Abstract

Background:

Activation of the complement system and complement deposition on red blood cells (RBCs) contribute to organ damage in trauma. We conducted a prospective study in subjects with traumatic injuries to determine the pattern of complement deposition on RBC and whether they are associated with clinical outcomes.

Method:

A total of 124 trauma patients and 42 healthy controls were enrolled in this prospective study. RBC and sera were collected at 0, 6, 24 and 72 hours from trauma patients and healthy controls during a single draw. Presence of C4d, C3d, C5b-9, phosphorylation of band 3 and production of nitric oxide were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results:

RBC from trauma patients at all time points up to 24 hours displayed significantly higher deposition of C4d on their RBC membrane as compared to healthy donors. Incubation of normal RBC with sera from trauma patients resulted in significant increase of C4d deposition (at 0, 6, 24 and 72 hours), C5b-9 deposition (at 0 and 6 hours), phosphorylation of band 3 (at 0 and 24 hours), and nitric oxide (NO) production up to 24 hours compared to sera from healthy subjects. Deposition of C4d and C5b-9 in patients with an ISS of 9 and above remained elevated up to 72 hours.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates that the presence of C4d, C3d, and C5b-9 on the surface of RBC is linked to increased phosphorylation of band 3 and increased production of nitric oxide. Deposition of C4d and C5b-9 decreased faster over course of 3-day study in subjects with ISS less than 9.

Keywords: Complement, trauma, C4d, C3d, C5b-9, band 3, nitric oxide

Introduction

The consequences of trauma cannot be ignored with over 10 million motor vehicle collisions occurring every year with enormous clinical challenge (1–3). Despite significant advances in injury prevention, prehospital resuscitation strategies, and modern intensive care, trauma remains the leading cause of death resulting from accidents or unintentional injuries for those less than 50 years old and accounts for one out of about every 20 deaths in the United States. (4–6).

Although trauma involves anatomical injury that leads to hemorrhage, there are also important pathophysiologic sequalae that compromise organ function that are not directly affected by initial injury. The origin of these secondary manifestations remains incompletely understood (7). Survival of patients after severe tissue trauma first requires an adequate surgical management. However, equally important is the rational therapeutic approach of complications arising from the metabolic and immunologic disturbances. Data suggest that the innate immune response (including the complement system, coagulation cascade, and neutrophils) which intends to control the injury paradoxically confers collateral damage leading to manifestations from multiple organs (8.

Trauma can affect any individual at any location and at any time over a lifespan. The instant activation of complement systems and interacting platelets are rapidly activated after disruption of micro- and macro-barriers, which results in a stemming of hemorrhage and protection against invading bacteria (9). Activation of the complement system occurs through three distinct pathways: the Classical pathway, the Lectin Pathway and the Alternative pathway. In addition, the complement system can be activated via the coagulation system and most notably from the generation of thrombin (10). All three activation pathways lead to the generation of C3 convertase which then cleaves C3 to generate C3a and C5a whereas thrombin acts directly on C3 and C5 to generate C3a and C5a respectively. All three complement activation pathways and the coagulation pathway subsequently lead to generation of the membrane attack complex C5b-9 (MAC). However, only the classical pathway leads to the generation of C4 via C1q (11). Together, complement activation and the proinflammatory cytokine storm are two of the main triggers of pathology which occurs in patients after trauma. They collectively choreograph a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure (12). In other situations where complement is profusely activated, such as in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), complement fragments deposit on the surface of red blood cells (RBC). C4d and C3d are the stable remnants of C4 and C3 respectively, and they remain on the surface of RBC, as demonstrated in patients with SLE, for a prolonged period of time. (13, 14) C4d and C3d deposition limits the deformability of RBC while promoting nitric oxide production (15). RBC membrane deformability is linked to the phosphorylation status of membrane proteins such as β-spectrin or band 3 (16, 17). We have previously reported that C4d decorates the surface of RBC and possibly limits their ability to deform and pass through capillary-size microchannels and increases the production of NO in patients suffering from trauma (7). It has been reported that human RBC express an active and functional endothelial-type NO synthase (eNOS) which is present in the membrane and in the cytoplasm (18). In RBC, mechanical stress (shear stress) stimulates NO generating mechanisms and Ca2+ is important in this process (19). Nitric oxide is a free radical gas produced from arginine by nitric oxide synthase and is an important vasodilator which acts on vascular endothelium and underlying vascular muscle and is an important inhibitor of platelet aggregation (20).

Understanding the pattern of complement deposition following trauma is crucial to the development of proper interventional strategies to accompany or replace conventional treatment methods. Human RBC have an average life span in the circulation of approximately 120 days (21). However, the various activation products of complement have diverse half-lives in vivo. For the analysis of complement deposition on RBC, it is essential to measure activation products of choice in a similar way. Due to rapid receptor binding, the biologically highly active and important C5a fragment has a half-life of approximately 1 min (22) and is difficult to detect in samples obtained in vivo, whereas the various C3 activation products are readily detectable due to half-lives of a few hours (23). The half-life of SC5b-9 is 50 to 60 min (24). SC5b-9, in contrast to C3 activation products, is relatively stable in vitro and is a reliable indicator of terminal pathway activation. Complement activation products are usually present in only trace amounts in vivo, but they are rapidly generated in vitro (25).

