Abstract

Injury to sensory neurons causes an increase in the excitability of these cells leading to enhanced action potential generation and a lowering of spike threshold. This type of sensory neuron plasticity occurs across vertebrate and invertebrate species and has been linked to the development of both acute and persistent pain. Injury-induced plasticity in sensory neurons relies on localized changes in gene expression that occur at the level of mRNA translation. Many different translation regulation signalling events have been defined and these signalling events are thought to selectively target subsets of mRNAs. Recent evidence from mice suggests that the key signalling event for nociceptor plasticity is mitogen-activated protein kinase-interacting kinase (MNK) -mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4E. To test the degree to which this is conserved in other species, we used a previously described sensory neuron plasticity model in Aplysia californica. We find, using a variety of pharmacological tools, that MNK signalling is crucial for axonal hyperexcitability in sensory neurons from Aplysia. We propose that MNK-eIF4E signalling is a core, evolutionarily conserved, signalling module that controls nociceptor plasticity. This finding has important implications for the therapeutic potential of this target, and it provides interesting clues about the evolutionary origins of mechanisms important for pain-related plasticity.

This article is part of the Theo Murphy meeting issue ‘Evolution of mechanisms and behaviour important for pain’.

Keywords: nociceptor plasticity, eIF4E, MNK1/2, eFT508, axon plasticity, translation regulation

1. Introduction

Nociceptors are specialized sensory neurons that detect potentially damaging or damaging stimuli [1,2]. These neurons have been found in diverse species that have organized nervous systems [3]. A key feature of these cells is that they can display remarkable sensitization when they are activated by stimuli to which they respond (e.g. inflammatory mediators) or when they are injured (e.g. by axonal crush) [4,5]. Nociceptor sensitization typically involves electrical hyperexcitability characterized by a drop in the amount of depolarization required to initiate an action potential, the generation of repetitive firing or afterdischarge following an evoked action potential, and the generation of action potentials without any extrinsic stimulus (spontaneous activity), as well as enhanced responsiveness to chemical signals. Nociceptor sensitization is important because it enhances the efficacy of warning and teaching signals that the nociceptor conveys to the organism. Experiments in squid have demonstrated that nociceptor sensitization serves a survival function [6]. In most species, nociceptor sensitization is almost certainly a driver of protective behaviour that allows tissue healing to run its full course without reinjury, which could easily occur in the absence of sensitization. However, there is strong evidence that nociceptor sensitization can persist after the tissue healing process has resolved and that nociceptor sensitization can also arise in response to insults to the peripheral or central nervous systems [3–5]. These forms of non-resolving nociceptor sensitization are key drivers of chronic pain disorders [1,2,4,5] and are directly linked to neuropathic pain in patients [7].

Nociceptor sensitization requires changes in gene expression that are controlled at the level of translation of mRNA [8]. In neurons, activity-dependent or injury-related translation is controlled by upstream protein kinases that phosphorylate translation initiation and elongation factors [9]. These phosphorylation events have specific actions on the translation of distinct subsets of mRNAs. Phosphorylation of eIF2α causes translation through upstream open reading frames [10]. Phosphorylation of eIF4E binding proteins (4EBPs) or ribosomal S6 proteins (rS6) by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) controls the translation of mRNAs containing terminal oligopyrimidine tracts in their 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) [11]. Finally, the mitogen-activated protein kinase-interacting kinase (MNK)-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4E controls the translation of a subset of mRNAs including Mmp9, Bdnf and Rraga that are involved in neuronal plasticity [12–14]. Some of the earliest experiments studying translation regulation in nociceptor sensitization used Aplysia sensory neuron preparations to show that axonal hyperexcitability caused by nerve crush or intense artificial depolarization of a nerve segment mimicking that produced by axon transection was driven by translation events at the site of injury via an mTOR pathway [15]. Subsequent experiments in other species have obtained similar results, strongly suggesting that translation of new proteins at the site of insult is a crucial cause of nociceptor sensitization [8]. These findings have striking parallels in the learning and memory literature, where it has long been known that local translation at the base of dendritic spines controls both long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) [16].

A key question is whether a single phosphorylation event is the critical driver of translation regulation governing nociceptor plasticity. While there is strong evidence that mTOR is involved in this process [17–19], mTOR has many downstream targets such as 4EBP and rS6 proteins, which have distinct effects on cellular function [20]. Moreover, MNK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF4E regulates mTOR because eIF4E phosphorylation contributes to control of translation of Rraga mRNA [13], which encodes the protein RagA that is required for mTOR activation at the surface of the lysosome [21,22]. Previous work from our laboratory demonstrates that MNK1-mediated control of eIF4E phosphorylation is required for many forms of nociceptor sensitization in mice. Mice lacking the MNK phosphorylation site (serine 209) on eIF4E do not sensitize to many cytokines, show decreased responses to inflammatory mediators and have decreased neuropathic pain [13,14,23,24]. Manipulating this pathway with an MNK inhibitor called eFT508 [25] achieves similar effects in adult mice indicating that this effect is not a developmental artefact caused by lack of eIF4E phosphorylation [13]. Given that the existing evidence indicates that eIF4E phosphorylation at serine 209 is a critical signalling event driving nociceptor sensitization, we sought to test whether this would be conserved in nociceptors of the gastropod mollusc, Aplysia californica. We used identified clusters of mechano-nociceptors [26,27] that exhibit multiple sensitizing alterations after noxious bodily stimulation or nerve injury [15,28,29]. The results presented here provide compelling support for the hypothesis that eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK is a core, evolutionarily conserved mechanism driving nociceptor sensitization.

