The ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor produces lipochitooligosaccharides that activate nuclear calcium spiking in its Populus host and then uses the common symbiosis pathway to colonize Populus.

Abstract

Mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic associations with the roots of most land plants and provide them with mineral nutrients from the soil in exchange for fixed carbon derived from photosynthesis. The common symbiosis pathway (CSP) is a conserved molecular signaling pathway in all plants capable of associating with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. It is required not only for arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis but also for rhizobia–legume and actinorhizal symbioses. Given its role in such diverse symbiotic associations, we hypothesized that the CSP also plays a role in ectomycorrhizal associations. We showed that the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor produces an array of lipochitooligosaccharides (LCOs) that can trigger both root hair branching in legumes and, most importantly, calcium spiking in the host plant Populus in a CASTOR/POLLUX-dependent manner. Nonsulfated LCOs enhanced lateral root development in Populus in a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CCaMK)-dependent manner, and sulfated LCOs enhanced the colonization of Populus by L. bicolor. Compared with the wild-type Populus, the colonization of CASTOR/POLLUX and CCaMK RNA interference lines by L. bicolor was reduced. Our work demonstrates that similar to other root symbioses, L. bicolor uses the CSP for the full establishment of its mutualistic association with Populus.

INTRODUCTION

Mycorrhizal fungi are filamentous microorganisms that establish symbiotic associations with the roots of ∼90% of terrestrial plant species (Brundrett and Tedersoo, 2018). There are four major types of mycorrhizal associations, and the two most ecologically and economically important associations are arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) and ectomycorrhizal (ECM; van der Heijden et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2016). AM fungi, which belong to the phylum Mucoromycota (subphylum Glomeromycotina; Spatafora et al., 2016, 2017), likely played a crucial role in the successful colonization of land by plants at least 450 million years ago (Remy et al., 1994; Redecker et al., 2000; Heckman et al., 2001; Delaux et al., 2013; Feijen et al., 2018). At present, AM fungi colonize ∼72% of plant species, including most agronomically important crops (Brundrett and Tedersoo, 2018). Fossil evidence of ECM associations date back to only 50 million years ago, but molecular clock analyses suggest that they likely evolved at least 130 million years ago (Berbee and Taylor, 1993; Lepage et al., 1997; Wang and Qiu, 2006; Hibbett and Matheny, 2009). ECM fungal species belong to one of three fungal phyla, including Ascomycota (subphylum Pezizomycotina), Basidiomycota (subphylum Agaricomycotina), or Mucoromycota (subphylum Mucoromycotina; Spatafora et al., 2017). They associate with 2% of plant species, including mostly woody plants, and they play a crucial role in various forest ecosystems, which cover ∼30% of the global terrestrial surface (Tedersoo et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2013).

In both AM and ECM associations, mycorrhizal fungi not only provide their host plant with mineral nutrients mined from the soil, especially phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium, but also confer protection against a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses (Jeffries et al., 2003; Smith and Read, 2010; Garcia and Zimmermann, 2014; Garcia et al., 2017). In exchange, the plant delivers to the fungus various forms of photosynthetically derived carbon (Casieri et al., 2013). Although AM and ECM fungi offer similar nutrient exchange services to their host plants, there are distinct differences in the structures they use to do so. AM fungi use hyphopodia as penetration structures to traverse the cell wall of root epidermal cells and enter plant roots where they proliferate both inter- and intracellularly. Ultimately, they form highly branched hyphal structures called arbuscules in root cortical cells. By contrast, ECM fungi form a hyphal sheath or mantle that encases the entire root tip with an underlying network of hyphae called the Hartig net. This network surrounds, but does not penetrate into, plant epidermal and cortical cells (Balestrini and Bonfante, 2014). The arbuscule and Hartig net both provide interfaces for the exchange of nutrients between host and fungus.

Given the crucial role of mycorrhizal associations in both natural and agricultural environments, extensive research has focused on determining their evolutionary origin, the molecular mechanisms regulating their development, and the benefits that they provide to plants (Bonfante and Genre, 2010; Garcia et al., 2015; Strullu-Derrien et al., 2018). Over the past two decades, significant advances have been made in elucidating the molecular signaling mechanisms required for AM fungi to colonize plants (Kamel et al., 2017; Luginbuehl and Oldroyd, 2017; MacLean et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2018). In brief, low phosphorus availability in the soil leads to reduced phosphorus levels within plant tissues (Kafle et al., 2019). This deficiency triggers increased biosynthesis of strigolactones, a class of plant hormones that also function as signaling molecules for AM fungi (Akiyama and Hayashi, 2006; Yoneyama et al., 2007; Gomez-Roldan et al., 2008; Umehara et al., 2008). These strigolactones are exported across the plasma membrane into the rhizosphere by the ATP binding cassette transporter PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE1 (PDR1; Kretzschmar et al., 2012). Upon detection by AM fungi, strigolactones induce spore germination and hyphal branching (Akiyama et al., 2005; Besserer et al., 2006, 2008). Through an unknown signaling mechanism, strigolactones also stimulate AM fungi to produce short-chain (four- to five-chain) chitin oligomers (COs; Genre et al., 2013). Both COs and lipochitooligosaccharides (LCOs; Maillet et al., 2011) are components of the complex Myc factors that AM fungi produce to communicate with the host plant (Sun et al., 2015).

Initially, LCOs were identified as essential signaling molecules produced by most rhizobia (Lerouge et al., 1990). Their discovery was made possible by using a bioassay known as root hair branching, a phenomenon characterized by a transient cessation of polarized root hair growth and the subsequent re-polarization of growth in a different direction, leading to a characteristic root hair deformation (Heidstra et al., 1994). Root hair branching was used to study the activity of nodulation (Nod) factors produced by rhizobia on the roots of legumes (Bhuvaneswari and Solheim, 1985). The first chemical structure of a Nod factor from Rhizobium meliloti was determined by mass spectrometry and was shown to be a sulfated β-1,4-tetrasaccharide of d-glucosamine with three acetylated amino groups and one acylated with a C16 bisunsaturated fatty acid. This purified LCO specifically induced root hair branching at nanomolar concentrations in the host alfalfa (Medicago sativa), but not in the nonhost common vetch (Vicia sativa; Lerouge et al., 1990). This host-specific induction of root hair branching in alfalfa was conferred by a sulfate group on the reducing end of the LCO (Truchet et al., 1991). Thus, root hair branching is an excellent bioassay for LCO detection because specific leguminous plant species are extremely sensitive to and are only induced by specific LCO structures. The same root hair branching assays with V. sativa were later used to detect the presence and activity of nonsulfated LCOs (nsLCOs) purified from germinating spore exudates (GSEs) of the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. Mass spectrometry was also used to further characterize the precise LCO structures (Maillet et al., 2011).

During AM symbiosis, both short-chain COs and LCOs are released into the rhizosphere and function as signaling molecules to the plant. They are perceived on the plasma membrane of the host plant by lysine-motif receptor-like kinases that function in concert with a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase coreceptor termed NORK/DMI2/SymRK (Stracke et al., 2002; Op den Camp et al., 2011; Miyata et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). NORK interacts with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase1 (HMGR1), leading to the production of mevalonate (Kevei et al., 2007; Venkateshwaran et al., 2015). Through an unknown cascade of events, mevalonate activates a suite of both nuclear ion channels (including CASTOR, DMI1/POLLUX) and cyclic nucleotide-gated calcium channels. These ion channels facilitate the flow of calcium ions (Ca2+) from the perinuclear space into both the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm immediately surrounding the nucleus (Ané et al., 2004; Charpentier et al., 2008, 2016; Venkateshwaran et al., 2012, 2015). A calcium ATPase, MCA8, localized to the nuclear membrane actively pumps Ca2+ back into the perinuclear space, thus inducing repetitive oscillations in Ca2+ concentration within and around the nucleus (Capoen et al., 2011). This phenomenon is commonly referred to as Ca2+ spiking and is dependent on all of the components described above from the lysine-motif receptor-like kinases to the nuclear ion channels. COs and LCOs are capable of triggering Ca2+ spiking even in the absence of the fungus (Genre et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015).

Repetitive Ca2+ spikes in the nucleoplasm lead to the activation of the calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase DMI3/CCaMK that then phosphorylates its primary target, the transcription factor IPD3/CYCLOPS (Lévy et al., 2004; Messinese et al., 2007; Yano et al., 2008; Horváth et al., 2011; Singh and Parniske, 2012). Upon phosphorylation, IPD3/CYCLOPS regulates the expression of multiple transcription factors required for the development of AM symbiosis (Luginbuehl and Oldroyd, 2017; MacLean et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2018). This elaborate molecular signaling pathway is referred to as the common symbiosis pathway (CSP) because all of the described components are required not only for AM symbioses but also for rhizobia–legume and actinorhizal symbioses (Venkateshwaran et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2017).

A significant body of research on signaling mechanisms in ECM associations exists as well (reviewed in Martin et al., 2016). Regarding diffusible signals released by plants, strigolactones do not appear to affect hyphal branching in the ECM fungal species Laccaria bicolor and Paxillus involutus (Steinkellner et al., 2007). However, the flavonol rutin stimulated hyphal growth in Pisolithus tinctorius and the cytokinin zeatin altered hyphal branch angle (Lagrange et al., 2001). Multiple diffusible signals produced by ECM fungi altered plant growth and development: hypaphorine from Pisolithus tinctorius inhibited root hair elongation and induced increased cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in Eucalyptus globulus (Ditengou et al., 2000; Dauphin et al., 2007), auxin released by an overproducing mutant of Hebeloma cylindrosporum exhibited increased mycorrhizal activity (Gay et al., 1994), and auxin released by L. bicolor enhanced lateral root formation in Populus (Felten et al., 2009, 2010; Vayssières et al., 2015). Diffusible signals from AM fungi were also shown to stimulate enhanced lateral root development in Medicago truncatula (Oláh et al., 2005). Later, these signals were identified as nsLCOs and sulfated LCOs (sLCOs), and both induced lateral root formation in a CSP-dependent manner (Maillet et al., 2011).

Given the role of the CSP in three distinct beneficial plant–microbe associations—the AM, rhizobia–legume, and actinorhizal symbioses—we hypothesized that ECM fungi produce LCOs to communicate with their host via activation of the CSP. To test this hypothesis, we used the model basidiomycete ECM fungus L. bicolor and the host plant Populus, a model woody plant species that contains all of the components of the CSP in its genome (Garcia et al., 2015). Here, we present data that confirm our hypothesis using biological, biochemical, and molecular techniques.

