Abstract

We review empirical research on (social) psychology of morality to identify which issues and relations are well documented by existing data and which areas of inquiry are in need of further empirical evidence. An electronic literature search yielded a total of 1,278 relevant research articles published from 1940 through 2017. These were subjected to expert content analysis and standardized bibliometric analysis to classify research questions and relate these to (trends in) empirical approaches that characterize research on morality. We categorize the research questions addressed in this literature into five different themes and consider how empirical approaches within each of these themes have addressed psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior. We conclude that some key features of theoretical questions relating to human morality are not systematically captured in empirical research and are in need of further investigation.

Keywords: moral reasoning, moral behavior, moral judgment, moral self-views, moral emotions

This review aims to examine the “psychology of morality” by considering the research questions and empirical approaches of 1,278 empirical studies published from 1940 through 2017. We subjected these studies to expert content analysis and standardized bibliometric analysis to characterize relevant trends in this body of research. We first identify key features that characterize theoretical approaches to human morality, extract five distinct classes of research questions from the studies conducted, and visualize how these aim to address the psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior. We then compare this theoretical analysis with the empirical approaches and research paradigms that are typically used to address questions within each of these themes. We identify emerging trends and seminal publications, specify conclusions that can be drawn from studies conducted within each research theme, and outline areas in need of further investigation.

Morality indicates what is the “right” and “wrong” way to behave, for instance, that one should be fair and not unfair to others (Haidt & Kesebir, 2010). This is considered of interest to explain the social behavior of individuals living together in groups (Gert, 1988). Results from animal studies (e.g., de Waal, 1996) or insights into universal justice principles (e.g., Greenberg & Cropanzano, 2001) do not necessarily help us to address moral behavior in modern societies. This also requires the reconciliation of people who endorse different political orientations (Haidt & Graham, 2007) or adhere to different religions (Harvey & Callan, 2014). The observation that “good people can do bad things” further suggests that we should look beyond the causes of individual deviance or delinquency to understand moral behavior. In our analysis, we consider key explanatory principles emerging from prominent theoretical approaches to capture important features characterizing human morality (Tomasello & Vaish, 2013). These relate to (a) the social anchoring of right and wrong, (b) conceptions of the moral self, and (c) the interplay between thoughts and experiences. We argue that these three key principles explain the interest of so many researchers in the topic of morality and examine whether and how these are addressed in empirical research available to date.

Through an electronic literature search (using Web of Science [WoS]) and manual selection of relevant entries, we collected empirical publications that contained an empirical measure and/or manipulation that was characterized by the authors as relevant to “morality.” With this procedure, we found 1,278 papers published from 1940 through 2017 that report research addressing morality. Notwithstanding the enormous research interest visible in empirical publications on morality, a comprehensive overview of this literature is lacking. In fact, the review paper on morality that was most frequently cited in our set was published more than 35 years ago (Blasi, 1980). As it stands, separate strands of research seem to be driven by different questions and empirical approaches that do not connect to a common approach or research agenda. This makes it difficult to draw summary conclusions, to integrate different sets of findings, or to chart important avenues for future research.

To organize and understand how results from empirical studies relate to each other, we identify the relations that are implicitly seen to connect different research questions. The rationales provided to study specific issues commonly refer to the psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior and thus are seen to capture “the psychology of morality.” By content-analyzing the study reports provided, we classify the studies included in this review into five groups of thematic research questions and characterize the empirical approaches typically used in studies addressing each of these themes. With the help of bibliometric techniques, we then quantify emerging trends and consider how different clusters of study approaches relate to questions in each of the research themes examined. This allows us to clarify the theoretical conclusions that can be drawn from empirical work so far and to identify less examined issues in need of further study.

Morality and Social Order

Moral principles indicate what is a “good,” “virtuous,” “just,” “right,” or “ethical” way for humans to behave (Haidt, 2012; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Turiel, 2006). Moral guidelines (“do no harm”) can induce individuals to display behavior that has no obvious instrumental use or no direct value for them, for instance, when they show empathy, fairness, or altruism toward others. Moral rules—and sanctions for those who transgress them—are used by individuals living together in social communities, for instance, to make them refrain from selfish behavior and to prevent them from lying, cheating, or stealing from others (Ellemers, 2017; Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012; Ellemers & Van der Toorn, 2015).

The role of morality in the maintenance of social order is recognized by scholars from different disciplines. Biologists and evolutionary scientists have documented examples of selfless and empathic behaviors observed in communities of animals living together, considering these as relevant origins of human morality (e.g., de Waal, 1996). The main focus of this work is on displays of fairness, empathy, or altruism in face-to-face groups, where individuals all know and depend on each other. In the analysis provided by Tomasello and Vaish (2013), this would be considered the “first tier” of morality, where individuals can observe and reciprocate the treatment they receive from others to elicit and reward cooperative and empathic behaviors that help to protect individual and group survival.

Philosophers, legal scholars, and political scientists have addressed more abstract moral principles that can be used to regulate and govern the interactions of individuals in larger and more complex societies (e.g., Haidt, 2012; Mill 1861/1962). Here, the nature of cooperative or empathic behavior is much more symbolic as it depends less on direct exchanges between specific individuals, but taps into more abstract and ambiguous concepts such as “the greater good.” Scholarly efforts in this area have considered how specific behaviors might (not) be in line with different moral principles and which guidelines and procedures might institutionalize social order according to such principles (e.g., Churchland, 2011; Morris, 1997). These approaches tap into what Tomasello and Vaish (2013) consider the “second tier” of morality, which emphasizes the social signaling functions of moral behavior and distinguishes human from animal morality (see also Ellemers, 2018). At this level, behavioral guidelines that have lost their immediate survival value in modern societies (such as specific dress codes or dietary restrictions) may nevertheless come to be seen as prescribing essential behavior that is morally “right.” Specific behaviors can acquire this symbolic moral value to the extent that they define how individuals typically mark their religious identity, communicate respect for authority, or secure group belonging for those adhering to them (Tomasello & Vaish, 2013). Moral judgments that function to maintain social order in this way rely on complex explanations and require verbal exchanges to communicate the moral overtones of behavioral guidelines. Language-driven interpretations and attributions are needed to capture symbolic meanings and inferred intentions that are not self-evident in behavioral displays or outwardly visible indicators of emotions (Ellemers, 2018; Kagan, 2018).

The interest of psychologists in moral behavior as a factor in maintaining social order has long been driven by developmental questions (how do children acquire the ability to do this, for example, Kohlberg, 1969) and clinical implications (what are origins of social deviance and delinquency, for example, Rest, 1986). Jonathan Haidt’s (2001) publication, on the role of quick intuition versus deliberate reflection in distinguishing between right and wrong, marked a turning point in the interest of psychologists in these issues. The consideration of specific psychological mechanisms involved in moral reasoning prompted many psychological researchers to engage with this area of inquiry. This development also facilitated the connection of psychological theory to neurobiological mechanisms and inspired attempts to empirically examine underlying processes at this level—for instance, by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures to monitor the brain activity of individuals confronted with moral dilemmas (Greene, 2013; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001).

Below, we will consider influential approaches that have advanced the understanding of human morality in social psychology, organizing them according to their main explanatory focus. These characterize the “second tier” (Tomasello & Vaish, 2013) implications of morality that go beyond more basic displays of empathy and altruism observed in animal studies that form the root of biological and evolutionary explanations. From the theoretical perspectives currently available, we extract three key principles that capture the essence of human morality.

Social Anchoring of Right and Wrong

The first principle refers to the social implications of judgments about right and wrong. This has been emphasized as a defining characteristic of morality in different theoretical perspectives. For instance, Skitka (2010) and colleagues have convincingly argued that beliefs about what is morally right or wrong are unlike other attitudes or convictions (Mullen & Skitka, 2006; Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005; Skitka & Mullen, 2002). Instead, moral convictions are seen as compelling mandates, indicating what everyone “ought” to or “should” do. This has important social implications, as people also expect others to follow these behavioral guidelines. They are emotionally affected and distressed when this turns out not to be the case, find it difficult to tolerate or resolve such differences, and may even resort to violence against those who challenge their views (Skitka & Mullen, 2002).