2. Methods

(a). Preparation

Aplysia californica (50–300 g) obtained either from the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego or from the National Institutes of Health breeding program at the University of Miami were housed at the University of Texas at Dallas or McGovern Medical School at UTHealth for up to four weeks prior to experiments. Animals were anaesthetized by injecting isotonic MgCl2 solution (383 mM), after which a pedal-pleural ganglion pair was excised. The excised ganglia were pinned in a Sylgard chamber within a large well, and the posterior pedal ganglion (p9) nerve was threaded through a series of smaller wells connected by 2 mm slots. The pleural ganglion was surgically desheathed in a mixture of 50% artificial seawater (ASW, containing, in mM: 460 NaCl, 10 KCl, 11 CaCl2 dihydrate, 55 MgCl2 hexahydrate, and 10 Tris buffer, pH 7.6) and 50% isotonic MgCl2. Silicon grease was applied around the nerve in the 2 mm connecting slots to seal the smaller wells from one another as described previously [15]. In many experiments, all wells were then filled with buffered 1% - Ca2+ saline (containing, in mM: 460 NaCl, 10 KCl, 0.1 CaCl2 dihydrate, 66 MgCl2 hexahydrate, and 10 Tris buffer, pH 7.6). In the experiments shown in figure 4, the wells were filled with a similar solution having an even lower Ca2+ concentration (less than 100 nM): 460 NaCl, 10.4 KCl, 1 EGTA, 66 MgCl2 and 10 HEPES. No significant differences in depolarization-induced axonal hyperexcitability have been found in experiments using these two low–Ca2+ solutions [15,30].

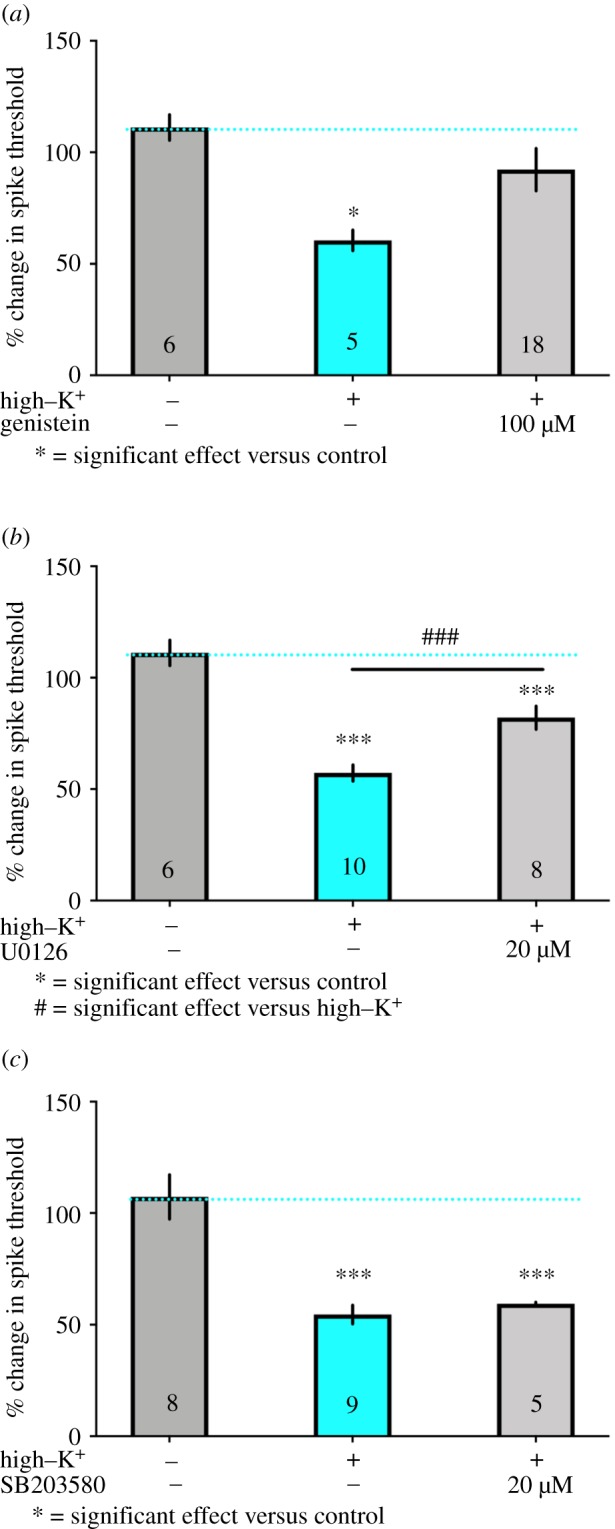

Figure 4.