RESULTS

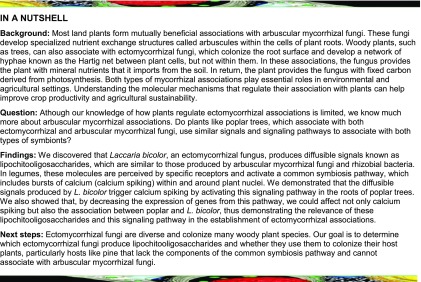

Laccaria bicolor Produces LCOs

We chose the ECM fungus L. bicolor as part of our experimental system because it is was the first ECM fungus to have its genome sequenced (Martin et al., 2008). It has therefore become the primary model fungus for studying ECM associations. To determine whether LCOs are produced by L. bicolor, we first performed root hair branching assays with two species of model legumes, M. truncatula and Vicia sativa. Use of these two species for bioassays allowed us to screen for both sLCOs and nsLCOs, respectively, in hyphal exudates from L. bicolor. In response to the exudates, root hair branching occurred in both M. truncatula and V. sativa at a level comparable to the level induced by the positive control for each species—sLCOs (10−8 M) and nsLCOs (10−8 M), respectively. GSEs from Rhizophagus irregularis were applied as an additional positive control and also induced root hair branching. We did not observe root hair branching in either plant species in response to mock or tetra-N-acetyl chitotetraose (CO4, 10−6 M; Figure 1A) treatments. We quantified the amount of root hair branching that occurred in response to each treatment on 3-cm root fragments from five roots of each plant species (Supplemental Figure 1). Our results suggest that L. bicolor produces both sLCOs and nsLCOs.

Figure 1.

Detection of LCOs Produced by the ECM Fungus L. bicolor Using Root Hair Branching Assays and Mass Spectrometry.

(A) Representative images from root hair branching assays with two species of legumes, M. truncatula (left) and V. sativa (right). In both species, root hair branching (black arrows) occurred in response to the application of hyphal exudates from L. bicolor, LCOs, and GSEs from the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. No branching occurred in response either to mock treatment (water + 0.005% ethanol) or to the negative control (CO4; 10−6 M). sLCOs (10−8 M) and nsLCOs (10−8 M) served as the positive control for M. truncatula and V. sativa, respectively (see also Supplemental Figure 1). Bars = 50 µm.

(B) General structure of LCOs detected by mass spectrometry in the culture medium of L. bicolor. Among the LCOs detected were short-chain COs of different lengths (n = 1, 2, or 3 corresponding to CO length III, IV, or V, respectively) with different combinations of functional groups (R1 = H or methyl [Me], R2 = fatty acid [C16:0, C18:0 or C18:1], R3, 4, 5 = H or Cb, R6 = H or deoxyhexose, proposed as Fuc).

(C) Proposed structure of one of the most representative LCO molecules detected: LCO-III C18:1, N-Me, Cb, Fuc, based on known Nod factors (Price et al., 1992). The deoxyhexose on the reducing end of the structure is proposed to be an l-Fuc and the unsaturation of the fatty acid is proposed to be Δ9. Calculated precursor ion (M+H)+ m/z 1053.5, calculated B1 ion (M+H)+ m/z 483.3.

(D) Single reaction monitoring chromatogram obtained in liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-triple quadrupole linear ion trap) with detection of the precursor ion (M+H)+ m/z 1053.5 giving, after fragmentation, the product ion B1 m/z 483.3. The observed peak is at a retention time of 17.1 min.

(E) High-resolution liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionisation Q-Exactive) in scanning mode (m/z 350-1900) with detection of the precursor ion (M+Na)+ m/z 1075.5622 (calculated for C48H84N4O21Na = m/z 1075.5520) (7.64 min). See also Supplemental Figures 2 to 8.

We then used mass spectrometry to confirm the presence of LCOs in the culture medium of L. bicolor and to determine their structure. Because previous analyses of LCOs have shown that these molecules are naturally produced in very low concentrations (Maillet et al., 2011; Poinsot et al., 2016), we performed the LCO analysis using the targeted mass spectrometry approach called multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. This mode is highly sensitive but requires the selection of a known LCO structure to search for its possible product ions. In this way, we detected LCOs having various lengths of chitin chains (III, IV, and V) with several classes of fatty acids (C16:0, C18:0, and C18:1) and multiple functional groups on the nonreducing end (N-methyl [N-Me] and carbamoyl [Cb]) on the reducing end (deoxyhexose, proposed as fucose [Fuc]; Figure 1B; Supplemental Table 1; see also Supplemental Figures 2 to 8). The most abundant LCOs were LCO-IV, C18:1, N-Me and LCO-III, C18:1, N-Me, Cb, Fuc. Because of the low sensitivity of high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis in complex matrices, only LCO-III, C18:1, N-Me, Cb, Fuc was visible in the positive mode, in a sodium adduct (M+Na)+ m/z 1075.5622 (calculated for C48H84N4O21Na = m/z 1075.5520; Figures 1C to 1E). We looked for sulfated forms of the major LCOs detected in the samples and found that they were less abundant than the nonsulfated form. For example, sLCO-IV, C18:1, N-Me was approximately half the intensity of nsLCO-IV, C18:1, N-Me (Supplemental Figures 7 and 8). These mass spectrometry data confirm our root hair branching results and demonstrate that the ECM basidiomycete L. bicolor produces a wide variety of both sLCOs and nsLCOs.

Both the AM Fungus Rhizophagus irregularis and Purified Symbiotic Signals Trigger Ca2+ Spiking in Populus

Given our finding that L. bicolor produces LCOs, we hypothesized that they might function as signaling molecules for communicating with a compatible host plant species such as Populus. To test this hypothesis, we first evaluated whether Populus could undergo a legume-like root hair branching response in response to both nsLCOs and sLCOs. Although neither signal induced root hair branching in Populus (Supplemental Figure 9), this finding was not surprising since, to our knowledge, root hair branching has only been reported for legumes (Lerouge et al., 1990; Heidstra et al., 1994) and actinorhizal plants (Cissoko et al., 2018), which both belong to the nitrogen-fixing clade.

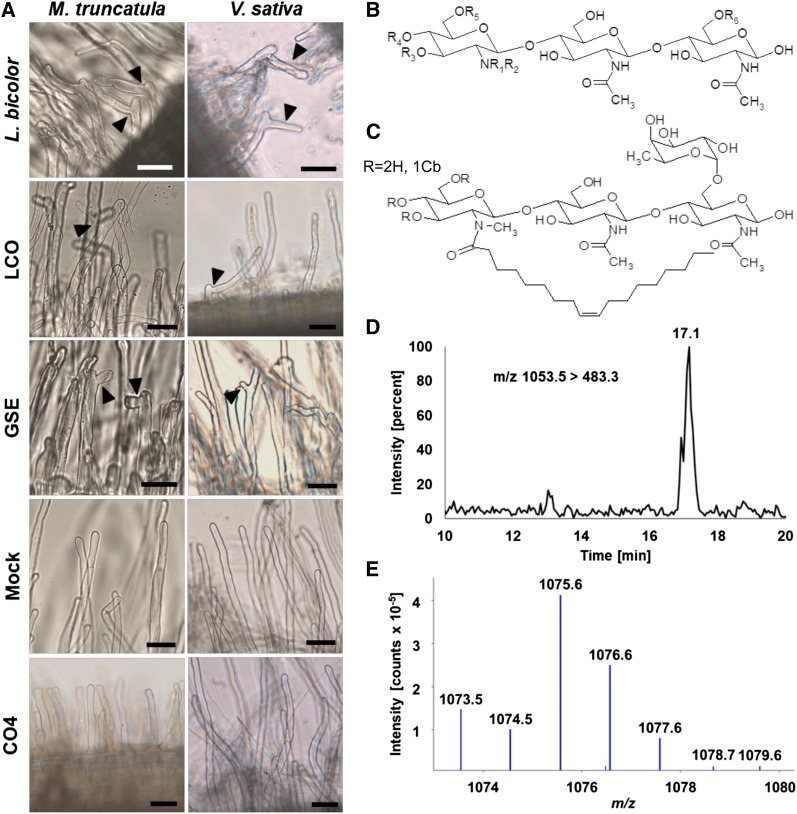

A second diagnostic plant response to LCOs is nuclear Ca2+ spiking, which has been observed not only in plants within the nitrogen-fixing clade but also in those outside of it (Sun et al., 2015). Therefore, because all of the CSP genes are conserved in the Populus genome (Garcia et al., 2015), we hypothesized that nuclear Ca2+ spiking could occur in Populus. To test this, we first used Agrobacterium rhizogenes to stably transform Populus with the coding sequence of both nuclear-localized green genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator for optical imaging (G-GECO), a Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent sensor (Zhao et al., 2011), and the Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein (DsRed; Supplemental Figure 10). Given that calcium spiking had not been reported in Populus previously, we first evaluated the ability of GSE from the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis to trigger Ca2+ spiking in atrichoblasts of lateral roots from the Populus G-GECO line. Atrichoblasts are root epidermal cells that do not develop into root hairs, in contrast to trichoblasts that do produce root hairs. We observed that GSE induced nuclear Ca2+ spiking in Populus that was comparable to that reported previously for other plant species (Figure 2; Supplemental Movie 1). As expected, no spiking occurred in mock-treated roots (Figure 2; Supplemental Movie 2). These results confirmed that nuclear Ca2+ spiking is conserved in Populus.

Figure 2.

GSEs from the AM Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis Trigger Ca2+ Spiking in Populus.

(A) Representative confocal images of fluorescing nuclei from atrichoblasts in first-order lateral roots from the Populus wild-type G-GECO line (Supplemental Figure 10). GSEs from the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis (left) induced Ca2+ spiking, but mock treatment (right) did not. Note both the elevated fluorescence of the spiking nucleus in the GSE-treated root compared with the basal fluorescence of nonspiking nuclei (see also Supplemental Movie 1) and the absence of elevated fluorescence in nuclei from the mock-treated roots (see also Supplemental Movie 2). Bars = 30 µm.

(B) Plots of Ca2+ spiking in Populus beginning at ∼20 min following application of the same treatments shown in (A). The spiking pattern is representative of that observed in at least three roots with ∼20 nuclei per root (n = 60 total nuclei). Note the characteristic Ca2+ spiking pattern in response to GSE and the absence of Ca2+ spiking in mock-treated roots.