Due to the longevity of RBC survival in vivo and the short circulating half-lives of complement split products, we applied two strategies to analyze complement deposition on RBC. First, the collected samples were stored properly to avoid in vitro activation. Second, RBC from universal donors were incubated with sera isolated from whole blood of trauma patients that were collected upon admission to the emergency department (0 hour), and 6, 24 and 72 hours later. We hypothesized that traumatic injury activates the complement system and complement activation products deposit on the surface of RBC and could limit RBC function differently at various time intervals after trauma. The aim of this prospective study was to investigate serial changes in complement deposition after traumatic injury in patients and seek correlations with clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Participants:

This prospective, observational study was approved by the institutional Review Board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and was carried out with written informed consent. A total of 124 patients who visited the emergency department at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for trauma from September 2015 to June 2018 were enrolled non-consecutively. Trauma patients were 18 years and older, and were admitted for long bone fracture or organ injury. Blood tests were performed as required for their care. Blood samples were collected at the time patients were enrolled in the study in the emergency department (0 hour) and again at 6, 24, and 72 hours post-enrollment. Patients diagnosed with infection or autoimmune diseases were excluded from the study. None of the patients had received a transfusion prior to sampling. Clinical data were recorded including age, sex, ethnicity, mechanism of injury, and existing injury. Injury Severity Score (ISS) was calculated. Healthy donors (n=42) were recruited from the Division of Rheumatology and Emergency Department at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center after written informed consent. They did not have any apparent illness.

Antibodies and reagents

Primary antibodies were anti-C4d monoclonal antibody (Quidel, San Diego, CA) (murine anti-human monoclonal C4d, dilution 1:250), anti-C3d monoclonal antibody (Quidel, San Diego, CA) (murine anti-human monoclonal C3d, dilution 1:25), anti-C5b-9 polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (rabbit polyclonal to C5b-9, dilution 1:100) and IgG1k-isotype control (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). Secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG and donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Life technologies, Grand Island, NY) (dilution 1:100). Other reagents were as follows: Hanks’ balanced salt solution with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS++) (Life technologies), IgG-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), DAF-FM diacetate (Life technologies) and eosin-5-maleimide (Life technologies).

RBC preparation and incubation with sera

Blood was collected in heparin-lithium tubes for RBC and for serum in serum-separator tubes. For serum separation the tubes were centrifuged for 10 min at 1300 xg and at room temperature. Serum was collected in polypropylene plastic test tubes and was stored at −80°C. Heparinized blood was washed in HBSS++ before use. On the day of the experiment for serum studies, serum samples were thawed from various trauma patients and healthy donors and were used for different measurements under identical conditions. Blood from healthy universal donors (type O, Rh negative) was obtained in heparin-lithium tubes and washed with HBSS++. One μl of RBC pellet was resuspended in 80 μl of HBSS++, and incubated with 20 μl of serum from trauma patients or normal donors for 15 minutes at 37°C, and then washed in HBSS++ with 0.5% IgG-free BSA (0.5%BSA/HBSS++).

Flow cytometry

RBC were incubated for 20 minutes with a primary antibody in 0.5%BSA/HBSS++ at room temperature, washed and incubated for another 20 minutes with a fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody directed against the primary antibody at a dilution recommended by the manufacturer. RBC were then washed and analyzed by FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). At least 10,000 events in each sample were acquired and recorded, and analyzed by FlowJo (version 10 software; Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Eosin-5-maleimide staining

RBC from healthy universal donors were incubated in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ with 20% trauma or control sera for 5 minutes at 37°C, and then incubated for 15 min with eosin-5-maleimide at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. RBC then were washed 3 times with HBSS++ and 0.5%BSA/HBSS++ and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Measurement of NO production

RBC from healthy universal donors were preloaded with DAF-FM diacetate in BSA-free HBSS++ and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. RBC were washed to remove excess and un-cleaved intracellular DAF-FM diacetate probe. Cells were then resuspended in HBSS++ with 20% trauma or control serum for 15 minutes at 37°C. RBC were washed and the fluorescence intensity associated with intracellular NO production was recorded by FACScan using the FL-1 channel.

Statistical analysis

Both SAS (version 9.4 for Windows) and Graphpad Prism (version 6 for Windows) were used for statistical analysis. We fit regression models using generalized estimating equations (GEE) methods to account for correlated repeated measures within patients. Based on these models, we compared logarithmic transformed outcome measures at 0, 6, 24 and 72 hours for trauma patients to healthy controls. Adjustment for multiple comparisons was done by Sidak. An adjusted value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation between the ISS and the amount of C4d, C3d, C5b-9 deposition, Band 3 phosphorylation and NO production was assessed by Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) and significance (p).

Results

Patient characteristics:

124 patients were included in this study. The patient group consisted of 53 (43%) women and 71 (57%) men with mean age of 54 (± 21) years (Table 1). Most of the patients presented with blunt injury resulting from motor vehicle crash or fall. The mean value of ISS was 12.3(± 10.2) and [3–34] range.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of research subjects

| Demographic Data | Healthy Donors | Trauma |

|---|---|---|

| Total number (n) | 42 | 124 |

| Age, mean (± SD), year | 38 (4) | 54 (21) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 31 (74%) | 71 (57%) |

| Female | 11 (26%) | 53 (43%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%)* | ||

| White | 10 (37%) | 75 (80%) |

| Black | 2 (7%) | 8 (9%) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 7 (7%) |

| Other | 15 (56%) | 4 (4%) |

| Mechanism of trauma, n (%) | ||

| Motor vehicle crash | 28 (23%) | |

| Fall | 76 (61%) | |

| Pedestrian struck | 11 (9%) | |

| Other | 10 (8%) | |

| Organ injury | ||

| None | 73 (59%) | |

| Brain | 7 (6%) | |

| Lung | 26 (21%) | |

| Spleen | 9 (7%) | |

| Bowel | 2 (2%) | |

| Liver | 8 (6%) | |

| Kidney | 10 (8%) | |

| Retroperitoneal Bleed | 3 (2%) | |

| Other | 14 (11%) | |

| Type of bone fracture | ||

| None | 11 (9%) | |

| Femur | 21 (17%) | |

| Tibia or fibula | 37 (30%) | |

| Radius or ulna | 23 (19%) | |

| Humerus | 11 (9%) | |

| Hip | 11 (9%) | |

| Other | 45 (36%) | |

| Past medical history | ||

| Alcoholism | 6 (5%) | |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) | 2 (2%) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 2 (2%) | |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | 5 (4%) | |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 3 (2%) | |