Trk and MEK/ERK but not p38 inhibition of depolarization-induced sensitization. Axonal hyperexcitability in identified nociceptors induced by brief high–K+ treatment was reversed by pre-treatment for 15 min and then co-treatment at the time of high–K+ exposure with the Trk inhibitor genistein at 100 µM (a) and the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 at 20 µM (b) but not by the p38 inhibitor SB203580 at 20 µM (c). *** and ### p < 0.001, * p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Fisher's LSD post-test. N is shown in each bar. (Online version in colour.)

(b) Electrophysiology

Axonal action potentials were evoked by pulses of extracellular current, generated from an A-M Systems (Carlsborg, WA, USA) DC isolated pulse stimulator model 2100, focused on a short segment of the nerve in the narrow slot between two small adjacent wells that each contained a silver stimulating electrode. The evoked action potentials were recorded, using an A-M Systems Neuroprobe amplifier Model 1600, in the somata of nociceptors identified by their location within the distinctive and homogeneous ventrocaudal nociceptor cluster within each pleural ganglion [26,27] using an intracellular recording electrode (glass pipette filled with 2000 mM KAc and 2000 mM KCl). Axon spike thresholds were tested with an ascending series of 5 msec current steps. Post-tests were given 1 h after the sensitizing depolarization treatment. All pretests and post-tests were performed in low-Ca2+ saline at room temperature. These tests and the sensitizing depolarization treatment were conducted in saline containing low concentrations of Ca2+ in order to prevent contractions of the muscular sheath surrounding the nerve, which might alter the density of applied current during the axonal excitability tests. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ does not affect axonal hyperexcitability induced by sensitizing depolarization [15,30].

(c). Sensitizing depolarization treatment

Intense, transient depolarization of axons in a nerve segment was used to mimic the depolarization (to approx. 0 mV) that would be produced by severing the axon [15,30]. To do this, the nerve segment was depolarized by rapidly replacing the 1% - Ca2+ saline with high–K+/low–Ca2+ saline (containing, in mM: 0 NaCl, 470 KCl, 0.1 CaCl2 dihydrate, 66 MgCl2 hexahydrate, and 10 Tris buffer, pH 7.6). The nerve segment remained in the high–K+/low–Ca2+ saline for 2 min, after which it was washed out five times with 1% - Ca2+ saline. This was done on the same nerve segment from which we had previously obtained a baseline threshold. Sham controls received the same treatment but with fresh 1% - Ca2+ saline instead of high–K+/low–Ca2+ saline. When testing the MNK inhibitor eFT508, the tyrosine receptor kinase (Trk) inhibitor genistein, the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) inhibitor U0126 or the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor SB203580, the drug was made in low–Ca2+ saline (less than 100 nM) and applied to the same segment of the nerve that was electrically stimulated, where it remained for 15 min. Then, a solution with drug and the same concentration of ions as the high–K+/low–Ca2+ saline was applied for 2 min, after which it was washed out five times. Sham controls underwent the same treatment, but solutions were always replaced with fresh low–Ca2+ saline.

(d) Protein evolutionary conservation analysis

Aplysia eIF4E and MNK1 protein evolutionary conservation was analysed against human, mouse and Drosophila protein sequences. Protein sequences were acquired from NCBI protein database. Isoform 1 was chosen when multiple isoforms were available in the database. Protein sequences from different species were aligned with NCBI constraint-based multiple alignment tool (COBALT). Functional domain conservation was assessed against the previous literature [31–33].

(e) Data analysis

Data are shown as mean +/− standard error of the mean (SEM). All data were analysed using GraphPad Prism for Mac OSX v. 7. The statistical test used was one-way ANOVA with Fisher's LSD post-test.