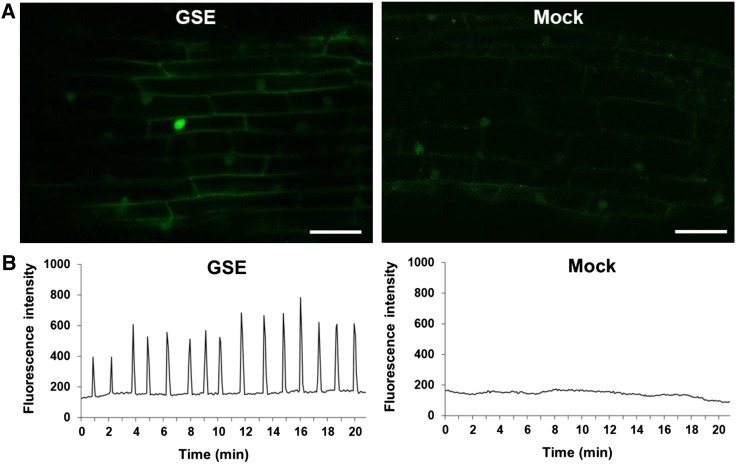

Because GSEs contain a mixture of both short-chain COs and LCOs and both signal types can trigger Ca2+ spiking in legumes and nonlegumes even in the absence of the fungus (Maillet et al., 2011; Genre et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015), we examined which of these symbiotic signals could induce Ca2+ spiking in Populus. For this experiment, we treated Populus roots with nsLCOs, sLCOs, and CO4 and observed that each of the three signals could induce Ca2+ spiking (Figures 3A and 3B; Supplemental Movies 3 to 5). To determine whether Populus has different sensitivity to these specific signals, we also evaluated the percentage of cells exhibiting Ca2+ spiking in response to all three signals at varying concentrations (10−10, 10−9, 10−8, and 10−7 M). We observed that only 3% of Populus root atrichoblasts exhibited a Ca2+ spiking response when treated with nsLCOs at 10−10 M. No spiking occurred in response to sLCO and CO4 at the same concentration. However, as the concentration of each signal type increased, so, too, did the number of spiking nuclei. In particular, Populus was more sensitive to nsLCOs than sLCOs and CO4 at 10−8 M (P-value < 0.05) but equally responsive to all three at 10−7 M (Figure 3C). Therefore, at that concentration, we calculated the average number of spikes per nuclei that were induced by each signal type using GSE as a control. We found that the average number of spikes per nucleus was comparable between the nsLCOs and GSE treatments and higher than for the sLCOs and CO4 treatments (P-value < 0.05; Figure 3D). These results indicate that nsLCOs, sLCOs and CO4 can all induce Ca2+ spiking in Populus but that the required concentration varies with each signal type. Furthermore, they suggest that Populus is more sensitive to nsLCOs than the other purified symbiotic signals tested.

Figure 3.

Symbiotic Signaling Molecules Also Cause Ca2+ Spiking in Populus.

(A) Representative confocal images of fluorescing nuclei from atrichoblasts in first-order lateral roots from the Populus wild-type G-GECO line (Supplemental Figure 10) in response to nsLCOs (10−7 M; top), sLCOs (10−7 M; middle), or CO4 (10−6 M; bottom); for all three treatments, note the elevated fluorescence of spiking nuclei compared with the basal fluorescence of nonspiking nuclei (see also Supplemental Movies 3, 4, and 5, respectively). Bars = 30 µm.

(B) Representative plots of Ca2+ spiking beginning at ∼20 min following application of the same treatments shown in (A).

(C) Percentage of spiking nuclei in Populus root atrichoblasts in response to nsLCOs, sLCOs, and CO4 at four concentrations (10−10, 10−9, 10−8, and 10−7 M). Data points represent the mean of three roots (n = 3 roots) for each treatment at each concentration, and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data from each treatment type were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups (P-value < 0.05). Note the significant increase (P-value < 0.05) in the percentage of cells with spiking nuclei at 10−8 M for the nsLCO treatment compared with the other two treatments.

(D) Average spiking frequency of all spiking nuclei from three roots in response to GSE (n = 59 spiking nuclei), nsLCOs (n = 104), sLCOs (n = 32), and CO4 (n = 92). Bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups a and b (P-value < 0.05). Note that the GSE and nsLCO treatments induced significantly higher spiking frequencies compared with the sLCO and CO4 treatments (P-value < 0.05).

Rhizophagus irregularis–Induced Ca2+ Spiking in Populus Is Dependent on CASTOR/POLLUX

To confirm that Ca2+ spiking in Populus was dependent on both CASTOR and POLLUX, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to knock down the expression of the genes encoding both proteins. Because Populus contains two copies for both CASTOR and POLLUX due to a recent whole-genome duplication (Tuskan et al., 2006), we designed two RNAi constructs: one targeting both homologs of CASTOR and the other targeting both homologs of POLLUX. Both RNAi constructs were separately introduced into Populus using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. We recovered several independent transformation events for CASTOR and POLLUX. Shoots were regenerated from calli from each of these transformation events and were propagated to establish stably transformed RNAi lines. Six CASTOR- and 11 POLLUX-RNAi lines survived and were screened via RT-qPCR to determine the degree of gene knockdown (Supplemental Figure 11). Because of high sequence similarity between CASTOR and POLLUX, we measured the expression of both genes in the top three candidates from both RNAi lines and found that the RNAi construct for CASTOR also knocked down the expression of POLLUX and vice versa (Supplemental Figure 12). This allowed us to select one RNAi line (POLLUX 201) that, compared with the wild-type Populus, had an 89% and 80% reduction in the expression of CASTOR and POLLUX, respectively (Supplemental Figure 13). We subsequently transformed this line with G-GECO. We successfully generated three independent CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO lines and used these for our Ca2+ spiking assays (Supplemental Figure 14).

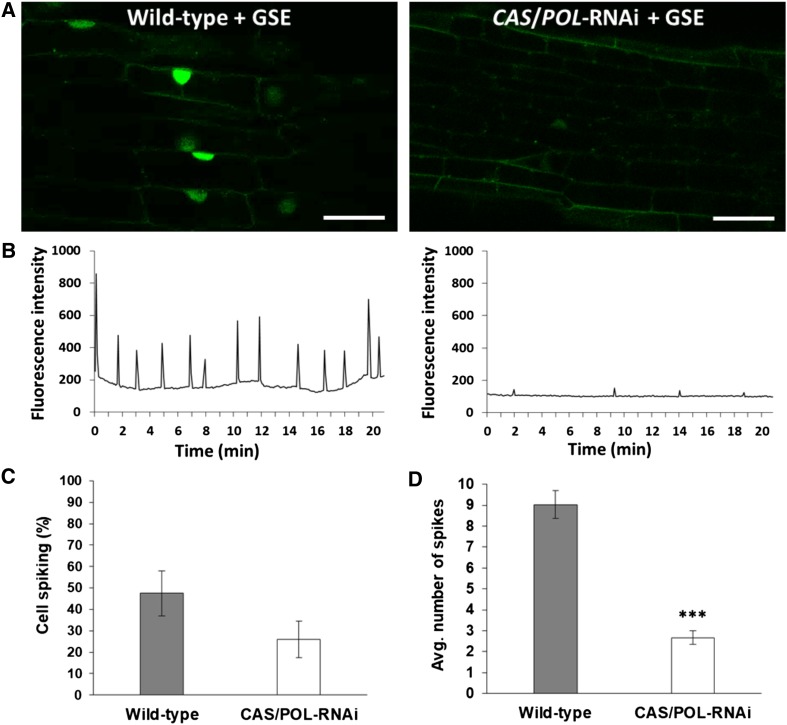

We applied GSE onto lateral roots from all three CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO lines and on the wild-type G-GECO line of Populus (Figures 4A and 4B; Supplemental Movies 6 and 7). In all three RNAi G-GECO lines, there was no change in the percentage of spiking nuclei compared with the wild-type G-GECO line (Figure 4C); however, we did see a substantial decrease in the average number of spikes (P-value < 0.001; Figure 4B). Although the spiking intensity appeared to be reduced, we could not measure this directly because G-GECO is not a ratiometric calcium sensor. Nevertheless, our results indicate that the simultaneous RNAi-mediated knockdown of both CASTOR and POLLUX was sufficient to interfere with their activity and compromise the full activation of the CSP by GSE, and they demonstrate that CASTOR and/or POLLUX contribute to Ca2+ spiking in Populus.

Figure 4.

Rhizophagus Irregularis–Induced Ca2+ Spiking in Populus Requires CASTOR and POLLUX.

(A) Representative confocal images of fluorescing nuclei from atrichoblasts in first-order lateral roots from the Populus wild-type G-GECO line (left; see Supplemental Figure 10) and the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO line (right; see Supplemental Figure 14), each in response to GSEs from Rhizophagus irregularis. Note the elevated fluorescence of the spiking nuclei in the wild-type root compared with the weakly spiking nucleus in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi root (see also Supplemental Movies 6 and 7, respectively). Bars = 30 µm. CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(B) Representative plots of Ca2+ spiking in both wild-type and all three CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi Populus G-GECO lines beginning at ∼20 min following application of GSE.

(C) Percentage of spiking nuclei in roots from both Populus genotypes (the wild type, n = 10 roots and for all three CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi lines combined, n = 13 roots). The difference between genotypes was not statistically significant (P-value = 0.12). CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(D) Average number of spikes per nucleus for both Populus genotypes (the wild type, n = 77 nuclei and CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi, n = 45 nuclei). The difference between genotypes was highly statistically significant (***P-value < 0.001). For both graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by Welch’s two-sample t test. CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

