Abstract

Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are key regulators of the cell cycle. Most of our understanding of their functions has been obtained from studies in single-cell organisms and mitotically proliferating cultured cells. In mammals, there are more than 20 cyclins and 20 CDKs. Although genetic ablation studies in mice have shown that most of these factors are dispensable for viability and fertility, uncovering their functional redundancy, CCNA2, CCNB1, and CDK1 are essential for embryonic development. Cyclin/CDK complexes are known to regulate both mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. While some mechanisms are common to both types of cell divisions, meiosis has unique characteristics and requirements. During meiosis, DNA replication is followed by two successive rounds of cell division. In addition, mammalian germ cells experience a prolonged prophase I in males or a long period of arrest in prophase I in females. Therefore, cyclins and CDKs may have functions in meiosis distinct from their mitotic functions and indeed, meiosis-specific cyclins, CCNA1 and CCNB3, have been identified. Here, we describe recent advances in the field of cyclins and CDKs with a focus on meiosis and early embryogenesis.

Keywords: cyclin, CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase, meiosis, gametogenesis, cell cycle, spermatogenesis, oogenesis

A comprehensive review on genetic studies of cyclins and CDKs in mouse germ cell development.

Introduction

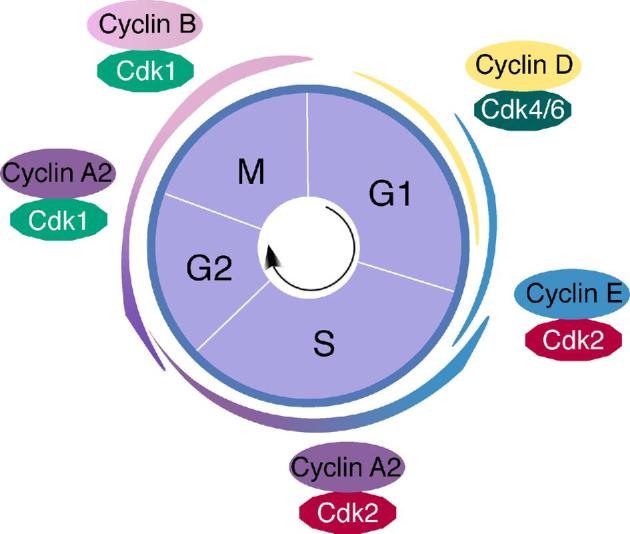

Cell cycle progression is tightly regulated by cyclins and their catalytic partners—cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) [1–3]. Cyclins are a large group of proteins characterized by the presence of a CDK-binding domain called a ‘cyclin-box’. Cyclins along with CDKs regulate progression through the G1, S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle (Figure 1) via a variety of mechanisms: cyclical synthesis and degradation, post-translational modification, and sub-cellular localization. Based on biochemical studies, major cyclins and CDKs have been shown to function at specific stages of the mitotic cell cycle (Figure 1) [4]. At the G1 phase, binding of D-type cyclins activates CDK4/CDK6 followed by activation of CDK2 by cyclin E. These cyclin/CDK complexes promote S phase entry by inactivating retinoblastoma protein (pRB) through phosphorylation. In S phase, cyclin A2/CDK2 promotes S phase progression and regulates G2 entry. In late G2 phase, cyclin A2 activates CDK1 to facilitate the onset of M phase, and cyclin B/CDK1 drives the G2-M transition. The cyclin B/CDK1 activity peaks at the M phase. Strikingly, as discussed in detail later, mouse genetic studies have shown that only CDK1, CCNA2 and CCNB1 are essential for mitotic cell cycle progression.

Figure 1.

Overview of the mitotic cell cycle. A classical model of cyclin/CDK in the mitotic cell cycle is based on biochemical studies in cultured cells. The major types of cyclins (A, B, D, E) and CDKs (CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6) are depicted.

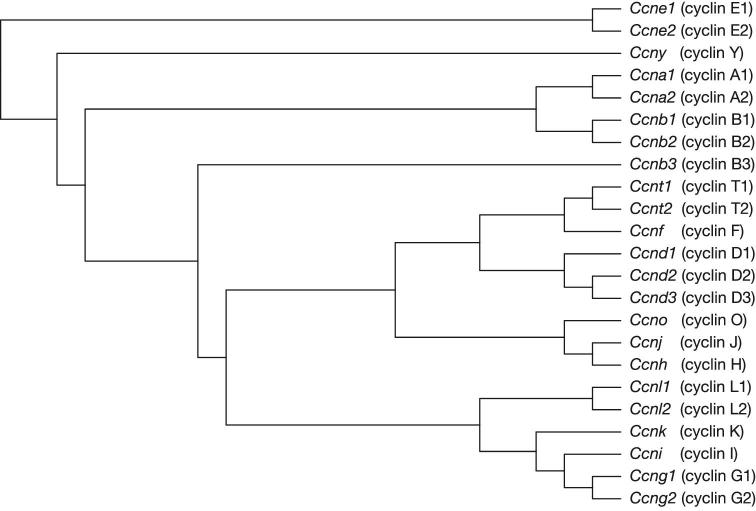

In mice, there are at least 23 distinct cyclins (Figure 2), seventeen of which have been studied through genetic ablation (Table 1). The majority of cyclin-deficient mice are viable, revealing extensive functional redundancy among cyclins. Cyclins and CDKs have been most thoroughly studied in cultured mitotic cells and in the context of cancer, as dysregulation of the mitotic cell cycle is a hallmark of tumorigenesis. However, recent studies have uncovered important roles for cyclins and CDKs in the regulation of the meiotic cell cycle, which are highlighted in this review.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of mouse cyclin family members. Maximum likelihood analysis was conducted using RAxML [110]. NCBI accession numbers: NM_007628 (Ccna1), NM_009828 (Ccna2), NM_172301 (Ccnb1), NM_007630 (Ccnb2), NM_183015 (Ccnb3), NM_007631 (Ccnd1), NM_009829 (Ccnd2), NP_001075104 (Ccnd3), NM_007633 (Ccne1), NM_009830 (Ccne2), NM_007634 (Ccnf), NM_009831 (Ccng1), NM_007635 (Ccng2), NM_023243 (Ccnh), NM_017367 (Ccni), NM_172839 (Ccnj), NM_009832 (Ccnk), NM_019937 (Ccnl1), NM_207678 (Ccnl2), NM_001081062 (Ccno), NM_009833 (Ccnt1), NM_028399 (Ccnt2), NM_026484 (Ccny).

Table 1.

Phenotypes of mouse cyclin mutants.

| Gene | Viability | Fertility Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ccna1 | Viable | Male sterile | [24] |

| Ccna2 | Embryonic lethal E5.5 | [40] | |

| Ccna2 Zp3-Cre | Viable | Lagging chromosome in MII | [31] |

| Ccnb1 | Embryonic lethal E3.5 | [47] | |

| Ccnb1 Stra8-Cre | Viable | Male fertile | [59] |

| Ccnb1 Ddx4-Cre | Viable | Male sterile | [59] |

| Ccnb1 Gdf9-Cre | Viable | Female sterile | [62] |

| Ccnb2 | Viable | Fertile | [47] |

| Ccnb3 | Viable | Male fertile; female sterile | [73, 74] |

| Ccnd1 | Viable | Fertile | [112] |

| Ccnd2 | Viable | Male hypoplastic testis; female sterile | [80] |

| Ccnd3 | Viable | Fertile | [113] |

| Ccne1 | Viable | Fertile | [94] |

| Ccne2 | Viable | Male subfertile | [94] |

| Ccne1/e2 Stra8-Cre | Viable | Male sterile | [97] |

| Ccng1 | Viable | Fertile | [114] |

| Ccng2 | Viable | Fertile | [114] |

| Ccni | Viable | Fertile | [115] |

| Ccno | Viable | Infertile | [116] |

| Ccnt1 | Viable | Fertile | [117] |

| Ccnt2 | Embryonic lethal E5.5 | [118] | |

| Ccny | Viable | Fertile | [119] |

Meiosis, a cell division unique to germ cells, is characterized by one round of DNA replication followed by two rounds of chromosome segregation. Therefore, in sexually reproducing organisms, meiosis generates haploid gametes. Even though the meiotic S-phase is quite similar to the mitotic S-phase in terms of DNA replication, meiosis diverges from mitosis and requires specialized cell cycle proteins to ensure that there are two consecutive segregation events [5]. In meiosis I, homologous chromosomes align, undergo recombination between non-sister chromatids, and separate from their homologous pair, while in meiosis II, sister chromatids segregate from each other. A lengthened prophase I of meiosis is important to ensure reciprocal exchange of genetic materials between homologous chromosomes, which together with random chromosome segregation increases genetic diversity in gametes. Sexual dimorphism adds another layer of complexity to meiotic regulation, as germ cells of both sexes undergo meiosis, yet differ drastically in temporal regulation and the number of resultant gametes.

