Abstract

Background

Identifying patients with sentinel node‐negative melanoma at high risk of recurrence or death is important. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) recently developed a prognostic model including Breslow thickness, ulceration and site of the primary tumour. The aims of the present study were to validate this prognostic model externally and to assess whether it could be improved by adding other prognostic factors.

Methods

Patients with sentinel node‐negative cutaneous melanoma were included in this retrospective single‐institution study. The β values of the EORTC prognostic model were used to predict recurrence‐free survival and melanoma‐specific survival. The predictive performance was assessed by discrimination (c‐index) and calibration. Seeking to improve the performance of the model, additional variables were added to a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Some 4235 patients with sentinel node‐negative cutaneous melanoma were included. The median follow‐up time was 50 (i.q.r. 18·5–81·5) months. Recurrences and deaths from melanoma numbered 793 (18·7 per cent) and 456 (10·8 per cent) respectively. Validation of the EORTC model showed good calibration for both outcomes, and a c‐index of 0·69. The c‐index was only marginally improved to 0·71 when other significant prognostic factors (sex, age, tumour type, mitotic rate) were added.

Conclusion

This study validated the EORTC prognostic model for recurrence‐free and melanoma‐specific survival of patients with negative sentinel nodes. The addition of other prognostic factors only improved the model marginally. The validated EORTC model could be used for personalizing follow‐up and selecting high‐risk patients for trials of adjuvant systemic therapy.

In this study a prognostic model to predict survival of sentinel node‐negative melanoma patients was successfully validated. It could be used for personalizing follow‐up regimens and selecting high‐risk patients for trials of adjuvant systemic therapy.

Validated

Antecedentes

Es importante identificar a los pacientes con melanoma y ganglio centinela negativo con alto riesgo de recidiva o muerte. Con este fin, la European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) ha desarrollado recientemente un modelo pronóstico que incluye el índice de Breslow, la presencia de úlcera y la localización del tumor primario. Los objetivos del presente estudio fueron efectuar la validación externa de este modelo pronóstico y evaluar si pudiera mejorarse agregando otros factores pronósticos.

Métodos

Estudio retrospectivo de una sola institución, en el que se incluyeron 4.235 pacientes con melanoma cutáneo y ganglio centinela negativo. La mediana de seguimiento fue de 50 meses (rango intercuartílico 18,5‐81,5). Para predecir la supervivencia sin recidiva y la supervivencia específica para el melanoma se utilizaron los valores beta del modelo de pronóstico de la EORTC. La capacidad predictiva se evaluó mediante los índices de discriminación (índice c) y de calibración. Para mejorar el rendimiento de este modelo, se agregaron más variables utilizando un modelo de riesgos proporcionales de Cox.

Resultados

Las recidivas y muertes por melanoma fueron 793 (19%) y 456 (11%), respectivamente. La validación del modelo EORTC mostró una buena calibración para ambos resultados y un índice c de 0,69. El índice c sólo mejoró marginalmente a 0,71 cuando se agregaron otros factores pronósticos significativos (género, edad, tipo de tumor, índice mitótico).

Conclusión

La validación externa del modelo de pronóstico EORTC para la supervivencia sin recidiva y específica en pacientes con melanoma y ganglio centinela negativo fue satisfactoria. La adición de otros factores pronósticos solo mejoró marginalmente el modelo. El modelo validado de la EORTC podría utilizarse para personalizar las estrategias de seguimiento y seleccionar a pacientes de alto riesgo para ensayos con terapia sistémica adyuvante.

Introduction

Sentinel node biopsy (SNB) has become a standard staging procedure in patients with clinically localized primary cutaneous melanoma. The status of the sentinel node (SN) is the strongest independent prognostic factor in clinical stage I and II melanoma1. SN‐negative melanoma has a better survival rate than SN‐positive melanoma1, 2. However, a negative SN does not guarantee disease‐free survival, with reported recurrence rates in this group varying between 6 and 29 per cent3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. Initial trial results showed that adjuvant postoperative systemic therapies are effective for stage III melanoma, and trials with adjuvant programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors in high‐risk SN‐negative stage II melanoma have recently been initiated (NCT03553836 and NCT03405155)13, 14, 15, 16. As these drugs can have serious side‐effects, identifying patients who are at high risk of recurrence is important. Multiple smaller studies3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 17, 18 have identified risk factors for recurrence in SN‐negative melanoma. However, combining risk factors is essential when estimating the recurrence risk of an individual patient.

A recently published prognostic model and nomogram for recurrence and melanoma‐specific mortality addressed this issue11. This prognostic model was built using 3180 patients from four European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Melanoma Group centres, and included as parameters: Breslow thickness, ulceration and primary tumour site. Clinical prognostic models must be validated externally to ensure that the prediction is accurate and applicable to other populations19. This EORTC model has not yet been validated externally. Therefore, it is not known how applicable it is to other populations. The primary aim of the present study was to validate the EORTC model in a large external cohort of patients with SN‐negative melanoma. The secondary aim was to assess whether adding other known prognostic factors would improve the accuracy of the model.

Methods

This study used prospectively collected data from the database of Melanoma Institute Australia (MIA). Data were extracted from the MIA Research Database, with written informed patient consent and institutional review board approval (Sydney South West Area Health Service institutional ethics review committee Protocol Number X15‐0081).

Lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node biopsy

A SN was defined as a lymph node on the direct lymphatic drainage pathway from the primary tumour20. SNB was offered to patients without clinical evidence of metastatic disease whose melanoma was at least 1 mm thick, or thinner if adverse histopathological features were present, such as ulceration, Clark level IV or V, or a tumour mitotic rate of 1 per mm2 or higher. Technical details of lymphoscintigraphy and SNB at MIA have been described previously21, 22. In short, preoperative dynamic and static lymphoscintigraphy were done using 99mTc‐labelled antimony sulphide colloid. Since 2008 single‐photon emission CT with integrated CT has been added routinely. The biopsy was performed using Patent Blue dye and, since May 1995, a γ‐ray detection probe has also been employed. Pathologists examined multiple sections and used S100, human melanoma black 45 and, since 2010, MelanA immunohistochemistry23.

Data collection

Data on patient demographics (sex, age), primary tumour characteristics (location, Breslow thickness, Clark level, tumour type, ulceration, tumour mitotic rate, regression, lymphovascular invasion, vascular invasion), SN characteristics (number of SNs, drainage sites), recurrence (date, site and type of recurrence), type of treatment after recurrence and follow‐up (date of last follow‐up, status at last follow‐up) were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using median (i.q.r.) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics of the MIA cohort were compared with those of the EORTC cohort that was used to build the prognostic model. Comparison of continuous variables was done using the Mann–Whitney U test and categorical variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test. Melanoma‐specific survival (MSS) was calculated as the interval from initial diagnosis to melanoma‐related death. Patients who died from a non‐melanoma cause and those still alive at last follow‐up were censored. Recurrence‐free survival (RFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of recurrence or death from any cause. Censoring occurred at the end of follow‐up.

The final EORTC model for RFS and MSS included Breslow thickness (logarithmically transformed), ulceration and primary tumour site11. To assess model discrimination, Harrell's concordance index (c‐index) was calculated24. For each patient in the cohort, a risk score was calculated using the EORTC nomogram. Based on these risk scores, patients were classified as having a low risk (score 0–6), an intermediate risk (score 7–9) or a high risk (score 10 or more) of recurrence or melanoma‐specific death11. Kaplan–Meier curves were produced for each risk group. Internal validation was performed on the MIA cohort using the bootstrap method. Model calibration was assessed by plotting the predicted survival and recurrence against the observed frequency.

New co‐variables were added to investigate whether the predictive performance of the EORTC model could be improved. The AJCC acceptance criteria for individualized prognostic models were taken into account when building the model25. The following potential prognostic factors were selected based on clinical experience and literature review3, 5, 6, 11, 26, 27: sex, age, ulceration, Breslow thickness, primary tumour site, melanoma subtype, Clark level, tumour mitotic rate, regression, number of SN fields and total number of SNs. To address the possibility of a non‐linear association with outcomes, the continuous variables age and Breslow thickness were modelled by logarithmic transformation11. A full model was built with all variables with P ≤ 0·200 in univariable analysis. Variables were removed from the full model by backward stepwise elimination using the Akaike information criterion to achieve the smallest value28. Model performance was assessed with calibration plots and c‐indices. The proportional hazards assumption was checked for all variables using Schoenfeld residual plots and corresponding test statistics. P values were two‐sided and P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Between January 1992 and December 2015, 5443 patients with a clinically localized primary cutaneous melanoma underwent SNB at MIA. Of these, 4431 (81·4 per cent) were SN‐negative and 1012 (18·6 per cent) were SN‐positive. Patients were excluded if they had melanoma in situ (7), (micro)satellites (135), in‐transit metastases (10) or if preoperative ultrasound examination had revealed nodal metastasis (6). Thirty‐eight patients who participated in the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II and had a negative SN on histological assessment, but a positive reverse transcriptase–PCR finding in their SNs, were also excluded. Ultimately, 4235 patients were included in this study.

Cohort characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 4235 SN‐negative patients from MIA and 3180 in the EORTC cohort are shown in Table 1. Compared with the EORTC cohort, patients in the MIA cohort were significantly more often male (58·2 versus 52·5 per cent; P < 0·001), and had more head and neck melanomas (16·9 versus 8·1 per cent; P < 0·001). Superficial spreading melanoma was more common in the EORTC cohort, whereas patients at MIA presented more frequently with desmoplastic melanomas (P < 0·001). The MIA cohort more often had SNs in multiple node fields (18·9 versus 13·0 per cent; P < 0·001), and had more SNs identified and removed (median 2 versus 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the model development and validation cohorts

| EORTC (n = 3180) | MIA (n = 4235) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) * | 55 (44–67) | 58 (47·5–68·5) | |

| Sex | < 0·001 | ||

| M | 1668 (52·5) | 2463 (58·2) | |

| F | 1510 (47·5) | 1772 (41·8) | |

| Missing | 2 (0·1) | 0 (0) | |

| Primary tumour site | < 0·001 | ||

| Head and neck | 259 (8·1) | 716 (16·9) | |

| Upper limb | 556 (17·5) | 844 (19·9) | |

| Lower limb | 996 (31·3) | 1060 (25·0) | |

| Trunk | 1360 (42·8) | 1615 (38·1) | |

| Missing | 9 (0·3) | 0 (0) | |

| Breslow thickness * | 1·7 (1·1–3·0) | 1·8 (1·0–2·6) | |

| Tumour mitotic rate (per mm 2 ) * | n.a. | 3·0 (0·5–5·5) | |

| 0 | 39 (1·2) | 417 (9·8) | < 0·001 |

| ≥ 1 | 112 (3·5) | 3631 (85·7) | |

| Missing | 3029 (95·3) | 187 (4·4) | |

| Ulceration | 0·944 | ||

| No | 2264 (71·2) | 2890 (68·2) | |

| Yes | 788 (24·8) | 1002 (23·7) | |

| Missing | 128 (4·0) | 343 (8·1) | |

| Melanoma subtype | < 0·001 | ||

| Superficial spreading melanoma | 1739 (54·7) | 1731 (40·9) | |

| Nodular melanoma | 885 (27·8) | 1295 (30·6) | |

| Acral lentiginous melanoma | 93 (2·9) | 62 (1·5) | |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 139 (4·4) | 85 (2·0) | |

| Other | 46 (1·4) | 442 (10·4) | |

| Missing | 278 (8·7) | 620 (14·6) | |

| Clark level | < 0·001 | ||

| I–II | 271 (8·5) | 58 (1·4) | |

| III | 1230 (38·7) | 1147 (27·1) | |

| IV | 1354 (42·6) | 2615 (61·7) | |

| V | 140 (4·4) | 326 (7·7) | |

| Missing | 185 (5·8) | 89 (2·1) | |

| Regression | |||

| None | n.a. | 1228 (29·0) | |

| Early/intermediate | n.a. | 2011 (47·5) | |

| Late | n.a. | 348 (8·2) | |

| Missing | n.a. | 648 (15·3) | |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| No | n.a. | 3371 (79·6) | |

| Yes | n.a. | 81 (1·9) | |

| Missing | n.a. | 783 (18·5) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||

| No | n.a. | 2876 (67·9) | |

| Yes | n.a. | 77 (1·8) | |

| Missing | n.a. | 1282 (30·3) | |

| Total no. of SNs * | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | |

| Drainage site of identified SNs | |||

| Axilla | n.a. | 2215 (52·3) | |

| Groin | n.a. | 1174 (27·7) | |

| Neck | n.a. | 794 (18·7) | |

| Other | n.a. | 52 (1·2) | |

| No. of drainage sites | |||

| 1 | n.a. | 3436 (81·1) | |

| 2 | n.a. | 717 (16·9) | |

| 3 | n.a. | 73 (1·7) | |

| 4 | n.a. | 9 (0·2) | |

| No. of SN fields | < 0·001 | ||

| 1 | 2768 (87·0) | 3436 (81·1) | |

| > 1 | 412 (13·0) | 799 (18·9) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r). EORTC, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; MIA, Melanoma Institute Australia; n.a., not available; SN, sentinel node.

Pearson's χ2 test.

Recurrence and survival

The median duration of follow‐up was 50 (i.q.r. 18·5–81·5) months. Melanoma recurred in 793 patients (18·7 per cent), with a median time to recurrence of 26 (i.q.r. 8·5–43·5) months. A first recurrence occurred 5 years or more after the diagnosis of melanoma in 144 of these patients (18·2 per cent) and 28 patients (3·5 per cent) had their first recurrence after 10 years or more. Regional node recurrence was seen in 192 patients (24·2 per cent) and 335 (42·2 per cent) had a distant site as the first site of recurrence. The incidence of false‐negative SNB, defined as a regional nodal recurrence in a patient whose SNs had been found to be tumour‐free, was 15·9 per cent. There were 456 deaths from melanoma (10·8 per cent). The MSS rates at 5 and 10 years were 88·6 (95 per cent c.i. 87·4 to 89·8) and 80·3 (78·3 to 82·3) per cent respectively. The respective RFS rates at 5 and 10 years were 79·6 (78·2 to 81·0) and 70·8 (68·8 to 72·8) per cent.

External validation and improvement of the EORTC model

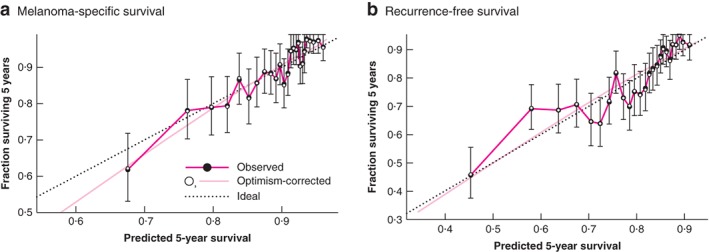

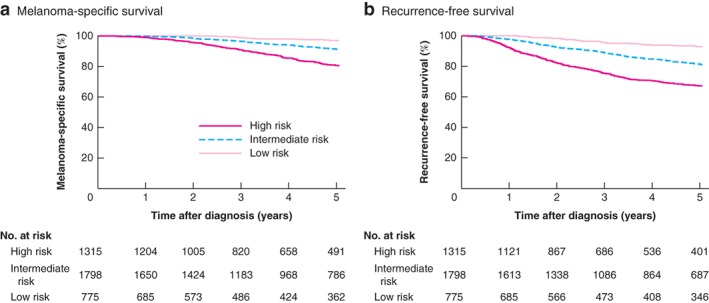

The predictive ability of the EORTC model was assessed by calculating the c‐index. The c‐indices of the externally validated EORTC model were 0·69 (95 per cent c.i. 0·67 to 0·71) and 0·69 (0·66 to 0·72) for RFS and MSS respectively. The prognostic models appeared well calibrated as the observed 5‐year survival rates were close to the predicted 5‐year rates (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves for the three risk classes.

Figure 1.

Calibration plots of the Cox proportional hazards model for the prediction of 5‐year recurrence‐free survival and melanoma‐specific survival a Melanoma‐specific survival and b recurrence‐free survival. a Bootstrap used 200 replications based on observed rate minus predicted rate. Mean absolute error = 0.009, 90th percentile = 0.013. b Bootstrap used 200 replications based on observed rate minus predicted rate. Mean absolute error = 0.009, 90th percentile = 0.014. Error bars denote 95% c.i. of the observed rate.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots for the low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk groups a Melanoma‐specific survival and b recurrence‐free survival.

Eight potential prognostic factors for RFS and MSS were added to the EORTC models: sex, age, melanoma subtype, Clark level, mitotic rate, regression, total number of SNs removed and number of SN fields. After backward selection, regression, Clark level, total number of SNs removed and multiple SN fields did not add enough to the prediction of outcomes to justify their inclusion in the final model. Table S1 (supporting information) shows the final model that included sex, age, melanoma subtype, tumour mitotic rate, Breslow thickness, ulceration and primary tumour site. The c‐index was 0·71 (0·69 to 0·73) for the RFS model and also 0·71 (0·68 to 0·74) for the MSS model.

Discussion

This single‐institution study validated the EORTC model for prediction of RFS and MSS in patients with SN‐negative melanoma. External validation is an essential step in assessing the generalizability of a prognostic model19, 25. As expected, the model performance was not as good as in the derivation data19. The c‐indices for the recurrence and melanoma‐specific mortality models were both 0·69 in the MIA population, compared with 0·74 and 0·76 in the EORTC cohort11. A c‐index of 0·69 means that the model correctly predicted recurrence or melanoma‐specific death in 69 per cent of the patients29.

The present cohort of patients with SN‐negative melanoma differed from the EORTC cohort with respect to several important clinicopathological characteristics. More of the present patients were men, more had head and neck primary melanomas, and the melanomas drained more frequently to multiple node fields and to more SNs. Tumours in the EORTC cohort had a lower Clark level in general and superficial spreading melanomas were more numerous. Despite these differences in patient characteristics, the EORTC model proved to be a strong predictive tool in the present population.

Simplicity is a strength of the EORTC model, as it is based on three common tumour characteristics. Although ease of use in clinical practice is important, this should not come at the cost of leaving out strong but more complex prognostic factors. The present study therefore investigated whether the model performance could be improved by adding co‐variables, and confirmed the independent prognostic value of sex, age, primary tumour site, Breslow thickness, ulceration, melanoma subtype and tumour mitotic rate. The tumour mitotic rate is one of the most important risk factors for recurrence and melanoma‐specific mortality26, 30. It was an essential part of the AJCC/UICC melanoma staging classification for almost 10 years2, 30. Smaller studies5, 8, 11, some with up to 95 per cent missing values, failed to show an association between tumour mitotic rate and survival in SN‐negative melanoma. In multivariable analysis, the present study confirmed the independent prognostic effect of this parameter. Another tumour characteristic of interest is regression. Regression has been found to be an independent prognostic factor for patients with melanoma in general27. In line with previous studies5, 6, independent prognostic value was not proven for SN‐negative melanoma in the present analysis. Adding sex, age, melanoma subtype and tumour mitotic rate to the EORTC model improved the predictive ability of the models by only 2 per cent (with overlapping confidence intervals). The authors consider that this improvement is insufficient to justify changing the simple EORTC model.

Only one other prognostic model for predicting recurrence in SN‐negative melanoma has been published3. In that study, combining Breslow thickness, ulceration and microsatellites yielded a c‐index of 0·75. Microsatellites are caused by lymphovascular dissemination and their presence is well known to be associated with worse survival31, 32. Patients with non‐nodal regional metastases (microsatellites, satellites or in‐transit metastases) are already regarded as high risk and should not have been included. According to the eighth edition of the AJCC melanoma staging system2, these patients are classified as having at least stage IIIB melanoma and are eligible for adjuvant systemic therapy.

The recurrence rate of 18·7 per cent in the present cohort is comparable to previously reported rates ranging from 6 to 29 per cent3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Importantly, all previous studies4, 6, 7, 11, 12 with a median follow‐up of at least 5 years reported a recurrence rate of over 14 per cent. The present study has shown that first recurrences are frequently (18·2 per cent) found after more than 5 years of follow‐up. Identifying these patients is important, as follow‐up is considered unnecessary after 5 years in some countries33. This prediction model could help in designing individualized follow‐up. As 42·2 per cent of all patients with a recurrence had their first relapse at a distant site, these patients with aggressive tumour biology might be those who could benefit most from adjuvant systemic therapy. The externally validated EORTC model could help to identify patients with the highest risk of recurrence or melanoma‐related death.

The present study has several limitations. Lymphatic invasion is a known prognostic factor in melanoma, but could unfortunately not be assessed reliably in this study because there were too many missing values (30·3 per cent)34, 35. The retrospective design and short follow‐up of some patients are other limitations.

This external validation confirmed the value of the EORTC prognostic model for RFS and MSS of SN‐negative melanoma. Addition of other known prognostic factors only marginally improved the model. The validated EORTC model can be used for patient counselling, personalizing follow‐up and selection of high‐risk patients for clinical trials of adjuvant systemic therapies.

Supporting information

Table S1. Updated model for prediction of recurrence‐free survival and melanoma‐specific survival

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from their colleagues at Melanoma Institute Australia and the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney. Particular thanks go to H. Burke for assistance with data extraction. G.V.L. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Practitioner Fellowship and the Melanoma Foundation of the University of Sydney. R.A.S. is supported by an Australian NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship. J.F.T. is supported by the Melanoma Foundation of the University of Sydney. This study was not preregistered in an independent, institutional registry.

N.A.I. had travel, accommodation and meeting expenses paid by Janssen‐Cilag and Novartis (not related to this work). R.A.S. received honoraria for advisory board membership from Merck Sharp Dohme, Novartis, Myriad and NeraCare (not related to this work). G.V.L. received honoraria for advisory board membership from Merck Sharp Dohme, Novartis, Array, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Amgen, Pierre Fabre and Incyte (not related to this work). J.F.T. received honoraria for advisory board membership from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp Dohme, Bristol Myers Squibb and Provectus (not related to this work).

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Nieweg OE, Roses DF et al; MSLT Group . Final trial report of sentinel‐node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI et al; for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform . Melanoma staging: evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 472–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bertolli E, de Macedo MP, Calsavara VF, Pinto CAL, Duprat Neto JP. A nomogram to identify high‐risk melanoma patients with a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward CE, MacIsaac JL, Heughan CE, Weatherhead L. Metastatic melanoma in sentinel node‐negative patients: the Ottawa experience. J Cutan Med Surg 2018; 22: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faut M, Wevers KP, van Ginkel RJ, Diercks GF, Hoekstra HJ, Kruijff S et al Nodular histologic subtype and ulceration are tumor factors associated with high risk of recurrence in sentinel node‐negative melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Egger ME, Bhutiani N, Farmer RW, Stromberg AJ, Martin RC II, Quillo AR et al Prognostic factors in melanoma patients with tumor‐negative sentinel lymph nodes. Surgery 2016; 159: 1412–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones EL, Jones TS, Pearlman NW, Gao D, Stovall R, Gajdos C et al Long‐term follow‐up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg 2013; 148: 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yee VS, Thompson JF, McKinnon JG, Scolyer RA, Li LX, McCarthy WH et al Outcome in 846 cutaneous melanoma patients from a single center after a negative sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2005; 12: 429–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gershenwald JE, Colome MI, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Tseng C, Lee JJ et al Patterns of recurrence following a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy in 243 patients with stage I or II melanoma. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 2253–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chao C, Wong SL, Ross MI, Reintgen DS, Noyes RD, Cerrito PB et al; Sunbelt Melanoma Trial Group . Patterns of early recurrence after sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Am J Surg 2002; 184: 520–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verver D, van Klaveren D, Franke V, van Akkooi ACJ, Rutkowski P, Keilholz U et al Development and validation of a nomogram to predict recurrence and melanoma‐specific mortality in patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes. Br J Surg 2019; 106: 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Connell EP, O'Leary DP, Fogarty K, Khan ZJ, Redmond HP. Predictors and patterns of melanoma recurrence following a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. Melanoma Res 2016; 26: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H et al Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL et al; CheckMate 238 Collaborators . Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1824–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, Atkinson V, Mandalà M, Chiarion‐Sileni V et al Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF‐mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1813–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, Long GV, Atkinson V, Dalle S et al Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1789–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zogakis TG, Essner R, Wang HJ, Foshag LJ, Morton DL. Natural history of melanoma in 773 patients with tumor‐negative sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14: 1604–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gambichler T, Scholl L, Bechara FG, Stockfleth E, Stücker M. Worse outcome for patients with recurrent melanoma after negative sentinel lymph biopsy as compared to sentinel‐positive patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 1420–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Altman DG, Royston P. What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med 2000; 19: 453–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nieweg OE, Tanis PJ, Kroon BB. The definition of a sentinel node. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 538–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verwer N, Scolyer RA, Uren RF, Winstanley J, Brown PT, de Wilt JH et al Treatment and prognostic significance of positive interval sentinel nodes in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 3292–3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Uren RF, Howman‐Giles R, Chung D, Thompson JF. Guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and F18 FDG PET scans in melanoma. J Surg Oncol 2011; 104: 405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scolyer RA, Murali R, McCarthy SW, Thompson JF. Pathologic examination of sentinel lymph nodes from melanoma patients. Semin Diagn Pathol 2008; 25: 100–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrell FE Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA; 247: 2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kattan MW, Hess KR, Amin MB, Lu Y, Moons KG, Gershenwald JE et al; members of the AJCC Precision Medicine Core . American Joint Committee on Cancer acceptance criteria for inclusion of risk models for individualized prognosis in the practice of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 370–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thompson JF, Soong SJ, Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Ding S, Coit DG et al Prognostic significance of mitotic rate in localized primary cutaneous melanoma: an analysis of patients in the multi‐institutional American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging database. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2199–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gualano MR, Osella‐Abate S, Scaioli G, Marra E, Bert F, Faure E et al Prognostic role of histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ambler G, Brady AR, Royston P. Simplifying a prognostic model: a simulation study based on clinical data. Stat Med 2002; 21: 3803–3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uno H, Cai T, Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Wei LJ. On the C‐statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Stat Med 2011; 30: 1105–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR et al Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6199–6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rao UNM, Ibrahim J, Flaherty LE, Richards J, Kirkwood JM. Implications of microscopic satellites of the primary and extracapsular lymph node spread in patients with high‐risk melanoma: pathologic corollary of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E1690. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2053–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. León P, Daly JM, Synnestvedt M, Schultz DJ, Elder DE, Clark WH Jr. The prognostic implications of microscopic satellites in patients with clinical stage I melanoma. Arch Surg 1991; 126: 1461–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trotter SC, Sroa N, Winkelmann RR, Olencki T, Bechtel M. A global review of melanoma follow‐up guidelines. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013; 6: 18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moy AP, Mochel MC, Muzikansky A, Duncan LM, Kraft S. Lymphatic invasion predicts sentinel lymph node metastasis and adverse outcome in primary cutaneous melanoma. J Cutan Pathol 2017; 44: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu X, Chen L, Guerry D, Dawson PR, Hwang WT, VanBelle P et al Lymphatic invasion is independently prognostic of metastasis in primary cutaneous melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 229–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Updated model for prediction of recurrence‐free survival and melanoma‐specific survival