organization), NIH (National Institute of Health) (×106/year); 2 CDC (Center of Disease Control), data for 2011–2012; 3 ECDC (European Center of Disease Control), data for 2014–2015 (both ×103/year). nk, not known. Websites: ecdc.europa.eu; www.cdc.gov; www.nlm.nih.gov; www.who.int.

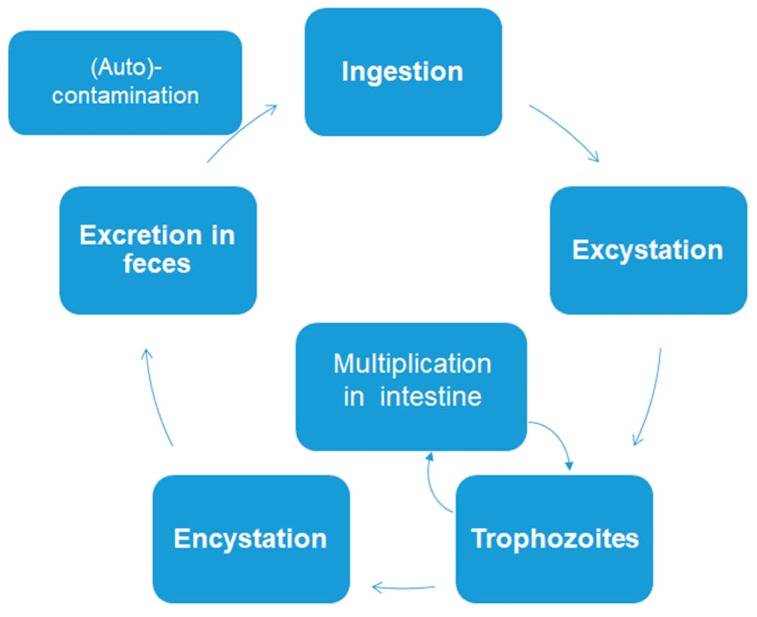

The three intestinal protozoans discussed in this review have very simple biological cycles. There are no intermediate hosts. Cysts or oocysts (Cryptosporidium) are excreted in feces and (auto) infection occurs via ingestion of these permanent stages (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simplified biological cycle of Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium parvum.

As a consequence, due to the poor hygienic conditions, the prevalence of these three intestinal protozoans is, however, much higher in underdeveloped countries thereby constituting a major problem for global health (see Table 2 for an overview).

Table 2.

Overview of diseases caused by the protozoans presented in this review; see Reference [1] and text of this review for further references.

| Giardiasis | Amebiasis | Cryptosporidiosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen | Giardia lamblia | Entamoeba histolytica | Cryptosporidium parvum |

| Transmission | Via (Oo)cysts in feces | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Acute | Persistent diarrhea (>1 w), malabsorption. | Diarrhea, abdominal pain. | Mild-to-acute diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, low-grade fever. |

| Chronic | Malabsorption, loose stools, gassiness, cramping, fatigue, liver or pancreatic inflammations. | Fever, sepsis, liver abscesses, skin lesions. | Severe diarrhea, vomiting, malabsorption, volume depletion and wasting, biliary and respiratory involvement in immunodeficient persons. |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Feces Biopsy material |

Microscopy (cysts), coproantigen test, PCR. | Microscopy (trophozoites, cysts), coproantigen test and PCR. | Microscopy, coproantigen test, PCR, enzyme-immunoassays. |

| Serology | Positive in the case of extraintestinal infection. | ||

| Differential Diagnosis | Cryptosporidiosis, IBS, celiac. | IBD, cancer, bacterial infections. | Giardiasis, Rotavirus, Cyclospora cayetanensis, Clostridium difficile. Microsporidia, IBS, celiac. |

| Management | |||

| First line treatment | Metronidazole (500 to 750 mg p.o. t.i.d., 10 d) | Immunocompetent: NTZ (nitazoxanide)100–500 mg p.o. twice daily, 3 d. HIV: Antiretroviral therapy, possibly combined with NTZ or paromomycin/azithromycin. Other immunodeficiencies: NTZ 500 mg twice daily, 14 d. |

|

| Prevention | Personal hygiene, water treatment, appropriate cleaning and storage of vegetables. | ||

2. Etiology and Epidemiology

2.1. Giardia lamblia

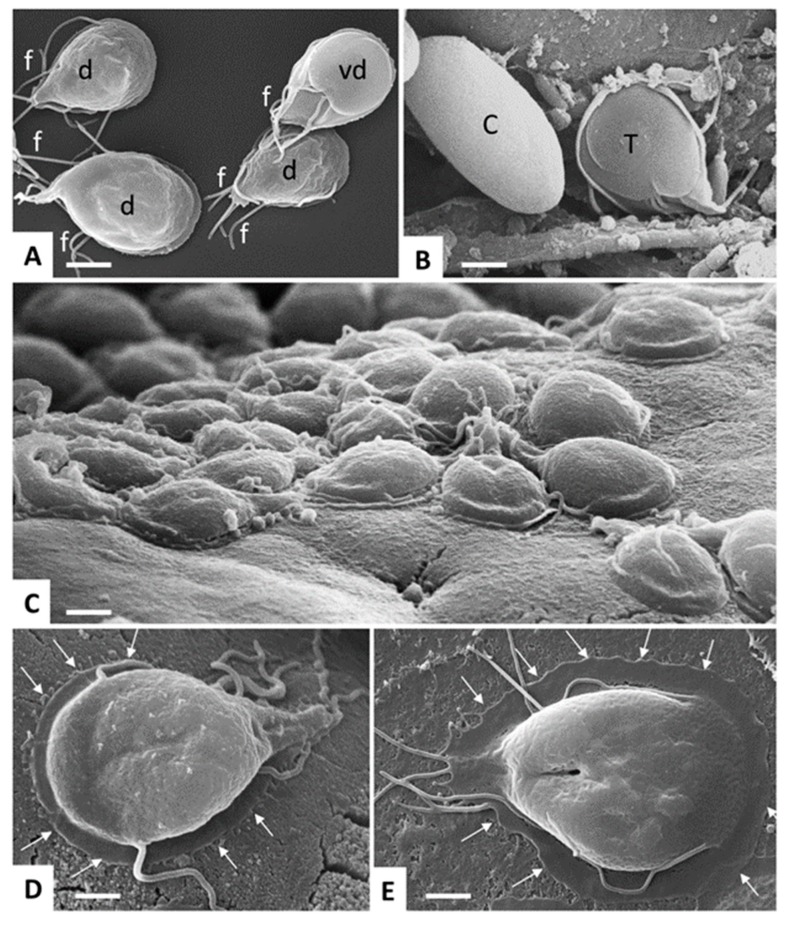

Giardia lamblia is an anaerobic, but to some extent also aerotolerant, eukaryote with several prokaryotic properties [7,8,9] belonging to the phylum Diplomonadida, super-group Excavata [5]. Giardia exists in two morphologic forms: the multi-flagellated trophozoite (four pairs of flagella) and the cyst. The trophozoite is dinucleated, pear-shaped, multi-flagellated, 9 to 15 µm long, 5 to 15 µm wide, and 2 to 4 µm thick, with an adhesive disk on the ventral surface (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Giardia lamblia trophozoites and cysts visualized by SEM. (A) trophozoites cultured in axenic in vitro culture, exposing either their dorsal surface (d) or ventral disc (vd). Note the multiple flagella (f). Bar = 8 µm. (B) Trophozoite (T) and cyst (C) stages in a mouse feces sample. Bar = 6.4 µm. (C) Trophozoites attaching to the intestinal surface of an experimentally infected mouse. Bar = 8 µm. (D,E) Higher magnification view of a trophozoite attaching to the mouse intestinal surface and to human colon carcinoma cells (Caco2) during in vitro culture, respectively. Arrows delineate the periphery of the ventral disc. Bar in (D,E) = 4 µm.

Trophozoites live attached on dudodenal and jejunal epithelial cells and thrive on nutrients from the intestinal fluid with amino acids, especially arginine as their preferred fuel [10,11]. Detached trophozoites form quadrinucleated, thick-walled cysts (8–10 µm in diameter). The cysts are excreted in the feces and constitute the infectious stage. Thus, giardiasis is caused by fecal contaminations of drinking water [12], food [13], or direct contact with feces [14], waterborne transmission being regarded as a major source [15]. Pathogenesis and virulence depend on the genotype of the Giardia strain and the immune and nutritional status of the host. To date, eight genetic assemblages (A to H) have been described. It is well established that isolates from assemblages A and B cause infection in humans [16,17,18]. There is, however, more recent evidence that isolates from assemblage E are pathogenic for humans, as well [19]. Since these strains can be found in humans as well as in animals, giardiasis can be regarded as a zoonosis [20]. Especially, young children living in poor sanitary conditions are exposed to giardiasis which—in combination with malnutrition or immunosuppression (e.g., HIV)—can be fatal. Moreover, persistent infections in children may cause stunting [21].