3. Results

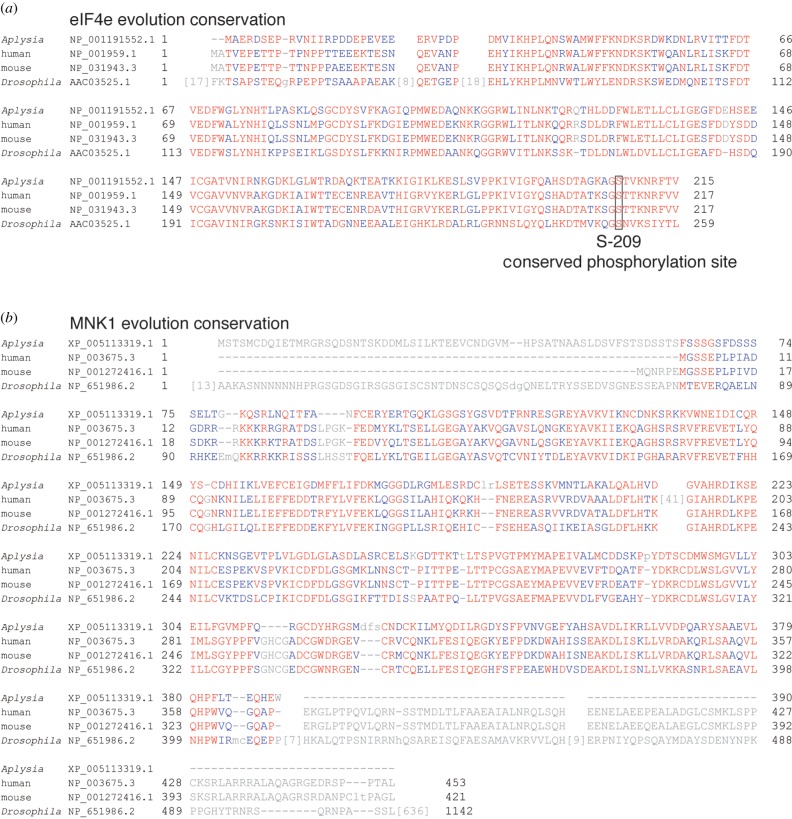

(a) Conservation of eIF4E and MNK1 in Aplysia

As a first test of our hypothesis that eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK is a core, evolutionarily conserved mechanism driving nociceptor sensitization we obtained eIF4E and MNK1 protein sequences from mouse, human, Aplysia and Drosophila and aligned them. Figure 1a shows high conservation of amino acid sequences in eIF4E with conservation across species of the serine phosphorylation site for MNK1. In the coding sequence of the gene, Aplysia eIF4E is 63% identical to human and mouse eIF4E isoform 1. It shows 52% identity to Drosophila. We also assessed MNK1 conservation finding that the kinase domain of MNK1 shows conservation across species (figure 1b). Looking at identity across the entire coding sequence Aplysia MNK is 43% identical to human MNK isoform 1 and 49% identical to mouse MNK isoform 1. It shows 28% identity to Drosophila Lk6 kinase isoform A which is an MNK homologue in this species. This conservation of MNK1-eIF4E signalling at the amino acid level suggests that pharmacological targeting of MNK with tools developed for mice and humans should be possible.

Figure 1.

Evolutionary conservation of Aplysia proteins eIF4E and MNK1. Protein sequences were obtained and aligned for mouse, human, Drosophila and Aplysia. (a) Conservation of the MNK phosphorylation site on eIF4E across species. (b) Conservation of the MNK1 coding sequence across species. Multiple sequence alignment columns with gaps are coloured in grey, while no gaps are coloured in blue or red. The blue and red colour code indicates less/highly conserved columns, respectively. Relative entropy threshold of 3 bits was used to determine level of conservation with a larger number indicating a higher degree of conservation. Relative entropy is calculated for each column as: , where i is residue type, fi is residue frequency observed in the multiple alignment column and pi is the background residue frequency. Residues with a relative entropy greater than or equal to 3 bits are coloured red. Conserved residues less than 3 bits are blue. (Online version in colour.)

(b) Depolarization-induced axonal hyperexcitability in Aplysia sensory neurons is attenuated by eFT508

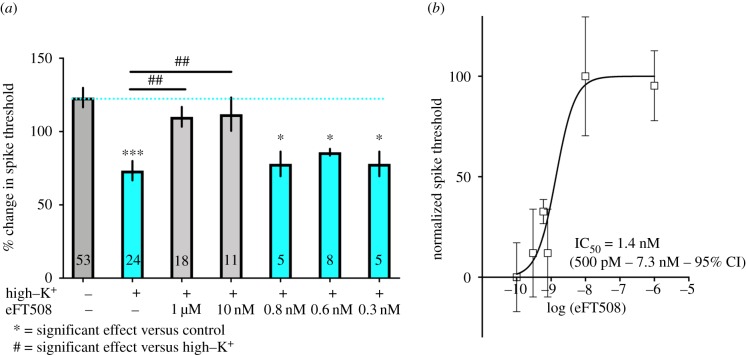

As an initial control, we tested changes in excitability of nociceptor axons monitored by recording action potentials from cell bodies in one of the two pleural ganglia after high – K+ treatment to the p9 nerve. We compared this to changes in excitability of nociceptor axons on the contralateral side where the p9 nerve was treated with normal saline. Action potential thresholds recorded intracellularly in the soma following test pulses applied to the p9 nerve were significantly decreased one hour after high–K+ treatment, but not 1 h after control treatment (figure 2a), as reported previously [15,30].

Figure 2.

eFT508 concentration-dependent inhibition of depolarization-induced axonal hyperexcitability. (a) Brief high–K+ treatment caused long-lasting hyperexcitability in axons of identified nociceptors and this effect was reversed by pre-treatment for 15 min and then co-treatment at the time of high–K+ exposure with eFT508 at 1 µM and 10 nM. Lower concentrations did not have an effect. *** p < 0.001, ## p < 0.01, and * p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Fisher's LSD post-test. N is shown in each bar. (b) Fitting the normalized concentration response curve of the effects of increasing concentrations of eFT508 yielded an EC50 of 1.4 nM. (Online version in colour.)