| Dementia | 2 (2%) | |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) | 3 (2%) | |

| Hypertension (HTN) | 32 (26%) | |

| Intravenous drug user (IVDU) | 2 (2%) | |

| Liver disease | 5 (4%) | |

| Myocardial infarction (MI) | 6 (5%) | |

| Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) | 1 (1%) | |

| Diabetes | 10 (8%) | |

| Gout | 2 (2%) | |

| Osteoporosis | 5 (4%) | |

| Injury Severity Score, mean (± SD) | 12.3 ± 10.2 | |

Out of total 42 healthy donors, we were able to collect ethnicity information of only 27 healthy donors.

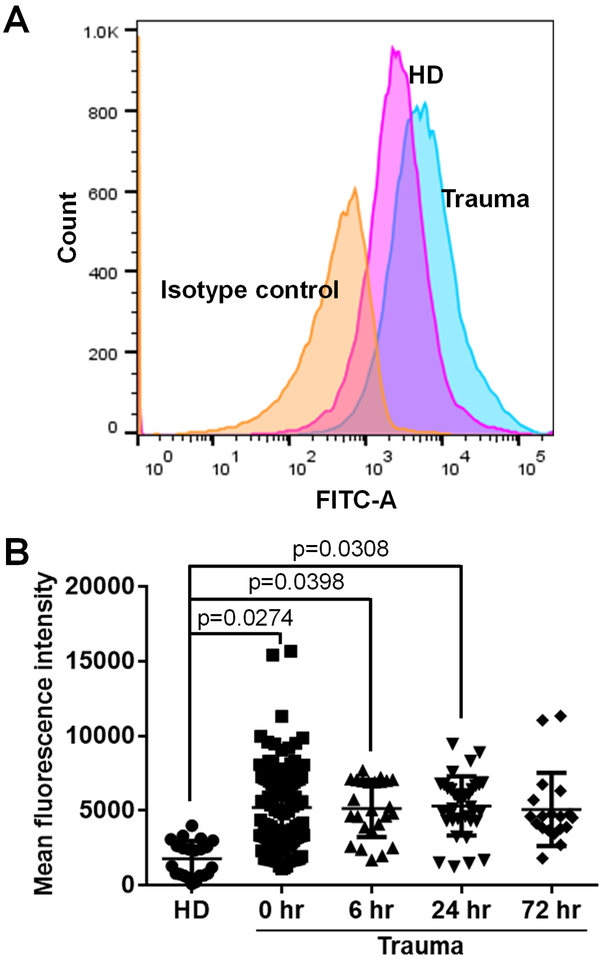

Deposition of C4d on RBC from patients with trauma

We determined the amount of C4d deposition on RBC from trauma patients over time and normal subjects by flow cytometry as shown in Figure 1A (representative experiment). We used 102 samples from trauma patients (n, 0 hour =102, 6 hour =24, 24 hour =35 and 72 hour =19) and 30 samples from healthy donors. RBC from trauma patients displayed significantly higher deposition of C4d on their membrane as compared to RBC from healthy donors at all time points up to 24 hours (p< 0.05). There were no significant differences between healthy donors and trauma patients at 72 hours, suggesting that C4d levels returned to basal levels before 72 hours (Figure 1B and Table 2). We noted a significant correlation between the ISS and the amount of C4d deposited on the surface of RBC (rs=0.25, p=0.010). Supplementary figure 1 shows pattern of deposition of C4d on RBC according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34).

Figure 1. Increased C4d deposition on the surface of RBCs from trauma patients.

Deposition of C4d on the surface of RBCs from trauma patients and healthy donors was measured by flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity. A, Representative flow cytometry experiment. B, we used samples from 102 trauma patients (n, 0 hour =102, 6 hour =24, 24 hour =35 and 72 hour =19) and 30 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of C4d deposition on the surface of RBCs was [2278 ± 1504 (94 – 5631)] for healthy donors, [5325 ± 2941 (1113–15683)] for 0 hour, [5254 ± 1862 (1698 – 7687)] for 6 hour, [5306 ± 1988 (1245 – 9462)] for 24 hour and [5074 ± 2444 (1802 −11346)] for 72 hour patients.

Table 2.

Mean ± SD (min - max) of mean fluorescence intensity

| Healthy Donor |

Trauma 0 hr |

Trauma 6 hr |

Trauma 24 hr |

Trauma 72 hr |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4d RBC | 2278 ± 1504 (94–5631) |