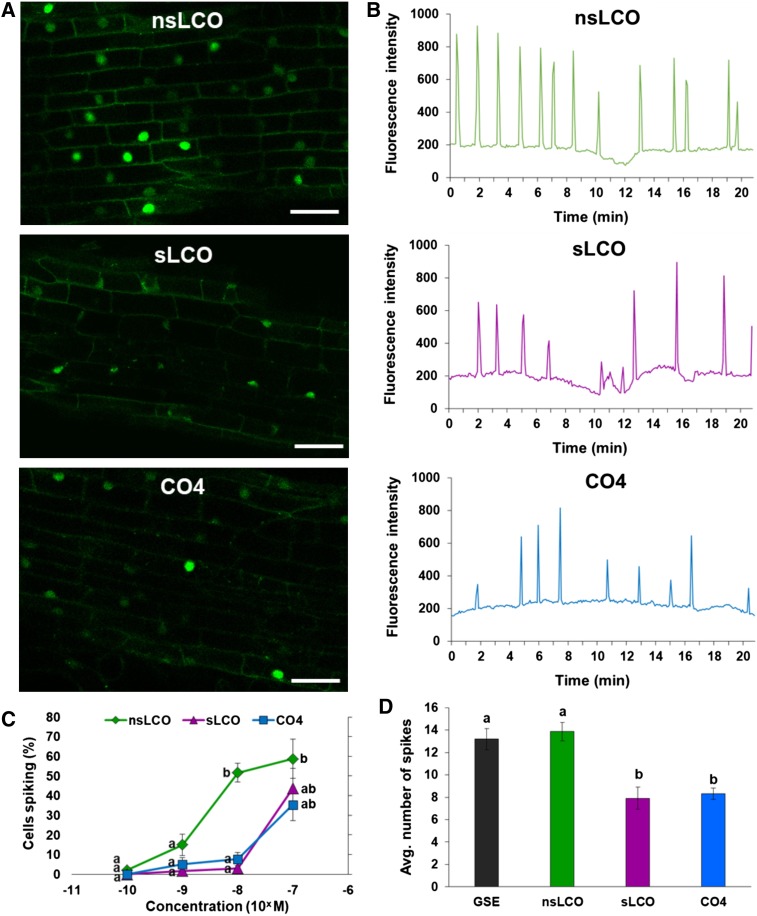

The ECM Fungus L. bicolor Triggers Ca2+ Spiking in Populus

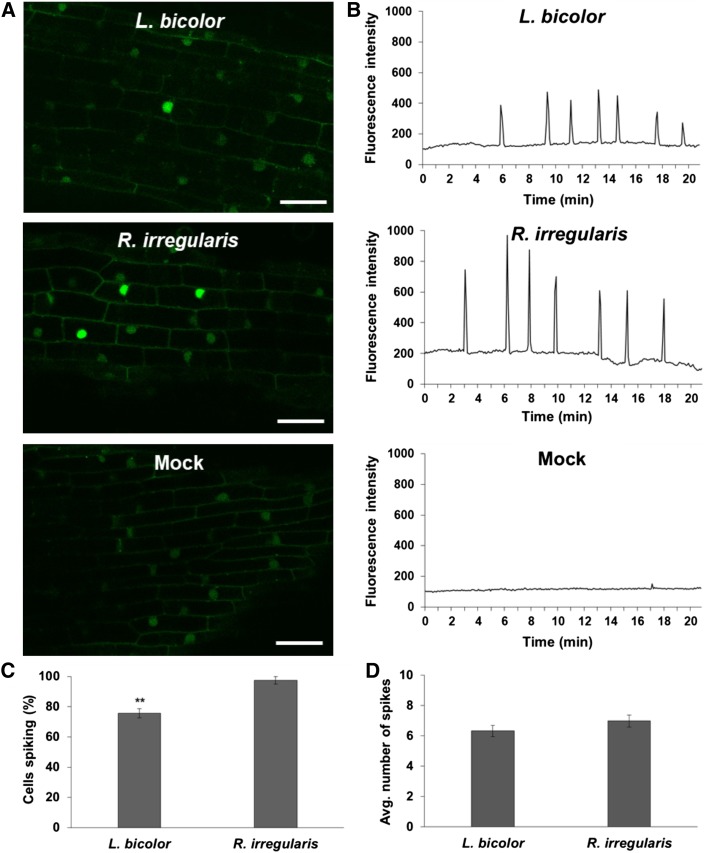

To test our hypothesis that L. bicolor can trigger Ca2+ spiking, we first applied hyphal exudates from L. bicolor on first-order lateral roots from the wild-type Populus G-GECO line. Although we observed some spiking (Supplemental Movie 8), the response was weak and irregular, perhaps because the concentration of LCOs was low. As such, we repeated the experiment with hyphal fragments of L. bicolor in order to place the hyphae in close proximity to the root and potentially elevate the concentration of LCOs. In response to this treatment, Ca2+ spiking occurred at a level comparable to the level observed in response to the GSE, while mock treatment did not induce spiking (Figures 5A and 5B; Supplemental Movies 9 to 11). The percentage of spiking nuclei in response to L. bicolor hyphae was lower than that in response to GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis (P-value < 0.01; Figure 5C); however, the frequency of spiking did not differ between both treatments (Figure 5D). These data show that an ECM fungus is capable of triggering Ca2+ spiking comparable to that induced by the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis.

Figure 5.

ECM Fungus L. Bicolor Triggers Ca2+ Spiking in Populus.

(A) Representative confocal images of fluorescing nuclei from atrichoblasts in first-order lateral roots from the Populus wild-type G-GECO line (Supplemental Figure 10) in response to hyphae from L. bicolor (top), GSEs from Rhizophagus irregularis (middle), or mock treatment (bottom). Note the elevated fluorescence of spiking nuclei in the L. bicolor and Rhizophagus irregularis treatments compared with the basal fluorescence of nonspiking nuclei and the absence of spiking nuclei in the mock treatment (see also Supplemental Movies 9, 10, and 11, respectively). Bars = 30 µm.

(B) Representative plots of Ca2+ spiking beginning at ∼20 min following application of the same treatments shown in (A).

(C) Percentage of spiking nuclei in roots of wild-type Populus in response to hyphae from L. bicolor (n = 4 roots) and GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis (n = 3 roots). The difference between treatments was statistically significant (**P-value < 0.01).

(D) Average spiking frequency of nuclei from the same roots in response to hyphae from L. bicolor (n = 90 nuclei) and GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis (n = 65 nuclei). The difference between treatments was not statistically significant. For both graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by Welch’s two-sample t test.

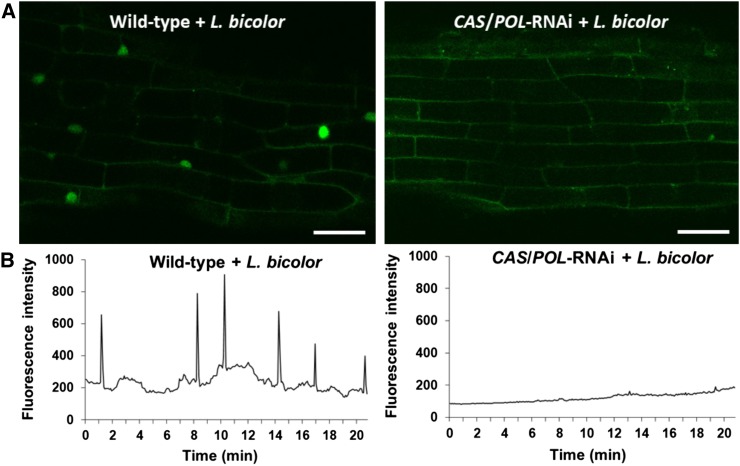

Given that Ca2+ spiking induced by GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis was dependent on CASTOR and/or POLLUX, we hypothesized that Ca2+ spiking caused by L. bicolor hyphae would be as well. To confirm this, we applied L. bicolor hyphae or exudates onto lateral roots from all three CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO lines and onto the wild-type G-GECO Populus as a positive control. Ca2+ was not detected in any CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO roots but was observed in the wild-type G-GECO roots (Figure 6; Supplemental Movies 12 to 14). Based on these results, we concluded that Ca2+ spiking in Populus induced by L. bicolor hyphal fragments is also dependent on CASTOR and/or POLLUX.

Figure 6.

Laccaria Bicolor–Induced Ca2+ Spiking in Populus Requires CASTOR and POLLUX.

(A) Representative confocal images of fluorescing nuclei from atrichoblasts in first-order lateral roots from the Populus wild-type G-GECO line (left; see Supplemental Figure 10) and the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi G-GECO line (right; see Supplemental Figure 14), each in response to hyphal fragments of L. bicolor. Note the elevated fluorescence of the spiking nuclei in the wild-type root compared with the absence of spiking nuclei in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi root (see also Supplemental Movies 12 and 13, respectively). Bars = 30 µm. CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(B) Representative plots of Ca2+ spiking in both wild-type and all three CAS/POL-RNAi Populus lines beginning at ∼20 min following application of hyphal fragments. The spiking pattern is representative of that observed in at least three roots with ∼20 nuclei per root (n = 60 nuclei). CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

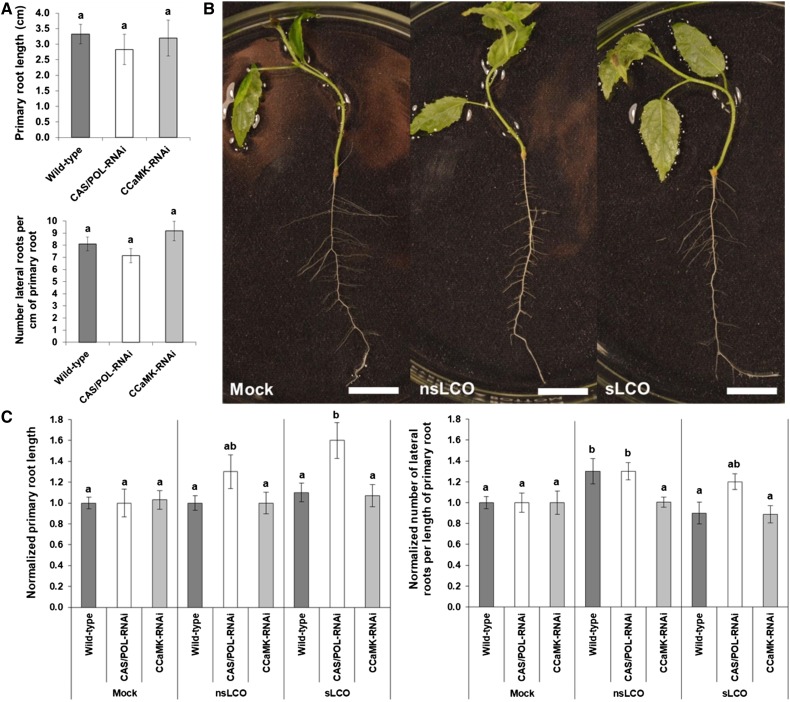

LCOs Affect Populus Root Development

Since LCOs from AM fungi enhance lateral root formation in other plant species (Oláh et al., 2005; Gutjahr et al., 2009; Maillet et al., 2011; Mukherjee and Ané, 2011; Sun et al., 2015), we hypothesized that the previously observed enhancement of lateral root development in Populus by L. bicolor (Felten et al., 2009) can partially be attributed to the production of LCOs by L. bicolor. Furthermore, we hypothesized that if LCOs enhance lateral development in Populus, the enhancement would be dependent on the CSP. To test these hypotheses, we used the wild-type Populus, the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line, and a CCaMK-RNAi line that we developed with 83% reduction in CCaMK expression compared with the wild-type Populus line (Supplemental Figures 11 and 13). Before treating all three Populus lines with LCOs, we first confirmed that native primary and lateral root development was unchanged in the transgenic RNAi lines compared with the wild type (Figure 7A). Next, we treated all three Populus lines with mock, purified nsLCOs, or sLCOs and observed their effect on both primary and lateral root development (Figures 7B and 7C). Primary root length was the same for all of the Populus lines regardless of treatment, except for an increase (P-value < 0.05) in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line when treated with sLCOs. For lateral root development, in response to nsLCOs, the number of lateral roots per length of primary root increased in both the wild-type and CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi lines (P-value < 0.05), whereas the CCaMK-RNAi line was nonresponsive to all of the treatments. These data suggest that LCOs affect root development in Populus in a CSP-dependent manner and that L. bicolor may use nsLCOs as a signal to trigger an increase in lateral root development independent of CASTOR/POLLUX but dependent on CCaMK, thereby potentially maximizing root surface area for subsequent colonization.

