Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Aloe vera is known for its antioxidant properties. In this experimental study, we aimed to investigate the efficacy of Aloe vera in ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) liver injury in rats.

METHODS:

Male Wistar Albino rats were divided into three groups, where the sham group (n=7) underwent no medication or surgical procedures, the I/R group (n=7) was the control group that received 45 minutes of applied abdominal aorta ischemia and rats were sacrificed 24 hours after reperfusion, and the I/R+AV group (n=7) was the treatment group that was given Aloe vera (30 mg/kg) every day followed by gastric lavage for a month before applying ischemia and performing sacrifice as in the previous group. Before sacrifice, all the liver tissues were removed. Tissues were examined for histopathological investigation, iNOS immunoreactivity and tissue biochemistry, malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activities.

RESULTS:

The SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px levels of the I/R+AV group were not significantly different from the sham group (p>0.05) but were significantly higher when compared to the I/R group. MDA levels of liver tissues were significantly lower (p<0.05) in the I/R+AV group as compared to the I/R group. Disrupted hepatic cords, sinusoidal dilatation, hemorrhage, cytoplasmic vacuolization of hepatocytes, and intensive iNOS immunoreactivity were detected in the I/R group. Decreased histopathological change score and iNOS immunoreactivity score were noticed in the I/R+AV group as compared to the I/R group.

CONCLUSION:

It was found that Aloe vera showed a hepatoprotective effect against I/R injury. Further research is required to determine the effective dose, administration method, and effects of Aloe vera for liver transplantation.

Keywords: Aloe vera, hepatoprotective, ischemia-reperfusion, rat

Organ damage due to reperfusion after temporary ischemia is related to many clinical tableaux. I/R injury occurs during a variety of surgical interventions like organ transplants and coronary bypasses and due to diseases, such as stroke, shock, and cardiac infarcts. The destructive effects of I/R injury result in direct tissue damage due to a variety of events with harmful effects at the cellular level and linked inflammation, the formation of acute reactive oxygen radicals (ROS) following re-oxygenation, cell death, and organ failure [1–3].

I/R injury in the liver causes a biphasic response in the form of acute and subacute phases. The acute phase is observed 3– 6 hours after reperfusion and is characterized by free radical formation and activation of T-lymphocytes and Kupffer cells. The response in the subacute phase is intense neutrophil infiltration and is observed 18–24 hours after reperfusion [2]. When examined histopathologically, I/R injury causes cellular swelling, vacuolization, destruction of endothelial cells, and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration [4]. The nitric oxide (NO) synthase family forms a range of enzymes causing oxidative deamination of L-arginine and NO formation. Induced NO-synthase (iNOS) is one of these enzymes, which causes increased levels of NO during inflammatory events by contributing to NO synthesis. iNOS testing is possible in tissues by immunohistochemical staining [5].

In organisms, ROS are natural products that occur as a result of oxygen metabolism. They have a small molecular structure that has a destructive effect on other cells when they are produced in quantities above the antioxidant capacity of the body. Reperfusion of the ischemic liver involves exposure to high levels of ROS, and I/R injury is one of the best examples of this situation. When the balance between ROS and antioxidants is disrupted, oxidative stress occurs. The leading enzymes with protective effects against ROS are superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). When the levels of these types of protective enzymes and molecules reduce, ROS increases and forms a critical situation. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a toxic metabolite formed by lipid peroxidation that develops after ischemia and reperfusion and is the most important marker of lipid peroxidation [6–8].

Preventing I/R injury to the liver carries great importance for healing after liver transplants and treatment of severe liver disease. This is because patients with I/R injury are more liable to suffer from mortal complications due to the development of a variety of pathophysiological processes that cause Kupffer cell activation and increase the levels of ROS, inflammatory mediators, and cytokines [9, 10]. There are a variety of studies proving that antioxidants are beneficial for I/R injury [3, 6, 11–13].