5325 ± 2941 (1113–15683) |

5254 ± 1862 (1698–7687) |

5306 ± 1988 (1245–9462) |

5074 ± 2444 (1802–11346) |

| C4d | 3233 ± 1610 (1197–9215) |

6071 ± 2578 (1647–15404) |

5817 ± 2701 (2795–13764) |

4753 ± 1741 (1585–7331) |

4361 ± 2903 (2206–13450) |

| C3d | 5863 ± 2868 (3025–14535) |

7728 ± 2707 (3351–14291) |

6264 ± 2234 (1959–9224) |

5775 ± 2012 (2188–10318) |

5725 ± 2897 (2384–12612) |

| C5b-9 | 2331 ± 1499 (853–6053) |

5661 ± 3621 (1986–14217) |

4590 ± 2405 (1964–8675) |

4115 ± 2375 (1902–9352) |

3883 ± 1751 (1893–7076) |

| Band-3 | 4052 ± 1380 (1806–7747) |

6698 ± 2911 (2761–15314) |

6522 ± 3115 (2693–15138) |

6338 ± 2451 (3297–12492) |

5557 ± 2517 (3217–12899) |

| NO | 1568 ± 730 (578–3455) |

2542 ± 934 (1392–8093) |

2809 ± 1189 (1488–6137) |

2084 ± 594 (1318–4134) |

1469 ± 430 (935–2437) |

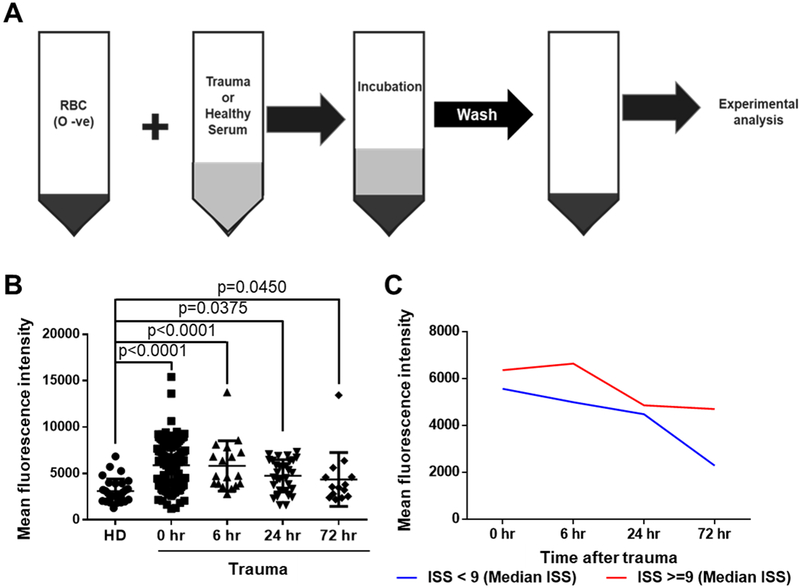

C4d deposition on healthy RBC incubated with sera from trauma patients

We developed a method to assess whether C4d in sera from trauma patients decorated RBCs. Incubation of RBC from universal donors (type O, Rh negative) with sera from trauma patients resulted in complement C4d deposition on the surface of RBC (Figure 2A). Incubation of normal RBC with sera from trauma patients (n, 0 hour =100, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) resulted in significant increase of C4d deposition at all time points up to 72 hours compared to sera from healthy controls (n=37) (p< 0.05) (Figure 2B and Table 2). We stratified patients into two groups according to ISS (below and above 9) to detect patterns of C4d deposition. As shown in Figure 2C, deposition of C4d in patients with an ISS of 9 and above remained elevated up to 72 hours when compared to patients with an ISS below 9. Supplementary figure 2 shows pattern of deposition of C4d according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34).

Figure 2. Deposition of C4d on the surface of healthy control RBCs (type O, Rh negative) incubated with sera from trauma patients or healthy control donors.

A, incubation of RBC from universal donors (type O, Rh negative) with sera from trauma patients or healthy donors. B, the C4d deposition on RBC from trauma patients over time compared to normal controls by flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity. We used samples from 100 trauma patients (n, 0 hour =100, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) and 37 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of C4d deposition on the surface of healthy control RBCs was [3233 ± 1610 (1197 – 9215)] for healthy donors, [6071 ± 2578 (1647–15404)] for 0 hour, [5817 ± 2701 (2795–13764)] for 6 hour, [4753 ± 1741 (1585 −7331)] for 24 hour and [4361 ± 2903 (2206 −13450)] for 72 hour patients. C, deposition of C4d in patients with an ISS of 9 and above remains elevated up to 72 hours when compared to patients with an ISS below 9.

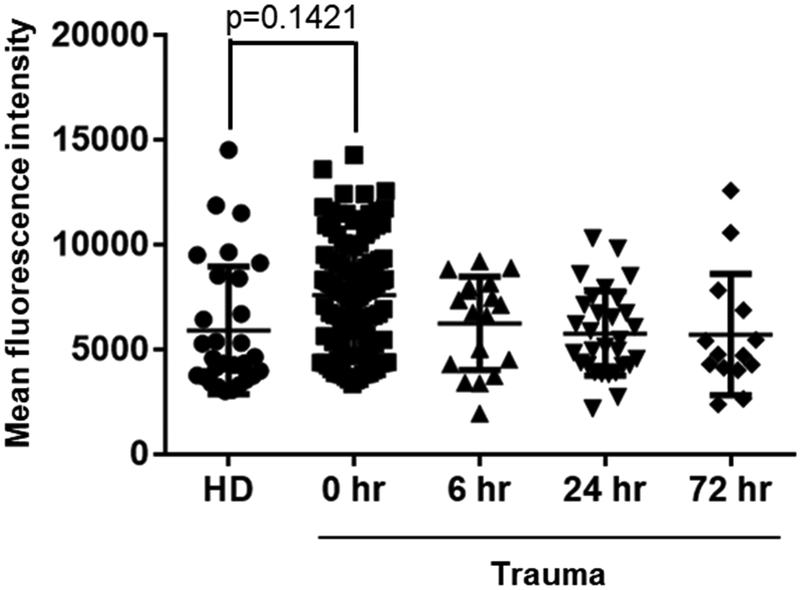

C3d deposition on healthy RBC incubated with sera from trauma patients

Next we looked at the deposition of C3d using the method described for C4d whereby we incubated RBC from universal donors (type O, Rh negative) with sera from trauma patients or healthy donors. Incubation of RBC with sera from trauma patients at 0 hour (n=104) resulted in higher C3d deposition on the surface of RBC when compared to sera from healthy controls (n=36) but this increase were not statistically significant (p=0.1421). We also did not observe a significant difference between trauma patients and healthy donors at the later time points of 6, 24 and 72 hours (Figure 3 and Table 2). Supplementary figure 3 shows pattern of deposition of C3d according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34).