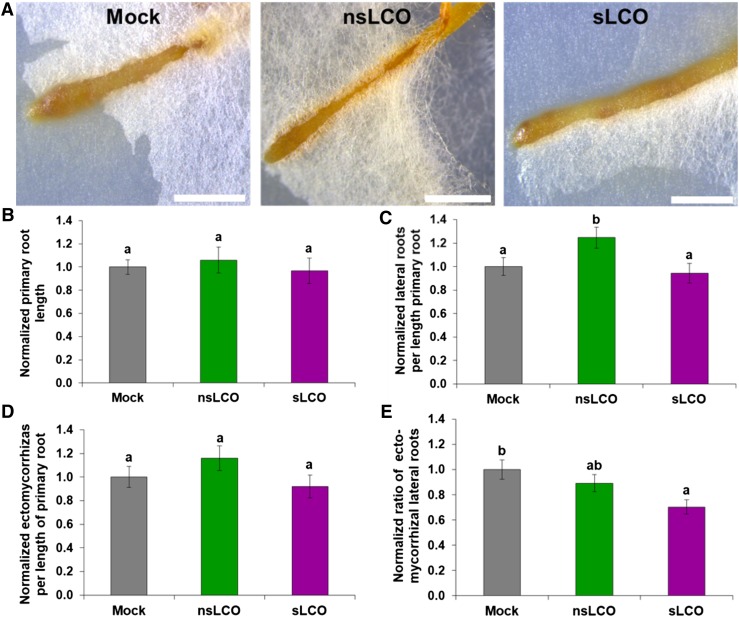

Figure 7.

Primary and Lateral Root Development in the Wild-Type, CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi, and CCaMK-RNAi Populus Lines Treated with LCOs.

(A) Normalized primary root length (top) and normalized number of lateral roots per unit length of primary root (bottom) in the wild-type (n = 40 roots), CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi (n = 38 roots), and CCaMK-RNAi (n = 38 roots) Populus lines (Supplemental Figure 13). CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(B) Representative images of wild-type Populus in response to mock treatment (left), nsLCOs (middle), and sLCOs (right). Bars = 1 cm.

(C) Summary of normalized primary root length (left) and normalized number of lateral roots per length of primary root (right) for the wild-type (n = 28, 19, or 16 roots), CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi (n = 19, 19, or 16 roots), and CCaMK-RNAi (n = 15, 16, or 18 roots) Populus lines in response to one of three treatments: mock, nsLCOs (10−8 M), or sLCOs (10−8 M), respectively. For all graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups a and b (P-value < 0.05). Note that for primary root length, sLCOs induced an increase in only the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line (P-value < 0.05); and for the number of lateral roots per length of primary root, nsLCOs induced an increase in both the wild-type and CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi lines (P-value < 0.05). CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

Application of LCOs Enhances ECM Colonization in Populus

After discovering that AM fungi produce LCOs, Maillet et al. (2011) also found that the addition of LCOs significantly enhanced AM colonization in M. truncatula. We therefore hypothesized that the application of LCOs could also increase the colonization of Populus by L. bicolor. To test this hypothesis, we treated established Populus roots with purified nsLCOs or sLCOs and subsequently cocultured them with L. bicolor using a well-established sandwich system (Felten et al., 2009). As a negative control, we cocultured mock-treated Populus roots as well. After 3 weeks of colonization, we harvested the ECM root systems of all treated plants and used a stereomicroscope to observe external mantle formation. However, we did not find any noticeable effect of LCOs (Figure 8A). We also did not see any alteration in primary root length among treatments (Figure 8B), but, as with the previous lateral root experiment, nsLCOs again induced an increase in the number of lateral roots per length of the primary root compared with mock treatment (P value < 0.05; Figure 8C). Surprisingly, this did not result in a significant increase in the number of ECM lateral roots (Figure 8D). Compared with the mock treatment, we saw a decrease (P value < 0.05) in the ratio of ECM lateral roots to the total number of lateral roots in the sLCO treatment (Figure 8E). These results indicate that nsLCOs induce an increase in lateral root formation even in the presence of the fungus.

Figure 8.

Effect of LCOs on Both Lateral Root and Ectomycorrhiza Formation during L. Bicolor Colonization.

(A) Representative stereomicroscope images of the wild-type Populus roots treated with mock (left), nsLCOs (10−8 M; middle), or sLCOs (10−8 M; right) and subsequently cocultured with hyphae of L. bicolor for 3 weeks. Bars = 1 mm.

(B) to (E) Summary plots of normalized data for root development and ectomycorrhiza formation in response to mock (n = 17 roots), nsLCOs (n = 15 roots), and sLCOs (n = 15 roots), including primary root length (B), number of lateral roots per length of primary root (C), number of ectomycorrhizas per length of primary root (D), and the ratio of ectomycorrhizas per number of lateral roots (E). Note that compared with mock treatment, nsLCOs induced an increase in the number of lateral roots per length of primary root (P-value < 0.05), while sLCOs induced a decrease in the ratio of ectomycorrhizas to total lateral roots (P-value < 0.05). For all graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups a and b (P-value < 0.05).

To identify other potential effects of LCOs, we analyzed in more detail a subset of 20 ECM lateral roots per treatment using confocal microscopy. Using a vibratome, we generated ten 50-µm cross sections from each ectomycorrhiza and then stained the fungal tissue with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 to stain the fungal cell wall and the plant tissue with propidium iodide to stain the plant cell wall (Figure 9A). Following confocal imaging of entire cross sections, we evaluated four parameters: mantle width, root diameter, Hartig net boundary, and root circumference. Based on these measurements, we calculated the ratio of mantle width to root diameter (Figure 9B) and the ratio of Hartig net boundary to root circumference (Figure 9C). Compared with the mock treatment, sLCOs induced a 15 and 8% increase in both ratios, respectively (P-value < 0.05; Figures 9B and 9C). These results suggest that exogenous application of sLCOs, but not nsLCOs, enhances ECM colonization in Populus.

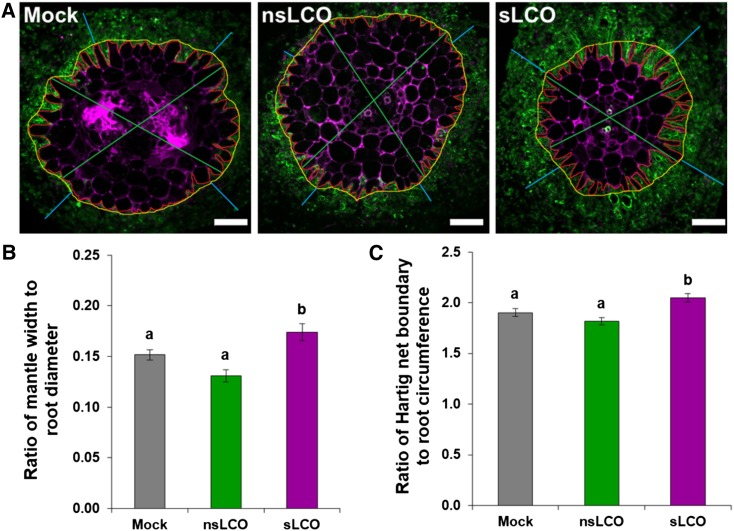

Figure 9.

Effect of LCOs on Both Mantle and Hartig Net Formation during L. bicolor Colonization.

(A) Representative transverse cross sections of Populus roots treated with mock (left), nsLCOs (10−8 M; middle), or sLCOs (10−8 M; right) and cocultured with L. bicolor for 3 weeks. Colonized roots were sectioned and stained with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and propidium iodide (purple) and imaged on a confocal laser scanning microscope. For each image, four types of measurements were obtained using ImageJ, including mantle width (light blue), root diameter (green), Hartig net boundary (red), and root circumference (yellow). These measurements were used to calculate both the ratio of average mantle width to average root diameter and average Hartig net boundary to average root circumference. Bars = 50 µm.

(B) and (C) Summary plots of the ratios of both mantle width to root diameter (B) and Hartig net boundary to root circumference (C). These data revealed that sLCOs (n = 109 root cross sections), but not nsLCOs (n = 77), induced an increase (P-value < 0.05) in ECM colonization compared with the mock treatment (n = 111). For both graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups a and b (P-value < 0.05). Note that compared with the other two treatments, sLCOs induced a statistically significant increase (P-value < 0.05) in both ratios, indicating an increase ECM colonization.

Laccaria bicolor Uses the CSP to Colonize Populus

Based on our previous data, we hypothesized that L. bicolor could use the CSP to colonize Populus roots. To test this, we cocultured both the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi and CCaMK-RNAi Populus lines with L. bicolor. We also cocultured the wild-type Populus with L. bicolor as a control (Figure 10A). After 3 weeks, we harvested, prepared, and observed cross sections of ECM roots (Figure 10B). This allowed us to analyze the same colonization parameters as described for the previous experiment (Figures 10C and 10D). The ratio of mantle width to root diameter in the CCaMK-RNAi line decreased by 24% compared with the wild-type Populus (P value < 0.05); this decrease did not occur in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line (Figure 10C). However, the ratio of Hartig net boundary to root circumference decreased by 15 and 16%, respectively, in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi and CCaMK-RNAi lines compared with the wild type (P value < 0.05; Figure 10D). These results confirmed our hypothesis and clearly illustrate that the ECM fungus L. bicolor uses CCaMK for the full establishment of the mantle and both CCaMK and CASTOR/POLLUX for Hartig net development during the colonization of Populus.

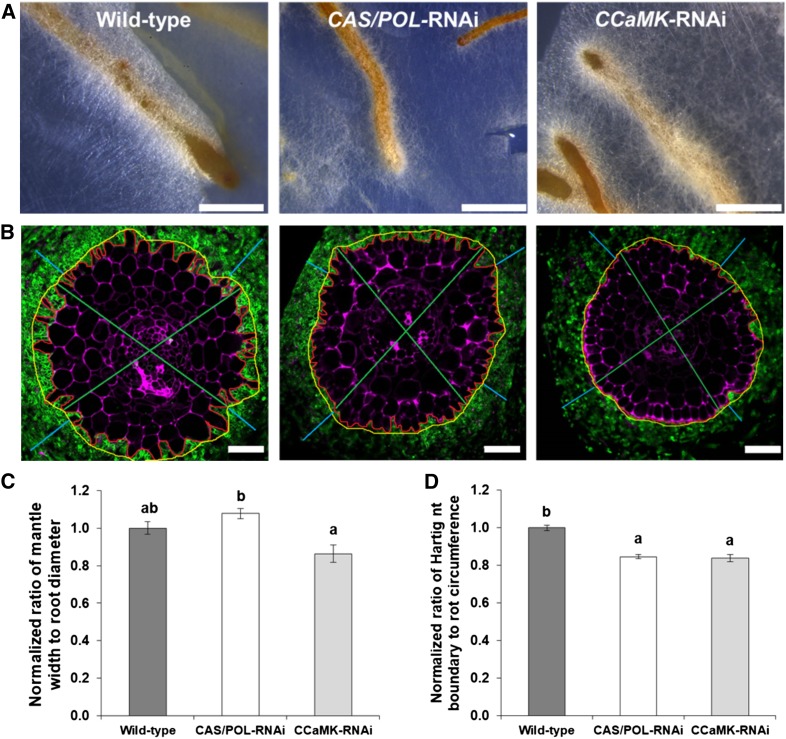

Figure 10.