This socially defined nature of moral guidelines is explicitly acknowledged in several theoretical perspectives on moral behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior (e.g., Ajzen, 1991) offers a framework that clearly specifies how behavioral intentions are determined in an interplay of individual dispositions and social norms held by self-relevant others (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1974; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1974). For instance, research based on this perspective has been used to demonstrate that the adoption of moral behaviors, such as expressing care for the environment, can be enhanced when relevant others think this is important (Kaiser & Scheuthle, 2003).

In a similar vein, Haidt (2001) argued that judgments of what are morally good versus bad behaviors or character traits are specified in relation to culturally defined virtues. This allows shared ideas about right and wrong to vary, depending on the cultural, religious, or political context in which this is defined (Giner-Sorolla, 2012; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Rai & Fiske, 2011). Haidt (2001) accordingly specifies that moral intuitions are developed through implicit learning of peer group norms and cultural socialization. This position is supported by empirical evidence showing how moral behavior plays out in groups (Graham, 2013; Graham & Haidt, 2010; Janoff-Bulman & Carnes, 2013). This work documents the different principles that (groups of) people use in their moral reasoning (Haidt, 2012). By connecting judgments about right and wrong to people’s group affiliations and social identities, this perspective clarifies why different religious, political, or social groups sometimes disagree on what is moral and find it difficult to understand the other position (Greene, 2013; Haidt & Graham, 2007).

We argue that all these notions point to the socially defined and identity-affirming properties of moral guidelines and moral behaviors. Conceptions of right and wrong reflect the values that people share with important others and are anchored in the social groups to which they (hope to) belong (Ellemers, 2017; Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012; Ellemers & Van der Toorn, 2015; Leach, Bilali, & Pagliaro, 2015). This also implies that there is no inherent moral value in specific actions or overt displays, for instance, of empathy or helping. Instead, the same behaviors can acquire different moral meanings, depending on the social context in which they are displayed and the relations between actors and targets involved in this context (Blasi, 1980; Gray, Young, & Waytz, 2012; Kagan, 2018; Reeder & Spores, 1983).

Thus, a first question to be answered when reviewing the empirical literature, therefore, is whether and how the socially shared and identity relevant nature of moral guidelines—central to key theoretical approaches—is adressed in the studies conducted to examine human morality.

Conceptions of the Moral Self

A second principle that is needed to understand human morality—and expands evolutionary and biological approaches—is rooted in the explicit self-awareness and autobiographical narratives that characterize human self-consciousness, and moral self-views in particular (Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt, & Skitka, 2014).

Because of the far-reaching implications of moral failures, people are highly motivated to protect their self-views of being a moral person (Pagliaro, Ellemers, Barreto, & Di Cesare, 2016; Van Nunspeet, Derks, Ellemers, & Nieuwenhuis, 2015). They try to escape self-condemnation, even when they fail to live up to their own moral standards. Different strategies have been identified that allow individuals to disengage their self-views from morally questionable actions (Bandura, 1999; Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996; Mazar, Amir, & Ariely, 2008). The impact of moral lapses or moral transgressions on one’s self-image can be averted by redefining one’s behavior, averting responsibility for what happened, disregarding the impact on others, or excluding others from the right to moral treatment, to name just a few possibilities.

A key point to note here is that such attempts to protect moral self-views are not only driven by the external image people wish to portray toward others. Importantly, the conviction that one qualifies as a moral person also matters for internalized conceptions of the moral self (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Reed & Aquino, 2003). This can prompt people, for instance, to forget moral rules they did not adhere to (Shu & Gino, 2012), to fail to recall their moral transgressions (Mulder & Aquino, 2013; Tenbrunsel, Diekmann, Wade-Benzoni, & Bazerman, 2010), or to disregard others whose behavior seems morally superior (Jordan & Monin, 2008).

As a result, the strong desire to think of oneself as a moral person not only enhances people’s efforts to display moral behavior (Ellemers, 2018; Van Nunspeet, Ellemers, & Derks, 2015). Instead, sadly, it can also prompt individuals to engage in symbolic acts to distance themselves from moral transgressions (Zhong & Liljenquist, 2006) or even makes them relax their behavioral standards once they have demonstrated their moral intentions (Monin & Miller, 2001). Thus, tendencies for self-reflection, self-consistency, and self-justification are both affected by and guide moral behavior, prompting people to adjust their moral reasoning as well as their judgments of others and to endorse moral arguments and explanations that help justify their own past behavior and affirm their worldviews (Haidt, 2001).

A second important question to consider when reviewing the empirical literature on morality, thus, is whether and how studies take into account these self-reflective mechanisms in the development of people’s moral self-views. From a theoretical perspective, it is therefore relevant to examine antecedents and correlates of tendencies to engage in self-defensive and self-justifying responses. From an empirical perspective, it also implies that it is important to consider the possibility that people’s self-reported dispositions and stated intentions may not accurately indicate or predict the moral behavior they display.

The Interplay Between Thoughts and Experiences

A third principle that connects different theoretical perspectives on human morality is the realization that this involves deliberate thoughts and ideals about right and wrong, as well as behavioral realities and emotional experiences people have, for instance, when they consider that important moral guidelines are transgressed by themselves or by others. Traditionally, theoretical approaches in moral psychology were based on the philosophical reasoning that is also reflected in legal and political scholarship on morality. Here, the focus is on general moral principles, abstract ideals, and deliberate decisions that are derived from the consideration of formal rules and their implications (Kohlberg, 1971; Turiel, 2006). Over the years, this perspective has begun to shift, starting with the observation made by Blasi (1980, p. 1) that

Few would disagree that morality ultimately lies in action and that the study of moral development should use action as the final criterion. But also few would limit the moral phenomenon to objectively observable behavior. Moral action is seen, implicitly or explicitly, as complex, imbedded in a variety of feelings, questions, doubts, judgments, and decisions . . . . From this perspective, the study of the relations between moral cognition and moral action is of primary importance.

This perspective became more influential as a result of Haidt’s (2001) introduction of “moral intuition” as a relevant construct. Questions about what comes first, reasoning or intuition, have yielded evidence showing that both are possible (e.g., Feinberg, Willer, Antonenko, & John, 2012; Pizarro, Uhlmann, & Bloom, 2003; Saltzstein & Kasachkoff, 2004). That is, reasoning can inform and shape moral intuition (the classic philosophical notion), but intuitive behaviors can also be justified with post hoc reasoning (Haidt’s position). The important conclusion from this debate thus seems to be that it is the interplay between deliberate thinking and intuitive knowing that shapes moral guidelines (Haidt, 2001, 2003, 2004). This points to the importance of behavioral realities and emotional experiences to understand how people reflect on general principles and moral ideals.

A first way in which this has been addressed resonates with the evolutionary survival value of moral guidelines to help avoid illness and contamination as sources of physical harm. In this context, it has been argued and shown that nonverbal displays of disgust and physical distancing can emerge as unthinking embodied experiences to morally aversive situations that may subsequently invite individuals to reason why similar situations should be avoided in the future (Schnall, Haidt, Clore, & Jordan, 2008; Tapp & Occhipinti, 2016). The social origins of moral guidelines are acknowledged in approaches explaining the role of distress and empathy as implicit cues that can prompt individuals to decide which others are worthy of prosocial behavior (Eisenberg, 2000). In a similar vein, the experience of moral anger and outrage at others who violate important guidelines is seen as indicating which guidelines are morally “sacred” (Tetlock, 2003). Experiences of disgust, empathy, and outrage all indicate relatively basic affective states that are marked with nonverbal displays and have direct implications for subsequent actions (Ekman, 1989; Ekman, 1992).

In addition, theoretical developments in moral psychology have identified the experience of guilt and shame as characteristic “moral” emotions. Compared with “primary” affective responses, these “secondary” emotions are used to indicate more complex, self-conscious states that are not immediately visible in nonverbal displays (Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007). These moral emotions are seen to distinguish humans from most animals. Indeed, affording to others the perceived ability to experience such emotions communicates the degree to which we consider them to be human and worthy of moral treatment (Haslam & Loughnan, 2014). The nature of guilt and shame as “self-condemning” moral emotions indicates their function to inform self-views and guide behavioral adaptations rather than communicating one’s state to others.