2.2. Entamoeba histolytica

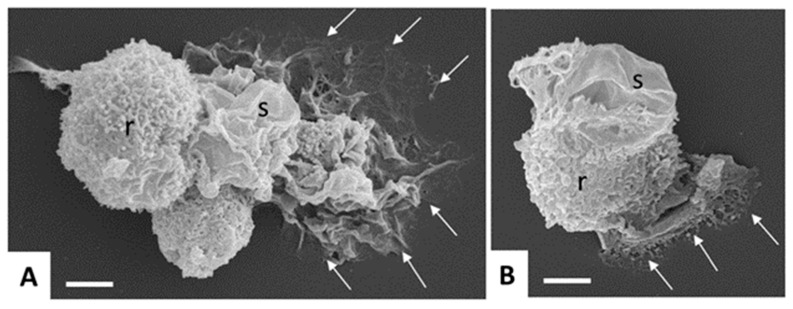

Human amebiasis is caused by E. histolytica (Amoebozoa, Amorphaea). All pathogenic Entamoeba are classified as E. histolytica, whereas the species Entamoeba dispar comprises non-pathogenic Entamoeba strains [22]. As for G. lamblia, two stages can be distinguished, namely, trophozoites and cysts. The motile, mononucleated trophozoite (10 to 20 µm ᴓ, sometimes larger) colonizes the colon (and eventually other organs), where it may transform into the cyst stage having a similar size, but one to four nuclei (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopy of in vitro-cultured Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites. Note the different shapes and cell surface structures such as rough (r) and smooth (s) adopted by the trophozoites, and the cytoplasmic protrusions mediating contact to the surface (arrows). Bar in (A,B) = 5 µm.

Human infection occurs via the ingestion of excreted cysts, thus via fecal–oral contamination upon waterborne, foodborne, or person-to-person transmission. Therefore, poor sanitation and overcrowding are socio-economic factors favoring amebiasis. In the EU and the US, nowadays, cases of amebiasis are mostly associated to travelers coming from endemic areas. Amebiasis is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries [23].

2.3. Cryptosporidium sp.

The genus Cryptosporidium is classified into the phylum Apicomplexa, class Conoidasida, and order Eucoccidiorida. More recent studies, however, indicate, that this genus is more closely related to Gregarines [24]. Currently, 31 valid Cryptosporidium species have been recognized in fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, and an additional 40 distinct genotypes from a variety of vertebrate hosts are described. Nearly 20 species and genotypes have been reported in humans, of which C. hominis and C. parvum account for >90% of all cases [25]. Cryptosporidium hominis transmission occurs via humans, while C. parvum has a high zoonotic potential. There is still a lack of subtyping tools for many Cryptosporidium species of public and veterinary health importance, and the genetic determinants of host specificity of Cryptosporidium species are only poorly understood. Diarrhea is caused through mechanisms involving increased intestinal permeability, chloride secretion, and malabsorption. Although otherwise healthy individuals can acquire infection, other conditions such as immunodeficiency caused by HIV infection, malnutrition, chemotherapy, diabetes mellitus or bone marrow or solid organ transplantation constitute increased risks for more severe and disseminated disease [26]. Livestock, particularly cattle, are important reservoirs of zoonotic infections [27]. The impact is especially devastating in infants in the resource-constrained regions, and disease is associated with an estimated annual death rate of >200,000 children below 2 years of age. An epidemiological study of over 22,000 infants and children in Africa and Asia [28] found that Cryptosporidium was one of the four pathogens responsible for most of the severe diarrhea and was considered the second greatest cause of diarrhea and death in children after Rotavirus [29]. Common means of transmission of cryptosporidiosis is by municipal drinking water and water in swimming pools and via contaminated food. A high risk of infection concerns child care workers, parents of infected children, people who handle infected animals, those exposed to human feces through sexual contact, and healthcare providers as well as pregnant women and individuals suffering from immunodeficiency [26].

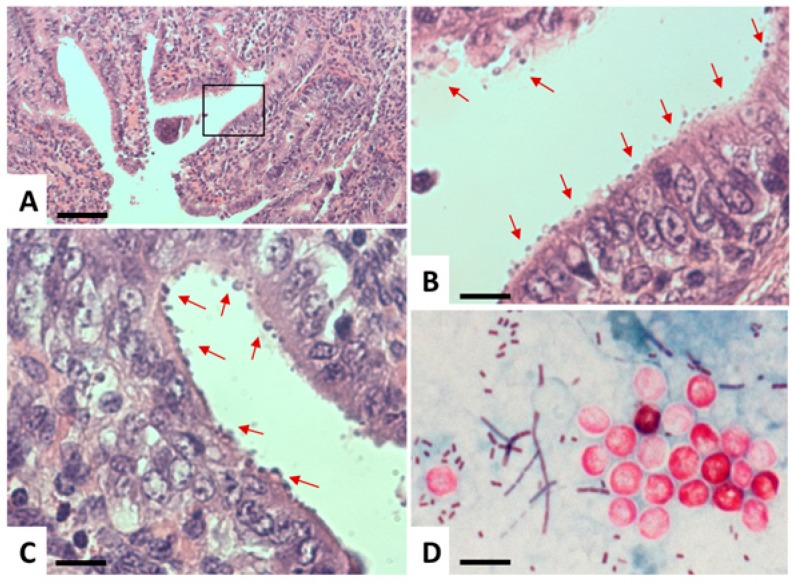

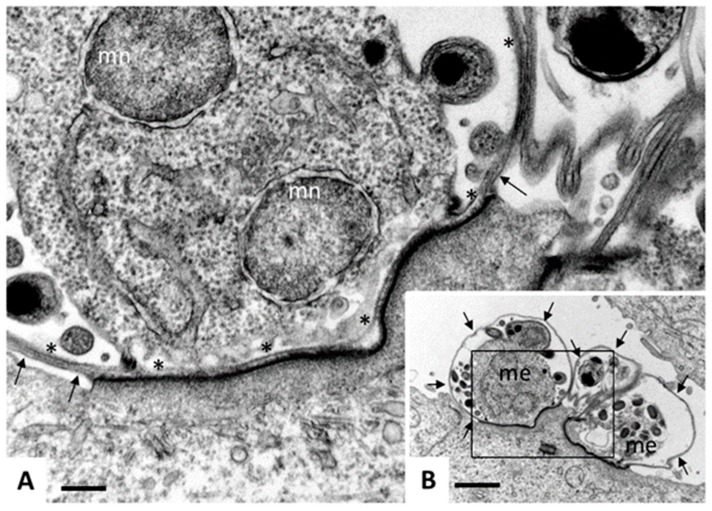

Cryptosporidium has a monoxenous life cycle [30]. Infection takes place via oral ingestion of oocysts containing invasive sporozoites. These sporozoites enter intestinal epithelial cells and form a parasitophorous vacuole (PV) that is located at the apical part of the host cell, just underneath the brush border (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Light microscopy of Cryptosporidium. (A–C) Histological sections of paraffin-embedded C. parvum-infected intestinal tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (A) A low-magnification view, where the boxed area in (A) is magnified in (B). Arrows point towards C. parvum parasitophorous vacuoles seen as round bodies on the surface of the epithelial layer. (D) Modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining of oocysts (red, circular bodies) in a stool sample. Bar in A = 1450 µm; B and C = 260 µm; D = 7.5 µm.

Figure 5.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of Cryptosporidium parvum. Madin Darbey canine kidney (MDCK) cells were infected with C. parvum sporozoites and fixed and processed for TEM after 72 h of culture. Sporozoites have formed parasitophorous vacuoles (PVs) on the apical part of the MDCK cells, occupying a space which is still intracellular, but essentially extra-cytoplasmatic, giving rise to meronts. (B) A low magnification view of three PVs, with two developing meronts (me) clearly visible. Arrows indicate the outer host cell surface membrane. Bar = 12 µm. (C) A higher magnification view of the boxed area in (A). Asterisks (*) indicate the membrane of the parasitophorous vacuole, arrows point towards the host cell surface membrane, mn indicates nuclei of developing merozoites. Note the electron-dense zone where the PV is in close contact to the host cell cytoplasm, formed due to the cytoskeletal rearrangements. Bar = 2.5 µm.

These sporozoites will then develop into merozoites, which either undergo asexual proliferation, egress, and re-infection of other intestinal cells (named type I merozoites), or develop into type II merozoites and undergo sexual development, leading to the formation of a zygote, which produces an oocyst wall and infective sporozoites. In the case that the oocysts are thin-walled, excystation of sporozoites can take place already in the intestine, leading to auto-infection, while thick-walled oocysts are excreted at very large numbers and are infectious upon oral ingestion. Oocysts are environmentally stable and can survive for many months under temperate and moist conditions, and they are resistant to chlorine levels usually applied in water treatment.

