Abstract

Approximately half of patients presenting with myocardial infarction are found to have non-infarct related multi-vessel severe coronary artery disease. Various observational studies and randomized controlled trials have been conducted to assess if revascularization of non-infarct related artery is associated with better clinical outcomes. In this review, the authors discuss the various revascularization strategies in patients with multi-vessel disease who present with myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease, Mortality, Myocardial Infarction, Percutaneous coronary intervention

1. Introduction

Approximately 50% of patients presenting with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are found to have one or more non-infarct related severe coronary artery disease at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[1] Angiographic coronary multi-vessel disease (MVD) is associated with worse short and long term prognosis. For example, in a pooled analysis of eight randomized clinical trials of primary PCI and thrombolysis, the presence of non-infarct related artery (IRA) disease was associated with increased 30-day mortality when compared to patients without non-IRA disease (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.79, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.51–2.12).[1] One study of about 1000 patients showed that patients undergoing primary PCI with MVD had an increased all-cause mortality (HR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.32–2.51) at a median follow-up of 51 months.[2]

The prevalence of MVD in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) is reportedly higher (approximately 40%–80%).[3] MVD has been shown to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality. This risk has remained consistently high for years, with overall mortality in MVD patients being greater than individuals with single vessel disease (10.2% vs. 5.9%, P = 0.012).[4] These findings led researchers to investigate whether revascularization of the non-IRA improves overall prognosis in these patients.

2. MVD revascularization in STEMI

Between 2001 and 2014, numerous observational studies have reported on the conundrum of whether to revascularize the non-IRA.[5]–[21] These observational studies suggested that multi-vessel revascularization may be harmful. In a pooled analysis of these studies, IRA only revascularization was associated with a non-significant reduction in long-term mortality (odds ratio (OR) = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.62–1.09).[22] Based on these observations, previous guidelines have recommended against PCI of non-IRA (Class III), at the time of primary PCI, in patients presenting with STEMI if the IRA is identified.[23]

The findings of these observational studies have been largely refuted by moderate sized randomized trials. The first of these trials was the Preventive Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction (PRAMI) Trial in the United Kingdom.[24] A total of 465 STEMI patients were randomized to immediate IRA and non-IRA vessel (complete revascularization) or PCI to IRA only. The primary outcome was a composite of cardiac death, non-fatal MI, or refractory angina. At a mean follow-up of 23 months, the trial was terminated early due to a significantly better primary outcome in the complete revascularization group (HR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.21–0.58), driven by a reduction in the risk of repeat revascularization (6.8% vs. 19.9%, P < 0.001), reduction in nonfatal MI (3% vs. 8.7%, P = 0.009), and refractory angina (5.1% vs. 13.0%, P = 0.002). In this trial, it was noted that the events were reduced early on with a complete revascularization approach, and the reduction in the composite outcome was remarkable in the complete revascularization arm, which was mainly due to early termination of the trial.

Another moderate-sized RCT, the Randomized Trial of Complete versus Lesion-Only Revascularization in Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for STEMI and Multi-Vessel Disease[25] (The CvLPRIT Trial). This was a multi-center randomized controlled study including 296 patients in seven United Kingdom centers. In most cases of multi-vessel PCI (68%), revascularization of the non-IRA lesion was performed during the index procedure. The primary outcome was a composite of mortality, heart failure, recurrent MI, and ischemia-driven revascularization. At 12 months, the primary composite outcome occurred in 10% in the complete revascularization group versus 21% in the IRA only group (HR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.24–0.84), which again was due to a reduction in ischemia driven or urgent revascularization, but no difference in the risk of hard end points such as mortality and MI. At a median follow-up of 7 years, patients who underwent complete revascularization continued to have a lower risk of the primary outcome (HR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.38–0.87). Additionally, the combined endpoint of MI and mortality was lower with complete revascularization (HR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.29–0.97). Notably, there was no difference in the outcomes between the complete revascularization group and IRA only revascularization group beyond 12 months.[26]