At the same time, it has been noted that feelings of guilt and shame can be so overwhelming that they raise self-defensive responses that stand in the way of behavioral improvement (Giner-Sorolla, 2012). This can occur at the individual level as well as the group level, where the experience of “collective guilt” has been found to prevent intergroup reconciliation attempts (Branscombe & Doosje, 2004). Accordingly, it has been noted that the relations between the experience of guilt and shame as moral emotions and their behavioral implications depend very much on further appraisals relating to the likelihood of social rejection and self-improvement that guide self-forgiveness (Leach, 2017).

Regardless of which emotions they focus on, these theoretical perspectives all emphasize that moral concerns and moral decisions arise from situational realities, characterized by people’s experiences and the (moral) emotions these evoke. A third question emerging from theoretical accounts aiming to understand human morality, therefore, is whether and how the interplay between the thoughts people have about moral ideals (captured in principles, judgments, reasoning), on one hand, and the realities they experience (embodied behaviors, emotions), on the other, is explicitly addressed in empirical studies.

Empirical Approaches

Now that we have identified that socially shared, self-reflective, and experiential mechanisms represent three key principles that are seen as essential for the understanding of human morality in theory, it is possible to explore how these are reflected in the empirical work available. An initial answer to this question can be found by considering which types of research paradigms and classes of measures are frequently used in studies on morality. Do study designs typically take into account the way different social norms can shape individual moral behavior? Do instruments that are developed to assess people’s morality incorporate the notion that explicit self-reports do not necessarily capture their actual moral responses? And do responses that are assessed allow researchers to connect moral thoughts people have with their actual experiences?

We examined this by reviewing the empirical literature. Through an electronic literature search, we collected empirical studies reporting on manipulations and/or empirical measures that authors of these studies identified as being relevant to “morality.” In a first wave of data collection (see the “Method” section for further details), we extracted 419 empirical studies on morality that were published from 2000 through 2013. These were manually processed and content-coded to determine for each publication the research question that was asked, the research design that was employed to examine this, and the measures that were used (for details of how this was done, see Ellemers, Van der Toorn, & Paunov, 2017). We distinguished between correlational and experimental designs and assessed which manipulations were used to compare different responses (see Supplementary Table A). We also listed and classified “named” scales and measures that were employed in these studies (see Table 1) and additionally indicated which types of responses were captured, in moral judgments provided, emotional and behavioral indicators, or with standardized scales (see Supplementary Table B).

Table 1.

Four Types of Scales Used to Examine Morality in 91 Publications, With N Indicating the Number of Publications Using a Scale Type, Indicated in Order of Most Frequently Used (First Scale Mentioned) to Least Frequently Used (Last Scale Mentioned).

| Hypothetical moral dilemmas (N = 27) | Self-reported traits/behaviors of self/other (N = 32) | Endorsement of abstract moral rules (N = 31) | Position on specific moral issues (N = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defining Issues Test (DIT) (Rest et al., 1974) Prosocial Moral Reasoning Measure (PROM) (Carlo, Eisenberg & Knight, 1992) Accounting Specific Defining Issues Test (ADIT) (Thorne, 2000) Revised Moral Authority Scale (MAS-R) (White, 1997) Moral/Conventional Distinction Task (Blair, 1995; Blair et al., 2001) Moral Emotions Task (Kédia et al., 2008) Moral Judgment Test (MJT) (Lind, 1998) |

Moral Identity Scale (Aquino & Reed, 2002) HEXACO-PI (Lee & Ashton, 2004) Implicit Association Task (IAT) (Perugini & Leone, 2009) Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) (Frederick, 2005) Index of Moral Behaviors (Chadwick, Bromgard, Bromgard, & Trafimow, 2006) Josephson Institute Report Card on the Ethics of American Youth (Josephson Institute, 2012) Moral Entrepreneurial Personality (MEP) (Yurtsever, 2003) Moral Functioning Model (Rest, 1984) Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (Fitts, 1956) Washington Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development (Loevinger & Wessler, 1970) Moral Exemplarity (Frimer, Walker, Lee, Riches, & Dunlop, 2012) |

Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009) Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) (Schwartz, 1992) Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) (Forsyth, 1980) Integrity Scale (Schlenker, 2008) Moral Motives Scale (MMS) (Janoff-Bulman, Sheikh, & Baldacci 2008) Identification with all Humanities Scale (McFarland et al., 2012) Moral Character (Dweck et al., 1995) Value Survey Module (Hofstede, 1994) Community Autonomy Divinity Scale (CADS) (Guerra & Giner-Sorolla, 2010) Moral Foundations Dictionary (Graham et al., 2011) |

Moral Disengagement Scale (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996) Sensitivity to Injustice (Schmitt et al., 2005) Sociomoral Reflection Measure–Short Form (SRM-SF) (Gibbs et al., 1992) Beliefs About Morality (BAM) (Bergner & Ramon, 2013) Dubious Behaviors (Jones, 1990) Morally Debatable Behaviors Scale (MDBS) (Katz, Santman, & Lonero, 1994) Moral Disengagement Tool (Renati et al., 2012) Self-reported Inappropriate Negotiation Strategies Scale (SINS scale) (Robinson et al., 2000) TRIM-18R (McCullough et al., 2006) |

Note. A single publication can contain multiple scales.

Are Social Influences Taken Into Account?

An overview of the research designs that were coded in this way (see Supplementary Table A, final column) first reveals that a substantial proportion of these studies (185 of 419 studies examined; 44%) used correlational designs to examine, for instance, which traits people associate with particular targets or how self-reported beliefs, convictions, principles, or norms relate to self-stated intentions. Of the studies using an experimental design, a substantial number (91 studies; about 22%) examined the impact of some situational prime intended to activate specific goals, rules, or experiences. Furthermore, a substantial number of studies examined the impact of manipulating specific target characteristics (51 studies; 12%) or moral concerns (51 studies; 12%). However, experimental studies examining the impact of specific social norms (31 studies; 7%) or a group-based participant identity were relatively rare (four studies; less than 1%). This suggests that the socially shared nature of moral guidelines is not systematically addressed in this body of research.

Do Standard Instruments Rely on Self-Reports?

The types of responses typically examined in these studies can be captured by looking in more detail at the nature of the scales, tests, tasks, and questionnaires that were used. Our manual content analysis yielded 38 different scales, tests, tasks, and questionnaires that were used in 91 of the 419 studies examined (see Table 1). We clustered these according to their nature and intent, which yielded four distinct categories. We found seven different measures (used in 27 studies; 30%) that rely on hypothetical moral dilemmas, where people have to weigh different moral principles against each other (e.g., stealing from one person to help another person), and indicate what should be done in these situations. We found 11 additional measures (used in 12 studies; 13%) consisting of lists of traits or behaviors (e.g., honesty, helpfulness) that can be used to indicate the general character/personality type of the self or a known other (friend, family member). Here, we included measures such as the HEXACO Personality Inventory (HEXACO-PI; Lee & Ashton, 2004) and the moral identity scale (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Third, we found 11 different measures (used in 31 studies; 34%) that assess the endorsement of abstract moral rules (e.g., “do no harm”). A representative example is the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham et al., 2011), which distinguishes between statements indicating concern for “individualizing” principles (harm/care, fairness) and “binding” principles (loyalty, authority, purity). Fourth, we found nine different measures (used in 20 studies; 22%) aiming to capture people’s position on specific moral issues (e.g., “it is important to tell the truth”; “it is ok for employees to take home a few office supplies”). We also included in this category different lists of behaviors (for instance, the Morally Debatable Behaviors Scale [MDBS]; Katz, Santman, & Lonero, 1994) that focus on the endorsement of behaviors considered relevant to morality (e.g., corruption, violence, discrimination, or misrepresentation).

Importantly, all four clusters of measures we found to rely on self-reported preferences and stated character traits or intentions, describing overall tendencies and general behavioral guidelines. However, it is less evident that such measures can be used to understand how people will actually behave in real-life situations, where they may have to choose which of different competing guidelines to apply or where it is unclear how the general principles they endorse translate to a specific act or decision in that context.

Are “Thoughts” Connected to “Experiences?”