3. Pathogenicity and Virulence

3.1. General Remarks

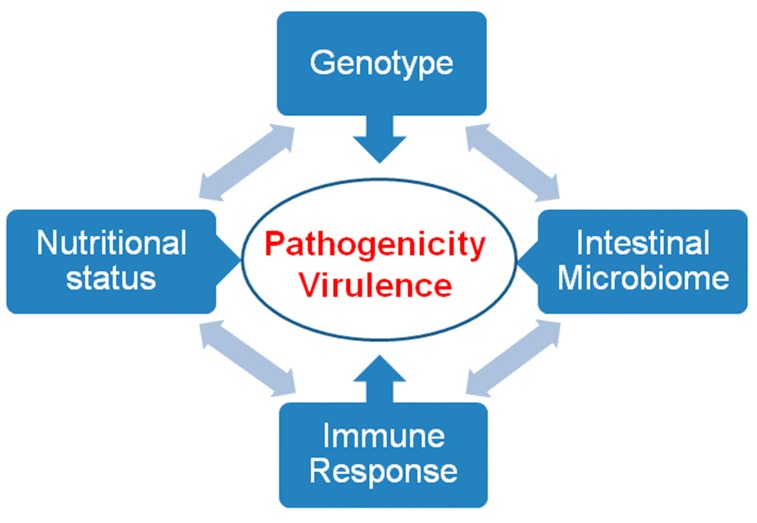

The virulence of an intestinal pathogen results from its own genetic background, the competence of the host immune system, its nutritional status (e.g., the acquisition of iron [31]) and the interaction with other intestinal microorganisms (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pathogenicity and virulence. Pathogenicity and virulence are the result of interactions between the genotype of the pathogen, the immune response, the nutritional status, and the intestinal microbiome of the host.

All three parasites discussed here in detail infect their hosts via ingested cysts and colonize the digestive tract. They attach to the epithelial surface of the duodenum/ileum (Cryptosporidium sp., Giardia lamblia) or colon (Entamoeba histolytica) and elicit an immune response involving interleukin (IL)-6 production by T-cells, dendritic cells and mast cells. Interleukin-6 stimulates IL-17-mediated host defense (production of intestinal IgA (Immunoglobulin A) and anti-microbial peptides). Furthermore, mast cell degranulation promotes peristalsis. The resulting inflammatory reactions (see Reference [32] for review) are more (E. histolytica) or less (G. lamblia) pronounced. Thus, immunopathology may play an important role in the case of E. histolytica, where inflammatory reactions may facilitate the penetration of the colon wall and the subsequent systemic spreading causing amebiasis. In the case of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis, inflammatory reactions are much less pronounced.

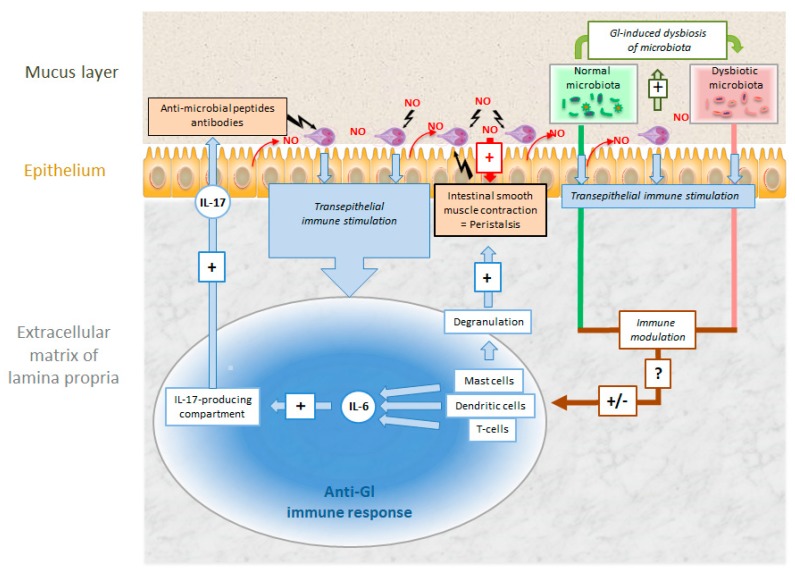

3.2. Giardia lamblia

Unlike other protozoal pathogens, G. lamblia trophozoites and their conversion into cysts can be easily studied in vitro, the genome is sequenced (GiardiaDB.org), molecular genetics are well established, and in vivo-models (e.g., orally cyst-infected mice) are available. Nevertheless, to date, the pathophysiology of giardiasis is not entirely understood [33]. When ingested cysts reach the stomach, their cyst wall is digested and they transform into trophozoites colonizing the epithelium of the duodenum and the proximal jejunum. As a first reaction on part of the host, cells in contact with the trophozoites may undergo apoptosis, epithelial tight junctions are ruptured [34], and CD8+-lymphocytes are activated [35]. As a consequence, brush-border microvilli are shortened [35], resulting in deficiencies in disaccharidases and other enzymes [36]. In a next step, adaptive immune responses are elicited via IL-6-producing dendritic and mast cells [37] and CD4+ T-cells producing IL-17 and TNFalpha [38]. Another potential source of IL-17 are tuft cells that may be stimulated by metabolites excreted by trophozoites thereby enhancing the pro-inflammatory reactions in the intestinal epithelium, as found for closely related protists and for helminths [39]. As a consequence, cytotoxic [40] secretory IgA and defensins are produced resulting in the elimination of trophozoites from the intestinal surface. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) produced by epithelial cells and immune cells inhibits trophozoite proliferation [33,41] and—NO production in neurons—in combination with mast cell degranulation—promotes intestinal peristalsis thus contributing to the expulsion of trophozoites. Although minor, the intestinal microbiota may increase the efficiency of the anti-giardial immune response. In fact, trophozoites may induce dysbiosis of the microbiota resulting in an immunological effect supporting infection [42] (Figure 7). Recent studies consider cysteine proteases involved in pathogenesis, disruption of intestinal epithelial junctions, apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, and also the degradation of host immune factors (e.g., immunoglobulins and chemokines), mucus depletion, and microbic dysbiosis as major virulence factors [18].

Figure 7.

Intestinal colonization of Giardia lamblia (Gl) and host defense mechanisms against the parasite. Explanation see text.

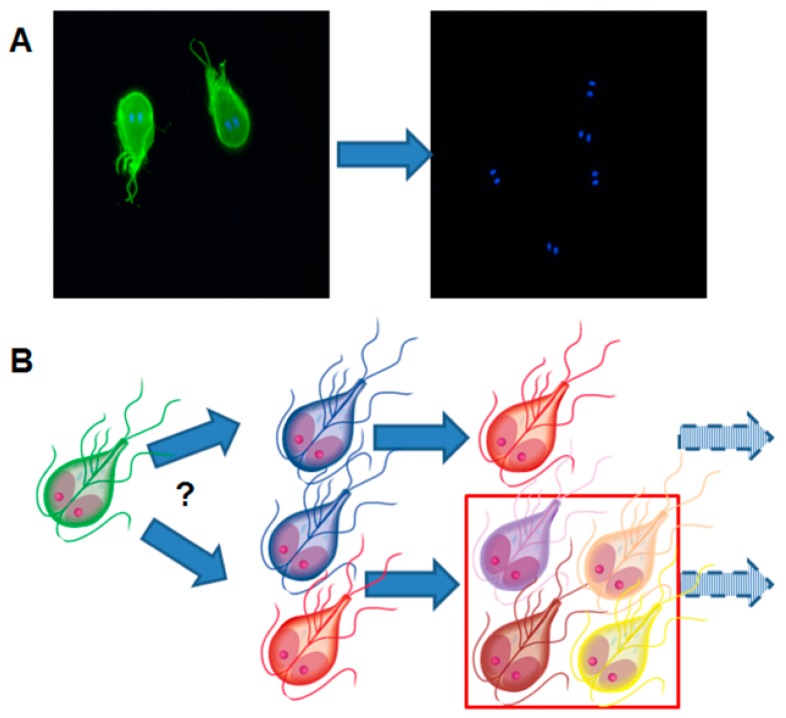

Since IgA recognizes surface proteins as predominant antigens, G. lamblia has developed an escape strategy based on the variation of these surface proteins. According to a generally admitted hypothesis, only one (major) variant surface protein (VSP) is expressed on a single trophozoite [43]. The expression of different VSPs—and thus antigenic variation—is triggered by epigenetic mechanisms involving changes in the chromatin state [44] and/or RNA interference [45,46]. Trophozoites surviving the exposure to IgA react by expressing different variants of these so-called “variant surface proteins” thereby escaping the immune response [47]. This strategy is called “antigenic switch” (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Illustration of the fundamental paradigm of antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia. (A) Trophozoites are stained with a monoclonal antibody directed against the variant surface protein (VSP) H7 (green staining). The presence of trophozoites is visualized by the characteristic staining of the double nuclei. After in vivo culture and re-isolation, the green staining is lost, meaning that new VSPs have replaced VSP H7. (B) Is one VSP replaced by another VSP or by several different VSPs thereby increasing the heterogeneity of the trophozoite population? Transcriptional studies have revealed that after subsequent in vivo cultivation of G. lamblia clone H7, the variability of VSPs increases.