Role of the CSP in the Colonization of Populus by the ECM Fungus L. bicolor.

(A) Representative stereomicroscope images of the wild-type (left), CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi (middle), and CCaMK-RNAi Populus (right) roots (Supplemental Figure 13) cocultured with L. bicolor for 3 weeks. Bars = 1 mm. CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(B) Representative transverse cross sections of the wild-type (left), CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi (middle), and CCaMK-RNAi (right) Populus roots cocultured with L. bicolor. Colonized roots were sectioned and stained with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and propidium iodide (purple) and imaged on a confocal laser scanning microscope. For each image, four types of measurements were obtained using ImageJ, including mantle width (light blue), root diameter (green), Hartig net boundary (red), and root circumference (yellow). These measurements were used to calculate both the ratio of average mantle width to average root diameter and average Hartig net boundary to average root circumference. Bars = 50 µm. CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

(C) and (D) Summary plots of the normalized ratios of mantle width to root diameter (C) and Hartig net boundary to root circumference (D) in the wild-type (n = 240 root cross sections), CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi (n = 173), and CCaMK-RNAi Populus (n = 149) lines. Compared with the wild-type line, both ratios were lower in the CCaMK-RNAi line, whereas only the ratio of Hartig net boundary to root circumference was lower in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line (P-value < 0.05). For both graphs, bars represent the mean of the data and error bars represent the se of the mean. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA (see Supplemental File 1) with Tukey pairwise comparison to assign significance groups a and b (P-value < 0.05). Note that compared with the wild-type line, both ratios were lower in the CCaMK-RNAi line, whereas only the ratio of Hartig net boundary to root circumference was lower in the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi line (P-value < 0.05). CAS, CASTOR; POL, POLLUX.

DISCUSSION

Our work demonstrated that the ECM fungus L. bicolor produces an array of both nsLCOs and sLCOs (Figure 1). We also showed that L. bicolor triggers Ca2+ spiking in Populus comparable to the spiking induced by GSE from the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis (Figures 2 and 5). The Ca2+ spiking response in Populus to both AM and ECM fungi was dependent on CASTOR/POLLUX as has been observed in both legumes and rice (Oryza sativa; Figures 4 and 6; Peiter et al., 2007; Charpentier et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2015). Interestingly, we found that, in terms of Ca2+ spiking, Populus is more sensitive and responsive to nsLCOs than to either sLCOs or CO4 (Figure 3). Furthermore, nsLCOs enhanced Populus lateral root development in a CCaMK-dependent manner as observed in M. truncatula and rice; but in contrast to M. truncatula and rice (Maillet et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2015), the response of Populus is CASTOR/POLLUX independent (Figure 7). Even in the presence of the fungus, nsLCOs induced an increase in lateral root formation, but this did not result in a significant increase in the ratio of ectomycorrhizas formed (Figure 8). Although the application of sLCOs caused a decrease in the ratio of mycorrhizas developed by L. bicolor on Populus roots (Figure 8), sLCOs still stimulated a slight increase in mantle and Hartig net formation (Figure 9). Interestingly, the colonization of M. truncatula by Rhizophagus irregularis was also moderately increased by the application of LCOs (Maillet et al., 2011). Finally, we showed that L. bicolor uses CCaMK for the full establishment of the mantle and both CCaMK and CASTOR/POLLUX for complete Hartig net development during the colonization of Populus roots (Figure 10). This provides solid evidence that the CSP is used by the ECM fungus L. bicolor to colonize its host plant.

Laccaria bicolor Produces a Suite of LCOs with Unique Functions

Although several substitutions on LCOs differ between Rhizophagus irregularis and L. bicolor, both mycorrhizal fungi produce a mixture of sLCOs and nsLCOs (Maillet et al., 2011). Different structures of LCOs are more active at different steps of the Populus–L. bicolor association. Purified nsLCOs induce Ca2+ spiking at lower concentrations than sLCOs and enhance lateral root development, while sLCOs did not. Reciprocally, purified sLCOs enhanced ECM colonization, but nsLCOs did not. The roles of different LCO structures at various stages of the symbiotic associations have been well described in the rhizobia–legume symbiosis. For instance, Sinorhizobium meliloti produces LCOs O-acetylated and N-acylated by C16-unsaturated fatty acids that are required for infection thread formation and nodule organogenesis. Double mutants of nodF and nodL produce LCOs with saturated fatty acids and that lack the O-acetyl substitution at the nonreducing end. An S. meliloti nodF/L mutant can elicit root hair curling and initiate nodule organogenesis, but it is unable to initiate infection threads. This indicates that different structured LCOs are required for different stages of the symbiotic association. These observations led to the hypothesis that different receptor complexes that recognize different LCO structures may control different steps of the symbiotic association (Ardourel et al., 1995). Given the effect of different LCO structures on lateral root development and ECM colonization, we speculate that in Populus different LCO receptor complexes may control lateral root formation and ECM colonization in response to fungal signals. In future studies, it would be interesting to develop L. bicolor mutants that produce specific types of LCOs to dissect the role of different LCO receptor complexes at various stages of the ECM association.

Ca2+ Spiking Is Conserved in Populus and Is Induced by both AM and ECM Fungi

Observing Ca2+ spiking in vivo requires the injection of Ca2+-sensitive dyes or the expression of Ca2+ sensors (Ehrhardt et al., 1996; Krebs et al., 2012). For the past decade, the most commonly used sensor for observing Ca2+ spiking was the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)–based yellow cameleon protein YC3.6 or one of its progenitors (Capoen et al., 2011; Krebs et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015; Venkateshwaran et al., 2015). However, another class of genetically encoded, non–FRET-based, Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent sensors known as GECO were recently developed (Zhao et al., 2011). When compared with FRET-based sensors, based on the signal-to-noise ratio, the dynamic response of GECO is far superior, thus allowing GECO to detect symbiosis-related variations in Ca2+ spiking with higher sensitivity (Kelner et al., 2018). As such, we used a nucleus-localized G-GECO to monitor Ca2+ spiking in the nuclei of epidermal cells from Populus lateral roots treated with symbiotic signals.

Previous studies have reported that Ca2+ spiking responses can differ in trichoblasts and atrichoblasts depending on the signal applied (Chabaud et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2015). In this study, we focused our analysis on atrichoblasts because ECM fungi invaginate between epidermal and cortical cells to form the Hartig net. As such, root hairs do not play a direct role during or after the ECM colonization process; in fact, they are suppressed by ECM formation (Nehls, 2008). Nevertheless, while conducting our study, we did observe some Ca2+ spiking in the nuclei of trichoblasts (Supplemental Movie 13). Because this was not the focus of our research, we did not pursue this further.

We showed that Ca2+ spiking occurs in Populus in response to both GSE from the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis and to purified signals present in GSEs (e.g., LCOs and CO4). Interestingly, we observed that the percentage of spiking nuclei in Populus root atrichoblasts was concentration dependent when compared among treatments. Notably, in response to 10−8 M nsLCOs, the percentage of spiking nuclei was significantly higher than the response to sLCOs and CO4 at the same concentration. Similarly, the spiking frequency was significantly lower in the CO4 and sLCOs treatments compared with nsLCOs. These two findings suggest that Populus is both more sensitive and responsive to nsLCOs. By contrast, nsLCOs and CO4 were less active than sLCOs to initiate Ca2+ spiking in lateral roots from M. truncatula (Sun et al., 2015). Also, nsLCOs and CO4 were less active than sLCOs to initiate Ca2+ spiking in lateral roots from M. truncatula (Sun et al., 2015). In that study, spiking in response to nsLCOs and CO4 was first observed at a concentration of 10−8 M with a maximum response at 10−6 M, while sLCO spiking began at 10−13 M but plateaued at 10−9 M. This observation is not surprising given that the LCOs produced by S. meliloti—the rhizobial symbiont for M. truncatula—are sulfated (Truchet et al., 1991). In contrast to M. truncatula, Ca2+ spiking in rice occurred primarily in response to CO4, but not at all in response to LCOs (Sun et al., 2015). Combined with these previous finding, our data confirm that different plants respond to and require different signals for the activation of the CSP.

To our knowledge, our work provides the first observation of Ca2+ spiking inhibition through RNAi knockdown of CASTOR and POLLUX as opposed to through the use of mutants. Previous studies with other plant species were based on mutants with complete knockouts of genes required for Ca2+ spiking (Charpentier et al., 2008, 2016; Capoen et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2015). At the time we began this study, this was not an option in Populus due to the difficulty of obtaining mutant lines. Regardless, we still observed a significant decrease in both spiking frequency and perhaps intensity in response to GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis.

In testing the induction of nuclear Ca2+ spiking in Populus by L. bicolor, we first applied the same hyphal exudates as for the root hair branching assays. However, as we observed with the root hair branching assays, the relative concentration of LCOs in the exudates is likely very low and therefore the number of spiking nuclei and spiking frequency were minimal, but still detectable (Supplemental Movie 8). In an attempt to observe an elevated calcium spiking response, we placed Populus roots in a suspension of L. bicolor hyphal segments that did not inhibit the observation of Ca2+ in root atrichoblasts (Supplemental Movies 8, 11, and 12). This technique was the best method for the question we wanted to address and allowed us to observe the expected Ca2+ spiking response to LCOs produced by L. bicolor; however, there are some limitations to the approach we used. For example, we cannot rule out that the Ca2+ spiking we observed was caused by chitin fragments released during the fragmentation of the fungal hyphae. In future studies, a similar system to the one described in Chabaud et al. (2011) could be developed that would allow for the observation of in vivo contact of Populus roots with intact L. bicolor hyphae. Using this method, one could observe true hyphal-induced Ca2+ spiking in Populus roots.