Aloe vera (AV) is a semi-tropical plant from the Liliaceae family with a broad range of application in traditional medications [14]. It has been shown that AV has strong antioxidant and antimicrobial properties due to the phenolic compounds it contains. AV gel has almost two hundred bioactive ingredients such as minerals, vitamins, proteins, lipids, amino acids, and polysaccharides [15, 16]. It has proven to be an effective treatment agent in many diseases ranging from asthma and ulcers to wound healing and cancer [17]. We have shown that AV is effective against different tissue ischemia-reperfusion injuries in various studies that we have conducted previously [18, 19]. Although AV has some healing effects on liver damage, no study has been done to date to determine whether it can prevent liver from ischemia-reperfusion damage, especially following organ transplantation. This study researched whether AV, known for its antioxidant and antiinflammatory effects, has a protective effect on I/R injury induced in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After receiving permission from the Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University Animal Experiments Local Ethics Committee (decision no: 2014/13-1) a total of 21 male Wistar Albino rats, aged 8–12 weeks and weighing 250–300 g, were enrolled in the study. During the study, the rats were housed in special cages with appropriate feeding conditions and under controlled temperature (23°C –25°C) and lighting (12 hours light, 12 hours dark), with ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were randomly divided into three groups of seven individuals:

Sham group (n=7): Underwent laparotomy and observation only (No I/R and no treatment) to neutralize the effects of surgery and anesthesia.

I/R group (n=7): Control group; underwent laparotomy and liver I/R, but AV was not given.

I/R+AV group (n=7): Treatment group; underwent laparotomy and liver I/R and AV was given.

AV was obtained from Herbalife Turkish distributor (Herbalife Inc, Istanbul, Turkey). It is used by many people as food supplements.

Dosage: In this study, we decided the dose of Aloe vera as 30 mg/kg body weight on the basis of studies that used 10–120 mg/kg/day doses to reveal the therapeutic effects of AV [18–24]. Since we have previously demonstrated the efficacy of AV at a dose of 30 mg/kg, a single-dose trial was deemed appropriate for use in this study.

Experimental Procedure

Anesthesia for all groups used xylazine (Bayer, Istanbul, Turkey) 5 mg/kg and ketamine hydrochloride (Parke Davis, Istanbul, Turkey) 50 mg/kg, with spontaneous respiration at room temperature. The rats were placed in the supine position on the operating table under sterile conditions and a skin and subdermal midline incision was opened. Intestines were pushed to the right and the abdominal aorta was accessed via the midline incision. In groups with induced ischemia, the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava were carefully dissected and separated from each other. The abdominal aorta was clamped from the lower section of the renal artery that turns immediately above the bifurcation. After 45 minutes of clamping, the clamps were removed, and reperfusion ensued. The abdomen was closed appropriately. Rats in all groups were sacrificed 24 hours later by administration of a high dose anesthetic, Ketamine (50 mg/kg). Immediately before the sacrifice, all liver tissues were fully removed. Half of the tissue was stored in formaldehyde. Histopathological investigations, iNOS immunoreactivity and malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) tissue biochemistry tests exposed to ischemia were performed as stated below.

Biochemical Investigations of Rat Liver Tissues

After macroscopic analysis, rat tissues were kept at − 80 °C. Tissues for biochemical analysis were homogenized in the appropriate buffer separately for each method and supernatants were removed. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activities, and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels of rat liver tissues were duplicated and measured with highly sensitive ELISA spectrophotometry. The protein concentrations were indicated by the Bradford method using Bradford reagent (Sigma Aldrich, Bradford reagent-B6916-1KT, USA). All the data was defined as the mean±standard deviation (SD) based on each milligram of protein.

Tissue SOD activities were measured with the SOD assay kit (Biovision-K335-100; Milpitas, CA95035, USA) using highly sensitive ELISA spectrophotometry. The IC50 (50% inhibition activity of SOD) values were determined by this colorimetric method under 450 nm. The results were expressed as U/mL SOD per milligram protein (U/mL.mg protein).