Antigenic switch does not occur only as a reaction to exposure to antibodies, but also to drugs [48,49,50] and is—in all likelihood—epigenetically regulated [51]. Recent results suggest that VSPs play not only a passive role in escaping host immune responses but also may actively participate in damaging epithelial cells via proteolytic activities [52]. An excellent review on parasitic strategies to circumvent host immune reactions is given elsewhere [32].

3.3. Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites are easily cultivated in vitro, the genome has been sequenced (AmoebaDB.org), and susceptible and resistant rodent in vivo models are available, thus allowing experimental investigations of virulence factors [53,54]. While passing the digestive tract, ingested cysts liberate trophozoites proliferating within the colon. Unlike Giardia, they dwell not only on intestinal fluids but produce cysteine proteases and Gal/GalNAc-lectins both damaging the intestinal mucosa by structural destabilization and cellular destruction of the epithelial cell layer. As a consequence, E. histolytica penetrates the intestinal mucosa by evading and, at the same time, exploiting the mucosal immune response of the host. In an initial phase, mucosal inflammation is promoted by secretion of E. histolytica macrophage migration inhibitory factor (EhMIF). Supported by tissue-destructive and cytolytic effectors such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and oxygen free radicals (ROS) produced by infiltrating inflammatory cells, focal perforation of the intestinal mucosa may occur allowing the trophozoites to invade the colon wall [55,56].

Infecting E. histolytica trophozoites, however, have to face different host defense mechanisms, namely, (i) increased mucus production protecting the epithelial surface; (ii) secretion of defensin 2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Il-1β, IL-8, TNF-α) after contact of trophozoites with epithelial cells [57]; (iii) Th1-mediated immune responses during acute amebiasis, and Th2- and Th17-mediated immune responses during chronic amebiasis [58]. Consequently, neutrophils are attracted via IL-8 and macrophages via IL-1β. IL-17 production favors persistence of infection as shown by comparing IL-17-knock-out to wild-type mice [59]. Since E. histolytica trophozoites resist killing by neutrophils, the resulting inflammatory reaction even enhances tissue injury thereby promoting the infection [60]. In 90% of patients, the colon wall is not invaded and the infection remains asymptomatic or with mild symptoms. In the remaining 10%, the colon barrier is broken, and trophozoites spread into the wall and surrounding tissues causing local necrosis and ulcer formation.

Once the colon wall is invaded, however, amebiasis may spread hematogenously to any organ in the body, most commonly the liver and the lungs [60,61]. It is still unclear to which extent host cells are directly involved in the destruction of the colon wall. There is some evidence from in vivo models that the inflammatory reactions of host cells and not proteolytic degradation of the wall by the parasite is responsible for tissue damage, but it is difficult to extrapolate from defined animal models to the situation in patients with diverse physiological backgrounds and immune status [62].

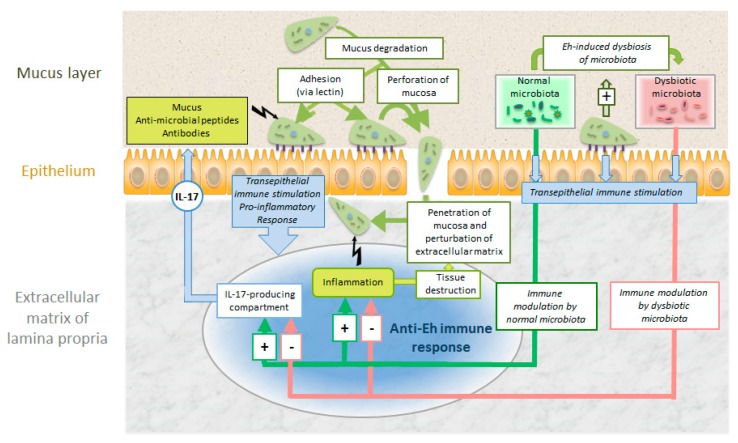

Another intriguing aspect is the interaction with the colon microbiome. Enteric bacteria may stimulate the oxidative stress defenses of E. histolytica [63]. Moreover, there are good indications that E. histolytica causes dysbiosis of the colon microbiome stimulating immune responses facilitating systemic invasion [64]. It is still unclear to which extent this parasite evades or suppresses [65] host immune responses during this systemic spread (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Intestinal colonization and invasion of E. histolytica (Eh) and host defense mechanisms against the parasite. For explanations see text.

3.4. Cryptosporidium sp.

Unlike G. lamblia and E. histolytica, Cryptosporidium sp. (and other closely related Coccidia, e.g., Eimeria sp.) cannot be cultivated axenically [66]. The genome has been sequenced (CryptoDB.org), but genetic manipulation of this protozoal parasite [67] has only recently been established using CRiSPR/Cas-mediated gene targeting [68]. The studies leading to the identification of pathogenicity and virulence factors are performed in coculture systems [69,70] with intestinal [71], biliary [72], tracheal [73] or esophagus [74] epithelial cell layers or organoids [75], where infection, invasion, and differentiation can be studied from a couple of days until several weeks [76]. Based on studies with these systems, factors mediating excystation, invasion, PV formation, intracellular maintenance, and host cell damage could be identified as important virulence factors [77]. After oral uptake of oocysts, Cryptosporidium sporozoites hatch in the small intestine, attach to and invade host epithelial cells [78], preferentially cells in mitosis [79]. This is in good agreement with more recent findings that in pig intestinal cells infected with C. parvum, expression of genes involved in mitosis are upregulated, but neither stress- nor apoptosis-related genes [80]. Host-cell apoptosis is dimmed in early stages of infection and promoted in late stages [81,82,83]. In analogy to related apicomplexan parasites, it can be speculated that Cryptosporidium secretes molecules to the host cell that directly interfere with apoptosis signaling cascades at multiple levels as shown for Toxoplasma gondii [84] and for Theileria sp. [85,86].

Attachment to host cells and invasion is mediated by proteins such as a galactose/N-glactosamin-specific lectin [87] and T. gondii-SAG1 homologous proteins [88] released from a set of secretory organelles, which are constituents of the apical complex. Infection requires extensive remodeling of the cytoskeleton [89], and invaded sporozoites are finally located in a parasitophorous vacuole, surrounded by a parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) that is essentially host cell surface membrane derived and modified after invasion. Once intracellular, parasites remain at the apical domain of the host cell, therefore, the PV is an intracellular but extracytoplasmatic compartment (Figure 5). Thus, the PVM shields parasites from the host defense. Trophozoites are formed and will eventually undergo development into merozoites, as well as sexual development forming sporozoites and oocysts, which are orally infective. Tissue damage occurs through disruption of tight junctions of the epithelium, leading to cytoskeletal alterations, loss of barrier function, and—ultimately—increased cell death. These alterations are caused by lytic enzymes such as phospholipases [90] and proteases [91,92,93,94].

As a response, proinflammatory cytokines like interferon gamma (IFNγ) [95], IL-6, IL-12 [96], IL-17 [97], and chemokines are released to the infection site. A detailed review is given in Reference [98] and the references therein. On the one hand, the resulting inflammatory reactions contribute to increased epithelial permeability, impaired intestinal absorption, and increased secretion thereby enhancing the symptoms like malabsorption and diarrhea. On the other hand, they stimulate innate defense mechanisms [95] such as the release of antimicrobial peptides [99] and acquired immune responses leading ultimately to the control of the infection in immunocompetent hosts (see Figure 7).

4. Control and Treatment

4.1. Prevention

Since all three pathogens discussed in this review are transmitted via cysts [100], the prevention is water treatment by filtration [101] or disinfection by chlorination or radiation [102]. Moreover, person-to-person and animal-to-person transmission can be prevented by standard attention to hygiene (i.e., hand washing). Treatment of asymptomatic persons excreting cysts is indicated to prevent autoinfection and the spread of infection to healthy persons.

4.2. Diagnosis

The standard methodology as well as recent developments in diagnosis of intestinal parasites including G. lamblia, E. histolytica, and C. parvum have recently been summarized in the updated guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation [103]. Conventionally, diagnosis is based on the detection of trophozoites or (oo)cysts in stool samples. In addition, E. histolytica trophozoites can be identified in aspirates or biopsies sampled during colonoscopy or surgery, respectively. Coprological diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis is mostly performed by modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining of acid-fast Cryptosporidium oocysts in fecal smears (see Figure 4). This method is regarded as the gold standard method for diagnosis of this protozoan parasite. While serology is considered to be of minor importance in diagnosis of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis, ELISA tests demonstrating seroconversion as an indicator of an invasive E. histolytica infection are important tools to diagnose acute amebiasis.