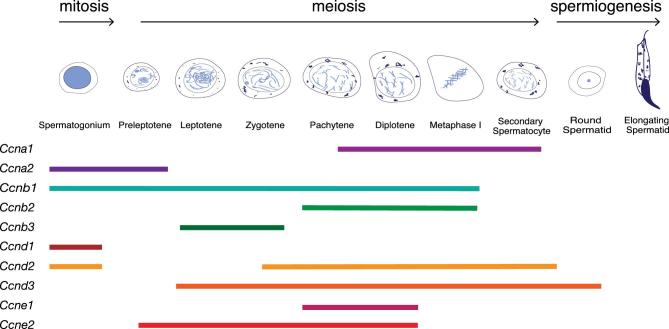

In the developing embryo, primordial germ cells (PGCs) migrate to and colonize the genital ridges [6, 7]. After sex determination (embryonic day 12.5 in mouse—E12.5), germ cell development diverges between males and females. In males, PGCs become prospermatogonia, which cease proliferation around E15 and only resume mitosis at postnatal day 3. During this week-long period of mitotic arrest, prospermatogonia undergo genome-wide epigenetic reprograming and establish de novo paternal imprinting [6]. The molecular mechanisms underlying mitotic arrest and resumption of mitosis in prospermatogonia remain unknown. After birth, spermatogenesis relies on a pool of spermatogonial stem cells formed from some of the initial prospermatogonia, and sperm are continually produced through adulthood due to the presence of spermatogonial stem cells [8, 9]. Meiosis initiates postnatally in males (Figure 3). In juvenile males, spermatogonia that do not retain stem cell properties go through a series of differentiations until they reach the preleptotene spermatocyte stage, signaling the onset of meiosis I [9]. Prophase I of meiosis is further divided into four stages: leptotene, zygotene, pachytene, and diplotene stages (Figure 3) [5]. Prophase I of meiosis is comparable to the G2 phase in the mitotic cell cycle. Therefore, the progression of spermatocytes from diplotene to metaphase I is equivalent to the G2-M transition in mitosis. After meiosis I, secondary spermatocytes divide to produce haploid round spermatids, which then mature into elongating spermatids and eventually to spermatozoa. Throughout adulthood, this process repeats itself in waves of spermatogenesis, and takes roughly 35 days for each new round of spermatogenesis in mice and 70–80 days in humans [9, 10].

Figure 3.

Diagram of cyclin expression during mouse spermatogenesis. This figure was redrawn based on the outline of Figure 2 from this review [111]. Each line represents the qualitative expression of each cyclin in the different germ cell types at the protein level.

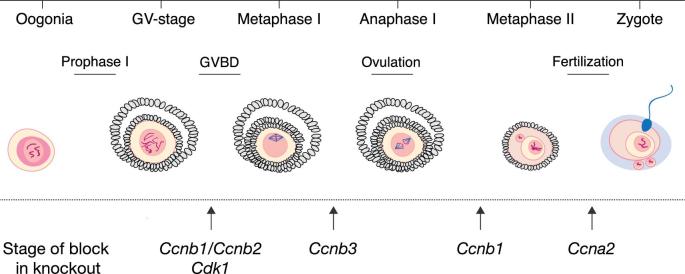

As in males, female germ cells begin as PGCs. After sex determination, PGCs become oogonia and undergo a proliferative mitotic phase with incomplete cytokinesis to form germ cell nests, in which germ cells are connected by intercellular bridges [11]. Unlike prospermatogonia, oogonia enter meiosis I between E13.5 and E15.5, progress to the diplotene stage at birth, and remain arrested at the diplotene (dictyate) stage until ovulation [12, 13]. Concurrent with germ cell nest breakdown, some oocytes undergo apoptosis—a phenomenon known as oocyte attrition—to eliminate poor quality oocytes [14]. The level of retrotransposon LINE1 is implicated in natural oocyte attrition in mouse [14]. Other hypotheses (death by neglect, death by defect, or death by self-sacrifice) were proposed to explain oocyte attrition, but none were proven [15]. Shortly after birth, primordial follicles form [16]. During the reproductive years, oocytes cyclically mature and acquire meiotic and developmental competence; that is, the ability to resume and complete meiosis I and to be fertilized and support embryonic development [17]. During ovulation, oocytes are released from the dictyate arrest following gonadotropin stimulation, specifically a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH), and complete meiosis I, resulting in the release of a polar body. Ovulated oocytes progress through meiosis II and arrest again at metaphase II, completing meiosis II only if they are fertilized (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Point of action of cyclins and CDK1 in meiotic progression in mouse oocytes. Oocytes deficient for both Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 are arrested at the GV stage.

Regulating meiosis presents unique challenges for the cell cycle machinery, necessitating mechanisms of control that are vastly different from those found in mitotic cells. For example, male meiotic germ cells must coordinate two rounds of consecutive division without intervening DNA replication. In contrast, female meiotic germ cells must maintain a prolonged prophase I and resume meiosis following periods of arrest. Germ cells accomplish these specialized tasks in part through germ cell-specific cyclins and by controlling the spatio-temporal expression of universal cyclins throughout meiotic progression. As is common in key biological processes, several cyclins are functionally redundant, serving as a fail-safe mechanism to ensure the faithful transmission of genetic material from one generation to the next. In this review, we discuss new insights into the function of several major cyclins and CDKs with an emphasis on their roles in murine meiosis as revealed by gene ablation analysis.

A-type cyclins

Cyclin A was first identified in clam embryos as one of a group of proteins that are cyclically synthesized and destroyed at the onset of M phase in the cell cycle [18]. Swenson et al. showed that cyclin A was sufficient to drive G2 arrested oocytes into M-phase by injecting cyclin A mRNA into Xenopus oocytes [19]. It has since been found that A-type cyclins are present in all multicellular organisms [20]. In humans and mice, there are two cyclin A genes: Ccna1 and Ccna2. Ccna1 is most abundantly expressed in male germ cells [21], whereas Ccna2 is ubiquitously expressed and upregulated in many types of tumors [22, 23]. The contrasting expression patterns of A-type cyclins imply distinct functions in germ cells and somatic cells.

Cyclin A1: a male meiosis-specific factor

Ccna1 expression is restricted to the testis [21]. Within the testis, Ccna1 is expressed in pachytene and diplotene spermatocytes, and its expression declines after meiotic division (Figure 3) [21]. Ccna1−/− mice are viable and females are fertile. However, Ccna1−/− males are infertile due to meiotic arrest at the diplotene stage (Table 1), showing that Ccna1 is required for metaphase (M-phase) entry in spermatocytes [24]. Intriguingly, Ccna1 has been reported to be haplo-insufficient for male fertility in the 129 inbred genetic background [25].

In both mitosis and meiosis, the onset of metaphase is controlled by the heterodimer complex kinase—metaphase promoting factor (MPF; also known as ‘maturation promoting factor’) [26]. Maturation promoting factor is composed of a catalytic subunit, CDK1, and a regulatory subunit, cyclin B. MPF activity is regulated by reversible phosphorylation events on CDK1. Maturation promoting factor is kept inactive in G2 phase due to CDK1 phosphorylation by the kinases WEE1 and MYT1. At the onset of M phase, MPF is activated by dephosphorylation of CDK1 through the action of the phosphatase CDC25 [27]. CCNA1 is known to interact with CDK1 in spermatocytes [21, 24]. Consistent with the meiotic arrest at the diplotene stage in Ccna1−/− males, CDK1 kinase activity is decreased and the Wee1 kinase remains active in Ccna1−/− testes. CCNA1 may contribute to the initial activation of MPF by relieving inhibitory phosphorylation on CDK1 [28]. Okadaic acid, a specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A, induces pachytene spermatocytes to enter the M phase prematurely [29]. Treatment of Ccna1−/− spermatocytes with okadaic acid causes hyperphosphorylation of CDC25, restores MPF activity, and induces the G2-M transition [28]. These studies support that CCNA1 may activate CDC25 at the onset of M-phase during male meiosis.

Cyclin A2: a ubiquitous mitotic factor

CCNA2 is a key regulator of the S-phase and G2-M transition (Figure 1). Unlike Ccna1, Ccna2 is expressed in both somatic and germ cells [22]. In the mitotic cell cycle, CCNA2 is first detected at the onset of S-phase, increases its expression throughout DNA replication and G2-phase, but is destroyed at prometaphase [30–32]. The CDK2/CCNA2 complex localizes to replication foci in the nucleus and promotes DNA replication [33, 34]. Over-expression of Ccna2 in cultured cells can induce early entry into S-phase, suggesting that, under normal circumstances, the accumulation of CCNA2 is rate-limiting for S-phase entry [35, 36]. Although CCNA2 is often associated with CDK2 in S-phase, most CCNA2 is bound to CDK1 in late S-phase; it is hypothesized that this switch in binding partners prevents re-replication of DNA [37–39].