Our manual coding of the different dependent measures that were used (see Supplementary Table B, final column) reveals that the majority of measures aimed to capture either general moral principles that people endorse (72 of 445 measures coded; 16%) or their moral evaluations of specific individuals, groups, or companies (72 measures; 16%). In addition, a substantial proportion of studies examined people’s positions on specific issues, such as abortion, gossiping, or specific political convictions (61 measures; 14%). Substantial numbers of measures assessed the perceived implications of one’s moral principles (48 measures; 11%) or the willingness to be cooperative or truthful in hypothetical situations (44 measures; 10%). Notably, a relatively small proportion of measures actually tried to capture cooperative or cheating behavior in experimental or real-life situations (51 measures; 12%). Similarly, empathy with others and moral emotions such as guilt, shame, and disgust were assessed in 15% (67) of the measures that were coded. Thus, the majority of measures used focuses on “thoughts” relating to morality, as these capture abstract principles, overall judgments, or hypothetical intentions, while much less attention has been devoted to examining behavioral displays or emotions characterizing the actual “experiences” people have in relation to these “thoughts.”

Thus, this initial examination of empirical evidence available in studies on morality published from 2000 through 2013 suggests that the three key theoretical principles we have extracted from relevant theoretical perspectives on morality are not systematically reflected in the research that has been carried out. Instead, it seems that “moral tendencies” are typically defined independently of the social context, specific norms, or the identity of others who may be affected by the (im)moral behavior. Furthermore, general and self-reported tendencies or preferences are often taken at face value without testing them against actual behavioral displays or emotional experiences. Finally, empirical studies have prioritized the examination of all kinds of “thoughts” relating to morality over attempts to connect these to actual moral “experiences.” Thus, this initial examination of the literature seems to reveal a mismatch between the empirical approach that is typically taken and leading theoretical perspectives—that emphasize the socially shared nature of moral guidelines, the self-justifying nature of moral reasoning, and the importance of emotional experiences.

As others have noted before us (e.g., Abend, 2013), this initial assessment of studies carried out suggests that the empirical breadth of past morality research is constrained in that some approaches appear to be favored at the expense of others. Studies often rely on highly artificial paradigms or scenarios (Chadwick, Bromgard, Bromgard, & Trafimow, 2006; Eriksson, Strimling, Andersson, & Lindholm, 2017). They examine hypothetical reasoning or focus on a few specific decisions or actions that may rarely present themselves in everyday life, such as deciding about the course of a runaway train (Bauman, McGraw, Bartels, & Warren, 2014; Graham, 2014) or eating one’s dog (Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993; Mooijman & Van Dijk, 2015). This does not capture the wide variety of contexts in which moral choices have to be made (for instance, whether or not to sell a subprime mortgage to achieve individual performance targets), and it is not evident whether and how this limits the conclusions that can be drawn from such work (for similar critiques, see Crone & Laham, 2017; Graham, 2014; Hofmann et al., 2014; Lovett, Jordan, & Wiltermuth, 2015).

Understanding Moral Behavior

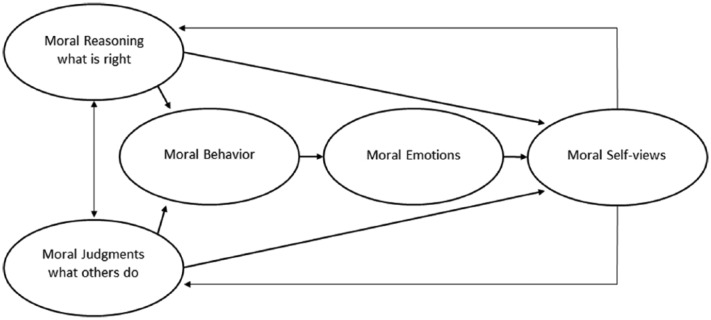

Our conclusion so far is that researchers in social psychology have displayed a considerable interest in examining topics relating to morality. However, it is not self-evident how the multitude of research topics and issues that are addressed in this literature can be organized. This is why we set out to organize the available research in this area into a limited set of meaningful categories by content-analyzing the publications we found to identify studies examining similar research questions. In the “Method” section, we provide a detailed explanation of the procedure and criteria we used to develop our coding scheme and to classify studies as relating to one of five research themes we extracted in this way. We now consider the nature of the research questions addressed within each of these themes and the rationales typically provided to study them, to specify how different research questions that are examined are seen to relate to each other. We visualize these hypothesized relations in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The psychology of morality: connections between five research themes.

Researchers in this literature commonly cite the ambition to predict, explain, and influence Moral Behavior as their focal guideline for having an interest in examining some aspect of morality (see also Ellemers, 2017). We therefore place research questions relating to this theme at the center of Figure 1. Questions about behavioral displays that convey the moral tendencies of individuals or groups fall under this research theme. These include research questions that address implicit indicators of moral preferences or cooperative choices, as well as more deliberate displays of helping, cheating, or standing up for one’s principles.

Many researchers claim to address the likely antecedents of such moral behaviors that are located in the individual as well as in the (social) environment. Here, we include research questions relating to Moral Reasoning, which can reflect the application of abstract moral principles as well as specific life experiences or religious and political identities that people use to locate themselves in the world (e.g., Cushman, 2013). This work addresses moral standards people can adhere to, for instance, in the decision guidelines they adopt or in the way they respond to moral dilemmas or evaluate specific scenarios.

We classify research questions as referring to Moral Judgments when these address the dispositions and behaviors of other individuals, groups, or companies in terms of their morality. These are considered as relevant indicators of the reasons why and conditions under which people are likely to display moral behavior. Research questions addressed under this theme consider the characteristics and actions of other individuals and groups as examples of behavior to be followed or avoided or as a source of information to extract social norms and guidelines for one’s own behavior (e.g., Weiner, Osborne, & Rudolph, 2011).

We distinguish between these two clusters to be able to separate questions addressing the process of moral reasoning (to infer relevant decision rules) from questions relating to the outcome in the form of moral judgments (of the actions and character of others). However, the connecting arrow in Figure 1 indicates that these two types of research questions are often discussed in relation to each other, in line with Haidt’s (2001) reasoning that these are interrelated mechanisms and that moral decision rules can prescribe how certain individuals should be judged, just as person judgments can determine which decision rules are relevant in interacting with them.

We proceed by considering research questions that relate to the psychological implications of moral behavior. The immediate affective implications of one’s behavior, and how this reveals one’s moral reasoning as well as one’s judgments of others, are addressed in questions relating to Moral Emotions (Sheikh, 2014). These are the emotional responses that are seen to characterize moral situations and are commonly used to diagnose the moral implications of different events. Questions we classified under this research theme typically address feelings of guilt and shame that people experience with regard to their own behavior, or outrage and disgust in response to the moral transgressions of others.

Finally, we consider research questions addressing self-reflective and self-justifying tendencies associated with moral behavior. Studies aiming to investigate the moral virtue people afford to themselves and the groups they belong to, and the mechanisms they use for moral self-protection, are relevant for Moral Self-Views. Under this research theme, we subsume research questions that address the mechanisms people use to maintain self-consistency and think of themselves as moral persons, even when they realize that their behavior is not in line with their moral principles (see also Bandura, 1999).

Even though research questions often consider moral emotions and moral self-views as outcomes of moral behaviors and theorize about the factors preceding these behaviors, this does not imply that emotions and self-views are seen as the final end-states in this process. Instead, many publications refer to these mechanisms of interest as being iterative and assume that prior behaviors, emotions, and self-views also define the feedback cycles that help shape and develop subsequent reasoning and judgments of (self-relevant) others, which are important for future behavior. The feedback arrows in Figure 1 indicate this.

Our main goal in specifying how different types of research questions can be organized according to their thematic focus in this way is to offer a structure that can help monitor and compare the empirical approaches that are typically used to advance existing insights into different areas of interest. The relations depicted in Figure 1 represent the reasoning commonly provided to motivate the interest in different types of research questions. The location of the different themes in this figure clarifies how these are commonly seen to connect to each other and visualizes the (sometimes implicit) assumptions made about the way findings from different studies might be combined and should lead to cumulative insights. In the sections that follow, we will examine the empirical approaches used to address each of these clusters of research questions to specify the ways in which results from different types of studies actually complement each other and to identify remaining gaps in the empirical literature.