LCOs Enhance Lateral Root Development across Species but with Variable Dependence on Components of the CSP

Increased lateral root development is a well-documented response to both AM and ECM fungi (Gutjahr and Paszkowski, 2013; Sukumar et al., 2013; Fusconi, 2014). In response to AM fungal spores from Gigaspora margarita, increased lateral root development in M. truncatula was dependent on DMI1/POLLUX and SYMRK, but not CCaMK (Oláh et al., 2005). Identical results were obtained with GSE from Rhizophagus irregularis (Mukherjee and Ané, 2011). In rice, Rhizophagus irregularis induced an increase in lateral root development independent of the CSP (Gutjahr et al., 2009). Again, identical results were observed in response to GSE (Mukherjee and Ané, 2011). However, nsLCOs and sLCOs increased lateral root formation in M. truncatula, and this response was entirely dependent not only on DMI1/POLLUX and SYMRK, but also CCaMK (Maillet et al., 2011). Both nsLCOs and sLCOs, as well as CO4, enhanced lateral root formation in rice, and this response to purified signals was dependent on CCaMK (Sun et al., 2015). Based on these results, enhanced lateral root formation occurs in both M. truncatula and rice in response to AM fungal colonization, application of spores or GSE, and purified signals (COs and LCOs). However, the dependence of these responses on components of the CSP varies by species and by treatment. In our Populus experiment, we found that lateral root development was affected by nsLCOs and that this was dependent on CCaMK, but not CASTOR/POLLUX. Surprisingly, the CASTOR/POLLUX-RNAi lines exhibited an enhanced response to LCOs in both primary root length and lateral root development, which were not observed before in other species using mutants.

Interactions between ethylene and auxin are required for lateral root development in multiple plant species (Ivanchenko et al., 2008; Negi et al., 2010). ECM fungi take advantage of this conserved mechanism of hormone balance and manipulate root morphology in various tree species by producing ethylene and auxin (Rupp and Mudge, 1985; Rupp et al., 1989; Karabaghli-Degron et al., 1998; Felten et al., 2009, 2010; Splivallo et al., 2009; Vayssières et al., 2015). Our findings indicate that manipulating hormone balance is not the only mechanism that is used by L. bicolor to affect root architecture. Similar to AM fungi (Oláh et al., 2005), L. bicolor also produces LCOs to stimulate an increase in lateral root formation and thereby maximizes the root surface area available for colonization.

The CSP Is Likely Not Used for All ECM Associations

AM colonization assays have traditionally been performed with plant mutants to evaluate the role of the core CSP genes in the colonization process (Stracke et al., 2002; Ané et al., 2004; Lévy et al., 2004). Because mutant lines in Populus were unavailable when we started this study, the best method for manipulating Populus gene expression was RNAi. This method was used previously to knock down the expression of CCaMK in tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata), resulting in a decrease in AM colonization (Groten et al., 2015). Using RNAi in Populus, we generated RNAi lines targeting CASTOR, POLLUX, and CCaMK with 89%, 80%, and 83% knockdown, respectively, compared with the wild-type Populus. Because of the time and cost of producing transgenic Populus, we did not generate an empty-vector control line but instead used the wild-type poplar since its root development did not differ from the RNAi lines (Figure 7A). Compared with the wild-type, the CASTOR/POLLUX- and CCaMK-RNAi lines exhibited a decrease in colonization with both the AM fungus Rhizophagus irregularis (Supplemental Figure 15) and the ECM fungus L. bicolor (Figure 10), further demonstrating that RNAi is a useful tool for evaluating the role of genes involved in plant–microbe interactions. However, the degree of inhibition in the RNAi lines was higher for AM colonization than for ECM colonization, especially in the CCaMK-RNAi line. There are multiple explanations for this observation. A previous study of genes involved in AM symbiosis revealed that high-density inoculum partially overcame the mutant phenotype of multiple CSP genes (Morandi et al., 2005). In our study, we used the well-established sandwich system (Felten et al., 2009), which allows for the uniform formation of multiple ectomycorrhizas on the same root system. This method of inoculation exposes plant roots to a density of ECM hyphae that exceeds that present in nature. As such, the expected phenotype of reduced colonization may have been somewhat masked by the ability of high-density inoculum to overcome the knock down of the CSP genes partially. Regardless, colonization was reduced in the RNAi lines compared with the wild-type control, thus demonstrating that L. bicolor uses the CSP to colonize Populus.

Our observation that the CSP plays a role in the establishment of the Populus–L. bicolor association is probably not a general rule for all ECM associations. Many genes of the CSP are absent in the genome of pine (Pinus pinaster; Garcia et al., 2015), a host plant for the ECM fungus H. cylindrosporum. In support of this, the addition of LCOs on roots of P. pinaster did not affect lateral root development, suggesting that P. pinaster may be incapable of perceiving or responding to LCOs (Supplemental Figure 16). Moreover, the coculture of LCO-treated P. pinaster roots with H. cylindrosporum did not affect the number of ectomycorrhizas that were formed (Supplemental Figure 17). Because L. bicolor produces LCOs and requires the CSP for full colonization of Populus, it would be interesting to test whether L. bicolor colonization of a host plant that lacks the CSP, for example, Norway spruce (Picea abies), is increased with the application of LCOs (Karabaghli-Degron et al., 1998; Garcia et al., 2015). Furthermore, the presence of LCOs in L. bicolor raises the question of whether other ECM fungal species also produce LCOs and potentially use them to activate the CSP as part of their mechanisms for plant colonization. The methods described in this article could serve as a platform for future studies in evaluating the presence of LCOs in other species of ECM fungi and evaluating their role during the colonization of compatible host plants.

Some Molecular Mechanisms Required for Individual ECM Associations Are Likely Species Specific

Fossil evidence and molecular studies suggest a single origin for AM symbioses (Brundrett, 2002; Delaux et al., 2014; Bravo et al., 2016). However, phylogenetic studies with ECM fungi suggest that ECM symbioses evolved independently in 78 to 82 fungal lineages (Tedersoo and Smith, 2013; Martin et al., 2016; Hoeksema et al., 2018). It is therefore very likely that the molecular mechanisms required for one ECM fungus to colonize one plant species would differ from those required by the same fungus to colonize another plant species. As evidence of this, in addition to a core regulon, a variable gene regulon was identified in L. bicolor during the colonization of two distinct host plants, black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga mensiezii; Plett et al., 2015). Furthermore, another study that compared the transcriptome of both extraradical mycelium and hyphae derived from mature ectomycorrhizas from 13 ECM fungal species found that some groups of genes based on gene ontology were similarly regulated (Kohler and Mycorrhizal Genomics Initiative Consortium et al., 2015). However, symbiosis-induced genes were mostly restricted to individual species. Even two ECM species of Laccaria that diverged ∼20 million years ago only shared one-third of Laccaria symbiosis-induced orphan genes. This observation suggests that even after the evolution of the ECM lifestyle within a genus, individual species diverged and developed their own set of symbiosis-specific proteins (Kohler and Mycorrhizal Genomics Initiative Consortium et al., 2015; Hoeksema et al., 2018).

It is also likely that host-specific responses may be related to the production of small secreted proteins (SSPs). In L. bicolor, two mycorrhiza-induced (Mi)SSPs have been characterized, MiSSP7 and MiSSP8, and both function as effectors in the host plant Populus (Plett et al., 2011; Pellegrin et al., 2017). The expression of MiSSP7 is induced by the plant-derived flavonoid rutin and modulates jasmonic acid signaling (Plett and Martin, 2012; Plett et al., 2014). Populus also releases SSPs that enter ECM hyphae and alter their growth and morphology (Plett et al., 2017). All of these findings combined with ours provide a complete view of how the Populus–L. bicolor association forms. However, a significant amount of research is still necessary to determine how many ECM fungi produce LCOs and whether they use them like L. bicolor to colonize their host plants via activation of the CSP. If they do, then the CSP should be considered as more common than previously thought in regulating not only the rhizobia–legume, Frankia–actinorhizal, and AM symbioses but also relevant ECM symbioses.

METHODS

Plant Material and Culture

We used seeds from Medicago truncatula Jemalong A17 and Vicia sativa (L.A. Hearne) for the root hair branching experiments and hybrid Populus (Populus tremula × Populus alba clone INRA 717-1-B4) for all other experiments. The M. truncatula seeds were acid scarified for 12 min in full-strength H2SO4, sterilized with 8.25% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite, rinsed thoroughly with sterile water, and imbibed for 24 h. Imbibed seeds were placed on 1% agar (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1 µM gibberellic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and placed at 4°C for 3 d to synchronize germination. The seeds were then germinated at room temperature (25°C) for up 1 d. The V. sativa seeds were surface sterilized with 2.4% (w/v) calcium hypochlorite for 2 min, rinsed three times with sterile water, and then soaked for 4 h. Imbibed seeds were placed on moist germination paper (38 lb, Anchor Paper) on 1% agar (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1 µM gibberellic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and placed at 4°C for 7 d to synchronize germination. The seeds were then germinated at room temperature (25°C) for up to 4 d. Fully germinated M. truncatula and V. sativa seeds were plated on moist germination paper on Fahraeus medium (Fåhraeus, 1957) supplemented with 0.1 µM 2-aminoethoxyvinyl glycine (Sigma-Aldrich). Populus plants were maintained in axenic conditions using Lloyd and McCown’s woody plant medium (2.48 g L−1 basal salts [Caisson Labs] supplemented with 5 mM NH4NO3, 2.5 mM Ca(NO3)2 · 4 H2O, 3 µM d-gluconic acid calcium salt, 20 g L−1 Suc, pH 5.6, 3.5 g L−1 agar, and 1.3 g L−1 Gelrite) and grown in glass bottles (6 × 10 cm) sealed with Magenta B-caps (Sigma-Aldrich). Unless indicated otherwise, for all Populus experiments, 3-cm terminal cuttings were taken from 4-week-old Populus plants and rooted for 1 week in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with vitamins (Caisson Labs) supplemented with 10 µM indole-3-butyric acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All plants were grown in a growth chamber (Conviron PGC Flex) set to 25°C with a 16-h day/8-h night photoperiod and ∼100 µmol m−2 s−1 of light provided by fluorescent bulbs (Phillips Silhouette High Output F54T5/841).

Fungal Material and Culture

GSEs from Rhizophagus irregularis DAOM 197198 (Premier Tech Biotechnologies) were prepared using ∼4000 spores mL−1 as described previously by Mukherjee and Ané (2011). The L. bicolor strain S238N obtained from Francis Martin (INRA, Nancy, France) was maintained on Pachlewski P05 medium (Müller et al., 2013) with 2% agar (w/v) at 25°C in the dark. For the root hair branching assays, hyphal exudates from L. bicolor were obtained as follows: 9 × 9-cm sheets of cellophane were boiled in 1 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h, rinsed three times with milli-Q water, and then autoclaved for 1 h while immersed in water. The cellophane sheets were then placed on Pachlewski P20 medium (Müller et al., 2013) with 2% agar (w/v). Nine 8-mm plugs of L. bicolor were placed on the cellophane in positions equidistant from one another. After incubation for ∼2 weeks, fungal hyphae covered the surface of the cellophane which was then floated on 30 mL of sterile milli-Q water in a square Petri dish (9 cm × 9 cm) and incubated for 3 d. Hyphal exudates were then collected by pouring off the liquid from multiple plates and concentrating it to 10% of the original volume using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated exudates were then stored at −20°C and thawed as needed for the root hair branching experiments. For Ca2+ spiking assays, L. bicolor hyphae from liquid cultures grown for 2 months in 50 mL of Pachlewski P05 broth were rinsed with sterile water three times. The hyphae were then resuspended in 20 mL of sterile water and mechanically fragmented for 5 s to generate a liquid suspension of hyphal segments that were immediately applied onto Populus roots to induce Ca2+ spiking.