Consistent with its broad expression, disruption of Ccna2 causes early embryonic lethality at E5.5 (Table 1) [40]. The development of Ccna2-null embryos to the early post-implantation stage is surprising. The role of maternal Ccna2 mRNA and protein in Ccna2−/− embryos was examined. The maternal Ccna2 store only persists till the 4-cell stage, suggesting that Ccna2 is not essential during the pre-implantation period [40, 41].

In the testis, Ccna2 is expressed in mitotically dividing spermatogonia and preleptotene spermatocytes (Figure 3) [22, 42]. In the ovary, the CCNA2 protein is present at a low level in all stages of developing oocytes but at a high level in the surrounding granulosa cells [43]. In early stages of embryonic oocyte development (E13.5–E15.5) when oogonia are proliferating and entering meiotic prophase I, CCNA2 protein is nuclear, but in subsequent stages of oocyte development (E16.5 and beyond), CCNA2 protein is cytoplasmic and in low abundance [43]. CCNA2 decreases in prometaphase I but undergoes a resurgence in MII-arrested oocytes [31] and is readily detected in oocytes upon fertilization [44].

Given the embryonic lethality phenotype, it has been difficult to define the role of Ccna2 in germ cell development. However, Zp3-Cre was used to inactivate floxed Ccna2 in postnatal oocytes [31]. Ccna2−/− oocytes show abnormalities in meiosis II spindle formation; however, they display no defects in meiosis I [31]. Specifically, Ccna2−/− oocytes form MI spindles of the proper size and alignment; however, upon exit from MII, Ccna2−/− oocytes have increased incidence of lagging chromosomes and merotelic kinetochore-microtubule attachments [31]. CCNA2 promotes microtubule turnover, and indeed, Ccna2-deficient oocytes have a roughly 50% increase in microtubule stability [31, 45]. Without Ccna2, the spindle may take much longer to organize and correct errors in attachment.

Why is Ccna2 required for MII but not MI in oocytes? One explanation is that because the duration of prometaphase I is substantially longer than prometaphase II, there may simply be more time to correct attachment errors. Alternatively, there may be additional factors that function in promoting microtubule instability during MI [31]. The results from the genetic study are in conflict with results obtained from studies using antibodies to ablate the function of Ccna2 in oocytes [31, 46]. CCNA2 antibody injection experiments reveal a role for CCNA2 in MI entry and sister chromatid separation at MII [46], however, none of these phenotypes have been observed in Ccna2−/− oocytes [31]. The discrepancy in conclusions on the role of CCNA2 in oocytes may lie in the different ablation approaches. One possibility is that the antibody depletion approach may have off-target effects. A second but not mutually exclusive possibility is that antibody injection is an acute depletion approach and thus may reveal a different phenotype than oocytes developing in the absence of CCNA2, in which the CCNA2 deficiency may be compensated by other factors over time.

We do not yet know the function of CCNA2 in embryonic germ cells of either sex, but this could be investigated using different germline-specific Cre drivers such as Ddx4-Cre. Conditional knockouts with promoters activating Cre in later stages of spermatogenesis could also reveal, for example, if CCNA2 is required for proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia and entry into pre-meiotic S phase in preleptotene spermatocytes.

B-type cyclins

B-type cyclins drive G2-M transition in mitosis in partner with CDK1 as MPF (Figure 1). In mouse, there are three B-type cyclins: Ccnb1, Ccnb2, and Ccnb3. Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 are widely expressed [47]. In contrast, Ccnb3 is specifically expressed in germ cells in mouse [48]. Recent knockdown and genetic studies have examined the function of these cyclins in germ cell development, particularly in meiosis.

Cyclin B1/B2: role in mitosis

CCNB1 is a key regulator of CDK1 activities in mitosis and is involved in mitotic entry, nuclear envelope breakdown, and spindle formation [49–51]. As described above, the CCNB1/CDK1 complex is often referred to as MPF; this complex is activated through dephosphorylation by CDC25 [49]. Prior to activation, the complex is predominately cytoplasmic and associated with microtubule networks, but translocates to the nucleus during prophase [49, 50, 52].

CCNB1 is essential for development. Ccnb1-null embryos die before embryonic day 10 [47]. The notion that CCNB1 is required for mitosis has been challenged by RNAi studies showing that cells can undergo mitosis without CCNB1; these studies suggest that CCNB1 and CCNA2 may be redundant in their role of promoting mitotic entry [53–55]. However, the interpretation of these results may be limited by the possibility of incomplete protein depletion by RNAi. Further genetic studies show that Ccnb1-null embryos are arrested in G2 at the 4-cell stage after two normal mitotic divisions in culture, showing that Ccnb1 is required for G2-M transition in the mitotic cell cycle [56]. In addition, Ccnb2 does not compensate for Ccnb1 in the first two embryonic divisions, since Ccnb1/Ccnb2 double mutant embryos are still arrested at the 4-cell stage [56]. Only a small amount of the CCNB1 protein appears to be necessary to trigger mitosis. As with CCNA2, it is likely that the maternal store of CCNB1 is enough to drive the first two rounds of embryonic cleavage [56]. Strikingly, the 4-cell stage arrest in Ccnb1-null embryo is much earlier than the blastocyst stage arrest in Cdk1-null embryo [39].

The functions of Ccnb2 in mitotic and meiotic divisions vary by organisms. In frog (Rana japonica) oocytes, Ccnb2 is required for bipolar spindle formation [57]. Unlike Ccnb1, Ccnb2-null mice are viable and fertile [47].

Cyclin B1/B2: role in germ cell development

In testis, CCNB1 is present in spermatogonia and all stages of primary spermatocytes with high abundance in zygotene spermatocytes [47, 58]. In contrast, CCNB2 is expressed in pachytene, diplotene, and metaphase spermatocytes (Figure 3). Both cyclins are absent in anaphase spermatocytes and post-meiotic spermatids. CCNB1 is found in both the membrane and the cytoplasm, whereas CCNB2 is only associated with the membrane in testis [47].

Conditional deletion of Ccnb1 in gonocytes and spermatogonia shows that it is necessary for mitotic divisions in male germ cells but not for meiosis (Table 1) [59]. In this study, two different Cre (Ddx4-Cre and Stra8-Cre) recombinases were used to inactivate Ccnb1 in mitotic male germ cells and in premeiotic male germ cells, respectively [59]. Males with the Ddx4-Cre conditional deletion show no germ cells in testes at 15 days of age, demonstrating that Ccnb1 is required for mitotic proliferation of gonocytes and spermatogonia. This result is expected given the absence of CCNB2 in spermatogonia. When Ccnb1 is conditionally deleted later in premeiotic male germ cells with Stra8-Cre, the Ccnb1 mutant males have smaller testes but are fertile, suggesting that Ccnb1 is dispensable for later stages of spermatogonial differentiation and for meiosis in spermatocytes. Given the overlapping expression pattern of CCNB1 and CCNB2 in spermatocytes (Figure 3), it is possible that they are functionally redundant in male meiosis. Therefore, meiosis-specific inactivation of Ccnb1 in the absence of Ccnb2 is necessary to test this possibility.

Normally, oocytes are arrested at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage, and meiotic resumption only occurs following ovulation, presumably with the activation of MPF, the CDK1/CCNB1 complex [60]. Both Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 are expressed in growing oocytes and ovulated eggs [58]. These two cyclins are under differential translational control. Ccnb2 is translated independently of CDK1 activity, whereas Ccnb1 translation is inhibited when CDK1 activity is blocked [61]. Although Ccnb2-null mice are fertile, Ccnb2-null oocytes exhibit delayed entry into MI [47, 62]. In addition, knockdown experiments shows that Hec1-dependent CCNB2 stabilization plays a role in the G2-M transition in oocytes [63].

Oocyte-specific inactivation of Ccnb1 using Gdf9-Cre reveals that it is essential for female meiosis; Ccnb1-null oocytes do complete meiosis I and extrude a polar body, but fail to arrest at metaphase II [62]. Surprisingly, CCNB2 levels are upregulated in these knockout oocytes as is MPF activity, possibly because CCNB2 can activate CDK1, allowing Ccnb1−/− oocytes to complete meiosis I [62]. However, CDK1 is not activated in meiosis II in Ccnb1−/− oocytes, because CCNB2 is absent at this stage. Oocytes deficient for both Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 are arrested at the GV stage, supporting the notion that Ccnb2 compensates for Ccnb1 during meiosis I in Ccnb1-deficient oocytes and vice versa [62]. Therefore, both CCNB1 and CCNB2 regulate MPF activity in a redundant manner in meiosis I in oocytes (Figure 4). As in mitosis, only CCNB1 is required for meiosis II in oocytes. This makes sense, as meiosis II is analogous to mitosis in that both involves separation of sister chromatids.