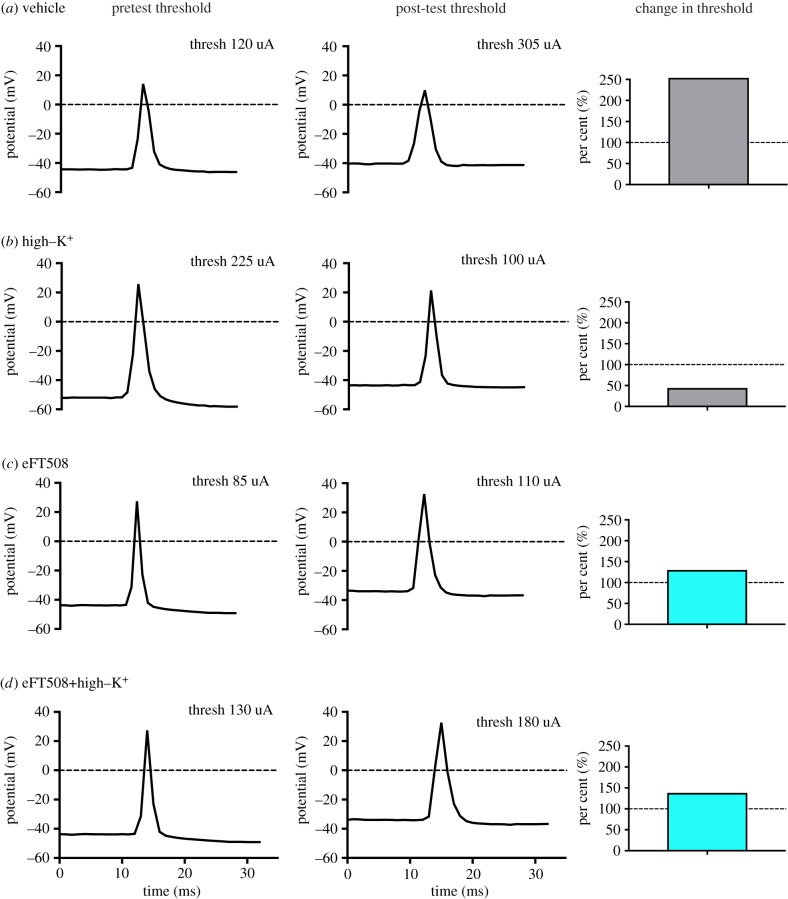

After confirming that high–K+ treatment could induce this form of sensitization, we asked whether the MNK inhibitor eFT508 could prevent the sensitization. Exposure to eFT508 (at 1 µM, and 10 nM) prior to high–K+ treatment prevented the decrease in action potential threshold in the post-test, and this effect was significant when compared to the control high–K+ treated nerve data (figure 2a). A significant effect was not observed at lower concentrations of drug (0.8, 0.6 and 0.3 nM). We used all of these data points to fit a concentration–response curve for eFT508 in this experimental paradigm. We found an EC50 of 1.4 nM (500 pM – 7.3 nM, 95% confidence interval (CI); figure 2b). This EC50 is strikingly similar to what has been found in mammalian systems [25] and is consistent with the conservation of MNK1 and eIF4E in invertebrates. Sample action potential traces are provided for all experimental conditions in figure 3. eFT508 did not have any effect on its own on axons not treated with high–K+.

Figure 3.

Example traces of eFT508 effect on axonal hyperexcitability. Pretest and post-test traces as well as changes in threshold are shown for (a) vehicle treatment, (b) High–K+ treatment, (c) eFT508 (10 nM) treatment and (d) eFT508 (10 nM) treatment + high–K+. Point 0 on the time scale is arbitrary, the scale is shown to accurately represent action potential width. (Online version in colour.)

(c) Aplysia sensory neuron axonal hyperexcitability is attenuated by Trk and ERK inhibitors but not by p38 MAPK

MNK is activated downstream of Trks and its direct upstream kinases are ERK and p38 MAPK [31,34,35], two important members of the MAPK signalling cascade that have both been implicated in chronic pain [36]. ERK contribution to chronic pain is linked to neurons [36] while p38 has been implicated in microglial and macrophage effects [37–40]. We used the same experimental paradigm described above and assessed whether the Trk inhibitor genistein, the MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 or the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 could inhibit sensitization induced by high–K+ treatment. Genistein (100 µM, figure 4a) and U0126 (20 µM, figure 4b) completely blocked the effects of high–K+ treatment but SB203580 (20 µM) did not have an effect (figure 4c). It is notable that previous experiments with lower concentrations of SB203580 have effects on Aplysia synaptic plasticity [41], indicating that this drug can target p38 in this species. These findings are consistent with findings from mice wherein a Trk–MEK/ERK–MNK1–eIF4E signalling axis drives nociceptor sensitization and development of chronic pain [13,14,23,24].

4. Discussion

The primary conclusion that we reach from this work is that MNK signalling is a key factor in the depolarization-induced hyperexcitability of Aplysia sensory neurons. Because our drug application was specific to the axonal compartment where the high–K+ treatment was also given, this demonstrates that MNK signalling controls axonal plasticity in this species. Because eIF4E is a conserved target of MNK across species, this suggests that MNK-eIF4E signalling is critical for axonal hyperexcitability effects observed here. This finding has strong parallels to previous experiments in mice where behavioural sensitization to a variety of pain-producing cytokines is also dependent on eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK [14,23,24]. Electrophysiological experiments have also provided evidence for a key role in MNK-mediated eIF4E phosphorylation in nociceptor sensitization in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons [13,23,42]. However, in the mouse, the experimental set-up we have used here is not possible owing to the relatively small size of mammalian nociceptors and the difficulty in creating a whole nerve ex-vivo preparation that can be kept intact for such long periods of time. This is a major advantage of this Aplysia model system in which sensitizing effects of intense nerve depolarization have been shown to last at least 24 h. Our evidence for localized MNK signalling controlling axonal hyperexcitability is an important extension of previous work on translation-dependent nociceptor plasticity in both Aplysia [15,43–47] and rodents [8,17–19,23,24,48–52].