Figure 3. Increased C3d deposition on healthy RBC surfaces incubated with trauma sera.

Deposition of C3d on the surface of healthy RBCs (type O, Rh negative) incubated with sera from trauma patients or healthy donors were measured by flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity. We used samples from 104 trauma patients (n, 0 hour =104, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =30 and 72 hour =14) and 36 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of C3d deposition on the surface of healthy control RBCs was [5863 ± 2868 (3025–14535)] for healthy donors, [7728 ± 2707 (3351–14291)] for 0 hour, [6264 ± 2234 (1959–9224)] for 6 hour, [5775 ± 2012 (2188–10318)] for 24 hour and [5725 ± 2897 (2384–12612)] for 72 hour patients.

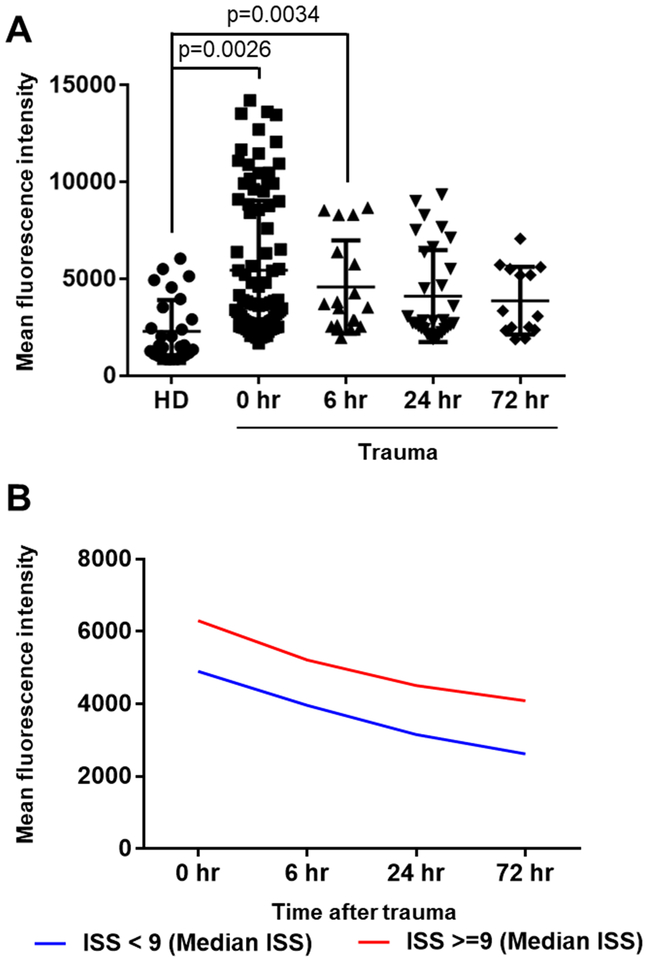

C5b-9 deposition on healthy RBC incubated with sera from trauma patients

Deposition of C5b-9 was also analyzed using the same method as described for C3d. Incubation of normal RBC with serum obtained from blood of individual trauma patients at 0 hour (n=84), 6 hours (n=18), 24 hours (n=31) and 72 hours (n=14) showed a significant increase in C5b-9 deposition in samples up to 6 hours compared to sera from healthy controls (n=34) (p=0.0026 for 0 hour and p=0.0034 for 6 hours) (Figure 4A and Table 2). Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the ISS and C5b-9 deposition on surface of RBC (rs=0.36, p=0.001). As shown in Figure 4B, deposition of C5b-9 in patients with an ISS of 9 and above remains elevated up to 72 hours when compared to patients with an ISS below 9. Supplementary figure 4 shows pattern of deposition of C5b-9 according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34).

Figure 4. Increased C5b-9 deposition on healthy RBC surfaces incubated with trauma sera.

A, the C5b9 deposition on RBC from trauma patients over time compared to normal controls by flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity. We used samples from 84 trauma patients (n, 0 hour =84, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) and 34 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of C5b-9 deposition on the surface of healthy control RBCs was [2331 ± 1499 (853 −6053)] for healthy donors, [5661 ± 3621 (1986–14217)] for 0 hour, [4590 ± 2405 (1964–8675)] for 6 hour, [4115 ± 2375 (1902–9352)] for 24 hour and [3883 ± 1751 (1893– 7076)] for 72 hour patients. B, deposition of C5b-9 in patients with an ISS of 9 and above remains elevated up to 72 hours when compared to patients with an ISS below 9.

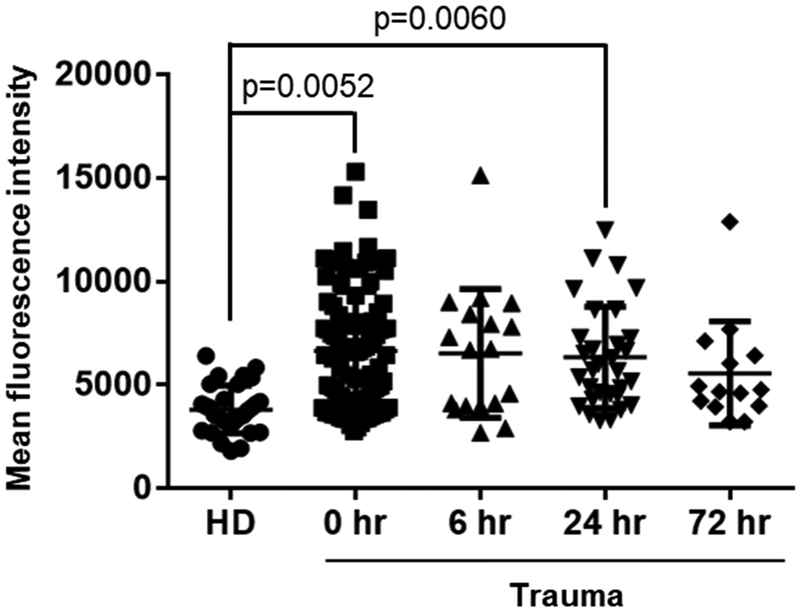

Phosphorylation status of band 3:

To determine whether band 3 becomes phosphorylated in RBC exposed to trauma sera, we treated universal donor RBC exposed to trauma (n=97) or control (n=35) sera with eosin-5-maleimide, a reagent which binds to lysine 430 on the extracellular loop of band 3 and is known to indicate tyrosine phosphorylation. Binding of eosin-5- maleimide to RBC has been used previously to estimate the phosphorylation levels of band 3 (16, 26). Here we used eosin-5-maleimide to estimate the tyrosine phosphorylation levels of band 3. Serial samples of sera from trauma patients at various time points (n, 0 hour =97, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) showed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of band 3 at 0 and 24 hours compared to sera from healthy controls (n=35) (Figure 5 and Table 2). The phosphorylation of band 3 significantly correlated with deposition of C4d (rs= 0.210, p= 0.043) and C5b-9 (rs= 0.469, p< 0.0001). Supplementary figure 5 shows pattern of phosphorylation status of band 3 according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34).

Figure 5. Phosphorylation status of band 3 in RBCs incubated with trauma sera.

Phosphorylation of band 3 in healthy RBCs (type O, Rh negative) measured by flow cytometry after incubation with sera from trauma patients or healthy donors, using eosin-5-maleimide staining. The band 3 phosphorylation in RBC from trauma patients over time compared to normal controls by flow cytometry and mean fluorescence intensity. We used samples from 97 trauma patients (n, 0 hour =97, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) and 35 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of band 3 phosphorylation was [4052 ± 1380 (1806–7747)] for healthy donors, [6698 ± 2911 (2761–15314)] for 0 hour, [6522 ± 3115 (2693–15138)] for 6 hour, [6338 ± 2451 (3297–12492)] for 24 hour and [5557 ± 2517 (3217–12899)] for 72 hour patients.

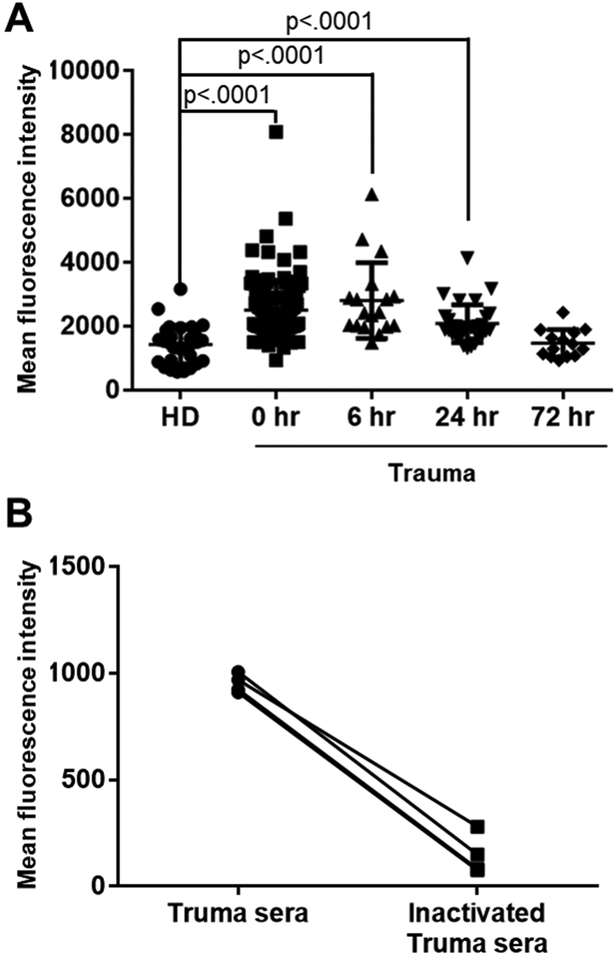

Induction of the NO production:

Since we previously observed that exposure of RBC to trauma serum results in increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (7), we asked whether it also results in increased NO production. Incubation of normal RBC with sera from trauma patients (n, 0 hour =104, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) resulted in significant increase of NO production at 0, 6 and 24 hours compared to sera from healthy controls (n=38) (Figure 6A and Table 2). There was no significant difference between trauma and healthy donor serum at 72 hour indicating that NO production returns to basal levels by that time point. Supplementary figure 6 shows NO production according to ISS that was grouped in 8 subgroups (ISS 3 – 6, 7 – 10, 11 – 14, 15 – 18, 19 – 22, 23 – 26, 27 – 30 and 31 – 34). Increased NO production resulted from complement deposition on RBC surfaces since heat inactivation of patient sera (55°C for 30 minutes) eliminated their ability to increase NO production by RBC (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Nitric oxide (NO) production by RBCs induced by trauma serum.