Detection of ameba in stool is, however, not conclusive since non-pathogenic Entamoeba strains (E. dispar) cannot be distinguished from pathogenic strains by a mere morphological examination. This problem is solved by various E. histolytica-specific PCR tests [104,105]. A modern multiplex real-time PCR-based method allows the simultaneous detection of Giardia, Entamoeba, and Cryptosporidium in stool samples with high sensitivities and specificities [106]. These tests can be employed not only on stool, but also on biopsy material where trophozoites are rarely visible.

4.3. Treatment

Like for other anaerobic pathogens, the first line treatment of amebiasis and giardiasis—as recommended by the WHO and CDC guidelines—is based on compounds containing a nitro group which is reduced, thereby forming toxic intermediates, metronidazole [107] or related nitroimidazoles being the first choice (see Table 2). The nitro-thiazolide nitazoxanide is active not only against Giardia (in vitro and in vivo) but also against Entamoeba in vitro [108]. Since nitazoxanide and other thiazolides affect host cells also [109], they are not suited for the treatment of systemic infections such as amebiasis. In the case of resistance against nitro drugs which is frequent in Giardia [110], the highly effective benzimidazole albendazole may be used as a second line drug [111]. Many natural compounds, such as essential oils, some fatty acids, isoflavones, etc., inhibit the proliferation of G. lamblia trophozoites with much higher efficacy than metronidazole (see References [112] and references therein). Therefore, a diet combining low protein contents resulting in less free amino acids, especially arginine, available as fuel [11] with traditional herbs, such as basil, garlic, ginger, oregano etc., may constitute an additional management strategy, especially in the case of chronic giardiasis.

Resistance to nitro drugs also occurs in E. histolytica [113]. Therefore, there is a constant interest in novel, druggable targets that are absent in the host [114]. An example for such a target is the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids, e.g., methionine gamma-lyase-mediated catabolism [115]. Since virulence of E. histolytica strains is directly correlated to their oxygen resistance [116], the inhibition of scavengers of reactive oxygen species such as thioredoxin reductase [117] by auranofin, as identified by an unbiased high throughput screening [118] or by related compounds, could constitute a complementary strategy [119].

Against cryptosporidiosis, chemotherapy would be valuable in immunocompromised patients, but an effective regimen has not been established [26]. Nitazoxanide and other non-nitro-thiazolides are effective against cryptosporidiosis in a rodent model [120], but it is unclear whether the compounds act on the parasite or on the host [109]. For some HIV-infected patients, paromomycin, an oral non-absorbed aminoglycoside from Streptomyces rimosus, or paromomycin combined with azithromycin (a macrolide antibiotic) may be at least partially beneficial [121]. In some studies, treatment with nitazoxanide significantly shortened the duration of diarrhea and decreased the risk of mortality in malnourished children [122], and clinical trials showed efficacy in adults [123]. However, other studies showed that nitazoxanide therapy failed to exhibit activity in immunocompromised patients [124,125]. Since the studies showing effectiveness in patients come from one sole source, it is questionable whether there is at all efficacy of nitazoxanide against cryptosporidiosis in patients.

More promising, elevating CD4+ T-cell levels in HIV-infected patients by highly active antiretroviral therapy has led to the cessation of life-threatening cryptosporidial diarrhea [79]. This improvement is likely to result from immune reconstitution but may, in part, also be due to the antiparasitic activity of protease inhibitors. Thus, for therapy in HIV patients, nitazoxanide or paromomycin combined with azithromycin should be considered along with initiating antiretroviral therapy [79,83]. Currently, more promising compounds are being developed [126], including inhibitors of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase [127], calcium-dependent protein kinase I [128], and lipid kinase [129] as the most striking examples.

4.4. Is Vaccination a Suitable Strategy?

Over the last two centuries, vaccination has proven most useful in fighting against a plethora of life-threatening infective agents. Therefore, it is reasonable that many groups invest in developing vaccination tools and strategies against intestinal protozoan pathogens.

In the case of giardiasis, these attempts are hampered by “antigenic switch” (see above). To circumvent this problem, a potential vaccine strain expressing multiple variant surface proteins (VSPs) on a single cell has been created by disrupting the RNA interference mechanism silencing VSP expression [130]. Allegedly, experimentally infected gerbils can be protected against subsequent infections by “vaccination” with this strain or by immunization with recombinant VSPs.

Cryptosporidiosis can be prevented by vaccination with lyophilized oocysts, as shown for calves [131]. This result is of particular interest for the poultry industry where the closely related Eimeria constitute a major problem [132]. As a consequence, there is a constant and continuing effort to identify suitable candidates such as, for example, protein p23 [133], a rhomboid protein [134], or surface glycoproteins [135] as vaccine candidates, either as recombinant proteins, DNA vaccine or expressed in a suitable bacterial strain [136].

Vaccination strategies against both diseases may work in suitable animal models and may even have some relevance for farm animals, but in the case of human patients, they are hampered by the fact that the subpopulations with the highest exposure and the highest risk such as malnourished children and HIV-positive adults are immunocompromised. As consequence, the immune responses elicited by recombinant vaccines are impaired [98]. A successful vaccine candidate against giardiasis should comprise the whole pattern of VSPs that may be expressed on an infective strain. This is impossible since the genomes of the sequenced Giardia strains contain several hundred VSP genes, and not all pathogenic strains are amenable to culture and, thus, to sequencing and characterization of their VSP patterns.

Clearly, vaccination seems to be a more promising strategy against amebiasis [137]. Vaccination with the Gal-lectin [138] successfully prevents amebiasis in gerbils [139,140], baboons [141], and as a subunit vaccine in a mouse model [142]. Moreover, other suitable vaccine candidates have been identified in the Entamoeba genome [143]. The challenge is to pass from a suitable animal model to tests in humans.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Taken together, intestinal protozoan pathogens, in particular G. lamblia, Cryptosporidium sp., and E. histolytica, cause disabling and even life-threatening diseases. Transmitted by cysts, they can be controlled through water treatment. Antigiardial chemotherapy is well established and alternatives to the main lines of treatment are available. Against cryptosporidiosis, suitable treatment options are, however, lacking and constitute an interesting field for future investigations.

Amebiasis, the most lethal of the three, is also the most difficult to treat. Here, the development of both chemotherapy and vaccination will be one of the most challenging issues in parasitology for the future. Another interesting field for investigations would be the influence of overcome giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, and infection by non-invading ameba on the gastrointestinal absorption of nutrients, the microflora, and the immune system [31].

Acknowledgments

We thank Larissa Hofmann (Institute of Parasitology, Bern) for providing micrographs of modified Ziehl–Neelsen stained oocyst preparations, Philipp Olias (Institute of Animal Pathology, University of Bern) for providing histological sections of C. parvum-infected intestinal tissue, and Dominic Ritler (Institute of Parasitology, Bern) for designing parts of the illustrations.

Author Contributions

All three authors equally contributed to the conceptualization and the writing of the present article.

Funding

This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation grants 31003A_163230 and 31003A_184662.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Van Voorhis W. Protozoan infections. Sci. Am. Med. 2014 doi: 10.2310/7900.1015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chabe M., Lokmer A., Segurel L. Gut protozoa: Friends or foes of the human gut microbiota? Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:925–934. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stensvold C.R., Clark C.G. Current status of Blastocystis: A personal view. Parasitol. Int. 2016;65:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts T., Stark D., Harkness J., Ellis J. Update on the pathogenic potential and treatment options for Blastocystis sp. Gut Pathog. 2014;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adl S.M., Simpson A.G., Lane C.E., Lukes J., Bass D., Bowser S.S., Brown M.W., Burki F., Dunthorn M., Hampl V., et al. The revised classification of eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012;59:429–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang D.B., White A.C. An updated review on Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2006;35:291–314. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lujan H.D. Mechanisms of adaptation in the intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Essays Biochem. 2011;51:177–191. doi: 10.1042/bse0510177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller N., Müller J. Giardia. In: Walochnik J., Duchêne M., editors. Molecular Parasitology. Springer; Vienna, Austria: 2016. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upcroft J., Upcroft P. My favorite cell: Giardia. Bioessays. 1998;20:256–263. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199803)20:3<256::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schofield P.J., Edwards M.R., Matthews J., Wilson J.R. The pathway of arginine catabolism in Giardia intestinalis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992;51:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90197-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermathen M., Müller J., Furrer J., Müller N., Vermathen P. 1H HR-MAS NMR spectroscopy to study the metabolome of the protozoan parasite Giardia lamblia. Talanta. 2018;188:429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efstratiou A., Ongerth J., Karanis P. Evolution of monitoring for Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water. Water Res. 2017;123:96–112. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Utaaker K.S., Skjerve E., Robertson L.J. Keeping it cool: Survival of Giardia cysts and Cryptosporidium oocysts on lettuce leaves. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017;255:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldram A., Vivancos R., Hartley C., Lamden K. Prevalence of Giardia infection in households of Giardia cases and risk factors for household transmission. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17:486. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos P.R., Daniel L.A. Occurrence and removal of Giardia spp. cysts and Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts from a municipal wastewater treatment plant in Brazil. Environ. Technol. 2017;38:1245–1254. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2016.1223175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahagún J., Clavel A., Goñi P., Seral C., Llorente M.T., Castillo F.J., Capilla S., Arias A., Gómez-Lus R. Correlation between the presence of symptoms and the Giardia duodenalis genotype. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;27:81–83. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyworth M.F. Giardia duodenalis genetic assemblages and hosts. Parasite. 2016;23:13. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2016013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allain T., Fekete E., Buret A.G. Giardia cysteine proteases: The teeth behind the smile. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35:636–648. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zahedi A., Field D., Ryan U. Molecular typing of Giardia duodenalis in humans in Queensland—First report of Assemblage E. Parasitology. 2017;144:1154–1161. doi: 10.1017/S0031182017000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng Y., Xiao L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:110–140. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogawski E.T., Bartelt L.A., Platts-Mills J.A., Seidman J.C., Samie A., Havt A., Babji S., Trigoso D.R., Qureshi S., Shakoor S., et al. Determinants and Impact of Giardia Infection in the First 2 Years of Life in the MAL-ED Birth Cohort. J. Pediatric Infect. Dis. Soc. 2017;6:153–160. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Ruiz A., Wright S.G. Disparate amoebae. Lancet. 1998;351:1672–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith L.A. Still around and still dangerous: Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica. Clin. Lab. Sci. J. Am. Soc. Med Technol. 1997;10:279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clode P.L., Koh W.H., Thompson R.C.A. Life without a host cell: What is Cryptosporidium? Trends Parasitol. 2015;31:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Certad G., Viscogliosi E., Chabe M., Caccio S.M. Pathogenic mechanisms of Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:561–576. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Checkley W., White A.C., Jr., Jaganath D., Arrowood M.J., Chalmers R.M., Chen X.M., Fayer R., Griffiths J.K., Guerrant R.L., Hedstrom L., et al. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2015;15:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan U., Zahedi A., Paparini A. Cryptosporidium in humans and animals-a one health approach to prophylaxis. Parasite Immunol. 2016;38:535–547. doi: 10.1111/pim.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sow S.O., Muhsen K., Nasrin D., Blackwelder W.C., Wu Y., Farag T.H., Panchalingam S., Sur D., Zaidi A.K., Faruque A.S., et al. The burden of Cryptosporidium diarrheal disease among children <24 months of age in moderate/high mortality regions of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, utilizing data from the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:e0004729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Striepen B. Parasitic infections: Time to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Nature. 2013;503:189–191. doi: 10.1038/503189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White A.C.J. Cryptosporidiosis (Cryptosporidium species) In: Bennett J.E., Dolin R., Blaser M.K., editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2015. pp. 3173–3183. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buret A.G., Motta J.P., Allain T., Ferraz J., Wallace J.L. Pathobiont release from dysbiotic gut microbiota biofilms in intestinal inflammatory diseases: A role for iron? J. Biomed. Sci. 2019;26:1. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorci G., Cornet S., Faivre B. Immune evasion, immunopathology and the regulation of the immune system. Pathogens. 2013;2:71–91. doi: 10.3390/pathogens2010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Romero G., Quintero J., Astiazaran-Garcia H., Velazquez C. Host defences against Giardia lamblia. Parasite Immunol. 2015;37:394–406. doi: 10.1111/pim.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh W.H., Geurden T., Paget T., O’Handley R., Steuart R.F., Thompson R.C., Buret A.G. Giardia duodenalis assemblage-specific induction of apoptosis and tight junction disruption in human intestinal epithelial cells: Effects of mixed infections. J. Parasitol. 2013;99:353–358. doi: 10.1645/GE-3021.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cotton J.A., Beatty J.K., Buret A.G. Host parasite interactions and pathophysiology in Giardia infections. Int. J. Parasitol. 2011;41:925–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott K.G., Logan M.R., Klammer G.M., Teoh D.A., Buret A.G. Jejunal brush border microvillous alterations in Giardia muris-infected mice: Role of T lymphocytes and interleukin-6. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:3412–3418. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3412-3418.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamda J.D., Nash T.E., Singer S.M. Giardia duodenalis: Dendritic cell defects in IL-6 deficient mice contribute to susceptibility to intestinal infection. Exp. Parasitol. 2012;130:288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saghaug C.S., Sornes S., Peirasmaki D., Svard S., Langeland N., Hanevik K. Human memory CD4+ T cell immune responses against Giardia lamblia. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015;23:11–18. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00419-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider C., O’Leary C.E., von Moltke J., Liang H.E., Ang Q.Y., Turnbaugh P.J., Radhakrishnan S., Pellizzon M., Ma A., Locksley R.M. A metabolite-triggered tuft cell-ILC2 circuit drives small intestinal remodeling. Cell. 2018;174:271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stäger S., Gottstein B., Sager H., Jungi T.W., Müller N. Influence of antibodies in mother’s milk on antigenic variation of Giardia lamblia in the murine mother-offspring model of infection. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:1287–1292. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1287-1292.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bénéré E., Van Assche T., Cos P., Maes L. Intrinsic susceptibility of Giardia duodenalis assemblage subtypes A(I), A(II), B and E(III) for nitric oxide under axenic culture conditions. Parasitol. Res. 2012;110:1315–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fink M.Y., Singer S.M. The Intersection of Immune Responses, Microbiota, and Pathogenesis in Giardiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nash T.E. Surface antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;45:585–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kulakova L., Singer S.M., Conrad J., Nash T.E. Epigenetic mechanisms are involved in the control of Giardia lamblia antigenic variation. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1533–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prucca C.G., Slavin I., Quiroga R., Elías E.V., Rivero F.D., Saura A., Carranza P.G., Luján H.D. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia is regulated by RNA interference. Nature. 2008;456:750–754. doi: 10.1038/nature07585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prucca C.G., Lujan H.D. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1706–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nash T.E. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia and the host’s immune response. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997;352:1369–1375. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Müller J., Ley S., Felger I., Hemphill A., Müller N. Identification of differentially expressed genes in a Giardia lamblia WB C6 clone resistant to nitazoxanide and metronidazole. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62:72–82. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emery S.J., Baker L., Ansell B.R.E., Mirzaei M., Haynes P.A., McConville M.J., Svard S.G., Jex A.R. Differential protein expression and post-translational modifications in metronidazole-resistant Giardia duodenalis. Gigascience. 2018;7 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Müller J., Braga S., Heller M., Müller N. Resistance formation to nitro drugs in Giardia lamblia: No common markers identified by comparative proteomics. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2019;9:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gargantini P.R., Serradell M.D.C., Rios D.N., Tenaglia A.H., Lujan H.D. Antigenic variation in the intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016;32:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cabrera-Licona A., Solano-Gonzalez E., Fonseca-Linan R., Bazan-Tejeda M.L., Raul A.-G., Bermudez-Cruz R.M., Ortega-Pierres G. Expression and secretion of the Giardia duodenalis variant surface protein 9B10A by transfected trophozoites causes damage to epithelial cell monolayers mediated by protease activity. Exp. Parasitol. 2017;179:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deloer S., Nakamura R., Mi-Ichi F., Adachi K., Kobayashi S., Hamano S. Mouse models of amoebiasis and culture methods of amoeba. Parasitol. Int. 2016;65:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kantor M., Abrantes A., Estevez A., Schiller A., Torrent J., Gascon J., Hernandez R., Ochner C. Entamoeba histolytica: Updates in clinical manifestation, pathogenesis, and vaccine development. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;2018:4601420. doi: 10.1155/2018/4601420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanchez V., Serrano-Luna J., Ramirez-Moreno E., Tsutsumi V., Shibayama M. Entamoeba histolytica: Overexpression of the gal/galnac lectin, ehcp2 and ehcp5 genes in an in vivo model of amebiasis. Parasitol. Int. 2016;65:665–667. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghosh S., Padalia J., Moonah S. Tissue destruction caused by Entamoeba histolytica parasite: Cell death, inflammation, invasion, and the gut microbiome. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2019;6:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s40588-019-0113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ayala-Sumuano J.T., Tellez-Lopez V.M., Dominguez-Robles Mdel C., Shibayama-Salas M., Meza I. Toll-like receptor signaling activation by Entamoeba histolytica induces beta defensin 2 in human colonic epithelial cells: Its possible role as an element of the innate immune response. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013;7:e2083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mortimer L., Chadee K. The immunopathogenesis of Entamoeba histolytica. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;126:366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deloer S., Nakamura R., Kikuchi M., Moriyasu T., Kalenda Y.D.J., Mohammed E.S., Senba M., Iwakura Y., Yoshida H., Hamano S. IL-17A contributes to reducing IFN-gamma/IL-4 ratio and persistence of Entamoeba histolytica during intestinal amebiasis. Parasitol. Int. 2017;66:817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cornick S., Chadee K. Entamoeba histolytica: Host parasite interactions at the colonic epithelium. Tissue Barriers. 2017;5:e1283386. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2017.1283386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salles J.M., Moraes L.A., Salles M.C. Hepatic amebiasis. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2003;7:96–110. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702003000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perez-Tamayo R., Montfort I., Garcia A.O., Ramos E., Ostria C.B. Pathogenesis of acute experimental liver amebiasis. Arch. Med. Res. 2006;37:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varet H., Shaulov Y., Sismeiro O., Trebicz-Geffen M., Legendre R., Coppee J.Y., Ankri S., Guillen N. Enteric bacteria boost defences against oxidative stress in Entamoeba histolytica. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:9042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27086-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watanabe K., Gilchrist C.A., Uddin M.J., Burgess S.L., Abhyankar M.M., Moonah S.N., Noor Z., Donowitz J.R., Schneider B.N., Arju T., et al. Microbiome-mediated neutrophil recruitment via CXCR2 and protection from amebic colitis. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006513. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakada-Tsukui K., Nozaki T. Immune response of amebiasis and immune evasion by Entamoeba histolytica. Front. Immunol. 2016;7:175. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Müller J., Hemphill A. In vitro culture systems for the study of apicomplexan parasites in farm animals. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013;43:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pawlowic M.C., Vinayak S., Sateriale A., Brooks C.F., Striepen B. Generating and maintaining transgenic Cryptosporidium parvum parasites. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2017;46:20B.2.1–20B.2.32. doi: 10.1002/cpmc.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vinayak S., Pawlowic M.C., Sateriale A., Brooks C.F., Studstill C.J., Bar-Peled Y., Cipriano M.J., Striepen B. Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature. 2015;523:477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.King B.J., Keegan A.R., Robinson B.S., Monis P.T. Cryptosporidium cell culture infectivity assay design. Parasitology. 2011;138:671–681. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karanis P., Aldeyarbi H.M. Evolution of Cryptosporidium in vitro culture. Int. J. Parasitol. 2011;41:1231–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Castellanos-Gonzalez A., Cabada M.M., Nichols J., Gomez G., White A.C., Jr. Human primary intestinal epithelial cells as an improved in vitro model for Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:1996–2001. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01131-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang B.Q., Chen X.M., LaRusso N.F. Cryptosporidium parvum attachment to and internalization by human biliary epithelia in vitro: A morphologic study. J. Parasitol. 2004;90:212–221. doi: 10.1645/GE-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang S., Jian F., Zhao G., Huang L., Zhang L., Ning C., Wang R., Qi M., Xiao L. Chick embryo tracheal organ: A new and effective in vitro culture model for Cryptosporidium baileyi. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;188:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Josse L., Bones A.J., Purton T., Michaelis M., Tsaousis A.D. A Cell Culture Platform for the Cultivation of Cryptosporidium parvum. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2019;53:e80. doi: 10.1002/cpmc.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heo I., Dutta D., Schaefer D.A., Iakobachvili N., Artegiani B., Sachs N., Boonekamp K.E., Bowden G., Hendrickx A.P.A., Willems R.J.L., et al. Modelling Cryptosporidium infection in human small intestinal and lung organoids. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:814–823. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morada M., Lee S., Gunther-Cummins L., Weiss L.M., Widmer G., Tzipori S., Yarlett N. Continuous culture of Cryptosporidium parvum using hollow fiber technology. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016;46:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bouzid M., Hunter P.R., Chalmers R.M., Tyler K.M. Cryptosporidium pathogenicity and virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013;26:115–134. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Hara S.P., Chen X.M. The cell biology of Cryptosporidium infection. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Widmer G., Yang Y.L., Bonilla R., Tanriverdi S., Ciociola K.M. Preferential infection of dividing cells by Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitology. 2006;133:131–138. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mirhashemi M.E., Noubary F., Chapman-Bonofiglio S., Tzipori S., Huggins G.S., Widmer G. Transcriptome analysis of pig intestinal cell monolayers infected with Cryptosporidium parvum asexual stages. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11:176. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2754-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu J., Deng M., Lancto C.A., Abrahamsen M.S., Rutherford M.S., Enomoto S. Biphasic modulation of apoptotic pathways in Cryptosporidium parvum-infected human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:837–849. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00955-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mele R., Gomez Morales M.A., Tosini F., Pozio E. Cryptosporidium parvum at different developmental stages modulates host cell apoptosis in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:6061–6067. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6061-6067.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ojcius D.M., Perfettini J.L., Bonnin A., Laurent F. Caspase-dependent apoptosis during infection with Cryptosporidium parvum. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)00246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luder C.G., Gross U. Apoptosis and its modulation during infection with Toxoplasma gondii: Molecular mechanisms and role in pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;289:219–237. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27320-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heussler V.T., Rottenberg S., Schwab R., Küenzi P., Fernandez P.C., McKellar S., Shiels B., Chen Z.J., Orth K., Wallach D., et al. Hijacking of host cell IKK signalosomes by the transforming parasite Theileria. Science. 2002;298:1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1075462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heussler V.T., Machado J., Fernandez P.C., Botteron C., Chen C.G., Pearse M.J., Dobbelaere D.A. The intracellular parasite Theileria parva protects infected T cells from apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:7312–7317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhat N., Joe A., PereiraPerrin M., Ward H.D. Cryptosporidium p30, a galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific lectin, mediates infection in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34877–34887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Howe D.K., Gaji R.Y., Mroz-Barrett M., Gubbels M.J., Striepen B., Stamper S. Sarcocystis neurona merozoites express a family of immunogenic surface antigens that are orthologues of the Toxoplasma gondii surface antigens (SAGs) and SAG-related sequences. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:1023–1033. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1023-1033.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cardoso R., Soares H., Hemphill A., Leitao A. Apicomplexans pulling the strings: Manipulation of the host cell cytoskeleton dynamics. Parasitology. 2016;143:957–970. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pollok R.C., McDonald V., Kelly P., Farthing M.J. The role of Cryptosporidium parvum-derived phospholipase in intestinal epithelial cell invasion. Parasitol. Res. 2003;90:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0831-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Padda R.S., Tsai A., Chappell C.L., Okhuysen P.C. Molecular cloning and analysis of the Cryptosporidium parvum aminopeptidase N gene. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:187–197. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kniel K.E., Sumner S.S., Pierson M.D., Zajac A.M., Hackney C.R., Fayer R., Lindsay D.S. Effect of hydrogen peroxide and other protease inhibitors on Cryptosporidium parvum excystation and in vitro development. J. Parasitol. 2004;90:885–888. doi: 10.1645/GE-203R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Perez-Cordon G., Nie W., Schmidt D., Tzipori S., Feng H. Involvement of host calpain in the invasion of Cryptosporidium parvum. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wanyiri J.W., Techasintana P., O’Connor R.M., Blackman M.J., Kim K., Ward H.D. Role of CpSUB1, a subtilisin-like protease, in Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro. Eukaryot. Cell. 2009;8:470–477. doi: 10.1128/EC.00306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McDonald V., Korbel D.S., Barakat F.M., Choudhry N., Petry F. Innate immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Parasite Immunol. 2013;35:55–64. doi: 10.1111/pim.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Perez-Cordon G., Yang G., Zhou B., Nie W., Li S., Shi L., Tzipori S., Feng H. Interaction of Cryptosporidium parvum with mouse dendritic cells leads to their activation and parasite transportation to mesenteric lymph nodes. Pathog. Dis. 2014;70:17–27. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Drinkall E., Wass M.J., Coffey T.J., Flynn R.J. A rapid IL-17 response to Cryptosporidium parvum in the bovine intestine. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2017;191:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ludington J.G., Ward H.D. Systemic and mucosal immune responses to Cryptosporidium-vaccine development. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2015;2:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s40475-015-0054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carryn S., Schaefer D.A., Imboden M., Homan E.J., Bremel R.D., Riggs M.W. Phospholipases and cationic peptides inhibit Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoite infectivity by parasiticidal and non-parasiticidal mechanisms. J. Parasitol. 