A Functionalist Perspective

An important feature of our approach is that we do not delineate research questions in terms of the specific moral concerns, guidelines, principles, or behaviors they address. Instead, we take a functionalist perspective in considering which mechanisms relevant to people’s thoughts and experiences relating to morality are examined to draw together the empirical evidence that is available. For each of the research themes described above, we therefore consider the empirical approaches that have been taken by identifying the nature of relevant functions or mechanisms that have been examined. This will help document the evidence that is available to support the notion that morality matters for the way people think about themselves, interact with others, live and work together in groups, and relate to other groups in society. In considering the different functions morality may have, we distinguish between four levels at which mechanisms in social psychology are generally studied (see also Ellemers, 2017; Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012).

Intrapersonal Mechanisms

All the ways in which people consider, think, and reason by themselves to determine what is morally right refer to intrapersonal mechanisms. Even if these considerations are elicited by social norms or reflect the behavior observed in others, it is important to assess the extent to which they emerge as guiding principles for individuals to be used in their further reasoning, for their judgments of the self and others, for their behavioral displays, or for the emotions they experience. Thus, such intrapersonal mechanisms are relevant for questions relating to each of the five research themes we examine.

Interpersonal Mechanisms

The way people relate to others, respond to their moral behaviors, and connect to them tap into interpersonal mechanisms. Again we note that such mechanisms are relevant for research questions in all five research themes, as relations with others can inform the way people reason about morality, the way they judge other individuals or groups, the way they behave, as well as the emotions they experience and the self-views they have.

Intragroup Mechanisms

The role of moral concerns in defining group norms, the tendency of individuals to conform to such norms, and their resulting inclusion versus exclusion from the group all indicate intragroup mechanisms relevant to morality. Considering how groups influence individuals is relevant for our understanding of the way people reason about morality and the way they judge others. It also helps us understand the moral behavior individuals are likely to display (for instance, in public vs. private situations), the emotions they experience in response to the transgression of specific moral rules by themselves or different others, and the self-views they develop about their morality.

Intergroup Mechanisms

The tendency for social groups to endorse specific moral guidelines as a way to define their distinct identity, disagreements between groups about the nature or implications of important values, or moral concerns that stem from conflicts between groups in society all refer to intergroup mechanisms relevant to morality. Here too, examination of such mechanisms is relevant to research questions in each of the five research themes we distinguish. These may inform the tendency to interpret the prescription to be “fair” differently, depending on the identity of the recipients of such fairness, which helps understand people’s moral reasoning and the way they judge the morality of others. Intergroup relations may also help understand the tendency to behave differently toward members of different groups, as well as the emotions and self-views relating to such behaviors.

In sum, we argue that each of these four levels of analysis offers potentially relevant approaches to understand the mechanisms that can shape people’s moral concerns and their judgments of others. Mechanisms at all four levels can also affect moral behavior and have important implications for the emotions people experience and the self-views they hold. Reviewing whether and how empirical research has addressed relevant mechanisms at these four levels thus offers a better understanding of how morality operates in the social regulation of individual behavior (see also Carnes, Lickel, & Janoff-Bulman, 2015; Ellemers, 2017; Janoff-Bulman & Carnes, 2013).

Questions Examined

The functionalist perspective we have outlined above is central to how we conceptualize morality in this review. We built a database containing research that is relevant for this review by including all studies in which the authors indicated their research design or measures to speak to issues relating to morality. Thus, we do not limit ourselves to the examination of specific guidelines or behaviors as representing key features of morality, but consider the broad range of situations that can be interpreted in terms of their moral implications (see also Blasi, 1980). We argue that many different principles or behaviors can acquire moral overtones, and our main interest is to examine what happens when these are considered as indicating the morally “right” versus “wrong” way to behave in a particular situation. We think this latter aspect reflects the essence of theoretical accounts that have emphasized the ways in which morality and moral judgments regulate the behavior of individuals living in groups (Rai & Fiske, 2011; Tooby & Cosmides, 2010). As indicated above, this implies that—given the abstract nature of universal moral values—the specific behavior that is seen as moral can shift, depending on the social context (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Rai & Fiske, 2011), as well as the relevant norms or features that characterize distinct social groups (Giner-Sorolla, 2012; Greene, 2013). Shared moral standards go beyond other behavioral norms in that they are used to define whether an individual can be considered a virtuous and “proper” group member, with social exclusion as the ultimate sanction (Tooby & Cosmides, 2010; see also Ellemers & Van den Bos, 2012). In the remainder of this review, we will examine the empirical approaches to examining morality in social psychology from this functionalist perspective:

Emerging trends: We built a database containing bibliometric characteristics of all studies relevant to our review. This allows us to consider relevant trends in the emergence of published studies, comparing these with general developments in the field of social psychology. We will consider differences in the development of interest in the five types of research questions we distinguish and detail the different mechanisms that are studied to examine questions falling within each of these themes. In this way, we aim to examine the effort researchers have made over the years to understand what they see as the psychological antecedents and implications of moral behavior. We also assess whether and how these emerging efforts have addressed the intrapersonal, interpersonal, intragroup, and intergroup mechanisms relating to morality.

Influential views: We will identify which (theoretical) publications external to our database are most frequently cited in the empirical publications included in our database. We see these as seminal approaches that have influenced researchers with an interest in morality. We also assess which empirical publications in our database receive the most cross-citations from other researchers on morality and are frequently cited in the broader literature. This will help understand which theoretical perspectives and empirical approaches have been most influential in further developing this area of research.

Types of studies: We will use standardized bibliometric techniques to identify interrelated clusters of research and characterize the way these clusters differ from each other. We consider the different types of research questions asked in each of the themes we distinguish and relate them to clusters of studies carried out to specify the empirical approaches that have typically been adopted to address questions within each research theme. This elucidates which conclusions can be drawn from the studies that are available to date and how these contribute to broader insights on the psychology of morality.

By considering the empirical literature in this way, we seek to determine whether and how relevant theoretical perspectives on human morality and the types of research questions they raise are reflected in empirical studies carried out. In doing this, we will assess to what extent this work addresses the role of shared identities in the development of moral guidelines, takes into account the limits of self-reported individual dispositions as proxies for moral behaviors, and considers the interplay between moral principles, guidelines, and convictions as “thoughts,” on one hand, and actual behaviors and emotions as “experiences,” on the other.

Method

Data Collection Procedure

The data collection was carried out entirely online using the WoS engine. Information was derived from three databases: the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED, 1945-present), the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI, 1956-present), and the Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI, 1975-present). These database choices were determined by user account access. The category criterion was set to “Psychology Social.” The search query was “moral*” whereby the results listed all empirical and review articles featuring the word “moral” within the source’s title, keywords, or abstract.

The publications initially found in this way were manually screened to determine whether they should be included in our review of empirical studies on morality. Criteria to include a publication in the set accordingly were (a) that it was an English-language publication, (b) that it had been published in a peer-reviewed journal, (c) that it contained an original report of qualitative or quantitative empirical data (either in a correlational or an experimental design), and (d) that it contained a manipulation or a measure that the authors indicated as relevant to morality.

The complete set of studies examined here was collected in three waves (see Appendix 1, in Supplementary materials). Each wave consisted of an electronic search using the procedure and inclusion criteria detailed above. The publications that came up in the electronic search were first screened to remove any review or theory papers that did not report original data. The empirical publications that were retained were assessed for relevance to our research question by checking whether the study or studies reported actually included a manipulation or measure that was identified by the authors as relating to morality.

The initial search was done in 2014 and included all publications that had appeared in 2000 through 2013, of which 419 met our inclusion criteria. A second wave of data collection was carried out in 2016 and 2017 to add two more years of empirical publications that had appeared in 2014 and 2015. This yielded 221 additional publications that were included in the set. The data collection was completed with a third wave of data collection conducted in 2018. Here, the same procedure was used to add 275 empirical studies that had been published in 2016 and 2017. In this third wave of data collection, we also searched for publications that had appeared before 2000 and were listed in WoS. This yielded 372 additional studies published from 1940 through 1999. Together, these three waves of data collection yielded a total number of 1,278 studies on morality published from 1940 through 2017 that we collected for this review (see Appendix 2, in Supplementary materials).