In both the PRAMI and CvLPRIT trials, the severity of the non-IRA was assessed angiographically and both studies did not incorporate physiological assessment of lesion severity using fractional flow reserve (FFR). There had been some concerns regarding the use of FFR at the time of acute coronary syndrome due to microvascular dysfunction;[27] however, studies demonstrated that FFR is reliable and can guide the revascularization decision for non-IRA.[28] This was taken into account in the DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI Trial (Complete Revascularization versus Treatment of the Culprit Lesion Only in Patients with ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multi-Vessel Disease),[29] which enrolled 627 patients in the Denmark with a median follow-up of 27 months. STEMI patients with MVD were randomized to IRA only PCI or FFR-guided revascularization of the non-IRA, performed electively 2–3 days after primary PCI (i.e., staged procedure). The primary endpoint which was the composite of re-infarction, ischemia-driven revascularization of non-IRA, and all-cause mortality occurred in 22% of patients who underwent PCI of IRA and 13% of patients with complete revascularization (HR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.38–0.83); this was again driven by a reduction in ischemia-driven revascularization (HR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.18–0.53; P < 0.0001), but not by hard outcomes as mortality and MI.

The Compare-Acute Trial,[30] compared FFR-guided complete revascularization during the index procedure versus IRA-only PCI. The trial randomized 885 STEMI patients and the primary outcome was non-fatal MI, any revascularization, cerebrovascular events, and death. At a 12-month follow-up, the primary outcome occurred in 7.8% of patients in the complete-revascularization group and 20.5% of patients in the IRA group (HR = 0.35; 95% CI: 0.22–0.55). This difference was driven by the higher number of revascularization that occurred in the IRA only group (HR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.20–0.54). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI; however, a non-significant reduction in the individual endpoints was observed. This study has also demonstrated the feasibility of an FFR guided approach for revascularization of the non-IRA, even in the acute setting (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the major trials comparing complete revascularization with infarct related artery only revascularization in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease.

| Trial | Year | N | Complete revascularization approach | Major adverse cardiac events | All-cause mortality | Re-infarction | Urgent revascularization |

| PRAMI[23] | 2013 | 234/231 | Index | 21/53 | 12/16 | 7/20 | 16/46 |

| CvLPRIT[24] | 2015 | 150/146 | Index (67%), staged prior to hospital discharge (33%) | 15/31 | 2/6 | 0/2 | 7/12 |

| DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI[28] | 2015 | 314/313 | Staged 2 days after index PCI | 40/68 | 15/11 | 15/16 | 17/52 |

| COMPARE-ACUTE[29] | 2017 | 295/590 | Index (83%), staged prior to hospital discharge (17%) | 23/121 | 4/10 | 7/28 | 18/103 |

| COMPLETE[35] | 2019 | 2016/2025 | Staged: 64% prior to discharge (median 1 day), 36% after discharge (median 23 days) | 179/339 | 96/106 | 109/160 | 29/160 |

Events in complete revascularization/Events in infarct related artery only revascularization.

These four trials (i.e., PRAMI, CVLPRIT, DANAMI-3-PRI-MULTI) have all shown that a complete revascularization reduces the risk of the composite mortality, MI, and future revascularization, driven solely by a reduction in the risk of future revascularization.

2.1. Timing of revascularization of non-IRA

A meta-analysis[31] of 10 randomized trials, including 2285 patients, compared the different revascularization strategies for treating MVD at the time of primary PCI. The available strategies are: (1) complete revascularization during the index procedure; (2) complete revascularization as a staged procedure where the non-IRA is treated before discharge; and (3) complete revascularization as a staged-procedure performed after discharge. Complete revascularization, either during the index procedure or as a staged procedure, or after discharge, was associated with a reduction in risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE); however, this was driven by a reduction in the risk of urgent revascularization. There was no difference in the risk of MACE based on the timing of revascularization of the non-IRA (i.e., during the index procedure, staged procedure during the hospitalization, or after discharge). There was no difference in all-cause mortality and spontaneous re-infarction with any of the four strategies.

2.2. Chronic total occlusion as the non-culprit lesion

The EXPLORE Trial[32] (Evaluating Xience and Left Ventricular Function in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on Occlusions After ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) investigated patients with STEMI who had a concomitant chronic total occlusion (CTO) as the non-IRA. At four months follow-up, there was no difference in mean left ventricular ejection fraction between patients who had PCI to IRA versus patients who had PCI to IRA and CTO PCI (performed as a staged procedure within seven days of primary PCI). However, a subgroup analysis demonstrated improved ejection fraction after four months in patients who had CTO PCI of the left anterior descending artery. Accordingly, these findings do not support routine revascularization of the non-IRA CTO in STEMI patients with MVD.

2.3. Discordance between observational studies and randomized trials

The initial recommendation against PCI of non-IRA was driven from observational data. These were non-randomized studies and demonstrated inconsistent results. Contrary to the observational studies, randomized controlled trials have shown that a complete revascularization approach is associated with better outcomes, driven only by a reduction in the risk of future revascularization. The main explanation nation for this discrepancy is the possible allocation/selection bias in observational studies, which may account for these conflicting results. Most observational studies tended to allocate higher-risk patients (i.e., those with cardiogenic shock or higher Killip class) to complete revascularization, which may explain why the observational studies showed higher mortality with complete revascularization. When these baseline imbalances were accounted for both observational and randomized studies suggested that multi-vessel PCI is beneficial in STEMI patients.[33]

2.4. Updated guideline recommendations

Following publication of these randomized studies, the earlier class III recommendation published in 2013 was updated class IIb. The updated ACC/AHA guideline suggests that complete revascularization can be considered either at the time of primary PCI or as a subsequent staged procedure.[34] The 2017 European Society of Cardiology guidelines provide a class IIA recommendation for complete revascularization STEMI patients with MVD.[35]

2.5. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction (COMPLETE trial)

Recently, the results of the long awaited COMPLETE trial were published.[36] The COMPLETE trial is the first trial to date which has been adequately powered to determine the benefit of a complete revascularization approach on the composite of cardiovascular mortality or MI. The trial randomized 4,041 patients to complete revascularization of non-IRA, mostly angiographic guided, as a staged-procedure (performed from 1–45 days) versus a culprit-only strategy. Most of the patients (about 64%) in the complete revascularization group underwent revascularization for the IRA prior to discharge (median one day from the index procedure). At a median of three years, complete revascularization reduced the risk of the composite of cardiovascular mortality or MI (HR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.60–0.91, P = 000.04) driven by a reduction in the risk of MI (HR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.53–0.86). Complete revascularization also reduced the risk of the composite of cardiovascular mortality, MI or ischemia-driven revascularization (HR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.43–0.61, P < 0.0001). This benefit was observed regardless of the timing of the non-IRA (i.e., performed before or after discharge). Notably, the mean SYNTAX score for the non-IRA was low in this trial (4.6 ± 2.7).

2.6. STEMI and cardiogenic shock

Patients presenting with an MI and cardiogenic shock have a very high mortality rate[37],[38] when treated conservatively with a non-invasive approach. The majority of these patients have MVD causing global ischemia.[39] Stimming from this concept that multi-vessel revascularization may improve global ischemia, observational studies have evaluated the benefit of a complete revascularization approach. In one prospective multicenter observational study in France, 266 patients presenting with STEMI, cardiogenic shock and resuscitated cardiac arrest were enrolled. Complete revascularization was associated with a higher 6-month survival and a reduction in the composite endpoint of recurrent cardiac arrest and shock death when compared with IRA only PCI.[40] Based on the findings of these observational studies, guidelines[41],[42] recommended complete revascularization for patients with cardiogenic shock and STEMI. However, these findings were disputed in the recent CULPRIT-SHOCK Trial[43] which randomized 706 patients with acute MI and cardiogenic shock to either IRA only PCI or complete revascularization. At 30-days, the rate of the composite endpoint of death or new renal-replacement therapy was significantly lower in the IRA only PCI group versus the complete revascularization group (relative risk (RR) = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.71–0.96). In the IRA only PCI group, the rate of death from any etiology was significantly lower compared to the multi-vessel PCI group (RR = 0.84; 95% CI: 0.72–0.98), and a trend towards lower mortality was also observed at 1-year.[44] Based on the findings from the CULPRIT-SHOCK Trial, the updated 2017 European Society of Cardiology STEMI guidelines[45] recommend that primary PCI should be restricted to IRA only in STEMI patients with cardiogenic shock.

3. MVD revascularization in NSTEMI

There is a paucity of randomized trials that have studied complete versus IRA only revascularization in NSTEMI patients with MVD, including an evaluation of whether simultaneous or staged PCI provide a different clinical yield for these individuals. The European Society of Cardiology recommends complete revascularization in NSTEMI patients who have MVD. This recommendation was based on studies that showed a benefit of early intervention requiring complete revascularization when compared to a conservative approach among NSTEMI patient; worse outcomes were observed when incomplete revascularization was the selected strategy.[3]

In the largest study to date of 21,857 patients with NSTEMI and MVD, 53.7% of these patients underwent complete revascularization during PCI for NSTEMI, while the rest had PCI to IRA only. At a median follow-up of 4.6 years, the rate of all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the complete revascularization group versus IRA only revascularization (22.5% vs. 25.9% respectively; P = 0.0005). After multivariate adjustment, complete revascularization was associated with lower mortality (HR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.85–0.97).[46]

4. Summary and future directions

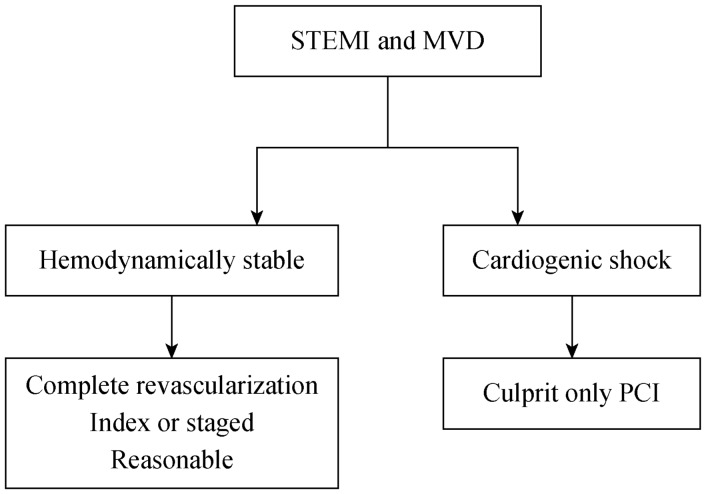

Over the last decade, the revascularization approach for STEMI patients with MVD has evolved. The initial paradigm was to perform an IRA only approach in stable patients and a complete revascularization approach in patients with cardiogenic shock; which was based predominately on observational studies. With emergence of the randomized data, we have learned that a complete revascularization approach for non-IRA lesions (excluding CTO) is associated with improved outcomes. The recently published COMPLETE trial showed that a complete revascularization approach reduces the risk of cardiovascular mortality or MI driven by a reduction in MI. Based on the findings of this trial, as well as the other moderate sized RCTs will probably provide society guidelines with stronger evidence to support the recommendation for a complete revascularization approach. However, it is important to highlight that patients enrolled in clinical trials are oftentimes less sicker than ones encountered in clinical practice, as highlighted by the fact that the SYNTAX score for the non-IRA in the COMPLETE trial was low. Thus, it remains unknown whether the same benefit would be observed in patients with more complex disease. We also learned that the non-IRA lesion's revascularization timing does not have an influence on the improved outcomes with a complete revascularization approach. In contrast, patients with cardiogenic shock would benefit from an IRA only revascularization approach (Figure 1). Data regarding complete revascularization for MVD and NSTEMI are solely driven from observational studies, which have shown that a complete revascularization approach may be clinically beneficial. However, as we learned in the case of STEMI studies, data from observational studies are prone to selection and allocation biases, and thus, future randomized trials that are adequately powered for hard outcomes (e.g., mortality and MI) should address this knowledge gap.

Figure 1. Approach for revascularization strategies for patients with STEMI and MVD.

MVD: multi-vessel disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgments

All authors report no financial disclosures relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Desperak P, Hawranek M, Gasior P, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with multivessel coronary artery disease presenting non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Cardiol J. 2019;26:157–168. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parodi G, Memisha G, Valenti R, et al. Five year outcome after primary coronary intervention for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: results from a single centre experience. Heart. 2005;91:1541–1544. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.054692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Park HS, Ryu HM, et al. Impact of multivessel coronary disease with chronic total occlusion on one-year mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2012;42:95–99. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavender MA, Milford-Beland S, Roe MT, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and in-hospital outcomes of non-infarct artery intervention during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toma M, Buller CE, Westerhout CM, et al. Non-culprit coronary artery percutaneous coronary intervention during acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the APEX-AMI trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1701–1707. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, et al. Impact of multivessel coronary artery disease and noninfarct-related artery revascularization on outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (from the EUROTRANSFER Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer T, Zeymer U, Hochadel M, et al. Prima-vista multi-vessel percutaneous coronary intervention in haemodynamically stable patients with acute coronary syndromes: analysis of over 4.400 patients in the EHS-PCI registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaguszewski M, Radovanovic D, Nallamothu BK, et al. Multivessel versus culprit vessel percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: is more worse? EuroIntervention. 2013;9:909–915. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I8A153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos AR, Picarra BC, Celeiro M, et al. Multivessel approach in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: impact on in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Rev Port Cardiol. 2014;33:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeger R, Jaguszewski M, Nallamothu BN, et al. Acute multivessel revascularization improves 1-year outcome in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a nationwide study cohort from the AMIS Plus registry. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manari A, Varani E, Guastaroba P, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease treated with culprit-only, immediate, or staged multivessel percutaneous revascularization strategies: Insights from the REAL registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84:912–922. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corpus RA, House JA, Marso SP, et al. Multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel disease and acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;148:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khattab AA, Abdel-Wahab M, Rother C, et al. Multi-vessel stenting during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. A single-center experience. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:32–38. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qarawani D, Nahir M, Abboud M, et al. Culprit only versus complete coronary revascularization during primary PCI. Int J Cardiol. 2008;123:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varani E, Balducelli M, Aquilina M, et al. Single or multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:927–933. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohamad T, Bernal JM, Kondur A, et al. Coronary revascularization strategy for ST elevation myocardial infarction with multivessel disease: experience and results at 1-year follow-up. Am J Ther. 2011;18:92–100. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181b809ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MC, Jeong MH, Park KH, et al. Three-year clinical outcomes of staged, ad hoc and culprit-only percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:505–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roe MT, Cura FA, Joski PS, et al. Initial experience with multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention during mechanical reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:170–173. a176. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan EL, Samadashvili Z, Walford G, et al. Culprit vessel percutaneous coronary intervention versus multivessel and staged percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with multivessel disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal MB, Ilsley C, Kabir T, et al. Culprit vessel versus multivessel intervention at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease: real-world analysis of 3984 patients in London. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:936–943. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates ER, Tamis-Holland JE, Bittl JA, et al. PCI strategies in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1066–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1115–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gershlick A. Acute Coronary Syndromes, Cardiogenic Shock and Hemodynamic Support; Presented at: TCT Scientific Symposium; Sept. 21–25, 2018; San Diego. Https://www.healio.com/cardiac-vascular-intervention/percutaneous-coronary-intervention/news/online/%7Bd6ef3bc8-b1d0-45a3-95ad-cb88c8e306a0%7D/long-term-mace-risk-reduced-with-complete-revascularization-cvlprit. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fearon WF. Percutaneous coronary intervention should be guided by fractional flow reserve measurement. Circulation. 2014;129:1860–1870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ntalianis A, Sels JW, Davidavicius G, et al. Fractional flow reserve for the assessment of nonculprit coronary artery stenoses in patients with acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engstrom T, Kelbaek H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:665–671. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smits PC, Abdel-Wahab M, Neumann FJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided multivessel angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1234–1244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elgendy IY, Mahmoud AN, Kumbhani DJ, et al. Complete or culprit-only revascularization for patients with multivessel coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriques JP, Hoebers LP, Ramunddal T, et al. Percutaneous intervention for concurrent chronic total occlusions in patients with STEMI: The EXPLORE Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1622–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad Y, Cook C, Shun-Shin M, et al. Resolving the paradox of randomised controlled trials and observational studies comparing multi-vessel angioplasty and culprit only angioplasty at the time of STEMI. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial Infarction: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87:1001–1019. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907775. Published Online First: Sep. 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Killip T, 3rd, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1967;20:457–464. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(67)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, et al. Cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Incidence and mortality from a community-wide perspective, 1975 to 1988. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1117–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindholm MG, Kober L, Boesgaard S, et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction; prognostic impact of early and late shock development. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:258–265. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mylotte D, Morice MC, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, and cardiogenic shock: the role of primary multivessel revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–e651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2419–2432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al. One-Year Outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1699–1710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibanez B, Halvorsen S, Roffi M, et al. Integrating the results of the CULPRIT-SHOCK trial in the 2017 ESC ST-elevation myocardial infarction guidelines: viewpoint of the task force. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:4239–4242. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rathod KS, Koganti S, Jain AK, et al. Complete versus culprit-only lesion intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1989–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]