NO production from healthy RBCs (type O, Rh negative) measured by flow cytometry after incubation with sera from trauma patients or healthy donors by using DAF-FM diacetate. NO production from RBCs was expressed as mean fluorescence intensity of DAF-FM diacetate fluorescence. A, we used 104 samples from trauma patients (n, 0 hour =104, 6 hour =18, 24 hour =31 and 72 hour =14) and 38 samples from healthy donors (HD). The mean fluorescence intensity [Mean ± SD (min - max)] of nitric oxide production was [1568 ± 730 (578 – 3455)] for healthy donors, [2542 ± 934 (1392– 8093)] for 0 hour, [2809 ± 1189 (1488 – 6137)] for 6 hour, [2084 ± 594 (1318–4134)] for 24 hour and [1469 ± 430 (935 – 2437)] for 72 hour patients. B, Heat inactivation of complement in sera from trauma patients eliminates their ability to trigger NO production. To inactivate complement, sera were incubated 55°C for 30 min. RBCs were incubated with sera from trauma patients before or after inactivation of complement. Individual sera with/without inactivation of complement are shown. Straight lines are used to connect individual points to help visualize how different they are in each sample.

Discussion

In this prospective study we report increased deposition of complement split products (C4d and C5b-9) and enhanced levels of associated molecules (band 3 and NO) in trauma patients. Moreover, we find that the level of these molecules changes over time after trauma and declines more rapidly in patients with less severe (ISS less than 9) trauma. Our findings also confirmed a significant correlation between ISS and deposition of C4d and C5b-9 on RBC.

Identification of complement coated RBC from trauma patients while informative may not offer strong prognostic value because RBC are live long in the circulation and cells decorated with complement will be around for several days or weeks. However, testing the ability of sera to coat RBC from universal donors at any time during trauma offers a good estimate of the rate of complement activation and generation of short-lived complement split products. As shown by our data, C4d coated RBC is significantly greater compared to controls at admission. This is similarly observed when serum from trauma patients obtained at admission is used to coat C4d and C5b-9 on universal donor RBC. In contrast, serum from trauma patients obtained at later time points (6, 24 and 72 hours) revealed that elevation of C5b-9 occurs only transiently (able to coat RBC at the zero hour and six hours), C4d is elevated in the circulation over a longer time period (0 through 24 hours) and unlike C5b-9, C4d can coat RBC at all times tested (0 through 72 hours). We speculate that if RBC sampling was continued at later time points post admission, there would likely be a continued significant difference between trauma patients and controls. Indeed, sera from patients who have higher ISS have a sustained ability to coat RBC for a longer period of time. It is clear from our data that this differential analysis may provide prognostic value when correlated with the level of injury (ISS) upon admission to the Emergency Department and thereafter.

The activation of the complement pathway has been characterized by deposition of split products initiated at the early phase of trauma and may remain on RBC from hours to days. To date, there is little data regarding the effects of the non-inflammatory complement by-products generated during complement activation after trauma and it’s time course on circulating cell function including RBC. In this study we show that C4d, C3d and C5b-9, deposits on the surface of RBC and enhances NO production. These functional effects are likely due to the fact that C4d deposition on the surface of RBC promotes a significant RBC Ca2+ influx (7) that enhances phosphorylation of band 3. Similar deposition of C4d was recorded in RBC from patients with SLE in whom complement activation is prominent (15). The enhanced phosphorylation of band 3 at 0 hour returned to basal levels at 6 hours and again increased at 24 hours showing a biphasic response. This may occur due to factors other than complement that might also affect RBC membrane deformability.

The functional consequences of the deposition of complement on the surface of RBC cannot be overstated. In order for RBC to perform their primary function, that is to deliver oxygen to tissues, they must pass through narrower (<8 μm in diameter) capillaries. To do this, RBC must be able to deform (27, 28). Hypoxia may occur if deposition of C4d, C3d and C5b-9 renders RBC unable to deform and reach tissues. During normal conditions, RBC-generated NO is a key factor in the local regulation of vasomotor tone and microvascular flow resistance, by interacting directly with endothelial cells and indirectly with vascular smooth muscles (29). Nitric oxide derived from eNOS present in RBC also directly regulates and maintains RBC deformability (18, 30). In our study we demonstrated that NO production increases under trauma conditions and that may be due to increased complement deposition that decreases RBC deformability (7). We also found a significant correlation between phosphorylation of band 3 and NO production that further confirms the RBC cytoskeletal stiffness that may limit the deformability of RBC (31–33).

Our studies have certain limitations including the fact that the studied cohort was quite diverse in terms of origin of trauma (bone versus soft organs). While we limited the effect of important comorbidities by excluding patients with significant comorbidities from the study, the data about plausible confounding variables such as smoking, substance abuse, and medications were not collected. In addition, we were unable to recruit exact age-, ethnicity-, and sex- matched healthy individuals, and hence these parameters show differences between trauma and control groups. Most of the patients with minor injury who visited the emergency department at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center had low ISS scores. We were unable to collect a larger number of samples with high ISS scores. We believe that due to the low number of samples with high ISS, many complement molecules did not significantly correlate with ISS. Time 0 in our study was considered the time point of arrival and evaluation in the Emergency Department. Although all study parameters and sample handling were controlled thereafter, the elapsed time between the time the trauma occurred and the time of collection of the first sample was neither recorded nor considered.

Conclusions:

We conclude that C4d, C3d, and C5b-9 decorates the surface of RBC which enhances the phosphorylation of band 3 and increases the production of NO in various types of trauma for at least 72 hours. This study confirmed the significant correlation between injury severity score (ISS) and deposition of C4d and C5b-9 and that subject with severe trauma (ISS more than 9) maintain high deposition of complement components for at least 72 hours. Complement deposition on RBC alters their ability to deform and travel through capillaries and exchange gases in tissues and thus contributes to trauma-associated morbidity and mortality. Our prospective study strengthens the argument that complement activation and deposition on RBC may serve as a biomarker of trauma severity and complement inhibiting drugs and biologics should have a place in the treatment of subjects suffering trauma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Clinical Research Assistants of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Emergency Department for collecting blood samples. This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102, financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers and FA8650-15-2-6595 from Air Force Medical Support Agency (AFMSA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure of funding: National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR001102) and Air Force Medical Support Agency (FA8650-15-2-6595)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, AlMazroa MA, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, et al. : A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380(9859):2224–2260, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, et al. : Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380(9859):2197–2223, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau USC. Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. 131th edition In USDo Commerce; (ed). Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoyert DL, Xu J: Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports 61(6):1–51, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauvar DS, Wade CE: The epidemiology and modern management of traumatic hemorrhage: US and international perspectives. Critical Care 9(Suppl 5):S1–S9, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahimi-Movaghar V, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR: Trauma and long-term mortality. JAMA 305(23):2413–2414, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muroya T, Kannan L, Ghiran IC, Shevkoplyas SS, Paz Z, Tsokos M, Dalle Lucca JJ, Shapiro NI, Tsokos GC: C4d deposits on the surface of RBCs in trauma patients and interferes with their function. Critical Care Medicine 42(5):e364–e372, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keel M, Trentz O: Pathophysiology of polytrauma. Injury 36(6):691–709, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber-Lang M, Lambris JD, Ward PA: Innate immune responses to trauma. Nature Immunology 19(4):327–341, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricklin D, Reis ES, Lambris JD: Complement in disease: a defence system turning offensive. Nature Reviews Nephrology 12(7):383–401, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noris M, Remuzzi G: Overview of complement activation and regulation. Seminars in Nephrology 33(6):479–492, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittirsch D, Redl H, Huber-Lang M: Role of complement in multiorgan failure. Clinical and Developmental Immunology 2012(962927):10, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao AH, Navratil JS, Ruffing MJ, Liu CC, Hawkins D, McKinnon KM, Danchenko N, Ahearn JM, Manzi S: Erythrocyte C3d and C4d for Monitoring Disease Activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism 62(3):837–844, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manzi S, Navratil JS, Ruffing MJ, Liu CC, Danchenko N, Nilson SE, Krishnaswami S, King DES, Kao AH, Ahearn JM: Measurement of erythrocyte C4d and complement receptor 1 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism 50(11):3596–3604, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiran IC, Zeidel ML, Shevkoplyas SS, Burns JM, Tsokos GC, Kyttaris VC: Systemic lupus erythematosus serum deposits C4d on red blood cells, decreases red blood cell membrane deformability, and promotes nitric oxide production. Arthritis & Rheumatism 63(2):503–512, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Condon MR, Feketova E, Machiedo GW, Deitch EA, Spolarics Z: Augmented erythrocyte band-3 phosphorylation in septic mice. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 1772(5):580–586, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manno S, Takakuwa Y, Nagao K, Mohandas N. Mohandas: Modulation of erythrocyte membrane mechanical function by β-Spectrin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 270(10):5659–5665, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinbongard P, Schulz R, Rassaf T, Lauer T, Dejam A, Jax T, Kumara I, Gharini P, Kabanova S, Özüyaman B, et al. : Red blood cells express a functional endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Blood 107(7):2943–2951, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ulker P, Meiselman HJ, Baskurt OK. Baskurt: Nitric oxide generation in red blood cells induced by mechanical stress. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 45(2–4):169–175, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Förstermann U, Sessa WC: Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. European Heart Journal 33(7):829–837, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shemin D, Rittenberg D: The life span of the human red blood cell. Journal of Biological Chemistry 166(2):627–636, 1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppermann M, Götze O: Plasma clearance of the human C5a anaphylatoxin by binding to leucocyte C5a receptors. Immunology 82(4):516–521, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teisner B, Brandslund I, Grunnet N, Hansen LK, Thellesen J, Svehag SE: Acute complement activation during an anaphylactoid reaction to blood transfusion and the disappearance rate of C3c and C3d from the circulation. Journal of Clinical & Laboratory Immunology 12(2):63–67, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mollnes TE: Early- and late-phase activation of complement evaluated by plasma levels of C3d,g and the terminal complement complex. Complement 2:156–164, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollnes TE, Garred P, Bergseth G: Effect of time, temperature and anticoagulants on in vitro complement activation: consequences for collection and preservation of samples to be examined for complement activation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 73(3):484–488, 1988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minetti G, Piccinini G, Balduini C, Seppi C, Brovelli A: Tyrosine phosphorylation of band 3 protein in Ca2+/A23187-treated human erythrocytes. Biochemical Journal 320(2):445–450, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diez-Silva M, Dao M, Han J, Lim C-T, Suresh S: Shape and biomechanical characteristics of human red blood cells in health and disease. MRS bulletin / Materials Research Society 35(5):382–388, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohandas N, Gallagher PG: Red cell membrane: past, present, and future. Blood 112(10):3939–3948, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baskurt OK, Ulker P, Meiselman HJ: Nitric oxide, erythrocytes and exercise. Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation 49(1–4):175–181, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bor-Kucukatay M, Wenby RB, Meiselman HJ, Baskurt OK. Baskurt: Effects of nitric oxide on red blood cell deformability. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 284(5):H1577–H1584, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferru E, Giger K, Pantaleo A, Campanella E, Grey J, Ritchie K, Vono R, Turrini F, Low PS: Regulation of membrane-cytoskeletal interactions by tyrosine phosphorylation of erythrocyte band 3. Blood 117(22):5998–6006, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H, Yang J, Chu TT, Naidu R, Lu L, Chandramohanadas R, Dao M, Karniadakis GE: Cytoskeleton remodeling induces membrane stiffness and stability changes of maturing reticulocytes. Biophysical Journal 114(8):2014–2023, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodríguez-García R, López-Montero I, Mell M, Egea G, Gov Nir S, Monroy F: Direct cytoskeleton forces cause membrane softening in red blood cells. Biophysical Journal 108(12):2794–2806, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.