CAT activity of rat liver tissues was determined with a commercial colorimetric kit, the S-341 Cell Biolabs’ OxiselectTM Catalase Activity Assay Kit. The results, measured using highly sensitive ELISA spectrophotometry, were expressed as U/mL CAT per milligram protein (U/mL.mg protein).

Liver tissue GPx activities were measured with a commercial Glutathione Peroxidase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit (Biovision-K762-100; Milpitas, CA95035, USA) using highly sensitive ELISA spectrophotometry. The results were expressed as U/mL GPx per milligram protein (mU/mL.mg protein).

Lipid peroxidation was determined by the reaction of malondialdehyde (MDA) with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to form a colorimetric (532 nm) product, proportional to the MDA present. The Lipid Peroxidation Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit (Biovision-K739-100; Milpitas, CA95035, USA) was used to determine MDA levels. The results were expressed as nmole MDA per milligram tissues (nmole/mg tissue).

Statistical Analysis

Results were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA). Differences among the groups were obtained using Turkey’s test. Statistical significance was accepted as p<0.05. All the data was expressed as mean ± SD in each group.

Histopathological Examination

For histopathological examination, liver tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 48 hours. After fixation, tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 µm sections by a microtome (Slee, 5061). Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). H&E-stained sections were examined under a light microscope (Olympus CX41) by two histopathologists blind to the grouping of the animals, who used different magnifications to detect liver injury. Histopathological changes of sinusoidal dilatation, hemorrhage, and vacuolization were assessed in the liver tissue. Tissue damage was graded and scored as follows; 0: normal histological appearance, 1: mild, 2: moderate, and 3: severe.

Immunohistochemical Examination

For examination of iNOS immunoreactivity in liver tissue, paraffin-embedded liver tissue was cut into 5 µm segments and deparaffinized in xylene, following which it was rehydrated in graded series by ethanol. Sections were washed in phosphate buffer saline and boiled in a citrate buffer using a microwave oven at 90°C–100°C for 10 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with H2O2 and sections were transferred to normal goat serum to block nonspecific binding. Then sections were incubated with primary antibody (Anti-iNOS, ab15323) in a humidified chamber at room temperature for 1 hour. After incubation of anti-iNOS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody and streptavidin peroxidase (Ultra Vision Detection System-HRP kit, Thermo Scientific/Lab Vision) at room temperature for 10 minutes, respectively. Chromogen 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazole (AEC Substrate System, Thermo Scientific/Lab Vision) was applied, and the sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin. Anti-iNOS immunoreactivity was examined and scored semi-quantitatively from 0 to 3 as follows; 0: none, 1: weak, 2: moderate, and 3: intense for each liver tissue.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using the SPSS 16.0 statistical software package for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). The results were reported as mean±SD. Groups were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for binary comparisons. The Spearman correlation test was used to evaluate the relationship between the variables histologically. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

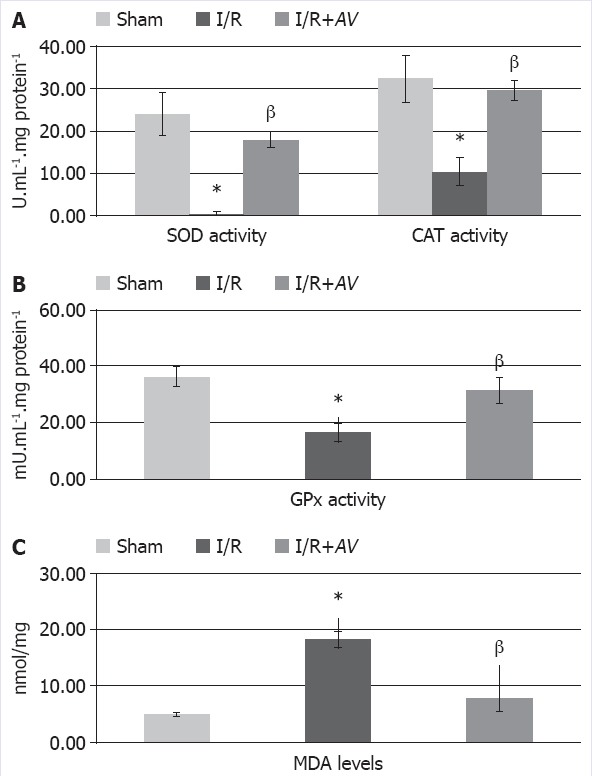

The mean and SD values of SOD, CAT, GPx, and MDA in all groups are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. SOD, CAT, and GPX levels of I/R group (0.57±0.42, 10.40±3.35, and 16.43±3.26 U/ml.mg protein, respectively) were found to be lower as compared to the other groups, and this was statistically significant (p<0.05). SOD, CAT, and GPX levels of I/R+AV group (17.97±1.99, 29.60±2.28, and 31.14±4.65 U/ml.mg protein, respectively) were not significantly different from the sham group (p>0.05) but were significantly higher when compared to the I/R group. In the same way, MDA levels of liver tissues were significantly lower (p<0.05) in the I/R+AV group (7.70±2.30 nmol/mg tissue) as compared to the I/R group (18.30±1.46 nmol/mg tissue).

TABLE 1.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activities, and levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) of rat liver tissues

| Groups | SOD (U/ml.mg protein) Mean±SD | CAT (U/ml.mg protein) Mean±SD | GPx (U/ml.mg protein) Mean±SD | MDA (nmol/mg tissue) Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | ||||

| Sham group | 24.03±5.11 | 32.36±5.41 | 36.10±3.59 | 4.99±0.29 |

| I/R | 0.57±0.42* | 10.40±3.35* | 16.43±3.26* | 18.30±1.46* |

| I/R+AV | 17.97±1.99ß | 29.60±2.28ß | 31.14±4.65ß | 7.70±2.30ß |

SD: Standard deviation; I/R: Ischemia reperfusion; AV: Aloe vera. The notations * and ß are significantly different with respect to the One-way ANOVA-Tukey’s test in each column (p<0.05).

FIGURE 1.

The effects of aloe vera therapy on superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) (A), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (B) activities and levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) (C) of rat liver tissues. Aloe vera therapy groups are significantly different compared to the ischemia groups (p<0.05).

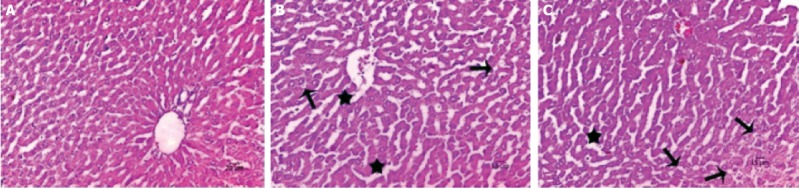

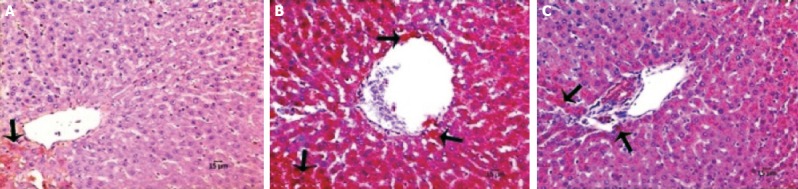

As revealed in Figure 2, normal liver architecture was observed in the sham group. Disrupted hepatic cords, sinusoidal dilatation, hemorrhage, cytoplasmic vacuolization of hepatocytes, and intensive iNOS immunoreactivity was detected in the I/R group. Decreased histopathological change score and iNOS immunoreactivity score was noticed in the I/R+AV group (Table 2, p<0.05). iNOS immunoreactivity was clearly decreased in I/R+AV group as compared to the I/R group (p<0.05). Immunohistochemical findings of the groups are presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining of liver tissue. (A) Sham group showing normal histological appearance, (B) I/R group showing disrupted hepatic cord and vacuolization, and (c) I/R+AV showing minimal sinusoidal dilation and vacuolization (H&E, 200X, arrow; cytoplasmic vacuolization, star; disrupted hepatic cords, arrowhead; hemorrhage).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of histopathological changes and iNOS immunoreactivity scores of groups

| Group | Sinusoidal dilatation | Hemorrhage | Cytoplasmic vacuolization | iNOS immunoreactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | |

| Sham group | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7±0.4 |

| I/R | 2.7±0.4a | 2.4±0.5a | 2.3±0.4a | 2.8±0.4a |

| I/R+AV | 1.5±0.5a,b | 1.2±0.6a,b | 1.5±0.5a,b | 1.2±0.4a,b |

iNOS: Induced NO-synthase; SD: Standard deviation; I/R: Ischemia reperfusion; AV: Aloe Vera; aCompared with Control group (p<0.05); bCompared with I/R group (p<0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of liver tissue with Anti-iNOS. (A) Sham, (B) I/R, (C) I/R+AV. AV-treated groups showing decreased iNOS immunoreactivity. (Hematoxylin counterstain, 200X, arrow; iNOS positive cells).

DISCUSSION

Liver transplantation is a commonly used treatment method for congenital and acquired disorders of the liver [2]. I/R injury in liver transplantation is closely related to nonfunctional or dysfunctional graft development and may result in graft rejection. ROS and reactive nitrogen radicals (RNS) play an important role during I/R injury by intracellular calcium overload and many cellular factors. In this situation, the consumption of endogenous antioxidants due to the release of ROS and RNS causes apoptotic and necrotic cell death. Among endogenous intracellular antioxidants, catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and allopurinol are the most well-known. iNOS is released by endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and Kupffer cells and is an enzyme that is active independent of calcium. iNOS has protective and toxic effects on the effect linked to the type of stimulus, iNOS expression levels, and duration [6, 25].

Many extracellular antioxidant agents have been shown to have beneficial effects for treatment of liver I/R injury. Examples of these include α-tocopherol, ascorbate, coenzyme Q, pentoxifylline, lipoic acid, quercetin, cyanidin, green tea extract, N-acetylcysteine, catalase derivatives, allopurinol, and aminoguanidine. Many clinical and experimental studies on these types of antioxidants have produced different results, which may be linked to the type of subjects used in the study, the method of administration, duration and dose of the antioxidant agent used, duration of ischemia, and many other factors [6].

Currently, AV is used widely in food and drinks, pharmaceutical material, and cosmetics. Aloe species are generally used worldwide due to its anti-tumor, antiinflammatory, antioxidant, and laxative effects [14, 26]. An experimental study on rats showed that AV had a neuroprotective effect on the sciatic nerve in I/R injury [27]. To date, though many studies have used Aloe vera, there is no study that investigated the protective effect of AV on I/R injury in the liver.

In a study of the effects of AV gel against oxidative stress-induced liver damage, it was determined that AV reduced the formation of lipid peroxidation [28]. Also, when the effects of AV were examined on nephrotoxicity in rabbits, it was determined to have increased the total antioxidant status, reduced the total oxidant status, and increased serum catalase levels due to increased doses of AV [29]. AV has favorable effects on the antioxidant enzyme levels of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. When superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and glutathione s-transferase enzyme levels of rats administered with AV were compared to rats given glibenclamide as a reference antidiabetic drug, the results were not significantly different. AV was effective on enzyme levels similar to glibenclamide and the antioxidant enzyme levels were increased as compared to diabetic rats [30]. In this study, it was found that catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase enzyme levels in rats administered with AV were significantly greater than in rats in the I/R group. The MDA levels in the AV group were significantly lower than in the I/R group. Our results suggest that AV’s antioxidant levels are beneficial for I/R injury of the liver.

It was seen that the iNOS expression levels are decreased in the AV-treated rats in the liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride [31]. Also, in our previous study, we have shown by histopathological examination that the increase in the level of nNOS with damage caused by cerebral ischemia was decreased by AV effect. nNOS levels of the I/R+AV group (36.71±5.15) were found to be lower as compared to the I/R group (62.71±11.91) [19]. Histopathological investigation revealed that the negative effects linked to I/R injury in the AV group were improved by the administration of a certain amount of AV. iNOS immunoreactivity was significantly lower in the AV group as compared to the I/R group, which supports the hepatoprotective effect of AV on I/R injury.

When we consider that oxidative stress plays a role in countless diseases, it becomes important to determine a direct and in vivo effect on oxidative damage. Currently, oxidative stress is shown by new biological markers, and of these, allantoin measured in urine is promising [32]. In our study, the newly discovered oxidative stress markers were not examined, and this was a limiting factor. There is a need to develop new agents with fewer side effects to replace these medications. We believe that more studies will be beneficial to patients and clinicians in determining the administration dose, method, and possible effects of herbal material with proven antioxidant activity like AV.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Animal Experiments Local Ethics Committee (Decision no: 2014/13-1)

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interests.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Authorship Contributions: Concept – MHS; Design – MHS, HAK; Supervision – MHS; Materials – MHS, HAK, IK, AK; Data collection and/or processing – MHS, IK; Analysis and/or interpretation – MHS, IK; Writing – MHS, AK; Critical review – MHS, AK, HAK.