We note that complete records of main publication details are only available from 1981 onward, and complete full-text records of publications in WoS are only available from 1996 onward. This is why statistical trends analyses will only be conducted for studies published from 1981 onward, and full bibliometric analyses can only be carried out for the main body of 989 studies on morality published from 1996 through 2017 for which complete publication details are digitally available.

Data Coding

Coding Procedure and Interrater Reliability

During the first wave of data collection, a coding scheme was jointly developed by the two first authors. Different coders used this scheme to code groups of publications in different waves of data collection. This was decided by determining the main prediction examined and inspecting the study design and measures that were used. In each phase of data coding, ambiguous cases were flagged, and publication details were further examined and discussed with other coders to reach a joint decision on the most appropriate classification. Each time this occurred, the coding scheme was further specified.

After completion of the third wave of data collection, interrater reliability was determined for the full database included in this review. The codes assigned by five different coders in the first and second wave of data collection, and by six additional coders in the third wave of data collection, were checked by the second group of six coders. An online random number generator was used to randomly select 20 entries for six subsets of years examined (1940 through 2017) that contained about 200 publications each. This resulted in 120 entries (roughly 10% of all publications included) sampled to assess interrater reliability. Each group of 20 entries was then assigned to a second coder and coded in an empty file. Only after completing the 20 entries did the second coder compare their codings with the original codings. The overall interrater agreement was good. For the levels of analysis at which morality was examined, coders were in agreement for 84% of the entries coded. When determining how to classify the main research question under one of the research themes, coders agreed on 84.3% of the entries.

Levels of Analysis

For each entry, we inspected the study design and measures that were used to assess the level at which the mechanism under investigation was located. We distinguish four levels which mirror the categories that are commonly used to characterize different types of mechanisms addressed in social psychological theory (e.g., in textbooks): (a) research on intrapersonal mechanisms, which studies how a single individual considers, evaluates, or makes decisions about rules, objects, situations, and courses of action; (b) research on interpersonal mechanisms, which examines how individuals perceive, evaluate, and interact with other individuals; (c) research on intragroup mechanisms, investigating how people perceive, evaluate, and respond to norms or behaviors displayed by other members of the same group, work or sports team, religious community, or organization; and (d) research on intergroup mechanisms, focusing on how people perceive, evaluate, and interact with members of different cultural, ethnic, or national groups. We also include here research that explicitly aims to examine how members of distinct group differ from each other in how they consider morality.

Interrater agreement was 74% for intrapersonal mechanisms, 83% for interpersonal mechanisms, 92% for intragroup mechanisms, and 88% for intergroup mechanisms.

Research Themes

For each entry, we decided what was the main goal of the research question that was addressed. At the first wave of data collection, the first two authors listed all the keywords provided by the authors of studies included and decided how these could be classified into the five research themes we distinguish in our model. We used this as a starting point to develop our coding scheme, in which ambiguities were resolved through deliberation, as specified above. In this case, coders were instructed to choose a single theme that represented the main focus of the research question in each of the entries included (which could contain multiple studies). Cases where coders thought multiple research themes might be relevant were flagged and further studied and discussed with other coders to determine the primary focus of the research question. Interrater agreement was 68% for moral reasoning, 89% for moral behavior, 84% for moral judgment, 87% for moral self-views, and 95% for moral emotions.

Moral reasoning

Here, we included all research questions that try to capture the moral guidelines people endorse. These include questions about what people consider to be morally right by considering their ideas of what “good” people are generally like or questions about what guidelines people endorse to indicate what a moral person should do. Some researchers aim to examine which choices people think should be made in hypothetical dilemmas and vignettes, asking about people’s positions on specific issues (e.g., gay adoption, killing bugs for science), or wish to assess which values are guiding principles in their life (e.g., fairness, purity). Under this theme, we also classified research questions aiming to examine how moral choices and decisions may differ, depending on specific concerns or situational goals that are activated implicitly (e.g., clean vs. dirty environment) or explicitly (e.g., long-term vs. short-term implications). We note that some of the research questions we included under this theme are labeled by their authors as being about “moral judgment,” as they use this term more broadly than we do. However, in our delineation of the different types of research questions—and in our coding scheme for the five thematic clusters we distinguish—we reserve the term moral judgments for a specific set of research questions, which address the way in which people judge the morality of a another individual or group. Research questions investigating people’s judgments about the general morality of a particular decision or course of action—which capture one’s own moral guidelines—fall under the theme of “moral reasoning” in our coding scheme.

Moral judgments

Under this research theme, we classify all research questions addressing ways in which we evaluate the morality of other individuals or groups. We include research questions examining how the general character of specific individuals is evaluated in terms of perceived closeness of the target to the self or overall positivity/negativity of the target (e.g., in terms of likeability, familiarity, or attractiveness). We also consider under this theme research questions aiming to uncover how people assign moral traits (honesty etc.) or moral responsibility to the individual for the behavior described (guilty, intentionally inflicting harm, deserving of punishment). Similarly, we include research questions addressing the judgments of group targets (existing social groups, companies, communities) in terms of overall positivity/negativity, specific moral traits (e.g., trustworthiness), negative emotions raised, or implicit moral judgments implied in lexical decisions. In this cluster, we also consider research questions addressing the perceived severity of behaviors described, wondering whether people think it merits punishment, or affecting the level of empathy versus dehumanization they experience toward the victims of moral transgressions.

Moral behavior

Here, we include research questions addressing self-reported past behavior or behavioral intentions, as well as reports of (un)cooperative behavior in real life (e.g., volunteering, donating money, helping, forgiving, citizenship) or deceitful behavior in experimental contexts (e.g., cheating, lying, stealing, gossiping). We also include questions addressing implicit indicators of moral behavior (e.g., word completion tendencies, speech pattern analysis, handwipe choices). Research questions under this theme consider these behavioral reports as expressing internalized personal norms, convictions, or beliefs, in relation to indicators of “moral atmosphere,” descriptive or injunctive team or group norms, family rules, or moral role models. We also include under this theme research questions that address moral behavior in relation to situational concerns (e.g., moral rule reminders, cognitive depletion) or specific virtues (e.g., care vs. courage).

Moral emotions

This theme includes research questions in which emotions are considered in response to recollections of real-life events, behaviors, and dilemmas, including significant historical or political events. We also include research questions examining whether such emotions (after being evoked with experimental procedures) can induce participants to display morally questionable behavior (e.g., in a computer game, in response to a provocation by a confederate) or when prompted with situational primes (e.g., pleasant or abhorrent pictures, odors, faces, or transgressive scenarios). Research questions addressing emotional responses people experience in relation to morally relevant issues or situations (guilt, shame, outrage, disgust) are also included under this theme.

Moral self-views

We classified under this research theme all research questions that address the way different aspects of people’s self-views relate to each other (e.g., personality characteristics with self-stated inclinations to display moral behavior), as well as research questions addressing the way experimentally induced behavioral primes, reminders of past (individual or group level) moral transgressions, or the moral superiority of others relate to people’s self-views. This research theme includes research questions addressing personality inventories or trait lists of moral characteristics (e.g., honesty, fairness), as well as self-stated moral motivations or moral ideals (e.g., do not harm) that participants can either explicitly claim as self-defining or implicitly (by examining implicit associations with the self or response times). In addition, we include questions addressing the stated willingness to display moral or immoral behavior (e.g., lie, cheat, help others, donate money or blood), which is also used to indicate the occurrence of moral justifications or moral disengagement to maintain a moral self-view.

Bibliometric Procedures

Temporal Trends and Impact Development

The data on relevant publications included in this review were linked to the bibliometric WoS database present at the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) at Leiden University (Moed, De Bruin, & Van Leeuwen, 1995; Van Leeuwen, 2013; Waltman, Van Eck, Van Leeuwen, Visser, & Van Raan, 2011a, 2011b). At the time these analyses were prepared, the CWTS in-house database contained relevant indicators for records covering the period 1981 through 2017 (see Appendix 3, in Supplementary materials).