CDK1/CCNB1 kinase activity needs to remain high until metaphase and subsequent degradation of CCNB1, resulting in CDK1 inactivation, allows metaphase exit. Paradoxically, CCNB1 degradation occurs before metaphase I in oocytes. It turns out that in mouse oocytes, CCNB1 is in excess of CDK1 [64]. Unbound CCNB1 is degraded before the CDK1-bound CCNB1 during metaphase. Free CCNB1 is preferentially targeted by APC/C through a motif in the CDK1-binding region, which is masked by CDK1-binding. Therefore, an excess of CCNB1 serves as a degradation decoy substrate of APC/C to maintain CDK1/CCNB1 activity at prometaphase and metaphase in mouse oocytes.

Cyclin B3: a meiosis-specific factor

In contrast with the broad expression of Ccnb1 and Ccnb2, Ccnb3 is specifically expressed in meiotic germ cells in mammals [48, 65]. Ccnb3, first identified in a chicken cDNA library screen, is conserved from nematodes to humans [48, 66]. Strikingly, the CCNB3 protein is three-fold larger due to the expansion of a single coding exon in placental mammals [67]. Although classified as a B-type cyclin, CCNB3 bears characteristics of both A and B-type cyclins and associates with CDK1 and CDK2 in chicken DU249 cells [66, 67]. In flies, CCNB3 promotes the metaphase-anaphase transition in early embryonic divisions, but is not required for mitosis; however, it is essential for female meiosis [68, 69]. The fly CCNB3 stimulates APC/C (anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome) but functions independently of the SAC (spindle assembly checkpoint). In Caenorhabditis elegans, CCNB3 is required for metaphase–anaphase transition in mitosis in early embryos and this function is dependent on an intact SAC [70, 71]. Early studies using RNA in situ hybridization showed that in mouse testis, Ccnb3 is expressed in early prophase I, specifically in leptotene and zygotene stage spermatocytes, but its expression decreases sharply in the pachytene stage, hinting at a role in male meiosis [48]. Ectopic expression of Ccnb3 driven by a mouse transgene leads to abnormality in spermatogenesis [72]. Surprisingly, despite the expression of Ccnb3 in testis, Ccnb3-null males are viable and fertile, showing that it is dispensable for male meiosis [73, 74].

In contrast, Ccnb3−/− female mice are sterile [73, 74]. Ccnb3-null females develop morphologically normal primordial and mature ovarian follicles, however, Ccnb3-null oocytes fail to undergo metaphase I to anaphase I transition [73, 74]. Ccnb3-knockdown oocytes do not extrude a polar body and become arrested at metaphase I [65]. Often there is a discrepancy in phenotypes between knockdown and knockout in oocytes (for example, Ccna2 as described earlier), however, in the case of Ccnb3, the knockout results are strikingly consistent with earlier RNAi studies in mouse oocytes [65]. These studies all propose a mechanism in which CCNB3 is required to activate and/or possibly provide substrate specificity to APC/C [65, 73, 74]. In wild type oocytes, APC/C ubiquitylates MPF and securin for degradation to promote anaphase. Securin is an inhibitor of the protease separase, which cleaves cohesion that holds sister chromatids together. Separase is kept inactive by securin and high levels of MPF activity, and without activation of separase, oocytes do not enter anaphase. In Ccnb3-null oocytes (arrested at metaphase I), CCNB1 and securin fail to be degraded, and MPF activity remains high [73]. Treatment with the CDK inhibitor roscovitine or securin RNAi rescues the polar body extrusion defect and allows completion of meiosis I in Ccnb3-null oocytes [65, 73]. Mouse CCNB3/CDK1 complex exhibits H1 kinase activity in vitro [73]. These studies have demonstrated an important role for CCNB3 in promoting metaphase I to anaphase I transition in oocytes (Figure 4). Despite these findings, the substrates of CCNB3 are unknown. Identification of its target proteins will likely shed light on how CCNB3 activates APC/C in oocytes.

In Ciona intestinalis, CCNB3 regulates the timing of zygotic genome activation [75]. In Ciona embryos, Ccnb3 is responsible for suppressing the zygotic genome activation through the 8-cell stage, as Ccnb3 knockdown results in precocious zygotic genome activation measured through single-cell RNA-seq of individual blastomeres from developing Ciona embryos. Specifically, knockdown of Ccnb3 lengthens the timing of the first embryonic cell divisions in Ciona, and later in development, causes defects in neurulation. These effects are yet to be observed in vertebrates; however, as in Ciona, maternal mRNAs in humans and mice are eliminated at the onset of zygotic genome activation, including a notable decrease in Ccnb3 transcripts, indicating that CCNB3 may function similarly in mammals [75].

D-type cyclins

D-type cyclins are expressed in all proliferating cells and are induced by extracellular mitogens [76]. In mammals, there are three cyclin D isoforms, and all three isoforms interact with CDK4 and CDK6 to drive the G1-S transition in the mitotic cell cycle (Figure 1) [76, 77]. The holoenzymes formed by cyclin D and CDK phosphorylate retinoblastoma protein (pRB); this phosphorylation event inhibits the binding of pRB to E2F transcription factors, allowing for transcription of genes necessary for S-phase entry [78, 79]. Although D-type cyclins are widely expressed, there is a degree of tissue specificity to their expression and correspondingly, the depletion of a particular isoform causes tissue-specific defects [76, 77, 80]. Because the D-type cyclins respond to growth factors and are key regulators of cell growth, all three forms are associated with cancers. Generally, cancer phenotypes correlate with the tissue-specific functions seen in individual knockouts [81–83]. For example, Ccnd1 is associated with mammary carcinoma [84], Ccnd2 is linked with glioblastoma and human testicular cancer [80, 85], and aberrant Ccnd3 activity is observed in T-cell leukemias [85]. These studies show that D-type cyclins are key regulators of proliferation in normal and transformed mitotically dividing cells.

D-type cyclins: functional redundancy in somatic tissues

Because all three D-type cyclins are expressed in most somatic tissues but at different levels, they may be functionally redundant. In fact, mice lacking any one of the D-type cyclins (Ccnd1, Ccnd2, or Ccnd3) are viable (Table 1). Interestingly, inactivation of individual D-type cyclin genes yield highly tissue-specific defects, shedding light on cell-type specific requirements for D-type cyclins despite their ubiquitous expression [76]. Ccnd1-null mice are viable and fertile, and their defects are restricted to the retina and mammary tissue [77, 82, 86]. Ccnd2 has the most restricted expression pattern though it is still expressed in a majority of somatic tissues [80, 81]. Ccnd2 deficiency reduces certain neuronal populations in the cerebellum and causes infertility in female mice attributable to defects in granulosa cells [80, 81]. Although Ccnd3 has the broadest expression pattern, Ccnd3−/− mice exhibit relatively specific defects, namely deficiencies in T-lymphocyte development [78, 87].

Double and triple knockout studies as well as knockin studies have further explored the functional redundancy among D-type cyclins. When Ccnd2 is inserted into the genetic locus of Ccnd1, its subsequent expression can rescue most of the phenotypes seen in Ccnd1-deficient mice [77]. On the contrary, Ccnd3 has a critical role in hematopoiesis [78]. In knockin mice, Ccnd2 expressed from the Ccnd3 locus fails to rescue the block in lymphocyte development in Ccnd3-null mice, showing that Ccnd3 has unique functions in lymphocytes [83]. Double knockouts of cyclin D1 and D2, D1 and D3, or D2 and D3 are all embryonic lethal or result in death shortly after birth [88]. In these double knockout mice, only a single D-type cyclin is expressed but ubiquitously and its tissue-specific expression pattern is lost, showing that there is functional redundancy up to the late gestation stage [88]. Mice lacking all three D-type cyclins die by E16.5 and exhibited defects in hematopoietic stem cell and myocardium development, indicating that most embryonic tissues can proliferate in their absence [89]. Surprisingly, proliferation of cyclin D-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts is nearly normal, suggesting the existence of cyclin D-independent cell cycle progression mechanism [89].

D-type cyclins: expression and function in the gonads

In male germ cells, all three D-type cyclins are expressed, but their expression pattern varies by cell type and developmental stage (Figure 3) [90–92]. Ccnd1 is expressed in gonocytes and spermatogonia. Ccnd2 is also expressed in spermatogonia, specifically in the transition from Aal to A1-type spermatogonia, and in pachytene spermatocytes. Ccnd3 is present in spermatocytes and round spermatids in adult testis [90, 92]. In females, all three D-type cyclins are expressed in oocytes and are concentrated in the nucleus of growing and GV-stage oocytes except CCND2 [93]. CCND1 and CCND2 levels increase at the GV stage, in contrast, CCND3 protein abundance decreases with oocyte maturation after the GV stage [91, 93].