REFERENCES

- 1.Montalvo-Jave EE, Escalante-Tattersfield T, Ortega-Salgado JA, Piña E, Geller DA. Factors in the pathophysiology of the liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2008;147:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan C, Zwacka RM, Engelhardt JF. Therapeutic approaches for ischemia/reperfusion injury in the liver. J Mol Med (Berl) 1999;77:577–92. doi: 10.1007/s001099900029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouad AA, El-Rehany MA, Maghraby HK. The hepatoprotective effect of carnosine against ischemia/reperfusion liver injury in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;572:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Busuttil RW. Ischemia and reperfusion injury in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1653–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapral M, Wawszczyk J, Sośnicki S, Węglarz L. Down-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by inositol hexaphosphate in human colon cancer cells. Acta Pol Pharm. 2015;72:705–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glantzounis GK, Salacinski HJ, Yang W, Davidson BR, Seifalian AM. The contemporary role of antioxidant therapy in attenuating liver ischemia-reperfusion injury:a review. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1031–47. doi: 10.1002/lt.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halladin NL. Oxidative and inflammatory biomarkers of ischemia and reperfusion injuries. Dan Med J. 2015;62:B5054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cichoż-Lach H, Michalak A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8082–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abcouwer SF, Lin CM, Shanmugam S, Muthusamy A, Barber AJ, Antonetti DA. Minocycline prevents retinal inflammation and vascular permeability following ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:149. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhai Y, Shen XD, O'Connell R, Gao F, Lassman C, Busuttil RW, et al. Cutting edge:TLR4 activation mediates liver ischemia/reperfusion inflammatory response via IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent MyD88-independent pathway. J Immunol. 2004;173:7115–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giakoustidis D, Papageorgiou G, Iliadis S, Giakoustidis A, Kostopoulou E, Kontos N, et al. The protective effect of alpha-tocopherol and GdCl3 against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Surg Today. 2006;36:450–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang WH, Li JY, Zhou Y. Melatonin abates liver ischemia/reperfusion injury by improving the balance between nitric oxide and endothelin. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:574–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Váli L, Stefanovits-Bányai E, Szentmihályi K, Fébel H, Sárdi E, Lugasi A, et al. Liver-protecting effects of table beet (Beta vulgaris var. rubra) during ischemia-reperfusion. Nutrition. 2007;23:172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gamboa-Gómez CI, Rocha-Guzmán NE, Gallegos-Infante JA, Moreno-Jiménez MR, Vázquez-Cabral BD, González-Laredo RF. Plants with potential use on obesity and its complications. EXCLI J. 2015;14:809–31. doi: 10.17179/excli2015-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdul Qadir M, Shahzadi SK, Bashir A, Munir A, Shahzad S. Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Some Common Herbs. Int J Anal Chem. 2017;2017:3475738. doi: 10.1155/2017/3475738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moghaddasi MS. Aloe verachemicals and usages. Advances in Environmental Biology. 2010:464–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olusegun A. One hundred medicinal uses of Aloe vera. Good health Inc:Lagos. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Yu BP, Herlihy JT. The influence of long-term Aloe vera ingestion on age-related disease in male Fischer 344 rats. Phytother Res. 2002;16:712–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guven M, Yuksel Y, Sehitoglu MH, Akman T, Aras AB, Cosar M. Aloe veraameliorates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Arch Clin Exp Surg. 2016;5:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Cao L, Du G. Protective effects of Aloe vera extract on mitochondria of neuronal cells and rat brain. [Article in Chinese] Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2010;35:364–8. doi: 10.4268/cjcmm20100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirshafiey A, Aghily B, Namaki S, Razavi A, Ghazavi A, Ekhtiari P, et al. Therapeutic approach by Aloe vera in experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2010;32:410–5. doi: 10.3109/08923970903440184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parihar MS, Chaudhary M, Shetty R, Hemnani T. Susceptibility of hippocampus and cerebral cortex to oxidative damage in streptozotocin treated mice:prevention by extracts of Withania somnifera and Aloe vera. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu ZQ, Deng YJ, Lu JX. Effect of aloe polysaccharide on caspase-3 expression following cerebral ischemiaand reperfusion injury in rats. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:371–4. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anilakumar KR, Sudarshanakrishna KR, Chandramohan G, Ilaiyaraja N, Khanum F, Bawa AS. Effect of Aloe vera gel extract on antioxidant enzymes and azoxymethane-induced oxidative stress in rats. sIndian J Exp Biol. 2010;48:837–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiraz HA, Poyraz F, Kip G, Erdem Ö, Alkan M, Arslan M, et al. The effect of levosimendan on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Libyan J Med. 2015;10:29269. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v10.29269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eshun K, He Q. Aloe vera:a valuable ingredient for the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries-a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2004;44:91–6. doi: 10.1080/10408690490424694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guven M, Gölge UH, Aslan E, Sehitoglu MH, Aras AB, Akman T, et al. The effect of aloe vera on ischemia-Reperfusion injury of sciatic nerve in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;79:201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nahar T, Uddin B, Hossain S, Sikder AM, Ahmed S. Aloe veragel protects liver from oxidative stress-induced damage in experimental rat model. J Complement Integr Med. 2013;10 doi: 10.1515/jcim-2012-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iftkhar A, Hasan IJ, Sarfraz M, Jafri L, Ashraf MA. Nephroprotective Effect of the Leaves of Aloe barbadensis(Aloe Vera) againstToxicity Induced by Diclofenac Sodium in Albino Rabbits. West Indian Med J. 2015;64:462–7. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2016.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajasekaran S, Sivagnanam K, Subramanian S. Antioxidant effect of Aloe vera gel extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:90–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SH, Cheon HJ, Yun N, Oh ST, Shin E, Shim KS, et al. Protective effect of a mixture of Aloe vera and Silybum marianum against carbon tetrachloride-induced acute hepatotoxicity and liver fibrosis. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:119–27. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08189fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czerska M, Mikołajewska K, Zieliński M, Gromadzińska J, Wąsowicz W. Today's oxidative stress markers. Med Pr. 2015;66:393–405. doi: 10.13075/mp.5893.00137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]