Our finding that Trk and MEK/ERK signalling but not p38 signalling is also critical for this form of sensory neuron sensitization is consistent with previous work in the mammalian literature [36]. While MEK/ERK and p38 are both known to regulate pain sensitization, they do so through actions in different cell types. MEK/ERK activation in sensory neurons leads to the phosphorylation of ion channels [53–55] and also the downstream activation of MNK and eIF4E phosphorylation [23]. While p38 is known to phosphorylate eIF4E [31], the p38 contribution in the setting of pain sensitization occurs through microglial cells in the central nervous system, and macrophages in the periphery, albeit in a sex-specific fashion [38–40,56]. Sex is not a factor in Aplysia because they are hermaphrodites. Over the time course of the experiments done here, p38 did not have an effect on high–K+ treatment-induced sensitization. We conclude that a Trk–MEK/ERK–MNK signalling axis controls nociceptor sensitization in Aplysia and mice.

The experiments described here indicate a striking evolutionary conservation for how nociceptors become sensitized by injury and/or strong depolarization. Given that eIF4E is only phosphorylated at a single site by MNK, and this site is conserved across species, it is reasonable to conclude that injury-related phosphorylation of this single residue on eIF4E may play a critical role in protective behaviours driven by nociceptor sensitization across more than half a billion years of evolution. However, we cannot exclude other potential targets for MNK in the effects we have observed here because we have not created phosphorylation null mutants of eIF4E in Aplysia, as has been done in mice. In mice it is notable that the effects of MNK inhibition are mimicked by genetic manipulation of eIF4E phosphorylation, indicating that eIF4E is the key target for MNK effects on nociceptor plasticity in this species [13,14,23,24]. Translation regulation signalling is crucial for many different forms of neuronal plasticity, from intrinsic plasticity that governs nociceptor sensitization [8] to synaptic plasticity that is integrally involved in learning and memory [16]. Interestingly, while eIF4E phosphorylation is critical for intrinsic plasticity in nociceptors [13,14,23,24,42], it is almost certainly dispensable for synaptic plasticity mechanisms governing LTP and LTD [12,57]. This suggests that MNK-mediated eIF4E phosphorylation appeared early in evolution and remains a core regulator of injury-related sensory neuron plasticity, but has been a less important player in translation-dependent control of synaptic plasticity within the central nervous system.

Chronic pain is directly linked to nociceptor sensitization but is notoriously difficult to treat [4]. We propose that MNK – eIF4E signalling represents an intriguing therapeutic target for the treatment of chronic pain because it sits at the core of a signalling axis that regulates nociceptor sensitization with striking evolutionary conservation.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Price and Dussor laboratories for helpful comments on this project.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article will be supplied to qualified investigators upon request as Graphpad Prism files.

Authors' contributions

S.M.M. and K.K.K. did electrophysiological experiments. A.W. did computational experiments. J.K.M. contributed to electrophysiology experiments. E.T.W. and T.J.P. conceived of the project. S.M.M., A.W., K.K.K., E.T.W. and T.J.P. analysed data. S.M.M., A.W., E.W. and T.J.P. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant no. NS065926 to T.J.P.

References

- 1.Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. 2010. Nociceptors: the sensors of the pain pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3760–3772. ( 10.1172/JCI42843) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf CJ, Ma Q. 2007. Nociceptors–noxious stimulus detectors. Neuron 55, 353–364. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walters ET. 2018. Nociceptive biology of molluscs and arthropods: evolutionary clues about functions and mechanisms potentially related to pain. Front. Physiol. 9, 1049 ( 10.3389/fphys.2018.01049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price TJ, Gold MS. 2018. From mechanism to cure: renewing the goal to eliminate the disease of pain. Pain Med. 19, 1525–1549. ( 10.1093/pm/pnx108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price TJ, Inyang KE. 2015. Commonalities between pain and memory mechanisms and their meaning for understanding chronic pain. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 131, 409–434. ( 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crook RJ, Dickson K, Hanlon RT, Walters ET. 2014. Nociceptive sensitization reduces predation risk. Curr. Biol. 24, 1121–1125. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North R, et al. 2019. Electrophysiologic and transcriptomic correlates of neuropathic pain in human dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain 142, 1215–1226. ( 10.1093/brain/awz063) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khoutorsky A, Price TJ. 2018. Translational control mechanisms in persistent pain. Trends Neurosci. 41, 100–114. ( 10.1016/j.tins.2017.11.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. 2009. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136, 731–745. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wek RC, Jiang HY, Anthony TG. 2003. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 7–11. ( 10.1042/BST0340007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. 2012. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature 485, 109–113. ( 10.1038/nature11083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gkogkas CG, et al. 2014. Pharmacogenetic inhibition of eIF4E-dependent Mmp9 mRNA translation reverses fragile X syndrome-like phenotypes. Cell Rep. 9, 1742–1755. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.064) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Megat S, et al. 2019. Nociceptor translational profiling reveals the ragulator-rag GTPase complex as a critical generator of neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 39, 393–411. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2661-18.2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy JK, Khoutorsky A, Asiedu MN, Dussor G, Price TJ. 2018. eIF4E phosphorylation influences Bdnf mRNA translation in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 29 ( 10.3389/fncel.2018.00029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weragoda RM, Ferrer E, Walters ET. 2004. Memory-like alterations in Aplysia axons after nerve injury or localized depolarization. J. Neurosci. 24, 10 393–10 401. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2329-04.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. 2009. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron 61, 10–26. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geranton SM, Jimenez-Diaz L, Torsney C, Tochiki KK, Stuart SA, Leith JL, Lumb BM, Hunt SP. 2009. A rapamycin-sensitive signaling pathway is essential for the full expression of persistent pain states. J. Neurosci. 29, 15 017–15 027. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3451-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimenez-Diaz L, et al. 2008. Local translation in primary afferent fibers regulates nociception. PLoS ONE 3, e1961 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0001961) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price TJ, Rashid MH, Millecamps M, Sanoja R, Entrena JM, Cervero F. 2007. Decreased nociceptive sensitization in mice lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein: role of mGluR1/5 and mTOR. J. Neurosci. 27, 13 958–13 967. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4383-07.2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dowling RJ, et al. 2010. mTORC1-mediated cell proliferation, but not cell growth, controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science 328, 1172–1176. ( 10.1126/science.1187532) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efeyan A, Schweitzer LD, Bilate AM, Chang S, Kirak O, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM. 2014. RagA, but not RagB, is essential for embryonic development and adult mice. Dev. Cell 29, 321–329. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Chang S, Gumper I, Snitkin H, Wolfson RL, Kirak O, Sabatini DD, Sabatini DM. 2013. Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rag GTPases is necessary for neonatal autophagy and survival. Nature 493, 679–683. ( 10.1038/nature11745) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moy JK, et al. 2017. The MNK-eIF4E signaling axis contributes to injury-induced nociceptive plasticity and the development of chronic pain. J. Neurosci. 37, 7481–7499. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0220-17.2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moy JK, Kuhn J, Szabo-Pardi TA, Pradhan G, Price TJ. 2018. eIF4E phosphorylation regulates ongoing pain, independently of inflammation, and hyperalgesic priming in the mouse CFA model. Neurobiol. Pain 4, 45–50. ( 10.1016/j.ynpai.2018.03.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reich SH, et al. 2018. Structure-based design of pyridone-aminal eFT508 targeting dysregulated translation by selective mitogen-activated protein kinase interacting kinases 1 and 2 (MNK1/2) Inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 61, 3516–3540. ( 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01795) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walters ET, Bodnarova M, Billy AJ, Dulin MF, Diaz-Rios M, Miller MW, Moroz LL. 2004. Somatotopic organization and functional properties of mechanosensory neurons expressing sensorin-A mRNA in Aplysia californica. J. Comp. Neurol. 471, 219–240. ( 10.1002/cne.20042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters ET, Byrne JH, Carew TJ, Kandel ER. 1983. Mechanoafferent neurons innervating tail of Aplysia. I. Response properties and synaptic connections. J. Neurophysiol. 50, 1522–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters ET. 1987. Multiple sensory neuronal correlates of site-specific sensitization in Aplysia. J. Neurosci. 7, 408–417. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00408.1987) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walters ET, Alizadeh H, Castro GA. 1991. Similar neuronal alterations induced by axonal injury and learning in Aplysia. Science 253, 797–799. ( 10.1126/science.1652154) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunjilwar KK, Fishman HM, Englot DJ, O'Neil RG, Walters ET. 2009. Long-lasting hyperexcitability induced by depolarization in the absence of detectable Ca2+ signals. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 1351–1360. ( 10.1152/jn.91012.2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buxade M, Parra-Palau JL, Proud CG. 2008. The Mnks: MAP kinase-interacting kinases (MAP kinase signal-integrating kinases). Front. Biosci. 