2012;98:199–204. doi: 10.1645/GE-2822.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schaap P., Schilde C. Encystation: The most prevalent and underinvestigated differentiation pathway of eukaryotes. Microbiology. 2018;164:727–739. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Al-Sabi M.N., Gad J.A., Riber U., Kurtzhals J.A., Enemark H.L. New filtration system for efficient recovery of waterborne Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015;119:894–903. doi: 10.1111/jam.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soliman A., El-Adawy A., Abd El-Aal A.A., Elmallawany M.A., Nahnoush R.K., Eiaghni A.R.A., Negm M.S., Mohsen A. Usefulness of sunlight and artificial UV radiation versus chlorine for the inactivation of Cryptosporidium oocysts: An in vivo animal study. Open Access Maced. J. Med Sci. 2018;6:975–981. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.La Hoz R.M., Morris M.I., AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice Intestinal parasites including Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Giardia, and Microsporidia, Entamoeba histolytica, Strongyloides, schistosomiasis, and Echinococcus: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin. Transpl. 2019:e13618. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Freitas M.A., Vianna E.N., Martins A.S., Silva E.F., Pesquero J.L., Gomes M.A. A single step duplex PCR to distinguish Entamoeba histolytica from Entamoeba dispar. Parasitology. 2004;128:625–628. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004005086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roy S., Kabir M., Mondal D., Ali I.K., Petri W.A., Jr., Haque R. Real-time-PCR assay for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:2168–2172. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2168-2172.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Parcina M., Reiter-Owona I., Mockenhaupt F.P., Vojvoda V., Gahutu J.B., Hoerauf A., Ignatius R. Highly sensitive and specific detection of Giardia duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium spp. in human stool samples by the BD MAX Enteric Parasite Panel. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:447–451. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leitsch D. A review on metronidazole: An old warhorse in antimicrobial chemotherapy. Parasitology. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0031182017002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Adagu I.S., Nolder D., Warhurst D.C., Rossignol J.F. In vitro activity of nitazoxanide and related compounds against isolates of Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba histolytica and Trichomonas vaginalis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002;49:103–111. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hemphill A., Müller N., Müller J. Thiazolides, a novel class of anti-infective drugs, effective against viruses, bacteria, intracellular and extracellular protozoan parasites and proliferating mammalian cells. Antiinfect. Agents. 2013;11:22–30. doi: 10.2174/22113626130103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Leitsch D. Drug resistance in the microaerophilic parasite Giardia lamblia. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2015;2:128–135. doi: 10.1007/s40475-015-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pungpak S., Singhasivanon V., Bunnag D., Radomyos B., Nibaddhasopon P., Harinasuta K.T. Albendazole as a treatment for Giardia infection. Ann. Trop Med. Parasitol. 1996;90:563–565. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Müller J., Hemphill A., Müller N. Treatment of giardiasis and drug resistance. In: Luján H., Svärd S., editors. Giardia: A Model Organism. Springer; Wien, Austria: New York, NY, USA: 2011. [(accessed on 25 July 2019)]. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bca9/a2549ee99e86164d17471aa42d1de5e83adf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bansal D., Malla N., Mahajan R.C. Drug resistance in amoebiasis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006;123:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Müller J., Hemphill A. New approaches for the identification of drug targets in protozoan parasites. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013;301:359–401. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407704-1.00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ali V., Nozaki T. Current therapeutics, their problems, and sulfur-containing-amino-acid metabolism as a novel target against infections by “amitochondriate” protozoan parasites. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:164–187. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00019-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ramos-Martinez E., Olivos-Garcia A., Saavedra E., Nequiz M., Sanchez E.C., Tello E., El-Hafidi M., Saralegui A., Pineda E., Delgado J., et al. Entamoeba histolytica: Oxygen resistance and virulence. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009;39:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Arias D.G., Regner E.L., Iglesias A.A., Guerrero S.A. Entamoeba histolytica thioredoxin reductase: Molecular and functional characterization of its atypical properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1820:1859–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Debnath A., Parsonage D., Andrade R.M., He C., Cobo E.R., Hirata K., Chen S., Garcia-Rivera G., Orozco E., Martinez M.B., et al. A high-throughput drug screen for Entamoeba histolytica identifies a new lead and target. Nat. Med. 2012;18:956–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Andrade R.M., Reed S.L. New drug target in protozoan parasites: The role of thioredoxin reductase. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:975. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gargala G., Francois A., Favennec L., Rossignol J.F. Activity of halogeno-thiazolides against Cryptosporidium parvum in experimentally infected immunosuppressed gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2821–2823. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01538-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Masur H., Brooks J.T., Benson C.A., Holmes K.K., Pau A.K., Kaplan J.E., National Institutes of Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:1308–1311. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rossignol J.F., Ayoub A., Ayers M.S. Treatment of diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium parvum: A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Nitazoxanide. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;184:103–106. doi: 10.1086/321008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rossignol J.F., Kabil S.M., El-Gohary Y., Younis A.M. Effect of nitazoxanide in diarrhea and enteritis caused by Cryptosporidium species. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2006;4:320–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Abubakar I., Aliyu S.H., Arumugam C., Hunter P.R., Usman N.K. Prevention and treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007:CD004932. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Amadi B., Mwiya M., Sianongo S., Payne L., Watuka A., Katubulushi M., Kelly P. High dose prolonged treatment with nitazoxanide is not effective for cryptosporidiosis in HIV positive Zambian children: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009;9:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chavez M.A., White A.C., Jr. Novel treatment strategies and drugs in development for cryptosporidiosis. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2018;16:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1500457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Johnson C.R., Gorla S.K., Kavitha M., Zhang M., Liu X., Striepen B., Mead J.R., Cuny G.D., Hedstrom L. Phthalazinone inhibitors of inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase from Cryptosporidium parvum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:1004–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hulverson M.A., Vinayak S., Choi R., Schaefer D.A., Castellanos-Gonzalez A., Vidadala R.S.R., Brooks C.F., Herbert G.T., Betzer D.P., Whitman G.R., et al. Bumped-kinase inhibitors for cryptosporidiosis therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:1275–1284. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Manjunatha U.H., Vinayak S., Zambriski J.A., Chao A.T., Sy T., Noble C.G., Bonamy G.M.C., Kondreddi R.R., Zou B., Gedeck P., et al. A Cryptosporidium PI(4)K inhibitor is a drug candidate for cryptosporidiosis. Nature. 2017;546:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature22337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rivero F.D., Saura A., Prucca C.G., Carranza P.G., Torri A., Lujan H.D. Disruption of antigenic variation is crucial for effective parasite vaccine. Nat. Med. 2010;16:551–557. doi: 10.1038/nm.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Harp J.A., Goff J.P. Protection of calves with a vaccine against Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Parasitol. 1995;81:54–57. doi: 10.2307/3284005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lillehoj E.P., Yun C.H., Lillehoj H.S. Vaccines against the avian enteropathogens Eimeria, Cryptosporidium and Salmonella. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2000;1:47–65. doi: 10.1017/S1466252300000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Askari N., Shayan P., Mokhber-Dezfouli M.R., Ebrahimzadeh E., Lotfollahzadeh S., Rostami A., Amininia N., Ragh M.J. Evaluation of recombinant P23 protein as a vaccine for passive immunization of newborn calves against Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasite Immunol. 2016;38:282–289. doi: 10.1111/pim.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yang Y., Xue X., Yang Y., Chen X., Du A. Efficacy of a potential DNA vaccine encoding Cryptosporidium baileyi rhomboid protein against homologous challenge in chickens. Vet. Parasitol. 2016;225:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Haserick J.R., Klein J.A., Costello C.E., Samuelson J. Cryptosporidium parvum vaccine candidates are incompletely modified with O-linked-N-acetylgalactosamine or contain N-terminal N-myristate and S-palmitate. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mead J.R. Challenges and prospects for a Cryptosporidium vaccine. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:335–337. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Quach J., St-Pierre J., Chadee K. The future for vaccine development against Entamoeba histolytica. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014;10:1514–1521. doi: 10.4161/hv.27796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lotter H., Tannich E. The galactose-inhibitable surface lectin of Entamoeba histolytica, a possible candidate for a subunit vaccine to prevent amoebiasis. Behring Inst. Mitt. 1997;99:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mann B.J., Burkholder B.V., Lockhart L.A. Protection in a gerbil model of amebiasis by oral immunization with Salmonella expressing the galactose/N-acetyl D-galactosamine inhibitable lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. Vaccine. 1997;15:659–663. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ivory C.P., Chadee K. Intranasal immunization with Gal-inhibitable lectin plus an adjuvant of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides protects against Entamoeba histolytica challenge. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:4917–4922. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00725-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Abd Alla M.D., Wolf R., White G.L., Kosanke S.D., Cary D., Verweij J.J., Zhang M.J., Ravdin J.I. Efficacy of a Gal-lectin subunit vaccine against experimental Entamoeba histolytica infection and colitis in baboons (Papio sp.) Vaccine. 2012;30:3068–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Barroso L., Abhyankar M., Noor Z., Read K., Pedersen K., White R., Fox C., Petri W.A., Jr., Lyerly D. Expression, purification, and evaluation of recombinant LecA as a candidate for an amebic colitis vaccine. Vaccine. 2014;32:1218–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Chaudhry O.A., Petri W.A., Jr. Vaccine prospects for amebiasis. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2005;4:657–668. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]