Seminal Publications

We identified two types of seminal publications. First, we assessed which (theoretical or empirical) publications outside our set (excluding methodological publications) are most frequently cited in the publications we examined. Second, we determined which of the empirical publications within our set have received an outstanding number of citations, within the field of morality research, as well as in the wider environment (the general WoS database).

In both cases, the analysis of seminal papers was conducted in three steps. First, we detected publications that were highly cited within this set of studies on morality and recorded in which research theme they were located. Second, within each research theme, we focused on the top 25 most highly cited publications from outside the set and—reflecting the smaller number of publications to choose from—the top 10 most highly cited publications within the set of studies on morality. We then identified how many citations these had received in the publications included in this review to determine a top three of seminal papers outside this set and a top three of seminal papers within this set, for each of the five research themes represented. We also examined how frequently these seminal papers were cited in the wider context of the whole WoS database.

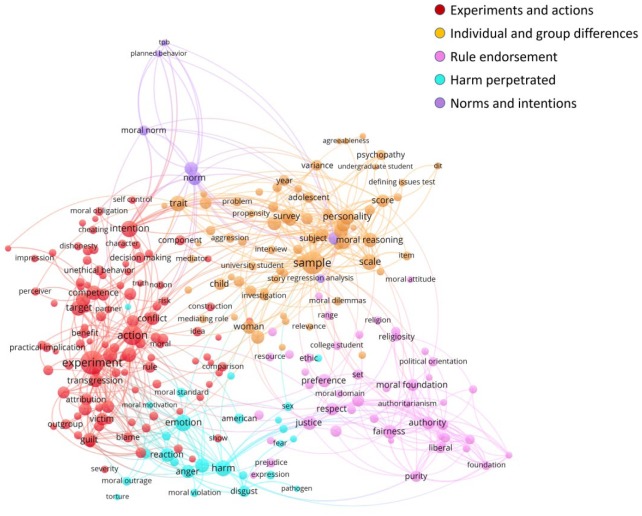

Clusters of Approaches

We used VOSviewer as a tool (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010, 2014, 2018) for mapping and clustering (Waltman, Van Eck, & Noyons, 2010) to visualize the content structure in the descriptions of empirical research on morality that we selected for this review. The analysis determines co-occurrences of so-called noun phrase groups in the titles and abstracts of the publications included in the analysis. Because full records of titles and abstracts are only available for studies published from 1996 onward, this analysis could only be conducted for the set of studies published from 1996 through 2017. Co-occurrences of noun phrase groups are indicated as clusters in a two-dimensional space where (a) closeness (vs. distance) between words indicates their relatedness, (b) larger font size of terms generally indicates a higher frequency of occurrence, and (c) shared color codes indicate stronger interrelations. We use these clusters to indicate the empirical approaches described in the titles and abstracts of studies included in this review and relate these to the different types of research questions we classified into five themes.

Results

Trends in Presence and Impact

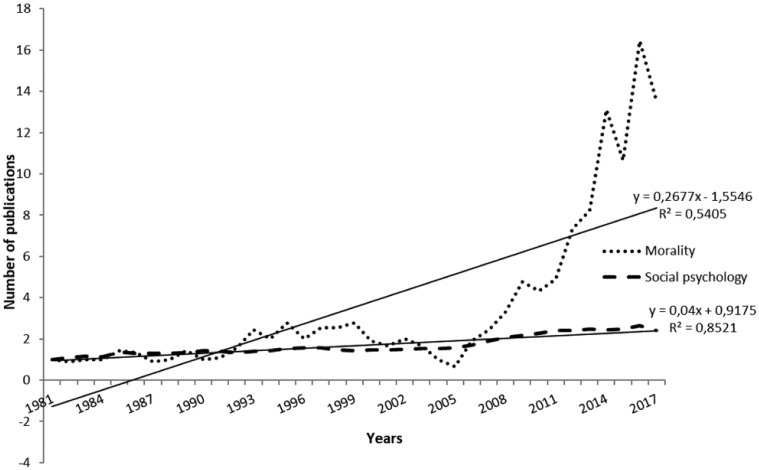

When we compare trends in publication rates over time, we see that in social psychology publications have increased from about 1,500 per year in 1981 to 4,000 per year since 2014. The absolute numbers in publications on morality included in our review are much lower: Here, we found 10 publications per year in 1981, increasing to over 100 per year since 2014. Thus, the absolute number of publications on morality research remains relatively small compared with the whole field of social psychology. Yet, in comparison, the increase is much steeper for publications on morality, when both trends are indexed relative to the number observed in 1981 (see Figure 2). The regression coefficient is considerably larger for publications on morality (0.27) than for publications on social psychology (0.04). The R2 further indicates that a linear trend explains 85% of the overall increase observed in publications on social psychology, while the trend in studies on morality is less well captured with a linear equation (R2 = .54). Indeed, the increase in the number of publications on morality that were published from 2005 onward is much steeper than before, with a regression coefficient of 1.22 and an R2 for this linear trend of .9.

Figure 2.

Indexed trends and regression coefficients for social psychology as a field and morality as a specialism, WoS, 1981-2017.

Note. WoS = Web of Science.

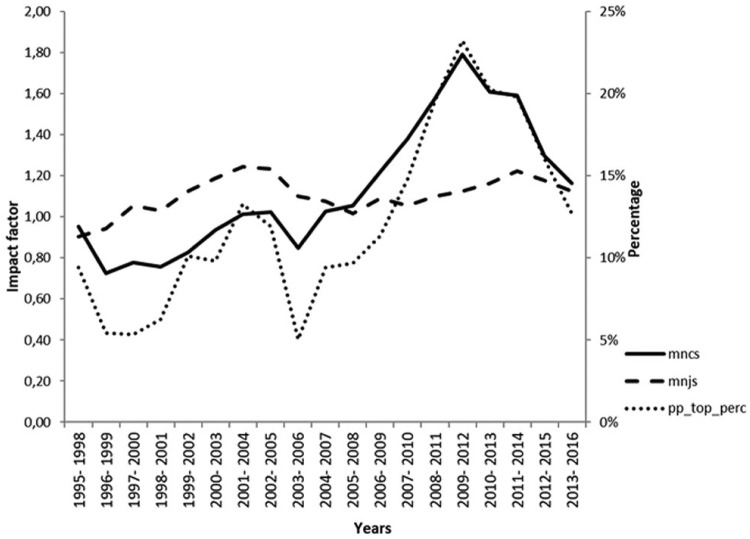

When we assess the impact of the studies on morality included in our review, we see the average impact of these publications, the journals in which they are published, and the percentage of top-cited publications going up consistently (see Figure 3). These field-normalized scores show that the impact of studies on morality is clearly above the average in the field, since 2005. At the same time, there is a steady decrease in the percentage of uncited papers, as well as the proportion of self-citations, and increasing collaboration between authors from different countries (see supplementary materials).

Figure 3.

Trends in impact scores in morality, WoS, 1981-2017, indicating the average normalized number of citations (excluding self-citations; mncs), the average normalized citation score of the journals in which these papers are published (mnjs), and the proportion of papers belonging to the top 10% in the field where they were published (pp_top_perc).

Note. WoS = Web of Science.

