Abstract

Probiotics are in use for physiological boosting, health supplement, and for treatment since historical time. Recently, the to-and-fro pathways linking the gut with the brain, explaining the indirect communication via modulation of immune function and levels of various neurotransmitters, have been discovered, but how precisely these modulations alter the levels of neurotransmitters contributing to the cognitive and other symptom improvements in patients with schizophrenia remains a new arena of research for psychiatry and psychology professionals. The germ-free mice experiments have been the game changer in the mechanistic exploration. The antimicrobial usage alters the local gut flora and hence is associated with psychiatric side effects that strengthen the association further. The changes in the genetics of these bacteria with different types of diet and its correlation with neurotransmitters production capacity and the psyche of the individual are indeed an emerging field for schizophrenia research. Redressal of issues such as manufacturing, the shelf life of probiotics, and stability of probiotics in the gut milieu, in the presence of food, secretions, and exact volume needed for particular age group will help in refining the dose duration of probiotic therapy. Clinical trials are underway for evaluating safety and efficacy in schizophrenia. The gut microorganism transplant and pharmacovigilance of probiotics are important areas yet to be addressed accurately. This paper elucidates the pathways, clinical studies, availability of probiotics in the Indian market with their composition, regulatory issues in India about the probiotic use, and future of probiotic research in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Brain function, gut microbiome, immune system, neurotransmitters, pharmacology, probiotics, schizophrenia

Introduction

Eukaryotic microorganisms, bacteria, archaea, and viruses that dwell inside and outside our bodies constitute the human gut microbiome and have evolved together with the host over the years to develop a sophisticated and reciprocally useful association. These microorganisms have a remarkable contribution in health and disease physiologies. These microorganisms not only add value to the metabolism function but also protect against infections, thus contributing to the development of our immune system. Through these necessary actions, it influences most of our physiological functions directly or indirectly.[1] Of late, an enormous evolution in illustrating the constitution of the gut microorganisms can be seen. This has inculcated interest for research on the usefulness of communications among the gut flora physiology and pathology of patient phenotypes. Improvement in understanding gut microbiomes leads to the development of pharmaceutical compounds known as probiotics.[2]

Association of the Gut Microbiome and Brain function

After birth, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of a newborn starts getting colonized with the same microorganisms found in the maternal vaginal tract or the hospital environment of a delivery room. Cesarean section born babies displayed a lesser amount of Bacteroides and Bifidobacteria species, while the same cohort babies found to have more Clostridium difficile, in contrast to infants born vaginally.[3] A study conducted by Ehninger et al.[4] showed the integrity and functional capacity of early microbial colonization in premature babies. In general, premature births have reduced the variety of organisms that partake in individual commensalism but increased those partaking in interindividual commensalism in relation to their gastrointestinal tract.[4] Gut microorganisms have been increasingly assumed to make a vital contribution in the central nervous system (CNS) growth and maturity.[2] Gamma aminobutyrate (GABA), a major CNS inhibitory neurotransmitter, is produced from Lactobacillus and is the first bacterium that is colonized with most vaginally born infants. Other vital neurotransmitters, such as dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), and norepinephrine, are also formed from gut microbiome.[5] Evidence shows that some specific species, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, generate GABA, whereas some species, such as Saccharomyces, Escherichia, and Bacillus spp., make noradrenaline in the gut and Candida albicans, Escherichia, Streptococci, and Enterococci spp. produce serotonin (5-HT). Bacillus spp. produces DA, and acetylcholine is produced from Lactobacillus.[6] The presence of a single-nucleotide polymorphism in microbial genes, which can explain pathophysiology and are linked to similar polymorphisms in the human genome, in guts of different types of diseased population would be deemed interesting. Epigenetic study of microbes in guts of patients can unfold several immunological pathways of disease evolution.

Gut Microbiome and Schizophrenia

The gut flora can be easily manipulated by dynamic etiologies, such as eating habits, drugs, antibiotics consumption, and disturbed sleep–wakefulness cycle.[7] A connection between antimicrobial usage and brain function alterations is apparent from the psychological adverse drug reactions of antimicrobials, which vary from anxiety to psychosis.[8] Alcohol consumption as well as smoking habits have all been shown to affect gut flora constitution substantially.[9] What is considered an unacceptable change in the milieu of gut flora, leading to psychopathological evolution, is a current arena for psychiatry research. A study showed that less carbohydrate and more fat in the diet are linked with altered gut flora, consequently leading to decreased synaptic plasticity and susceptibility toward anxiety symptoms.[10] Schizophrenia and autism incidence has been found to be higher in the C. difficile diseased population. This association was further explained by a phenylalanine derivative synthesized and released by the same bacteria in the gut that is known to regulate catecholamine levels in the brain.[11] Twin and adoption genetic studies also strengthen the schizophrenia and gut microbiome linkage by examining the incidence of the diseased population in study groups. A greater microbial commonality is identified in monozygotic twins in comparison to that in dizygotic twins and corroborates with the incidence of the schizophrenia in twin studies.[12] It has also been observed that prematurely born babies are at a risk of developing schizophrenia at a later age.[13]

As the gut microbiome development regarding the variety and the number of organisms is essential to fuel brain plasticity via the expressions of the adequate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) receptors, it can be said that altered human gut microbiome may have a significant contribution to the NMDA receptor hypoactivity, as observed in patients with schizophrenia.[14] The gut microbiome analysis can be critical in exposing contribution of microbial infections and antimicrobial use, like varied lipopolysaccharide forms are also linked to type II diabetes and obesity development through an inflammatory response.[15] The mechanistic exploration for these effects is not yet well elucidated, but it can be assumed that they may be connected to an increase in the inflammatory molecules along with an alteration in dietary habits via direct actions of minerals, fatty acids, and vitamins.[16] Improvement in lactose digestion has been well documented with probiotic supplementation and logically reducing the impedance, created in the brain, by affecting the serotonin action via high intestinal lactose concentration through tryptophan metabolism.[17] Probiotic supplementation has a promising potential for patients with schizophrenia who commonly have stress, low nutrition, lactose sensitivity, and inflammatory stress. Lactobacillus supplementation in asymptomatic obese individuals has been found to reduce the fat content of subcutaneous and visceral abdomen.[18] Obesity treatment potential of probiotics can have the same promise as that of patients with schizophrenia, which is apparent from their risk of getting diagnosed by metabolic syndrome.

Further rationale to consider probiotic administration in patients with schizophrenia are due to the fact that GI upset, mainly constipation, is a typical scenario in this patient population pool. Approximately 50% of patients with schizophrenia have constipation and may pose a severe threat. Patients on clozapine have shown constipation as a common concurrent problem, but other antipsychotic medicines are also associated with this side effect.[19] Lately, Song et al.[20] and Pedrini et al.[21] showed that pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from gut microbiome were shown to be elevated in patients with schizophrenia compared to that in control patients. Hope et al.[22] and Severance et al. showed a clear association between these immune markers and the progression of disease symptoms. There exist numerous reviews in the literature that suggest the role of this uncontrolled neuroinflammation in the schizophrenia etiopathogenesis.[23] Long-term macrophage activation with the subsequent increase in the secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2) by GI T lymphocytes and IL-2 receptor action is projected as the critical biologic pathway of schizophrenia development. According to the studies in the literature, the medical comorbidity of metabolic syndrome has also made contributions to some extent by upregulating immune and inflammatory systems.[24] The supplementation of galacto-oligosaccharide once a day for three weeks in a healthy volunteer study led to an appreciably low salivary cortisol awakening action as compared to placebo supplementation group, signifying the importance of gut microbiome in mental health manipulation. It was associated with the reduced attention toward negative versus positive cues.[25] Interestingly, although the usefulness of such approaches can be seen at present, the patients are recommended high-fiber foods with whole grain, essentially prebiotics.[26] Early case-control studies have well established the association of toxoplasmosis infection with the incidence of early-onset schizophrenia.[27] Minocyclines have produced tangible therapeutic benefits in psychiatric diseases, such as depressive disorders psychosis and alcohol disorders. Minocycline action also attributes to commensal flora alterations out of several hypotheses.[28] A study conducted by Sandler et al.[29] showed that through the use of vancomycin in an eight-week therapy, conventional C. difficile management improved behavior and communication scorings in children presented with autism. However, this was a reversible phenomenon that showed a rise in scoring immediately after discontinuation.[29]

Preclinical Evidence for Probiotics in Schizophrenia

A ground-breaking research performed by Diaz Heijtz et al.[30] revealed that the mice that lacked microorganisms in gut completely during their stages of development, known as germ-free (GF) mouse, had a rise in DA throughput in the corpus striatum together with an anxious, irritable phenotype. The whole array of behavior in this type of animal was highly mimicking the schizophrenia along significant cognitive deficit, an ability for normalization if the mice is colonized quickly. The behavioral discrepancies observed in this type of mice were significantly evident in males as compared to that in females––a point corroborating with the schizophrenia epidemiology. GF mouse was observed to carry two times higher quantity of DA in the brain as compared to the wild type.[30]

Asano et al.[31] studied the complex association between the GI microbiome and the source of functionally active catecholamines, comprising DA in the mice gut lumen. Tryptophan levels, the serotonin precursor, were increased in the GF animal’s plasma, signifying an immune pathway that mediates the gut microbiome’s influence on the brain serotonin action. In spite of the higher serotonin turnover in the GF mice, the crucial enzyme isoform accountable for the conversion of serotonin from tryptophan, that is, Tph2 gene expression, was normal.[31] The mouse model of maternal immune-activation was also acknowledged to show schizophrenia features. A study revealed that the offspring of the parental immune-activation showed a different plasma metabolomics outline. The remedial action taken improved the GI porousness, rehabilitated microorganism configuration, and corrected flaws in communication, anxiousness, and sensorimotor performance.[32]

Accruing data concludes the vital actions of genes of gut microorganisms in CNS function, providing abundant functionally active catecholamines to the evolving besides mature brain. These neurotransmitters influence the healthy and diseased state explaining the social difficulties. For example, analogous to humans, phencyclidine brings out substantial behavioral alterations in rats that can be treatable by schizophrenia medications and also by the butyric acid, gut microorganism origin histone deacetylase inhibitor.[33] In the early life of maternal contact-deprived rodents, use of Bifidobacteria led to the humoral function behavioral deficiencies normalization and baseline noradrenaline-level reinstatement in the CNS, whereas in a GI infection and inflammation rodent model, exposure to Bifidobacterium normalized anxiety symptoms.[34] Largely, probiotic supplements actions appear to facilitate social activity alterations through the vagus nerve stimulation or through the cytokine-level modulation. Oligosaccharides intake in mice injected with lipopolysaccharides also reduced anxiety scores––action that seems to be associated with the variation in the CNS IL-1β and serotonin 2A receptor expression.[35] A recent animal study showed that the n–3 polyunsaturated fatty-acid chronic intake corrected the altered gut microbiome seen along with decrease of the corticosteroid level.[36]

Clinical Evidence of Outcomes of Probiotics Supplementation in Schizophrenia

The pioneering trial conducted by Dickerson et al.[37] observed the role of probiotic supplementation, in the 14-week placebo-controlled setting, in patients with resistant schizophrenia. No significant difference was found in schizophrenia through the use of the symptom severity scale between the probiotic administration and placebo groups.[37] Tomasik et al.[38] observed immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia as an add-on to conventional atypical antipsychotic regimen via cytokine modulation, which is not affected by atypical antipsychotic drugs. Another placebo-controlled cohort study performed by Severance et al.[39] showed separate biomarker C. albicans antibody levels to be inversely linked with GI symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. In another case-control study, Severance et al.[23] measured CD14 seropositivity in patients with schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia (n = 141) and concluded that CD14 seropositivity is responsible for three times increase in the risk of having schizophrenia (odds ration [OR] = 3.09, P < 0.001) in comparison to control group. The same CD14 seropositivity was associated with gluten antibodies in newly diagnosed patients with schizophrenia (P < 0.0001, r2 = 0.27).[40] The clinical studies with probiotics in schizophrenia are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical studies with probiotics in the treatment of schizophrenia

| Clinical trials on probiotics in the schizophrenia treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of patients | Follow-up duration | Intervention | Assessment biomarker | Outcome |

| Dickerson et al.[37] | 65 | 14 weeks | Adjunctive probiotics vs. placebo | PANSS | No reduction in disease symptoms, but gut function improvement was noted |

| Self-made GI motility questionnaire | |||||

| Tomasik et al.[38] | 47 | 14 weeks | Adjunctive probiotics vs. placebo | vWF, MCP-1, BDNF, RANTES, and MIP-1 | Better GI function in the probiotic group could be due to the immune function alteration |

| Severance et al.[39] | 56 | 14 weeks | Adjunctive probiotic vs. placebo | Candida albicans antibody levels | Better GI function found to be linked with a C. albicans IgG antibody titer fall: a pattern of decrease in positive symptoms |

| Case-control study on probiotics in the schizophrenia treatment | |||||

| Study | Number of patients | Follow-up duration | Intervention | Assessment biomarker | Outcome |

| Severance et al.[23] | 114 | 14 weeks | Adjunctive to antipsychotic treatment | Serological surrogate markers of bacterial translocation (soluble CD-14) (CD-14) and lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP) | LBP correlated with body mass index in schizophrenia. No drug cytokine interaction between antipsychotic and sCD14 or LBP levels |

PANSS = positive and negative syndrome scale; vWF = von Willebrand factor; MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; BDNF = brain derived neurotrophic factor; RANTES = regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted; MIP-1 = macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha

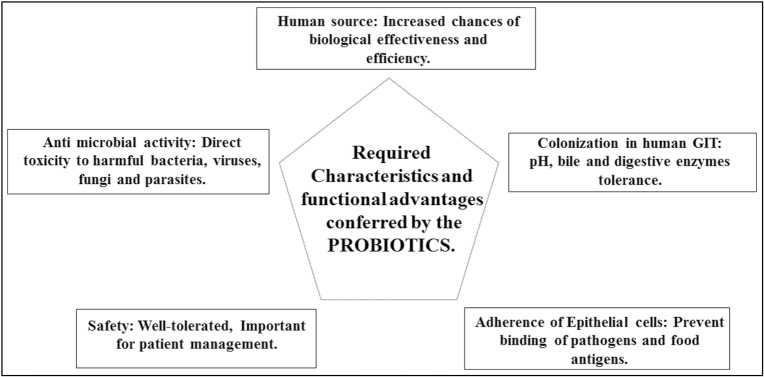

Common probiotic preparations existing in India and their prices are mentioned in Table 2.[41] The required characteristics and advantages provided by the existing probiotic preparations in Indian market are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Common probiotic products available in the Indian market

| S. no. | Brand names | Microorganism composition | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VSL3 capsules | Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, B. longum, B. infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii bulgaricus, and L. paracasei | A strip of 10 capsule = Rs 251.65 |

| 2 | Pre-Pro capsule | S. faecalis, Clostridium butyricum, Bacillus mesentericus, and L. acidophilus | A strip of 10 capsules = Rs 80 |

| 3 | Vizyl capsule | B. mesentericus, C. butyricum, S. faecalis, and L. sporogenes | A strip of 10 capsules = Rs 77.05 |

| 4 | BIFILAC capsules | S. faecalis, Lactobacillus, C. butyricum, and B. mesentericus | A strip of 10 capsules = Rs 86.48 |

| 5 | BECELAC PB capsule | L. acidophilus, calcium, pantothenic acid, nicotinic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin C, folic acid, vitamin B6, vitamin B2, and thiamine nitrate | A strip of 10 capsules = Rs 72 |

| 6 | VIBACT capsule | S. faecalis, C. butyricum, and B. mesentericus | A strip of 10 capsules = Rs 790.2 |

| 7 | BIFILAC sachets | S. faecalis, C. butyricum, and B. mesentericus | One sachet = Rs 9.75 |

| 8 | Econorm sachets | S. boulardii | One sachet = Rs 34.8 |

| 9 | Vizyl sachets | B. mesentericus, C. butyricum, S. faecalis, and L. sporogenes | One sachet = Rs 8 |

Figure 1.

Required characteristics and functional advantages conferred by probiotics

Issues with Probiotic Use

Regulatory requirements differ vastly depending on the proposed therapeutic benefit (drug or as a complementary to diet). If it is planned to be consumed as a dietary supplement, then a demonstration of safety and efficacy before the steps of marketing permission and Food and Drug Administration approval are not necessary. The premarket notice suffices for the purpose. Saccharomyces boulardii is available in the market as a food supplement for healthy individuals. Conversely, probiotics are commonly observed to be prescribed in resistant and progressive diseases due to a rise in the incidents of C. difficile infection and severity lately. Although uncommon, patient population using probiotics showed a grave side effect––fungemia. Pharmacovigilance of probiotics is required to strengthen the safety of probiotic supplements because these are prescribed for patient population in general practice as well.[42]

Conclusion and Future Trend

We live in an ecosystem with the balance of harmful and beneficial microorganisms in the gut, and rising evidence suggests the fact that without the action of gut microorganisms, our behavior, stress handling capacity, and cognition could not have been developed to the present degree. We rely heavily on the neurotransmitters created by commensal gut flora. The variety of this gut microbiome is developed in the first few months after birth and is highly susceptible to genetic, dietary, and environmental factors throughout lifetime. The transfer of behavioral symptoms by fecal microorganism’s relocation or implantation between animals is also fascinating. The manipulation of microorganisms via probiotic use can have a role in controlling behavior after the management of psychiatric disorders.[43] Fecal microorganism transfer is used heavily in the management of conditions, such as chronic persistent C. difficile disease.[44] This has to be taken with a pinch of salt because the regulatory and pharmacovigilance of probiotics are still in the nascent stage, which also raise the essential question on existing treatment approaches, such as donor selection for fecal microorganism transfer. The decoding of two-way information exchange between the CNS and the GI microbiome is important in understanding and exploration of treatment options for psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia. Animal studies on GF mice have played a crucial role in putting missing links in place.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:69–75. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:511–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehninger D, Sano Y, de Vries PJ, Dies K, Franz D, Geschwind DH, et al. Gestational immune activation and tsc2 haploinsufficiency cooperate to disrupt fetal survival and may perturb social behavior in adult mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:62–70. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyte M. Microbial endocrinology in the microbiome-gut-brain axis: how bacterial production and utilization of neurochemicals influence behavior. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003726. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyte M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011;33:574–81. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med. 2016;8:39. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers GB, Keating DJ, Young RL, Wong ML, Licinio J, Wesselingh S. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:738–48. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuruya A, Kuwahara A, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Tsubo T, Suga S, et al. Ecophysiological consequences of alcoholism on human gut microbiota: implications for ethanol-related pathogenesis of colon cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27923. doi: 10.1038/srep27923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeGruttola AK, Low D, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E. Current understanding of dysbiosis in disease in human and animal models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1137–50. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argou-Cardozo I, Zeidán-Chuliá F. Clostridium bacteria and autism spectrum conditions: a systematic review and hypothetical contribution of environmental glyphosate levels. Med Sci. 2018;6:29. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzek E, Beckmann H. Different genetic background of schizophrenia spectrum psychoses: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:76–83. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritsner MS, Gottesman II. InHandbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. The schizophrenia construct after 100 years of challenges; pp. 1–44. Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyle JT. NMDA receptor and schizophrenia: a brief history. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:920–6. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–81. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cryan JF, O’Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:187–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledochowski M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Fuchs D. Lactose malabsorption is associated with early signs of mental depression in females: a preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2513–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1026654820461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadooka Y, Sato M, Imaizumi K, Ogawa A, Ikuyama K, Akai Y, et al. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:636–43. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinan TG, Borre YE, Cryan JF. Genomics of schizophrenia: time to consider the gut microbiome? Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1252–7. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song X, Fan X, Song X, Zhang J, Zhang W, Li X, et al. Elevated levels of adiponectin and other cytokines in drug naïve, first episode schizophrenia patients with normal weight. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:269–73. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedrini M, Massuda R, Fries GR, de Bittencourt Pasquali MA, Schnorr CE, Moreira JC, et al. Similarities in serum oxidative stress markers and inflammatory cytokines in patients with overt schizophrenia at early and late stages of chronicity. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:819–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hope S, Ueland T, Steen NE, Dieset I, Lorentzen S, Berg AO, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 are associated with general severity and psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2013;145:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Severance EG, Alaedini A, Yang S, Halling M, Gressitt KL, Stallings CR, et al. Gastrointestinal inflammation and associated immune activation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;138:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RS. A comprehensive macrophage-T-lymphocyte theory of schizophrenia. Med Hypotheses. 1992;39:248–57. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(92)90117-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt K, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ, Tzortzis G, Errington S, Burnet PW. Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:1793–801. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3810-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mental Health Foundation. 2007. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/d/diet-and-mental-health .

- 27.Fond G, Capdevielle D, Macgregor A, Attal J, Larue A, Brittner M, et al. [Toxoplasma gondii: a potential role in the genesis of psychiatric disorders] Encephale. 2013;39:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyaoka T, Wake R, Furuya M, Liaury K, Ieda M, Kawakami K, et al. Minocycline as adjunctive therapy for patients with unipolar psychotic depression: an open-label study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;37:222–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandler RH, Finegold SM, Bolte ER, Buchanan CP, Maxwell AP, Väisänen ML, et al. Short-term benefit from oral vancomycin treatment of regressive-onset autism. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:429–35. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Björkholm B, Samuelsson A, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3047–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asano Y, Hiramoto T, Nishino R, Aiba Y, Kimura T, Yoshihara K, et al. Critical role of gut microbiota in the production of biologically active, free catecholamines in the gut lumen of mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1288–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00341.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, Sharon G, Hyde ER, McCue T, et al. Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. 2013;155:1451–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Theije CG, Wopereis H, Ramadan M, van Eijndthoven T, Lambert J, Knol J, et al. Altered gut microbiota and activity in a murine model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;37:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Bienenstock J, Dinan TG. The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:164–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savignac HM, Couch Y, Stratford M, Bannerman DM, Tzortzis G, Anthony DC, et al. Prebiotic administration normalizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced anxiety and cortical 5-HT2A receptor and IL1-β levels in male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;52:120–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pusceddu MM, El Aidy S, Crispie F, O’Sullivan O, Cotter P, Stanton C, et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) reverse the impact of early-life stress on the gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, Katsafanas E, Savage CL, Schweinfurth LA, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation on schizophrenia symptoms and association with gastrointestinal functioning: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16:PCC.13m01579. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomasik J, Yolken RH, Bahn S, Dickerson FB. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotic supplementation in schizophrenia patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biomark Insights. 2015;10:47–54. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Severance EG, Gressitt KL, Stallings CR, Katsafanas E, Schweinfurth LA, Savage CLG, et al. Probiotic normalization of Candida albicans in schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, longitudinal pilot study. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yolken RH, Severance EG, Sabunciyan S, Gressitt KL, Chen O, Stallings C, et al. Metagenomic sequencing indicates that the oropharyngeal phageome of individuals with schizophrenia differs from that of controls. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:1153–61. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Probiotics in India. 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.mims.com/india/drug/search?q=probiotic .

- 42.Venugopalan V, Shriner KA, Wong-Beringer A. Regulatory oversight and safety of probiotic use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1661–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins SM, Kassam Z, Bercik P. The adoptive transfer of behavioral phenotype via the intestinal microbiota: experimental evidence and clinical implications. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers GB, Bruce KD. Challenges and opportunities for faecal microbiota transplantation therapy. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:2235–42. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]