Abstract

Background:

Household air pollution (HAP) from solid fuel use for cooking affects 2.5 billion individuals globally and may contribute substantially to disease burden. However, few prospective studies have assessed the impact of HAP on mortality and cardiorespiratory disease.

Objectives:

Our goal was to evaluate associations between HAP and mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and respiratory disease in the prospective urban and rural epidemiology (PURE) study.

Methods:

We studied 91,350 adults 35–70 y of age from 467 urban and rural communities in 11 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, India, Pakistan, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe). After a median follow-up period of 9.1 y, we recorded 6,595 deaths, 5,472 incident cases of CVD (CVD death or nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or heart failure), and 2,436 incident cases of respiratory disease (respiratory death or nonfatal chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary tuberculosis, pneumonia, or lung cancer). We used Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for individual, household, and community-level characteristics to compare events for individuals living in households that used solid fuels for cooking to those using electricity or gas.

Results:

We found that 41.8% of participants lived in households using solid fuels as their primary cooking fuel. Compared with electricity or gas, solid fuel use was associated with fully adjusted hazard ratios of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.21) for all-cause mortality, 1.08 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.17) for fatal or nonfatal CVD, 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.30) for fatal or nonfatal respiratory disease, and 1.12 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.19) for mortality from any cause or the first incidence of a nonfatal cardiorespiratory outcome. Associations persisted in extensive sensitivity analyses, but small differences were observed across study regions and across individual and household characteristics.

Discussion:

Use of solid fuels for cooking is a risk factor for mortality and cardiorespiratory disease. Continued efforts to replace solid fuels with cleaner alternatives are needed to reduce premature mortality and morbidity in developing countries. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP3915

Introduction

Approximately 2.5 billion individuals globally are exposed to household air pollution (HAP) from cooking with solid fuels such as coal, wood, dung, or crop residues (Smith et al. 2014). Concentrations of air pollutants, especially fine particulate matter [)], can be several orders of magnitude higher in homes cooking with solid fuels compared with those using clean fuels such as electricity or liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) (Clark et al. 2013; Shupler et al. 2018). in outdoor air has been linked to mortality, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, and respiratory diseases (Kim et al. 2015).

Despite the large population exposed and the potential for adverse health effects, few prospective cohort studies have examined the health effects of HAP. Only four studies have examined HAP and mortality and reached contradictory conclusions (Alam et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2016; Mitter et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2018). Further, studies have not examined HAP and fatal as well as nonfatal cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. There is growing evidence of the adverse effects of HAP on respiratory diseases and lung cancer; however, most studies are cross sectional or case–control in design, with relatively small sample sizes and limited geographic coverage (Gordon et al. 2014). To date, few prospective studies have examined HAP exposures and respiratory events in adults, and the existing studies have reported contradictory findings (Chan et al. 2019; Ezzati and Kammen 2001; Mitter et al. 2016).

Given the absence of direct epidemiological data, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated the potential impact of HAP on health using exposure–response relationships that pooled data from studies on outdoor air pollution, secondhand smoke, and active smoking (Burnett et al. 2014). These predictions indicated that 1.6 million deaths were attributable to HAP exposure in 2017, of which 39% were from IHD and stroke and 55% from respiratory outcomes [ from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI)] (GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators 2018). Given the lack of direct epidemiological evidence and this large predicted burden, there is an urgent need to directly characterize the health effects associated with HAP.

Within the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, we conducted an analysis of 91,350 adults from 467 urban and rural communities in 11 low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) where solid fuels are commonly used for cooking. We examined associations between cooking with solid fuels—as a proxy indicator of HAP exposure—and cause-specific mortality, incident cases of CVD [CVD death and incidence of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure (HF)] and incident cases of respiratory disease [respiratory death, nonfatal COPD, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia, or lung cancer]. We estimated associations between solid fuel use for cooking and these outcomes, controlling for extensive individual, household, and community covariates.

Methods

The PURE Cohort and Household Air Pollution Substudy

The PURE study is a large multinational cohort study of individuals 35–70 y of age enrolled from 21 countries in five continents. The methodology of the PURE study has been described in detail elsewhere (Dehghan et al. 2017; Teo et al. 2009; Yusuf et al. 2014). Briefly, PURE countries were selected to cover a wide range of socioeconomic and environmental settings, especially in LMICs, where health-related data are sparse. The primary sampling unit was the “community” in urban areas, selected based on known information of the geographical area such as a set of contiguous postal codes or groups of streets corresponding roughly to a neighborhood. Rural communities were small villages at least from cities. Many of these communities were remote with few health facilities. Communities were clustered into centers (representing regions) within countries. Households with at least one member 35–70 y of age with no plans to move in the next 5 y were approached for recruitment. This HAP analysis was restricted to the subset of individuals living in centers where at least 10% of the participants primarily used solid fuels for cooking. This resulted in a study population of 91,350 adults from 467 urban and rural communities in 11 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, India, Pakistan, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe).

Data Collection

Baseline data included in this analysis were collected from 2002 to 2015. Standardized interview-based questionnaires were used to collect individual and household information on demographics, socioeconomic status (SES), risk factors, and medical histories (Corsi et al. 2013; Teo et al. 2009; Yusuf et al. 2014).

Face-to-face or telephone interviews were conducted with participants at least every 3 y during follow-up to document events. Up to three attempts were made to interview all households. The PURE study includes LMICs where there is unreliable or no death or clinical event registries. To determine a probable cause of death, hospitalization, or event, we obtained information from interviews of participants or their relatives, additional details from hospital records, medically certified cause of death, and verbal autopsies where medical information was not available (Gajalakshmi et al. 2002). Additional information on CVD (MI, stroke, and HF) were collected and used for event adjudication, conducted centrally in each county by trained physicians using standardized definitions. To ensure a consistent approach and high accuracy for event classification across all countries and over time, the first 100 CVD events per year for China and India, and 50 events per year for other countries, were adjudicated both locally and centrally by an adjudication chair (Dehghan et al. 2017; Teo et al. 2009; Yusuf et al. 2014).

We examined a range of outcomes hypothesized to be related to HAP. Mortality outcomes included all-cause mortality, cause-specific mortality due to any CVD, any respiratory condition, any cancer, all other causes combined (excluding CVD, respiratory, and cancer mortality), and accidental mortality (deaths due to accident or trauma in the absence of other causes) as well as deaths due to unspecified causes (not classified). We estimated associations with fatal and nonfatal CVD (MI, stroke, HF), and hospitalization (defined as any medical procedure occurring in a hospital environment or a length of stay for at least 12 h in a hospital, clinic, or emergency room or other similar location) for CVD (MI, stroke, HF), as well as fatal and nonfatal major respiratory diseases (COPD, TB, pneumonia, lung cancer), and hospitalization for major respiratory diseases (COPD, TB, pneumonia, lung cancer). In addition, we examined a composite outcome that included deaths from any cause and the first incidence of any major nonfatal CVD (MI, stroke, HF) or major respiratory outcome (COPD, TB, pneumonia, lung cancer), hereafter referred to as “incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality.” We estimated associations with asthma diagnoses as a separate outcome because there is little evidence of an association between HAP and asthma in adults (Po et al. 2011) and asthma may be underdiagnosed in LMICs. We also estimated associations with fatal and nonfatal injuries and injury hospitalizations, which we assumed would not be associated with household use of solid fuels for cooking. Detailed criteria for each outcome are provided in the section, “PURE Event Definitions,” in the Supplemental Material.

HAP exposure was derived from the baseline household questionnaire, which asked, “What is the primary fuel used for cooking?” We compared primary use of solid fuels for cooking (charcoal, coal, wood, agriculture/crop, animal dung, shrub/grass) with primary use of clean fuels (electricity/gas). We excluded kerosene from our analysis () because this fuel was used by only a small number of communities and its use results in different air pollution emissions compared with solid fuels (Smith et al. 2014). We have a separate paper examining cooking with kerosene currently under review. We also explored the influence of a chimney inside the cooking area, other ventilation in the cooking area (windows, exhaust, or partially open to the outside), and solid fuel use for heating.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed the associations between solid fuels for cooking at baseline, compared with clean fuels, for each outcome separately using Cox proportional hazards models with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.). For each outcome examined, participants were censored at the time of the event (death or incident CVD and respiratory disease), at the time of loss to follow-up (if a participant could not be contacted or requested to be removed from the study), or the date of last follow-up (given that PURE event surveillance is ongoing, the date of last follow-up can vary between centers). Interaction terms between solid fuel use and time (p-interaction = 0.88, 0.72, 0.87, and 0.56 for all-cause mortality, CVD, respiratory disease, and the composite outcome, respectively) did not improve model fit; therefore, we concluded that the proportion hazards assumption was met.

The base model (Model 1) included age (continuous), sex, baseline year, and strata variables for center and urban/rural status. Strata variables can be viewed as a robust form of control where individuals are only compared with other individuals in the same strata. Center refers to a unique geographical region of PURE participants, for which 28 regions are included in this analysis (Figure 1). All centers had urban and rural communities, which were also included as strata.

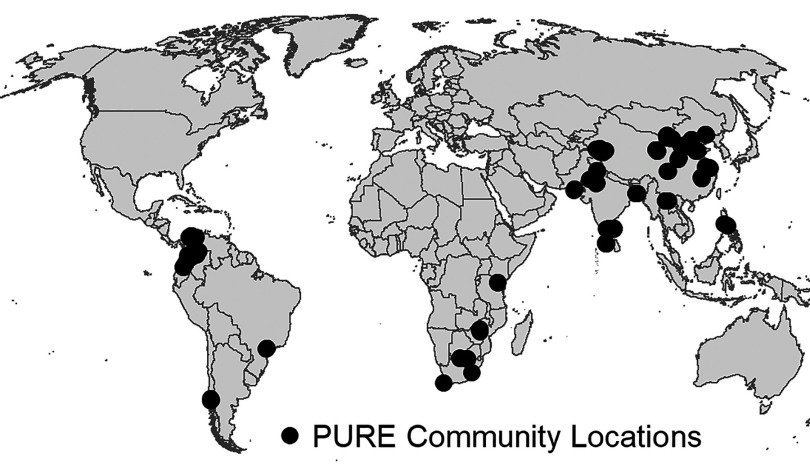

Figure 1.

Map of PURE communities included in the analysis of HAP. Communities were included if they were located in centers with of PURE participants reporting primary use of solid fuels for cooking at baseline.

Model 2 adjusted for additional individual risk factors, including smoking (current, former, never); alcohol use (current, former, never); physical activity (low, moderate, high) assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Craig et al. 2003); body mass index (BMI) (); an alternative healthy eating index (quintiles) developed from dietary intake information collected with a validated food frequency questionnaire (Iqbal et al. 2009); baseline chronic conditions (yes/no; including baseline CVD, diabetes, respiratory disease, and HIV/AIDS); current CVD medication use (yes/no); hypertension (yes/no); the INTERHEART risk score (continuous), a composite index of individual risk measures (Yusuf et al. 2004); and the outdoor average concentrations (continuous) at baseline [based on geographically weighted regression of satellite-based estimates and ground-based measurements at a resolution (van Donkelaar et al. 2016)]. Missing data indicator terms were modeled for all categorical variables with missing data. Details regarding the derivation of the physical activity, INTERHEART risk score, and alternative healthy eating index variables are provided in the section, “Calculation Details for Covariate Measures,” in the Supplemental Material.

Model 3 included all Model 2 covariates plus education (, secondary, trade or college/university); percent of household income spent on food (quintiles); and a strata variable for household wealth index (categorized into country-specific tertiles), which was created from a combination of household assets (Gupta et al. 2017), as described in Supplemental Material.

Exploratory stratified analyses were conducted to examine associations by key characteristics identified as potential modifiers of HAP exposure or health effects. These were identified a priori from the literature and included the following: region (China, South Asia, other countries), urban versus rural communities, sex (male/female), age (, y), education (), household wealth index (tertiles), occupation (professional or skilled/unskilled/homemaker), smoking status (ever/never smoker), CVD medication use (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), chronic condition (yes/no) at baseline, BMI (), INTERHEART risk score (, 5–11, ), presence of a chimney in the kitchen (yes/no), any kitchen ventilation (yes/no), solid fuel use for heating (yes/no), and outdoor concentration ( annual average).

We evaluated the robustness of our findings using several sensitivity analyses. First, to examine consistency in associations across different regions and solid fuel types, we explored models for biomass and coal use separately for China, South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) and other countries (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe) combined into a single group due to smaller sample size. Second, we conducted all analyses for urban and rural communities separately because most households with solid fuel use were in rural communities and there could be important unmeasured context-specific differences between urban and rural areas. Third, we evaluated the sensitivity of our fully adjusted model results to removing or adding specific variables. These included removing covariates that may lie on the causal pathway between HAP and CVD/respiratory events and mortality (baseline chronic conditions, hypertension, CVD medication); removing the household wealth index (which is highly related to solid fuel use); removing outdoor concentrations because emissions from cooking with solid fuels contributes about one-third of ambient air pollution levels in South and South East Asia (Chafe et al. 2014); adding secondhand smoke exposure, occupational class, additional diet variables and lipids (these were not included in the main model due to large amounts of missing data); and adding a community random effect variable ( communities) in order to evaluate clustering of individuals and unmeasured community characteristics. Finally, to examine potential residual confounding and heterogeneity in the effect of HAP by regions and countries, we estimated the effect by center and pooled the estimates using a random effects meta-regression model.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the location of study communities included in this analysis, and Table 1 presents descriptive statistics. Participants from China and India contributed to 47.4% and 26.4% of the total study population, respectively. In urban areas, 8.2% of participants used solid fuel for cooking compared with 71.7% in rural communities. Solid fuel users had lower INTERHEART risk scores (, ) compared with individuals using clean fuels (, ), indicating a higher overall risk for CVD in individuals using clean fuels for cooking. Conversely, indicators of SES (education, percentage of household income spent on food, and household wealth index) were lower for solid fuel users. This complex relationship between solid fuel use and traditional CVD risk factors (e.g., diet, smoking, physical activity) and SES is illustrated in Figure S1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 91,350 individuals living in centers with solid fuel use for cooking, stratified by urban/rural status and solid fuel use for cooking versus electricity or gas.

| Characteristic | All participants | Urban () | Rural () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid fuel | Clean fuel | Solid fuel | Clean fuel | ||

| Individuals (n) | 91,350 | 3,513 | 39,488 | 34,674 | 13,675 |

| Households (n) | 62,056 | 2,618 | 27,009 | 23,377 | 9,052 |

| Communities (n) | 467 | 137 | 210 | 254 | 199 |

| Age () | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 53,758 (58.9) | 2,266 (64.5) | 23,493 (59.5) | 20,038 (57.8) | 7,961 (58.2) |

| Male | 37,592 (41.2) | 1,247 (35.3) | 15,995 (40.5) | 14,636 (42.2) | 5,714 (41.8) |

| INTERHEART risk score () | |||||

| Education | |||||

| 40,865 (44.70) | 1,809 (51.5) | 9,782 (24.8) | 22,313 (64.4) | 6,961 (50.9) | |

| Secondary school | 37,785 (41.4) | 1,390 (39.6) | 19,120 (48.4) | 11,364 (32.8) | 5,911 (43.2) |

| Trade, college/university | 12,378 (13.6) | 307 (8.7) | 10,475 (26.5) | 834 (2.4) | 762 (5.6) |

| Missing | 322 (0.4) | 7 (0.2) | 111 (0.3) | 163 (2.4) | 41 (0.3) |

| Income spent on food (%) | |||||

| 19,960 (21.9) | 540 (15.4) | 9,499 (24.1) | 6,241 (18) | 3,680 (26.9) | |

| 30–50 | 22,854 (25.0) | 845 (24.1) | 11,997 (30.4) | 6,944 (20.0) | 3,068 (22.4) |

| 50–66 | 20,475 (22.4) | 823 (23.4) | 9,573 (24.2) | 7,445 (21.5) | 2,634 (19.3) |

| 24,334 (26.6) | 1,222 (34.8) | 7,067 (17.9) | 12,784 (36.9) | 3,261 (19.3) | |

| Missing | 3,727 (4.1) | 83 (2.4) | 1,352 (3.4) | 1,260 (3.6) | 1,032 (7.6) |

| Household wealth index (tertile) | |||||

| T1 (lowest) | 31,211 (34.2) | 767 (21.8) | 3,327 (8.4) | 22,177 (64.0) | 4,940 (36.1) |

| T2 | 29,518 (32.3) | 1,663 (47.3) | 12,672 (32.1) | 9,793 (28.2) | 5,390 (39.4) |

| T3 (highest) | 30,550 (33.4) | 1,081 (30.8) | 23,452 (59.4) | 2,673 (7.7) | 3,344 (24.5) |

| Missing | 71 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 37 (0.1) | 31 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Former | 6,077 (6.7) | 245 (7.0) | 2,958 (7.5) | 1,836 (5.3) | 1,038 (7.6) |

| Current | 20,248 (22.2) | 640 (18.2) | 7,227 (18.3) | 9,325 (26.9) | 3,056 (22.4) |

| Never | 63,822 (69.9) | 2,599 (74.0) | 28,902 (73.2) | 22,927 (66.1) | 9,394 (68.7) |

| Missing | 1,203 (1.3) | 29 (0.8) | 401 (1.0) | 586 (1.7) | 187 (1.4) |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Former | 4,088 (4.5) | 152 (4.3) | 1,819 (4.6) | 1,371 (4.0) | 746 (5.5) |

| Current | 17,899 (19.6) | 691 (19.7) | 7,349 (18.6) | 6,578 (19.0) | 3,281 (24.0) |

| Never | 68,531 (75.0) | 2,660 (75.7) | 30,065 (76.1) | 26,301 (75.9) | 9,505 (69.5) |

| Missing | 832 (0.9) | 10 (0.3) | 255 (0.7) | 424 (1.2) | 143 (1.1) |

| BMI () | |||||

| 13,326 (14.6) | 524 (14.9) | 2,830 (7.2) | 8,569 (24.7) | 1,403 (10.3) | |

| 20–30 | 63,920 (70.0) | 2,227 (63.4) | 29,690 (75.2) | 22,073 (63.7) | 9,930 (72.6) |

| 9,592 (10.5) | 582 (16.6) | 5,361 (13.6) | 1,980 (5.7) | 1,669 (12.2) | |

| Missing | 4,512 (4.9) | 180 (5.1) | 1,607 (4.1) | 2,052 (5.9) | 673 (4.9) |

| Physical activity | |||||

| Low | 14,896 (16.3) | 568 (16.2) | 7,234 (18.3) | 4,978 (14.4) | 2,116 (15.5) |

| Moderate | 32,316 (35.4) | 1,111 (31.6) | 15,949 (40.4) | 10,894 (31.4) | 4,362 (31.9) |

| High | 38,178 (41.8) | 1,636 (46.6) | 14,847 (37.6) | 15,955 (46.0) | 5,740 (42.0) |

| Missing | 5,960 (6.5) | 198 (5.6) | 1,458 (3.7) | 2,847 (8.2) | 1,457 (10.7) |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index (quartile) | |||||

| Q1 | 21,752 (23.8) | 1,040 (29.6) | 7,668 (19.4) | 9,516 (27.4) | 3,528 (25.8) |

| Q2 | 21,241 (23.3) | 905 (25.8) | 8,794 (22.3) | 8,304 (24.0) | 3,238 (23.7) |

| Q3 | 21,848 (23.9) | 768 (21.9) | 9,904 (25.1) | 8,083 (23.3) | 3,093 (22.6) |

| Q4 | 22,288 (24.4) | 299 (17.1) | 11,115 (28.2) | 7,361 (21.2) | 3,213 (23.5) |

| Missing | 4,221 (4.6) | 201 (5.7) | 2,007 (5.1) | 1,410 (4.1) | 603 (4.4) |

| Chronic conditiona | |||||

| Yes | 14,597 (16.0) | 633 (18.0) | 7,617 (19.3) | 4,359 (12.6) | 1,988 (14.5) |

| No | 76,753 (84.0) | 2,880 (82.0) | 31,871 (80.7) | 30,315 (87.4) | 11,687 (85.5) |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 34,414 (37.7) | 1,338 (38.1) | 16,191 (41.0) | 11,345 (32.7) | 5,540 (40.5) |

| No | 52,464 (57.4) | 1,989 (56.6) | 21,722 (55.0) | 21,218 (61.2) | 7,535 (55.1) |

| Missing | 4,472 (4.9) | 186 (5.3) | 1,575 (4.0) | 2,111 (6.1) | 600 (4.4) |

| CVD medication use | |||||

| Yes | 11,526 (12.6) | 392 (11.2) | 6,594 (16.7) | 2,592 (7.5) | 1,948 (14.2) |

| No | 79,824 (87.4) | 3,121 (88.8) | 32,894 (83.3) | 32,082 (92.5) | 11,727 (85.8) |

| Outdoor (; ) | |||||

| Region/country (%) | |||||

| China | 43,278 (47.4%) | 762 (21.7%) | 19,331 (49.0%) | 16,884 (48.7%) | 6,301 (46.1%) |

| South Asiab | 28,406 (31.1%) | 1,599 (45.5%) | 11,396 (28.9%) | 12,473 (36.0%) | 2,938 (21.5%) |

| Otherc | 19,666 (21.5%) | 1,152 (32.8%) | 8,761 (22.2%) | 5,317 (15.3%) | 4,436 (32.4%) |

Chronic conditions include baseline CVD, diabetes, respiratory disease, and HIV/AIDS.

Pakistan, India, Bangladesh.

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe.

After a median follow-up period of 9.1 y, we recorded 6,595 deaths, 5,472 incident cases of CVD, and 2,436 incident cases of major respiratory disease. Table 2 summarizes the associations between solid fuels use, relative to clean fuels, for each outcome. Model 1 showed large associations for mortality and respiratory disease and relatively weaker associations with CVD. Model 2 included risk factor adjustments, which resulted in the overall association with mortality and respiratory disease being largely unchanged from Model 1 but also increased the estimates of effect for CVD mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 1.18; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04, 1.34] and incident cases of fatal and nonfatal CVD (1.14; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.23). Model 3 included further adjustment for SES measures, which resulted in attenuation of all associations. Here, solid fuel use was associated with an HR of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.21) for all-cause mortality, 1.08 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.17) for CVD, and 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.30) for respiratory disease. The fully adjusted HRs were slightly larger for CVD (95% CI: 1.10, 1.00, 1.22) and respiratory (95% CI: 1.17, 0.98, 1.38) disease that had documented hospitalization. The HR for the composite outcome of incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality was 1.12 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.91) in the fully adjusted model. No associations were observed in fully adjusted models between injury events or hospitalizations, although a positive association was observed for injury deaths.

Table 2.

Associations (hazard ratios [95% confidence intervals]) between individuals living in households using solid fuels for cooking, compared with clean fuels, and cause-specific mortality, CVD, and respiratory disease during a median of 9.1-y follow-up.

| Health outcome | Events | Model 1 (base model) | Model 2 () | Model 3 () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | 6,595 | 1.24 (1.15, 1.33) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.34) | 1.12 (1.04, 1.21) |

| Cause-specific mortalitya | ||||

| CVD | 2,104 | 1.08 (0.95, 1.22) | 1.18 (1.04, 1.34) | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) |

| Respiratory | 356 | 1.82 (1.32, 2.51) | 1.54 (1.11, 2.12) | 1.34 (0.95, 1.89) |

| Cancer | 1,126 | 1.26 (1.06, 1.49) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.45) | 1.15 (0.96, 1.38) |

| Other causes | 1,034 | 1.50 (1.22, 1.84) | 1.49 (1.21, 1.84) | 1.25 (1.00, 1.55) |

| Injury | 393 | 1.39 (1.03, 1.87) | 1.31 (0.97, 1.77) | 1.24 (0.89, 1.72) |

| Not classified | 1,544 | 1.21 (1.05, 1.40) | 1.17 (1.01, 1.35) | 1.07 (0.91, 1.25) |

| CVD ()b | 5,472 | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 1.14 (1.05, 1.23) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) |

| MI | 2,363 | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | 1.12 (1.00, 1.26) | 1.07 (0.94, 1.22) |

| Stroke | 2,685 | 1.12 (1.00, 1.26) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.30) | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27) |

| Heart failure | 476 | 1.10 (0.84, 1.43) | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.50) |

| CVD hospitalizationc | 4,407 | 1.05 (0.96, 1.15) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25) | 1.10 (1.00, 1.22) |

| Respiratory disease ()d | 2,436 | 1.29 (1.14, 1.46) | 1.24 (1.10, 1.41) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.30) |

| TB | 530 | 1.68 (1.26, 2.23) | 1.48 (1.11, 1.96) | 1.29 (0.95, 1.74) |

| COPD | 708 | 1.31 (1.05, 1.63) | 1.28 (1.02, 1.59) | 1.15 (0.91, 1.44) |

| Pneumonia | 893 | 1.17 (0.95, 1.44) | 1.20 (0.98, 1.48) | 1.17 (0.94, 1.46) |

| Lung cancer | 239 | 0.84 (0.58, 1.24) | 0.83 (0.57, 1.22) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.18) |

| Respiratory hospitalizatione | 1,517 | 1.30 (1.11, 1.52) | 1.29 (1.10, 1.51) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.38) |

| f | 11,111 | 1.18 (1.12, 1.25) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.27) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.19) |

| Asthmag | 693 | 1.15 (0.93, 1.43) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | 0.88 (0.69, 1.11) |

| Injuryh | 3,461 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.16) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.14) |

| Injury hospitalization | 1,213 | 1.16 (0.98, 1.37) | 1.15 (0.97, 1.36) | 1.02 (0.85, 1.22) |

Model 1: Age, sex, baseline year, strata for center and urban/rural status.

Model 2: , smoking, physical activity, alcohol use, alternative healthy eating index, BMI, baseline chronic condition, baseline CVD medication use, baseline hypertensive status, outdoor .

Model 3: , percentage income spent on food, and strata for household wealth index tertile.

Cause-specific death.

Fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure.

Documented hospitalization for myocardial infarction, stroke, or heart failure.

Fatal and nonfatal COPD, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and lung cancer.

Documented hospitalization for COPD, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and lung cancer.

Composite outcome: mortality from any cause or the first incidence of any major nonfatal CVD (MI, stroke, HF) or respiratory outcome (tuberculosis, COPD, pneumonia, or lung cancer, but not asthma) as an indicator of all health outcomes likely related to HAP.

Physician diagnosis of asthma. Not included as a major respiratory disease outcome due to lack of evidence for association with HAP.

Fatal or nonfatal injury. Hospitalizations refer to injuries with a documented hospital admission.

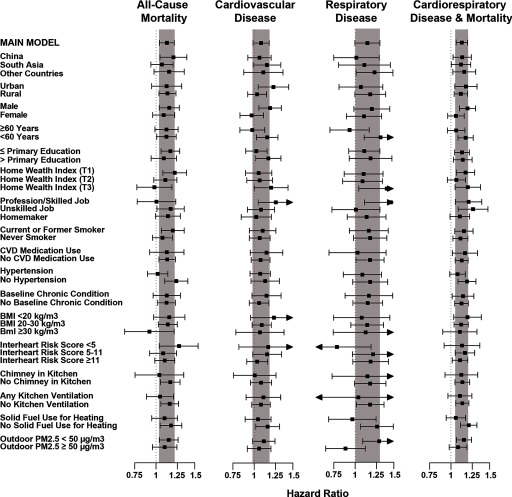

Stratified analyses are illustrated in Figure 2, and model estimates provided in Table S1. There was general consistency in the associations observed across individual, household, and geographic variables. Greater variation was seen for CVD and respiratory events, but this is partially due to smaller sample sizes. For all-cause mortality, we observed larger associations in China (; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.38) compared with South Asia (; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.20) and other countries (; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.34); for men (; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.28) compared with women (; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.22); for ever-smokers (; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.34) compared with never smokers (; 95% CI: 0.96, 1.19); and for individuals with no chimney in their kitchen (; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.29) compared with homes with chimneys (; 95% CI: 0.80, 1.34).

Figure 2.

Fully adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for all-cause mortality, CVD events (fatal and nonfatal MI, stroke, and HF), respiratory disease (fatal and nonfatal COPD, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and lung cancer), and incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality, stratified by individual, household and community characteristics, comparing solid fuel use for cooking to electricity/gas. The shaded regions represent 95% CI of the overall fully adjusted model. Full model estimates are provided in Table S1.

Sensitivity Analyses

Findings for biomass and coal use for cooking are presented in Table S2. Coal use for cooking was almost exclusively used in China ( individuals), whereas only 133 homes in South Asia and 378 homes in other countries reported primary use of coal for cooking. Overall, we observed larger fully adjusted associations with mortality for biomass use (; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.24) than for coal use (; 95% CI: 0.88, 1.24) compared with electricity or gas. When restricted to China, we observed elevated associations for mortality only for biomass use (; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.61) and not for coal use (; 95% CI: 0.81, 1.20), as well as larger associations for the combined incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality outcome for biomass (; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.30) compared with coal use (; 95% CI: 0.94, 1.21).

Effect estimates from models restricted to urban or rural communities are provided in Table S3. In rural communities, solid fuel use for cooking, compared with clean fuel use, was associated with a fully adjusted HR of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.23) for all-cause mortality, 1.03 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.14) for CVD, 1.18 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.38) for respiratory disease, and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.19) for the combined incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality outcome. Stroke (; 95% CI: 0.97, 1.28) and CVD hospitalizations (; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.24) were the only CVD outcomes increased with solid fuel use in rural communities. In urban communities, solid fuel use was associated with a fully adjusted HR of 1.12 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.31) for all-cause mortality, 1.23 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.44) for CVD, 1.07 (95% CI: 0.85, 1.34) for respiratory disease, and 1.17 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.32) for the combined incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality.

Effect estimates from sensitivity analyses are provided in Table S4. Results from our fully adjusted model did not change appreciably when we removed baseline chronic conditions, hypertension, and CVD medication use; removed outdoor ; added secondhand smoke exposure, occupational class, additional diet and lipid variables; and added a community random effect variable. The largest change occurred when we removed the household wealth index from the model (highly correlated with solid fuel use), which increased all associations. Here, solid fuel use compared with clean fuel use was associated with a fully adjusted HR of 1.17 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.26) for all-cause mortality, 1.09 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.18) for CVD, 1.19 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.35) for respiratory disease, and 1.15 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.22) for the combined incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality.

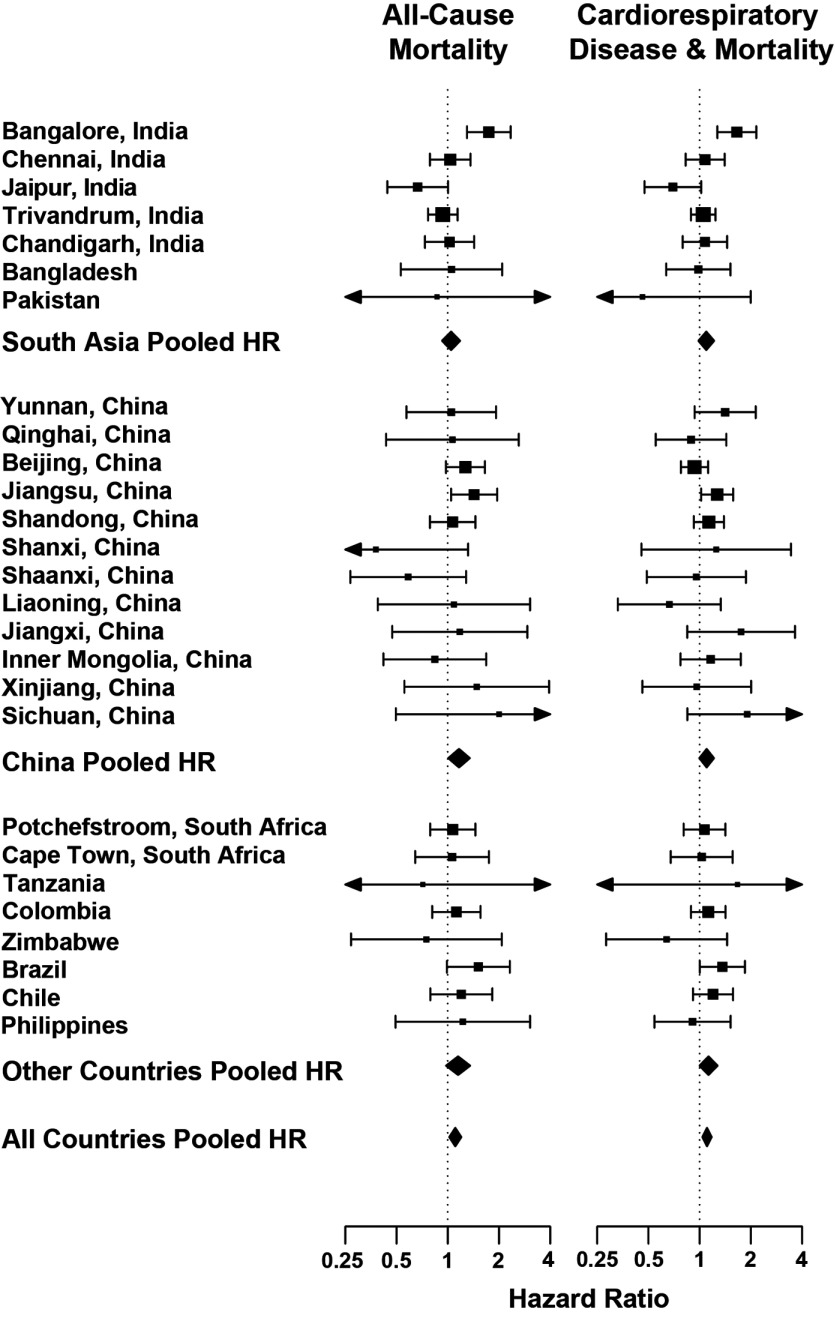

Finally, to examine potential residual confounding and heterogeneity in the effect of HAP by centers, regions, and countries, we estimated fully adjusted models by center and pooled the estimates using random effects meta-regression. Figure 3 illustrates the center-specific results for all-cause mortality and the combined incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality. For all-cause mortality, the overall pooled HR was 1.10 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.23) with an , . For the combined outcomes, the overall pooled HR was 1.11 (1.02, 1.20) with an , . Region-specific HR estimates and statistics are provided in Table S5. Due to sample size limitations, we did not run center-specific models for CVD or respiratory events.

Figure 3.

Center-specific fully adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals comparing solid fuel use for cooking with electricity/gas. The pooled HR for all-cause mortality is 1.10 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.23) with an , and for the incident cardiorespiratory disease and all-cause mortality composite the HR is 1.11 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.20) with an , .

Discussion

Findings from our diverse cohort of 91,350 adults living in 467 urban and rural communities in 11 countries suggest that the residents of households that used solid fuels for cooking had higher all-cause mortality, fatal and nonfatal CVD, and fatal and nonfatal major respiratory conditions compared with residents of households that used clean fuels for cooking.

Our findings contribute to the existing evidence suggesting an association between HAP and all-cause and CVD mortality. Within the China Kadoorie Biobank study (271,217 participants, 15,468 deaths over a 7.5-y follow-up period), solid fuels use for cooking, compared with clean fuel use, was associated with an HR of 1.11 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.20) for all-cause mortality and 1.20 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.41) for CVD mortality (Yu et al. 2018). When we restricted our models to China, we estimated an HR of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.38) for all-cause mortality when comparing solid to clean fuel users but found no association for CVD mortality. Although our study included 12 diverse regions in China, this sample is not representative of the entire Chinese population. In another study of 74,941 women in Shanghai, the estimated HRs for women reporting ever using coal for cooking, compared with never, were 1.12 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.21) for all-cause mortality and 1.18 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.37) for CVD mortality (Kim et al. 2016). In rural Bangladesh, a cohort study of 22,337 individuals (1,154 deaths over 10 y) observed incident rate ratios of 1.10 (95% CI: 0.89, 1.37) for noncommunicable disease mortality and 1.07 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.41) for CVD mortality, again comparing solid fuel use for cooking to gas (Alam et al. 2012). Finally, the Iran Golestan Cohort Study examined 50,045 individuals and estimated HRs per 10-y use of wood for cooking of 1.01 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.05) for all-cause mortality and 1.03 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.08) for CVD mortality (Mitter et al. 2016). These four cohorts demonstrate the variability in results linking HAP to mortality. In comparison, we observed HRs for all-cause and CVD mortality for individuals using solid fuels for cooking, compared with clean fuels, of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.21) and 1.08 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.17), respectively. Our all-cause mortality finding was robust across study regions, urban/rural status, and individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics, whereas CVD mortality was more variable.

To our knowledge, our study is the first prospective cohort to examine household solid fuel use for cooking—a proxy indicator of exposure to HAP—as a risk factor for both fatal and nonfatal CVD. This is highly relevant given that a large portion of CVD events in our study were not fatal (2,104 CVD deaths resulted from 5,472 incident cases of CVD) and health care access plays a key role in CVD survival rates. The inclusion of individual education and a household asset index, which may capture a component of health care access, attenuated model results for CVD death from an HR of 1.18 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.34) in Model 2 (controlling for all CVD risk factors) to 1.04 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.19) in the fully adjusted model. For all CVD events (including fatal and nonfatal CVD), this attenuation was less severe, attenuating associations from an HR of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.23) in Model 2 to 1.08 (95% CI: 0.99, 1.17) in the fully adjusted model. Overall, we also observed a larger association with stroke events (HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.27) compared with MI (HR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.94, 1.22), which corresponds to the larger association observed in the China Kadoorie Biobank study for stroke death compared with IHD (Yu et al. 2018). In addition, CVD events with a documented hospitalization remained elevated (HR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.22) in fully adjusted models, comparing individuals using solid fuels for cooking versus those using clean fuels. Although some studies have examined HAP and surrogate markers (e.g., inflammation processes, atherosclerosis, blood pressure) that correlate with CVD outcomes (Fatmi and Coggon 2016), these are not necessarily a reliable basis for public health interventions. By contrast, our study is based on a large number of CVD deaths and nonfatal events that were accrued during systematic and prospective follow-up, and our results add to the body of evidence suggesting that HAP is a risk factor for CVD.

We also observed associations between HAP and major respiratory disease, which aligns with and strengthens the existing literature. A longitudinal analysis of 280,000 Chinese nonsmokers comparing solid fuels users with clean fuels users estimated an HR of 1.36 (95% CI: 1.32, 1.40) for major respiratory diseases, including chronic lower respiratory disease, COPD, and ALRI (Chan et al. 2019). Here we estimated an overall HR of 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.30) for respiratory disease, including TB, COPD, pneumonia, and lung cancer, for individuals cooking with solid fuels compared with clean fuels. We did not observe an association between HAP and asthma, which is consistent with prior studies (Po et al. 2011). A systematic review of 24 HAP and COPD studies estimated increased odds ratios (ORs) of 2.30 (95% CI: 1.73, 2.06) for women and 1.90 (95% CI: 1.15, 3.13) for men exposed to HAP (Smith et al. 2014). A recent study not included in this meta-analysis of 12,396 adults in 13 LMICs estimated an OR of 1.41 (95% CI: 1.18, 1.68) for COPD in homes using biomass compared with clean fuels (Siddharthan et al. 2018). In our study, we estimated an HR of 1.15 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.44) for COPD for individuals using solid fuels for cooking, compared with clean fuels. A systematic review of 12 studies of HAP and TB estimated that individuals exposed to HAP had a pooled OR of 1.30 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.62) compared with individuals who were not exposed (Sumpter and Chandramohan 2013). We estimated an HR of 1.29 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.74) for TB in those exposed to HAP compared with those using clean fuels. Finally, for pneumonia we observed an HR of 1.17 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.46) for individuals using solid fuels for cooking. Although there is a strong body of evidence for the increased risk of pneumonia in children (Smith et al. 2011, 2014), this has not been documented for adults (Shen et al. 2009). We did not observe any association with lung cancer; however, there were only 239 lung cancer cases documented during follow-up.

We observed mixed findings for individual and household characteristics that could modify HAP exposures or susceptibility to HAP health effects. We observed reductions in associations between solid fuels used for cooking and health events if kitchens had a chimney, especially for all-cause mortality and CVD. The magnitude of these differences align with other large cohort findings of the impact of ventilation (Yu et al. 2018, 2018). Surprisingly, we did not see larger associations for women, who would be expected to have higher air pollution exposure levels if they are responsible for cooking in the household, although we did not have information on whether individuals were responsible for cooking. We also did not observe larger associations if homes reported using solid fuels for cooking, although most households reporting heating were in China and used coal. Similarly, associations with solid fuels for cooking were not stronger in areas with higher outdoor concentrations (dichotomized as ). Although we observed some differences in the effects of HAP by smoking status, these were small and varied by outcome, which aligns with the mixed findings in the literature (Brook et al. 2010).

We relied on reported history of primary cooking fuels at baseline as our indicator for long-term HAP exposure, comparing individuals who lived in households using solid fuel to households using gas or electricity. To our knowledge, the use of fuel types as a surrogate for HAP is the only approach that has been used to date to examine mortality and CVD (e.g., Alam et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2016; Mitter et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2018) due to the difficultly of measuring household for large populations over long time periods. Recent global estimates suggest a difference between electricity/gas and biomass kitchens (Shupler et al. 2018), which supports the use of fuel types as an indicator of HAP in our study. Importantly, these measurement studies also highlight the exposure misclassification present and potential attenuation of our HAP effect estimates when fuel surrogates are used to represent air pollution exposures. Ongoing research in the PURE cohort will address this limitation by measuring concentrations in a subset of study homes (along with personal samples) (Arku et al. 2018). Future analyses will implement regression calibration approaches (Weller et al. 2007) to integrate this monitoring data to adjust our estimates of solid fuel use versus electricity or gas for measurement error. We will also develop a predictive household model to apply to the entire cohort to examine associations between predicted household concentrations and disease events (Arku et al. 2018).

Our study has several strengths, including the prospective design, large sample size, inclusion of multiple countries and communities to increase the generalizability of results, collection of extensive individual and household information to control for confounding, and comprehensive and systematic information on outcomes using standardized definitions. However, there are also specific limitations. First, we have no information on the use of secondary fuels, the time spent cooking with solid fuels, or prior cooking fuel types used in childhood or young adulthood. HAP exposure may also vary by cultural, gender, age, and household characteristics (Balakrishnan et al. 2011). Our assumption of similar exposures for any given solid fuel type, although common in the HAP literature, likely leads to exposure misclassification that would bias our results towards the null. We partially address this issue in the center-specific meta-analysis approach, which demonstrated similar findings to our overall model. Second, there were 1,544 deaths for which we did not have an assigned cause of death (because they occurred at home without any medical care). The overall association between these deaths and solid fuel use was 1.07 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.25). A proportion of these may be CVD deaths, but it is unlikely that this would explain the weaker association observed in our study between solid fuel use and CVD compared with other causes of death. Currently, 32% of the deaths in our study population were from CVD, which concurs with existing estimates in LMICs (Roth et al. 2015). Third, differentiating asthma and COPD is a challenge in low resource settings. However, there were clear differences in the direction of association between HAP with asthma and COPD in our study, which agrees with the underlying pathophysiology of asthma as allergic or related to cellular permeability in contrast to COPD and the development of fibrosis. Fourth, we did not distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke given the lack of available data in many low-income PURE countries. Fifth, we did not have sufficient power to examine the effects of specific fuel types (e.g., dung, wood, agricultural products) or more specific outcomes (e.g., cancer types), but these analyses will be possible once more events accrue during further follow-up. Sixth, we included a missing category for information not reported for several covariates, but overall missingness was limited for variables included in the main analyses. Finally, an important limitation inherent to any study of HAP is separating the HAP effect from other poverty-related effects. For all outcomes, education resulted in the greatest attenuation of the effects of solid fuel use for cooking but did not explain all SES-related attenuation. The household wealth index also resulted in attenuation of the HAP model estimates. In addition, we examined injury events as a possible negative control (although injury events includes burns, which may be associated with solid fuel use) and observed no associations between all documented events () or hospitalizations () but a positive association with deaths (). Overall, we did not observe consistent patterns in our solid fuel health estimates across SES variables (education, home wealth index, occupation, percentage of income spent on food, and medication use) that would suggest our results are due to residual confounding by poverty-related effects.

Conclusions

We showed an increase in the risks of all-cause mortality, CVD, and respiratory disease among individuals living in households using solid fuels for cooking, compared with those using clean fuels. The results from this large, diverse population of 91,350 adults from 467 urban and rural communities in 11 LMICs adds to the strength of evidence supporting HAP as an important risk factor for chronic disease. Given that approximately 2.5 billion individuals live in households still using solid fuels for cooking, replacing these with cleaner energy sources may represent an important approach to reducing premature mortality and morbidity in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The main PURE study and its components are funded by the Population Health Research Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario and through unrestricted grants from several pharmaceutical companies [with major contributions from AstraZeneca (Canada), Sanofi-Aventis (France and Canada), Boehringer Ingelheim (Germany and Canada), Servier, and GlaxoSmithKline] and additional contributions from Novartis and King Pharma. The PURE-AIR study is funded by Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR; grant 136893) and by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH; award DP5OD019850). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CIHR or the NIH. Various national or local organizations in participating countries also contributed: Fundacion ECLA (Argentina); Independent University, Bangladesh and Mitra and Associates (Bangladesh); Unilever Health Institute (Brazil); Public Health Agency of Canada and Champlain Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Network, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and Population Health Research Institute (Canada); Universidad de la Frontera (Chile); National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases (China); Colciencias (grant 6566-04-18062; Colombia); Indian Council of Medical Research (India); Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Malaysia [grant 100–IRDC/BIOTEK 16/6/21 (13/2007) and grant 07-05-IFN-BPH 010], Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia [grant 600-RMI/LRGS/5/3 (2/2011)], Universiti Teknologi MARA, and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM-Hejim-Komuniti-15-2010) (Malaysia); Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant 290/W-PURE/2008/0), and Wroclaw Medical University (Poland); North-West University, South Africa and Netherlands Programme on Alternatives in Development (SANPAD), National Research Foundation, Medical Research Council of South Africa, South African Sugar Association (SASA), and Faculty of Community and Health Sciences (UWC; South Africa); AFA Insurance; Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, Swedish Research Council, the Swedish State under LäkarUtbildningsAvtalet agreement, and the Västra Götaland Region (FOUU; Sweden); Metabolic Syndrome Society, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Aventis (Turkey); and Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum award for Medical Sciences and Dubai Health Authority (United Arab Emirates). S.Y. holds the Heart and Stroke Foundation/Marion W. Burke Chair in Cardiovascular Disease. A complete list of PURE Project office staff, national coordinators, investigators, and key staff is provided in the section, “PURE Project Investigators and Staff,” in the Supplemental Material.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material is available online (https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP3915).

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Note to readers with disabilities: EHP strives to ensure that all journal content is accessible to all readers. However, some figures and Supplemental Material published in EHP articles may not conform to 508 standards due to the complexity of the information being presented. If you need assistance accessing journal content, please contact ehponline@niehs.nih.gov. Our staff will work with you to assess and meet your accessibility needs within 3 working days.

References

- Alam DS, Chowdhury MAH, Siddiquee AT, Ahmed S, Hossain MD, Pervin S, et al. 2012. Adult cardiopulmonary mortality and indoor air pollution: a 10-year retrospective cohort study in a low-income rural setting. Glob Heart 7(3):215–221, PMID: 25691484, 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arku RE, Birch A, Shupler M, Yusuf S, Hystad P, Brauer M. 2018. Characterizing exposure to household air pollution within the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Environ Int 114:307–317, PMID: 29567495, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan K, Ramaswamy P, Sambandam S, Thangavel G, Ghosh S, Johnson P, et al. 2011. Air pollution from household solid fuel combustion in India: an overview of exposure and health related information to inform health research priorities. Glob Health Action 4(1):5638, PMID: 21987631, 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA III, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. 2010. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121(21):2331–2378, PMID: 20458016, 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett RT, Pope CA III, Ezzati M, Olives C, Lim SS, Mehta S, et al. 2014. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Health Perspect 122(4):397–403, PMID: 24518036, 10.1289/ehp.1307049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafe ZA, Brauer M, Klimont Z, Van Dingenen R, Mehta S, Rao S, et al. 2014. Household cooking with solid fuels contributes to ambient PM2.5 air pollution and the burden of disease. Environ Health Perspect 122(12):1314–1320, PMID: 25192243, 10.1289/ehp.1206340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KH, Kurmi OP, Bennett DA, Yang L, Chen Y, Tan Y, et al. 2019. Solid fuel use and risks of respiratory diseases: a cohort study of 280,000 Chinese never-smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199(3):352–361, PMID: 30235936, 10.1164/rccm.201803-0432OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, et al. 2013. Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment. Environ Health Perspect 121(10):1120–1128, PMID: 23872398, 10.1289/ehp.1206429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi DJ, Subramanian SV, Chow CK, McKee M, Chifamba J, Dagenais G, et al. 2013. Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: baseline characteristics of the household sample and comparative analyses with national data in 17 countries. Am Heart J 166(4):636–646.e4, PMID: 24093842, 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. 2003. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35(8):1381–1395, PMID: 12900694, 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, Li W, Mohan V, et al. 2017. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 390(10107):2050–2062, PMID: 28864332, 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Kammen DM. 2001. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and acute respiratory infections in Kenya: an exposure-response study. Lancet 358(9282):619–624, PMID: 11530148, 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatmi Z, Coggon D. 2016. Coronary heart disease and household air pollution from use of solid fuel: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 118(1):91–109, PMID: 27151956, 10.1093/bmb/ldw015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajalakshmi V, Peto R, Kanaka S, Balasubramanian S. 2002. Verbal autopsy of 48 000 adult deaths attributable to medical causes in Chennai (formerly Madras), India. BMC Public Health 2:7, PMID: 12014994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. 2018. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392(10159):1923–1994, PMID: 30496105, 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KH, et al. 2014. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med 2(10):823–860, PMID: 25193349, 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Kaur M, Islam S, Mohan V, Mony P, Kumar R, et al. 2017. Association of household wealth index, educational status, and social capital with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in South Asia. Am J Hypertens 30(4):373–381, PMID: 28096145, 10.1093/ajh/hpw169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal R, Ajayan K, Bharathi AV, Zhang X, Islam S, Soman CR, et al. 2009. Refinement and validation of an FFQ developed to estimate macro- and micronutrient intakes in a south Indian population. Public Health Nutr 12(1):12–18, PMID: 18325134, 10.1017/S1368980008001845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K-H, Kabir E, Kabir S. 2015. A review on the human health impact of airborne particulate matter. Environ Int 74:136–143, PMID: 25454230, 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Seow WJ, Shu X-O, Bassig BA, Rothman N, Chen BE, et al. 2016. Cooking coal use and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort study of women in Shanghai, China. Environ Health Perspect 124(9):1384–1389, PMID: 27091488, 10.1289/EHP236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitter SS, Vedanthan R, Islami F, Pourshams A, Khademi H, Kamangar F, et al. 2016. Household fuel use and cardiovascular disease mortality: Golestan Cohort Study. Circulation 133(24):2360–2369, PMID: 27297340, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Po JYT, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C. 2011. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 66(3):232–239, PMID: 21248322, 10.1136/thx.2010.147884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, Feigin V, Mensah GA, Naghavi M, et al. 2015. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation 132(17):1667–1678, PMID: 26503749, 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M, Chapman RS, Vermeulen R, Tian L, Zheng T, Chen BE, et al. 2009. Coal use, stove improvement, and adult pneumonia mortality in Xuanwei, China: a retrospective cohort study. Environ Health Perspect 117(2):261–266, PMID: 19270797, 10.1289/ehp.11521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupler M, Godwin W, Frostad J, Gustafson P, Arku RE, Brauer M. 2018. Global estimation of exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from household air pollution. Environ Int 120:354–363, PMID: 30119008, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddharthan T, Grigsby MR, Goodman D, Chowdhury M, Rubinstein A, Irazola V, et al. 2018. Association between household air pollution exposure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outcomes in 13 low- and middle-income country settings. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 197(5):611–620, PMID: 29323928, 10.1164/rccm.201709-1861OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Bruce N, Balakrishnan K, Adair-Rohani H, Balmes J, Chafe Z, et al. 2014. Millions dead: how do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the Comparative Risk Assessment of household air pollution. Annu Rev Public Health 35:185–206, PMID: 24641558, 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, Thompson LM, et al. 2011. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 378(9804):1717–1726, PMID: 22078686, 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumpter C, Chandramohan D. 2013. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the associations between indoor air pollution and tuberculosis. Trop Med Int Health 18(1):101–108, PMID: 23130953, 10.1111/tmi.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo K, Chow CK, Vaz M, Rangarajan S, Yusuf S. 2009. The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: examining the impact of societal influences on chronic noncommunicable diseases in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Am Heart J 158(1):1–7.e1, PMID: 19540385, 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Donkelaar A, Martin RV, Brauer M, Hsu NC, Kahn RA, Levy RC, et al. 2016. Global estimates of fine particulate matter using a combined geophysical-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors. Environ Sci Technol 50(7):3762–3772, PMID: 26953851, 10.1021/acs.est.5b05833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EA, Milton DK, Eisen EA, Spiegelman D. 2007. Regression calibration for logistic regression with multiple surrogates for one exposure. J Stat Plan Inference 137(2):449–461, 10.1016/j.jspi.2006.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Qiu G, Chan K-H, Lam K-B, Kurmi OP, Bennett DA, et al. 2018. Association of solid fuel use with risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in rural China. JAMA 319(13):1351–1361, PMID: 29614179, 10.1001/jama.2018.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. 2004. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet 364(9438):937–952, PMID: 15364185, 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Islam S, Li W, Liu L, et al. 2014. Cardiovascular risk and events in 17 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. N Engl J Med 371(9):818–827, PMID: 25162888, 10.1056/NEJMoa1311890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.