Emerging Themes

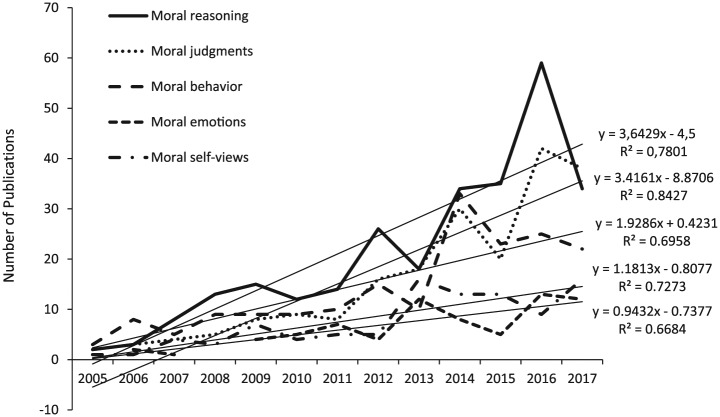

When we distinguish between the types of research questions addressed, this reveals that across the board, there is a disproportionate interest in research questions relating to moral reasoning (χ2 = 502.19, df = 4, p < .001). In fact this is the most frequently examined research theme throughout the period examined and has yielded between 35 and 60 publications per year during the past few years. Research questions relating to moral judgments were initially examined less frequently, but from 2013 onward with 30 to 40 publications per year this research theme approaches similar levels of research activity as moral reasoning. The steady stream of publications examining questions relating to moral behavior peaked around 2014 when more than 30 publications were devoted to this research theme, but subsequently this has dropped down to roughly 20 publications per year. Publications on research questions relating to moral emotions and moral self-views have increased during the past few years; however, these remain relatively less examined overall, with around 10 publications per year addressing each of these themes. When we compare how these themes developed since the interest of researchers in examining morality increased so rapidly after 2005, we clearly see these differential trends. During this period, the number of studies addressing moral reasoning increases more quickly than studies on moral judgments, as well as—in decreasing order—moral behavior, moral self-views, and moral emotions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparative trends in the development of research themes in morality research, 2005-2017.

Mechanisms Examined

In a similar vein, we assessed trends visible in the intrapersonal, interpersonal, intragroup, and intergroup levels of mechanisms examined in the studies included in our review. Overall, the interest in these different types of mechanisms is not distributed evenly (χ2 = 688.43, df = 3, p < .001). Most of the studies included in this review have addressed intrapersonal mechanisms relating to morality, and the relative preference for examining mechanisms relevant to morality at the intrapersonal level has only increased during the past years. The number of studies since 2005 examining intragroup mechanisms show a steep linear trend that accounts for the majority of variance observed (regression coefficient: 6.35, R2 = .78). Although interpersonal mechanisms were initially less examined, the increased research interest in morality since 2005 is also visible in the number of studies that have addressed such mechanisms (regression coefficient: 3.09, R2 = .85). However across the board, the examination of intragroup mechanisms remains relatively rare in this literature, with less than 10 studies per year addressing such issues. Here, the regression coefficient is much lower (0.59) and matches the observed variance less well (R2 = .64). The examination of intergroup mechanisms is only slightly more popular; however, a linear trend (with a regression coefficient of 0.76) does not explain this trend very well (R2 = .25).

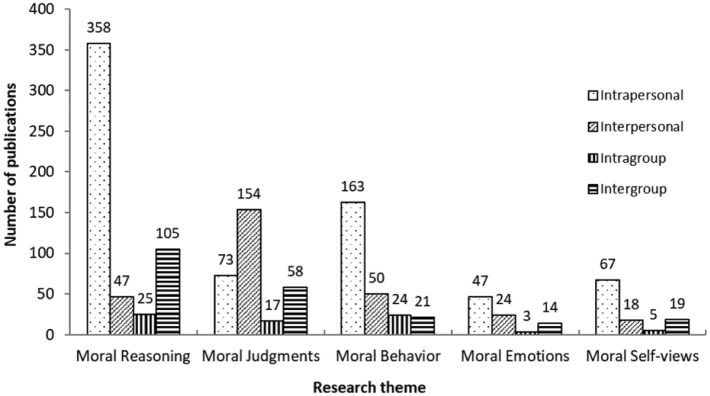

When we assess this per research theme (see Figure 5), we see that the strong emphasis on intrapersonal mechanisms that is visible across all research themes is less pronounced in research questions addressing moral judgments (χ2 = 249.48, df = 12, p < .001). In research on moral judgments, the interest in interpersonal mechanisms is much larger. In fact this research theme accounts for the majority of the studies in our review that examine interpersonal mechanisms. The interest in intragroup mechanisms is very rare across the board. It is perhaps most clearly visible in research questions relating to moral behavior. The interest in intergroup mechanisms is relatively small, but more or less the same across the five research themes we examined.

Figure 5.

Number of studies addressing mechanisms at different levels of analysis, specified per research theme, 1940 – 2017.

Seminal Publications

In the seminal publications outside the set (see Table 2), one publication comes up as a top three seminal paper in more than one research theme. This is the publication by Haidt (2001) in which he develops his theory on moral intuition. Clearly, this publication has been highly influential in developing this area of research. It has also been extremely well cited in the WoS database more generally and can be seen as an important development that prompted the increased interest in research on morality during the past 10 to 15 years. However, besides this one paper, there is no overlap between the five research themes in the top three seminal publications that characterize them. This substantiates our reasoning that different clusters of research questions can be distinguished and underlines the validity of the criteria we used to classify the studies reviewed into these five themes.

Table 2.

Top-three Seminal Papers for Each Research Theme, Published Outside the Set.

| Rank in research theme | Number of citations in data set | Authors | Journal | Title | Publication year | Number of citations in WoS | mncs | mnjs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral reasoning | ||||||||

| 1 | 59 | Haidt, J. | Psychological Review | The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment | 2001 | 1994 | 52.59 | 10.37 |

| 2 | 36 | Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. | Psychological Bulletin | Political conservatism as motivated social cognition | 2003 | 1238 | 34.77 | 9.55 |

| 3 | 35 | Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. | Science | An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment | 2001 | 1360 | 32.18 | 13.44 |

| Moral judgments | ||||||||

| 1 | 41 | Haidt, J. | Psychological Review | The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment | 2001 | 1994 | 52.59 | 10.37 |

| 2 | 29 | Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. | Trends in Cognitive Sciences | Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence | 2007 | 790 | 22.25 | 5.44 |

| 3 | 20 | Gray, K., Young, L, Waytz, A. | Psychological Inquiry | Mind perception is the essence of morality | 2012 | 154 | 10.97 | 4.95 |

| Moral behavior | ||||||||

| 1 | 29 | Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. | Journal of Marketing Research | The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance | 2008 | 543 | 23.69 | 2.16 |

| 2 | 24 | Blasi, A. | Psychological Bulletin | Bridging moral cognition and moral action: A critical review of the literature | 1980 | 594 | 24.15 | 7.41 |

| 3 | 17 | Ajzen, I. | Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes | The theory of planned behavior | 1991 | 14495 | 327.35 | 8.49 |

| Moral emotions | ||||||||

| 1 | 17 | Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. | Annual Review of Psychology | Moral emotions and moral behavior | 2007 | 605 | 21.51 | 13.71 |

| 2 | 16 | Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. | Psychological Bulletin | Guilt: An interpersonal approach | 1994 | 631 | 20.55 | 10.69 |

| 3 | 14 | Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., Barlow, D. H. | Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | Are shame, guilt and embarrassment distinct emotions? | 1996 | 460 | 7.02 | 3.42 |

| Moral self-views | ||||||||

| 1 | 11 | Zhong, C. B., & Liljenquist, K. | Science | Washing away your sins: Threatened morality and physical cleansing | 2006 | 323 | 9.69 | 10.26 |

| 2 | 10 | Haidt, J. | Psychological Review | The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment | 2001 | 1994 | 52.59 | 10.37 |

Note. The rank order within each theme is specified according to the number of citations within the data set examined, which not always corresponds to the total number of citations in WoS. We consider publications as seminal to research on morality when they attract at least 10 citations within the data set examined. As a result of this criterion, we only identified two external papers that were seminal to research on moral self-views. WoS = Web of Science.

Going through the five themes and their top three seminal papers additionally revealed that there are two empirical studies that have been highly influential in this literature. These are not included in our set because they were not published in a psychology journal and hence did not meet our inclusion criteria. In fact, part of the appeal in citing the fMRI study by Greene et al. (2001) in research on moral reasoning or the physical cleansing study by Zhong and Liljenquist (2006) in research on moral self-views may be that these were published in the extremely coveted journal Science—which is not a regular outlet for researchers in social psychology. Indeed, there has been some concern that these high visibility publications—and the media attention they attracted—have led multiple researchers to adopt this same methodology for further studies, perhaps hoping to achieve similar success (Bauman et al., 2014; Graham, 2014; Mooijman & Van Dijk, 2015). The drawback of this publication strategy is that this may have led many researchers to continue examining different conditions affecting trolley dilemma and handwipe choices, instead of broadening their investigations to other issues relating to morality (Hofmann et al., 2014; Lovett et al., 2015).