Root Hair Branching Assays

We performed an initial screen for root hair branching (Figure 1) and later quantified how frequently root hair branching occurred (Supplemental Figure 1). The methods for these assays differed slightly. For the first screen, hyphal exudates from L. bicolor were prepared as described in the "Fungal Material and Culture" section, and then 1 mL of hyphal exudates was applied onto root hairs of M. truncatula and V. sativa in zone II of developing roots (Heidstra et al., 1994). As positive controls for M. truncatula and V. sativa, we used sLCOs and nsLCOs, respectively, that were suspended in water with 0.005% ethanol (v/v) at a concentration of 10−8 M. We also applied GSE as an additional positive control. Both CO4 and mock—water containing 0.005% ethanol (v/v)—treatments were used as negative controls. After 24 h of horizontal incubation at room temperature on the bench, the treated regions of the roots were screened with an inverted transmission light microscope (Leica DMi1) using a 20×/0.30 Leica PH1 objective. Root hairs on the primary root of at least five plants were observed for each treatment.

Subsequent root hair branching assays (Supplemental Figure 1) were performed slightly differently: L. bicolor exudates were extracted from either water or broth cultures of L. bicolor. The water cultures were prepared as described in the "Fungal Material and Culture" section for the L. bicolor cellophane cultures, except that the fungus was floated on water for 5 d instead of 3 d. The broth cultures were derived from L. bicolor grown in 50 mL of liquid modified Melin-Norkrans medium (MMN; PhytoTechnology Laboratories) for 1 month in the dark at room temperature. Both the water and MMN broth were filter sterilized using a low-affinity 0.22-µm polystyrene filter (Corning), and the sterile exudates were stored at room temperature (25°C) in a sterilized glass bottle. The root hair branching activity of both types of exudates was analyzed as follows: 1 mL of sterile exudate was applied onto the roots of 1-week-old M. truncatula and V. sativa seedlings. Treated plants were incubated at room temperature for 48 h, and the plates in which they were cultured were half covered with aluminum foil to keep the roots in the dark and the leaves in the light. Following incubation, the bottom 3 cm of five roots per treatment (n = 5) per plant species were observed. With the exception of GSE, the same positive controls were used as before, and MMN broth was used as an additional negative control.

Production of Hyphal Exudates for Mass Spectrometry

In our previous study of LCOs from Rhizobium sp IRBG74, 5 liters of bacterial exudates was not sufficient to detect any LCOs by mass spectrometry (Poinsot et al., 2016). In that study, detection of LCOs was only possible after engineering the strain with extra copies of the regulatory nodD gene from Sinorhizobium sp NGR234. Similarly, the discovery of LCOs in Rhizophagus irregularis was only possible after using 450 liters of sterile culture medium used for AM-colonized carrot (Daucus carota) roots and exudates from 40 million germinating AM fungal spores (Maillet et al., 2011). Here, we used a total volume of 6 liters of culture medium from 17 independent cultures of L. bicolor (Supplemental Table 1). First, fungal cultures were initiated on modified Pachlewski (MP) medium (Jargeat et al., 2014) overlaid with cellophane membrane with one plug per 55-mm Petri dish or three plugs per 90-mm Petri dish. After 2 to 3 weeks, mycelia were transferred to Petri dishes filled with either liquid MP medium (six independent series) or liquid modified MP medium (2.5 g L−1 Glc; 11 independent series). All liquid cultures were incubated at 24°C in the dark for 4 weeks without agitation. The fungal culture media (100 to 400 mL depending on the series) were extracted twice with butanol (1:1, v/v). The pooled butanol phases were washed with distilled water and evaporated under vacuum. The dry extract was re-dissolved in 4 mL of water:acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) and dried under nitrogen.

Mass Spectrometry Analyses

Synthetic lipochitin standards (LCO IV-C16:0, LCO IV-C16:0 S, LCO IV-C18:1, and LCO IV-C18:1 S) obtained from Hugues Driguez (CERMAV) were used to optimize HPLC/QTRAP tandem mass spectrometry detection by MRM, at 10−5 M in acetonitrile (ACN):water (1:1, v/v), as described previously by Maillet et al. (2011). For HPLC, the HPLC 3000 (Dionex) was equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column Acclaim 120 (2.1 × 250 mm, 5 µm, Dionex). Separation was achieved using a gradient of ACN/water:acetic acid (1000/1, v/v), started at 30% ACN for 1 min, followed by a 30-min gradient to 100% ACN, followed by an isocratic step at 100% ACN for 5 min, at a constant flow rate of 300 μL min−1. For U-HPLC C18 reverse-phase column C18 Acquity (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters) was used. Separation was achieved using a gradient of ACN/water:acetic acid (1000:1, v/v), started at 30% ACN in water for 1 min, followed by an 8-min gradient to 100% ACN, followed by an isocratic step at 100% ACN for 2 min, at a constant flow rate of 450 μL min−1. Ten-microliter samples were injected. The mass spectrometer was a 4500 QTRAP mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) with electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode. The samples were analyzed in the MRM and enhanced mass spectrometry–enhanced product ion modes. The capillary voltage was fixed at 4500 V and source temperature at 400°C. Fragmentation was performed by collision-induced dissociation with nitrogen at a collision energy between 22 and 54 V. Declustering potential was between 90 and 130 V and was optimized for each molecule. The MRM channels were set according to the transitions of the proton adduct ion [M+H]+ to the fragment ions corresponding to the loss of one, two, or three N-acetyl glucosamine moieties at the reducing end (sulfated or not).

RNAi-Construct Design for Silencing CASTOR, POLLUX, and CCaMK

Because of genome duplication, two homologs of CASTOR, POLLUX, and CCaMK exist in the Populus genome (Tuskan et al., 2006): PtCASTORa (Potri.019G097000) and PtCASTORb (Potri.013G128100), PtPOLLUXa (Potri.003G008800) and PtPOLLUXb (Potri.004G223400), and PtCCaMKa (Potri.010G247400) and PtCCaMKb (Potri.008G011400), respectively. Given that neither copy of these genes had been characterized previously, both copies of each gene were targeted simultaneously for RNA-based gene silencing. For PtCASTOR, PtPOLLUX, and PtCCaMK, respectively, a 175-, 153-, or 200-bp DNA fragment was selected based on sequence similarity between both paralogs of each gene and amplified using compatible primers (Supplemental Table 2). PCR-amplified products were cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO entry vector following the manufacturer’s guidelines (Invitrogen). Subsequently, the PtCASTORa/b-RNAi, PtPOLLUXa/b-RNAi, and PtCCaMKa/b-RNAi fragments were individually cloned into the pK7GWIWG2(II) binary vector using Gateway LR Clonase (Invitrogen; Supplemental Table 3). Following insertion, the resulting RNAi constructs were verified for proper orientation and integrity through sequencing and were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain AGL1 (Lazo et al., 1991) for transformation into Populus tremula × Populus alba clone INRA 717-1-B4.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated Populus Transformation

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain AGL1 was used to transform the RNAi binary vectors into Populus as described previously by Filichkin et al. (2006). Briefly, Agrobacterium cells harboring the RNAi binary vectors were grown for 24 h in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 50 mg L−1 rifampicin, 50 mg L−1 kanamycin, and 50 mg L−1 gentamycin on an orbital shaker at 28°C and 250 rpm. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 3500 rpm (1992 RCF) for 30 to 40 min and then resuspended in sufficient Agrobacterium induction medium to achieve an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.6. Internodal stem segments (3 to 4 mm in length) and leaf discs (4 mm in diameter) were wounded with multiple fine cuts and incubated in the Agrobacterium suspension with slow agitation for 1 h. The inoculated explants were cocultivated in callus-induction medium (MS supplemented with 10 µM naphthaleneacetic acid [Sigma-Aldrich]) and 5 µM N6-(2-isopentenyl)adenine [Sigma-Aldrich]) at 22°C in darkness for 2 d. Explants were then washed four times in sterile, deionized water and once with wash solution (Han et al., 2000). For selection of transformed calli, explants were transferred to callus-induction medium containing 50 mg L−1 kanamycin and 200 mg L−1 Timentin (GlaxoSmithKline) for 21 d. Shoots were induced by culturing explants on shoot inducing medium (MS containing 0.2 µM thidizuron [NOR-AM Chemical], 100 mg L−1 kanamycin, and 200 mg L−1 Timentin [GlaxoSmithKline]) for 2 to 3 months, with subculturing every 3 to 4 weeks. For shoot elongation, explants were transferred onto MS medium containing 0.1 µM 6-benzylaminopurine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 mg L−1 kanamycin, and 200 mg L−1 Timentin. The regenerated shoots were rooted on half-strength MS medium supplemented 0.5 µM indole-3-butyric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and 25 mg L−1 kanamycin.

For the CASTOR-, POLLUX-, and CCaMK-RNAi constructs, 259, 303, and 259 independent transgenic events were generated, respectively. After multiple rounds of initial selection based on resistance to kanamycin in the selection medium, 21, 32, and 82 events of PtCASTOR-, POLLUX-, and CCaMK-RNAi, respectively, were further confirmed for the presence of the transgene (RNAi cassette) in the transgenic plants using primers designed on the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, terminator, and RNAi intron flanking the RNAi fragments (Supplemental Table 3). All of the transgenic RNAi lines were maintained as described in the "Plant Material and Culture" section for further validation of the effect of RNAi-based gene silencing.

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from ∼100 mg of root tissue from at least three separate plants for each RNAi line by flash freezing them in liquid nitrogen and pulverizing them with two glass beads using a mixer mill (model MM 400, Retsch). Immediately after, 500 μL of RNA extraction buffer (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.2 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 25 mM EDTA, 2.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone [v/v], 2% sarkosyl [v/v], and 1% β-mercaptoethanol [v/v] added just before use) was added to the pulverized root tissue and vortexed for 5 s. Next, 500 μL of 24:1 chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (v/v) was added to the solution and again vortexed for 5 s. Following a 10-min centrifugation at 11,000 rpm and 4°C, 450 μL of the aqueous phase of the solution was placed on a shearing column from the Epoch GenCatch plant RNA purification kit. From this point forward, the manufacturer’s protocol was strictly followed. Following the extraction, RNA quantity and quality were evaluated with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (model ND100, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and suitable RNA was stored at −80°C. Contaminating DNA was removed from RNA samples using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Invitrogen) and by following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quantity and quality were again determined with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer.