ABSTRACT

Introduction

HIV+ patients have increased their life expectancy with a parallel increase in age-associated comorbidities and pharmacotherapeutic complexity. The aim of this study was to determine an optimal cutoff value for Medication regimen complexity index (MRCI) to predict polypharmacy in HIV+ older patients

Patients and methods

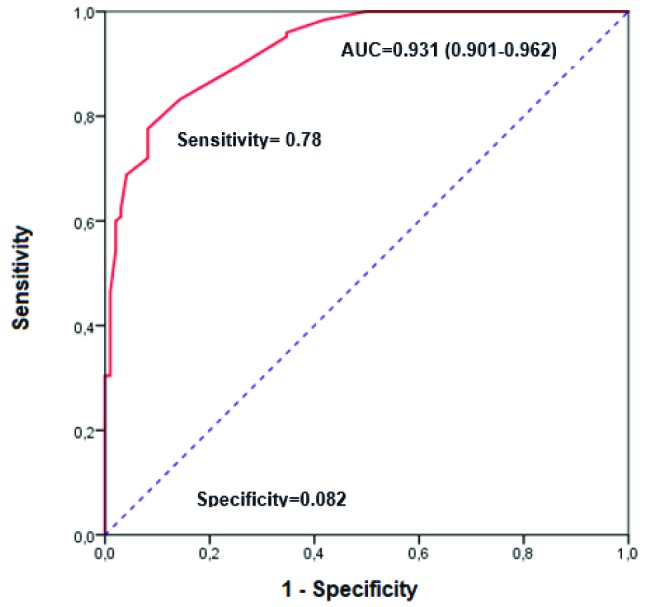

A transversal observational single cohort study was conducted at a tertiary Hospital in Spain, between January 1st up to December 31st, 2014. Patients included were HIV patients over 50 years of age on active antiretroviral treatment. Prevalence of polypharmacy and it pattern were analyzed. The pharmacotherapy complexity value was calculated through the MRCI. Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) for the MRCI value medications to determine the best cutoff value for identifying outcomes including polypharmacy. Sensitivity and specificity were also calculated.

Results

A total of 223 patients were included. A 56.1% of patients had polypharmacy, being extreme polypharmacy in 9.4% of cases. Regarding the pattern of polypharmacy, 78.0% had a cardio-metabolic pattern, 12.0% depressivepsychogeriatric, 8.0% mixed and 2.0% mechanical-thyroidal. The ROC curve demonstrated that a value of medication complexity index of 11.25 point was the best cutoff for predict polypharmacy (AUC=0.931; sensitivity= 77.6%; specificity= 91.8%).

Conclusions

A cut-off value of 11.25 for MRCI is proposed to determine if a patient reaches the criterion of polypharmacy. In conclusion, the concept of polypharmacy should include not only the number of prescribed drugs but also the complexity of them.

Keywords: HIV, polypharmacy, pharmacotherapy complexity, aging

RESUMEN

Introducción

La esperanza de vida de los pacientes VIH+ se ha incrementado. De forma paralela han aumentado las comorbilidades asociadas a la edad y la complejidad farmacoterapéutica. El objetivo del estudio es estimar el valor umbral del índice de complejidad de la farmacoterapia (MRCI) para la determinación del criterio de polifarmacia en pacientes VIH+ mayores de 50 años.

Métodos

Estudio observacional, trasversal, unicéntrico. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes VIH+ mayores de 50 años, en tratamiento antirretroviral activo entre el 1 enero y 31 diciembre-2015. Se determinó la presencia de polifarmacia y los patrones asociados. La complejidad del tratamiento se calculó con la herramienta MRCI (Universidad de Colorado). Se analizó el índice de complejidad total como marcador cuantitativo de polifarmacia mediante la realización de una curva ROC y el cálculo de su área bajo la curva. Se calculó la sensibilidad y la especificidad de la misma.

Resultados

Se incluyeron 223 pacientes. El 56,1% presentó polifarmacia, siendo extrema en el 9,4% de los casos. En relación con el patrón de polifarmacia, el 78,0% presentaron un patrón cardio-metabólico, el 12,0% psico geriátrico-depresivo, el 8,0% mixto y el 2,0% mecánico tiroideo .Se determinó un valor de área bajo la curva ROC de 0,931 con límites entre (0,901-0,962) y p< 0,001. El valor 11,25 de índice de complejidad total de la farmacoterapia proporcionó un valor de especificidad del 92% y una sensibilidad del 78%.

Conclusión

El valor de 11,25 de índice de complejidad es un buen indicador para conocer los pacientes con polifarmacia. El concepto de polifarmacia no solo debe incluir el número de fármacos que toma el paciente sino incluir también la complejidad del tratamiento.

Palabra clave: VIH, polifarmacia, complejidad farmacoterapéutica, envejecimiento

INTRODUCTION

Due to the introduction of high activity antiretroviral therapy, nowadays HIV-infected individuals live longer. It is estimated that by 2030 nearly three-quarters of people living with HIV will be 50 years or older [1]. Age-related conditions such as cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancers are likely to continue to increase among HIV-infected patients as their median age also increases [2]. As a result, up to two-thirds of these patients take concomitant medication to mitigate antiretroviral treatment (ART) side effects and/or to treat comorbid conditions [3–6]. People living with HIV (PLWH) often exhibits a higher number of concomitant medication than in the general population. This increase in drugs number has been associated with older age, female gender, obesity, and hepatitis B/C co-infection [4–6]. In addition, HIV-infected individuals may be more vulnerable to age-related conditions [7]. This high prevalence of comorbidities has only exacerbated the polypharmacy problem, which has recently become a clinical concern among providers caring for HIV-infected patients [3–5].

There are different definitions of polypharmacy. In numerical terms, it is most commonly defined as at least five or more prescription drugs, which is also associated to worse health outcomes in older patients such as increased risk for morbidity, non-adherence, drug interactions, and side effects. All these disadvantages have been shown to be more prevalent in PLWH than in the rest of the population [4, 6, 8–11]. In addition, Smit et al. observed an increasing burden of polypharmacy and age-related non-communicable diseases that could cause an increase in complications with first-line antiretroviral treatment [12].

According to the most recent recommendations in our context, the most appropriate number to define polypharmacy is six drugs [13]. However, no definition has included the impact of number of drugs, pill burden, complexity in taking drugs or other important factors including in the MRCI, in elderly patients, both HIV and non-HIV. Moreover, evidence shows that polypharmacy increases with age but is likely under-estimated given that most studies in HIV-infected adults only account for prescribed medicines [4, 10, 12]. Polypharmacy in HIV-infected has a major impact on ART adherence and adverse drug reactions leading to hospitalization [9, 14].

Polypharmacy should be considered the next challenge in clinical follow-up of HIV-infected patients [4, 12]. Strategies to decrease polypharmacy in complex patients with multiple comorbidities should prioritize decreasing the daily pill burden, the risk of toxicity and the drug-drug interactions [15]. New strategies have been developed alongside conventional triple combination ART administered as multi-tablet regimens. They include use of co-formulated, fixed-dose single-tablet regimens (STR) administered once daily, as well as nonpreferential less-drug regimens, which reduce the number of compounds administered to either monotherapy or dual combination therapy.

Another critical but less known factor is pharmacotherapy complexity (PC). Martin et al. developed a method for quantifying antiretroviral regimen complexity for HIV patients [16]. This method was the first step toward obtaining a better understanding of the impact of complex ART regimens on adherence and clinical outcomes. Previously, George et al. developed a medication regimen complexity index (MRCI) to estimate complexity of all drugs taken by a patient [17]. This tool has been used in many chronic diseases and most studies showed that an increased regimen complexity is associated with poor clinical outcomes and reduces medication in the general population [18, 19].

There are not published studies addressing the relationship between medication regimen complexity index and polypharmacy.

The aim of this study was to determine an optimal cutoff value for MRCI to predict polypharmacy and to redefine the concept of polypharmacy in older PLWH.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional, observational single cohort study was conducted at a tertiary Hospital in Spain, from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014. Patients enrolled in the study met the following inclusion criteria: HIV patients over 50 years of age on active ART drugs. Participants were given written information about the study and its objectives, and those who agreed to participate provided their written informed consent. Patients participating in another clinical trial or who did not sign the informed consent were excluded.

Data collected from the electronic medical record included demographic data (sex and age) and HIV transmission mode; clinical endpoints: plasma viral load (copies/milliliter [mL]) and CD4+ T-cell count (cells/microliter) and comorbidity related variables (number and type of comorbidities). Pharmacotherapy variables included ART regimen, single treatment regimen (STR) and concomitant medications. ART adherence was measured using the SMAQ questionnaire [20] and hospital dispensing records. A PLWH was considered adherent to antiretroviral treatment if according to hospital pharmacy records adherence was >95% and was not positive in the SMAQ, where positive means that there was a positive response to any of the qualitative questions of the SMAQ, more than two doses missed over the past week, or over 2 days of total non-medication during the past 6 months.

Adherence to concomitant medication was measured using the Morisky-Green questionnaire [21] and electronic pharmacy dispensing records. A PLWH was considered adherent to concomitant medication if according to electronic pharmacy dispensing records adherence was >90% and the Morisky-Green questionnaire scored 4.

To calculate the dispensing record, use the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR), as it measures the percentage of time a patient has access to medication. The formulae to calculate MPR is: MPR Number of days ARV prescribed or dispensed/ number of days in the interval. The follow-up time to the chronic medication adherence was 24 weeks.

The independent variable was polypharmacy, defined as treatment with six or more drugs (including antiretroviral therapy). Major polypharmacy (more than 11 drugs) and excessive polypharmacy (more than 21 drugs) were also considered [13].

Polypharmacy pattern was analyzed according to the Calderón Larrañaga et al study [22], with a non-random association in drug prescription resulting in polypharmacy patterns. Three patterns were applied based on age of participants: cardiovascular, depression-anxiety, and chronic obstructive pulmonary (COPD) disease patterns, with a different prevalence between men and women. A patient was classified into a pattern when at least three drugs of the treatment were in the same pattern. To calculate the corresponding polypharmacy patterns of each patient, drugs were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) using only the first three levels of the classification.

Multimorbidity patterns was analyzed according to the Prados-Torres et al study. Chronic diseases resulted in three multimorbidity patterns: cardiometabolic, depressivepsychogeriatric, and mechanical-thyroidal [23]. Patients were classified into a type if they had two diseases included in a pattern. ART drugs were obtained from a pharmacy-dispensing outpatient program (Dominion-Farmatools©). Non-ART drugs prescribed were provided by an electronic health prescription program of the Andalusian Public Health System. The remaining endpoints were obtained from laboratory tests, microbiology reports, and from the review of the medical history of each patient.

Finally, the pharmacotherapy complexity value was calculated through the MRCI [18]. This validated tool includes 65 items divided into three subgroups: dose forms, dosing frequencies, and additional instructions relevant to drug administration. The calculated value was obtained through the web tool of Colorado University available at http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/pharmacy/Research/researchareas/Pages/MRCTool.aspx) [24].

Statistical analyses. Quantitative variables were given as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR) in case of a skewed distribution. Qualitative variables were given as percentages (%).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) for the MRCI value medications to determine the best cutoff value for identifying outcomes including polypharmacy. The AUC describes the test’s overall performance and it can be used to compare different tests. An AUC of 1 indicates perfect discrimination, whereas an AUC of 0.5 indicates discrimination no better than chance. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated. The optimal cutoff point was obtained by using the Youden Index (i.e., sensitivity þ specificity-1), without adjusting for covariates. The Youden Index, a common summary measure of the ROC curve, represents the maximum potential effectiveness of a marker [25]. Logistic regression analysis was performed, and area under ROC curve was calculated for the association of the number of concomitant medications with each of the outcomes. Data are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All models were adjusted for potential covariates including age and medical conditions.

Statistical significance was set at less than 0.05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 software.

Ethics approval. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the South Seville area (registration number RAM-VIH-2015-02). Participants were given written information about the study and its objectives, and those who agreed to take part provided their written informed consent.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 223 patients with a median age of 53.0 years (IQR: 52.0-57.0), 86.5% males, were enrolled into the study. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in table 1. ART regimens consisted of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) plus a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) in 37.2% of patients; two NRTIs plus a boosted protease inhibitor in 18.8%; two NRTIs plus an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) in 12.6%, and other combinations in 31.4% of patients (20% monotherapy and 40% dual antiretroviral therapy). A majority (52%) of patients started antiretroviral therapy before 2002, 14.8% had been on three or more ART regimens and 25.3% had been on STR.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, clinic, related to lifestyle and adherence characteristics of the patients.

| Characteristics (n=223 patients) | ||

| Demographic Parameters | ||

| Gender (male); n (%) | 153 (86.5) | |

| Age (years); (median + IQR) | 53.0 (52.0-57.0) | |

| HIV risk factor; n (%) | IDU | 121 (54.3) |

| Sexual | 68 (30.5) | |

| Unknown | 34 (15.2) | |

| Clinic Parameters | ||

| Undetectable Plasmatic Viral Load (<50 cop/mL); n (%) | 184 (84.4) | |

| CD4 Levels; n (%) | <200 cells/μL | 22 (10) |

| ≥200 cells/μL | 198 (90) | |

| Adherence | ||

| Antiretroviral treatment; n (%) | 186 (83.6) | |

| Concomitant drugs; n (%) | 84 (37.9) | |

IQR: interquartile range; IDU: injection drug users.

Median number of concomitant drugs prescribed per patient were 3.0 (1.0-5.0). The median was the most frequently prescribed therapeutic drug classes were as follows: psychotropic drugs (35.9%), lipid lowering drugs (29.1%), cardiovascular agents (29.1%), drugs used for treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (26.9%), and blood glucoselowering drugs (11.7%).

The median of comorbidities per patient was 3.0 (IQR: 2.0- 4.0). Viral liver diseases were diagnosed in 67.3% of patients, cardiovascular diseases or high blood pressure in 25.0%, and central nervous system diseases in 20.5% of patients. Of the 126 patients who were calculated the multimorbidity pattern, 73.8% were cardiometabolic, 12.7% were mixed, 11.6% were depressive-psychogeriatric and 1.6% mechanical-thyroidal.

As regards the main variables, 56.1% of patients had polypharmacy, higher polypharmacy in 9.4% of cases and no patient had excessive polypharmacy. Of the 70 patients who were calculated the polypharmacy pattern, 60.0% were cardiovascular, 27.1% were depression-anxiety, 7.1 were mixed and 5.8 % were COPD.

Presence of polypharmacy was associated to higher PC values. Patients with high PC indices had a 50 times higher chance (p = 0.0001) of polypharmacy than those with low PC values. The PC index significantly correlated with the three index rating sections.

The ROC curve was constructed, and this demonstrated that a value of medication complexity index of 11.25 point was the best cutoff for predict polypharmacy in older HIVinfected patients (area under curve = 0.931; sensitivity of 77.6 % and specificity of 91.8%) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for polypharmacy in relation to the Medication Regimen Complexity Index value.

DISCUSSION

We propose a redefinition of the concept of polypharmacy, including not only the quantitative aspect of the number of prescribed drugs but, the medication regimen complexity. A cut-off value of 11.25 for MRCI is proposed to determine if a patient reaches the criterion of polypharmacy.

The cutoff established showed high AUC and specificity and moderate sensitivity which helps identifying more efficiently the presence of polypharmacy in older HIV-infected patients.

According to data published by others author [5, 10–12], our study demonstrates that a half of HIV+ elderly patients currently have polypharmacy. It is particularly important the number of patients who have higher polypharmacy, in our study 9.4%. Regarding the concept of polypharmacy, available literature points to different definitions. Although five medications have been generally a well-accepted criterion, according to most recent recommendations, we suggest six medications [13].

McNicholl et al. suggested that in patients 50 years and older, targeting individuals with 11 or more chronic medications would have the highest yield and greatest impact [26]. Sutton et al. in a retrospective HIV+ cohort studied a different concept, the pill burden. It was associated with poor level of adherence and risk of hospitalization but not included a proposal to analyse higher-risk patient based on this concept [27].

Given the increase in the number of patients older than 50 years expected in the coming years, as well as the increase in the number of patients with polypharmacy, our study indicates polypharmacy should be defined by the number and complexity of prescribed medication.

Additionally, the main contributing factor for a higher MRCI was concomitant medication. These results are in line with data published by Metz et al. [28]. This issue confirms the validity of the proposed cutoff.

Designing ART regimens that do not interact with other chronic medications or exacerbate comorbidities can be challenging, especially in heavily pretreated patients whose ART options are limited. A recent retrospective study found an association between polypharmacy, and a lower likelihood of using singled-tablet-regimen (STR) [15]. Currently available STR´s may be limited in this aging population by complex drug–drug and drug–disease interactions, and the desire to make treatment regimens more flexible but other strategies as Less-Drug-Regimen (LDR), including mono or bi-therapies, are becoming more frequent in this type of patients. Manzano et al. [29] demonstrated that the complexity of ART is being reduced mainly by new treatment strategies and the increasing appearance of pharmaceutical coformulations.

In addition, our results indicate that using MRCI scores adds information, particularly for concomitant drug prescribed, extending beyond a simple pill count or pill burden concept. More efforts should optimize to simplify concomitant medication

In this context, according to international guidelines, it will be possible that HIV specialty pharmacists may assist prescribers in reducing polypharmacy and identifying inappropriate prescribing, using Beers or STOPP-START tools [30].

A systematic review in non-HIV-infected patients has showed that although there was heterogeneity regarding the degree of association between complexity and adherence, most studies concluded that an increased regimen complexity reduces medication adherence [19]. In our study, the overall adherence calculated was high for ART, but particularly low for concomitant medication. T-+his suggests a prioritization of patients’ medication intake, derived from the patients’ beliefs and perceptions regarding medications [31]. These results suggested that, in older HIV patients, it is recommended that all prescribed medication be checked at least every six months in individuals who have more than four medications, and at least once a year for the rest [13]. According to guidelines, it is recommended to carry out a review of the prescribed pharmacotherapy in a systematized way and through a sequential and structured methodology [13]. Additionally, is necessary to go beyond the virologic suppression and ensure adequate control of comorbidities, among other things, improving adherence. Corless et al. raises the prospect that aid providers by guiding their motivational interview to those questions most closely associated with adherence, particularly knowing factors about self-efficacy, depression, stressful life events, and stigma. It is necessary that HIV+ knows pharmacotherapy objectives, not only ART, to be more implicated with this medication [32].

A common limitation of other published studies is that they only include data on medications of official medical prescriptions; they do not include private health system treatments or alternative medicines. However, this is not seen as a very significant limitation in our study; given the universal coverage of the public health system in Spain, with a small number of patients using alternative medications. However, the MRCI is an imperfect tool and faces tradeoffs between sensitivity and specificity, as most clinical measures do. Despite a long list of possible dose formulations, frequencies, and directions, some options are missed, such as once monthly and also missing details, such as how to code 2 once-daily medications that cannot be taken simultaneously. There exist other possibilities to analyse the PC as the antiretroviral regimen complexity Index (ARCI), which had many more such details. As the average complexity score is not significantly different from the MRCI for ART regimens we prefer to choose MRCI for being more studied in the literature, in the recent years [33–35].

Although a finding of multiple medication uses or polypharmacy, defined by a certain cutoff number may be a useful indication for a medication review in older adults, it may not be clinically useful when being associated with adverse outcomes. Instead, exposure to specific pharmacological drug classes, total medication exposure, drug-drug interactions, and medication adherence are important factors that may be used to be considered when evaluating individual’s risk for developing adverse outcomes.

Given the characteristics of our population and the pattern of polypharmacy and multimorbidity, coinciding with other published cohorts, our cutoff point offers strength, since it is based on the type of medication commonly used in this type of patient [5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 36].

Our study was not performed to use number of medications to claim that polypharmacy causes different adverse outcomes nor clinical impairment, but simply to determine an optimal discriminating number of medications for polypharmacy. Other important issues as geriatric syndromes, functional outcomes, and mortality in HIV+ older population must be studied, including an analysis using frailty, disability and mortality variables respectively.

It is known that multi-morbidity contributes to further vulnerability and complexity in clinical management in the contemporary ART age. The interest in methods to identify individuals at risk of multi-morbidity is strongest. The concept of frailty must be included routinely in HIV+ older patient because may be useful in discriminating whether it is the morbidities themselves or the toxicity of prescribed treatments that contributes more to adverse outcomes [26].

Given the changing face of the HIV epidemic, providers will be increasingly challenged to effectively manage older, HIV-infected patients with multi-morbidity, polypharmacy and high-level of PC. It is important to increase our knowledge of polypharmacy among the increasing older HIV-infected population in order to be able to develop prevention strategies for the problems inherent in old age and multiple treatments. According with the literature polypharmacy in HIV+ older patient will increase in the coming years [12]. This fact and the progressive physiological deterioration of patients will make it increasingly common and necessary to use not only the classic assessment of actual or potential drug interactions but also other terminology about the use of drugs employed in other types of chronic patients, such as potentially inappropriate medication, cholinergic risk or deprescribing [10–12, 26, 35].

Future researches efforts will focus on include risk assessment, such as that offered by the MRCI Index in our study, to inform the prioritization of medications according to their risks and benefits for each patient. In addition, efforts to promote public health and multidisciplinary initiatives, behavioral changes, and prevention aimed at reducing polypharmacy and MRCI should be investigated.

Additional studies are needed to establish its power and for revealing possible opportunities for clinical intervention to reduce MRCI as a risk factor for nonadherence and its consequence in the use of health resources, including hospitalizations, are proposed.

In conclusion, the concept of polypharmacy should include not only the number of prescribed drugs but also the complexity of them. The findings of this study provide evidence and clarification of the best cutoff value for the MRCI that should be used to identify HIV+ older patient at possible risk of polypharmacy.

FUNDING

None to declare.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Tseng A, Szadkowski L, Walmsley S, Salit I, Raboud J. Association of Age With Polypharmacy and Risk of Drug Interactions With Antiretroviral Medications in HIV-Positive Patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1429–39. doi: 10.1177/1060028013504075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, et al. HIV and Aging. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:S1–18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Sighem AI, Gras LAJ, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F, ATHENA national observational cohort study . Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:1527–35. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:613–28. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimeno-Gracia M, Crusells-Canales MJ, Javier Armesto-Gómez F, Rabanaque-Hernández MJ. Prevalence of concomitant medications in older HIV+ patients and comparison with general population. HIV Clin Trials. 2015;16:117–24. doi: 10.1179/1528433614Z.0000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, Weber R, Fux C, Furrer H, et al. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:413–23. doi: 10.3851/IMP1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negredo E, Back D, Blanco J-R, Blanco J, Erlandson KM, Garolera M, et al. Aging in HIV-Infected Subjects: A New Scenario and a New View. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5897298. doi: 10.1155/2017/5897298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcum ZA, Pugh MJ V., Amuan ME, Aspinall SL, Handler SM, Ruby CM, et al. Prevalence of Potentially Preventable Unplanned Hospitalizations Caused by Therapeutic Failures and Adverse Drug Withdrawal Events Among Older Veterans. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:867–74. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore HN, Mao L, Oramasionwu CU. Factors associated with polypharmacy and the prescription of multiple medications among persons living with HIV (PLWH) compared to non-PLWH. AIDS Care. 2015;27:1443–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1109583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gimeno-Gracia M, Crusells-Canales MJ, Armesto-Gomez FJ, Compaired-Turlan V, Rabanaque-Hernandez MJ. Polypharmacy in older adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection compared with the general population. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;Volume 11:1149–57. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S108072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JM, Flexner C. The challenge of polypharmacy in an aging population and implications for future antiretroviral therapy development. AIDS. 2017;31 Suppl 2:S173–84. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grupo de expertos de la Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre el SIDA (SPNS), Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología (SEGG). Documento de consenso sobre edad avanzada e infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana. 2015; Noviembre.

- 14.Cantudo-Cuenca MR, Jiménez-Galán R, Almeida-González C V., Morillo-Verdugo R. Concurrent Use of Comedications Reduces Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Patients. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:844–50. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guaraldi G, Menozzi M, Zona S, Calcagno A, Silva AR, Santoro A, et al. Impact of polypharmacy on antiretroviral prescription in people living with HIV. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:511–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin S, Wolters PL, Calabrese SK, Toledo-Tamula MA, Wood L V, Roby G, et al. The Antiretroviral Regimen Complexity Index. A novel method of quantifying regimen complexity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:535–44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811ed1f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George J, Phun Y-T, Bailey MJ, Kong DC, Stewart K. Development and Validation of the Medication Regimen Complexity Index. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1369–76. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libby AM, Fish DN, Hosokawa PW, Linnebur SA, Metz KR, Nair K V, et al. Patient-level medication regimen complexity across populations with chronic disease. Clin Ther. 2013;35:385-398.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pantuzza LL, Ceccato M das GB, Silveira MR, Junqueira LMR, Reis AMM. Association between medication regimen complexity and pharmacotherapy adherence: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:1475–89. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knobel H, Alonso J, Casado JL, Collazos J, González J, Ruiz I, et al. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA Study. AIDS. 2002;16:605–13. PMid: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. PMid: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderón-Larrañaga A, Gimeno-Feliu LA, González-Rubio F, Poblador-Plou B, Lairla-San José M, Abad-Díez JM, et al. Polypharmacy patterns: unravelling systematic associations between prescribed medications. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prados-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Gimeno-Feliu LA, González-Rubio F, Poncel-Falcó A, et al. Multimorbidity Patterns in Primary Care: Interactions among Chronic Diseases Using Factor Analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Universidad de Colorado. Electronic Data Capture and Coding Tool for Medication Regimen Complexity. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/pharmacy/Research/researchareas/Pages/MRCTool.aspx.

- 25.Ruopp MD, Perkins NJ, Whitcomb BW, Schisterman EF. Youden Index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom J. 2008;50:419–30. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNicholl IR, Gandhi M, Hare CB, Greene M, Pierluissi E. A Pharmacist-Led Program to Evaluate and Reduce Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Older HIV-Positive Patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:1498–506. doi: 10.1002/phar.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott Sutton S, Magagnoli J, Hardin JW. Impact of Pill Burden on Adherence, Risk of Hospitalization, and Viral Suppression in Patients with HIV Infection and AIDS Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:385–401. doi: 10.1002/phar.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metz KR, Fish DN, Hosokawa PW, Hirsch JD, Libby AM. Patient-Level Medication Regimen Complexity in Patients With HIV. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1129–37. doi: 10.1177/1060028014539642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzano-García M, Robustillo-Cortés A, Almeida-González C V, Morillo-Verdugo R. [Evolution of the Complexity Index of the antiretroviral therapy in HIV+ patients in a real life clinical practice]. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2017;30:429–35. PMid: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer JJ, Gill TK, Sherman EM, McNicholl IR. ASHP Guidelines on Pharmacist Involvement in HIV Care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:468–94. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haro Márquez C, Cantudo Cuenca MR, Almeida González CV, Morillo Verdugo R. [Patients’adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions in HIV patients]. Farm Hosp. 2015;39:23–8. doi: 10.7399/fh.2015.39.1.8127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corless IB, Hoyt AJ, Tyer-Viola L, Sefcik E, Kemppainen J, Holzemer WL, et al. 90-90-90-Plus: Maintaining Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapies. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31:227–36. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirsch JD, Metz KR, Hosokawa PW, Libby AM. Validation of a patient-level medication regimen complexity index as a possible tool to identify patients for medication therapy management intervention. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:826–35. doi: 10.1002/phar.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wimmer BC, Cross AJ, Jokanovic N, Wiese MD, George J, Johnell K, et al. Clinical Outcomes Associated with Medication Regimen Complexity in Older People: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:747–53. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nozza S, Malagoli A, Maia L, Calcagno A, Focà E, De Socio G, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in geriatric HIV patients: the GEPPO cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guaraldi G, Brothers TD, Zona S, Stentarelli C, Carli F, Malagoli A, et al. A frailty index predicts survival and incident multimorbidity independent of markers of HIV disease severity. AIDS. 2015;29:1633–41. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]