Only Ccnd2-null mice show fertility phenotypes [80]. Ccnd2-null males have hypoplastic testes but are fertile, while females are infertile due to ovulation failure. Oocytes are surrounded by the somatic granulosa cells, which are follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)-responsive. In Ccnd2-null females, oocytes are trapped in follicles and cannot be released. However, oocytes extracted from Ccnd2−/− ovaries can be fertilized in vitro. This study shows that CCND2 is required for FSH-stimulated proliferation of granulosa cells in the ovary.

E-type cyclins

E-type cyclins function in tandem with D-type cyclins to drive the G1/S transition. E-type cyclins associate with CDK2 and possibly other CDKs (Figure 1) [94, 95]. One function of the cyclin E/CDK2 complex is to cause further pRB phosphorylation initiated by the cyclin D/CDK4/6 complexes, though cyclin E also has pRB-independent functions. Unlike D-type cyclins that respond to extracellular mitogenic cues, E-type cyclins are transcriptionally induced by E2F transcription factors and form positive feedback loops to induce their own transcription [96].

Like other cyclins, E-type cyclins are functionally redundant [94]. Ccne1−/− mice are viable and fertile. Ccne2−/− mice also appear normal but males are sub-fertile with smaller testes and reduced sperm count (Table 1). Embryos deficient for both Ccne1 and Ccne2 die before E12.5. Despite the appearance of retarded development, Ccne1/2-deficient embryos have normal morphology; however, placentas associated with these embryos are severely deformed. By tetraploid complementation, Geng et al. injected Ccne1−/−Ccne2−/− embryonic stem cells into tetraploid blastocysts derived from wild type zygotes to create mutant embryos with “wild-type” placentas [94]. In this experiment, Ccne1−/−Ccne2−/− embryos survive to term, showing that E-type cyclins are dispensable for embryogenesis but essential for placenta formation and that placental dysfunction is causal in the early embryonic lethality. In further support, E-type cyclins are required for endoreplication of trophoblast giant cells in the placenta.

In the testis, both E-type cyclins are expressed in spermatocytes (Figure 3) [97]. The CCNE2 protein abundance appears to be higher in spermatocytes than CCNE1. Ccne2−/− males are subfertile with defects in meiosis [94]. Germ cell-specific deletion of Ccne1 in Ccne2−/− males exacerbates the meiotic defects [97]. Spermatocytes deficient for both E-type cyclins exhibit defects in chromosome pairing, chromosomal synapsis, DNA double strand break repair, and telomere stability [97].

In Drosophila oogenesis, cyclin E and CDK2 are required for both germline stem cell proliferation and maintenance [98]. In Xenopus eggs, cyclin E/CDK2 contributes to metaphase II arrest in meiosis by inhibiting APC/C [99]. However, little is known about the function of E-type cyclins in mouse oogenesis.

CDKs: canonical and non-canonical functions in mitosis and meiosis

In mammals, there are as many as 20 different CDKs, yet as is the case for cyclins, mammalian CDKs demonstrate a high degree of functional redundancy [4, 100]. CDK1 is considered to be the crucial M-phase CDK, while CDK2, CDK3, CDK4, and CDK6 are all active in interphase and constitute the so-called interphase CDKs (Figure 1) [101]. Although the great number and diversity of CDKs enables fine-tuned regulation of the cell cycle, only CDK1 is truly essential for cell division [39, 102, 103]. Disruption of Cdk1 is embryonic lethal at the blastocyst stage, whereas mice deficient for Cdk2, or Cdk3, or Cdk4, or Cdk6 are viable [39, 103]. Mouse embryos deficient for all interphase CDKs can even develop to the midgestation stage [103]. Though somewhat surprising, this is logical given the lethal consequences of depleting CDK1-binding partners CCNA2 and CCNB1, as discussed previously. Even more puzzling is that numerous studies in cultured cells have shown an essential role for CDK2 in cell cycle progression (Figure 1), but Cdk2-null mice are viable. It turns out that CDKs compete for binding to cyclins and that CDK1 is able to complex with cyclins A, B, D, and E to complete the cell cycle in the absence of interphase CDKs [103]. Therefore, CDK1 is both necessary and sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle.

Unlike mitosis, meiosis requires both CDK1 and CDK2. Cdk2-null males and females are viable but sterile [104]. Specifically in meiotic prophase I germ cells, CDK2 localizes to telomeres [105]. During the prophase of meiosis I, chromosomes undergo rapid movements to facilitate homologue search and pairing. In meiotic germ cells, telomeres are attached to the nuclear envelope and connect to cytoplasmic microtubules through the nuclear membrane proteins SUN1-KASH5. CDK2 phosphorylates SUN1 [106]. Chromosome attachment to nuclear envelope is common to meiosis in both sexes. CDK2 deficiency leads to a failure in telomere attachment to nuclear envelope, leading to abnormal homologue pairing and defective meiotic recombination [107]. Therefore, the sterility of Cdk2-null mice is due to meiotic arrest. The unexpected role for CDK2 in meiotic prophase I represents its non-canonical function.

CDK1 is required for meiotic progression to metaphase I in spermatogenesis [108]. In this study, Cdk1 was inactivated by Hspa2-Cre, which is expressed in pachytene spermatocytes. Cdk1-deficient spermatocytes progress to the prometaphase stage but fail to reach metaphase I. Treatment of Cdk1-deficient spermatocytes with okadaic acid leads to fully condensed bivalent chromosomes, suggesting that they are competent to be induced into metaphase I in vitro.

CDK1, but not CDK2, is essential for driving meiotic resumption from dictyate arrest in postnatal oocytes [102]. Cdk2-null females are depleted of oocytes postnatally, presumably due to its requirement for chromosome pairing in early prophase I before birth as described above. To investigate the role of CDKs in meiotic resumption in oocytes, Gdf9-Cre was used to inactivate Cdk1 or Cdk2 specifically in postnatal oocytes [102]. Such Cdk2 conditional knockout females are fertile, while Cdk1 conditional knockout females are infertile. Conditional Cdk2-deficient oocytes resume meiosis and arrest normally at metaphase II when cultured; however, Cdk1-deficient oocytes are arrested permanently at the GV stage and fail to undergo GV breakdown, and this defect can be rescued with Cdk1 mRNA injection. During meiotic resumption in wild-type oocytes, PP1, a serine/threonine phosphatase, is phosphorylated and thus inactivated so that lamin A/C, components necessary for nuclear envelope breakdown, becomes phosphorylated and active. In Cdk1-deficient oocytes, PP1 is not phosphorylated, leading to de-phosphorylation of lamin A/C and thus a failure in GV breakdown. This study shows that CDK1, but not CDK2, is required for G2-M transition in meiosis I in fully grown oocytes. Thus, the cyclin B/CDK1 complex confers the canonical MPF activity in oocytes (Figure 4).

Primordial (dormant) and growing oocytes are arrested at the dictyate stage but, unlike fully grown GV oocytes, are incompetent to resume meiosis. Inhibitory phosphorylation of CDK1 regulates the dictyate arrest in growing oocytes [109]. CDK1 is inactivated by phosphorylation at T14 and Y15. CDK1 with T14A and Y15F substitutions (referred to as CDK1AF) is non-phosphorylatable and thus remains constitutively active. While expression of CDK1AF in primordial oocytes leads to DNA damage and rapid oocyte loss, growing oocytes that express CDK1AF resume meiosis prematurely to reach prometaphase I, evidenced by GV breakdown and chromosome condensation. In addition, CDK1AF-expressing growing oocytes accumulate DNA damage and die, due to the activation of the ATM-CHK2-p63 DNA damage response. These results show that phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of CDK1 in primordial and growing oocytes maintains the prophase I arrest and genome integrity, which are important for preserving the ovarian reserve of follicles.

Concluding remarks and remaining questions

Here, we have summarized the function of mammalian cyclins with an emphasis on meiosis. Mouse genetic studies have elucidated the functions of many cyclins in mitosis and, recently, in meiosis (Table 1). A common theme is that most cyclins and CDKs are dispensable for cell cycle progression, but some play a role in fine-tuning the cell cycle in a tissue-specific manner. The association of CDKs with cyclins is dynamic. From an evolutionary point of view, the existence of redundant mechanisms is advantageous to the organisms given the paramount importance of cell cycle progression. Because of the unique characteristics of meiosis, meiosis-specific cyclins such as CCNA1 and CCNB3 have evolved. However, much work is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms of cyclin activity in meiosis and the mechanisms that accommodate redundant functions among cyclins. Although the gene knockout studies have been helpful in decoding the importance of specific cyclins in meiosis, we have limited knowledge of specific cellular targets of cyclins or cyclin/CDK complexes in meiosis. Depletion of some cyclins has little to no effect on fertility; in these instances, what are the compensatory mechanisms? Future studies are needed to investigate the role of cyclins, particularly the germ cell-specific ones, in meiosis and fertility in humans.