13, 5359–5373. ( 10.2741/3086) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukunaga R, Hunter T. 1997. MNK1, a new MAP kinase-activated protein kinase, isolated by a novel expression screening method for identifying protein kinase substrates. EMBO J. 16, 1921–1933. ( 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1921) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyronnet S, Imataka H, Gingras AC, Fukunaga R, Hunter T, Sonenberg N. 1999. Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) recruits mnk1 to phosphorylate eIF4E. EMBO J. 18, 270–279. ( 10.1093/emboj/18.1.270) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi S, Platanias LC. 2012. Mnk kinases in cytokine signaling and regulation of cytokine responses. Biomol. Concepts 3, 127–139. ( 10.1515/bmc-2011-1057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joshi S, Platanias LC. 2014. Mnk kinase pathway: cellular functions and biological outcomes. World J. Biol. Chem. 5, 321–333. ( 10.4331/wjbc.v5.i3.321) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji RR, Gereau R, Malcangio M, Strichartz GR. 2009. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res. Rev. 60, 135–148. ( 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji RR, Suter MR. 2007. p38 MAPK, microglial signaling, and neuropathic pain. Mol. Pain 3, 33 ( 10.1186/1744-8069-3-33) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mapplebeck JCS, et al. 2018. Microglial P2X4R-evoked pain hypersensitivity is sexually dimorphic in rats. Pain 159, 1752–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paige C, Maruthy GB, Mejia G, Dussor G, Price T. 2018. Spinal inhibition of P2XR or p38 signaling disrupts hyperalgesic priming in male, but not female, mice. Neuroscience 385, 133–142. ( 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.06.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taves S, Berta T, Liu DL, Gan S, Chen G, Kim YH, Van de Ven T, Laufer S, Ji RR. 2016. Spinal inhibition of p38 MAP kinase reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male but not female mice: sex-dependent microglial signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav. Immun. 55, 70–81. ( 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guan Z, Kim JH, Lomvardas S, Holick K, Xu S, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. 2003. p38 MAP kinase mediates both short-term and long-term synaptic depression in Aplysia. J. Neurosci. 23, 7317–7325. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07317.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black BJ, Atmaramani R, Kumaraju R, Plagens S, Romero-Ortega M, Dussor G, Price TJ, Campbell ZT, Pancrazio JJ. 2018. Adult mouse sensory neurons on microelectrode arrays exhibit increased spontaneous and stimulus-evoked activity in the presence of interleukin-6. J. Neurophysiol. 120, 1374–1385. ( 10.1152/jn.00158.2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casadio A, Martin KC, Giustetto M, Zhu H, Chen M, Bartsch D, Bailey CH, Kandel ER. 1999. A transient, neuron-wide form of CREB-mediated long-term facilitation can be stabilized at specific synapses by local protein synthesis. Cell 99, 221–237. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81653-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCamphill PK, Ferguson L, Sossin WS. 2017. A decrease in eukaryotic elongation factor 2 phosphorylation is required for local translation of sensorin and long-term facilitation in Aplysia. J. Neurochem. 142, 246–259. ( 10.1111/jnc.14030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montarolo PG, Goelet P, Castellucci VF, Morgan J, Kandel ER, Schacher S. 1986. A critical period for macromolecular synthesis in long-term heterosynaptic facilitation in Aplysia. Science 234, 1249–1254. ( 10.1126/science.3775383) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutton MA, Masters SE, Bagnall MW, Carew TJ. 2001. Molecular mechanisms underlying a unique intermediate phase of memory in Aplysia. Neuron 31, 143–154. ( 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00342-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weragoda RM, Walters ET. 2007. Serotonin induces memory-like, rapamycin-sensitive hyperexcitability in sensory axons of Aplysia that contributes to injury responses. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 1231–1239. ( 10.1152/jn.01189.2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melemedjian OK, et al. 2011. Targeting adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in preclinical models reveals a potential mechanism for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Mol. Pain 7, 70 ( 10.1186/1744-8069-7-70) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melemedjian OK, Asiedu MN, Tillu DV, Peebles KA, Yan J, Ertz N, Dussor GO, Price TJ. 2010. IL-6- and NGF-induced rapid control of protein synthesis and nociceptive plasticity via convergent signaling to the eIF4F complex. J. Neurosci. 30, 15 113–15 123. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3947-10.2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melemedjian OK, Mejia GL, Lepow TS, Zoph OK, Price TJ. 2014. Bidirectional regulation of P body formation mediated by eIF4F complex formation in sensory neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 563, 169–174. ( 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.09.048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melemedjian OK, Tillu DV, Moy JK, Asiedu MN, Mandell EK, Ghosh S, Dussor G, Price TJ. 2014. Local translation and retrograde axonal transport of CREB regulates IL-6-induced nociceptive plasticity. Mol. Pain 10, 45 ( 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.187) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Price TJ, Geranton SM. 2009. Translating nociceptor sensitivity: the role of axonal protein synthesis in nociceptor physiology. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 2253–2263. ( 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06786.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng SJ, Chen CC, Yang HW, Chang YT, Bai SW, Chen CC, Yen CT, Min MY. 2011. Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in synaptic transmission and plasticity of a nociceptive input on capsular central amygdaloid neurons in normal and acid-induced muscle pain mice. J. Neurosci. 31, 2258–2270. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5564-10.2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stamboulian S, Choi JS, Ahn HS, Chang YW, Tyrrell L, Black JA, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD. 2010. ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates sodium channel Na(v)1.7 and alters its gating properties. J. Neurosci. 30, 1637–1647. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-09.2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan J, Melemedjian OK, Price TJ, Dussor G. 2012. Sensitization of dural afferents underlies migraine-related behavior following meningeal application of interleukin-6 (IL-6). Mol. Pain 8, 6 ( 10.1186/1744-8069-8-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorge RE, et al. 2015. Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1081–1083. ( 10.1038/nn.4053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amorim IS, et al. 2018. Loss of eIF4E phosphorylation engenders depression-like behaviors via selective mRNA translation. J. Neurosci. 38, 2118–2133. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2673-17.2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article will be supplied to qualified investigators upon request as Graphpad Prism files.