Acknowledgements

We thank Seth Kasowitz, Fang Yang, and Yongjuan Guan for comments on the manuscript.

Author Biographical

P. Jeremy Wang, M.D./Ph.D. is a Professor of Developmental Biology in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Wang received his M.D. degree from Beijing University Health Sciences Center in 1990 and Ph.D. in molecular biology and genetics from Cornell University in 1997. His postdoctoral research focused on reproduction genomics in the laboratory of David Page at Whitehead Institute/M.I.T. before joining the Penn faculty in 2002. The research programs in the Wang laboratory focus on the study of meiosis in mice and humans. Current areas of investigation include molecular genetics of meiotic recombination, epigenetics of retrotransposon silencing, and genetic causes of infertility in humans. Functional characterization of a large number of new genes identified in his laboratory has uncovered novel regulatory mechanisms underlying key reproductive processes. Significantly, these mouse studies have important implications for understanding the genetic basis of infertility and birth defects in humans.

P. Jeremy Wang, M.D./Ph.D. is a Professor of Developmental Biology in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Wang received his M.D. degree from Beijing University Health Sciences Center in 1990 and Ph.D. in molecular biology and genetics from Cornell University in 1997. His postdoctoral research focused on reproduction genomics in the laboratory of David Page at Whitehead Institute/M.I.T. before joining the Penn faculty in 2002. The research programs in the Wang laboratory focus on the study of meiosis in mice and humans. Current areas of investigation include molecular genetics of meiotic recombination, epigenetics of retrotransposon silencing, and genetic causes of infertility in humans. Functional characterization of a large number of new genes identified in his laboratory has uncovered novel regulatory mechanisms underlying key reproductive processes. Significantly, these mouse studies have important implications for understanding the genetic basis of infertility and birth defects in humans.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R35GM118052 (to PJW) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01HD034195 (to DJW).

References

- 1. Lim S, Kaldis P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development 2013; 140(15):3079–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene 2009; 28(33):2925–2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnum KJ, O’Connell MJ. Cell cycle regulation by checkpoints. Methods Mol Biol 2014; 1170:29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Risal S, Adhikari D, Liu K. Animal models for studying the in vivo functions of cell cycle CDKs. Methods Mol Biol 2016; 1336:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Handel MA, Schimenti JC. Genetics of mammalian meiosis: regulation, dynamics and impact on fertility. Nat Rev Genet 2010; 11(2):124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leitch HG, Tang WWC, Surani MA. Primordial germ-cell development and epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Curr Top Dev Biol 2013; 104:149–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Rooij DG. Stem cells in the testis. Int J Exp Pathol 1998; 79(2):67–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phillips BT, Gassei K, Orwig KE. Spermatogonial stem cell regulation and spermatogenesis. Phil Trans R Soc B 2010; 365(1546):1663–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griswold MD. Spermatogenesis: the commitment to meiosis. Physiol Rev 2016; 96(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amann RP. The cycle of the seminiferous epithelium in humans: a need to revisit?. J Androl 2008; 29(5):469–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pepling ME, Spradling AC. Female mouse germ cells form synchronously dividing cysts. Development 1998; 125:3323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin W, Jin H, Liu X, Hampton K, Yu H-G. Scc2 regulates gene expression by recruiting cohesin to the chromosome as a transcriptional activator during yeast meiosis. MBoC 2011; 22(12):1985–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng C-W, Bowles J, Koopman P. Control of mammalian germ cell entry into meiosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014; 382(1):488–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malki S, van der Heijden GW, O’Donnell KA, Martin SL, Bortvin A. A role for retrotransposon LINE-1 in fetal oocyte attrition in mice. Dev Cell 2014; 29(5):521–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tilly JL. Commuting the death sentence: how oocytes strive to survive. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2001; 2(11):838–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wear HM, McPike MJ, Watanabe KH. From primordial germ cells to primordial follicles: a review and visual representation of early ovarian development in mice. J Ovarian Res 2016; 9(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schultz RM. From egg to embryo: a peripatetic journey. Reproduction 2005; 130(6):825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Evans T, Rosenthal ET, Youngblom J, Distel D, Hunt T. Cyclin: a protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell 1983; 33(2):389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swenson KI, Farrell KM, Ruderman JV. The clam embryo protein cyclin A induces entry into M phase and the resumption of meiosis in Xenopus oocytes. Cell 1986; 47(6):861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gunbin KV, Suslov VV, Turnaev II, Afonnikov DA, Kolchanov NA. Molecular evolution of cyclin proteins in animals and fungi. BMC Evol Biol 2011; 11(1):224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sweeney C, Murphy M, Kubelka M, Ravnik SE, Hawkins CF, Wolgemuth DJ, Carrington M. A distinct cyclin A is expressed in germ cells in the mouse. Development 1996; 122:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ravnik SE, Wolgemuth DJ. The developmentally restricted pattern of expression in the male germ line of a murine cyclin A, cyclin A2, suggests roles in both mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. Dev Biol 1996; 173(1):69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yam CH, Fung TK, Poon RYC. Cyclin A in cell cycle control and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 2002; 59(8):1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu D, Matzuk MM, Sung WK, Guo Q, Wang P, Wolgemuth DJ. Cyclin A1 is required for meiosis in the male mouse. Nat Genet 1998; 20(4):377–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Meer T, Chan WYI, Palazon LS, Nieduszynski C, Murphy M, Sobczak-Thépot J, Carrington M, Colledge WH. Cyclin A1 protein shows haplo-insufficiency for normal fertility in male mice. Reproduction 2004; 127(4):503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones KT. Turning it on and off: M-phase promoting factor during meiotic maturation and fertilization. Mol Hum Reprod 2004; 10(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oh JS, Han SJ, Conti M. Wee1B, Myt1, and Cdc25 function in distinct compartments of the mouse oocyte to control meiotic resumption. J Cell Biol 2010; 188(2):199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu D, Liao C, Wolgemuth DJ. A role for cyclin A1 in the activation of MPF and G2–M transition during meiosis of male germ cells in mice. Dev Biol 2000; 224(2):388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wiltshire T, Park C, Caldwell KA, Handel MA. Induced premature G2/M-phase transition in pachytene spermatocytes includes events unique to meiosis. Dev Biol 1995; 169(2):557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. den Elzen N, Pines J. Cyclin A is destroyed in prometaphase and can delay chromosome alignment and anaphase. J Cell Biol 2001; 153(1):121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Q-H, Yuen WS, Adhikari D, Flegg JA, FitzHarris G, Conti M, Sicinski P, Nabti I, Marangos P, Carroll J. Cyclin A2 modulates kinetochore-microtubule attachment in meiosis II. J Cell Biol 2017; 216(10):3133–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erlandsson F, Linnman C, Ekholm S, Bengtsson E, Zetterberg A. A detailed analysis of cyclin A accumulation at the G1/S border in normal and transformed cells. Exp Cell Res 2000; 259(1):86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jackman M, Kubota Y, den Elzen N, Hagting A, Pines J. Cyclin A- and cyclin E-Cdk complexes shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. MBoC 2002; 13(3):1030–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H, Nadal-Ginard B. Reversal of terminal differentiation and control of DNA replication: cyclin A and Cdk2 specifically localize at subnuclear sites of DNA replication. Cell 1993; 74(6):979–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Resnitzky D, Hengst L, Reed SI. Cyclin A-associated kinase activity is rate limiting for entrance into S phase and is negatively regulated in G1 by p27Kip1. Mol Cell Biol 1995; 15(8):4347–4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chibazakura T, Kamachi K, Ohara M, Tane S, Yoshikawa H, Roberts JM. Cyclin A promotes S-phase entry via interaction with the replication licensing factor Mcm7. Mol Cell Biol 2011; 31(2):248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Katsuno Y, Suzuki A, Sugimura K, Okumura K, Zineldeen DH, Shimada M, Niida H, Mizuno T, Hanaoka F, Nakanishi M. Cyclin A-Cdk1 regulates the origin firing program in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009; 106(9):3184–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hochegger H, Dejsuphong D, Sonoda E, Saberi A, Rajendra E, Kirk J, Hunt T, Takeda S. An essential role for Cdk1 in S phase control is revealed via chemical genetics in vertebrate cells. J Cell Biol 2007; 178(2):257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Diril MK, Ratnacaram CK, Padmakumar VC, Du T, Wasser M, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) is essential for cell division and suppression of DNA re-replication but not for liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012; 109(10):3826–3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murphy M, Stinnakre M-GG, Senamaud-Beaufort C, Winston NJ, Sweeney C, Kubelka M, Carrington M, Bréchot C, Sobczak-Thépot J. Delayed early embryonic lethality following disruption of the murine cyclin A2 gene. Nat Genet 1997; 15(1):83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Winston N, Bourgain-Guglielmetti F, Ciemerych MA, Kubiak JZ, Senamaud-Beaufort C, Carrington M, Bréchot C, Sobczak-Thépot J, Chot CB, Lle Sobczak-Thé J. Early development of mouse embryos null mutant for the cyclin A2 gene occurs in the absence of maternally derived cyclin A2 gene products. Dev Biol 2000; 223(1):139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ravnik SE, Wolgemuth DJ. Regulation of meiosis during mammalian spermatogenesis: the A-type cyclins and their associated cyclin-dependent kinases are differentially expressed in the germ-cell lineage. Dev Biol 1999; 207(2):408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Persson JL, Zhang Q, Wang XY, Ravnik SE, Muhlrad S, Wolgemuth DJ. Distinct roles for the mammalian A-type cyclins during oogenesis. Reproduction 2005; 130(4):411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fuchimoto D, Mizukoshi A, Schultz RM, Sakai S, Aoki F. Posttranscriptional regulation of cyclin A1 and cyclin A2 during mouse oocyte meiotic maturation and preimplantation development. Biol Reprod 2001; 65(4):986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kabeche L, Compton DA. Cyclin A regulates kinetochore microtubules to promote faithful chromosome segregation. Nature 2013; 502(7469):110–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Touati SA, Cladiè D, Lister LM, Leontiou I, Chambon J-P, Rattani A, Bö F, Stemmann O, Nasmyth K, Herbert M, Wassmann K. Cyclin A2 is required for sister chromatid segregation, but not separase control, in mouse oocyte meiosis. Cell Reports 2012; 2:1077–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brandeis M, Rosewell I, Carrington M, Crompton T, Jacobs MA, Kirk J, Gannon J, Hunt T. Cyclin B2-null mice develop normally and are fertile whereas cyclin B1-null mice die in utero. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1998; 95(8):4344–4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nguyen TB, Manova K, Capodieci P, Lindon C, Bottega S, Wang XY, Refik-Rogers J, Pines J, Wolgemuth DJ, Koff A. Characterization and expression of mammalian cyclin B3, a prepachytene meiotic cyclin. J Biol Chem 2002; 277(44):41960–41969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takizawa CG, Morgan DO. Control of mitosis by changes in the subcellular location of cyclin-B1–Cdk1 and Cdc25C. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000; 12(6):658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jackman M, Lindon C, Nigg EA, Pines J. Active cyclin B1–Cdk1 first appears on centrosomes in prophase. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5(2):143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krämer A, Mailand N, Lukas C, Syljuåsen RG, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA, Bartek J, Lukas J. Centrosome-associated Chk1 prevents premature activation of cyclin-B–Cdk1 kinase. Nat Cell Biol 2004; 6(9):884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hagting A, Jackman M, Simpson K, Pines J. Translocation of cyclin B1 to the nucleus at prophase requires a phosphorylation-dependent nuclear import signal. Curr Biol 1999; 9(13):680–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gong D, Ferrell JE Jr. The roles of cyclin A2, B1, and B2 in early and late mitotic events. MBoC 2010; 21(18):3149–3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Soni DV, Sramkoski RM, Lam M, Stefan T, Jacobberger JW. Cyclin B1 is rate limiting but not essential for mitotic entry and progression in mammalian somatic cells. Cell Cycle 2008; 7(9):1285–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gong D, Pomerening JR, Myers JW, Gustavsson C, Jones JT, Hahn AT, Meyer T, Ferrell JE. Cyclin A2 regulates nuclear-envelope breakdown and the nuclear accumulation of cyclin B1. Curr Biol 2007; 17(1):85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Strauss B, Harrison A, Coelho PA, Yata K, Zernicka-Goetz M, Pines J. Cyclin B1 is essential for mitosis in mouse embryos, and its nuclear export sets the time for mitosis. J Cell Biol 2018; 217(1):179–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kotani T, Yoshida N, Mita K, Yamashita M. Requirement of cyclin B2, but not cyclin B1, for bipolar spindle formation in frog (Rana japonica) oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 2001; 59(2):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chapman DL, Wolgemuth DJ. Isolation of the murine cyclin B2 cDNA and characterization of the lineage and temporal specificity of expression of the B1 and B2 cyclins during oogenesis, spermatogenesis and early embryogenesis. Development 1993; 118:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tang J-X, Li J, Cheng J-M, Hu B, Sun T-C, Li X-Y, Batool A, Wang Z-P, Wang X-X, Deng S-L, Zhang Y, Chen S-R et al.. Requirement for CCNB1 in mouse spermatogenesis. Cell Death Dis 2017; 8(10):e3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Adhikari D, Liu K. The regulation of maturation promoting factor during prophase I arrest and meiotic entry in mammalian oocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014; 382(1):480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Han SJ, Martins JPS, Yang Y, Kang MK, Daldello EM, Conti M. The translation of cyclin B1 and B2 is differentially regulated during mouse oocyte reentry into the meiotic cell cycle. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1):14077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li J, Tang J-X, Cheng J-M, Hu B, Wang Y-Q, Aalia B, Li X-Y, Jin C, Wang X-X, Deng S-L, Zhang Y, Chen S-R et al.. Cyclin B2 can compensate for cyclin B1 in oocyte meiosis I. J Cell Biol 2018; 217(11):3901–3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gui L, Homer H. Hec1-dependent Cyclin B2 stabilization regulates the G2-M transition and early prometaphase in mouse oocytes. Dev Cell 2013; 25(1):43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Levasseur MD, Thomas C, Davies OR, Higgins JMG, Madgwick S. Aneuploidy in oocytes is prevented by sustained CDK1 activity through degron masking in cyclin B1. Dev Cell 2019; 48(5):672–684.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang T, Qi ST, Huang L, Ma XS, Ouyang YC, Hou Y, Shen W, Schatten H, Sun QY. Cyclin B3 controls anaphase onset independent of spindle assembly checkpoint in meiotic oocytes. Cell Cycle 2015; 14(16):2648–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gallant P, Nigg EA. Identification of a novel vertebrate cyclin: cyclin B3 shares properties with both A- and B-type cyclins. EMBO J 1994; 13(3):595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lozano JC, Vergé V, Schatt P, Juengel JL, Peaucellier G. Evolution of cyclin B3 shows an abrupt three-fold size increase, due to the extension of a single exon in placental mammals, allowing for new protein-protein interactions. Mol Biol Evol 2012; 29(12):3855–3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yuan K, O’Farrell PH. Cyclin B3 is a mitotic cyclin that promotes the metaphase-anaphase transition. Curr Biol 2015; 25(6):811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jacobs HW, Knoblich JA, Lehner CF. Drosophila cyclin B3 is required for female fertility and is dispensable for mitosis like cyclin B. Genes Dev 1998; 12(23):3741–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. van der Voet M, Lorson MA, Srinivasan DG, Bennett KL, van den Heuvel S. C. elegans mitotic cyclins have distinct as well as overlapping functions in chromosome segregation. Cell Cycle 2009; 8(24):4091–4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Deyter GMR, Furuta T, Kurasawa Y, Schumacher JM. Caenorhabditis elegans cyclin B3 is required for multiple mitotic processes including alleviation of a spindle checkpoint-dependent block in anaphase chromosome segregation. PLoS Genet 2010; 6(11):e1001218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Refik-Rogers J, Manova K, Koff A. Misexpression of cyclin B3 leads to aberrant spermatogenesis. Cell Cycle 2006; 5(17):1966–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Karasu ME, Bouftas N, Keeney S, Wassmann K. Cyclin B3 promotes anaphase I onset in oocyte meiosis. J Cell Biol 2019; 218(4):1265–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Li Y, Wang L, Zhang L, He Z, Feng G, Sun H, Wang J, Li Z, Liu C, Han J, Mao J, Li P et al.. Cyclin B3 is required for metaphase to anaphase transition in oocyte meiosis I. J Cell Biol 2019; Published online ahead of print, jcb.201808088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201808088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Treen N, Heist T, Wang W, Levine M. Depletion of maternal cyclin B3 contributes to zygotic genome activation in the Ciona embryo. Curr Biol 2018; 28(7):1150–1156.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sherr CJ, Sicinski P. The D-type cyclins: a historical perspective. In: Hinds PW, Brown NE (eds.), D-type Cyclins and Cancer. Cham: Springer; 2018:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Carthon BC, Neumann CA, Das M, Pawlyk B, Li T, Geng Y, Sicinski P. Genetic replacement of cyclin D1 function in mouse development by cyclin D2. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25(3):1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sicinska E, Aifantis I, Le Cam L, Swat W, Borowski C, Yu Q, Ferrando AA, Levin SD, Geng Y, von Boehmer H, Sicinski P. Requirement for cyclin D3 in lymphocyte development and T cell leukemias. Cancer Cell 2003; 4(6):451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dyson N. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev 1998; 12(15):2245–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Geng Y, Parker SB, Gardner H, Park MY, Robker RL, Richards JS, McGinnis LK, Biggers JD, Eppig JJ, Bronson RT et al.. Cyclin D2 is an FSH-responsive gene involved in gonadal cell proliferation and oncogenesis. Nature 1996; 384(6608):470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Koyama-Nasu R, Nasu-Nishimura Y, Todo T, Ino Y, Saito N, Aburatani H, Funato K, Echizen K, Sugano H, Haruta R, Matsui M, Takahashi R et al.. The critical role of cyclin D2 in cell cycle progression and tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem cells. Oncogene 2013; 32(33):3840–3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev 1995; 9(19):2364–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sawai CM, Freund J, Oh P, Ndiaye-Lobry D, Bretz JC, Strikoudis A, Genesca L, Trimarchi T, Kelliher MA, Clark M, Soulier J, Chen-Kiang S et al.. Therapeutic targeting of the cyclin D3:CDK4/6 complex in T cell leukemia. Cancer Cell 2012; 22(4):452–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mohammadizadeh F, Hani M, Ranaee M, Bagheri M. Role of cyclin D1 in breast carcinoma. J Res Med Sci 2013; 18:1021–1025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Houldsworth J, Reuter V, Bosl GJ, Chaganti RS. Aberrant expression of cyclin D2 is an early event in human male germ cell tumorigenesis. Cell Growth Differ 1997; 8:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Parker SB, Li T, Fazeli A, Gardner H, Haslam SZ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell 1995; 82(4):621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bartkova J, Lukas J, Strauss M, Bartek J. Cyclin D3: requirement for G1/S transition and high abundance in quiescent tissues suggest a dual role in proliferation and differentiation. Oncogene 1998; 17(8):1027–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ciemerych MA, Kenney AM, Sicinska E, Kalaszczynska I, Bronson RT, Rowitch DH, Gardner H, Sicinski P. Development of mice expressing a single D-type cyclin. Genes Dev 2002; 16(24):3277–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kozar K, Ciemerych MA, Rebel VI, Shigematsu H, Zagozdzon A, Sicinska E, Geng Y, Yu Q, Bhattacharya S, Bronson RT, Akashi K, Sicinski P. Mouse development and cell proliferation in the absence of D-cyclins. Cell 2004; 118(4):477–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Beumer TL, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Gademan IS, Kal HB, de Rooij DG. Involvement of the D-type cyclins in germ cell proliferation and differentiation in the mouse. Biol Reprod 2000; 63(6):1893–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhang Q, Wang X, Wolgemuth DJ. Developmentally regulated expression of cyclin D3 and its potential in vivo interacting proteins during murine gametogenesis. Endocrinology 1999; 140(6):2790–2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ravnik SE, Rhee K, Wolgemuth DJ. Distinct patterns of expression of the D-type cycling during testicular development in the mouse. Dev Genet 1995; 16(2):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kohoutek J, Dvořák P, Hampl A. Temporal distribution of CDK4, CDK6, D-type cyclins, and p27 in developing mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 2004; 70(1):139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Geng Y, Yu Q, Sicinska E, Das M, Schneider JE, Bhattacharya S, Rideout WM, Bronson RT, Gardner H, Sicinski P. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell 2003; 114(4):431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Koff A, Giordano A, Desai D, Yamashita K, Harper JW, Elledge S, Nishimoto T, Morgan DO, Franza BR, Roberts JM. Formation and activation of a cyclin E-cdk2 complex during the G1 phase of the human cell cycle. Science 1992; 257(5077):1689–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Siu KT, Rosner MR, Minella AC. An integrated view of cyclin E function and regulation. Cell Cycle 2012; 11(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Martinerie L, Manterola M, Chung SSW, Panigrahi SK, Weisbach M, Vasileva A, Geng Y, Sicinski P, Wolgemuth DJ. Mammalian E-type cyclins control chromosome pairing, telomere stability and CDK2 localization in male meiosis. PLoS Genet 2014; 10(2):e1004165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ables ET, Drummond-Barbosa D. Cyclin E controls Drosophila female germline stem cell maintenance independently of its role in proliferation by modulating responsiveness to niche signals. Development 2013; 140(3):530–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tunquist BJ, Schwab MS, Chen LG, Maller JL. The spindle checkpoint kinase bub1 and cyclin e/cdk2 both contribute to the establishment of meiotic metaphase arrest by cytostatic factor. Curr Biol 2002; 12(12):1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Malumbres M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol 2014; 15(6):122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Enders GH. Mammalian interphase cdks: dispensable master regulators of the cell cycle. Genes & Cancer 2012; 3(11-12):614–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Adhikari D, Zheng W, Shen Y, Gorre N, Ning Y, Halet G, Kaldis P, Liu K. Cdk1, but not Cdk2, is the sole Cdk that is essential and sufficient to drive resumption of meiosis in mouse oocytes. Hum Mol Genet 2012; 21(11):2476–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Santamaría D, Barrière C, Cerqueira A, Hunt S, Tardy C, Newton K, Cáceres JF, Dubus P, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature 2007; 448(7155):811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol 2003; 13(20):1775–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Ashley T, Walpita D, de Rooij DG. Localization of two mammalian cyclin dependent kinases during mammalian meiosis. J Cell Sci 2001; 114:685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Viera A, Alsheimer M, Gomez R, Berenguer I, Ortega S, Symonds CE, Santamaria D, Benavente R, Suja JA. CDK2 regulates nuclear envelope protein dynamics and telomere attachment in mouse meiotic prophase. J Cell Sci 2015; 128(1):88–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Viera A, Rufas JS, Martínez I, Barbero JL, Ortega S, Suja JA. CDK2 is required for proper homologous pairing, recombination and sex-body formation during male mouse meiosis. J Cell Sci 2009; 122(12):2149–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Clement TM, Inselman AL, Goulding EH, Willis WD, Eddy EM. Disrupting cyclin dependent kinase 1 in spermatocytes causes late meiotic arrest and infertility in mice. Biol Reprod 2015; 93(6):137, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Adhikari D, Busayavalasa K, Zhang J, Hu M, Risal S, Bayazit MB, Singh M, Diril MK, Kaldis P, Liu K. Inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 mediates prolonged prophase I arrest in female germ cells and is essential for female reproductive lifespan. Cell Res 2016; 26:1212–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30:1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wolgemuth DJ, Manterola M, Vasileva A. Role of cyclins in controlling progression of mammalian spermatogenesis. Int J Dev Biol 2013; 57:159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Chen B, Pollard JW. Cyclin D2 compensates for the loss of cyclin D1 in estrogen-induced mouse uterine epithelial cell proliferation. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17:1368–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Cooper AB, Sawai CM, Sicinska E, Powers SE, Sicinski P, Clark MR, Aifantis I. A unique function for cyclin D3 in early B cell development. Nat Immunol 2006; 7:489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ohno S, Ikeda J, Naito Y, Okuzaki D, Sasakura T, Fukushima K, Nishikawa Y, Ota K, Kato Y, Wang M, Torigata K, Kasama T et al.. Comprehensive phenotypic analysis of knockout mice deficient in cyclin G1 and cyclin G2. Sci Rep 2016; 6:39091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Liu C, Zhai X, Zhao B, Wang Y, Xu Z. Cyclin I-like (CCNI2) is a cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) activator and is involved in cell cycle regulation. Sci Rep 2017; 7:40979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Núnez-Ollé M, Jung C, Terré B, Balsiger NA, Plata C, Roset R, Pardo-Pastor C, Garrido M, Rojas S, Alameda F, Lloreta J, Martín-Caballero J et al.. Constitutive cyclin O deficiency results in penetrant hydrocephalus, impaired growth and infertility. Oncotarget 2017; 8:99261–99273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Oven I, Brdičková N, Kohoutek J, Vaupotič T, Narat M, Matija Peterlin B. AIRE recruits P-TEFb for transcriptional elongation of target genes in medullary thymic epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27:8815–8823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Kohoutek J, Li Q, Blazek D, Luo Z, Jiang H, Peterlin BM. Cyclin T2 is essential for mouse embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:3280–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zi Z, Zhang Z, Li Q, An W, Zeng L, Gao D, Yang Y, Zhu X, Zeng R, Shum WW, Wu J. CCNYL1, but not CCNY, cooperates with CDK16 to regulate spermatogenesis in mouse. PLoS Genet 2015; 11:e1005485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]